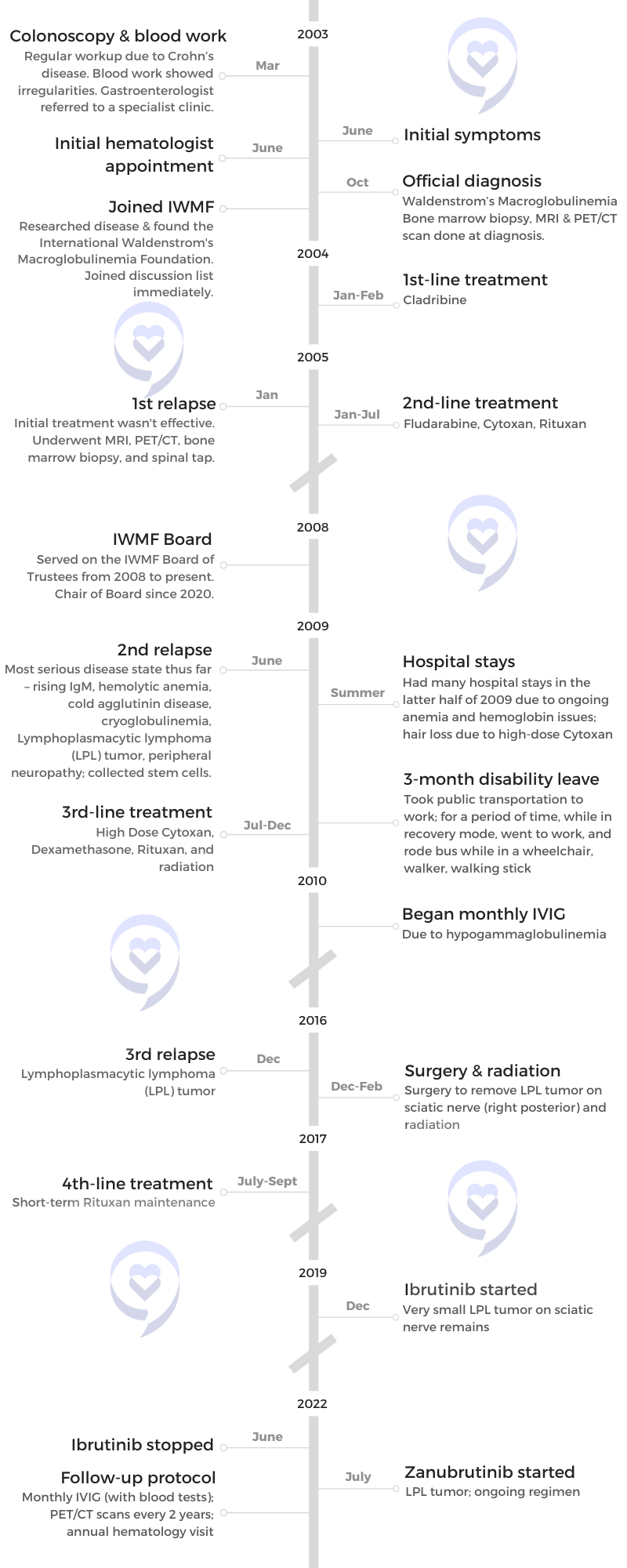

Pete DeNardis’s Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Story

Pete DeNardis was diagnosed with Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) at 43. It is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and is a rare cancer that begins in the white blood cells.

He shares the importance of educating yourself about your disease, communicating with your disease community, getting a good support system, improving your quality of life, and being your own advocate.

- Name: Pete DeNardis

- Diagnosis:

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Initial Symptom:

- Irregular blood test results during a regular workup for Crohn’s

- 1st-line Treatment:

- Cladribine

- 2nd-line Treatment:

- Fludarabine

- Cytoxan

- Rituxan

- 3rd-line Treatment:

- High-dose Cytoxan

- Dexamethasone

- Rituxan

- Radiation

- 4th-line Treatment:

- Rituxan (short-term maintenance)

- Ongoing Treatment:

- Ibrutinib (December 2019 to June 2022)

- Zanubrutinib (started July 2022)

- Monthly IVIG

If you see one Waldenström patient, you’ve seen one Waldenström patient because we’re all different. We have the same disease, but our bodies behave differently.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Pre-diagnosis

Tell us about yourself

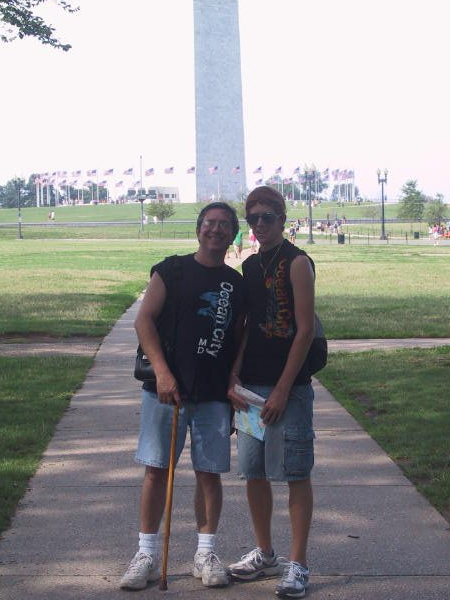

I live in the United States, in Pittsburgh, but I was born in Italy, came over when I was six months old, and got my citizenship when I was six years old. I had your basic American upbringing [and] had a little bit of Italian spoken in the household. I was bilingual initially and still retain some of that.

I’ve been working as an accountant for a long time. I gravitated towards working in financial systems because I also like playing with computers so I’m sort of a financial systems analyst, a hybrid of sorts.

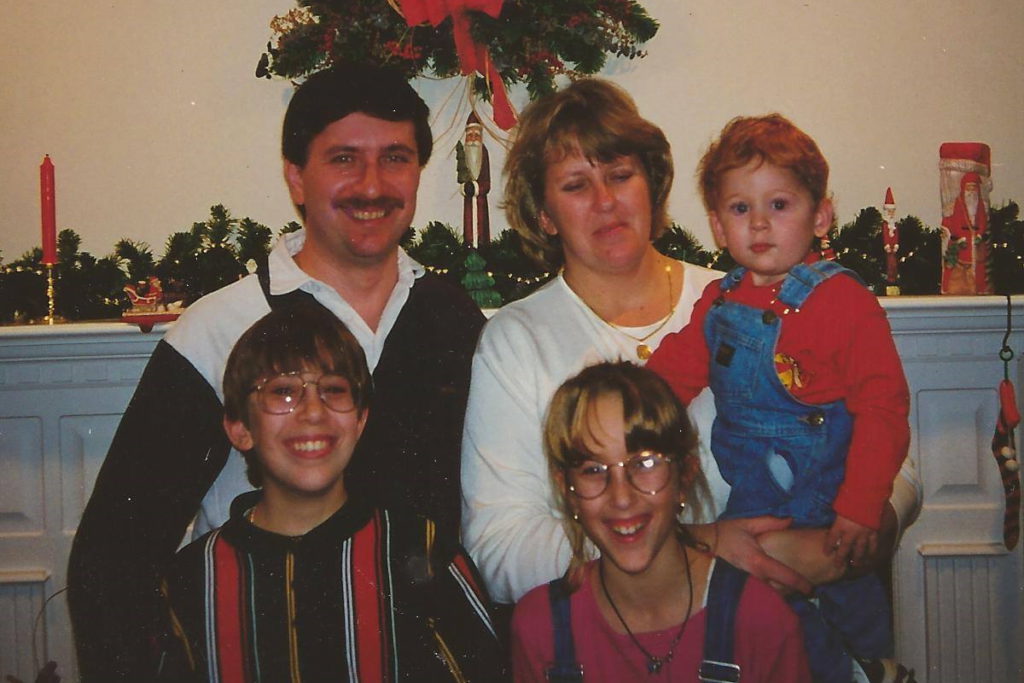

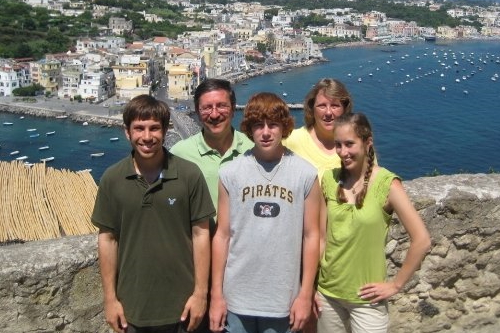

I have a family and three kids. Two of them are married and two grandchildren came in the past year and a half.

Initial symptoms

At that time, I had just started a new job. I decided to change careers. A lot of people do that after they get cancer; I did it before and I decided I wanted to teach full-time. I was teaching part-time for a while and I got an opportunity to teach at Penn State’s Beaver Campus.

I was setting up classes and working during the summer. I was in this little office, like a closet. I started to feel tired. I thought, I’m just working too hard, trying to try to learn how to do all of this, and also prepare materials for classes.

Then I started having severe nosebleeds, but I thought, I just have a cold or something. They were pretty serious nosebleeds. It was very difficult to stop them, but for whatever reason, I was on that work train and wouldn’t stop.

[My gastroenterologist] called and said, ‘Did you ever call that number that I gave you?’ I said, ‘No, I got busy, I forgot.’ But he said, ‘It’s really important that you call that number right away.’

It was so bad that I would end up with blood going down my shirt from the nosebleed. I would wipe it up or try to hide it at least and then get the heck out of there. But it happened fairly frequently so then I thought, something’s going on, but I’m too busy. Every once in a while, it would stop so I didn’t think anything of it. It’s a pretty good flow coming out of your nose, which is not normal even for someone who normally gets nosebleeds.

I also had a colonoscopy because I have Crohn’s disease so I do that every couple of years. Part of that is the blood test workup. At around the same time, my gastroenterologist called and said, ‘I saw some funny numbers.’ He might have said elevated protein, but it didn’t mean anything to me at the time because I didn’t pay attention to that stuff and I ignored it.

Three months later, he called and said, “Did you ever call that number that I gave you?” I said, “No, I got busy, I forgot.” But he said, “It’s really important that you call that number right away.” He didn’t say anything else.

Initial hematology appointment

I called the number and the receptionist said such and such hematology clinic. Right there I thought, “Oh, something’s up here. I don’t know, but this doesn’t sound good.” We made an appointment. My wife and I went and we did blood work.

We got to meet with a hematologist and he said, “Based on your blood work, it appears you have some type of lymphoma. I’m not sure what it is. We can do the bone marrow biopsy right now if you want, or you can schedule it.” I said schedule, but my wife, being my very important caregiver, said, “No, we’re doing it right away. I don’t want you putting it off.” We did that right there.

Bone marrow biopsy

It was an interesting experience, to say the least. They did numb the area, but I was not sedated — a bit uncomfortable, put it that way.

‘It appears to be a rare form of cancer that’s not curable. You should really think about getting your affairs in order.’

Diagnosis

It takes a couple of weeks to get the results. We went back to see him and he basically said, “I’m not certain, but it appears to be a rare form of cancer that’s not curable. You should really think about getting your affairs in order.”

Getting a second opinion

We were in shock, but we sat back and said, “Okay, I’ve already had one chronic illness. Let’s add another one to it. Let’s move on. There’s got to be something we can do.” We said, “Okay, I appreciate your opinion, but can I get a second opinion? Because I can’t believe that I can’t do anything about it and I’m going to die in six years.” He did say, “Well, that’s your prerogative and that’s your opinion. I’ll be glad to give you the name of someone else who’ll probably be more than willing to treat you right away.”

I thought, well, that’s an odd attitude to take, so I’m glad that I’m getting [a] second opinion. The doctor that he sent me to was actually a pretty good doctor. Right away, I had a good relationship with him and that’s when I started treatment, right away at that point.

‘I appreciate your opinion, but can I get a second opinion? Because I can’t believe that I can’t do anything about it and I’m going to die in six years.’

Deciding to get a second opinion

It’s important, especially when you have a rare form of cancer, to seek out those centers of excellence if you can. If you can’t afford that or can’t travel to it, go to a larger research university-based hospital. Fortunately, I live close to one in Pittsburgh. We have the University of Pittsburgh. We have a lot of research going on there. I was able to go to both hospital systems that I can go to. They both have noted researchers there so that makes a big difference.

If you go to a community hospital — I’m not denigrating the hematologists or the cancer doctors there — but they may not even see a person with my disease in their whole career. It’s important to get in touch with a doctor that has experience with your disease or can consult with other doctors in their practice that do have patients with your disease.

It’s important, especially when you have a rare form of cancer, to seek out those centers of excellence.

That first doctor had that attitude and maybe he was right, but that attitude of I know what I’m talking about so don’t question me. Even his staff, when I would call and say, “Hey, why is he requiring this test?” Or “Why does he want me to do this?” They would say, “Well, why would you question that?’ And wouldn’t even answer the question. I knew right then that definitely I’m not going to this place again.

The second doctor was much more open. He sat down with you. He drew charts. He explained. He said, “Okay, you have Waldenström macroglobulinemia and we’re going to treat it. This is how we’re going to treat it. This is standard treatment at this point in time and just because you see a lot of statistics out there, that’s an average. That’s just the median. Some people live shorter, some people live a lot longer. And given that you’re diagnosed at an earlier age, there’s a good chance you’re going to live for a lot longer than those six years that they’ve been quoting to you. Plus, I have the ability to consult with a lot of other researchers and hematologists in our practice and in our hospital system. We’ll discuss your case and we’ll treat you accordingly.”

What really hit home was wow, I won’t get to see them graduate. I won’t get to see them get married. I won’t get to see any of the special moments in their lives.

Processing the diagnosis

[My wife and I], we do everything together so right off the bat, my first concern was for her. What’s she going to do if I’m not around?

Then the thoughts automatically go to my children. I’m not going to be around. They’re in grade school and high school. They were seven, 14, and 16 at the time. What really hit home was I won’t get to see them graduate. I won’t get to see them get married. I won’t get to see any of the special moments in their lives. They won’t have me around. That was [what] hit me the hardest, not being there for my family.

You can’t bottle that up. You bottle that up, that gets even worse. There was a lot of crying, hand-holding, and just worrying about all of that. I think that’s normal and that’s healthy to let it out rather than bottle it up. I’m not saying you have to cry every hour of the day but that’s important to let that out.

We laid it out to them straight and said, ‘Look, dad has cancer,’ and try to tell them in as simple a way as possible.

Breaking the news to the children

Once we found out exactly what I had, did a little research on the disease, and then found that it wasn’t an immediate death sentence — because I was diagnosed at 43, which is unusually early for this disease — we decided that because I had to go into treatment right away and I could be pretty weak from the treatment — could have some odd side effects — we felt it was important to let the kids know if I’m not going to be around to take them to soccer practice or any of their school events, they should know why.

We laid it out to them straight and said, “Look, dad has cancer” and try to tell them in as simple a way as possible, that it’s serious but it’s treatable and we just have to go with the flow and I’ll be around for a long time. I’m not going anywhere.

I always told my wife that she can’t get rid of me that easily. We’re honest and upfront, but we’re willing to answer any questions they had. The older ones were fairly intelligent to figure out how to find information, but we did try to answer their questions and were upfront with them. That worked for us.

We’re honest and upfront, but we’re willing to answer any questions they had.

Importance of doctor-patient relationship

What I liked about the second doctor I went to was, right away, I felt a connection with him that I didn’t have with the first doctor. Sometimes it’s a personality thing. It’s their demeanor; you click. It’s odd that that’s an important aspect of it, the human element of that, not just the scientific.

I’ve talked to other Waldenström patients and some, they’ll say, “You go to that doctor? Oh, I can’t stand that doctor.” Because they don’t connect, their personalities don’t work, they want something different — and that’s normal. That’s part of it also.

The important thing is to become educated. When that doctor said, ‘Okay, here’s the treatment plan we’re going to do. It’s fairly standard. We’re going to try this first.’ It was Cladribine and I did a little research on it.

Even then, I went searching on the Internet and found the International Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation, hooked up with their online discussion list, and automatically started asking fellow patients. “What do you think of this? Will it work?” Basically, the response I got was there may be better options but as a first-time treatment, at that point in time, it was the least toxic so give it a shot [and] see if it works. It may or may not. And so we went with that.

Initial treatment

I [started treatment] right off the bat in 2003 with Cladribine.

First relapse

Expectation setting

With Cladribine, the thinking was I should get two to five years of response. They don’t like to use the word remission if you’re in a recurring kind of cancer. That was the expectation and unfortunately, I didn’t even get that.

[I was getting] monthly blood tests at that time. We saw the numbers — their marker, which is immunoglobulin — the IgM marker dipped down a little bit but started rising right back up again. We knew it wasn’t working.

Dealing with scanxiety

Back then, you didn’t get your blood results immediately. You had to wait a few days and so that was nerve-wracking because you don’t know what to expect from the results. [There] was always that fear that, Oh, here we go. We’re going to have to go back to treatment again. You dread it but also look forward to it because maybe it’ll be a good result.

It’s better now because you find out almost right away what your blood work results are. I’m in a different position now. I know my body better so I know when things are going well and when they aren’t.

Second-line treatment

The next round was Fludarabine-Cytoxan-Rituxan. At that time in 2005, it was being used but there were rumblings in the research community that you might not want to do that.

FCR was found to be effective. I knew it would be more toxic in terms of side effects so they put me on antivirals and all the other stuff to minimize the side effects.

Every treatment has some side effects so it basically comes down to ‘pick your poison.’

Getting information on new treatment

At that time, Rituxan was fairly new. I questioned the doctor and our patient community [about] what they knew about it, how well it worked, and whether it was dangerous long term. In hindsight, that was a dumb question to ask but who knew back then?

Always go through that process of looking at what’s out there. I’m able to access some medical journals because I work at a university so I follow what’s happening in my disease and related diseases. I’m always looking at the research results of newer novel agents in related diseases — like CLL, WM, multiple myeloma, or other diseases — just to keep track of what’s up and coming and see what are the side effects.

With any novel agent — like for Waldenstrom’s, the newer ones are the BTK inhibitors and so I read up on the side effects of BTK inhibitors. Now granted, when it first comes out, you don’t have a long period of time to figure out the long-term effect.

A couple of the noted experts would always tell me, at least right now, there is no safe treatment. They said, in fact, the best treatment is no treatment at all if you don’t need treatment. But every treatment has some side effects so it basically comes down to “pick your poison.” The idea is what gives me the best potential for a longer period of quietness and minimal side effects.

I like to chart my own blood values so I would be able to see month to month how it was trending. It was exciting to see it actually going in the right direction.

It’s a balancing act, the kind of side effects you could experience. [With] BTK inhibitors, you could get elevated heart rhythm, high blood pressure, [and] elevated glucose levels. You have to deal with all of that. The flip side is your disease goes into a very quiet state for a potentially long period of time, but also, you have to take it every day for the rest of your life.

It’s also very expensive, which is another thing now that we have to consider. Very frustrating, at least in the United States, the fact that financial toxicity is becoming such a big issue.

Responding to the treatment

Right from the start, I like to chart my own blood values so I would be able to see month to month how it was trending. It was exciting to see it actually going in the right direction. I can’t say I didn’t think about it, but I could start focusing more on other things.

I actually enrolled in grad school and thought I’d work on a Ph.D. I did coursework in that and I thought, This is good. Every so often, I’ll get treatment. It’s not that bad and then [I] didn’t need another treatment and I’ll be okay. I went into a sense of security… maybe a false sense of security. But knowing that I was doing better [and] I felt better made a big difference compared to where I was before I started getting treated. That was the way I was looking at it.

Very frustrating, at least in the United States, the fact that financial toxicity is becoming such a big issue.

Second relapse

Symptoms

I did notice that I was starting to get a little bit more tired, a little bit more fatigued. I was watching the chart and would show it to the doctor. He would kind of smirk a little bit but then he would look at it. He would say, “Yeah, you’re right, it is going up but it’s not too bad yet and you don’t seem to have severe symptoms so go enjoy yourself. Have a good time.”

As much as I do, he knew the quality of life was important. He said, “Go, and then when you come back, we’ll talk about your options.” We did a month-long vacation to be with relatives and do all the tourist stuff in Italy and had a great time.

Towards the end, I was sleeping longer and started to get a cough that wouldn’t go away. I got some medicine there from a local doctor. It was some kind of injection of an antibiotic that they told me when I came back here was pretty strong stuff. I still was very tired and fatigued. I knew something was wrong. The trip back was not fun.

Complications

That relapse was pretty serious for me. I had a lot of things going wrong. It’s [already] unusual that I have a rare disease at a young age compared to other people but on top of that, I had other complications that go with that disease.

I had hemolytic anemia. Basically, my red blood cells would just be chewed away and I couldn’t replace them unless I got a transfusion so I became transfusion dependent. I don’t know how many blood transfusions I had. Maybe 16 of them over a period of three or four months.

I had cold agglutinin disease and cryoglobulinemia, which means, to add insult to injury, they had to warm the blood up in order for me to get the transfusion so that it wouldn’t clot. It was an interesting experience because they hadn’t used the blood warming machine in years so the nurses were kind of saying, “How does this work? Do you know?”

To compound things a little more, I started to have severe, lower back pain and we weren’t sure what was causing that. Did an MRI and really couldn’t tell too much from that. It became so bad.

At that time, my oldest son was going to grad school and we had to drive him to New York from Pittsburgh. I couldn’t sit normally in the car. I had to kneel down basically on the front seat and lean backward in order to just withstand it. It was important to me to get him there, get back home, and see the doctor right away. Priorities.

What we found based on [the] PET scan and further testing was a tumor at the base of the spine. It was lighting up. You have those FDG uptakes. They were able to biopsy it and found that it was a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, a Waldenstrom’s tumor.

We didn’t know the way to treat that. It seemed like every time we went to the doctor, there would be that team of doctors and med students, all scratching their heads [and] saying, “Huh. This is an interesting case.” Thank you. I feel so good about that. At least I have their attention, I guess, is one way to look at it.

Third-line treatment

My doctor admitted [and] said, “Look, I have not experienced this before. We’re going to try and figure this out. Here’s what I think we should do. I want to collect your stem cells, just in case. But first I want to knock your disease down with some heavy-duty stuff to get your immune system at least at a certain baseline.”

He suggested high-dose Cytoxan. I would lose my hair, which normally doesn’t happen in Waldenstrom’s but I did go through that. “We’ll do some Dexamethasone to go along with that, some Rituxan, and do radiation to the tumors.” I said, “Well, I think that makes sense, but I want a second opinion.”

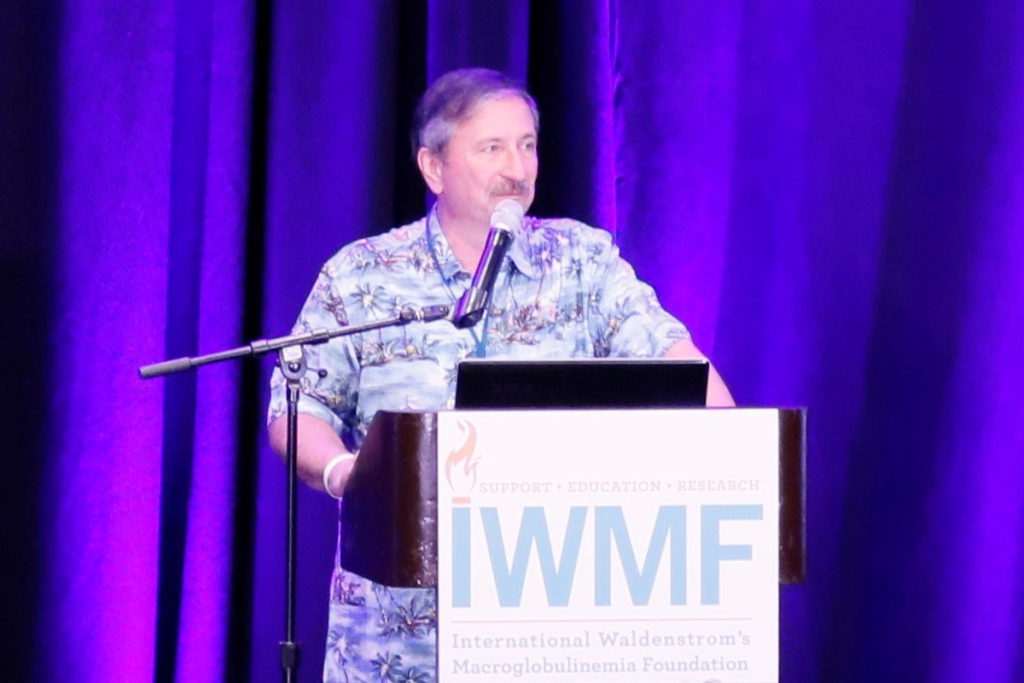

I was involved with the IWMF at that time. I knew who the leading researchers were in the world and, fortunately, they’re in the United States — one at Dana-Farber, one at Mayo Clinic — and I asked if he would confer with one of them. He said, “Sure! I’d be glad to. No problem. I’ll call them.”

He called them — and I won’t name any names because the expert that he contacted said, “Look. He’s at a relatively young age. It might be a good idea to consider a stem cell transplant.” At the time, I was so weak and I had a feeling that there was no way I could withstand a stem cell transplant. It was not the right thing for me at the time.

[Then] he said, “But the treatment plan that you have for high-dose Cytoxan and Dexamethasone and radiation is a good treatment plan. It can work.” We went with that and my doctor said, “You pick. Which one do you want?” And he said, “You made a good choice. I would have gone with that, too.”

Shared treatment decision-making

Working with that doctor, he was willing to go back and forth. I get this a lot now from him and from the current doctor that I’m seeing. They both said, “Here are your options. Which one do you want?” It’s like, “Well, I’m not the hematologist. How am I supposed to know?” That’s the first thing that comes [to] your mind. But then you take a step back and say, Yeah, he’s right. There are options.

Sometimes, it is up to the patient what they’re willing to tolerate and what they think they can tolerate in terms of the treatment protocol, side effects you could get, and things along those lines.

I guess they take their cues from what the patient is like and then get an idea of that. Some patients are more risk tolerant, others are not, and so they go with that. They don’t want the patient to say, “Well, you told me to do this. I should have done that.” That’s part of it, too.

Sometimes, it is up to the patient what they’re willing to tolerate and what they think they can tolerate.

The part where it hits home [is] that it’s part art and part science. There’s no clear definition of what is going to work and what isn’t, especially for many cancers. People don’t realize that they’re making gut-level decisions based on what they know at that point in time and they’re never certain if it’s the right decision or not.

I’ve told other Waldenstrom’s patients that if you see one Waldenstrom’s patient, you’ve seen one Waldenstrom’s patient because we’re all different. We have the same disease, but our bodies behave differently. We have different genetic aspects of our disease. We just belong to the same family in a sense, but we’re all different.

Responding to the treatment

It was a several months process of going through treatment and radiation and I got a very good response from it. I even had surgery to remove part of the tumor.

Normally, [a WM patient] has immunoglobulins circulating in the blood at an elevated level. After this treatment, after so many months, those no longer exist. I don’t have them to the point where it’s now below normal and it’s been that way since 2010. When they do a bone marrow biopsy, it’s not in the bone marrow either, which is also unusual.

It got to a point where somewhere around 2015, five years out, my doctor said, “We can maybe start saying the C word for cure because this is really strange, really unusual.” Well, he shouldn’t have said that.

Dealing with neuropathy

Because of the tumor, my right foot and right leg have neuropathy in it. I went through a process of having to deal with being weak. I was so weak that I was in a wheelchair. Then I went to a walker and then to a walking stick.

I tried to keep working the whole time, full time, because I was the main breadwinner for my family. I took public transportation so my wife would drive me to the bus stop. She would haul the wheelchair out, wheel me to the bus, I would get on the bus, and then get off.

It was fortitude. Just one day, then the next day, then the next day — just keep moving. Over time, it did get better because initially, I was lucky [if] I could walk 50 feet down the sidewalk in front of my house. My wife, fortunately, forced me [and] said, “You have to get up. You can’t stay sitting down and being sedentary. It’s just going to make it worse. Just get up. If you can’t make it, we’ll turn around and go back.” And that’s what we did.

Losing independence

That was very difficult. I couldn’t even go into the shower or anything on my own. My wife would have to help me and wash me initially and that was very demoralizing because I’ve never been in that kind of situation.

You reach a low point when you say, “Well, jeez, I’ve done everything. I’m trying to do the best for my family and here I am. I can’t even take care of myself. How am I going to be able to take care of them? And how long is this going to last? My goodness. Day after day, I have to do this. When is it going to get better?”

I couldn’t even go into the shower on my own. My wife would have to help me and that was very demoralizing because I’ve never been in that kind of situation.

All those thoughts [go] running through your head. I don’t know what got me out of that situation. Definitely, it was a support system that I had, my wife and family and the IWMF community of patients and caregivers around the world, who sent prayers and positive thoughts my way – but there’s more to it than that.

You can’t let that low moment pull you even further down. In hindsight, I can say that. But, at the time, my mindset was, Okay. This is not good. I know it’s not good. If I have to cry, I’ll cry, but I have to move on. I have to keep going. I have to find a way to figure out — can I swing my leg over the tub? One little thing, at least. Can I dry one part of my body on my own? Can I try little things and keep working at [them] and find positive things to do rather than dwelling on what I can’t do?

Financial impact

It was difficult because, with our family dynamics, it was my salary basically that supported the family. My wife worked also but there was a disparity in the salary so to not have me earning money was a serious consideration.

Initially, even my manager — very understanding and very supportive — said, “Look. Do you want to go on leave? Do you want to go on disability leave?” I said, “Oh, I hadn’t thought of that.” Then when I looked into it, I saw, That’s 60% of your salary and I don’t know if I can afford that, and so I didn’t do that. I did it when I had to but that aspect of it was also weighing on my mind.

There was no way around that because we have bills to pay. Back then, there was no GoFundMe and I wouldn’t have done that anyhow because that’s just not me — not to say that’s not the right thing for some people. For some people, that’s their only option and I applaud that. But it just wasn’t me.

I had to find a way to move on. Maybe [what] also helped me recover was that I got to support my family. I have to get better. I have no choice.

Finding a new tumor

I did notice that I was getting more numbness and tingling. I knew something was going on, possibly the little tumor was getting larger. There were other things going on and so I combined a couple of things that occurred at that time.

I also went to see a surgeon because of that numbness. He said, “Ah, it’s a classic schwannoma.” I thought, Okay, another word I have to learn. Basically, it’s a benign tumor so I said, “If you don’t think it’s my LPL coming back or my Waldenstrom’s coming back, then I’ll go for that because I’d rather believe that than anything else.”

When they opened me up and did the biopsy, they got most of it but it was so tangled with the nerves at the base of the spine that they couldn’t get it all out. They said, “Sorry, it’s an LPL tumor. We’re going to do some more radiation then we’re going to follow up with some treatment.”

Treating with BTK inhibitors

Fortunately, at the time, there was some research being done that showed that the new BTK inhibitors, like Ibrutinib, had a good response rate on people who had extramedullary tumors. We decided to go with that, conferred with the doctor, checked with a couple of specialists out there, and said, “Yeah, let’s give it a shot. It can’t hurt.” Depends on what you call hurt, but it doesn’t make the disease worse.

I get other side effects that I have to deal with now. It’s now been a couple of years since I started that.

I switched to a different BTK inhibitor because I read that it had [a] better response rate among people with extramedullary tumors so I thought, Well, let’s switch. It’s not going to hurt me. I’d rather go for what’s best at this point in time.

I won’t know until my next PET scan — I get it every couple of years — what kind of effect, if any, it may have on my LPL tumor that’s still there.

Effectiveness of Ibrutinib

I have not had scans since I started [but there’s] less tingling and numbness. Now it’s just normal numbness, put it that way. It’s always numb, but now, I don’t notice any odd sensations.

Decision to delay scans

I’ve had three or four PET scans so far in my disease course. You don’t want to get too many of those because you don’t want to build up radiation in your body. We try and extend that out as much as possible.

IVIG treatment

The IVIG, I get because I have hypogammaglobulinemia — all my immunoglobulins have been wiped out. The treatment works so well that it killed the bad cells and the good cells.

For a lot of people, if they have low levels of immunoglobulins, they’re not impacted too badly. But for me, I would get recurring sinus infections and other infections. The antibiotics would work [but] when I stop the antibiotics, it’d come right back. We felt the best thing for me to do was to go on IVIG monthly.

The blood products are collected from plasma donors, and it takes [up] to 10,000 plasma donors to make one treatment bag of IVIG. It’s an amazing thing that happens.

I’m always very appreciative of plasma donors. I am forever grateful because it keeps me going. If you know people, tell them [to] donate plasma.

The process that I’m going through now is that I’m on the BTK inhibitor and I get IVIG every month. Fortunately, I have a decent medical insurance plan that doesn’t cost me anything other than the monthly premium. But when I retire and go on Medicare, we’ll see. Things could be different.

Living with Waldenström

Knock on wood, I feel fine. I continue to work full time. I teach a class or two on the side when I get the opportunity because I enjoy teaching.

I also volunteer for the IWMF. I’ve been on their board for almost 10 years now and I’m currently the chairman of their board of trustees. It’s not a paid position by any means. I do it because I feel like I’m giving back to the people that helped me when I first started out.

I continue to learn more about the disease and to keep up with what’s going on. It keeps me in tune with what’s happening and I get to continue to engage with my second family. I appreciate that. I appreciate their support and also being able to support them in turn.

‘Why me? Why do I have to be unusual in the first place? What did I ever do to deserve this?’

Access to information

Important for any cancer patient, regardless of what type of cancer you have, to go visit Dr. Google. Not to say that you should believe everything that’s out there but go to the sources that are credible, like the American Cancer Society [and the] Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

If you have an organization that’s specific to your type of disease, definitely hook up with those people. For my disease, it is the International Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation. You’ll get not only the latest information specific to your disease and what treatments work well but also, just as importantly, the opportunity to hook up with the community of people that are traveling the same journey you are. You can share your stories, your thoughts, your fears, and your experiences.

There are moments when you really start to think about, ‘How bad off am I? How bad is this going to get?’

Looking for a cancer patient community

Just from joining the IWMF, it’s like I have a second family. The support that I have through them is invaluable. Every time I have a relapse or have something going on, I ask a question [and] I get a response right away. I get different responses, of course, but then I can make a more educated decision on what’s going on. I, at least, have a sounding board so I think it’s important to not only have a good medical team but also a good support system — not only from your local friends and family but also from your disease family if you can.

Coping with a rare cancer

At first, what goes through your mind is, “Why me? Why do I have to be unusual in the first place?” Then on top of that, I get something even more unusual. “What did I ever do to deserve this?” Then you say, “Well, maybe this is it for me.”

There are moments when you really start to think about, “How bad off am I? How bad is this going to get?” Because they don’t know what’s going on, I don’t know what’s going on, and we don’t know how to treat it. You get to a low point and you say, “Okay, I’m going to cry it out.” You do that then move on and see what [you] can do.

At a certain point, you reach [the] realization that it’s either going to work or it’s not and you have to get a level of comfort with [it]. Hope for the best and say, “I’m not ready to go anywhere. But if it doesn’t work, I gave it my best shot.”

The approach I took was that I have to hope for the best because I want to be around. I’m unique. I can’t help that and that’s just the way the cards were dealt with to me. I just have to deal with that.

At a certain point, you reach [the] realization that it’s either going to work or it’s not and you have to get a level of comfort with [it].

Self-advocacy: The importance of speaking up

Even [for] something as simple as a blood test, they had to keep the blood warm. You had to tell them that. Not to minimize [or] denigrate those nurses, but you had to impress upon them, “Look, I have cold agglutinin disease. Please make sure you keep it warm. Wrap it in a towel, do something, and get it to the lab right away.” Sometimes if you don’t tell them, they would not realize it and I understand that. You have to speak up.

Don’t be afraid that they’re going to think that you’re trying to tell them what to do. Don’t worry about that at all. Just tell them — even if they give you a nasty look, you got the message across. They heard it and they say, “Yeah, I know.” That’s fine. Great. I’m glad you know. Take care of it.

You’re much better off than if you didn’t say anything at all and it got messed up and they had to poke you again three or four times just to get your blood drawn.

Having cancer gives you a renewed focus on the fact that we don’t know how long we’re going to be around.

Words of advice

I wish I had a magic solution because I’m one of those people that a lot of people say, “Oh, you look so great.” Yeah, but still, I have this thing hanging in the back of my head all the time. Even though I know I’m doing well, I’m always thinking, Well, when is it going to get worse? When am I going to get the next major relapse? It’s there. I don’t know if you want to call it PTSD or what you want to call it.

Having cancer gives you a renewed focus on the fact that we don’t know how long we’re going to be around so you try to enjoy whatever you can, even if it’s just a nice dinner. It’s fantastic.

Don’t dwell on the things that are negative because that just makes your quality of life even worse. The important thing is to improve your quality of life and work on that. Even though you may be feeling sick — you may not be able to get out of bed; you may not be able to get up from the couch — find things that you find joy in and try and focus on that.

It’s not easy. You can’t always achieve that. But that’s what guides me and what gets me going. My family and things like that help me.

Don’t dwell on the things that are negative. The important thing is to improve your quality of life and work on that.

It’s important to improve your quality of life. I hate to be a downer, but you may still be in such a situation that’s very serious and you may not come out in a good position. But it’s the quality of life, not necessarily the quantity that’s important so trying to do whatever you can to improve your quality of life is very important.

Be your own advocate. If they want to give you something, say, “Why are you giving me that?” If they give you a set of pills and it looks different than [the] day before, ask them about it because they’re busy and sometimes they say, “Oh! Oh, that was for the patient in the other room, not you.” I’m not saying that that happens all the time, but it can happen so it’s important to be your own advocate. Be educated and be positive.

Hopefully, together, we can give some people some valuable information and help others that are traveling the same journey.

There are going to be good periods and bad periods. Resign yourself to that and find things that help you get through bad periods.

Inspired by Pete's story?

Share your story, too!

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Stories

Stephanie V., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Asthma/allergy-like symptoms, lungs felt itchy, shortness of breath, persistent coughing

Treatments: Pigtail catheter for pleural drainage, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), R-EPOCH chemotherapy (6 cycles)

...

Stephanie R., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Elevated white blood cell count

Treatments: 6 months of rituximab + ibrutinib, 4 cycles of hyper-CVAD chemotherapy

...

Sheryl B., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: (Over 15 years) Skin irritation from temperature changes, rising WBC levels, unexplained fatigue, retinal hemorrhage, hardened abdomen (from enlarged spleen)

Treatment: 6 cycles Hyper-CVAD chemotherapy

...

Shari B., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptom: None; lymphoma discovered at unrelated doctor appointment

Treatments: 6 cycles R-CHOP, 5 cycles phase 3 trial of Velcade + Rituxan (normally for multiple myeloma), allogeneic bone marrow transplant (BMT)

...

Shahzad B., Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Extreme fatigue

Treatments: R&B, R-ICE, R-EPOCH, CAR T-cell therapy (cell-based gene therapy)

...

Sandy D., Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Stage 4

Symptoms: Persistent coughing, weakness, shortness of breath

Treatment: Chemotherapy

...

Symptoms: Chest pain, back pain, bump on neck, night sweats Treatments: Chemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapy...

Richard P., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Relapse Symptoms: Swelling in leg, leg edema Treatments: R-CHOP chemotherapy, clinical trial (venetoclax-selinexor)

...

Paige C., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Weight loss, extreme fatigue, swollen lymph nodes in the neck

Treatment: R-EPOCH chemotherapy

...

Ashley P., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Feeling like holding breath when bending down or picking up objects from the floor, waking abruptly at night feeling “off,” one episode of fainting (syncope), presence of a large mass in the breast

Treatments: Chemotherapy, bridge therapy of chemotherapy and radiation, CAR T-cell therapy

...

Nolan W., T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma (T/HRBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Debilitating fatigue, flu-like symptoms without a fever, swollen lymph node under the left arm

Treatments: Chemotherapy (R-EPOCH & RICE), bone marrow transplant

...

Nina L., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Hip and lower extremities pain, night sweats

Treatment: Chemotherapy (R-CHOP)

...

Symptoms: Fatigue, weight loss, lumps in the neck and groin

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation, platelet transfusion...

Mike E., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Persistent, significant back pain

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy

...

Mags B., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Exhaustion, migraines, persistent coughs, swelling and discoloration in left arm

Treatment: Chemotherapy (R-CHOP, 6 cycles)

...

Luis V., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Persistent cough, fatigue, unexplained weight loss

Treatment: Chemotherapy (R-CHOP and methotrexate)

...

Laurie A., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Frequent sinus infections, dry right eye, fatigue, lump in abdomen

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radioimmunotherapy

...

Kris W., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Pain in the side of the abdomen

Treatment: R-CHOP chemotherapy

...

Kim S., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptom: Stomach pain

Treatments: Chemotherapy (rituximab & bendamustine), immunotherapy (rituximab for 2 additional years)

...

Jonathan S., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Severe shoulder pain

Treatments: R-CHOP chemotherapy, methotrexate, focal radiation, autologous stem cell transplant

...

John S., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptom: Swollen lymph nodes

Treatments: Clinical trial, chemotherapy

...

Jason W., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Hives, inflamed arms

Treatments: Calabrutinib, Lenalidomide, Rituxan

...

Harjeet K., Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-Cell-Lymphoma (SPTCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Persistent, high fevers; red, tender rashes on legs

Treatments: High-dose chemotherapy, allogeneic stem cell transplant

...

Anna M., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: a rRapidly growing, painless lump on the breast

Treatment: Chemotherapy

...

Erin R., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) & Burkitt Lymphoma, Stage 4

Symptoms: Lower abdominal pain, blood in stool, loss of appetite

Treatments: Chemotherapy (Part A: R-CHOP, HCVAD, Part B: Methotrexate, Rituxan, Cytarabine)

...

Emily G., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Pain in left knee

Treatments: Chemotherapy (R-CHOP and high-dose methotrexate)

...

Emily S., Burkitt Lymphoma, Stage 4

Symptoms: Constant fatigue, tongue deviated to the left, abscess in right breast, petechiae on legs, night sweats, nausea and vomiting, persistent cough

Treatments: Chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, immunotherapy

...

Cindy M., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Itchy skin on the palms and soles of feet; yellow skin and eyes

Treatment: Chemotherapy (R-CHOP)

...

Cherylinn N., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptom: None

Treatments: R-CHOP chemotherapy, rituximab

...

Bobby J., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Fatigue, enlarged lymph nodes

Treatments: Clinical trial of ibrutinib + rituximab, consolidated chemo of 4 cycles of Hyper-CVAD

...

Barbara R., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Abdominal and gastric pain

Treatments: Chemotherapy R-CHOP, CAR T-cell therapy, study drug CYT-0851

...

Ashlee K., Burkitt Lymphoma, Stage 4

Symptoms: Abdominal pain, night sweats, visible mass in the abdomen

Treatments: Surgery (partial colectomy to remove 14 inches of intestine), chemotherapy

...

5 replies on “Pete DeNardis’s Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Story”

With this rather rare for of blood cancer, finding a doctor that is knowledgeable a out it, When I first was diagnosed I went to our local cancer center(Manderson) and was very unhappy with the doctor. I had done my research and knew enough that her recipe did not please me. I called a doctor at Emory since that was the closest(4 hours to Atlanta) and found someone that I liked, BUT that was during Covid(2020) and insurance would allow Teledoc and crossing state lines. I’m still in watch and wait stage, but I fear when I really need someone more often I won’t be able to afford or willing to travel far? Are there any Waldenstrom’s specialists that can cross state lines?

My husband went through the 6 month chemotherapy rituximab and Bendamustine 7 years ago almost 8 right after that he was put on imbruvica and has been on it since going on 7 years. Doing great some fatigue and skin issues and bleeding but mostly doing well. I loved Pete’s story of surviving love seeing 20 plus years makes me hopeful my husband will stick around into his 90s

I was diagnosed with WM 8 months ago and have had IVIG and Rituxan treatments for about 4 months. My doctor is recommending more IVIG and Zanabruitinib for next treatments. I’m anxious and curious about the Zanabruitinib. Has anyone experience with this drug? Side effects, other issues? Thanks for your input.

Thanks so much for this comprehensive account of Pete’s story. I am newly diagnosed with Waldenstrom’s and still in a bit of shock. I am now ready to inform myself and try to get better, gain a few years more with my grandkids.

I was diagnosed with Waldenstorm`s last March, finished 6 months of chemo and immunotherapy. I was treated with Bendamustine and Rituximab and had no problem with either one. My hair thinned out, but didn`t lose it and they made sure that I had no problem with upset stomach. The only true problem I had was constipation, but am in remission now and see my doctor every 6 weeks, very thankful to God for finding this sooner than later, my best to you.