Michele’s Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Story

- Name: Michele N.

- Diagnosis:

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

- 1st Symptoms:

- Slow healing

- Scalp infection

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Treatment:

- Clinical trial of ibrutinib, fludarabine, chlorambucil and rituximab

- Acalabrutinib

- Relapse: May 2021

- 1st Symptoms and CLL Diagnosis

- CLL Treatment and Clinical Trial

- Video

- What was the catalyst for you to go into treatment?

- Clinical trial

- Side effects going away

- Increasing fatigue

- Ibrutinib and FCR regimen

- Dealing with the side effects

- Neuropathy

- Dermal reactions

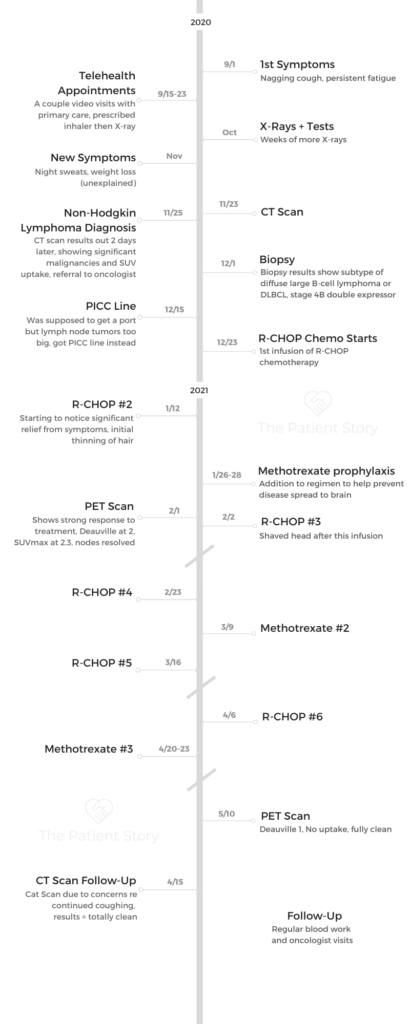

- Treatment from September 2015 to May 2019

- Continuing treatment and quality of life

- What was it like going back on treatment?

- Choosing between treatment options

- What is most important to you when deciding the path to take?

- Being on acalabrutinib

- Finding Purpose in Cancer

- Video

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

1st Symptoms and CLL Diagnosis

Experience outside of CLL

Life before CLL

Before CLL, I was very career oriented and family oriented. I was that kind of woman who had to do everything super well. I was A++ at everything. I’d started out in broadcast journalism on TV news before I segued into the corporate world — or as we say in the business, the dark side of journalism.

I was the global chief of communications for a $9 billion publicly traded company, and it was a really cool job, very stressful, with long, long hours. When I say long hours, I mean I slept a few hours a night, seven days a week, because of time zones and the media. It was a great job until I was diagnosed.

What about your life now? What are your hobbies?

I’m happily married. I have a terrific husband, who is so supportive of everything, of things that I do with friends, things that I do for work, my patient advocacy. Also, he is the best care partner there is.

In addition to that, I’ve always been a fitness nut and into exercising. I used to go to the gym before COVID. Now I do what I can at home. I do yoga now because I’ve learned that’s really good for you and to calm the mind.

I have Gabby, who is our chocolate lab. She’s my buddy, and we seem to do everything together. She has been also a great support to me during all of everything that I go through with cancer and outside of cancer.

Diagnosis

First symptoms

I thought I was a healthy person. I always had been very healthy and active. My God, my schedule alone! I figured you had to be a healthy person to be able to keep the hours I did and to always be traveling everywhere for work.

I was on planes 1 to 2 times a week, and they could be going anywhere in the country or in the world. Healthy eating was really big for me as well. I started having these weird things happen, each one in itself didn’t seem like a big deal.

I talk about these so that other patients, when they hear this, will know that these are things they should watch for if they have CLL. It’s things that if you look back, you’re like, “Oh yeah, that happened to me.” It took me a while to even realize that these pieces were there.

I figured you had to be a healthy person to be able to keep the hours I did and to always be traveling everywhere for work.

Ongoing infection

In November of 2010, I had a flu or something that led to chest congestion and a sinus infection from hell. I just couldn’t get better. I went to an ENT, and they didn’t do any blood work or anything. They just treated the symptoms because they had no clue that anything else could be wrong.

That lasted a really long time. I was traveling. Each of these times I had just traveled out of the country. Long flights, long hours. Not eating as healthy as I’m used to, not having time to exercise.

Scalp infection and bumps

A few months later, something else happened. I had this weird scalp infection, but it looked like I had burned myself with my flat iron. I’m just like, “Stupid, clumsy me, or maybe this happened at the hair salon when I had my hair cut or colored.”

I had these huge bumps at the base of my skull. I had no clue at that time that lymph nodes were everywhere and that those were lymph nodes. Then I went to an emergency clinic because it was just so bad, and my husband thought that maybe someone should see it since it really looked pretty gross.

I went there, and they gave me a shot of some kind of antibiotic. Then I went to my dermatologist, and they again treated what that was.

Then a few other times, I just kept getting sick. I would catch a cold, and it wouldn’t go away. I would get a flu or sinus infection. It just lasted forever. These are all really common things now that I know about CLL. These are really common things and signs for someone to look at and put all together that you have something.

Elevated white blood counts

Your white blood count, the highest end of the range should be pretty much in the mid to high 8000s. Mine was maybe 11 consistently, and then 14. That’s what flagged my primary care physician (PCP).

Plus, when you see your PCP, it’s not that often. He wanted me to come back in maybe six months. Of course, I delayed that because of work and being too busy. I’d kind of forgotten. It was like, “I don’t even know what that means. What’s the big deal?”

Then when I went back, it was still elevated. That’s when he suggested I see a hematologist, which in my mind was just a hematologist. I didn’t even connect hematologist and oncologist.

I didn’t return his calls for a long time until my assistant sat on my desk and said, “I’m not leaving until you call your doctor. This is the fourth message. You’ve got to call.”

Still, it didn’t dawn on me because I didn’t think about it. I didn’t take the time to think about it. I was so busy with everything. Why is he calling me? I didn’t even think there could be anything wrong.

This is something you shouldn’t do. I have since learned, and I learned the hard way. He was very calm about it. I have to give him credit. “I don’t want you to be alarmed. Your white blood count’s a little elevated. Again, I really would love you to go get this tested again and see a hematologist.'”

In my mind, I was like, “Yeah, someday I’ll go do that.”

Finding the hematologist

My PCP was a bit north of where I worked, and he knew how busy I was. He said, “I don’t know anybody in Miami, but see if you know anybody who can make a reference or recommendation for you.”

Someone I knew who was a nurse recommended this particular doctor. I walked into the University of Miami Sylvester Cancer Center, and it still didn’t dawn on me what I was being tested for.

I went through tests and questions, not knowing, having no clue. Nobody told me why I was being tested. Maybe he assumed my PCP told me, and my PCP maybe figured he told me.

I had no clue, and I’m like, “Why is he asking me this? Why are they taking so many tubes of blood? And why is he telling me, ‘I’m sure you’re fine’?”

I honestly had no clue. I was so busy. I registered hat it was a cancer institute at University of Miami Medical Center, but I never, ever put two and two together that that could be me.

Testing after blood tests

Then he did a verbal really long list of questions for family history. My parents were very healthy all their lives and living long lives. It’s not like they were young and passing away.

Again, I was just like, “This is taking so long. I have to get back to work.” This is how crazed about work I was. I’m like, “I have a deadline. I have a reporter waiting back at the office. I’ve got to get back to the office.”

I look back, and I realized that that’s probably not the best way to be in life. You really have to think about your health at times. The other thing is, though, it protected me in a way from knowing how grave this could be.

When I walked in there, I didn’t think that could be me.

I see people hooked up to IVs as I’m walking through. I see cancer patients and in wheelchairs, sadly without hair. When I walked in there, I didn’t think that could be me. It didn’t even register. If I had had time, perhaps I would have been a basket case, because it’s shocking to think that that’s you. That’s your future.

Time it took to get results

It took a while to get any kind of call. I put it out of my mind. I’m like, “Okay, whatever. I guess I’ll hear something if anything’s bad.” It took a couple of weeks, and then I heard from someone in the doctor’s office that everything was fine. That’s great. I’m thinking, “Of course it’s great. I’m healthy.”

I got a call a week later, and she said, “The doctor wants to go over your test results.”

I said, “I thought you said everything was fine.”

“Well, he just wants to meet with you.”

I’m like, “This is really nice,” but really I’m thinking, “My schedule is so packed.”

She said, “No, really, he really just wants to go over these things.” Again, you would think that it would dawn on me and I’d be petrified, but I was not.

The CLL diagnosis

I was just, as the English would say, gobsmacked. I sat down, and I had no clue what he’s going to say. He came in and said, “Well, you have the C-word.”

This is how out of tune I was. I’m like, “What is he talking about?” It wasn’t top of the mind awareness what the C-word was, because again, I didn’t know I was being tested for the C-word. Then I’m like, “Oh no, that C-word.”

He blurted out, “You have CLL, another C-word, chronic lymphocytic leukemia.” He said it so fast, and I was in shock. I was dumbfounded. What did he just say to me?

Of course, that changed my life right there. Then I heard “leukemia.” That’s all I heard. I’m like, “This doesn’t sound good.”

He said, “I’ll see you in four months,” and he went to leave.

I said, “Wait.” Of course, having my journalism training, I always have a million questions. “Wait, wait? Shouldn’t we get rid of this now?” The things that we would normally think that are logical for cancer.

He’s like, “No, you don’t have to be treated. You may never have to be treated.”

»MORE: Reacting to a Cancer Diagnosis

Processing the C-word

This is just not making sense. I’m in shock, and I’m like, “What do you mean? Well, what am I supposed to do?”

He said, “Just go on. Make sure you wear a mask when you’re in public.” The cruise industry is big in South Florida. He said, “Wear a surgical mask when you’re on a ship.”

Meanwhile, I’m in the cruise industry, and I’m leading press conferences. I’m like, “This is not a good visual.” This is before COVID times. We’re talking back in 2012, and that would not be a very good visual. That’s all he had for me.

I didn’t understand. I needed more information. He could not wait to leave the room. I asked, “Do you have any literature on this? How about on the hospital’s website? Is there somewhere you can suggest for me to look? For me to research this?”

He had nothing. And that was it. Then he put his hand on my shirt. He said, “Don’t worry, you’ll be okay.” He was an older doctor. He did get it right on my diagnosis, but when I walked out, I just knew that I probably wouldn’t go back there.

Switching doctors

I knew something wasn’t right. For me, that wasn’t my cup of tea to be treated that way and also to never be told what it was I was being tested for. I was really in shock, as well.

He couldn’t even say the word. The other thing he said was, “You have the C-word, but it’s the best one you can have.” None of this is making sense in my brain.

When that clicked, I’m like, “How can that be best of anything? It’s cancer.” I’ve heard this from other patients. They say they’re told that it’s the best one you can have, and that just offends everyone.

Advice for doctors from the patient perspective

Maybe you shouldn’t say it’s the best cancer anymore. Don’t say it’s the “C-word.” This could be a style between doctors and not to get patients overly worried, but if you’re testing someone, maybe you should let them know what you’re testing for and list a few things that it could be.

Maybe he didn’t know which kind of blood cancer. Maybe this was my PCP who should have told me, but you would think they had an idea if I was sent to a hematologist oncologist.

Let me know, or put it in a list of various things it could be. You don’t want to overly worry me in case it’s nothing. That, again, could be a generational thing between the doctor.

Emotions after the doctor left the room

I was just like the jilted girlfriend holding on at the last moment, like, “Please don’t leave me.” Of course, now I can look back and joke about it because we have self deprecation, having cancer and having been through these horrible things.

That was a very low day in my life, and I proceeded to make some pretty stupid decisions after. The other thing is I drove myself, and it wasn’t around the corner from where I work. That shouldn’t happen.

Processing the diagnosis

I went back to work and acted like nothing happened, and I went home and crawled up in a ball. Before I did that, I burned the hospital bracelet in my bathroom like it didn’t happen. I had water running so I wouldn’t set off. the smoke detectors. This is me. I’m always thinking of everything.

I burned the hospital bracelet. In my bathroom. Like it didn’t happen.

I burned it because I was so upset. Maybe it didn’t happen if I burned it? I don’t know. Then I convinced myself maybe this was wrong. Maybe they had somebody else’s blood test results.

I tell my patients now, “Do not do this.” I curled up in the fetal position after I went on Google and did a search, and it said I’d be dead.

Some had said three to five years; some said five to eight years. That was very old information that I found, or speculative. I hadn’t yet learned that first night what the credible sites would be and how they’re credible. At that time, 2012, there wasn’t as much available on the internet about our various diseases.

Telling family

I called my sister, I told her — wait till you hear this one — I was going to leave my husband. We had not even been married two years, and it wasn’t fair for him to have another wife with cancer.

His first wife had cancer, and she had passed. I just couldn’t do that to him. She talked sense into me. She was like, “You need to hang up with me and call him right now and tell him what’s wrong.” I was like, “I just can’t do this to him and the kids.”

His children became my children, and I just didn’t want them all to go through this again. It was really hard on so many levels. But I 911’ed him when I hung up with her after she talked sense into me. I don’t even know how this was for her.

It was too late for him to take a plane that night, so he was on the first plane in the morning. He was in Boston. I was in Miami. That’s when it really hit, when you’re together and share it. I don’t know how he even got to the airport himself and how he got on that plane.

»MORE: Breaking the news

Figuring out next steps

Then we figured out what I was going to do, and it was basically I had to leave. I left Miami and left everything: parted with work, my home down there, my life down there, my friends. I had some really terrific friends because I had been down there about seven years for my career. But what’s more important? Health and family.

My mom was up in Massachusetts, as well. I didn’t even tell my mother for a long time because I didn’t want her to worry, and I knew I wasn’t going to be in treatment.

“If I’m not in treatment, just what is the point?” I thought. I have no clue what to even tell people. I have it. So what?

Getting a second opinion

I had a second opinion within six weeks at Dana-Farber with the head of the CLL department. I didn’t even know that there was such a thing as a specialty in CLL. and that was something else I wish that the doctor had mentioned in Miami.

I was just so lucky and blessed that where we lived in Boston, we’d be seven miles away. There was a CLL specialist, an entire department, so I started seeing her.

I was hoping that those tests were wrong. I really did hold on to that hope in the back of my mind. I knew there was something. If I thought about all those things that I had mentioned earlier, there was something.

I came back to Boston full time to be with family and try to figure out what I was going to do then. I realized watch and wait is a real thing and that yes, I can still work.

Worrying about reactions

It affects everyone in your family circle. I wasn’t thinking straight. I did worry about them, and I just didn’t think that it was — “fair” is probably the wrong word, because none of it is fair right to any of us.

Life during watch and wait

Watch and wait’s also called “active surveillance,” and it exists in some other things as well. There’s another blood cancer where it’s called a few different things as well. What patients call it is “wait and worry” or “watch and worry.”

It’s somewhat inhumane when you think about it. You’re basically waiting and watching your disease worsen until it would be so bad that you need treatment versus doing it the way you logically would with a different type of cancer that we have all heard about. You know that you treat early, get rid of it and you have better chances.

There are some patients who never need treatment, so that watch and wait could be forever for them.

Michele

Not everyone gets worse, and CLL is such an odd disease that not everyone needs to be treated. There are some patients who never need treatment, so that watch and wait could be forever for them.

Until they test certain things like your genetic factors, prognostic indicators, they don’t know how you will be and how your disease will progress or not. That’s one factor that they look at.

From the time of diagnosis, I do suspect I had CLL longer before from different factors, but from diagnosis they say it’s generally an average of two and a half years to treatment, which is just about what it was for me.

Learning about CLL

I’ve heard this from so many other patients, and I just want to tell you, use that time of watch and wait to educate yourself on CLL because it helps. For one, you do need treatment if you ever need treatment.

I was diagnosed ten years ago and I’m here, and there’s just so much hope for patients. It also helps prepare you for what’s going to happen. For me, the more I know, the better it is for me because then I know more of the facts as opposed to me wondering.

That’s when my mind kind of goes like to places it shouldn’t go. Once I could understand facts, it really helped to calm me down. That’s really why I started reporting on CLL for other patients to help them to demystify what it’s all about.

Living with chronic disease

Waiting for signs

There is a percentage of patients that do need treatment immediately, and they don’t like that either, as opposed to being able to watch and wait. For the watch and wait, every time you go you wonder, “Will this be the appointment that they tell me?”

You start to learn, and you also open communications with your doctor. “When will you know it’s time? Can you give me an idea how long in your experience for someone like me it’ll be?”

Again, we are so different, all of us. It’s tough because there are so many factors. For my white blood count, it was a certain amount. It was that, and it was lymph node burden. It was spleen size and all sorts of things.

I have a friend whose white blood count is at 240,000, but it’s not time for treatment for her due to other factors in her blood work and in the exams that you get. For me, it was totally different.

That’s why it’s so important to make sure you do keep your appointments. For me, it was every three months and then every two months as I got closer to treatment, and then it was just time.

For a lot of the patients I’ve spoken to, it really does vary. One of the things that helps determine this is something called a FISH test. That will show your genetic markers, your prognostic indicators, and they also do something called a flow cytometry.

I know there’s a good number of patients who have never had these done, and they’re not in treatment yet. I do suggest that you ask for those because it does help for you to know what those are.

»MORE: Genetic Testing for Cancer

Time for treatment

For me, it was a combination. My platelets started going low below range. My white blood count started doubling, although it never even got as high as this other person I’m speaking of. I know other patients that have gotten even higher white blood counts and still aren’t in treatment.

It was my lymph nodes, and they can tell that by physical examination. I mean, you could see my lymph nodes. They were all swollen. You could see them here. It wasn’t only my lymph nodes; it was a combination of platelets and other counts they look at. They want to look at your hemoglobin to see how that’s doing.

All of that put together. It takes a specialist really to put all those all these puzzle pieces together. That then is the point. For someone else, it might be that their white blood count gets so high and their platelets tank maybe lower than mine did, and maybe their spleen is really swollen, so it’s time for them.

There are all different indicators there that help. I know someone else who their white blood count went down, but they had CLL and some other factors happen. It’s just that varied for patients, depending on what it is about their disease for time for treatment. I also encourage second opinions.

CLL Treatment and Clinical Trial

Video

What was the catalyst for you to go into treatment?

The catalyst for me to start CLL treatment after having been on watch and wait for a little over two and a half years was that my white blood count had doubled a few times in values between appointments. Also, my lymph nodes had grown to a large size that was palpable for my CLL specialist to find. My spleen was enlarged.

These are all signs. Other blood counts also had either gone up or down to levels that were not within range anymore. All these things that point to, “It’s time for treatment.”

Clinical trial

I was very interested in a clinical trial because at that time in 2015 there was only one. Things have just changed. It’s crazy, and it blows my mind when I think how much things have changed in six years.

There was pretty much the gold standard of treatment, which was FCR. It is by infusion, and it’s basically fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and Rituxan.

There was a trial open that I was offered. It was for young — and I’m young for CLL — and fit patients. Here I was, in the gym almost every day. At that time, actually, I had started running. I fit the criteria.

At the time, either they had said it could be curative or to put me into full remission and keep me there. I was like, “Yeah, sign me up.”

What I didn’t realize when I was signing up is that it was with ibrutinib, an oral treatment, which became the next gold standard of treatment. I was on full strength of both simultaneously for six months, and then I just continued on with the ibrutinib, the oral BTK inhibitor, which many CLL patients out there could be on or had been on or will be on.

»MORE: Clinical Trials in Cancer

Side effects going away

Within a couple of weeks, almost overnight, I felt like my lymph nodes had melted.

I had had what they call night sweats, which are like hot flashes, and I had them morning, noon and night. I was just a furnace. I froze everyone out of my house. We shared a summer home with another couple, and I froze them out of that house. They would push up the temperature. I’d be like, “I can’t. I’m so hot.”

I was on two full-strength treatments simultaneously for six months. Most patients do one or the other, and yet all of this was happening to my body at once.

That is another sign that it’s worsening. I also had had another sinus infection, which was the worst ever. I thought I had experienced the worse ever. These are all signs that they saw that my immune system was deteriorating due to my disease that was progressing. These are things that do happen to CLL, not all CLL patients, but some.

It was just amazing. The night sweats stopped within a few weeks. Just so much of what had happened to me seemed to be getting better. Then I started with chemotherapy side effects that a lot of people have. It’s a bit of a trade-off, but I knew that there was a light at the end of the tunnel for the first six months.

Increasing fatigue

My fatigue increased. I also had fatigue with CLL. It got progressively worse and worse the closer I got to time for treatment. Fatigue is another big factor that I hadn’t mentioned for most patients. By the time I started treatment, I was taking naps every day, which is like against my religion.

I always think that’s what you do when you get old, but I had to give into it. Then when I started treatment, I absolutely eventually had to nap earlier in the day because infusion chemo is cumulative. I never thought about it at the time, but I was on two full-strength treatments simultaneously for six months. Most patients do one or the other, and yet all of this was happening to my body at once.

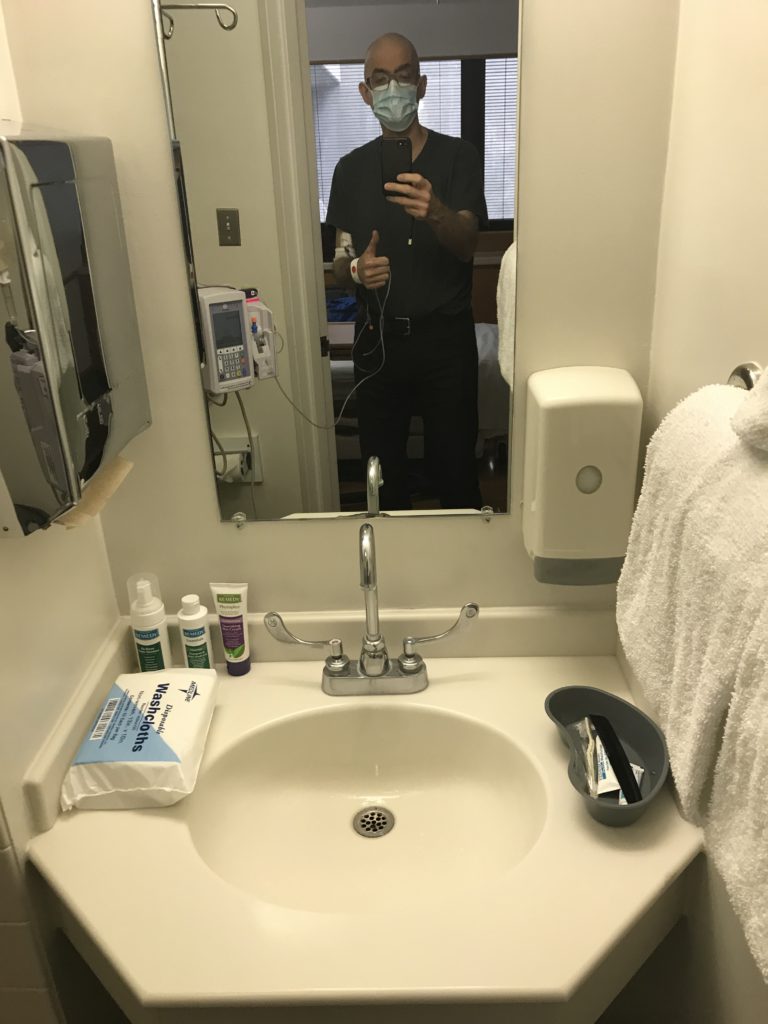

Ibrutinib and FCR regimen

With the ibrutinib, you take two pills daily — no stops, it’s just continuous treatment — and concurrently the FCR. For FCR, you would be at the hospital as an outpatient for four days a month. It was by infusion, and that was for six months. It wasn’t a full day once they figured out the speed of your chemo, of your drip. In the beginning, it took much longer. By the end, I was zipping through in four hours.

Dealing with the side effects

I never stopped going to the gym and working out. I hired a personal trainer because I didn’t trust that I would be able to judge what I could and couldn’t do, and I still wanted to be pushed a bit, but safely.

I made sure I hired one that had a great background in physical therapy and physicality. I did that three days a week and did yoga another day. Every week except my infusion week, I did this.

For me, that was one way also to keep control of my body. I felt like it was controlling me or others were controlling it. This was my way to be able to control something.

Her name is Amanda Kelsey. She was able to judge my energy level somehow. She was able to read my energy levels and tailor my workouts without my realizing she was doing this. One day I asked her, “How did you know I was tired today?” She would know; that was great.

There are studies that show that you have less side effects if you keep active, if you move and have some kind of movement during treatment.

Neuropathy

I had neuropathy in my feet at times. Not constantly, but at times it would hurt to walk. For those of you who follow Kicking Cancer in Heels, I wasn’t able to wear my highest of heels in those days because it hurt too much.

It’s happening again now that I’m back on treatment, but I had a hard time holding on to things. I remember picking up a jar of spaghetti sauce in the supermarket, and it fell out of my hands. Of all things to fall! I was so embarrassed. It would hurt to hold hand weights, and I didn’t have strength to grip.

These are pretty common with many chemotherapies. They’re not fun ones, but there are worse. My fatigue, though, is really profound and one of the worst of my symptoms, and I wasn’t able to go at my normal pace or even half my normal pace.

There were others, as well, but at the beginning I wasn’t sure what it was from. Was it FCR? Was it ibrutinib?

Dermal reactions

I also had a lot of dermal reactions. I started breaking out in hives a lot. Redness, red, splotchy things on my face. I had to start seeing a dermatologist, and I learned it’s better to go to one that specializes in oncology because they know what to do.

If you can find one, there are only 51 or 52 institutions in the U.S. that have them. I didn’t know that. I was just, again, so lucky to be going to a cancer center. Ask them if maybe they know of them or can refer to one that’s local for you.

It was a game changer. All she had to do was look and, in a second, know what it was. From what I understand, various chemotherapies do this. It’s not just the ones for CLL. They do know what to do if it’s somebody who understands the effects of oncology drugs and your skin.

Treating dermal reactions

Also, I learned how to cope with each of the different things that happened. A lot of strange things happened. It would break my heart when I’d see online chat rooms on Facebook and patients would say, “I’m going off my treatment because of my skin side effects.”

I would feel so badly and and try to answer. I’ve done reports on all the different things that you can use. Sometimes it’s just a particular ointment. Sometimes for hives Benadryl is the best, but that knocks me out. But at least they go away. I’ve been trying to use both.

Someone had said a couple of antihistamines can help. There are different ways, but there seems to be something for almost everything on these particular side effects for that. None of those were horrible things to do. It wasn’t like you had to do anything drastic. Again, being your own patient advocate, pushing, asking, “What can I do? This isn’t working for me. Can I see someone? What can I have that can help me?”

»MORE: Cancer Patient Advocate

Treatment from September 2015 to May 2019

Until March of 2016, it was everything. Then at that point, it was just ibrutinib, and ibrutinib you stay on indefinitely. By the way, I so encourage people to go in a phase 2 or later clinical trial because that means the dosage has already been determined. You don’t have to worry about that part of the trial, if you have choices.

Some patients have already gone through all kinds of treatments. This would not be a first-time patient. They do sometimes go on a phase 1. For those of you who have never been in treatment, phase 2 or later is like getting tomorrow’s treatment today.

For me, ibrutinib had been approved for relapsed patients, but it hadn’t been approved for those who have never been treated. I couldn’t have gotten that drug otherwise if I wasn’t on the trial. FCR, on the other hand, is not used that frequently. This trial that I was on, now the results are in after all these years.

Unfortunately, I’m one of only a few patients — and I want to say it was 89 percent of the patients went into the Holy Grail of CLL, which is called uMRD, which is undetectable minimal residual disease. Of course, I had to be one of the few holdouts. I almost reached it. Almost very, very close. It put me into a very deep remission, a deeper remission than if I had just been on the ibrutinib.

I stayed on the ibrutinib quite a while, about three-and-a-half or four years, until my adverse events or side effects became so untenable. The fatigue was really one of the worst because I was working, but I couldn’t work at full speed, nor could I really work full time yet as long as I was on it. Because of that, I took a bit of a drug holiday and stayed in my partial remission until I relapsed last year.

»MORE: Newest CLL Treatments

Continuing treatment and quality of life

Having both FCR and ibrutinib and that I was in the first cohort — they kept telling me the fatigue was from treatment in the beginning. After a year after treatment and I was still tired, then they started trying to figure it out. It’s not like there were other options at the time, and then other options started happening. The drug was working beautifully, other than one lymph node being bigger than it should be.

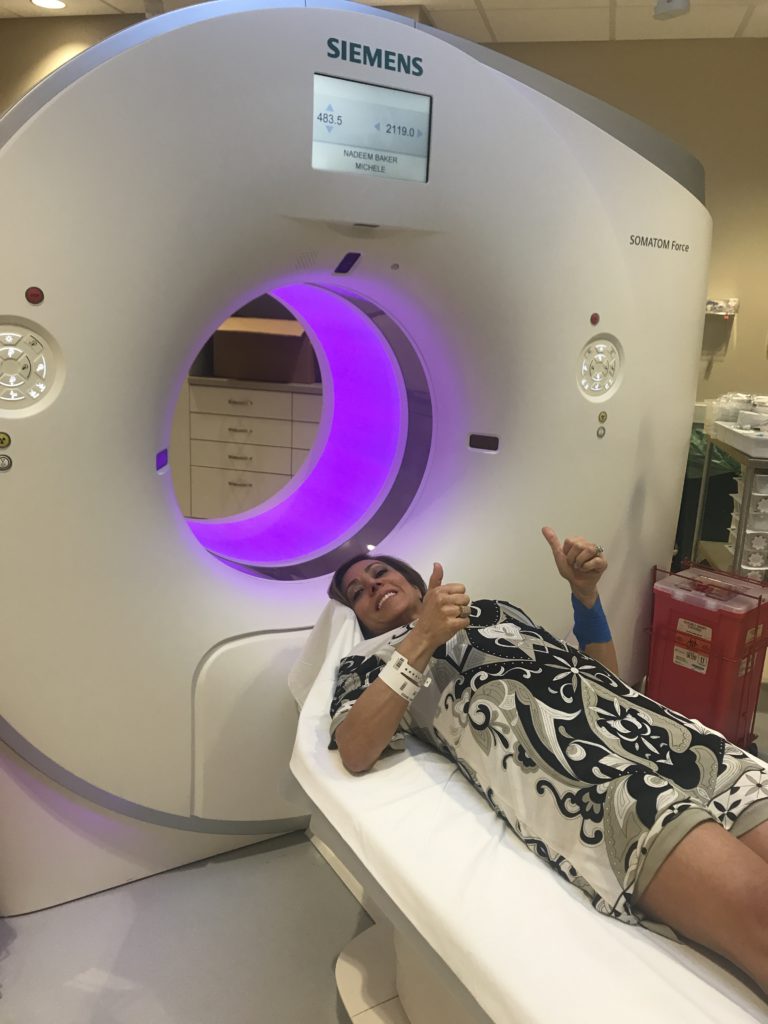

Bone marrow biopsies on a trial are done more frequently than otherwise. Some patients never even have to undergo a bone marrow biopsy. In the first year of the trial, every three months I had to have CAT scans and a bone marrow biopsy. The bone marrow biopsy is more precise than a blood test to find out what percentage of your bone marrow is infiltrated by your disease.

When I went into treatment, I was at 91 percent infiltration by my CLL, and when I heard that I was like, “Oh crap, I really should be on treatment.”

You want to be on treatment in the beginning, and then after you get used to not being on it, it’s like, “Treatment? Oh my gosh, I have to go on treatment now?”

It’s the irony of this. In other ways, I was so happy to be on treatment because for me, I was confident I was getting better versus getting worse. That is a turning point.

I think also when patients have been on treatment, they know what it’s like. They don’t get as nervous perhaps for the next one. You still get nervous, but you know what it’s like, and you know that you’re getting better.

Going off treatment

Finally, I did say that it was really affecting my quality of life, and that’s when my doctor started suggesting I go off of it. I felt so miserable, but she wanted me to go off. I was afraid to go off because I knew I was staying, as odd as it sounds, healthier on it.

We actually had a tug of war with the bag with the ibrutinib in it. I pulled it towards me. She pulled it towards her. I pulled it to me.

I’m like, “But I have to stay on.

She’s like, “No, you’ll be okay.”

Finally, I let her be the victor because it honestly was great being off treatment. I was able to find out that, yes, I still had energy. That was the other thing, trying to explain to the doctor the real me that she had never met. Well, she met in the beginning when I was working.

Here I am, back to work, able to work tons of hours and still do all sorts of other things. All they see is you as a patient. You have to explain really how you are. I was able to prove to myself — which I needed to — that yes, once again I could get back to having a lot of energy.

I’m glad I was able to do it. It was wonderful seeing that I am still the person I thought I was, and I could still have energy and that age hasn’t taken over. Things didn’t change from having been on treatment, because that’s the other thing you don’t know. Have I changed? Has it changed me?

»MORE: Working During Cancer Treatment

What was it like going back on treatment?

It actually ended up being two years before it started being noted as being progressing, but it wasn’t time for treatment again yet. You have to wait until it gets worse. It presented itself a little differently this time, and it became more aggressive toward the last two months before it was time to go back on treatment.

I wasn’t happy that I had to go back on treatment, but I did know that I would because it is a chronic disease and the majority of patients do. I was hoping I would have gotten a little longer without treatment, but that didn’t happen, especially with COVID.

When I stopped treatment, it was maybe only ten months before people went into lockdown with COVID. So I just kept thinking, oh gosh, when am I going to be able to live life? That’s another reason why I wish it had lasted longer but I’m back on.

Choosing between treatment options

I didn’t know which treatment to go on, so I once again, got a second opinion and a third opinion this time. I am really happy I did because the good news is there are so many choices right now to go on, which was so different than when I first went on treatment when there were hardly any choices.

There’s no cure yet, but a lot of the specialists say there will be a cure for us to look forward to.

There are so many choices that it was kind of hard to decide. Also, there were so many trials. I opted to go on the next generation of BTK inhibitors, something called acalabrutinib, otherwise known as Calquence.

I was waiting for a phase 2 of a particular trial that my doctor had suggested and that I had spoken to others about. By the way, the second opinion you get should really be from a CLL specialist. Even if you don’t see a specialist, I suggest you talk to one for a second opinion.

I am considering going on a trial in the future. The original one we thought of is no longer one that we’re looking at, because I am doing so well on the drug that I’m on. We may add in another drug potentially to put me into a deeper remission again, so that’s what’s next.

What is most important to you when deciding the path to take?

Every patient is different on what works for their lives or not. I was hoping to have finite treatment. That’s not as important to others. Some people are fine staying on indefinite treatment, and it’s easier for them really to just take a pill. It’s much more serious than just taking a pill like a vitamin.

I don’t want to minimize what it is, but their lifestyle versus having to worry about infusions or worrying about being overnight in the hospital for any particular treatment that you have to go through or from being monitored.

I really did want finite treatment, and that’s not what I have right now. I’m doing really well with the drug I’m on, which is wonderful. I would still love to have finite treatment. The things you have to look at is, “What’s right for you? What will work for you?” What works for me may not work for someone else.

Again, some of this has to do with how many times you’ve relapsed or if you’re new to treatment. It has to do with certain treatments. It depends on the things that we were talking about before, your prognostic indicators.

Those are like 11q, 17P, TP53, and IGHV mutated or unmutated. I don’t have the worst, but I don’t have what they call the best. I’m somewhere in between. I have two of those.

Then for some patients, one works better than the other. There are all these combinations of treatments on top of that, like endless combinations and endless trials, which is really wonderful for us. There’s no cure yet, but a lot of the specialists say there will be a cure for us to look forward to. I do hope for that.

Being on acalabrutinib

Ibrutinib, you take your pills once a day. Acalabrutinib, you take it twice a day, for me anyway. Different patients sometimes take less. There are sometimes side effects on this that go away. In the beginning, just like most patients, I had horrible headaches, but not all the time. They go away within a few weeks.

If you drink coffee, which I try not to later in the day, then it goes away. They know this now because the drug’s been around a while. You can also take Tylenol.

It has less side effects than the ibrutinib because it is a newer drug with less toxicity. I have only one other real side effect, and that is — we’re unsure if it’s neuropathy or joint pain — in my hands. That’s something yet to be determined, and that too could go away. I’m hoping for that.

Finding Purpose in Cancer

Video

How did you work through the identity shift of having cancer?

It is such a difficult thing, and it was one of my hardest challenges with the diagnosis and trying to figure out who I am. When no one else was home except our dog — I would talk to her because she was safe — I would just sit on the floor and cry and say, “What am I supposed to do with this? What is my purpose? I need to do something. I don’t know what my purpose is.”

One of my friends said to me two weeks after I was diagnosed, “What’s your new dream?” I’m like, “I don’t have any right now.” Then that sat with me. I have no dreams because I knew that I couldn’t go back to the schedule I kept in my career. Even if you’re healthy, you probably end up not healthy because you really should sleep, and you shouldn’t be working all those hours. I kept trying, so what is it?

Finding purpose again

It’s interesting that the day I started chemo is the day I started reporting from the infusion chair. I didn’t realize that was my purpose yet. I did it to help others and to demystify it.

I learned that actually made me feel better because even though I still didn’t realize it was the purpose, it gave me a purpose. It kind of gave me a job when I went to chemo and infusion. I didn’t really think about it as much. It was just like, “It’s my job here to report on what this feels like.” I was living in two worlds.

Once I started feeling better, I took on clients as a communications and PR consultant. I’d work with agencies for their clients, and I was doing my patient reporting. I started doing more and more in the patient influencer and advocate community.

When the first Wonder Woman movie came out, I saw it. I know this may sound silly, but Wonder Woman jumped into battle ahead of all of the troops — men, because it was World War Two in this movie — and she just went head on into battle with everything firing at her, and she used her cuffs to fight them off like my cuffs.

Wonder Woman and fighting cancer

I started using that for visualization for many things. I could never really get into meditating and visualizing different things in your body and it being disease free. Suddenly I had something to count on. It was in my brain. I was fighting off those cancer cells. My husband went on Etsy and got me each piece of the Wonder Woman costume uniform. He was in the military, so to him, it’s my uniform.

I have a real metal shield. We’re not talking plastic here. Swords and the cape, the whole thing, the crown. I’ve got it, and it really helps me fight off my cancer in my mind. Also, it’s given me the power to move forward in my patient advocacy and in fighting off my CLL. I know that I can be Wonder Woman and fight it off and be the victor and have the strength for that. I try to think of it now as going into battle against my disease.

»MORE: Kicking Cancer in Heels

Patient advocacy and coexisting with cancer

What I’ve done won’t work for everyone because we are now immersed in the cancer world for work and ourselves. I’m able, probably through journalism training, to separate it.

When I’m doing the work, I am not the story. I’m not used to being the story. It’s so much easier to be the one asking the questions versus being the one giving the answers. I’m able to separate things out.

Support groups

There is a close woman support group that another woman and I co-founded called CLL Women Strong. I invite any of you out there to join that, or also there are other support groups out there for virtual meetings.

There’s AnCan, which is for all blood cancers. They are online. There are so many on Facebook. One is just called CLL Support Group. I co-administer that with another fabulous co-patient, Jeff Folloder. There are just so many out there. There are CLL/SLL women’s groups. Find one you identify with because you can post things and people will answer.

They’ll be there to support you. You need people who understand what you’re going through. Support groups didn’t exist when I was first diagnosed. It’s also really hard to find other women and other women who are diagnosed at a young age and going through this. Now those things do exist.

Everyone’s kind of growing with technology in this, but also you’ll find kindred spirits that understand and you can identify with, because your family isn’t the place to always go to for this. They’re not going to understand, but don’t let that get in your way of finding what’s right for you.

Inspired by Michele's story?

Share your story, too!

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Stories

Nadia K., Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL)

Symptoms: Rash, lump under arm, fatigue

Treatments: Ibrutinib and acalabrutinib