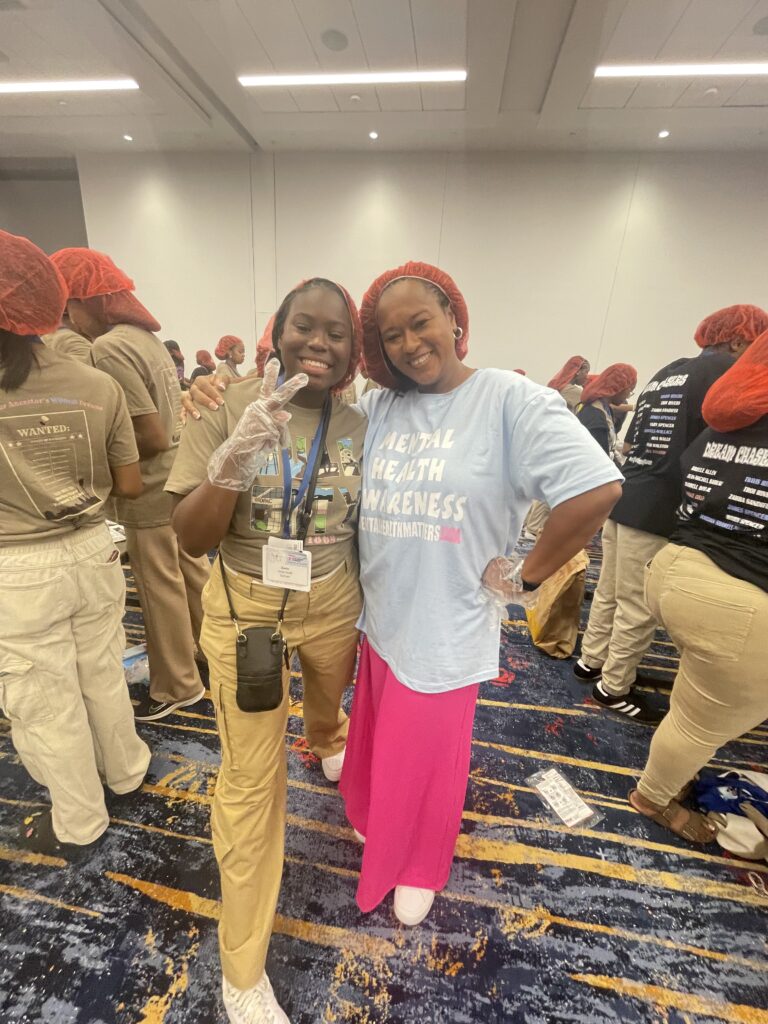

Supporting Someone with Cancer: Karina & Jesse’s Myelofibrosis Care Partner Story

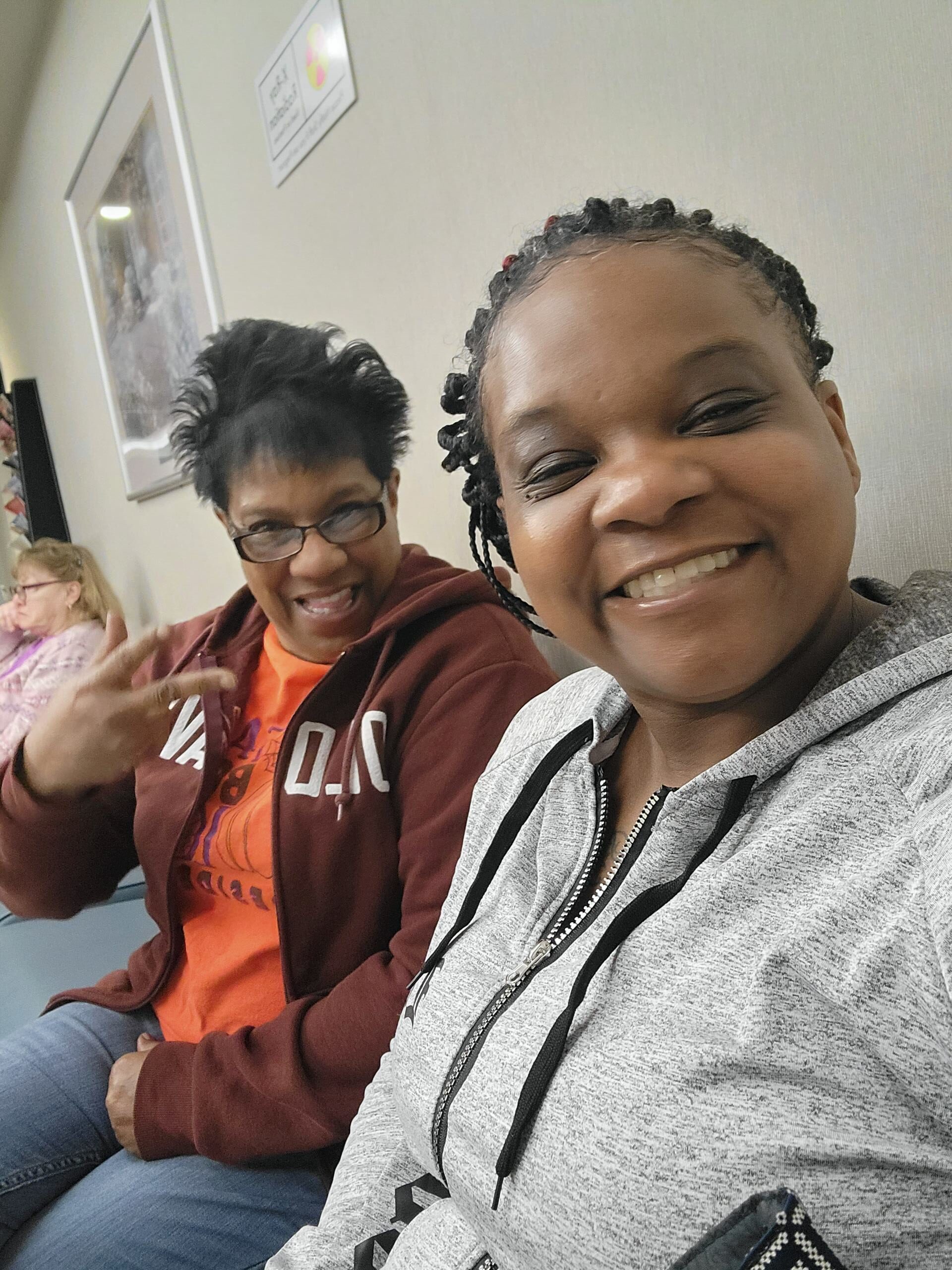

When Karina was diagnosed with myelofibrosis during pregnancy, her husband became her anchor, learning how to support someone with cancer. This is their story of how he navigated the uncertainty, advocated for her care, and found strength in the face of the unknown. Together, they faced each new challenge, showing the vital role care partners play in the cancer journey.

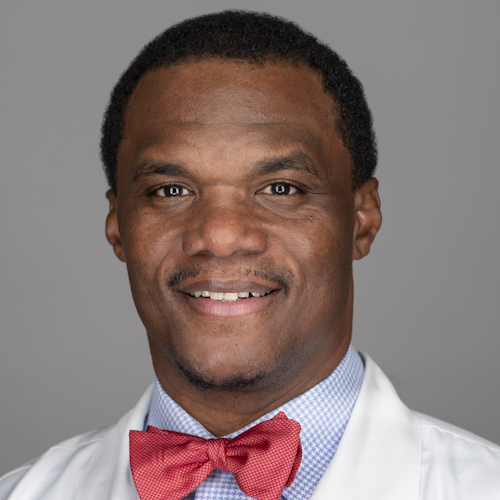

Interviewed by: Taylor Scheib

Edited by: Chris Sanchez

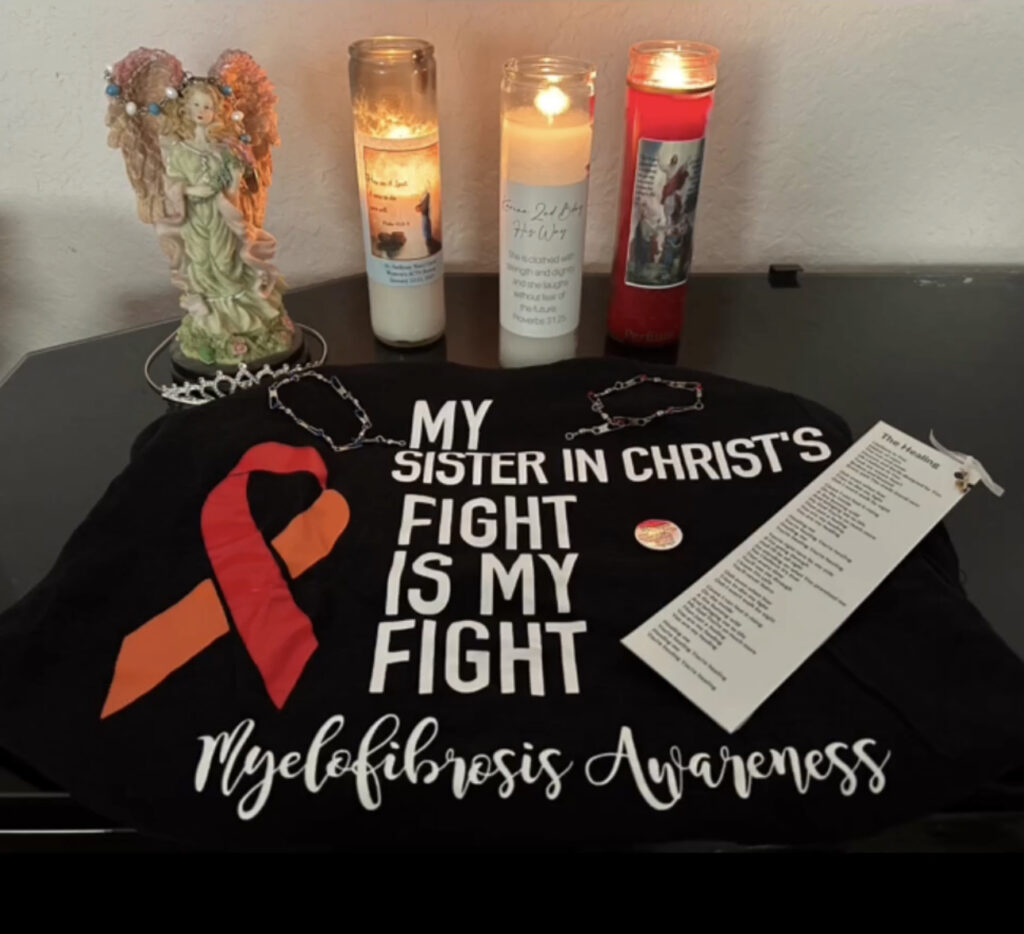

Karina’s symptoms included excruciating abdominal pain, fatigue, anemia, and neuropathy. But she was determined to get on with her life. She balanced her health challenges with pursuing a nursing career, caring for her family, and maintaining a positive outlook thanks to her spirituality. Jesse’s role as her myelofibrosis care partner was crucial. He didn’t just provide emotional support, but also became her advocate, researcher, and biggest cheerleader.

As Karina’s condition progressed, it became evident that she needed to have a stem cell transplant. She and Jesse struggled to find a match until their son, David, turned out to be her perfect donor. When they discovered this, they were filled with profound gratitude and hope.

Post-transplant life brought its own set of challenges. Accepting the new version of herself wasn’t easy for Karina, but her strength lay in accepting change with grace. Together, Karina and Jesse advocate for the power of mindset in dealing with life’s toughest hurdles, the importance of supportive care partnerships, and the urgent need for minority representation in stem cell donor registries.

Read Karina and Jesse’s story and watch the video for more on:

- How her faith helped turn her cancer diagnosis into a story of hope.

- The life-saving hero who was living under Karina’s roof all along.

- How Jesse’s role as Karina’s myelofibrosis care partner redefined love and support.

- Why increasing diversity in bone marrow registries can save more lives — Karina’s heartfelt plea.

- Her courageous acceptance of change after her transplant.

- Name:

- Karina H.

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 34

- Diagnosis:

- Myelofibrosis (MF)

- Mutation:

- Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) gene

- Symptoms:

- Severe abdominal pain in left quadrant

- Abnormal blood work

- Treatments:

- Chemotherapy

- Stem cell transplant

Thank you to Karyopharm Therapeutics for supporting our patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make treatment decisions.

- About Us

- How Our Myelofibrosis Care Partner Story Began

- Karina’s Myelofibrosis Diagnosis and How We Took It

- Karina’s Symptoms Progressed

- How We Took Back Control After the Diagnosis

- Hope Helped Us Build Up to Karina’s Stem Cell Transplant

- Preparing for Karina’s Transplant

- Our Son David Was Karina’s Stem Cell Donor

- Life After Karina’s Transplant

- What We Want Other MPN Patients to Know

- Our Advice for Other Caregivers and Care Partners

I underwent a lot of sadness, hardship, and difficulty, and all that entails. But I pressed forward in hope for sure.

There was a lot of hope that just kept me going all those years.

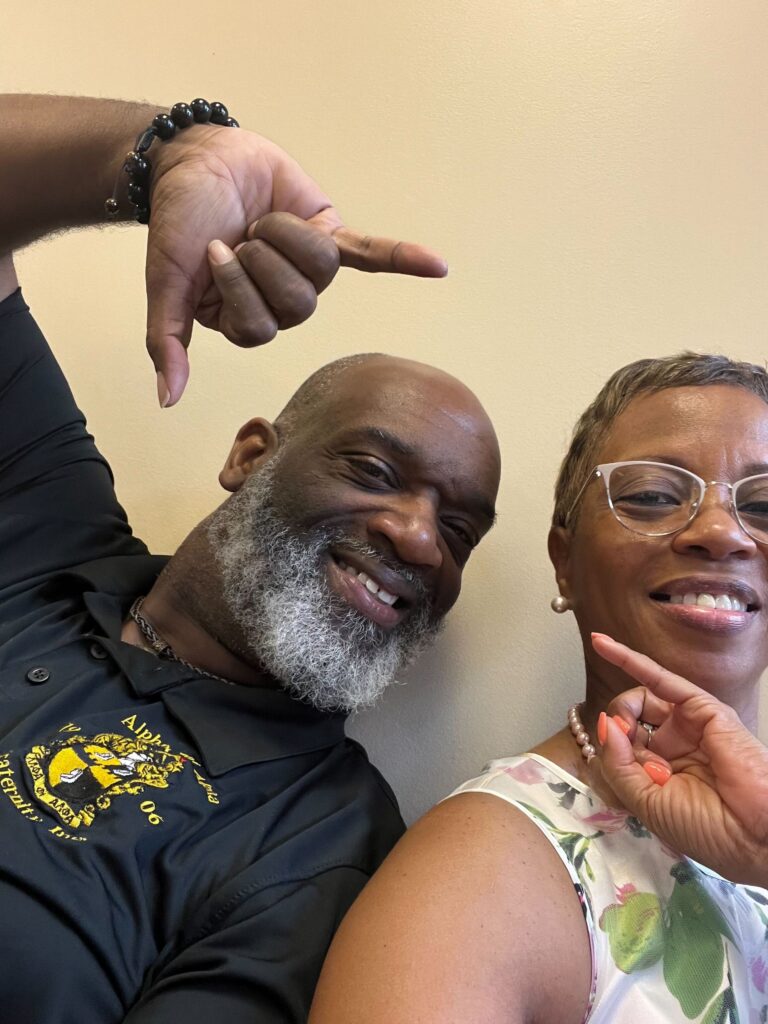

About Us

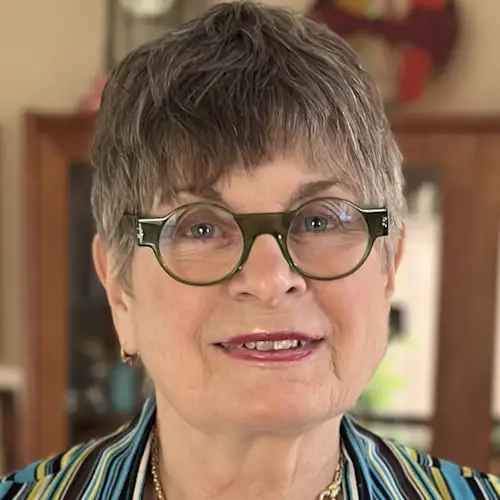

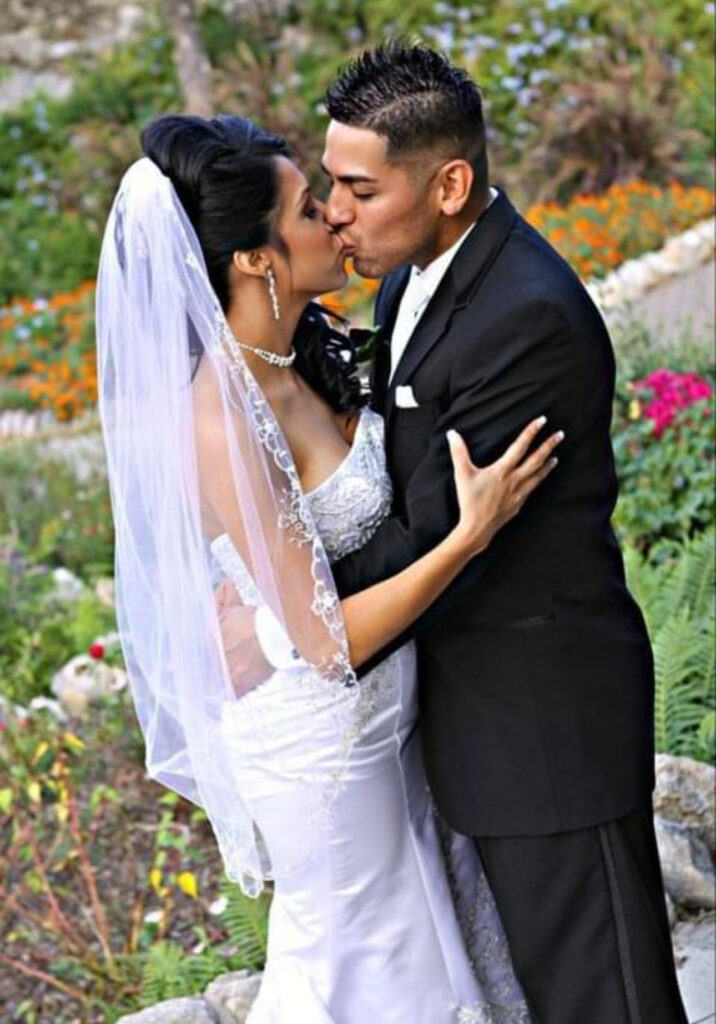

Karina: Hi, I’m Karina. My friends and family describe me as very constant. I’m very faithful, very devout, and also very resilient. I’ve always been able to rise above what I’ve been facing.

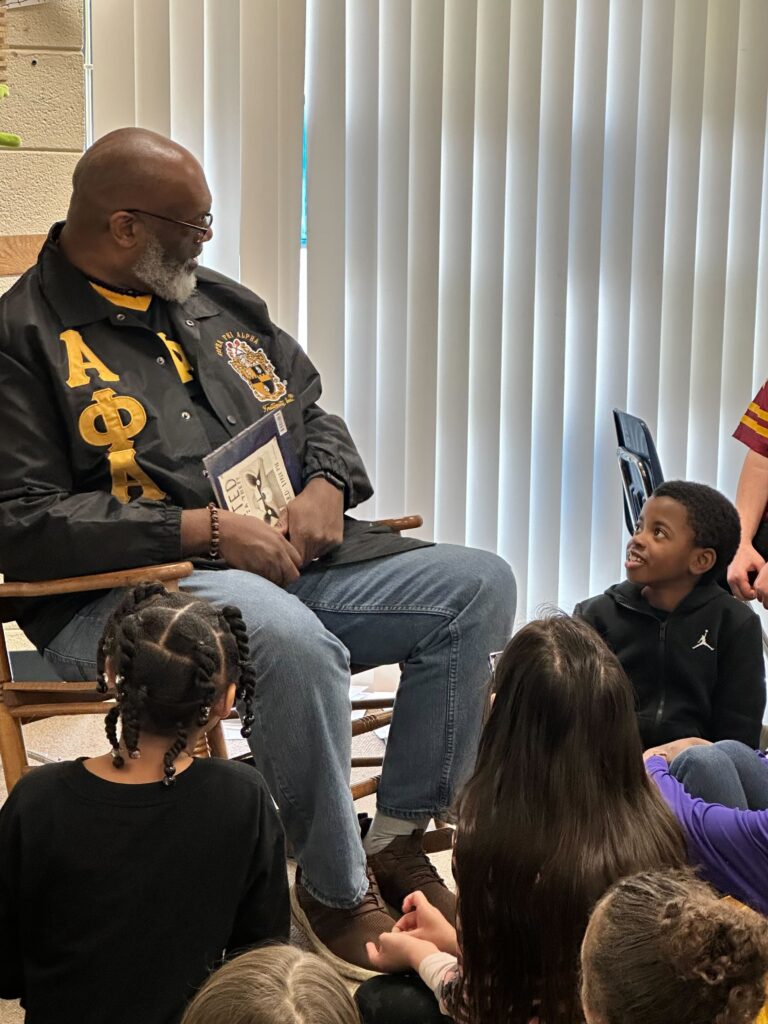

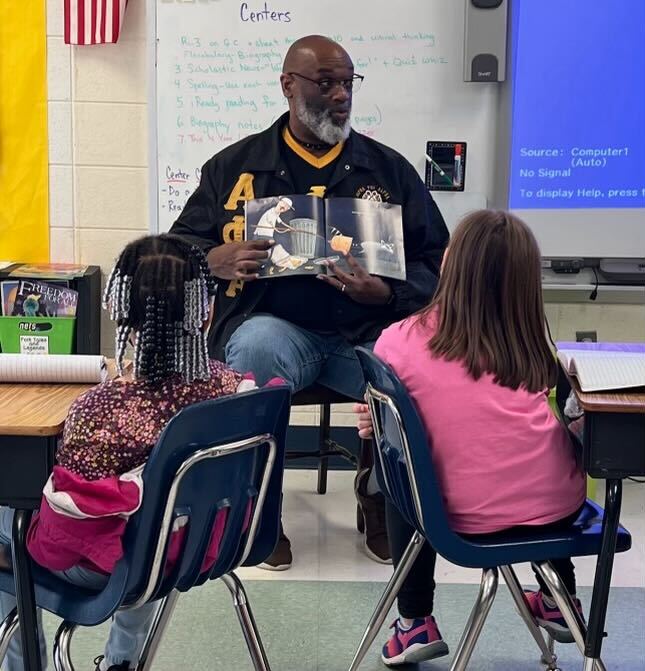

Jesse: Hey, I’m Jesse. Most people would describe me as loyal. If anyone needed anything from me, I would drop everything and help them out. That’s me in a nutshell.

How Our Myelofibrosis Care Partner Story Began

Karina: In December 2016, I had an unexpected miscarriage. I went through the process of losing my child, and then started to move on with my life.

I went back to school. At the time, I was doing clinical rotations as part of the licensed vocational nurse (LVN) program. In April, I was on one rotation. I suddenly started having an excruciating left upper quadrant abdominal pain that wouldn’t go away.

The pain kept me up that night. It felt like I had a bowling ball inside my abdomen. I had to go to urgent care, where they did my bloodwork. They determined that my bloodwork was abnormal, alarmingly so — but they also found that I was pregnant again.

They told me, “These aren’t good numbers. We need to do a bone marrow biopsy right away.” But they also said, “We don’t know if you’re going to be able to carry this baby.”

I asked the doctor, “Are you sure we can’t wait until I have the baby? Is there anything else that we can do?” And he said, “No, this needs to happen immediately.” When I heard that, it was like I went into a fog.

Jesse: The baby was our biggest concern. Karina had miscarried some months before, as she mentioned. And of course, never in a thousand years did we think that she was going to get diagnosed with something as serious as this.

They told me, “These aren’t good numbers. We need to do a bone marrow biopsy right away.”

But they also said, “We don’t know if you’re going to be able to carry this baby.”

Karina’s Myelofibrosis Diagnosis and How We Took It

Jesse: The first doctor went straight to the point. She told Karina, “I’m not going to sugarcoat this. You’ve got myelofibrosis. It’s a rare kind of cancer. You’ve got ten years to live.”

The second doctor, though, went, “Whoa, we don’t know if it’s ten just yet. It might be, considering your age and where you are right now in its progression.”

But it didn’t matter at that point. I think I spaced out when the first doctor mentioned ten years. I don’t think we got anything out of the rest of the conversation.

We left the hospital without saying a word, and when we got back to our car, we just looked at each other and started bawling. And then we went, “Oh, we have so many questions about the baby and the cancer.”

Karina: I really couldn’t believe what the doctors were telling us. I mean, it was definitive, we knew that — I did have a bone marrow biopsy after all. But like in the movies where things go radio silent, after I heard the diagnosis, I couldn’t process things any longer.

I was hearing about donors and transplants and being told, “We’re just going to have to see how this pregnancy goes,” but it was all in little bits and pieces. I couldn’t gather myself.

Karina’s Symptoms Progressed

Karina: We found that the majority of the pain I was experiencing was because of my spleen. It would put tremendous pressure on my left and touch off persistent pain that would radiate to my back and shoulder. Because of it, I had to sleep on my right side for years.

I also discovered that I was anemic and began to feel significant fatigue. So I needed to undergo blood transfusions. And then, of course, the mental impact of discovering my pregnancy and being diagnosed with cancer amplified my fatigue.

I also began to experience neuropathy. I suffered from a burning feeling in my fingers and toes. It felt like someone had taken a torch to them. I remember being in a store and having to step outside it and remove my shoes because I thought I might have ants in them that were biting me.

Jesse looked up and researched all these things I was experiencing. He told me, “We’re going to get a second opinion at MD Anderson in Houston.”

Jesse: As a husband, I got into this fight-or-flight mode. I thought, “I don’t want to lose her. What do I do, what can I do? I’m not a doctor, I don’t know what we’re dealing with, and neither does she.” So we needed to educate ourselves.

The one thing that we kept hearing over and over was “We know what myelofibrosis is, but we’ve never dealt with a pregnant myelofibrosis patient.” Hearing that from a doctor didn’t sit well with me.

Karina: The doctors orchestrated my plan of care. I ended up having a local doctor, but at the same time, I also had someone in Houston who monitored my care.

Jesse: In Houston, they told us, “You’re going to be able to have the baby,” which was wonderful to hear. They said, “We’re going to enter a watch and wait phase,” meaning they would closely monitor Karina without treatment until any symptoms arise.

They added, “You’ll be able to nurse the baby, too. Once symptoms start manifesting themselves and we’re ready, we’re going to aggressively treat this cancer.”

… they told us, “You’re going to be able to have the baby,” which was wonderful to hear.

How We Took Back Control After the Diagnosis

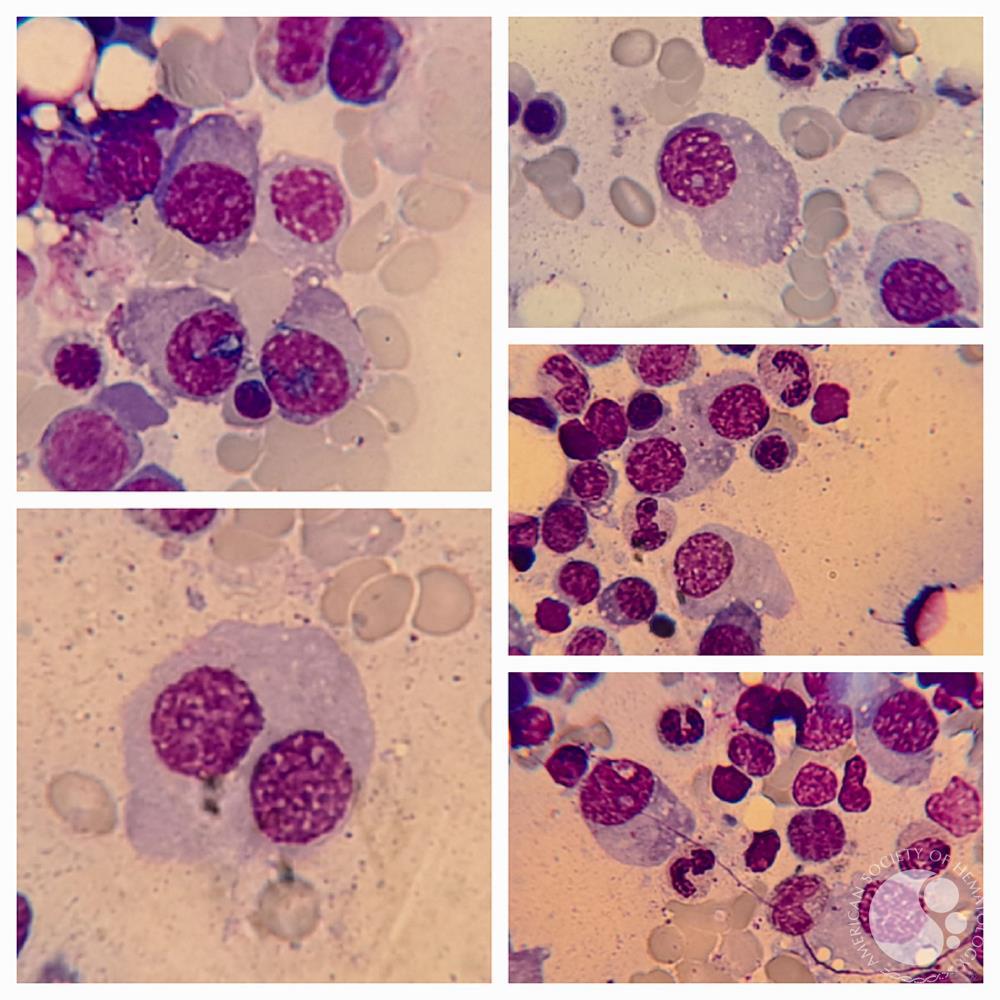

Karina: We learned more about myelofibrosis. We found out that it’s a kind of chronic leukemia and it also is a kind of cancer called a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN).

Patients are literally in a state where they’re watching and waiting for symptoms to manifest. They don’t have control over when they stop taking certain treatments, like oral chemotherapy and blood transfusions, and certainly not when they start experiencing symptoms, such as night sweats and bone and spleen pain.

After I was diagnosed, I waited two years before I shared what I had with people. Firstly, because I didn’t look sick, and unfortunately, too many people stereotype cancer patients as being without hair, looking frail and sick, and so on.

I had all my hair, looked healthy, and acted healthy, too. From day one, I wanted my kids to see me as a strong mom who could still get up and get things done, continue to work, take them to and fetch them from school, and so on.

I not only managed that with the help of Jesse my myelofibrosis care partner, but also ensured that my spirit wasn’t shaken and that I had control of how my mindset was going to be. Because in the watch and wait phase, I was determined to stay in sync with my faith and my conviction that I was going to smile during the storm.

Being in that watch-and-wait phase helped me build a lot of resilience. I needed to be patient with how long my treatment was going to take. At the time, I had no idea that it would be six long years later that I would have my transplant.

Hope Helped Us Build Up to Karina’s Stem Cell Transplant

Karina: That six-year period was long and heavy, and brought me to my knees. But I can summarize it as praising in the storm and staying so focused on that.

This was not going to be my forever. I was determined to do whatever I had to do to get through it.

I learned so much through trial and error. I suffered greatly from gastrointestinal tract issues and had to be in the restroom all the time. I was challenged emotionally, mentally, and physically — but never spiritually.

I continued going to MD Anderson, monthly or however often they asked me to come over. I pushed through my education to graduation, to being an LVN, to becoming a registered nurse, to finishing my Bachelor of Science in Nursing. I even managed to start my family nurse practitioner program before I had my stem cell transplant.

It was just so important to keep going. I underwent a lot of sadness, hardship, and difficulty, and all that entails. But I pressed forward in hope for sure.

There was a lot of hope that just kept me going all those years.

Jesse: I think over those six years, as Karina’s myelofibrosis care partner, it was important for me to constantly remind family, friends, and coworkers that Karina was sick. She mentioned earlier that she didn’t look sick. Of course, she was sick and on chemo — some pretty aggressive oral medicines to boot. But yes, she powered through. She was a trooper, a mom, a student, a wife who was herself so supportive of her family.

It was rough seeing her, because there were times when she wasn’t the same Karina. She was tired, and I had to accept that. And so my role for six years was to be her little battle buddy. Just to make sure that she was okay.

This was not going to be my forever.

I was determined to do whatever I had to do to get through it.

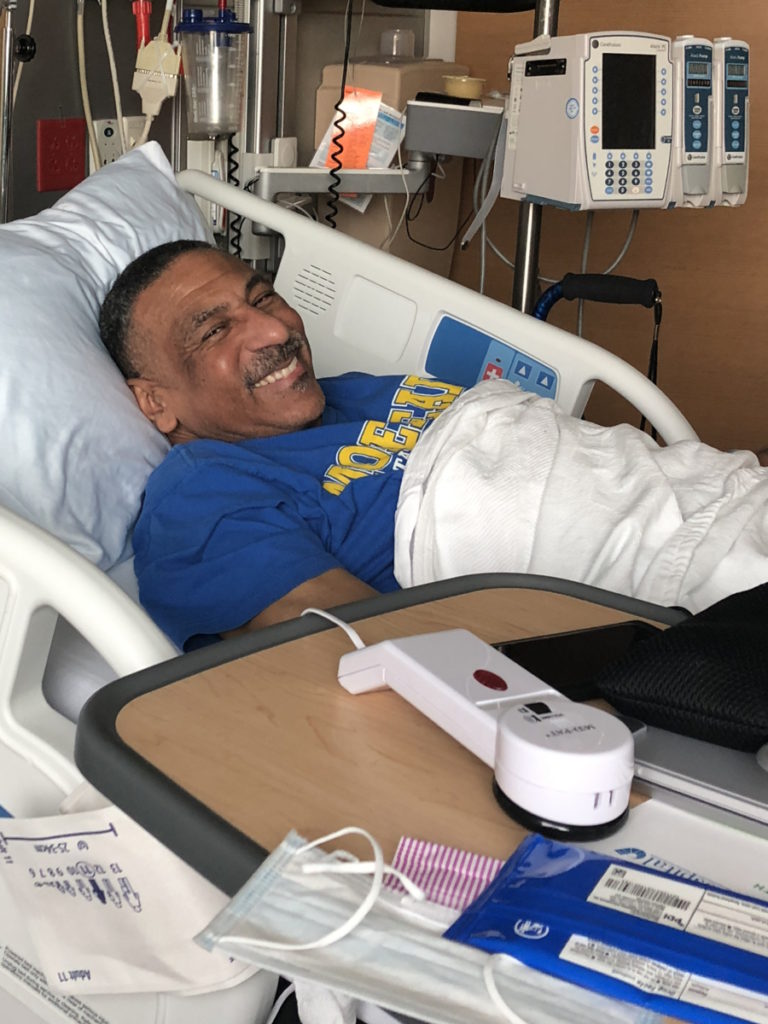

Preparing for Karina’s Transplant

Karina: I remember having a bone marrow biopsy again, locally this time. This is something that you need to do regularly as a myelofibrosis patient. When my bloodwork came in, the doctor flagged it and said that the results were bad and that I would need to be admitted immediately.

I was found to have internal bleeding. Moreover, they also determined that I had developed new mutations aside from the JAK2 mutation — mutations that could lead to me developing acute myeloid leukemia, which only a handful of myelofibrosis patients do.

That was when my doctors at MD Anderson stepped in and said, “It’s time for your stem cell transplant.” I was 39 years old, not getting any younger, but I still had a lot of fight in me. The doctor added, “We’ll still need to do this no matter what, but why wait until everything shuts down? Right now, you have what you need to get you through a transplant.”

My local doctor agreed, and so we started looking for a stem cell donor.

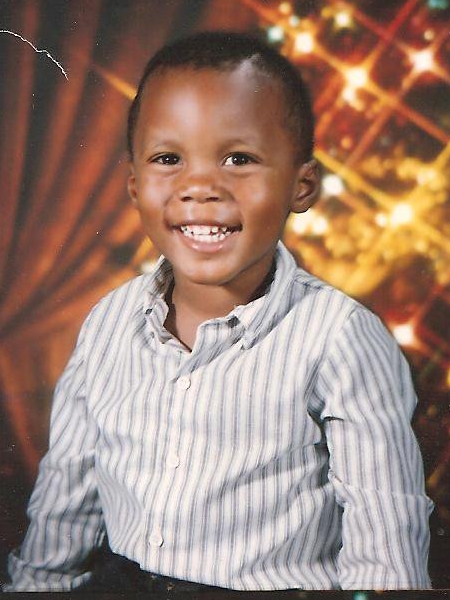

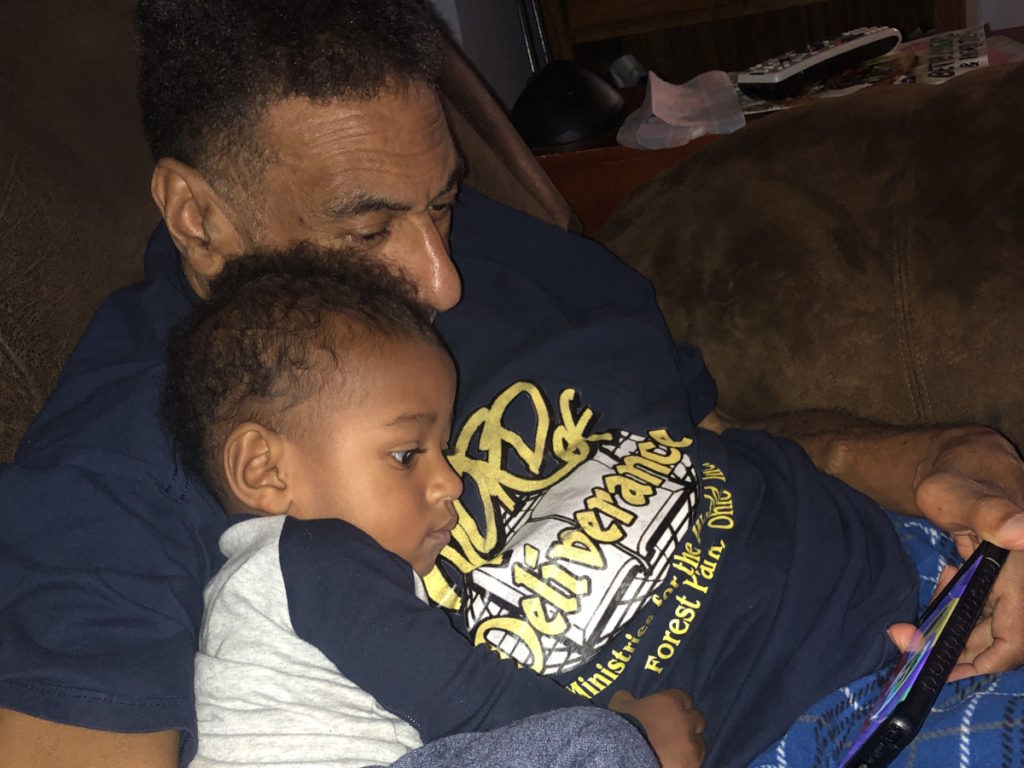

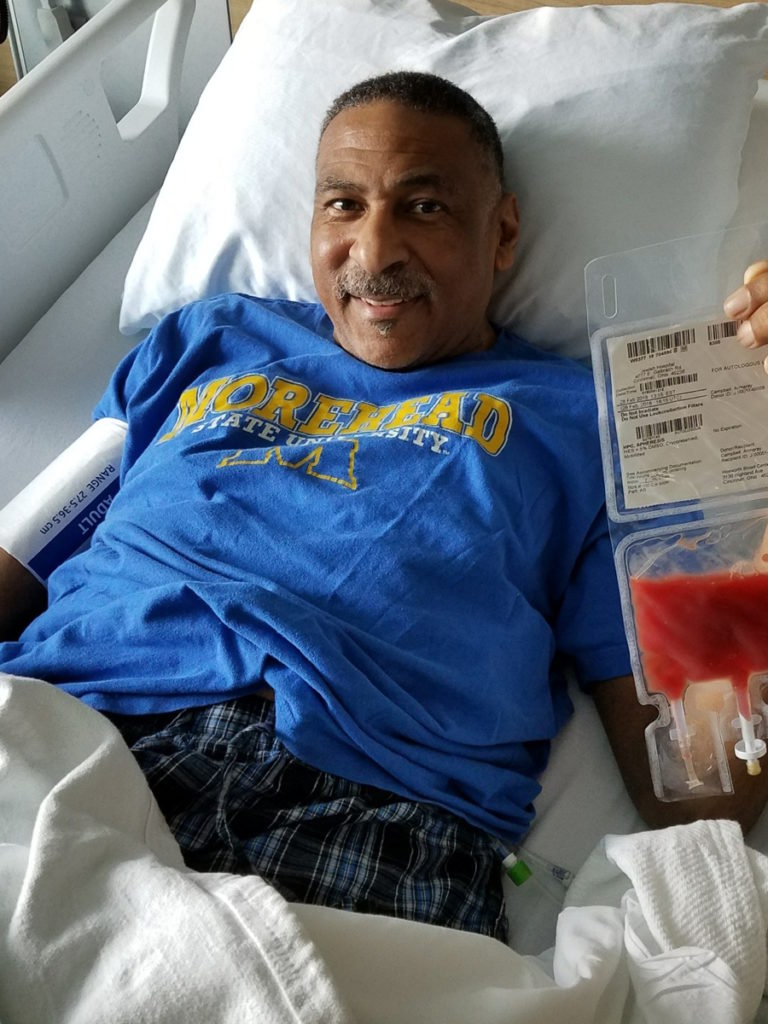

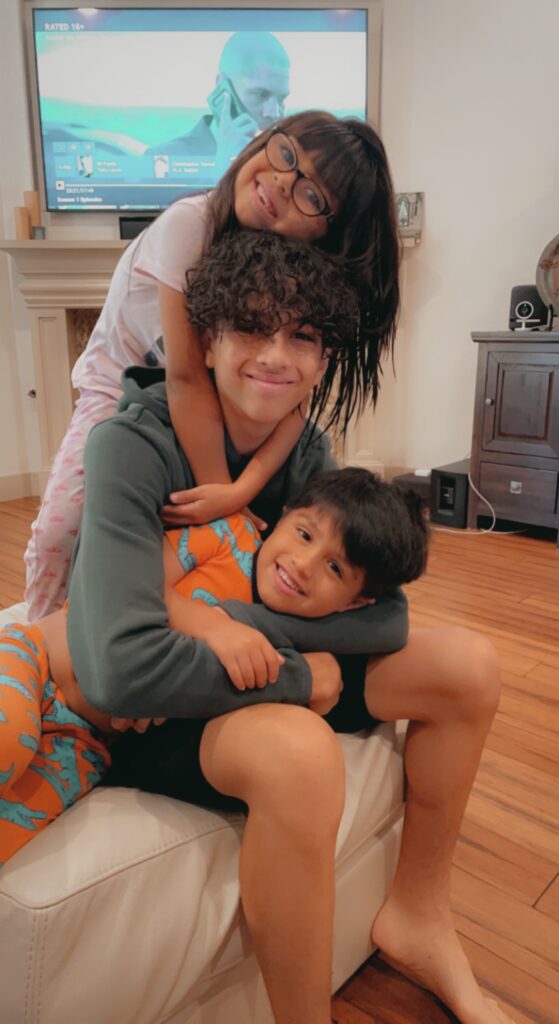

Our Son David Was Karina’s Stem Cell Donor

Karina: I found out the hard way how difficult it could be for a Latina like me, or for most other people from a minority group, for that matter, to be matched with a potential stem cell donor through the registry.

MD Anderson had me on a huge list, but Jesse said, “We can also advocate and go out there ourselves,” And he started orchestrating this big effort. Despite all these efforts, we still couldn’t find a donor.

MD Anderson came to us and said, “How about seeing if your son David is a match while we continue to search?” We asked David if he would be willing to undergo bloodwork to see if he could be my match. It was a no-brainer for him, and he underwent the bloodwork.

I got a phone call a little while afterwards. “We found your match. It’s David.”

I could never put into words what that phone call did for me. I had prayed so hard for this, and my prayer was answered. My donor was under my roof this whole time.

I remember telling him, “I’m so proud of you. Thank you so much. Whether this works or not, you’re my hero. I feel that you’re gifting me life.”

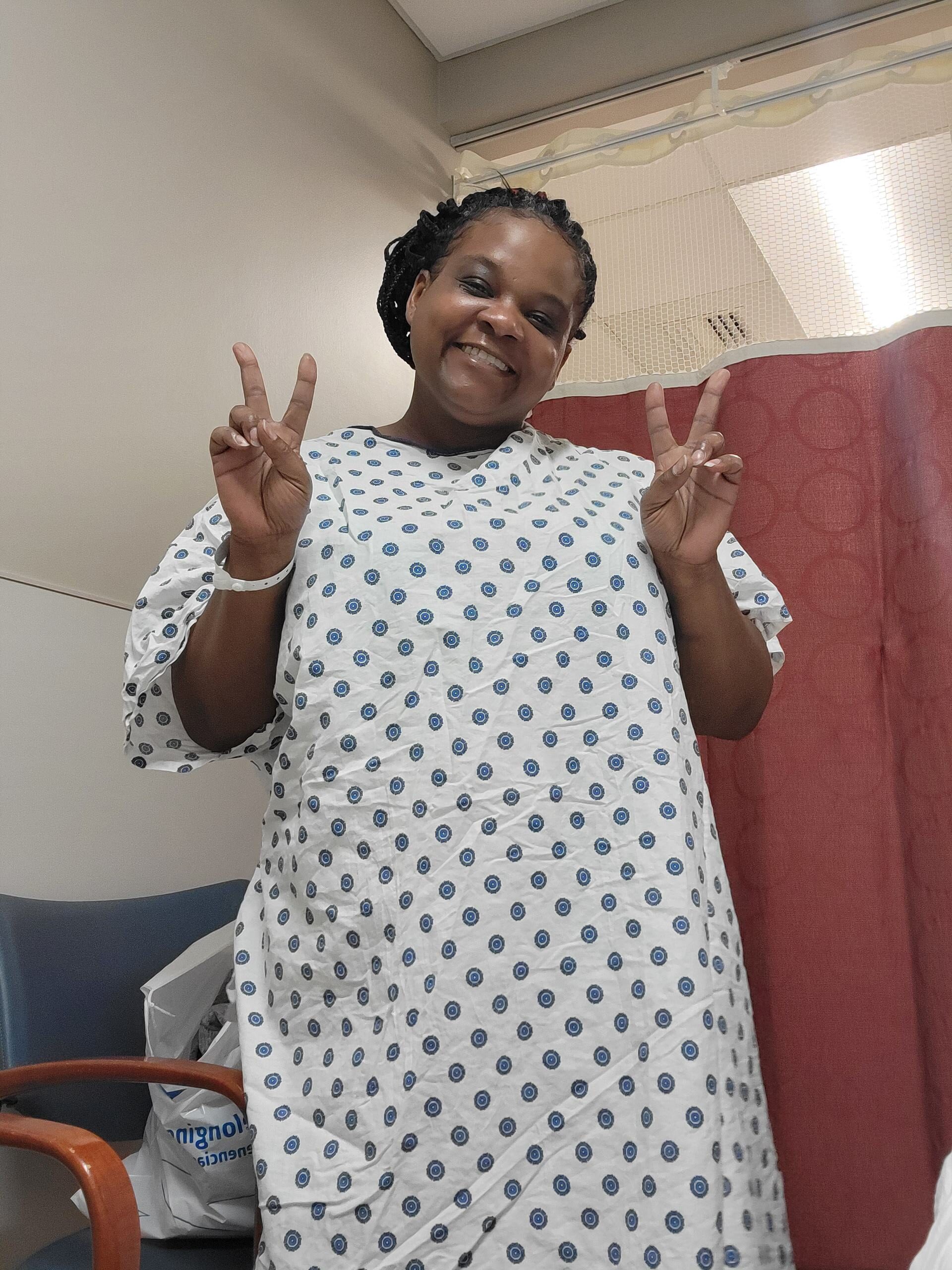

I did a graft of David’s cells. I’m in remission as a result.

I’m a living, breathing miracle because my son gifted me life.

I did a graft of David’s cells. I’m in remission as a result.

I’m a living, breathing miracle because my son gifted me life.

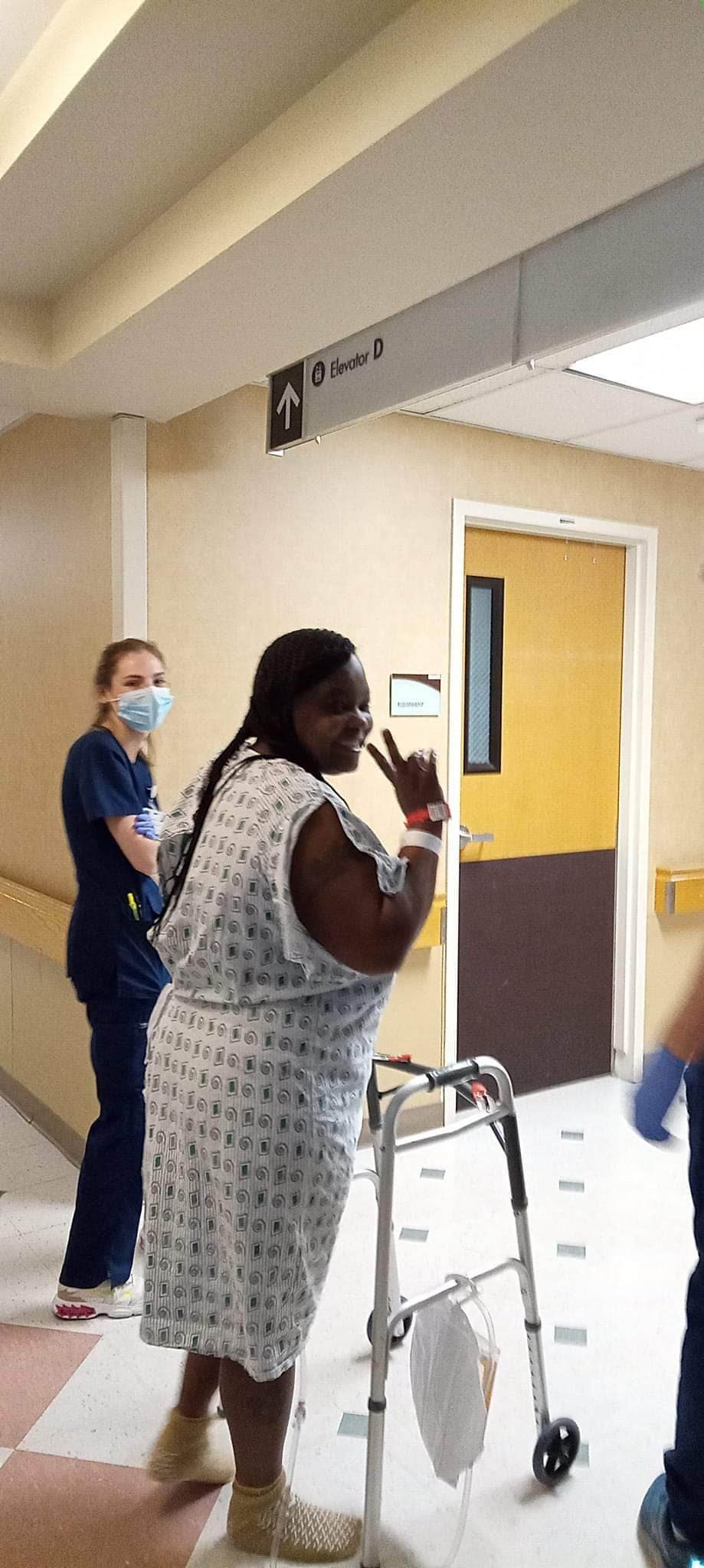

Life After Karina’s Transplant

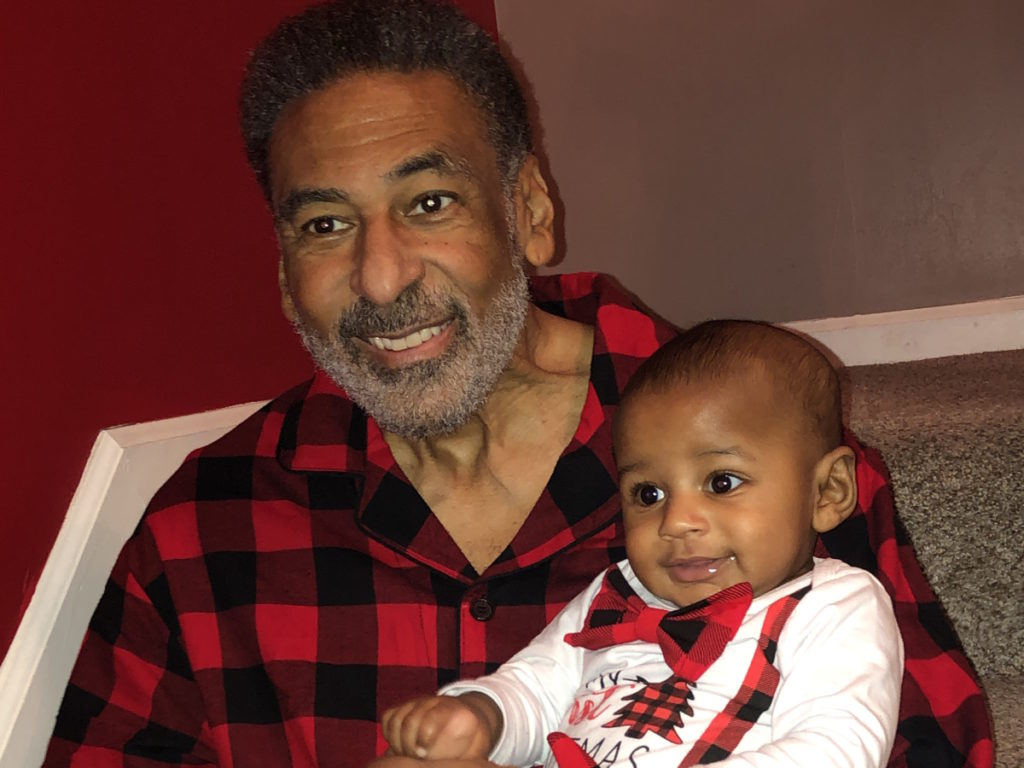

Jesse: We’re going to grow old together, and we’re going to see our kids while we do so. We’re going to be grandparents.

We said that from the very beginning, when we went into transplant, our focus and mindset were: we’re going to get through this, we’ll be grandparents one day.

Karina: It was just tough because I always wanted to put my game face on, and it was really important for me not to worry you. I wanted to let you know: we’ve got this. I’m good.

There were many times I did feel that this was so difficult, and I didn’t know what was going to happen. And I knew that we were going to have to push through this as best we could.

Jesse: You’re my hero. I think that through all of this, I have a profound respect for everything that you’ve done through the entire cancer experience. I don’t think I’ve told you that enough. How proud I am of you and how you’ve powered through — continuing with your studies and with being a mom and with being a wife to a guy in the military who leaves all the time, and so I’m just so proud.

Karina: I would say that cancer and your experience being my myelofibrosis care partner amplified your good heart. I know you know this and that you’ve been so constant since day one. You’ve made all the promises you’ve kept. You’ve never failed me in any way. You’re God-centered. Even after all the changes I underwent due to my experience, including my appearance changing radically, you’ve been right with me.

I realized that we’re a divine orchestration that God set for us. I was so blessed and continue to be so blessed to have found this genuine love.

There were many times I did feel that this was so difficult, and I didn’t know what was going to happen. And I knew that we were going to have to push through this as best we could.

What We Want Other MPN Patients to Know

Karina: The most important thing that got me through is the power of the mindset. When we can’t control what our body is doing or what’s to come, when we’re uncertain of many things, the one thing we can control is our outlook about all of it.

And be easy on yourself. You’re going through so much. Love yourself during this time. Know how to facilitate a healthy mindset. It’s beneficial from beginning to end.

Our Advice for Other Caregivers and Care Partners

Jesse: Have a supportive mindset, but take care of yourself as well.

As a myelofibrosis care partner, or a care partner in general, you can sometimes feel that the world is on your shoulders. Seeing your significant other struggle and hurt isn’t easy. Not having all the answers is extremely difficult.

Education is one thing, but above all, have that positive mindset, and be supportive of the person that you love who is ill.

The most important thing that got me through is the power of the mindset…

… when we’re uncertain of many things, the one thing we can control is our outlook about all of it.

Special thanks again to Karyopharm Therapeutics for its support of our independent patient education content. The Patient Story retains full editorial control.

Inspired by Jesse and Karina's story?

Share your story, too!

More Myelofibrosis Stories

How to Support Someone with Cancer: Karina & Jesse's Myelofibrosis Story

“I underwent a lot of sadness, hardship, and difficulty, and all that entails. But I pressed forward in hope for sure. There was a lot of hope that just kept me going all those years.”

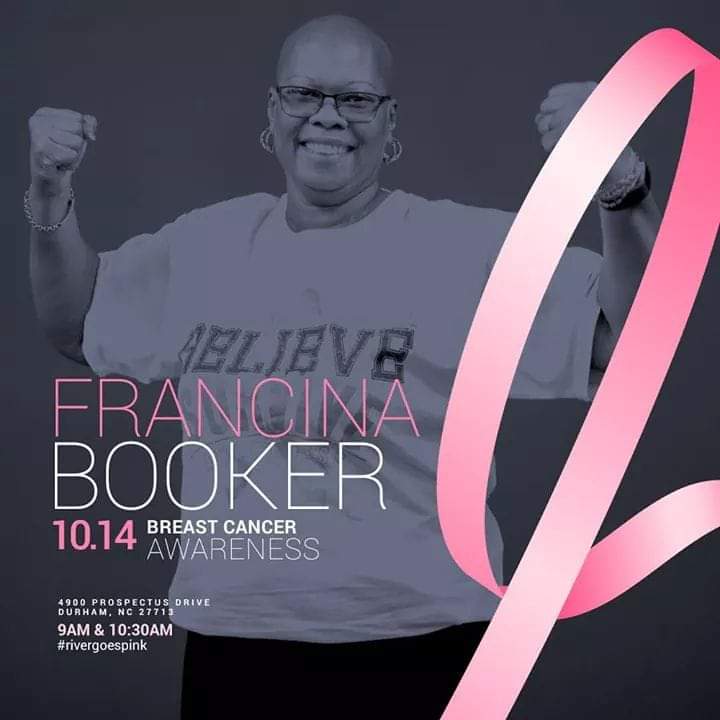

Demetria J., Essential Thrombocythemia (ET) progressing to Myelofibrosis

Symptoms: Extreme fatigue, stomach pain (later identified as due to an enlarged spleen), dizziness, shortness of breath

Treatments: Spleen-shrinking medication, regular blood transfusions, bone marrow transplant

Neal H., Prefibrotic Myelofibrosis

Symptoms: Night sweats, severe itching, abdominal pain, bone pain

Treatment: Tumor necrosis factor blocker, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, testosterone replacement therapy

Andrea S., essential thrombocythemia (ET) progressing to Myelofibrosis

Symptoms: Fatigue, anemia

Treatments: Targeted therapy (JAK inhibitor), blood transfusions, allogeneic stem cell transplant