The Power of Positivity and Advocacy in Mary’s Stage 4 Endometrial Cancer Care

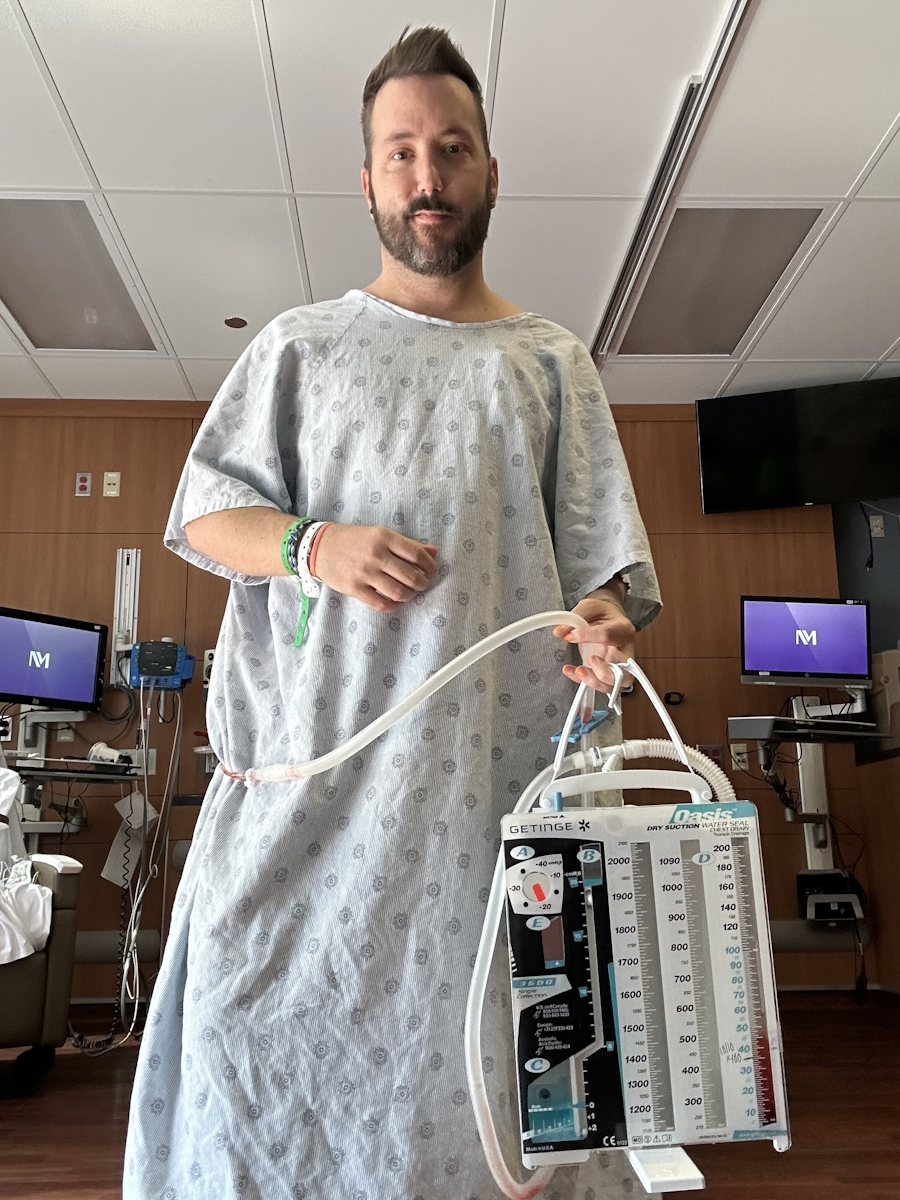

Mary’s story is a reminder that life can shift in an instant, but so can your focus, priorities, and resilience. In September 2023, she was diagnosed with stage 4 endometrial cancer (stage 4B) after a late-night ER visit with the symptom of sudden right-side pain. Until that moment, her only clues were unusual fatigue and a couple of unexplained UTIs, which she and her doctors linked to her recent diabetes diagnosis.

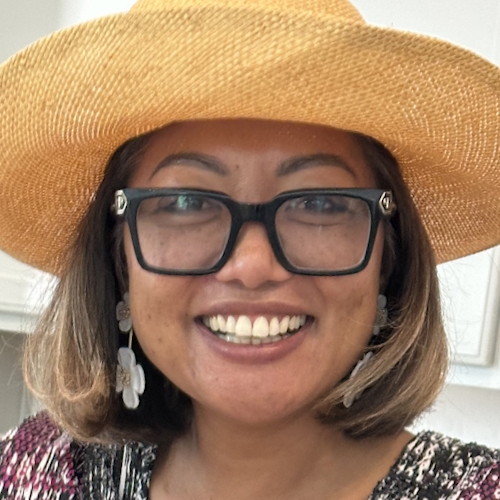

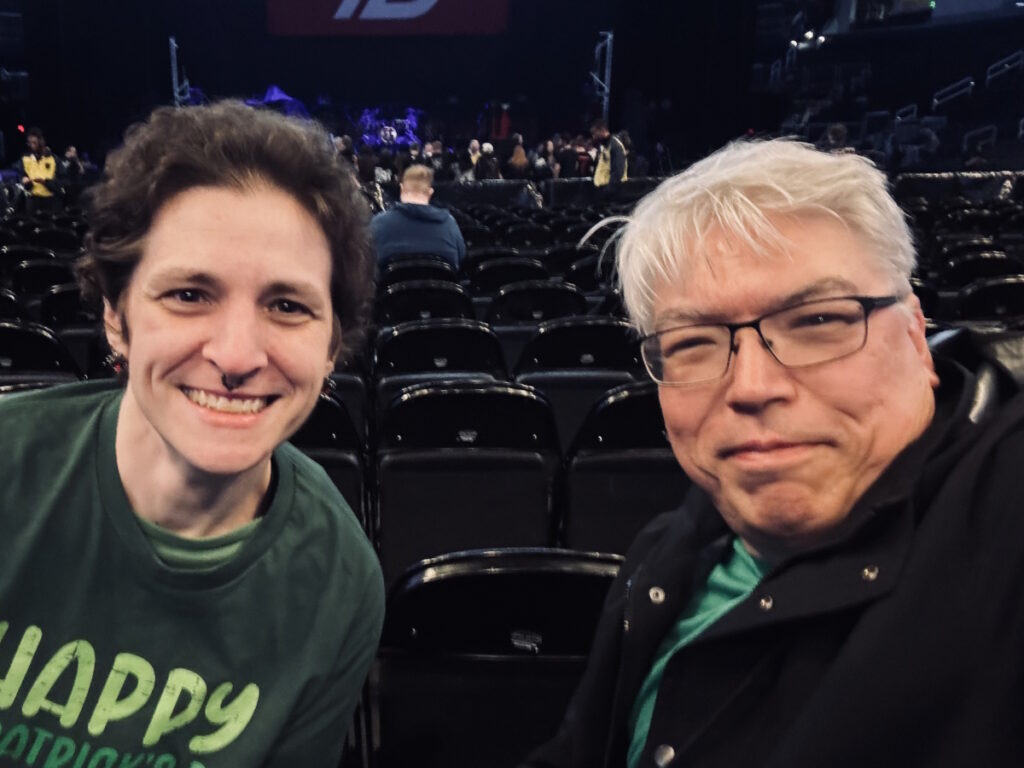

Interviewed by: Taylor Scheib

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

When scans revealed a mass, things moved quickly. She was scheduled for a procedure that same night to place kidney stents, a fast referral to oncology, and eventually an open hysterectomy in late October. Surgeons discovered the cancer had spread to both ovaries and fallopian tubes, but thankfully not to other common areas like the bladder or liver.

Mary’s approach from the start was grounded in trust, education, and a commitment to living fully. She leaned on a stellar care team that developed a treatment plan tailored to stage 4 endometrial cancer. This included six rounds of chemotherapy, followed by ongoing immunotherapy infusions.

While the fatigue and bone pain from treatment were rough, Mary says she fared better than many, avoiding severe reactions or illness. She also benefited from strong advocacy within her medical team, especially when insurance initially balked at covering her treatment before it was officially approved for endometrial cancer.

Her mindset was to stay positive, stay involved, and to keep doing what matters. Mary believes in being an informed, proactive patient by researching enough to understand her stage 4 endometrial cancer diagnosis, asking questions, and trusting her doctors when evidence-based recommendations aligned with her needs. She encourages others, especially women, to listen to their bodies, push for answers, and not dismiss even small changes in health.

Outside of treatment, Mary continues to work, travel, and immerse herself in the hobbies she loves, from antiquing to gardening. She makes time for concerts, dinners with friends, and family trips, including a bucket-list Alaska cruise in the works. Her community of family, friends, and neighbors has been a lifeline, stepping in with meals, rides, and everyday support. For Mary, this experience reinforced the value of connection, self-advocacy, and finding joy in both small outings and big adventures.

She hopes sharing her experience helps others learn about stage 4B endometrial cancer, the importance of early evaluation, and the reality that advanced disease still has multiple treatment paths. “It’s about living your life,” she says, “and not letting fear keep you from what matters most.”

Watch Mary’s full interview to find out more about her story:

- How a late-night trip to the emergency room changed Mary’s life

- The treatment decision that made all the difference for her

- Why she says attitude is just as important as medicine

- The surprising role her friends and neighbors played in her care

- Her must-hear advice for women about paying attention to symptoms

- Name: Mary M.

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 58

- Diagnosis:

- Endometrial Cancer

- Staging:

- Stage 4B

- Grading:

- Grade 2

- Symptoms:

- Unusual fatigue

- Urinary tract infections

- Extreme pain on the right side of the abdominal area

- Treatments:

- Surgery: hysterectomy

- Chemotherapy

- Immunotherapy

Thank you to Karyopharm for supporting our independent patient education content. The Patient Story retains full editorial control.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- Introduction

- When I First Felt Like Something Was Wrong

- What Happened in the Emergency Room

- Learning About Endometrial Cancer

- My Husband as a Care Partner

- The Support I Received from Family and Friends

- How I Found My Care Team

- My Reaction to Finding Out I Had Endometrial Cancer

- My Treatment Plan

- The Side Effects I Experienced from Treatment

- Playing a Role in Treatment Decisions as a Patient

- Talking With My Care Team About Clinical Trials

- How I Continue to Live My Life

- What I Want Others to Know

Looking back, I probably had a couple of symptoms that I did not realize.

Introduction

My name is Mary and I was diagnosed with stage 4 endometrial cancer (stage 4B) in September 2023. I have a husband and two kids, who are now 21 and 20. We adopted our kids from Guatemala and they have been with us since they were babies. After we had fertility issues, we decided adoption was the way to go. It was easy for us because my father-in-law is adopted and I have some cousins who have adopted children, too.

I grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, and have lived here my entire life, except for the time I went to college at the University of Missouri, which is two hours away. I’ve spent most of my life working as a paralegal.

I enjoy doing so many things. I love gardening. I love walking. I like spending time with my family. I do a lot of antiquing, whether it’s painting furniture, refinishing things, redoing things, trying to critique things, or creating things to make them a little better than when I got them. I have booths at two antique malls in St. Louis.

I like hanging out with friends. I love live music, concerts, and musical theater. I like to read. For many years, I wasn’t able to read much, but I’ve got a little bit more time to do that now, so I’m trying to read some things I haven’t read. My favorite genre is murder mysteries.

My family and friends would probably say that I have a good sense of humor. My kids would say I can be judgmental at times, although I try to do my best with that. It’s usually done in good humor and not in a mean way.

I have done so much volunteer work over the years. I love to do volunteer work, like with the parent-teacher association at school. I love to travel. I like to go to places I’ve never been before. I don’t want to always go to the same place. I like seeing something new.

My daughter would say I’m always dressed up. I don’t feel like I’m fancy, but I do like to wear dresses and I’ve always liked to since I was a child.

I started having pain in my right side, which was pretty intense and I have a pretty high pain tolerance.

When I First Felt Like Something Was Wrong

Looking back, I probably had a couple of symptoms that I did not realize. I was a little more tired and I am not a napper. I’ve never been a napper, so I should have known that was something.

I had a couple of urinary tract infections (UTIs) and I also never had a UTI before. I’m diabetic, so they were always assuming it had something to do with it, but I had only been diabetic for about a year, so that was still new. They thought it was diabetes or kidney-related. I was put on some medicines and the UTIs went away.

One evening in September, I started having pain in my right side, which was pretty intense and I have a pretty high pain tolerance. It was 10:30 p.m., so I thought I’d try to sleep it off, but if it’s still bothering me in the morning, I’d call the doctor.

It didn’t occur to me to take some pain medication. I don’t like to take anything I don’t have to take. I remembered my mom having her gallbladder taken out when I was in high school. I thought that if anything’s wrong and they need to take my gallbladder out, I probably shouldn’t have anything in my stomach.

It kept hurting, so my husband and I finally decided that since it’s 2:00 a.m. and no one’s getting any sleep, we should go to the emergency room. We looked at the online check-in and there was no line, so we took it as a sign to go since nobody was there and we live 15 minutes away.

At the ER, they initially thought it was my gallbladder. Then all hell broke loose after that.

‘We think something is pushing on your kidneys, so we need to put stents in.’

What Happened in the Emergency Room

They took us in right away. They checked my blood pressure and temperature, and asked a million questions. I hadn’t had any issues prior. I wasn’t having intestinal issues or inability to tolerate spicy food. Nothing weird had been going on.

They started with an ultrasound and gave me pain meds through an IV. During the ultrasound, I thought, “Could she push harder on this area? It’s painful.” Then she said, “We need to do a CT scan.” It all happened quickly because the ER wasn’t crowded. During the scan, he said, “Oh, yeah, I don’t know. I see something in there.” They don’t tell you anything at that point.

We go back to the room and my husband said, “I’m going to let the dog out.” I said, “Let the dog out? Can’t we call a neighbor to let the dog out?” He left to let the dog out and not even 15 minutes after he left, two doctors came in. They introduced themselves and they were very pleasant.

They said, “We think something is pushing on your kidneys, so we need to put stents in. There’s some kind of mass in there. We have an opening and we can do it at like 8:45,” which was 45 minutes from then. It all happened very fast.

I still see the urologist whom I met that night. He’s a nice, very comical guy. I like his personality. He’s a little younger, so I like that too, because I don’t want to have a whole bunch of doctors who are older than I am.

After the procedure, they decided to let me stay the night. I had a temporary catheter in and they wanted to make sure everything was okay. Back in the room, the doctor came in and said, “The surgery went great. We got the stents in. They can stay in for up to three months. We’re going to have an oncologist come in.”

Until he went in to do the hysterectomy, he still thought it was ovarian cancer. It turned out to be endometrial cancer.

At that point, I thought, “Wait a minute. What’s going on?” That was the first time anybody mentioned cancer. I thought about it when they initially said mass, but I wasn’t putting the cart before the horse. My oncologist ended up having a bad reaction to his COVID shot, so he couldn’t come in until the next morning.

When he came in, he said, “We’re going to have to do some more tests. We need to do a PET scan, but I see something on your ovaries. I think you have ovarian cancer. I’m going to schedule a PET scan. I need you to come into the office next week.”

Everything moved quickly. You hear some people who wait forever trying to get in. It was all very fast for me. I was wondering if it was good that everything’s happening fast or if it meant it was bad because everything’s happening.

The following week, I had my PET scan.

Learning About Endometrial Cancer

I got scheduled for a hysterectomy. He was going to be out of town, so he didn’t want to do it for a few weeks because he wanted the stents to have a little time to heal. I had my hysterectomy on October 30. It was an open hysterectomy, not laparoscopic.

Until he went in to do the hysterectomy, he still thought it was ovarian cancer. It turned out to be endometrial cancer. It had traveled to both ovaries and fallopian tubes. It was a large tumor — grapefruit-sized, is what he said.

I had already gone through menopause. I had just turned 58 when I was diagnosed. I went through menopause four years prior. I didn’t experience menopause like other people have. I didn’t get hot flashes. It was just my face that got hot. I did not have the worst experience. I know so many endometrial cancer patients have had bad periods and bad bleeding, and I never had that.

The worst part was calling to tell the kids since they were both away at college.

The worst part was calling to tell the kids since they were both away at college. It would have been different if I were able to tell them in person. It was hard on them because my brother passed away a year before due to complications from COVID and they were close to him. He was young and he wasn’t sick before that. He had a bad two years, but it was all COVID-related.

We told them before the hysterectomy because it took about a month to get the hysterectomy. My son was freaked out. He wanted to come home that day and I told him, “Let’s wait. Let’s see what’s going to happen. I’m still at the hospital.”

Two days later, he came home. He didn’t have a car, so he asked somebody to drive him home. It was a friend he’s had forever, so it was nice. He lives near us and they went to preschool together.

My daughter came in the following weekend. She took a train from Chicago. I think they felt better. I think they thought I was going to look terrible and I looked normal. I don’t look sick. You can’t always tell somebody’s sick by how they look.

My Husband as a Care Partner

He’s incredibly supportive. He will do anything for me. He drives me anywhere I need to go. I can drive and do all those things, but he is very ready to help with everything all the time. It was a change because I’m the motivator of everyone in the house. If something’s going to get cleaned, it’s because I’m motivating people to clean.

He was upset. He was trying to keep himself contained, so I didn’t see him upset. I got more upset. We’re not crazy emotional. One of his sisters is a nurse, so he was on the phone with his sister, when I didn’t know he was on the phone, trying to figure out what was going on and how things were.

The support I have had from friends and family has been amazing.

The Support I Received from Family and Friends

The hardest thing is telling everybody. I have several groups of girlfriends. He was also talking to a couple of my girlfriends on the side, telling them what was going on. It was a lot, but I think he was trying to take over everything.

I’m the super positive one. I always think everything’s going to work out no matter what. Through this diagnosis, through everything, I still think it’s all going to work out. We’re going to make it work. Whatever we need to do, we’ll do.

I have one sister. Telling her was hard, too. The nieces and nephews are all concerned. There was a ton of concern. Even the neighbors were concerned.

One of my grade school mom friends set up a meal train. People were bringing food every day. People were asking, “What do you want? I can make this, this, or this. What do you want?” People were texting me. Neighbors were bringing food, mowing our lawn, and doing whatever we needed done. Everybody was great.

One friend even asked, “Can I come clean your house?” I declined and said, “No, you’re not cleaning my house. It’s okay.” I did let my sister clean my house a little bit, but other than that, we managed to get it done between feeling crappy and not feeling crappy. We’re making it work.

I feel bad for people who don’t have support like that because the support I have had from friends and family has been amazing. My husband has four sisters and they’re all very supportive. We had different kinds of support from different people. Everybody’s sharing what they’re good at. I have a friend who always wanted to buy. “What do I need? What do you need from the store? What can I get for you guys? What can I do?”

It was nice to know that people care and want to help. You don’t expect something like this to happen, but when you do, you want to make sure somebody’s there to help you. I have had so many people offer to bring me to chemo appointments. One time, I had a friend from college drive in from about six hours away to bring me to chemo. That was above and beyond. It was very nice.

I liked my doctor. He was experienced and a good surgeon, so I had the right fit going in.

How I Found My Care Team

It didn’t occur to me that I should be looking around for somebody different. I liked my doctor. He was experienced and a good surgeon, so I had the right fit going in. The team at his office was amazing. Everybody was great, from the physician assistant to the chemo nurses. They did everything I needed done, so I didn’t have issues with anything.

My doctor fought for my infusions. She said, “They don’t want to approve it, but I’m going to keep talking to them until they do.” I said, “Okay, if that’s what you think I need to do.” I didn’t even know what endometrial cancer was when I was diagnosed. My husband and I are not medically informed.

I have several friends who are nurses, so we ask them, “What does this mean? What do you think about this?” One of my nurse friends had breast cancer, so she knew a lot. One of my good friends had breast cancer, so we could talk about chemotherapy and all of those side effects, which was helpful.

My care team was a great group. My doctor left his practice, so I ended up finding a new oncologist. My first appointment with her was in March 2025. She was with my former oncologist and he was a great surgeon, so everything worked out. He got me on the right path and we’re continuing with everything through my new doctor and she’s great as well. She’s easy to talk to and takes time to listen, which is important because it’s easy for me to bring things up.

My oncologist had a great treatment plan and I was happy with it.

My Reaction to Finding Out I Had Endometrial Cancer

It was upsetting, but no matter what it was, I still would have gone through treatment. At least, they knew what it was. It was something that they treated before, whether they didn’t think it was curable or not, which they don’t think is curable. However, I still could go into remission sometime. I feel like they’ve done everything they can.

I already had my big cry. I’m the type of person who, when I cry, I’m done. I’m not going to keep crying. I know everybody’s different, but I’m not going to keep crying every day about it. Some days were more emotional than others.

My Treatment Plan

You need to be aware. You don’t want to push people, but you need to know your treatment plan. My oncologist had a great treatment plan and I was happy with it. I’ve had six chemo treatments, then immunotherapy infusions with chemo, and then 13 standalone immunotherapy infusions.

He said, “Even though your endometrial cancer was in more places, it was better than I thought. Even though it’s advanced in stage, I feel like it was very contained. It wasn’t in your abdomen, your liver, or your bladder, which are common places for endometrial cancer to go. You were very lucky it stayed where it was.” When they did the pelvic wash, they didn’t find any cells in the pathology, any cancer cells out and about.

There’s this small nodule on my lung that they’re watching. They’re unable to biopsy it because it’s too small. He thought that the endometrial cancer had traveled there, but there has been no change on any scans. My current oncologist doesn’t think it’s cancer.

When I met with them, we talked about the treatment plan and what we were going to do moving forward.

The Side Effects I Experienced from Treatment

The chemo side effects were not good. It was mostly fatigue. The bone pain was terrible, but there wasn’t much that I could do about it. The best thing for me was heating pads or ice packs, which sounds weird because even in the middle of winter, I’d still use ice packs.

Chemo days were hard, but I wasn’t emotional about it. We had to get through it. I’m the caretaker. I have to make sure that everybody’s okay and making the right decisions. I’ve never been sick before. I had an ovarian cyst removed 25 years ago, but that was done laparoscopically and was the only surgery I’ve ever had. I’ve never broken a bone. All this was new.

Playing a Role in Treatment Decisions as a Patient

When I met with them, we talked about the treatment plan and what we were going to do moving forward. Hopefully, this chemo would get rid of anything that might be hiding in my body.

The chemo nurse was available all the time. If I had questions, she said I could call anytime. They were always very flexible. I didn’t have a lot of weird things I needed to call about. I would wait until I had a couple of questions before calling her, but she was always very helpful, very friendly, and willing.

He said I was the right candidate for the immunotherapy. Luckily, I didn’t have many side effects.

When I would have an infusion, I would notice people who were having serious side effects. I didn’t have any reactions, so I was hoping that it worked out for them. I also noticed a lot of ladies who were older than me and I felt bad for them. It wasn’t fun at my age, but it has to be less fun when you’re older.

My oncologist sent me to the wound care specialists since I was diabetic. He wanted to make sure everything healed properly. Thankfully, I had no problems, but I was happy to have another set of eyes.

They even had a nurse come to change the dressings twice a week. We could do that at home, but I was happy for them to do it because they could tell if something didn’t look right because I wouldn’t know. We’re not medically inclined to know if something looks bad. Thankfully, my incision healed well. I didn’t have any issues. It was all smooth sailing.

Talking With My Care Team About Clinical Trials

My doctor discussed clinical trials and said, “Even though it’s not FDA-approved for endometrial cancer until June 2024, I want you to do this. It’s one of the newer treatments for endometrial cancer.”

Radiation wasn’t recommended for my stage and grade, which was fine because I felt like the treatment I had was good. He said I was the right candidate for the immunotherapy. Luckily, I didn’t have many side effects from immunotherapy. I would have fatigue on the day of and the day after, and then I’d be fine.

I have an infusion every six weeks. I’ll have a scan to see how things look. Hopefully, everything will be good. There’s a lot to say about having a good attitude, trying to still live your life, and doing what you want to do.

If my insurance is going to cover it, if the doctor’s on top of what he does, and if that’s what he recommends, then I’m all for it

I did minimal research and read all the side effects, but I don’t do that anymore. My doctor’s a gynecological oncologist. There were good statistics from the clinical trials and it worked well for some people. If my insurance is going to cover it, if the doctor’s on top of what he does, and if that’s what he recommends, then I’m all for it. Thankfully, it all worked out.

Keytruda has been approved for 18 different cancers now. Hopefully, it’s helping a lot of people feel better and be able to live their lives. The main thing is to be able to live your life, have time with your family and friends, and do what you want to do. None of us ever knows how much time we have.

How I Continue to Live My Life

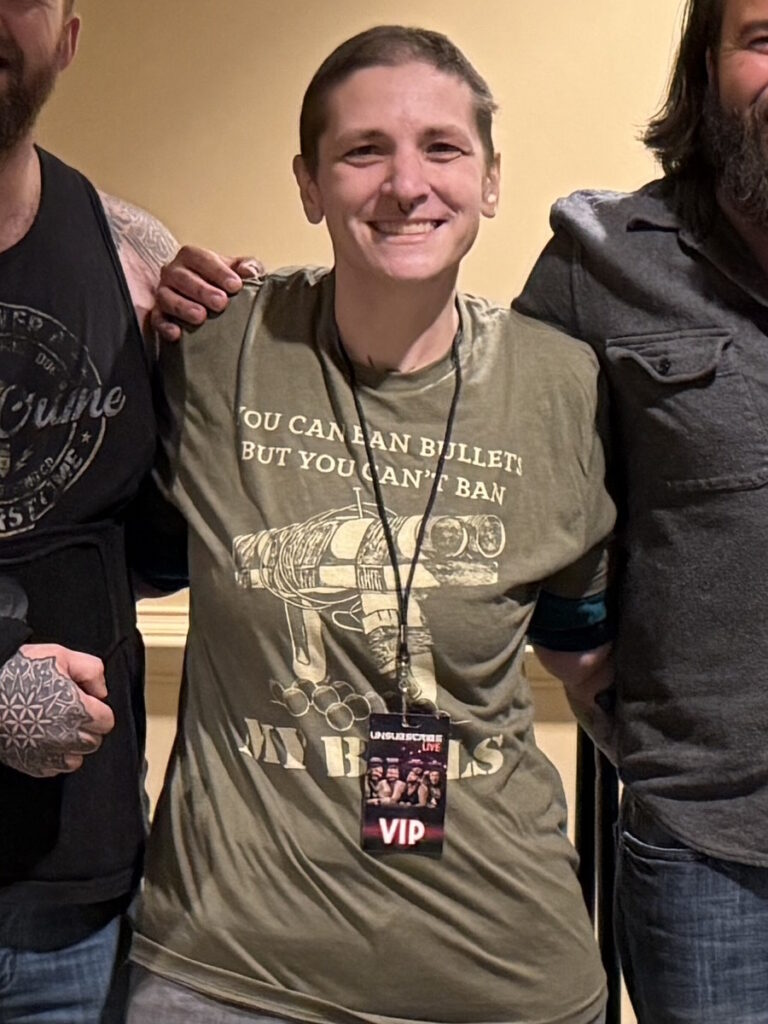

I don’t want to sit in my house all day, every day. I have two part-time jobs. I like to go out and about. I’ve scaled back on volunteering, but that’s something I want to get back into. I taught English as a second language and citizenship classes before, which I enjoyed and got a lot out of. I always have something I want to do. We love to go to live music. I like to see concerts. I like to go out whenever I can, whether it’s something small and local or a big concert.

In 2024, I decided I wanted to see Green Day, so we went to Milwaukee and saw them. It was a bigger festival and we saw four bands. I thought, “Am I going to be too tired to do that? No, let’s get the tickets. Let’s just go. I’ll make it work. I can sit down if I’m tired. I’m not going to be so tired that I fall asleep.” It all worked out and we had a great time.

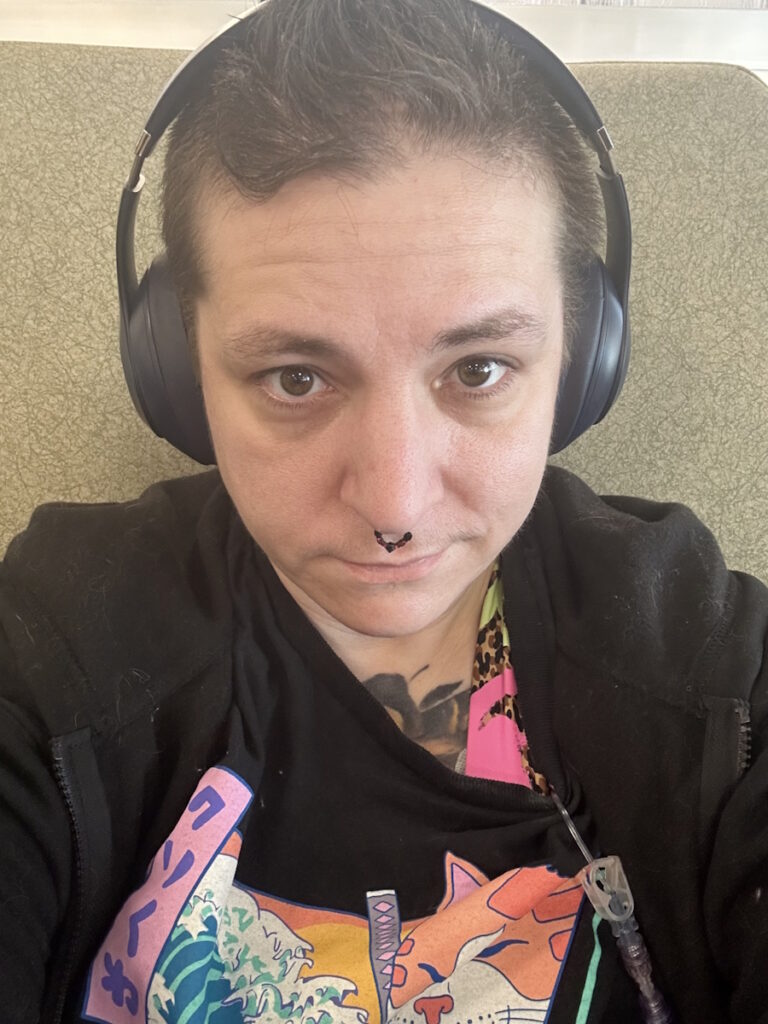

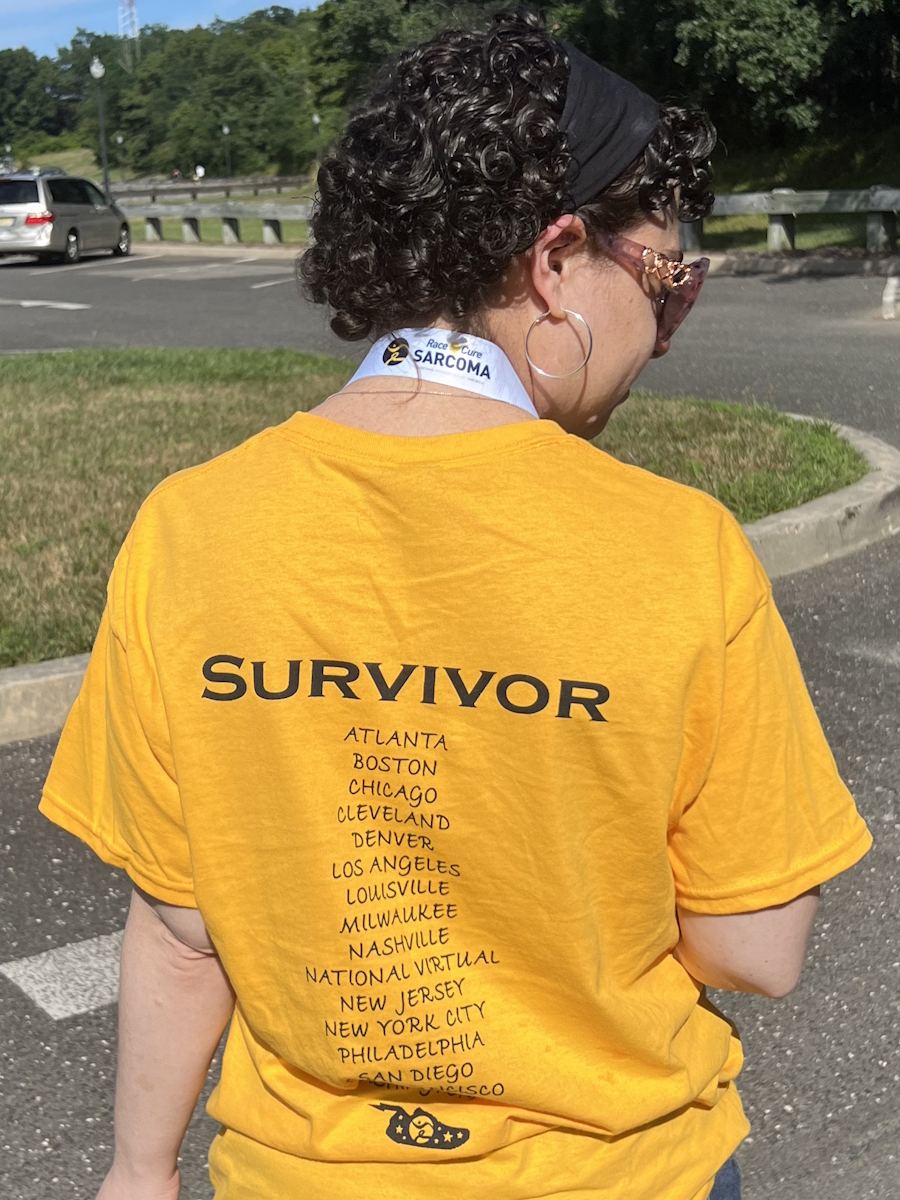

I’m happy to have my hair back. It was crazy curly at first. I shaved it once it started falling out a little bit.

We’ve done a couple of trips with the kids and we’re planning a couple more. I’ve always wanted to go to Alaska, so we’re going on a cruise in 2026. Some of them are bucket list items, but we like to go on vacations. If I had more money, I could vacation more.

I like going out to dinner with friends and trying new places. You have to do the things you love. I still paint my furniture. I love to decorate. I like to help somebody when they need something. I’ve scaled back on those things.

In 2024, we had a ton of graduation parties. For the first couple of parties, I wore a wig. When my hair was a little bit longer, I decided to go without a wig and it was fine. It was a whole new look. People have asked, “Are you going to dye your hair?” I’m getting used to it now. I wasn’t planning on going gray, but you do what you have to do and embrace what you have.

I’m happy to have my hair back. It was crazy curly at first. I shaved it once it started falling out a little bit. Everybody has a different opinion. Some people do cold capping. I thought I would freeze to death if I did that. It wasn’t covered by my insurance either, so I would have had to pay out of pocket.

So much of you is attached to your hair. I thought, “How does my hair look? I didn’t get my hair cut. Do I need to color my hair?” I wore a lot of knit hats. It was wintertime, so that all worked out.

Because this happened to me, I’m better about connecting with friends whom I hadn’t seen in a while.

Doing what’s important to you and spending time with people who are important to you is a big deal. It makes life better and it makes me happier. I have my animals and that’s fun too.

We still have to enjoy the time that we have. It’s always been important for me to do what I want to do. They don’t have to be expensive. You can go to a park, a free concert, or a botanical garden. They aren’t expensive activities, but they’re fun and if you like to do them, do them.

I feel like I’ve always had a positive attitude to some extent. My husband would say, “She always wants to do something.” My daughter would say, “She always has a list of stuff.” I have different lists, like things we need to do or things we need to get at the grocery store. I have a list of major projects, like painting the bathroom or repainting the kitchen cabinets. I have always wanted to do those and I’m now more motivated to keep moving forward.

I’ve always felt like there are things I need to do. My grandmother was like that. She was a sewer, a gardener, and a doer. I feel like I got a lot of that from her. She was probably a little tidier than I am, but we always used to do about that when I was a kid.

I’ve always had a positive attitude. I graduated from college and got my master’s. I got student loans, but I was still able to do it and enjoy myself while doing my best.

I have a religious side. I’m Catholic and I think that should be part of your life too. Hope is part of it. I have always hoped that something better is around the corner, whether it’s politically or environmentally, or whether it’s somebody finding a cure for something or a drug that will help a type of cancer or disease. There should always be hope that something good will happen.

I don’t know if any of that is religion-based. If I didn’t have any religion in my life, that’s how I would feel anyway. You need to be hopeful and hope that things are going to work out. Do they always work out perfectly or as you expect them to? No. Does everything happen for a reason? Probably. I don’t know. We don’t always know what that reason is, but I don’t feel like I was cursed with cancer. I don’t think that’s the way it works.

Take the things that happen in your life and turn them into good things. Because this happened to me, I’m better about connecting with friends whom I hadn’t seen in a while, like my college girlfriends. I invite them to get together. It doesn’t have to be a big, fancy trip. It can be getting together at somebody’s house and having a drink or an appetizer. Spending time with people makes your life more hopeful. Keep doing what you can do as long as you can.

If you truly think something is wrong, you’re going to have to push for yourself… Nobody’s going to advocate for yourself better than you.

What I Want Others to Know

If you feel like something’s off or not right, if you’re experiencing a symptom, even if you don’t think it’s anything, contact your doctor. Maybe it’s something, maybe it’s nothing.

Sometimes doctors will say you’re fine. If you truly think something is wrong, you’re going to have to push for yourself. A family member might, but you need to advocate for yourself. Nobody’s going to advocate for yourself better than you.

There needs to be more education about endometrial cancer. Would I have known I had it? I don’t know, but I wish I had read about it before it happened. I hope that everybody who knows me and hears someone tell them about something they’re experiencing would push them to see a doctor. Some people worry that they may seem like a hypochondriac. Those are usually people who aren’t hypochondriacs and people who are hypochondriacs don’t think they are.

Women are so busy with their lives and taking care of everybody else that they put themselves on the back burner. Take care of yourself, too. I don’t know if I would have known I had it. If I had other symptoms, maybe I would have thought about it more.

There are treatment options. Whether you’re stage 1 or stage 4, there are still treatments for you. You can do whatever you need to do to make yourself better. There are more things I could probably do to have a better lifestyle. It’s a different experience to have cancer. You don’t know what it’s like until you have it yourself.

Thank you to Karyopharm for supporting our independent patient education content. The Patient Story retains full editorial control.

Inspired by Mary's story?

Share your story, too!

More Endometrial Cancer Stories

No post found