Dr. Blue on Improving Myeloma Care for Black Patients

Interviewed by: Stephanie Chuang

Edited by: Katrina Villareal and Chris Sanchez

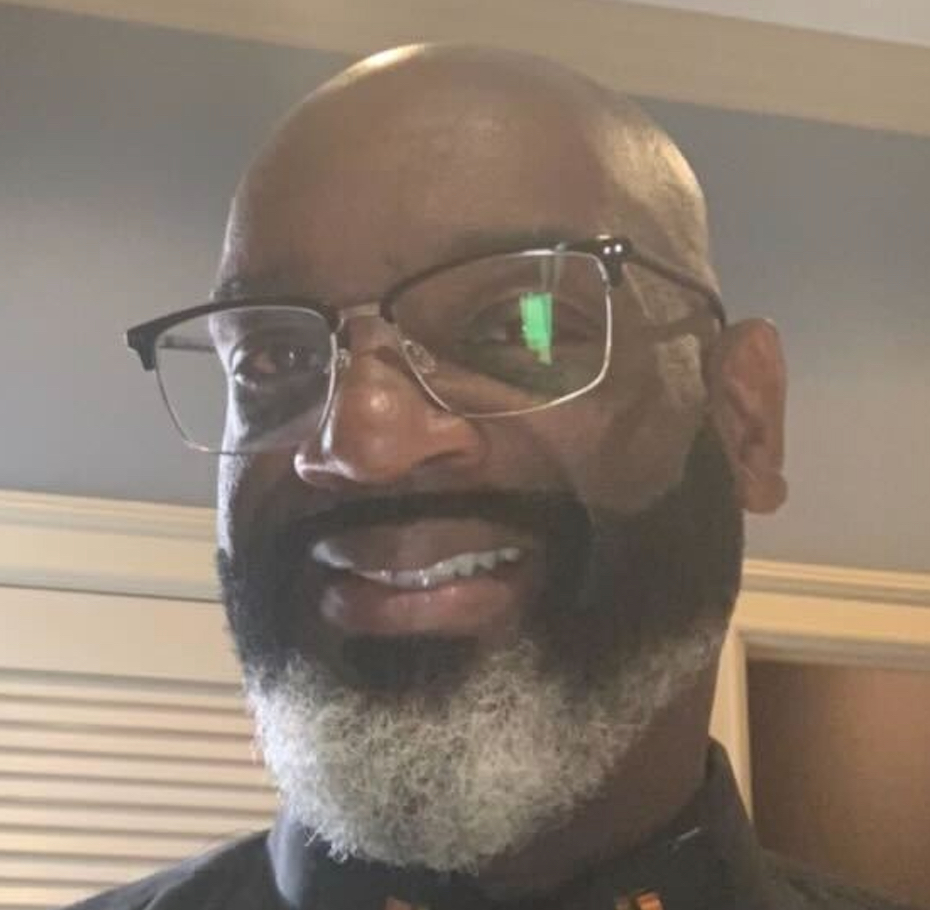

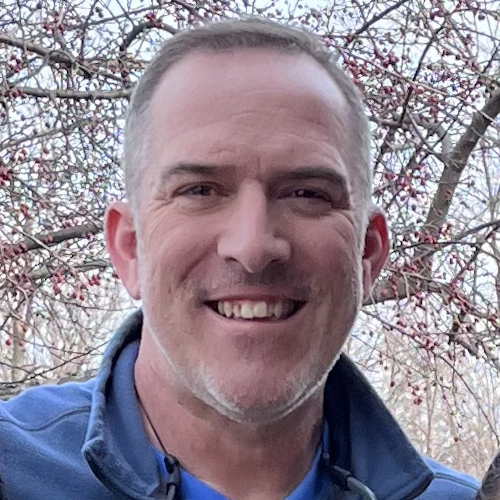

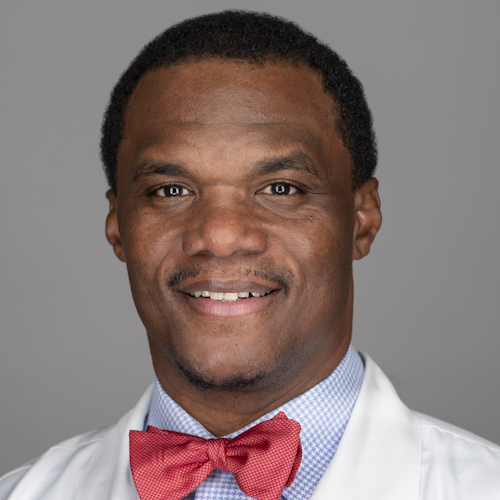

Brandon Blue knew at a young age that he wanted to help people. Decades later, he’s done that and so much more, changing and saving the lives of people who’ve been diagnosed with cancer. Now known as Dr. Brandon Blue, he’s become a well-known hematologist-oncologist at Moffitt Cancer Center, a comprehensive cancer research center recognized by the National Cancer Institute.

In this story, learn key tips on how people can make a difference for themselves and their health, and regarding what can help save lives, specifically for his specialty: multiple myeloma, an illness that disproportionately impacts people in his own communities, including Black/African-Americans.

In fact, despite how busy Dr. Blue is as someone who does research and helps countless patients, he decided to join a group of patients, advocates, and other myeloma stakeholders for more than two years to collaborate on how to improve the care of underserved groups like Black/African-American multiple myeloma patients and their families. They put together a report that was selected for presentation at the largest gathering of top doctors and researchers in blood cancer called the American Society of Hematology (ASH) annual meeting, a presentation led by a patient advocate named Oya Gilbert.

Watch this second episode of our series to hear about their top solutions on how to serve as many people as possible dealing with the hardships of a cancer diagnosis.

Thank you to Pfizer for supporting our patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

Whatever I do in life, it’s going to involve helping people.

My Path to Medicine

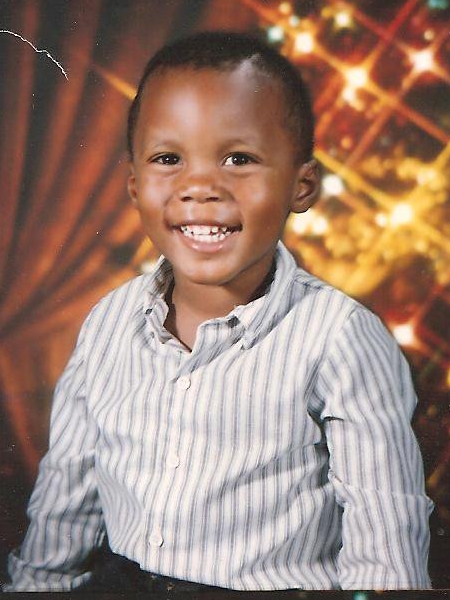

When I was a kid, I was always good at math and science. My mom always told me that if you get good grades, good things will happen. When I was a senior in high school, I wanted a senior ring, but we didn’t have the money for it. So my mom said, “Get a job, and then you can pay for it.” Right across the street from my house was a nursing home that had this big “Help Wanted” sign.

I went over there and asked if I could do any work for them. And they hired me right then and there. I realized I didn’t know what it meant to work in a nursing home. But it was fantastic for me because I got a chance to see people who needed a lot of help, and I realized, hey, I can help them. I worked in the kitchen, and my job was to deliver the food to the patients, so I didn’t help them medically, but I do think that I helped them in a way because I was very inquisitive.

So I’d always get in trouble for leaving the kitchen and going to talk to people. And I felt like I was drawn to people, and it was my chance to be able to talk to them. And that was my first glimpse of my mission. Whatever I do in life, it’s going to involve helping people.

In the nursing home, the holidays were a big deal. Unfortunately, families couldn’t come to visit many of the patients. I remember a lady with a terminal illness or condition. She didn’t have too long left to live, and her family wasn’t there during the holidays. So I knew that time spent with her meant the world to her because, sadly, that was probably her last Christmas. And so I decided I was going to sit with her for a little while. It was fantastic for her to spend time with someone again, especially during the holidays. That was something that I’ll never forget.

So, as a teenager, I decided that I wanted to help people, and I knew I was good at math and science. I thought, “Well, how can I put these together?” So, after high school, people started asking, “What are you going to do next?” And I thought, “Oh my gosh, they want me to have my life figured out at such an early age.” And so I responded, “I think a way that I can use my math and science skills to help people is to become a doctor.”

I knew nothing about being a doctor. But I had seen the doctors who were helping the people at the nursing home, and so that was how I first thought that I could do it, too. I didn’t know what it took, but at least that was my idea of what I wanted to do, even though I didn’t know what that path looked like.

I didn’t have any family members who were doctors. I didn’t have any guidance.

I saw my first Black/African-American doctor when I was in medical school. He was one of my teachers. For me, that was my first I-can-actually-do-this moment. It went from an abstract thought that I didn’t know how to actualize, to — this guy came from where I came from, and he talks like me, looks like me, and he’s making it. So maybe I can make it too.

I want to inspire people to say, “Hey, you go to school, you get good grades, and you can become a doctor.”

The Power of Realizing My Dreams

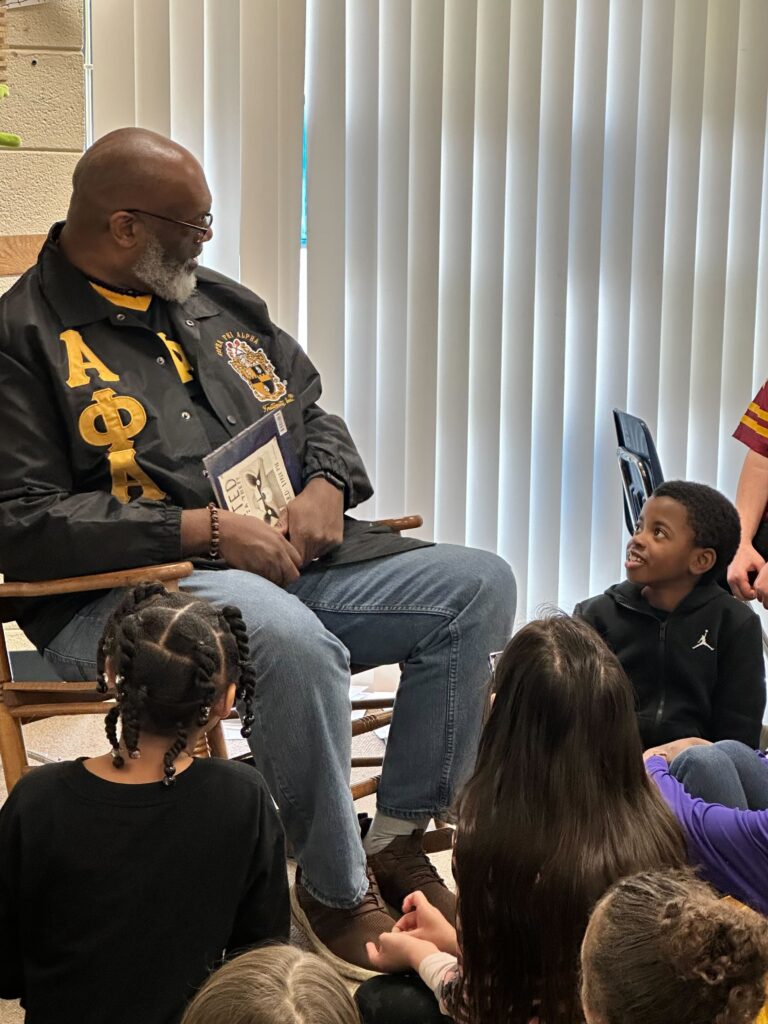

As much as I’m the first in my family to be a doctor, I want to make sure that I’m not the last. We have to make sure that we’re always giving back. And so a big thing for me is to make sure that other Dr. Brandon Blues are following behind me. If, when I was young, someone had been able to guide me and say, “This is the road, this is the path, this is how you do it,” then I might have avoided some of the pitfalls of youth. So that’s one of my main goals: to give back and help people.

I played a lot of basketball and football. For a lot of folks in my community, that was their way of making money. That’s what everyone thought. You play these sports, you excel at them, and that’s how you’re going to be successful in life. I want to inspire people to say, “Hey, you go to school, you get good grades, and you can become a doctor.” And that’s one of the aspirations that I want little kids to develop, instead of just football or basketball aspirations.

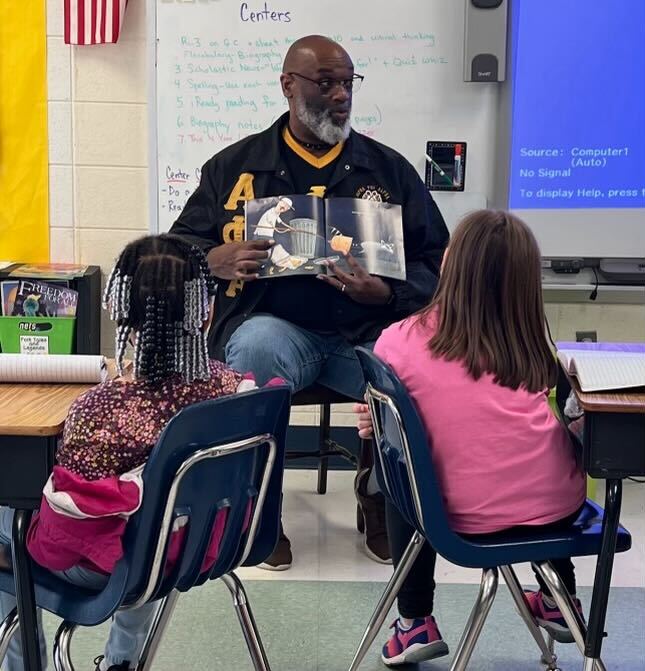

I connect with people in three places. The first is the community center. Kids go there after school to play basketball and do homework. I tell them, “I know you’re only in middle or high school, but let me tell you what the next ten years could look like if you take your math and science classes seriously.”

The second place is the barbershop. In the Black/African-American community, we trust our barbers. Plenty of conversations that happen there don’t happen anywhere else. I want to make sure that health care is discussed there, too. The third place is the church. That’s a cornerstone for minority communities. I want to make sure that, as much as people trust their faith leaders, they can also trust their doctors. I want to let people know that we only want to help.

People say, “I want a doctor who looks like me.” I have patients who drive from all over the country to see me. Unfortunately, there are not enough minority doctors. I do hope that that changes ten or 20 years from now. I know that the connections that I’ve made with my patients are priceless. And so I just want to make sure that I do the best thing for them and that people know that you can come from my community and still be successful.

The rate of having multiple myeloma is about twice as common in the Black/African-American community.

What is Multiple Myeloma?

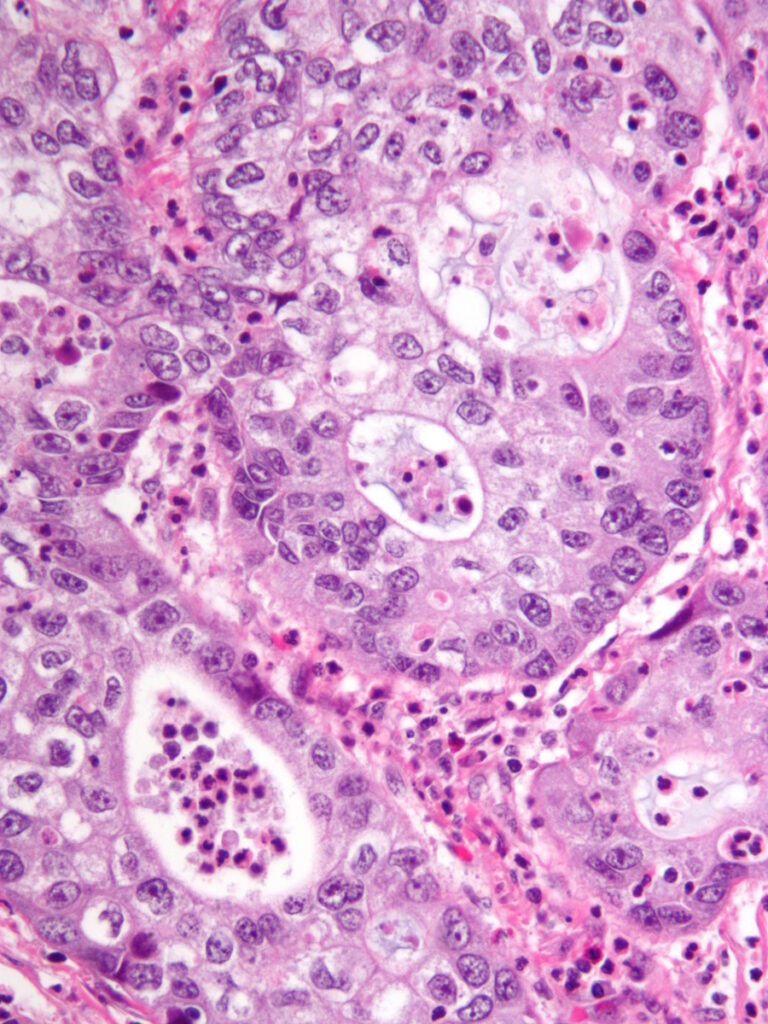

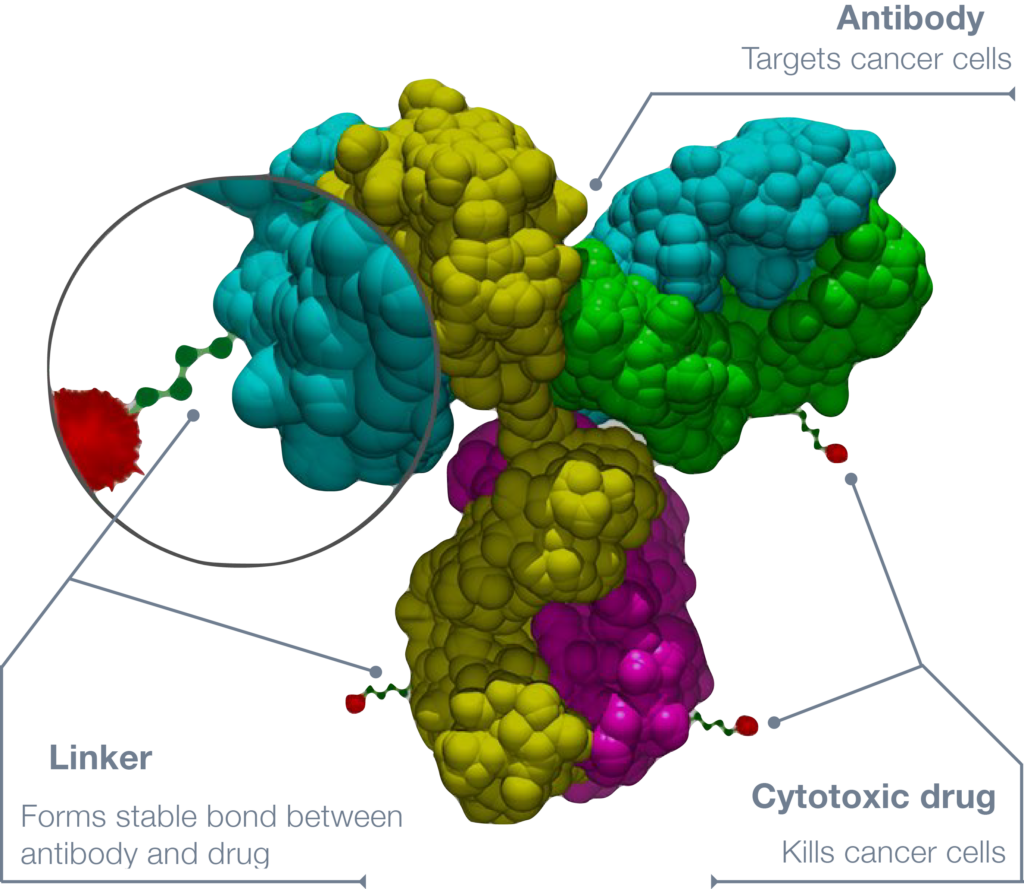

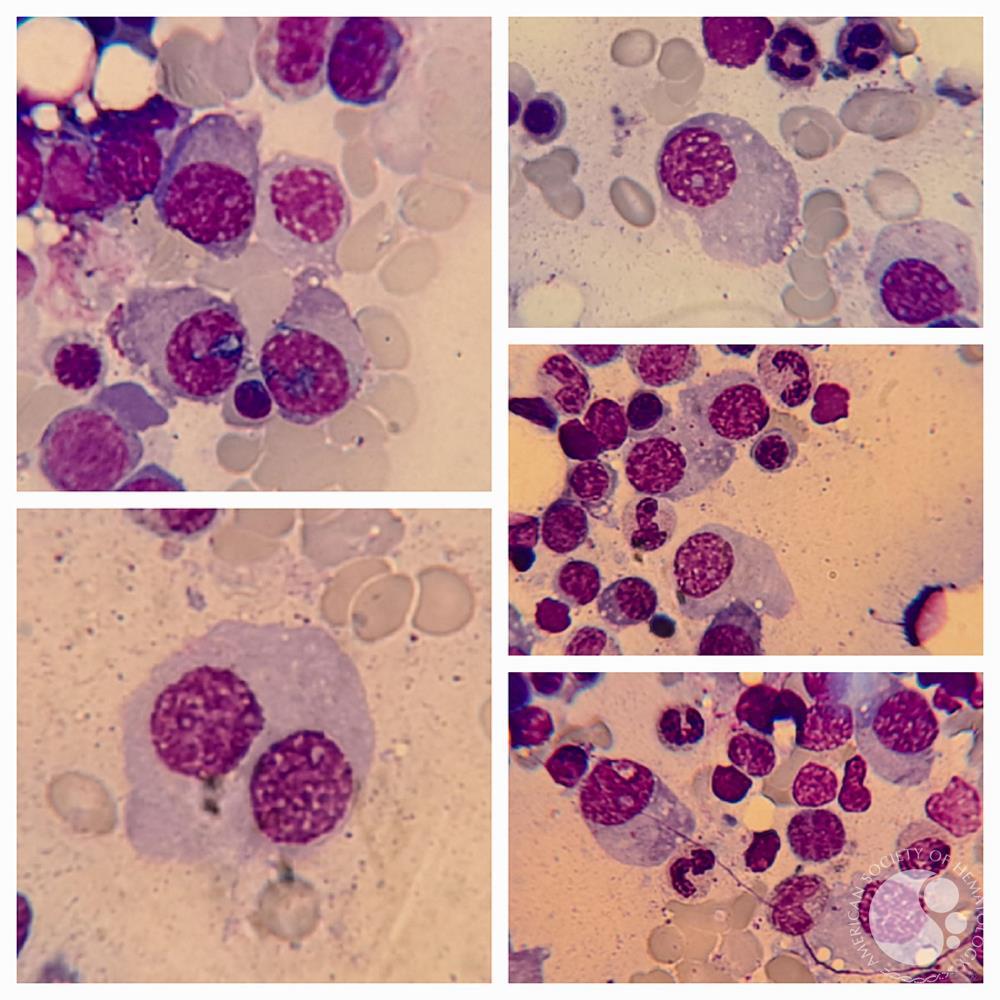

Multiple myeloma is a cancer that unfortunately needs heavy treatment, like chemotherapy, to help people get better. However, it’s not a curable disease, so it’s more of a lifelong illness.

Typically in medical textbooks, the average age of diagnosis for multiple myeloma is 69. For Hispanics, it’s 62. For Black/African-Americans, it’s 64. Why does that matter? Because when you go to the doctor complaining about certain symptoms, they’re looking for someone who is nearly 70 and you’re in your early 60s, they’ll say, “Oh, you couldn’t have that.” Unfortunately for the minority community, multiple myeloma is one of those things that we get at a younger age. Also, the rate of having multiple myeloma is about twice as common in the Black/African-American community.

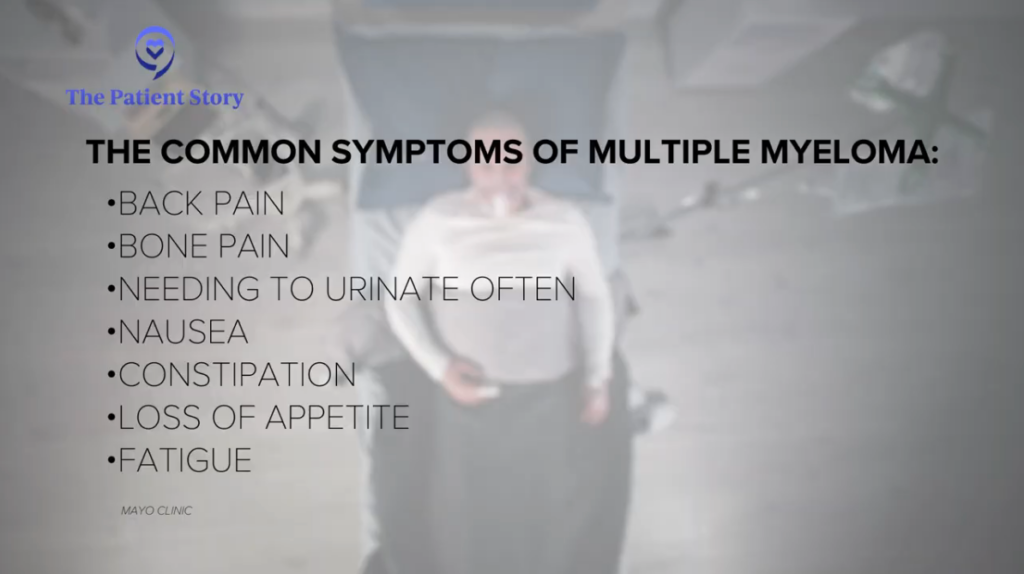

Common Symptoms of Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma is a blood and bone marrow disorder. Unfortunately, it’s not something that you can touch. With other cancers, there might be a lump or something that you can see, like blood in the stool. But because this deals with the blood and bone marrow, it happens on the inside.

The main symptoms that people will feel would be sudden things like back pain because as that marrow fills up with cancer, bones sometimes fracture and break. Another thing that can happen is it can overload the kidneys, so the kidneys shut down or there may be changes in the urine. But a lot of times, that happens when the cancer is very advanced.

We have all the greatest minds from around the world sitting down together and trying to figure out how to cure cancer and make things better for people.

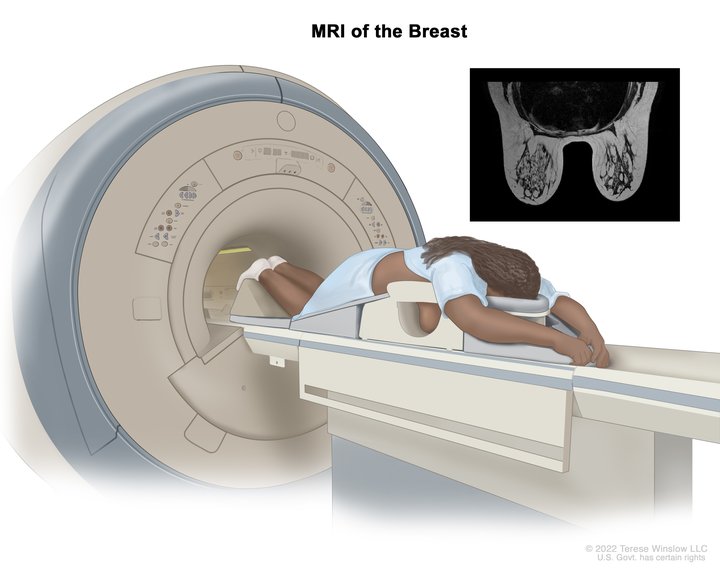

Screening for Multiple Myeloma

Early detection saves your life down the road. If we can detect multiple myeloma before the symptoms kick in, then we prevent lifelong worry and hurt. How can people do that? How can they screen for multiple myeloma?

There is an important research study that I would love everyone to participate in. The PROMISE study is meant for early detection of multiple myeloma and its precursor called MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance). If you are 30 years old, live in the United States, and are Black/African-American, or have a family member with either multiple myeloma or MGUS, then you can get tested for free.

The big thing about cancer care and health care in general is that we want to be doing something better next year, or in ten years, than how we’re doing now. The only way that that happens is through research — knowing what everybody else around the world is doing and putting our minds together and saying, if that’s working, let’s take that forward.

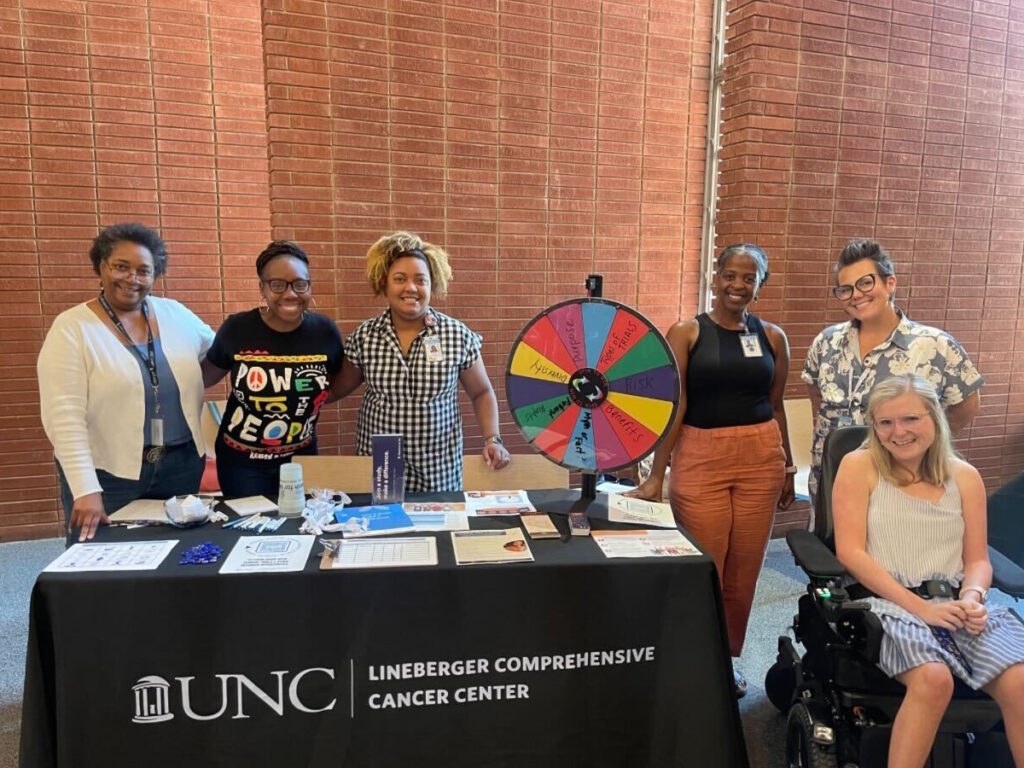

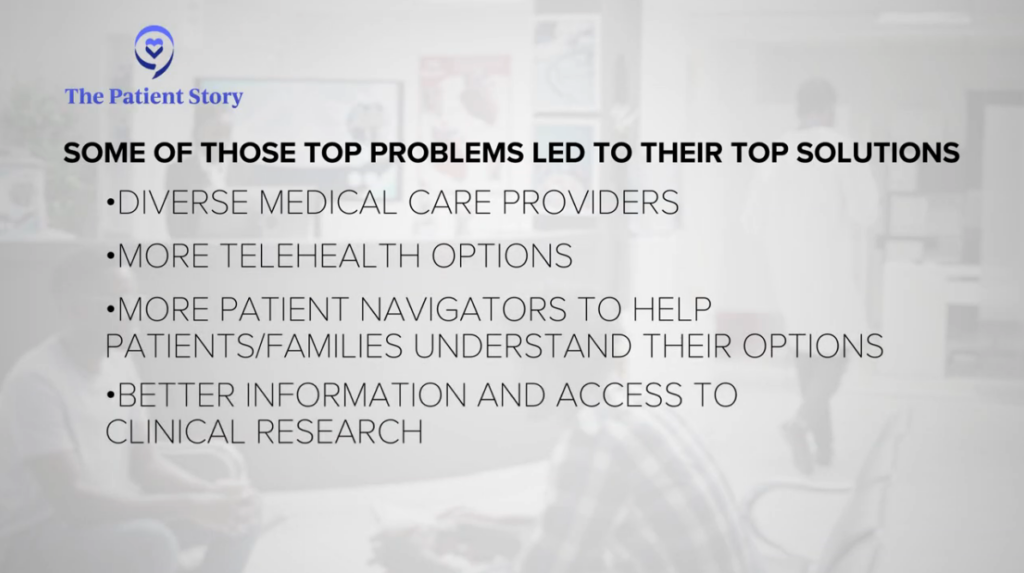

Turning Conversation Into Action: A Collaborative Approach to Health Equity Solutions

That’s what I would say is happening here. We have all the greatest minds from around the world sitting down together and trying to figure out how to cure cancer and make things better for people. And that’s something I’m happy to be involved in. They might say, for example, African Americans have a higher rate of getting cancer (myeloma) or they might get diagnosed at an earlier age (64 versus 69). This is exactly why this research is a little bit different from anything else because we talked about the problems and we also talked about actionable steps to make things better for people starting on day one.

There were so many different people at the table, each person with their role in making things better. We can’t put this all on just the doctors or just the patients and say, well, if the doctors or the patients did this, then things would be better. It took a whole village. I think that’s the real key to the solution. I think that everyone was trying to do things their own way — the different groups each had a plan, but they weren’t all talking. So this is how we put everybody together to work together and make it better. It’s an awesome collaboration.

Years ago, cancer was a death sentence. Thanks to all the innovations, that is no longer true.

My Recommendations for Patients and Care Partners

If I had to choose one actionable step, it would be for people to get second opinions. Patients didn’t know that once they get diagnosed with cancer, they can come to an expert like myself and see if what their doctor is doing is the right thing. That’s important because there can be so many quick advancements in medicine. If your doctor is still doing things from last year or from two years ago, you might not be getting the best care. So it would be a game changer if everyone got a second opinion.

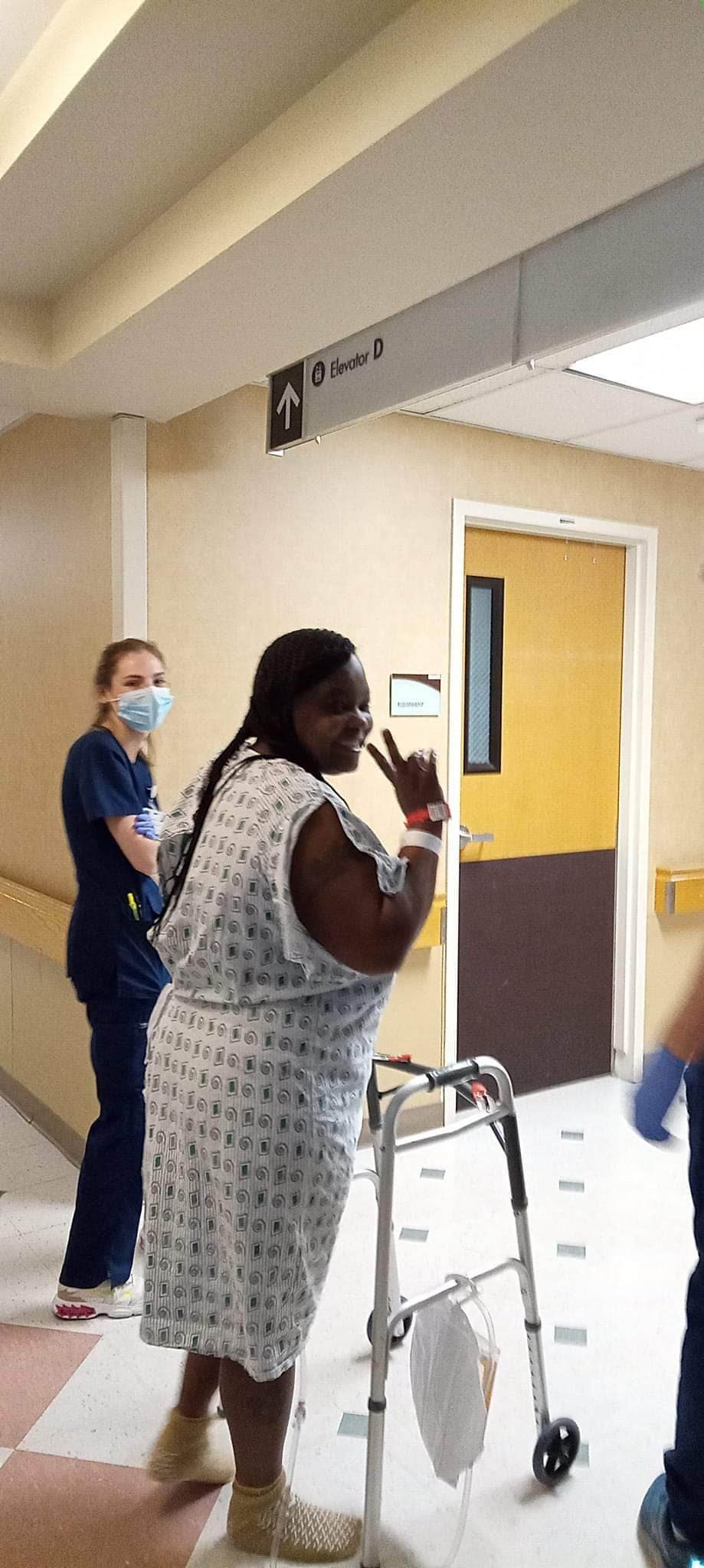

One of the important things for me is not letting cancer define people’s lives. Yes, you are a person with cancer, but you’re much more than that. I have a patient who wanted to make sure that she saw her daughter graduate from high school. One of the biggest advances that we’ve had for the cancer of multiple myeloma is called CAR T-cell therapy. Not only was that lady able to see her daughter finish high school, but she’s also now about to see her daughter graduate from college. She might not have been able to do so without some of these advancements that we’re talking about at these conferences.

Years ago, cancer was a death sentence. Thanks to all the innovations, that is no longer true. As a doctor, I try to make sure that these innovations are available to my patients and that I’m doing the right thing.

I remember a patient with severe cancer who wasn’t highly educated and didn’t understand how severe his cancer was because it wasn’t something he could touch, but he just knew that he felt bad. We tried so many different types of treatment, but unfortunately, his cancer was just too advanced. To this day, that’s something that just eats at me, if we had gotten him earlier and treated him earlier, maybe he would still be here today.

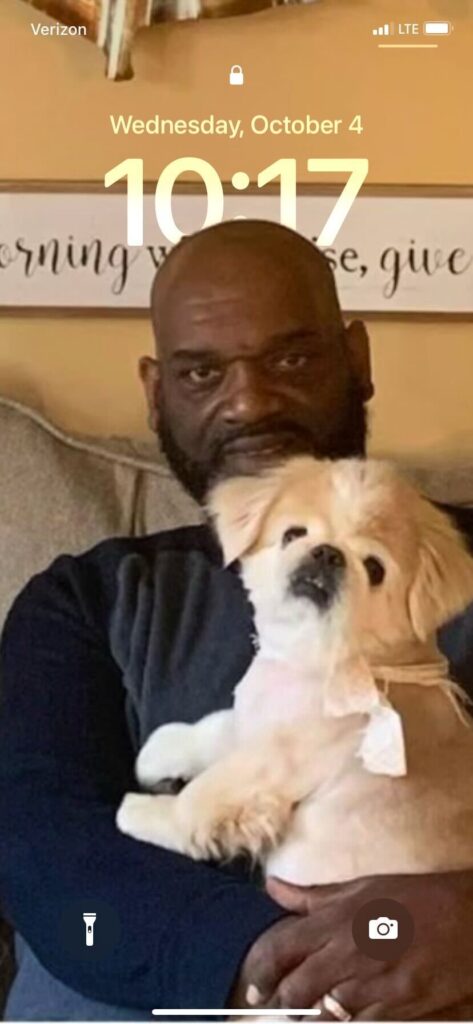

My father had a blood disorder known as diffuse large B cell lymphoma, which is a cancer that affects the lymph nodes. I’m happy to say that after two years, he’s in complete remission. He has a special IV called a port, and he gets to take his port out. Of course, he’s very happy about that. I’m happy to be involved in it because I am a cancer doctor who specializes in blood cancer. I can be a part of his journey, not only from a doctor’s side but as a son. I can educate people and say, “I know what it’s like to be a caregiver. I know what it’s like to have a family member with this cancer, and I never wish that upon anyone.” But if you do have it, just know that I’ve been able to walk a mile in your shoes.

Special thanks again to Pfizer for supporting our patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content

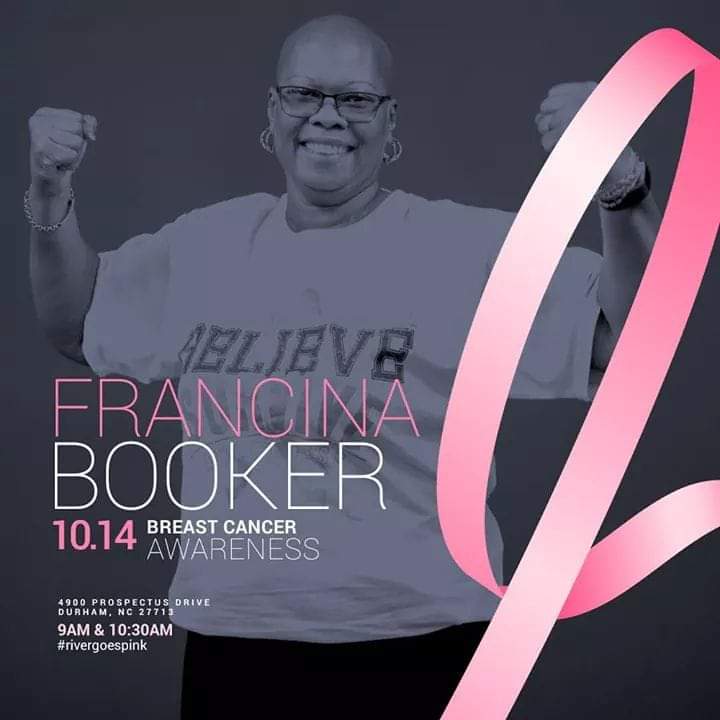

Hip-Hop, Hope, and Health: Oya Gilbert’s Multiple Myeloma Story

Oya Gilbert had always been full of energy. A father, a hip-hop lover, and a man who rarely got sick. But in 2015, his body started sending him signals he couldn’t ignore. But for two years, doctors dismissed his symptoms as anxiety. Watch Oya’s story from misdiagnosis to myeloma advocacy.

1st Line Treatment Stories

Michelle C., Multiple Myeloma

Symptoms: Back pain, sinus infections, painful and itchy scabs, stomach pains, weight loss

Treatments: First-line treatment, stem cell therapy

Melissa V., Multiple Myeloma, Stage 3

Symptom: Frequent infections

Treatments: IVF treatment & chemotherapy (RVD) for 7 rounds

Jude A., Multiple Myeloma, Stage 3

Symptoms: Pain in back, hips and ribs; difficulty walking

Treatments: Bilateral femoral osteotomy, reversal due to infection; chemotherapy

Relapsed/refractory treatment

Dr. Yvonne D., Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma

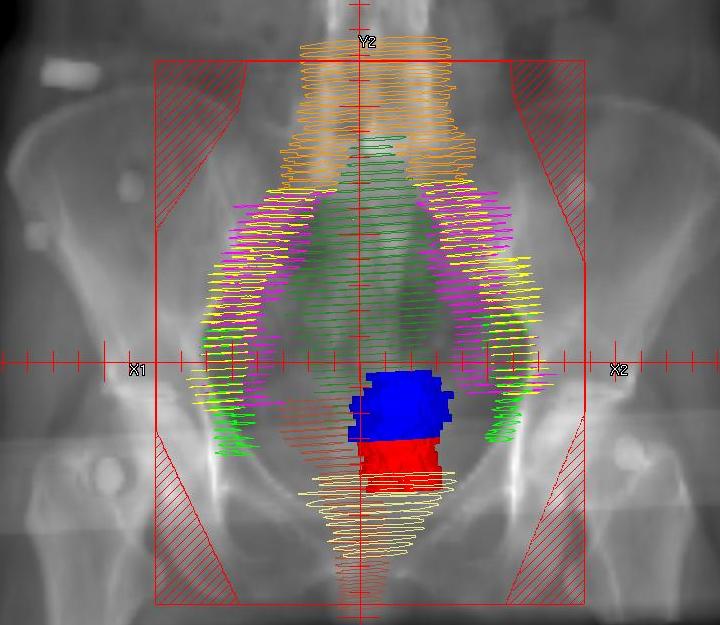

Symptoms: Severe hip pain, trouble walking due to a broken pelvis, extreme fatigue, bone pains

Treatments: Chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, radiation therapy, surgeries, CAR T-cell therapy

Michele J., Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma

Symptoms: Fatigue, anemia, persistent lower back pain, sharp leg pain during movement

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy, stem cell transplant

Theresa T., Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma, IgG kappa Light Chain

Symptom: Extreme pain in right hip

Treatments: Chemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapy, stem cell transplant, radiation

Laura E., Multiple Myeloma, IgG kappa

Symptom: Increasing back pain

Treatments: Chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, bispecific antibodies

Donna K., Refractory Multiple Myeloma

Symptom: None; found through blood tests

Treatments: Total Therapy Four, carfilzomib + pomalidomide, daratumumab + lenalidomide, CAR T-cell therapy, selinexor-carfilzomib