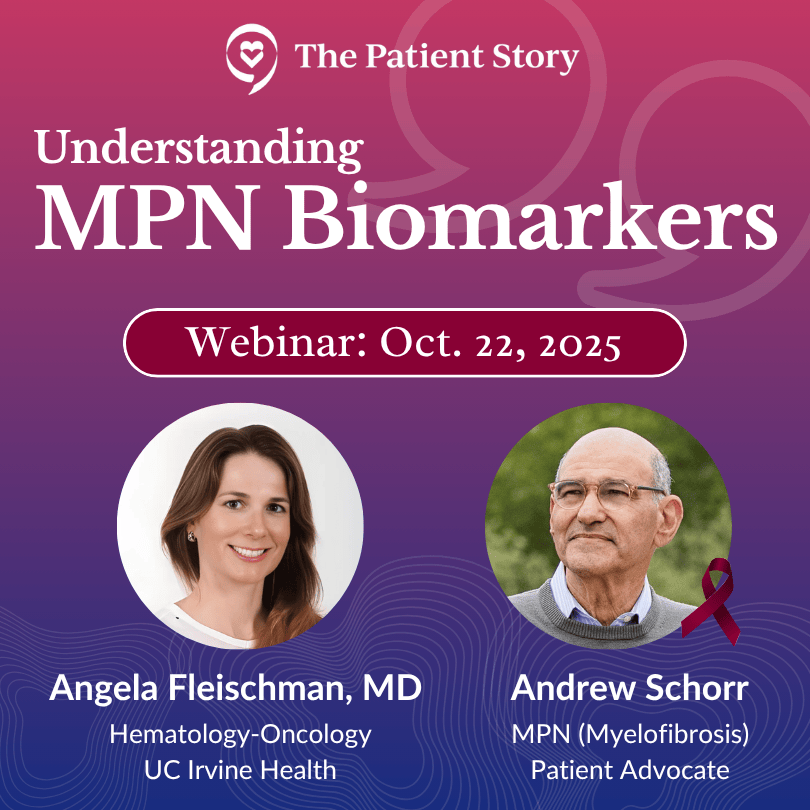

Understanding MPN Biomarkers: JAK2, CALR, MPL and More

What Mutations Reveal About Your Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Options

Biomarkers can be confusing. This program makes them clear. Well-known MPN patient advocate, Andrew Schorr, interviews Dr. Angela Fleischman (UC Irvine) about how common mutations (JAK2, CALR, MPL) help confirm an MPN and what they can (and can’t) predict about symptoms and clotting risk. They discuss when “watch and wait” is right and when to consider medicines like interferon or JAK inhibitors.

You’ll also learn how high-risk mutations (ASXL1, IDH1/2, EZH2) may affect transplant discussions, why results can change over time (clonal evolution), and how NGS is shaping more personalized monitoring. Practical takeaways help you talk with your care team and explore clinical trials with confidence.

Program Topics

- Biomarker Basics: What JAK2, CALR, and MPL show and how blood tests find them

- Treatment Decisions: When watch-and-wait, interferon, or JAK inhibitors make sense

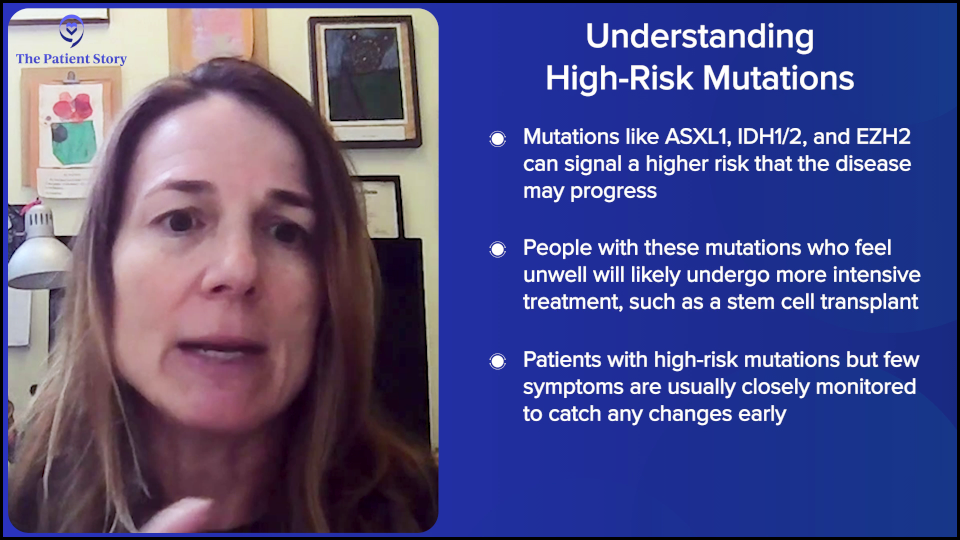

- High-Risk Mutations: How ASXL1/IDH1/2/EZH2 can guide closer follow-up or transplant talks

- Clonal Evolution & NGS: Why results change over time and how sequencing tracks it

- Personalized Care & Trials: Using risk scores (e.g., DIPSS/MIPSS) and clinical trials to tailor options

This program has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

Table of Contents

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

Introduction

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, there! I’m so glad you could join us. This program is part of The Patient Story’s continued commitment to empower you with the information you need to know when your doctor orders blood work or other tests. You may have already have seen our Blood Work Basics series, including part one on complete blood count and part two on the blood tests that are essential to managing treatment for myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). In this program, we will dive deeper into blood work with a look at something that many of you have asked questions about: biomarkers.

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, there! I’m so glad you could join us. This program is part of The Patient Story’s continued commitment to empower you with the information you need to know when your doctor orders blood work or other tests. You may have already have seen our Blood Work Basics series, including part one on complete blood count and part two on the blood tests that are essential to managing treatment for myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). In this program, we will dive deeper into blood work with a look at something that many of you have asked questions about: biomarkers.

My name is Stephanie Chuang. I’m the founder of The Patient Story but more importantly, I’m also a former blood cancer patient. I had lymphoma and I remember how alone I felt and how hard it was to get humanized information that felt relevant and good for me, which is what we focus on at The Patient Story. In the space of a diagnosis like MPN where you have to get tests done regularly, there is a lot that goes along with it, so we build programs like this conversation and hundreds of patient stories, all to amplify your voice.

This discussion features someone who’s been advocating for patients with blood cancers for a very long time and who I’m lucky to consider a good friend: Andrew Schorr. His story is almost three decades in the making. First, he entered a clinical trial for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in 2001. Then he started treatment for myelofibrosis (MF) in 2011. He’s a very passionate advocate, always helping educate and empower other patients, and has been advocating for us at The Patient Story.

We’re also incredibly lucky to have again Dr. Angela Fleischman from UC Irvine, who is so committed to patients beyond her clinic walls, which is evident in everything that she participates in. She’s regularly leading clinical trials to understand what drives MPNs and all of that is to try and develop new therapies to treat or prevent MPNs.

We’re also incredibly lucky to have again Dr. Angela Fleischman from UC Irvine, who is so committed to patients beyond her clinic walls, which is evident in everything that she participates in. She’s regularly leading clinical trials to understand what drives MPNs and all of that is to try and develop new therapies to treat or prevent MPNs.

While we hope that this discussion will be helpful, keep in mind that it’s not a substitute for medical advice, so please consult with your healthcare team about your decisions.

Lastly but importantly, we want to hear from you. Your voice matters. We want to know what we can do to make the experience better. We want to know what you’re looking for, what topics you’d like discussed, which guests you’d like featured, and what has worked well so we know to do it again.

Andrew, I’m going to send it over to you.

Andrew Schorr: I’m Andrew Schorr and I’ve been living with primary myelofibrosis since 2011 and, believe me, I closely follow everything about the characteristics of my illness.

Andrew Schorr: I’m Andrew Schorr and I’ve been living with primary myelofibrosis since 2011 and, believe me, I closely follow everything about the characteristics of my illness.

We’re going to talk about biomarkers and see how biomarkers affect the management and monitoring of MPNs. Joining me is an expert in MPNs from the University of California at Irvine, Dr. Angela Fleischman, who is both a clinician and a researcher. Dr. Fleischman, welcome to our program.

Dr. Angela Fleischman: Thank you, Andrew. It’s always great to see you and talk with you both in person and on these online forums.

Andrew: Thank you. It’s a delight. And we have a lot to talk about.

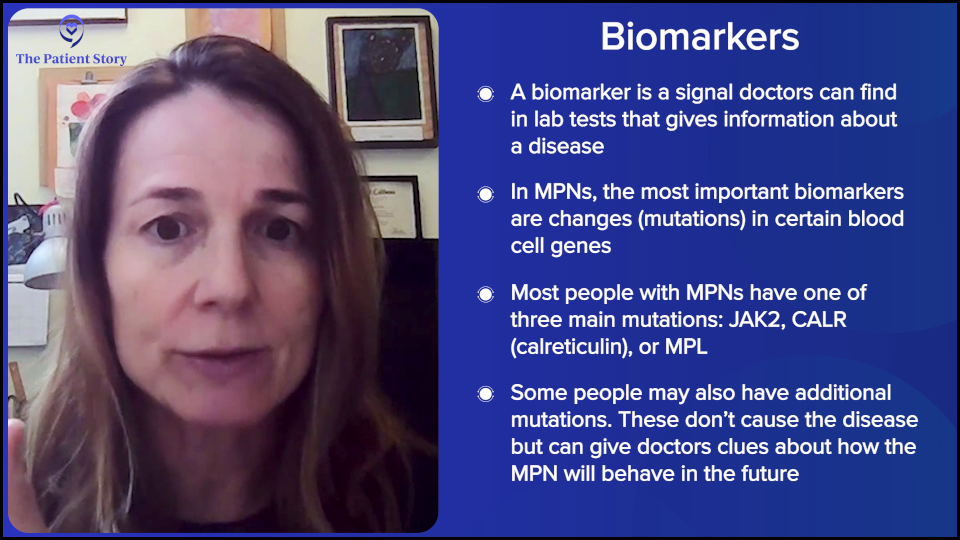

What are Biomarkers?

Andrew: Dr. Fleischman, you’re a hematologist who specializes in MPNs. Let’s understand the term biomarkers. Where do they fit in with helping you give patients the treatment that’s right for them?

Dr. Fleischman: The actual term biomarker could be very broad in terms of something that we can see in the lab that would give us some information about the biology of the disease of a person. In myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), the biomarkers that we use are the mutations.

Almost everyone with an MPN will have one of three driver mutations: JAK2, calreticulin (CALR), or MPL. But MPN patients can have additional mutations on top of their JAK2, MPL, or CALR, which may help prognosticate or predict what their disease course will be.

But as the word says, they’re simply a biomarker. It can help us predict but not necessarily 100% tell the future. It can, however, help us with treatment decision-making as well as how closely we would monitor a patient.

Are We Born with Mutations or Do They Develop Later in Life?

Andrew: Let’s try to understand the word mutation for a minute. From a healthy person to someone who has one of these conditions, did they always have these genes or did they develop and get out of whack?

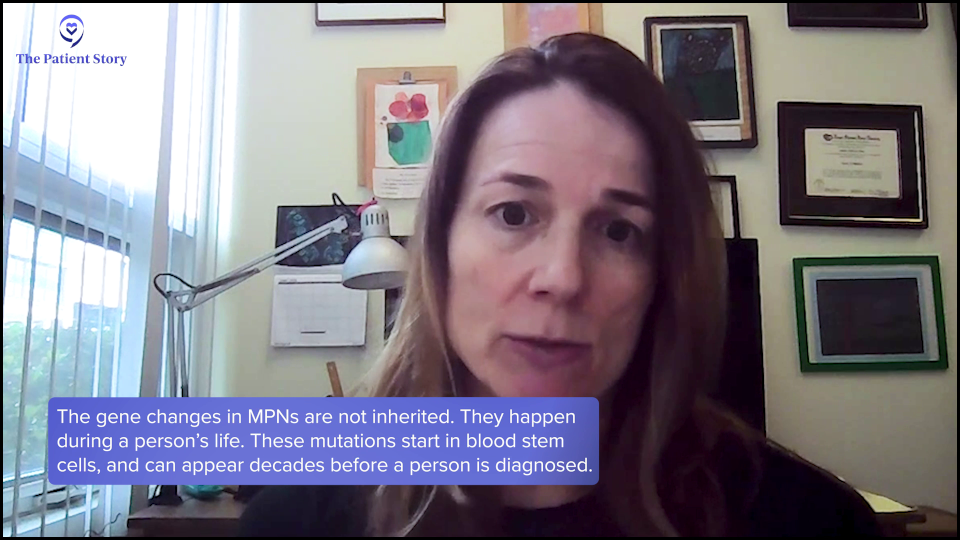

Dr. Fleischman: In a myeloproliferative neoplasm, the genes that we’re talking about are acquired at some point in the person’s life, specifically in blood stem cells. We do know now that a JAK2 mutation is usually acquired about 20 to 30 years prior to someone’s diagnosis, so if you’re diagnosed with an MPN, you probably have been living with these JAK2 mutant cells for years.

A mutation means a change in the DNA, so cells in your blood have this change in the DNA. We know that if you screen the general population for these mutations, including JAK2, a good proportion of an older population will come up with mutations in their blood. It’s a common consequence of normal aging that these cells with mutations expand to a level that we can see them with our testing.

Andrew: Okay. And the mutations cause bad things to happen in the blood?

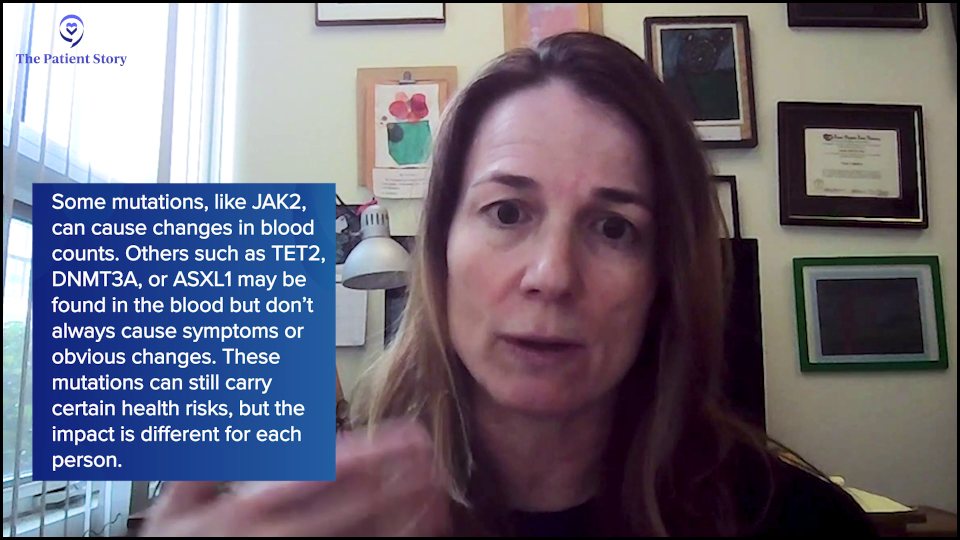

Dr. Fleischman: Not necessarily bad. For example, a JAK2 mutation can cause blood count abnormalities. Yes, that is bad, but they become obvious or viewable by the medical system because they cause abnormalities in people’s blood counts that we can identify.

However, for other mutations that are commonly seen in the general population and in myeloproliferative neoplasms, such as TET2, DNMT3A, or ASXL1, which is the third most common clonal hematopoiesis, those people are walking around with mutant cells in their blood with no real detectable abnormalities in their blood counts. Do you say that’s bad? There can be some negative health consequences of having these mutant cells, but everything’s a spectrum.

What Blood Tests are Used to Identify Abnormalities?

Andrew: JAK2 is typically the most common biomarker and it was identified a number of years ago. JAK2 V617F to be technical. Then a few years later, it was CALR. How do you know what somebody has? What tests do you do to know what genes are in an individual?

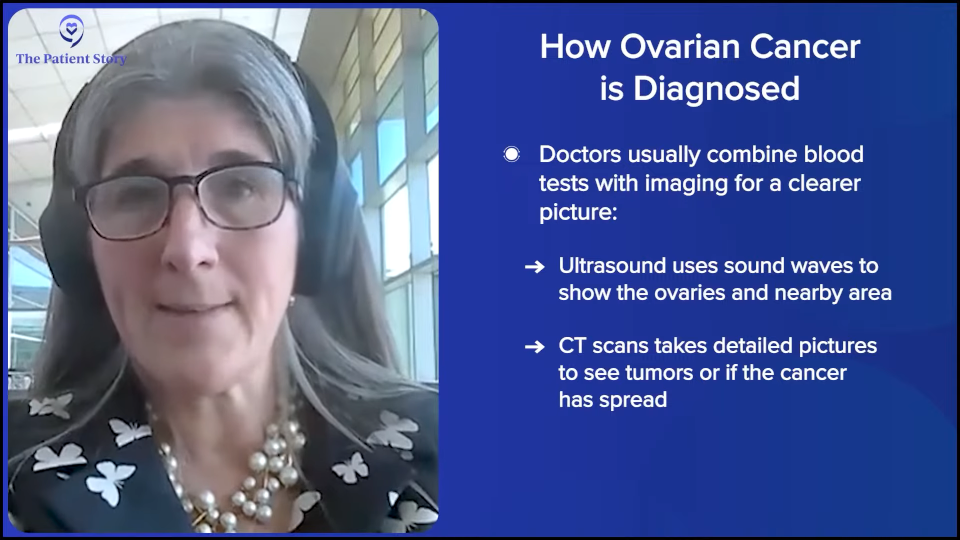

Dr. Fleischman: Usually, if a patient is found to have some abnormal blood count, such as high platelet count or high red blood cell count, the first diagnostic step is to screen for these mutations. Different labs will do it differently in terms of whether they do all of them at the same time or start with JAK2, which is the most likely one. If that’s negative, then they’ll go down to CALR and then if that’s negative, go down to MPL. But at the present time, these are standard tests that are easily available across the US.

Andrew: From a blood test and not necessarily a bone marrow biopsy?

Dr. Fleischman: Correct. The variant blood cells are in the person’s blood, so it’s easy just to take a blood sample and quantify. You can do two different tests. Usually for diagnosis, you want a yes or a no. Is it there or not? But JAK2 can also be quantitative. So if it’s there, what percentage of the cells have that mutation? But usually for a diagnosis, you want a yes or a no answer.

How Do You Decide When to Start Treatment?

Andrew: Then if it’s there, the next question is: do you need to treat it? How do you decide that? If somebody is JAK positive, you have medicines for that now. What leads to saying that the JAK is of such an extent that we need to do something about it?

Dr. Fleischman: There are guidelines called the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.

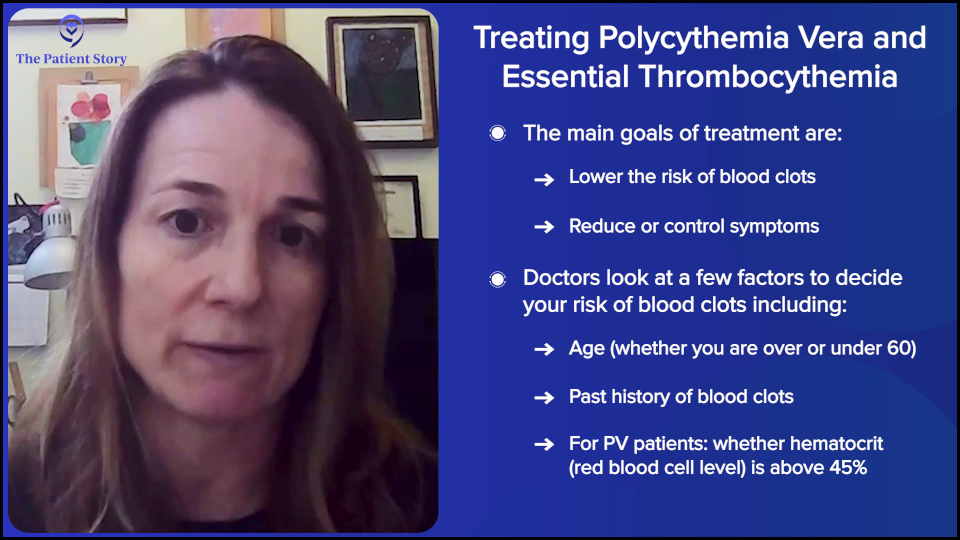

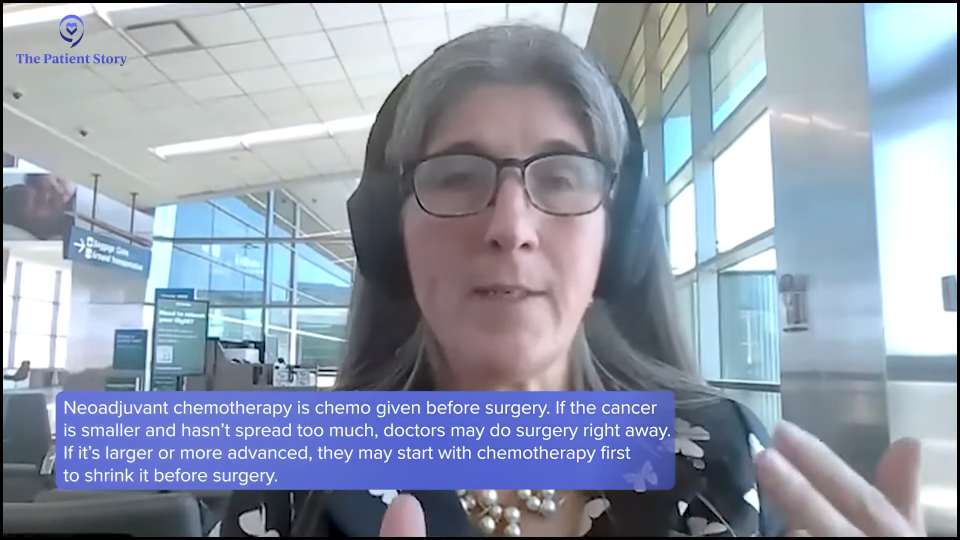

Let’s talk about polycythemia vera (PV) patients first. Our primary objective with what we define as our treatment goals in PV and essential thrombocythemia (ET) are to reduce the risk of blood clots because these patients have an increased risk of blood clot and to improve symptoms.

There are risk categories of blood clotting based on age, whether the patient is older or younger than 60, and whether they’ve had a blood clot in the past. Depending on the risk profile, one can choose different treatments per se.

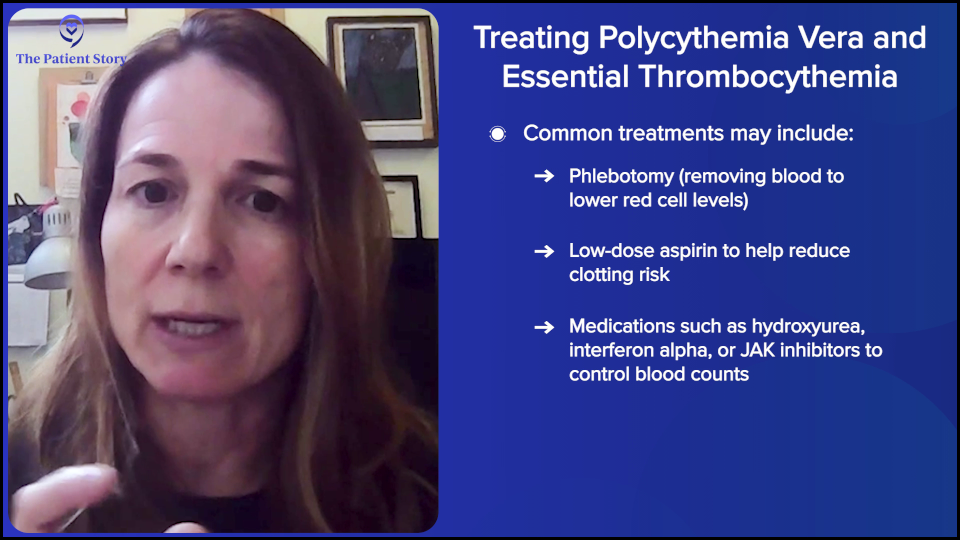

In polycythemia vera, we want the hematocrit below 45 because those people have been shown to have fewer blood clots, so the treatment is however the person can achieve that. Potentially, there’s therapeutic phlebotomy, aspirin, or something to reduce the blood counts like hydroxyurea, interferon alpha (IFNα), or ruxolitinib (Jakafi). It depends on the person’s age, whether they have a blood clot, whether they have an enlarged spleen, or whether they’re symptomatic. It’s very personalized for each person in terms of what they want to achieve.

To be clear, in terms of the JAK2 mutation, although we have JAK inhibitors, none of our treatments that we have reduce the JAK2 percentage of cells — potentially after years and years, but not initially. I want to emphasize that even though there are JAK inhibitors, they do not get rid of JAK2 mutant cells. Realistically, the only drug that we have that can actually bring down the JAK2 cells in a good proportion of patients — in some cases down to zero — is interferon alpha.

Andrew: You’re watching the patient and looking at their situation. Then you may bring in different medicines. Is CALR different? Are there different medicines for that?

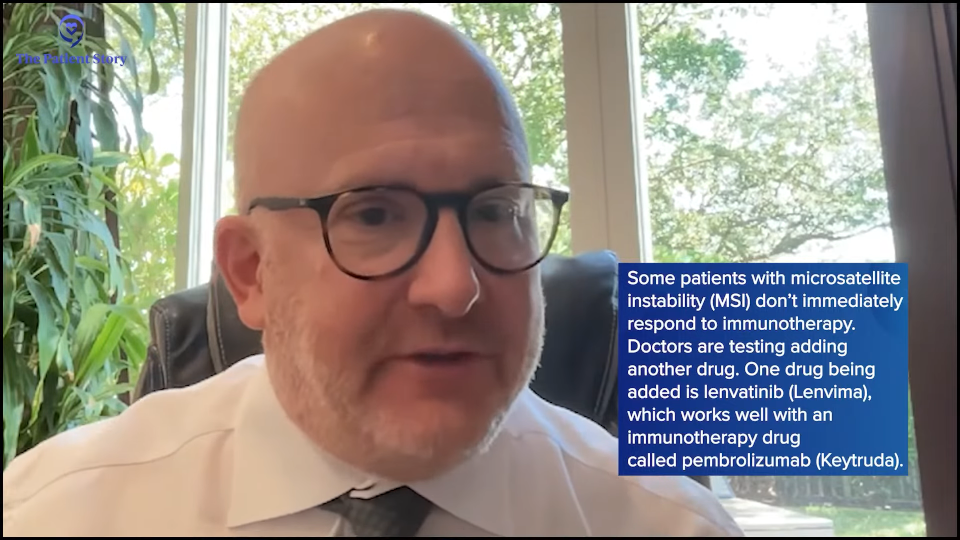

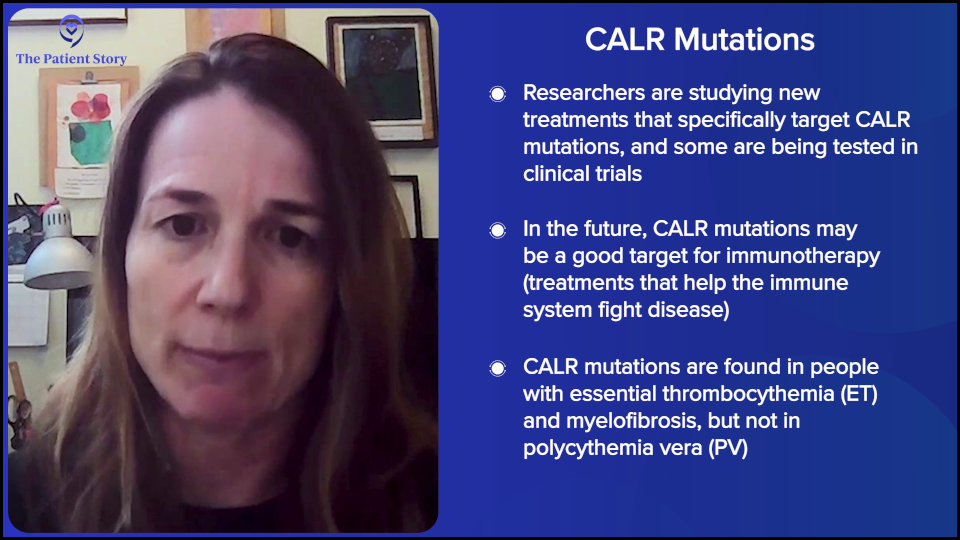

Dr. Fleischman: CALR is a very interesting topic. There are CALR-specific drugs being tested in clinical trials, so at present time, we don’t have CALR-specific drugs on the market that you can get a prescription for. The mutations change the protein such that it looks very different than the normal protein, which is a great opportunity for things like immunotherapy where we utilize our immune system to recognize things that look different than our normal proteins that our body should have.

It’s too early to predict because they’re all in very early stages of clinical trials. But potentially in the future, there could be a whole slew of calreticulin-specific drugs. CALR is never seen in PV. It’s seen in ET and MF.

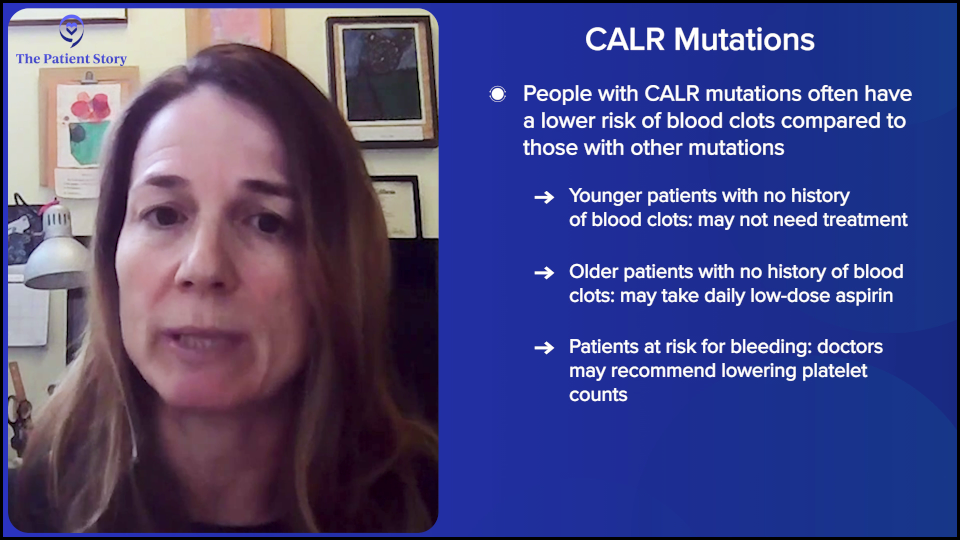

Interestingly, people with the CALR mutation have a lower risk of blood clots. Theoretically, a very young person is categorized as very low risk with calreticulin. If they’re under the age of 60 and haven’t had a blood clot, they don’t even need aspirin — absolutely no treatment whatsoever. Low risk would be somebody over the age of 60, but no blood clot. Those people can just have aspirin.

One thing I want to emphasize, which I feel is the most common misconception, is that platelet count correlates with blood clotting risk. Despite studies, there has been no correlation between platelet count and blood clotting risk. There’s realistically no medical rationale for reducing a platelet count.

The only medical rationale for reducing a platelet count is if the platelet count is super high because it actually causes bleeding. We reduce the platelet count to reduce bleeding, not clotting. Or if the patient is symptomatic from their platelet count, that would be a reason to reduce the platelet count. But the platelet count itself does not correlate with blood clotting risk. I want to emphasize that and I can’t emphasize that more strongly.

Andrew: One quick question. I’ve thought of low platelet count as a bleeding risk.

Dr. Fleischman: Correct.

Andrew: But high platelet counts are also a risk?

Dr. Fleischman: Yes. Because when platelet counts get to over 1,000 or 1,500, they can sponge up your clotting factors. The person can have acquired von Willebrand disease (AvWD), which is usually a genetic disorder where you have defects in your blood clotting. But high platelet counts can basically sponge up those clotting factors that it looks like you have a bleeding disorder.

Andrew: Oh, I’ve never heard that before. There’s one other biomarker we didn’t comment about: MPL. Do we have a treatment related to people with MPL?

Dr. Fleischman: Of the three common mutations, it’s the least common. There are fewer people with MPL-mutated ET or MF. We lump them together in terms of risk in ET as a non-JAK2. We lump CALR and MPL together in terms of criteria for risk, as we say JAK2 and non-JAK2.

Theoretically, they’re treated less aggressively in terms of thrombotic risk compared to JAK2. However, because it’s a less common mutation, we don’t have hordes of people that we can observe and clearly say what their risks are.

Andrew: Dr. Fleischman, over the last few years, you have had these scoring systems — DIPSS (Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System) and MIPSS (Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System) — where you can put in a patient’s situation and their biomarkers, and have some picture of where they are and where they may be headed. Are these routinely used? What is the impact of these scoring systems?

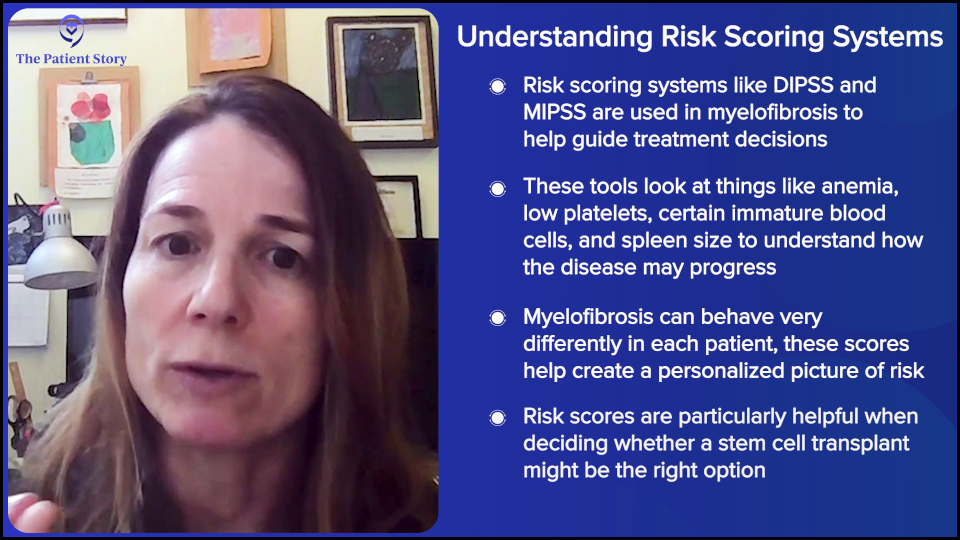

Dr. Fleischman: Yes, it is routinely used in particular for somebody with myelofibrosis, which can have a wide range of expectations in terms of what the disease trajectory would be and the prognosis. It’s important if you’re diagnosed with myelofibrosis.

One myelofibrosis patient can be extremely different from another based on their risk factors. For example, somebody with very mild anemia, their white blood cell count looks fine, nothing abnormal, and don’t have an enlarged spleen, that person is very low-risk. It’s going to be different for somebody who has transfusion-dependent anemia, very low platelet counts, or have blasts in their blood. You’re going to have very different situations between those two patients.

These risk scoring tools help us assign points for each hit against the person, like bad anemia or blasts in their peripheral blood, and allow us to have a scoring tool that helps us predict the person’s outcome.

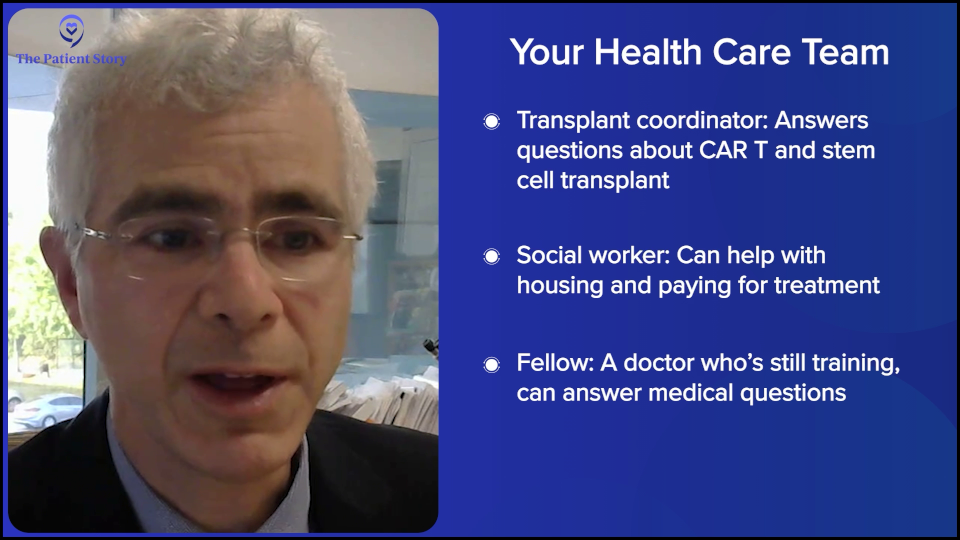

It’s probably most important with the decision on transplant. Transplant is the only cure for a myeloproliferative neoplasm, but it’s a difficult procedure and comes with significant risks. We don’t want to give a person a treatment that could make them worse off than they are from their underlying disease. That’s why it’s important for us to predict how bad the disease is going to be or how quickly it’s going to progress to a serious situation to help us determine if it’s worth the risk of a transplant now or not.

There are obvious things, like if the person is anemic, that the patient can realize that it’s a bad situation if they need transfusions. But other things that we may not be able to see from our general labs, such as genetic tests, are the additional mutations, which may portend a higher risk. Those are very beneficial in helping to predict what may happen to a person later on that may not be clearly obvious from their outward clinical situation.

Andrew: We mentioned ASXL1 in passing and it’s supposedly a higher risk mutation. Is that an example?

Dr. Fleischman: That would be an example. ASXL1, IDH1/ 2, and EZH2 are genes that would make a physician concerned that the patient would have a higher risk of progression. How to address a higher risk mutation in somebody who clinically looks pretty good is a little bit of a conundrum.

If you have somebody who looks clinically very ill and has high-risk mutations on top of that, that makes the decision easy to say that this person needs a transplant because there are a lot of things that are quite concerning about this person’s situation that makes us worried. This person may be on their way to getting a leukemia.

However, if the person looks clinically very well in terms of their blood counts looking good and feeling well, yet they have some high-risk mutations, it’s a bit of a more difficult situation. You have some data that makes you think that something isn’t quite right, but by looking at them, they look very healthy and look good. That’s a tough situation.

In those situations, it’s a personal decision for the patient. What usually can occur is they’re watched extremely closely. We have some information that something might not be right, but we need a little bit more information that something isn’t going well in this person. We’re going to closely monitor and see if we get other clues that something is moving in the wrong direction. Again, you don’t want to put too much weight on one specific piece of data. It’s more of a whole picture.

Understanding Clonal Evolution

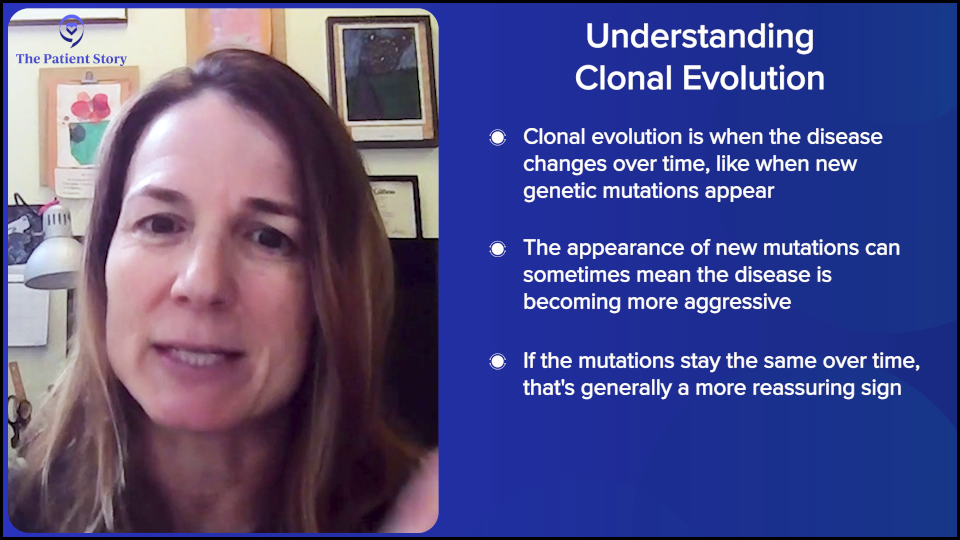

Andrew: There’s a term that comes up called clonal evolution. Where does that come into play? In other words, if at the outset of a diagnosis, you see JAK2 and don’t see all the other stuff, but now you’re following somebody for an extended time and then when you do a blood test, ASXL1 or one of these other ones come up. Am I right that this stuff can pop up or can change?

Dr. Fleischman: That’s the definition of clonal evolution. Things are changing over time. That’s also helpful in terms of prognostication. If you had just JAK2 to begin with and then you’re developing another mutation — for example, ASXL1 — and some other clinical features are coming with it that are concerning for progression, then you’re getting information that the disease is moving in a different direction.

Whereas five years before, they had the same mutation and it hasn’t changed. Things are looking pretty stable. It’s sort of common sense. If you see things moving and changing, that’s probably not a good sign. If new mutations are popping up, particularly if they’re high-risk mutations, then that’s likely not a great sign in that the disease is moving in a direction that you probably don’t want it to be moving in.

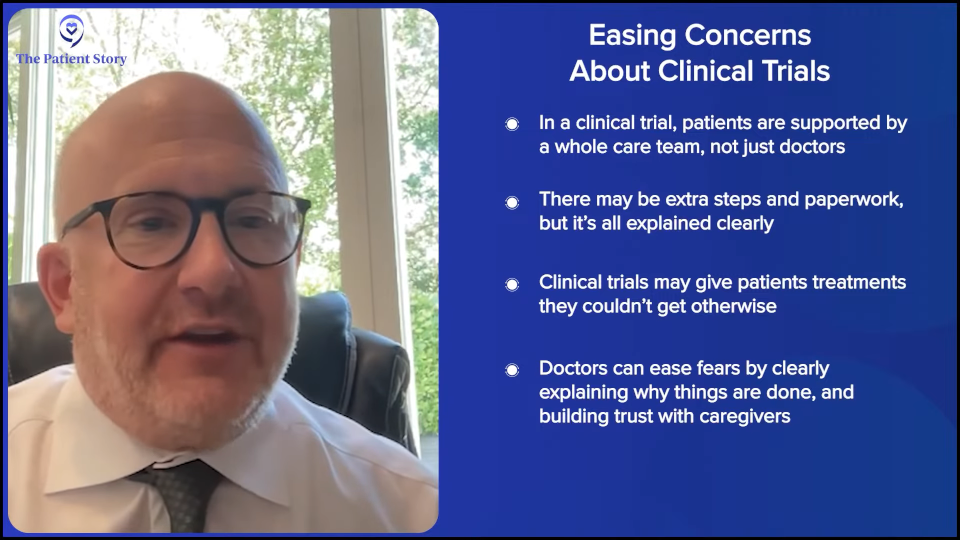

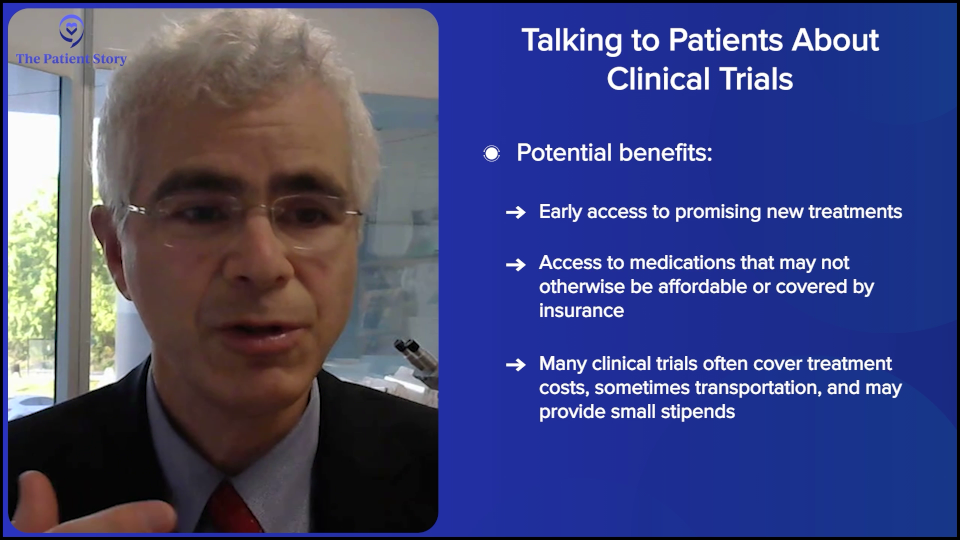

Talking to Your Doctor About Clinical Trials

Andrew: Happily, based on your research and those of your peers around the world, research and clinical trials have been moving forward.

Dr. Fleischman: Correct. Yes.

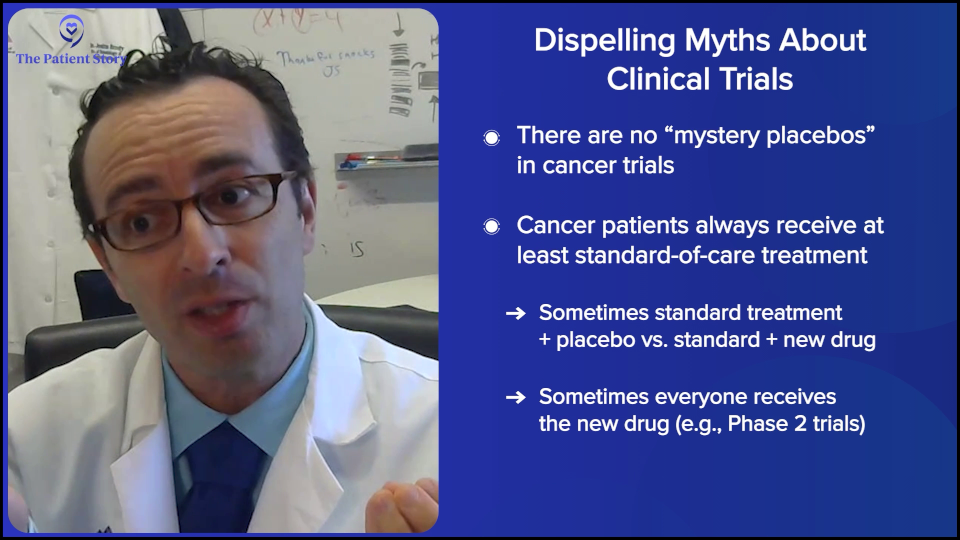

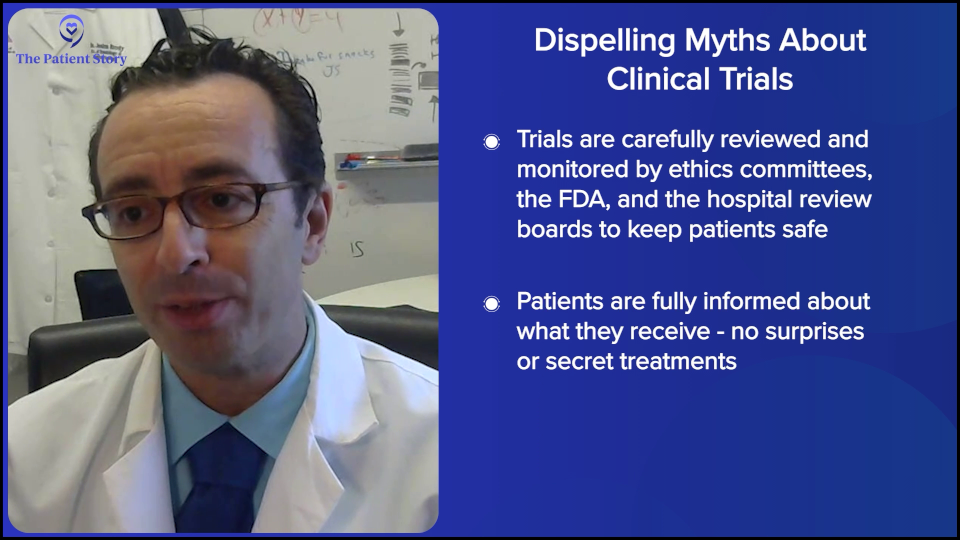

Andrew: As you see a change in patients, is it appropriate for the patient to discuss clinical trials with their physician as to whether they apply to where their change is headed? Like when you talked about CALR medicines or MPL medicines.

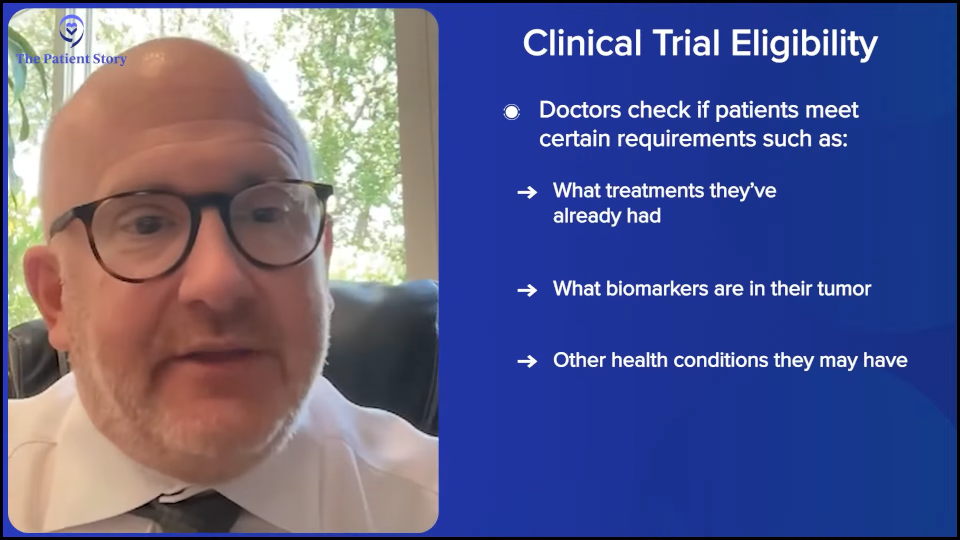

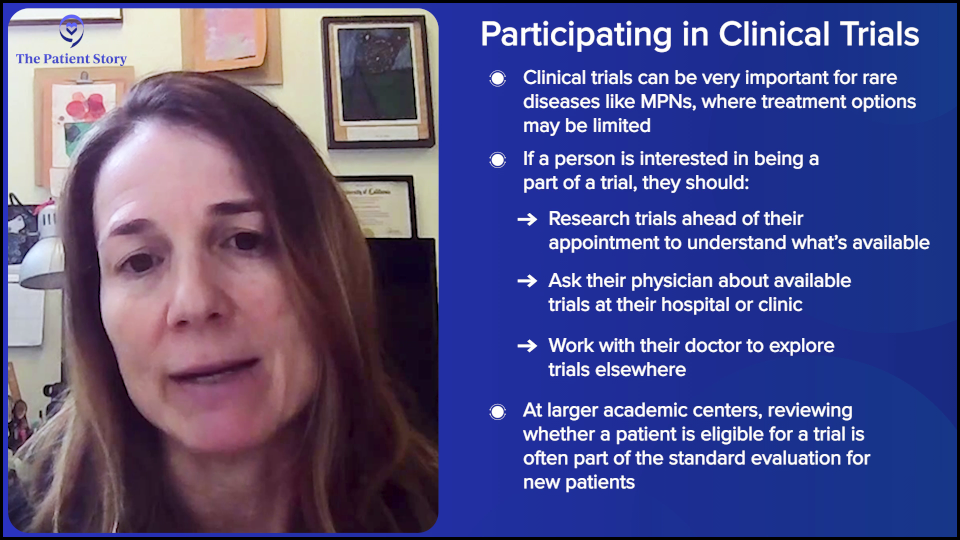

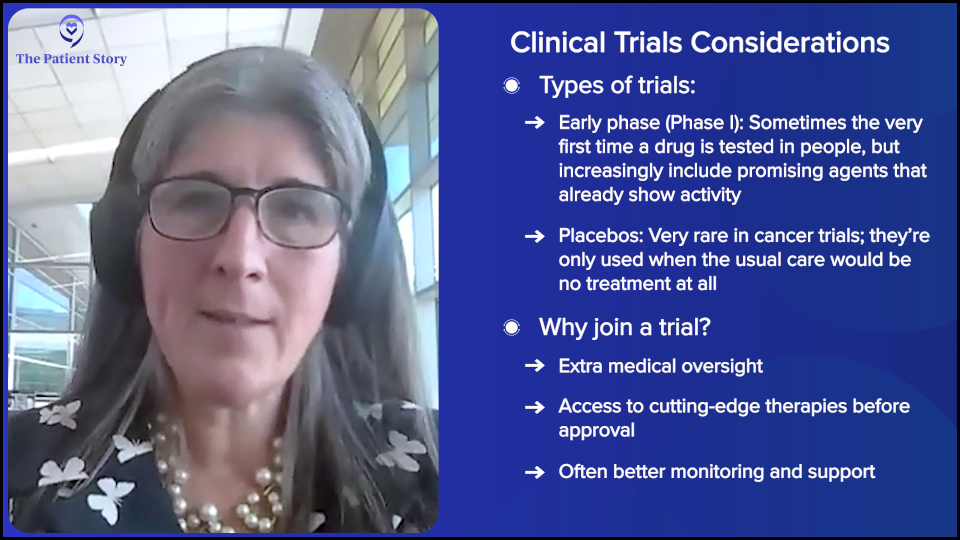

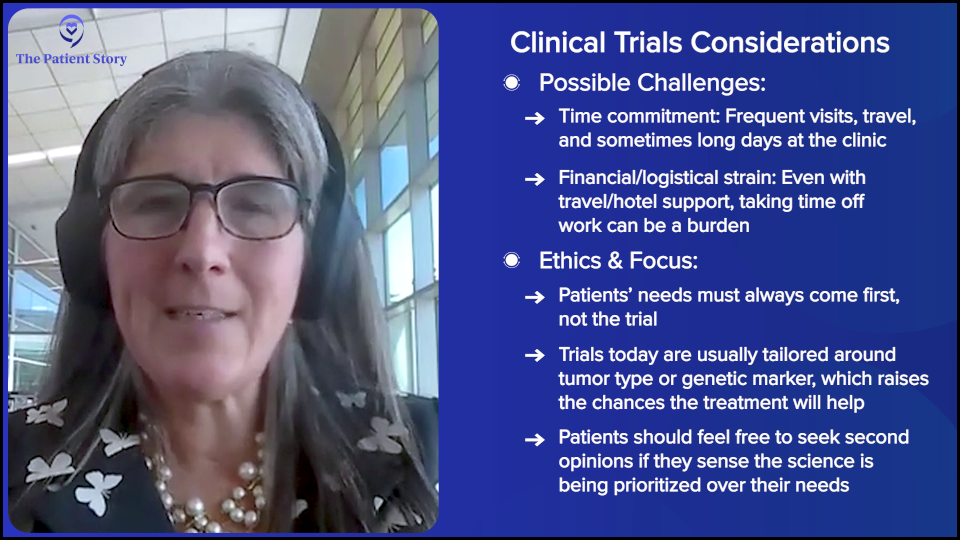

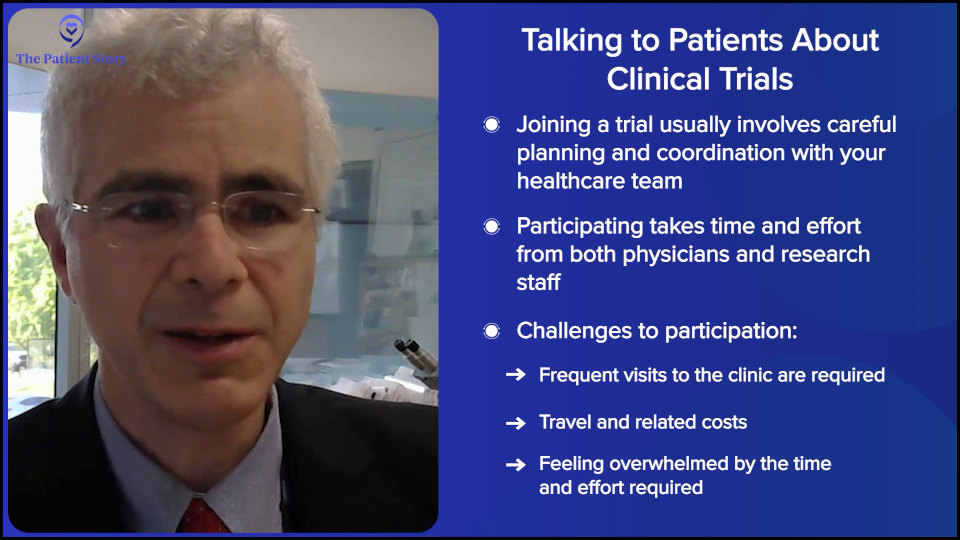

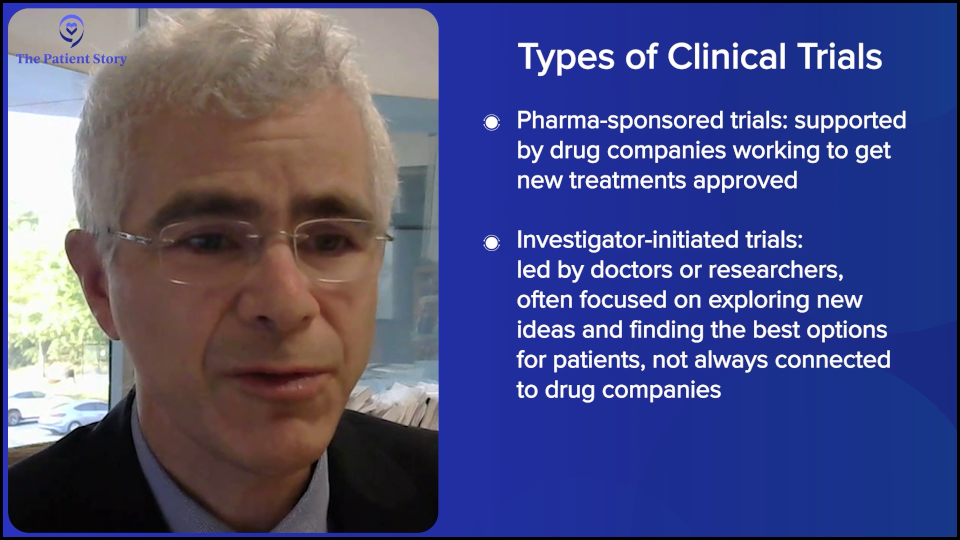

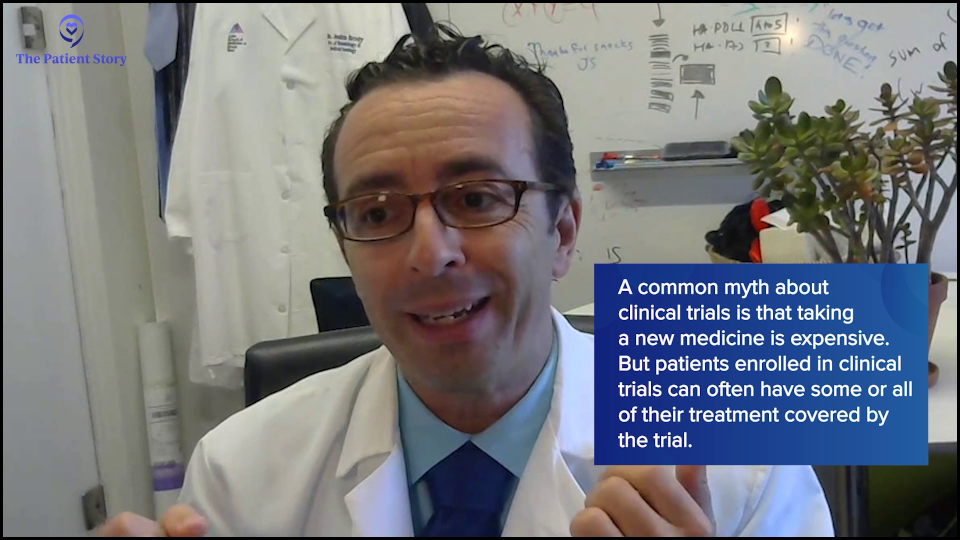

Dr. Fleischman: Yes, it’s very appropriate and important, particularly in rare diseases where we need clinical trials in order to come up with new treatments.

Each person is different. Every patient is not required to be on a clinical trial. If your interest is not in clinical trials, you don’t have to join. But if there’s an interested patient, it’s very appropriate for the patient to research online before they visit their doctor and bring a printout to discuss. Or if they’re at a large university, they can ask the physician what clinical trials they have available for their scenario, whether at their institution or elsewhere.

Usually at large institutions, it’s built in, particularly when a new patient is evaluated. They’re looked at while thinking what clinical trials they’re eligible for. But given that this is a rare disease, it’s important that patients participate to help develop the treatments of the future.

Andrew: Right. And this is an ongoing discussion. You talked about when they’re newly diagnosed. But with clonal evolution, maybe they’ll have the discussion a few years later if things have changed.

Should I Get Tested for Biomarkers Over Time?

Andrew: Which brings us to monitoring. As we have blood tests as patients, you’ll be looking at biomarkers over time, right?

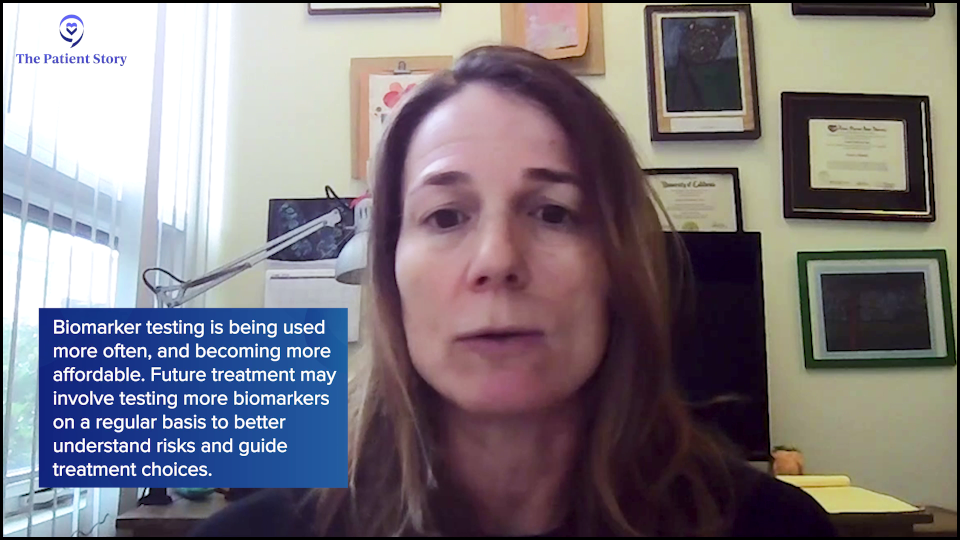

Dr. Fleischman: Correct. What’s exciting is that sequencing, meaning detection of the mutations, is becoming more and more economical and widespread. Realistically, around five years ago or even 10 years ago, if you had a bone marrow biopsy, you wouldn’t have next-generation sequencing (NGS). You wouldn’t know your mutational profile. It wasn’t widely available and quite prohibitive in terms of cost.

But with costs coming down, it’s incorporated into general bone marrow biopsies. Because we can identify most of these mutations in the blood or probably all of them in the blood, one could envision in the future that you could go in at a specific frequency, but maybe not as not as frequent as a complete blood count (CBC). At some sort of routine frequency, mutational analysis could be done to see if that may predict changes before we would identify any changes in your CBC.

In some places, serial screening of the mutational profile is routine, but it’s still too expensive for general medical care. But maybe in the future, as things get cheaper, that will become standard.

But with costs coming down, it’s incorporated into general bone marrow biopsies. Because we can identify most of these mutations in the blood or probably all of them in the blood, one could envision in the future that you could go in at a specific frequency, but maybe not as not as frequent as a complete blood count (CBC). At some sort of routine frequency, mutational analysis could be done to see if that may predict changes before we would identify any changes in your CBC.

In some places, serial screening of the mutational profile is routine, but it’s still too expensive for general medical care. But maybe in the future, as things get cheaper, that will become standard.

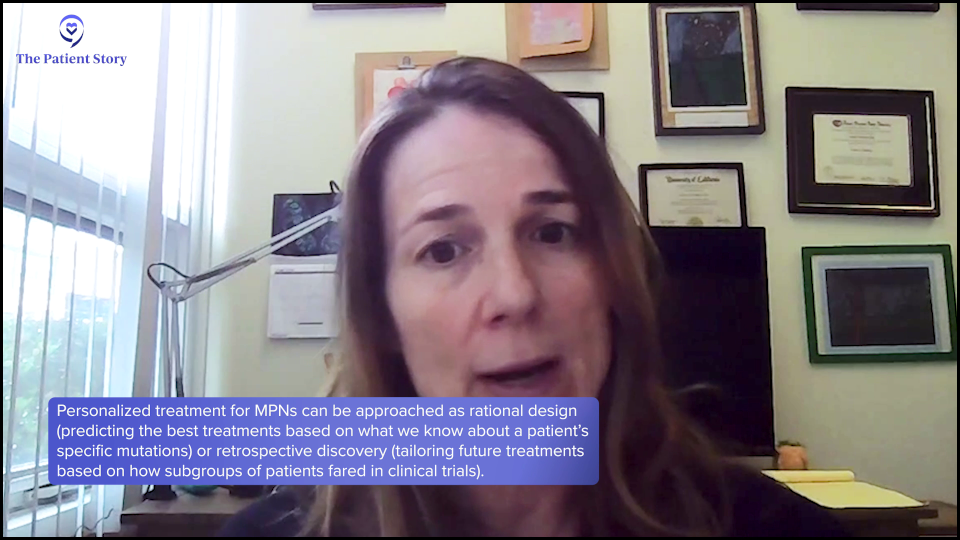

Developing More Personalized Treatments

Andrew: Dr. Fleischman, you’ve been at this for a few years and work hard on this. Are you encouraged by the direction that things are going as far as your ability to give personalized medicine based on the biomarkers and the other input you have for what’s right for an individual patient?

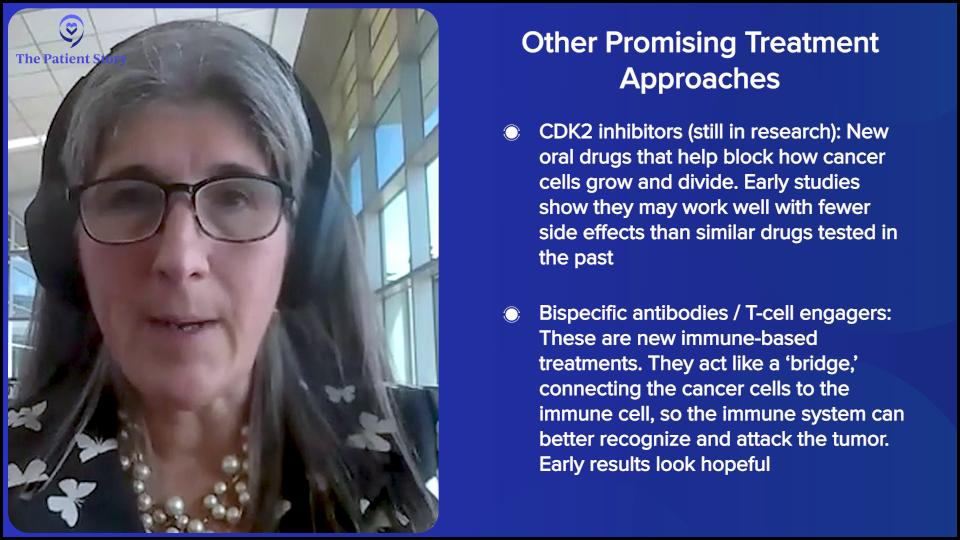

Dr. Fleischman: I think so, yes. We can get at that through multiple ways, particularly through clinical trials. You could rationally think. If this person has a mutation, biologically, we know what this mutation does, so let’s try to design treatments around that or predict what treatments might be helpful for a person with this particular mutation.

Another approach, which may be a little bit less direct but a more luck-based, would be in clinical trials. In most cases, we’ll take patients with all mutations. Retrospectively, you could say, “We enrolled 200 patients into this study and found a subset where the drug was perfect for these people. Did those people have a particular mutation? A group of people did well or a group of people didn’t do well. What was different about the people who did well?” You could identify things that way.

Should Patients Ask Their Doctors About Biomarker Testing?

Andrew: When a patient comes to see their MPN specialist, should they ask, “How’s my biomarker?” Or should they ask, “Based on my biomarker and other input you’re getting, how am I doing?” How would you evaluate it? It sounds like it’s a constellation, with biomarkers being part of it.

Dr. Fleischman: Correct. With regard to the JAK2 allele burden, we don’t know its clinical relevance, whether or not a rising JAK2 allele burden is bad. There are certain things associated with an increased JAK2 allele burden, such as the risk of blood clots. But realistically, with regard to progression, we don’t know what to do with the percentage number of the JAK2 allele burden. If it’s going up, we don’t know what to do with that.

So why test it in the first place? I don’t know why, but for some patients, particularly if they’re on interferon for the purpose of reducing their JAK2 allele burden, it would be a reason to check. If the stated purpose is to reduce the JAK2 allele burden, you’d like to know if it’s doing that.

The Future of MPN Research

Andrew: I wanted to make an analogy. You probably remember the famous hematologist, Dr. Kanti Rai, who was an expert in another condition. I have CLL — and this goes back years — and he talked about the knowledge or the indications of different signals they were getting in the disease. We talked about it like furniture in a room and how we didn’t know where to place the couch, the armchair, and the other stuff.

It sounds like with MPNs, you’re getting a lot of furniture and signals about things, but as you just said, we don’t know. But that’s happening. You also mentioned the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). I’m on a panel for that and, folks, that’s where experts like Dr. Fleischman from different institutions from around the country get together and put their heads together to come up with guidelines for treatment. I think that’s very exciting how the collegiality is going on in MPNs where you’re trying to figure things out together. Wouldn’t you agree?

Dr. Fleischman: I love being part of the MPN community. We’re all working together for a central goal, which is to improve the lives of patients living with MPN. Although we have good treatments today, we have a long way to go. There are a lot of improvements that can be made, which is why it’s so exciting to be in this field. We have hope. We’ve already made some good strides, but there’s so much more work to do. It’s satisfying to know that potentially, we can make some good impact in the future.

Andrew: Right. But as you pointed out, particularly related to clinical trials, patients are in partnership with specialists, such as yourself, whether it’s clinical trial participation or active dialogue on our situation and what’s right for us. We’re partners in this and hopefully for over many years.

Conclusion

Andrew: Dr. Fleischman, thank you so much for your time in helping us understand biomarkers and where they can fit in in this ongoing, personalized treatment for MPNs.

Dr. Fleischman: Thank you very much. As always, it was great to talk with you. The time just flew. You are so great to talk to, so thank you.

Stephanie: Thank you so much to two tireless patient advocates, Andrew Schorr and Dr. Angela Fleischman from University of California, Irvine, for this discussion. Thank you for helping us to break down what could be a very complicated topic and making it understandable.

We want to keep this discussion going. We want to hear what you enjoyed and, more importantly, what we can do even better. What educational programs and what kinds of patient stories are you’re looking for?

Thank you so much for joining. We hope that you’re able to walk away knowing more and feeling more empowered in your care. We hope to see you at another program soon. Thank you and take good care.

Introduction

Introduction

Dr. Kathleen Moore: Thank you for having me. I’m very excited to be here. What drives me and a lot of us who do clinical research for patients with cancer comes from respecting the accomplishments that have happened over the last few decades across hematologic and solid tumors. We’re grateful for those, but we know, especially in the ovarian cancer space, that we have a long way to go.

Dr. Kathleen Moore: Thank you for having me. I’m very excited to be here. What drives me and a lot of us who do clinical research for patients with cancer comes from respecting the accomplishments that have happened over the last few decades across hematologic and solid tumors. We’re grateful for those, but we know, especially in the ovarian cancer space, that we have a long way to go.

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, there! I’m so glad you could join us for our discussion.

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, there! I’m so glad you could join us for our discussion.

Dr. Joshua Brody: Oh, you said this is going to humanize me and though this is going to make me sound like a saint, those who know me, like Amir, know it’s not true. There are things you could help people with. You could help people with all kinds of problems. But cancer just sometimes seems like the most unjust thing. People did everything right. They didn’t do anything bad. They were healthy. They tried everything. They have a family. They worked so hard. And then they get struck down seemingly out of nowhere.

Dr. Joshua Brody: Oh, you said this is going to humanize me and though this is going to make me sound like a saint, those who know me, like Amir, know it’s not true. There are things you could help people with. You could help people with all kinds of problems. But cancer just sometimes seems like the most unjust thing. People did everything right. They didn’t do anything bad. They were healthy. They tried everything. They have a family. They worked so hard. And then they get struck down seemingly out of nowhere.

I’d like to welcome Dr. Steinberg for being here. This is the first time we’re able to meet you and we’re happy to. Speaking of humanizing, you have many personal reasons why you’re in the work that you do. I read a poem about how it affects us all and it details a lot of your connection to cancer, including your own. Could you share a little bit about that connection and how that’s motivated you to do what you’re doing today?

I’d like to welcome Dr. Steinberg for being here. This is the first time we’re able to meet you and we’re happy to. Speaking of humanizing, you have many personal reasons why you’re in the work that you do. I read a poem about how it affects us all and it details a lot of your connection to cancer, including your own. Could you share a little bit about that connection and how that’s motivated you to do what you’re doing today?

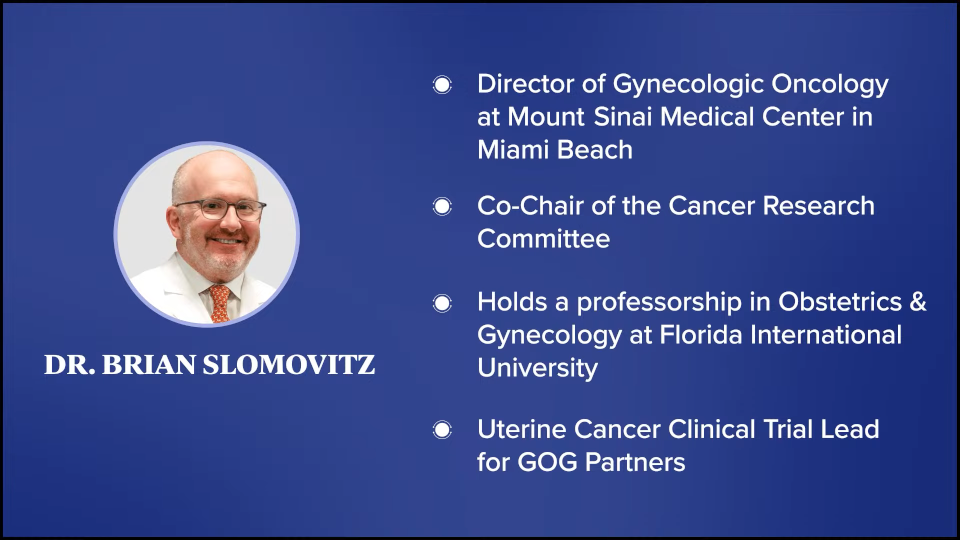

Dr. Brian Slomovitz: Thank you very much for having me. I appreciate the opportunity, Stephanie, to chat with you and

Dr. Brian Slomovitz: Thank you very much for having me. I appreciate the opportunity, Stephanie, to chat with you and