Bill Faces Stage 4 Neuroendocrine Rectal Cancer With a Strong Community

Bill’s advanced neuroendocrine rectal cancer experience began most ordinarily: tiny, easy-to-dismiss drops of blood in his stool. He had just moved to Houston, started a new role in the pharmaceutical industry, and was settling into life as a new father when his primary care physician repeatedly attributed his concern to simple hemorrhoids. Even with a busy new life, Bill couldn’t shake the sense that something more serious was happening and kept pushing for answers. That insistence on being heard ultimately led to a colonoscopy and the news that he had neuroendocrine carcinoma in his rectum, diagnosed at stage 3 and later progressing to stage 4.

Interviewed by: Keshia Rice

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

Bill describes the shock of waking up from the colonoscopy, still sedated, and hearing the word “cancer.” He also speaks frankly about being a younger adult whose symptoms were minimized and how he chose not to live in the land of “what if.” Instead of dwelling on missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis, he focused on the choices still in front of him.

Over time, he moved through multiple lines of treatment, a major surgery that left him with a permanent double ostomy, and several clinical trials after standard options were exhausted, including studies opened by a specific genetic mutation. The therapies included FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, and an 18-hour surgery.

As the treatments accumulated, so did the lifelong side effects and the mental gymnastics of facing each new drug, scan, and possible progression. Bill discusses how uncertainty became a constant alongside his determination to remain as physically and mentally prepared as possible. That meant tending to close relationships, nourishing his body, and embracing something he calls “practice suffering,” using endurance cycling and running to train his mind for the hardest days of treatment.

Throughout the advanced neuroendocrine rectal cancer experience, Bill also had to rewrite his identity as a man, a father, and a provider. He reflects on how cancer stripped away old concerns about status and appearances and sharpened his focus on service, advocacy, and time with his daughter. Sharing his story publicly has become part of that purpose. By speaking out about a rare, aggressive cancer, he wants future patients to have better options, more research, and the sense that they never have to go through this experience alone.

Watch Bill’s interview or read his transcript to learn more about his story:

- How self-advocacy can be lifesaving

- Why treatment response is not about personal failure

- How cancer changed how Bill sees his identity, values, and priorities

- What it has been like living with a serious illness

- Why patients are encouraged to seek support, speak openly, and get involved in their care

- Name: Bill T.

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 33

- Diagnosis:

- Neuroendocrine Rectal Cancer

- Staging:

- Stage 4

- Mutation:

- ATM

- Symptom:

- Drops of blood in stool, recurrent over several months

- Treatments:

- Chemotherapy: carboplatin, etoposide, capecitabine, FOLFOX, FOLFIRI

- Radiation therapy

- Surgeries: liver ablation, permanent urostomy, permanent colostomy

- Targeted therapies: PARP inhibitor, ATR inhibitor, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT)

- Monoclonal antibody: vedolizumab

- Hormone therapy: somatostatin analog (lanreotide)

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- Neuroendocrine Rectal Cancer Diagnosis at 33

- Life and Career Before My Cancer Diagnosis

- My Early Symptoms of Neuroendocrine Rectal Cancer

- How I Advocated for My Own Cancer Diagnosis

- Hearing My Colonoscopy Cancer Diagnosis

- Being Diagnosed With Cancer at 33

- Coping Without Dwelling on ‘What If’ in Cancer

- Telling My Family About My Neuroendocrine Cancer Diagnosis

- Having Hard Conversations and Taking Ownership of My Health

- My Neuroendocrine Cancer Treatment Journey Through Nine Lines of Therapy

- How I Cope With Uncertainty and Ongoing Cancer Treatments

- How Cancer Changed My Relationships and Support System

- Using Exercise and ‘Practice Suffering’ to Cope With Cancer

- Running Marathons and Ultramarathons With Active Cancer

- Training Through Chemotherapy and How Other Patients React

- From Feeling Betrayed by My Body to Learning From Cancer

- How Cancer Changed My Identity as a Man, Father, and Provider

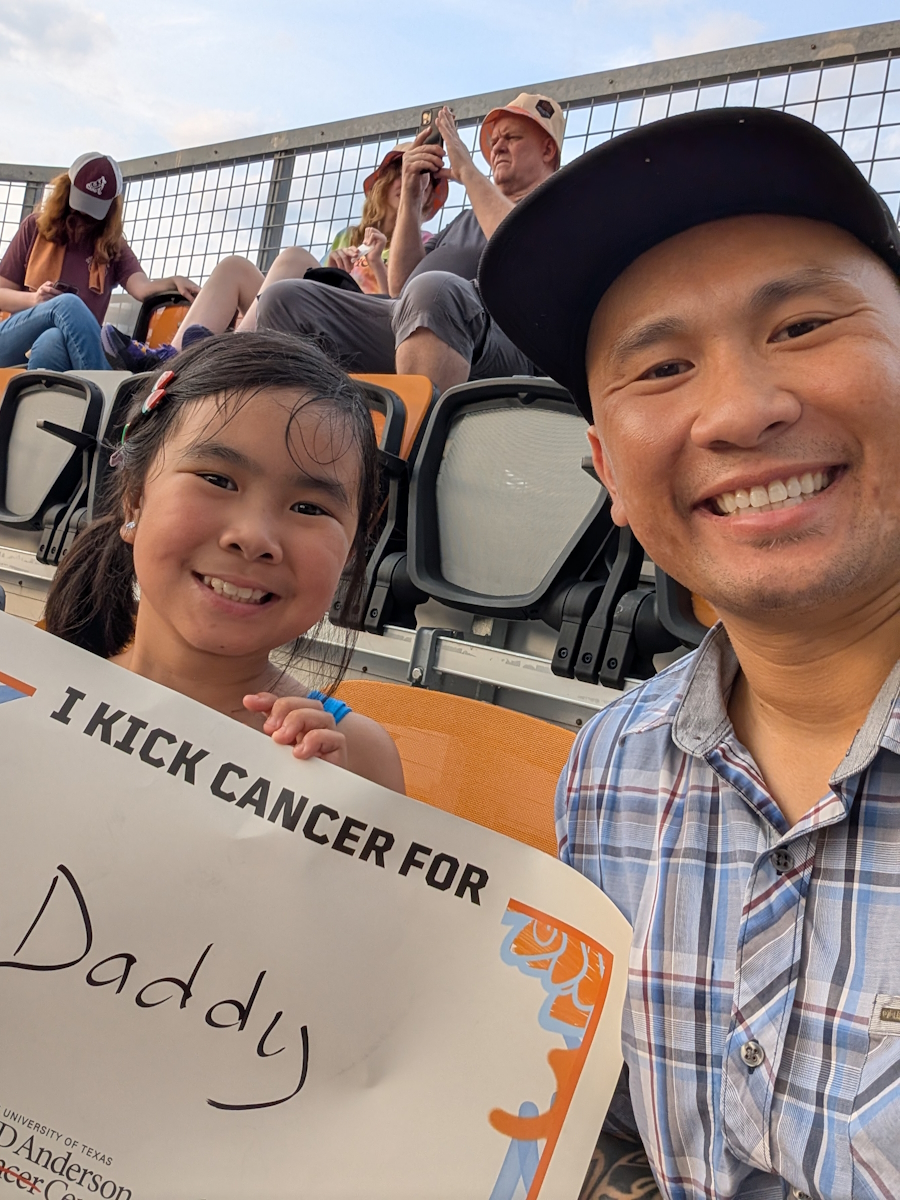

- Parenting With Advanced Cancer and Talking to My Daughter About It

- Why I Share My Rare Neuroendocrine Cancer Story Publicly

- Life After Leaving Work and Becoming a Full-Time Cancer Advocate

- My Hopes for the Future and Supporting Men With Cancer

- Redefining Strength for Men With Cancer and Embracing Emotion

- My Advice to Other Cancer Patients About Community and Survivorship

Neuroendocrine Rectal Cancer Diagnosis at 33

My name is Bill. I’m from Houston, Texas. I was originally diagnosed with stage 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rectum, which later progressed to stage 4. I was diagnosed in November 2018.

Life and Career Before My Cancer Diagnosis

I moved to Houston from Southern California in 2016. I was going to start a new role in the pharmaceutical industry in bladder cancer, which was a coincidence that I ended up getting cancer. I had recently started a new family, a new career, and built a new home. Everything that happened right after was a huge shock for me.

My Early Symptoms of Neuroendocrine Rectal Cancer

My symptoms were not very prevalent. There were drops of blood in my stool, but they were hardly noticeable. I always brushed it off because it would happen and then go away, but it would recur for about three months.

At the time, I was looking for a new job and when I did, I had benefits starting day one, which was great. I went in to see my primary care physician (PCP), who attributed the symptoms to hemorrhoids, but I didn’t accept that explanation since it was constantly coming back, so I pushed for blood work and a CT scan. They appeased me by doing what I asked, but when I came in for my follow-up, the PCP still brushed me off and said it was hemorrhoids.

Then I thought maybe it had something to do with my autoimmune issue. I have spondyloarthritis, which I’ve had for close to two decades. I went to see my rheumatologist to tell him my symptoms and he told me that this has nothing to do with that. He then referred me to a gastroenterologist, who scheduled me for a colonoscopy, which is how I discovered the tumor in my rectum.

How I Advocated for My Own Cancer Diagnosis

Part of it was a gut feeling. At the same time, I wasn’t satisfied with the answer I was getting. I already assumed that he was going to say hemorrhoids, but I did the research and this was not hemorrhoids. I needed confirmation and validation of what I was worried about. I needed additional testing to get an answer.

He didn’t even show me the images or go over my scan. He simply told me it was hemorrhoids. I said, “We need to go over the scan.” I sought out another clinician, who did what the previous clinician should have done, and that’s when I felt heard. But because of all this delay, I get my answer, which wasn’t a good answer.

Hearing My Colonoscopy Cancer Diagnosis

Getting the diagnosis was interesting. As you wake up from a colonoscopy, you’re somewhat drugged up, so you can’t fully feel the news. You have all these thoughts rushing through your mind. I was not expecting cancer. It was a shock and it took me some time to process.

Being Diagnosed With Cancer at 33

Automatically, I thought, “He’s a piece of s***. I can’t believe he missed this.” But over time, I thought that sinceI was so young, you don’t think cancer or even assume it, so they automatically think it’s hemorrhoids. I could understand his observation and way of thinking, but it also hurt because I wasn’t heard.

I’m glad that I advocated for myself in terms of finding another opinion. I wouldn’t say that opinion has saved my life, but it gave me enough room where it wasn’t stage 4 in the very beginning, so I had enough time to prepare for what was to come.

Coping Without Dwelling on ‘What If’ in Cancer

There’s no point in dwelling on the past. It’s easier to move on. I’m the type to not dwell on the past. I prefer to move forward and take on what’s in front of me. It’s helped me with my diagnosis to this day. I talk to so many patients who constantly question what-ifs and it destroys them psychologically, which can easily equate to physical effects. I didn’t want to go down that rabbit hole.

Telling My Family About My Neuroendocrine Cancer Diagnosis

It’s easier to be blunt. I didn’t know the severity of everything. When I finally got my pathology, I did what everybody does when they get diagnosed with cancer, which was consult Doctor Google. All the literature I read was bad: very short-term survival, very low percentage of survival rates past five years, not enough treatments offered, and majority of treatments failing.

Then I confirmed it with my colleagues. I would talk to them and they told me this wasn’t a good cancer to have. There’s no such thing as a good cancer, but having a rare aggressive cancer increases the anxieties brought upon the person. At the same time, I’m not the type who will basically bury myself in sorrow. I thought, “I need to do everything humanly possible to increase my chances of survival, regardless of whether it’s one, two, three, or whatever number of years. As long as I could survive as long as I could, that’s the best that I could do.”

Having Hard Conversations and Taking Ownership of My Health

It was difficult, but necessary. I understand that part of being an adult is having uncomfortable conversations. I understood the reality of my prognosis as well as the diagnosis, but at the same time, I understood the fact that I still had accountability in my survival. I would be accountable for my mental and physical health, what I put in my body, how much I moved, and everything beyond. We could easily fall into the trap of doing nothing and that wasn’t for me.

My Neuroendocrine Cancer Treatment Journey Through Nine Lines of Therapy

I’m fairly high up there in terms of the amount of treatments that I’ve had. I’ve been through nine different lines of treatment. My first line was carboplatin and etoposide. The next was 25 rounds of radiation and capecitabine. The next was FOLFOX. After that was FOLFIRI.

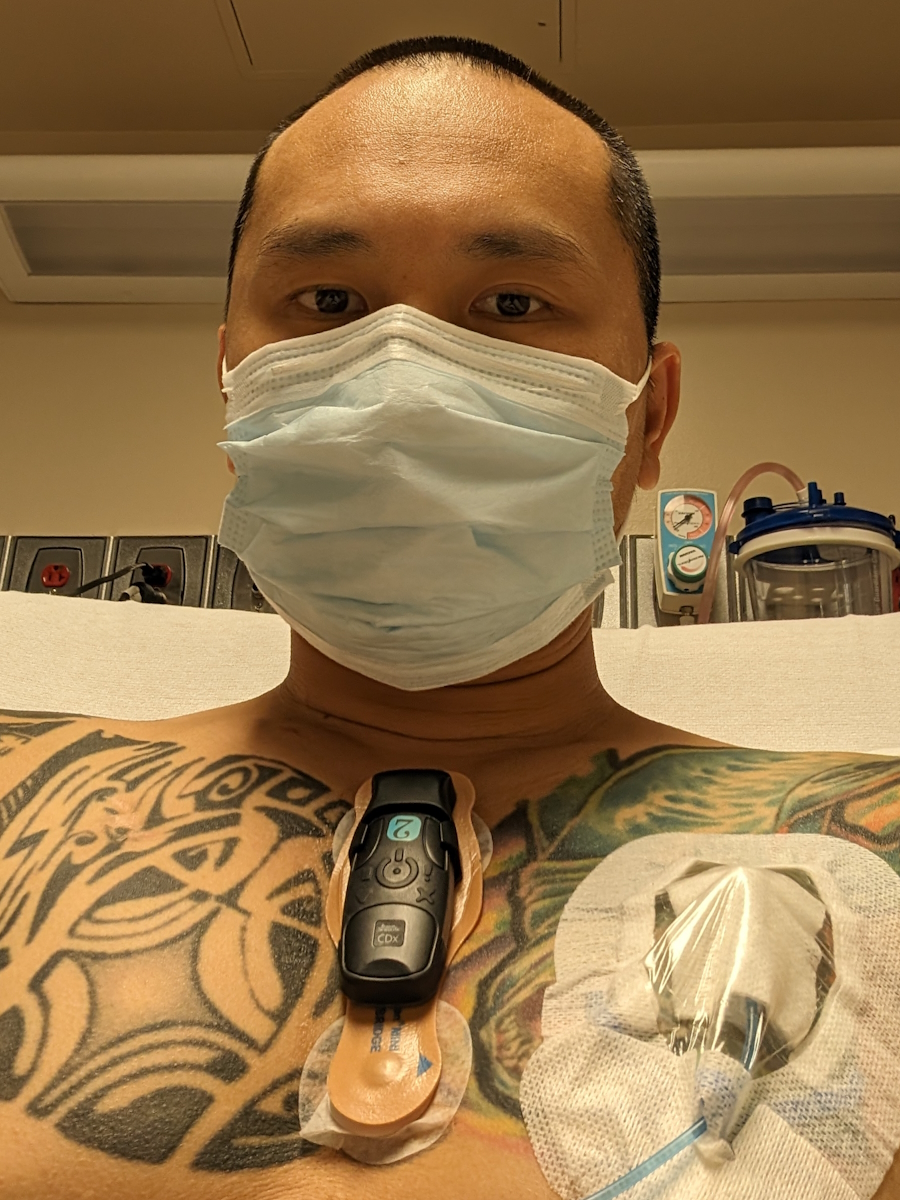

Following that, I had an 18-hour surgery that left me with a permanent double ostomy: a urostomy and a colostomy. Even after 18 hours, the surgeons weren’t able to get everything. I had four surgeons and a radiation oncologist, and they told me that they needed to bring me back in three months to get the residual tumors. We did a liver ablation and thought I had some breathing room.

Two months later, I had a recurrence in my liver. We had some biomarker testing done on my tissue and my blood, and found that I had a genetic mutation called ATM. Though the mutation is typically seen in breast cancer patients, it was great because it opened the doors to clinical trials because I had exhausted all standard of care treatment for my type of cancer.

I’ve been through four clinical trials. The first one was what’s now called olaparib and RP-3500, which is a PARP inhibitor and an ATR inhibitor, and lasted about 23 months. The following treatment was an immunotherapy clinical trial with vedolizumab. I did two cycles and had a bad adverse reaction that landed me in the hospital for 12 days. I had to be off treatment for about five months to recover from the adverse effects.

Then we moved to another clinical trial, ART6043, which was another PARP inhibitor. That didn’t last very long. I moved to another clinical trial, which was another PARP inhibitor, but that failed as well.

My oncologist looked back at my records when I was initially diagnosed. This was somewhat of a Hail Mary because he said that there was activity in my pelvis for somatostatin receptors. He moved forward with another dotatate scan and found my cancer lit up, which was interesting. Typically, those receptors aren’t seen in patients who have neuroendocrine carcinoma, so there’s a pro and a con. The pro was that we found it lit up. The con was that they were in even more parts of my body, so I had even more cancer than I thought.

At the time, I only had cancer in my liver, lungs, and pancreas, but the dotatate scan showed additional lesions in my chest, pelvis, and parts of my bones. We went through the insurance approval process for lanreotide and peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), which has kept me stable until today.

I’ve had nine lines of treatment. For my type of cancer, I have to think two or three lines ahead because everything has a shelf life. The hardest thing about survival is that every drug that I jump on is a new accumulation of lifelong side effects. At the same time, the mental gymnastics of needing to jump on another drug, having the hope, anxiety, and understanding that to stay alive, I have to repeat this in a perpetual state of déjà vu.

How I Cope With Uncertainty and Ongoing Cancer Treatments

Uncertainty is a guarantee in life, just like death and taxes. I’ve learned to live with it by understanding that this is always going to be present. But at the same time, I could mitigate these anxieties by preparing myself physically and mentally through having good relationships, making sure that I’m eating and hydrating well, getting sunlight, leaning on community, and doing something I call “practice suffering.”

I engage in endurance activities where I’ll run and cycle. A lot of the time, I don’t want to because I feel the side effects of treatment. But being able to do things that make me feel uncomfortable, especially when I don’t want to do them, builds a level of resilience and makes me ready for unpredictable moments, such as going through all these treatments. When I come out on the other side, I continue to build on that resilience, which levels me up for anything that comes my way.

How Cancer Changed My Relationships and Support System

My family played a huge part. My mom has been with me through thick and thin. Even though she doesn’t know how to fully communicate with me on how for me to go through this, she has always made sure that if I needed something to eat, she makes it for me. If I needed someone to watch my daughter, she’ll do it. She’s unable to support me financially and in other ways, but she does what she can, which is all I need.

My brother and my sister have always been there for me, checking in on me. I’ve lost friends, but I’ve also gained a lot of friends. I feel that cancer simplifies life in that the relationships that you think you had that were great are put to the test. Cancer is one of those diseases that filters who is there and who isn’t there, who is superficial and who is only there to ride the wave with you. It’s a pleasant surprise finding new friends who I wasn’t very close with before but have become great friends in the long-term because they’ve been there, checking in on me, and constantly there to support.

There are people who have accepted the new me. Some people think that once I have stability with my disease, I could go back to being the old me, which is impossible because cancer changes a person — not for better or for worse, but because their outlook on life has completely changed. I hold those people very close to me now because they’ve seen me at my worst and can also handle me at my best.

Using Exercise and ‘Practice Suffering’ to Cope With Cancer

It helped that I already had a desire to be physically fit since the very beginning. I was already very into fitness. Over time, there were days when I couldn’t even get out of bed. Brushing my teeth and getting out of bed were probably the hardest things to do.

There were times during chemotherapy or when I’m on high-dose steroids that I experience pretty bad insomnia. I’m the type of person who can’t sit still, so I would walk around my room or around the house. Then it progressed to walking around the neighborhood at odd times of the day. Later, my dad shipped me a road bike, so I started riding my bike around the neighborhood. The distances kept getting longer.

I never liked running, which is funny. I’ve always viewed running as punishment because when I played sports, the consequence of doing something bad or not doing something correctly was to run a lap, so I would always hate running. But I also had a real curiosity because when I was on my clinical trial, I couldn’t run. After all, it would cause charley horses. It wouldn’t come from running, but when I tried running, it caused even more charley horses.

I would have three to five episodes a day because of the drug that I was on and none of my team could understand why. We did blood work and consulted multiple specialists, but no one could figure it out. I decided I would just continue cycling because the charley horses weren’t as bad. When that drug failed, I was curious to run, so I ran a mile and I was okay. I hated it, but at the same time, I practiced the suffering part, so I would continue increasing my mileage. I noticed I could go longer.

I heard about ultramarathons and thought I wanted to do one, which was funny because the longest run that I’ve done was a 5K with friends, a Turkey Trot. But being somewhat excessive in nature was a standard thing for me, so I decided to sign up for the Brazos Bend 50, an ultramarathon, which is a 50K. I started running in early January and the Brazos Bend 50 was going to be in April, so I was technically three months into running. It was one of those things where if I signed up, I was already committed and I don’t want to waste money.

But the other issue was that I was starting a new clinical trial, so I had to figure out the new side effects of this one. But I didn’t care. I ended up doing the ultramarathon and it was the most painful experience of my life. Once I hit marathon distance, it took me to a dark place. I had nothing but bad thoughts in my head because I was in so much pain. I’ve never run that kind of distance. Those moments when I was suffering and hated life taught me a lot about myself because I didn’t want to give up, but I also hated the fact that I was going through it.

It was a great reflection, as well as an introspection, of what an individual goes through with cancer. At the very beginning, they’re very excited. They’re very determined and will automatically say they’re going to do whatever is necessary to finish. But there are a lot of people who don’t finish the race. I see it in cancer as well. At the very beginning of a cancer diagnosis, you’re willing to do everything, but until you go through the treatment, the physical pain, the psychological pain, and when you’re hurting so badly, you think to yourself, “Can I get through this?” It’s a great comparison for me.

To go through that type of suffering daily helps me mindfully understand and be present with my thoughts and that this is only information for me to use in future moments. At the same time, it gives me accountability for my actions and how I follow through with anything. And that’s helped me to this day.

Running Marathons and Ultramarathons With Active Cancer

I haven’t run very many. Most of the time, I run on my own. The upcoming one I have is the Houston Marathon. My main goal for that event is to raise money for a cancer organization, to push the acceptance of people having cancer not going through it alone. This is the first marathon of one of my friends, Victor, so my only goal is to get him across the finish line. I couldn’t care less about my time. If I could help someone do something that they want to do, I’m happy. I’ve noticed that people always strive for a certain time, pace, or finish time. For me, it’s the experience. That’s all it is for me.

Training Through Chemotherapy and How Other Patients React

People don’t believe I have cancer because they say I can do a lot more than them, but there’s a lot of work involved. At the same time, people think about intensity, but for me, it’s about consistency. I always tell people I didn’t start here. I couldn’t get out of bed when I was first diagnosed. This is the result of seven years of consistent work and having no excuses. Everybody can easily have an excuse not to do something.

This has helped me psychologically and physically endure all the treatments that I’ve been on. You know what chemotherapy could do to you… I live with the fact that every time I sign my life on the dotted line, accepting this new treatment, I have to be prepared for the consequences. But that is part of trying to survive the disease that will ultimately kill us.

[Editor’s Note: Informed consent is a standard part of many medical treatments, including cancer care. These forms explain potential benefits, side effects, and rare but serious risks so patients can make decisions alongside their care teams. Treatments are recommended because doctors believe the potential benefit outweighs the risk for that individual. At the same time, signing consent forms can feel emotionally heavy, and this reflection speaks to the lived experience of making high-stakes decisions while living with cancer.]

From Feeling Betrayed by My Body to Learning From Cancer

Initially, I was very angry about my body, but at the same time, I was looking back at my lifestyle habits as well. I looked healthy, but I probably wasn’t healthy inside. Because I was young, I had a great metabolism. But when I look back and reflect, I didn’t have the greatest habits. I would binge drink. I would binge eat. I’d stay out late. I would constantly be exposing myself to radiation and everything, so I thought that, partly, that probably had something to do with it.

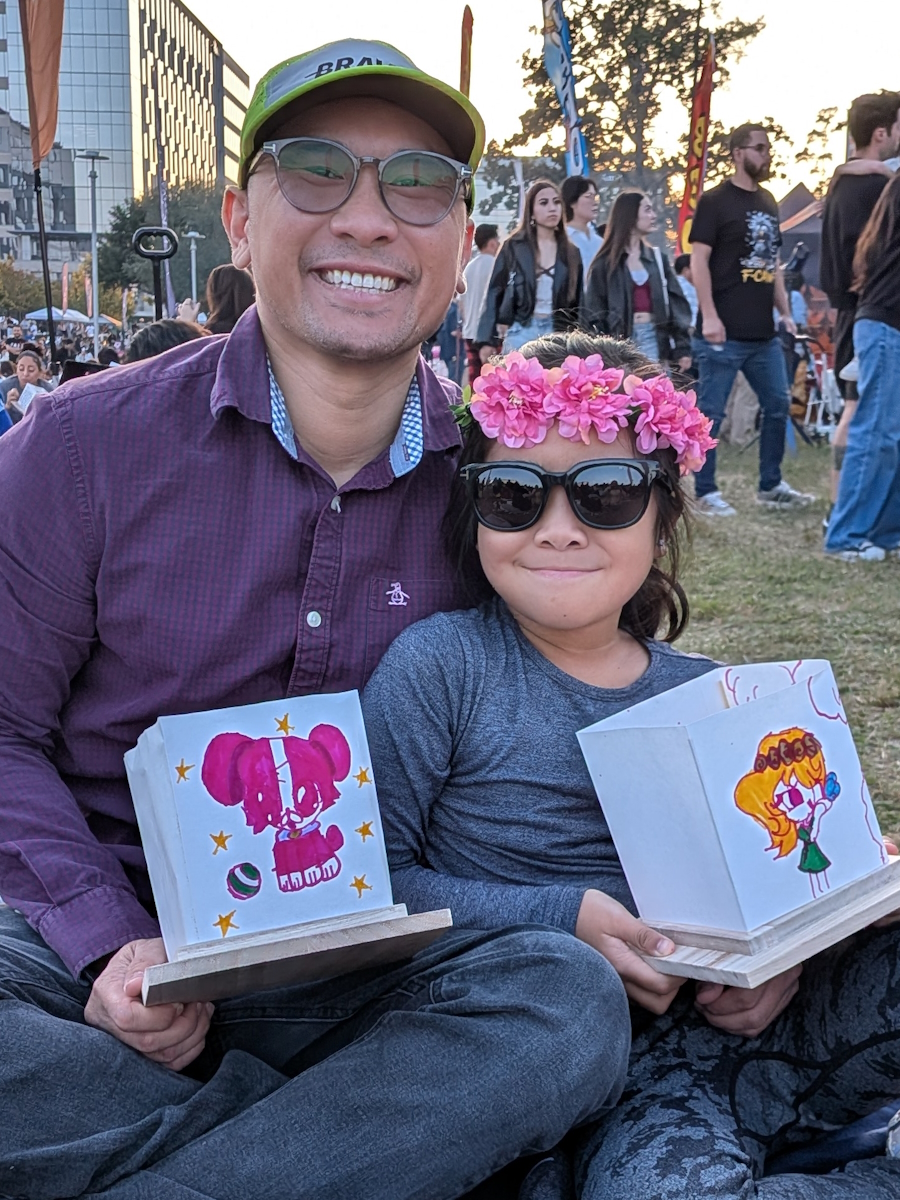

Over time, through introspection, I didn’t see my diagnosis as a death sentence. Cancer has been the ultimate teacher because it has narrowed my focus on what’s important. Some people never realize or understand what’s important in life. They think about what others think about them. They think about keeping up with the Joneses. They think about their superficial image to others. I no longer care about all of that.

I dress like a bum now. I don’t care if I have a stain on my T-shirt when I’m out. I will speak my mind. If I don’t like something, I will walk away from a person if I don’t feel that their conversation benefits me. I don’t care anymore. Before, I cared a lot about office politics, superficial images, and all those unnecessary things that make you unhappy. Now I care about my physical and mental health. I care about doing good and service. And I also care about making the next person who gets diagnosed with cancer make their journey less s*****.

How Cancer Changed My Identity as a Man, Father, and Provider

I constantly had to rewrite my identity through cancer. When I was initially diagnosed, I was a father, a brother, a son, and a provider. I was a person in this social circle. All that changed because of a diagnosis.

I no longer look like what I used to look like. I had to change careers multiple times. I had to rewrite my skill set. At the same time, I also had to surrender to the fact that life will never be what it used to be. And when I finally accepted that, things got better.

You have to give yourself grace in terms of what you’re going through. Cancer is something that I wouldn’t wish upon anyone because it’s one of the cruelest diseases that could be inflicted on a person. It destroys you on every level. It took years for me to understand that.

But at the same time, understanding that just because you get diagnosed with cancer doesn’t mean that it’s the end of your story. You could continue writing more chapters in your story to be who you want to be. Every day is a gift and every day is another day for you to become the person you want to be.

Parenting With Advanced Cancer and Talking to My Daughter About It

My daughter has seen me as normal as a person could be. She knows that I’m more physically fit than one of her friends’ parents. She also knows that I’m probably one of the most resilient people out there.

But I try to hide a lot of the struggle that I go through. As a parent, you don’t want your kids to see you struggle, but there’s also a danger in that because when they don’t see that, they don’t give the respect to the disease. I’m still figuring out how to discuss cancer with my daughter. She knows that I have it, but it’s one of those things where I struggle with trying to correctly explain it to an eight-year-old.

All she knows is that I have cancer. She was only five months old when I was diagnosed, so she has seen me go in and out of the hospital. She has seen me throw up. She has seen me so weak to the point where it causes anxiety and PTSD for her, so I try not to relive those moments for her.

It’s hard just because people think that because I can do what I do doesn’t mean that I’m not struggling psychologically and physically. I have so many side effects that some people would go crazy with all the side effects that I’ve had.

I have to see so many different specialists. People are surprised to learn that I see over 15 specialists. I’m only 40, but I have heart issues. Most people wouldn’t think that because I can run or cycle so much. But I do have heart issues. It’s one of those things where I tell everyone that, for a lot of people, cancer is an invisible disease, and they will never truly know unless they actually take the time to understand my story.

Why I Share My Rare Neuroendocrine Cancer Story Publicly

What I’m going through is not impossible, but at the same time, it gives light to people who are not comfortable with sharing their story that this is acceptable. It took me years to want to share my story because I was very private. But over time, I found that it’s part of the healing process in itself. It also gives a voice to other patients like myself.

I understood that there aren’t many people with my specific diagnosis telling their story or advocating for the disease. The majority of the people who have my diagnosis are struggling to survive. We don’t have a voice. I found that not having a voice equates to not having research dollars or any sort of awareness of the disease.

Many organizations are trying to find more treatments for my type of disease, but they don’t have patients stepping up. I found that by doing more advocacy within my field of cancer and within my subtype, having that voice and image outside in public is going to only help future people who get diagnosed with my cancer.

Life After Leaving Work and Becoming a Full-Time Cancer Advocate

I’m basically enjoying my retirement. I volunteer for different organizations in the advocacy space that focus on mental health as well as social and emotional support for men. I do research advocacy for Fight Colorectal Cancer. I serve on several research advisory panels.

I mainly want to use my time and efforts to make sure that the lives of future people who get cancer aren’t as bad and their struggles aren’t as rough as mine. I never saw the benefit of working through nonprofits, but when I received help and services from nonprofits, it totally changed my outlook.

My Hopes for the Future and Supporting Men With Cancer

I spend time with my daughter when I can, enjoying nature. I would love to visit more national parks and explore, meeting more cancer patients and helping them in their journey, furthering medical research in my type of cancer, and removing the stigma in men that they have to go through this alone.

Going through cancer as a male is very difficult because men tend to isolate themselves once they have a disease like this. The majority of the time, I see when men get cancer, their spouses or partners take the helm and do all the research, understand all the information, and the man basically has their head dug into the sand, knowing nothing about their disease.

I’m the exact opposite. I’m a very controlling person. I’m very type A. I need to know everything, so when I speak with my team, I know how to steer my conversation. But that is not what I see with the majority of the men out there. We need to remove the stigma that we could do this on our own — that’s what made me go crazy. When I finally accepted help, it’s no longer a weakness. It’s a tool. At the same time, it’s a way to make your journey and your progress in terms of your disease so much easier.

Redefining Strength for Men With Cancer and Embracing Emotion

Before, I was the typical man. Now, I’ve accepted and understood the fact that being able to talk about my emotions freely has been a game-changer in my life. I went to a retreat called Gathering of Wolves and saw a community where 100-plus other men were sharing their feelings and their anxieties, seeing that there’s no judgment. Being able to see that and experience that, and see that there is no judgment and fear of being ostracized and isolated into a different group, was empowering. It validated that everything I was going through sucked. And when I got a taste of that, I wanted to continue. I wanted to provide that to other men that I come across on my journey.

Man Up to Cancer has been a large part of my advocacy. They have helped me understand the role and benefit of what this can do for a person in their journey. I am part of the leadership team and one of my roles is to ensure that men of color are seen in this equation.

The majority of the time, men of color are diagnosed at a later stage in life, are less likely to seek out resources, and their prognosis and time of survival are shortened, and I’m making sure that I change that. I put in the effort to reach as many men of color as possible, as well as adolescents and young adults (AYAs), which is a very complex part of the equation for health systems because they have never seen this many young people getting cancer and they’re still figuring things out. Because I’m a man of color and an AYA, I want to further the progress of how medical institutions deal with this.

My Advice to Other Cancer Patients About Community and Survivorship

Being able to talk through your emotions, find community, and understand that your anxieties are information for you to process as well as implement in terms of how to deal with your disease are the most important things for a cancer patient to go through.

Survivorship after treatment is a very hard jigsaw puzzle to figure out. You need a team and a community to fall back on because, without them, you will basically be lost. Do not be fearful of seeking them out and trying as many as you can. Find a niche community that will help you navigate life, and you will never be alone.

Inspired by Bill's story?

Share your story, too!

Related Stories

Regina J., Lung Neuroendocrine Tumor

Symptoms: Wheezing, back pain, coughing that sometimes produced blood

Treatment: Surgery (partial lung resection)

...

Tabbie V., Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (pNET)

Symptoms: Abdominal pain, unusual organ "inflammation" feeling when walking, fatigue

Treatments: Chemotherapy (oral and IV), surgeries (Whipple procedure or pancreaticoduodenectomy, liver resection or partial hepatectomy)

...

Hayley O., Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (pNET)

Symptoms: Severe right-sided pelvic pain, nausea, diarrhea

Treatment: Surgery (pancreaticoduodenectomy or Whipple procedure)

...

Drea E., Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumor (gNET), Stage 3, Grade 1

Symptoms: Fainting spells, fatigue, dizziness, anemia, shortness of breath, absence of menstruation, unexplained weight loss, night sweats

Treatment: Surgery (total gastrectomy with a Roux-en-Y reconstruction)

...