Jason’s Stage 4 Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) Story

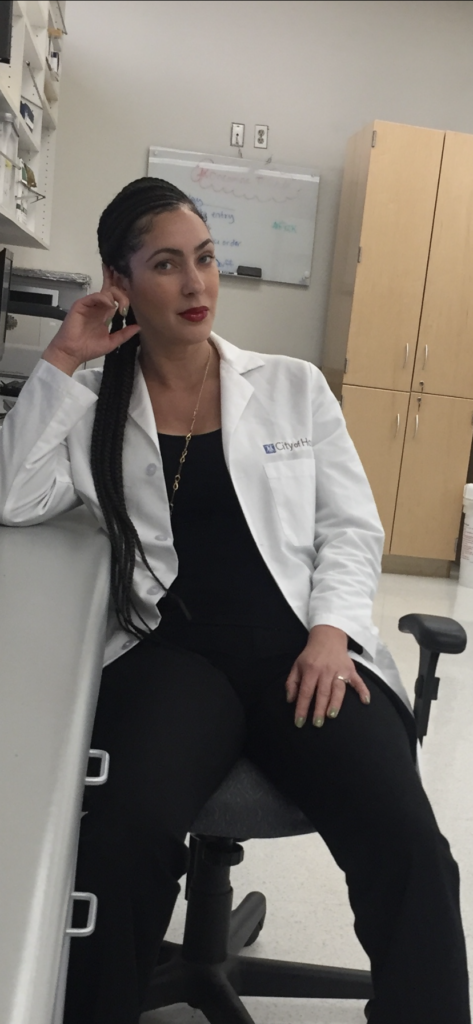

Jason is a New York entrepreneur, tennis player, theater-goer and traveler who says he loves the lights of Las Vegas.

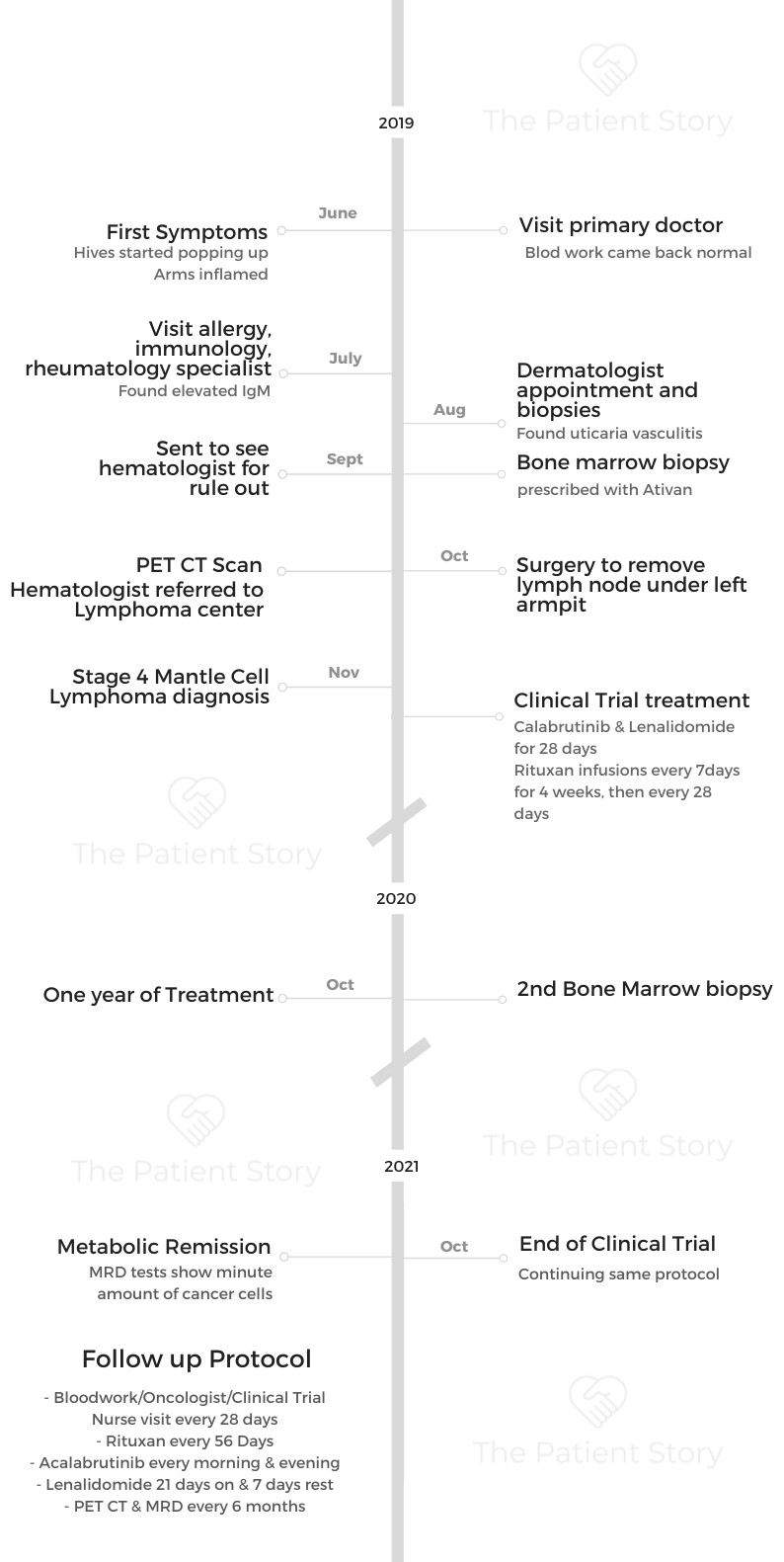

Things shifted in 2019 when Jason, at only 39 years old, was diagnosed with stage 4 mantle cell lymphoma, a rare blood cancer that is more common in men over 60 years old. His diagnosis almost turned his world upside down, and he was thankful he had become an entrepreneur prior to his own treatment.

In this video series, Jason shares his story of diagnosis, clinical trial, treatment and how cancer changed his life. His story is such an inspiring example of patient self-advocacy.

Thank you so much for sharing, Jason!

- Name: Jason W.

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- 1st Diagnosis:

- Age at DX: 39 years old

- Symptoms

- Hives

- Tests for DX:

- Bone marrow biopsy

- PET-CT

- Treatment:

- Acalabrutinib

- Lenalidomide

- Rituxan

- VIDEO: The Mantle Cell Lymphoma Diagnosis

- VIDEO: Treatment & Clinical Trial Experience

- VIDEO: Life After Cancer (Quality of Life)

- Mantle Cell Lymphoma Stories

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

VIDEO: The Mantle Cell Lymphoma Diagnosis

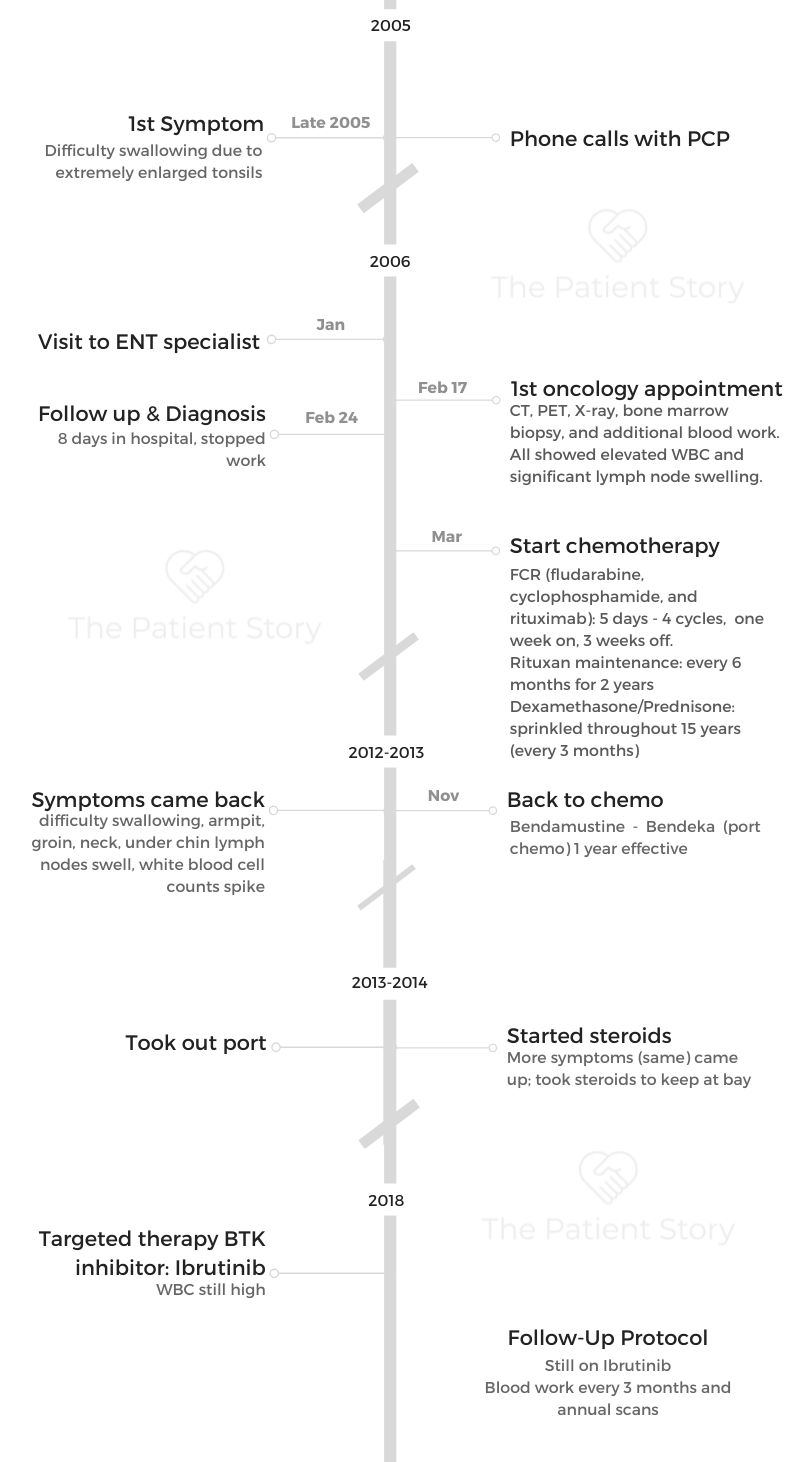

His blood work and everything seemed normal. Except for the increasing itch and pain from hives and inflamed arms, Jason and his primary doctor thought it was nothing serious.

Specialists couldn’t find anything until he was referred to a hematologist. A bone marrow biopsy and PET CT later confirmed cancer. Jason was diagnosed with mantle cell lymphoma at a very early age of 39.

About me

I’m in New York City, and pre-cancer diagnosis, I was an entrepreneur. I guess I still am, and I have a small business. I’m a tennis player, a theater-goer. I like to travel. I like to gamble. I go to Las Vegas pretty regularly. I’m most passionate about my business, which is a production supply and walkie-talkie production services company in New York City and Greenpoint, Brooklyn, which is a great neighborhood in New York City.

I’ve been in video production services for over 20 years. In 2017, I started my own company after being a freelancer for many years. That was actually kind of a magical experience because if I didn’t start my company, I don’t know how I would have fared this storm.

If I was still in the freelance world, producing shoots or working for somebody 40 hours a week, I think that I would have some pretty significant challenges dealing with the cancer diagnosis and the treatment and the ongoing treatment. Being an entrepreneur has been very lucky and fortunate for me.

I don’t think it’s anything to worry about.

My first symptoms

It was about 2.5 years ago, the summer of 2019, and the very first symptom was on my arms. I was getting a rash. It was very red and bumpy and itchy. It started on my forearms, and I really didn’t think much of it for the first 2 or 3 weeks. I really didn’t think much of it at all.

I was out to dinner with a very close friend of mine, Adrian, who happens to be a doctor himself. He’s a hospitalist at Weill Cornell, and he’s a really great doctor and a really great friend of mine. We were meeting up for dinner, and he said, “What’s on your arms?” I said, “I don’t know,” and he’s like, “you should have it looked at.” I said, “Yeah, I don’t think it’s anything to worry about.”

Another couple of weeks went by, and it was still there. His comment was sort of in my head, so I made an appointment with my primary care physician. I’m probably going 5 weeks after the first sign. I go into the primary care office, and at this point, there’s hives on other places than my forearms.

Mantle cell lymphoma diagnosis

The primary care physician says, “It looks like hives to me. Hives are really common. We get a lot of people in here with hives, and we run all sorts of tests and are looking into it. Most of the time, they just go away, and we never really figured out what it was.”

We talked a lot about it, like “Did you change your detergent, or did you change your soap?” Then he took a lot of blood and ran my blood work.

He’s a wonderful doctor. I love my primary care doctor. I still have him today.

He called the next day. “We got your blood results back. Everything looks perfect. Hopefully, this just goes away.”

I said, “Oh, great, blood work came back great. Hopefully, this will just go away.”

Time went by, and it started getting worse. It started spreading to other parts of my body. It started becoming more itchy, more inflamed. It went from just being on my forearms to being all over my chest and all over my stomach and down my thighs. It just sort of progressed.

I went back to see him again. He said, “I’m not quite sure with your blood work being right what it could be. Why don’t we look into going to an allergist, immunologist, rheumatologist-type person and a dermatologist?”

I went to somebody who had a specialty in all of those categories —allergy, immunologist, rheumatologist. We ran blood work like I’ve never experienced. The number of vials of blood that I gave and the number of tests that I did over the course of 2 months with this person was just over the number. The bill was also over the top. The only thing that came back was an elevated IgM. That was it. That was the only thing that came back irregular in my blood work.

The dermatologist initially said, “I don’t think these are hives. I think it could be something else.” While everybody thought it was hives, he said, “There’s a chance it could be this. It’s a rare thing. Let’s biopsy a few in a couple of different places on your body.” He biopsied, I think, 4 areas.

We ran blood work like I’ve never experienced… The only thing that came back was an elevated IgM.

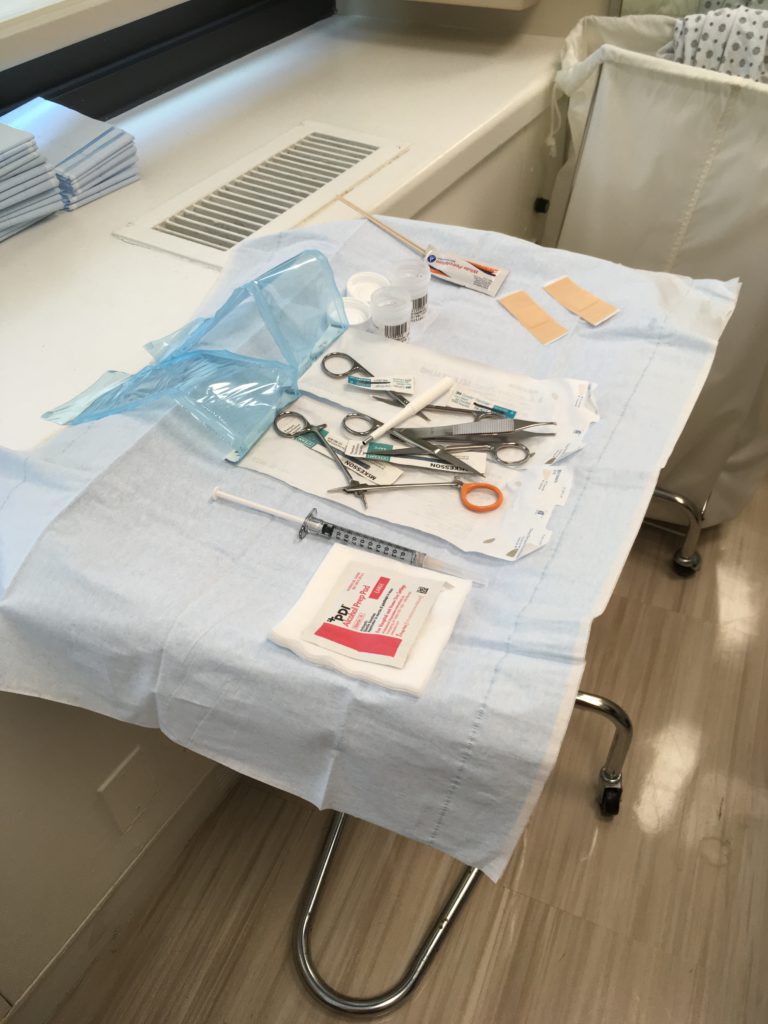

Describe the biopsy

It’s like a punch biopsy, where they basically think you have one hive that’s sticking up. They just take the whole thing and then send them to a lab.

They took 4 — took 2 off my back and 2 on my stomach, or something like that. Those came back as urticaria vasculitis, so that is hives. The vasculitis meant there were hives not only on top of my skin, which are traditional hives, but also under, in the derma.

I was getting hives basically on both sides of my skin, the exterior and the interior. We’re 4 or 5 months into this with me having hives, and they’re just progressively getting worse. There were some sleepless nights. It was unbearable not to itch them, and then it would create scabbing and blood. My sheets were tinted with blood spots.

It was painful. There were a few nights when the pain level was an 8 or 9. Looking back, I can’t believe I didn’t just go into the emergency room.

Looking back at what I was doing — laying in a bathtub and trying to throw ice all over me, doing all of these things to try and come at it — I should have just gone to the emergency room.

»MORE: Read in-depth patient stories and background on mantle cell lymphoma

This young girl comes in and tells me that we’re doing a bone marrow biopsy. She explained it to me, and I literally started crying.

Understanding pain tolerance level

The dermatologist gave me steroid cream, which was helpful. I put that all over, and it was really helpful.

As we were going through the diagnosis process, eventually I landed at a hematologist. The allergist-immunologist said, “I have to send you to a hematologist because you have an elevated IgM, but there’s nothing wrong with you. I assure you your blood work looks so great. But we have to do it. It’s called a rule out.”

I went to the hematologist, and I’m there for a rule out.

What’s a rule out? I don’t know what a rule out is. I went into the office, and they put me in a room. The PA (physician assistant) to the hematologist that I had an appointment with comes in and is very cheerful and says, “Do you know we’re doing a bone marrow biopsy today?

I was like, “What? What is that? I’m going in there for a rule out. I don’t even know what that word means.” Then this young girl comes in and tells me that we’re doing a bone marrow biopsy. She explained it to me, and I literally started crying.

What in the world is going on here? Then the doctor came in (the hematologist), and I’m crying, and she’s trying to talk me down. I said, “Look, you guys didn’t tell me that this is what’s happening. I could have mentally prepared for this. I could have brought my friend. I am not doing this today.”

How did the bone marrow biopsy feel?

For me, the gravity was maybe more extreme than most people.

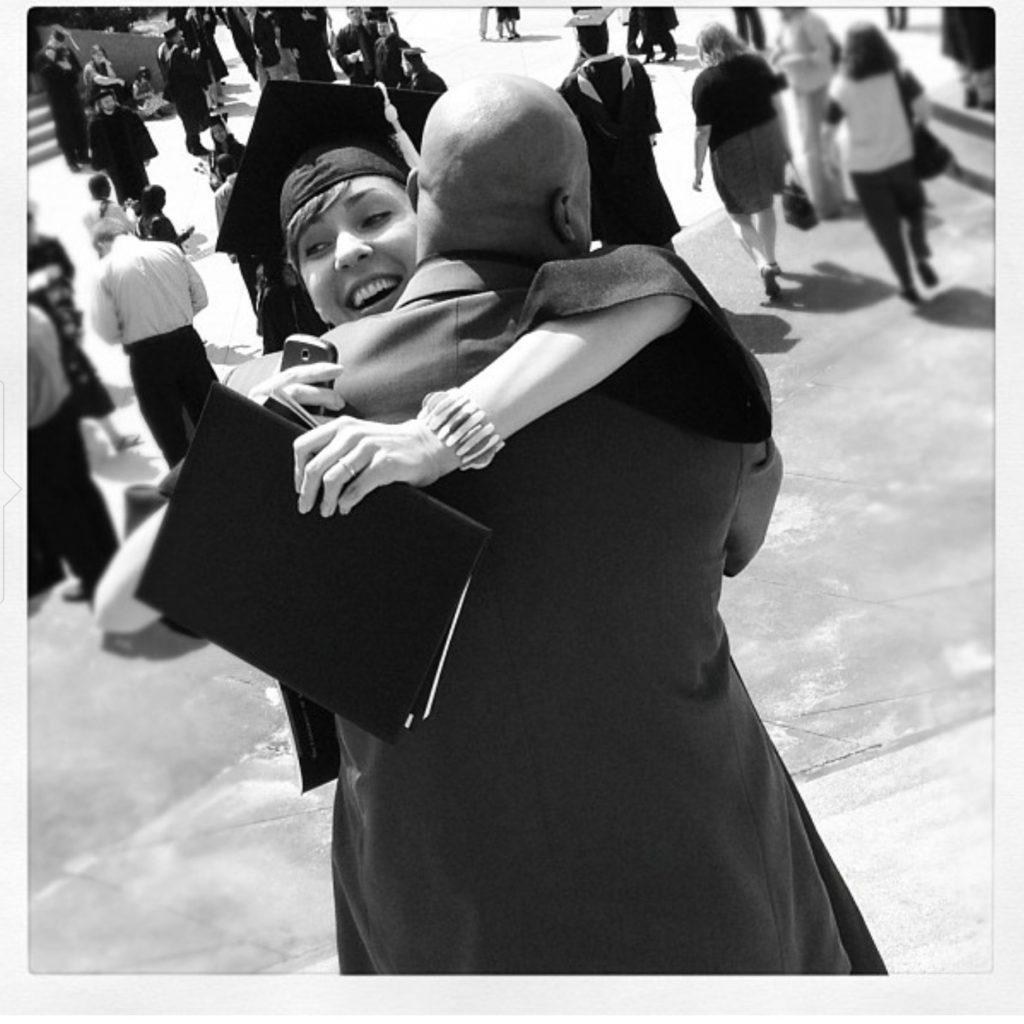

I watched my mom die of cancer. She died when I was 19 years old. When I was in that room, I didn’t think I had cancer. I thought I was going to a hematologist for a rule out.

I’m sitting there crying and upset, thinking, “Is this person thinking that I have cancer? Now I have cancer?” This hematologist is saying, “This isn’t that.” That was what she kept repeating. “What your mom went through — this isn’t that.”

They hadn’t diagnosed me, and it was supposed to be a rule out. I don’t think at that point anybody thought I had cancer, and that’s what I found along the way.

It was like, “I’m sure you’re fine. Don’t worry about it for like 5 or 6 months.” But actually, there was something very big to worry about.

For me, the emotion that was coming from there was, “I’ve seen people battle cancer. I’ve seen people die from cancer.” My mom wasn’t the only family member that succumbed to the disease. I have many aunts and uncles that have passed away from cancer.

I was very close to my mom. I was young and in high school during all of her treatments, witnessing all that. That was in the 90s. A lot has changed between now and then. I have to say, it was probably a lot worse to have cancer in the 90s than it is in the 2020s, based on what I witnessed when I was a younger person.

At that moment, the tears and the emotion that were happening in that room were like, “I’m in a hematologist office with this person who thinks I have cancer because they want to do a bone marrow biopsy. Here begins the torture.”

I had always said after witnessing my mom go through all that that I would never do chemotherapy. After I saw that, I said, “I’m never doing that.”

I haven’t done traditional chemotherapy, and it was a big part of my decision-making. To avoid it was probably historical.

My mom battled breast cancer for a long time. She had the initial cancer reoccurrence twice. Then I think she was battling it for that third time, but it had spread to her sternum. Then, from there, it went up to her brain. That’s ultimately how she went from cancer.

Guidance on people on PET-CT scan

They had basically said, “Okay. When can you come back?” I said I’ll come back in one week, and they said, “Okay, well, we also want you to get a PET-CT.”

I don’t know anything about a PET-CT. I don’t know what it is. Nobody tells me. I go, and I’m by myself.

There’s a nurse, and he’s very nice. I’m asking a lot of questions. He’s got to put an IV in me. I’ve never had an IV before in my entire life. He was asking me if I’ve ever had this done before, and I said no. Then he starts explaining what he’s going to inject in me. I said, “Is this dangerous? This sounds dangerous. Is this bad for my health?” It’s not something you should do. It is radiation and radioactive material.

He said, “If your doctor has ordered the test, then it’s probably really important that you do it.”

I said, “Okay, that makes sense.” But I had no idea what was going into it.

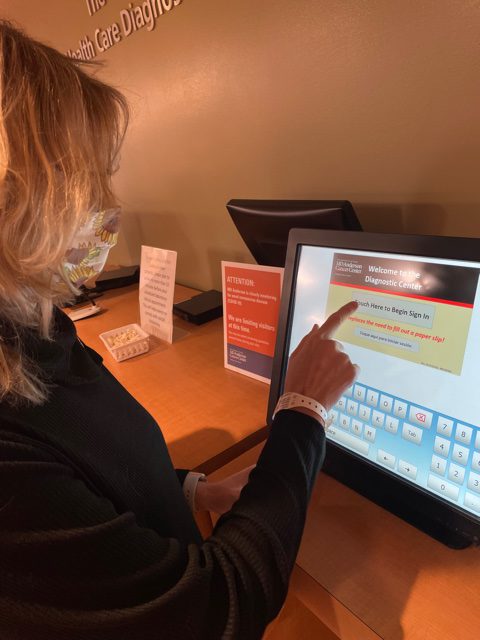

There was a lot of that — the first time going to the doctor’s office, going to the infusion center, getting a PET scan and getting a bone marrow biopsy. It’s really scary that first time. The buildings look so different the first time I go from the second time I go.

The first time I go, I just have this scary memory of them. Then as I go back over and over again, it fades, and they seem like normal places to me. But I can always remember the first time I go to a building and get that first thing I’ve never done before. It’s just like a very sterile, scary kind of situation, but it seems to fade away after you do it the first time.

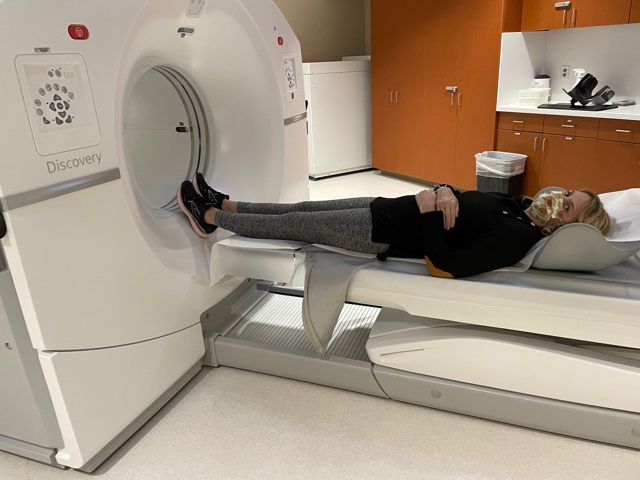

Describe the PET-CT scan

They set the IV and inject you with something that I still don’t 100% understand.

I’ve asked a lot of questions about it, but it’s like I get a piece of paper here in New York City that I have to carry around with me because they have monitors in the subways looking for dirty bombs, like radiation bombs. If you get a PET-CT, there’s a chance you can set one of those off, so I get a piece of paper walking around New York City.

They tell you don’t hug children for the first few hours when you’re done with it and drink a ton of water. You sit there for an hour in an isolated room. From the looks of it, the room is meant to keep whatever you’re radiating from your body from other people.

It’s a very lonely hour. You’re not allowed to bring a friend because you’re emitting something. When they’re guiding you in, they almost put some space in between them and you. Nobody’s getting close to you during that process and for a little bit after. Then, after the hour, they call you in.

They also will have you drink a substance while you’re waiting. I can’t remember what it is exactly. It starts with a G, but it’s basically sugar water.

It’s a very lonely hour. You’re not allowed to bring a friend because you’re emitting something. When they’re guiding you in, they almost put some space in between them and you.

You’re getting the injection of something going into your veins that helps them see imaging of your organs and lymph nodes. Then you’re drinking something that’s probably insulin or glucose-type base that’s going throughout your whole body. That’s sort of the magic for making the imaging.

You do that for an hour. You sit there, get an injected, drink all the juice. Then they bring you in, and you go lay down on a long, little table. Then they send you through a tube.

For me, because I’m stage 4, my lymph nodes are from my groin to neck. My scan probably takes longer than most people’s, depending on the type of cancer you have. For me, they start on my thighs, and then they go up to my ears. It probably takes about 28 minutes to do that scan.

You just sit there and don’t move for 28 minutes. Then they let you go with your piece of paper to get out of jail if you set off a New York City MTA radiation monitor.

Dealing with scanxiety

It’s not just about scans. It’s just that waiting period, essentially for any results or even before the procedure.

I’m not a fan of bone marrow biopsies. I don’t like them, and I will definitely be kicking and screaming if I have ever to do another one. We’ll need to work on some other ways of either medicating me more or making the experience better for me, because I don’t know if people know exactly what it is.

Still, they’re essentially taking a very long needle and jamming it into your lower back and going straight into the bone to the core of it and removing some marrow. At the same time, going back in where they went in and taking what’s called an aspiration, which is a small amount or a tiny piece of the bone as well. Sometimes they’ll even get marrow from 2 different spots.

I can’t imagine anybody would want to do that. I don’t like the experience at all. I’ve done 2 of them. I’ve done the Ativan (lorazepam) stuff. It wasn’t enough for me.

I always say I’m done collecting bad memories of bone marrow biopsies. If they want to do another one, we’re going to have to work something out. I don’t want to do it under the circumstances I’ve done the last 2.

I had a long wait to get into actually meeting my oncologists who I have now.

The hematologist who did the bone marrow biopsy — the first one who was doing the rule out with the PET scan — had sent my bone marrow out to the lab to see what it was. Before it went out, she said she took a smear of it, put it on a slide and looked at it under a microscope.

She said, “I can tell for sure you have B-cell cancer just by looking at it. I’m a myeloma doctor. I’m referring you to the Lymphoma Center. The bone marrow from the biopsy is being sent out to the lab. Your PET scans are still going through, but you need to call the Lymphoma Center. I referred you to somebody because I don’t do that. I do myeloma.”

Hearing and processing the news of cancer

It was literally on the phone with a doctor. I didn’t have a relationship with the same one who said, “This isn’t that.” It was a hematologist that I was sent to do a rule out.

It all happened very fast, and it was very shocking. I had no idea, and I would have never guessed that I had cancer.

It was hard doing the rule out. I thought I had to do all these horrible things just to appease the rule out. I was still in the belief that all these other doctors telling me, “Look, your blood work’s perfect. I’m sure you’re fine.” I had so many doctors tell me that, from the dermatologist to the immunologist allergist, my primary care.

So many people were like, “I’m sure it’s probably just something immune, autoimmune.” In my mind, I just think, “Oh my God, I have to do these 2 horrible tests to help figure this out, but I do not think I have cancer.” That wasn’t what I was thinking at all.

When she said it, it couldn’t have been more of a shock. I was completely in shock. There wasn’t a lot of conversation. After that, it was just 1 or 2 questions. Her responses were like, “I’m not a lymphoma doctor. You have to call the Lymphoma Center.”

I got information that I had cancer, but then I didn’t really have anybody to ask follow-up questions. There’s a lot of B-cell cancers.

My friend who was a doctor, I called him. He’s such a great friend. He came over immediately within an hour, and we were able to talk, like, “Well, there’s some ones that aren’t that bad.”

We were going through the list. He was trying to talk me down a little bit. When I called the Lymphoma Center, they said, “We’re not seeing you until you have a lymph node removed. We’re going to need one in order to diagnose this formally.”

That period was 4.5 to 5 weeks from, “You have cancer,” to “What is this?” I had to find a surgeon, schedule an appointment with a surgeon to meet before surgery, then schedule a surgery. Then it goes out to a lab. They couldn’t have told me more times, “It literally takes a week. It takes 5 full days. It’s not going to come back any sooner. We assure you, 5 days is the earliest.” Then from there, then I have to get an appointment with the doctor to get the results.

It was a good 4.5 to 5 weeks of just complete anxiety. Those were definitely the worst weeks. The not knowing what my outlook is, what my prognosis is, what is going to happen in terms of treatment. Those were the worst.

The terrible part of it was the anxiety part that you sort of hinted at it when you’re waiting to get the scan results. That’s what made it so terrible.

The meeting with the surgeon and the appointments — all of that wasn’t a bad experience. I felt like I navigated it as fast as I could within the system. You call to make a prelim appointment with a surgeon on a Monday, and you get in on the next available — might be Thursday. You meet Thursday.

Then you got to get on the surgery calendar, which could be 1 day or 2 days a week because they’re meeting with so many people for pre-op and post-op. The surgeon just might schedule surgeries 1 day a week or 2 days max.

I understand the idea of just checking to the emergency room, but how much faster could it have been? I don’t know if that would set it up for me.

Describe the moment you got the results

The worst day was getting a phone call from the hematologist saying, “You have some B-cell cancer. I don’t know what it is.”

That was the worst day. I was crying and thinking, ‘This is it.’

Going in to get the formal diagnosis and meeting my doctor for the first time was a very long visit. I brought 2 friends with me. One of them was the doctor, which I’m very grateful for. We were there for a good 3 hours, and I had a ton of questions, collected over the 3 or 4 weeks that I was waiting.

My doctor, who’s at Weill Cornell, Dr. (Jia) Ruan said, “You have mantle cell lymphoma.” She explained it, and I immediately felt very lucky because the hematologist had referred me to the Lymphoma Center at Weill Cornell, and there’s a handful of doctors there.

The one that I just randomly ended up being assigned to happens to be the one specializing in mantle cell lymphoma. That was like a miracle in a way, because of the options there. I didn’t really pick. They just referred me to somebody. I just accepted the referral. That seemed magical. I got the exact right doctor that I should be seeing.

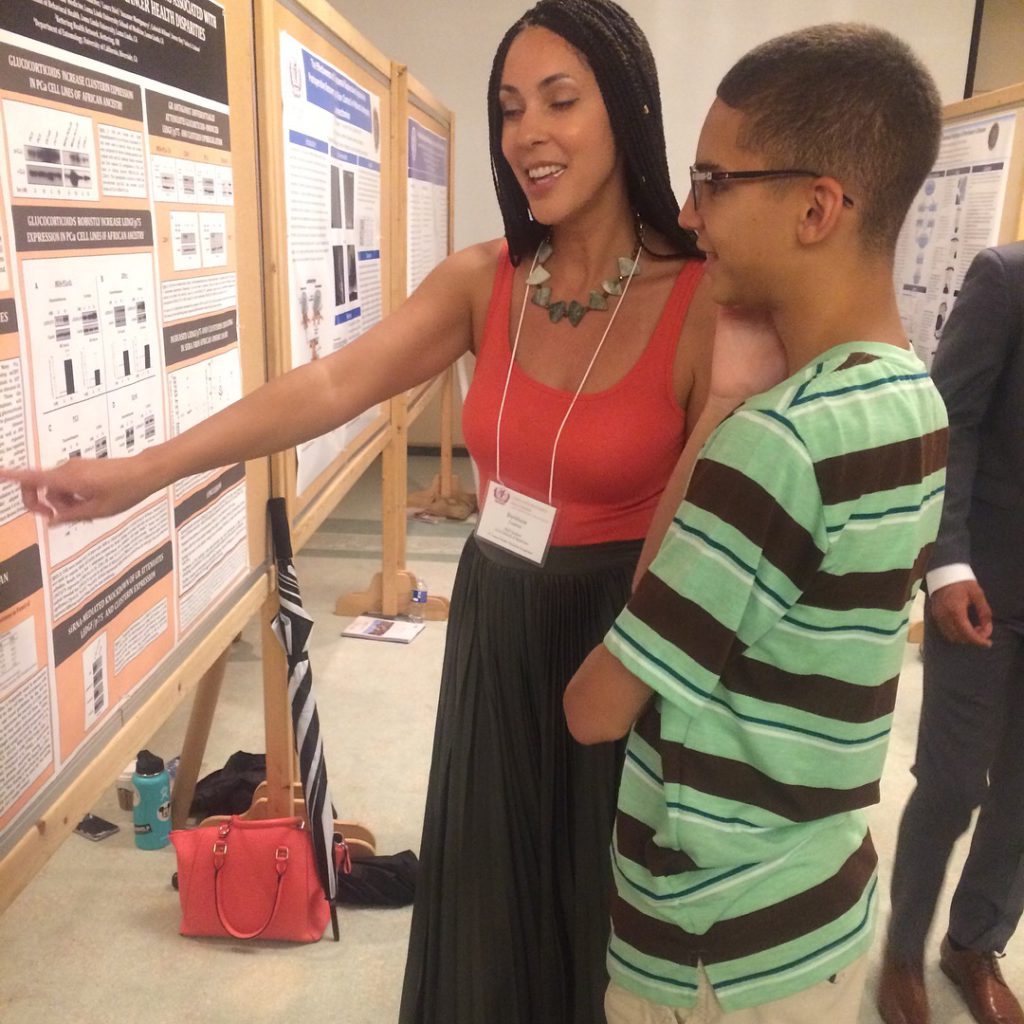

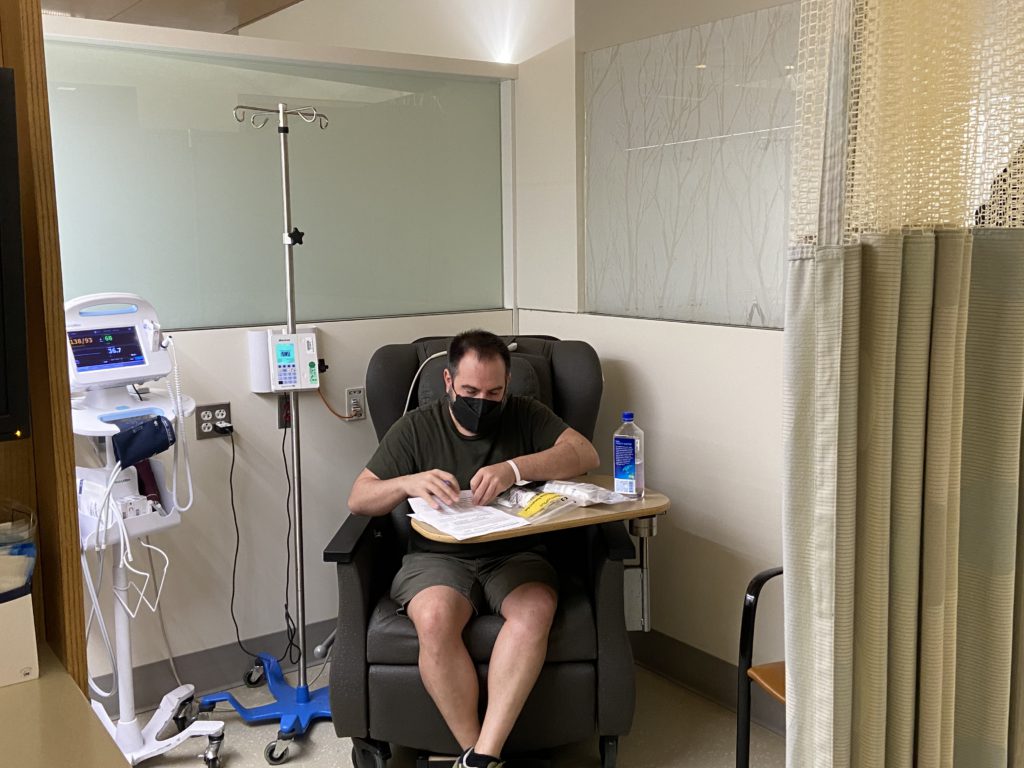

VIDEO: Treatment & Clinical Trial Experience

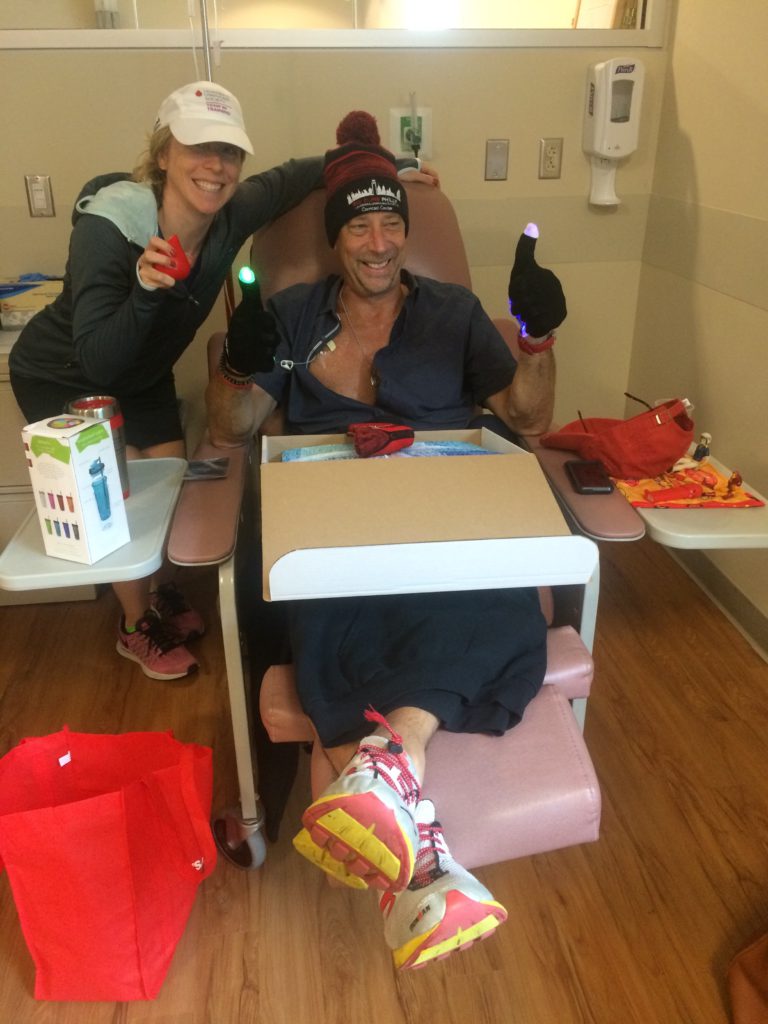

Jason used to be afraid of needles and procedures. Watching his mom go through breast cancer treatment through chemo, he was determined to try a different course of treatment.

Luckily, Jason got into a clinical trial introduced to him by his oncologist that turned out to be effective for him.

Treatment decision

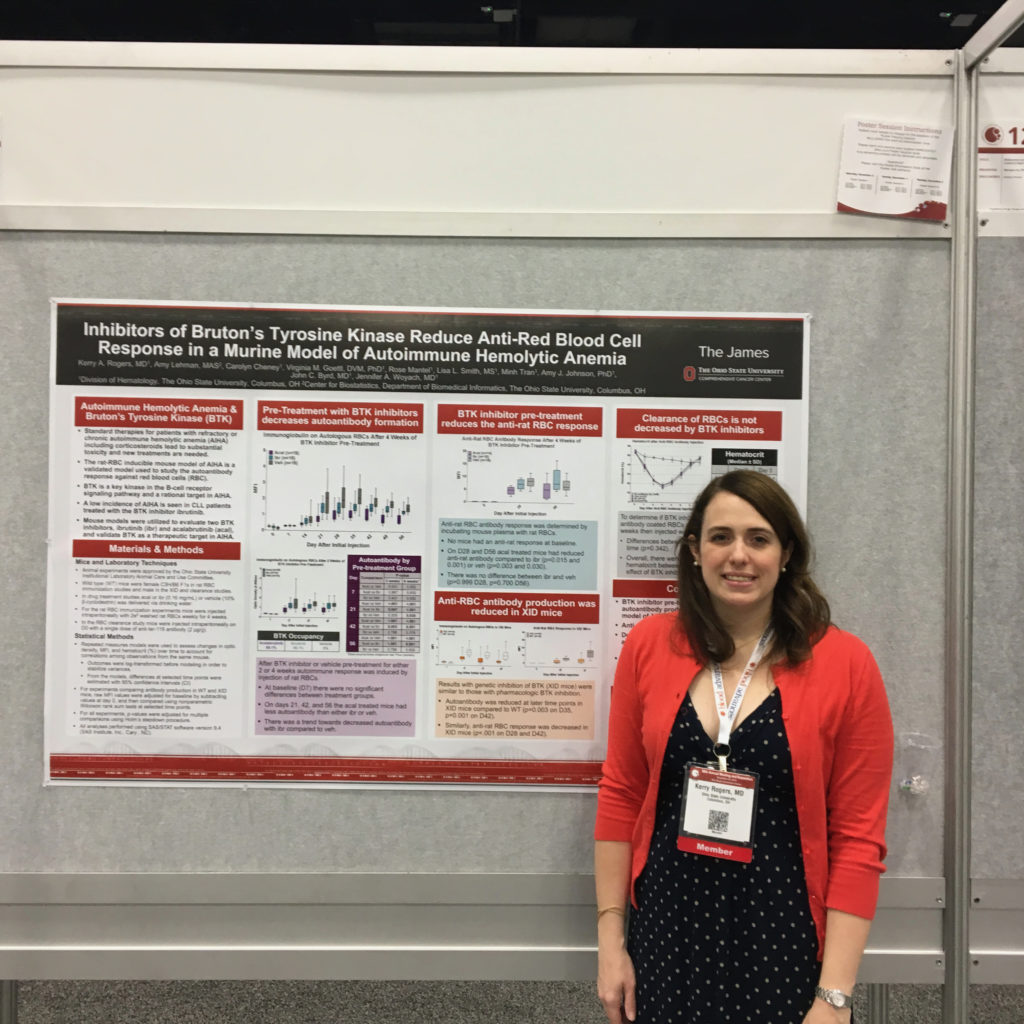

My doctor said the traditional path to treat mantle cell lymphoma would include R-CHOP chemotherapy and then, depending on the result, could potentially be followed with a stem cell transplant. She said that she had another option for me, which was a clinical trial that she happened to be heading up for mantle cell lymphoma.

This felt very magical to me. I landed with this doctor who specializes in it, and now she’s also heading up a Phase 2 clinical trial.

She had presented both options. I knew instantly I wasn’t going to do the R-CHOP chemotherapy, because I told you I wasn’t going to do what I saw my mom did at that moment.

My friend who was a doctor was there with me. We asked a lot of questions. He asked a lot of questions as well about the clinical trial. She left the room, and I turned to him and said, “What do you think?” I just wanted his opinion. But in my mind, I already knew I was not doing that R-CHOP stuff.

He said, “I think you should do the traditional route. There’s just more data. They’ve been using it more. We know it works.”

I said, “I think I’m going to go the other way.”

She came back in, and I asked a lot more questions. They presented me with a stack of papers, like a contract. I read through it all.

I sat there for like another hour, just contemplating which one to do. Then before I left, I signed all the paperwork for the clinical trial. She said, “All right, come back in a week from today, and you start.”

So that’s how I started.

Describe the cycles

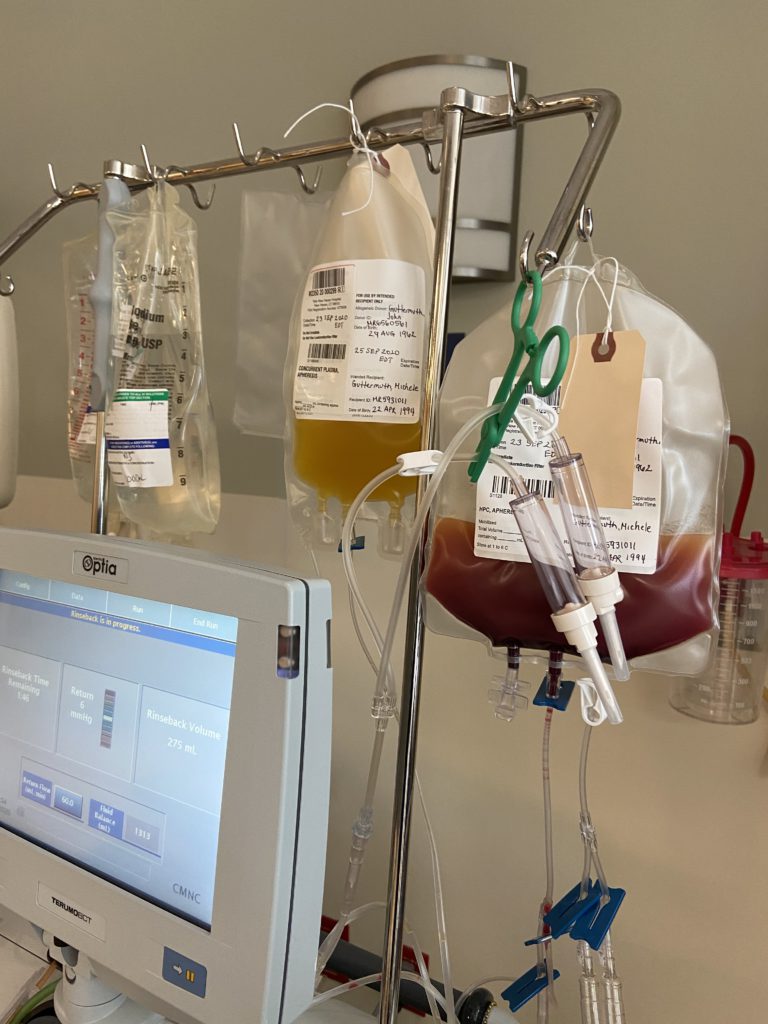

For the first 4 weeks, you get Rituxan every week, and then after those first 4 weeks, you will get it every 56 days after that. The other 2 medications are both oral, but the Rituxan is infused. You go to the hospital, to an infusion center, and do that.

The first 4 weeks were back to back, 4 weeks in a row. Ever since then, I just go in every 56 days. I take acalabrutinib every morning and every night, every single day, and I have for over 2 years now.

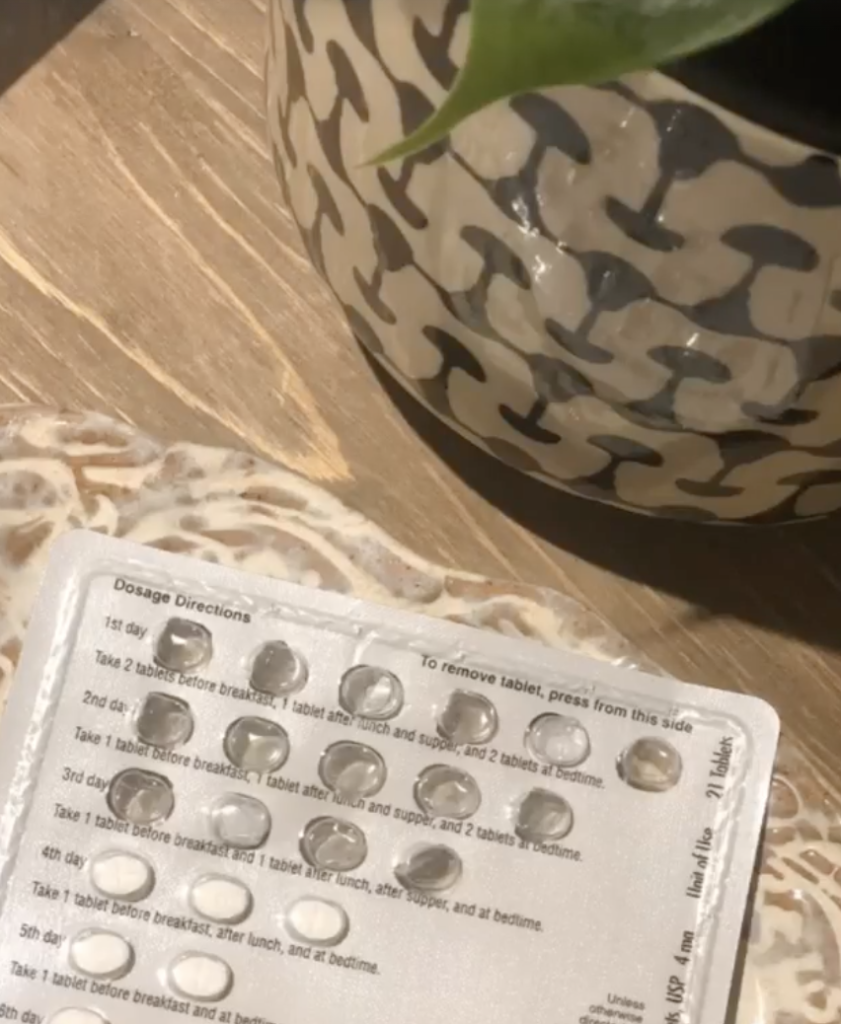

For the lenalidomide, I take it like birth control. 21 days on, 7 days rest. I’ve been doing that for over 2 years now as well. The first year, I took 20 milligrams of lenalidomide, and then for the second year, they let me reduce the dose to 15 milligrams. Basically a 25% reduction of that drug to give a little break and hopefully reduce the side effects by 25%.

Describe the difference in side effects

It’s so hard to measure them. But I do remember that the first year was way harder.

I remember in the beginning — the first 6 months — were way harder, and I don’t know if that’s you just get used to it, or your body gets used to it, or you adapt. I do remember that the side effects were worse in the beginning, and maybe it has to do with just managing it better now.

I can tell you that acalabrutinib causes headaches for me personally. It just straight up causes headaches. They resolve from caffeine; if you get a headache and drink a coffee or take an Excedrin that has caffeine in it, it’s pretty quick. It goes away.

Dr. Ron, who’s been at Phase 2 clinical trial, it was her tip on that, and it worked. If I ever got a headache, sometimes I’d wake up in the morning and just be like, “Oh, my head is killing me.” One cup of coffee, and it would start to fizzle out.

Luckily, I like coffee. I drink black coffee every morning. If I didn’t drink coffee and had to take Excedrin every day, I might feel differently about that.

How long would the coffee last in terms of helping?

I was a 3-cups-of-coffee drinker every morning to begin with before all of this. The headache is every day, but it subsides every single day from caffeine. Normally, if I wake up in the morning with the headache and drink, it goes away.

I normally don’t get a headache, maybe not get one for the rest of the day. If I get one in the afternoon or evening, I can pop an Excedrin; it’s not every day that you get a second round of headaches. It seems like waking up with a headache, as was my experience.

Any other side effects that were really tough?

It’s hard to tell which ones are doing which ones, so these are just my opinions.

I really think Excalibur is causing the headaches. Then with lenalidomide, I feel like it causes a ton of fatigue.

The pills are causing all my fatigue. That’s my number 1 side effect. That’s my biggest problem. It’s like tired, but fatigued isn’t tired, and I want to say weak, and fatigue isn’t weak. It’s like putting those 2 in a blender, and it’s something else let a little light that hits me pretty hard.

If I go to work and I’m moderately active throughout the day, I’ll come home, and that’s it for the day. I’ll be on YouTube in bed for the rest of the evening.

Fatigue is the biggest side effect of lenalidomide.

What does a normal day and fatigue look like?

Even when I was having symptoms with those hives, I was out to dinner. I was meeting friends.

I don’t do that anymore. If I do a workday, that’s it for me. I don’t have anything after work. There is nothing left for me to give.

I had a doctor’s appointment at 2 o’clock yesterday, and the thought of having to get up and go into Manhattan and come back, the level of exhaustion is just like, “I don’t want to do that.”

For people who’ve never been on treatment or cancer or if you’ve ever been so tired where you don’t want to take public transportation, and you just pay for that car, that lift — that’s fatigue.

I can’t deal with getting on a train right now. I can’t deal with getting on a bus right now. I’m so lethargic. I’m paying for a Lyft or an Uber. Maybe that’s a New York City analogy, but that’s how I feel about a lot of things.

Like walking the dog. I just don’t want to do it. I used to play tennis. I used to go meet up with friends all the time after work. I don’t meet up with anybody after work. I don’t play tennis anymore.

The amount of hours I have to dedicate to the day is a lot less. I’m not what I used to be during those hours.

What helped you through the fatigue?

I’m still working on it. I met with an integrative health doctor yesterday. We talked, and the soup of the day was fatigue.

This doctor is at Weill Cornell, a real doctor, a board-certified doctor. We were talking about solutions for it, and one of the things we talked about was potentially doing some weight training and some cardio, even though that sounds totally counterproductive and the exact opposite of what you would want to do if you’re so tired.

We talked about strengthening, building muscle mass and strengthening the heart to potentially alleviate the fatigue a little bit or improve my quality of life. It’s a long process. We talked about starting really small and building up to maybe 150 minutes a week combination, maybe like 5 days a week. Then maybe year 2, punching up to 300 minutes, but in very small increments.

That may be a solution. I’m going to try, but it’s not like, “Boom, that’s fixed.” It’s going to be a path and a journey. I have to do the work to have a little bit better quality of life hopefully. Because for me, my protocol is I’m going to keep doing this therapy for as long as it continues to manage my disease or until I can’t handle it anymore.

Investing in this idea may be worthwhile for me, considering I’m going to keep taking these medications.

What’s the follow-up procedure for monitoring MCL?

I’m incredibly fortunate because the clinical trial was trying to get FDA approval, and there are people that are analyzing data, and there’s research.

I received MRD tests regularly during the clinical trial for the formal 2 years. I got one before I even started and then at different intervals throughout the trial.

From what I understand, even though they aren’t FDA approved for mantle cell lymphoma, the researchers can identify if there are any cancer cells in my blood down to 1 in 2 million or something like that. From what I understand, it’s a very sophisticated science and test.

We know from my last test 3 months ago that there’s still a minimum amount of cancer cells in my blood. But if I wasn’t getting the MRD test and I was just getting R-CHOP or whatever and not on this clinical trial, they’ll just send me to get a PET scan, and they would tell me that I’m in remission. That’s what my doctor said.

She goes, “I can’t say that to you because I have this other test over here that tells me the truth, in a way.” She said, “Let’s call it metabolic remission.”

All of my lymph nodes are now the same. They’ve shrunk down to a size that fits into the normal zone. None of them are like lighting up like a Christmas tree as they used to. From a PET scan point of view, I look good. But from the MRD test, we know that it’s still present.

Again, they use the word “minute.” There’s a very small amount. At the second anniversary, which was last month, they pulled blood for another MRD test. I don’t have those results back because in a clinical trial, they do it in batches. I’m in a batch of a pod of people.

Those results get released once the whole pod completes and finishes. I’m hoping that when that result comes back, I don’t know if it can be better than minute, but I would love to hear complete remission, which would mean there’s nothing.

But again, my doctor says, “Don’t get hung up on the name of complete remission because there really isn’t a cure for mantle cell lymphoma.”

I believe there are some doctors who think they’ve cured some people, but they’ll say, “I don’t know,” until they get another 20 or 30 years down the road and die of something else.

I think it was in the 90s that it was even really discovered. For the first decade and a half, they didn’t even know what to do with it. They didn’t have treatments and therapies that were specific for mantle cell lymphoma. They were just giving what they were giving to another disease until they did their research.

It’s new in terms of medical error. It’s a newer cancer that they’re trying to understand and treat.

How is MRD different?

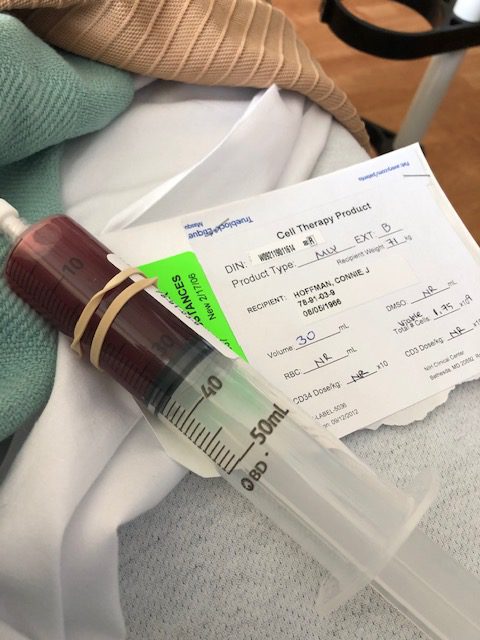

I go in every 28 days for standard blood work because all these pills drop my white blood cell count. Before they give me the next bottle, I have to be at a certain level, or no meds for you. When they do the research tubes, when they’re already taking my blood, there’ll be another pouch with 2 vials that are basically in a special bag. Then those two vials get sent to another specialty lab on them, and it goes to an outside lab outside of my hospital.

That is where the clinical trial is crunching the numbers or whatever they do.

Describe the clinical trial process

It was like a stack of papers this thick, and you’re supposed to sit there and read through the whole thing. It seems like a contract. If you die of a heart attack, you can’t sue us. There’s a lot of stuff like that — 8 pages of potential side effects. “If these happened, sorry, we’re not responsible.”

They outline a lot of the financial things, like your insurance is still going to be billed for Rituxan because that’s standard care. You’d be getting that anyway. It seems very legal.

»MORE: Learn more about the process of clinical trials from one program director

Was there any insurance issue?

No, there weren’t any issues in terms of my insurance with a clinical trial. The way the clinical trial was set up is like they knew what was standard care and what wasn’t.

They know MRD tests and standard care, so they’re footing the bill for that. They know rituximab is standard care, so they tell them, “Bill that through the insurance.”

Anything that was going to be provided for me anyways is getting billed through the insurance. Anything that is above and beyond is being paid for by the clinical trial.

Also, I had a lot of questions about what happens after: “Are you going to kick me to the curb?” I was told no. If this works for me and I complete the 2-year clinical trial, they will continue to give me the medications as long as it’s working for me and my doctor. We, together, decide that.

I finished the clinical trial formally 2 years, and my doctor and I decided together to keep going. The clinical trial has continued to give me these 2 medications, and they’re not billing it through my insurance.

They’re the same process as to how I was getting them before. Because they’re not FDA approved, they come from a specialty pharmacy, especially lenalidomide coming to a mantle cell patient. It comes from a research pharmacy.

They call me, and I have to answer a whole bunch of survey questions. Then I get transferred to somebody else, and I get all these yes and no questions because lenalidomide causes birth defects.

There’s like, “Have you had sex with a female who may become pregnant? Yes or no?” It’s a lot of surveys like that.

You will have to complete a survey every 28 days. They will say your next survey is available on this date. That’s kind of the process, and then you get a shipping confirmation from the pharmacy. They’ll say, “We’ve shipped your pills to your doctor. You will get them on your next visit.” That’s how one comes.

Then the other one, I think, just comes from the pharmacy internally. But it’s grants from the clinical team for these pills to get there. They’re continuing to pay for them for me to continue on, which I appreciate, but they’re also going to be getting more data and more information.

I think they’re just as excited that I’m continuing as I am as excited to continue, which is great. This is the ultimate perfect match, right? It’s working for you, and it’s also information for them that will hopefully help future patients down the road.

They call me. The doctor calls in the prescriptions, the specialty pharmacy, and then calls me. They do a security check to ensure it’s me. They ask a whole bunch of standard questions. They say, “OK, great, we’re going to ship.”

You need to complete your monthly survey, and then I get transferred somewhere else and have to do yes/no questions. Have you donated blood? Have you donated sperm? All of these. I believe it’s because of something to do with the FDA.

I take the survey, and then I show up at the hospital. They take my blood. They send it to a lab right down the hall, and I sit there for about 45 minutes waiting for the results to come back. Then if the white blood cell count and the new drill fill or something like that is good, then they hand me the pills. But I don’t get to leave until I get the blood work back.

What happens when your counts are not good?

I’ve never not gotten my pills. They’ve always been like, “Your counts are good.” I haven’t had that bad news yet, which I feel really fortunate about. My white blood cell count just sits out of 3 like right across the board, like a piece of paper. It’s low, but it’s still right at the bottom of the acceptable mark, but it just stays there.

I don’t know anybody else, any other clinical trials, or any other place where mantle cell patients are receiving lenalidomide, at least not in the U.S. I don’t know. I think this clinical trial is the first to combine lenalidomide and acalabrutinib.

Those of us in the clinical trial are like the guinea pigs for that combination for mantle cell lymphoma. What happens to us is kind of what they’re looking for. Hopefully, nothing bad. I’ve been here for 2 years doing it, and I’m still here.

What’s your response compared to the typical response on the traditional route?

I’ve never asked, “How do I compare to that?” She’s never brought it up to me, but she’s been very excited about the response in general. Like everybody seeing a response, we have people in complete remission on the clinical trial.

“I’m very excited that you responded, and at the level that you responded, I think we should be happy.” She seems to be thrilled with just in general, how everybody’s doing.

I think everybody got a response. There wasn’t one person that it just didn’t work for. I think that there’s some excitement around that. For me, I’m glad I didn’t do the R-CHOP, and I don’t know what’s next for me.

It’s one of these games of chess with mantle cell lymphoma. I’m going to keep doing this for as long as I can do it and manage the disease. Then, we probably all assume at some point this is going to relapse and come back, and then I’ll need to try another therapy.

I think, if that’s the case, I will hold out to do a traditional type of chemotherapy that would be like going into a stem cell transplant or CAR T-cell therapy or something like that.

It’s one of these games of chess with mantle cell lymphoma. I’m going to keep doing this for as long as I can do it and manage the disease.

But to do straight-up R-CHOP or chemo as a treatment is not appealing to me unless we’re going for a home run on this.

We’re going for the stem cell transplant. We’re going to do CAR T-cell therapy.

I’m in a lot of cancer support groups. There’s anxiety between the chemotherapy and going off and scanning again in 3 months and seeing every 6 months. That sounds anxiety-driven.

I love the fact that I go to see the doctor every 28 days and this treatment continues. I feel like I’m doing something by taking the pills every day. When you talk about managing the disease, I feel like a management thing is happening here. If I just did R-CHOP, we feel like, “Let’s whack it. Now you go over here, and we’ll see how long that lasts.”

This process feels a little bit more like we’re staying on top of it.

Long-term care and attention

I know most lymphoma patients are getting PET-CTs, if they’re lucky, every 3 or 6 months. I’ve been getting MRD tests every 3 months. They’re giving me another one in 4 months. Then they said, “If you stay after that, every 6 months,” so twice a year for free for being in a clinical trial. I’m going to have information that they shouldn’t be getting.

MRDs aren’t approved for mantle cell lymphoma, but there’s no insurance company in the world that’s going to just start doling out MRD tests for mantle cell patients.

This feels like I’m really being watched and managed at a level way beyond what is even futuristic. It’s beyond what is even possible if I wasn’t in a clinical trial.

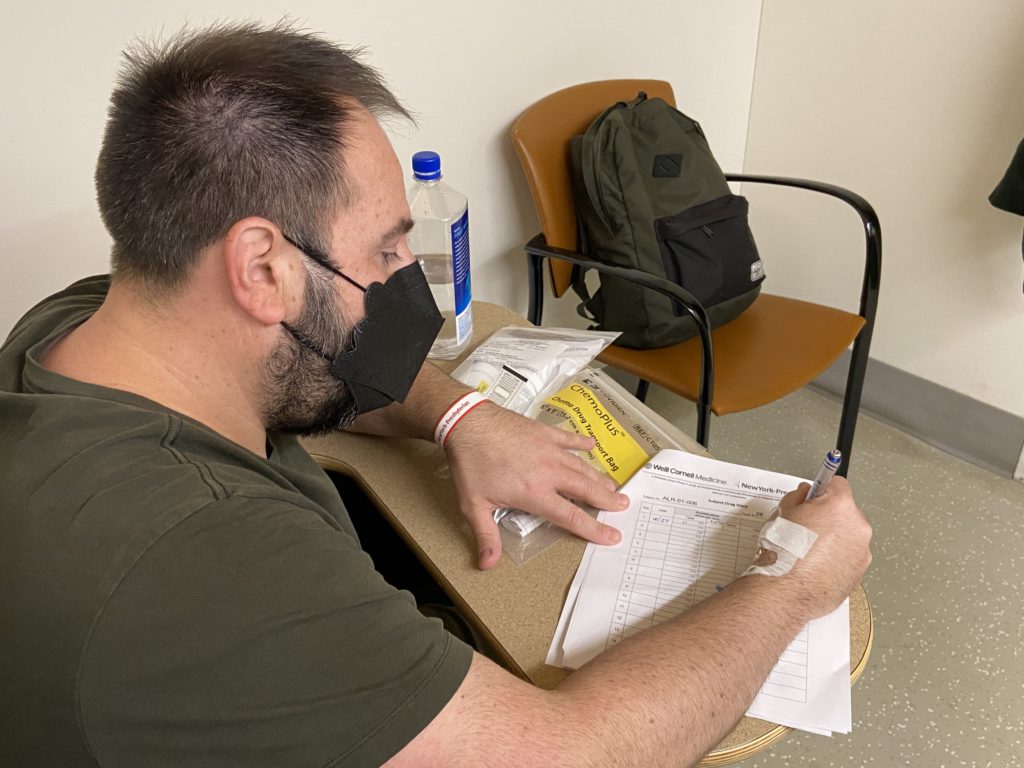

What do you have to do every day?

I can show you one. I have one right here. It basically just says study drug diary. You have to log the date, time and the number of pills you take every single day.

I’m taking acalabrutinib every morning and every night, and then I’m taking lenalidomide, 3 pills every day. Then I take it for 21 days and then 7 days off. Even the diary will remind me, “Do not take on those days.”

It’s very important that I bring all the pill bottles back. They have a freak-out if you don’t. They’ll have to write a report if you lost the bottle or something. In one instance, they know that my cycle is 28 days, so I should have 4 pills left or something like that. They’re opening it up, making sure that there are 4 pills in there that I bring back.

If it isn’t there, they’ll ask, “Where are they? Did you miss any doses?” Randomly, every other time or every 3 months, they’ll give me a whole bunch of questionnaires.

The questions are like on a scale from 1 to 5 — do you feel close to your family, etc. Then you meet with a clinical trial nurse every time, and you report every single symptom that happened during the 28 days and make notes next to the date, like, “I had diarrhea on that day. I had a really bad headache. I had chemo brain on that day or whatever.” Whatever side effect you had.

»MORE: Read more on FDA approvals of clinical trials

Every 28 days, you turn over all the side effects of what you did. That’s pretty much it for paperwork. It’s the drug diary.

I thought there were 28 people all starting at the same time, and I thought that I got into the second-to-the-last spot, but it turned out I got the second-to-last spot of Pod 2. I guess when I started 2 years ago, they only started 12 people for the first year.

We were like the guinea pigs, and then after about 11 months, they started more pods. But the goal is 28 people roughly for this clinical trial.

I believe there is now a waiting list. It’s sort of caught attention, and there are people that want to join. I’ve heard that there’s even a hospital in Florida that is asking to potentially start offering the clinical trial at their hospital and then enrolling more people.

I think eventually, as it goes down the road, maybe they’ll enroll even more people in Phase 3, like 100 or 200 people across the country. But right now, it’s just at Cornell in New York City.

VIDEO: Life After Cancer (Quality of Life)

For more than 2 years now, Jason diligently writes in his clinical trial journal every single day. Staying on his course of treatment outside of the formal trial gives him hope of full remission from mantle cell lymphoma.

Jason’s story is also an inspiring example of patient self-advocacy — making informed decisions for a better quality of life.

What has been the impact to your life?

I’m really grateful that I have this option. It’s been 2 years, and it feels like it was the right decision for me. Maybe it was not a good idea to make decisions based on those emotions, but it turned out this was the best choice for me. Those were things I probably should have worked through with a therapist, or whatever, those feelings and emotions about cancer treatment.

Regardless, I can look back now and say I still made the right choice. This was the right choice for me. I was the type of person before, like I said, when I went to that PET scan, that was the first time I got an IV. I didn’t really like needles. I was like the person who’s closing their eyes when you get a flu shot.

I’m such a different person now. I can literally watch them put an IV in now.

I’m really grateful that I have this option. It’s been 2 years, and it feels like it was the right decision for me. Maybe it was not a good idea to make decisions based on those emotions, but it turned out this was the best choice for me.

I’ve had so many IVs. I’ve given so much blood, even to the point where I shock myself. I will volunteer to give my blood for things, and I’m the type of person before who would be scared to get a flu shot.

I’ve surprised myself with my self-evolution with all of this stuff. I really didn’t like doctors and going to the hospitals. I just had a lot of bad memories. I’ve been to an infusion center with my mom in the 90s. I’ve shocked myself with what I was willing to do.

When I get Rituxan infusions, I feel really good about it. Even though I’m in an infusion center, I’m like, “This is a good drug; this is helping me.” So I feel really good about that.

I’ve surprised myself with my self-evolution with all of this stuff. I really didn’t like doctors and going to the hospitals. I just had a lot of bad memories.

Dealing with the logistics of follow-up treatment

There’s pros and cons in both.

For the first 4 weeks, I was there every week, and then I went back every 28 days for the blood work, to meet with the clinical trial nurse, to get the medication and then every other business.

With the clinical trial, it’s very rigid. I know my schedule a year out. I know every 28 days on a Wednesday, I have to be there.

During the clinical trial, you can’t really say, “Oh, I’m going to Hawaii. Can we push this a week?” It’s normally a no. There’s a little bit of grace, like 1 or 2 days, maybe here and there and make a special exception. But then it changes the whole schedule. If you change 2 days, then your whole year changes. It’s that serious.

There’s pros and cons, I guess, to everything. I see what you were saying, but with a clinical trial, there’s just a lot of accountability and many appointments. It’s not like I go to Walgreens and get these pills. They’re just not approved for the frontline treatment. I have to pass all these tests to get them. I have to fill out paperwork, turn in diaries.

There’s pros and cons, I guess, to everything. I see what you were saying, but with a clinical trial, there’s just a lot of accountability and many appointments.

Do you have any guidance for MCL patients?

I wish I did have good guidance, because I’m in support groups.

In support groups, I’ve heard horror stories, especially of Phase 1 clinical trials. I feel very fortunate and grateful, and maybe I got some dumb luck, hopefully, getting into this clinical trial because it seems to be working. It seems I can only speak to mantle cell lymphoma because that’s what I have, and that’s what I’ve been researching, and that’s what I’m doing.

Mantle cell lymphoma is a newer cancer, historically speaking, and they’re just in the past 10 years starting to create individual therapies designed just for mantle cell. It doesn’t really get a lot of attention because it is the rarest of all the B-cell cancers. It’s the least amount of diagnoses per year when you’re talking non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma.

I think clinical trials may be worthwhile looking at if you have mantle cell, because that’s where a lot of new stuff is happening. For a long time, you were just getting a lot of the old stuff or repurposed stuff. It almost felt like you were like the youngest child and getting all the used [stuff] — just give them what we gave all the other B-cell cancers.

I think it might be worthwhile if you have mantle cell lymphoma and you’re looking around and trying to figure out your options. Right now, if I was diagnosed, I’d be seeing if I could get into a CAR T-cell therapy clinical trial for mantle cell.

I listen to a lot of cancer care calls and listen to a lot of doctors talk about the stuff that’s happening with that. It just seems like there’s a lot of new modern therapies that are actually being created or tested and designed for mantle cell. They’re not FDA approved.

The only way you’re going to get a shot at getting them is a clinical trial. Do your research, do your due diligence, and follow your intuition.

I feel like I got really lucky. That helped. I showed up at the right place at the right time. That’s just luck, like I go to Las Vegas and I hit the button on the slot machine. That’s just luck, but luck happens. Then the rest of it is just doing research and following your intuition and making an informed decision.

Do your research, do your due diligence, and follow your intuition.

Guidance on PET scans and insurance

I ask a lot of questions, and I’ve learned a lot. I feel like the health care team around me tells me the truth.

I’ve learned that lymphoma patients are not getting an MRD test like I am. You should be getting PET-CTs for lymphoma patients. If anybody doesn’t say it’s a PET-CT, I think that they’re lying because I’ve asked everybody.

If you have lymphoma, PET-CT is really what we want, but insurance companies don’t pay for those for everybody. I’ve heard Medicare gives you 3 or entire life period, full stop. A lot of the rules are designed around cancer patients having one PET-CT per year.

Still, it’s just like this across the board. It would be really great if we could get some advocacy, maybe from LSS or somebody to really advocate for lymphoma patients in particular, that they should be entitled to PET-CT scans.

It may not be as important if you have breast cancer, as my mom had, or some other type of cancer, but it is for cancer that affects the lymphatic system and the lymph nodes. It shouldn’t be a fight for lymphoma patients to get the appropriate tests, which is a PET-CT.

I understand why the insurance companies do it, but I think there should be some advocacy just for that particular thing, which is something that I learned on this journey that lymphoma patients should get PET-CTs.

Advocating for yourself

I made a mistake with my insurance company when I left. My primary care was at Weill Cornell. And when I was looking for the specialist, I went into my insurance book and found somebody who took my insurance that was in the area. That was a mistake because I didn’t ask the right questions.

I learned later that she wasn’t board certified, and I learned how important that is. I learned that all the Weill Cornell doctors have to be board certified or lose their job. That’s great. When I leave there, I’m always asking now, “Are you board certified? Are you up to date?”

The last time they were board certified in oncology was 1997. That’s what you’re getting. I really think I had a bad experience there because I picked a doctor who didn’t continue education and wasn’t board certified. I don’t think she liked me much either.

The other day, I think she thought I was a little bit mental because I ask a lot of questions, which some doctors don’t like. She went as far as to try and prescribe me mental health medication during the diagnosis period because she thought I had anxiety that wasn’t in line with reality.

Then 4 or 5 weeks later, I was diagnosed with cancer. She was way wrong. She did call me on the phone when she heard. I give her credit for calling, but the message that she delivered was a little bit defensive. I think she felt bad that she was so way off, but I think she was way off because she just wasn’t a good doctor. I don’t think she was a good doctor for trying to push me into mental health medications and be dismissive of my symptoms.

Message to others going through cancer

I doubt there’s a mantle cell support group. There are like 2,000 cases a year. I’d be shocked to see that.

The closest I found is blood cancer support groups in general, but big shout out to support groups. It’s really great because here’s the reality. In the beginning, with a blood cancer like mine, at a minimum it’s going to be like 5 years.

If I did nothing, I’d probably die in 5 years. Chances are I’m going to have to do multiple therapies. It’s going to be an ongoing process. It’s going to get dragged out for probably, let’s say, a decade, hopefully way more. That’s a long time of your friends and family not wanting to hear about what you’re going through.

My friends and family were kind of concerned for the first 4 months or whatever, and they would check in or whatever. Right around the 6-month mark, everybody’s like, “OK. He’s not dying tomorrow or next week or next month.” The support groups are great places where you can hold, just be there and listen to other people, and also you can be heard yourself.

My family or my friends never had a bone marrow biopsy. They’ve never had a PET-CT. You’re talking to the wrong people, so support groups are a great outlet — and especially if you have blood cancer, typically the journey’s longer.

If you find a regular group that meets every single Monday or whatever it’s going to be, it’s like you are seeing the same people over and over again. I think that’s something great about support groups.

The one that I started in person pre-COVID (and now it’s on Zoom), it’s the same people that have been there, for the most part, for 2.5 years now. You kind of see people go up and down, and that’s also helpful to you.

You can also bounce things off other people. We talk a lot about doctors and second opinions and managing. We were just talking about that other doctor.

I’ve seen people in my support group dump their oncologists and pick another one just because they’re in the support group talking about it and everybody saying, “I can’t believe they talk to you that way. You need to get rid of that person.” It’s like you go to school. Not all teachers are the same, and not all doctors are the same. There’s like 6.5 billion, 7 billion people in the world, and we’re not all going to get along.

Sometimes a support group will help you figure out where you need to be or where you need to go and get you information.

The other thing I do is yoga. I do gentle yoga once or twice a week. I used to do pilates before that. It’s not serious activity. I’m not running or doing all this cardio, but it’s a nice reset outlet if you can find access to it.

Just have 1 or 2 things a week that you can do, and it doesn’t even have to be yoga. It can just be like a massage. If you can come up with a couple of things that you like to do each week and have that on your calendar.

I always try to have something fun to do to look forward to, whether it’s a weekend getaway or planning something with a friend. I feel like my work really has given me purpose and reason to live.

»MORE: Read other patient experiences on yoga and meditation

Prior to starting a company, I was a freelancer working for other people, representing other companies. Now, luckily, I have my own business, and I’m an entrepreneur having a passion for something. For me, it’s my business; for you, it could be anything.

Having that passion for my business and my company really gives me a reason to live. It’s like there are employees there. We have wonderful customers. We’re building something. We’re growing something. Having something to do that you’re passionate about is ultimately the most important.

Inspired by Jason's story?

Share your story, too!

Mantle Cell Lymphoma Stories

Cherylinn N., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptom: None

Treatments: R-CHOP chemotherapy, rituximab

Stephanie R., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Elevated white blood cell count

Treatments: 6 months of rituximab + ibrutinib, 4 cycles of hyper-CVAD chemotherapy

Jason W., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Hives, inflamed arms

Treatments: Calabrutinib, Lenalidomide, Rituxan

Bobby J., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Fatigue, enlarged lymph nodes

Treatments: Clinical trial of ibrutinib + rituximab, consolidated chemo of 4 cycles of Hyper-CVAD