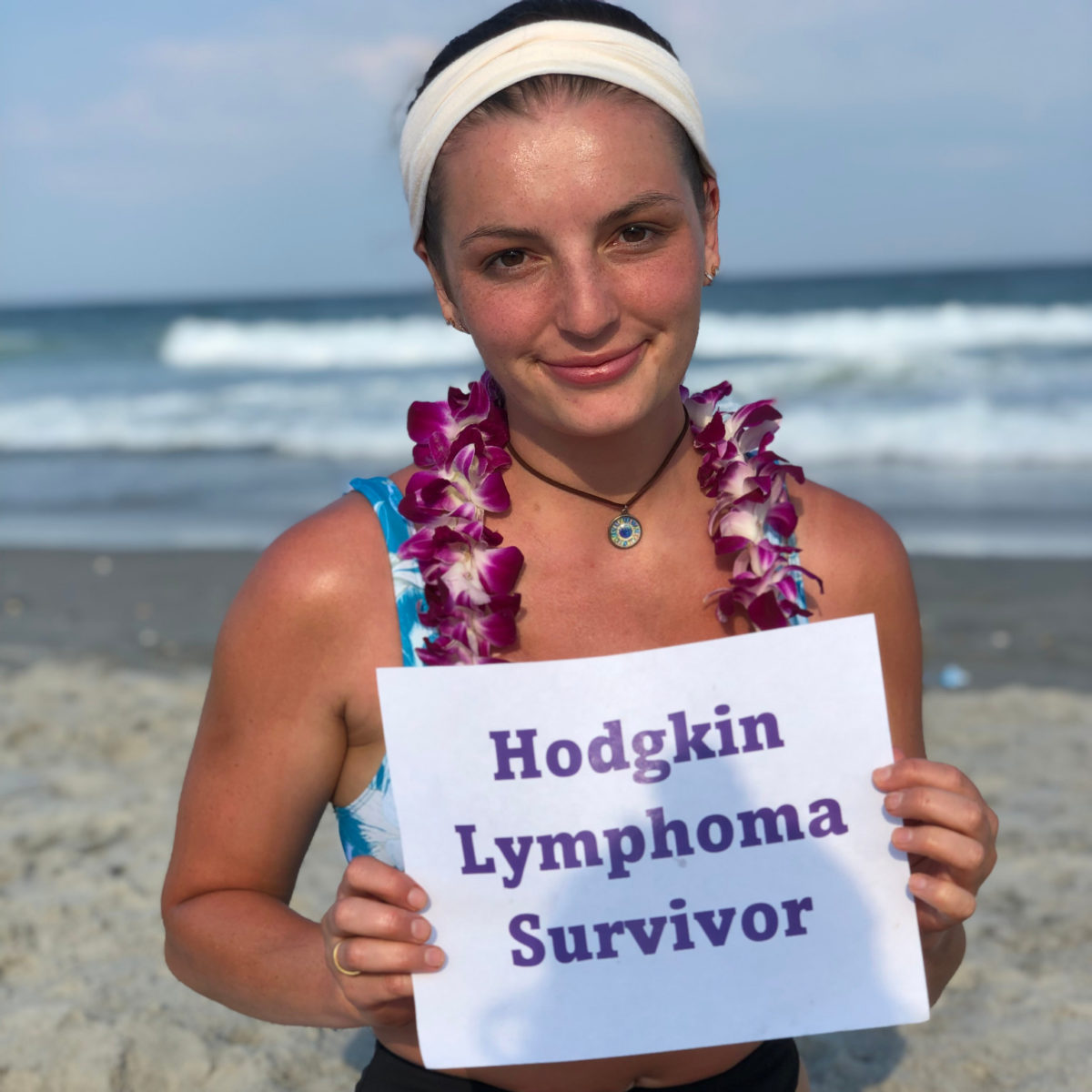

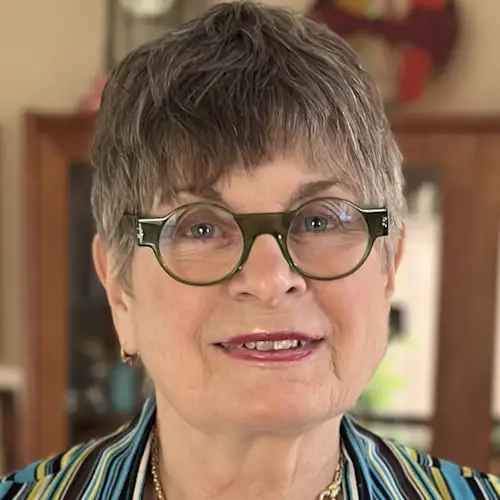

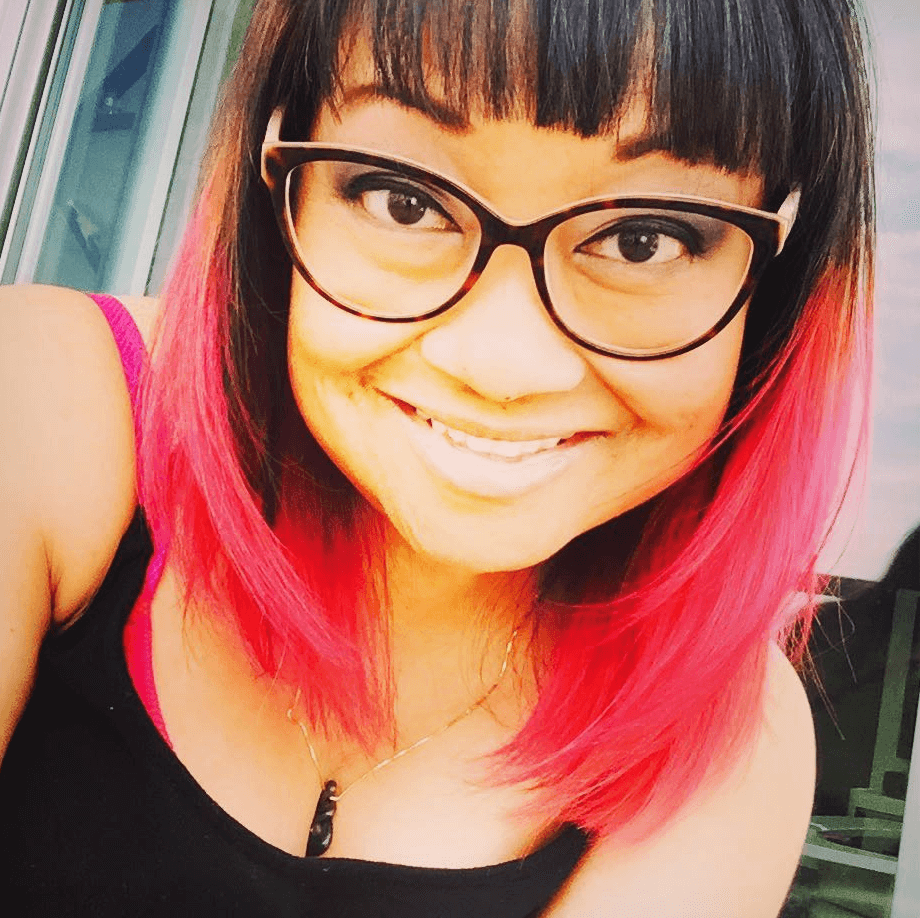

“I Knew It Was Back”: How Amanda Knew Her Hodgkin Lymphoma Was Back

A cancer relapse in college was never part of Amanda’s plans, but it became the defining experience of her junior and senior year. Diagnosed with stage 4 Hodgkin lymphoma as a junior in high school, Amanda went through grueling treatment and reached remission, only to later face a relapse as a junior in college at Baylor University.

Interviewed by: Taylor Scheib

Edited by: Chris Sanchez

In the months before her relapse was officially confirmed, Amanda noticed an alarming 15-pound weight loss that she couldn’t explain, and this led her to suspect that the Hodgkin lymphoma had come back, even though her bloodwork looked spotless. Although her oncologist initially reassured her, she still pushed for a scan. She later opened a MyChart notification in the middle of a college final and her heart sank. After the final, she read the words “likely relapsed disease” out loud to her mom over the phone, describing a moment of shock that quickly turned into survival mode.

Amanda’s Hodgkin lymphoma relapse also meant confronting big medical and life decisions. She chose to switch from an adult hospital to a children’s hospital where she felt more seen as a young adult, pursued second opinions at MD Anderson Cancer Center, and completed one round of egg freezing before starting more intensive treatment. Her treatment path included immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and an autologous stem cell transplant, and she now has immunotherapy maintenance every three weeks.

Recovery after her stem cell transplant was brutal — weeks of mucositis, nausea, passing out from dehydration, and readmission when a seizure-like episode raised suspicions that she was also experiencing neurologic issues. Amanda describes the first 100 days post-transplant as the longest and hardest of her life, but she celebrated small but meaningful victories like walking laps around Target and finally tasting food again.

Amanda’s Hodgkin lymphoma relapse has reshaped how she sees herself and her future. She returned to Baylor, danced at the famous Pigskin Revue just months after needing a walker, and now views exams and deadlines through a different lens: “If I can get through a stem cell transplant and fully recover from it, I can take my Spanish final on Friday.” She is committed to sharing her experience to offer other patients something priceless: hope.

Watch Amanda’s video and read the edited transcript of her interview below for more on her story, and click here to read about her first Hodgkin lymphoma experience.

- Listening to your body matters: Amanda noticed rapid, unexplained weight loss and trusted her gut to ask for a scan, even when her bloodwork looked normal

- Self-advocacy is essential: Her insistence on further testing led to the detection of her Hodgkin lymphoma relapse in college, and her doctors ultimately supported her choice, emphasizing her autonomy

- Treatment plans can evolve: Amanda moved hospitals, pursued second opinions at MD Anderson, tried immunotherapy first, and then transitioned to chemotherapy and a stem cell transplant when needed

- Community and connection — in Amanda’s case, family, friends, peers with similar diagnoses — can offer grounding and hope in a time when so much feels out of control

- Meaning-making beyond treatment: Amanda now uses her experience to support others, from answering messages from patients in transplant to contributing to advocacy efforts like the Give Kids a Chance Act

- Name: Amanda P.

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 20

- Diagnosis:

- Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Staging:

- Stage 4

- Symptom:

- Sudden, unexplained weight loss

- Treatments:

- Immunotherapy

- Chemotherapy

- Autologous stem cell transplant

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- My name is Amanda

- My cancer experience to date

- Life between my diagnosis and relapse

- How I knew the Hodgkin lymphoma was back

- My relapse was confirmed during a college final

- How much I understood about relapsing

- Why self-advocacy matters so much

- How my second diagnosis felt different from the first

- Why I switched hospitals after relapse

- Immunotherapy, second opinions, and my final treatment plan

- Making fertility decisions in college (freezing my eggs)

- Processing the reality of a stem cell transplant

- Why going back for the fall semester mattered so much

- How I mentally prepared for my stem cell transplant

- Losing my hair for the second time

- My community showed up for me

- What my stem cell transplant was like physically

- Recovering from my transplant

- Reaching day 100 after my stem cell transplant

- My 100-day celebration party

- How day 100 felt emotionally

- Adjusting back to college after transplant

- What this last year taught me

- What my maintenance treatment looks like now

- How it felt when my first video went viral

- How much it means to me to share my story

My name is Amanda

I am originally from Dallas, Texas, but currently live in Waco, Texas, and I was diagnosed with stage 4 Hodgkin lymphoma in May of 2021 and then again in December of 2024.

My cancer experience to date

I first had a bunch of different symptoms in my junior year of high school, which led to the diagnosis when I was just finishing my junior year. I went through six months of chemo and was in remission, but then, when I was a junior in college, I had a scan that showed my relapse.

Since then, I have done immunotherapy, a few rounds of chemo, a stem cell transplant, frozen my eggs, and now I am currently doing an immunotherapy maintenance treatment.

Life between my diagnosis and relapse

It is really a lot of the same, getting back to the same, and trying to just live my life as best as possible. I am still a Young Life leader at Lorena High School, and I am still a Tri Delta at Baylor. It has been a lot of super fun things during homecoming and semi-formal and different events like that, which have been a blast.

A highlight was definitely what we call Pigskin, which is a super niche Baylor thing where we sing and dance on stage. All of the sororities and fraternities do it, but it is a competition in the spring, and the top eight get to go back and then perform at homecoming, and I was able to be a part of the homecoming performance, which was super fun and super awesome. That has been a really big highlight, along with spending a lot of time with friends and family; my little sister just went to college, and I recently got to visit her, so a bunch of exciting things like that.

How I knew the Hodgkin lymphoma was back

I knew I had relapsed before any doctor, any scan, any blood work. I had noticed in early November of my junior year — so just a year ago now — that I had been losing weight, and I know my body very well. I do not lose or gain weight very easily; it takes a lot for me to be able to lose weight, and my weight just does not fluctuate.

Noticing that I had lost almost 15 pounds out of nowhere was definitely a big teller. I could tell by looking in the mirror that my clothes were not fitting right. I went to my oncologist about it and asked, because that was really just about my three-year mark. I was going in for blood work, and they said, “Let’s see how this goes,” and that came back completely normal.

He said, “If you are still a little on edge about it, if you are still a little nervous, we can schedule a scan,” and it was literally a couple of days later that I said I wanted the scan, so that was scheduled. During that whole time, I did not want to tell people that I was nervous or that I knew; I would say, “We will see what happens; we will see what the scan shows,” but deep down I had a gut feeling, and I knew it was back.

My relapse was confirmed during a college final

How I found out it had officially come back is a really funny story — not funny at all, but a little bit. I was at a final for my communications class; we were doing our final presentations. I had just finished presenting, got back to my seat, and opened up my laptop, and I saw that I had gotten a notification from MyChart. This was a Saturday, may I add.

I remember it so vividly. My heart sank, my heart was racing, but again, in class, I could not show it. My friend had driven me to class that day, a good friend but not a close friend, so I could not really tell her what was going on. I remember getting in this girl’s car and driving home, being absolutely terrified; I literally could not breathe.

When I got home, I called my mom and said, “Okay, I have the results; I am going to open those up and read them out loud to you.” I went up to my room, sat on my bed, opened up my computer with my mom on my phone, and literally just read, “Likely relapsed disease. These tumors in these places; they are four centimeters by five centimeters, and there is one here and one here and one here.”

I did not cry at first; I was in shock, and so was my mom. We were like, “Are you kidding me right now? This is what we are reading?” Eventually, I was like, “Okay, now what?” and she said, “I am on my way; I am driving there right now.” My dad was at the ranch house, or hunting lease, a little over an hour away, and my mom was in my hometown about two hours away, and both of them immediately got in their car and drove down here, which was very kind.

For those couple of hours, I was just here. I brought my laptop and walked across the hall to my roommate’s room, looked at them, and said, “It is back,” and that was when I started crying. The rest of that day was spent in my roommate’s bed, talking through what the next steps were.

I called my old nurse because she had ended up leaving at that point. I called her, and she said, “It is going to be okay; it will be okay,” and I said I needed to contact my doctor and that I did not have his personal cell phone number. She said she did, and she would call him. Then he called me and said he was so sorry, that I was not supposed to find out like this, but it was back, I did have cancer again, and we were going to do this chemo regimen.

He said it was probably December 14th, so we were ten days from Christmas. He said, “I will let you have Christmas, but on December 26th, you are coming in for a biopsy, and we are starting chemo before New Year’s.”

The rest of that day, my parents came, and it was really hard to see them. The rest of the day, I was in survival mode. I booked a hair appointment and said I was bleaching my hair and going platinum blond because I did not care how damaged my hair would be anymore. I had spent the last three years growing it out to the length it was, probably here-ish, and I did not care anymore; I was going to bleach it.

I booked a hair appointment for, I think, either the next day or the day after that. I had a Christmas party that night, and I thought, if I am not coming back to Baylor next semester, I am going to this Christmas party. I went to the Christmas party hours later, which, looking back, is kind of crazy, but I do remember pretty much every single hour of that day very vividly. That is how I found out; there were a lot of tears, but after the initial shock wore off, I think I bounced into survival mode so fast.

How much I understood about relapsing

It had always been a thought in my mind. I had a really bad habit of saying, “When my cancer comes back,” instead of, “If my cancer comes back.” That was a “me problem,” not anyone else’s problem. My doctor had told me that if it was going to come back, it would happen within the first two years, and after I hit the two-year mark, I thought I was home free.

I thought I was chilling and we were good. When it came to the three-year mark, seeing my doctor and all those things, and me having to ask for the scan for my own well-being, they really did not expect it at all. They were just as shocked as I was, maybe even more, because of how well I had done over the last three years.

My blood work was spotless. The first time I was diagnosed, my blood work was a mess, and my blood work being in pristine condition this time also made them not really think that relapse was a possibility. When it came to telling me about the diagnosis, I read it through MyChart and then was able to get a phone call after telling my nurse I had found out. She did not even work there anymore, and I said, “Hey girl, this is what is going on; I need you to contact my doctor right now.”

Finally, he called me and walked me through what he would consider the next steps, which ended up not even being what we did. He was very much like, “This is what we are going to do; this is when we are going to do it,” and walked me through the whole thing within hours of getting the diagnosis.

Why self-advocacy matters so much

Every person knows their body best. Nobody can tell you how you feel; you know how you feel. I could tell my doctor all day that my body does not fluctuate in weight, but they could sit there and say everyone’s weight fluctuates, that I was fine, that ten pounds is nothing, and that I should be happy or thrilled that I was losing weight without trying.

In reality, most girls my age would probably be jumping up and down at that, but I was literally terrified. Not even because weight loss was the first symptom for me in the beginning, but because I knew a lot about my kind of cancer. With Hodgkin, a really big first symptom is weight loss — unintentional, within a couple of months, losing somewhere in the double digits.

My doctor was really great in letting me choose what I did in order to have reassurance. He said, “If you want a scan, we can get you a scan. I can tell you that you do not need one, but it is ultimately your choice. You are the adult in this situation; it is your body.” His giving me that autonomy was really kind.

How my second diagnosis felt different from the first

They were very different feelings. The first time I was diagnosed, I was naive; I did not know what the future held. I did not know what I was going to go through or how it was going to affect me. I did not know how chemo felt, I did not know how I would look bald, and I just did not know.

Because I was so unaware, I got to live in this bubble of, “I do not know, but we will see.” That is not the case for everyone; a lot of people hear “cancer” and are immediately scared, but my doctors at the time did a really good job of reassuring me that I would be okay, that I would be fine, and that we would get through it. I was very naive and unaware of what I would go through the first time.

The second time, I knew exactly what was going to happen. I know how much chemo sucks, I know how painful the grow-out hair phase is, I know what it feels like to not have an appetite and how awful mouth sores are. Because I already knew, I was filled with more dread and fear, especially with the stem cell transplant looming over my head.

I had been told pretty much since day one that if it ever came back, I would get a stem cell transplant, and having that looming over me brought a lot more dread and fear the second time around.

Why I switched hospitals after relapse

Originally, they had told me I was going to start chemo pretty much immediately, and then as soon as I hit remission, I would have a BEAM auto stem cell transplant. They said I would get a biopsy to confirm it was, in fact, the same type of cancer, get my port placed, be admitted, and do chemo.

I had been saying for a long time, as a 17, 18, 19-year-old going to the adult hospital, that I hated it. I despised that place; there are lots of bad memories there. Everyone there is generations older than me, and I did not really feel seen or understood. There were a lot of things my doctor would not really think about, like how the chemo would affect my pulmonary function 40 years down the line, because most of their patients are already 60, 70, 80 years old and are not going to live another 40 years, so that is not where their head goes.

I had said from very early on, especially after meeting so many friends online at children’s hospitals, that if I ever relapsed, I would move hospitals, go to the children’s hospital if I still could, and start from scratch. A mix of bad memories, PTSD, anxiety surrounding my old hospital, and wanting a different perspective this time around led me to switch to the children’s hospital.

I got a whole new care team, a whole new hospital, and a whole new set of nurses. A lot of my care team from the previous time had left, so it was really just my doctor still there, and I was already going to have new nurses and a new PA. Switching was not the biggest change, and looking back, I am so glad that I did.

Immunotherapy, second opinions, and my final treatment plan

Those doctors said, “No, slow down. You have time. Hodgkin is thankfully a very slow-growing disease.” I was able to do two rounds of egg freezing and now have 12 eggs in a freezer, which is super great and something I am really thankful I had the opportunity to do.

They said, “Let’s not jump to chemo if we do not have to yet; let’s start with something that might work first,” so we started with immunotherapy. I did a couple of rounds of that and ended up getting secondary opinions at MD Anderson, bouncing between the children’s hospital and MD Anderson.

Unfortunately, at MD Anderson, I was in the adult wing, and I was bouncing between the two — doing hometown treatments at children’s, going to MD Anderson, which made the final call on all treatment protocols. I did immunotherapy for a bit; it worked, but not as well as we wanted, and that scan was really hard.

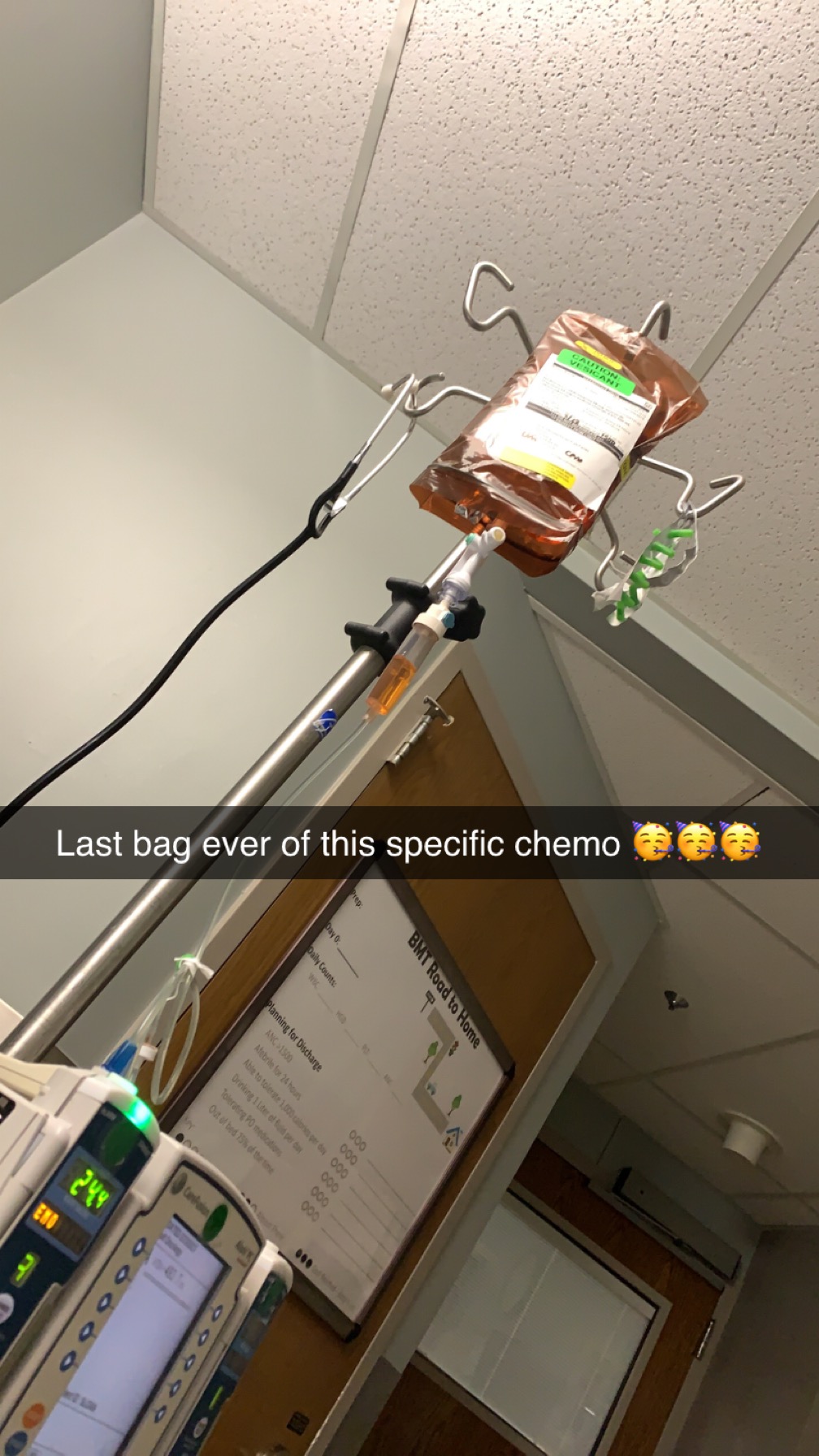

We immediately jumped into the chemo regimen that my doctor had wanted to do previously, but luckily, I only had to do two rounds of that. Then I was in remission and able to go into my stem cell transplant, which I had done at MD Anderson because they had a slightly different regimen. Now I am back at the children’s hospital, doing my immunotherapy.

It has been a lot of bouncing around, different decisions, and different opinions; we went back and forth on what treatment to start with about a million times, but that is what we ended up doing.

Making fertility decisions in college (freezing my eggs)

I was very grateful that I had the time and that option. I know that is not an option for everyone and that I am definitely in the lucky few who can do this. It was really a no-brainer to do it at least once.

I did the first round of freezing to see how many we could get. I knew my egg supply was not at 100% because of my previous treatment, but we knew it was still there. After the first round, we got seven eggs, and I was told the “magic number” was ten, meaning ten would “guarantee” you one child.

That was really hard and involved going back and forth between me, my parents, my doctors, and all the people involved in deciding whether to do a second round. They said the second round would probably yield fewer eggs, but it would probably bring that number up to ten and could almost guarantee a child rather than just seven.

We had to decide whether to start treatment right away to get rid of the cancer or do another round of freezing, which would postpone treatment by about two to three weeks. I found out about the relapse in mid-December and did not start treatment until mid-February. Giving it all that time to grow and spread was not comfortable, but looking back, I am really glad I did it.

The decision to actually do egg freezing was a no-brainer, but the decision of whether or not to do it twice was harder.

Processing the reality of a stem cell transplant

I was terrified. I was fully, fully terrified. I had never been in the hospital for that long before, and the decision of whether to do it at MD Anderson or at home in Dallas was really hard; we went back and forth on that forever.

I was terrified because of how many risks it would bring. Pretty much the only word I can think of is “absolutely terrified.” I talked a lot about it with my therapist and how terrifying it was going to be. There were a lot of unknowns — I did not know what was going to happen or how I was going to react.

My doctor or a nurse told me, “We are pretty much going to bring you as close to death as possible and then save you,” and that was terrifying. I think my stem cell transplant doctor did a decent job preparing me for what to expect. He said I was going to lose probably upwards of 30 pounds, would not eat for a long time, my taste would be messed up, I would have horrific mouth sores, lose all my muscle, and be empty.

I thought, “Okay, this is real, and this is coming up.” I wanted to get it done as soon as possible because the sooner I could get it done, the more time I would have to recover until the fall semester. The goal, from the second I was diagnosed through treatment, chemo, and the stem cell transplant, was getting back to school in August. I thought, “I just need to be able to get back to school in August, and everything will be okay,” and having that goal helped.

Why going back for the fall semester mattered so much

The “decision,” which was not really a decision at all, was that I was forced to stay home that spring semester. That was really hard; I did not realize how hard it was going to be. I drove back and forth as much as possible, and every time I went into the clinic, they would ask if I was going to Waco that weekend, and I would say yes.

I just wanted to be back. It was my senior year, and having my independence stripped away from me after not having it for that long — and stripped away without any choice — was really hard. It gave me a good goal and something to look forward to through such a difficult time.

I really wanted to be back with my friends and get back on track with classes and everything to continue moving forward in my life.

How I mentally prepared for my stem cell transplant

In the weeks and months leading up to the transplant, there was a lot of impulsivity and trying to enjoy everything as much as possible. My biggest fear was that the transplant was going to kill me, and that thought loomed in the back of my mind.

Leading up to it, my doctor would warn me that going to my sorority formal with hundreds of people was not the best idea when I was neutropenic, and I would say I did not care and that I would be there. I put my N95 on and went to the sorority formal.

I did not go on big vacations; we did a spring break trip, and I had a New York trip planned that ended up getting canceled. I focused on seeing my friends as much as possible, hanging out with them, going shopping, going line dancing, going to all of the sorority events, and doing everything I could possibly do.

I did my very best to do as much as possible because I have bad FOMO, and I had that thought in the back of my mind — what if this is my last shot or my last time? Doing as much as possible was the priority; some of it was probably dangerous, but here we are.

Losing my hair for the second time

The second time around, losing my hair was almost the same as the first time, but not quite. Again, I went platinum blond for a couple of months. I did not lose my hair until the end of March, right before I started chemo, after a little bit of immunotherapy and a couple of rounds of chemo.

Before that was when I shaved my head. I had a scan at MD Anderson that showed the immunotherapy did not work as well as we wanted and that we would have to do chemo. I immediately texted all my friends and said I was on my way to Waco and that we were going to have a buzz party that night because I was getting chemo the next day.

This all happened within 48 hours, and every single person I texted was there, which was awesome — that they were all able to drop everything and be there for me. It was a really kind and really awesome memory for a not-so-awesome occasion.

My friends and I went to get bleach, hair ties, and scissors, and we also got a cake. The cake said “In My Britney Era” to commemorate my buzzcut.

There is a super cool organization based out of Florida that makes halo wigs out of your hair. One person’s full head of hair is not enough to make a full wig, but you can make a halo wig where the hair is sewn on a track that goes from your temples all the way around, with a sock cap on top. I could wear that, put my hat on, and you would never know it was a wig — and it was my real hair.

We sectioned off my hair into tiny ponytails and cut those off, then shipped them off. It was important to shave my head before starting chemo so I could send them as much hair as possible. All of my friends took turns cutting a ponytail, and eventually I had a really messy buzzcut. Then we took clippers, evened it up, and bleached it to go platinum buzzcut, which was pretty epic.

I loved the look. Again, I had a buzz party complete with cake and everyone taking turns cutting a piece; some of the same people as last time, but mostly different because it was in my college town, with all my college friends and my siblings coming down for it.

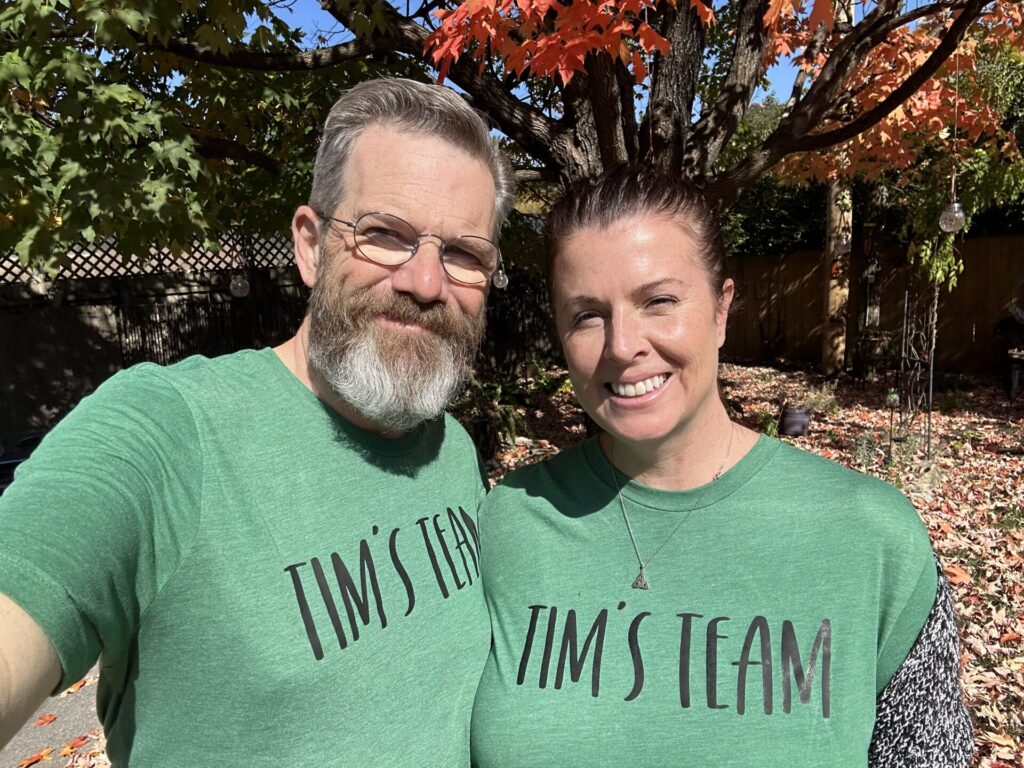

My community showed up for me

They are literally some of the best people ever.

The people I have met at Baylor are some of the best people I have ever met.

My community, my friends, and my family are probably the most important things in my life.

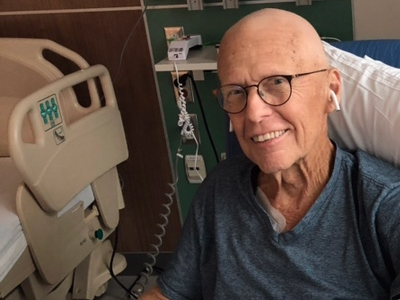

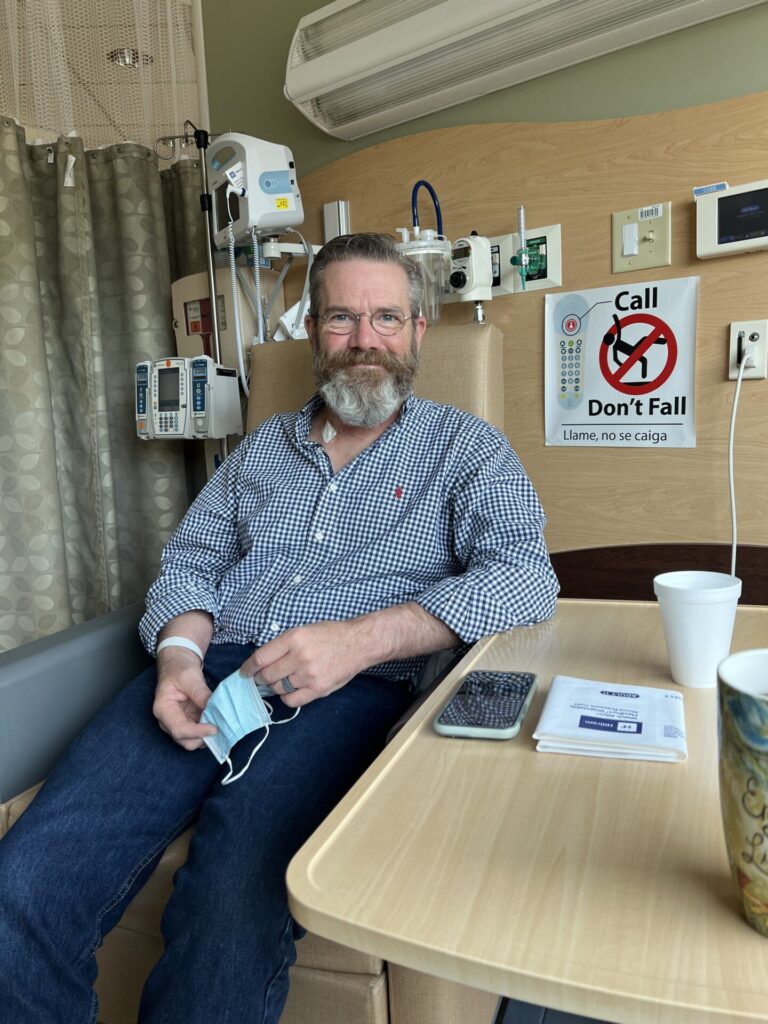

What my stem cell transplant was like physically

The transplant itself was pretty successful. I got a central line, did a bunch of chemo to knock out everything, and then got my stem cells, and that whole process was not that bad. The chemo did not feel super terrible in the moment, and the G-CSF shots leading up to it were not the most painful.

There were a couple of instances where I was left in a lot of pain, especially when I got my port removed and my central line placed at the same time, which left me in a lot of pain and landed me in the ER for pain minutes after. That was really rough.

So much of it is a blur; I think my brain has tried to block out a lot. There were a lot of tears, and I remember having sores in the corners of my eyes from crying so much. I was really just in and out of sleep, talking nonsense according to my parents, not keeping much down, not eating a lot, and not moving a lot.

I did my best; I loved the PT people — they were lovely humans — but I hated when they came to my room and made me do laps around the hallway. MD Anderson had a really cool system where you would do laps and collect little paper stickers, and when you had 12 (equaling a mile), you would get a bandana to tie around your IV pole.

We would say, “Okay, today we are going to walk two laps around the floor.”

Recovering from my transplant

Staying on the floor for so long and not being able to leave was really hard, especially at first; I was so antsy and kept asking them to let me leave. Later, it got to the point where I was so out of it that I did not realize I had not breathed fresh air for three weeks.

The recovery was the hardest part. From about day +3 or +4 up to around day +30 were the hardest and were unbearable. It was a lot of my parents saying, “Okay, Amanda, let’s walk to the couch today.”

It was a mix of feeling very depressed and hopeless, feeling like I would never gain my strength back, and also feeling so exhausted and broken down that I said no. My parents could ask me to walk down the hallway as many times as they wanted, but it was up to me and what I decided to do.

I had a very scary moment about five or six days after I got out of the hospital. I had gotten out on day +13, which was really early compared to a lot of people, and I should not have gotten out that early, because I just landed myself right back in.

I had such bad mucositis, lost all my taste buds, and could not taste anything. I was still incredibly nauseous from all the chemo. I was eating and drinking almost nothing; I had about eight ounces of chicken broth once a day, maybe a little water to take my meds, and even half the time that would not stay down.

I was back at the doctor’s office for blood work a couple of times a week post-transplant while living in Houston, but not inpatient. I was sitting there with my mom and sister, and I said I felt really hot. I was wearing a sweater, so my mom came over to help me take it off, and I passed out.

I went unconscious. I do not remember it, but according to my mom, I was having a seizure-like episode. My doctor immediately said I was back on the floor, and I got readmitted that night. The same thing happened two more times.

It was a really scary couple of days trying to figure out if it was a seizure or something else. We had a scan that showed a weird thing in the back of my brain, and they did not know what was going on. We still are not fully sure, but we think it was due to a sodium imbalance from my not eating or drinking at all.

Throughout this whole year, I had passed out a handful of times, mostly from dehydration and not being able to keep things down or wanting to eat or drink. Passing out was not new to me, but whatever else had been going on was new.

That was a big setback in recovery. After that, I just felt like I needed to get home; I could not be in the city of Houston for one more second and needed out. Soon after that, they gave me the green light to go home, and I was able to go back to my family.

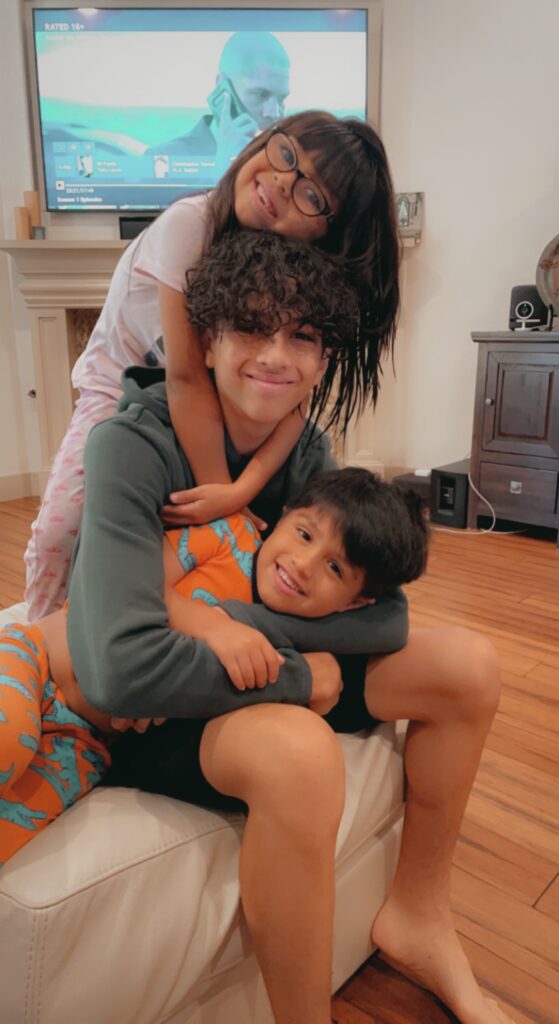

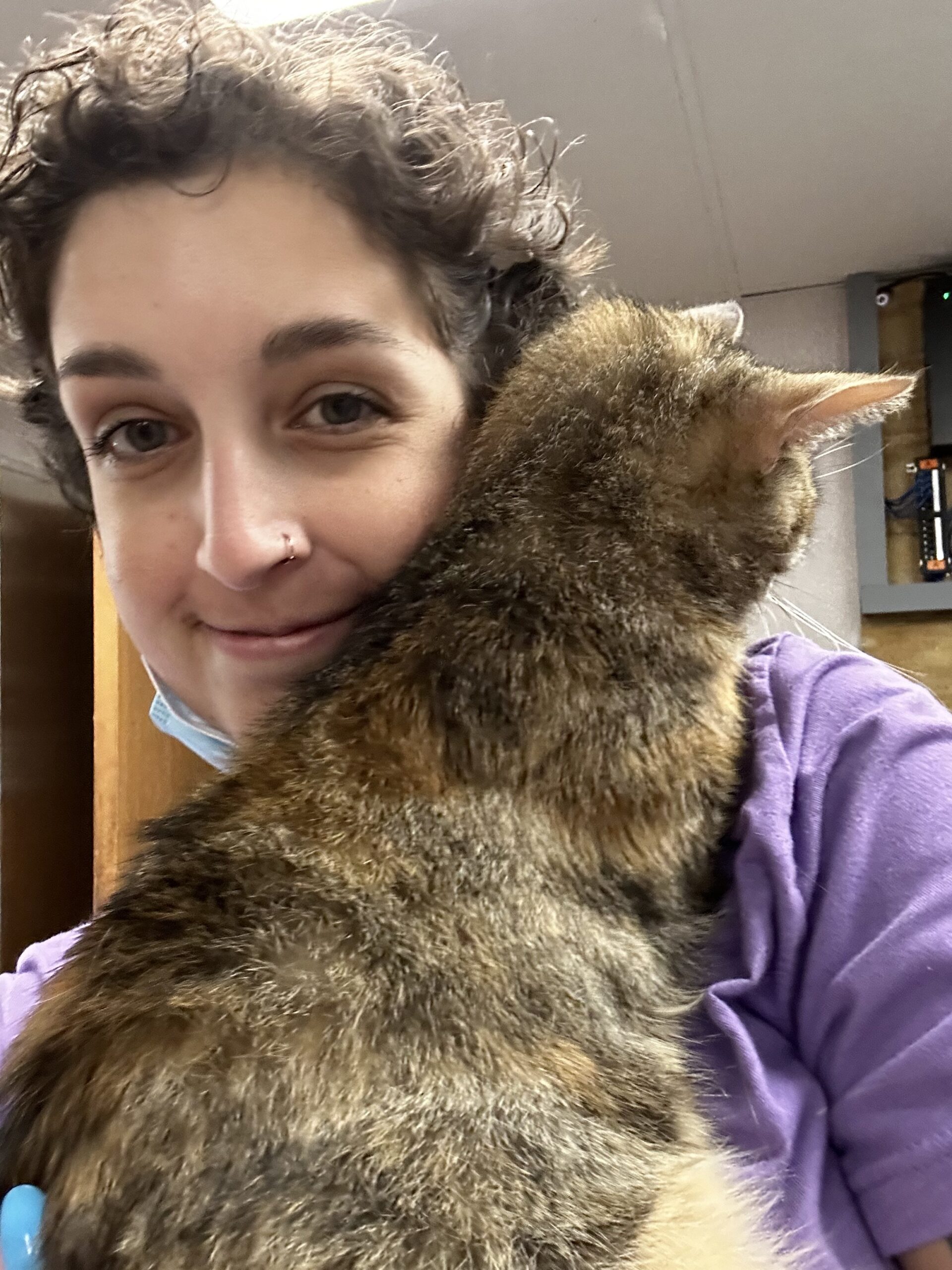

Getting out of there was awesome, and being back home with my siblings, parents, cats, and hometown friends (who were home because it was summer) was really great. Getting back home helped a lot and sped up recovery.

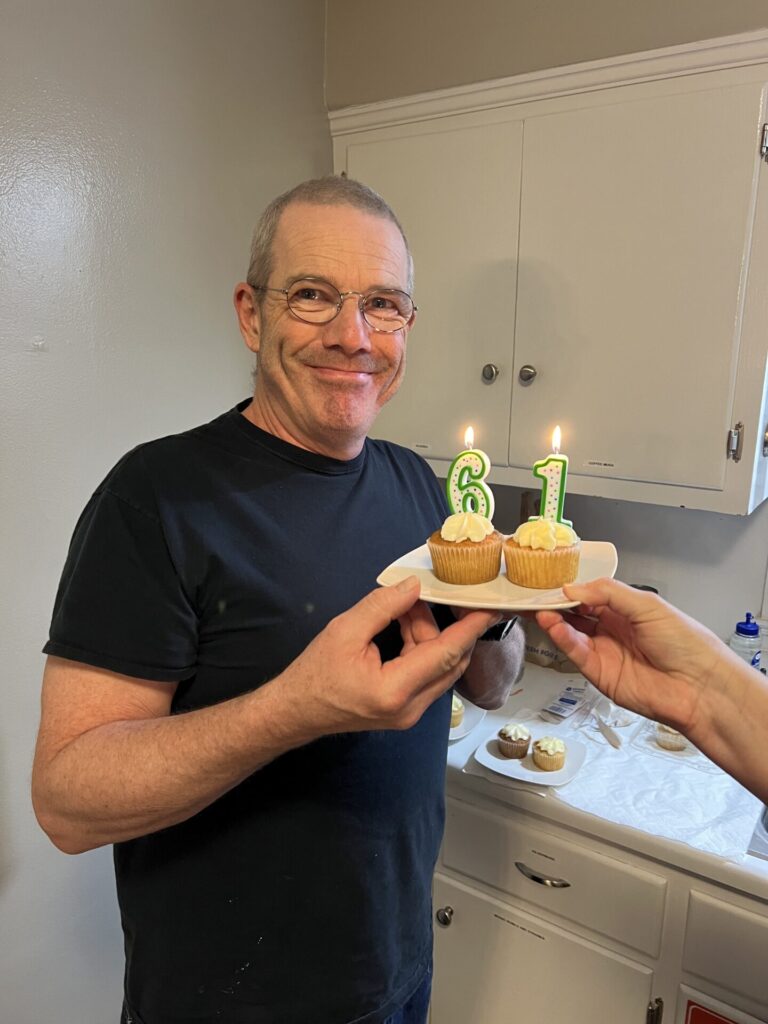

Reaching day 100 after my stem cell transplant

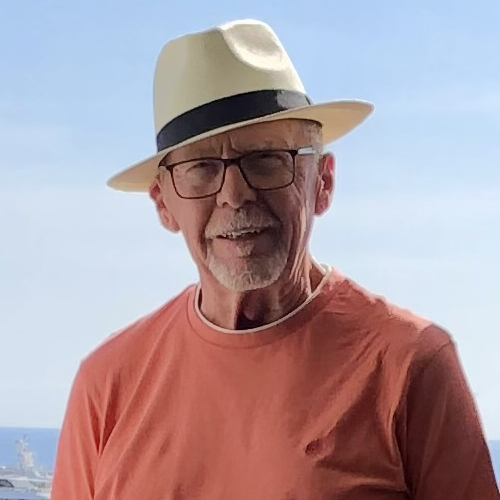

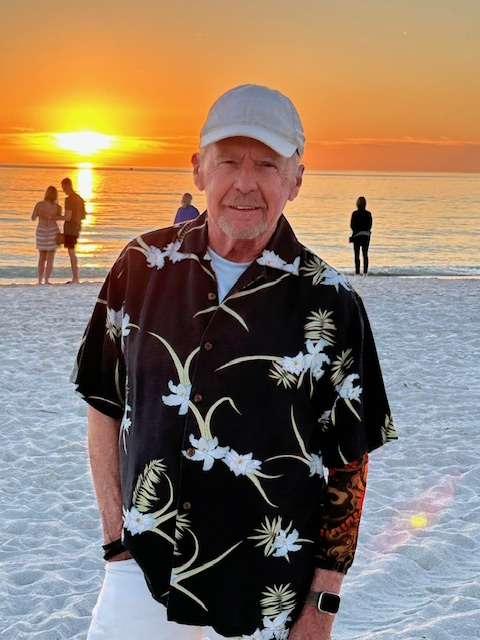

It was rough to get to day 100. It was the longest and hardest 100 days of my life. It was a lot of sleeping and a lot of walking; my dad and I would do laps around our living room.

We spent a lot of time trying to find foods that would sit well, foods I could taste, and that did not taste like cardboard. We started with cheese, cucumbers, and Cheerios, and were on the cucumber, cheese, and Cheerio diet for a while. I went through boxes and boxes of Cheerios.

I spent a lot of time in bed, pretty much all day, sleeping, then getting up to walk a couple of laps around the living room. A hard thing was that it was summer in Texas, so it was blazing hot outside. As someone with no energy, getting outside in that heat made it impossible to do anything.

The first time I was out of the house, we went to Target and TJ Maxx, and I thought this was my big outing, walking around the store. I was using a walker to walk most of the time and was not able to walk unassisted. Being able to go to the store and use a grocery cart as my walker gave me a sense of normalcy.

I used shopping as exercise, walking around the store, which got me out of the house and out of bed and gave me a little normalcy. That summer, everyone else I knew was studying abroad, doing internships, and traveling, and I was looking forward to going to Target for 45 minutes.

That is how I spent pretty much those 100 days of summer, since I got my transplant on May 29th and my 100-day mark was on September 6th. Getting my taste back and going back to all my favorite restaurants was really fun. I spent a lot of time shopping and with my friends and family.

My 100-day celebration party

Getting back to school was awesome. About a week and a half into school, my 100 days hit, and the party was epic. It was so fun and awesome.

There were decorations, a ton of balloons, and catered food. I want to say there were about 60 people there, a mix of hometown friends, my parents, my parents’ friends, family friends, and a couple of other cancer survivors, which was really cool.

We did a lot of talking and had a good time together. We took a lot of pictures. I got to share the speech I was going to give two weeks later in DC with all my family and friends, which was super cool. My grandparents flew in for it. It was epic and so fun.

How day 100 felt emotionally

The first 20 to 30 days post-transplant were incredibly hard, but it only got easier. Once I hit about the 45-day mark, things felt like they were plateauing, and I was getting more frustrated, feeling like I was not improving as fast as at first.

That was really hard. The closer it got to day 100, the more excited I was, as things were starting to get back to normal — going back to school, being able to eat good food, going to classes, and being able to walk on my own.

I have amazing friends who have gone through transplants before. One girl in particular, my friend Elena, also had Hodgkin twice and got a stem cell transplant the second time. She is really the only person I know who had an auto transplant for Hodgkin lymphoma.

I talked to her all the time, asking what she did when certain things happened, how she felt, and how she got through it. Having someone like her to guide me through all the different things was so great and helpful to give me hope. Her transplant had been exactly a year prior, and seeing her one year out — studying abroad, living her life, and doing great, fun things — gave me hope.

Seeing her in that state made me think that if someone else had done it, I could do it. Having her encourage me along the way was very helpful and crucial.

Adjusting back to college after transplant

There was definitely a learning curve in trying to figure out how to balance my time and recovery. I needed more sleep and naps, and sometimes I did not have the energy to do my homework or make it to class.

My professors have been wonderful in working with me and helping me in the transition, which was great. It was harder at first.

We had Pigskin, and a big goal for me was being able to dance on that stage at the end of October. When that happened, it was very emotional and bittersweet. After the last show, I thought, “Wow, I did that.”

I was not able to walk on my own five months prior, and now I was dancing on stage in front of thousands of people. That was a huge, pivotal moment for me and a big “Wow, I did that, and I am back.”

It was definitely a transition at first, but worth it. All of the help from friends, family, and professors made the process ten times easier than it would have been.

What this last year taught me

What I have learned the most is that I can literally do anything. When things come my way, I think that nothing will ever be harder than what I went through this year. Nothing will be worse or as hard.

If I can get through a stem cell transplant and fully recover from it, I can take my Spanish final on Friday. It makes everything else feel less daunting. I could be super stressed out about this Spanish final — should I be more stressed? Yes, but it does not affect me as much as it might affect my peers.

A lot of my peers are super stressed; they say they need certain dates for events, or that they need hours to study for an exam, and cannot go to social things because they need to study. I think, “I did not survive that, live through that, and work my butt off the last six months to get here and cancel plans.“

I am not doing that. I am doing as much as possible because I can. I am grateful and honored to be able to do things, go to social events, hang out with my friends, and do fun things; I am not canceling.

I am not letting things stress me out on so many fronts. That is one of the biggest things I have learned.

I have also learned how amazing my friends and my community are. I have grown closer and spent so much time with my sister, parents, and brothers.

Someone else said this, not me, but it was an awful circumstance to have to move home, rely on my parents so much, and lose so much independence, but how many normal 21-year-olds can say they got that much one-on-one undivided attention from their parents?

As much as I hated the circumstance I was in, I was also really grateful to have that time with my parents that most people my age are not getting. I have also learned how amazing and “freaking” awesome all of my friends and family are, and have seen everyone show up, which has been cool to watch.

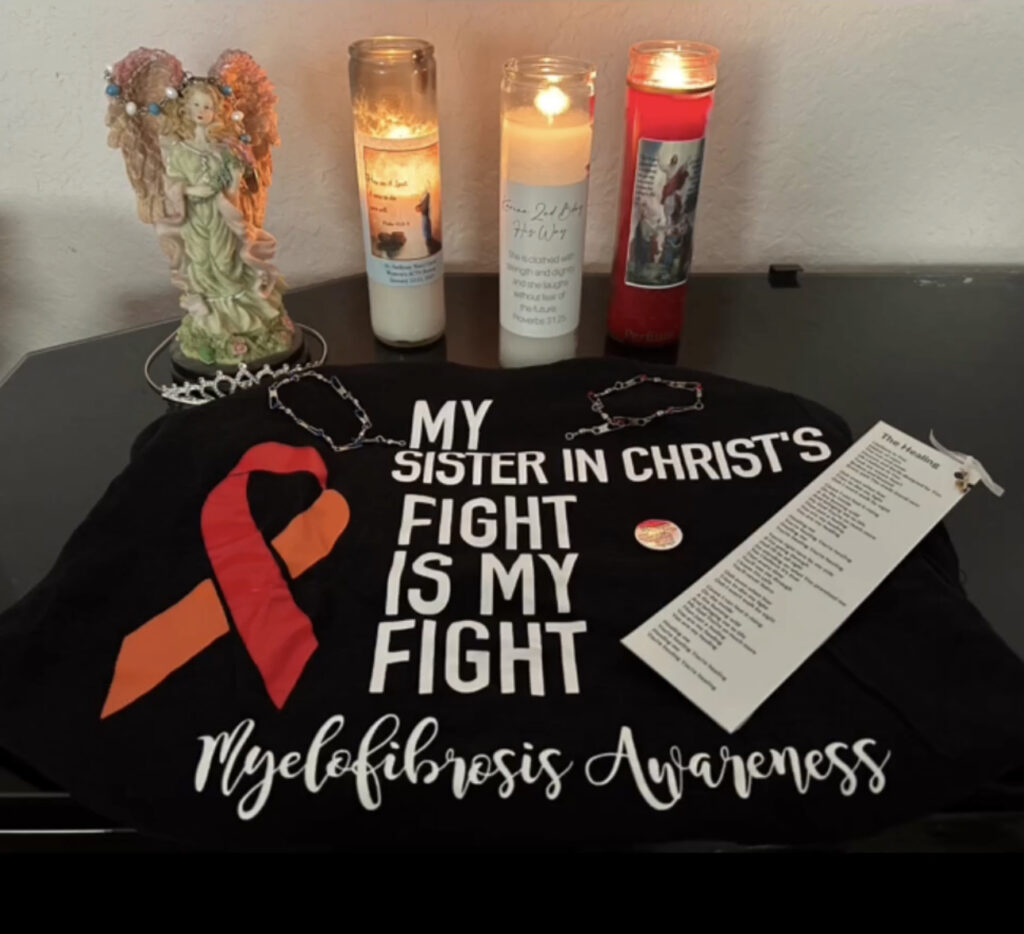

I have met even more people online through all of this and have been able to speak to people about my experience and get legislation changed. As of right now, the Give Kids a Chance Act has been passed in the House of Representatives and is about to be voted on in the Senate, and being a part of that has been really cool.

There have been a bunch of different opportunities that I would not have had otherwise, so there are a lot of things to be grateful for.

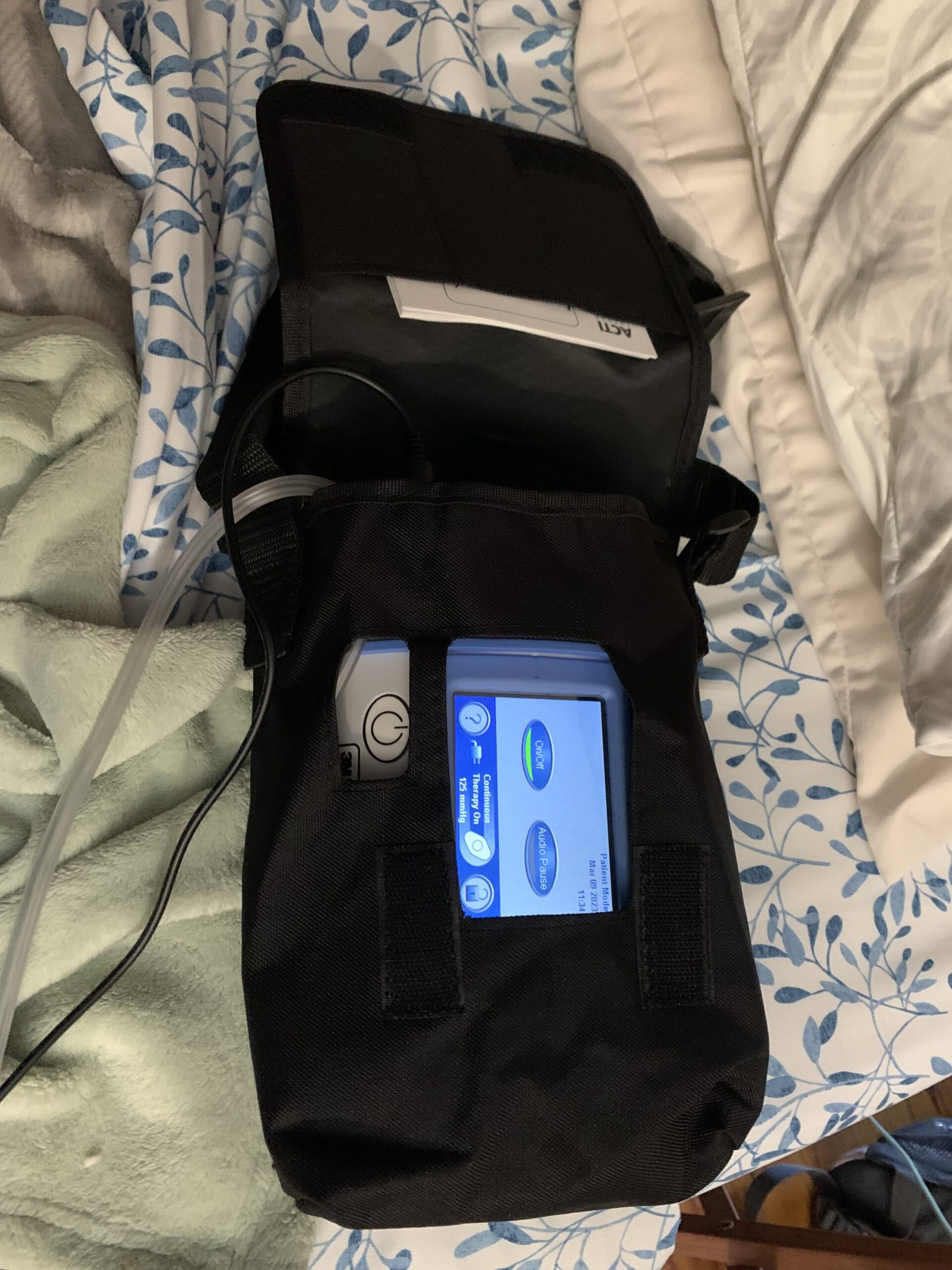

What my maintenance treatment looks like now

Right now, I am doing maintenance treatments of immunotherapy every three weeks. I go into the children’s hospital and get that infusion. I am going back to MD Anderson for scans every six months.

In between those six-month scans, I am doing blood work and maybe scans at the children’s hospital. Again, it is a lot of going back and forth.

I have three more infusions of immunotherapy. I should hopefully ring the bell for all of my treatment for the relapse at the beginning of February 2026, and finally be done with all treatment.

After that, I will have scans every six months and checkups in between.

How it felt when my first video went viral

I was just blown away. I was honored that so many people wanted to listen to me talk and that many people cared about what I had been through and wanted to hear my perspective.

One of the coolest things I have been able to do with my diagnosis is share my story, and seeing that in a quantified way was really cool. I felt honored.

When I was first getting diagnosed, I was trying to look for other people having the same symptoms that I was, and that is when I found The Patient Story. I thought, “This girl on this random blog five years ago was having the same symptoms that I am. Yes, she has cancer; I do not want cancer, but if that is the answer, that is the answer; there is nothing I can do about it.”

Being able to share my story and hopefully help people in a similar way that The Patient Story helped me in that moment was full-circle and really cool.

How much it means to me to share my story

It means so much. It has truly been such an honor. The text messages I get from people saying, “I am about to go through this stem cell transplant,” or, “I just had a stem cell transplant, I am on day +10, and I am having a really hard time, but seeing that you got through that has helped me so much and given me so much faith and hope,” mean a lot.

If I can do one thing on this earth, it is to give people hope. If I can do that, I feel like I won a million dollars. It is so much bigger than anything else I could do in my life.

It is such an honor, and I am very glad and humbled that I have been able to do really cool things like this.

Inspired by Amanda's story?

Share your story, too!

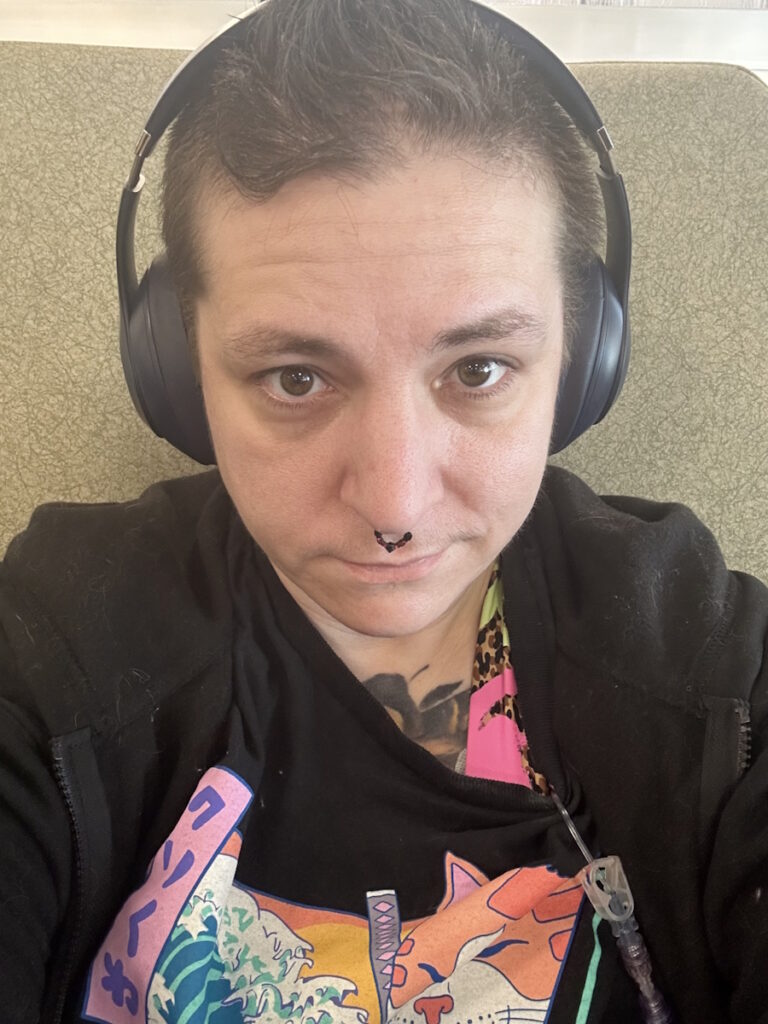

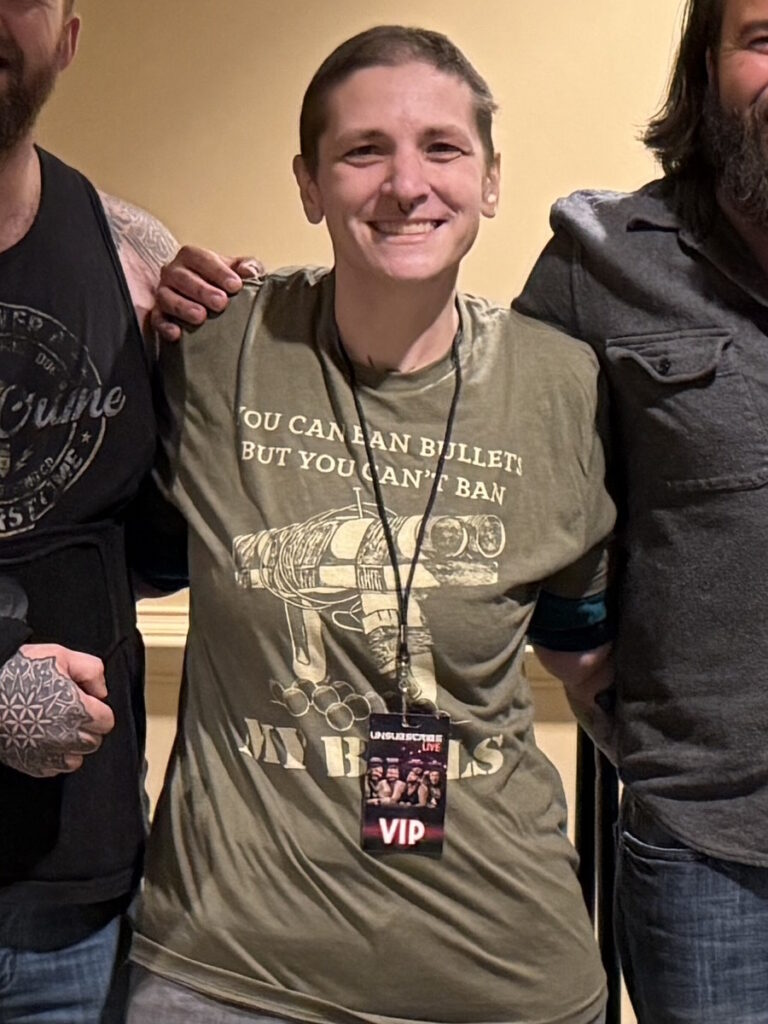

More Hodgkin Lymphoma Stories

Jessica H., Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Stage 2

Symptom: Recurring red lump on the leg (painful, swollen, hot to touch)

Treatment: Chemotherapy

Riley G., Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Stage 4

Symptoms: • Severe back pain, night sweats, difficulty breathing after alcohol consumption, low energy, intense itching

Treatment: Chemotherapy (ABVD)

Amanda P., Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Stage 4

Symptoms: Intense itching (no rash), bruising from scratching, fever, swollen lymph node near the hip, severe fatigue, back pain, pallor

Treatments: Chemotherapy (A+AVD), Neulasta

Brescia D., Hodgkin's Lymphoma

Symptom: Swelling in the side of her neck

Treatment: Chemotherapy: 6 rounds of ABVD