CAR T Cell Therapy

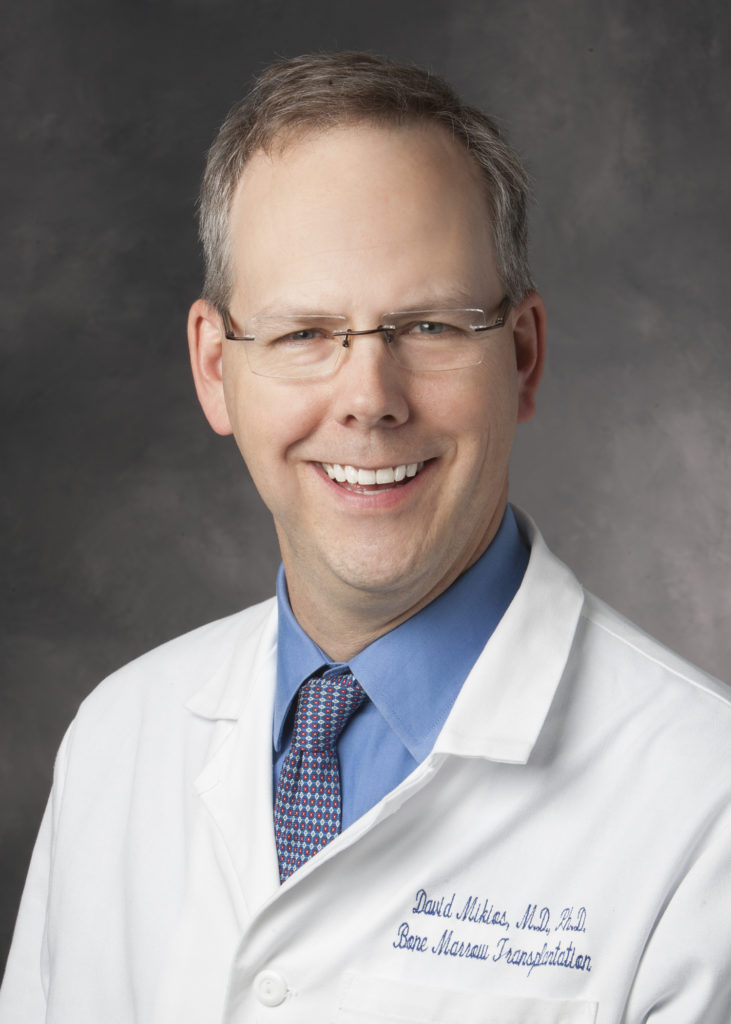

David Miklos, MD, Ph.D

In this interview, Dr. David Miklos talks in-depth about CAR T cell therapy, mantle cell lymphoma treatments, allogeneic transplants, and gives his thoughts on future therapies.

David Miklos, MD, Ph.D is an experienced and passionate specialist in blood and marrow transplants, as well as immunotherapy research. As Chief of BMT & Cell Therapy, and Clinical Director of the Cancer Cell Therapy program at Stanford University Medical Center, Dr. Miklos spends his time not only seeing patients but also focusing on the latest science in cancer therapies.

- Name: Dr. David Miklos

- Specialty: Blood and marrow transplant

- Roles:

- Chief of BMT & Cell Therapy

- Clinical Director Cancer Cell Therapy, Stanford University (2016 – Present)

- Experience: 25+ years

- Provider: Stanford Medical Center

We’d like to cure more and more diseases. What is cured?

People ask me all the time, ‘Am I cured?’ The difference between remission, where we have no measure of your cancer anymore on a scan or bone marrow or blood test, and a cure, is time.

Dr. David Miklos

- CAR T Therapy

- Video: Dr. Miklos on CAR T Therapy

- What is CAR T therapy in layman's terms?

- What is CAR (chimeric antigen receptor)

- CAR T expanding quickly

- Stanford’s latest work: CAR 22

- Disease progression and changing targets

- Promising results

- Role of CAR T therapy

- Newest study: ZUMA-2 clinical trial

- New clinical trial

- What are the drawbacks of this newest therapy

- Balance between therapy efficacy and adverse effects

- Why patients should consider clinical trials

- State of current and future therapies

- Dr. David Miklos' Full Interview on Video

CAR T Therapy

Video: Dr. Miklos on CAR T Therapy

What is CAR T therapy in layman’s terms?

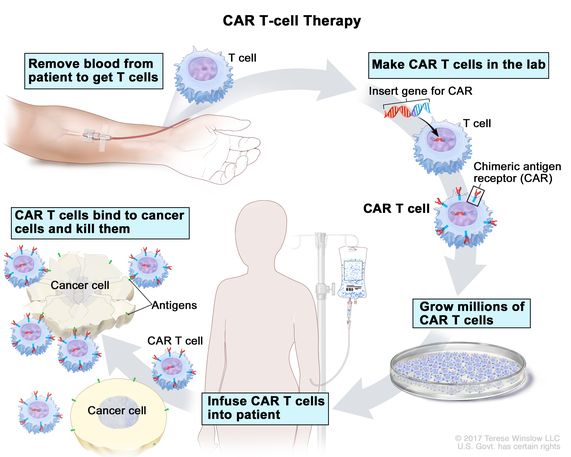

It’s the use of the patient’s own lymphocytes. These are the immune cells that provide us our education, these are the things we’re talking about with COVID as to whether or not you have antibodies or immune responses. The question is how are we going to vaccinate ourselves?

We understand the power of the immune system. We know that there were no antibiotics until 150 years ago. We know we’ve had 10,000 generations of pond scum up to human beings at this point in evolution.

All that depended on our immune system but we haven’t been able to harvest the immune system to cure these aggressive cancers – until now.

The opportunities to try and vaccinate a cancer have been disappointing and so the general approach of the cancer cell therapy or CAR T program is to hijack the patients’ own immune cells to remove the lymphocytes from the body using a very simple procedure, apheresis, just like you see in the Red Cross donation centers where patients are giving platelets.

No pain, three hours, piece of cake.

What is CAR (chimeric antigen receptor)

Take those cells into the laboratory and introduce a new gene. We call that a chimeric antigen receptor, the CAR. And that modification of the lymphocytes becomes permanent in those cells, but it doesn’t go into the rest of the body.

You’re not going to become a GMO like the corn in Iowa.

We are modifying the lymphocytes. Those super-charged cells after one week of manufacturing and one week of safety evaluation in a lab, are brought back to the patient, frozen in liquid nitrogen, which is not only for ice cream, and those cells are then introduced back to the patient’s body in the same catheter that earlier the lymphocytes came out.

They expand from two million cells to 20 billion cells in seven days. It’s variable depending on what cell therapy we’re talking about.

The thing about that is cells dividing every seven hours and frequently, after a week of expansion, the CAR modified T-cells represent 50-percent of the white blood cells in the patient’s body.

These are cells that can do four things that have never been done in cancer.

These are cells that are proliferating in the patient’s body, localizing to the tumor, able to kill with cytotoxic killing, like we use for viruses like influenza, and then they persist, providing you surveillance until the cancer’s all gone.

In fact, some of these CARs are designed to last for years. Others are designed to simply go away over the next four to twelve weeks.

That’s the value of the excitement of the CAR T program. It’s a paradigm shift of using the patients’ own lymphocytes to kill cancer with all the power of the immune system in a way that was never done before.

CAR T expanding quickly

This was pioneered by Dr. Carl June and Steven Rosenberg at University of Pennsylvania and the National Cancer Institute, but really became available broadly to the lymphoma patients only in 2016.

I remember back to February 2016 when we treated our first patient here at Stanford. Now, we are treating 120 patients this year at Stanford with the CAR T-cells.

We anticipate increasing about 50-percent per year.

Stanford’s latest work: CAR 22

The initial work was targeting CD19, a series of cell-surface proteins and they have numbers. The B-lymphocytes important ii lymphoma and leukemia were the first successful use of CAR T. We have three targets: 19, 20, and 22.

Most of your patients have had rituximab, the monoclonal antibody, and I’m sure they recognize that bottle that infuses over three to four hours of clear liquid. That’s targeting CD20, but that’s an antibody.

You put the antibody in and it doesn’t grow, localize, or do any of the things we just said. It’s effective, don’t stop taking your rituximab. It’s an important part of our therapy.

But soon we’re able to go after additional targets. If a patient was treated with an axi-cell (Yescarta) or tisa-cel (Kymriah), or soon, liso-cel from the Juno work we expected to be approved, those are three soon-to-be commercially approved (axi-cel in October 2017, Juno’s liso-cel we expect later this month), three CAR T-cells commercially available that the doctors are choosing which one’s the best for that patient.

They’re all targeting the same protein and using the same binder on the surface of the cell. They’re all very similar, actually.

Creativity means let’s go after a new target.

Disease progression and changing targets

One of the biggest problems our research has shown that the patients receiving the CAR therapies who have disease progression, frequently two to three months afterwards, that progression happens in half the patients and half the patients have long persisted remissions that are out at three and four years now.

But the patients who have the progression – why? Why did the CAR fail? What we’re finding to be the most common reason is the lymphoma cells, the cancer cells stop making the target.

So what was there before as the target that the CAR bound onto and then interacted with and then was able to activate and kill, when the target disappears, the CAR has nothing to bind.

So antigen loss of CD19 can only be overcome by going to a new target. Here at Stanford we have been fortunate with our programmatic leader, Crystal Mackall, who came from the National Cancer Institute, and has brought some of the basic science constructs that are necessary to move into these new targets.

We’ve had great success recently with the target of CD22. Similar to the rest of the CARs it’s a chimeric antigen receptor, uses the patients’ own lymphocytes, harvested but manufactured here at Stanford in our own GMP laboratory.

That’s the clean room laboratory, like you see with Intel, the guy’s in a white gown dancing around.

That clean room mentality so that we can ensure that the virus goes into the lymphocytes, that it’s safely matured and that we collect enough cells after a week of production, and we bring them back to the patient.

Promising results

The excitement here is that in patients who had progressive disease after axi-cel, or tisa-cel, that we have witnessed seven out of nine of these early patients on clinical trial achieving responses.

Five out of nine in complete remission, and those durable remissions in our lead two or three patients are now out to a year. They have very low toxicity, low cytokine release problems that your patients probably know about.

What happens after CAR is you feel like you have the flu with fevers and aches, sometimes low blood pressure and cough or low oxygenation. We can manage that with steroids and a special drug called tocilizumab. Those toxicities are very low, so that’s very exciting to us.

Now please don’t run out to all your local hospitals asking for CAR22, this is an investigation being done here at Stanford where we are able to help patients who’ve had progression after axi-cel and patients do come from all over for this.

There are other clinical trials also targeting and helping patients who have had progression after they’re commercially available.

One of the most exciting areas there is instead of using the patients’ own lymphocytes, why not take cells that haven’t gone through two or three rounds of chemotherapy, haven’t existed for 60 or 70 or 80 years in somebody’s body, why not take a 21-year-old super donor lymphocytes, from someone healthy and fit, that has been made stealth-like by removing some of the histocompatibility markers, immune cells that would be rejected.

Those stealth cells are also expressing CAR T-cells. Some of the companies doing this work are Precision Bioscience and Allogene. They have different targets, CD19 and CD20.

And again, we’re using those opportunities to help our patients here at Stanford. I’m sure some of your patients can find those locally in centers near them.

The allogeneic approach is very exciting because you don’t have to wait to make the cells. You already have the cells in the liquid nitrogen freezer. It’s kind of one size fits all. You know how good those cells are because you’ve seen them function in other patients, previously.

So there’s potentially a lot of advantages to these allogeneic cells, but of course we have to make sure they will grow and expand, and not get immunologically rejected by the patients.

These are still early clinical trials, but very exciting opportunities for patients who have not benefited completely and have not gotten a durable response from the CAR T’s that are commercially available.

That’s how I think about the development of CAR T.

These are clinical trials. Patients can come to academic centers and participate in clinical trials. Other centers are doing very exciting work. Please don’t think we have all the answers at Stanford. There’s very exciting work, as you would imagine, the top 30 large cancer centers in this country. We’re very fortunate to have the support of the patients and their families.

In 2016, before we started our CAR therapies and what turns out to be axi-cel or the commercial trade name of Yescarta, the benchmark study of what happened to patients who didn’t go on to CAR T with relapsed/refractory lymphoma who’ve had three lines of therapy previously, was dismal.

That was an experience we’ll never want to repeat. The median time to death was five to six months. The one-year survival (rate) was 15-percent.

Now, with the approaches of Yescarta, tisa-cel, and I anticipate liso-cel, the one-year survival rates are 85-percent. We think with having additional therapies we can use in patients who are progressing, we’re going for 100-percent.

Who wants 85-percent? Let’s go for 100-percent.

Role of CAR T therapy

The axi-cel therapy was the first FDA-approved treatment in large cell lymphoma. That company is called Kite. They were purchased by Gilead. They brought forward a very similar construct.

The actual molecule that is placed into the patient’s lymphocytes is exactly the same as what’s been used for the last three years in large cell lymphoma. So it binds the same CD19 again, same story, here comes the CAR. We’re going to bind and we’re going to then kill the cancer.

It’s prepared in a very special way because mantle cell frequently has lymphoma in the blood, so we have to separate the lymphocytes away.

That’s the unique difference between Tecartus and Yescarta. Otherwise, they’re nearly identical therapies.

And the prep to do this is the apheresis, the places where you’ll receive the therapy, the lymphodepletion chemotherapy, and the three days before we put the special cells in. It’s all the same. The follow-up stay in the hospital, seven to ten days, staying locally for 28 days, it’s all the same.

The expected toxicities of cytokine release syndrome, that’s the fever, achy, flu-like symptoms, or the confusion and neurological problems that can follow patients who have had the cytokine release syndrome, again, very similar incidents.

Newest study: ZUMA-2 clinical trial

Here’s the excitement: the excitement is in that study you addressed called ZUMA-2, which began in 2017, there were 60 patients treated and this overall response rate was 93-percent.

The overall complete response rate, couldn’t find the cancer, was 67-percent.

Two-thirds of the patients, 28 days after given this Tecartus infused in their body, had no measurable cancer, a complete response. That response has remained durable. The publication that is responsible for the FDA’s approval showed 27 months of follow-up in patients.

That’s just over two years, so let’s not get carried away. We have two years of follow-up and in that population, the response rate was 43-percent remaining in complete response and 67-percent overall response.

So it’s very durable. Probably even more durable than what we saw in the original treatment with axi-cel in large cell lymphoma. There are similar side effects and it still needs to be done inside the hospital at centers that have experience managing patients with CAR T therapy. The higher response rates and they appear to be very durable treatments.

These are for patients who had had three lines of therapy previously, so they probably had CHOP, or bendamustine and rituximab, they probably had ibrutinib as one of the therapies. That trial required they had a drug that targeted the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK).

The FDA, when they made the approval of this therapy in July, recognizing what a game changer the therapy offered patients, did not require patients go through three lines of therapy.

The FDA has authorized the treatment in second line and I think that’s because they really want to help patients achieve long-term disease-free survival and benefit.

Now, physicians will have to decide who should receive BTK inhibitors and who should go right on to CAR T-cells, and that’s discussion with the patients and the families. That really is still being worked out.

»MORE: Read patient experiences with immunotherapy

New clinical trial

We’re going to be doing a new trial where we’ll be looking at patients who’ve had ibrutinib upfront or who have not had ibrutinib yet, and using the same therapy to see what the true incidents of benefit is in that second line.

But in the meantime, there are centers that can provide commercially-available therapy with Tecartus today. If somebody’s gone through all the available therapies, that’s a lifesaver.

As we decide whether we should use CAR T-cells in second line, that’s an individual decision at this point for the patients and their doctors.

What are the drawbacks of this newest therapy

I think we have to make sure the therapy does not cause more toxicity than the patient’s need warrants.

What I think is going to happen is we’re going to see less CHOP chemotherapy up front. We’ll probably be shifting more to the kinder, gentler bendamustine-rituximab, and maybe even in combination with ibrutinib in the first-line therapy.

The intent of that is to really clear the disease, make sure we get the highest response rate possible with the lowest toxicities, and frequency of going into the hospital with side effects like neutropenic fever. We want to avoid that.

I think that’s where the field is moving. Then the key decision, and I’m the Chief of Transplant (at Stanford) so I don’t want to malign my own therapy.

But whether or not auto transplant continues to be important in the management of mantle cell versus going right on to a targeted cellular therapy, is really the next question.

So that decision needs to be made. What we’re trying to judge is what’s the risk of the patient having cytokine release syndrome or really high-impact, really debilitating neurological toxicity.

Balance between therapy efficacy and adverse effects

A grade three neurological toxicity is when the patient is really unresponsive in the hospital, just lying there, eyes open, frequently having expressive aphasia, can’t talk, can’t find the words, can’t attend. That period of time lasts usually two to three days and patients are being treated with steroids.

Young people, like us, we may have the ability to have the reserve to get through something like that and easily bounce back.

But if you were 80 years old, having a similar treatment options, and trying to decide, I imagine the ibrutinib therapy would be the more appropriate, at least until it’s not working.

While patients are receiving those better-tolerated, maybe not curative therapies with very good efficiency or efficacy, we’re working on new therapies. We’re working on kinder, more gentler therapies, with less toxicities.

The companies we’re mentioning here are fully committed to trying to improve these treatments. Whereas maybe the drugs you took for your blood pressure and your diabetes are still the same drugs after 20 years, these drugs will not be the same drugs after five years.

We will be moving the development curve cycle into a very rapid change, because knowledge is what is going to drive the next therapy.

As we learn how to help the patients, how to improve the treatments, what happens as the universities will quickly disseminate through pharmaceutical companies to the patients’ care.

Why patients should consider clinical trials

It’s a very exciting time. It’s these small clinical trials that are able to demonstrate clinical benefit, but at the same time, we’re collecting blood samples and lymph node samples that allow us to test questions like:

- How did it work?

- How did the CAR expand?

- Did it go into the lymph node?

- Did the lymph node stop making the target?

- How do we make this treatment better?

We call that the virtuous cycle of correlative clinical trials and that’s what these large academic centers are all about. We’re trying to turn that cycle as fast as we can.

That’s a partnership with our patients, so when your patients go to a cancer center and the doctor says, “We have a clinical research trial and we have the standard of care,” it’s important to listen closely.

There are very good treatments in the upfront use of tisa-cel, axi-cel, and soon, liso-cel, so we want to be able to offer those therapies to people with 60-percent complete response rates.

But if you are having a recurrence of disease after that therapy, or that therapy is not appropriate, then it’s important to consider participating on a clinical trial in order to get access to the more promising treatments.

That’s the hardest conversation. Bring all your friends, bring your family to the doctor’s visit. You’re going to need lots of ears to be listening to why you should do this or could consider these other options.

Your doctor should be making recommendations, but you, too, have to participate as you consider the benefits and the risks.

State of current and future therapies

Multiple Myeloma

That’s my philosophical question. Let’s start with multiple myeloma, a disease we haven’t talked about but many of your patients have this.

There’ve been many advances in drug therapy since Ken Anderson in 1998, my Dana Farber mentor, said, “You know, you could take lenalidomide and dexamethasone and have a better outcome than chemo.”

That quickly changed into revlimid and that quickly changed into a whole bunch of drugs that now have really revolutionized how we think about the treatment of multiple myeloma. That’s actually changed the survival rate of patients with multiple myeloma.

You can follow in the first five decades, there was no improvement in the survival or myeloma patients. Now we can demonstrate improved overall survival every two to three years since the development of these small molecule drugs. That’s important.

There are patients with myeloma who are being cured. CAR T is coming into myeloma so that’s exciting.

We have shown that small molecule inhibitors, these phosphorylation-inhibiting drugs, these tyrosine kinase inhibitors, imatinib, ibrutinib, ruxolitinib, are having a profound effect and really better quality of treatment for the patients.

A small molecule pill instead of chemo with your hair falling out, that’s got to be good. Having a long-term disease-free survival, hopefully cure, is really advancing that field.

I think small molecule inhibitors are having a real impact on the indolent cancers.

CAR T Therapies

But the patients who have really aggressive cancers, cancers that are dividing and multiplying and doubling every two to three weeks, those small molecule inhibitors usually aren’t enough, unfortunately.

This is where harnessing the T cells and bringing CAR T cell or T cell engagers (comes in). We didn’t talk too much about that, you’re talking to a CAR T therapist so let’s say I’m a little bit of a fan, and I’ve seen these responses in patients go dancing out of the office on day 28, so I’m a big fan.

And no GVHD, no graft-versus-host disease. Pretty well-tolerated. We would like to prove the tolerability of the therapies and that’s what we’re working on.

Who’s benefitting from these therapies

I think that patients who have the blood cancers have benefited from all the advances and let’s bring it on. Let’s keep going. Let’s make this a story of only success.

What do I think is going to be needed are to apply these immune therapies into the tough cancers – the lung cancer, the breast cancer, the prostate cancer, the pancreatic cancer patients, where we haven’t small molecule inhibitors that are truly effective in this sense. Some are coming.

The checkpoint drugs we’ve seen benefit patients. Some people have really benefited from checkpoint inhibition of their own T cells, taking the brakes off their own T cells and letting their immune system fight the cancer.

That has shown benefit in many cancers. That will continue, but I think we want to figure out how to bring the response into lung cancer, into brain cancer, where we have nothing. And into all these diseases that people suffered through with the same old chemotherapies and toxicities, in ways that are not always providing long-term benefit and very few cures.

We’d like to cure more and more diseases.

What does “cured” mean

People ask me all the time, “Am I cured?” The difference between remission, where we have no measure of your cancer anymore on a scan or bone marrow or blood test, and a cure, is time.

So these exciting therapies that we’re talking about today, when I say I have a patient one year out, I hope she’s cured. But we need to wait till she comes back to my reunion in five and ten years. Until she brings her kids back.

The difference is time. And I know that your patients don’t want to wait for new developments. That’s why we have clinical trials.

That’s why testing new therapies is a partnership with patients who need treatment today and are able to be educated by their doctors and their care teams, so they understand the risks.

They’re getting the best therapies available offered to them quickly, so that they can benefit now.

I have the best job in the world, just in case you asked. It’s a bit of a vocation.

Dr. David Miklos’ Full Interview on Video

Other Oncologists

Dr. Christopher Weight, M.D.

Role: Center Director Urologic Oncology

Focus: Urological oncology, including kidney, prostate, bladder cancers

Provider: Cleveland Clinic

...

Doug Blayney, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in breast cancer | HER2, Estrogen+, Triple Negative, Lumpectomy vs. Mastectomy

Experience: 30+ years

Institution: Stanford Medical

...

Dr. Kenneth Biehl, M.D.

Role: Radiation oncologist

Focus: Specializing in radiation therapy treatment for all cancers | Brachytherapy, External Beam Radiation Treatment, IMRT

Provider: Salinas Valley Memorial Health

...

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

...