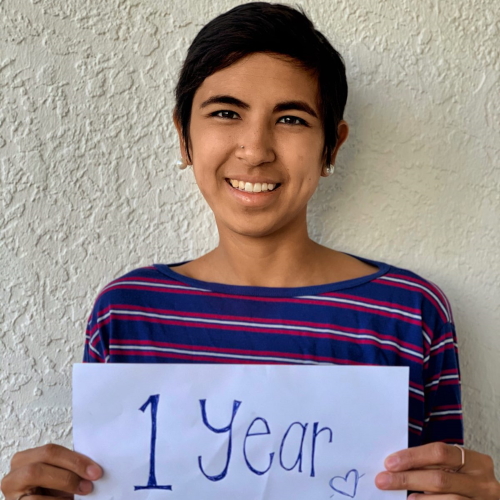

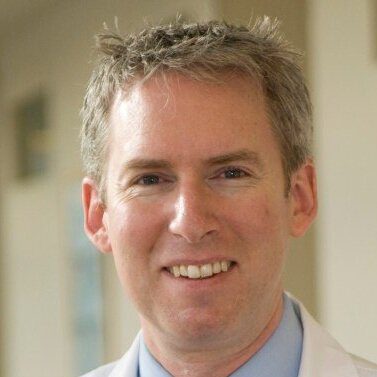

The Latest in Multiple Myeloma with Caitlin Costello, MD

Insights on Dexamethasone, drug combos, IVIG, the MAIA trial, and transplant-ineligible patients.

The American Society of Hematology is the largest professional society of hematology experts, with the goal of researching and conquering blood diseases. The annual conference brings together experts to discuss the latest in research and treatments.

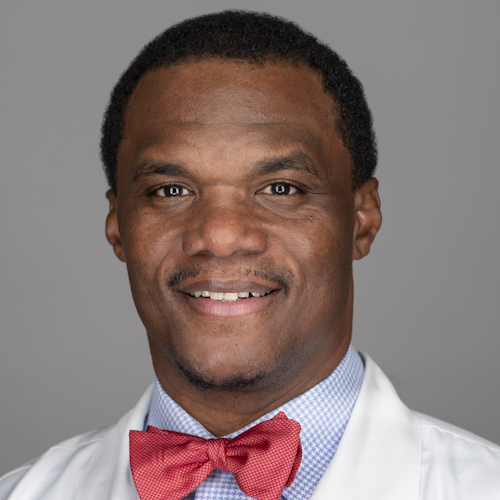

Dr. Caitlin Costello is a hematologist at the University of California, San Diego. She is board certified in internal medicine, hematology, and medical oncology.

Dr. Costello attended the 2022 ASH meeting and shares the highlights discussed, the latest in combination treatment for myeloma, and stem cell transplant eligibility and ineligibility for patients.

- Introduction to Dr. Caitlin Costello

- Who is eligible for a multiple myeloma transplant?

- Frailty as a distinguishing factor

- Improving Frailty in multiple myeloma patients

- Treatment for transplant-ineligible patients

- Using daratumumab in combination therapies

- Updated analysis of the MAIA trial

- Durability of the MAIA trial

- What is the 3 and 4 drug combination for multiple myeloma?

- Do you think the 4-drug combination will be the new standard of care?

- Side effects from multiple myeloma treatments

- IVIG and daratumumab

- Necessity of stem cell transplant

- Transplant eligibility after multiple myeloma treatment

- Dexamethasone

- What is mass spectrometry in multiple myeloma?

- FasT CAR-T cells

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Introduction to Dr. Caitlin Costello

I am an associate clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Both my clinical and clinical research interests are almost predominantly focused on multiple myeloma. It is just my passion and my favorite patients. I’m excited to talk to you today about what’s new in myeloma.

Who is eligible for a multiple myeloma transplant?

Good question, and actually a bit of a moving target. [Transplant eligibility] is usually kind of assigned at the time of diagnosis. A patient first gets diagnosed with multiple myeloma.

The oncologists, at least historically, got just kind of a gestalt or a gut instinct to say, “This patient is younger, older, healthier, less healthy, [have] a good performance status.” [That means] they’re independent with their activities of daily living. They can bathe themselves, they live alone, [and] they do their own grocery shopping. Whatever it is.

Historically, we’d look at a patient and say, “Healthy, not healthy, old, young.” [We’d] make kind of just generic assignments to people. That’s really challenging to do when someone’s first diagnosed with myeloma, because many times when you’re first diagnosed, you’re sick.

You don’t feel good. You’ve spent months trying to figure out what’s going on. It may have taken a while to get the diagnosis at that point. Many bones have been affected by myeloma. It can be very painful. A lot of people just aren’t all the things that we think of what normal health is.

Frailty as a distinguishing factor

Traditionally, we have made assignments when patients were first diagnosed to say, “You are healthy enough, strong enough, or well enough that you can get an intensive regimen called a bone marrow transplant or not.”

I think there’s been a bit of an evolution to the concept of transplant eligibility as some more data has emerged to say, “Does everyone have to get a transplant?” Maybe we don’t need to use those same kinds of assignments to make that determination.

I would argue I think the better way to distinguish between patients who may be able to get a transplant and patients who may not is frailty. Frailty is a little bit more of an objective, as opposed to a subjective, means of evaluating someone’s health and independence.

[It can] really kind of help identify those patients who may be candidates for more intensive therapy throughout their myeloma diagnosis, we’ll say, and their treatment. That is kind of where we’ve landed on transplant eligibility and ineligibility. The concept is do we think people are well enough to undergo a bone marrow transplant?

Improving Frailty in multiple myeloma patients

What is the best treatment for frailty?

So many patients are not well when they’re first diagnosed, but really can turn around pretty quickly, where they perk up. Their bone pain is under control, [as well as] their anemia, their kidney disease, or whatever way the disease manifested.

These treatments we have are so good now that patients are responding so quickly. They get better quickly. The way that your doctor first met you when you were diagnosed is unlikely the same person that they will meet 2 months down the road after you’ve started treatment. Our job is to continually reassess your health and your general wellness to make that decision because what you were yesterday may not be what you are tomorrow.

Treatment for transplant-ineligible patients

What is the most common type of treatment transplant-ineligible patients get?

Dr. Costello: A bit of an evolution as well. What a wonderful problem that we’ve had so many new drugs developed in multiple myeloma. When drugs do get developed, first they are approved for patients who have had many prior treatments, and they’re looking for the next newest and greatest.

Our job is to continually reassess your health and your general wellness to make that decision because what you were yesterday may not be what you are tomorrow.

Dr. Costello

That’s usually how the FDA approves these drugs. They approve it and say, “Let’s just start with this group of patients.” Over the years, it gets tested with more and more patients earlier on in their diagnosis.

One of the things that patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, who are not planning or not eligible or too frail to go to transplant, have enjoyed is the addition of daratumumab to the first treatment you receive when you’re diagnosed.

Daratumumab is a bit of a magnet. It’s technically called a monoclonal antibody, but it is a medicine that predominantly is given as a shot. That medicine is injected. It is particularly looking for a sign on the myeloma cells that says, “Hey, this is me.” When it finds it, like a magnet, it sticks to it.

That helps pop it open, and it pops it open with many different approaches. It’s a real kind of targeted treatment and uses your immune system to help kill as well. I really have seen daratumumab kind of evolve into the gift that keeps on giving, because it really has helped so many patients at various time points in their disease.

Using daratumumab in combination therapies

We like to use multiple drugs. I think of it as like the old game of Clue. Instead of just using a candlestick or a revolver or a lead pipe, we want to use all the tools we have together as a cocktail so that we can approach the myeloma, sneak up on it, and kill it in different ways.

Daratumumab is great in combination with many different treatments. I’d say the frontrunner right now for patients is the combination of daratumumab with good old lenalidomide, also known as Revlimid, plus or minus dexamethasone, which is something that we’ll get into.

Updated analysis of the MAIA trial

The MAIA trial was designed for patients that we’re talking about. They got the combination of 3 medicines — that daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone — and they compared it to patients in that same group and only gave them 2 of the medicines, the lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The whole point was to understand is 3 better than 2? And if so, how can daratumumab help improve above and beyond just the 2? It was designed for patients when they were first diagnosed, not going to transplant. [They] use these treatments for as long as they are effective and as long as it’s tolerated by the patient.

It’s been a good number of years now since this trial started [and] ended, and [they] are still following these patients for many years after the fact to try and see over time not only how successful it is, but how durable it is.

The greatest thing we can do and probably the most important thing we can do is get people into remission the first go around. We like to say the first cut is the deepest. How can we have the most success when the myeloma is in its most kind of naive state, when it’s a brand-new baby? It doesn’t know any better. It’s not going to become resistant. We want to throw our best kind of weapons at it first.

Durability of the MAIA trial

The MAIA trial, over the last many years, we’ve seen updates that come out that tell us time and time again that the 3 medicines combined together are [a] extremely successful combination to get people into remission [and] keep them there.

The durability is because we are killing so much myeloma. The myeloma you can see above the surface, myeloma you can see under the surface that’s very hard to detect. We’re just killing it all.

By making the myeloma stay away, people are living longer. We’re seeing all these outcomes and results from the MAIA trial year after year, showing that the successes of these 3 medicines together is great because it works and it lasts.

What is the 3 and 4 drug combination for multiple myeloma?

If we’ve proved 3 is better than 2 medicines together, it brings up the next natural question: Is 4 better? That question is trying to answer if [they should be] adding daratumumab to another group of patients who have just been diagnosed with myeloma.

Let’s say that this is a younger, stronger, healthier group of people, who we have historically treated with 3 medicines called lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone. For the last many years, that combination of those 3 drugs has kind of been the mainstay. It’s been the most widely accepted, most successful treatment that we’ve been able to achieve ever. But we need to always do better.

The GRIPHON study was a study that looked at patients who were younger, healthier, stronger, going to go to transplant — the decision was made, you are going to get a transplant — and divided it in half and said, “I’m going to give you 3 medicines like we always do. This is the current standard of care,” or, “I’m going to give this other half 4 medicines.” So the same treatments that the first 3 got — the Revlimid, Velcade, dex — and add the daratumumab to it for a group of 4.

All the patients got the treatment that they were assigned to. All the patients subsequently had a bone marrow transplant. After the transplant, all the patients got consolidation and maintenance, which just means a little extra therapy after your transplant, followed by some amount of maintenance therapy, which is usually either fewer drugs or lower doses as a means of maintaining the successes you’ve had from all the treatments prior.

By comparing 4 drugs to 3 drugs for this group, again, dara keeps winning. We see that the daratumumab really is effective, again, at deepening response, killing more myeloma, making it get into remission more likely, [and] allowing patients to get back to themselves, to get stronger, and to continue on some amount of medicine that’s going to allow the myeloma to kind of stay in remission in very deep ways.

Again, seeing the same outcomes we saw in MAIA, that the addition of dara to our standard of care allows for great successes that last.

Do you think the 4-drug combination will be the new standard of care?

I’m already doing it. It’s hard to ignore the data when it’s that good. Granted, the reason I think why you’re asking the question is because the trial that was done was technically what’s called a phase 2 trial, where [there is] a lot of drug development and new combinations.

The people that are the most critical of statistics and evaluating successes are the ones that really want to see what we call big studies, phase 3 trials, randomized data, or you’re comparing the standard to something new and novel. Those are happening. The same drugs, the same study, more patients — it’s happening. We’ll get that information.

But on the same token, if I already have some information that shows me just how effective it is with a good number of people, I don’t want to wait. I want to kind of do good and do well by these patients with these early successes that we’re seeing now. I think it’s here.

Side effects from multiple myeloma treatments

Are there more side effects when taking 4 drugs rather than 3 for multiple myeloma?

The addition of daratumumab to any of these regimens, fortunately, is a reasonably well-tolerated medication. It is initially a little bit more inconvenient because of the frequency of the dosing.

Remember, this drug is given once a week for 8 weeks, and then it’s given every 2 weeks for another 8 times. After those first 6 months, it goes down to once a month, which is a very attractive option for patients. They can just come in once a month, get their blood drawn, get a shot, and get out of there. From a perspective on quality of life from inconvenience, I think it’s a really nice option.

Now, from side effects, though, what I would also say is that the kind of greater side effect we think about — there’s probably 2, I would say — that we’ve learned a lot in the midst of a COVID era.

Injection-related reaction

One out of 10 patients with the first injection may have what we call an injection-related reaction, where patients may, kind of like a bee sting, have a variety of reactions.

Like a bee sting, you may get a little red spot, but some other people may need to have an EpiPen. This is how I rationalize it or think about [it] a little bit. We have to, with your first dose, kind of stare at you a little bit [to] make sure that you’re not having those reactions. Again, 1 out of 10. After that first administration, the likelihood of having a reaction is somewhere about 1 to 2% thereafter, so very low. The reaction risk is small but important.

Weakened immune system

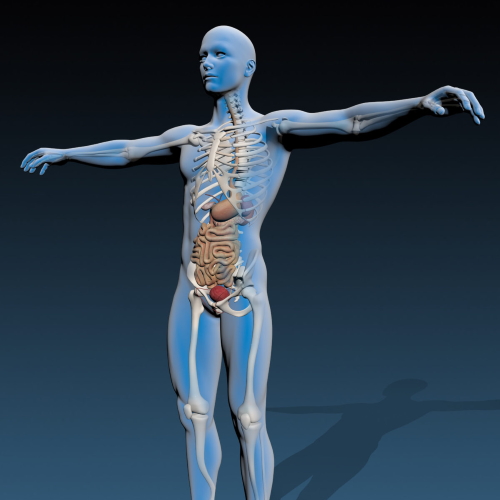

Multiple myeloma patients inherently have a weakened immune system. Their immune system is so busy making myeloma that it’s not making adequate amounts of your normal immunity.

If you take a drug that’s designed to kill the immune system problem, you’re going to take some innocent bystanders with it. The daratumumab is going to try and kill all those myeloma cells, but those myeloma cells are plasma cells. Plasma cells are designed to make the weapons you need to kill the bad guys, whatever it is — the flu, the COVID, the pneumonia, whatever.

If we are taking patients who already have a somewhat weakened immune system or [are] trying to get their immune system to build back up, there is going to be some effect on the immune system that puts patients more at risk for getting colds, COVID, pneumonia, sinus infections, whatever it is.

If you take a drug that’s designed to kill the immune system problem, you’re going to take some innocent bystanders with it.

Dr. Costello

It’s important to make sure we are prepared for that. Vaccinating against the handful of different things we know are important for vaccination for myeloma patients, whether it’s COVID or flu or pneumonia, and sometimes using preventative antibiotics when patients are first diagnosed.

I’m glad to say that unlike some of the other medications that we use with myeloma that cause neuropathy, where you have that numbness, diarrhea, or severe fatigue — things that really can affect your day-to-day lifestyle — I don’t think daratumumab affects it as much.

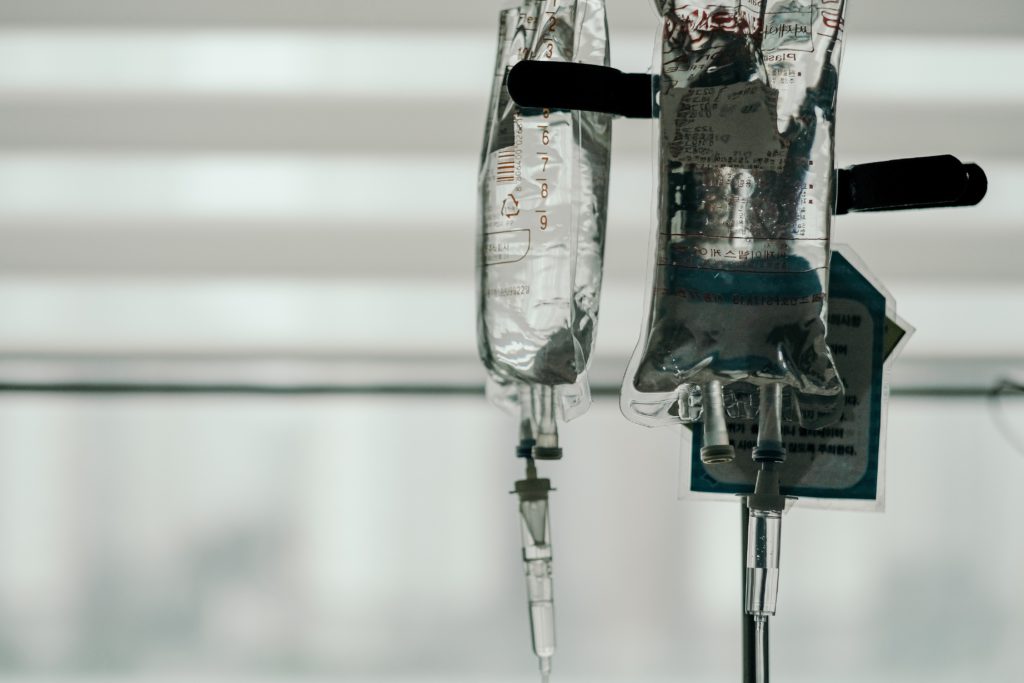

IVIG and daratumumab

I call [IVIG] a magic trick to try and build your immunity up a bit. Whether your myeloma is not making enough of an immune system or the treatments have compromised your immune system, your IgG, which is one of your weapons to kill the bad guys, can be decreased, can be accidentally killed, [or] can [be] whatever to suppress your immune system.

If your immune system is weak because your IgG levels are low, why don’t I just give you some IgG? That’s what IVIG is: intravenous immunoglobulin. If I can give you some booster to your immune system, perhaps that will prevent some of these infections from happening.

Historically, the way IVIG has been approached is to say if someone has severe, recurrent, life-threatening infections, those patients should receive IVIG. As we’re getting more and more aware of some of these infections that can happen with a variety of different medications that are out there for multiple myeloma, I know I have become much more liberal with my IVIG use because I think it could only potentially help.

There are some potential side effects of infusion reactions and things like that, but for the most part, I believe it helps more than hurts. There are always barriers to insurance and things like that, and we have to go argue.

In the very beginning of patients, if they’re doing well and their IgG levels happen to be low and they never have any infections, I don’t automatically start it. But for anyone who’s starting to kind of have these recurrent something or others, it’s certainly worth chatting with your oncologist to say, “Is there a role for IVIG here for me?”

Necessity of stem cell transplant

Are stem cell transplants still needed initially and what does DETERMINATION trial tell us?

Dr. Costello: The million-dollar question. It’s ironic because it keeps getting asked. I think everyone is so hopeful that we can get rid of autotransplant because we have all these new medicines. Every time a new medicine comes out, the question is posed. A trial is done to say, “Do we still need transplant, or is this better?”

That’s what this trial was designed to do. It took patients who were eligible for transplant, divided them in half, and gave everybody the same medicine — so our old goodie triplet combination of Revlimid, Velcade, and dex.

[Then they] said, “You get this, and you go to transplant. You get this, and you don’t go to transplant. Let’s see what happens between those two,” with the idea of looking at [if] one group [is] going to have their myeloma come back sooner than the other group.

The DETERMINATION study was kind of the U.S. version of it. The French had their own version, the same thing, and they’re always ahead of the game with us with clinical trials. They were able to complete enrollment, get the results, [and] publish it well before we did.

They showed that the patients who got [a] transplant stayed in remission longer than those who didn’t. But after looking at the data for a handful of years, what they saw was that there was no difference in how long people lived for.

[There are] lots of arguments about whether that is important — and one would argue yes — [and] whether enough time had passed by to say, “Here we are. We keep applauding and patting ourselves on the back for how well these treatments are working. Maybe we haven’t had the full time pass by, enough to say that there’s going to be a great difference in survival or not.”

When the Americans did theirs, the only subtle minor difference was that after transplant, patients stayed on Revlimid maintenance indefinitely, as long as the maintenance was working.

If they did not go to transplant, they stayed on Revlimid as long as it was working, which was different from the French. They only took it for 12 months and then stopped.

There were a good number of people who stopped therapy and often never had progression for 6, 7 years, whatever it is. What the American side of the trial showed was similar. The transplant group stayed in remission longer.

The survival was no different, but there did seem to be improved time to staying in remission because, we think, of the longer-lasting use of the maintenance Revlimid.

I think it begs the question, is it that we need to get rid of transplant, or is it that transplant is complementary? They have parsed through that data left, right, and up and down to try and understand was it the blondes who did better, was it the African Americans who did better, or [did] someone who had different kidney function do better?

[They] tried really to see, is it a general statement we can make across the board? I think the thing that was the most helpful for me to try and parse through whether or not transplant was important or still has a role… While I would love to know that it saves lives, let me hearken back to my “the first cut is the deepest” comment.

Is it that we need to get rid of transplant, or is it that transplant is complementary?

Dr. Costello

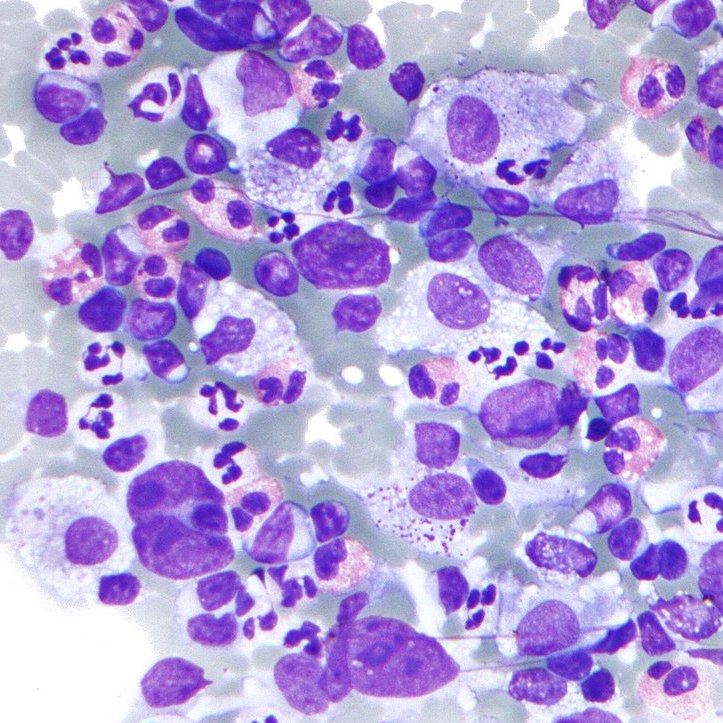

If we are really trying to make a deep impact in myeloma when it’s first diagnosed with the presumption that that’s going to allow for the longest periods of remission until the next newest and greatest comes out, then it’s pretty clear the way they parse the data to say that those who had transplant are more likely to get to what we call MRD negativity, minimal residual disease, which is that [myeloma] way under the surface.

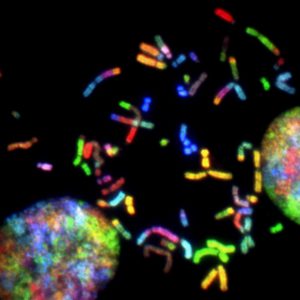

We have lots of tricks to count myeloma. I can do a bone marrow biopsy instead of my pathologists, and they look under the microscope and say, “Yep, I see it. Nope, I don’t.” But in 2023, shouldn’t we have super high-tech technology that can look for myeloma in the smallest little micron of DNA?

MRD is a way that we can look for myeloma hidden in the smallest depths of your bone marrow, because what we know is if there is 1 little bad guy kind of hiding under the surface, that 1 little bad guy is only a matter of time before it doubles. Then that [2] doubles into 4, and 4 turns into 8, and 8 turns into 16.

We want to try and get rid of every last bit of myeloma because those patients, we can tell time and time again now, are the ones who are staying in remission the longest.

The DETERMINATION study was helpful for me to say we’re not saving lives. We’re not letting people, as far as we know, live longer because of doing a transplant, but we are having patients stay in remission by doing it.

Maybe we need more time to pass by, maybe we don’t. I think for the meantime, transplant really seems to me — disclaimer, I’m a transplant-er — that it’s complementary. I think it works with our novel agents, not better or worse than our novel agents.

We’ll see with MRD negativity, if that’s our end-all be-all goal, if someone happens to get there with treatment without a transplant by itself, maybe they don’t need a transplant. Maybe that’s what we should be looking at instead of saying it’s, across the board, necessary for everybody.

Maybe we can try and figure out if our initial treatments didn’t do the job, maybe that’s the group of people who should proceed. So stay tuned. Lots to come.

Transplant eligibility after multiple myeloma treatment

Why don’t we check after a few months of treatment to get a sense of, whether is there a lot left over? You probably need a transplant. You need that extra oomph. But if it’s all gone, then maybe we don’t need it.

The transplant is obviously not an insignificant treatment. We have quality-of-life data that says that that’s a hard 3 months after a transplant in terms of recovery. After those 3 months, the majority of people are back, but it’s 3 months of putting your life and your job and your family and kind of throwing everything upside down. It’s important to weigh that with the benefits of doing a transplant, which for now I think is still worth it.

Dexamethasone

Why is dexamethasone used in multiple myeloma?

Dexamethasone is clearly the drug that everyone loves to hate. I think it’s important to say that dexamethasone is an oldie but a goodie. It’s been around for a long time. It is not a chemo, but it is designed inherently to kill myeloma.

I think that’s an important part because patients oftentimes ask, “Well, can I just stop it?” I want to say, “Yes, but remember, consider this part of your treatment regimen also.”

But it is hard. I’ve heard people say, “It’s a dex day,” and I look at the spouse or the caregiver and say, “How’s it going?” Because that sometimes can affect your quality of life more than any of the other treatments do. People plan out their lives around the days they’re taking dex or the days after their dex.

It behooves us to really understand the importance of dex for all of these regimens, because if it is playing a huge role in killing myeloma, then sometimes it’s worth it.

If we are using it for an initial period of time to make a dent in the myeloma, for example, if we can get people off the dexamethasone and kind of continue the rest of the treatment, sometimes that makes it much more manageable for everyone across the board, let alone older, frailer patients.

At ASH, we heard about a trial [that] was one of the first, if not the first, randomized trial that was done for specifically frail myeloma patients. Remember, we’ve talked about objective means of evaluating what frailty means. This is literally calculators, which plug in different characteristics about your health and your independence to say that you are fit, frail, or somewhere in between.

This trial took frailer patients, divided them in half, and said, “You’re going to get Revlimid and dexamethasone on the one half. The other half, we’re going to do Revlimid, but instead of the dexamethasone, we’re going to do daratumumab.”

It’s similar to the MAIA study we’ve talked about when combining dara and Rev, but this time with the hope of using as little dexamethasone as possible to see if these 2 groups, both receiving 2 medicines, can have good outcomes still without using the steroid in the study arm.

Now, I’ll say that these patients did get dexamethasone for the first 2 cycles, I think it was. That’s important. I think dex plays a role in helping to mitigate reactions to the daratumumab. Beyond that, maybe we can get rid of it.

They compared these 2 groups and said, “Dara-Rev, Rev-dex, how does it go?” Again, the dara-Rev group won. It is possible, we’ve learned, to get rid of the dex on our older, frailer patients.

[It]probably is going to be practice changing to say if we can drop the dex as soon as possible, patients may not have the same side effects: emotional lability, water retention, feeling swollen, appetite, not sleeping at night.

If it’s not going to play a huge role, it’s in the best interest of everyone to get rid of it. This was the first time we’ve seen not only for a frail group, but how we can successfully get rid of dex.

What is mass spectrometry in multiple myeloma?

The MRD that we’ve mentioned here is a way of measuring how much disease is hidden under the surface. We can look above the surface. The old iceberg analogy is a way to see it, if you have an iceberg sticking up above the ocean.

You can calculate the amount of myeloma that’s there in the bloodstream by doing blood tests, figuring out what the M-spike is or what your free light chain levels are. Remember, we still have had to historically go to the bone marrow and do those very pleasant bone marrow biopsies to understand what is not in the bloodstream, but maybe hiding in the bone marrow.

What’s in the bloodstream comes from the bone marrow. If we can look at the bone marrow and figure out what kind of high technology we can do in order to look under the surface right now are our best options for evaluating this for the minimal residual disease or 1 or 2 little bad guys that are stubbornly hanging around.

Right now, we have to do bone marrow biopsies to do that. I couldn’t count on any number of hands how many patients say, “Really, we have to do another biopsy?” I get it. Mass spec is a way that maybe we can start using that high technology to use the bloodstream test.

It’s a way that it can identify certain proteins or certain specific changes in the protein, the DNA, or whatever it is in order to say we’re picking up that small little micron of evidence of myeloma in the bloodstream. It is here. It’s already here, kind of in an investigational form.

It’s a really nice way for us to distinguish between an IgG kappa multiple myeloma and an IgG kappa daratumumab, and we’re not sure which is which. With the protein analysis that it does, it may be able to pick up the smallest amount of myeloma hidden in the bloodstream so that maybe we can identify very low levels of myeloma in the bloodstream without doing those bone marrow biopsies.

I think we’re going to see this come to practice in the next couple of years, because everyone desperately wants it. As long as it proves to be just as good as the bone marrow biopsy, it’ll be here to stay.

Cindy, TPS: Is this something that could be done to my local oncologist office, or is this something that I might have to send my blood out to a center of excellence to read it out?

Dr. Costello: Right now, we have to send it out. There are very few labs that are doing this or able to perform it. I’ve heard rumors of it potentially being looked at by the FDA sooner than later. If the FDA is able to kind of approve a device or a mechanism of performing that, we may see it have wider availability, but for the meantime, it would have to be sent out. I would say your oncologist likely doesn’t have it.

FasT CAR-T cells

Right now, there’s 2 different CAR T-cells that are approved by the FDA for the use of refractory myeloma for patients who’ve had more than 4 prior lines of therapy. Again, these are patients who had myeloma a long time. They’ve had lots of treatments.

Right now, it’s not available in the U.S. for patients who are just diagnosed. The Chinese designed a CAR T-cell and have started doing clinical trials, evaluating it for someone who’s just diagnosed with multiple myeloma.

In the U.S., the CAR T-cells that we have take 5, 6, [or] sometimes longer weeks to manufacture. [The Chinese study] figured out how to manufacture it in 1 to 2 days. Their initial results they presented at ASH showed that it worked for 100% of the people they treated, and 100% of those patients were MRD negative, meaning that they cleared out every last myeloma cell.

I think one of the things that we are very excited about is CAR T in general, but how can we use it earlier in the disease course? This is one of the first trials we’ve seen where somebody is trying exactly that with what seems like good success. Disclaimer: it’s a very small group of people. To be determined, but exciting.

More Multiple Myeloma Medical Experts

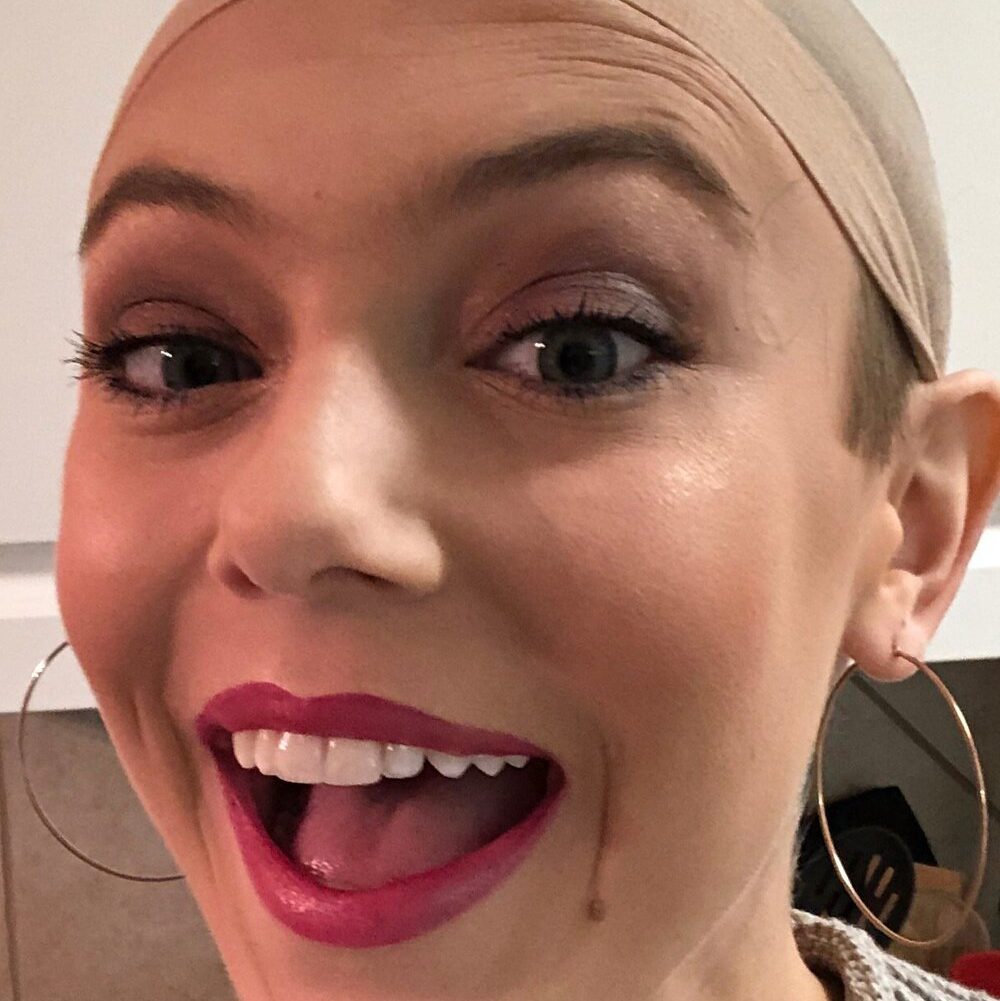

Research on Black Myeloma Patients, Access & Disparities

Patient advocate Valarie Traynham and Dr. Shakira Grant discuss the barriers many Black patients face, how it impacts their care, and what can be done to help improve their outcomes.

Dr. Brandon Blue

Dr. Brandon Blue shares key strategies for better health care and saving lives, especially in communities impacted by multiple myeloma.

Irene Ghobrial, MD

Role: Clinical investigator and professor of hematological oncology

Focus: Multiple myeloma, Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia, early screening, clinical trials

Provider:Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston)

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

Joseph Mikhael, MD

Role: Dir. Myeloma Research, CMO at International Myeloma Foundation (IMF)

Focus: Multiple myeloma

Provider: TGen/City of Hope