Ray Explores Earth’s Limits and His Own with Waldenström Macroglobulinemia

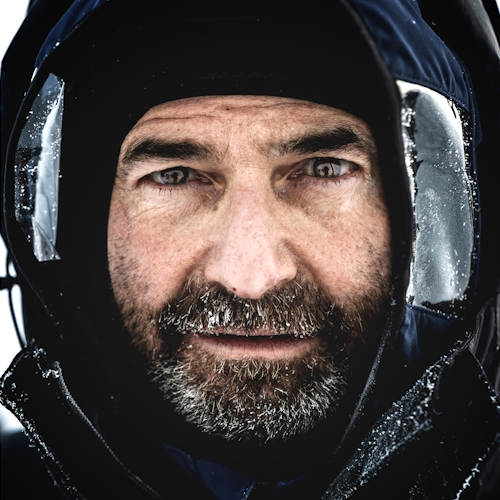

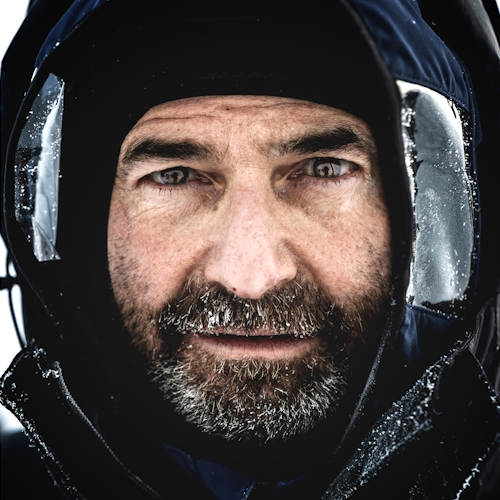

Ray describes himself as a professional explorer, but clearly, he’s much more than that. He’s a teacher, an advocate, and someone who sees life with rare clarity. In 2023, Ray was diagnosed with Waldenström macroglobulinemia, a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

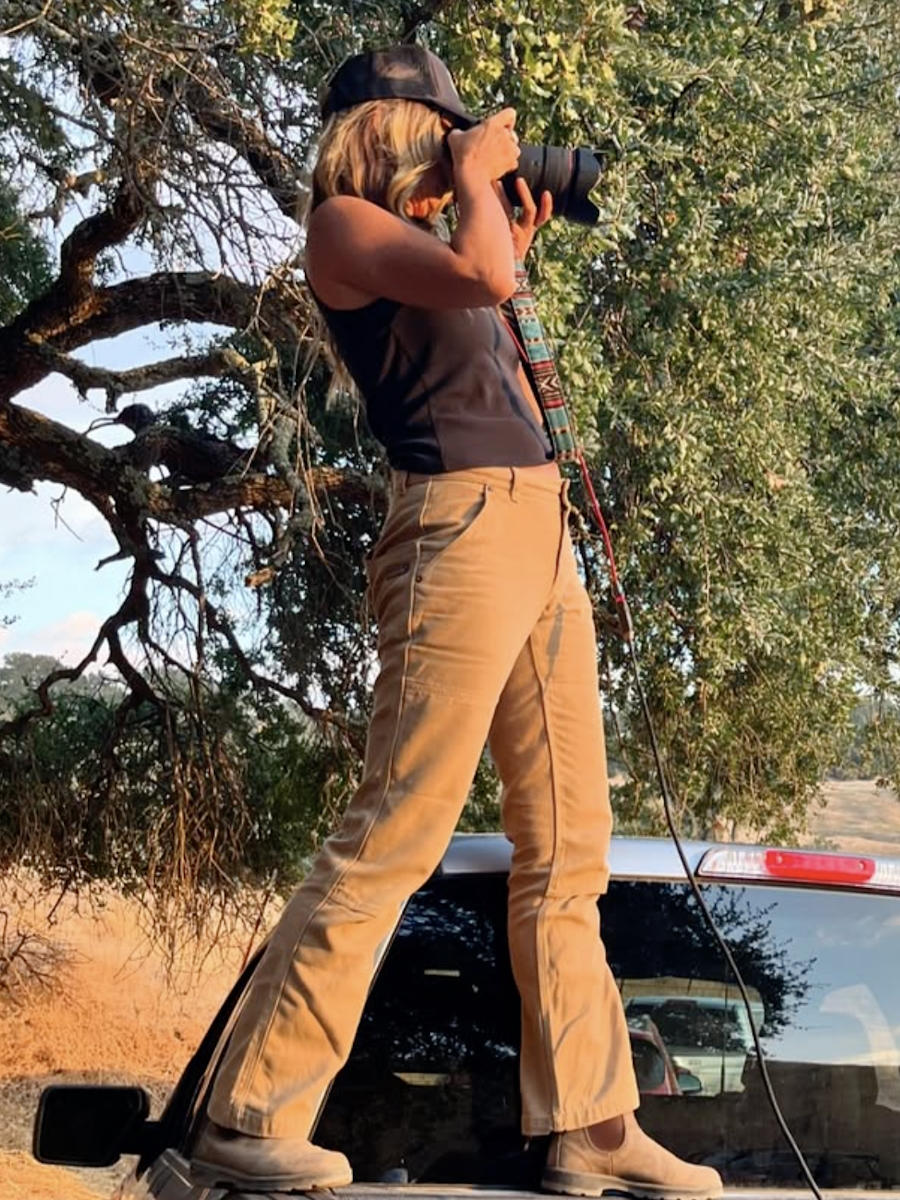

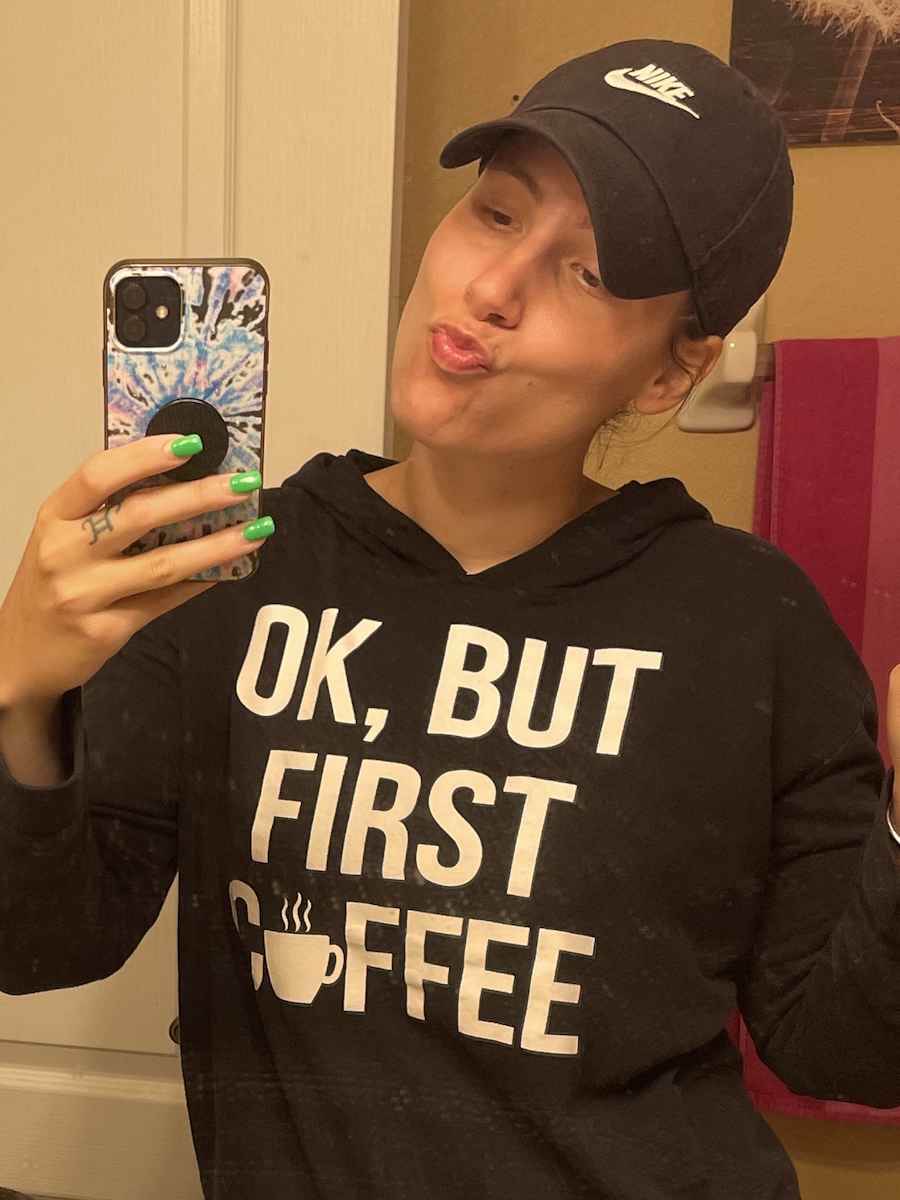

Interviewed by: Taylor Scheib

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

For someone who had crossed the Sahara Desert on foot, trekked unsupported to the South Pole, and endured countless extreme expeditions, noticing something was wrong with his body wasn’t easy. But when constant fatigue, dizziness, memory lapses, and the feeling of having “wool in his head” started affecting his daily life, he knew it wasn’t just because he was getting older.

After rounds of bloodwork and a bone marrow biopsy, doctors confirmed the diagnosis. Ray admits he first thought he had six months to live. Instead, he learned that while Waldenström macroglobulinemia isn’t curable, it’s treatable. His medical team immediately started chemotherapy, followed by monoclonal antibody therapy, though his allergic reaction to the latter made the process far from smooth. (Editor’s Note: A monoclonal antibody is a type of protein made in the laboratory that can bind to certain targets, such as antigens on the surface of cancer cells. Each monoclonal antibody is made so that it binds to only one antigen.)

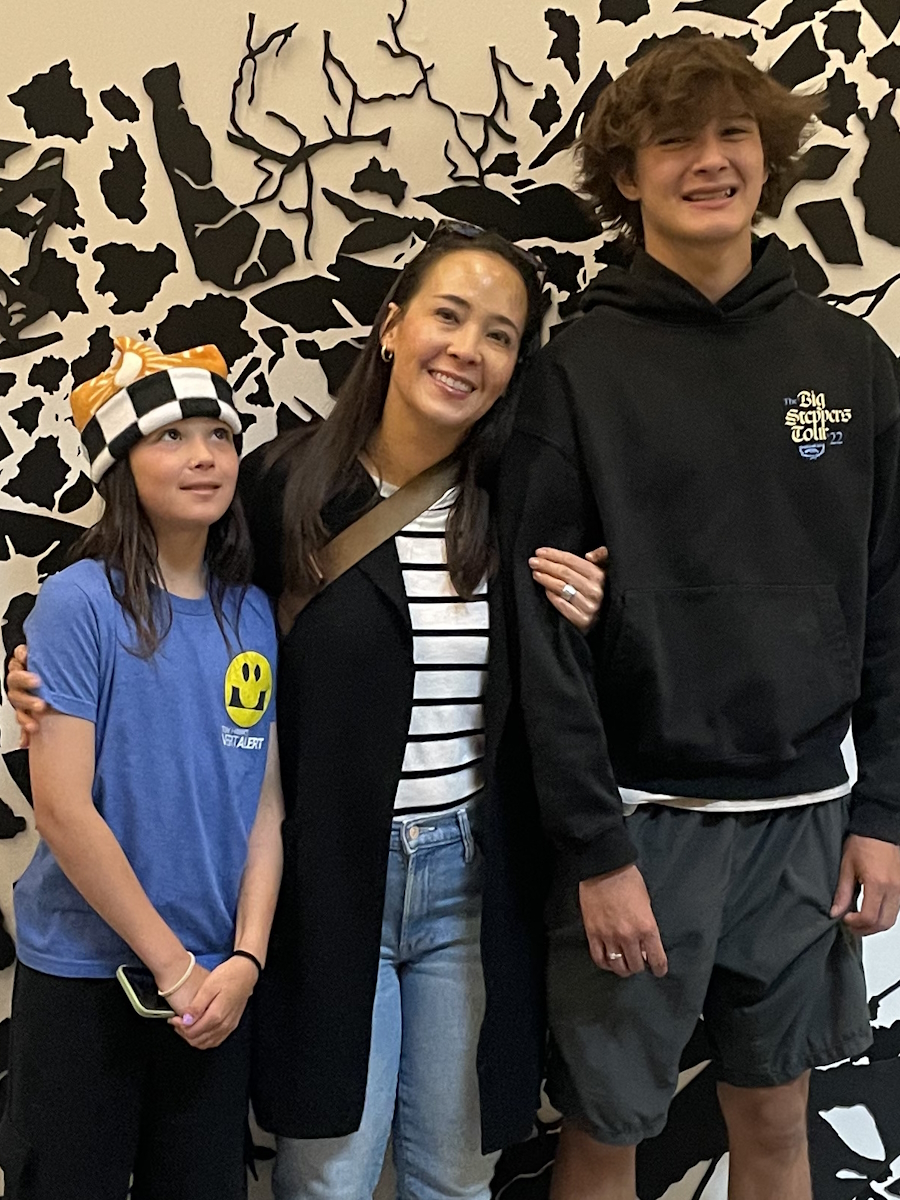

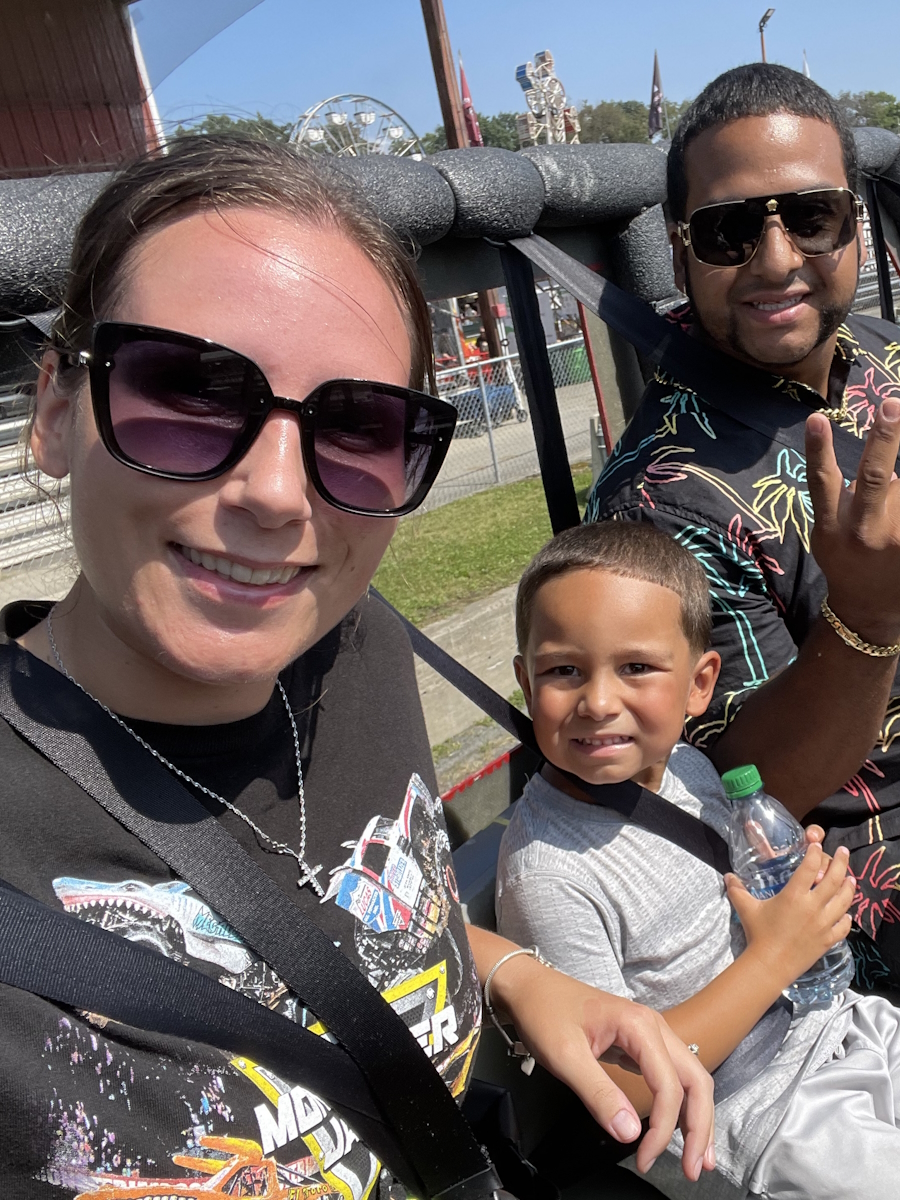

Ray approached treatment like he approached his expeditions: with grit, discipline, and a refusal to let circumstances define him. Throughout treatment, he kept moving. Some days that meant training for another Arctic trek, other days it was walking down the road after days of being sick from infusions. He found comfort in normal family life, his wife’s encouragement, and the humor of friends who treated him like himself, not just “the guy with cancer.” For Ray, empowerment came from living fully, not waiting for life to “resume.”

What’s powerful about Ray’s story is how he reframes illness. He doesn’t call himself a “cancer survivor.” Instead, he insists he is a person who defined his own experience, someone who took back his life. Waldenström macroglobulinemia may have disrupted his path, but it also sharpened his perspective: savor the perfect espresso, enjoy the messiness of family life, laugh with friends, and say yes to adventures — whether that’s crossing Death Valley in record heat or showing up at his daughter’s ski race after chemo.

Ray wants others with Waldenström macroglobulinemia or any rare diagnosis to know that you can’t always control what comes your way, but you can choose how to live through it. And sometimes, that choice is the most empowering act of all.

Watch Ray’s video or read the transcript of his interview to find out more about:

- How a world explorer went from the Sahara Desert to a rare lymphoma diagnosis

- Why Waldenström macroglobulinemia didn’t stop Ray from chasing new adventures

- The surprising lesson Ray learned from sitting in a chemo chair

- How humor, family, and fitness helped Ray reclaim his life

- What espresso taught Ray about appreciating the present moment

- Name: Ray Z.

- Diagnosis:

- Waldenström Macroglobulinemia (WM)

- Symptoms:

- Constant fatigue

- Excessive napping

- Dizziness

- Memory issues

- Shortness of breath

- Anemia

- Frequent infections

- Skin rashes

- Digestive problems

- Numb and white fingers

- “Wool in head” sensation

- Treatments:

- Chemotherapy

- Monoclonal antibody

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

My name is Ray. I’m a professional explorer. I was diagnosed with a rare form of lymphoma [Waldenström macroglobulinemia] in 2023.

My family and friends were being kind, they’d say I’m full of energy, live for the moment, love to explore, and love to laugh. If I caught them in a bad moment, they would say I’m a little bit risky and take too many chances.

I have come from a prior life. I was nearing the age of 30 and was someone who had no passion in life or no drive. I had nothing to sink their teeth into on a day-to-day basis, which compelled me to want to get out there and do things instead of living a sedentary life, if you will. I wanted a different life and I found that life through my younger brother, who is my greatest inspiration.

He was a great outdoorsman and got me into trying out rock climbing, ice climbing, and mountain biking. I quit smoking and did a 180-degree turn and changed my life. I discovered a person who was within me who I never knew existed for 30 years, someone who could do these crazy feats of endurance, like run 4,500 miles across the Sahara desert or trek unsupported to the South Pole, dragging all of my supplies behind me in a giant sled.

Here I am, 45 expeditions later and I still love what I do. If anything, I’ve learned that we spend a lot of time talking ourselves out of trying new things and out of taking chances and then one day, time runs out and we say to ourselves, “What if I took that chance? What if I went after something in my life? Who knows what would have become?” That’s why I love adventure.

I crossed the hottest deserts on the planet on foot, typically during the hottest times of the year, and I’ve completed multiple winter Arctic expeditions at the coldest time of the year, so I’m in extremes and it requires a tremendous amount of fitness, training, and resilience to do these things. A few years before my diagnosis, I started feeling exhausted all the time. It got to a point where, for someone who’s very in tune with their body, I said to myself, “I’m not the same person. Something’s changed.”

My wife noticed, too. I was napping up to five times a day. Everybody loves a good afternoon nap, but I was napping constantly. I wake up at 9 o’clock, drink my coffee, and then I have to go back and take a nap. It was so strange.

I was trying to explain it to my doctor. I feel like I have wool in my head. Maybe it’s long COVID. I didn’t know what it was. My wife said, “You have to go back to the doctor and do a series of blood tests.”

Eventually, after finally meeting with a hematologist, they discovered that I had all this protein in my blood. My blood was like molasses, which explained all of the weird symptoms that I was experiencing. I couldn’t run to the end of my lane way without being completely winded, when I was used to running thousands of miles on expeditions in extreme conditions, so obviously there was something wrong. They did a bone marrow biopsy and then got a diagnosis.

There was never a grand plan. Quitting a pack-a-day smoking habit was one of the toughest things I have ever done. It took me three years because I was into a different lifestyle. I started racing mountain bikes and I was getting fitter. Running was becoming my greatest teacher. I was going around the world doing ultramarathons, meeting new people, and going to exotic places that I’d never been before.

Through running ultramarathons, I met two friends and we had the idea of running across the entire Sahara Desert from one end to the other. Through six degrees of separation and serendipity is what I’ve always said when I give these presentations. Matt Damon heard about it and wanted to make a movie out of it. A movie gets made out of the three of us running across the Sahara desert called “Running the Sahara,” which was directed by an Academy Award-winning director, with Pearl Jam and U2 contributing music to the film. It was crazy.

Through the expedition of running 4,400 miles, I learned a few key things. The world is an incredible place and we have a lot to learn from people who are living lives very differently from us. While on this adventure through the six countries across the Sahara desert, we met people and learned from people who are living in a global economy at a completely different end of the spectrum than where we are at and yet, there was so much to teach us.

Through adventure, I’m learning what I barely got out of high school. Now I have a voracious appetite for wanting to learn and it’s coming through an adventure. Do we finish the run across the Sahara Desert? We get to the Red Sea, 111 days, running 40 miles a day, every day. The three of us have our hands above the Red Sea and I look at my hand. I glance at our three hands and think to myself, “Wow, my hand looks the same as the other two guys. I’m the same as these two champion ultramarathon runners.”

At that moment, another important point dawned on me: all of us are capable of doing extraordinary things in our lives if we’re willing to go after them. When we put our hands in the Red Sea, I was instantly committed. This is my life now. This is what I want to do for the rest of my life. I want to see the parts of the world that are the furthest, remotest places that I can learn from, but also be in those places when they’re at their most extreme. I want to be in the Arctic in the winter and I want to be in the desert in the summer, and that’s how it all began.

I learned the power of storytelling from the film. The film was quite popular at the time. People were digging it and learning from it, so that precipitated me starting my own foundation called Impossible to Possible with my business partner Bob Cox and my wife Kathy. Since 2008, we have been taking young people on free, learning-based expeditions all over the world.

When I quit smoking, I’ll never forget being able to run up a set of stairs and not being winded. Climbing stairs used to be hard, but you forget because you’re living in the moment. You have a short-term memory when it comes to how you feel. I’m 56. I’m getting older. I had COVID a few times and I thought that’s what it was. You start to accept the situation that you’re in.

It was when other things started happening, like driving somewhere and forgetting where I was. That’s not right. I was anemic and the lack of oxygen getting to my brain was causing these weird symptoms where I knew there was something seriously wrong.

By the time I got my diagnosis, I was fully prepared. I was sure that I was going to die in six months. I’ve always been very in tune with my body. I can tell you my heart rate without looking at a heart rate monitor. It’s what I do as an endurance athlete. When I went to the doctor, the hematologist said, “Your blood protein is high. This is weird.” I thought to myself, “Oh my gosh, I have cancer.” I just knew.

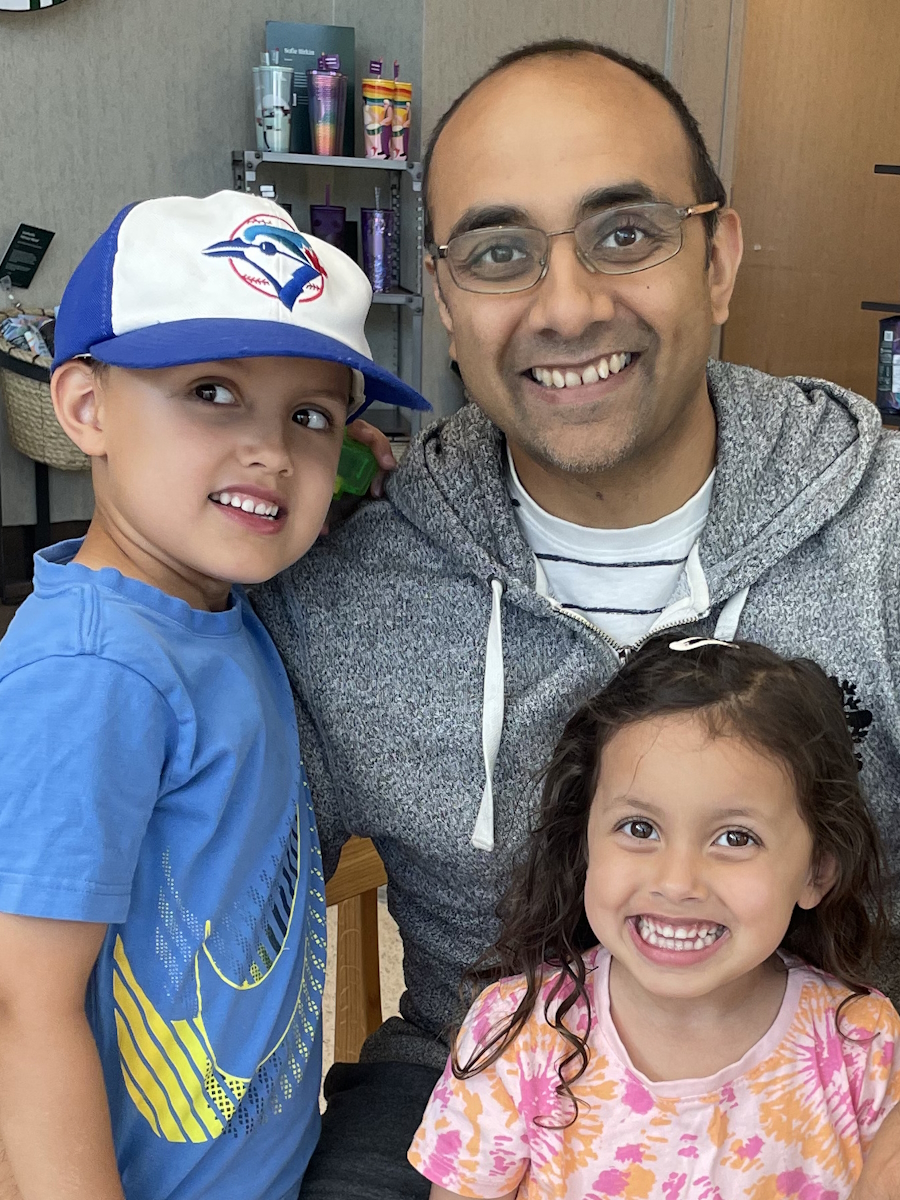

When I went home, I talked to my wife and said, “They’re going to confirm what it is. They have to do a bone marrow biopsy. But, you know what, babe, I seriously think this is it. If it is, we have to tell our kids. We’ll wait until we have a final diagnosis.” But mentally, in some strange way, I was prepared.

I wasn’t excited about it, but I was prepared that if I had six months left, it was going to be an incredible six months. I was going to do so many things with my kids, whether they liked it or not. They were going all over the world with the old man and I was going to live life at 1,000%.

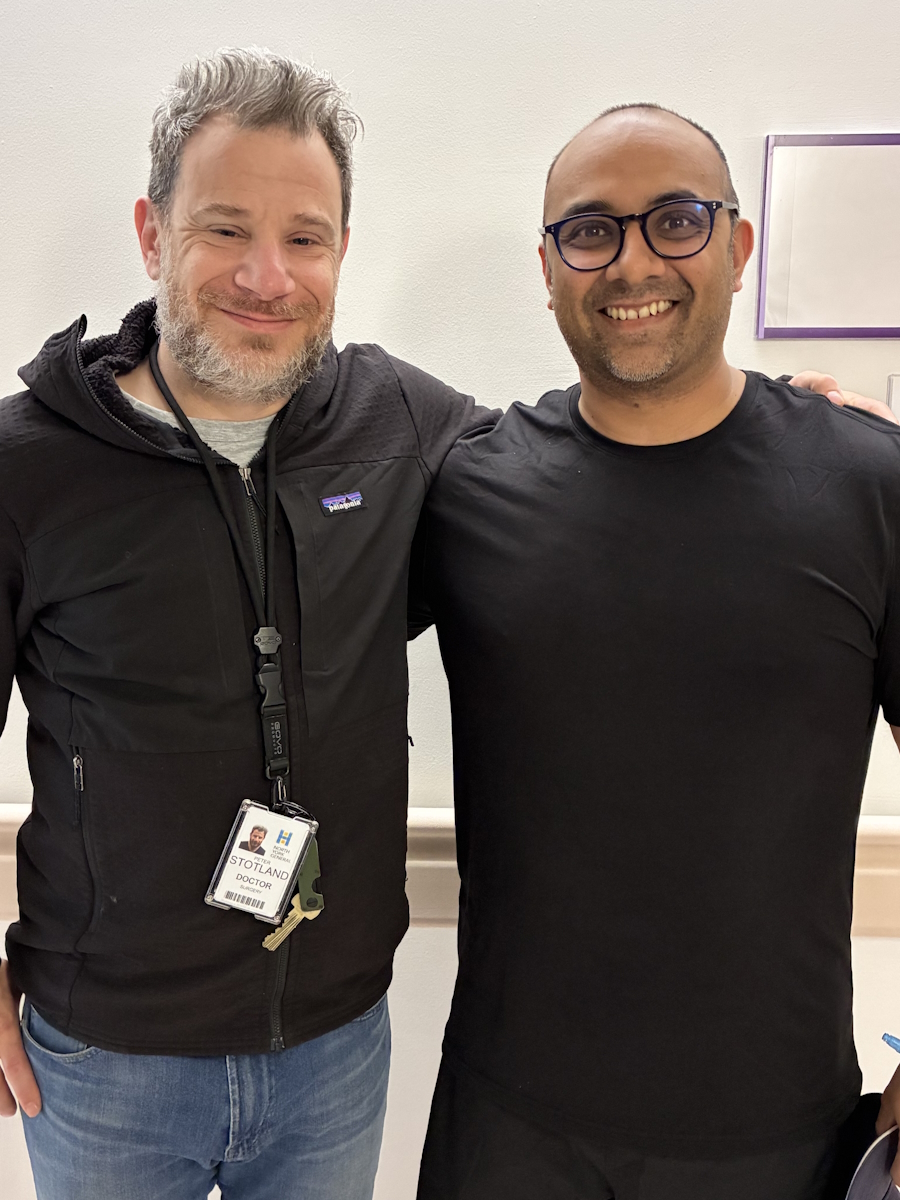

When I got the diagnosis, they said, “Do you want the good news or the bad news first?” I said, “Give me the good news.” They said, “Well, you’re not going to die.” I said, “That’s great. That’s a good start. That’s a good opener. What do you have next?” And they said, “The form of lymphoma you have, we’re going to treat it aggressively with chemotherapy and monoclonal therapy. It’s going to be six months of therapy, 25 days between the sessions. There’s no cure for what you got, but we think we can get you back to normal.” I thought I won the lottery.

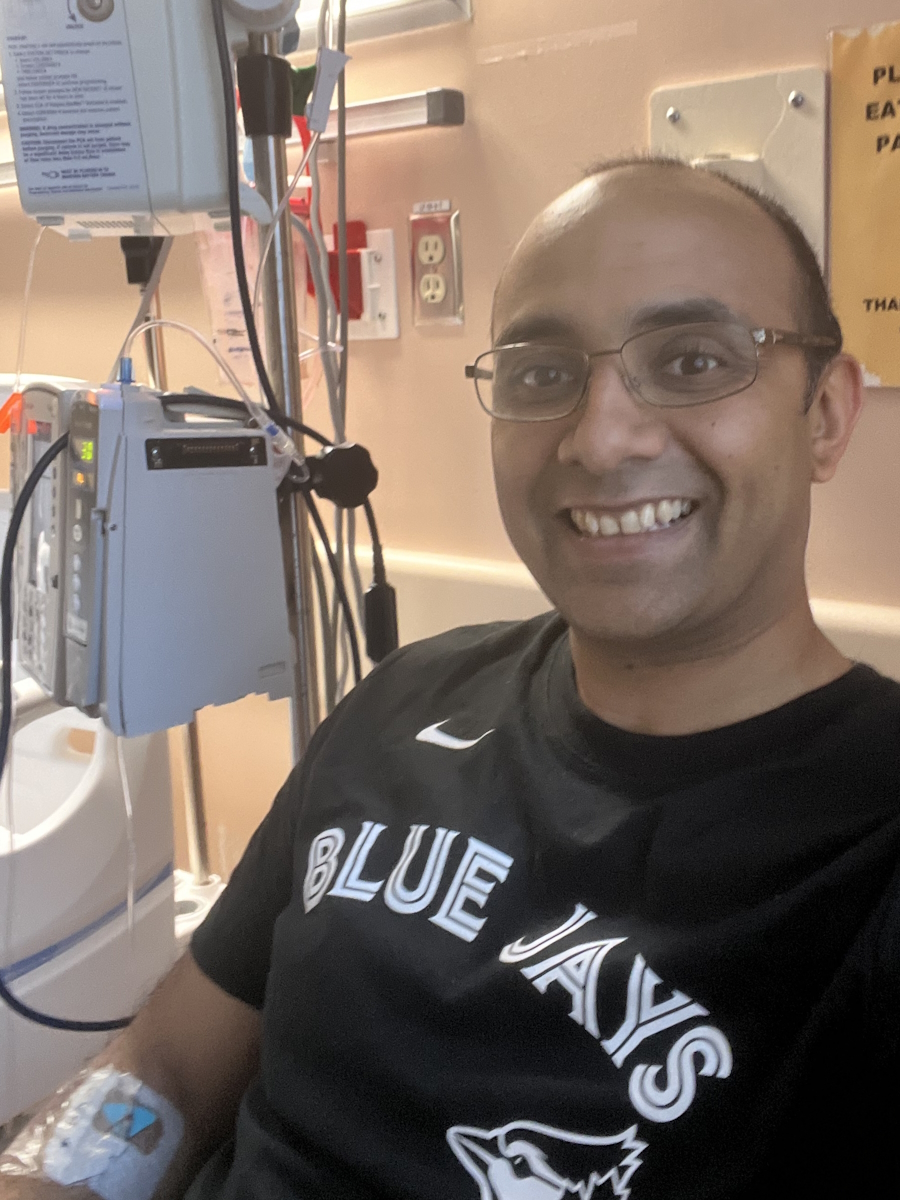

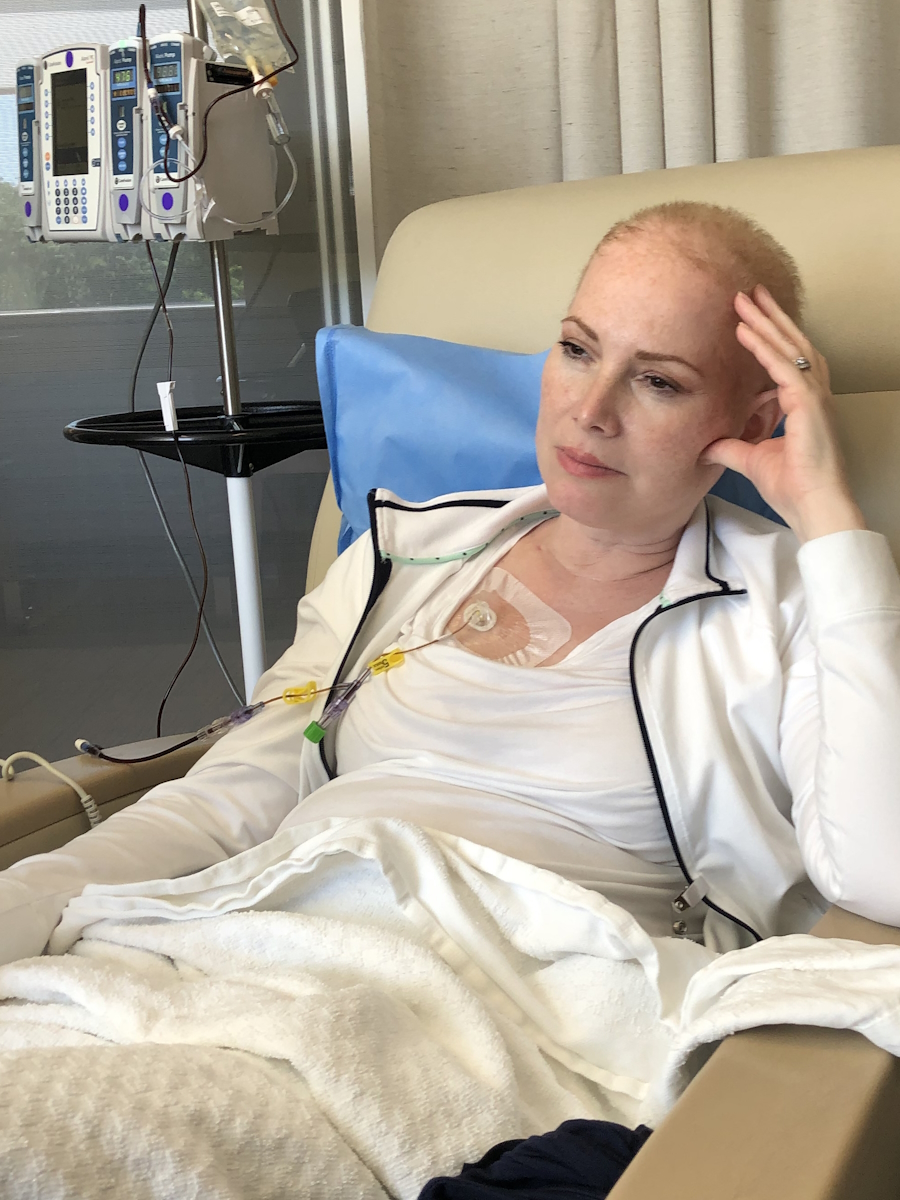

It wasn’t until I went to the first rounds of chemotherapy that I found out that I had so many residual dead cancer cells, this protein circulating in my blood, that they couldn’t give me the monoclonal therapy right off the bat. The flood of dead cells that would enter my body could cause a catastrophic failure.

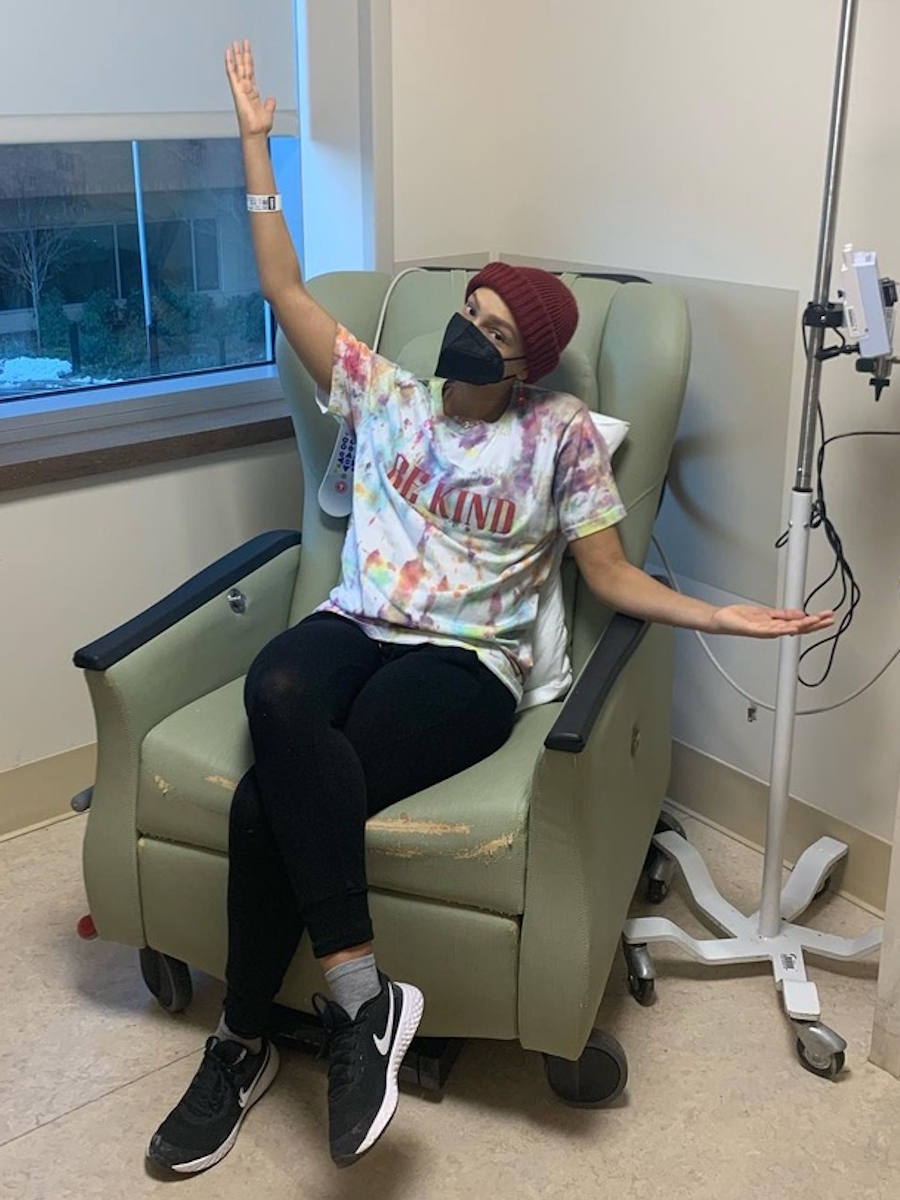

They said, “First, we’re going to start with the chemotherapy and then we’re going to the monoclonal antibody.” I had chemotherapy and thought it wasn’t so bad because I didn’t feel so much. They said, “Wait until you get the other stuff.”

On the first day of the second month, I was on the chemotherapy drip for eight hours. I came in the next day for the monoclonal antibody and my throat closed instantly. I was allergic. They worked it out and I had to have other medicines to counteract the effects. Every time I would go back in 25 days, I’d say, “Maybe you don’t need to give me the other therapy,” they’d say, “No, you’re getting every drop.”

I made a commitment when I went in and felt like s***. When I’d come home, I would lie down on the couch. I couldn’t even pee in a toilet other people use because if any random pee droplets were around, they could get sick from the drugs. I would lie down on the couch for a couple of days and my wife would say, “Okay, that’s enough. Get up.” That meant the clock was 23 days until the next round.

I made a choice. I was used to being on expeditions and choosing to do very difficult things. People ask me all the time, “What do you do when it gets tough out there?” I crossed Ellesmere Island in the Arctic with my teammate Kevin. It’s as far north on this planet as you can get. It’s an island with horribly difficult conditions. What do I think about when I’m out there? I think to myself, “I chose to be here and I chose to do this, so I’m going to give this everything I’ve got.”

I didn’t choose cancer. It chose me. But I wasn’t going to allow it to define me, nor was I going to allow it to tell me what I could and couldn’t do. My oncologist is one of the most awesome dudes on the planet. He’s a mountain biker, so he understands what I do. He said, “There’s nothing wrong with you, okay? Your immune system was collapsed, obviously. Do what you need to do.”

Every month, I would get off the couch and go for a walk. I would start with half a mile down my road and get going. Then I would train for something, whether it was an adventure in the Arctic or going off with one of my daughters into a desert. Every month, I train myself to get as fit as I possibly can, because I know how s***** I was going to feel after the monoclonal therapy. I said, “I’m going in the best fighting shape. I would go somewhere in the world, do something epic, then come back home, and go back on to the tubes.”

I would go home, lie down on the couch for two days, be sick as a dog, get up, start training, and go somewhere in the world. For six months, I chose to live and not let cancer own me. I was going to own my schedule and embrace the irony. Two days before this interview, I was up in the Arctic and now I’m sitting in a room.

When I would get chemotherapy, I would sit in a room where 65 people were sitting in the waiting room, most of whom were a lot older than me and may not be in great physical condition and not as fortunate to be on their feet. One day, a 20-something-year-old girl came in. When she walked past me, I saw that she was bald and emaciated. I thought to myself, “Dude, you have nothing to complain about. This is a cocktail party in comparison to what she’s going through

I was very aware that the difficult things we go through in life are relative to us as individuals. We can’t compare ourselves to someone else necessarily because we are living what we’re living. We’re feeling what we’re feeling. But I would not lie down on the couch feeling like s***. I thought, “It’s going to pass. It will go away. It is what it is.” That goes for all the people in the poorest countries on the planet that I’ve been in who don’t have food. There are a lot of people suffering much worse fates than what I had been given, so I’m going to live another day. A couple of days of feeling like s*** is nothing.

Sense of humor is super critical in life. We love to laugh. My best friend Bob, whom I started Impossible to Possible with, and I have this joke between us. I talk to him five times a day, so I have a room filled with gear that I use for all my expeditions. There’s a lot of cool stuff in there and tools of the trade. The day I got my cancer diagnosis, I texted Bob and said, “Hey, man, listen. Bad news. I got this crazy form of lymphoma.” He only texted back one word and said, “Dibs,” meaning he had dibs on all my stuff. It was funny.

Support comes in that way. It doesn’t necessarily have to be in the ways that one would anticipate that they would normally be. But for me, I didn’t want to be treated like someone who had something wrong with them. When my daughters had cross-country ski races, I would show up. When my daughters had paddling races, I would show up. When my wife had running races, I’d show up.

Sometimes I would show up a day after chemotherapy and feel like I was going to vomit. If I tried to pick up something, I would feel nauseous in my fingertips. I’d be standing there, thinking, “I know I’m not going to throw up, but every pore in my body feels like it.” It was the weirdest I’ve ever felt in my life. People around you who make you feel normal, even though you’re going through something crazy, are the most important to me.

In my household, life is normal. I’m lying down on the couch and my wife and the kids are screaming and fighting about something. It’s not like they have to be quiet because daddy’s passed out on the couch and I preferred that to anything else.

If you overcome it, it’s both the worst thing and the best thing that could happen in your life because right away, you start to appreciate the more subtle things in your day-to-day that before, you wouldn’t have even looked at before. I’m a big coffee person, made a great cup of coffee like an espresso, and it was perfect. It tastes so good. Pre-cancer, I would have been like, “All right, let’s go, I have to go. I’m busy.” I wouldn’t even pay attention. But now, I stop every day.

I say to my friends that I could be walking to the grocery store and get hit by a truck. You have to slow down to a point where you can be present in the moment, appreciate what you have, and be satisfied with where your life is at the moment. Find some satisfaction. Be able to appreciate where you’re at in your life in that moment. Even though you may have lofty goals, it’s not discounting those, but people have to be able to appreciate where they are in the moment because it can all be gone very quickly.

I was definitely like this before the diagnosis, but the cancer and going through chemotherapy in six months and then another year after that to get back to normal, all of that helped bring clarity. Before, it was like looking through a camera with a dirty filter and then you take the filter off and it’s completely clear. Now I completely understand and I’m very comfortable.

If they came to me and asked if they could check my blood every two months and my immune system’s not 100%, I wear a mask on a plane and use hand sanitizer all the time. I don’t care. People ask, “Isn’t that a pain in the a**?” No, are you kidding me? It’s nothing. It’s a minor inconvenience in my life that I don’t even notice.

If the doctor came back to me again today and said, “I have bad news. It’s come back again,” it would be an inconvenience, but that’s pretty much it. It’s taught me to truly appreciate where things are now. If I was to step off the planet tomorrow, would I be okay? Would I be happy with the day that I’ve just lived? You have to find that happiness in that day that you’re in.

During my third or fourth month of chemotherapy, my doctor said, “Look, dude. You can go and do these things. You’re ready to go, but here are the rules you have to follow. You know that your immune system’s collapsed, so don’t do this, don’t do that. Don’t eat raw food. Wear a mask and use hand sanitizer.”

I’m way up high in the Arctic with my buddies, the indigenous people from that region, and a couple of buddies of mine from home, and we’re weathering a snowstorm. It’s -50 degrees out. It’s in the middle of the night and we’re in this tiny little cabin on the side of a lake on Baffin Island. We heard two snow machines pull up and thought, “Who could possibly be out here?”

It was two young lads who were out hunting. They came into the cabin with a frozen caribou leg in a garbage bag. Caribou was one of my favorite things on the planet. They had a sharp knife, so they’re carving the caribou meat and it’s coming off like carpaccio. I’m looking at it and I wanted to eat it, but in my mind, I have the doctor saying, “Don’t eat anything raw, uncooked, or undercooked.” But I said, “Give me that caribou.” I didn’t even care. Sometimes, you have to let loose.

Every time I see my oncologist, I say, “You gave me my life back,” and he says, “But you weren’t going to die. I had your back. You’re not going to die. We may have to do this again in 10 years.” I said, “No, doc, you don’t understand. You gave me my life back. A life that I love. You gave me my job back. You gave me the ability to go and do the things, to run up a mountain, to do the things I do and do them well. It’s a gift to have this back.” Every time I see him, I tell him the same thing.

There’s something about the Mojave Desert in Southern California that I absolutely love. I keep going back. I’ve crossed x almost every large desert on the planet, but I love Death Valley in the Mojave Desert. So after chemotherapy, I trained. I said, “I want to go from the northernmost point in Death Valley National Park and go south about 100 miles, completely cross country to the Badwater Basin, and do it in July, the hottest time of year, and with limited resupplies.”

I did that two months after finishing chemotherapy and I wasn’t ready. They had an anomalous windstorm where the winds were hitting me head-on. It was world record heat. I had to stop. I did several trips around the world guiding and then decided to go back the following July, which was in 2024, and I was successful in going from the northernmost point to the Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America, completely cross country, 53 hours of moving nonstop, over the gnarliest terrain on the planet, at 120°F.

It was so hot that I was seeing double, but I love the heat. Then I guided, did some trips, and did some Impossible to Possible youth expeditions in Chile and other places. The last big trip I did was this past winter. I crossed Ellesmere Island in 28 days with my teammate Kevin, dragging all of our supplies across 500 km, and living out of our tents. It was epic.

I said in the movie, “The greatest challenges that we face in our lives are 90% mental and the other 10% is all in our heads.” It’s 100% your choice how you’re going to take on that diagnosis. When you reach a crossroads, you can go right or left. It’s 100% your choice. And that is on every diagnosis. We have to choose to fight or give in.

Once you say you’re going to fight, that leads you down another road with another branch on it. Are you going to fight with passion or fight and then give in? It becomes a series of choices. You have to realize and accept that this is something. This is an adventure. This is a challenge. And I don’t say adventure in a way that’s romantic and happy.

This is going to be the most difficult challenge that someone will go through in their life. You are not choosing to do it. It’s being thrust upon you and it’s your time to rise to the occasion. You’re called to stand up and do everything you possibly can, not just for you, but for everyone around you, even for those who will come after you or people you’ve met in your life. You may need a game. It’s on you to make that decision. And when you choose to go into the affirmative, which I hope everybody does, and you’re going to go after this, fight with passion.

Every person, deep down inside them, has a capacity for a form of greatness. Maybe in their great dreams, they think they’re going to be a rock star, a great artist, or an incredible athlete. Rising to the challenge and being great means fighting this disease that you’re up against with no idea the kind of person you’re going to be when you come out the other end.

One thing about life that’s not mysterious is that we are in control of who we are. We define ourselves. We don’t allow things to define us. You survived that cancer. You’re not a cancer survivor. You are a person who defeated cancer.

If they caught it any later that it would turn into scar tissue and I would no longer be able to create healthy blood cells, they don’t know. There’s very little research on this type of lymphoma because there are so few diagnoses. Most of the time, old people get it. I think back to the years of obvious signs. My oncologist said, “You’ve had this thing for years for sure.” I thought back to three or four years before the diagnosis and now I could see it, but I didn’t see it then because you slip into a way of existing and think it’s normal. You forget what it feels like to feel good.

The biggest symptom was getting weird infections constantly because my system was so depleted. It still is. It wasn’t from the chemo necessarily. I was always getting something. If I walked into a room and even if someone who had a cold was in the other part of the room, I was getting that cold. I was getting weird skin rashes and infections. I had shortness of breath and dizziness. It felt like wool was packed in my head, which is why I thought I had long COVID. I had issues digesting certain foods. When I’d go for a run, all my fingers would be white and I wouldn’t be able to feel them, but I don’t experience it now.

Inspired by Ray's story?

Share your story, too!

More Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Stories

No post found