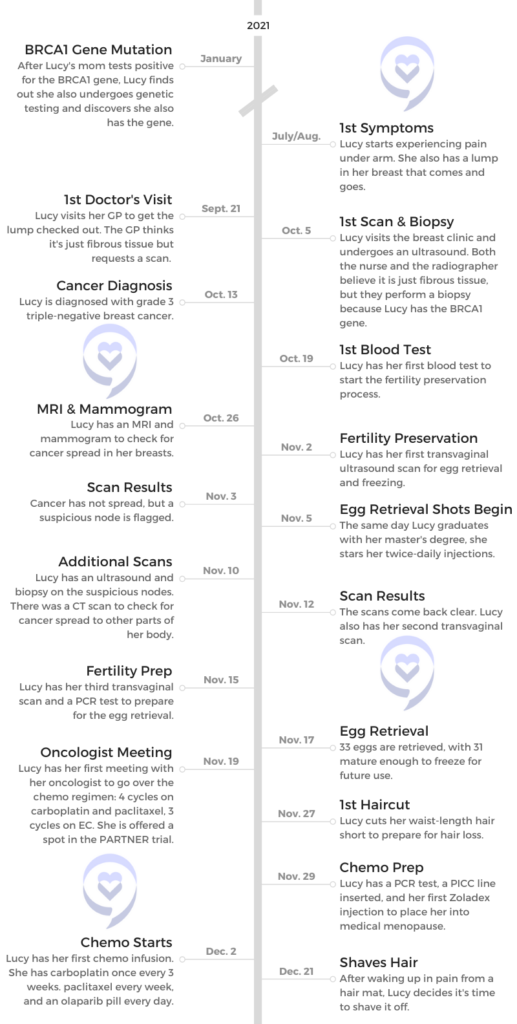

Lucy’s Grade 3 Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Story

Lucy was diagnosed with breast cancer only 3 days after her 24th birthday.

Following Lucy’s mother’s second breast cancer diagnosis, both Lucy and her mom found out they had the BRCA1 mutation.

Lucy developed a lump in her breast the same year she found out she carried the BRCA1 gene. Although her doctors thought it was likely only fibrous tissue, Lucy advocated to keep pushing for tests. A biopsy revealed the lump was grade 3 triple-negative breast cancer.

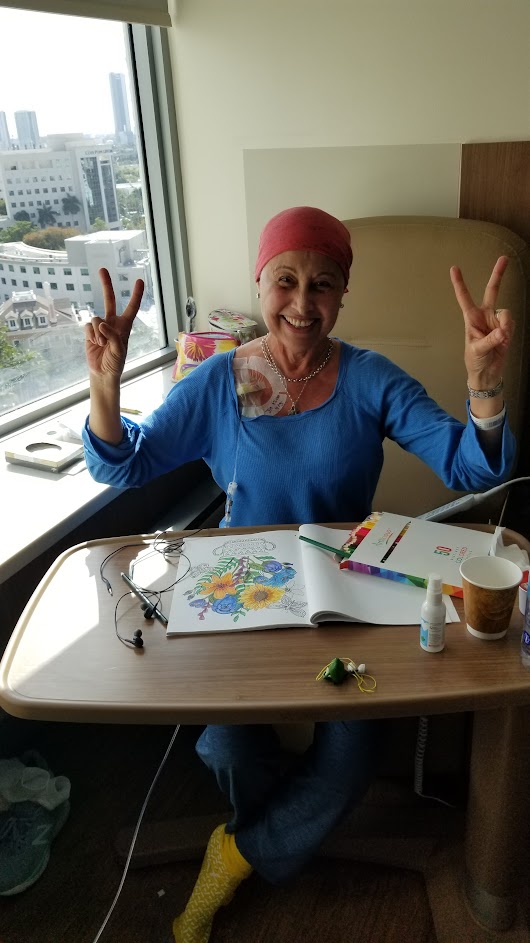

Lucy then underwent fertility preservation, a clinical trial, chemotherapy, and a double mastectomy. Lucy shares processing the diagnosis, navigating hair loss and side effects, and finding support through her journey.

- Name: Lucy E.

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Breast cancer

- Grade 3

- Triple negative

- Stage 2/3

- Age at DX: 24

- Tests for DX:

- Ultrasound

- Biopsy

- 1st Symptoms:

- Lump in breast

- Treatment:

- Egg retrieval

- Chemotherapy

- Regimen 1

- 4 cycles

- Carboplatin every 3 weeks

- Paclitaxel weekly

- Olaparib, a daily pill

- Regimen 2

- 3 cycles

- Epirubicin every 3 weeks

- Cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks

- Regimen 1

- Double mastectomy

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Pre-Diagnosis

Introduction to Lucy

In October I turned 25. I came to the University of Worcester to do English literature as my undergraduate degree. I fell in love with the place, so I stayed in Worcester, and I carried on to do my English master’s. I carried on to do that, and I actually graduated the month after I was diagnosed.

Obviously reading is a big part. That’s why I love the place and Worcester itself and the surrounding areas. There’s just so much history for literature involved. It’s a great place for me to have done my degree.

Before my diagnosis, I was a really big gymgoer. I’d recently started getting into the gym and going a few times a week. [I was] getting into running, which I used to hate, but I found I really loved it. That all changed with my diagnosis as well.

I largely loved going out exploring, going for walks, [and seeing] new places with my boyfriend. We often went to Wales a few times. We just loved exploring the surrounding areas and going for days out places. I loved just going on adventures and things like that.

I was playing the piano as well. Being at uni and staying here, I’ve not been able to do that as much, but when I go home, I love picking it up and trying to get back into it wherever possible.

Doing a degree, I found it hard to get into the reading now. When you’re kind of forced to be told what text you do, it kind of takes the fun out of it. I was part of a book club for a while. Obviously, life got in the way for my uni group and things. We’ve not carried that on [in] a while. I’m trying to find my love of reading again and get back into that as much as possible.

BRCA1 gene

My mom was diagnosed in 2019 for a second time with breast cancer. It’s then when she found out she had the BRCA1 gene. Knowing that it can be inherited 50-50 chance, I thought I want to know straight away whether I’ve got it.

I think it was actually December 2020 [when] I had the blood test, and I found out January 2021. I received the results I had inherited the BRCA1 gene. I was due to start preventative measures — so annual scans, MRI scans — when I turned 25.

What was the plan from the doctors?

I hadn’t started any scans yet because I was only 23 when I found out. I just had the blood test, and I’d had a call with a genetics counselor and a breast nurse. The only thing was, obviously, [to] tell me things with my lifestyle, exercise, [and] keep an eye out. I was on the combined contraceptive pill, and they just warned me to come off that and change to the mini pill instead. Until I turned 25, it was just be aware of myself and just monthly checks really.

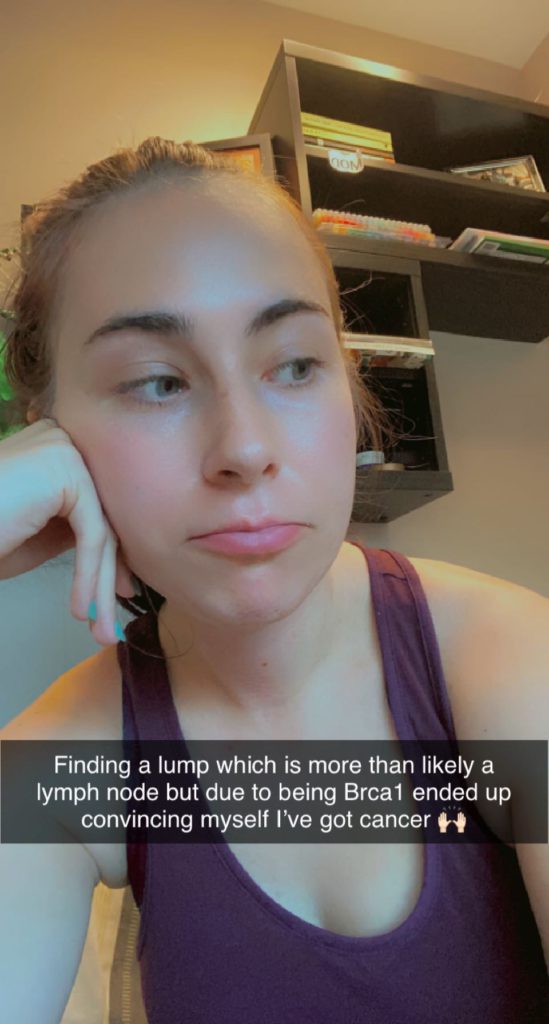

Finding a lump

Around 2021, July [or] August, I started to feel a bit of a lump. It went and it kept coming back, and I thought, “Is it because I’ve now started doing more things at the gym, such as lifting? Is it something to do with that?”

I was keeping an eye on it. I noticed something at the other side that kept coming and going as well. That happened for around 2-3 months. [I] didn’t really think too much [or] anything of it.

It was just a lump. Slight pain, but not too much. It didn’t really feel like what a typical cancer lump feels like. Around September, [the lump] had been there a bit longer than usual. When [my boyfriend] gets ill, he actually gets swollen lymph nodes. I said to him, “Do you mind just feeling it? Does this feel like what your lymph node feels like?”

Normally, he’s [like], “I’ll just keep an eye on. It’s fine.” But he said, “No, Lucy, that doesn’t feel like it. You should tell your mom. Get your mom to feel it and get it checked at the doctor.” With him saying that, I thought, “I’m on something. It’s not right.”

The next day I got my mom to check it. We thought it doesn’t feel like a cancerous lump, but obviously being high risk, having a 60 to 90% chance or higher chance of getting breast cancer, I thought, “I need to ring the doctors.” The next day, I rang the doctors.

Advocating for an appointment

[The doctors] were still doing a lot of telephone appointments, so I called. When I called, I said, “Can I have an appointment with the doctors?” They said, “Well, it’s only telephone appointments.”

I was like, “I found a lump. I need to see them.” She was like, “Okay, well, we can do it in whatever time.” I made sure to tell them, “I am high risk. I have got the BRCA gene.”

She said, “Okay, yes, you need to be seen.” She got me in for a few days later. I managed to see a doctor, and she checked it over. She didn’t think it was anything. She just thought it was fibrous tissue as well [and] didn’t think it felt like a cancer tumor.

You can’t be too careful being high risk. They sent in a request for me at the hospital at the breast unit, just to have a scan and be checked over. That came within 2 weeks. Then I went to the breast unit [and] was checked over by the nurse initially. She thought it was fibrous tissue, but I still had a scan.

Then he didn’t think it was anything. An ultrasound. He didn’t think it was anything to be worried about. On a scale of 1 to 5, he measured my scan at number 3, which is slightly abnormal, but nothing unusual and to be too worried about. But they did say because I’m BRCA1, they will take a biopsy. Luckily they did. Thank God they did take a biopsy.

Diagnosis

The breast cancer diagnosis

They told me I would get the results back [in 7 to 10 days], and the nurse told me it would be probably her or her other colleague, a nurse, that would give me my results.

It was the Tuesday or Wednesday I had that, and then on the Monday, I got a call from the nurse saying, “Can you come in on the 13th? The surgeon wants to speak to you.” Hang on, it’s supposed to be the nurse that was speaking to me to give me my results. It’s now the surgeon. It can’t be good news.

Of course, you do whatever you can. There’s that slight bit of hope, “It is fibrous tissue, but he just wants to talk about getting it surgically removed.” Yes, 3 days after my 24th birthday, I was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Were you expecting it to be breast cancer or nothing serious?

It was promising. I was trying to think, “Well, multiple medical professionals, like 3 medical professionals, have thought [it’s fibrous tissue].” I didn’t feel my mom’s cancer lump when she had hers, so I couldn’t really compare. My mom didn’t really think it was too [similar[, I don’t think

From what I can remember, my dad didn’t think it was similar to my mom’s. Of course, I was trying not to get my hopes up that it is, but of course, you’ve got that slight bit of hope.

Until I had the results, I was trying not to think too much of it. I think I had this feeling, especially since I had the call from the nurse saying the surgeon wants to see you. Especially since that, I had this feeling it’s cancer. Why else would you want that?

What if you hadn’t gotten that biopsy?

It’s a scary thought because I kind of want to hope that they would have done a biopsy anyway. I have known people that they haven’t done biopsy [for], and luckily it’s not been cancer. But then you also do hear some horror stories of people that just kind of get a bit fobbed off, saying, “Oh, you’re too young for it to be cancer. It doesn’t feel like it.” They’re lucky if they get a scan.

I made sure to push the fact that I had the BRCA mutation. Obviously, I was terrified, thinking, “If they want to do a biopsy, that means they think it might be cancer. But then if they don’t do a biopsy, what about if it still ended up being one and it’s missed?”

I did say to my mom I hate the fact that she had cancer, but in a weird way, I said she kind of saved my life. If she wasn’t diagnosed a second time, she wouldn’t have known about having the BRCA gene. Then I wouldn’t have found out about it. In a weird sort of way, I told her that she’s kind of saved my life for that reason.

Lucy’s mom’s breast cancer diagnoses

The first time [my mom was diagnosed], I think it was in 1998. I was 7 months old. She got the all-clear. It was in 2019 she was diagnosed again, and she got the all-clear for a second time luckily.

In 2020, I think she’d had a few complications, and there were a few scares. She was having more scans after, and it was only a few weeks before I was diagnosed that she got the full, “Right, you are definitely cancer-free.”

Processing the diagnosis

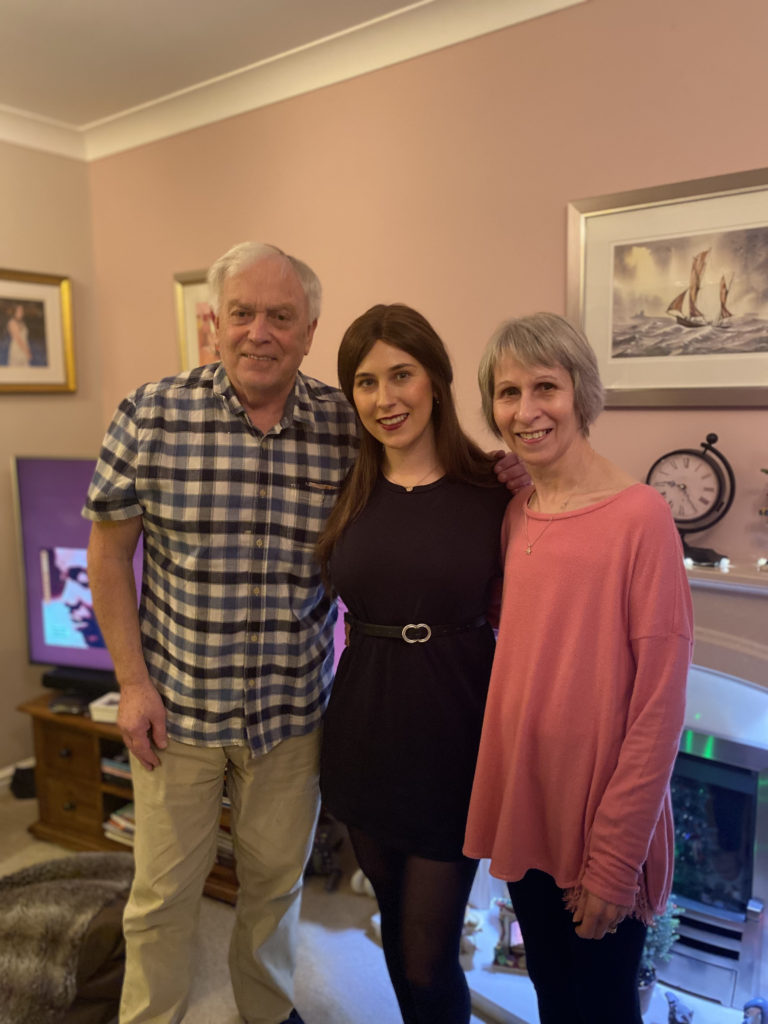

[They were] still doing precautions with COVID, [like] not allowing people into the hospital with you. Luckily, they said my mom could come in with me. The nurse had already told me at my initial appointment when I had my scan, whatever the results, my mom could be with me.

Luckily, my mom was there. I just kind of remember my surgeon saying, “I’m sorry to tell you there is cancer being found in the cells and in the biopsy.” I think the first thing I said to my mom was, “Am I going to lose my hair?”

I’d expected the result, for them to say you’ve got cancer with having to go in, but as I said, there’s that slight hope. It’s still such a shock to hear, especially only just turning 24, that you’ve got breast cancer. I remember saying to my mom, “Am I going to lose my hair?” and then thinking, “I don’t want to die.” We just both burst into tears.

Then luckily my dad was waiting in the car park. One of the nurses actually went and brought him in. Luckily, all 3 of us were able to be there together. It definitely took a while for it to sink in.

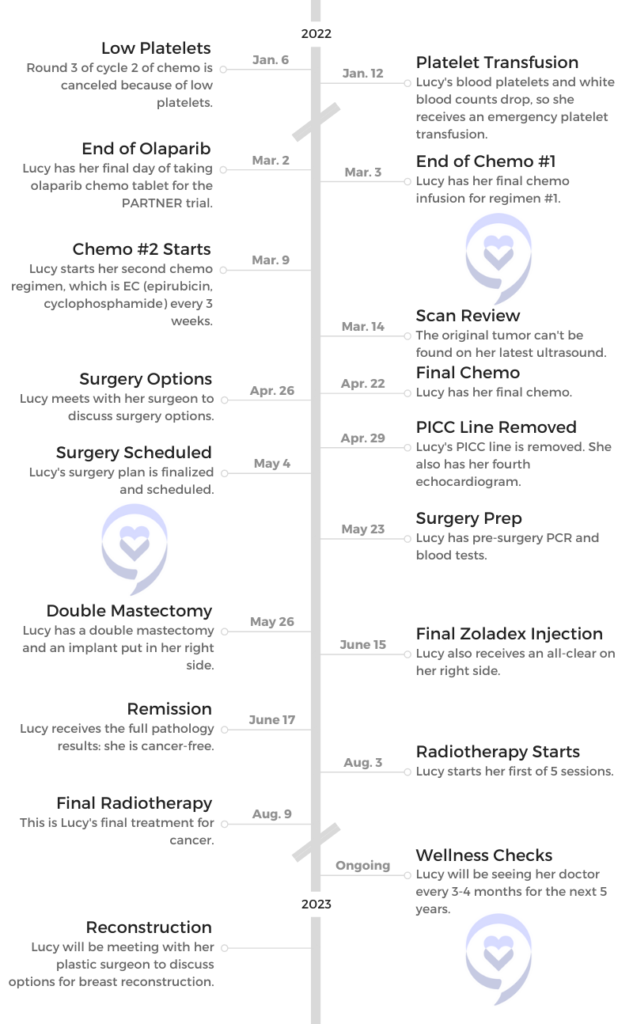

I remember going to my boyfriend straight after, and as soon as I saw him, I just collapsed in his arms and just cried and obviously didn’t sleep at all that night. At that minute, as vain as it sounds, for me a big part of my appearance [was] my hair.

After years and years, I just got it to a point that I loved and I was happy with. I remember thinking when my mom was diagnosed, one of the hardest parts if I was ever diagnosed would be losing my hair. It’s growing back luckily. There were other parts that I did think [about] later on, but it was just that initially for me.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

Losing the feeling of femininity

I think as well being told that I would most likely need, which I did end up having, a mastectomy or a double mastectomy. I think for me as well, though, that was also another large part of it. I know it’s not the be-all and end-all in life, but when I do eventually have kids, I had my heart set on breastfeeding or at least attempting to.

Then having that taken away from me as well — so much of who I am [and] my femininity had been taken away from me. I think that’s what I was struggling to come to terms with initially.

Support from Lucy’s mother, who had also gone through breast cancer

As I said, I hate the fact that [my mom] had to go through it. Because she also had a double mastectomy, we went through the exact same treatment plan. We had the same chemo regime and everything. The only thing she didn’t go through that I did was fertility preservation.

Having someone there that understood and knew how I was feeling, someone so close, it did help. If I was feeling down or feeling ill, she knew how I felt. Other people tried to understand, but obviously they’ve never been through it. Having someone so close to me who knew really did help.

Tests, Scans, & Fertility Preservation

What happened after diagnosis?

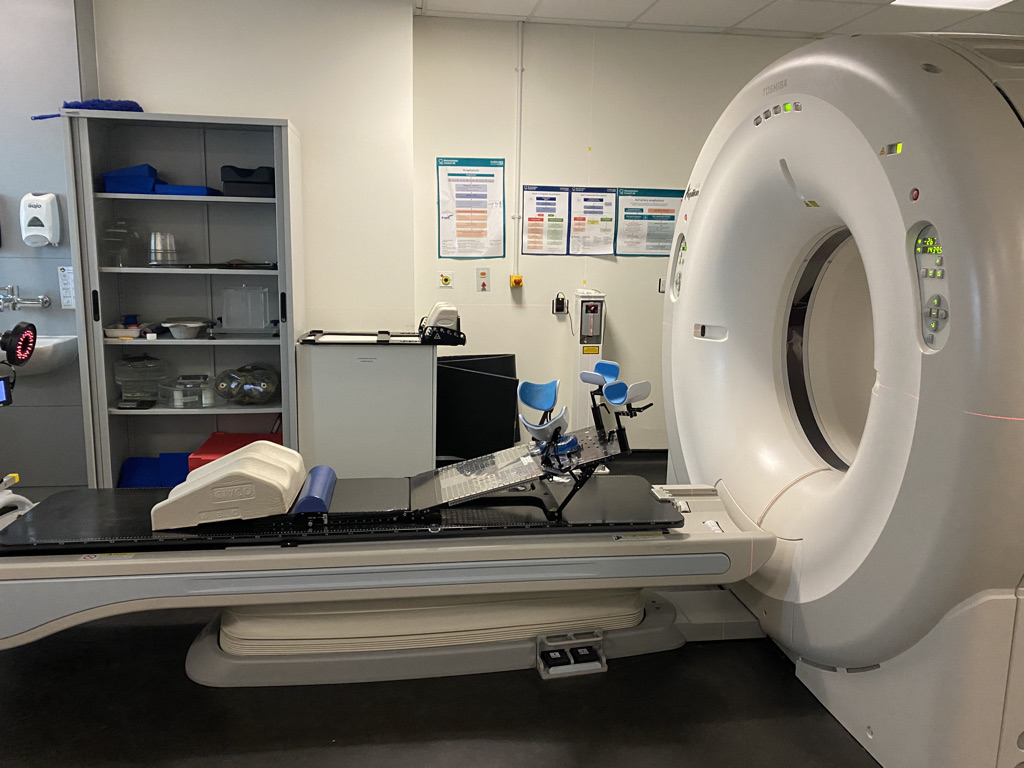

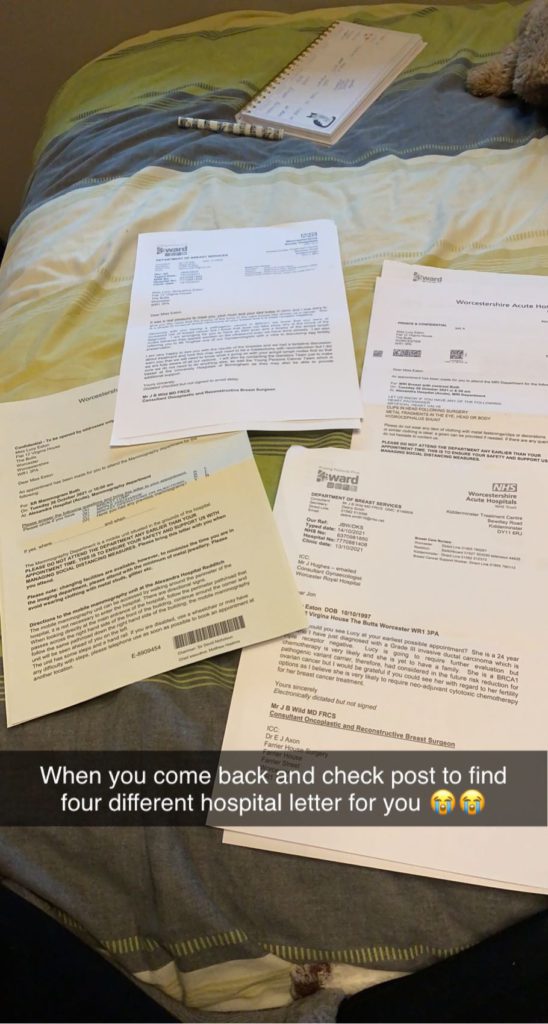

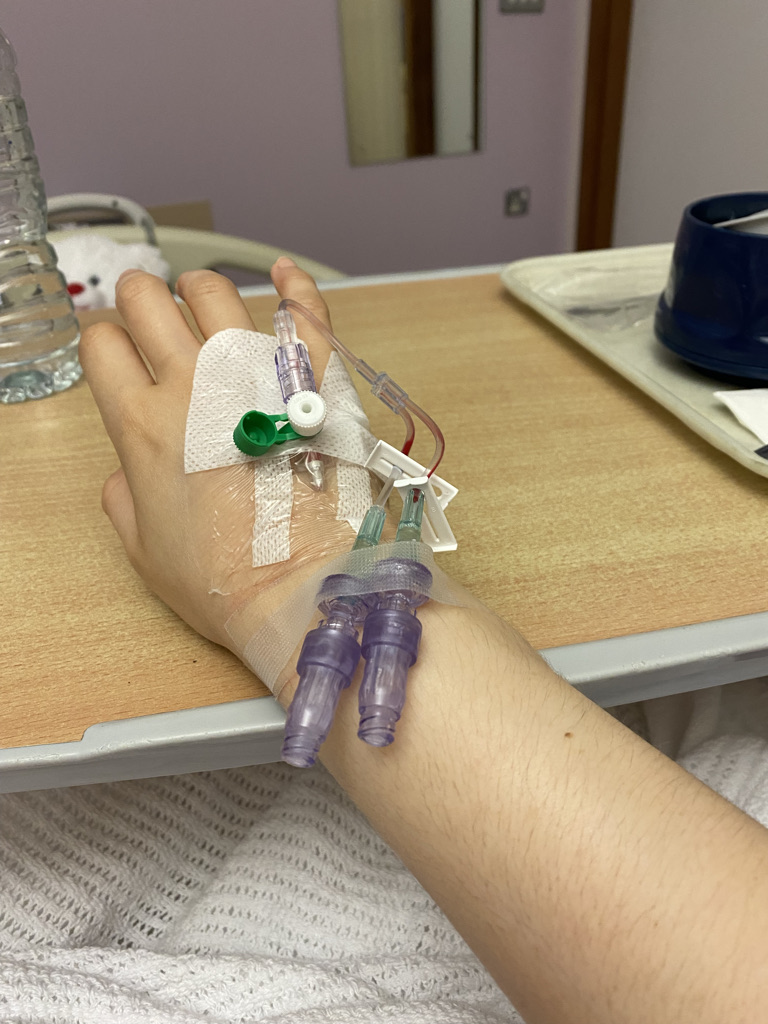

Everything happened really quick, really. I was just sent in for all these tests, all the scans, because they thought that it might have spread to my nodes. They said when I had the initial ultrasound, it did show that there was something there, but they obviously weren’t certain until I had further tests.

I had another ultrasound and biopsy under my armpit to test for the nodes, which did come back positive for cancer in a few. I had a breast MRI scan to make sure it hadn’t spread to the other side and a mammogram, which luckily it hadn’t. I had a CT scan to make sure it hadn’t spread anywhere else [in] my body.

Because of my age, I’m classed as a young adult still, so I was put in contact [with] the Teenage Cancer Trust. It was quite overwhelming because it was just within the next couple of weeks following my diagnosis. I just had all these people ringing me, telling me of what support’s out there.

It was great to know about financial funding, talking to my Teenage Cancer nurse, talking to the Little Princess Trust about a wig. It was great to know what was out there, but just being told you’ve got cancer, then all these calls coming in, it was very, very overwhelming.

It all happened really quick. I had the scans within a short period of time. I then went for my fertility preservation, and then it was straight into chemo. Being diagnosed October the 13th to then starting chemo itself in December, there wasn’t a week that something wasn’t really happening.

What stage were you?

I know I was grade 3 and it’s triple negative. I’m not really sure what stage I was. I did ask my oncologist, but I think he said it was kind of late stage 2, early stage 3. It had gone to the nodes, but there were only a handful.

I’m not quite sure how many nodes it’d actually gone to, but only a small handful, and it wasn’t that big. I think I was kind of in between. I never got a definite, “You’re this stage.”

Enjoying time between scans

For my birthday, my boyfriend had bought me tickets to go and see a West End show in London. Of course, when I was diagnosed, I thought, “Hang on, will I still be allowed to go to do this and go and see the show, go to London?” It was the end of October.

My surgeon said, “Yes, when you’ve got in between the scans and everything, enjoy yourself. Make the most of it. Do whatever you can, because it’s going to be one of the toughest years of your life.”

I tried to fit in things like that, going on a final night out. It was all very emotional, knowing I won’t be able to do anything like that again for a while, but I’m glad I was able to try and fit things in while I could.

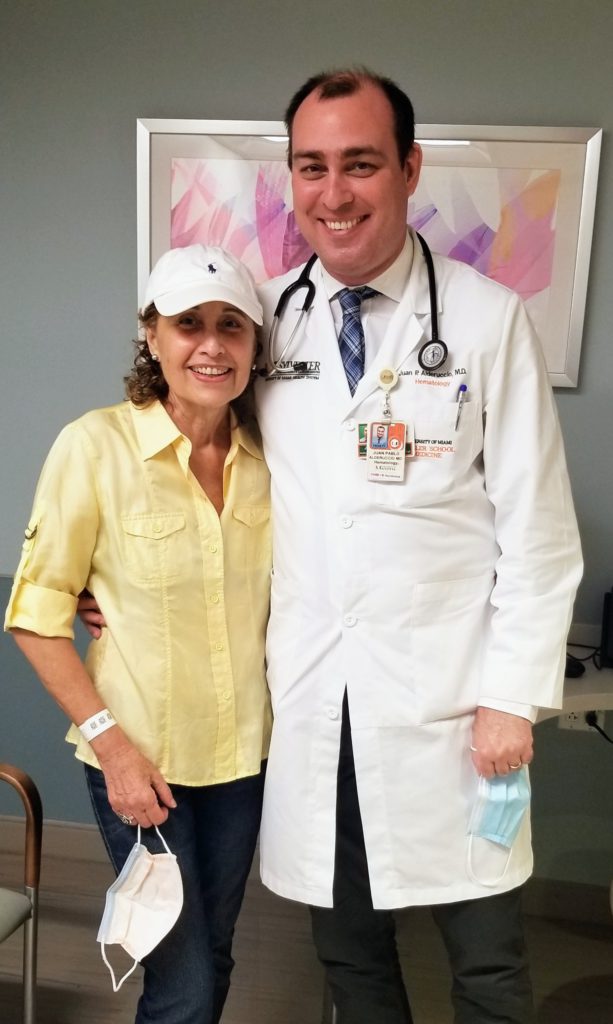

Relationship with surgeon and care team

As soon as [my surgeon] walked in and he gave the news, I just instantly felt so at ease with him. A lot of the time, when you see surgeons or at least medical professionals, they’re just very stoic and on the computer notes. But no, he had nothing like that around him. You could tell he cared about his patient. I trusted him and his decisions immediately.

Did you feel like you could have that open relationship?

Oh, yeah, definitely. Not on that one day, but in the space of … my initial appointment to my diagnosis till my next appointment with the surgeon. Just all of the nurses even said to my mom and dad, if they had any questions, even they could ring up, and they were happy to answer. I knew I was in really good hands from the whole team.

Fertility preservation

I knew [with] chemo there is the chance of going [into menopause] because it happened to my mom. The first time she went through chemo, it put her into a permanent menopause. It stopped her periods. I knew that was a possibility, but I didn’t really think about that at the time.

They brought it up. I think they said, “You can go through fertility.” It wasn’t until after I thought, “Oh, yeah, I might not have kids, so I definitely want to go through the fertility preservation if possible.”

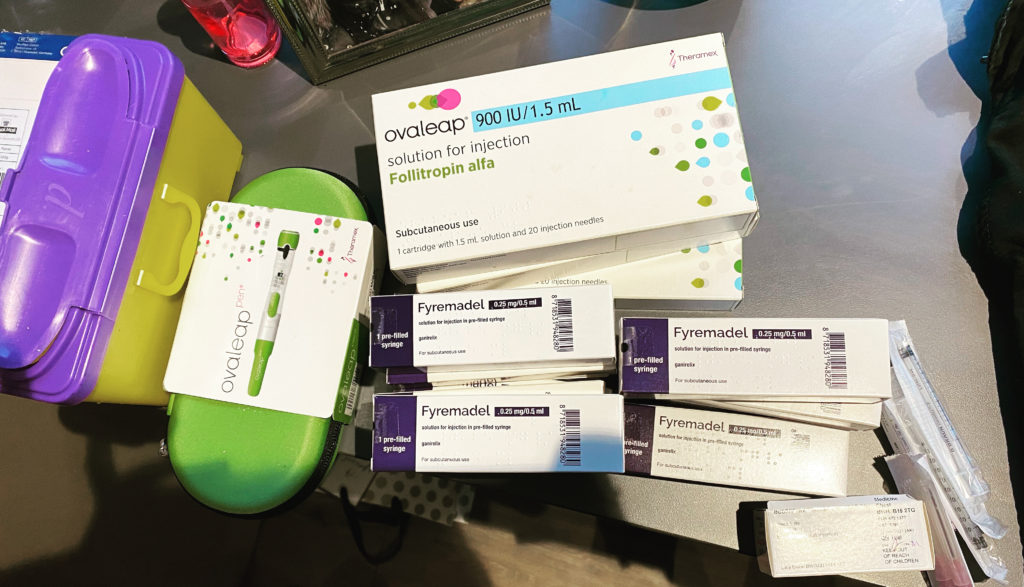

It was also mentioned to me I could go on Zoladex injections throughout my chemo as well to put me into a medical-induced menopause to try and help increase my chances of my periods coming back after.

I think before my diagnosis, the genetic counselor [said] that when I do eventually have children, because there is a 50% chance of passing the BRCA1 gene onto my young kids, there’s this special IVF route I could go down to try and make sure I don’t pass it on.

I spoke to them about that as well when I went for my initial appointment to talk about the egg harvesting. I thought, “Yes, I can have eggs frozen now and use them when I do eventually want to get pregnant to try and go down this special route so I don’t pass the genes down.” It kind of worked out well.

Special IVF route

I don’t know the specifics. It was only really briefly explained to me quite recently after I was finished. It’s this type of genetic testing. For egg preservation, you can either have your eggs frozen or embryos. I had eggs frozen. What they would need to do is get the eggs fertile and turn them into embryos.

Once they are embryos, they do this genetic test. I’m not quite sure what it’s called, but they can test for the BRCA gene. Any that have the BRCA gene, they can be discarded or I think used for scientific research and whatever they want to do with them. Then the ones that don’t have the gene I can then use to try and hopefully get pregnant with.

I could still go down the natural route if I wanted to in having kids. If I can help it, I really don’t want to pass this gene on because I don’t want to have a kid that turns [out to] have the gene. I know it wouldn’t be my fault, but I’d feel guilty knowing that I could have done something.

I want to try and go down this route if possible. If not, I will go down the natural route. I’m not too sure fully what happens with it, but when the time comes, they told me to get in touch with a special type of genetics fertility clinic rather than just the general one, and then I can speak more to them then.

Treatment & Side Effects

What was your treatment regimen?

I was offered a part in a trial. I don’t know for definite, but I think [it’s looking at] triple negative if you’ve got the BRCA1 gene. I thought, “Yes, I’m going to do [it]. Obviously, not only helping research, but I’m going to just take whatever I can to try and get rid of this cancer.” I was on carboplatin and paclitaxel as my main course.

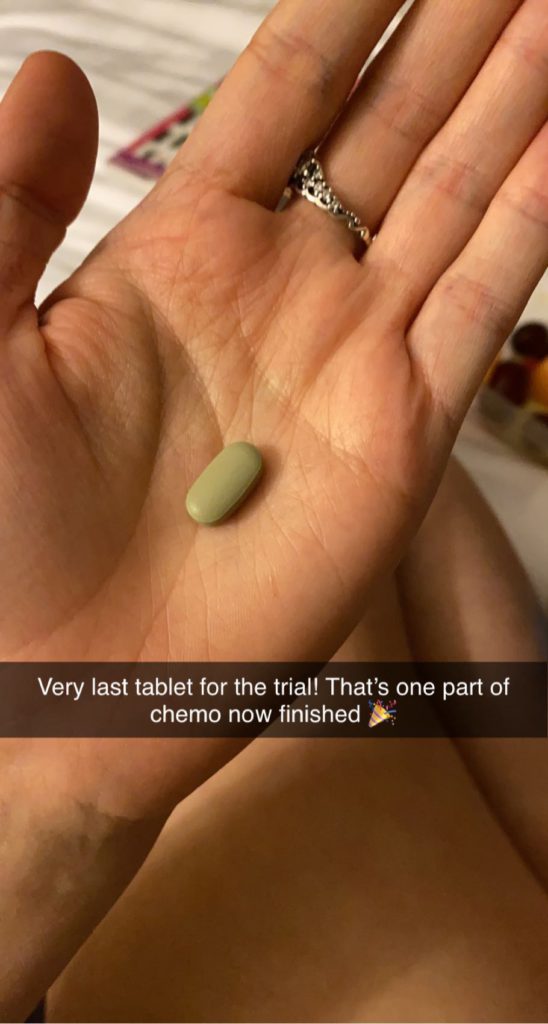

Alongside that, I had to take olaparib tablets every day for part of the trial, which was a kind of chemo tablet. I did that for 4 cycles. The carboplatin was once every 3 weeks at the beginning of each cycle, and the paclitaxel was every week.

Then at the beginning of each cycle, it was a double infusion. Then after the 12 weeks — well, what should have been 12 weeks because I had the break because of my platelets — I went on to EC for 3 cycles, which was given every 3 weeks. That lasted 9 weeks. Yes.

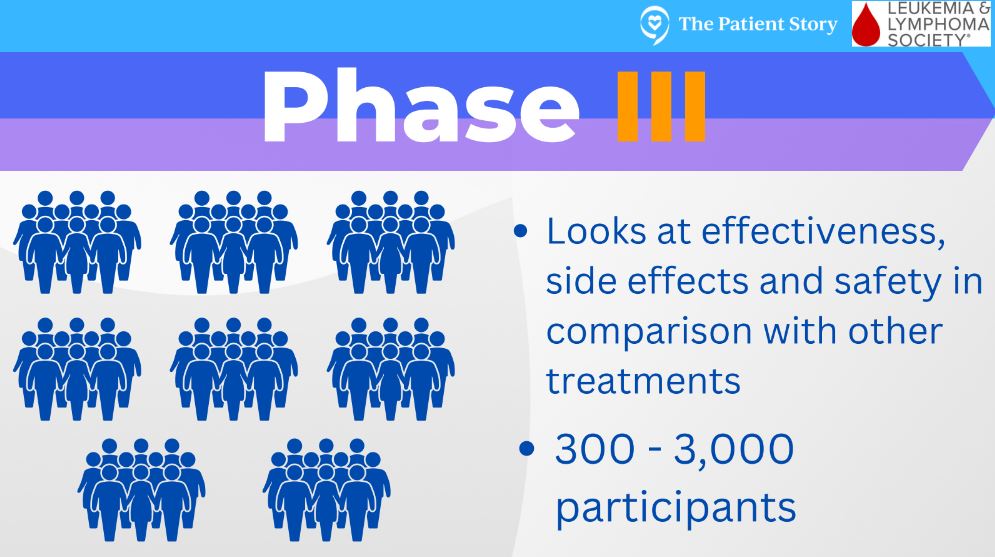

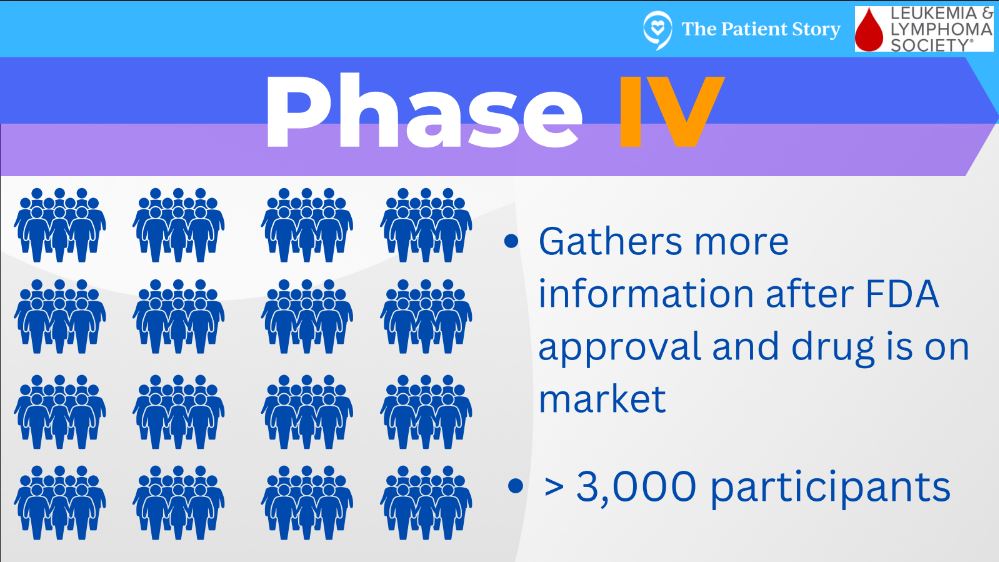

What phase was the clinical trial?

I’m not too sure. I think it was maybe one of the later stages because I know they’d done initial trials with 2 tablets before, and then it went on to, “Right, this is the tablet that we want to use.”

I could have either been put into the group that didn’t receive the tablet or I did receive it. I’m kind of glad I did receive the tablet, because for me, it felt like I’ve got another chemo on top of what I’m already being given.

Were you in the hospital for infusions and home for the pills?

Yes. I took [olaparib] from day 3 of the cycle for about 12 days-ish maybe, give or take a few days. Was it 2 or 3 times a day? I can’t remember for certain. That was only throughout the first part of my chemo regime, though. As soon as I went on to EC, I stopped with the olaparib.

What side effects did you have?

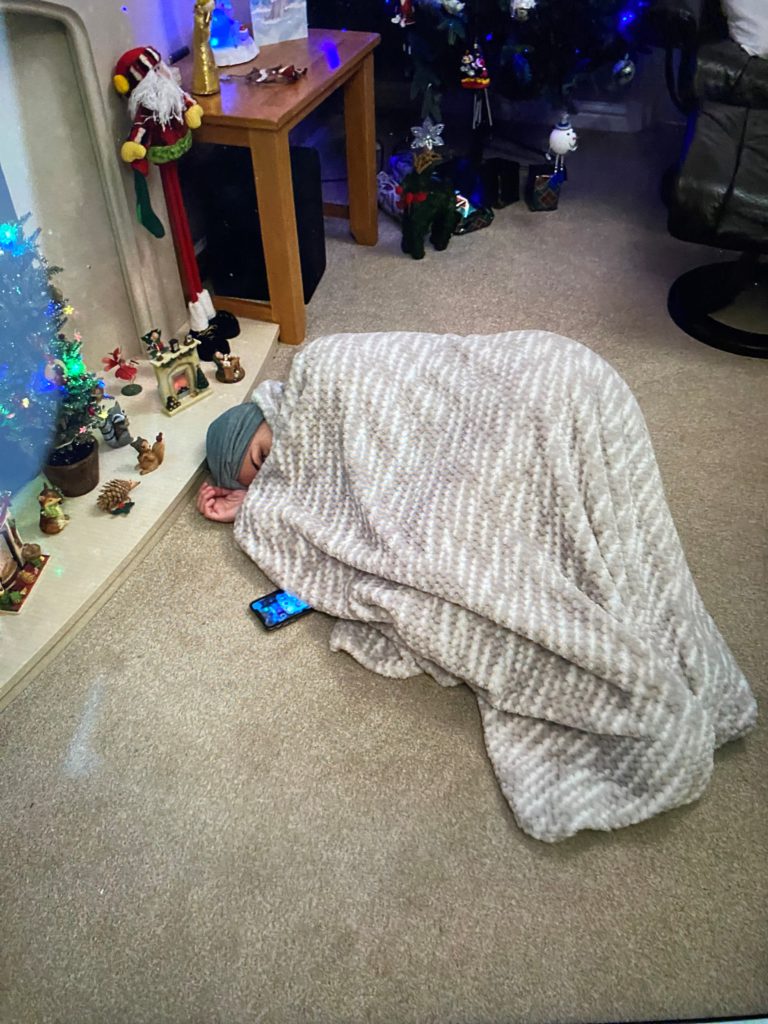

I typically had my chemo infusions on a Thursday, and then it was the Monday and Tuesdays when it hit me quite hard. Fatigue. That’s throughout all of chemo. That’s been the biggest and consistent side effect.

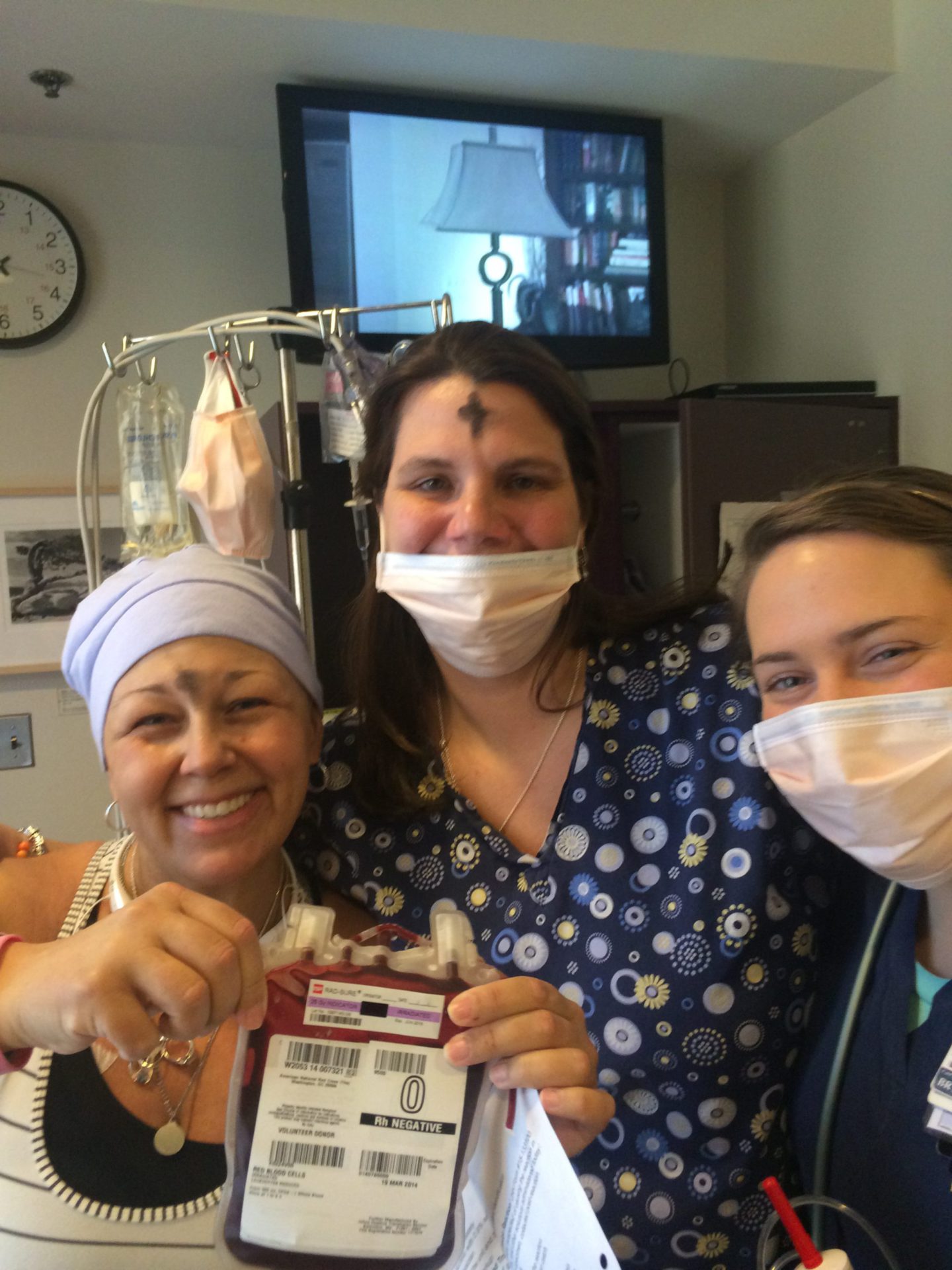

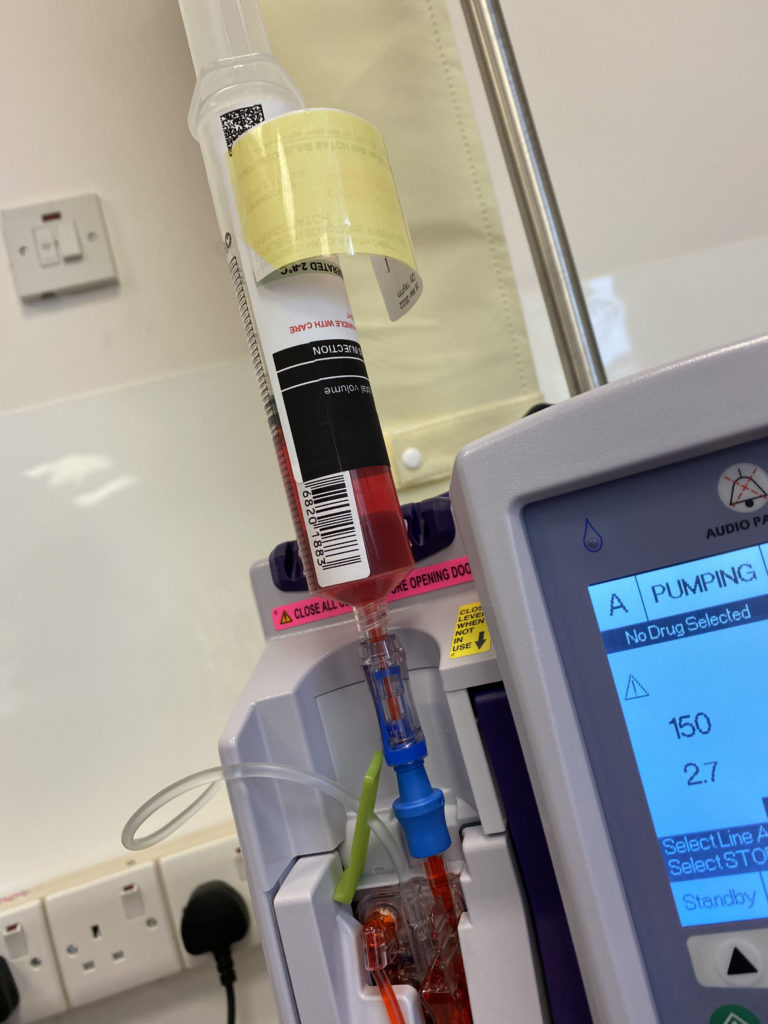

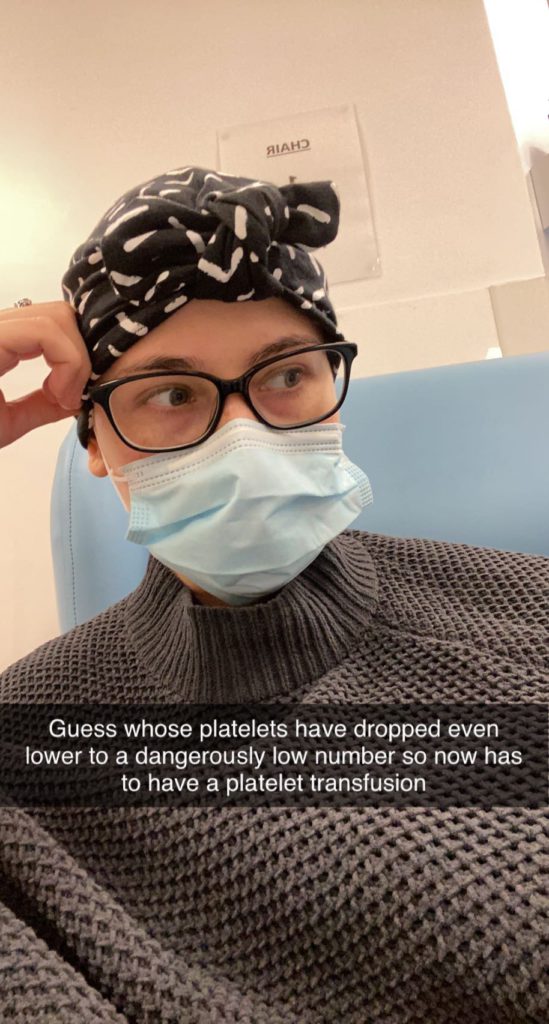

I was only actually sick once, and that wasn’t until EC, my second cycle, but I did feel sick. I felt quite dizzy and lightheaded a lot. Obviously, very weak. Hair loss, obviously. My platelets on EC, I think it must have been because I was just on 3 lots of chemo. My platelets dropped extremely low, so I did have to have a platelet transfusion.

I was getting nosebleeds, bruising extremely easily. I didn’t even bump myself, and I was noticing the bruises. The main consistent [thing] was feeling a bit icky, a bit off, and just tiredness.

I did also have a horrible taste in my mouth quite a lot, I think from the mixture of the saline solution that obviously I had a lot of throughout chemo. Also chemical taste, so that was making me feel sick quite a lot.

When my platelets dropped as well, I was getting a lot of mouth ulcers. I had a really bad one at one point as well. For my first lot [of chemo], they reduced the dose as well. I was on a lower dose for my body to try and tolerate it.

I didn’t so much lose my appetite like a lot of people tend to do during chemo. I couldn’t eat large portions of food a lot. I was trying to eat small, but quite often. When I had the ulcers, it was just making it really hard to eat. I was having to nibble. I was given a mouthwash, which kind of helped, but luckily [the mouth sores] didn’t last too long.

What helped with side effects?

I drank a lot of water. Staying hydrated is the main thing. A lot of people can’t drink plain water, but I love water anyway. I didn’t have that issue. A lot of flavored water as well. Sugar free. I sucked on a lot of mints and things like lemon drops as well, which helped with the taste.

Rest a lot, as much as you need to. Definitely listen to your body. Don’t overdo it. With the eating, just small, light things. They say a lot of time you start to hate the taste of your favorite foods, so I was hesitant to eat my favorite things.

I love peanut butter, and so I was hesitant to have peanut butter sandwiches. I did actually start, during chemo, have the craving for them. Be careful with things you normally love, because a lot of the time people do come to start hating that food because they can’t tolerate it anymore.

They do say use a lot of spices so things don’t taste as bland. I had stocked up on a lot of biscuits and health bars, so I just always had, whenever I went out, just something to nibble on if I started to feel a bit sick or felt I needed something.

Navigating hair loss

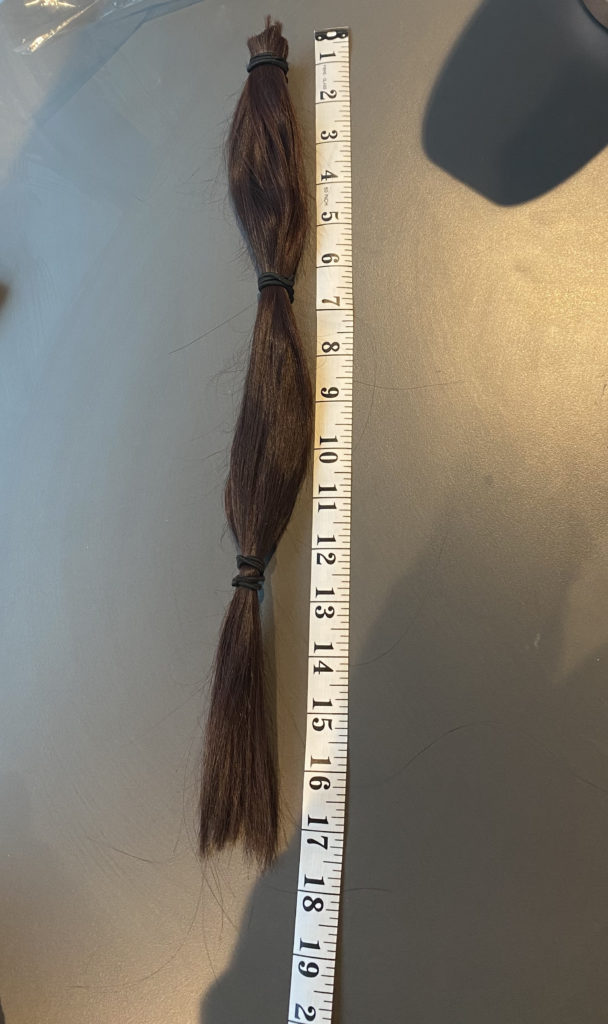

I started chemo, I think it was around the 2nd of December. My hair was initially down to my waist, so just before I started chemo, I had it cut shoulder-length so it wouldn’t be such a big shock when it did start to fall out.

There is the option of cold capping, but I didn’t think that was for me. I didn’t want to, because a lot of people can’t tolerate it. I didn’t want to go through the potential headaches with it and being cold all the time. I just thought, “I’ll just embrace the hair loss. Whatever chemo gives me, I’ll take.”

Then I think it was just before Christmas — so it must have been around a couple of weeks in — I started to notice the odd strand of hair coming out, but it wasn’t too noticeable.

It wasn’t actually until I went out for a meal with my boyfriend and a couple of friends that — I was out for the meal. I touched my hair, and the first big clump came out. I tried not to ruin the night, but for me it kind of put a bit of a downer on the night.

[Then there were] clumps every time I touched my hair, brushed it, washed it. I was trying to hold off until I went home for Christmas, so my dad could shave it for me. I think it was on the 20th, my boyfriend stopped at mine that night. I woke up the next morning, hardly sleeping because I was in so much pain from my head.

I had a massive mat on the back of my head. I just knew. I was like, “Josh, it needs doing.” I went to his [place] that night. We went to his mom’s, and she just shaved it for me. That was on the 21st. Unfortunately, I didn’t make it till Christmas.

I took a picture of that morning, the morning of the 21st. The difference in how much I’d lost just in that one day to the afternoon — I couldn’t have gone longer. It needed doing. I probably left it a bit too long to shave, because a lot of people do it a lot sooner than I did. It was the one thing I was just trying to hold off on.

I didn’t cry. I was expecting to cry when it happened, but it kind of didn’t hit me until later on, a few days later. It was just kind of such a relief that the pain was no longer there. Obviously, I didn’t look as bad as I thought I was going to look. I hated it, but I was expecting to look a lot worse. I think it was just the relief that I didn’t have to cope with all the shedding anymore and the pain.

»MORE: Patients describe dealing with hair loss during cancer treatment

Remission & Mastectomy

What happened after your first treatment?

I would see my oncologist after every cycle anyway so he could review me, and I could let him know of side effects if there was anything. I didn’t have any other scans until halfway through. As I finished my first part of my chemo regime, I had an ultrasound just to see how it was progressing.

That’s when they told me they couldn’t see the tumor itself. They could only find the marker. The lady who did it was actually really confused at first because she couldn’t find the tumor. She thought the marker had been placed in the wrong place, and she had to look back on the original scan to see that.

Obviously, I’d had a really good response to that. Then it wasn’t until I finished all of my chemo. I then had my final breast MRI scan just as a final after-chemo check. I think it was around January, I had a kidney function test, which took all day. A blood test, but they had to keep monitoring it, taking multiple blood samples throughout the day.

I’m not sure if that was part of the trial or chemo. I’m not quite sure what that was about, really. I was just told I needed to go for it. It was after that when I found out that my platelets had dropped. I remember them taking the cannula out, putting my jacket back on, feeling my arm was wet, and just blood gushing down my arm.

Luckily, I was seeing my oncologist the next day. He told me my pre-chemo bloods were a bit low still. Then he rushed me to have another blood test done, and that’s when he said they’ve dropped down to 12, which explains why the blood was running down my arm as much as it did.

He just sent me for an immediate platelet transfusion. Then from then, luckily with being on lower dosage as well, the platelets went back up, and I was fine again. They were the only scans and tests I really had throughout chemo.

How did you feel knowing they couldn’t find cancer in your scans?

I remember coming out of the halfway ultrasound, and I just walked into the waiting room to my mom and just burst into tears. Obviously, I didn’t want to hope for anything until I’d had the confirmation from the nurse or oncologist, just knowing that.

Then there’s also that I didn’t want to get my hopes up too much because there’s still little cells that could have been floating around my body that aren’t picked up on scans and only in the pathology.

It looked like I’d had a really good response on both the halfway scan and the end-of-chemo scan. Everyone is expecting me to have a full response. But still, you don’t want to get your hopes up too much. I’d made it known to people that this isn’t definite. I won’t know it’s gone until I get the pathology results back after surgery.

Receiving the all-clear news

I finished chemo [the] end of April. A week later or so, I saw my surgeon. He told me of my options for surgery. Then a week later, I went to see him again and told him my decision. Then it was the 26th of May, I think, when I actually had my surgery.

I think it was around the 15th of June when I went to see my surgeon again for my results. Because of COVID and it had just been a bank holiday (it had been the Queen’s Jubilee here), there was a bit of delay in the lab, so they only had my right-side results back, which came back all-clear, which we expected because cancer wasn’t at that side anyway.

Then I got a call from oncology the next day, saying, “We’ve actually got your results back. Do you want to come and see your oncologist on Friday, the next day?” The 17th of June, I got my results back, saying I was all-clear and cancer-free.

I remember walking into the oncology suite, the chemo suite, and the nurse booked me in. Then I saw my trial nurse, and she didn’t realize I hadn’t already got my results. She said to me, “Oh, how are you feeling? How are you?”

We said, “Well, really nervous, obviously.” She was like, “What? Why? It’s great news.” We’re like, “What, are they back?” She said, “Yeah, yeah, it’s all-clear.” Me and my mom just looked at each other in the middle of the waiting room and just cried and hugged each other.

It was just relief. A bit awkward in front of all these patients waiting to go for chemo and everything, but just being told then and there, “You’re cancer-free.” My nurse didn’t understand why I was really nervous.

»MORE: Patients describe dealing with scanxiety and waiting for results

Double mastectomy and implant

I had the surgery 26th of May, and I received my results on the 17th of June.

It was quite stressful because my surgeon told me, “Right, these are your options.” Basically, “These are your options. It’s up to you, basically, which you want to go for.” He was saying, “These are your options. Come back in a week.”

It was very stressful being told. In a way, it was good that I had some freedom of what I wanted to happen to my body. It was still a bit daunting being that, hang on, it’s such a big thing, and I’ve got to make this decision. It would be just so much easier if someone else made it for me.

Me and my boyfriend did go away for the weekend as an end-of-chemo treat before my surgery. I tried to not think of these options. Just put all of that to the back of my mind. Just enjoy the time away together, and then focus more on it when I came back.

It was just [telling my surgeon], “Right. This is my decision.” He said, “Yes, that’s fine. This is the date you’re going to for surgery.” Then I think it was, what, 2 weeks later maybe? I was like, “Oh, I don’t have as much time. I know it has to be in a certain timeframe for them from finishing chemo to surgery. Still, I don’t have as much time as I’m ready for.”

It was just trying to prepare mentally for it and trying to figure out what I needed to take for surgery so it was all comfortable for when I got back. It was very daunting because up until that point, I’d had scams, appointments, and then suddenly there was this 2-week break of nothing.

All I had was, “I’m having a double mastectomy. Yes, it was my choice to have the double and not just a single, but I only have 2 weeks left of my body.” It was just trying to make the most of doing things while I could, going out without putting myself too much at risk before surgery, and making the most of things and try not to think about it too much until the time came.

What were the options that you were given?

I definitely had to have my left breast removed because of the node involvement and being BRCA1 anyway.

Because of radiotherapy, I wasn’t allowed to have reconstruction on the left side just yet.

My other choices were:

- Just have the single mastectomy and that’s it

- Have a double mastectomy but no reconstruction on the right side and just stay flat until further reconstruction down the line.

- Have a double mastectomy, stay flat on the left side, but reconstruction implant on the right side

My surgeon told me that he did speak to another surgeon, who said there’s no point in me having the right side done yet. I kind of pushed for it because as much as I hate having it done, I thought, “I’ve had cancer once at this age. I don’t want to risk having it again in the other side.”

I definitely pushed for the double mastectomy. It was just the option of whether I wanted to stay flat on both sides or [have] the implant. I did go for the option of having an implant on the right side because when I have reconstruction for my left side, it’s sounding as if it’s going to have to be DIEP, so stomach tissue reconstruction.

My surgeon did tell me there is the possible option, if there’s enough tissue there, of having the right side done as well, so having the implant swapped. I thought I might as well have the implant put in for now and get used to it in case, at the very worst, I can’t have it done. I am hoping I’m going to be able to have it done at both sides when it comes to it.

Reflections

The importance of self-advocacy

If you know something isn’t right with your body, especially if you know you might be slightly high risk, even if you don’t know you’ve got the gene (luckily enough I did), but even if you know you’ve got a family history of cancer, push for it.

You hear a lot of stories where doctors [or] GPs think, “Oh, it’s fine; it won’t be this,” and they get pushed aside. There is no age limit. As I said before, cancer doesn’t discriminate against age. If you know something is not right with your body, push for tests further, even if it means getting second opinions [and] going somewhere else. Just don’t hesitate [if there are] any signs that something’s not right or usual [or] any slight change.

Reaching out to your support system

A lot of people might think, “Hang on, I’ve got something not right,” [and] keep it to themselves. Of course, you don’t want to spread it, just tell loads and loads of people, [and] spread it about and everything.

If there’s something you’re unsure of, get someone else to check it. Even if you get someone else to check it, a loved one … no matter where on your body there’s something not right, don’t be shy or embarrassed. It’s your life at the end of the day.

A lot of people are scared to get things checked out because they’re embarrassed about it, but the longer you leave it, the worse off it’ll be. Even if, say, a loved one checks [it] out and doesn’t think it’s anything, if you know it’s not right — you know your body — still get seen by a professional.

I think they usually say there’s a 2-3-week rule. If something’s changed within your body and it’s not gone within 2 or 3 weeks, then that’s when you know you need to have it checked. No matter what it is, where it is on your body, don’t be embarrassed or shy to get it looked at.

Any last advice?

It is tough, extremely tough. Listen to your body. That’s the main thing. Do not overdo it, and rely on other people. If the help is there — friends, family — but you’re too embarrassed or you feel bad for taking the help, don’t. It is your health at the end of the day, and you need to get better, first and foremost. If people want to help [and] reach out to you to help out, take it.

How support helped you

Where I live, it’s like a studio apartment for young professionals and students. I’m still living in this accommodation studio apartment. Especially after my surgery, I knew I wouldn’t be able to do things like cook, clean, [or] even wash myself. I wouldn’t be able to do that on my own.

If I wasn’t at my boyfriend’s, my mom came and stayed with me. I got her to help out with things. As embarrassing as it might be, I got her to help shower me down. I got my boyfriend to help wash and shower me down as well. Though it can be quite degrading, it’s not your fault, and you need the help at the end of the day. Don’t be embarrassed. If people want to help you and do things like that for you, take it.

What’s next after being told you’re cancer-free?

I am still having reviews with my oncologist. I think for the next year or 2, I’m going to be seeing him every 3 to 4 months so he can check me over [and] see how I’m getting on. It’s really reassuring because even though you’re cancer-free, there’s still that fear there: what about if it comes back?

Any little pain [or] symptom, you think, “The cancer’s back. It’s here again.” It’s really reassuring that I’ve got that support and I’ve got him there. I’m going to be seeing him as much.

My next thing is [that] in January, I’m seeing the plastic surgeon for my breast reconstruction. Hopefully, I’m going to get a better idea of the plan for that. Moving forward, it’s just focusing on moving on with my life again. As soon as my next surgery is out of the way, I can start to fully get on with my life again.

How do you feel about the upcoming surgery?

It’s reassuring. I wish I could have the surgery now. I wouldn’t say I’ve come to terms with it, but I’ve accepted what I’ve had done is slightly better. I still look down sometimes and hate the fact that I’m flat there and that I haven’t got real breast tissue in the right side as well. I hate the fact I’ve got an implant.

I wish I could have the surgery now. I would not hesitate at the chance. I know I’ve got to recover fully from radiotherapy. I’ve got to be in the best shape possible first before I can have it done. I won’t say it’s not like looking forward to it, but I’m glad that it’s only a few weeks now until I see her and sort out what’s happening.

I think as soon as I know the plan more, then I can then start to think, “Okay, this is what’s happening. I can start to move on from this point. I can accept it from then on.”

I’m going to have more scars on my body, which I’m not looking forward to. It’s my health, and I’d rather have the scars than not have the reconstruction. Scars fade.

Inspired by Lucy's story?

Share your story, too!

More Breast Cancer Stories

Elissa K., Metastatic Breast Cancer, HER2+

Symptoms: Swollen and numb feet, discomfort while wearing shoes, severe fatigue

Treatments: Surgeries (lumpectomy, hysterectomy), chemotherapy, antibody-drug conjugates, targeted therapy (monoclonal antibody), radiation therapy

Maggie C., Triple-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer, PD-L1+

Symptoms: Bruising sensation in the breast, soft lump

Treatments: Chemotherapy, clinical trial (antibody-drug conjugate and immunotherapy)

Nina M., Metastatic Breast Cancer

Symptoms: Hardening under the armpit, lump & dimpling in the left breast

Treatments: Chemotherapy, surgery (lumpectomy), radiotherapy, hormone-blocking medication, targeted therapy

Symptoms: Shortness of breath, lump under armpit, not feeling herself

Treatments: Chemotherapy, Transfusions

April D., Triple-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer, BRCA1+

Symptom: Four lumps on the side of the left breast

Treatments: Chemotherapy (carboplatin, paclitaxel doxorubicin, surgery (double mastectomy), radiation (proton therapy), PARP inhibitors

Symptoms: Lump in the right breast, inverted nipple

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation

Bethany W., Metastatic Breast Cancer

Symptom: Lower back pain

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation, maintenance treatment

Abigail J., Metastatic Breast Cancer, HER2-low, PIK3CA+

Symptoms: Back and leg pain, lump in breast

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, CDK4/6 inhibitors

- 1

- 2