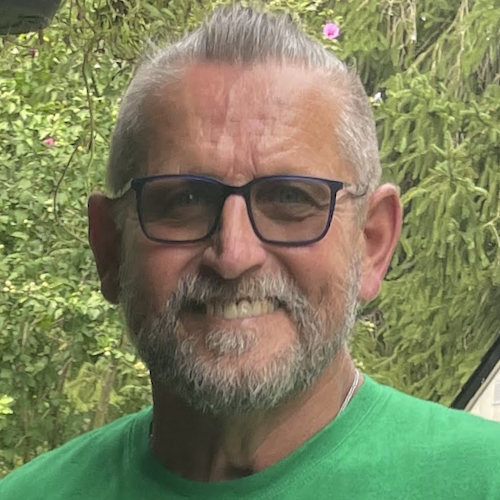

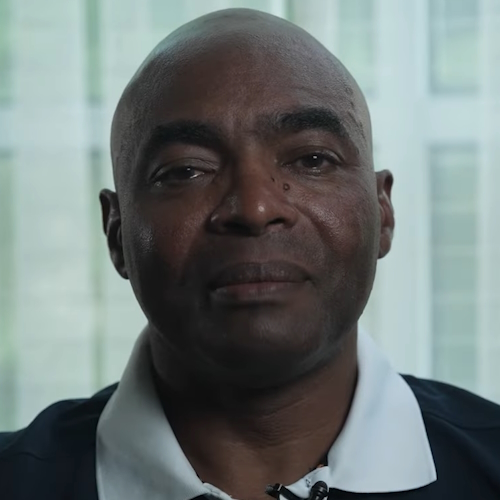

Tony’s Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Story

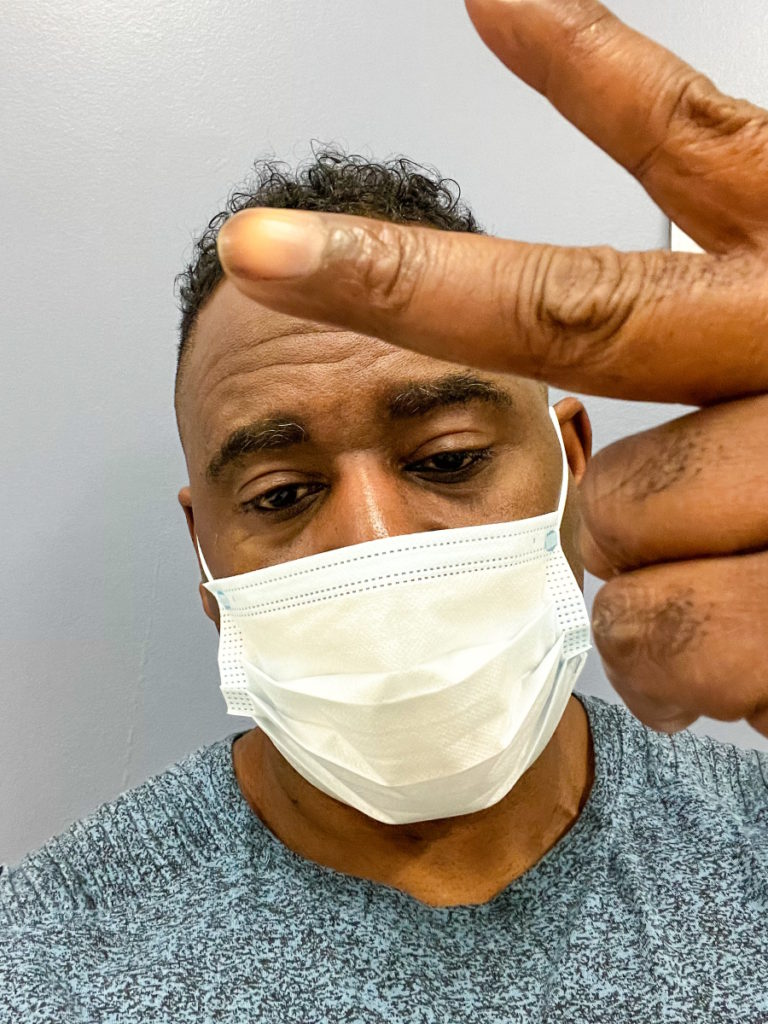

Tony was in peak physical condition, working out several times a day when he suddenly began to struggle with fatigue.

After undergoing scans and tests, he was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the most common adult form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He would later learn that his specific subtype is known as T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (THRLBCL).

Before his diagnosis, Tony was an avid cyclist and fitness enthusiast. He noticed a decline in his physical performance despite his extensive training routine, as well as swelling in his leg. After consulting with his chiropractor and internal specialist, a CAT scan revealed that he had cancer.

Although his blood tests did not indicate lymphoma, the cancer had spread extensively throughout his body, leading his doctor to believe that he may have had it for years without knowing.

Tony made a conscious decision to keep a mindset of strength and perseverance that allowed him to face his diagnosis.

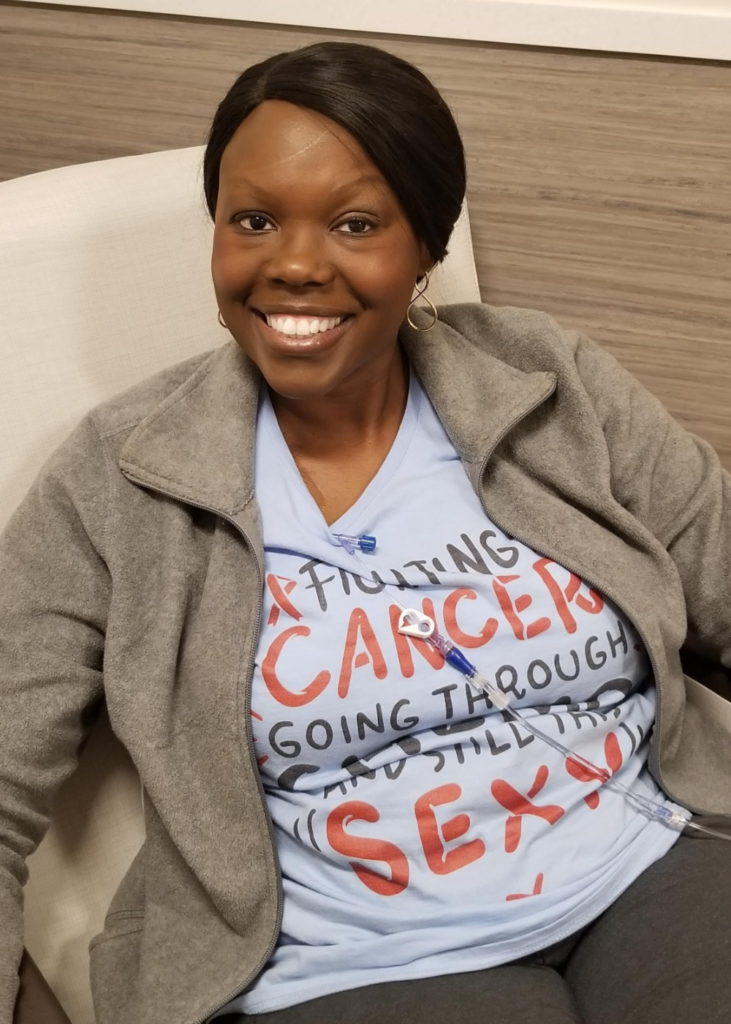

He voices how he processed his diagnosis, how he dealt with the side effects of R-CHOP chemotherapy and CAR T-cell therapy, and what he did to stay mentally and physically strong.

Thank you to Genmab & AbbVie for their support of our patient education program! The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

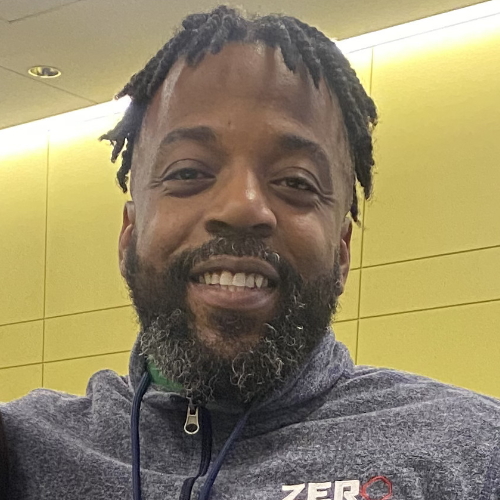

- Name: Tony W.

- Diagnosis:

- Relapsed T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (THRBCL)

- Initial Symptoms:

- A lot of effort needed cycling; body wasn’t responding the same

- Leg swelling

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy: R-CHOP

- CAR T-cell therapy

Introduction

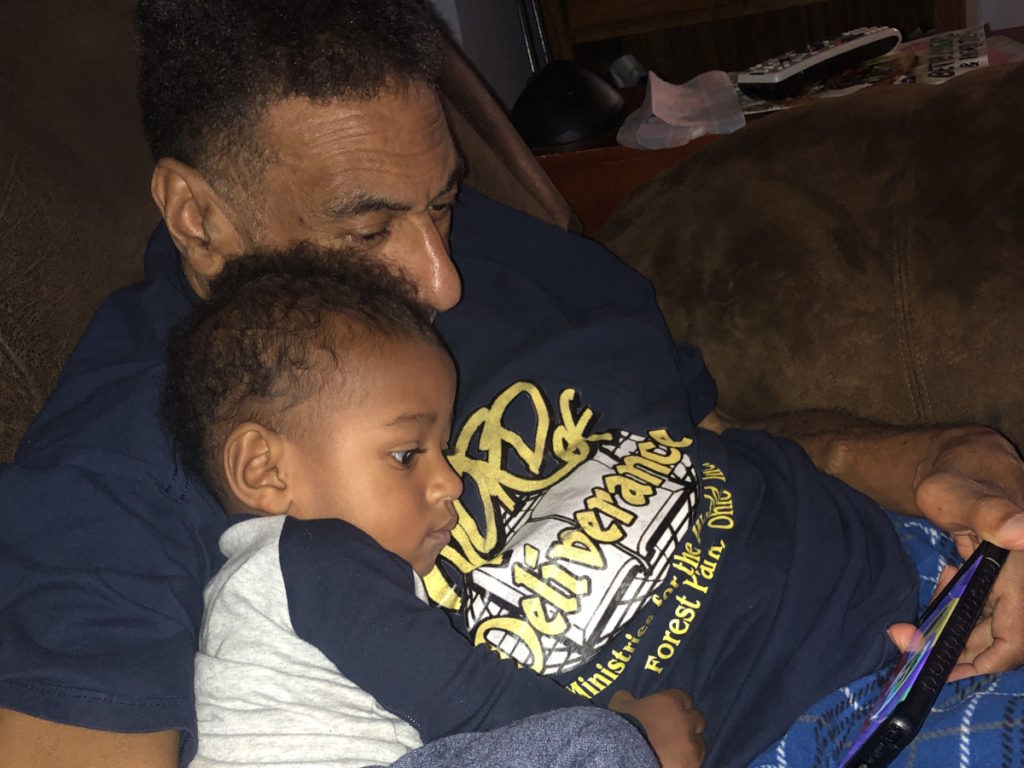

I’m an igniter. I have started several businesses in my career.

I went to North Carolina State University and majored in civil engineering and pre-med. I wanted to be a doctor at some point.

I’m an avid cyclist. I love to work out.

I’m a go-getter. I can’t sit still. I like to initiate things and see things come to fruition.

I’ve always been that person that didn’t need someone else to motivate me. I’ve been highly self-motivated [throughout] my 51 years on this planet. I just love learning new things.

I play the organ, the bass guitar, [and] the saxophone. I love music. I sing [and] write music.

Anything that I put my mind to, I try to do the best that I can do.

My T-cell histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma story

If you ask anyone who knows me, they would say, “No, not him. Can’t be Tony. No, you’re joking.” I lost a lot because COVID hit exactly at the same time. It was rampant when I got sick.

At the time, I had about 200 employees working for me. We lost a lot of contracts and things were just out of my hands. I couldn’t do anything about it because I had to focus 100% on my health.

Cancer doesn’t care [about] your economic background, what race you are. [or] your social status. When it comes for you, it will come for you no matter what you thought you had built up in life.

I thought I was leaving some legacy behind and it came for me. What am I going to do after it comes for me? I never asked myself why. I said, “Okay, why not?” And that was my approach. Why not?

I’m a guy that works hard, does a lot in the community, [and is] active in the church. There’s no discrimination. It can happen to anybody.

Pre-diagnosis

Initial symptoms

I’m an avid cyclist. We ride a lot of miles. At that point, I was doing about 350 miles a week. Being in an endurance sport, you learn [about] your body.

I have this reputation on the team of being pretty fast and pretty fit. I wasn’t giving the guys the business like I normally would be doing. It was just a lot of effort. Something wasn’t right.

They couldn’t really tell any difference because I just won’t stop. I give everything I have, but my body was not responding the same. If I wanted to go an extra five miles an hour, it was a struggle. Coming out the curb or the corner trying to chase somebody down was a struggle.

Then I started noticing that my leg was swelling. I lift weights a lot. I do spin class a lot. I said, “Maybe I hurt my back.” My chiropractor worked on it and she said, “This isn’t getting better. Your leg is swelling.” We thought it was sciatica nerve, but it wasn’t. She said, “Maybe you need to go see your internal specialist.”

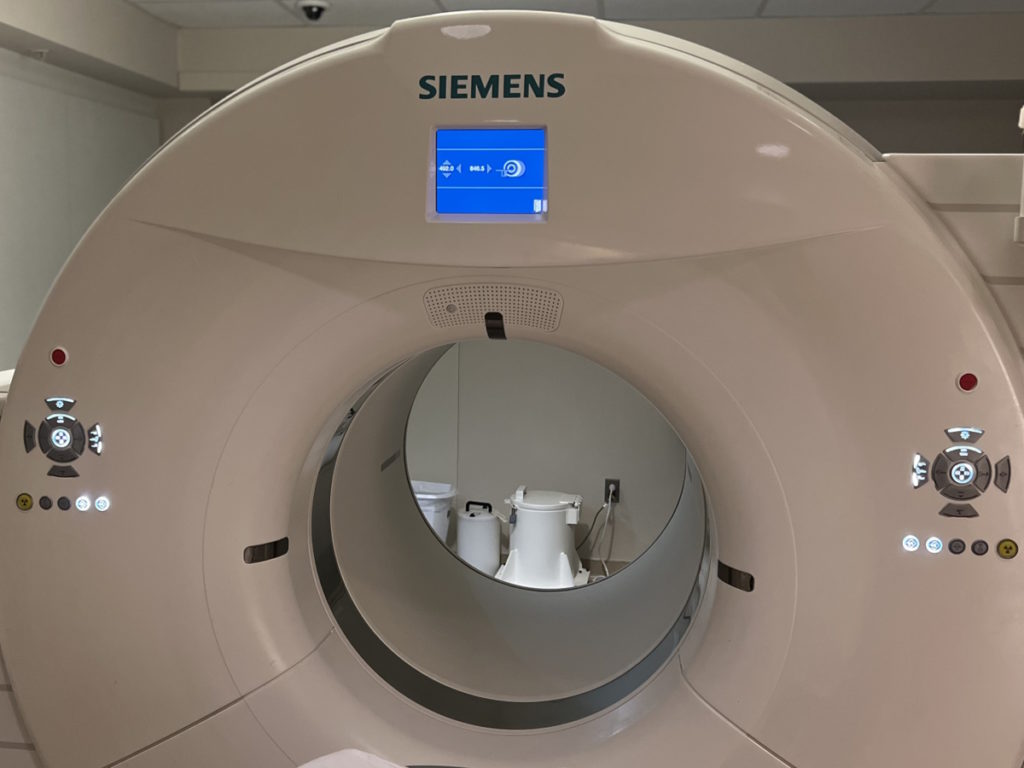

I went to the internal specialist. We were thinking maybe I had kidney stones or something bacterial was causing me to experience this. When she checked me out, she said, “You look healthy. There’s nothing wrong. Your blood looks fine. But how about we just do a CAT scan?”

That’s when we had that “Oh my!” moment.

I was 49 going into 50 years old that year. I thought I was going to have this great 50th celebration. I was sitting in a chemo chair on my birthday.

When I first saw my oncologist, the first words that came out of his mouth [were], “If you were not as fit as you are, we would be having a different conversation.” All those miles, all that training, spin class, and gym work, whatever small percentage that was, gave me a jump start and it might have saved my life.

I’ve been an athlete all my life. You develop this push-through-no-matter-what mentality. We push past the threshold. That’s not a good thing all the time.

Think about professional athletes [and] collegiate athletes. Everybody pushes through but they pay for it [in] the end. That’s the mentality that you develop. No matter how you feel, you just push through.

“This hurts.” Push through. “I feel a sore here.” Push through. You develop that mentality that I’m going to beat whatever how I’m feeling and I’m going to still push through. That’s simply what I was doing.

Diagnosis

My blood wasn’t giving them anything. They would run my blood and it would come back good. No signs of lymphoma.

I look at it as if it was the perfect storm. If your body was going to operate in its most perfect form, my lymph nodes did exactly what they were supposed to do.

My cancer was so prevalent that my doctor thought I might have had it for years and didn’t even know it. It had completely taken over my stomach, my lung, everywhere.

I could see the fright in my doctor’s eyes when he saw [the scan], but he could see the tenacity in my eyes. When he told me what it was, [he went] over options.

I had to make a conscious decision. What are you going to do about it? There [wasn’t] any time for tears. I didn’t cry at all. I sat there and made a decision. I looked him in the face and said, “Okay, game on. Let’s go.”

I cried later but [at] that moment, I made a decision. I had to let the cancer in my body know: I’m not giving you victory in my mind this quickly.

I created this alternate reality. I created this warrior mentality. “You coming for me? I’m going to come for you.” No matter what my doctor said, I already told myself that [I’m] going to beat this. I’m going to do whatever I have to do to overcome this.

Breaking the news to family & friends

Initially, I didn’t let anyone know. I’m very methodical and I like to see things through before I bring attention to something. I want to have control of the situation. I wanted to know exactly what was happening because people are going to have a lot of questions.

Going through a chiropractor and my initial doctor locally and even once my oncologist told me, I still didn’t tell them about it. I waited.

I went for a walk. We have a pond in my neighborhood so I sat out there on the pond bench and that’s when I had my moment.

I called my mom. I’m the first child, the oldest grandchild. I remember telling my mom, “I don’t want to die.” She said, “What are you talking about?” I started crying and that’s when I told her.

My wife was there so she knew, but she was frightened. She didn’t know what to say or what to do. Then I told one of my best friends.

It hit me when I was talking to my mom. That’s the person that birthed me. It was devastating.

After that conversation, I zipped those tears up. I said, “It’s not a crying situation. It’s time to go. Time to go to work.”

Drawing boundaries

I said that I will not let family and friends imprint on me. We’re going through enough as is. We know our odds. We know the percentages. We know what we’re facing. Sometimes, [because of] their mere concern for you and all the emotions they bring to the situation, loved ones will compound your situation.

You have to put them at arm’s length. You can’t take on what they’re saying because sometimes, out of love, they will give you bad information or will remind you, “Only 1% of people live from this?” They don’t mean any harm but their words will hurt you.

This is what I did. Love your loved ones, but guard yourself. At the end of the day, it’s a one-on-one thing. You’re battling that cancer. You’re battling everything that comes with it. They’re not doing that with you. They will stand with you, but they’re not here. That’s where your battle is.

The crying was symbolic of accepting what was happening. It’s real. We can create all the alter egos we want, but accept that it’s real. The crying just released that in me.

I felt free. A freeness came over me. It was a calm and peace that came over me. I felt like it was necessary.

A lot of times, men are providers. We like to take care of things. We have our egos. We want to feel important. We validate ourselves by what we can do for you, what we can give you, or how we can protect you.

We’re not conditioned to be as emotional. Women are more emotional incubators and that’s a good thing because you need to have that balance. We need to have that also as men and sometimes we don’t. If you hold that in, [it’s] just adding more stress to your situation.

Crying and releasing helped me further along in my process versus me doing it at a time that wouldn’t be optimal. I was doing soul-searching, too. I thought, “Tony, you have done this. You came through this. You have broken through this ceiling. You have done all of these things. You can do that, too.” That’s how I approached it and it helped me.

Treatment

I had R-CHOP, which was pretty nasty.

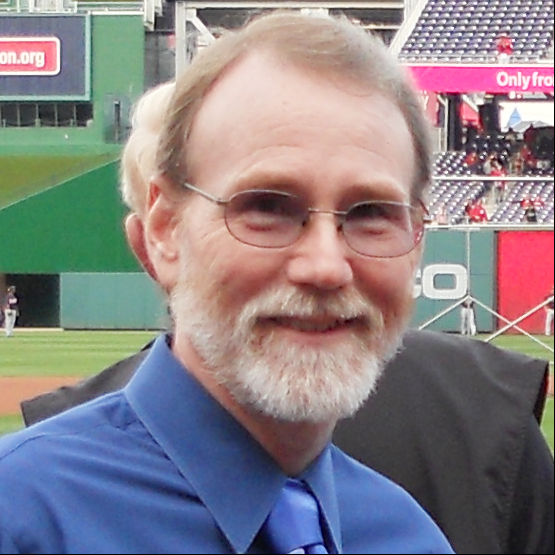

I left my local doctor and went to [the] UNC hospital system. That’s where I met Dr. Boles, my oncologist. We talked about my treatment plan. He gave me all the options and encouraged me to get a second opinion.

But I already knew. When you know, you know.

When I look that man in the eyes, I see a caring, compassionate person [who’s] concerned for me. And that’s important because sometimes, a lot of us will get someone [who] doesn’t have [a] good bedside manner, just matter of fact, or [will] bring gloom to your situation and you already know it’s gloomy.

He talked to me almost like the big brother going to the little brother who’s a doctor. You’re putting your trust in the little brother now because he has [the] skill set you don’t have. That’s [the] kind of relationship he and I have. I was the big brother who was relying on him as my little brother to take care of me.

One thing he told me [was], “Tony, by nature, you’re not a selfish person. You employed people, started a cycling club, and you did all these things. You give a lot to people. But I need you to be selfish. This is the one time you will have to be the most selfish in your life.

“You have to block out all the background noise, all the chatter. Stay off of Google. Inundate yourself enough that you understand what’s going on with you, but don’t deep dive to the point that it causes hysteria.”

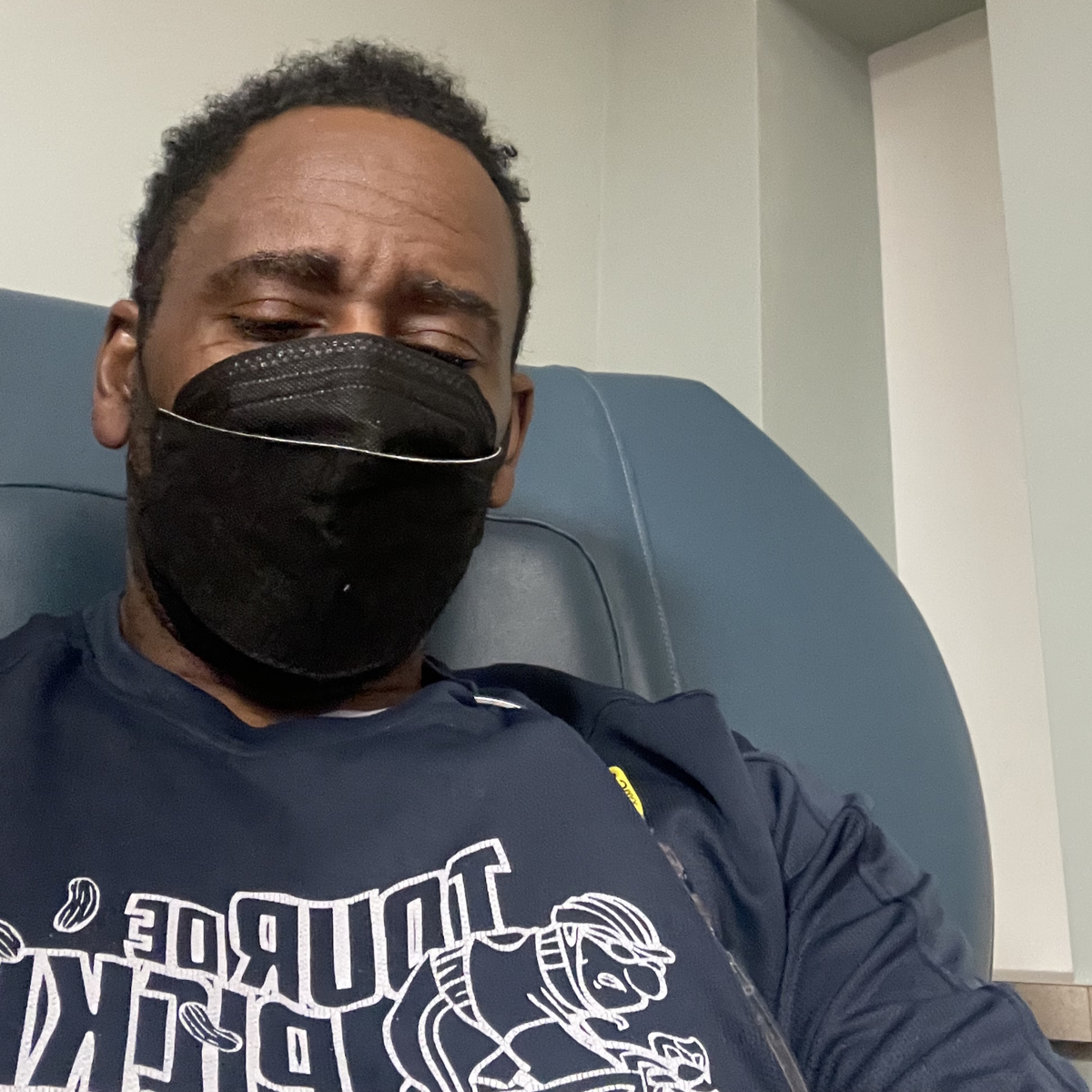

Keeping physically active during treatment

[During] certain rounds of my chemo, I was walking five miles a day every day and doing my spin trainer 30 minutes a day.

Finally, Dr. Boles said, “Tony, you got to pick one. You can’t keep doing both.” I already made a determination that I wasn’t going to let those chemicals run roughshod in my body and not do something about it.

I’m out there walking when I was feeling sick, made my other body systems kick in, and it made me feel better than just sitting there. Doing pushups gave me something to look forward to. It made me feel defiant. The more I became defiant, the more I start seeing victories.

Instead of losing weight, I was gaining weight. I was gaining muscle when I shouldn’t have been gaining muscle.

When I look sick, it affected everybody around me. They didn’t know how to handle me. They were very cautious because it was just so unnerving. Not only did I have cancer, which was evoking something in them, I now physically looked the part.

When I first got diagnosed, I got down to 167 pounds. I went to my doctor after chemo and one of my PAs said, “Tony, you’re losing too much weight.”

I basically starved cancer. I stopped eating bread [and] sugar. I only ate green greens like spinach and kale. I said, “I’m not giving you anything that you can live off of.” I was losing 6-7 pounds a week. She said, “You can’t do that. You’re losing way too much weight.”

The next time she saw me two weeks later, I was at 190 pounds. When she saw me the next week, I was at 205. I never stopped. I started doing pushups. I start physically challenging myself.

You don’t have to be that extreme, but I didn’t have anything else to do. I do believe that if you’re not physically fit or capable of that, do something. Don’t sit there. Show cancer that you will be defiant.

Dr. Boles told me, “Tony, one of my biggest challenges with my patients is me looking at them and saying, ‘Maybe just walk.’ But I’m looking at a person that never walked in their life so I have to be realistic and say if they weren’t walking before, it’s going to be hard for them to walk afterward. If everybody would just physically move their body, you’re going to move those processes along in your body.”

Chemo is designed to fight cancer, but it wreaks havoc on your organs. That’s a problem for a lot of people. I said to myself, “I need a healthy lung, I need a healthy spleen, I need a healthy heart,” and the only way I knew to keep those things active was to move. That’s what I chose to do.

I’m not trying to be anybody’s superhero. You have a baseline and then you have an extreme. All of us still want the same thing, to be cured and healed. I did, too. I chose the extreme. At the end of the day, we all want to get to the same place. Choose what motivates you to get to that place.

Side effects of R-CHOP chemotherapy

R-CHOP was funny. I’m just an enigma. Because I was doing those things, I’m just breaking all the rules.

I was going every 21 days. After my first R-CHOP session, Dr. Boles and the team would say “How are you feeling? You feel any chills?” No. “Sweats?” No. “Your hair? Well, obviously, your hair is not falling out.” Mm-mm. “You feel nauseous?” Nope.

I had no symptoms that first week. I really believe they didn’t believe me because he dragged me back in there right after the next R-CHOP session to test me. I didn’t feel anything. I was saying, “Oh, this is going to be easy.”

[The] second week, [I] got really sick. I was going into this pattern. [The] first week, I was good. [The] second week, didn’t feel so good. [The] third week, the light came on and I felt like I was back. That was my process all the way throughout like clockwork.

My body is responding pretty well. I had the Red Devil. I’m doing fine.

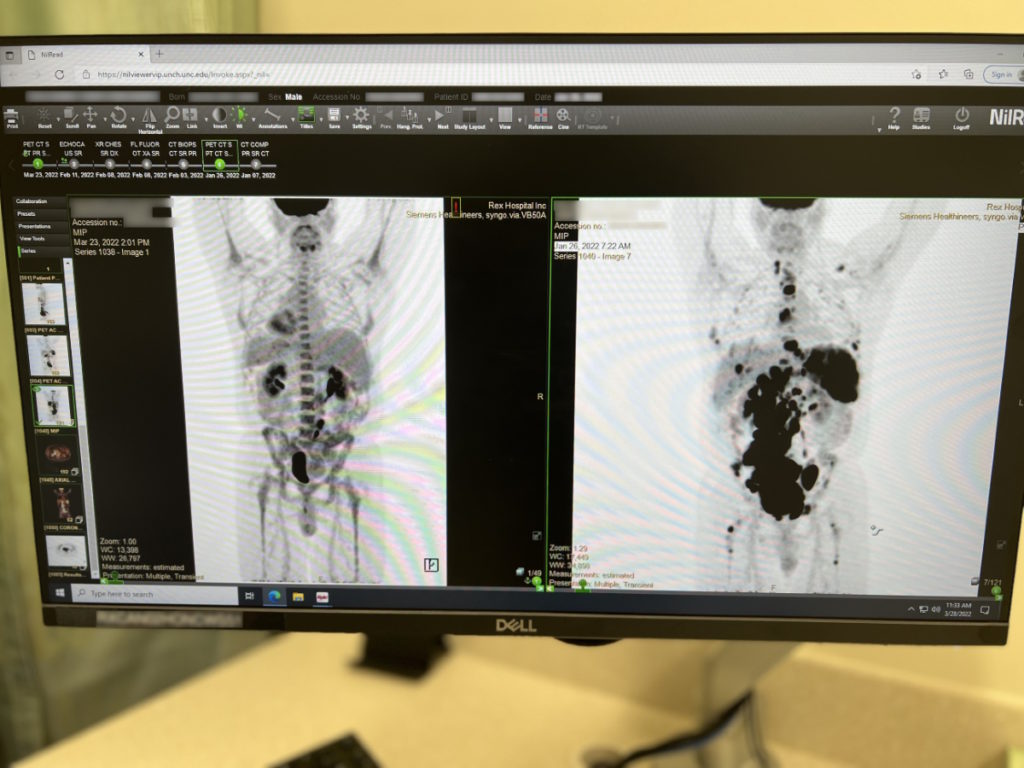

The right-hand side [of] my initial scan [was] what it looked like when I first walked into the door. A couple of weeks later, on the left side, was my scan after and that was a premature scan because he wanted to see what was going on. You could see how much of that cancer was eradicated just like that.

On my second round of R-CHOP, I see a bunch of needles. I said, “Whoa! Where are the bags?” They started giving me injections in the stomach.

Dr. Boles said, “You responded so well we’re going to go with some direct shots,” and they [were] putting half of my chemo directly in my stomach because I could handle it. That’s how strong my body was.

I have a port. I recommend getting a port because it saves your veins in the long run.

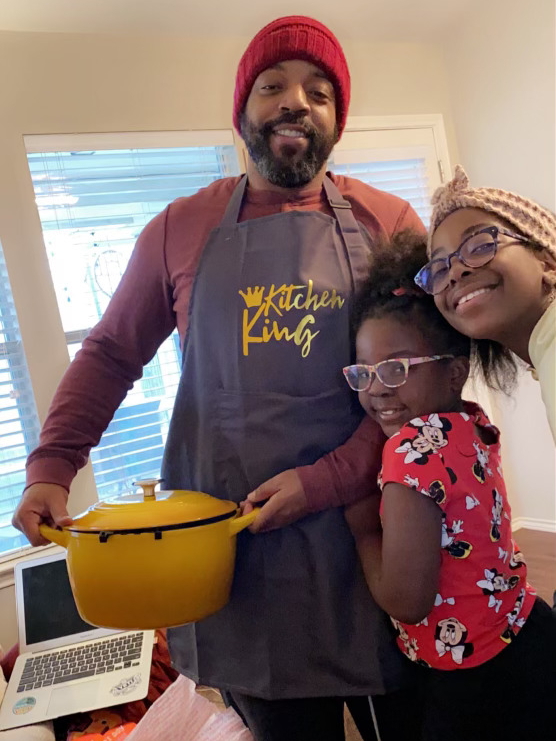

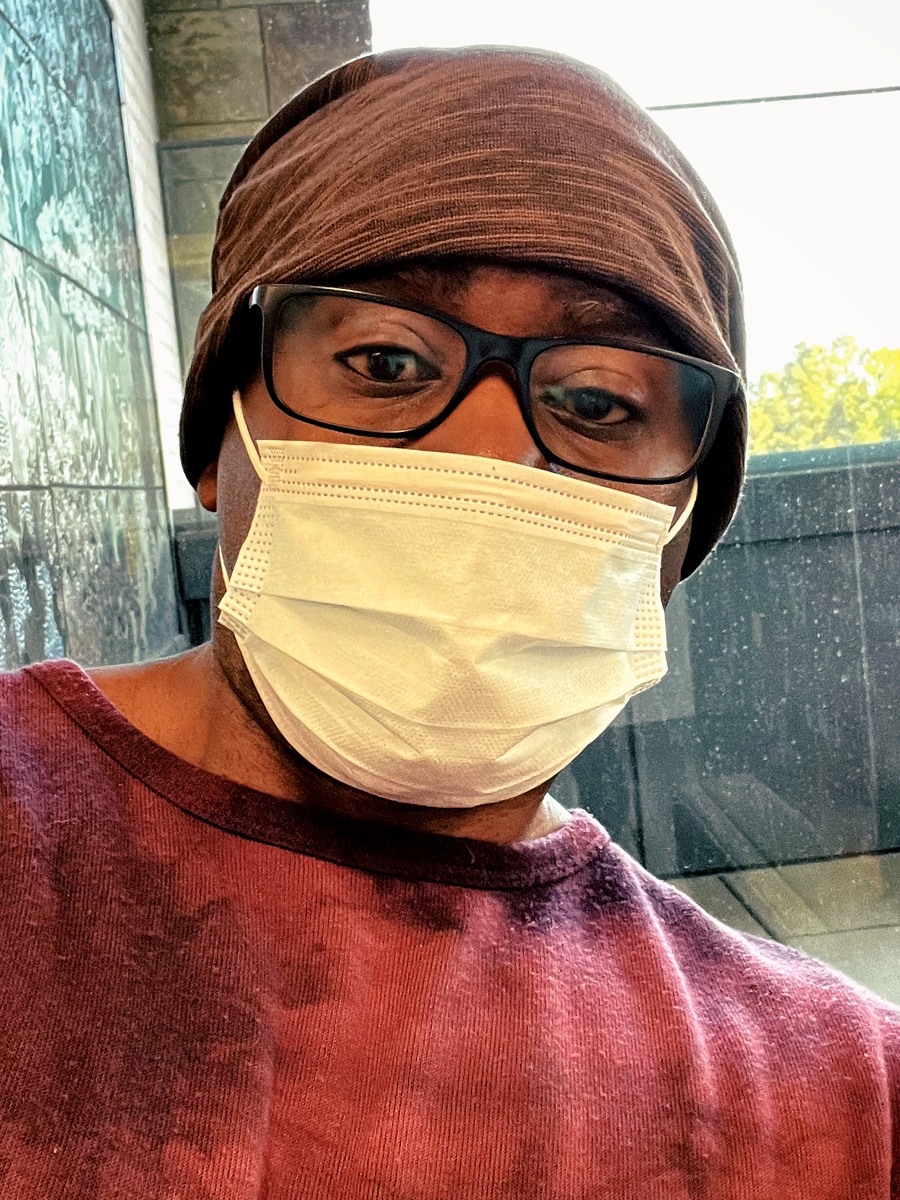

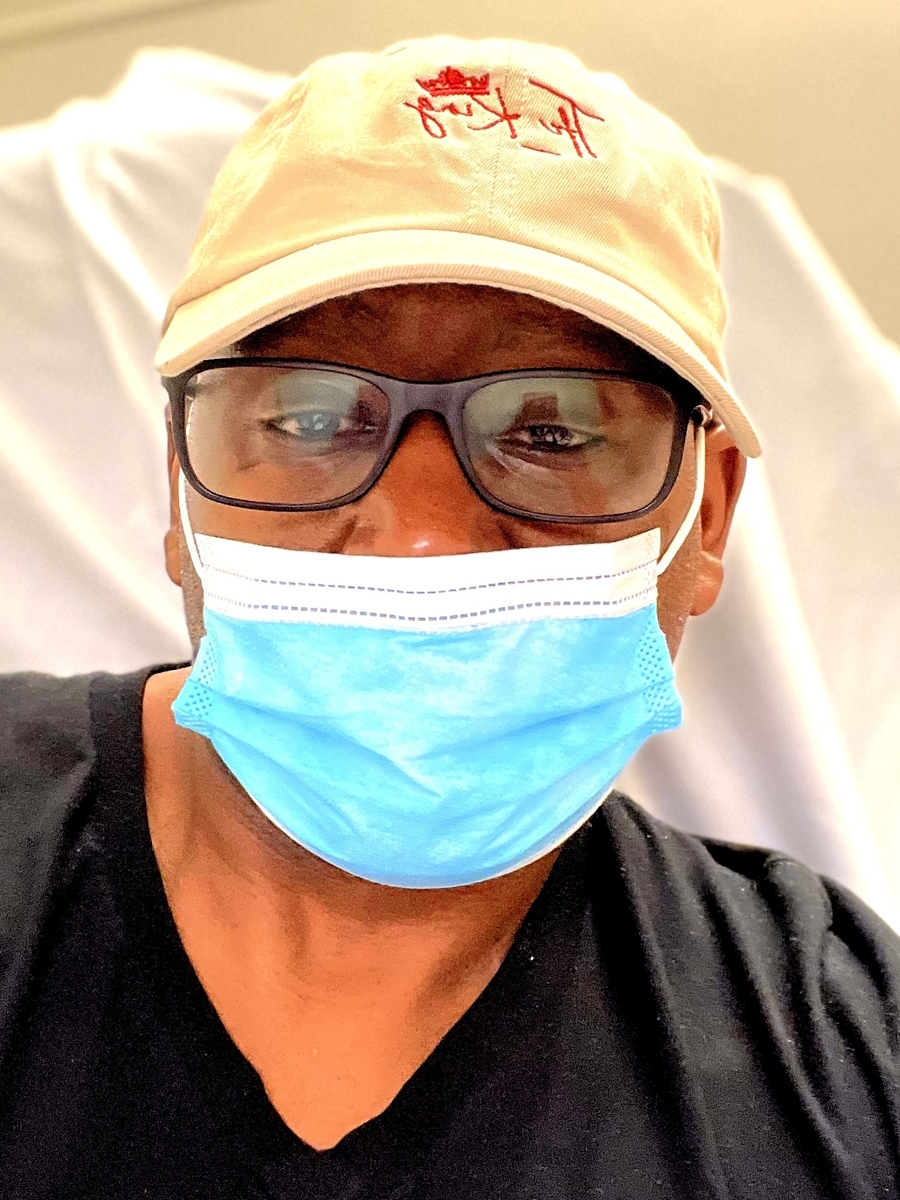

Hair loss from chemotherapy

Hair loss kicked in on my third session. I went to the bathroom, cut my hair, and it just start coming out in globs. It went just like that.

Your hair’s like your badge of honor. You take honor in that until you have that recessive gene and you lose it and can do nothing about it. But that hadn’t hit me so I still had mine.

You’re not going to get through this with no [side effects] at all and hair was one of them. To lose that, I felt like this is real. Cancer is still fighting. The chemo is doing what it’s supposed to do. It just was a reality check for me.

I would cover my head a lot. I didn’t like the bald look so I don’t have a lot of pictures from that. I don’t want to be reminded of that. I started wearing beanies and look more stylish, but there was no hair.

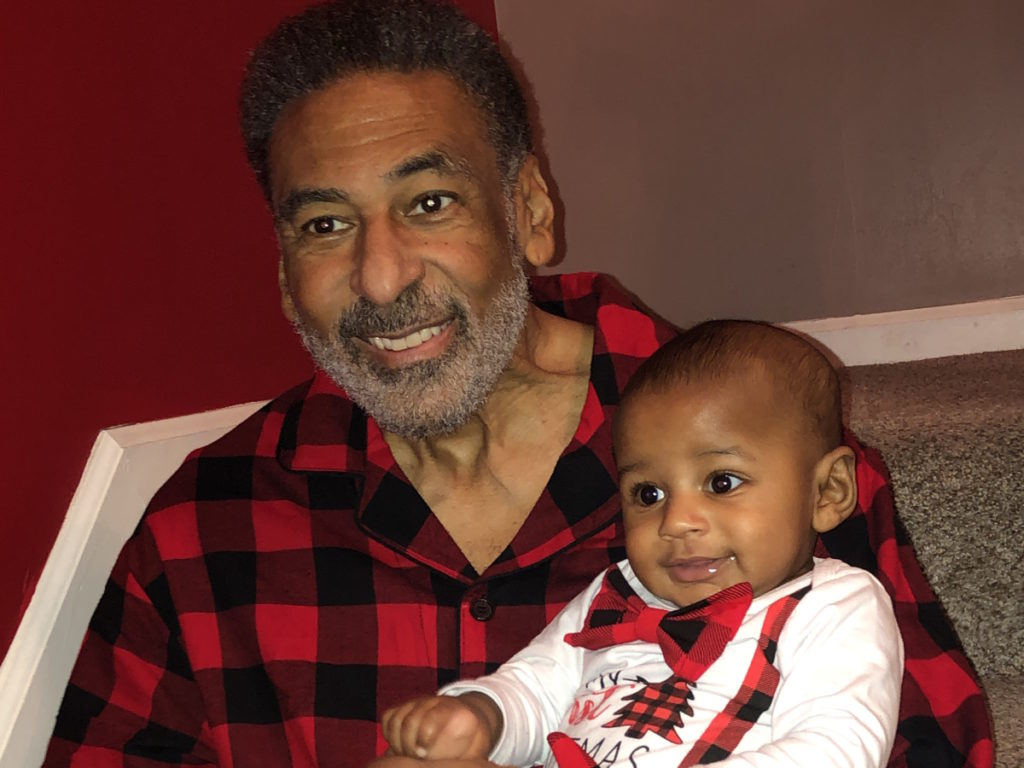

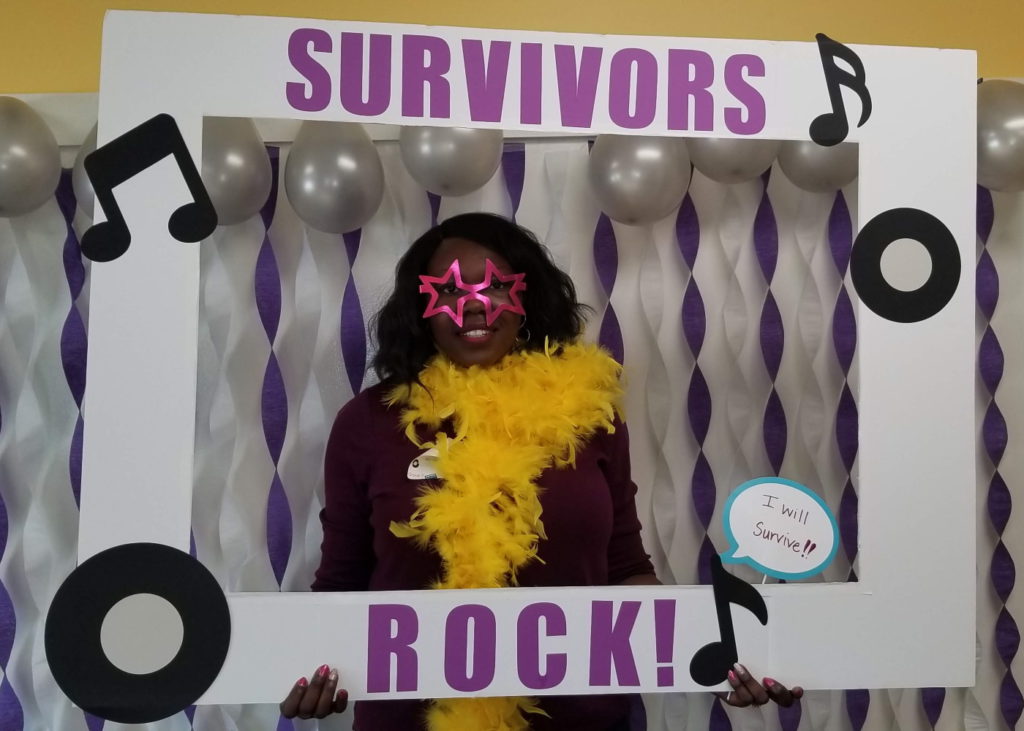

Savoring the small wins

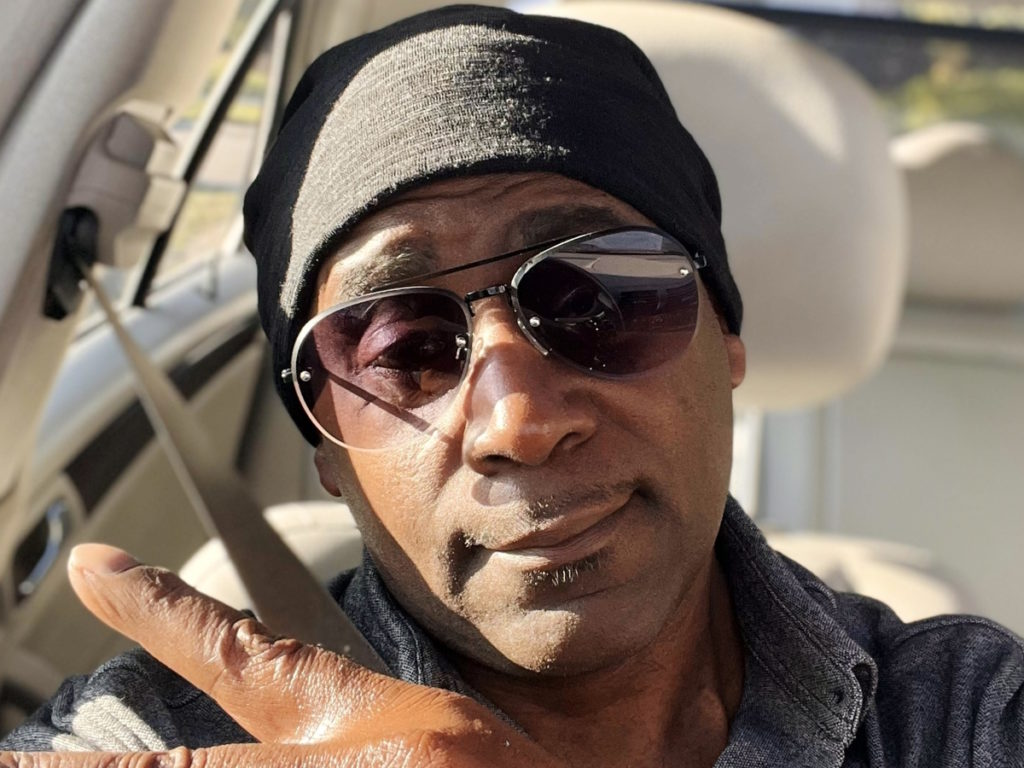

When I started getting little stubble back, I felt good again. It’s funny how that works. You defeat it when you lose your hair, but when it starts growing back, you are so excited. Even if I didn’t have a lot of it, I was happy that it was coming back. It was like a victory.

It’s these small victories you have that you start thinking, I’m getting better. Cherish those moments because any moment that you can have and savor is a win for you.

Post-chemotherapy PET/CT scan

At the end of R-CHOP, Dr. Boles gave me a couple of months off. When I started feeling well, I jumped right back on the bike again. I was feeling good about myself. I thought, “Maybe we won.”

When I had that PET scan, he brought me back in and said, “Well…” I knew. He said, “We’ve got a couple of concerning areas.” I said, “Maybe they’re dead cells, just not giving up.” He said, “No, I don’t think so.”

At that point, I said, “Okay. I got to re-engage.” Dealing with cancer is a battle of engaging and re-engaging. For that brief month or two, I disengaged. But when he told me I had some trouble spots, I had to re-engage all over.

Relapse

Mentally, that was challenging. You have to have a counselor or someone to talk to. I started journaling and I would talk to myself a lot. I would talk to my body and my cells.

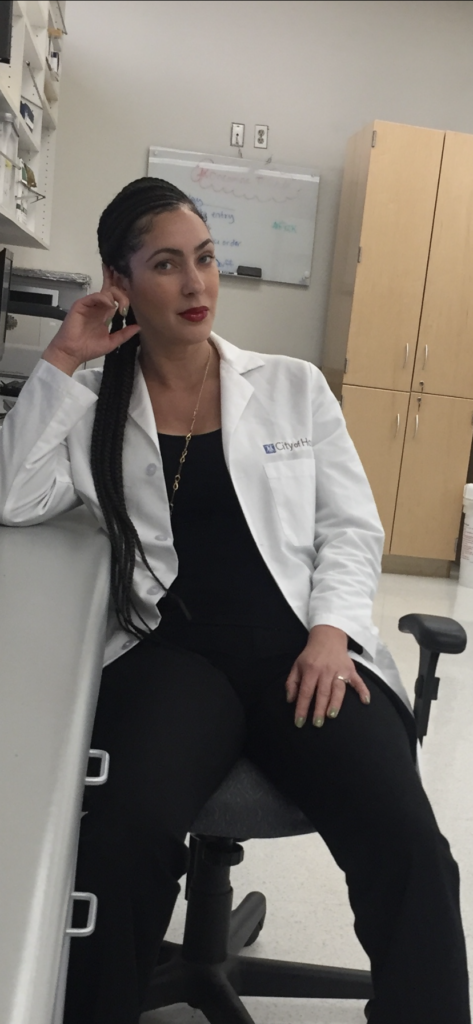

He said, “I’m going to send you to the big house, UNC Chapel Hill,” that’s where the teaching hospital is. “I’m going to send you to specialists there.”

He said, “I’ve taken you as far as I can take you, Tony.” [Do] you know how humbling that was to hear a man of his stature saying that? He’s pretty credible. He said, “I’ve got to send you somewhere else, someone that’s better than me.”

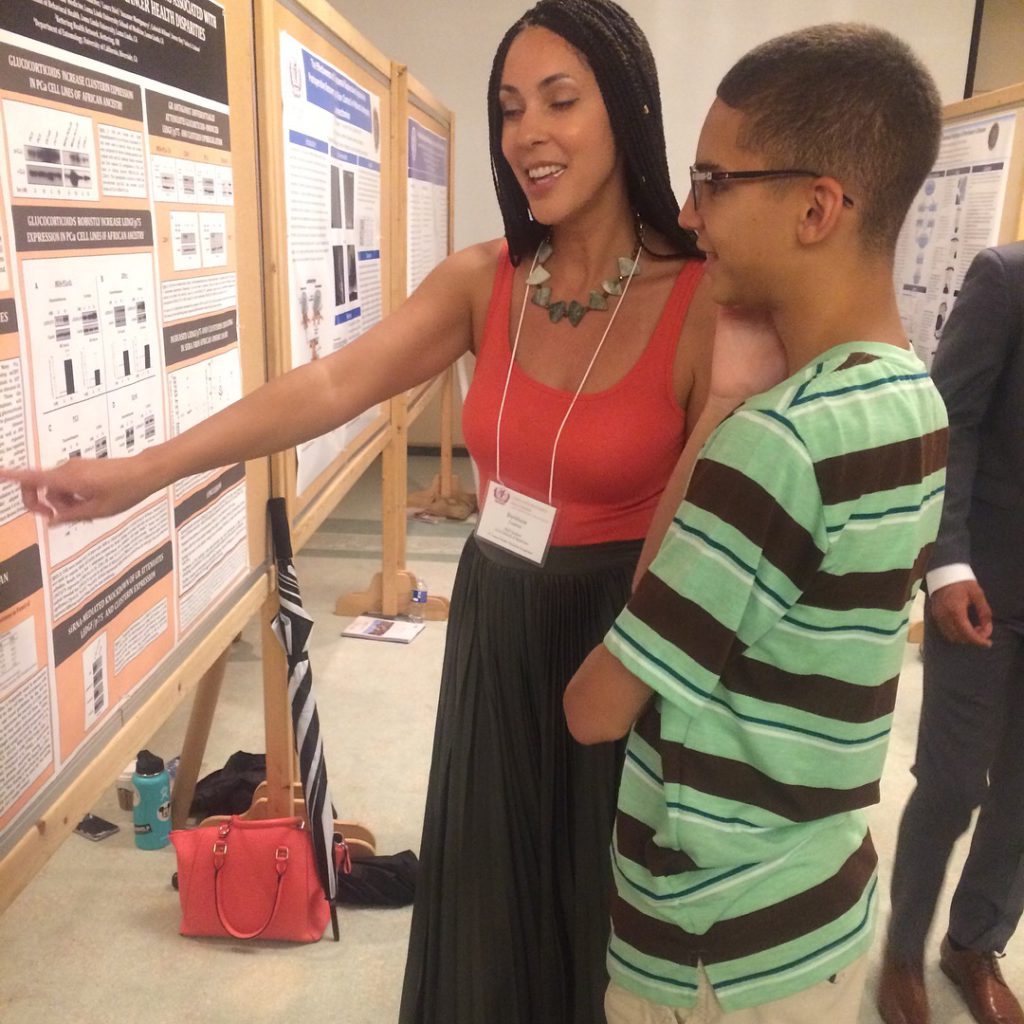

So impressed with UNC, so impressed with them. Again, he gave me options. I said, “You know what? The UNC family has been really good to me.”

When I met Dr. Grover, she was just like him. She was amazing. Later on, she said he told her, “When you meet Tony, he’s not going to look like you think he looks. He’s not going to respond like you think he’s going to respond. Just be ready because he’s going to be the opposite of anything that you’ve ever seen.”

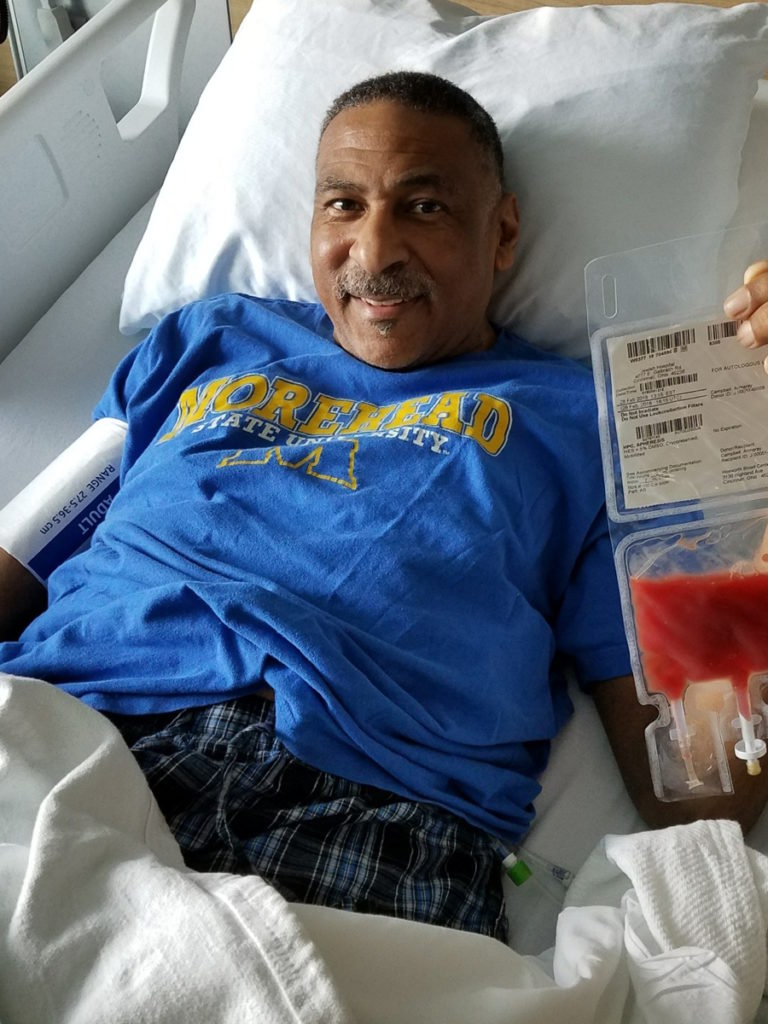

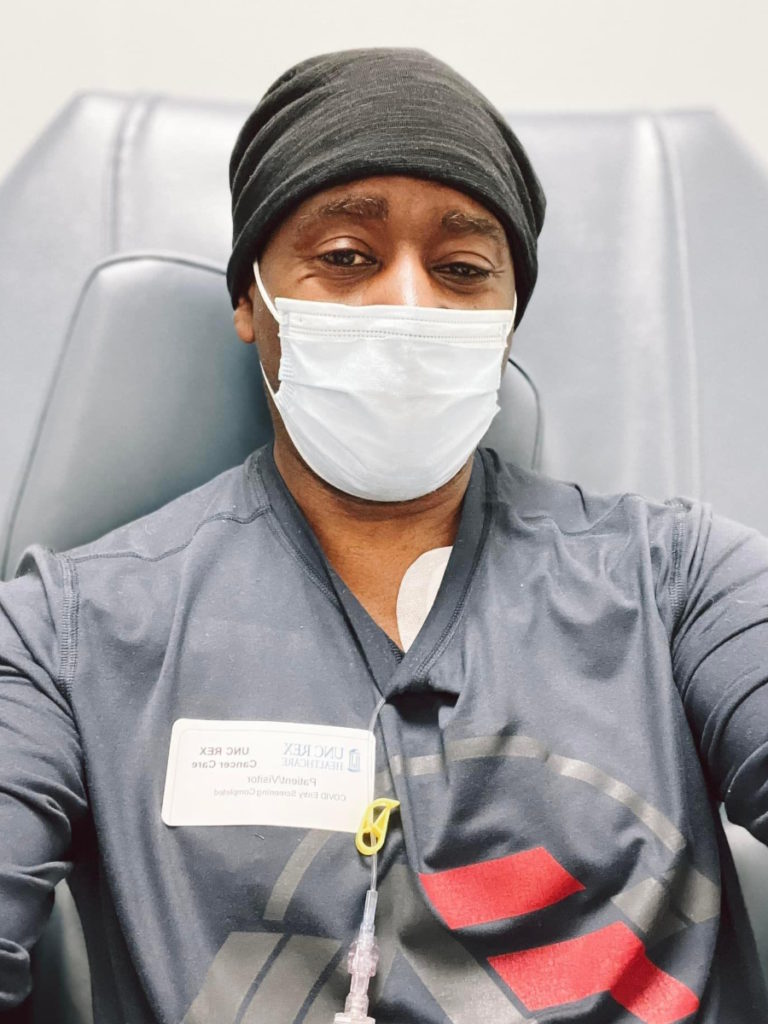

CAR T-cell therapy

Early on, I had mentioned to Dr. Boles, “What about CAR T?” I had done a lot of research. He said, “That’s not available at the time,” cause it wasn’t available to my specific type so it wasn’t an option.

In December 2021, CAR T came online for my specific type. When I got to Dr. Grover, she said, “Tony, I have great news. You qualify for it,” so that’s what pushed us into CAR T.

» MORE: What is CAR T-cell Therapy?

The appeal of CAR T-cell therapy

I knew my body needs a break from chemo. That was not going to be an option.

I was very interested in CAR T from a scientific standpoint — taking your cells and modifying them to specifically attack cancer. That’s pretty ingenious.

Cancer is a very smart cell itself. It can change and evolve. Initially, your T cells will jump on it and eradicate it, but cancer will evolve and say, “We’re going to trick you. We’re going to change our makeup so you don’t recognize us,” so the T cells just come cruising right on by it and cancer can still proliferate. I thought it was interesting how they would reprogram ourselves to recognize the tip [of] the cancer.

I said, “This is if insurance would pay for it.” That’s the main thing. They said yes and that’s how we did CAR T. No other options. I wanted to do that one.

Doing research to help with treatment decisions

You have to do an honest assessment of how you’re feeling coming out of this. Chemo can be rough. If you feel like your body can’t handle that, seek second opinions. If your body’s telling you it can’t handle any more of this, it can’t. You may need a break if you can afford to have a break. But if there [are] other opportunities, make sure you understand what they are.

If you don’t feel right and you don’t feel good, you can’t continue down that path. You have to have time where your body can gather itself. That’s what I encourage more so than anything.

Understand your body and understand how much more of this you can take. Pay attention to what your levels are and how your organs are responding and that will tell you what your course of action should be. You have to make sure everything is at a place [where] it could handle another round or another series of chemo.

You have to ask yourself: how am I feeling physically? If your doctors say you’re at a point [where] we’re not as concerned with it spreading rapidly, pause a little bit just to get your mind and body back together so you can engage again. That’s what I would encourage, more so than what treatment you’re seeking.

Don’t be so quick to rush into one treatment, into the next, into the next because that degradation would take place in your body at some point.

Just the word practicing medicine is exactly what it is. It’s practice, unfortunately. They do the best they can through what they’re dealing with, their education, and what they’ve been exposed to, but it’s still practicing medicine.

Holistic care in conjunction with cancer treatment

I found a holistic doctor so I was doing holistic medicine in conjunction with chemo. I was researching holistic doctors in other countries that may not have the scientific approach as developed countries. Some of them rely on Mother Nature who provides us with everything that we need, too. I started looking at plants and herbs that can help me detox.

As quickly as you can detox chemo and chemicals out [of] your body, the more readily your body will be if you have to do it again. I was looking at different options to detox myself outside of traditional medicine.

You don’t want to just keep adding chemicals to your body. They give us chemo then they give us these other pills to help with this and that. But sometimes, Mother Nature gives you that and your body is readily absorbing that versus the tablet.

I would tell them what I’m taking because some of that may affect chemo. Chemo is strong and designed to do what it does. Sometimes you can alter how it works by taking some of these things.

Don’t be a renegade. Do these things in conjunction. Make sure you let them know what you’re taking and then they can tell you. Some things he would say, “I don’t recommend that,” then he will tell me why and it would make sense. Seek other opinions but also validate that versus what you’re already doing. You got to have that balance.

When I would throw all these things at him and he didn’t dismiss me, that’s when I knew he was the doctor for me. Your physician and your team matter. You have to feel good about them. If you don’t feel good about them, find someone that you do. They affect everything about your situation.

If you don’t feel loved or feel like they care, then with the treatment that they’re giving you, you’re not going to have confidence in that. Make sure you feel good about them.

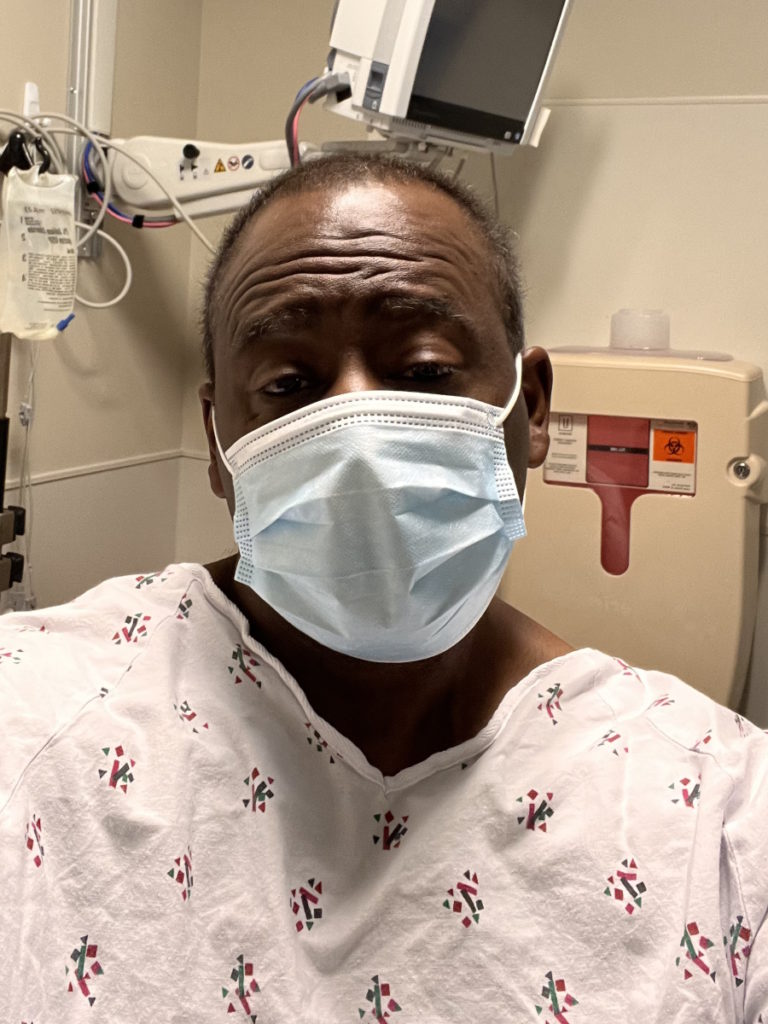

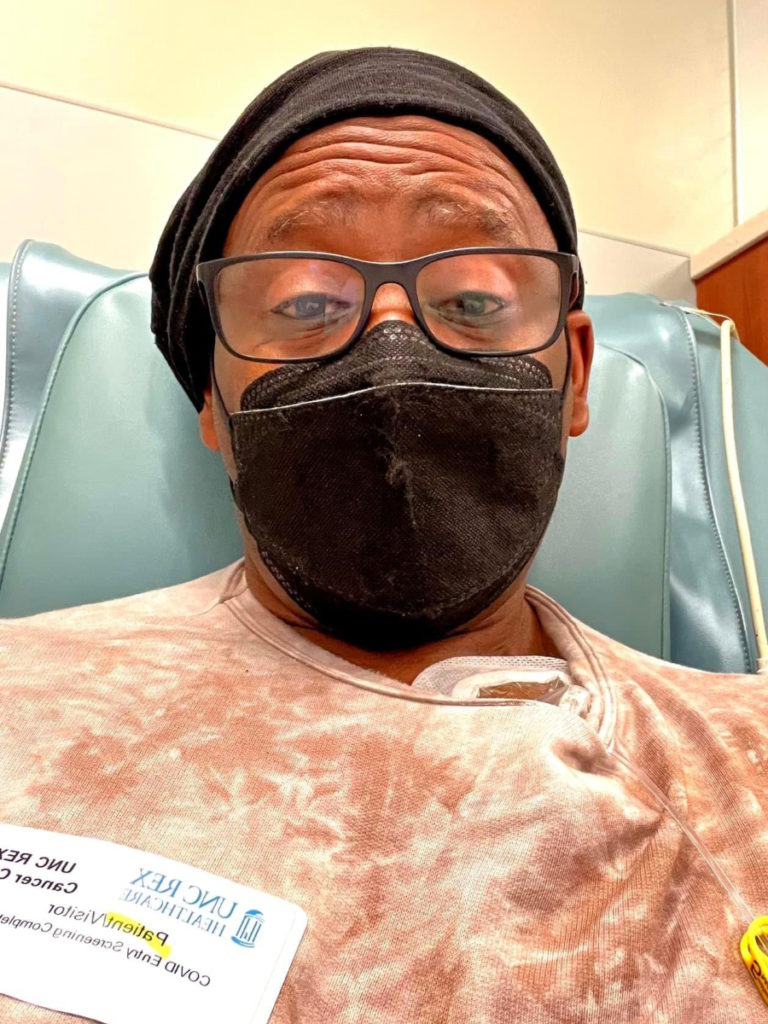

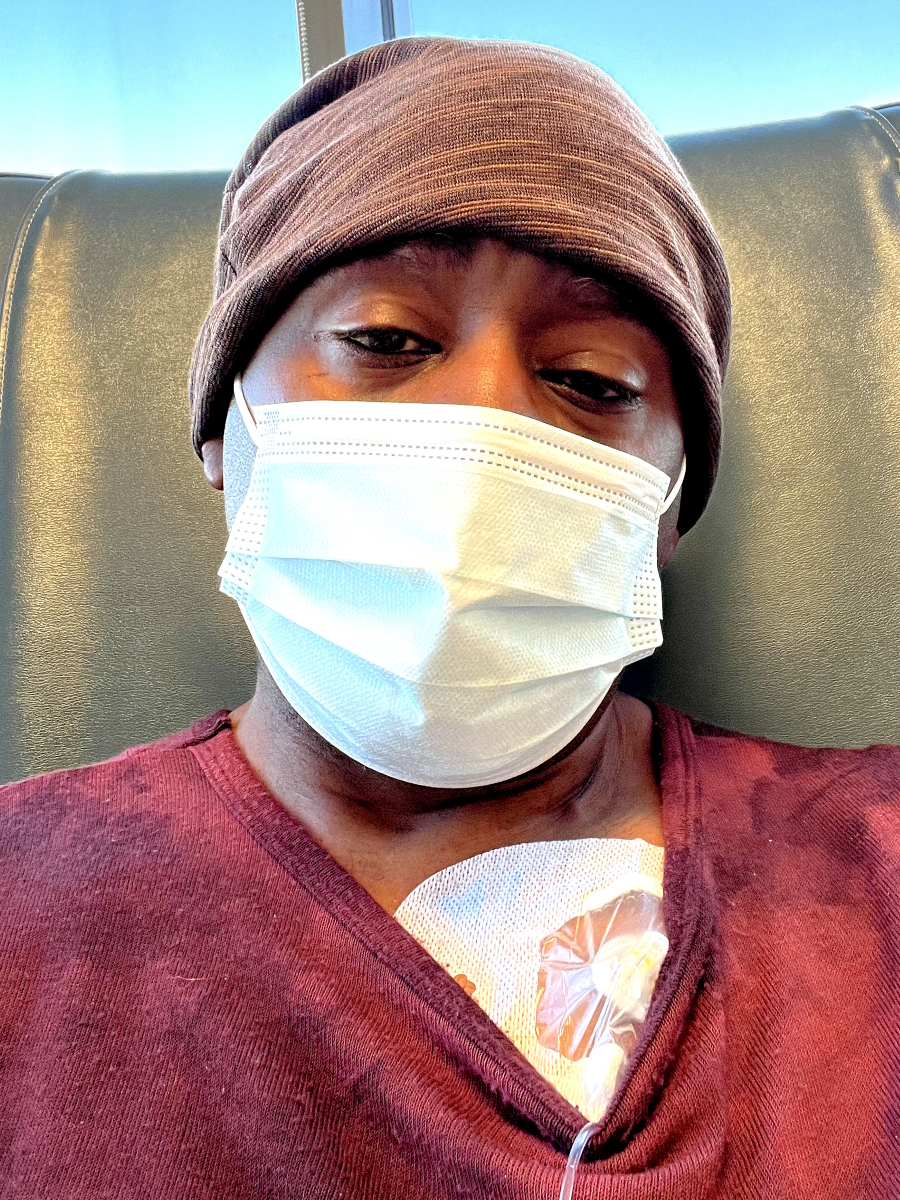

Preparing for CAR T-cell therapy

CAR T was my most difficult time simply because I was just so uncertain. I was saying to myself, “Okay, I went through R-CHOP. What if CAR T doesn’t work? What’s better than that?” For a moment, my mind would go dancing.

The chemo depletion was very hard for me. They take you to the edge. I had three days worth of chemo depletion.

When you’re sitting there, you can be full of life and your eyes could be all bright and bubbly. But when that chemo starts coursing through your veins, it’s almost like a dimness comes over your body and you can feel an extraction of life just coming out of you. It’s like getting close to death.

Chemo depletion is exactly how it sounds. They depleted my body to the point that there was nothing [so] that it would accept those CAR T cells.

The first day hit me so hard. I went through six rounds of R-CHOP and I didn’t feel like that because they would always give me something to try to bring me back. They would give me the white blood cell shot and help me boost myself back. But this time, [there] was none of that. I could feel like my essence leaving me after that first day.

You had to be within 15 minutes of the hospital. I live an hour and something away so I had to move up there. I stayed in a SECU House, which is like a Ronald McDonald House for grown-ups.

They took me through the back entrances of the hospital to get to the CAR T center because you had to be away from people. You had no immune system at that point.

I always would pass the chapel going up. [On] the second day, I went in and broke down crying. I said, “Lord, I can’t do this.” It drained me so bad I felt like I couldn’t do anymore.

I sat in that chapel [for] about 5-10 minutes. Then I got up, dried my tears, sat in that chair, and had my second day. I did the same thing [on] the third day.

I stayed at the SECU House and started my rehab and recovery. The people there were great. They cook for you, you meet other cancer patients in [the] same situation, and you realize that there [are] a lot of people in worse situations than you.

Nurses call me Zeus at the hospital. At the SECU House, I saw people fighting for their life and I’m walking around like I’m going to a training camp somewhere.

Typically, you have to be there [for] 30 days depending on how you respond and you have to go to the hospital every day for labs. [In] my first seven days, I had no symptoms. I was feeling great.

I was sitting there talking to my CAR T cells and said, “You guys are my special forces.” Every night, every day, I would check in with them and say, “Hey, what [are] you guys doing?” They’ll say, “Executing. Executing, boss.”

I would talk to myself like that literally. I thought, “Execute. Go into the highway and the byways in my body and find cancer and kill it.” I was just talking to my body.

After the seventh day, my head nurse said, “You’re doing so well. We’re going to let you go home.” This was a Wednesday. That Friday, I got super sick, wound back [in] the hospital, and stayed for 10 days. My doctor was joking, she said, “You [were] my little superstar and you wound up back in here.”

I didn’t have any other side effects. I was lethargic for a while. The fever was the only thing that showed up. After they determined how to get that down and I actually broke it, they let me go back home and I’ve been home ever since.

Post-treatment scan

I finished the CAR T in December 2022 and had another PET scan [in] January 2023.

We found some cells, but I told Dr. Grover the same thing. I said, “Maybe they’re dead.” She was the same way, “I don’t think so.”

I was very discouraged because I put a lot of faith in the process. But all hope wasn’t lost because we were unsure.

The spot that I still had resonating was in the original area. It was very difficult to get to so she wanted to do a biopsy. They went through my hip to get to it. They took 16 to 18 samples and they were decent samples that we could tell what’s what.

Miracle moment

If you believe in miracles, I would say this is a miracle moment. When I met with Dr. Grover [about] the results, she said, “Tony, it looked like someone had pinched it.”

If you can imagine pinching your cell, smashing it, and just excreting everything in it, like you squeezing something really, really tight, that’s how that cell looked. She said, “The report said no lymphoma found.” I thought, “That’s a miracle, right? That’s a miracle.”

But doctors don’t deal in those terms so they’re not going to say certain things. They’re not going to give you certainty or anything because they don’t know. But we both were smiling. No lymphoma found. It was inconclusive.

I have another PET scan to prove whether or not those cells were active, dead, or whatever they were. We will know more.

I had another moment of victory. Typically, when they give you that report, it’s a whole page. When the radiologist gave the report, it was only five lines. That’s all he said. It looked like this and no lymphoma found so that was a win for me.

At that moment, I didn’t want to talk about the what-ifs because now, my faith is renewed again. I’m engaged.

I’m telling myself, “When we have this next PET scan, it’s going to reinforce what we already thought. Those cells are going to be dead.” That’s what I’m saying to myself.

Now, what if it’s still there, right? But it’s the same what-if that we had before. We never did targeted radiation, stem cell transplant is still on the table… A whole lot of stuff is on the table because of how my body responded. My organs are super healthy so they feel confident that I could withstand something if we had to.

I ask my body to respond every time I get knocked down. I think that’s just my faith. That’s the promise that I believe, that I hold on to.

A lot of times, it [doesn’t] have to make sense to a lot of people. It just has to make sense to you because that’s what’s keeping you going. If you’re putting your faith in that, that’s what’s keeping you going. I don’t care what nobody else thinks. Eliminate the background noise.

Words of advice

You have to cry. Go somewhere alone. I was alone, out in nature, crying, [and] talking to my mom. You can’t do that amongst other people. There are moments for that.

You need to have that alone time so you can get yourself prepared for what’s to come. It’s going to help you because it makes them stronger.

Listen to what your body is telling you

Get checked. Do your yearly checkups. Go beyond that. Get your blood analysis done. Take more control of your health.

Sometimes if you feel pain, it’s for a reason. Just go get checked out. I was one of those ones that, “I don’t need to go do that. I know what to do. I’m just going to put some ice on it. I’m going to get a massage. I’m going to do this.”

Go get checked because sometimes, there are things going on in your body that you can’t see that need to get checked. For all the athletes, for mom and dad sitting on the couch, your kids, get checked out and go a little further.

Sometimes the basic check is not enough. Add extra to that. Get your prostate checked if you’re a man. Get [a] mammogram if you’re a woman. Get the blood test done so you can see what’s going on in your body. Those things matter. I would definitely do that over because I didn’t do a great job of that at all.

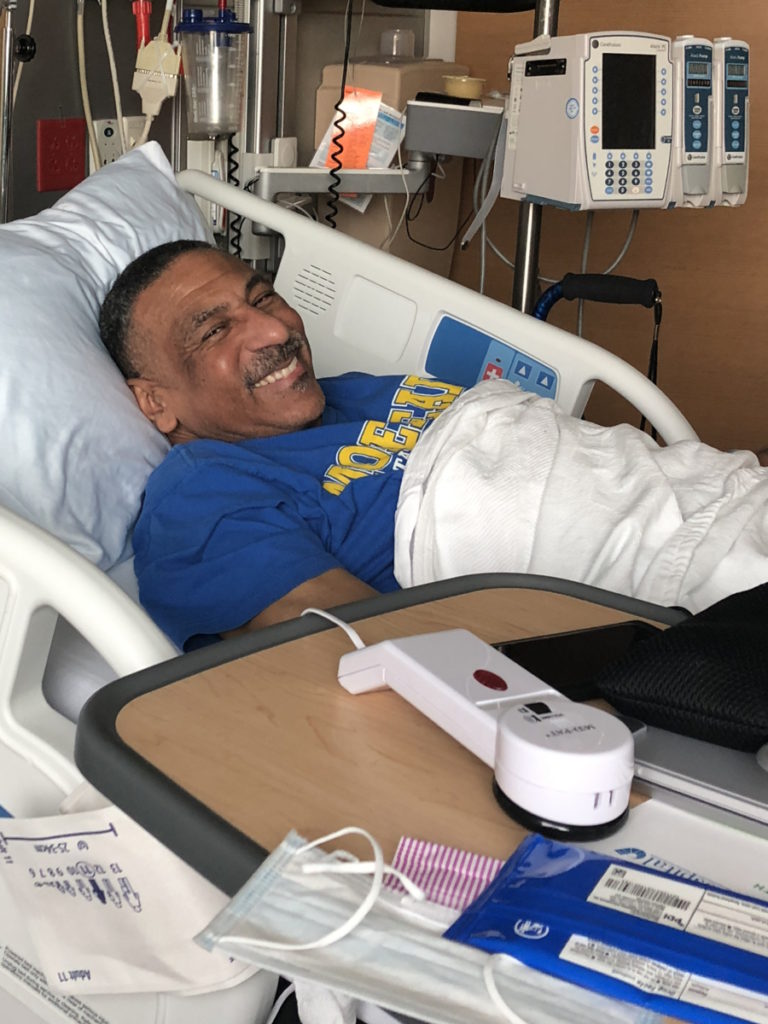

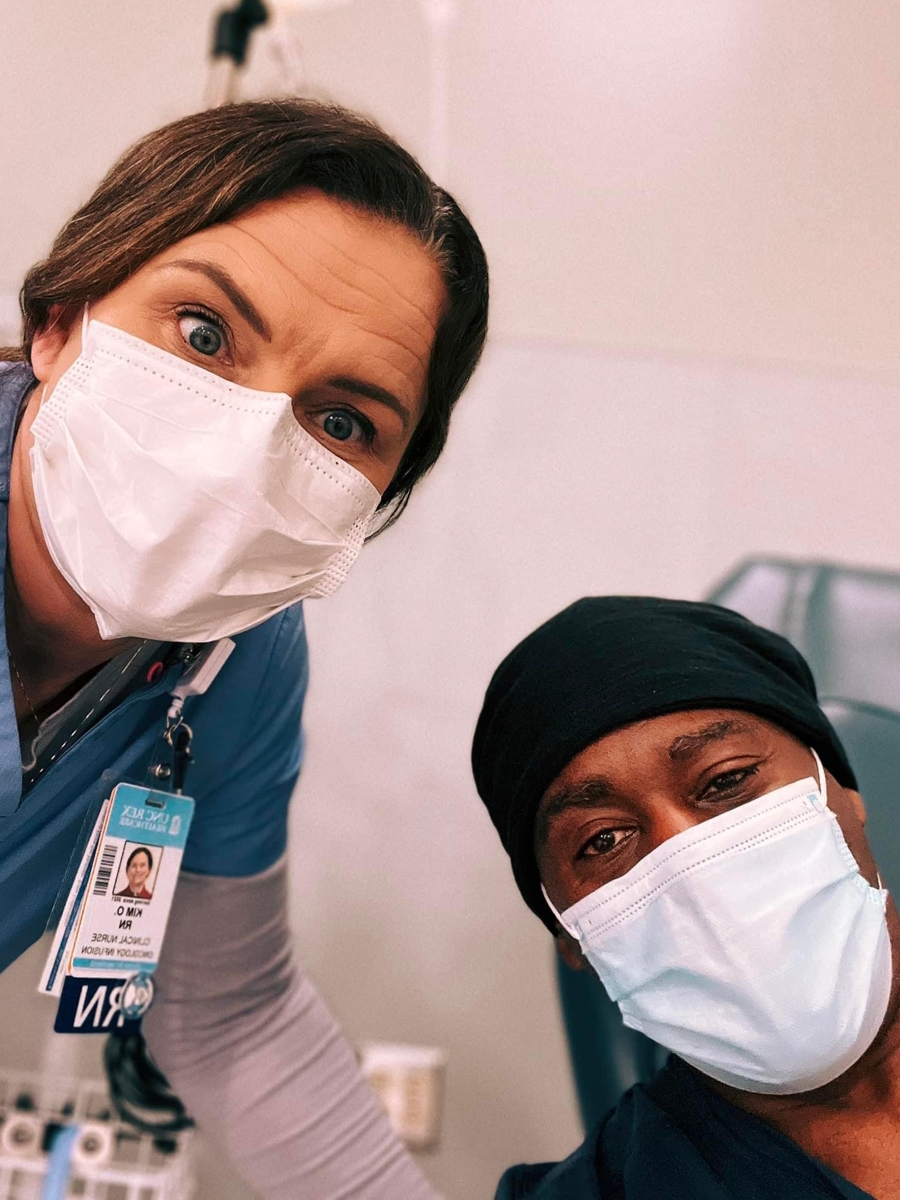

Make the most of your hospital stay

I made a lot of friends in the hospital. Try to make the most out of it. The nurses and I would have fun. I used to tease them all the time.

You would think, I’m here for my care. They’re giving me chemo. They’re taking care of me. Then they ask you if you’re hungry and they give you some cookies. Like, “What? Cookies? Where [are] the oranges and apples?” They give you all this stuff that you shouldn’t be eating.

I had a good time. I bonded with my team doing R-CHOP. I am thankful for every nurse because they are doing God’s work. It goes unappreciated [and] devalued sometimes, but they work long hours and they legitimately care for you.

That is your frontline. You’re not going to see your oncologist in there with you. You’re going to see the nurse and you’re going to see them all the way through the end. Don’t be nasty and bad to your nurses. Love them. Encourage them.

I would do little things for them just to give them a ray of cheer because they’re taking care of me and they’re breathing life into my situation. They’re making sure I’m taken care of and I appreciate that. You got to appreciate that.

Cancer is bigger than you

This is bigger than you. Why are you in it? It’s not all about you. It’s bigger than us. When you help other people and pour into other people, it will come back to you. The more you give, the more you will receive.

You have to be selfish to protect yourself while you’re going through this, but you also have to accept that maybe [you] can help somebody. Maybe I can do something. Maybe I can [make] a difference in somebody else’s life while they’re going through this. Maybe I can volunteer at the cancer ward.

Keep yourself engaged not so much on your situation but think about someone who’s doing worse than you.

My biggest impact was when I stayed at the SECU House and I saw so many people that were worse than me; that encouraged me. People that could barely move were cooking breakfast for us, making lunch and dinner for us. They were giving back. In spite of their situation and no matter how they felt, they were willing to give back.

I said, “My life will not be the same. I’m going to give back. I can’t wait till I get some clearance runway.” We’re at the hospital a lot dealing with this. I can’t wait till my doctor says, “You don’t have to come as often. We’ll do it every quarter.” That gives me more time to get activated and start doing stuff because people need that.

Have faith

Sometimes, you just take [the] faith that you have. Faith is something that you really can’t see, so you’ve got to put it in something. Either you’re going to believe in a doctor or you’re going to rely on your faith in God. I chose to rely on that and held on to that

As a result, every time I get low [and] feel like I can’t make it, I just recall that. I’m hoping and believing in the outcome that I want to see happen.

I encourage everybody [to] grab faith and believe because that’s where the battle starts. It starts right [in the mind]. Physically, you can do all you can, but if you lose the battle [in the mind from] the very beginning, you’re fighting an uphill battle. Now you’re battling your belief that you can even be healed from this or that you can be cured from this.

When you can look beyond your situation and into somebody else’s life and try to help them, it will help your situation. It’s that faith — believing in something strong enough that you know the outcome of this end will be for you.

My wing is being fixed so I can fix somebody else’s wing and say, “You know what? At one point in time, I had a broken wing, too.”

We have our tribe. When we move and make an assault on this, together is so much better than going lone wolf. You got an army behind you so it’s not over.

Stay steadfast, everybody. It may seem difficult. It may seem bleak at times, but stay steadfast. Don’t let outside sources influence you. Stay steadfast even in your darkest moments.

Listen to The Patient Story. That’s what I did. One of my favorite stories was Nina. Those are the things that get you by.

We all have our faith, but sometimes you got to put your hands on something. You have to put your eyes on something so guard what you see [and] protect what you hear.

Inspired by Tony's story?

Share your story, too!

Special thanks again to Genmab & AbbVie for their support of our independent patient education content. The Patient Story retains full editorial control.

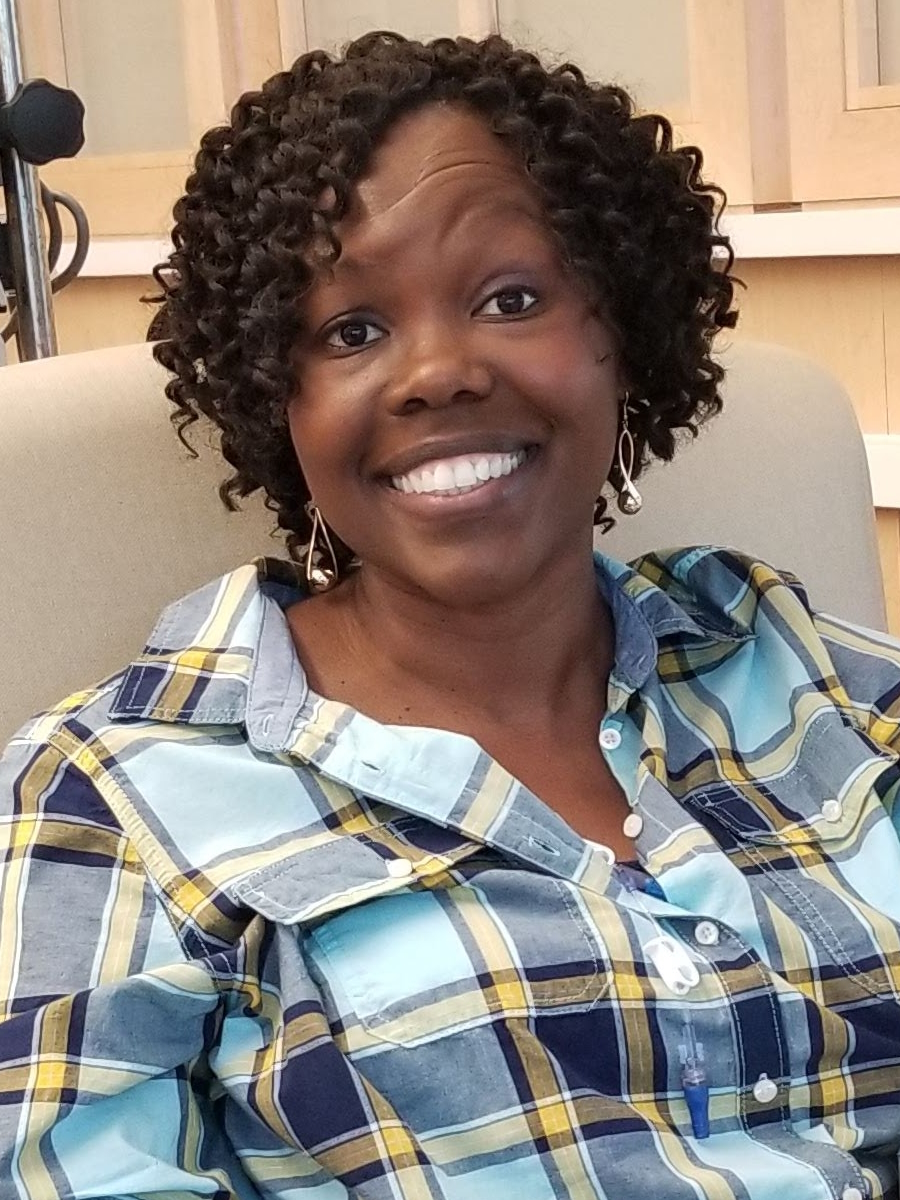

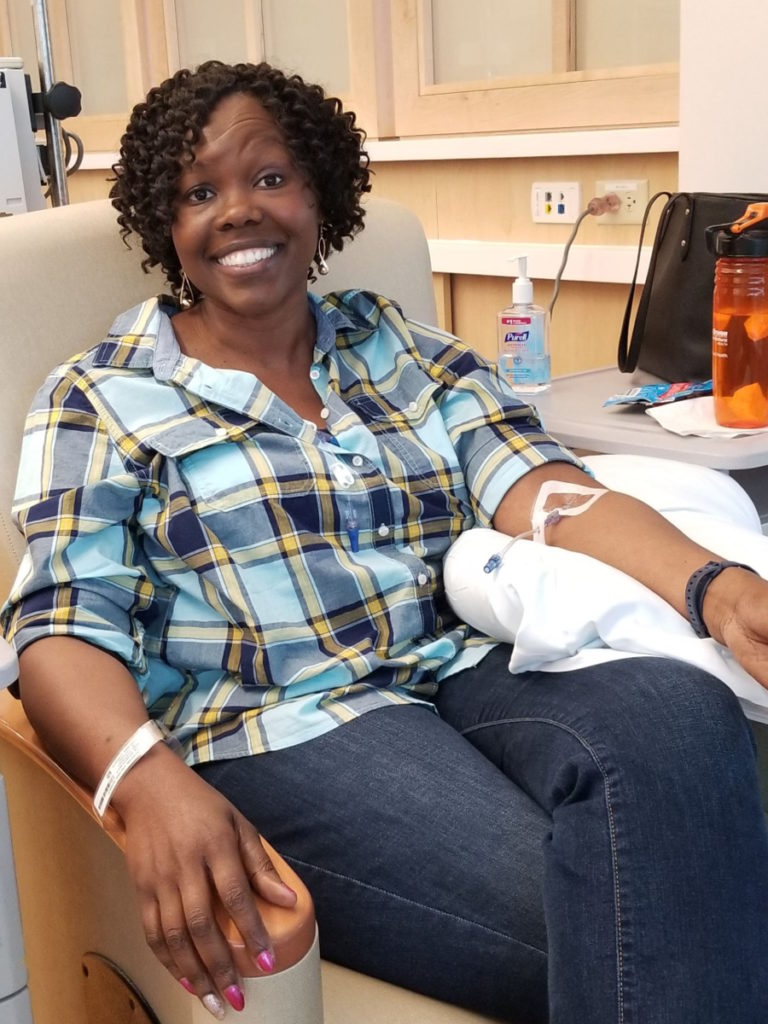

DLBCL Patient Stories

Mike E., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Persistent, significant back pain

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy

Don S., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Symptoms: Weight loss, fatigue, enlarged lymph nodes

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy (epcoritamab)

Michael E., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Symptoms: Back & leg pain, rash, severe itching, decreased appetite, weight loss

Treatments: Chemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapy, clinical trial (no improvement from study drug), immunotherapy (epcoritamab)

Barbara R., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Abdominal and gastric pain

Treatments: Chemotherapy R-CHOP, CAR T-cell therapy, study drug CYT-0851