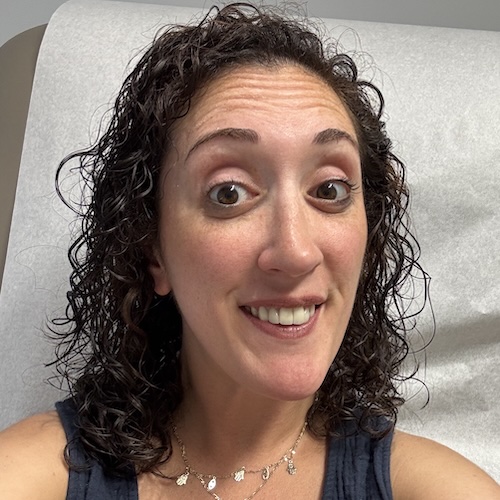

Navigating the “Good Cancer” Guilt: Taylor Scheib’s Story of Self-Advocacy and Finding Her Voice

Thyroid cancer wasn’t on Taylor Scheib’s radar when she first noticed a small lump on her neck at age 26. A sports broadcaster turned storyteller at The Patient Story, Taylor had watched her grandmother’s legacy and her mother’s recent battle with stage 3 colorectal cancer shape her understanding of cancer. But when she sought answers for the growing mass on her neck, she faced years of tests and dismissal. Doctors repeatedly assured her that the nodule was presenting as benign. Importantly, they were also advising her that surgery was optional and cosmetic. Even as it grew. It wasn’t until the lump began to physically impact her sleep and exercise, and she saw how visible it was in photographs, that she pushed for its removal.

Interviewed by: Herself (Taylor Scheib)

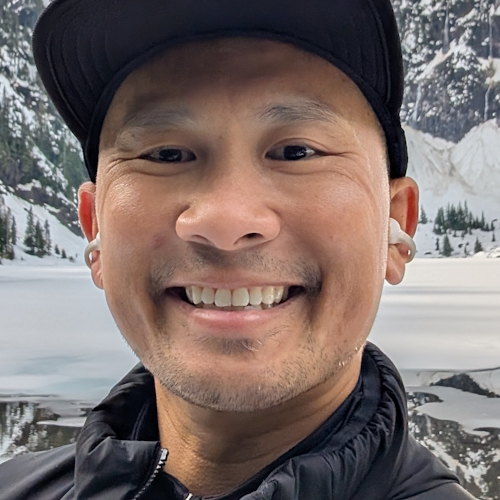

Edited by: Chris Sanchez

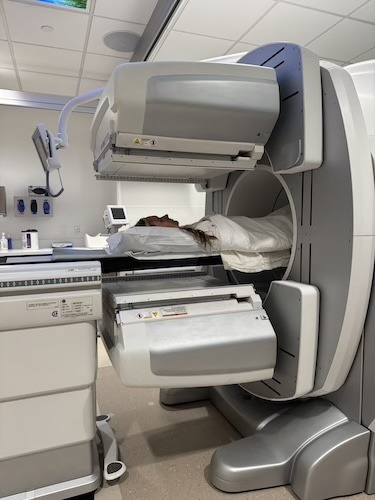

The surgery Taylor underwent in April 2025 was supposed to be the end of a benign chapter. Instead, a MyChart notification delivered a shocking blow: the pathology report revealed oncocytic carcinoma of the thyroid gland, a rare and aggressive subtype of thyroid cancer. Taylor was traumatized by having to receive her diagnosis through a screen before speaking to a doctor, a system failure that ignited her resolve. She immediately sought a second opinion at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle, which led to another thyroidectomy to remove the rest of her thyroid and subsequent radioactive iodine treatment.

Throughout her experience, Taylor has grappled with the complex guilt often associated with having a “treatable” cancer, especially while some of the patients she talks with face more ominous diagnoses. Yet, she realized that every patient’s experience is valid. Today, she uses her platform and The Patient Story’s platform to emphasize the critical importance of self-advocacy and second opinions. Her story is a powerful reminder that even when a condition presents as benign, patients know their bodies best and their stories are always worth telling.

Watch Taylor’s video and read the transcript of her interview below to take a deeper dive into her story.

- Trust your instincts over “benign” labels. Even when medical tests suggest that a condition is harmless, persistent symptoms, like difficulty swallowing or physical changes, warrant further investigation. You are the expert on your own body

- Be prepared for the possibility of getting shocking news electronically when checking test results online. Finding out a diagnosis via an electronic medical record (MyChart) before a doctor’s call is a devastating but increasingly common reality. This is the downside of new laws aimed at giving you access.

- Second opinions are vital. Seeking a second opinion at a comprehensive cancer center can completely change your treatment plan and provide peace of mind, even if it requires travel

- “Good cancer” guilt is real. It is common to feel guilty when facing a “treatable” cancer while others may be suffering more, but minimizing your own trauma doesn’t help anyone. Your pain and fear are valid

- You must be your own biggest advocate. If you cannot fight for yourself, find a friend or family member who will ensure your concerns are heard

- Name: Taylor Scheib

- Diagnosis:

- Thyroid Cancer (Oncocytic)

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 30

- Symptom:

- Appearance of a visible lump on the neck

- Treatments:

- Surgeries: hemithyroidectomy, complete thyroidectomy

- Radiation therapy: radioactive iodine

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- Cancer runs deep in my family

- Discovering the thyroid nodule: Initial symptoms and dismissal

- From storyteller to cancer patient: The guilt of "the good cancer"

- My life before cancer: A career in sports broadcasting

- The lump appeared: Dismissed by doctors for years

- The surgery and the shocking MyChart discovery

- Navigating treatment: Second opinions and radioactive iodine

- The mental toll: Body image, anxiety, and fertility

- Healing and advocacy: Why your story matters

- What I want people to take away from my story and my experiences

Cancer runs deep in my family

I’m no stranger to cancer. It started really early for me, actually. That was when my Grandma Connie was diagnosed with breast cancer. It was actually before I was even born. My dad was a teenager, and unfortunately, she passed away before I was able to meet her. But I know that her legacy and her life live through all of us, especially my dad and his sisters, and through us grandkids. A lot of my family members actually say that I look a lot like her, and I agree.

I always knew what cancer was after my grandma, and as I got older. When I was old enough to really know and talk about my Grandma Connie, that’s when I really started to understand cancer. It was at a young age. Her death impacted a lot of my life in ways that I still don’t realize, and it would be a long time until cancer really directly impacted me again. But it came in November of 2023.

My mom was diagnosed with stage 3 colorectal cancer. I was living in Spokane, Washington. My mom was still back home in Illinois, and I remember she called me. I knew she had gotten a CT scan, but I didn’t know exactly what they were going to find when she called me that day.

She told me they found a mass, and I dropped everything to go and be with her. I think I knew deep down that it was cancer. That’s really because she had symptoms piling up: blood in her stool, fatigue, cramping, and bloating. All the signs really pointed towards colorectal cancer. I went home for a month from my mom’s diagnosis to her getting her treatment plan, to her having a major surgery to remove that tumor. It was really, really hard to see my mom go through that. Those were some of the hardest moments that I’ve had to see my mom go through. She is truly my best friend. To see her in so much pain… The surgery was really horrifying for me, my brother, and my sister. We’d never seen Mom look so tired and worn down, and she was on the verge of giving up.

I thought that would be the hardest time my mom and I would go through. But fast forward to April of 2025. My mom was about a year and a half out of chemo, and I had to call my mom and tell her, “You just beat cancer, but now I have it.” Different kind. Totally different treatment plan. But I had to tell my mom that I had cancer. That was one of the toughest phone calls.

Discovering the thyroid nodule: Initial symptoms and dismissal

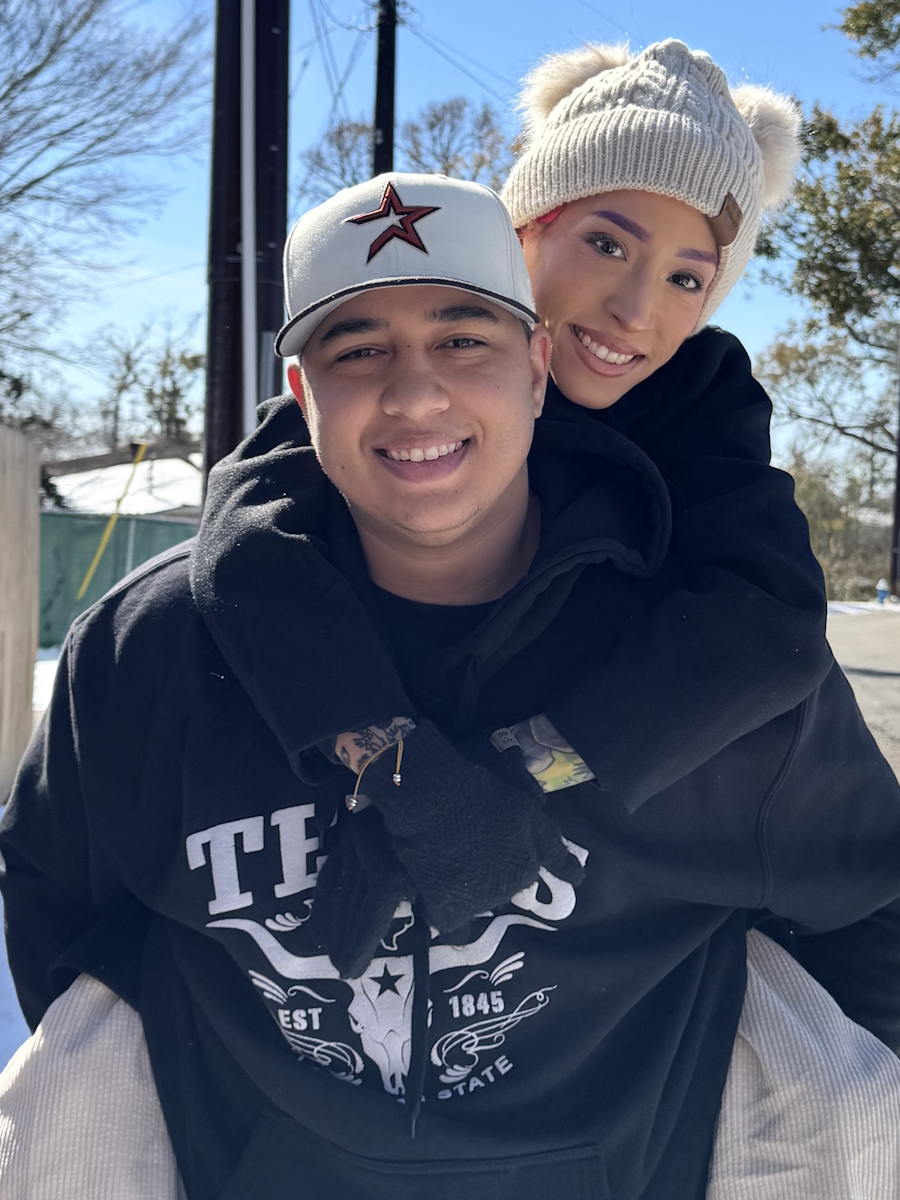

There are thousands of miles between her and me, and my family and my closest best friends. But I had my husband. I had his family here and our chocolate lab, Sage, who is truly our daughter. In April 2025, I went in for surgery to have a 5.5-centimeter nodule removed from the left side of my thyroid. They would have to remove the whole left side of my thyroid because that mass had basically compromised it.

What happened, though, was that I thought it was benign. I thought it was nothing. I didn’t even think twice that it could be something like cancer. Even though I was connected to cancer in so many different ways, not once did I think it was anything but benign. That’s because multiple doctors told me that it was nothing, that it was just a benign thyroid nodule, and there was nothing I needed to do about it.

The mass was impacting my day-to-day. It was compromising the way I slept. If I was working out or doing a certain exercise, it was impacting that. It was getting so big that I felt, at times, it was choking me, and it had also become pretty noticeable. I would look at pictures of myself, and I would just be like, Oh my gosh. This thing is so huge. It’s getting so big.

It took me advocating for myself and pushing to get a surgery and get it taken out before I was ever taken seriously. Things were said to me like, “Are you ready to have a scar? It’s benign. Why do you want it out?” Not once did anyone say to me, “Oh, we should biopsy this,” or “Should we look further into this?” It was so frustrating to me at that time. I just wanted it out. Thankfully, I got it out. Before I even had time to process that there had been cancer in my body for multiple years, it was gone. The cancer was gone, essentially, before I even knew it was cancer. And that is why I have spent a lot of time thinking about other people.

From storyteller to cancer patient: The guilt of “the good cancer”

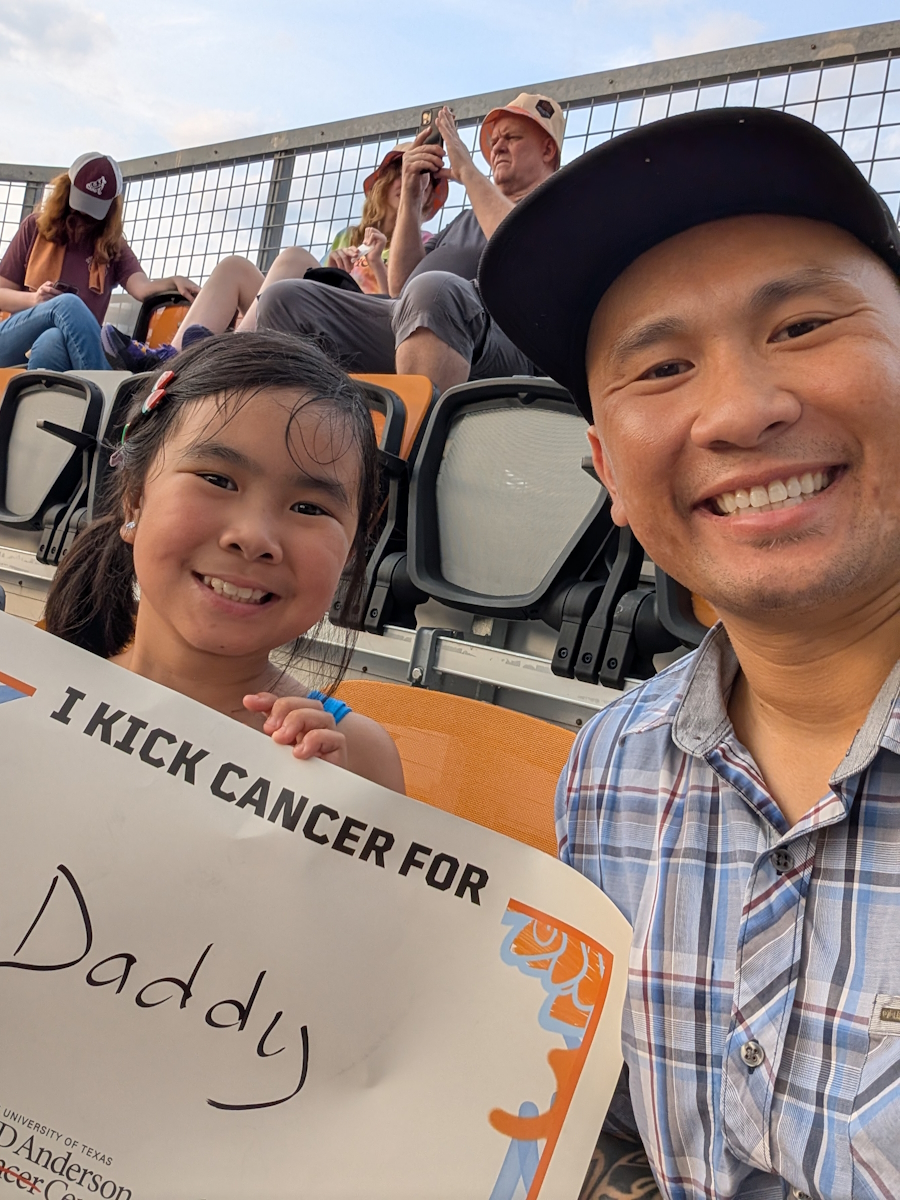

Less fortunate people are people who go through hours and hours of chemotherapy and radiation. The treatment that my grandma many years ago went through and suffered through. To me, having a cancer that is very treatable and has a very straightforward treatment plan… that guilt is something that I’ve carried ever since my diagnosis. And it’s not only what my grandma went through, or what my mom went through; it’s what hundreds of people I’ve talked to who’ve had cancer have gone through, because I’m a storyteller here at The Patient Story.

I went from telling stories, listening, and truly gaining so much knowledge and life lessons from people because they were brave enough to come to The Patient Story, reach out, or answer a message that we had sent them and share their stories. With that, for me, comes a lot of guilt. Because I’m so lucky. I’m so lucky that even though the cancer was in my body for a while and I didn’t know it, it still didn’t spread. But I talk to incredible humans every single day who have it so much worse. I’ve spoken to people who have passed away. People who have relapsed and their cancer has come back. People who have lost a loved one to cancer. People who are in active treatment and they’re still mustering up the energy to do an hour-long interview with me. These stories are so deep, so personal, that I struggled to figure out if my story was impactful enough or worth telling.

I’ve come to realize that everyone’s story is so special. Everyone’s story is different, and in every story, there’s a lesson. There’s something about life that you can take from that. So that’s why, for the first time, I’m sitting down, and I’m telling my story from the very beginning.

My life before cancer: A career in sports broadcasting

I’m originally from a really small town in Illinois. About 800 people, 30 kids in my graduating class. Yes, some are still my best friends to this very day. I have an incredible family. Some of them still live back in Illinois: my mom, my dad, my stepmom, and my siblings. I have an older sister who lives in Texas, a younger brother who lives outside of Omaha, Nebraska, with his fiancée, Mallory. And then I have two bonus siblings. One’s a freshman in high school, and one is a sixth grader. I’m so grateful for my family.

From a young age, I was always the girl who wanted to get out of the small town. That was no secret to anybody. I took school very seriously. I took extracurriculars and sports very seriously, and it led me down a path where I went to the University of Iowa. I became a sports broadcaster, and I really thought that that was going to be my life. It started in Iowa with The Daily Iowan, and then it transformed into my first real adult job in Grand Forks, North Dakota. Then I came to Spokane. That’s where I met my incredible husband, Justin. He is truly the light of my life, and I’m so lucky to have found him.

It’s a very typical story. He slid into the Instagram DMs. He was a coach; I was a sports reporter. I did a story on a team he was coaching, and next thing you know, it’s seven years later. After Spokane, though, I went on to Denver, and I covered professional sports, and I’m so thankful for that time because it really showed who I wanted to be professionally and where I wanted my life to go. I say this all the time, but my husband would have followed me to the ends of the earth if I had wanted to continue in sports broadcasting. But what I realized was I thought I was in love with sports — and I am — but I’m more in love with storytelling.

I wanted to just talk to people. I wanted to share their stories. I wanted to make an impact. That was the biggest thing for me. So I decided to get out of sports broadcasting. My husband and I moved back to Spokane, Washington. He grew up about two hours away, and we started creating our life here.

I could not be more grateful for where we’re at in our lives. We love the Pacific Northwest. We take our chocolate lab, Sage, hiking and swimming. We love camping. We also love showing people around the Pacific Northwest, with my brother and his fiancée, Mallory, being our biggest frequent fliers.

The lump appeared: Dismissed by doctors for years

When I was in sports, and I was in Denver at Fox 31, that’s actually when the lump appeared. I had just turned 26, and we decided to do a karaoke night — one of the greatest pastimes of my husband and me. We went out and karaoke’d, and the next morning, I found the lump. It was quite small, so I thought it might be a lymph node or something similar. But I immediately went to the doctor. Blood work. Ultrasound. No follow-up needed. The mass was presenting benign, so it was out of sight, out of mind.

I just continued with my life, and it wasn’t until a year later that my husband and I returned to Spokane. My girlfriends and I went out. My husband was our designated driver that night, and we’re on our way home, when one of my really good friends pointed out to me, “Hey, do you know that you have a lump in your neck?”

To be honest, it was kind of the first time someone had pointed it out to me. I know she did it just looking out for me and just wanted to make sure I knew. It hit really close to home for her because her dad had thyroid cancer. So she did it with the best intentions. I just said, “Yeah, I actually had it checked out a year ago.” But her bringing it up made me go and get it checked out again.

So, new doctor, new established care here in Spokane, because we had just moved back here. I went and got it checked out again. Blood work and ultrasound again came back. No follow-up needed. But at that point, I noticed that the lump was getting bigger. It was growing — not at a rapid rate — but it was growing, and it started to hinder my day-to-day life.

It was really strange. Then there’s this one picture. My dog and I are sitting on a log camping, and I looked at the picture, and I was so embarrassed. I was dumbfounded. I turned to my husband, and I’m like, “This thing is so freaking huge, and it’s embarrassing. How did I let this go on for so long? There is clearly a huge lump in my neck.” I was so mad at myself. I’m like, “Okay, we’re done. This is it. We’re getting this out.”

So I got a referral to an Ear, Nose, and Throat specialist. With specialty care, it took a while to get in. I finally get in, and I see this doctor. She brought up the ultrasound. She was like, “It presents benign. It doesn’t look like anything. It’s your choice to get it out.” And man, talk about pressure. It’s your choice to get it out. Keep in mind, I’ve never really had any major surgeries. Wisdom teeth? Yes. Broke my tailbone when I was younger, but I had not had a serious surgery, and it was just so casual. “It’s your choice to get it out.”

I’m like, “Okay, well, I’m getting it out. I can’t take pictures like this anymore. I can’t have it be super noticeable like this.” It’s not like people were pointing it out left and right, but if I pointed it out — if I was like, “Hey, I have this huge lump on my neck” — they’d be like, “Oh my gosh, I never even noticed.” That’s also at the point where my mom was like, “You need to get it out.” I don’t know if she had mom instincts or just cancer instincts, but she was also pushing me to get it out.

So I scheduled the surgery for January 2025. My referral from my insurance didn’t go through the morning I was supposed to have surgery. They were like, “You could just come in and have it done and just chance it.” I’m like, “No, no, medical bills are expensive. That’s not happening.” So, because it was non-emergent, it got pushed back to April 2025.

The surgery and the shocking MyChart discovery

The surgery was scheduled for April 18th. Two weeks before that, I had just turned 30. My husband planned this incredible trip to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. We went and had the most incredible time. We stayed an extra day, and if I could go back and relive that day, every single day I would. The only thing that was missing was our dog. She obviously didn’t come with us, but if I could go back to that day, I would, because it was the most incredible day, and we had no idea what life was going to throw at us.

Granted, keep in mind, I still had this lump. It’s noticeable in the pictures. So in a way, I’d go back to that day, but then there’s also a part of me where I’m like, Oh, there’s cancer in your body. So you wanted to get it out. But again, I didn’t know at that time.

So we went home. We settled in. I had surgery on April 18th. My husband took me. It was an outpatient procedure. Very straightforward. But even before my doctor and surgeon came into the room, I told my husband, “She’s very nonchalant, she’s very casual, just heads up.” And she was. There was no indication this could be anything more. There was no talk of a pathology report. And I know why doctors do that. I know why care teams do that. I mean, it was presenting completely benign on an ultrasound. So what would make you think that it’s anything more than that? I don’t know. I wish that they had known that, or I would have gotten a biopsy, but I wasn’t that educated at that time. I mean, I was, but I wasn’t.

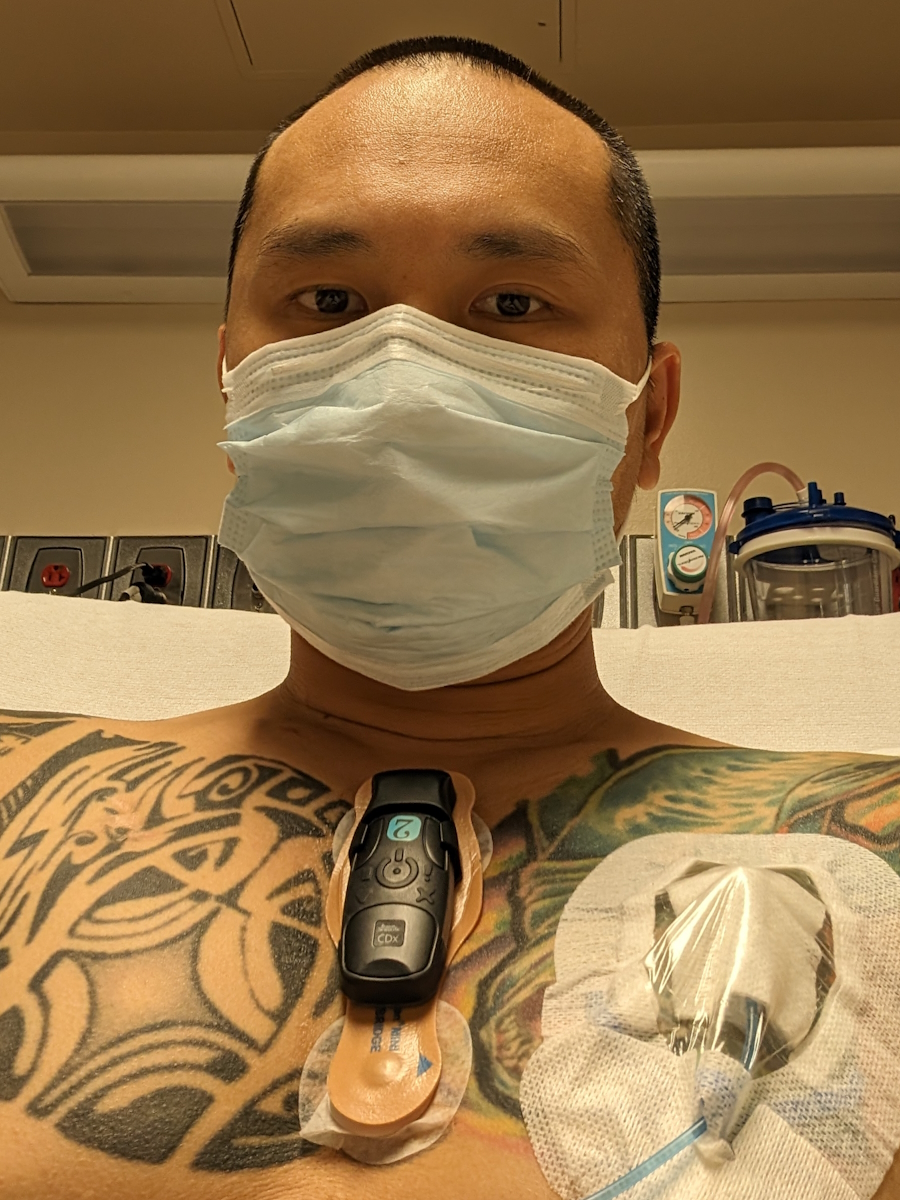

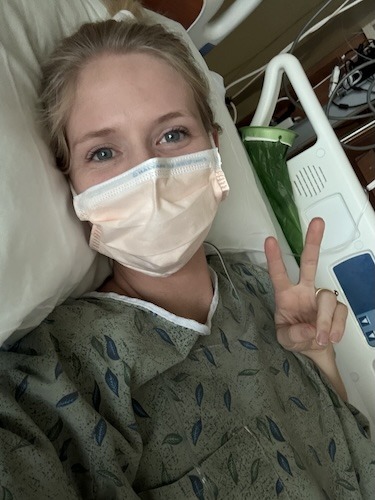

It was a very straightforward surgery. My husband said the surgeon came out and said everything was good. We got it all. She’ll be waking up soon. I went home so quickly after I woke up — it was like 20 minutes, and I went home. I was anxious to get back to working out and getting back into my routine. I just had a partial thyroidectomy, and it is a pretty straightforward procedure. I didn’t think about the pathology report. I didn’t think about any of that until my mom brought it up. She said, “When are you going to get your pathology report?” I said, “Oh, I have no idea.” I didn’t even really think about it.

That morning, the morning that I found out it was cancer, was a Monday. I had just been cleared to start working out again, and I started training for a seven-mile race known as the Bix. It’s this huge race near my hometown in Illinois, and my mom had asked all of us kids to come back and run the race with her to celebrate her being out of chemotherapy. No evidence of disease, and just celebrate her. So I started training that morning. I was so excited.

Then that night rolled around. I’m sitting on my couch, my husband’s in the kitchen cooking dinner, and I see a message in MyChart pop up. Human instincts: Open it. And for me, I didn’t know that opening it was going to be anything other than, “It was benign. It looks good. Glad you got it out.”

But I opened that MyChart message, and the first thing I see is carcinoma. I instantly knew what carcinoma meant. Cancer. The mass was freaking cancer. It wasn’t benign like I had thought for three years. It wasn’t benign. Like I was explaining to people and telling people so they wouldn’t freak out. It was f****** cancer. A cancer type that I had no idea about because there was this word “oncocytic” in the verbiage. I didn’t know what oncocytic meant. It said “Oncocytic Carcinoma of the Thyroid Gland.” So connecting the dots, it’s thyroid cancer. Oncocytic. What the heck does that mean?

I just burst into tears. My husband stops in his tracks, and I just yell it out: “It was cancer!” My husband drops everything, turns the burners off. He’s like, “What are you talking about?” I showed him the message. It was such a devastating moment. I felt like such a fool. I had taken videos before the surgery and even after, really honing in on the word “benign” because, again, I just didn’t want anyone to freak out. I didn’t want anyone to think anything else. But I was just saying the things that had been told to me for three years — that it was benign.

My husband and I — I mean, obviously, he’s so upset. We go into my office. The irony. I’m sitting in my office at my desk, The Patient Story sign behind me, and I am living in a moment that I’ve actually heard before. I’ve had people tell me in interviews, “I found out I had cancer through MyChart.”

No one — no one — should ever, ever find out that they have cancer through MyChart. It is so devastating. I know that it’s not the doctor’s fault. It’s the system. The system definitely has some things to work on. My husband and I sat in my office chair and we were googling words, and then I had to call my mom.

Navigating treatment: Second opinions and radioactive iodine

We went on a walk with that same friend who had said, “Hey, do you know you have a lump in your neck?” We went on a walk with her and her husband. We told them, and then we didn’t really tell anybody else. I did call Stephanie, the founder of The Patient Story, because I’ve always been so transparent with her about my mom’s situation. I started at The Patient Story two months after my mom was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Then I’m working at this incredible healthcare organization that primarily focuses on cancer, when I myself am diagnosed with cancer. So why not go straight to someone who’s so well-connected and really gets it?

Stephanie and I had that conversation that night, and I felt relieved in a way, just knowing that my job was going to be there. I could have space. She was connecting with people she knew who specialized in endocrinology and thyroid cancers. So it was a tiny bit of relief that I felt.

The next day, I instantly started researching second opinions because I had had conversations with people who educated me on second opinions, who taught me that getting a second opinion is important. How blessed was I to be so privileged to know to get a second opinion, specifically at a comprehensive cancer center? I mean, that knowledge is invaluable. I can’t even describe how lucky I felt, even in a moment of crisis, trauma, and drama. It was very traumatic to be going through what I was going through, as it is for anyone who gets told they have cancer, regardless of the type.

I came across the Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle. I didn’t care that it was 4.5 hours away. I just really wanted to have a second set of eyes on my pathology report, and just help me navigate what the next steps would be. I called Fred Hutch. I got connected with an incredible nurse navigator, and she was so kind. She got me an appointment without even a referral. She just put me on the schedule, and the wait times were pretty long. But it actually worked out because when you have a partial thyroidectomy, you have to wait a certain number of weeks to see if you have to start taking thyroid medication or not. Usually, you don’t — it’s like 15 to 20% who have to.

But it was going to be about four weeks from the surgery to finding out I had cancer to being seen at Fred Hutch. And the timeline was similar to providers here in Spokane. They were presenting my case to a tumor board, where they all get together and discuss special cases. Because of the size of my tumor — 5.5 centimeters — I wasn’t calling the mass a mass anymore or a benign nodule. I was calling it a tumor. They wanted to present it to the tumor board. They wanted to do genetic testing on the tumor to see what the next steps would be.

Those four weeks were so incredibly hard for me. My husband gave me so much grace, of course, but I can only imagine how he felt during that time because I was a mess. The waiting was horrific. I just wanted answers. I wanted a plan because I’m such a planner.

I went to Fred Hutch four weeks after my surgery. They were so kind. They provided incredible services. I met my endocrinologist, Dr. Roth, and she is incredible. All she had to do was look at my pathology report to know what the next steps were. And that was a full thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine treatment. That’s what I needed. I needed to just know what the next steps were and how I could just get past this. I really wanted it to be a chapter in my life story. I didn’t want it to overtake me, and that’s exactly what we did.

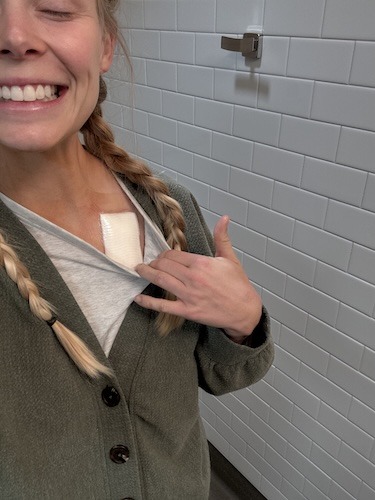

On June 10th of 2025, I got the rest of my thyroid removed. So, a complete thyroidectomy. At that point, they wanted to get rid of my thyroid, any remaining thyroid cells, because the subtype of thyroid cancer I have — oncocytic — is a rarer, less common subtype. It doesn’t happen in a lot of cases, and it can be aggressive. So it was: get the rest out.

During that time, though, I had lost my voice and was struggling to come back. So there was a little bit of how do we push this back more? My husband and I traveled to Fred Hutch — you know, that 4.5-hour drive — we’re so lucky to have the means to do that. I remember sitting with my surgeon, and she was laying it all out there. She was very honest, very kind, very gentle, but so honest about the possibilities, especially because my voice was gone. Come to find out, it was just like an inflamed nerve or something. It wasn’t my vocal cords, which was the fear.

During that wait — oh my gosh. Stephanie told me from the beginning, “The waiting is going to be the worst.” And something I’ve heard in interviews I’ve done is, “The waiting is going to be the worst.” It was agonizing to have all these wait times. I was just kind of sitting in it, and finally got the rest of my thyroid removed.

And then you have to wait eight weeks to do radioactive iodine therapy. So this is the midst of summer. My husband and I are very active. We’re very go-go-go. So I’m recovering from surgery. I’m trying to get back into my routine. I ran that seven-mile race that I had originally started training for before I found out it was cancer. I ran that race with my family and my mom, and it was so amazing and celebratory.

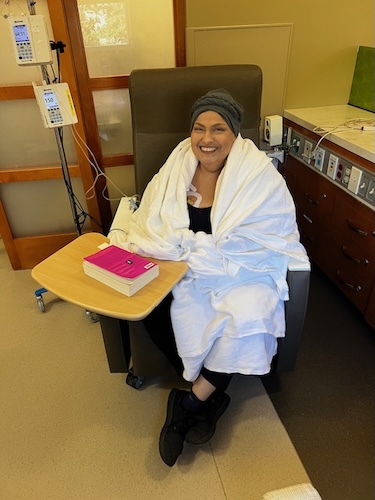

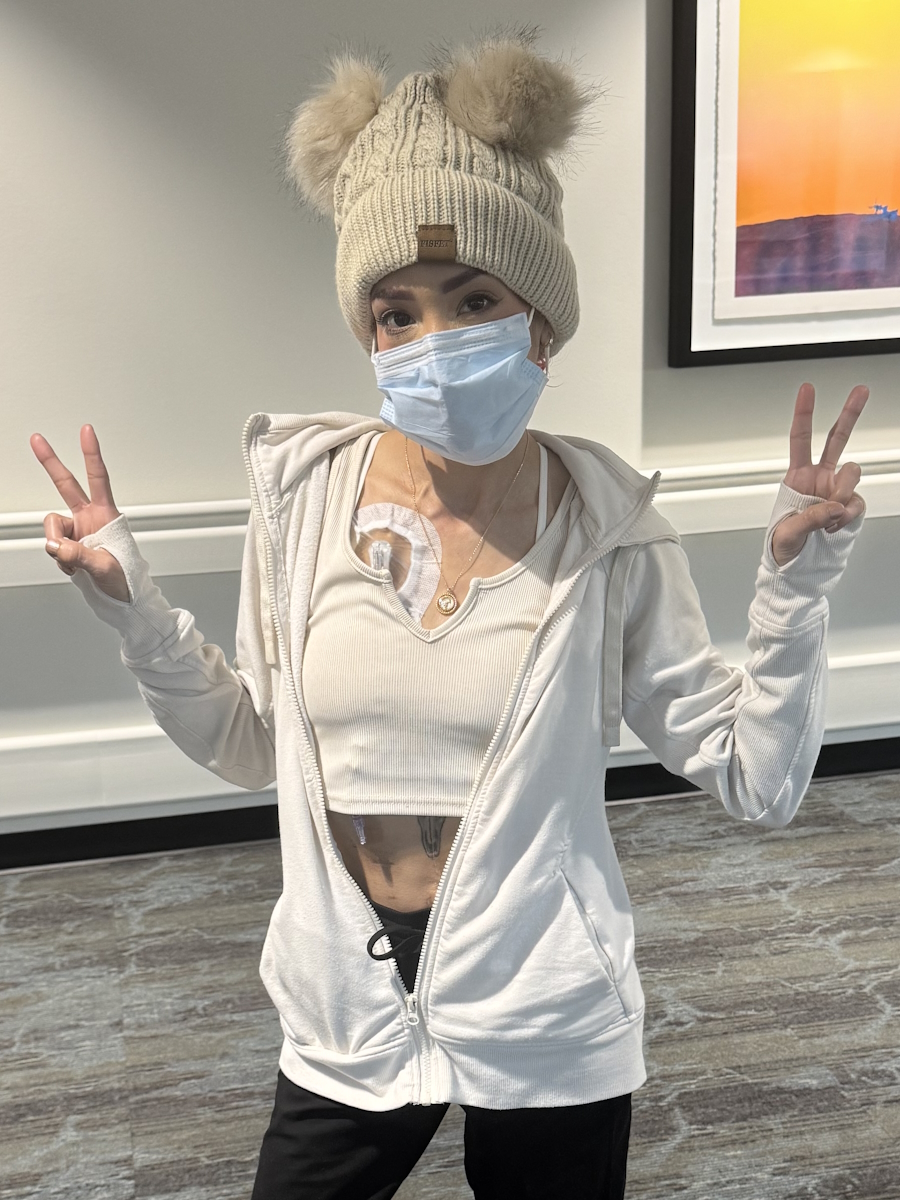

Then we get to radioactive iodine. That was in September of 2025. Again, that process is very straightforward. It’s just so lucky to have the care team I have. It’s a lot of appointments. It’s a low iodine diet. That’s not that fun. I couldn’t eat cheese for like three weeks. It was very sad. I make the jokes because I’ve just figured out that laughing and smiling through this has been kind of the best thing for me.

The mental toll: Body image, anxiety, and fertility

I’ve had moments, of course, of darkness and sadness, and just trying to figure out how to navigate this. So I get through radioactive iodine that involves a three-day isolation process. I was isolated from the outside world in a Fred Hutch facility for three days, and then I came out and got a scan and saw where the cancer was. It was contained in my thyroid bed, but it was more than they anticipated. So I did get a little bit of a higher dose of radioactive iodine.

Now I’m at this phase where it is follow-ups and blood work, and going to Fred Hutch for ultrasounds. What I’ve come to find out is that the surgeries were scary again. I hadn’t had a major surgery before; I had two in one year. And then radioactive iodine was a little sketchy. You know, you just take this pill. And I had a couple of side effects that were out of the ordinary.

Then you get to this part where I’ve been in, and that is processing what has happened to you and what you’ve gone through. In a way, I’ve had to kind of figure out who I am again. She was never really lost, but she’s gone through some things, as we all have. Cancer being a big one, being a caregiver to a parent, going through cancer, and then other life things.

I think after the radioactive iodine treatment, I found myself very anxious and struggling mentally. I couldn’t get myself into a good rhythm. I was living on a short fuse, using my husband as a punching bag, which is not fair at all. And all of this while keeping in mind I don’t have a thyroid anymore, which controls a lot of your hormones, your metabolism, different things like that. You’re taking a pill now. 5:00 a.m. every single day, my alarm goes off, and I’m taking my thyroid medication. That within itself is a total mind f***.

I just felt like I was slipping a bit. I was just not being my best self. And I’ve struggled with anxiety for a long time. I don’t know if anyone else feels this way, but I swear the older you get, the more anxious you become. It just becomes more apparent to the point where I would get numb, my hands would get numb. Sometimes, the side of my face — I was having physical symptoms of anxiety. I just felt… I didn’t like myself. I hated myself. And I would use that language on myself sometimes. Sometimes I’d say it out loud to my husband. “I hate myself. I hate my body.” It felt like body betrayal. What I went through. How did I not know? For three years, cancer was growing inside my body.

Then I got it out, and I started on this thyroid medication, and then I started having body image issues where I had gained weight. I would look at myself in photos, and I would speak so horribly to myself. So horribly to myself. And I hate that I did that. I hate that I was telling myself mean things about my body and about how I looked.

It was like an identity crisis in a way. When you’re a sports reporter and a sports broadcaster, and you’re on TV every single day, you’re looking at yourself, and you’re judgmental, and you’re being told things. And then you’re not on TV anymore, and you go through a big thing like cancer, and your body just is a little confused, and your mind’s confused. I don’t think I was giving myself enough grace in that moment. And it’s something I’m really trying to work on. I just hated the way I felt, the way I was treating my husband, my family, my friends. It was like a “fake it ’til you make it,” but my husband was seeing the real thing of how I was feeling, and that was really, really hard.

Another layer to this is that when you receive radioactive iodine therapy treatment, you can’t get pregnant for a year. And 2025 was the year my husband and I had discussed starting to explore the idea of starting a family.

It was at the point where early 2025, I was telling people, “Ooh, Justin and I are going to start trying. I’m going to be 30. We’re going to start trying. So excited.” Lesson learned: shouldn’t have done that. And it wasn’t like we were actively trying when I was diagnosed with cancer because we were not. But I wasn’t on birth control, and I had to go back on birth control because of radioactive iodine treatment. If I were to get pregnant in the next year, it would be very dangerous.

So I was also having a bit of a reality check; maybe Justin and I weren’t ready in that moment or in 2025, but it was taken away from me as a woman. Oh my God, it’s so hard. I’m so grateful to still have the ability to hopefully carry a child someday if we decide to do that, because I know not everybody gets that chance, and people struggle with fertility issues and that whole situation. My heart goes out to all of those people. To have it taken away from you, even for a year, was really, really sad. And you’re so happy for your friends who are getting pregnant for the first time, or with their second babies. Everyone knows I love being Auntie Taylor. But that dynamic was difficult. It really was difficult.

Healing and advocacy: Why your story matters

So I was processing all these emotions of hating myself, hating my body, body betrayal, not being able to start a family with Justin, and I got into a really deep, dark place. And then I started to climb out of it. At the start of 2026, I really committed to myself: to my body, to routine, and doing things that make me happy. I’ve started this morning routine that I’ve just lived and breathed by since the start of 2026, and I just feel really, really good.

Another big thing — and not something I’ve expressed a whole lot, though some of my friends and my mom, of course, my family knows — but I started taking anxiety medication. That was a huge step for me. So again, my body is going through a lot. Thyroid medication, I’m back on birth control, and anxiety medication. I’m really taking care of myself. Of course, I slip in a cheeseburger now and then. Everyone who knows me knows that I’m a sucker for a cheeseburger. But truly, I’ve shifted. And it’s not just physical for me. It’s truly mental. It is a mental game for me at this point, and I’m so proud of myself for taking care of my mind and my body and just recentering myself.

As I’ve recentered myself, one thing that I talked about at the beginning of my story was the dynamic of Is my identity… is my story important? Is it important enough to share? Is it worth sharing? Am I ready to just close this chapter? All those questions swirling around in my head, and thyroid cancer is looked at as “the easy cancer,” and yada yada.

I am fully aware that it is a very treatable cancer. It is very straightforward, and I’m forever grateful for that. It doesn’t mean that my story is not worth sharing, though. I’d be lying if I didn’t say I was terrified to share my story, especially on a platform where I interview so many people who have it so much worse than me, and I always keep that perspective in my mind. But those very people taught me to advocate for myself, to get second opinions, to share my story, and to be brave enough to share my story.

There are things in the story that I haven’t expressed out loud. So in a way, this is my own little personal diary. Looking back at the person who was diagnosed in April 2025, to the person I am now, she’s the same girl. She’s just grown up a little bit, and I’m really thankful for that. It’s truly a full circle moment to share my story and to continue sharing stories of others who are going through cancer, no matter what stage, no matter what type, no matter where you’re at in your story.

I’m so blessed to be able to have a voice and to have a platform like this. Timing is truly everything. And no matter what you believe in, everything does truly happen for a reason. At least I think. I found The Patient Story — or rather, they found me — three months after my mom’s colorectal cancer diagnosis. And then plot twist: I get cancer in the midst of working for a cancer company. I was exactly where I needed to be at the exact time of my diagnosis. And now what can I do? I can share my story. I can continue spreading that language and those words that people have taught me before about second opinions, about advocating for yourself, and making sure that you’re just truly taking care of yourself — mind, body, spiritually — however the dominoes fall.

One thing I’ve just been so lucky to do as well is because of The Patient Story. People in my personal life have come to me and been like, “Hey, I was diagnosed with said cancer,” or “Hey, I know someone who was diagnosed,” or someone sending me a message and saying, “Hey, I have the same subtype of thyroid cancer as you.” I mean, this is a domino effect. Sharing your story, sharing your light, sharing your truth is so incredibly important. You don’t know who it will reach or who it will impact. And I just think that’s really, really special.

What I want people to take away from my story and my experiences

There are three things:

One: Advocate for yourself. If you can’t find someone who will — a family member, a friend, a colleague — please fight for yourself and your body and your mind and what you’re feeling.

Two: Second opinions are so important. I know that comes with a lot of layers: insurance, travel, finances. But if you have the ability to get a second opinion or even just ask someone or try to connect with someone who can ask their oncologist, please explore a second opinion.

Three: Your story matters. If you are terrified, just like I was, to share your story fully, please don’t. Because I can promise you that your story is important and no story is the same.

Thank you so much for watching my patient story. It took a lot of guts, a lot of bravery to share this, but I’m so grateful to have this platform to do so. And if my story resonated with you at all, I’d love to introduce you to one of our team members, Ali. She shared her story, and it’s queued up for you right here. Please make sure you subscribe to The Patient Story community, where you’ll see me interviewing so many incredible people with their inspiring stories. We want you to join The Patient Story community because we’re humanizing cancer one story at a time, and always telling people and reminding people that you’re never alone.

Inspired by Taylor's story?

Share your story, too!

More Thyroid Cancer Stories

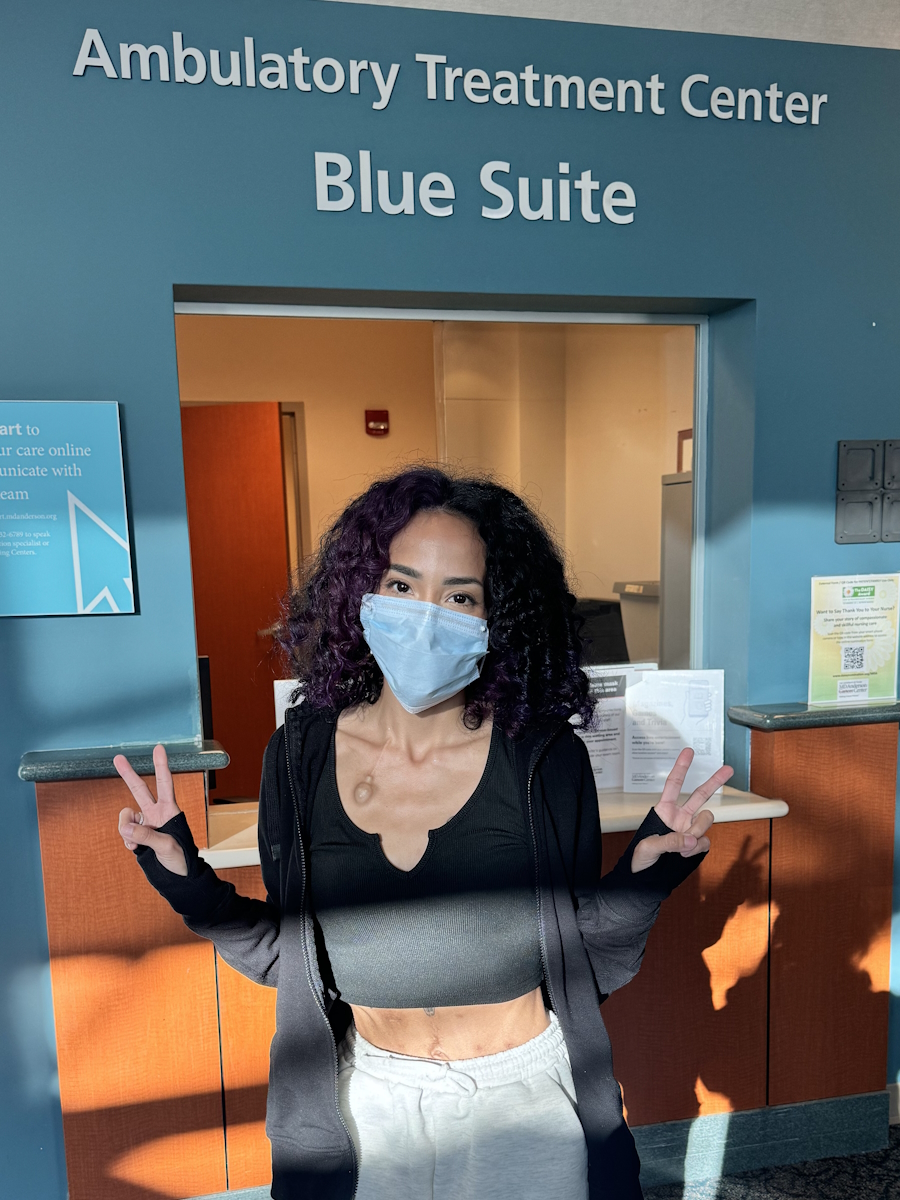

Taylor Scheib, Thyroid Cancer (Oncocytic Thyroid Cancer)

Symptom: Appearance of a visible lump on the neck

Treatments: Surgeries (hemithyroidectomy, completion thyroidectomy), radiation therapy (radioactive iodine)

...

Cyndi F., Thyroid Cancer (Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma), Stage 1

Symptoms: None per se, nodules discovered during thyroid examination

Treatments: Surgeries: hemithyroidectomy, isthmusectomy, mid-neck dissection, parathyroid transplant

...

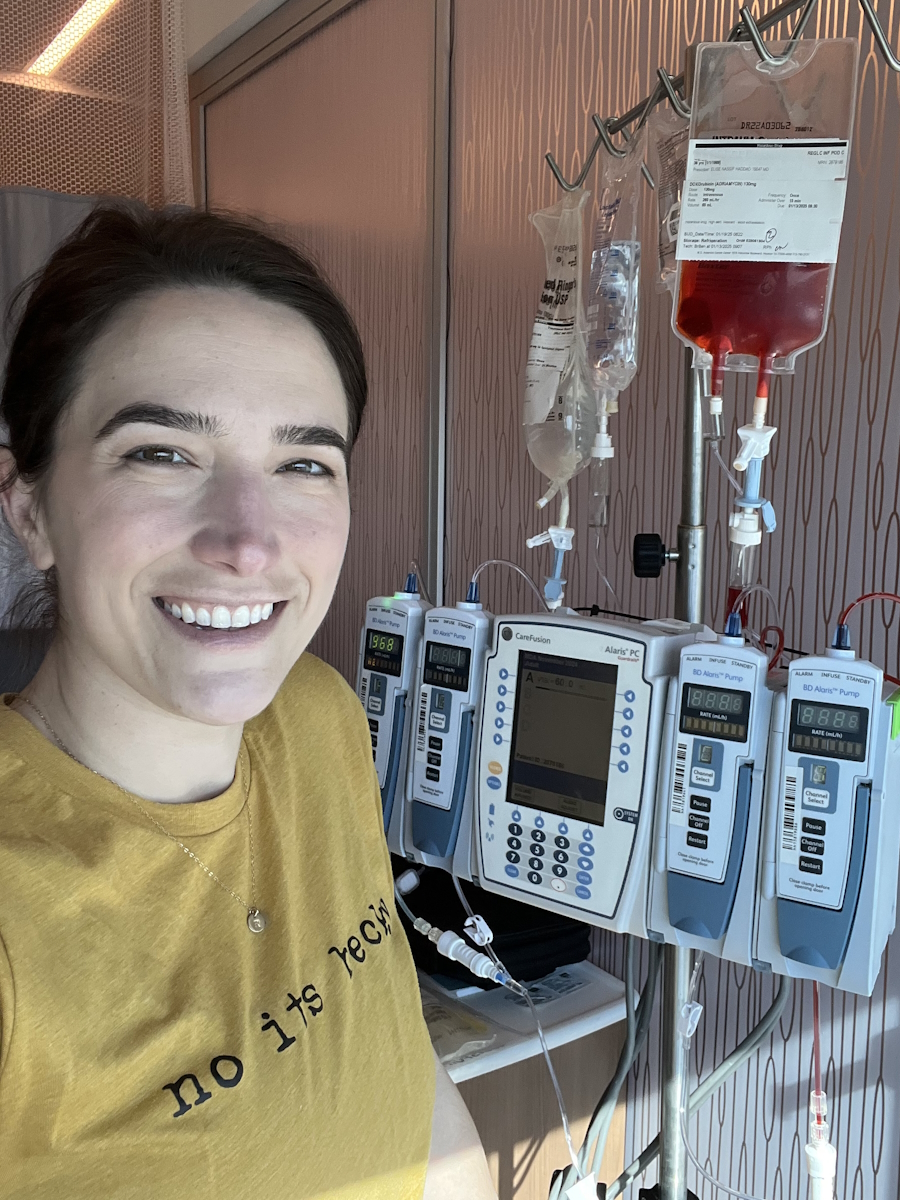

Laura C., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 4 (Metastatic), Grade 1 to 2; Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

Symptoms: Incidental finding after hysterectomy (follicular lymphoma), thyroid nodule detected on imaging (papillary thyroid carcinoma)

Treatments: Immunotherapy (rituximab and lenalidomide or R² regimen), surgery (thyroidectomy)

...

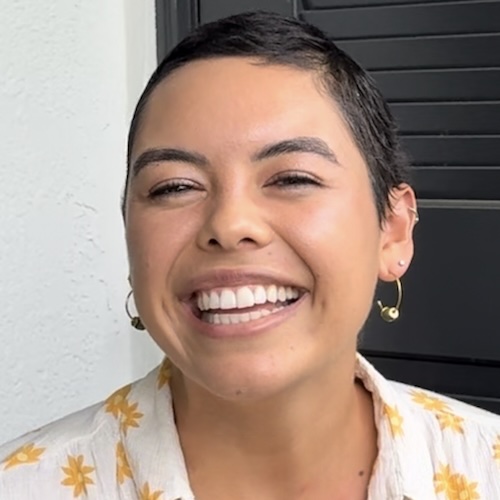

Alyse V., Thyroid Cancer (Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma, Tall Cell Variant, Metastatic)

Symptoms: None per se, lump discovered during thyroid examination

Treatments: Surgeries (neck dissection, lymphadenectomy), integrative therapies

...