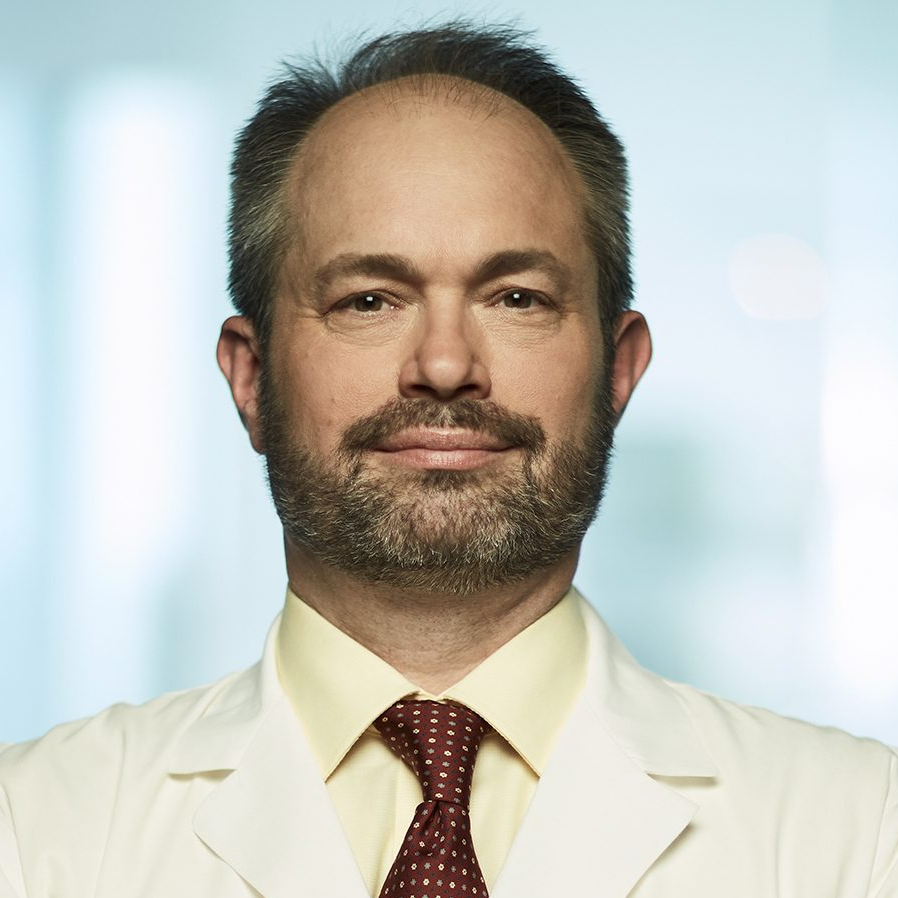

Dr. William Wierda

Medical Director of the Department of Leukemia and CLL Center Section Chief at MD Anderson

Published January 2022

- What is the ASH conference?

- Large CLL Study on MRD

- What is the ASH conference?

- Different classes of CLL drugs

- Most important considerations for CLL patients

- Minimal residual disease (MRD)

- Progression-free survival (PFS)

- When is a patient considered "cured?"

- Patients with riskier prognostic indicators

- Promise of ibrutinib + venetoclax + chemotherapy

- What treatments should patients be watching for right now?

What is the ASH conference?

Dr. William Wierda: Most of ASH for us is getting the details of things that we know about. We hear about. We’re able to look.

Many of us are involved in the clinical trials so we know in real time what’s happening with the clinical trials. Some of us are on the safety and review committee for these large trials, so we do have an idea of what the presentations will be for ASH.

It’s more of getting the detail and hearing the discussion and what people are thinking about. That is what we get out of these, these meetings. There wasn’t really any abstract that was presented that was something that was completely a surprise or something completely new.

Large CLL Study on MRD

Details of the study

Dr. William Wierda: The CLL-13 trial from the German CLL study group – that is a large trial with four treatment arms. There were nearly 1,000 patients enrolled in that study. That was a trial that compared different arms of treatment from chemotherapy therapy-based treatment.

And then the other three arms were oral small molecule inhibitor based treatments: venetoclax-rituximab, venetoclax-obinutuzimab, and venetoclax-ibrutinib-obinutuzimab. That trial, they reported results for Minimal Residual Disease (MRD).

The poorest performer was, wait for this . . . chemotherapy.

Dr. William Wierda

And not surprisingly, the best response was seen among those patients who received venetoclax-ibrutinib-obinutuzimab. So all three drugs, although there is a bit more side effects and toxicities associated with it and the question is are there more?

But is the value of having more undetectable-MRD with three drugs and some more toxicity, better than two drugs like venetoclax-obinutuzimab, which was the next highest undetectable-MRD rate, was for venetoclax-obinutuzamab. That’s a standard treatment. That trial demonstrated that rituximab plus venetoclax was not as good as venetoclax plus obinutuzumab and the poorest performer was, wait for this, chemotherapy.

Still need follow-up

Dr. William Wierda: So I think that the trial is an important trial. We didn’t get any information, because it’s very early, about how long the remissions are lasting or what the long term follow up is with that treatment that’s going to take a couple more years. We did get data for minimal residual disease and that predicts for outcomes, remission, duration, etc. But we like to see both MRD and the follow-up data.

What is the ASH conference?

Michele Nadeem-Baker: And Dr. Wierda, what in your opinion, what were the biggest takeaways from this year’s ASH, which is the biggest conference of the year for hematologists from around the world?

Dr. William Wierda: Right. So as you say, this is our big meeting. This is where most of us present the new data. There are a couple other meetings that happen midyear around June, and we do occasionally get updated data from those meetings.

But this is our big meeting and discussion, and revealing of the detailed data around clinical trials. There were several clinical trials that were reported on. A couple of them were new reports that we hadn’t heard before, and several of them were follow up reports.

Different classes of CLL drugs

- BCL-2 inhibitors

- BTK inhibitors

Small molecule inhibitors

Dr. William Wierda: Overall what they showed was that chemotherapy outcomes or outcomes with chemotherapy were inferior to outcomes for treatment with small molecule inhibitors, whether we’re talking about venetoclax-based therapy or BCL-2 inhibitor-based therapy, or we’re talking about BTK-inhibitor based therapy or drugs

Michele Nadeem-Baker: Could you explain what an example of BTK-inhibitors and of BCL-2s for our audience to understand?

BCL-2 inhibitors

Dr. William Wierda: So the small molecule inhibitors that we have are oral agents, and there are three categories right now that we have of drugs that fall into the small molecule inhibitor category: BCL-2 inhibitors, we have one. There are several that are in clinical trial.

The one that we have is called venetoclax. Very potent at eliminating disease, very potent at getting deep remissions. It’s the type of treatment that we give with the expectation of giving it for a set period of time and then stopping treatment once patients are in remission.

Michele Nadeem-Baker: Defined treatment is a defined time as opposed to indefinite.

Dr. William Wierda: It’s a defined time – one year as a first treatment and two years as the second treatment, according to the current standard treatments that we give.

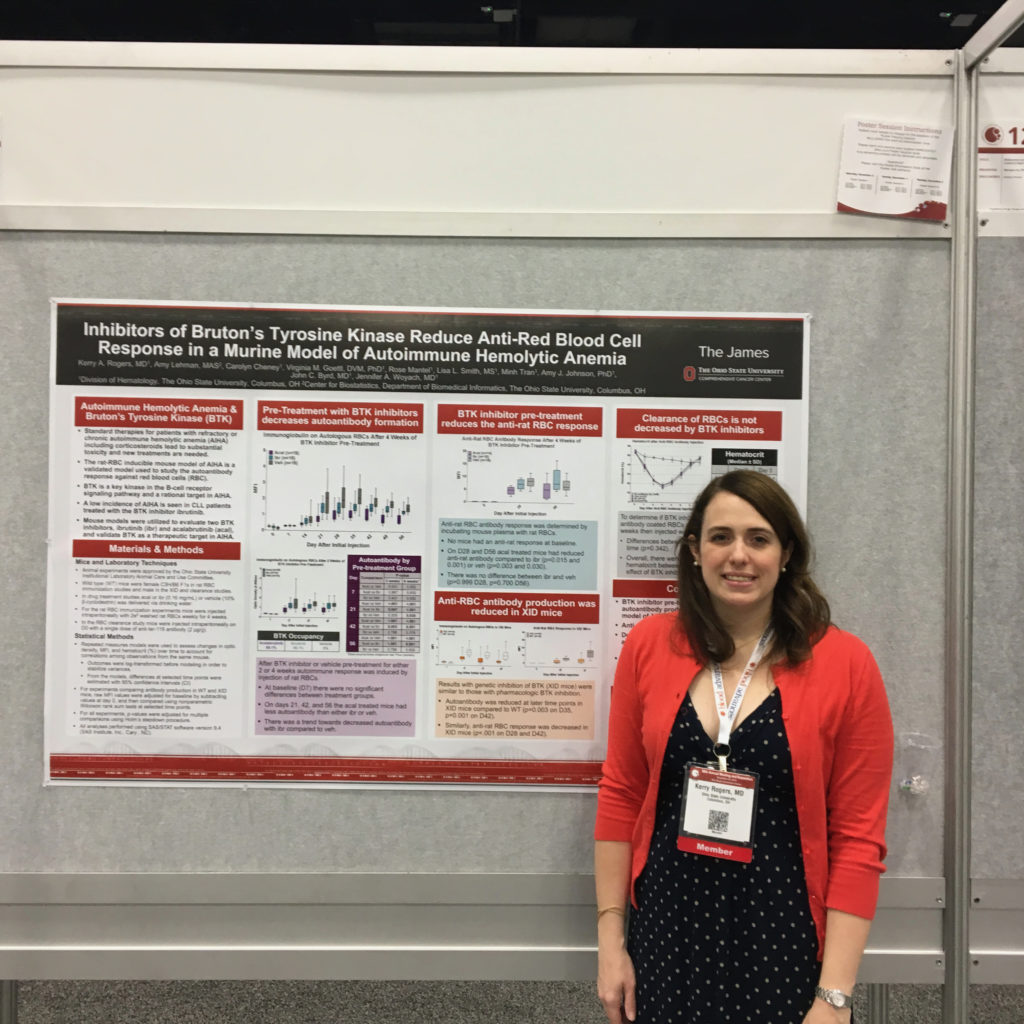

BTK inhibitors

Dr. William Wierda: The next category is BTK-inhibitors. Those have been around longer than BCL-2 inhibitors. Examples of this drug type that we currently have available are acalabrutinib and ibrutinib.

Ibrutinib

Dr. William Wierda: Ibrutinib has the most experience associated with it, and we have the most data and most patients treated so far on clinical trials with ibrutinib.

Acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib

Acalabrutinib, though, is approved. Zanubrutinib is not yet approved, but perhaps will be in the next within the next year probably. Those are drugs that are extremely effective at controlling the disease, but not as effective as, for example:

(BCL-2) venetoclax is in terms of getting the amount of disease down to the point where we’re comfortable with stopping treatment. So the best response the lowest level of disease is usually still measurable with the BTK inhibitors like ibrutinib or acalabrutinib. So patients go on that those medicines and they stay on them until they don’t work any longer. It’s more of a maintenance type treatment.

When BTK inhibitors aren’t effective

Michele Nadeem-Baker: If I’m on, let’s just say ibrutinib, it stops working. Can I go to acalabrutinib and it’ll work?

Dr. William Wierda: So if it’s not working and the disease is growing? Switching to acalabrutinib is not expected to control the disease in a meaningful way.

So both of those drugs belong to a category called irreversible inhibitors. That means they bind to BTK and they in that activate it. And the only way that the cells will the only way the cells can have a functional BTK is to make new. And so it blocks permanently the activity of BTK when it binds to BTK.

Both of those drugs bind to the same amino acid in order to do that. So if and when the main mechanism for resistance is mutation of that amino acid. So if the amino acid is mutated, then whether we’re talking about acalabrutinib or ibrutinib or zanubrutinib. All three of those are the irreversible inhibitors. They no longer bind. They’re no longer effective.

If patients have to stop treatment because there’s a side effect or a toxicity, then yes, and if they don’t have resistance. Resistance is reflected in increase in the white blood cell count while patients are on treatment or enlargement of the lymph nodes while patients are on treatment. That’s what we that’s how we define resistance.

If that’s not happening and patients have to come off because they develop a-fib or a rash or some other reason, then it is reasonable to switch to an alternative, irreversible inhibitor, for example, ibrutinib or acalabrutinib, et cetera.

PI3 Kinase inhibitors

Michele Nadeem-Baker: Thank you. And there was a third that you were going to mention.

Dr. William Wierda: Third category of drugs are the P-I-3 kinase inhibitors. There’s two that we have currently available. One is called Idelalisib. The other is called Duvelisib. Those have a bit more side effects and toxicities associated with them, particularly Idelalisib and are used less frequently these days.

Ibrutinib, the BTK-inhibitors, and the venetoclax or BCL-2 inhibitors are extremely effective and give very good and durable disease control. You can you can switch between those two if you develop resistance. So if you develop resistance to venetoclax, for example, you can switch to one of the BTK-inhibitors and expect the response, and vice versa.

Most important considerations for CLL patients

I don’t like to think about, or talk about, or plan for chemo-immunotherapy any longer because I think it’s inferior treatment for our patients.

Dr. William Wierda

Small molecule inhibitors > chemoimmunotherapy

Michele Nadeem-Baker: What did people learn or what can patients learn from this ASH – from the the latest trials on these particular drugs?

Dr. William Wierda: I think it’s important for patients to know and to think about the fact that there are two strategies for treatment these days with the small molecule inhibitors. And I’ll talk about that in a second.

This ASH, and previous ASH meetings, have all reported out data from these large clinical trials that compare these oral drugs, the small molecule inhibitors to what has been our standard treatment, which is chemoimmunotherapy.

All of those trials show that there are new treatments, the targeted therapies BTKi, BCL-2, are superior to chemo and chemoimmunotherapy, so I don’t like to think about, or talk about, or plan for chemo-immunotherapy any longer because I think it’s inferior treatment for our patients and much more aligned with giving small molecule inhibitor based therapy.

Fixed duration vs. finite duration treatment

I think for patients and moving that discussion a little bit further, what patients need to think about and have a discussion with their physician about is:

- Do I want fixed duration or finite duration treatment? Do I want to get in remission and get off treatment and have a reasonable period of time to expect off treatment in remission?

- Or do I want to go on a maintenance and have medication that I take every day that is extremely effective at controlling the disease? But I continue on it and there are side effects associated with all treatments, including the continuous treatment.

The challenge for the finite duration treatment is that it has to be that you have to monitor patients closely when they start on it because it’s very potent at killing the leukemia cells, and there are some risks initially that we have to monitor for.

Monitoring patients on venetoclax-based regimens

Michele Nadeem-Baker: So would this be on? Let’s just say a CLL patient like myself were to go on like venetoclax, right?

Dosage

Dr. William Wierda: Venetoclax-based. So venetoclax is the BCL-2 inhibitor. That’s the extremely potent drug. And so in order to safely start it, you have to start at a very low dose, 20 milligrams a day and you step up the dose each week. You have to be monitored each time you step up the dose.

In terms of your labs, in order to make sure you’re not having any overwhelming leukemia cell death, which can cause a lot of problems with the kidneys and with the heart, the target dose is 400 milligrams a day, so it ramps up over a month. And that’s a little bit difficult. And it does require going and seeing a physician who’s done that, is familiar with it, and understands and knows how to do the ramp up and can monitor things safely.

If you do the monitoring as it’s been recommended, it’s safe. It’s just work. Once you get to the 400 milligram daily dose, it’s very active and it’s very well tolerated. There’s not a lot of side effects associated with it.

Minimal residual disease (MRD)

Michele Nadeem-Baker: During these conferences, we always hear about PFS, progression free survival, and undetectable-Minimal Residual Disease (uMRD). What is the difference and what trials are showing the best hope for for these?

MRD tests

Dr. William Wierda: Let’s talk about first MRD or minimal residual disease. That is a test we do to determine if we can measure any amount of leukemia. We can do the measurement in the blood or we can do the measurement in the bone marrow.

It’s a very sensitive test that allows us to identify one leukemia cell among 10,000 normal cells and up to one leukemia cell among a million normal cells. So this is a way or a measure that we can check to see if we have a deep remission.

Undetectable disease is a deep remission, whether we’re talking about one in 10,000 or ideally, one in a million leukemia cells. That’s the type of response that we we’re working to get an undetectable-MRD we were working to get with chemotherapy.

Venetoclax-based therapy success

We were able to do it, but not nearly in as many patients as we can achieve now with venetoclax-based therapy. Venetoclax is much more potent and much more effective at achieving undetectable-MRD. That only tells us sort of a snapshot in time. What’s the level of disease a patient has potentially in their body?

Progression-free survival (PFS)

If a patient achieves an undetectable MRD state at the end of treatment, their progression-free survival is going to be significantly longer than if they don’t achieve an undetectable status at the end of treatment.

Dr. William Wierda

Dr. William Wierda: Progression-free survival means, basically, how long does a patient remain in a remission before the disease is growing again? That takes some time.

If we do a clinical trial and we enroll 100 patients, for example, if we’re talking about the median progression-free survival, it takes us a fair amount of time to observe a group of patients who have been treated to determine how long, on average, they’re staying in remission.

That’s kind of what we mean by progression-free survival for drug approval. The FDA needs to see progression free survival, and we also know that if a patient achieves an undetectable MRD state at the end of treatment, their progression-free survival is going to be significantly longer than if they don’t achieve an undetectable status at the end of treatment.

So there is a correlation or relationship between MRD and progression-free survival, but they tell us different information. And with our newer treatments and our combinations of targeted therapy and finite duration treatment, we’re working on achieving as high a percentage of undetectable-MRD as we can.

We hope that ultimately translates into longer progression-free survival for a treatment. As I’m sure you understand, you can’t show that a patient’s cured if they still have measurable leukemia. So we aim to achieve undetectable-MRD state in order to show that our treatments are curative.

When is a patient considered “cured?”

I’m optimistic that we are curing some patients currently with our non-chemo treatment. Certainly, we know patients are being cured with chemo options.

Dr. William Wierda

Michele Nadeem-Baker: We hear as patients that there is no cure yet for CLL. If a patient achieves uMRD, does that mean they have a temporary cure? Or if they’re uMRD for a number of years, are they cured?

Dr. William Wierda: It means that we’re not able to detect any measurable disease. In order for a patient to be cured, meaning no more leukemia period ever to be seen, they have to be undetectable MRD, whether that’s at the end of treatment or it’s three years or five years later.

Our finite duration trials, our fixed duration trials are aimed to achieve an undetectable state historically. So let’s backtrack a little bit. I do think we are curing some patients with our treatments short of our non-transplant treatments.

For example, patients who have a mutated immunoglobulin gene who get chemoimmunotherapy, about half those patients are probably cured, meaning they have more than 10 years of no active progressive CLL. If we look at our FCR data, which is a standard chemoimmunotherapy regimen, many of those patients that I treated 20 years ago are coming back to see me and are still undetectable MRD. Their disease hasn’t come back. It hasn’t progressed. I think those patients are cured.

Can we achieve the same with non-chemo treatments? I think so. But it’s going to take more time, more follow-up, more serial measurements of MRD to show that patients who achieve undetectable-MRD state remain undetectable and also longer period of time to demonstrate that patients are not progressing.

I’m optimistic that we are curing some patients currently with our non-chemo treatment. Certainly, we know patients are being cured with chemo options. The problem is that chemo has side effects and toxicities associated with it, and we have exceptionally good treatments now with small molecule inhibitors to the point where I think despite the fact that we are able to cure some patients with chemo, it doesn’t justify giving every patient who potentially could be cured the chemo because it’s only about half of those patients.

Patients with riskier prognostic indicators

Michele Nadeem-Baker: With the ASH studies, are you seeing that? Getting to uMRD with a BTK inhibitor like an ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, zanabrutinib or venetoclax, or in combination with other drugs? Are you seeing a better chance at patients that might have riskier prognostic indicators like unmutated IGHV or 17p or TP53?

Dr. William Wierda: Right now, we’re seeing good responses for all patients independent of their risk features. If they have an unmutated immunoglobulin gene, their response is similar. If they have a 17p deletion, their response is similar to the non-17p. The challenge for the high risk is showing that they remain in remission and that their disease doesn’t come back and grow.

If we’re talking about achieving an undetectable-MRD state, venetoclax-based therapy is what we need to give to do that. Whether it’s the standard treatment, which is venetoclax plus obinutuzumab, which is a CD20 antibody, or a newer combination, venetoclax + ibrutinib, venetoclax + acalabrutinib – those combinations, all of which include Venetoclax, are intended to get into a deep remission, undetectable MRD and time off treatment.

If we’re talking about BTK-inhibitor based therapy, unless we’re talking about combining BTK with venetoclax, BTK-inhibitor based therapy is more of a continuous treatment until it doesn’t work any longer because we know all of the BTK inhibitors are extremely effective at controlling the disease. They don’t achieve a deep remission, undetectable MRD in a notable percentage of patients so that we feel comfortable getting them off treatment.

Promise of ibrutinib + venetoclax + chemotherapy

Michele Nadeem-Baker: With a BTK like ibrutinib and venetoclax, that is potentially a winning formula for patients then. And when you add in a CD20, like obinutuzumab, is that even better than that?

Dr. William Wierda: That may be better, but there is a bit more side effects and toxicities. So if we’re talking about standard treatments, there was a trial that was presented previously and updated at ASH called the GLOW trial.

That trial is comparing ibrutinib venetoclax with chemotherapy. That trial showed improved outcomes with ibrutinib + venetoclax. About half the patients had undetectable MRD. So although it’s not yet a standard of care, it’s not been approved by the FDA, we are anticipating that it will probably be approved by the FDA as a combination therapy with the expectation of giving 12 months of combined treatment and then getting patients off treatment.

What treatments should patients be watching for right now?

Michele Nadeem-Baker: Wow. That’s nice, that patients can see a light at the end of the tunnel versus indefinite. Do you have any final words for people watching this on who are looking at treatments who are looking to go into treatment or who are on, you know, relapsed and about to go into treatment.

What should they be thinking of? I know it’s different for every patient, but depending on their risk factors, what would be the thing to look for right now or to watch for the future?

Reversible BTK inhibitor (pirtobrutinib)

Dr. William Wierda: There’s a lot of things happening in CLL. There are a lot of new and exciting drugs that we’re studying that are in early development. There’s a drug called pirtobrutinib, which is a reversible inhibitor of BTK, which you would consider giving in a patient who has developed resistance to one of the irreversible inhibitors, such as ibrutinib, venetoclax, zanubrutinib or acalabrutinib.

Pirtobrutinib is looking very promising. It’s active in patients who are resistant to irreversible inhibitors, and those remissions are lasting a reasonable amount of time. It also is working in patients who are resistant to ibrutinib and venetoclax. So we’re excited about that.

CAR T-cell therapy

Dr. William Wierda: CAR T-cell therapy is an exciting topic. It’s an area that I’ve been involved in development. We will hear more about CAR T.

I have had many patients who have been treated with CAR T, who were resistant to standard treatments, who have had very durable remissions and who are doing very well. So for me, that holds a lot of promise for our patients – the CAR T platform.

Bispecifics

Dr. William Wierda: The bispecifics are an area of new drugs that are in development that are very exciting, these combinations and using the tools that we have to optimize treatment to get the best outcomes for our patients. So if we have patients who are thinking about treatment, planning for treatment, getting information is very important, talking to the to the doctor about what the treatment options are.

Importance of seeing a CLL specialist

Dr. William Wierda: I assume this group, because they’re on the internet, are probably already an informed group and have an understanding of the treatment landscape and treatment approaches, but it’s important to have a discussion with the doctor.

I think it’s important for people to see a specialist, for example, who sees predominantly CLL (patients) and is aware of what’s going on. I think those of us who are specialists look forward to the opportunity ofs working with the local doctor. If we have patients who are referred to us for a recommendation, usually the referring doctors are happy to have suggestions, recommendations, and to work with us.

I think clinical trials are important. They’re the only way that we’re going to make progress in the disease.

Dr. William Wierda

Clinical trials

And then clinical trials, I think, are important. Our clinical trials at MD Anderson are usually what’s called phase two, meaning all the patients get pretty much the same treatment and they won’t get a standard treatment like chemotherapy where they could get that with a phase three study. I think clinical trials are important. They’re the only way that we’re going to make progress in the disease. They’re the only way we’ve made made progress in treating a disease, and they’re very, very important.

Michele Nadeem-Baker: Well, thank you for all the work that that you do for CLL patients, Dr. Wierda. It’s it’s amazing how I’ve seen things, all the choices now that there are since I was first diagnosed nine years ago, and I look forward to our next conversation.

Dr. William Wierda: Great. Well, thank you for having me.

Michele Nadeem-Baker: It’s been our pleasure, at The Patient Story, and for everyone who wants to access this interview and our full conversation, please head to thepatientstory.com, where you’ll find human answers to your cancer questions. This is Michele Nadeem-Baker for The Patient Story. Have a wonderful day.