Living Scan to Scan with Follicular Lymphoma: Laura’s Experience with Watchful Waiting & Treatment Decisions

When a routine hysterectomy revealed two tiny gumdrop-like tumors, Laura had no idea she was about to enter a stage 4 follicular lymphoma experience. She walked into her surgery follow-up appointment alone on her wedding anniversary, expecting a straightforward recovery discussion. Instead, she walked out with a blood cancer diagnosis that had never shown up in her labs or imaging and the surreal experience of calling her husband.

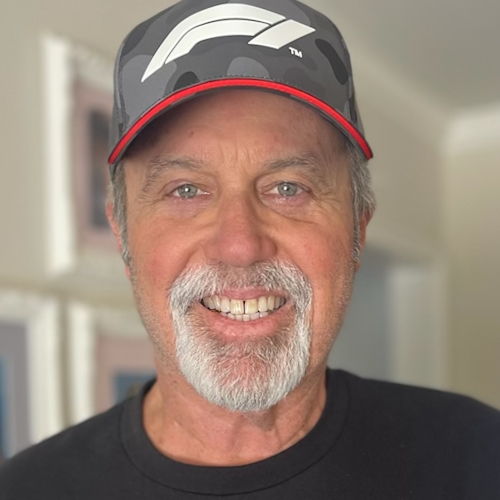

Interviewed by: Ali Wolf

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

In the weeks that followed, shock and logistics collided alongside learning what follicular lymphoma (FL) even was. Initially, Laura met a local lymphoma specialist who reassured her that she was likely to live with this and die of something else, but also raised chemotherapy as a first option. As an asymptomatic young mom, this did not sit well.

Through online research, a Facebook group, and another patient’s story, she learned about watch and wait, an approach that closely monitors the disease without immediate treatment, and sought a second opinion at an MD Anderson-affiliated clinic. Other terms for this observation-based plan you may hear are “watchful waiting” and “active surveillance.”

This new specialist walked her through current guidelines and confirmed she was an ideal candidate for observation. That decision shaped the rest of her stage 4 follicular lymphoma experience, centering on quality of life and the long game.

Watch and wait, however, was not passive. Laura describes living scan to scan, consumed by cancer mentally, even while feeling physically well. She leaned on a psychologist who specialized in cancer, her faith, and a close-knit community, including a friend who allowed her to go as dark as she needed emotionally.

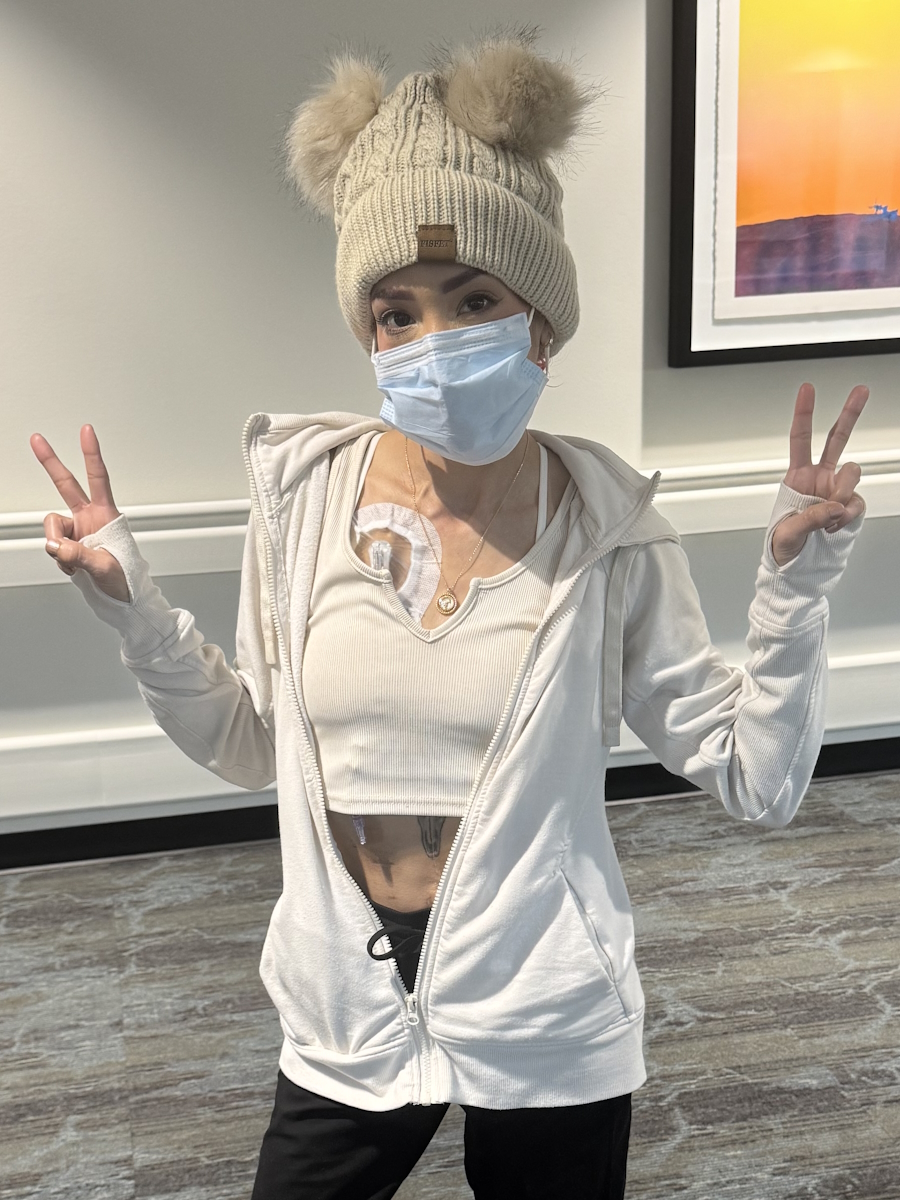

Over time, scans showed slow progression, eventually leading to a course of rituximab-only infusions, then the chemotherapy‑free combination of lenalidomide plus rituximab. The R² regimen brought her into remission for the lymphoma.

Just as she exhaled, surveillance imaging flagged a thyroid nodule that turned out to be papillary thyroid carcinoma, her second cancer in two years. After a thyroidectomy, pneumonia, and nearly a full year of lenalidomide for her FL, her oncologist stopped the medication, prioritizing her overall health.

Today, in remission and back on watch and wait, Laura names this as both a stage 4 follicular lymphoma experience and a family experience, one that deepened her gratitude, tested her faith, and reframed time with her children as something both fiercely ordinary and profoundly precious.

Watch Laura’s story or read the interview transcript below to know more about her story:

- How a routine hysterectomy led to an incidental finding of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, highlighting how some cancers are discovered only during unrelated procedures

- Why Laura questioned the push toward immediate chemotherapy and sought a second opinion at a major cancer center

- How living scan to scan took a heavy toll mentally and spiritually, and how counseling, faith, and a community willing to hold her helped her navigate through her cancer experience

- How a new diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma layered more complexity onto her experience

- What having options, emotional support, and space to ask questions can do to shift a cancer experience

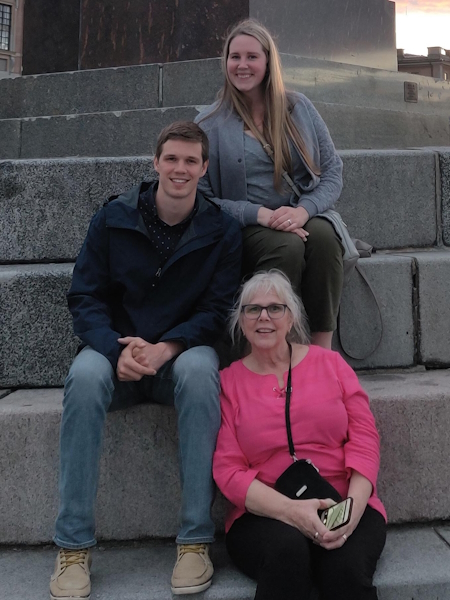

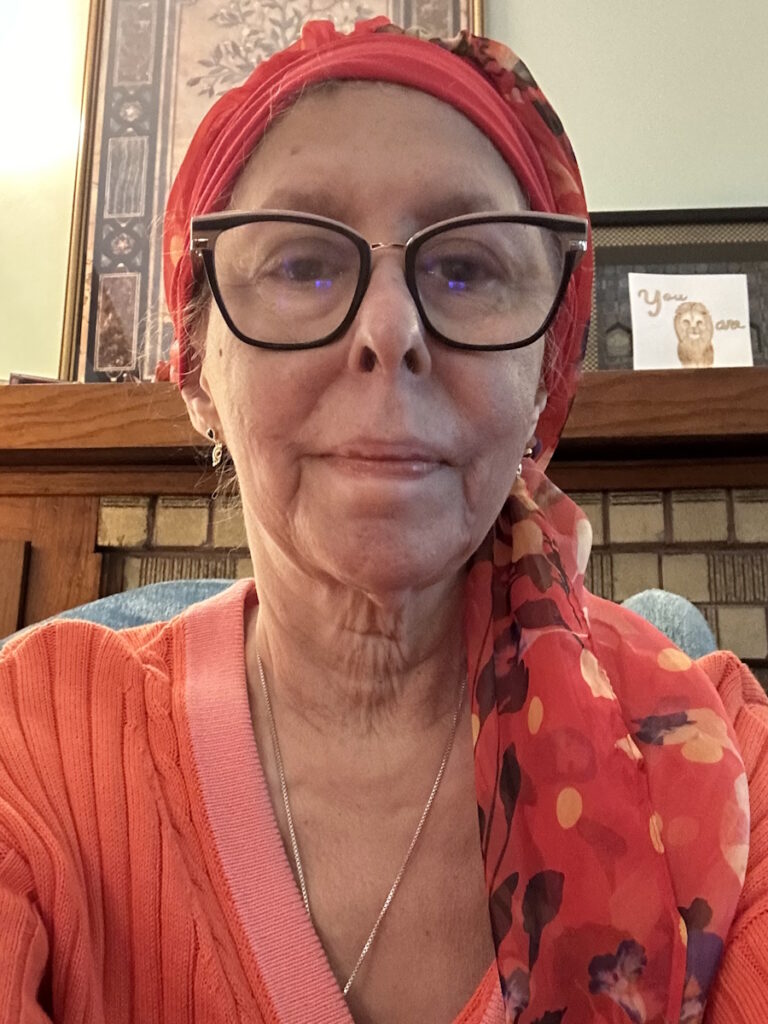

- Name: Laura C.

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 41

- Diagnoses:

- Follicular Lymphoma

- Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

- Staging:

- Stage 4, Extranodal, Grade 1-2 (follicular lymphoma)

- Symptoms:

- Incidental finding after hysterectomy (follicular lymphoma)

- Thyroid nodule detected on imaging (papillary thyroid carcinoma)

- Treatment plan:

- Watch & wait / active surveillance

- Immunotherapy: rituximab and lenalidomide (R² regimen)

- Surgery: thyroidectomy (for papillary thyroid carcinoma)

Thank you to Genmab for their support of our independent patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- Incidental Lymphoma Finding After Hysterectomy

- Shock, Anniversary News, and First Calls for Support

- First Cancer Center Visit and Initial Prognosis

- Researching Treatment and Seeking a Second Opinion

- Learning From Other Patients’ Experiences

- Realizing Stage 4 and Choosing Watch and Wait

- Managing Anxiety, Faith, and Mental Health During Watch & Wait

- First Rituximab-Only Treatment and Mixed Response

- Lenalidomide, Rituximab, and Achieving Remission

- Ringing the Bell and Moving Into Recovery

- Treatment Options, Future Therapies, and Hope

- Telling the Children and Family Growth

It did not show up in my blood work, any ultrasounds, or any other tests we had done up to that point. We had absolutely no idea.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

Incidental Lymphoma Finding After Hysterectomy

When I got there, the doctor came in and said, “Good news. The hysterectomy went well, but I found these two little things.” He described them looking like gumdrops. They were very smooth, round on the top, and flat on the bottom. They were about 1 to 1.5 centimeters. He wasn’t sure what they were, but his exact words were, “I didn’t think they looked insidious.” But to be thorough, he sent everything off for a biopsy. When the pathology came back, it was grade 1 to 2 follicular lymphoma.

He said, “I don’t know anything about this. No one in my practice has ever diagnosed something like this. We need to get you in to see another doctor.” I felt like I ruined his day because he felt so awful not knowing. If this was within his realm, like ovarian cancer, he could have at least told me something, but I could see it on his face. I felt bad for him having to tell me this. He said, “Don’t go online. Wait until you see someone. But this is where you’re at.” Then he sent me out the door.

When I say it was an incidental finding, we had no idea. It did not show up in my blood work, any ultrasounds, or any other tests we had done up to that point. We had absolutely no idea.

Shock, Anniversary News, and First Calls for Support

There was shock in that room. We never said “cancer.” I knew lymphoma was a blood cancer, but I knew nothing about it. I didn’t know what this meant, but he reassured me.

We had a family friend, an older gentleman, who wasn’t feeling well after a family get-together, so he and his wife went home. She ended up taking him to the emergency room that night, and they literally said he was eaten up with cancer. It was absolutely everywhere. My doctor said, “That’s not you.” He was able to reassure me that that’s not what he saw. He said, “Until you see a specialist, don’t panic. You’re still my patient.” It meant a lot hearing him say that.

He said, “You can call this office, even if you just need to talk. You’re my patient. I’m handing you off to another doctor, but you’re mine, so come back with anything you need.” Even then, I didn’t feel alone.

We decided that we weren’t going to talk to the kids about it until we knew more, met with the doctor, and had a good idea of what we were facing.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

I don’t think I panicked until I got to the car and had to call my husband to tell him it was cancer. I think I just blurted it out. He thought I was coming home. We both had the day off, so we were going to hang out because it was our anniversary. What a great anniversary gift.

I didn’t know the difference between non-Hodgkin’s and Hodgkin’s. The one thing I knew was that a friend we knew had cancer and it was everywhere. I very quickly shared with a very close group of girlfriends who I had and said, “I don’t even know what this means, but can you please lift this up in prayer as we figure this out?”

I knew that I didn’t have the bandwidth to do this by myself. That’s not who I am. I needed some people. I called my husband. We talked the whole way home. I said, “He’s referring me to someone. I don’t want to wait for the referral. Let’s get on our insurance and find out who I can see. We need to get going quickly.” By that point, I was pretty hysterical. It’s blood cancer. It can’t be good. My mind was spinning.

My husband, being who he is, asked what I needed. I said, “When I get home, I’m going to need a few minutes before I see the kids.” We hunkered down in the bedroom, just the two of us. He put a movie on and I cried. You don’t know, so you worry, “What will this be like? Will I lose my hair? How awful will treatment be? What if I don’t beat this? What do we tell our kids?” We word-vomited all of that, even though we didn’t have answers.

We decided that we weren’t going to talk to the kids about it until we knew more, met with the doctor, and had a good idea of what we were facing. Then it got logistical. We had the 4th of July coming up and our kids had a dirt bike event. A friend invited us over for July 4th and we were trying to schedule appointments and find someone. We went through our insurance and found out that I could be seen at a cancer center in Colorado Springs, where I live. We scheduled quickly and they were able to get me in within a week or two, which doesn’t sound so long looking back on it, but it felt like a long time then.

The very first thing he said was, ‘The good news is you’re going to live with this. You are likely going to die from something else.’

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

First Cancer Center Visit and Initial Prognosis

When we walked into the cancer center, there were so many people there, more than I thought would be. Around 40 or 50 people were waiting to see a doctor. I know it’s a cancer center, so there are different specialties, and there was an infusion center, so there were so many people. I was the youngest one by a solid 20 years, which freaked me out. I looked at my husband and said, “I’m going to need a minute.”

I knew we had to see someone, but that was a tough moment for me. I stepped out, got myself together, and came back in to meet with the doctor. He wanted some tests done because all we knew at that point was that it was grade 1 to 2 follicular lymphoma. The very first thing he said was, “The good news is you’re going to live with this. You are likely going to die from something else. You have grandkids, graduations, and weddings to attend.”

I remember having this huge weight lifted off my shoulders, and that we could do this and it would be okay. Then he gave us some information to go over and sent us off to another area in the cancer center to do blood work and imaging. After, we came back and met with him after taking in that initial meeting.

Researching Treatment and Seeking a Second Opinion

He mentioned bendamustine and rituximab, the chemotherapy and immunotherapy regimen, and encouraged me to research my disease, which I did. I stumbled upon Nikki’s story on YouTube, who has done a story on The Patient Story, and very quickly joined the follicular lymphoma Facebook page.

There was so much information that wasn’t quite lining up with what my doctor was recommending. It was not settling for me that I needed chemo so quickly because I’m asymptomatic. It wasn’t showing up in my blood work. I’m healthy. We had no idea this was happening in my body. I knew that chemo would be hard. It didn’t make sense to me that you had to make me sick to make me better. It didn’t fit.

In between appointments, I did a lot of research, watched a ton of videos of hematologist-oncologists and upcoming treatments, and posted lots of questions in the Facebook group. When I went back in, my doctor was not thrilled that I didn’t have a port and hadn’t done the bone marrow biopsy. He was upset with me about that. I said, “I’m not ready,” and he said, “Before I see you at your next appointment, I need you to get those things done.” At that point, I knew I wanted a second opinion.

He said, ‘You are a perfect candidate for watch and wait. Your blood work looks good. You’re healthy. All we know about your cancer is that you have it.’

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

Ironically, someone I knew also knew someone with follicular lymphoma. It’s not the most common cancer, but this woman reached out and said, “Do you know there’s an MD Anderson office in Colorado? I didn’t choose to do treatment there, but I went and talked to one of their specialists, and I learned a lot about my disease. You should at least go and meet with them.”

I called and they were able to get me in within a couple of days. I met this lovely man who walked in and said, “So you’re here for a second opinion on whether you need a bone marrow biopsy. You don’t. Are we good? See ya.” Then he laughed and said, “Just kidding, just kidding. But no, you don’t need a bone marrow biopsy. Let me show you why,” and turned the computer screen around.

He showed my husband and me the absolute newest recommendations for follicular lymphoma. It’s like a flow chart: say yes, go here; say no, go here. We got to the end, and he said, “You are a perfect candidate for watch and wait. Your blood work looks good. You’re healthy. All we know about your cancer is that you have it. We don’t know if it’s getting better, worse, or hanging out there, not causing any problems. I think we should wait.”

We asked a few more questions and he said, “Can I assume I’m your doctor now?” I said, “Yeah, you’re my doctor.” It has been amazing. It’s a small clinic with an amazing team, and that’s where I landed. I’ve been there ever since.

Learning From Other Patients’ Experiences

I’m going to give Nikki a lot of credit. I can’t remember if it was specifically her story, because, if I remember correctly, she did the radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment and it was quite aggressive. She couldn’t be in the same house with her kids, so she stayed with family. It did put her in remission. She very clearly said she wished things hadn’t gone so fast, that she could have taken time to learn about different treatments, or watch and wait, and slow the pace down a little bit. I don’t think she regrets her treatment, but she wished it had slowed down.

Because of the Facebook group she started, that was where I heard so many people say, “I was on watch and wait for six months.” “I was on watch and wait for three years.” “I was stage 4 and I was on watch and wait for five years.” All of these stories were of people who got a little bit of time to live with this before they had to decide.

Learning about the disease and the fact that we’re playing the long game, and knowing that chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and surgeries are hard, we were trying to decide what hard we were willing to live with.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

Realizing Stage 4 and Choosing Watch and Wait

I don’t specifically remember anyone in that timeline saying what stage I was, but through research, I realized I was stage 4 because it was outside of my lymphatic system. Those two little things that my doctor removed were not lymph nodes. They were little tumors, so I knew that was stage 4.

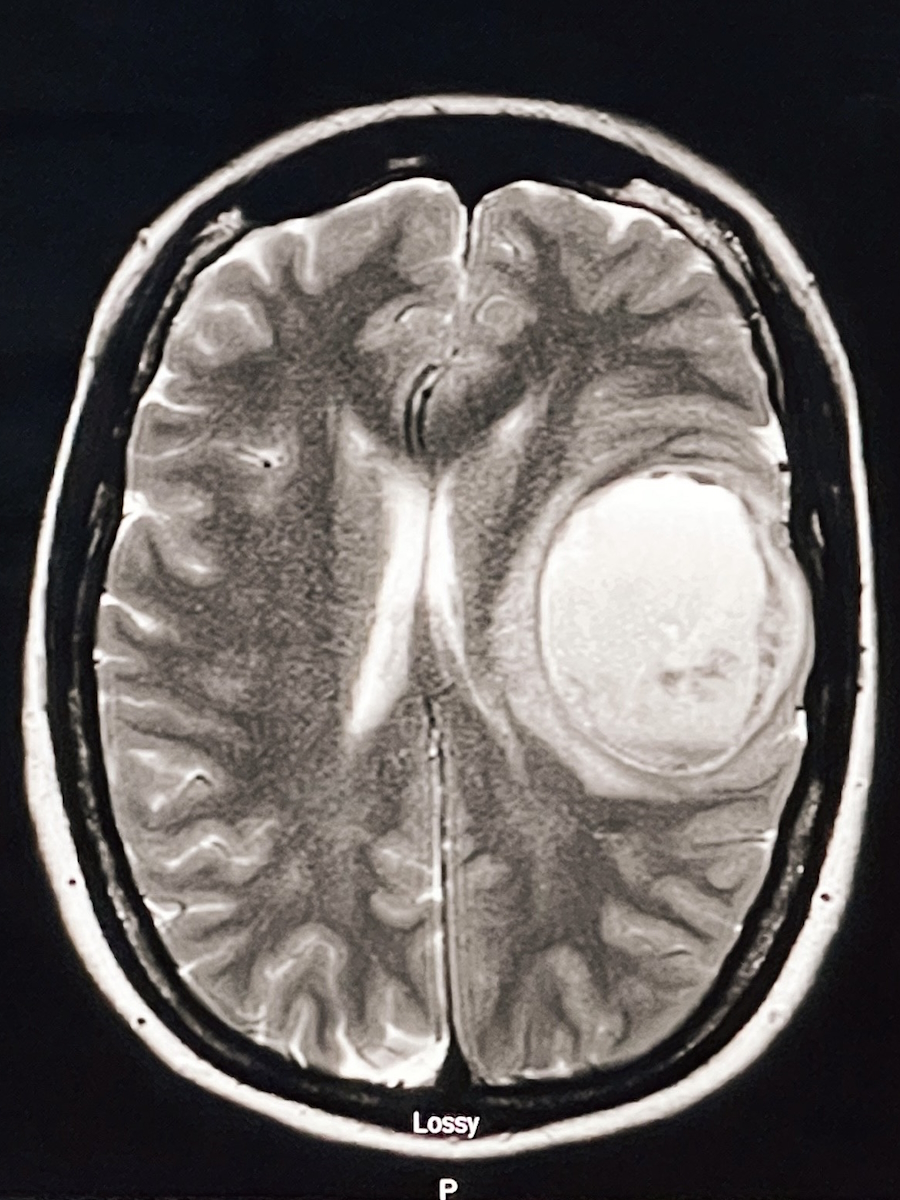

By that point, we had scans and knew it was in my bone marrow. We knew it was all over my pelvis and in my abdomen. There was nothing above my diaphragm, but it was everywhere otherwise. I didn’t want chemo; I knew that. I knew some people had done watch and wait.

My husband is a father of four children and a police officer, so he’s able to walk into situations and fix them. At first, he said, “Just do the chemo. Let’s get this out of your body and be done.” But then, sitting at MD Anderson, learning about the disease and the fact that we’re playing the long game, and knowing that chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and surgeries are hard, we were trying to decide what hard we were willing to live with.

I realized I’m unlikely to have only one round of treatment. How do we play this game conservatively, keep me healthy, not make me sicker, and preserve my quality of life? That’s what I heard from MD Anderson the whole time: it’s your quality of life; we have to keep you living. Hearing that and understanding why we were going on watch and wait was huge.

After that appointment, even my husband said, “Wow, we’re not going to do anything.” I said, “Are you okay with that? I’m okay with this. Are you okay with this?” He said, “He’s so knowledgeable. If he’s okay with this, if your doctor thinks this is the best course, then let’s do it.”

From that point on, watch and wait involved blood work and CT scans with contrast every 90 days or so. It was terrifying every time I went in. I also have crappy veins, so they have the ultrasound guy waiting to guide it in. I got to know my CT team well and knew which ones to ask for, so that was funny.

You go in and wait. Do I get three more months? Do we have to start treatment? How much worse has this gotten? Is it doing anything? Watch and wait was a huge blessing, but I did feel like you live scan to scan and you wait. I was consumed with cancer. I’m on watch and wait, and we’re so grateful, but we don’t know what this is going to look like in three months, in six months, or in five years. My kids are young.

I’m a Christian and I believe God is ultimately in control. He knows my story, He’s the one writing it, and I have to trust that, but that tested my faith.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

Managing Anxiety, Faith, and Mental Health During Watch & Wait

Thankfully, MD Anderson connected me very quickly with Ashley, the psychologist up at Banner. I saw her weekly for a while, then every couple of weeks, and then less often. She kept reassuring me that everything I was feeling and saying was what all of her cancer patients feel, think, and worry about. We worked on a lot of grounding, being in the moment, and not wondering all the time.

I would do simple things with my kids — go to the grocery store, go to a dirt bike race, watch fireworks on the 4th of July, make a bed — and think, “What if this is the last time I get to do this with my kids? What if this is the last one? What if I’m not here when my kids graduate from high school or get married?”

I’m a Christian and I believe God is ultimately in control. He knows my story, He’s the one writing it, and I have to trust that, but that tested my faith. I have a great group of friends and one of them straight up said, “You can go as dark with me as you want. I can carry that for you.” We were doing some group devotions together and I was leaning into those friendships and my husband.

Communication with my husband was a little different. He was on the side of, “What if I lose my wife?” and he was afraid to say that. Or, “What if you get really sick?” He was afraid to put that on me. We dealt with some of those things separately, which was okay.

I got really mad at God in those early days because of not knowing. Why me? Watch and wait was such a blessing, but it gave me so much time. Time is time, but it felt like it gave me a lot of time to think and sit with it. There were days when it got dark and difficult. I had full meltdowns during scan week. But I had friends, communities, and family who prayed.

It was interesting that I could almost feel that on the days when I was the weakest, people would instinctively reach out and say, “We lifted you up. We prayed over this today.” My faith, a great therapist who specialized in cancer and lots of her patients who had been through a watch and wait journey, and learning some techniques helped.

When I would wake up at night, the first thing I thought about was, “I have cancer,” and I would panic. I started praying, “I am a woman of God. I have no fear. That’s not my story.” I would do my best to try to find the calm, though I wasn’t always very good at it.

Because we’re watching closely, we saw one close to my kidney and another fairly large one.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

It was more the mental toll. The amazing thing about the office I was at was that I had access to a therapist and two nurse practitioners who worked with my oncologist. I would email and say, “I don’t feel great. What are the chances that it’s this?” and they would say, “It’s not. Let’s wait until the next scan.” Or, “That actually does sound a little interesting. Let me reach out to your doctor and get back to you,” and they would either move a scan up or know that one was coming soon.

They never made me feel crazy. Anybody who has been through cancer themselves or with someone they love, you get a hangnail and think, “What if that’s cancer?” You get a headache and think, “What if that’s cancer?” You can’t help it. I don’t think I obsessed so much because I was asymptomatic.

Going into my last scan, the one that determined I needed to start treatment, I was feeling so good. I felt confident this was going to be fine. My doctor and I agreed that if the scan came back looking good, we would move my scans to every six months. In this journey, you get sick of doctor’s appointments. There are so many doctor’s appointments, blood work, scans, follow-ups, and education classes. Until I had my hysterectomy, I was someone who hadn’t seen a doctor in a year. Everything looked good. I did my annual. We were fine.

I don’t think I obsessed so much about symptoms. I did have a freak out in the grocery store because I swore this cancer came from not eating organic food, not drinking clean water, the sheets we slept on, the laundry detergent, the soap, whatever. I freaked out about that. Apparently, that’s also very common.

First Rituximab-Only Treatment and Mixed Response

Regular three-month scan. Everything up to that point had shown some slow progression, but follicular lymphoma is notoriously a slow-growing cancer, grade 1 to 2. I know grade 3 is a different situation. We watched the waxing and waning of my lymph nodes. Some of them had gotten a little smaller and some a little bigger.

I went in for a CT scan in June. My doctor called and said, “This one doesn’t look as good. We have this larger lymph node that’s close to your kidney, and it’s concerning enough that we probably should think about doing some kind of treatment.” That was a telehealth appointment because my doctor only wanted to see me every other scan.

Typically, with this, we can get some time. My husband and I were together, and it was probably time. Again, I wasn’t feeling anything. My blood work still looked good. But because we’re watching closely, we saw one close to my kidney and another fairly large one up against an artery or something; I don’t quite remember. He said, “We need to shrink those a bit. Maybe not push hard for a remission or anything, but we should probably get these a little smaller. They’re getting a little concerning.”

I reacted to the first round, which wasn’t awesome, but then we managed that reaction and the next three rounds went much more smoothly.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

We had a conversation about what we wanted to do for treatment. Again, thanks to Nikki getting me into that Facebook group, I was able to message my new lymphoma friends and ask, “What would you do? What are my options?” I had researched some things through some hematology YouTube videos as well.

It looked like a lot of people had success with rituximab only. I asked my doctor if that was an option for me, and he said, “Absolutely. Why not? We caught this early. You’re not sick. The best-case scenario is that we get five, six, eight, or 10 months, shrink these down, and give you more time on watch and wait. Or it doesn’t work great and we add something else,” so that’s what we did.

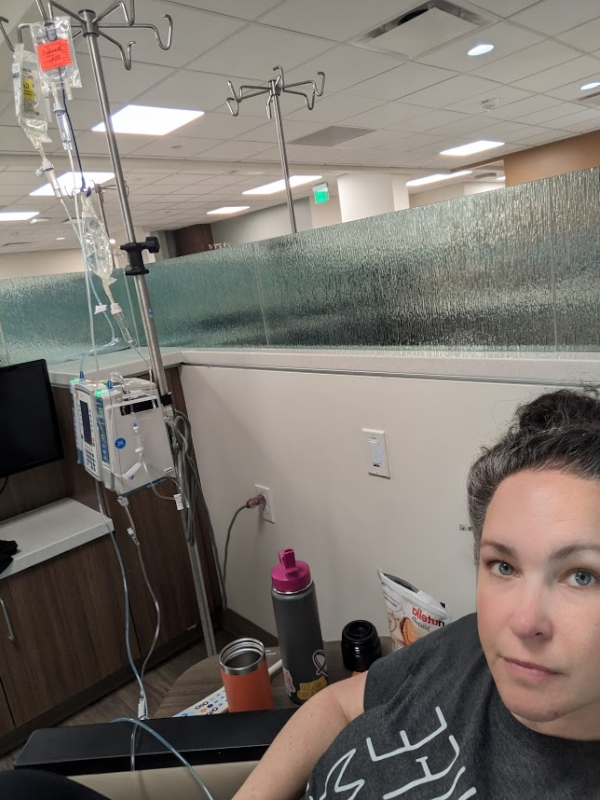

We did four rounds, one round every week for four weeks in June. We did rituximab, and then you have to wait and see if it did anything.

He shared that the standard first line of treatment is bendamustine and rituximab (BR) or bendamustine and obinutuzumab. I knew that. It was very conversational. My doctor has always been like that; it’s a conversation. I found out his daughter was traveling and he was going to be out of town, and we had this going. He started to feel like a friend, which is weird, but I trusted him.

He said, “There are some options.” I interjected and said, “Is rituximab only an option for me?” He said, “It is. It absolutely is.” Then I asked him, “If you and I were friends and we were out having a cocktail, what would you tell me to do?” He said, “At your age, you’re still asymptomatic. I’d do the rituximab only.” So that’s what we did.

We finished at the end of June. It was almost on the one-year mark from my diagnosis. I reacted to the first round, which wasn’t awesome, but then we managed that reaction and the next three rounds went much more smoothly. We did a PICC line to get through that, which was an interesting procedure to have done.

A lot had shrunk, but the one next to my kidney grew through treatment and was causing issues with my kidneys.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

Then we waited from the end of June until six or seven weeks later. We did another CT scan with contrast to see what was going on, and we got a mixed result. Several of my lymph nodes shrank considerably. Some were back to normal size. The activity in general was a lot lower.

We could clearly see that a lot had shrunk, but the one next to my kidney grew through treatment and was causing issues with my kidneys. I read the report before I saw my doctor. I was Googling nephrology and things I had never searched before. It was clear that my kidney was being compromised as my ureter was being blocked by this lymph node.

We had a convening of my husband and all the doctors, trying to see what we wanted to do. My doctor at that point, again, said, “You have options. We can still do bendamustine and rituximab. We can do lenalidomide.” If I remember right, it was in August that lenalidomide and rituximab were approved for frontline treatment for follicular lymphoma, so my doctor was very aware that they had just become approved, so that was an option.

He said the other option would be to go in and take out that one lymph node. Everything else looked good. “Are you cancer-free? Obviously not. Would there still be other lymph nodes that are growing? Yes. This is a systemic cancer. You need to know this would not be curative.” I understood that and said, “If we can remove this one lymph node and avoid more treatment, let’s give it a try.” He said, “I think it’s a great option. Let’s give it a try.”

We found a surgeon, who looked at the CT scan and said it looked iffy. He said, “If we damage your ureter doing this, then you’re in for more surgeries. I want more imaging. We should do a PET scan.” Between the oncology surgeon and my oncologist, we decided on a PET scan. I was already scheduled for surgery because we knew something surgical was going to happen. Either we were going to biopsy this lymph node or remove it.

I went in for an abdominal, guided laparoscopic biopsy of this lymph node to see. If it transformed, then that would change our whole plan and there would be less discussion about options because it’s a much more aggressive cancer. That was a long wait. The surgery was very painful, the worst that I had had up to that point. I’ve had a couple others.

We continued on lenalidomide, but we did a dose reduction to help manage some of the side effects I was having.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

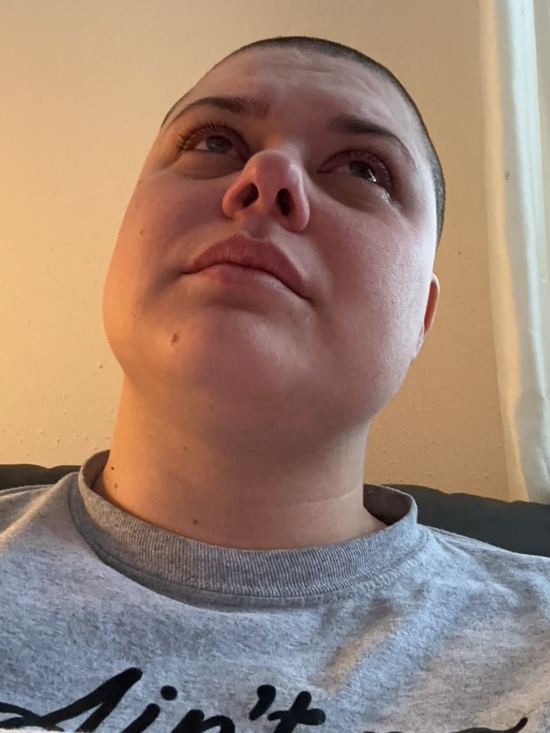

We waited again for more results. I went shopping for wigs because I thought if this was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), I’m going to lose all my hair and I didn’t want to react late. I kept myself busy waiting.

Then I got the call from Dr. Peters, my surgeon, and he said, “I can’t believe I’m telling you this, but it has not transformed. I don’t know why that one didn’t respond to treatment, but it’s the same type of cancer.” The biopsy came back that way. Then we’re back at the meeting with Dr. Shelanski, my oncologist, and figuring out what my options are. Again, he came in and said, “You have choices, Laura. We can do this, this, or this,” and laid it all out. That was when we decided we were going to do lenalidomide and rituximab.

Lenalidomide, Rituximab, and Achieving Remission

He explained that the pro of doing chemo is that there’s a time limit. Six months and you’re done. Lenalidomide meant longer. Rituximab is an infusion, and I did that with oral lenalidomide for six months with scans in between. It was at the three-month PET scan that we saw that the treatment was working, and we were grateful.

The next scan we did was right after I finished the six-month treatment. My doctor said, “There’s some activity, but it’s less than your liver, so I’m going to say this is early-stage remission,” and we were grateful. That was in February. We found a little thing going on in my thyroid, but most nodules are benign, so we weren’t going to stress about that. Everything looked great.

We continued on lenalidomide, but we did a dose reduction to help manage some of the side effects I was having. He said it was a low enough dose that it was still therapeutic. We felt confident about that. We wrapped up three more rounds of lenalidomide that got us into June or July. We did a scan and I was in full remission, praise the Lord. It worked. It was a huge amount of relief.

We keep an eye on things. I live my life with a whole new sense of gratitude.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

I got to share with friends, family, and my kids that this looked good, but there was still this pesky little nodule on my thyroid. We weren’t sure what was up with that, but it was a little more active than it had been.

I’m in remission from lymphoma. I still have three more months of rituximab to do the full one-year course. I’m still taking lenalidomide. We’re doing all these tests on my thyroid, and it came back as papillary thyroid carcinoma — my second cancer in two years.

For peace of mind, we did a scan of my brain because I knew we were pushing remission, and we were probably going to start pushing out some appointments. I wanted to make sure that if I had a headache, it wasn’t cancer. We did that, and it also showed a little bit of something on that thyroid. We opted at that point to do an ultrasound, which said I needed a fine needle aspiration.

I continued on lenalidomide, had my thyroid removed, and ended up with pneumonia post-surgery. I called my oncologist and said, “I’m on two doses of high antibiotics. We’re trying to regulate my thyroid medication. I’m 43, so I’m perimenopausal. How are we going to know what side effect?” He agreed at that point. He said, “You’ve done 11 out of 12 months of a hard medication. It’s more important to focus on getting your thyroid medication straight, so you’re done. You’re in remission. We’ll see you in a few months for some blood work and in six months for a scan.”

We’re essentially back on watch and wait. We’re at the point where we keep an eye on things. I live my life with a whole new sense of gratitude and get healthy. My husband said 2025 was the year for remission, and 2026 is the year for recovery, so that’s where we are.

I’m just thinking about living my life and praying that this remission lasts.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

Ringing the Bell and Moving Into Recovery

It’s been amazing. Nothing is an emergency for my doctor, but I don’t know if it’s good for everybody. He said, “Good job.” I said, “I get to ring the bell,” and so we rang the bell, which was awesome. Then he said, “Okay, we’ll see you when we see you. For blood work, we’ll do telehealth. Then we’ll scan and I want to see you in the office after the scan.” He likes to get his eyes on me every so often. It’s a two-hour drive for us, so it’s not the most convenient trip all the time.

But I feel like I’ve gotten good news after good news this time. You go in and they say, “That fine needle aspiration was what we were hoping,” and you say, “Wait, what?” You hit this point where you think, “Why not? Why wouldn’t there be something else?” Then we got over that big hurdle, the thyroid nodule, and having my thyroid removed. Recovering from that surgery was a lot because I was so immunocompromised. My body had been through so many treatments. That was my fourth surgery. It was a lot and my body was tired. I’m still working, and I love my job, and I want to be active for my kids.

Then we met with an endocrinologist who said, “Based on your blood work, your chance for the thyroid cancer coming back is 5% without radioactive iodine.” My doctor said, “We’ll see you in three months for blood work.” It was such a relief. I feel like we’re getting some space from all of these appointments and I’m not thinking about cancer all the time. I’m just thinking about living my life and praying that this remission lasts, that my body is healed up, knowing that it’s likely this will come back.

That’s the struggle I’ve heard from other follicular lymphoma survivors on The Patient Story and on Facebook: this is my life now. It is something we’re going to watch. I’m grateful for the incidental finding because I didn’t have to get sick. Ironically, five other people who worked in the same building all have follicular lymphoma. It’s very strange. That’s something we’ll be looking into. Some people get really sick. My friend Jamie was one of them. She got really sick before they found out why.

I have the assurance that I’m being watched. I have a fantastic medical team, and I won’t have to get sick. We know what my body is doing, and we know that we can handle it.

All of my kids have seen me unwell… I’ve seen their faith tested and grow. I’ve seen family and friends walk this out with them and care for them.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

Treatment Options, Future Therapies, and Hope

I have an awesome medical team. He knew in August that the medication was an option for me, so that’s the direction we went. Early on, when we first started with lenalidomide and rituximab, we were standing in his office and he leaned into me and said, “Laura, if this PET scan shows that this option is not working for you, we have eight other choices, so don’t panic. We’re going to treat you, and we’re going to keep you living and get you healthy. It sucks that a mom with four kids has to have this, and treatment blows. Treatment sucks. We’re going to get you through this, and we’re going to get you living.” That is a huge sense of peace.

There are options for people living with lymphoma, and those options are changing almost every day. Clinical trials are happening that I am aware of. There are clinical trials my doctor and I have talked about on this journey that would possibly have worked for me, and that is huge. I asked him, “If we know this medication worked for me, if this were to come back, could we do lenalidomide again?” He said, “If it’s at least two years, if we can get a two-year remission out of this, then yes, we can do lenalidomide again. But by then, there could be better options. There could be better medications. There could be curative therapies that are coming, and you’re going to be alive for them.”

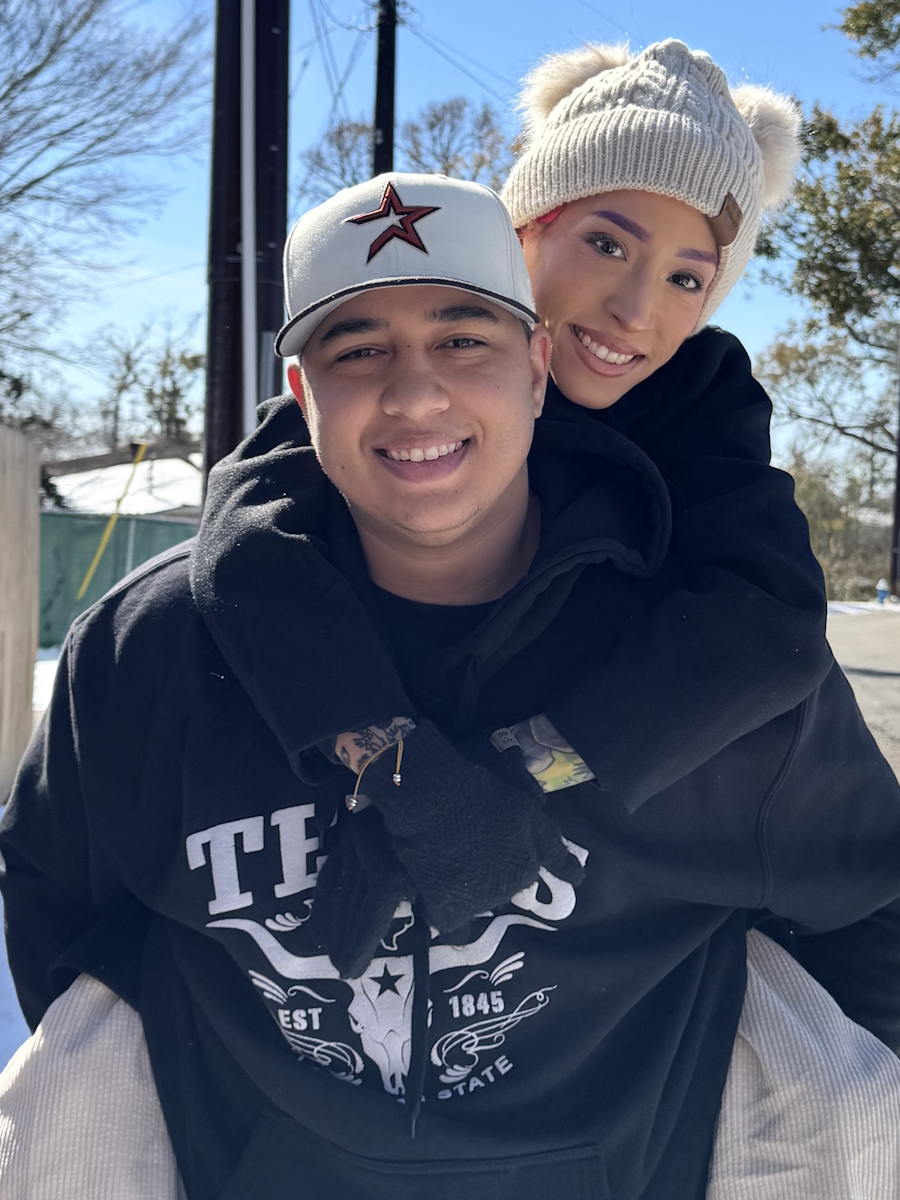

Telling the Children and Family Growth

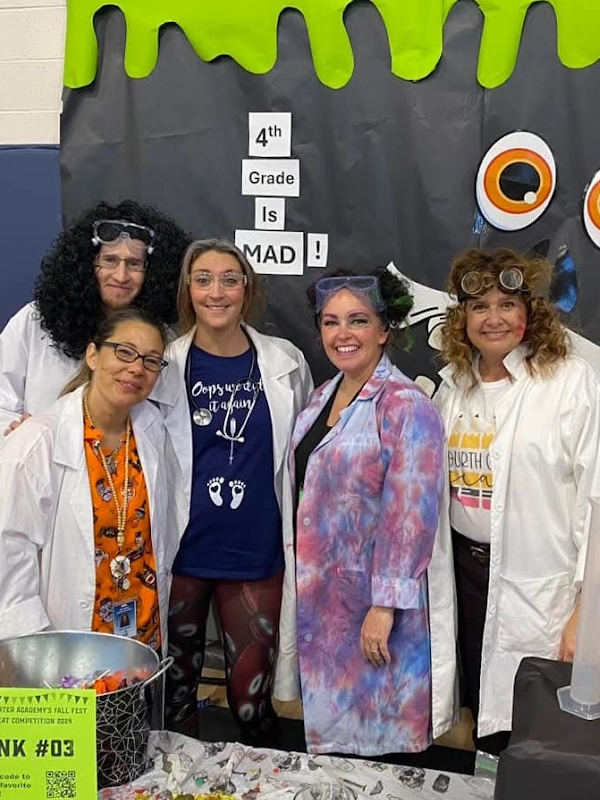

It was difficult trying to decide what and when to tell our kids. When we told the two younger ones, they said, “Oh, okay, can we go finish watching the movie we were watching?” The two older ones had more questions. All of my kids have seen me unwell after infusion days or when side effects were bad. They’ve walked through that with me lots of times, cuddling in bed or sitting on a couch and watching TV.

I’ve seen their faith tested and grow. I’ve seen family and friends walk this out with them and care for them. My kids have seen that it’s okay to be weak and to ask for help, and that we are surrounded by an amazing community who will fold a load of laundry, make a meal, or drive me to an appointment.

I’ve watched them become more independent because they had to. There were days I couldn’t do the things I would normally do. I’ve seen my husband be a better cook. My mom was helping either after a round of treatment or a surgery, I don’t quite remember, and he commented, “I don’t know how she does all of this all the time.”

You can’t walk through something like this and not grow from it.

Laura C., Stage 4 Follicular Lymphoma Patient

The sense of gratitude is maybe a little better there, because you can’t walk through something like this and not grow from it. It was awesome to tell them. I picked them up from school and when we got in the car, I said, “I had my meeting with my doctor, and there’s no cancer anywhere in my body.” That was awesome to get to tell them, because that was basically a little more than two years of not knowing for sure if this would ever go away.

We didn’t get clear margins on the carcinoma, but my blood work looks good. We’re choosing not to do radioactive iodine. I’m struggling a little bit to come to terms with the idea that there might not be a day when I’m officially 100% cancer-free. But according to the scans right now, things look good, which is an awesome thing to get to tell my kids. I’m lighter. I’m hoping it makes them feel a little more at peace with where we’re headed as a family.

Inspired by Laura's story?

Share your story, too!

Thank you to Genmab for their support of our independent patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

More Follicular Lymphoma Stories

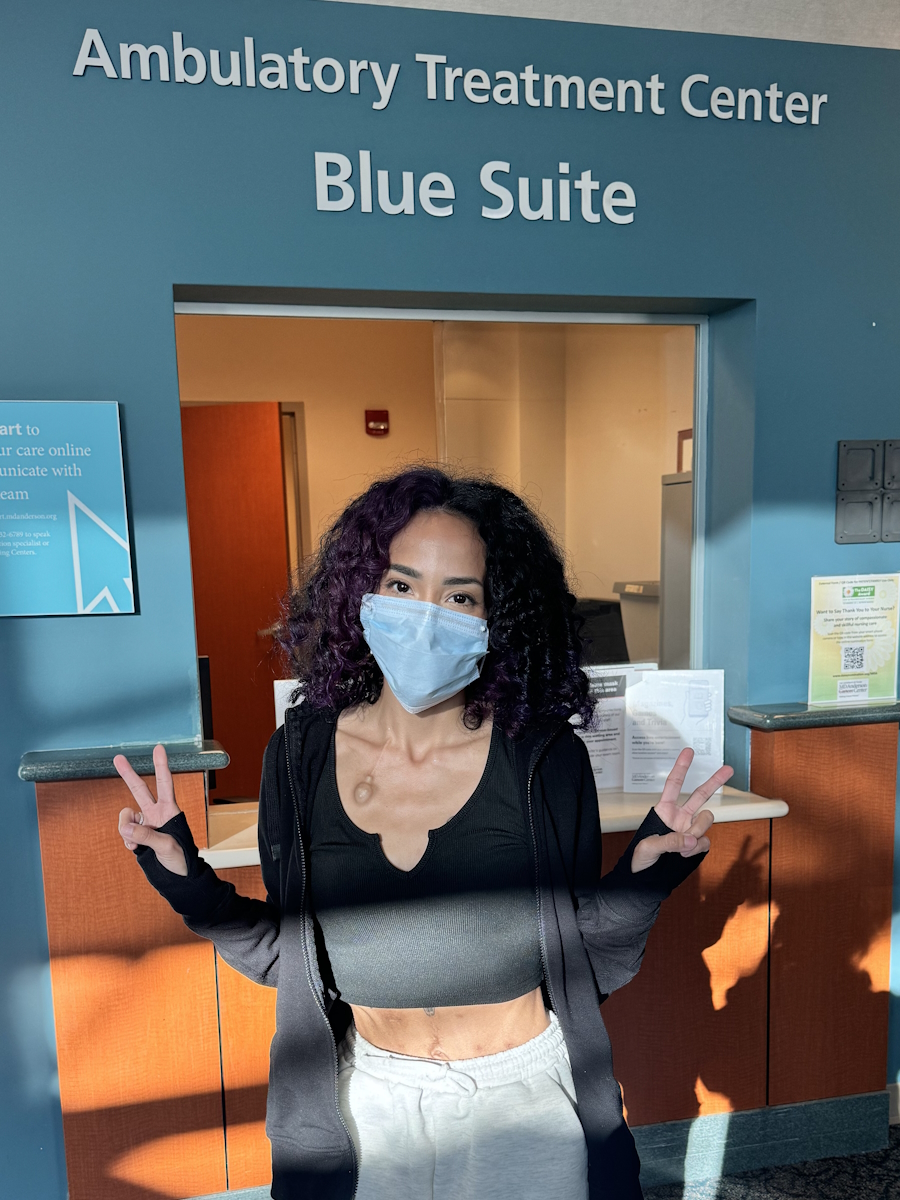

Laura C., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 4 (Metastatic), Grade 1 to 2; Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

Symptoms:Incidental finding after hysterectomy (follicular lymphoma), thyroid nodule detected on imaging (papillary thyroid carcinoma)

Treatments: Immunotherapy (rituximab and lenalidomide or R² regimen), surgery (thyroidectomy)

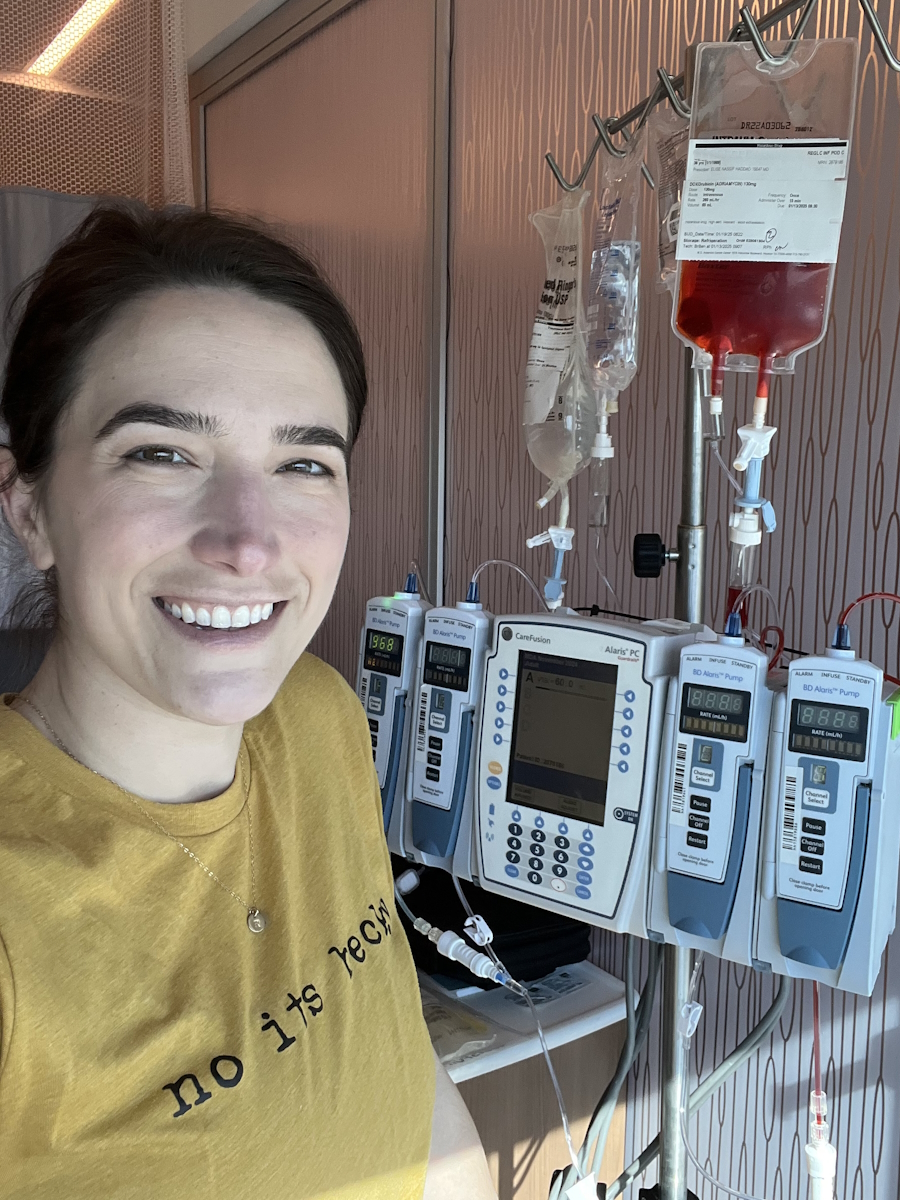

Hayley H., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 3B

Symptoms: Intermittent feeling of pressure above clavicle, appearance of lumps on the neck, mild wheeze when breathing and seated in a certain position

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy

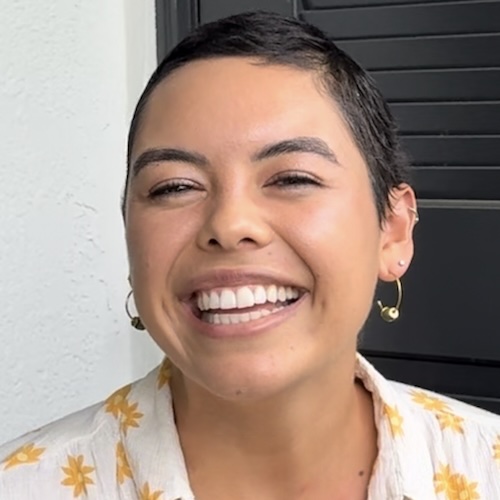

Laurie A., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Frequent sinus infections, dry right eye, fatigue, lump in abdomen

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radioimmunotherapy

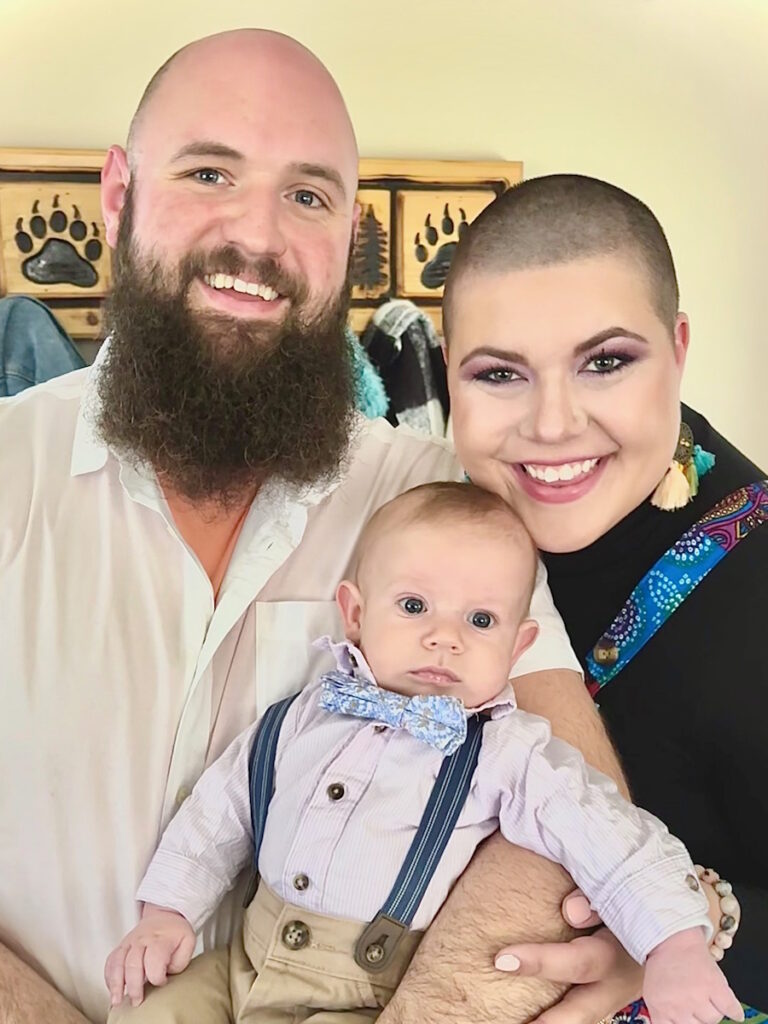

Courtney L., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 3B

Symptoms: Intermittent back pain, sinus issues, hearing loss, swollen lymph node in neck, difficulty breathing

Treatment: Chemotherapy