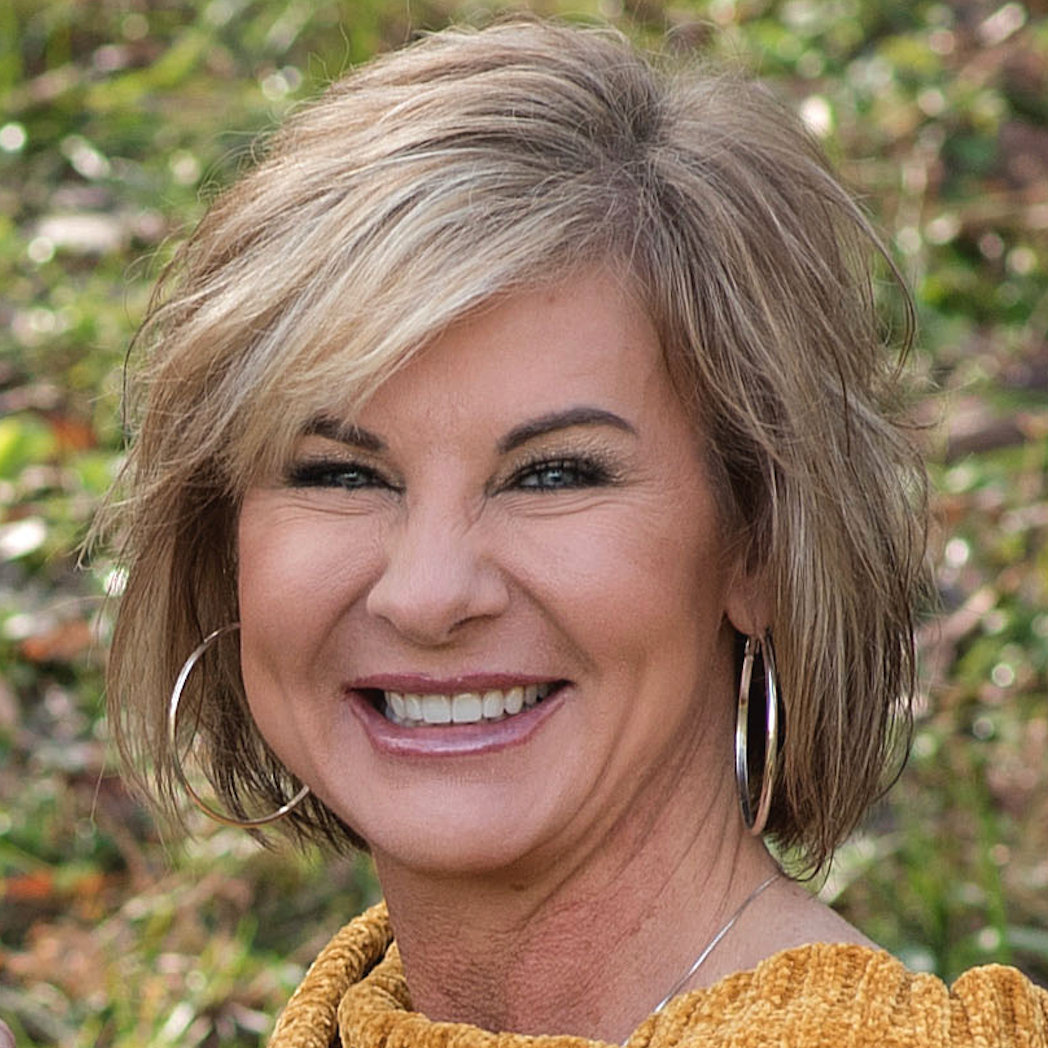

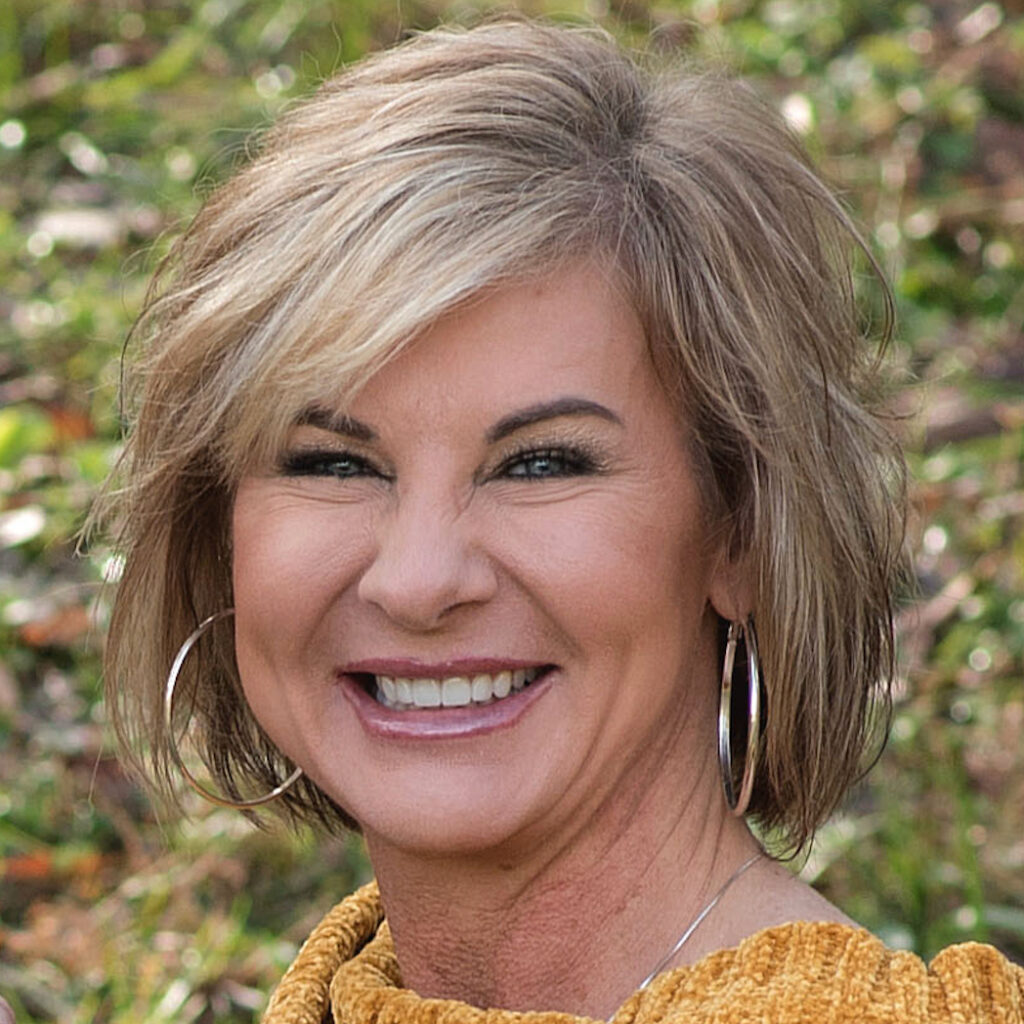

Natalie’s Stage 4 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Story

Interviewed by: Nikki Murphy

Edited by: Chris Sanchez

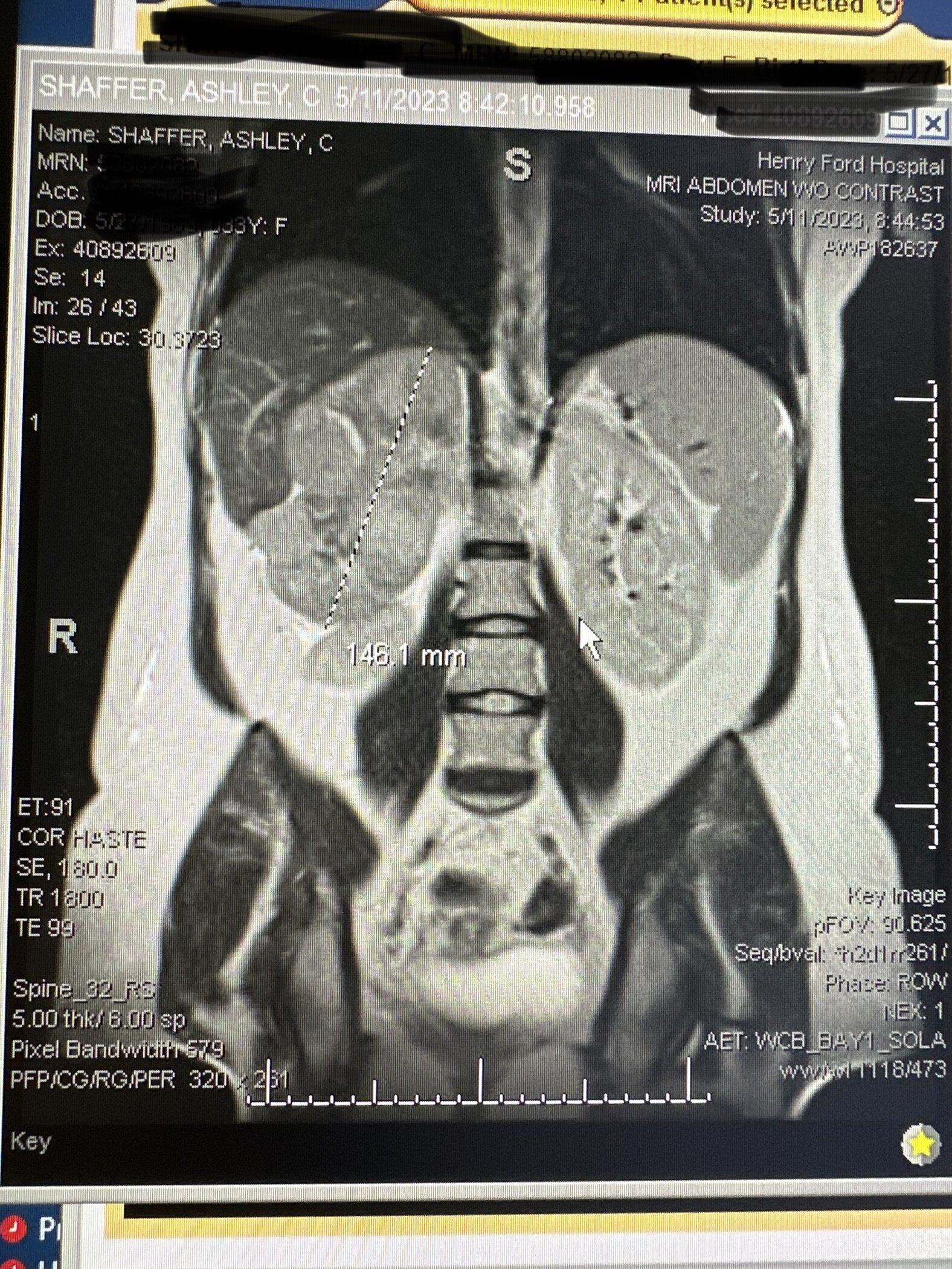

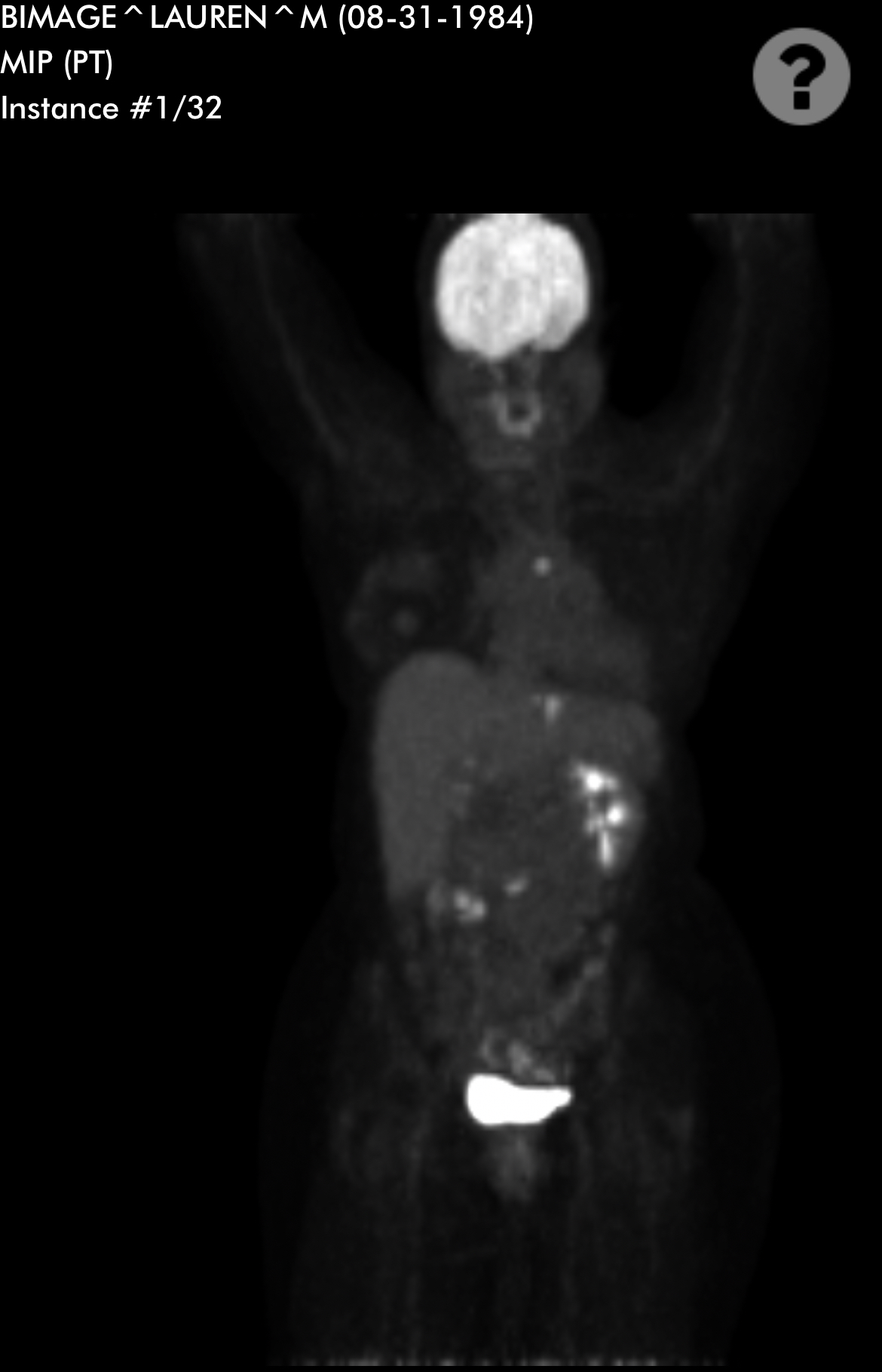

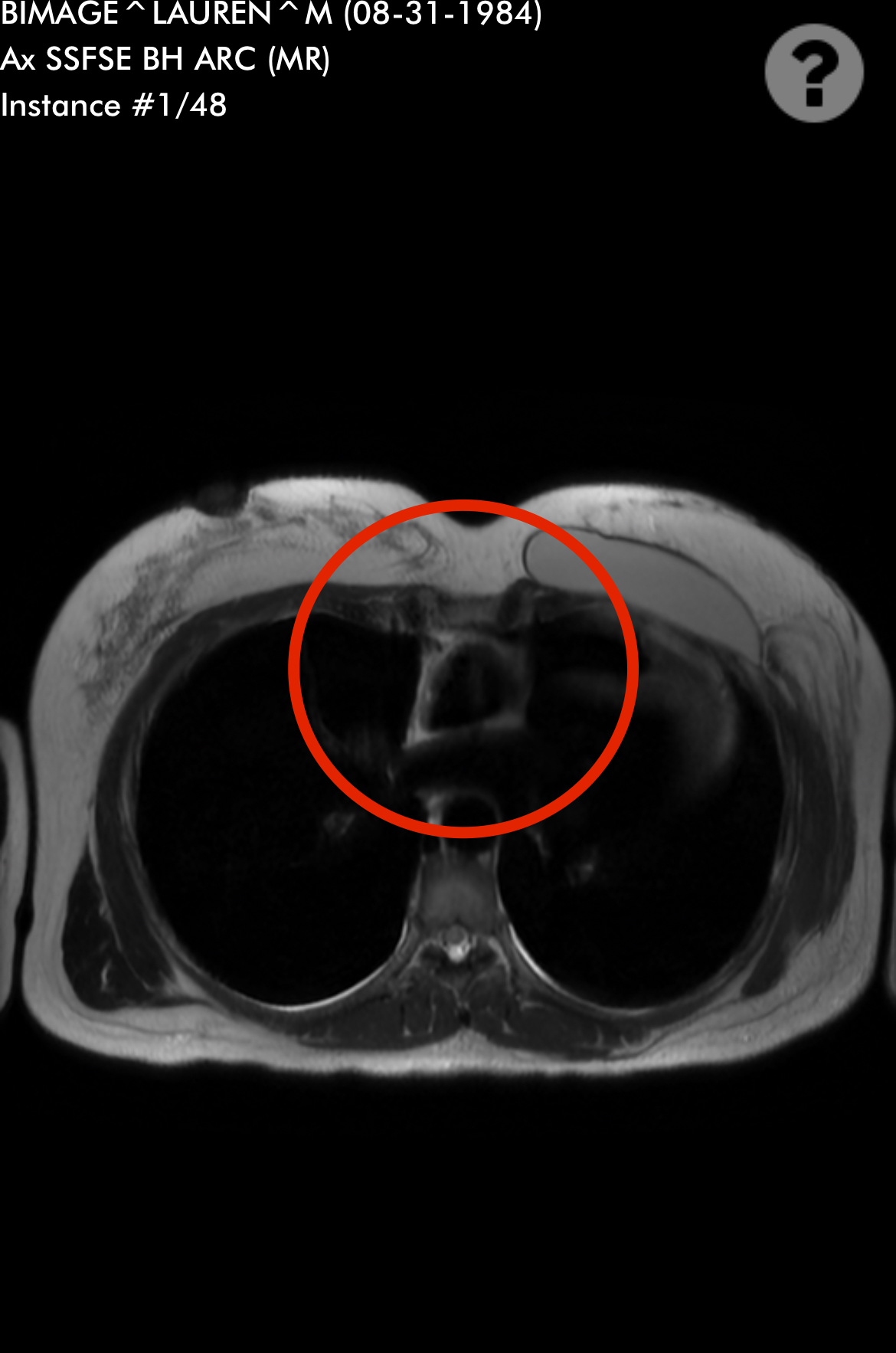

Natalie, who hails from Atlanta, GA, was diagnosed with stage 4 non-small cell lung cancer in June 2020. Her diagnosis followed a challenging 6-month period of inconclusive tests and misdiagnoses due to her age and non-smoking status. Her doctors initially attributed her symptoms, primarily fatigue and a persistent cough, to less serious conditions such as allergies or asthma. Despite undergoing multiple diagnostic procedures, including x-rays, CT scans, biopsies, and PET scans, Natalie only received her cancer diagnosis after one of her lungs collapsed during a biopsy.

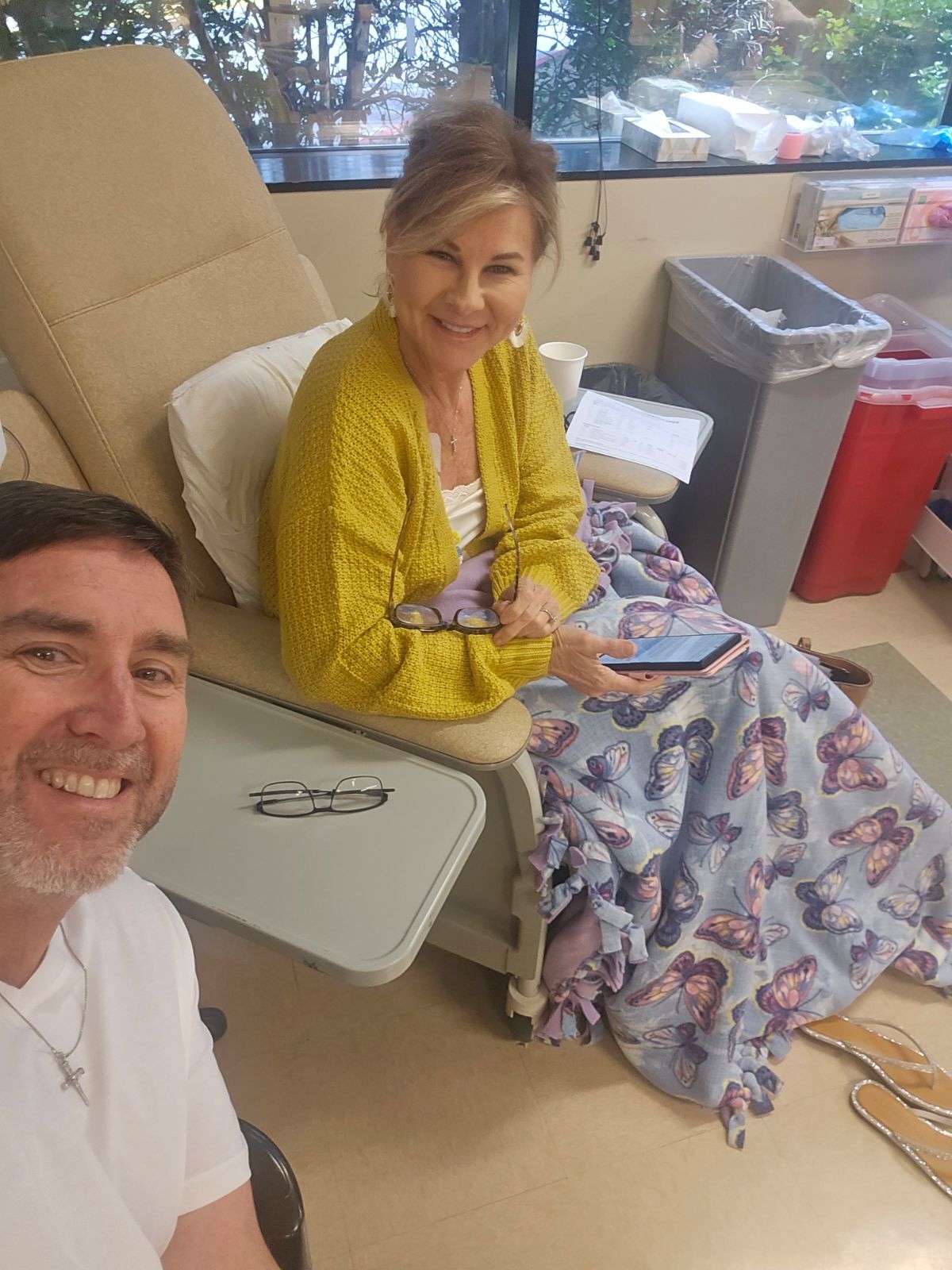

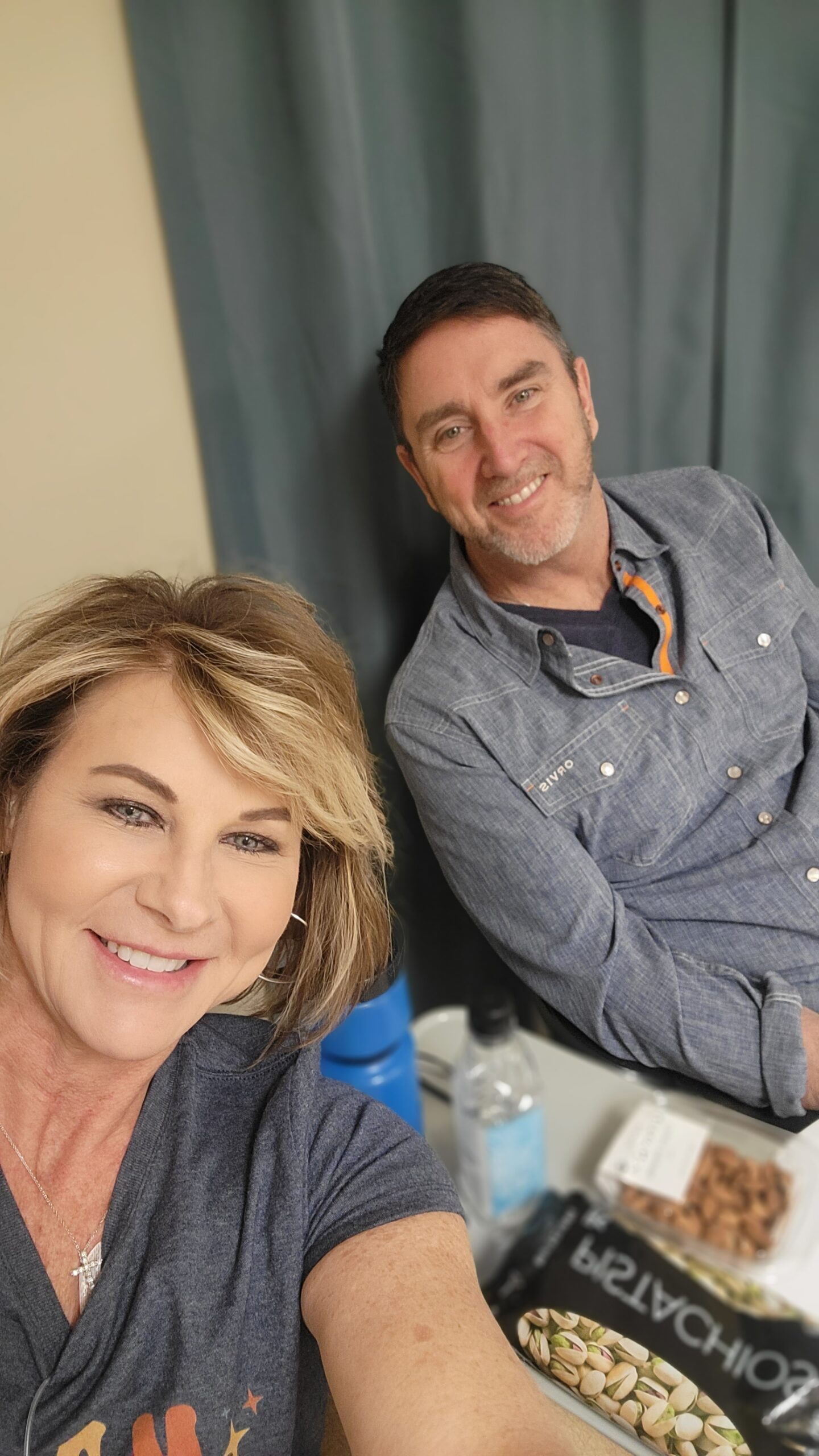

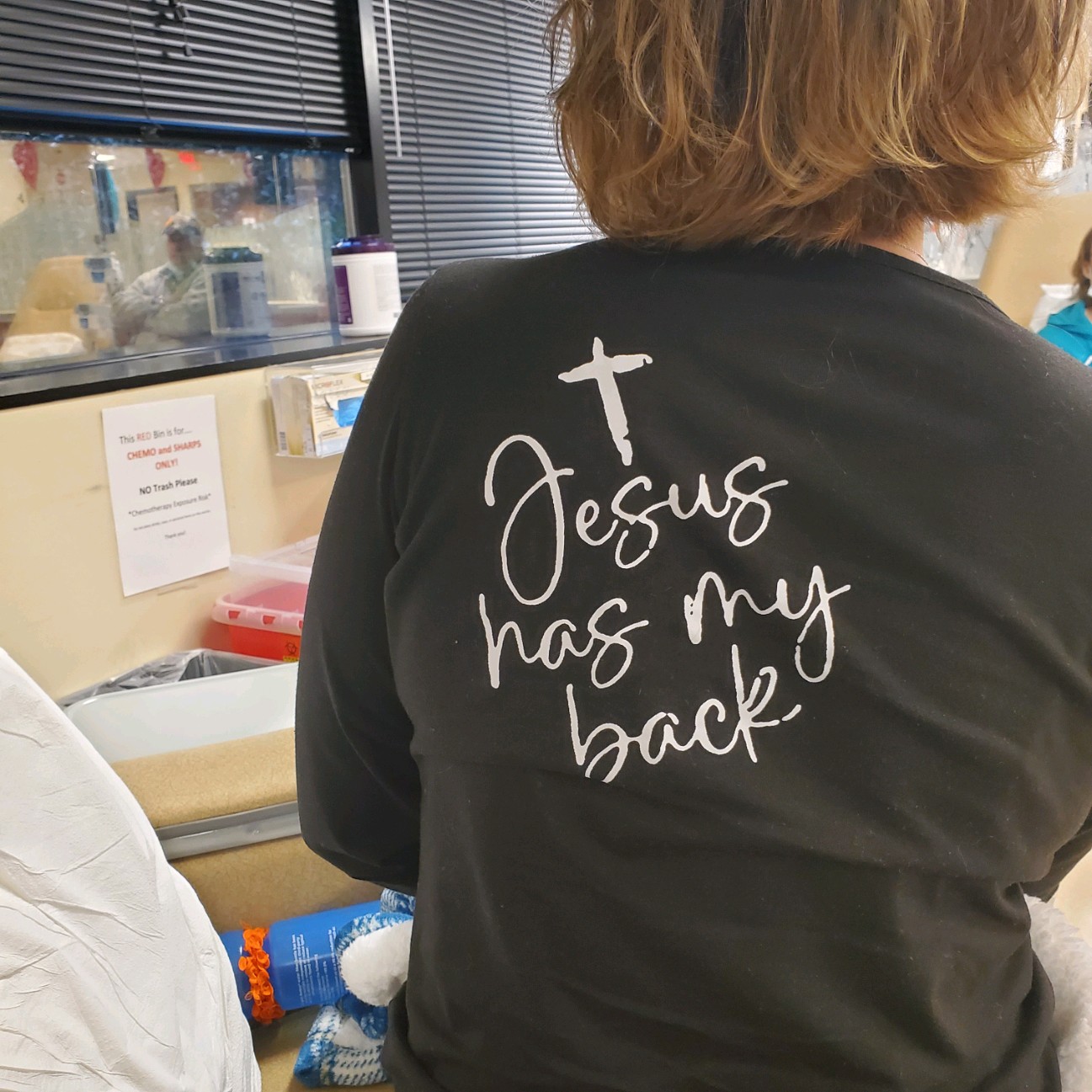

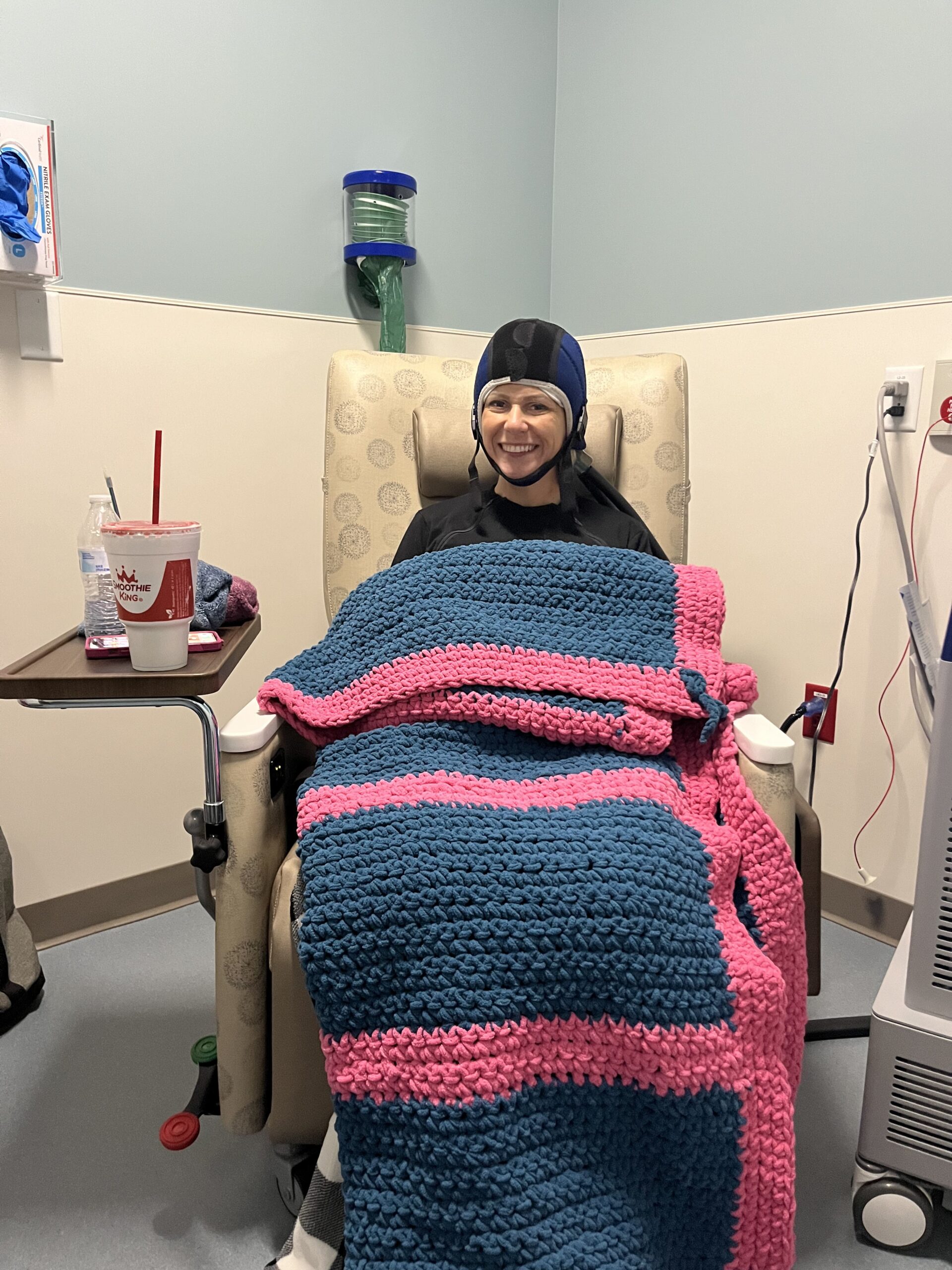

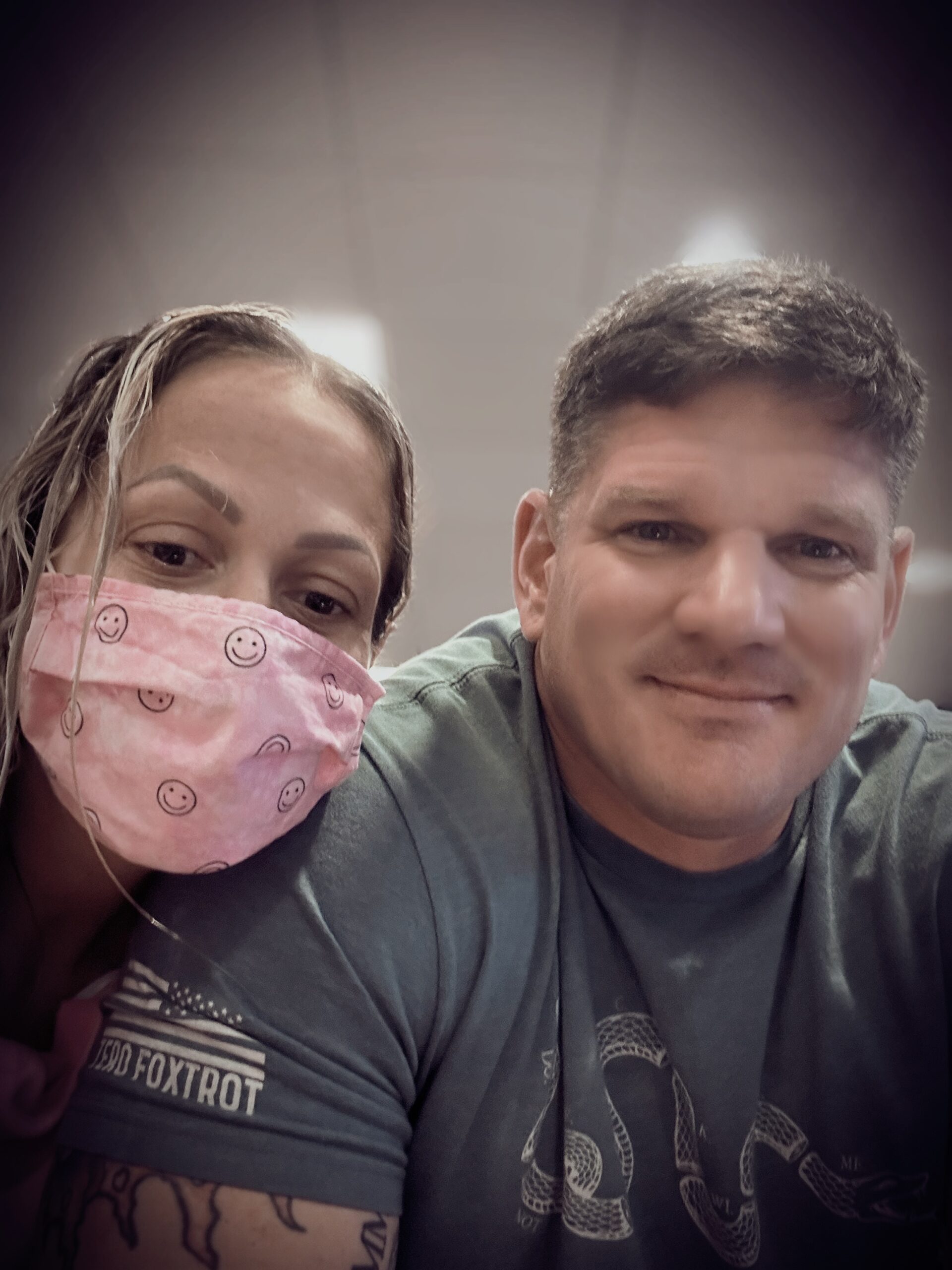

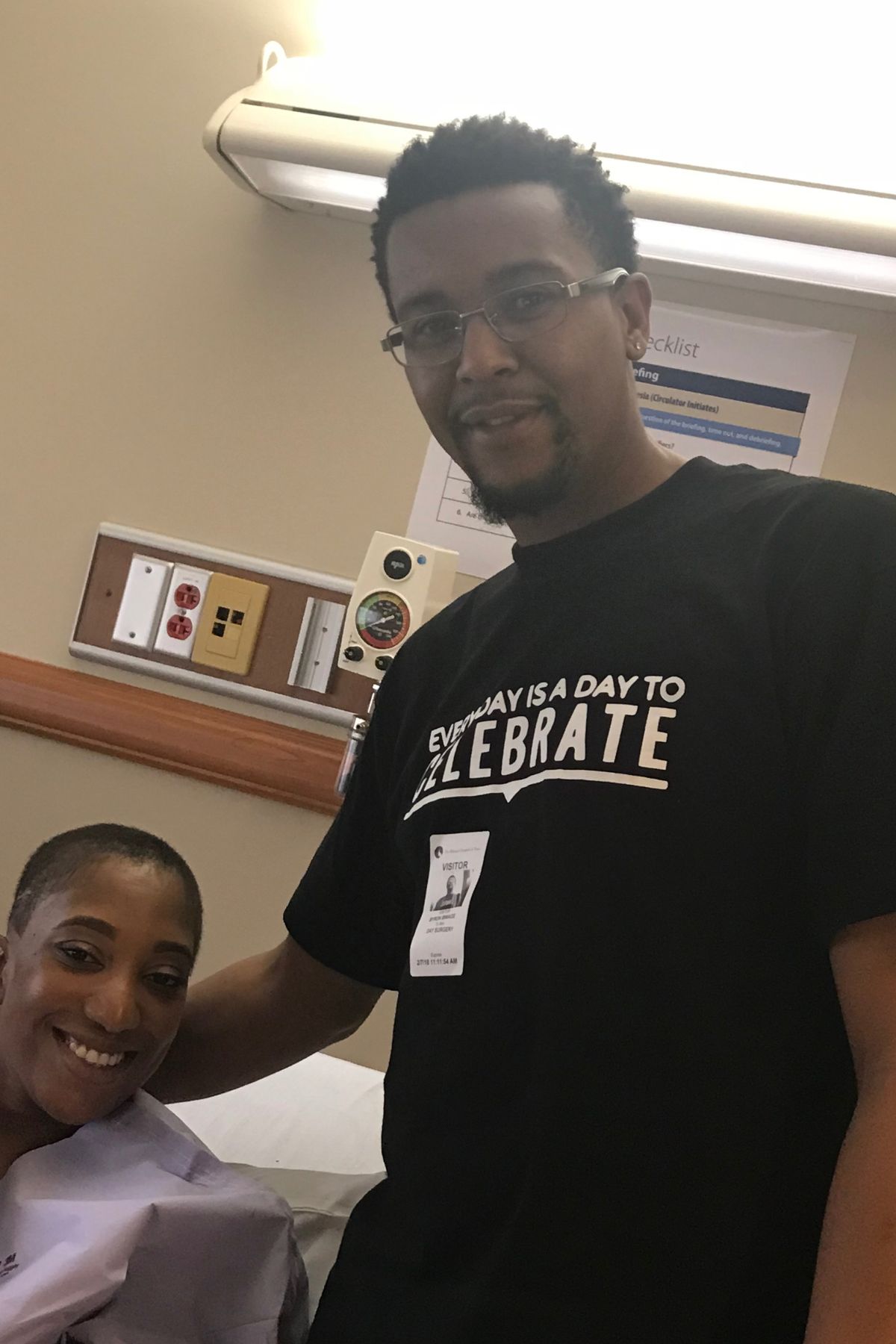

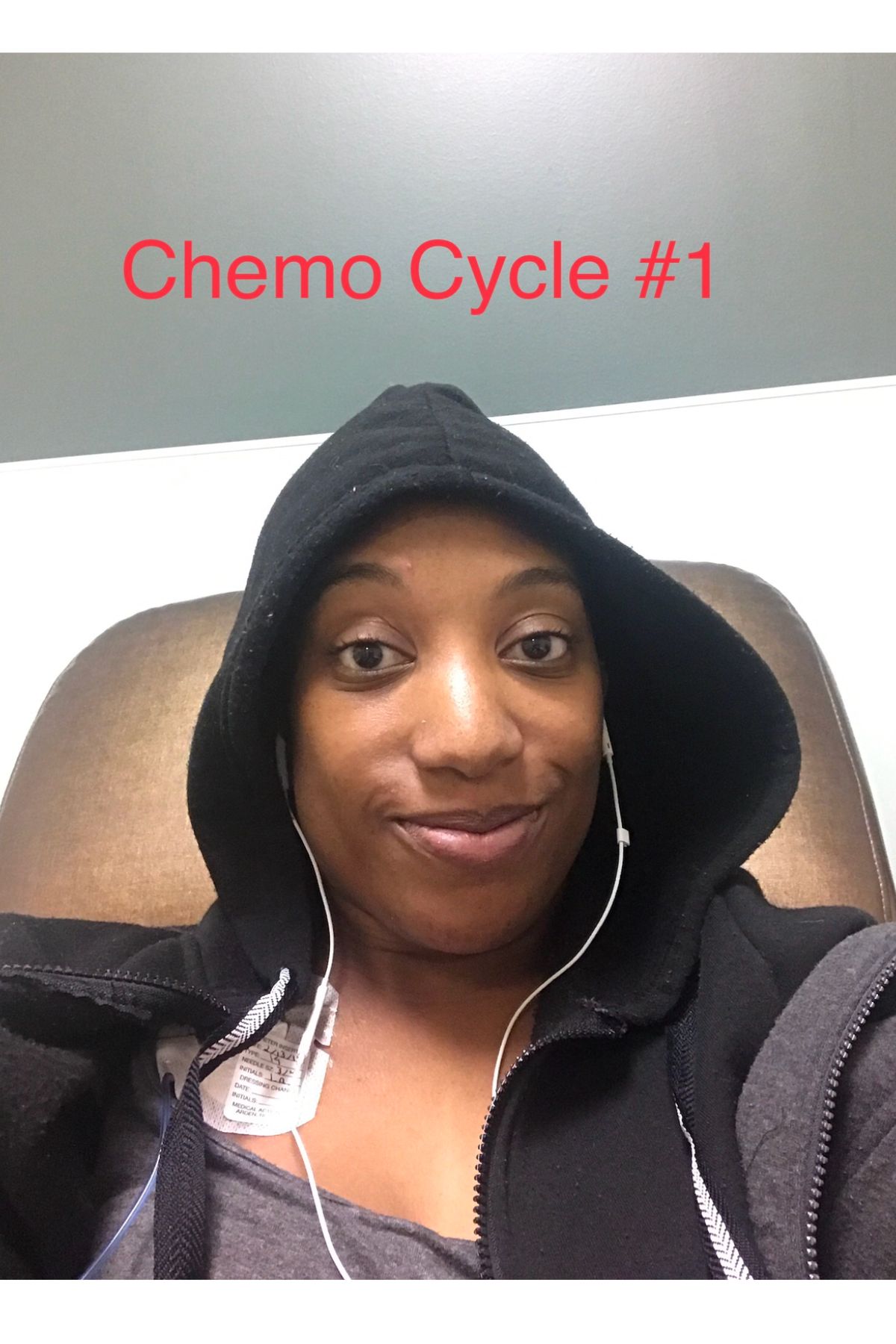

Natalie was overwhelmed by the stage 4 diagnosis, associating the prognosis with a death sentence. Her cancer had already spread to both lungs and her lymph nodes, and her oncologist confirmed that there was no definitive cure. Natalie immediately began chemotherapy and immunotherapy treatments. While she managed the physical side effects, particularly severe fatigue, she continued working throughout her treatment, with few people aware of her diagnosis.

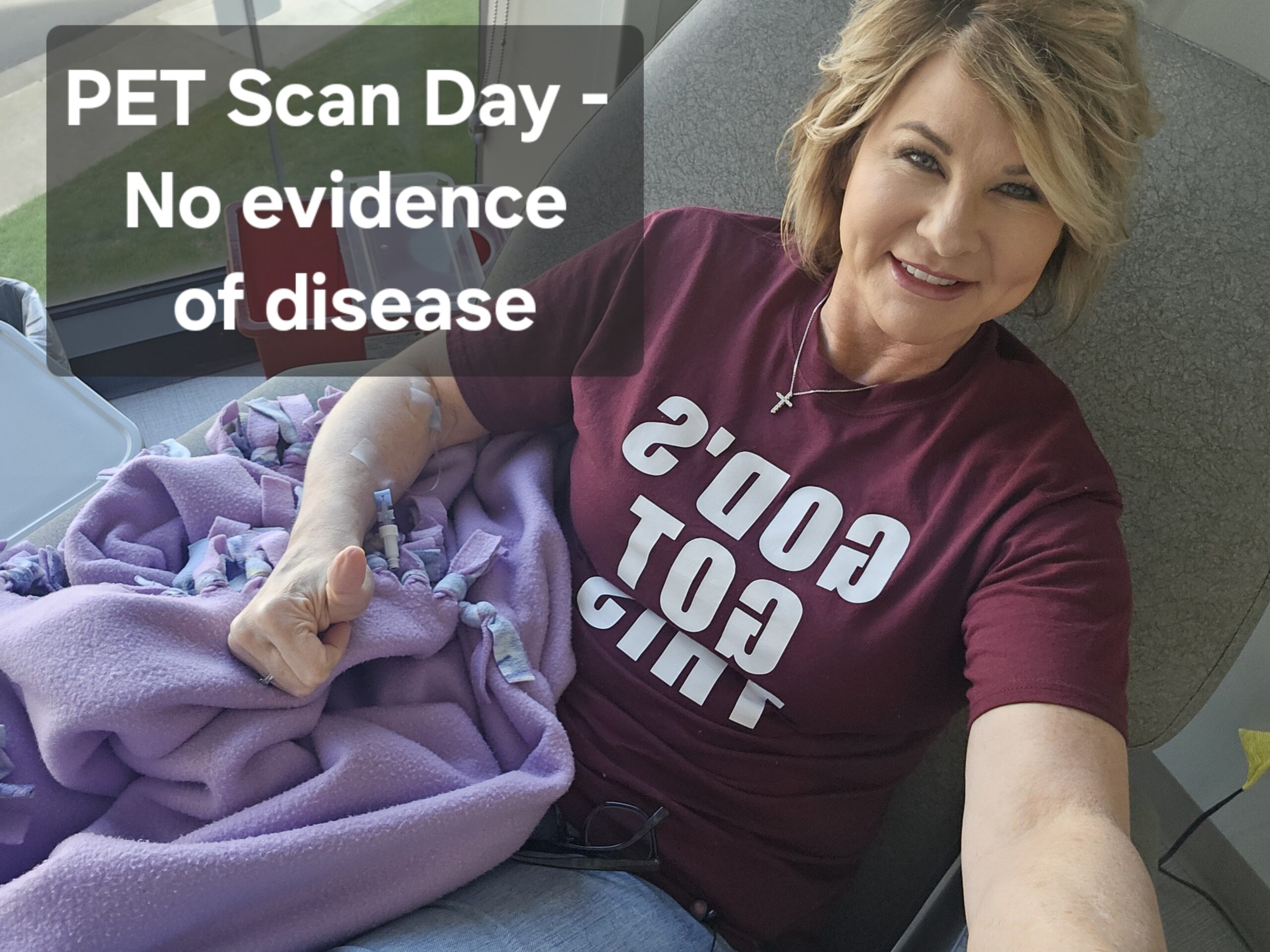

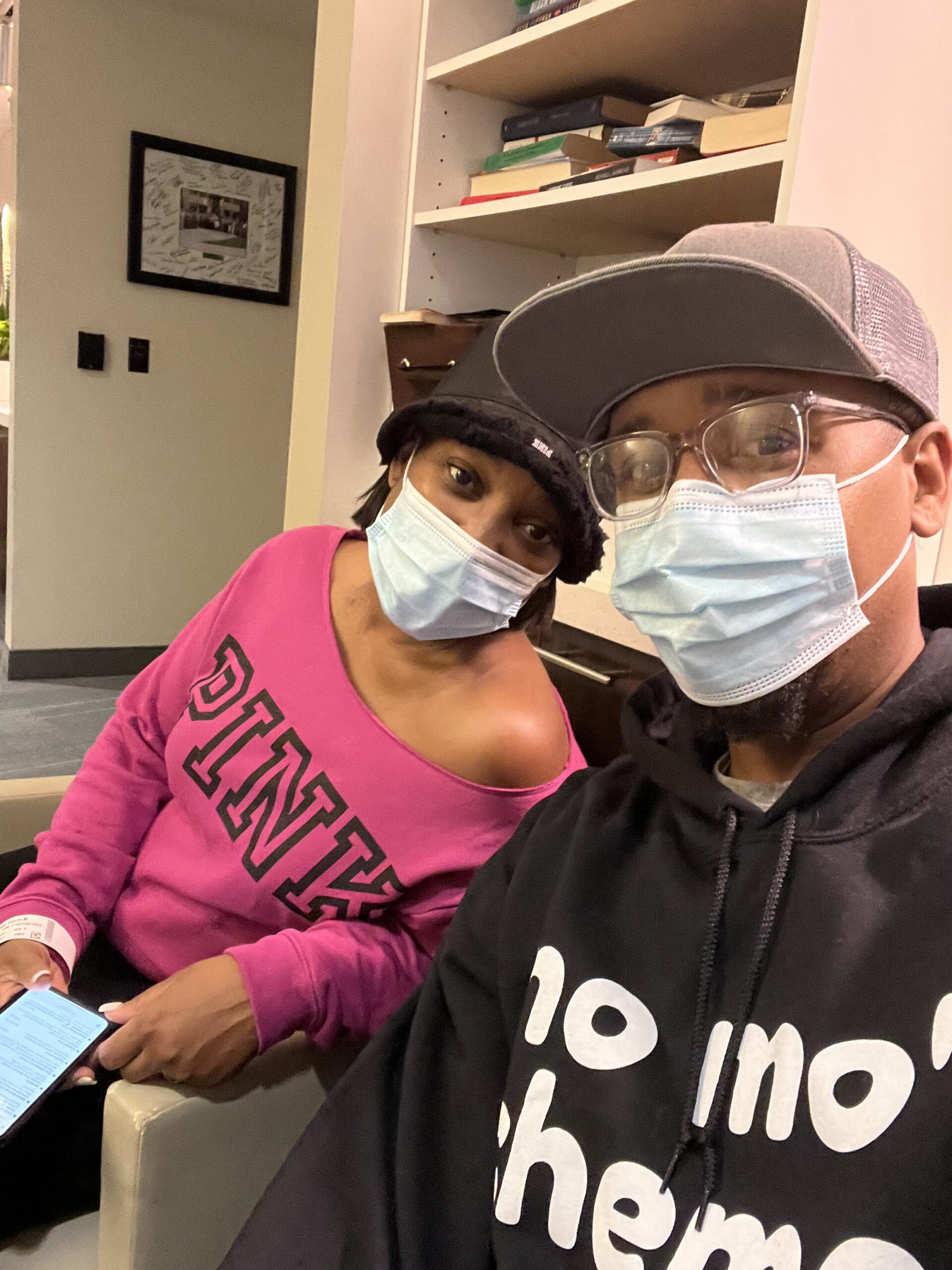

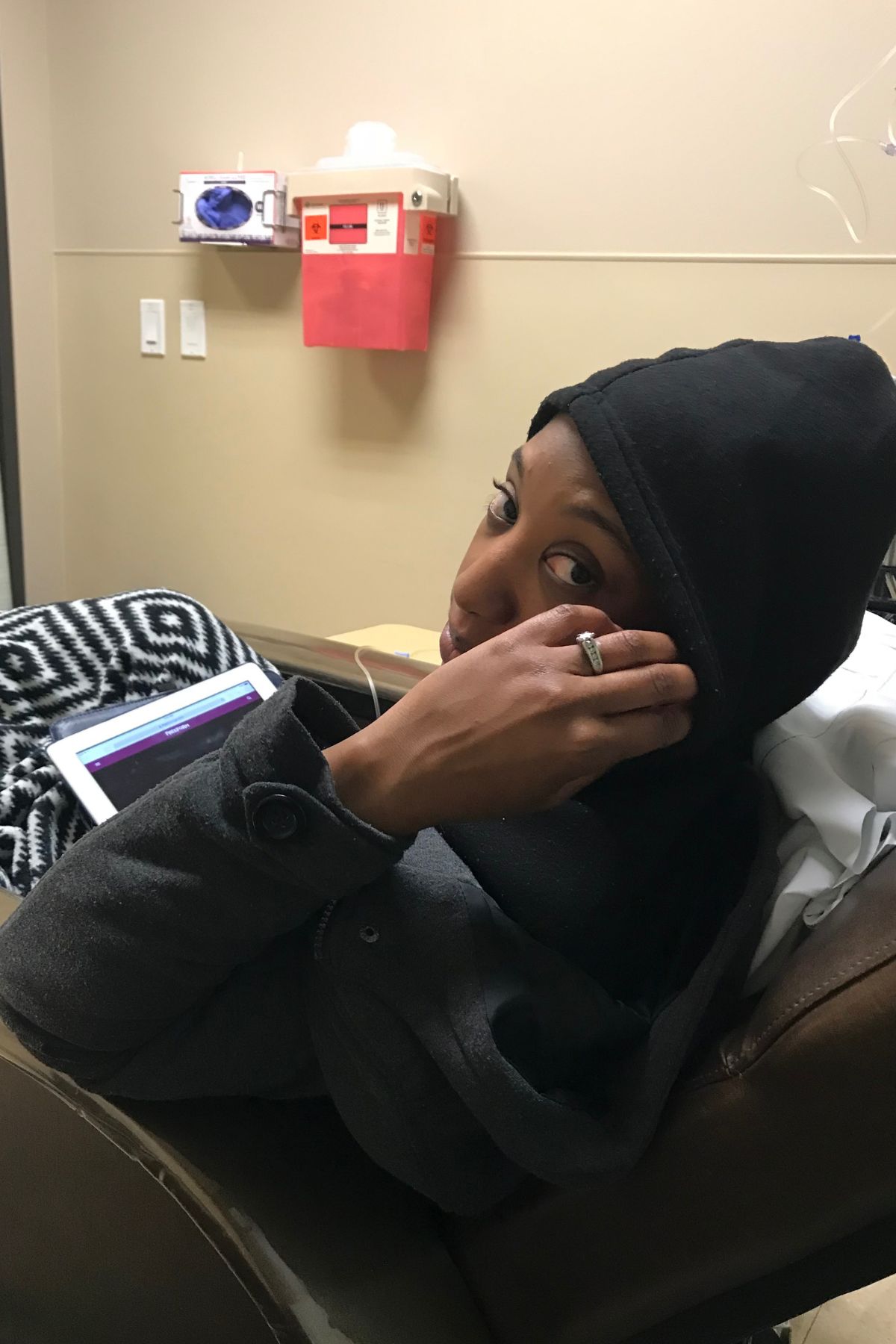

Over the course of 4 years, Natalie underwent 2 clinical trials after her cancer progressed, neither of which were successful. The first trial, at Emory Hospital, left her feeling worse than she did on chemotherapy and required multiple hospital visits. The second trial, in Nashville, produced no significant side effects. After these trials failed, she returned to chemotherapy, which has stabilized her cancer’s growth for now.

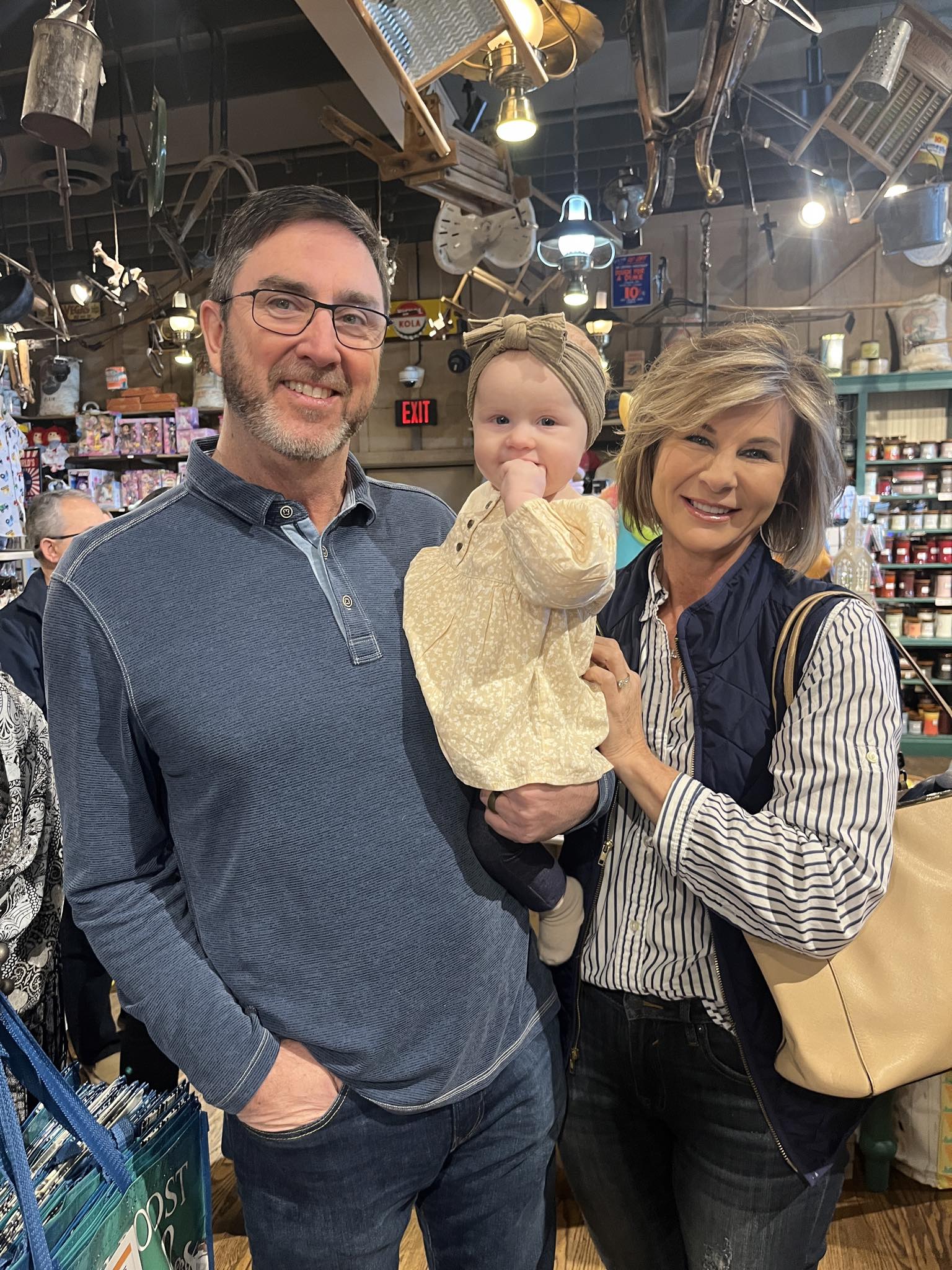

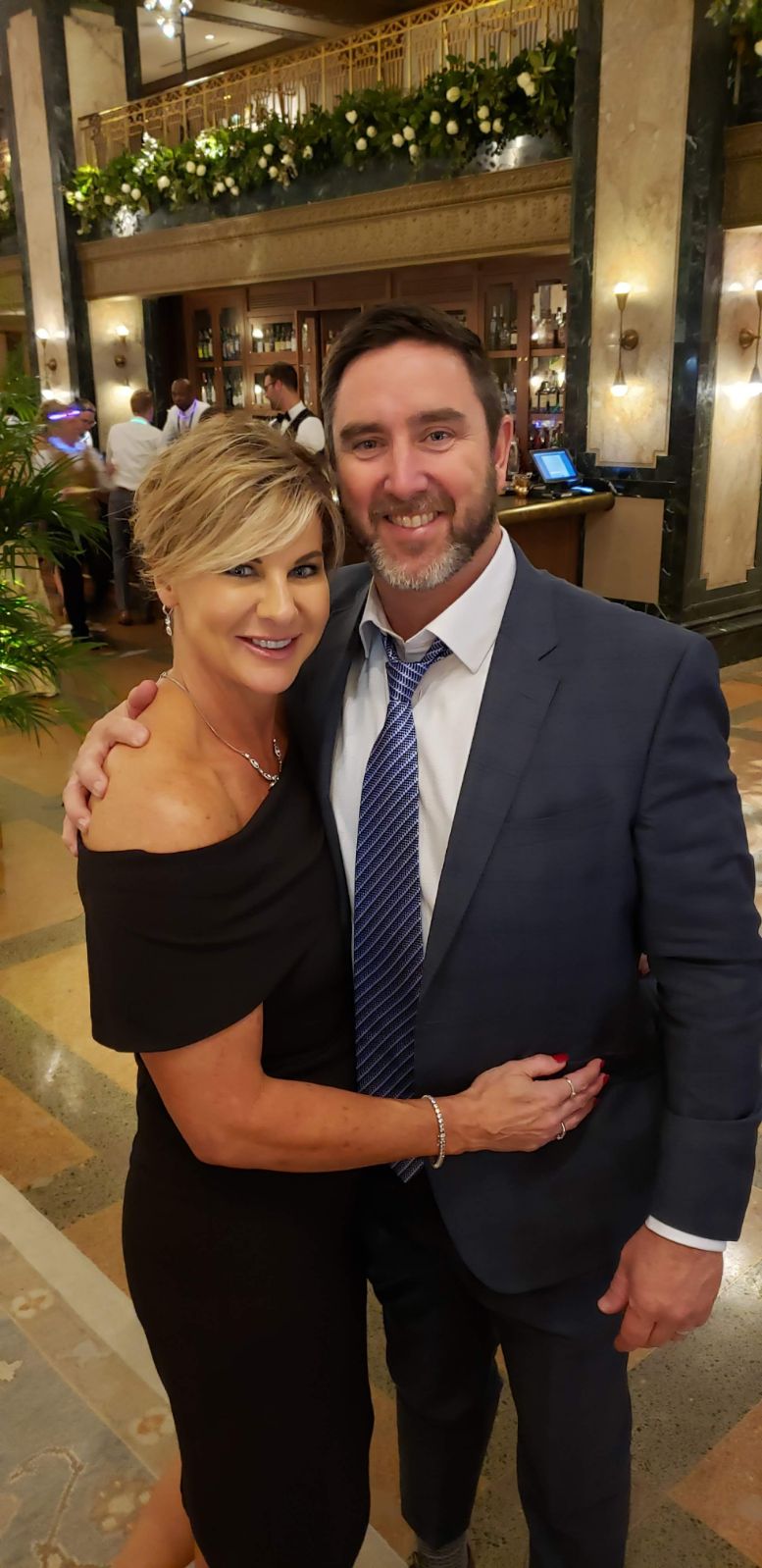

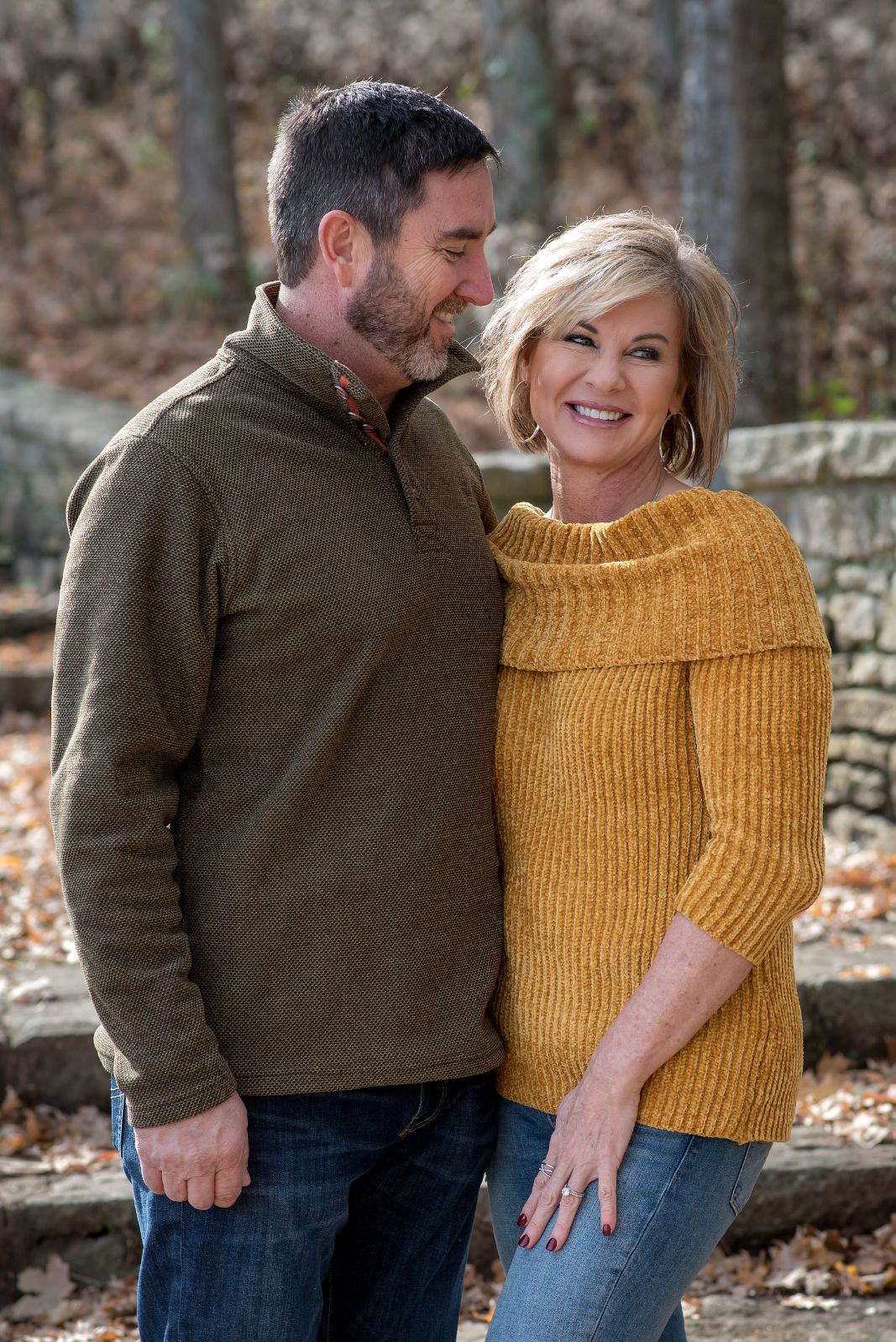

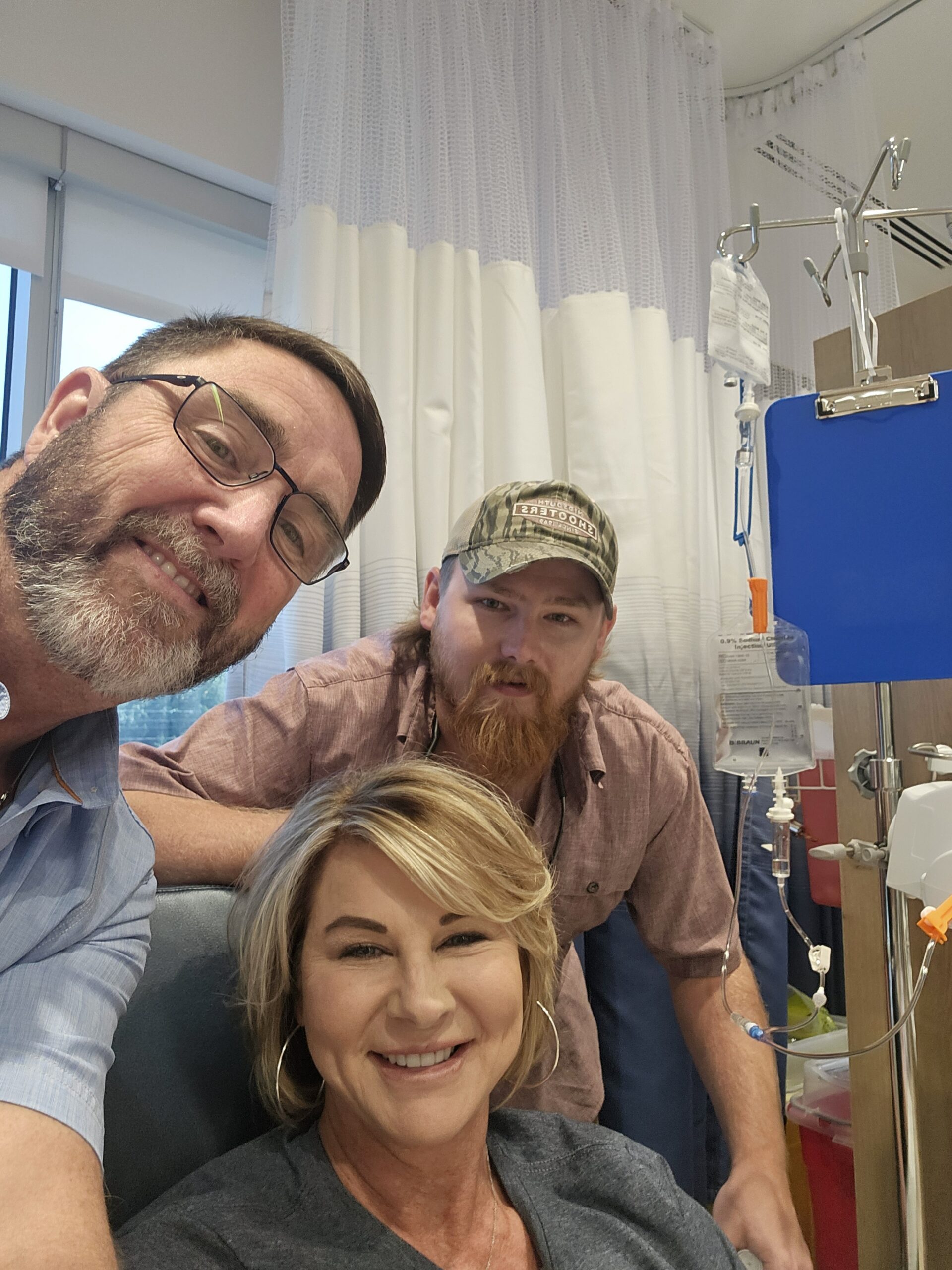

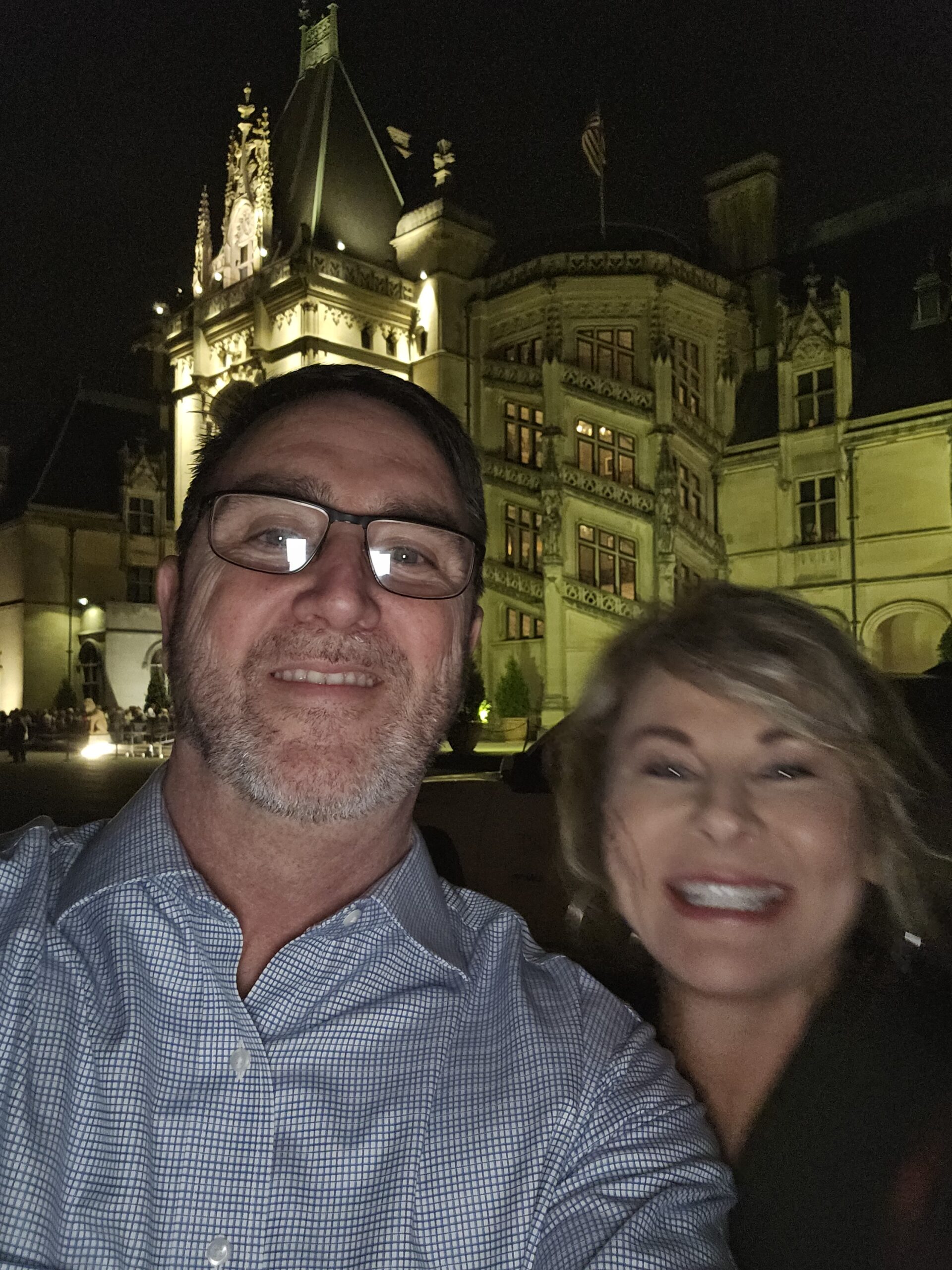

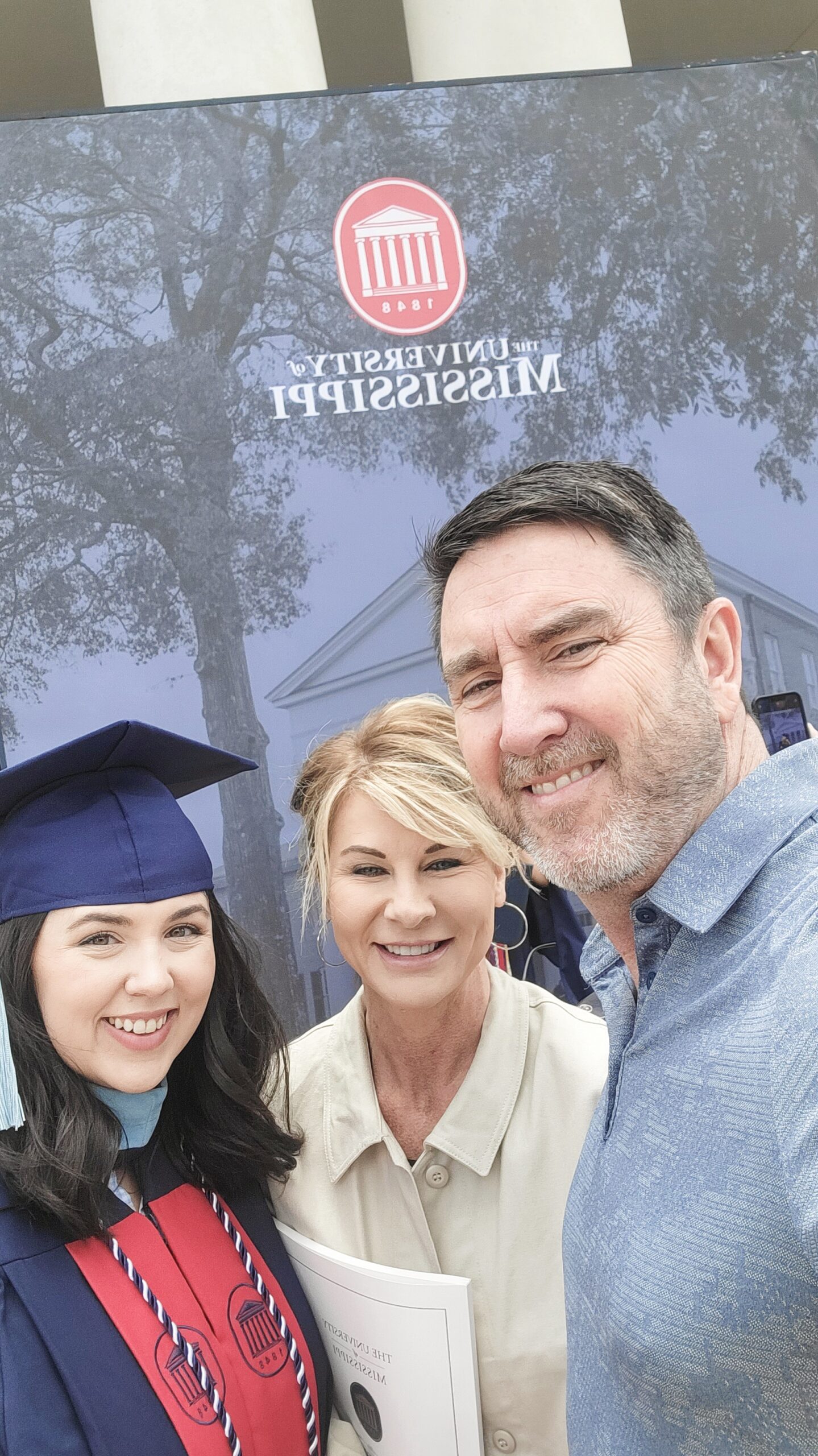

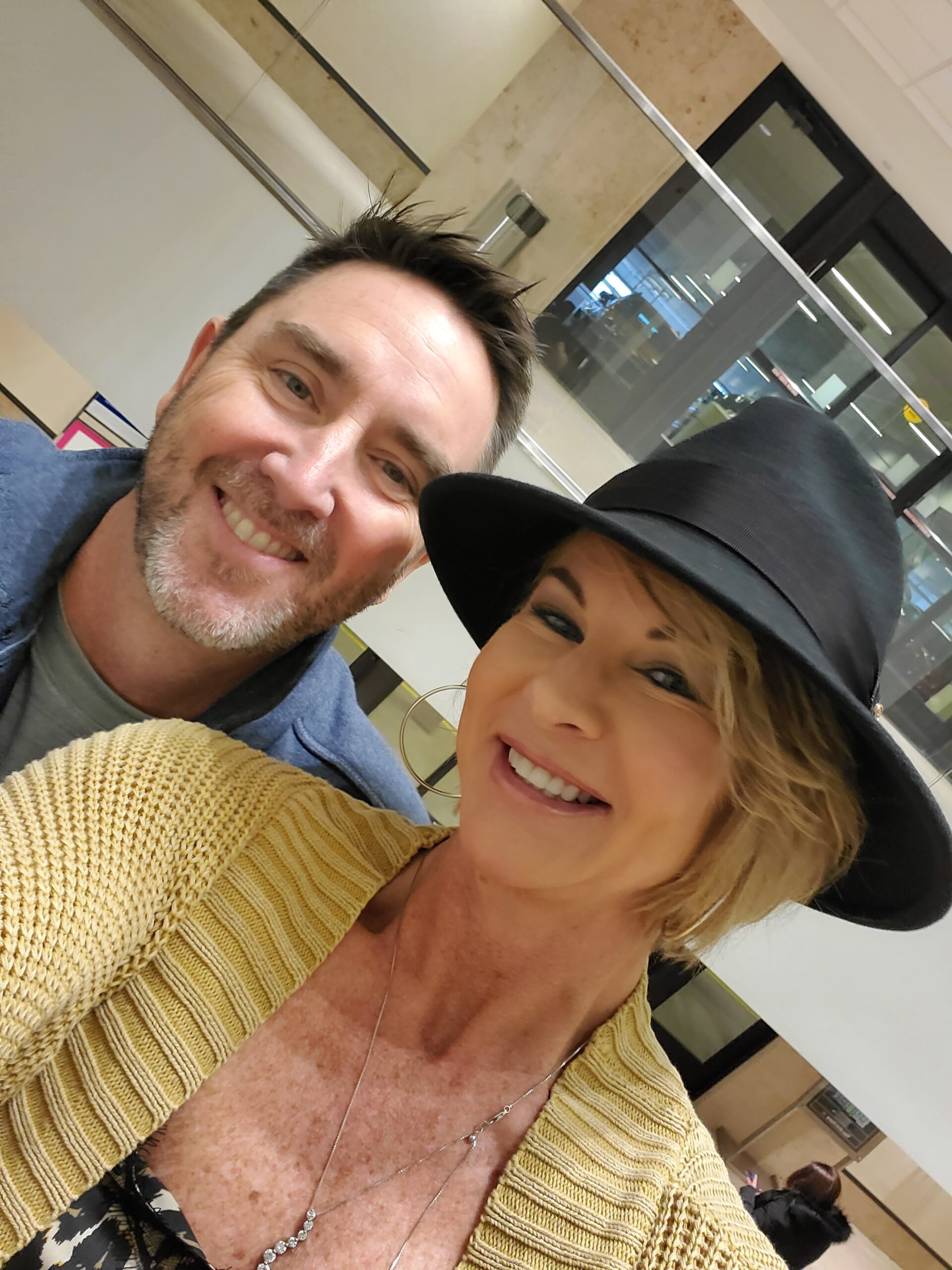

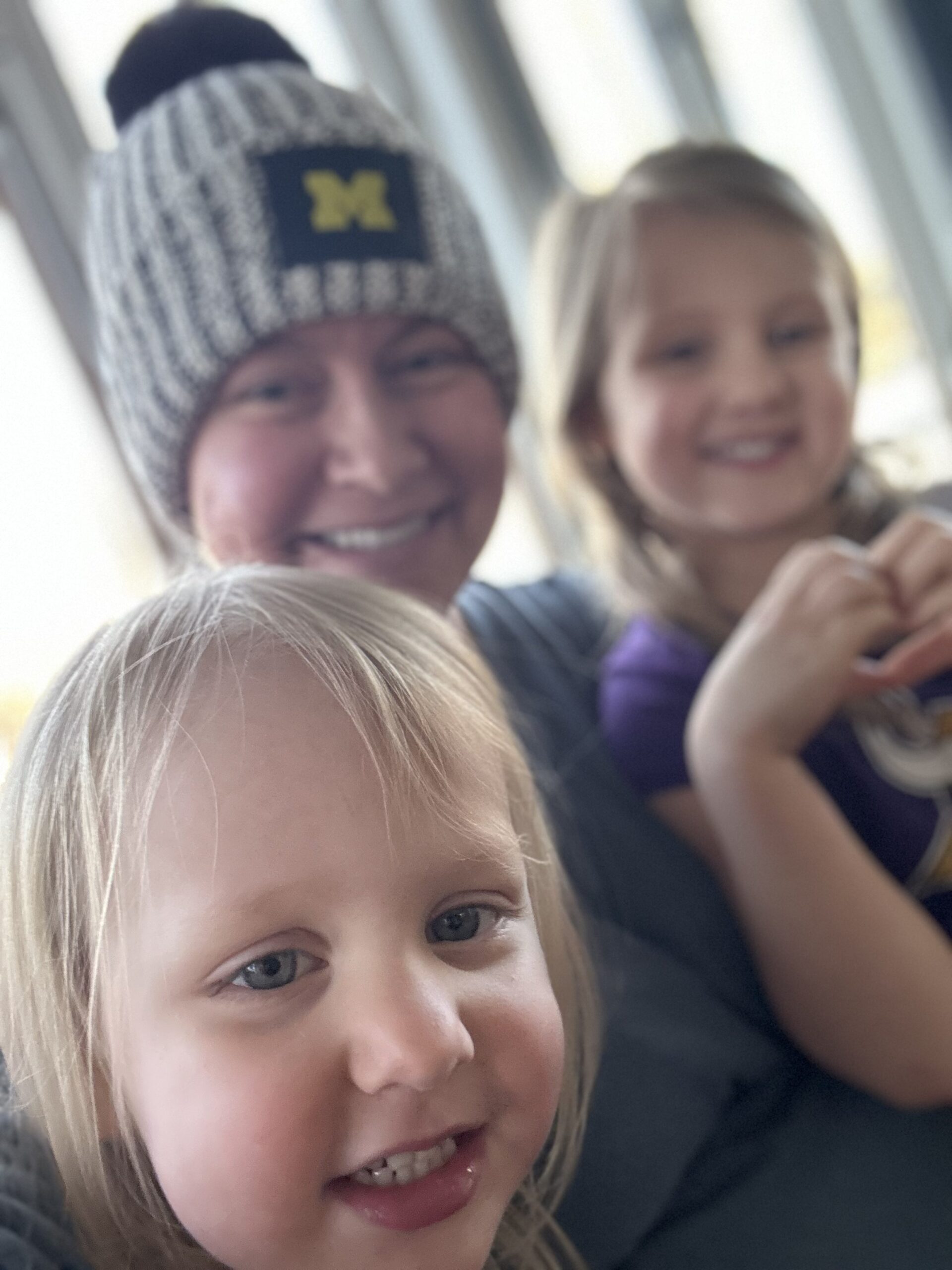

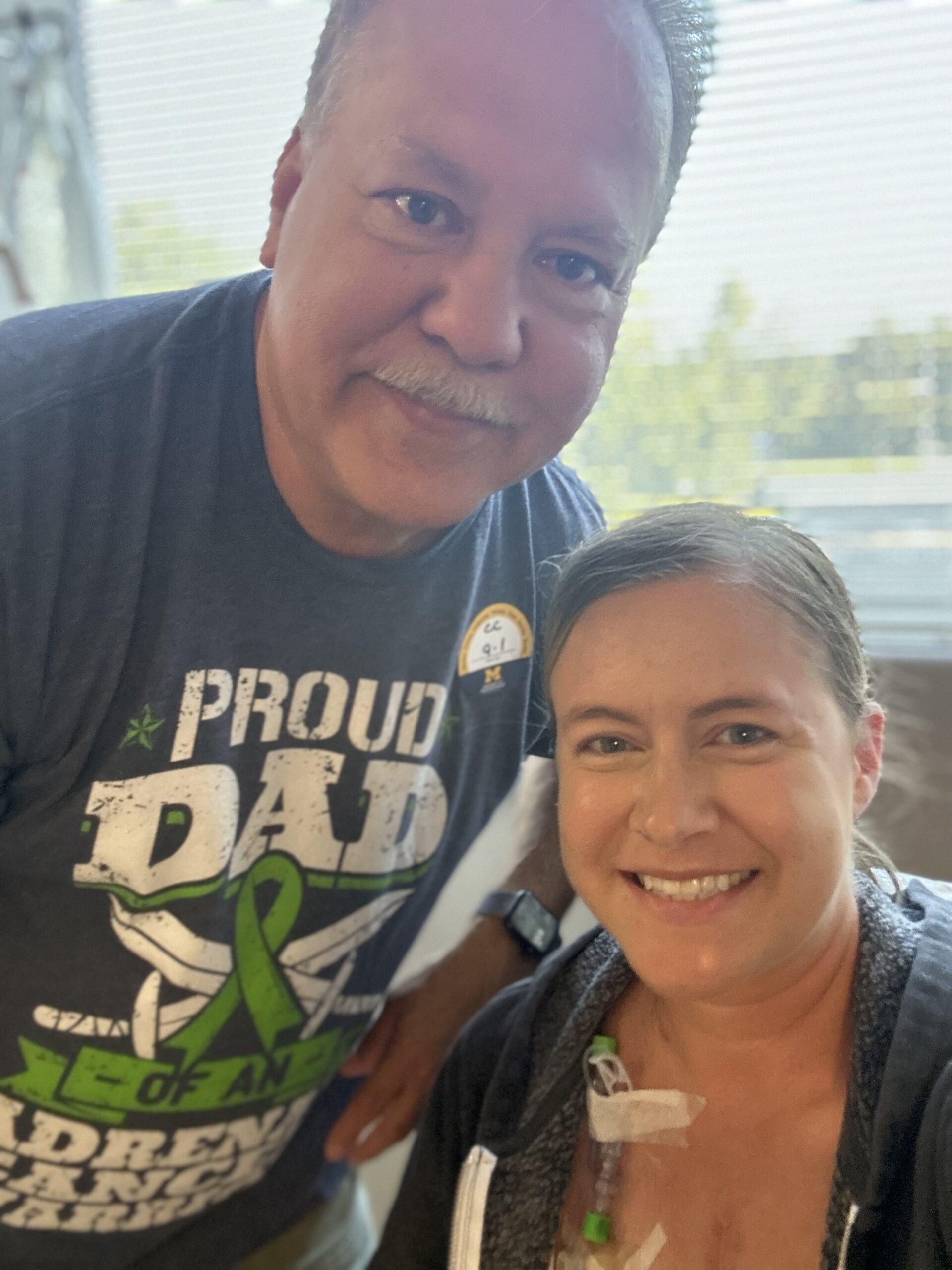

Beyond the physical challenges, Natalie has also struggled with the mental toll of her stage 4 non-small cell lung cancer. Therapy, her husband’s unwavering support, and her close-knit group of friends and family have been essential to her well-being. She acknowledges that at times she considered giving up treatment due to exhaustion but found renewed determination through the support of her loved ones and her desire to live and experience more of life.

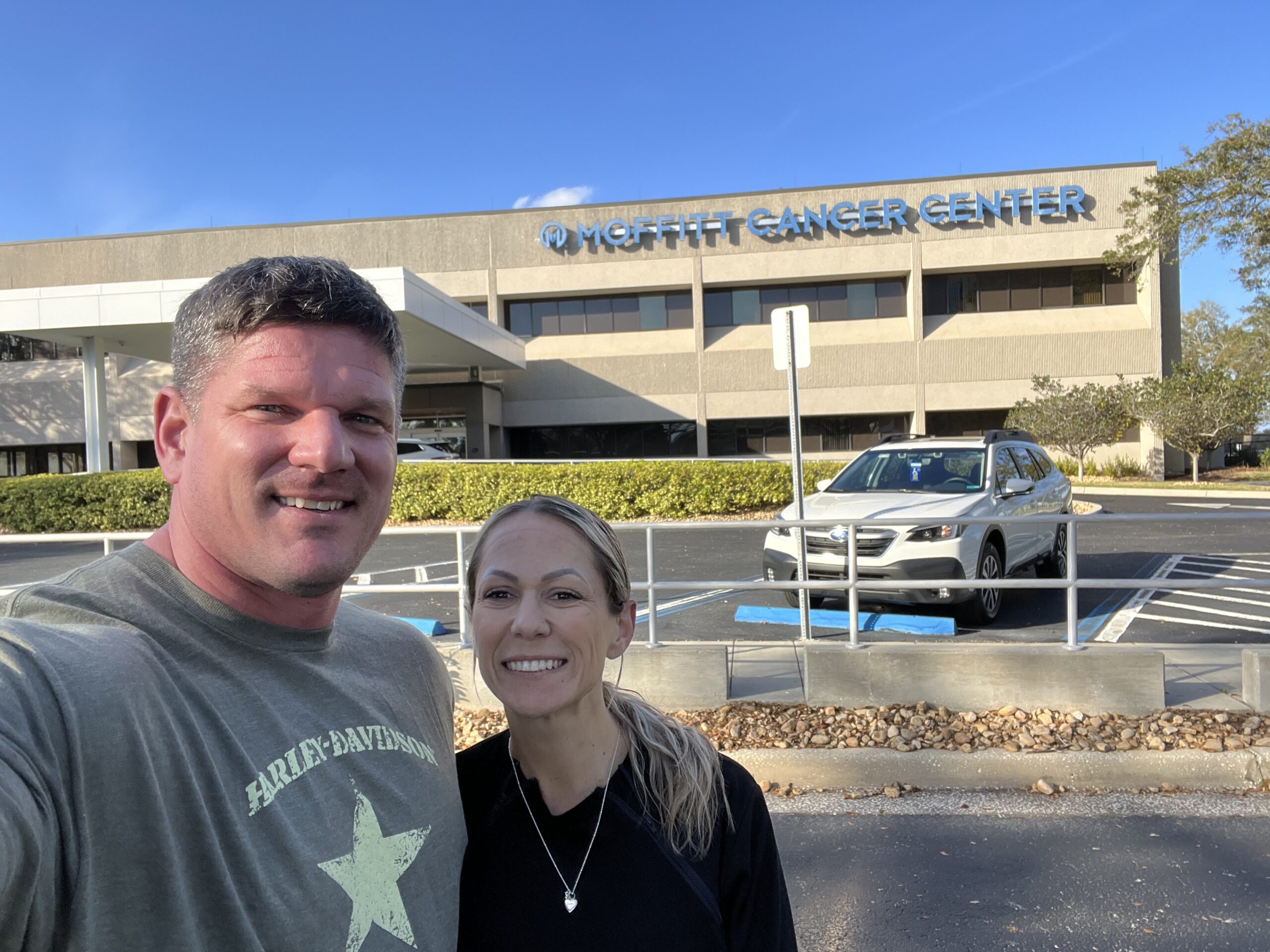

Recently, Natalie’s pulmonologist informed her that she might be a candidate for a double lung transplant, a procedure that could potentially offer her a cure. She is in the early stages of the process and hopes that her cancer remains confined to her lungs so she can be placed on the donor list.

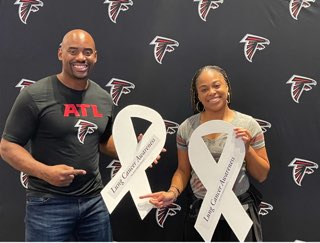

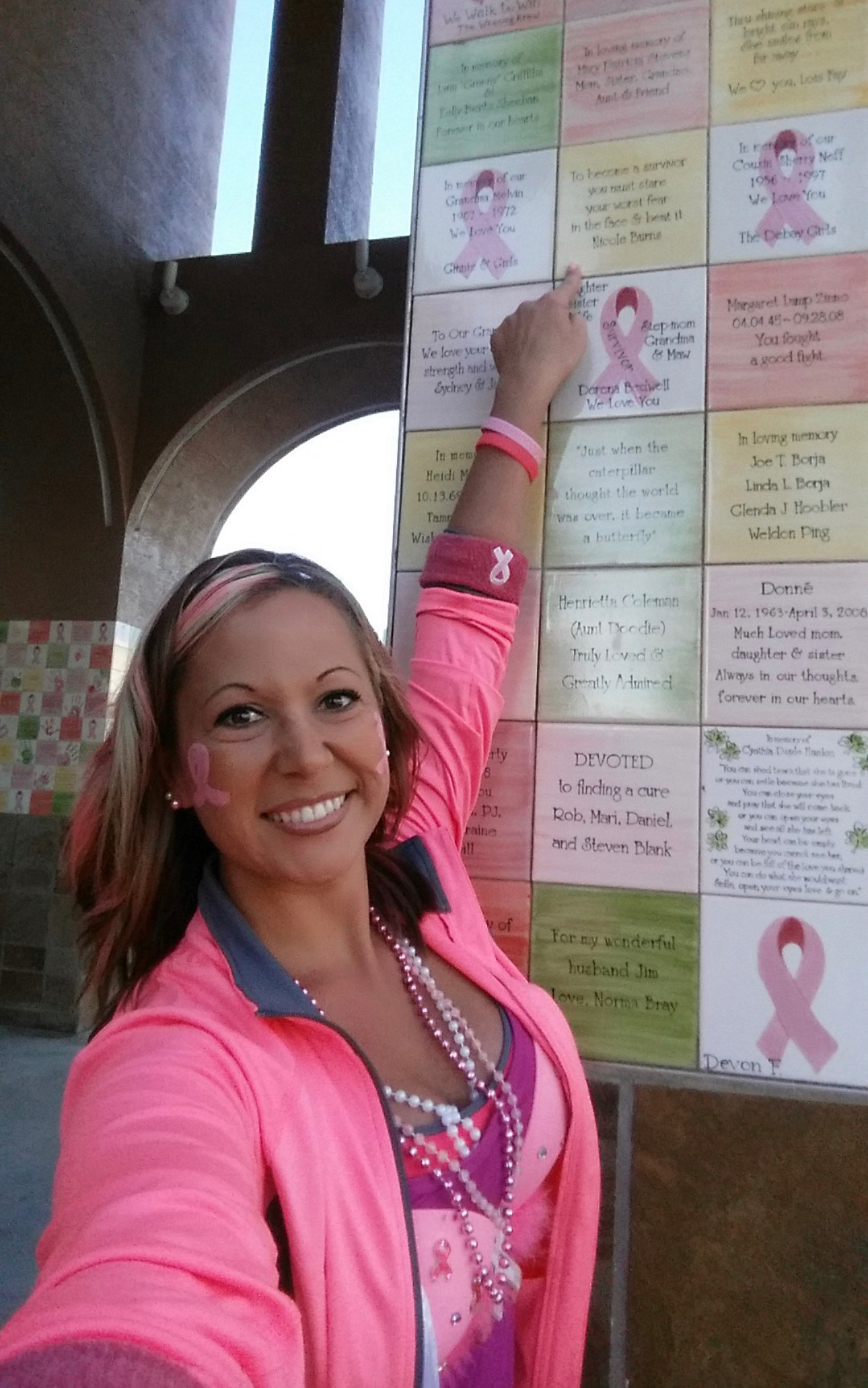

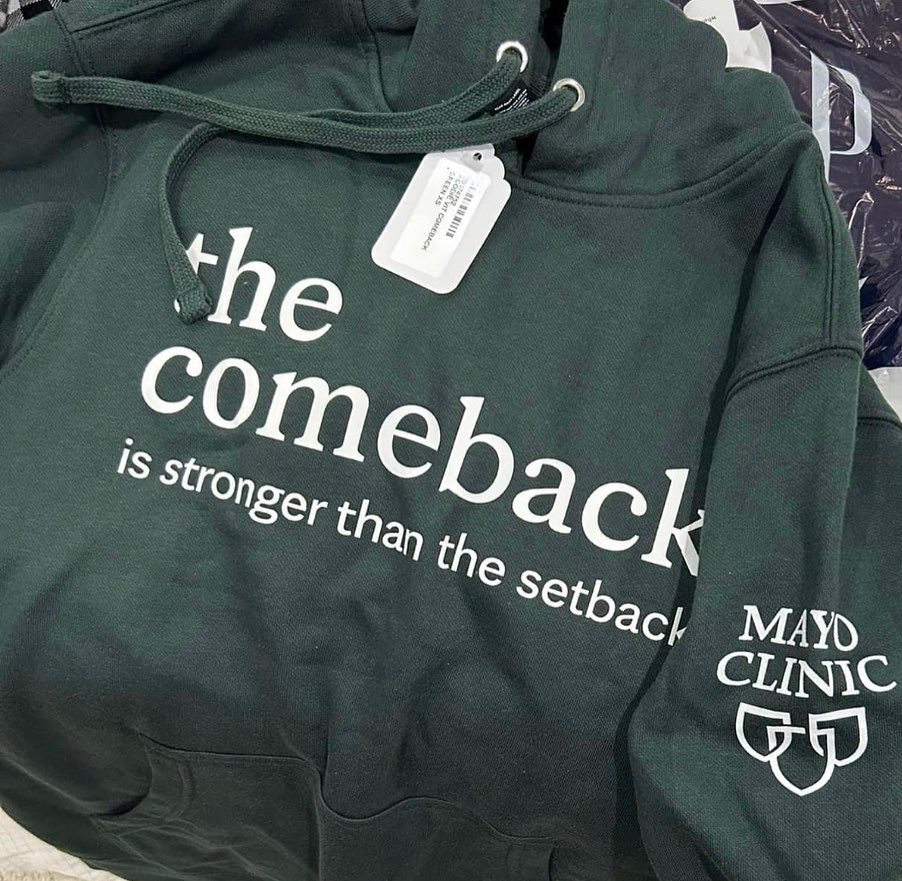

Natalie emphasizes the importance of advocating for lung cancer awareness, noting that anyone with lungs is at risk, not just smokers. She encourages others facing similar challenges to try to keep going, acknowledging the mental and physical difficulties of battling cancer. Her message is one of resilience and the importance of not giving up, even when the path is painful and difficult.

- Name:

- Natalie B.

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 33

- Diagnosis:

- Non-small cell lung cancer

- Staging:

- Stage 4

- Symptoms:

- Persistent cough

- Fatigue

- Treatments:

- Chemotherapy

- Immunotherapy

- Clinical trials

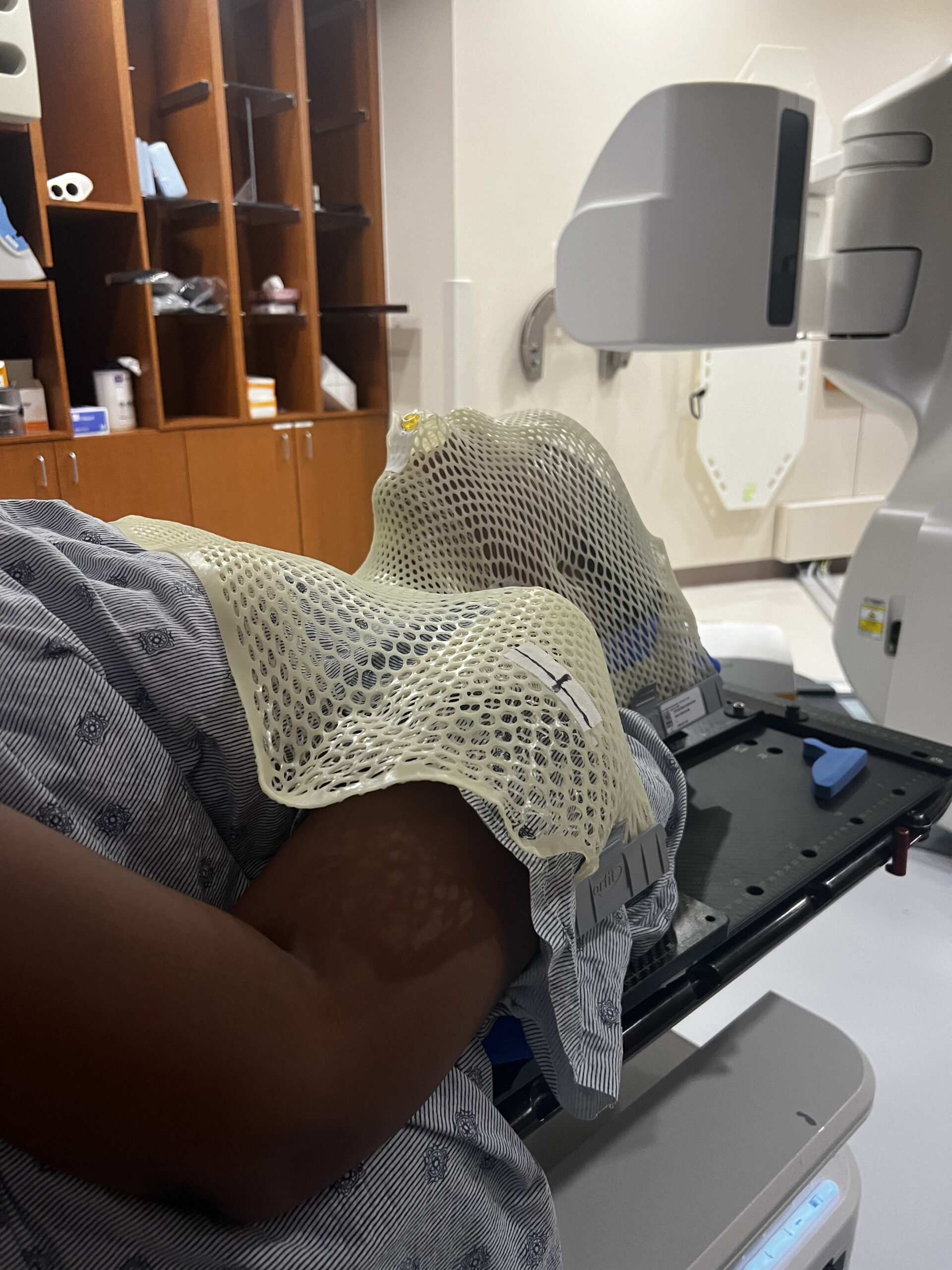

- Radiation (palliative)

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

Inspired by Natalie's story?

Share your story, too!

Related Cancer Stories

More Lung Cancer Stories

No post found

More Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Stories

No post found