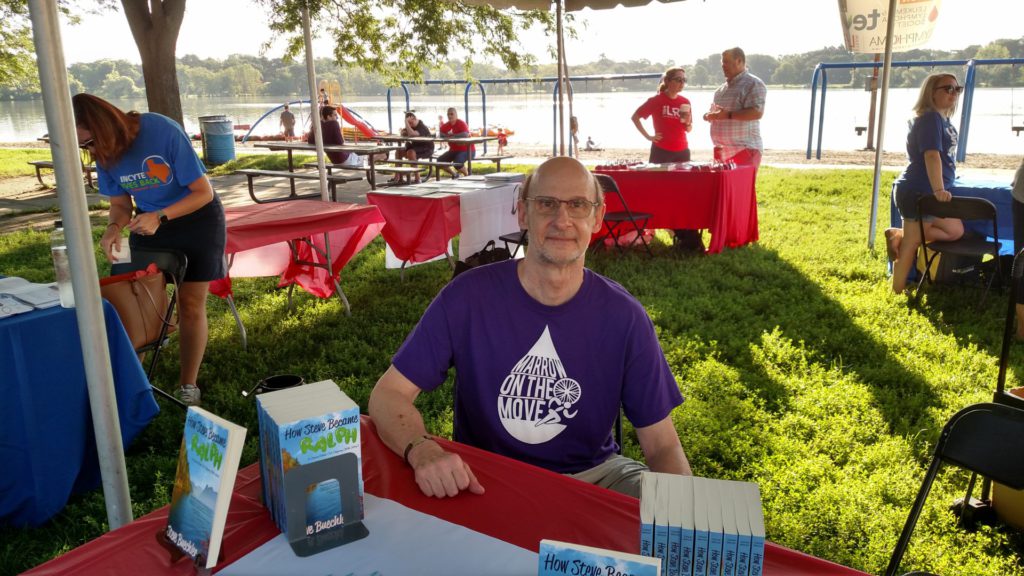

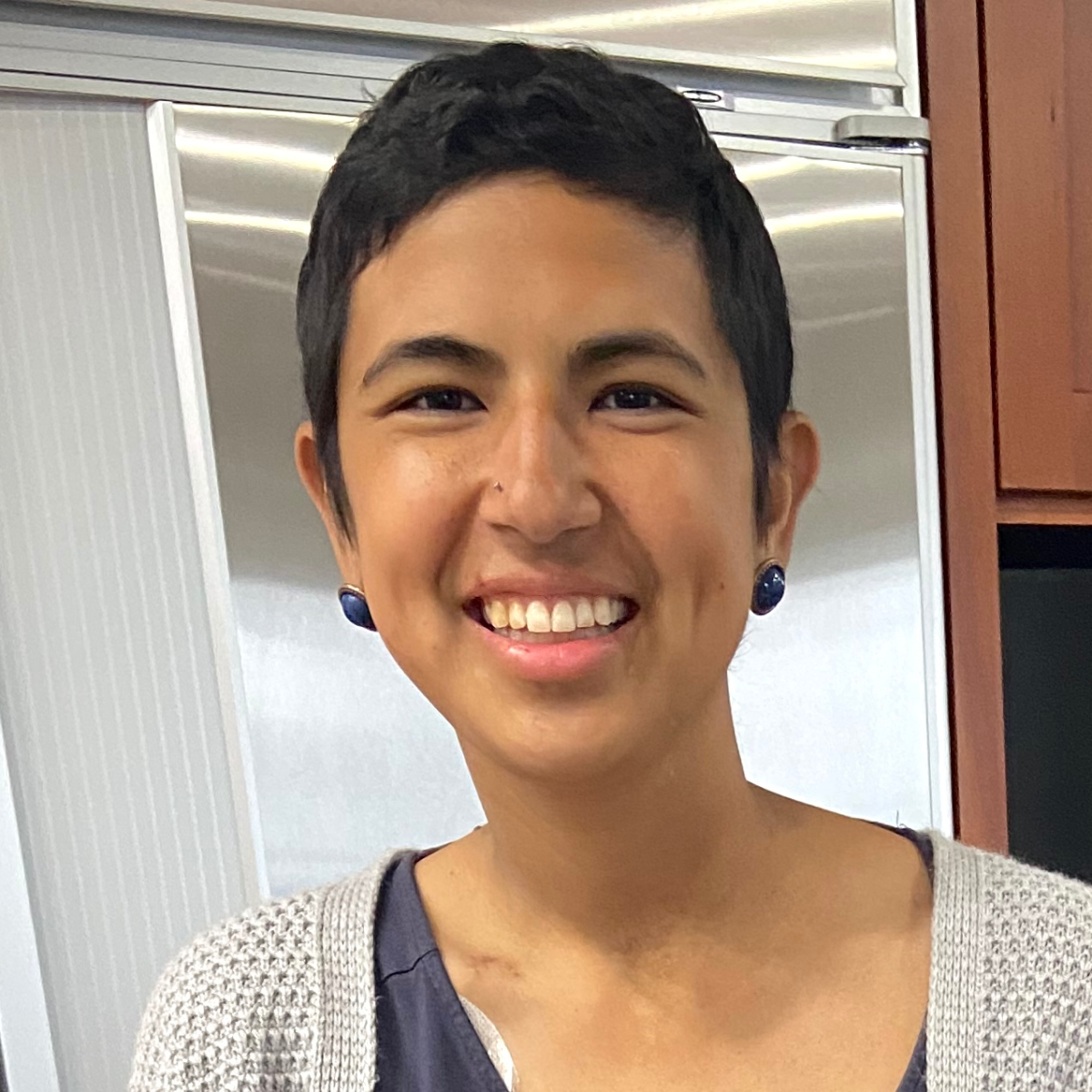

Laura’s Stage 4 Kidney Cancer Story

Interviewed by: Alexis Moberger

Edited by: Chris Sanchez

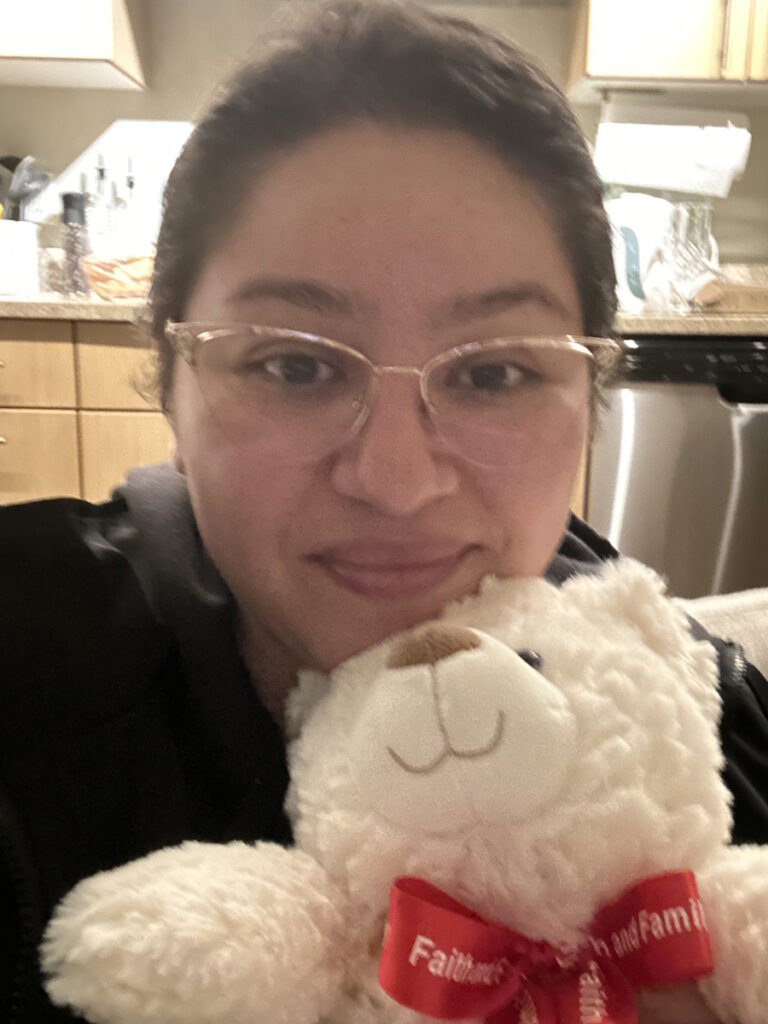

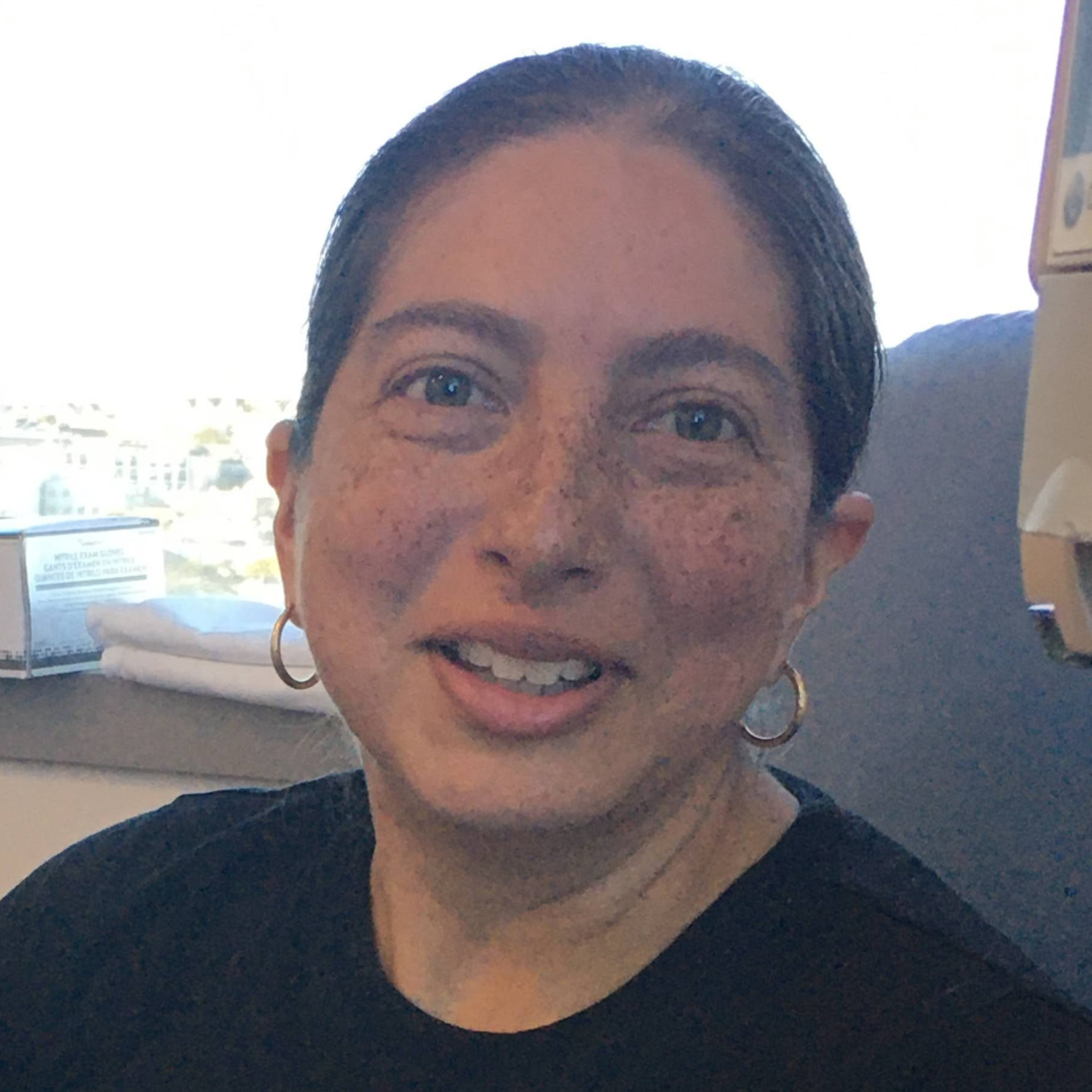

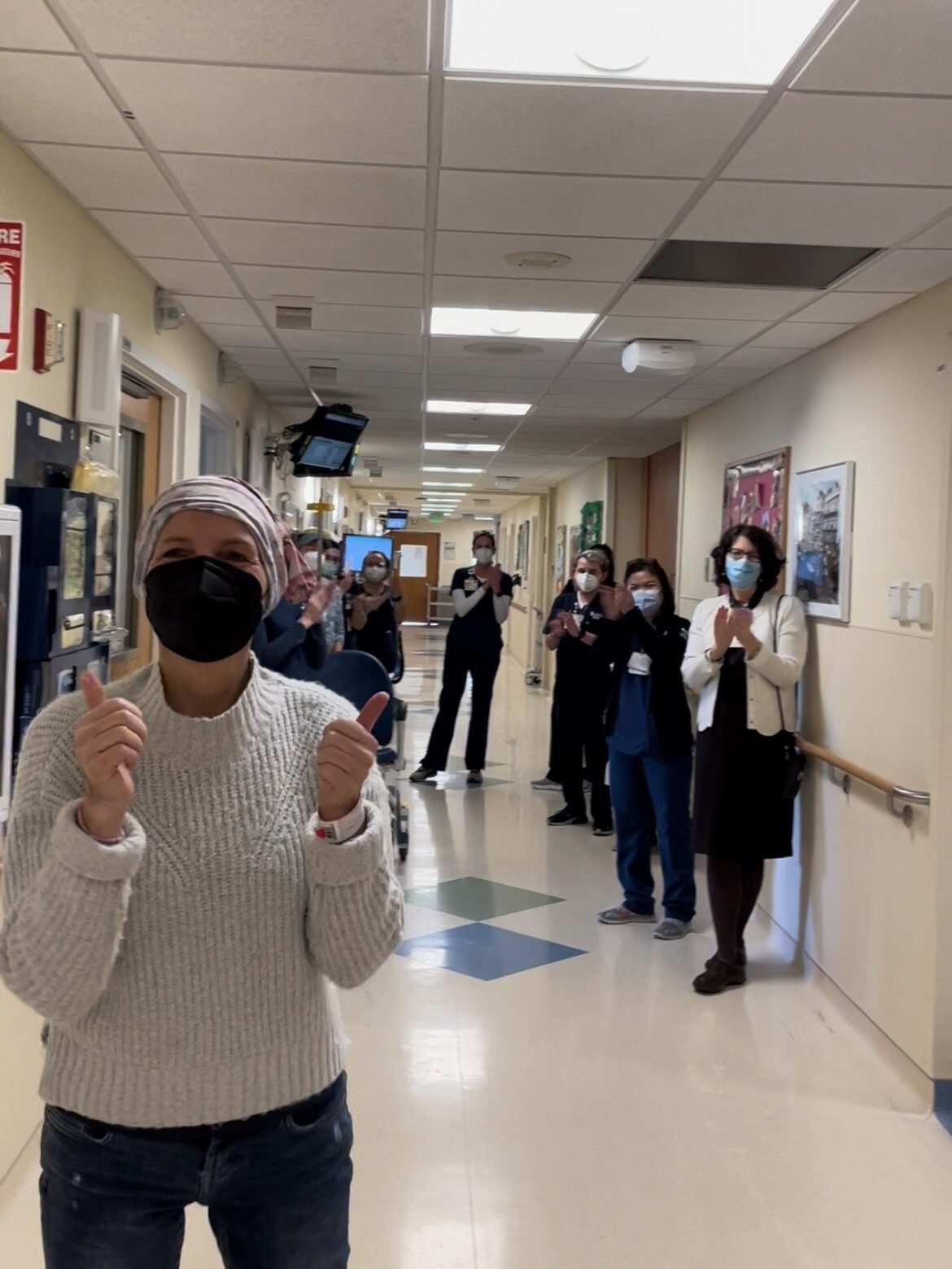

Laura survived stage 4 kidney cancer.

Originally from south Louisiana, Laura now lives in Southern California. She splits her time between working full time in marketing in the gaming and hospitality industry, being a kidney cancer patient advocate, enjoying her sports and hobbies, and caring for her family.

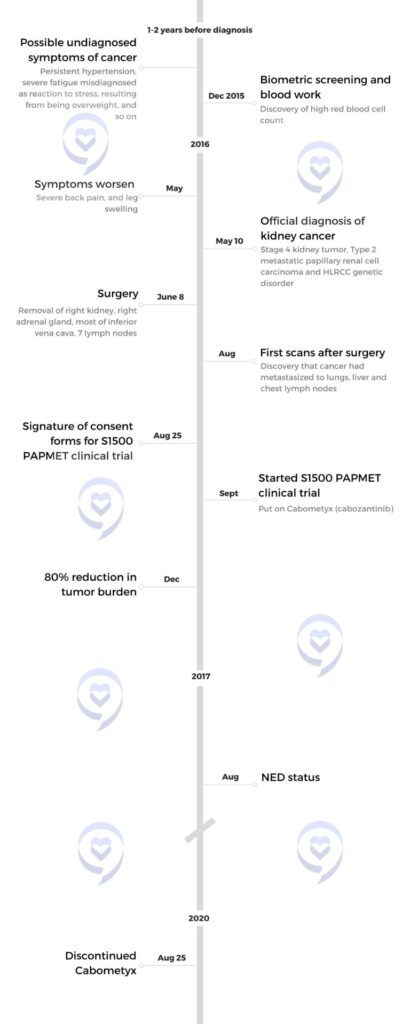

Laura had been struggling with her health for at least two years before her symptoms were properly diagnosed as cancer. She suffered from elevated blood pressure and fatigue so significant that she would sometimes have to nap in her car during lunch breaks, and was also found to have a very high red blood cell count. But the doctors she would consult chalked her symptoms up to lack of sleep, stress due to her demanding job, excess weight, and so on.

Later on, Laura’s health took a turn for the worse. She started to experience back pain so bad that she sometimes had a hard time walking, and her legs became so swollen that she was unable to wear pants to a dinner out to celebrate her 29th birthday. She returned to the doctors, who started taking a closer look at her symptoms and ordered more procedures.

Blood work uncovered kidney issues. Her doctor told her to have a CT scan done that week, but she decided to take immediate action. That very night, just 5 days after her 29th birthday, she went to the emergency room. It was a pivotal and timely decision: the doctors discovered that she had stage 4 cancer and a massive 13cm tumor on her right kidney. The doctors also found that this tumor was what was causing her legs to swell, because it was blocking her vena cava–the main artery bringing blood back up to the heart from the lower parts of the body–making immediate treatment even more urgent. Laura was also diagnosed with the rare genetic disorder, hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC), or Reed’s Syndrome.

Laura’s ER surgeon, a kidney cancer survivor himself, connected her with the UCLA-based surgeon who had operated on him years ago, and she ended up heading there for surgery. During a 5-hour session, the surgical team removed her right kidney, right adrenal gland, most of her inferior vena cava, and 7 lymph nodes. However, a checkup some weeks later revealed that the cancer was not only still present but had also spread to her lungs, liver, and nearly all the lymph nodes in her chest.

Laura started seeing another doctor in Las Vegas, who recommended that she take part in the S1500 PAPMET randomized clinical trial organized by the global cancer research community, SWOG Cancer Research Network. After some deliberation, she decided to join the trial, where she ended up taking the targeted therapy drug Cabometyx (cabozantinib).

The side effects of cabozantinib were crippling. But just a year after Laura started taking it, she was found to be in complete remission. Out of 147 patients who joined the trial, she was 1 of only 2 who had had a complete response to their treatment.

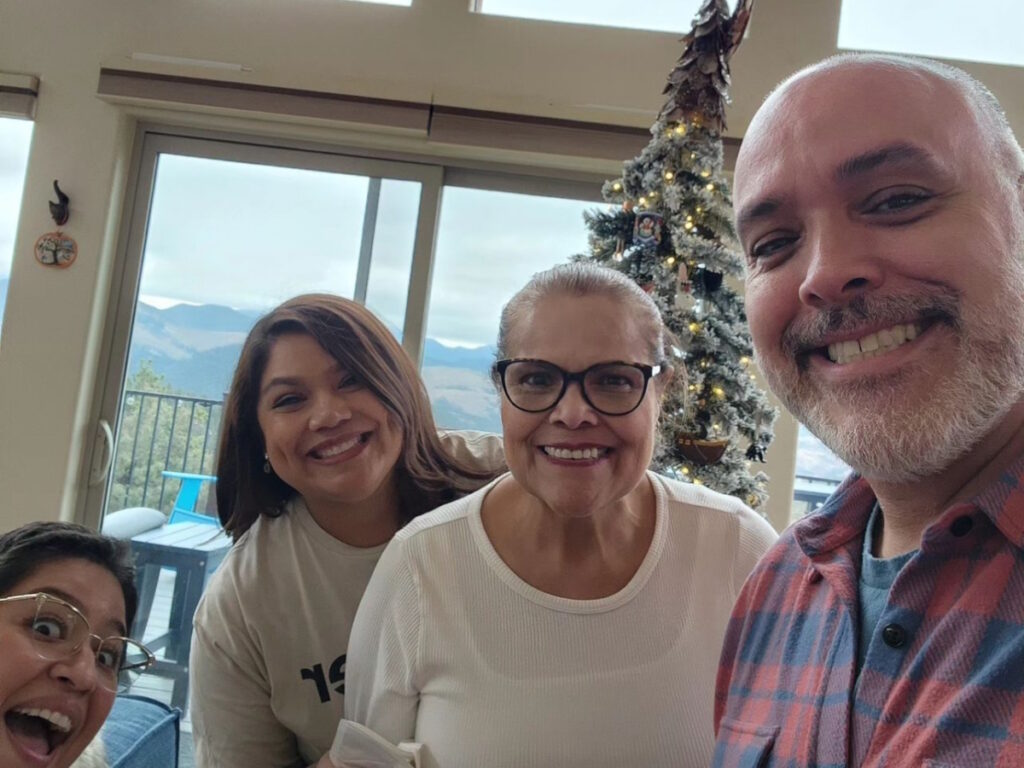

Laura continues to be healthy to this day; she undergoes scans every six months, and to date her status continues to be “NED” (no visible evidence of disease). But not only is she enjoying her life once again, she is also now a patient advocate, and actually works with the very doctors who concluded the clinical trial she joined.

Laura is sharing her story with us to show that a Stage 4 diagnosis does not have to be a reason to give up hope; to exhort cancer patients to advocate for themselves as a lifelong responsibility; and to urge them to get to know both their bodies and their disease, in order to be able to make the best possible choices for themselves.

In addition to Laura’s narrative, The Patient Story offers a diverse collection of stories about kidney cancer. These empowering stories provide real-life experiences, valuable insights, and perspectives on symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options for cancer.

- Name: Laura E.

- Diagnosis:

- Genetic condition: hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) (Reed’s Syndrome)

- Type 2 metastatic papillary renal cell carcinoma

- Staging:

- Stage 4

- Symptoms:

- Profound fatigue

- Hypertension

- High red blood cell count

- Severe back pain

- Badly swollen legs

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy: Cabometyx (cabozantinib) assigned under S1500 PAPMET clinical trial

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

I’m not the same person I was before I was diagnosed. There’s no way I could be.

I definitely look at life differently now…

I try my best to live as authentically as possible. Because I know time is a gift.

Introduction

I am 36 years old. I live in Southern California, and I’m originally from outside of Baton Rouge, in the south of Louisiana.

I’m a proud graduate of Louisiana State University, where I got a bachelors and masters from National University. I’ve been working in marketing in the gaming and hospitality industry for over a decade now. Just busy with my family when I’m not at work.

I also like to read and do Zumba and watch global reality TV. I’m actually am part of an all women’s Mardi Gras krewe; I ride in a parade in New Orleans every year and it’s one of my favorite things to do. I just rode earlier this year and I’m already ready for next year.

Pre-Diagnosis

I was having symptoms of my kidney cancer probably two years before I was officially diagnosed.

I had horrible fatigue and was actually going to my car in my lunch breaks to sleep. My blood work was really off. I would go get my blood work done and there would be this one level that I was like, why is it off? And actually had a doctor tell me, oh, if something was really wrong, it would be like hundreds off the charts.

My blood pressure was high, too. I talked to my primary care doctor and she said, well, hypertension runs in your family. And I said, I know, but I’m in my 20s. It’s usually people in their 40s and 50s in my family that have hypertension.

Everyone just kept telling me, lose weight, get more sleep, reduce your stress. And at the time I was working in marketing for a casino corporation that has multiple properties across the country. I was the marketing manager over three of their properties on the strip. And so I thought, okay, well, I probably am stressed.

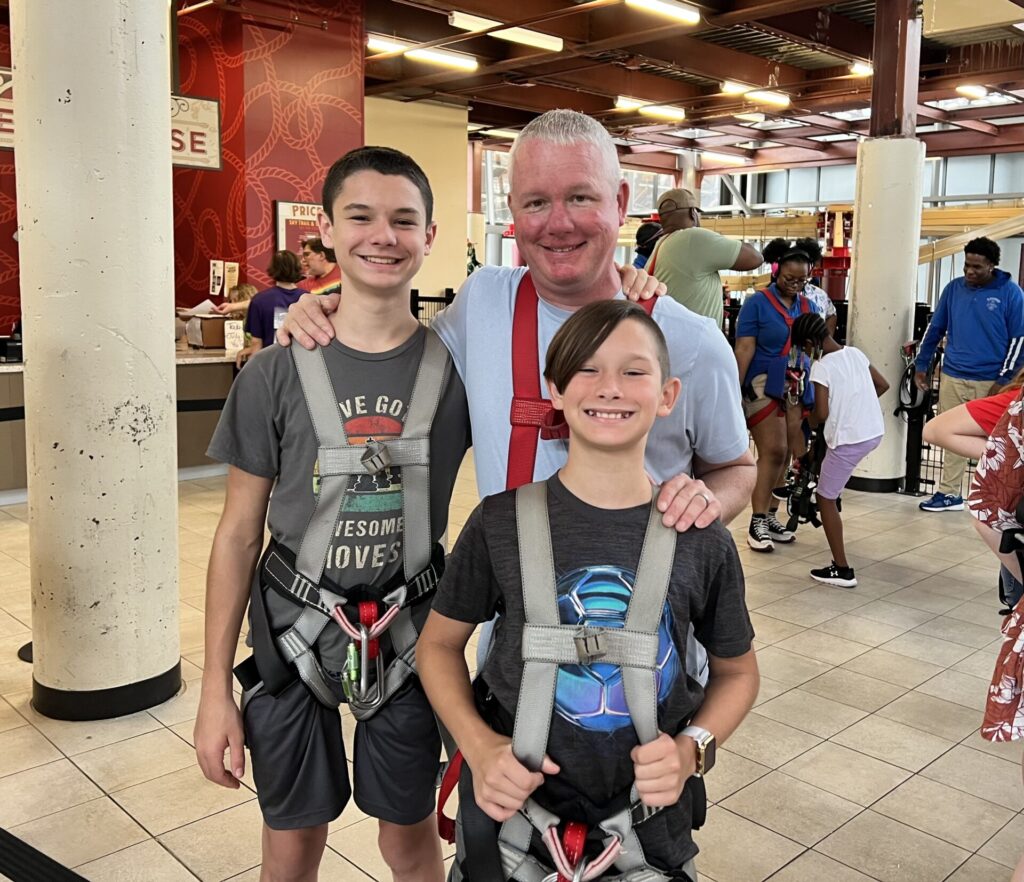

You know, I was working a lot of hours and, and had a lot of responsibilities. My kids were in middle school at the time or late elementary school. And so I just thought that’s kind of how things were. And then it was about six months before my diagnosis.

Diagnosis: Type 2 metastatic papillary renal cell carcinoma

I went to get another biometric screening done, and they almost called an ambulance because my blood pressure was so high.

So I went to my primary care doctor. But she again said, lose weight, reduce your stress. I ran my blood work and my red blood cell count came back really high, which I later found out is an indicator of kidney cancer. But the doctor said, oh, you probably just had an infection or something.

I felt like a hypochondriac at that point. These are all specialists. These are all doctors. They know what they’re doing, who am I to question it? So that was December.

And then one day in May, ten days before my birthday, I woke up and I just had the most horrific back pain I’ve ever had in my life.

I was honestly struggling to walk. It felt like I was a puppet and someone was just pulling the strings, you know?

And so I went to urgent care because my primary care couldn’t get me in. But it was more of the same. They said, yeah, you probably pulled a muscle here. I was given some muscle relaxers. Of course, they didn’t work.

It progressed to the point that a few days later, for my birthday, we went out to dinner and I couldn’t even put pants on. I had to wear a dress because my legs were really swollen.

So my mom was in town at the time and I didn’t want to freak her out, so I waited until she left town a few days later to go to my primary care. And when I went there, the doctors did more blood work and said, something’s wrong with your kidneys. I’m going to send you for a CT scan. Go get it done within the week.

But I was really feeling that it couldn’t wait. Thankfully I didn’t listen. I went to the ER that very night after work.

The ER doctor diagnosed me with a 13 centimeter tumor on my right kidney and told me I needed to have surgery as soon as possible. He told me to go to a specialty hospital, not to just let any surgeon operate on me, which now that I know so much more about my disease than I did at the time, I realized it’s because it was a very complicated surgery they had to do.

And that was five days after my 29th birthday. I know my outcome would have most likely been very dramatically different had I not gone to the ER that night.

I was also diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder, known as hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC), or Reed’s Syndrome.

Reaction to the Diagnosis

It took forever for me to get diagnosed, but once I did, everything lined up into place.

I think I just kind of shut down mentally after the ER doctor said, you have cancer. And I really struggled to process it. I almost felt for a minute there like if I said it out loud, it made it real, you know? I’m a very logical person, but it was hard to process.

I remember we got home from the emergency room, early the next morning because I had been there all night. I had to call my boss. It was a work day; I actually had a presentation that I was supposed to be giving that day. And so I’m thinking, oh my gosh, I have to call my boss and tell him I have cancer. And I actually sat in my chair in my living room and was practicing saying, “I have cancer” before I called him. I was trying to: one, make my experience a reality and, two, keep myself from crying while I’m telling him this. It just felt like a bad dream, honestly. It didn’t even feel real.

And there was about a month between my diagnosis and my surgery, and I was in terrible pain the whole month. You know, I just wanted to sleep and just not think about what was happening. So it took me a while, even after my surgery, to really come to terms with what was happening.

And I remember distinctly after my surgery, I was in ICU for, I think, about five days. And then they moved me to a regular room, and it was there that I finally went, I should probably look at my gown and see my doctors. I hadn’t even done that at that point. I think that was the moment that it really hit me, like, oh my God, my life is never going to be the same again. Like I knew that cognitively. But that was my emotional process. This isn’t just “I have surgery and I’m done with it and I move on with my life.” This is forever going to be something that I am now identifying as a cancer patient and cancer survivor.

It’s frustrating whenever I look back, because I know that at the time of my diagnosis, I had to have had cancer for at least a year, probably two plus. And the idea that had I not been diagnosed at stage four, I could have just had surgery and been done with it, I wouldn’t have reached a point where I’m being diagnosed with a terminal phase of this disease. It’s pretty heartbreaking and it’s really frustrating.

I went back and talked to my primary care doctor a few months after I was diagnosed. Obviously, I’d switched doctors at that point. But I talked to to her and the head of the clinic and I said, look, I know that you will probably never see another case like mine again, but, you know, there’s this phrase with rare cancer patients that they tell doctors at medical school to look for horses when you hear hoofprints, not zebras. And I’m a zebra.

Look, you’re going to go on and treat other patients. And you may never see another case like mine again, statistically speaking, but it doesn’t mean that you don’t have to see other cases that aren’t rare on their own. And I think that we are conditioned a lot of times, especially as women, to just accept diagnoses, if you’re telling me nothing’s wrong, nothing’s wrong, and I’m just going to believe that. But we know our bodies.

I really encourage people to trust their instincts when it comes to their health. You know your body best, you know if something’s wrong with you.

And I really wish I would have just kept listening to that little voice that I had in my head. You know, in my heart that said, Laura, something’s wrong.

I’m glad that I finally did, because that’s what encouraged me to go to the ER that night.

Surgery

The ER doctor told me that he’d already contacted a local urologist in Las Vegas, where I was living at the time, and that the urologist was going to help me get to either USC or UCLA in California for surgery. The ER doctor was very adamant that I needed to go to California for surgery.

I’m now realizing how extensive the tumor was. It’s not just that it’s 13cm, which is very large for a kidney tumor, but it was also blocking my vena cava, which is your main artery that brings your blood back up to your heart from your legs and all. Which is why my legs were so swollen. And so that’s a life threatening condition, which I’m glad I didn’t know at the time because I probably would have just completely shut down at that point.

I realize now that’s why the ER doctor was so insistent that he needed to go to California for surgery. And so the next morning we went to the urologist in Vegas, and he said there was one surgeon in town who may be willing to take your case. Didn’t want that. But he said, if you go to California, I’ll get you in at UCLA.

The doctor added, actually, I was you seven years ago, with kidney cancer. And if you go to UCLA, I will send you to the surgeon who operated on me. And sure enough, he did. He actually walked out of the exam room and called the surgeon on his cell phone and said, I’m sending you a patient from Vegas. And so I got into UCLA.

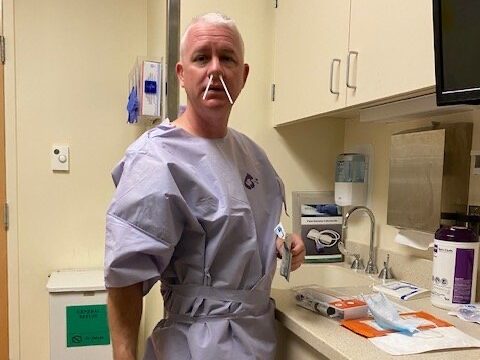

They did a phenomenal job with my surgery. I was incredibly lucky. I had two amazing surgeons and it was a five and half hour surgery, and they removed my right kidney, my right adrenal gland, most of my inferior vena cava, and seven lymph nodes. And we were hopeful that they’d removed all the cancer. And maybe I would need to do immunotherapy afterwards to keep it from coming back. So that was in June.

Cancer metastasized

But when I had my first scans in August, the cancer was spreading like wildfire.

And so at that point, the cancer was in my lungs and my liver and pretty much all the lymph nodes throughout my chest.

And the doctor at UCLA said, I could put you on this one treatment.

Again, I would just go back to if something doesn’t feel right, listen to your body.

I think even as cancer survivors, we tend to dismiss things sometimes, and so even if you’re in your cancer journey or you’re a survivor, you have to.

It’s advocating for yourself as a lifelong responsibility.

Treatment

Treatment Options

The doctor said, I don’t know if it’s going to work for you. I think you probably should look into clinical trials, but if you do that, you’re going to have to come back and forth a lot. And I know that’s going to be kind of a burden for you to do that. So there’s a doctor in Vegas who is a specialist in kidney cancer, and I would recommend you go see her.

And I was really nervous about switching my care back to Vegas because of the experiences I had before, obviously. I actually had debates with my family and friends on whether I was making the right decision to move my care from UCLA? And I said, you know what? I’m going to go ahead and try it.

And I wound up with the most wonderful oncologist, who, again, was a GU, a kidney cancer specialist named Doctor Vogelzang. And at the first appointment, he sat me down and said, look, here’s what you have. He was the first doctor to explain to me what specific type of kidney cancer I had, answered all my questions, said, I have these treatment options lined up for you. There were all clinical trials because at the time there was no standard of care for the type of kidney cancer I had.

And so he said, here’s the one I think is the best option for you. There were three other ones that he had lined up. And then he said, look, I’ll even do chemo if I have to. Chemo isn’t usually used for kidney cancer patients. But I was so young that he just was like, I’ll do whatever I can to try to give you as much time as we can.

So he explained the first trial and he said it’s four different types of treatments. It’s a randomized trial. I can’t promise you which one that you’ll get. We have no control over that. But there is one treatment on this trial that I think would be your best bet. He said, look, think about it. Let me know what you think in your next appointment, what you want to do.

Decision to Join a Clinical Trial

And I decided to join the clinical trial. The clinical trial that I was on was sponsored by a group called SWOG.

Even now people say to me, oh, that was so brave of you to choose a clinical trial. And I recognize now that it was a brave decision to do a clinical trial. And I’m really proud of my decision to do that. But at the time, it just felt like, what choice do I have? I have terrible choices to make. And, if I make the wrong decision, that’s my life in the balance. That’s how it felt.

I also remember having this conversation with a close friend on my next steps. I said, look, the doctor I met with in Vegas is saying he doesn’t think the treatment that UCLA recommended is going to work for me. And let’s be honest, I’m dying anyway.

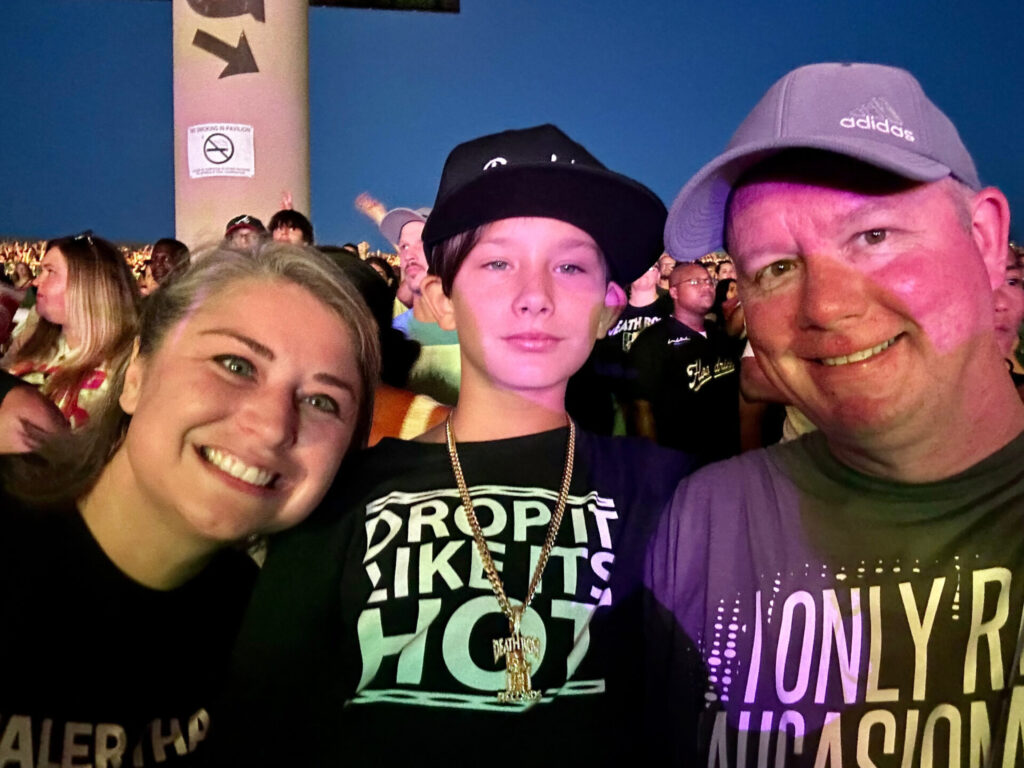

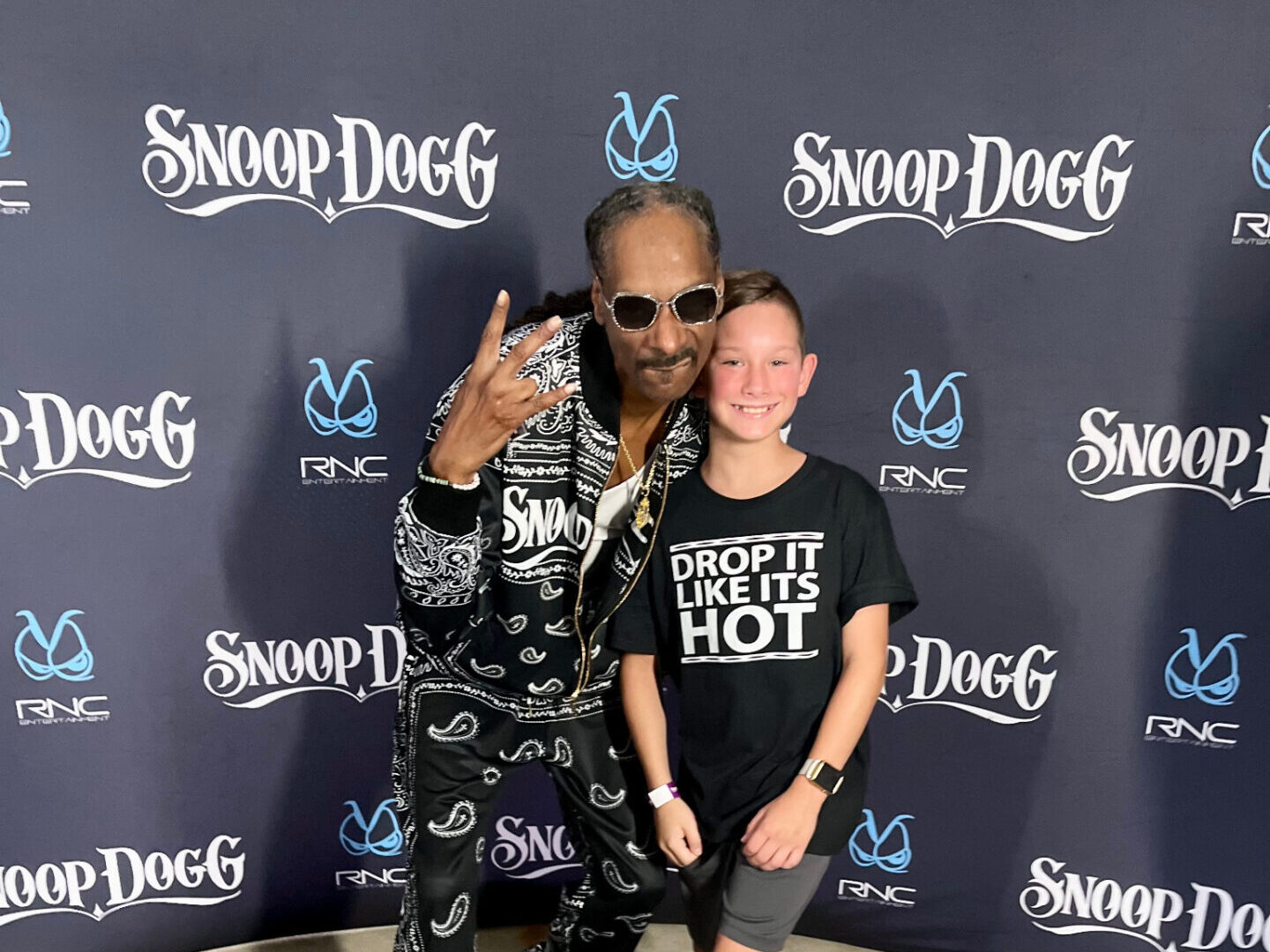

So maybe this is a Hail Mary. Maybe this will help me to live a few years. My goal at the time was to see my kids graduate high school. But if not, at least I’ll be doing something that will help other patients at some point. And so that’s why I decided to do the trial.

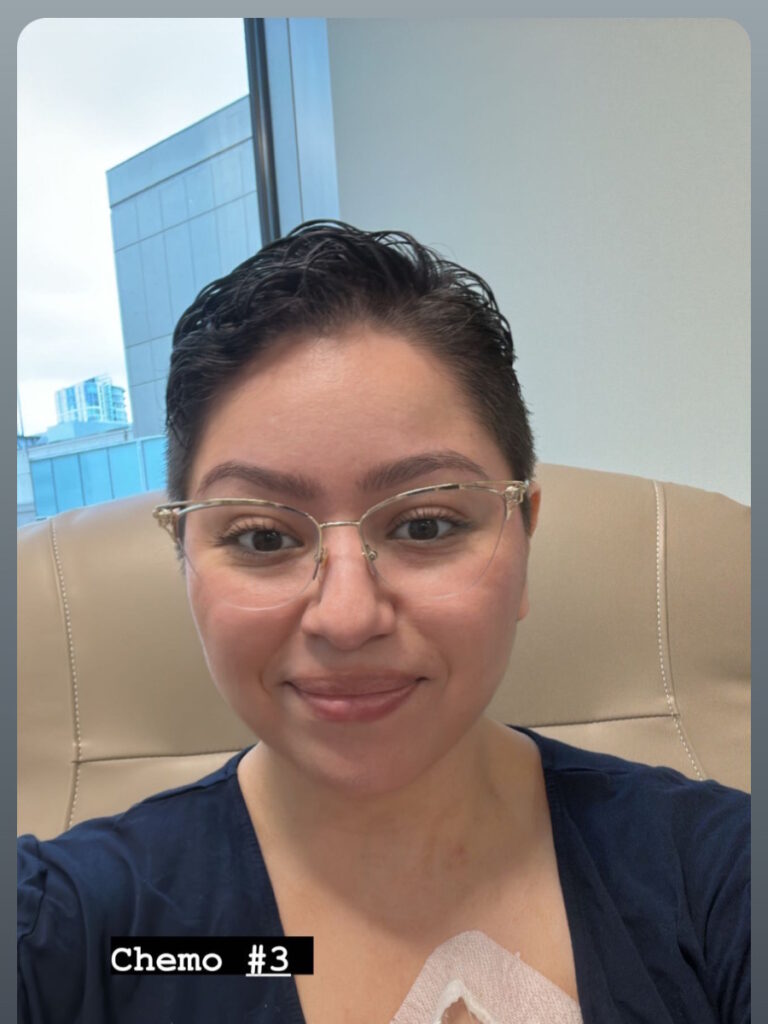

Cabometyx (cabozantinib)

And I remember when they randomized my treatment. My doctor said, oh my gosh, you hit the jackpot. This is the drug I wanted you in. It was a drug called cabozantinib.

And, at the time, I didn’t know what that was. I thought I was going to be doing immunotherapy, which I’m now embarrassed to admit because I know the differences between the drugs now.

And so I’m like, I can’t believe I thought I was doing immunotherapy because I just didn’t know the difference. It was a targeted therapy drug. And I started it and I was just terrified. And of course, my doctor explained the side effects and I’m going like, wait, what’s going to happen to me?

But again, I was like, what choice do I have? I mean, I can’t die now. I knew at that point that I had no more than a year and I would be lucky if I had another year.

And so I actually pulled my kids out of school for my first day of taking my pills. They needed a mental health day anyway, I’m sure, they had been watching me go through this all summer. And so I brought them to this little hotel outside of Vegas. And they have a really nice pool and all and then I’m sitting here thinking gosh, this is probably dumb. What if I take the first pill and I have this terrible reaction and then my kids are, you know, even more scarred, because mom had to go rushing to the E.R., which thankfully didn’t happen.

Side Effects

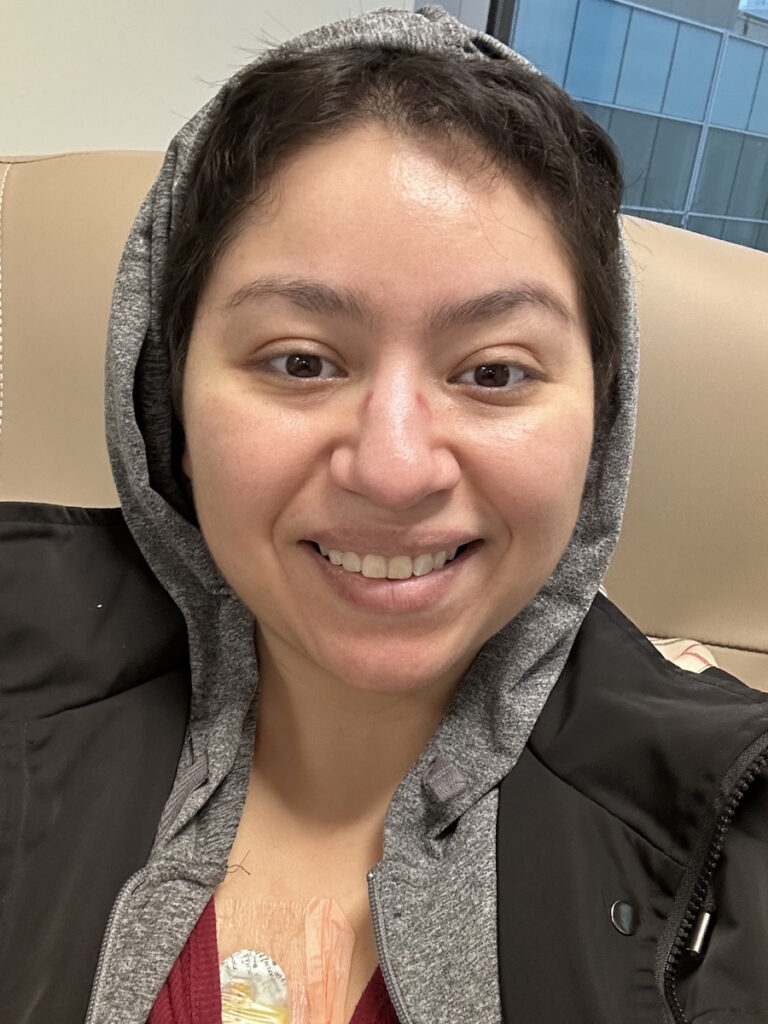

The side effects of cabozantinib were rough, to say the least.

What’s hard about being a cancer patient who’s doing one of these newer forms of treatments, like targeted therapy or immunotherapy, is you don’t typically have the same outward side effects that people recognize, whether they think of cancer patients.

I didn’t lose my hair, but it actually turned white. That’s one of the typical side effects from this type of treatment. And that was heartbreaking for me because I’m 29, 30 years old. My hair is going white; even my eyebrows went white. And it’s just all those things that you try to tell yourself, okay, the prize is I live longer and it’s true. It worked for me. I don’t regret it for a second. I would do it all over again in a heartbeat. But, you know, it does a number on you. It changes who you are.

I always say, kidney cancer helped me take the best pictures of myself that I ever took, which is terrible. I mean, I lost an unhealthy amount of weight. Honestly, looking back at pictures now is honestly kind of painful because I go, oh my gosh, I looked sicker than I realized I did

And because you don’t look like people expect a cancer patient to look, when I got back to work and all, they’d go, you’re doing great now, right? And like, no, I threw up three times before I left the house and had to drag myself out of bed because I was so fatigued and also, these targeted therapy drugs actually create a lot of GI issues. You get horrible diarrhea.

I recall standing in the grocery store aisle like about six months into my treatment, trying to pick out what adult diapers I was going to wear. I’m 30 and I’m buying adult diapers. And then I go to check out, I’m thinking, oh my gosh, this woman’s going to know, right? And she probably thought I was buying it for a grandparent or a parent or something.

You get all these side effects like it’s almost shameful to talk about. Your body is crumbling. And, again, it’s things that with traditional treatment you don’t always encounter. And of course, the side effects from traditional treatment are also horrible, too.

… if something isn’t sitting right with you even once you’re diagnosed, you know, if your doctor is telling you, oh, you should do this and something’s just not sitting right, get a second opinion. Get a third opinion if you need to.

You have to feel comfortable with your care.

NED Status

I reached NED within a year of starting Cabometyx, which is, like, insane. Incredibly hard to come across, to say the least.

I had a very rare response where I was 1 of only 2 of the 147 patients who had a complete response to treatment.

I wound up staying on Cabometyx for another about three years, because we just didn’t know what was going to happen after I had that first med scan. And so in 2020, my oncologist said, look, I think the side effects will kill you before the cancer does. Let’s see how you do coming off of it, which was terrifying because at that point it was my security blanket, right?

But I did successfully transition off Cabometyx. I stopped treatment in April of 2020, and now I have scans every six months. And thankfully I have had NED scans ever since. I just had a scan last January: I’m still NED. So I’m really, really fortunate.

And now I’m actually a patient advocate for the GU committee. And so I’m now actually working with the doctors that concluded the trial that I was on that saved my life.

So it’s honestly one of the most meaningful things that I do in my advocacy work, because it’s just a complete full circle.

Knowledge is power in every sense of the word.

You are a better patient if you are knowledgeable about your disease.

Words of Advice

I really encourage people to trust their instincts when it comes to their health. You know your body best, you know if something’s wrong with you. And I really wish I would have just kept listening to that little voice that I had in my head. You know, in my heart that said, Laura, something’s wrong. I’m glad that I finally did, because that’s what encouraged me to go to the ER that night.

Again, I would just go back to if something doesn’t feel right, listen to your body. I think even as cancer survivors, we tend to dismiss things sometimes, and so even if you’re in your cancer journey or you’re a survivor, you have to. It’s advocating for yourself as a lifelong responsibility.

And, you know, I’ve had the unfortunate gift of being not just a patient, but also a caregiver to my mom who passed away five years ago from complications of kidney cancer and lymphoma.

Also, I really encourage you, especially if you’re a younger patient who has a rare cancer, get genetic testing done. I encourage my family members to get genetic testing done, and receive their carrier for it as well.

And I always encourage anyone who has any kind of outliers in their health history that would indicate maybe they could benefit from genetic testing to take the tests. I know it’s scary to have a genetic disorder diagnosed, but I really wish I would have had the opportunity to know I had my disorder before I had cancer.

Knowledge is power in every sense of the word. You are a better patient if you are knowledgeable about your disease, which is what I really try to encourage patients and caregivers to do, to understand their disease.

And also, if something isn’t sitting right with you even once you’re diagnosed, you know, if your doctor is telling you, oh, you should do this and something’s just not sitting right, get a second opinion. Get a third opinion if you need to. You have to feel comfortable with your care. And if you’re not, you know it.

So you’re the best person that’s most knowledgeable about yourself, your body. Honor that in all the ways.

Inspired by Laura's story?

Share your story, too!

More Kidney Cancer Stories

Maria F., Kidney Cancer (Wilms Tumor)

Symptom: Back pain

Treatments: Surgery (nephrectomy), chemotherapy, radiation

...

Mia H., Kidney Cancer (SMARCB1-Deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma, Non-Sickle Cell Trait), Stage 4

Symptoms: Bad cough, fatigue, nausea

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy

...

Alexa D., Kidney Cancer, Stage 1B

Symptoms: Blood in the urine; lower abdominal pain, cramping, back pain on the right side

Treatment: Surgery (radical right nephrectomy)

...

Bill P., Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma, Stage 3, Type 1

Symptoms: Kidney stone, lower back pain, sore/stiff leg, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) blood clot

Treatment: Nephrectomy (surgical removal of kidney and ureter)

...

Burt R., Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (pNET) & Kidney Cancer

Symptom: None; found the cancers during CAT scans for internal bleeding due to ulcers

Treatments: Chemotherapy (capecitabine + temozolomide), surgery (distal pancreatectomy, to be scheduled)

...