Navigating the Sweet and Bubbly as a Cancer Patient

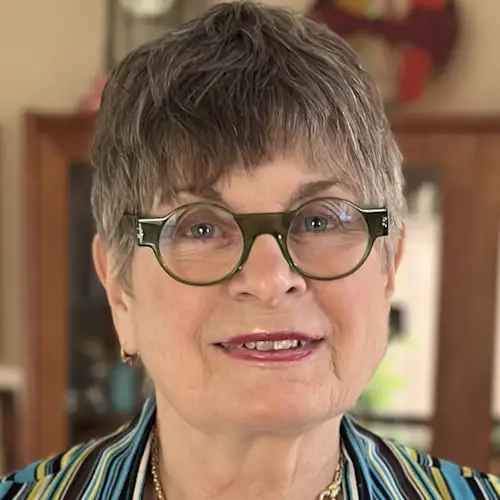

Dr. Urvi Shah Shares the Impact of Sugar and Soda on Cancer Patients

As you navigate your cancer journey, questions about diet often bubble to the surface. Dr. Urvi Shah, is a board-certified hematologist-oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering and a Hodkin lymphoma patient. Dr. Shah led a clinical trial studying the effects of a plant-based diet on cancer patients. She sheds light on the relationship between sugar, soda, and overall diet. In this interview, Dr. Shah provides insight into the effects of diet on cancer.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- Do diet sodas increase the risk or progression of cancer?

- Should sugar be avoided to reduce cancer progression and risk?

- What is the daily recommended amount of sugar?

- How can patients reduce their refined sugar intake?

- Do you think there is a gap between what patients and doctors are taught about nutrition and cancer?

- Can you tell us about the trial studying the effects of a high-fiber, plant-based diet on mGUS?

- Can healthier eating and weight loss reduce the risk of cancer progression?

- What were the effects of a high-fiber, plant-based diet on microbiome diversity?

- Did this diet delay the progression of cancer?

- How can people diversify their microbiome?

- What are some tips for improving one’s diet?

- More about cancer health and wellness

Do diet sodas increase the risk or progression of cancer?

Dr. Shah: When we talk about artificial beverages or sugar-sweetened drinks, there’s also been a lot of data around aspartame and some of these things in terms of drinks. The data is a bit mixed, where the recent findings from some groups have suggested that it might be a carcinogen, and others have said that the data is not enough to call it that. I think irrespective of whatever that is, drinking those drinks has not led to patients actually having a lower BMI or losing weight in itself. I think that overall, trying to avoid either artificial or sugar-sweetened beverages is important.

Whether sugar feeds cancer is a very common thought that patients propagate.

Dr. Urivi Shah

Should sugar be avoided to reduce cancer progression and risk?

Dr. Shah: Whether sugar feeds cancer is a very common thought that patients propagate. I think the answer is somewhat nuanced or lies in between. When we think about sugar, sugar is a refined carbohydrate.

Carbohydrates, in general, are a food group that we shouldn’t be excluded just because we are worried about the risk of cancer. There are complex carbohydrates, like whole grains, that are actually associated with reduced cancer risk in many population studies. It is important to include complex carbohydrates in one’s diet and not think about excluding those.

Simultaneously, refined carbohydrates like sugary drinks, sugar-sweetened beverages, those are associated with inflammation, insulin resistance, obesity, and risk of cancer. I think that when we’re thinking about sugar, yes, we want to limit the sugary drinks, the processed foods, the cakes and cookies, and things like that and reduce it.

What is the daily recommended amount of sugar?

Dr. Shah: One fun fact is that the US population on average eats about 17 teaspoons of sugar a day. That’s on average, so there are a lot of people much higher than 17 teaspoons. Sugar is something we all don’t really need, like refined sugar. Even if we were, the recommendation would be to limit it to 6 to 9 teaspoons – 6 for females and 9 for males – per day. We’re almost 3 times above that limit already on average. You can think that many people who are way higher.

How can patients reduce their refined sugar intake?

Dr. Shah: A lot of sugar comes in hidden foods and you don’t realize it. Cereals and things will have a lot of added sugar. It’s important to learn how to read labels and try to at least not be eating the added sugar or the refined sugar. I would not avoid complex carbohydrates because they come with the fiber. They come with vitamins, nutrients, and other things that are actually quite health-promoting.

Do you think there is a gap between what patients and doctors are taught about nutrition and cancer?

Dr. Shah: Through my experience, I did realize that I had a lot of friends and family members trying to tell me what to eat and what not to eat. I realized that we, as oncologists and even medical professionals, don’t hear enough about this in our training, and we don’t even study this properly. It became a side hobby of mine, as you might say, where I would read about these topics quite often and found it really fascinating that there’s so much literature out there, but we’re not really translating it directly for the patients.

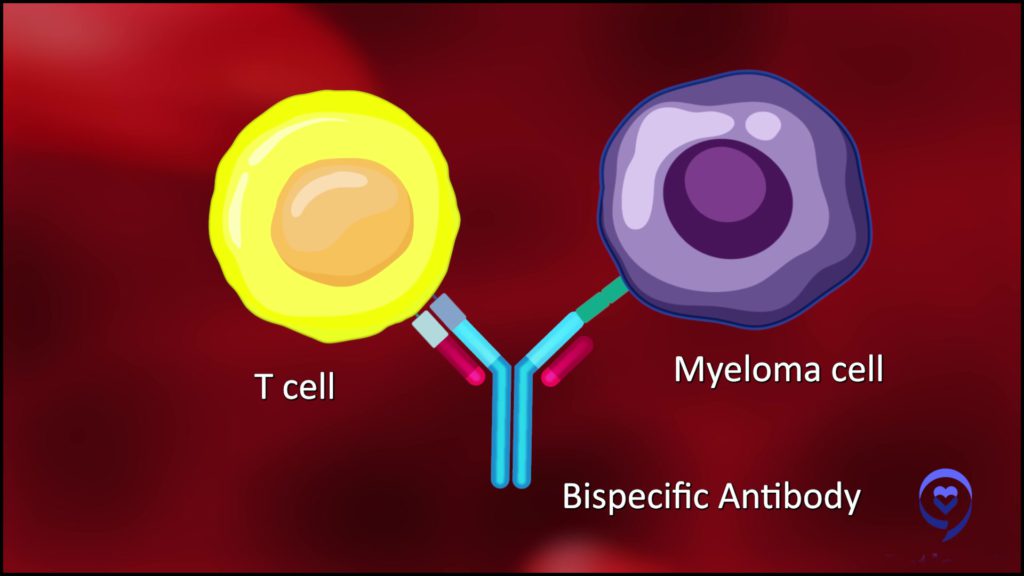

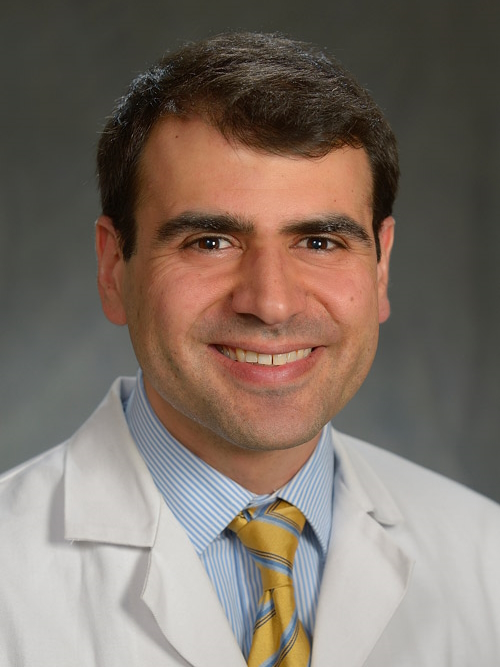

I never really thought about how I could merge this side hobby with my professional career. I did a lot of research in genetics, epigenetics, immune therapies. Then when I moved to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, first as an immunotherapy fellow and then as faculty, I actually was doing more work in CAR-T cell therapies and bispecific therapies, so different kinds of immune therapies.

Can you tell us about the trial studying the effects of a high-fiber, plant-based diet on mGUS?

Dr. Shah: Given my interest on the side, I always knew I wanted to do at least one trial in this area and see where it goes. When I started as faculty, we developed a new prevention trial. This trial was basically looking at a high-fiber plant-based diet and the effects on mGUS or monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance and smoldering myeloma. Can this delay risk of progression to multiple myeloma, a blood cancer?

We do know that these precursor disorders of mGUS and smoldering myeloma increase the risk to develop myeloma, and they’re pretty common in the general population of over 3% in people over the age of 50 years. It’s not that uncommon, but we don’t recommend checking this for everybody. Once patients are checked, they are a bit anxious to know, what do we do about this? The standard of care currently is observation, meaning we do nothing until it does become a blood cancer.

Can healthier eating and weight loss reduce the risk of cancer progression?

Dr. Shah: We do know from other studies that have looked at associations, that people who have an elevated body mass index (BMI) are twice as likely to progress to myeloma than somebody who has a normal body mass index. We already know that the risk is doubled with just BMI. What we don’t know, and we have not studied so far was, if we help patients lose weight and eat better, will that risk reduce for patients?

What we saw was that patients actually had a reduction in body mass index of about 8% at 3 months, and they were eating to satiety.

Dr. Shah

Can you explain the study’s methods?

Dr. Shah: The premise of our study was looking at a 3-month, high-fiber, plant-based diet. We shipped the patient’s lunch and dinner. We also provided them snacks and breakfast ideas and we had a dietitian working with them very closely for 3 months.

Then we had 6 months of coaching total – 3 months during the intervention and 3 months after. We followed them for a year on the study. This was our first study, so it was only a 20 patient study looking at feasibility to understand is it possible to do this intervention? Does it have any effects on weight, on compliance, and can patients do this?

What were the results of the study?

Dr. Shah: What we saw was that patients actually had a reduction in body mass index of about 8% at 3 months, and they were eating to satiety. We did not ask patients to calorie restrict, because I think it’s important that we don’t focus on what we can’t eat, but focus on what we can and eat till we are full. We had patients eat as much as they wanted, as long as they were eating high-fiber, plant-based foods and unprocessed foods. Despite that, patients with an elevated BMI were able to move their BMI towards a normal BMI.

With this weight loss, we also saw an improvement in compliance very significantly, where the median fiber intake was below the RDA for these patients before the study, and it improved to above the RDA in the study. Meaning, the recommended daily allowance of about 30 g or 25 g.

What we also saw was the compliance. We calculated the percentage of calories that were unprocessed plant foods and we looked at, did this improve over time? We saw that at the start of the study, before the patient started the study, their unprocessed plant food intake was only about 20% of their calories. This is very typical of a standard Western diet, so nothing different than most patients. This improved to 90% on the intervention and even a year after remained high at 70%. We saw that the patients that made the changes were able to sustain them pretty much long term because they saw the benefits.

Across the board, the patients who responded, all of them said if there was another study, they would be glad to participate

Dr. Shah

Measuring quality of life for study participants

Dr. Shah: Another question that doctors and patients ask is, are these changes something that’s feasible? Will a patient be able to do it? Does it affect their quality of life? Do they enjoy it? We actually checked quality of life by serving patients through the study. We actually saw an improvement in global health status dyspnea or shortness of breath and fatigue scores across the time.

We also looked at things like surveying them and said, would you do this study again if we offered it to you? Or, how difficult was the study to do? Across the board, the patients who responded, all of them said if there was another study, they would be glad to participate. We also saw that patients saw an improvement in many different aspects of their health, like self-confidence, body mass index, and some had improvements in arthritis or back pain. There were small changes that helped patients across different symptoms. Overall, just eating better.

Amongst all the patients, they all said that the study was somewhat easy or very easy to follow, but none of them said it was difficult. That was encouraging too, that patients were able to make these changes, and some of them were able to sustain them long term.

Where there improvements in insulin resistance?

Dr. Shah: Other things we looked at, we try to look at correlatives, meaning looking at blood and stool biomarkers that we know are associated with cancer progression. We know things like insulin resistance, for instance, is associated with progression of cancer. We saw that insulin resistance actually improved on the study despite these patients eating more carbs than ever. But because these are complex carbohydrates, there was actually an improvement in insulin resistance.

We had one patient actually on insulin for 30 years and was able to stop it within a month on the study and now 2 years out, has not needed insulin again. It is possible for patients to reverse some of these metabolic disorders and actually feel better with time.

What were the effects of a high-fiber, plant-based diet on microbiome diversity?

Dr. Shah: We also saw an improvement in the microbiome profile. If you’ve followed a lot of cancer data on the microbiome, one common theme pops up every time. That theme is that higher microbiome diversity – meaning many different kinds of bacteria in the microbiome, so a variety. If you think about a healthy rainforest compared to a forest with just palm trees, the healthy rainforest, or the one with microbiome diversity, is what’s associated with improved progression-free survival and overall survival over and over again in different cancers.

We have not yet shown in a population that has a precursor to cancer, can we really, with a dietary intervention, improve this diversity and sustain it? In our study, we saw that within 3 months patients had an improvement in their stool microbiome diversity. We also looked at it from baseline to 1 year and it was sustained improved. Even though the intervention was only 3 months, we still saw the benefit at a year because these patients were continuing to keep at least some of these changes going.

Were there any changes in inflammation?

Dr. Shah: Other things we saw as we looked at changes in inflammation, we saw some improvement in some subsets of the immune cells as well. We’re doing a lot of more detailed analysis with these samples and hoping to put it together as a paper in the next year. We presented some of the findings at the American Society of Hematology meeting.

Did this diet delay the progression of cancer?

Dr. Shah: The last question many would ask is, all these are good in terms of biomarkers, but did it really delay the progression of the cancer? These were 20 patients so it’s a small study and some had really small low level disease. We can’t expect in a year to see changes in such low level disease for patients.

Otherwise, there were other patients, 2 of them who had rising M-spikes. So for the past 5 years, their M-spike had slowly been increasing. What we did see is on the intervention with the weight loss and the dietary changes, their M-spike, or the protein that we follow for the disease or the plasma cell disorder, had stabilized. So for these 2 patients who actually lost more than 10% body weight over time and also maintained the dietary changes, we saw a stabilization of their disease that was rising for 5 years before.

We calculated significance with p values before and after and we do see a change in the trajectory of the disease. I think that diet and the microbiome, insulin resistance, and all of these things can make a big difference in cancer risk and progression. I think we’re just trying to learn a lot about this and bring it to patients.

How can people diversify their microbiome?

Dr. Shah: If we think about microbiome health, gut microbiome health, like I said, the theme that pops up is diversity. Having a diversity of bacteria. If you’re thinking about diverse bacteria, think about each bacteria needing different foods to survive. You want to eat a diversity of food because that feeds different bacteria.

Dr. Shah: There’s been a study with over 10,000 stool samples from 10,000 individuals and they looked at who has higher diversity compared to who has lower diversity based on the foods they eat and this was healthy individuals.

I don’t see why what’s in healthy individuals shouldn’t at least somewhat apply to patients with cancer. But what they saw was that patients who ate more than 30 types of plant foods per week, and when I say 30 types, I’m not talking about broccoli 30 times. I’m talking about broccoli, chickpeas, red beans, pinto beans, herbs, spices, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and all of those things. 30 different types of them, compared to those who ate less than 10 plant foods per week, had an increased diversity of their microbiome.

What are some tips for improving one’s diet?

Dr. Shah: I think one very quick thing that patients can think about implementing is how do you go outside your comfort zone and buy different plant foods that you may not be comfortable eating or used to? Not just eating the same sides of broccoli or potatoes or something that you’re used to, but trying different things.

I do think that taste buds adapt with time, and we do get used to different foods. We’ve seen this on the study time and again, where patients initially find it hard to do it in the first few weeks, but once they do it long enough, they feel like it’s much easier to manage because they’re now used to these tastes and foods. That’s one quick tip.

Another one would be dietary fiber. If you think about the US population, the average American gets about 10 to 15g of fiber in their diet. There’s a survey been done from the NHANES and they asked a set of the US population and said, “How many of you think you get enough fiber in your diet?” 67% people said, “Yes, we get enough fiber.” In reality, only 5% do. There’s this big disconnect where people think they’re getting enough fiber, but they’re not.

Dietary fiber is really food for the microbiome. When you think about it that way, I think it would be very important to make sure you’re getting at least 25 to 30g of fiber a day. I’m not talking about fiber supplements, but dietary fiber, so think about foods you’re eating. Fiber only comes from plant foods, so try to up that intake of the fiber in your diet. I think those two things are very powerful.

Another one could be looking at fermented foods and increasing the consumption of those. There have been microbiome studies showing how fermented foods reduce inflammation and also improve diversity. That could be another aspect of change to think about.

What are some common, healthy fermented foods?

Dr. Shah: Fermented foods are things like kimchi, kombucha, yogurt. Those would be some of the common ones. Sauerkraut, things like that.

What are some common high-fiber plants?

Dr. Shah: For fiber, I think beans. Beans or legumes are one of the most underrated best foods ever because they are longevity foods. Many of the longest-living populations actually eat a lot of beans, and we don’t really see most people eating them. One cup of beans has 15g of protein and 15g of fiber.

A very simple fix for a patient would be, if they were getting the average American diet and having 10 to 15g of fiber in their diet, eat one cup of beans and you reach 30g of fiber already. It’s a very quick fix in that sense. In a cancer patient, if they need a little more protein or energy, beans are a good source of that too. Other foods that are good or healthy are cruciferous vegetables. Broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and cauliflower.