My Dad Was Diagnosed with Prostate Cancer. Now I’m Fighting It.

Dr. Leanne Burnham: A Caregiver, Patient, and a Doctor’s Journey

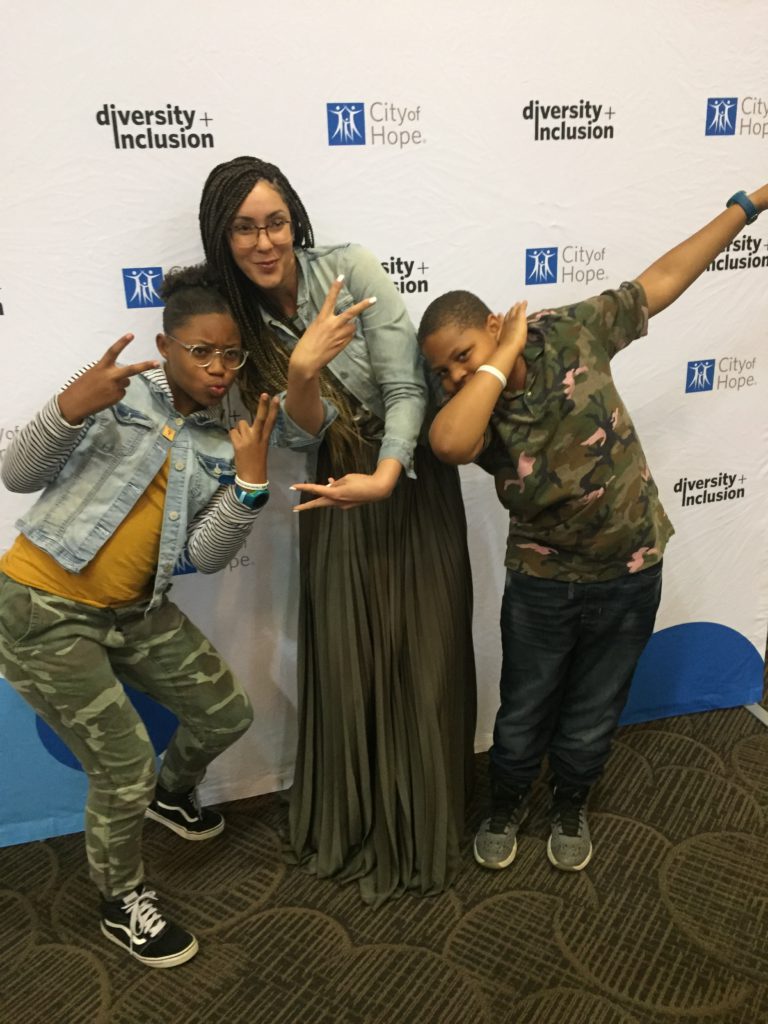

Motivated by her father’s prostate cancer journey, Dr. Leanne Burnham, scientist and community program coordinator at the City of Hope, dedicates her time and expertise so that communities of people of color could better understand prostate cancer and its specific risk factors.

Not only has Dr. Burnham been been a caregiver to both parents with cancer, she’s a lymphoma survivor, herself.

Her mission has been to raise more conscious and open conversations among families about their risks of cancer. That makes her a perfect fit in her department: Division of Health Equities at City of Hope.

Dr. Leanne Burnham is doing such amazing and inspiring work, not just in prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment clinical trials but also in patient self-advocacy, support, and other important socio-cultural factors around cancer. Explore our entire conversation below.

- Introduction: Dr. Leanne Burnham

- Prostate Cancer

- What inspired you to focus on prostate cancer?

- Prostate cancer in Black men

- Ongoing studies on PARP inhibitors

- City of Hope Work in Communities

- Being on both sides: Survivorship and cancer research

- Approaching conversations on cancer risks

- Patient Self-Advocacy

- Read Other Prostate Cancer Stories

- More Medical Expert interviews

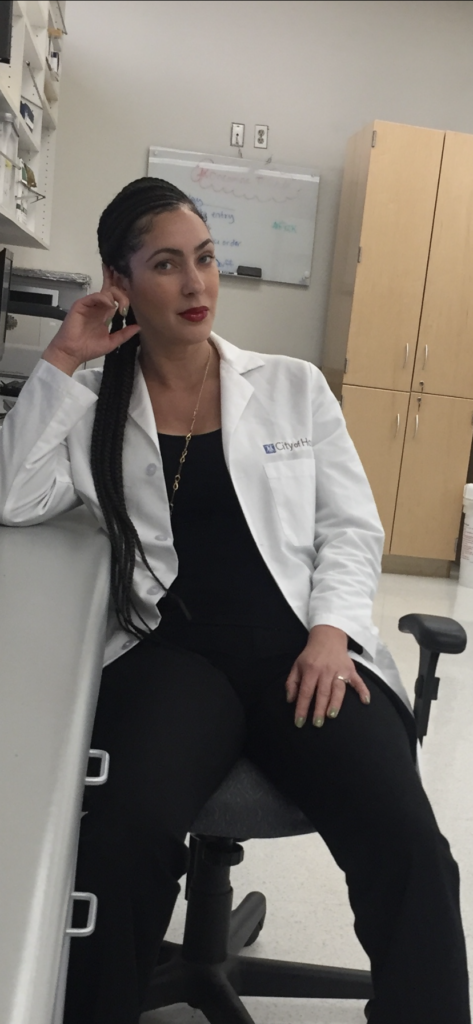

Introduction: Dr. Leanne Burnham

I am Leanne Burnham. I was born and raised in Akron, Ohio. Home of Lebron, we like to say. I live in California now. I am a wife and a mom of three. I have a 17-year-old, a 12-year-old and a 10-year-old.

I’m a scientist at the City of Hope, that’s what I do. I do experiments at the bench for sure. We call it at the bench when we’re in the lab, but I also do a lot of community work and work in clinical trials.

Prostate Cancer

What is prostate cancer?

There’s a lot to unpack. But first of all, women don’t have prostate, so it’s just a male disease.

Another thing that seems silly to say, but the prostate and the colon are two separate things. A lot of times people think they’ve had a colonoscopy means they’ve gotten their prostate checked. But that’s not the case.

According to the American Cancer Society, prostate cancer is one of those diseases with a 100% cure rate at five years if you catch it when the disease is still localized or confined in the prostate.

That’s amazing because not a lot of cancers are like that. Many people would hear, “Prostate cancer is one of the better cancers to get,” or they hear, “Prostate cancer happens to older men,” which is true.

It’s a disease of age, and there have been some studies that by the time men reach their 70s and 80s, many men, if not most, have prostate cancer at some point. But prostate cancer isn’t what ultimately kills a lot of men that have it.

For that reason, a lot of people tend to not get so stressed when they think about prostate cancer and their risk of it.

But it’s important to realize that the second you have prostate cancer cells escape out of the prostate and spread in the body, you go from a 100% cure rate in five years to there is no cure.

There’s no in-between, so all of the treatments we have once the cancer cells have escaped are to prolong life or improve quality of life.

We’ve got some really great treatments out there. We’ve got cutting-edge treatments nationwide that are really extending the lives of many patients, and they’re living great lives. But I’m at the City of Hope, so, of course, I’m partial.

It is also important to point out that, yes, prostate cancer is very curable, it happens a lot to older men, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen in younger men.

It doesn’t mean that there are no aggressive forms in younger men. It certainly doesn’t mean that if you have prostate cancer, you’re just going to be cured and be fine because it’s not that way for everyone.

Diagnosing and Staging

First of all, you start with a PSA test. That’s testing your prostate-specific antigen, which is a protein secreted by the prostate. It’s circulating in your blood, so that’s one of the first markers they can test and say, “Hey, something is going on with your prostate. It might not be cancer, but something is going on.”

After a PSA test, men will get a biopsy, then they get a Gleason score. Pathologists look at the tumor under the microscope and assign a score based on how cancerous the cells are looking.

The higher your Gleason score, the more aggressive your cancer is.

There are genetic mutations that not everyone has access to, but some physicians provide that for their patients. Especially if they have a lot of family members that have had prostate cancer.

You can look at the genetics and see if there are some mutations that make the tumors more aggressive. What makes it hard to pinpoint treatments for prostate cancer, and to find a cure ultimately, is that prostate cancer tumors are very heterogeneous.

If you’re taking a sample from one part of the prostate and another sample from another part of the prostate and you’re looking under the microscope, they look different. There are different genetic mutational landscapes in those tumors.

Prostate cancer cells are very smart. Every cancer cell is smart. I’ve had cancer but I also have tremendous respect for the cancer cell, its ability to navigate its way and go undetected by the immune system, its ability to receive treatments and figure out ways to resist those treatments and form mutations.

The ability of resistant cells to keep growing is truly amazing. Cancer cells find a way, I tell you, but the key to its science is when they find a way, we have to tackle that new way.

»MORE: Read more prostate cancer stories

What inspired you to focus on prostate cancer?

It was totally unfamiliar to me. I don’t really have a family history of cancer at all. My dad was relatively young. He was like 50 at the time. He worked out a lot, he ate very well, he was going to Mustard Seed (organic grocery store) and things like this.

One day, he called me as I walk out of a physics class. I picked up the phone but he wasn’t talking; he was just crying.

I was like, “What in the world is happening?”

I just heard him crying on the phone, and he said, “I have prostate cancer. You’re the first person I’m telling. I haven’t told your sisters, so if you can come to the house when you get out of class and I’m going to talk to all of you guys. I’m just letting you know.”

At the time, I was a premed student, so he was reaching out to see if I had any advice, which I didn’t know about prostate cancer at all.

That experience really kicked off my passion for understanding what was going on with him. But beyond his diagnosis of prostate cancer, I started to notice that Black men in our community were getting that, as well.

It was just something I hadn’t noticed before, so I’m like, “Oh wow, this person at church has it. Oh wow, this person at the grocery store has it.” Different men were getting prostate cancer in their 40s and 50s. It was younger than what I would have thought.

So since I was a student and I had some shadowing opportunities and some research opportunities, I decided to get those hours at Cleveland Clinic, which is number one in urology in the nation, and that’s where my dad is a patient.

I went, and I was able to spend quite some time there. I was with a physician one time when he walked into a room with a Black patient with prostate cancer, and when he walked in the hallway with me, he said, “I hate these cases.”

He said, “Because every time I see a Black man in their 40s, or 50s with prostate cancer, it’s almost like it’s a different disease than other prostate cancers.” He was like, “You have to treat it so much more aggressively. It’s just a different ballgame.”

That’s when I thought, “Wow. I never had thought about it. Was there a difference in race and all that?”

From that point, when I went on to Loma Linda University to get my doctorate, I decided that I was going to focus my dissertation on prostate cancer and Black men specifically, and looking at reasons why their tumors might be more aggressive.

Prostate cancer in Black men

There are so many reasons why that is, and there’s been a lot of research that goes into looking at the multifactorial reasons behind that. We do know that Black men are much more likely to get prostate cancer.

Different numbers float around.

The American Cancer Society says that Black men are 76% more likely to be diagnosed. We do know that Black men are much more likely to be diagnosed at younger ages. When they show up to the clinic, they’re at a more advanced stage.

We also know that they are more than two times more likely to die from prostate cancer.

But what’s new on the forefront that we have found in the past five years doing clinical trials that include Black men is that when Black men are given cutting-edge treatments that are out, they actually respond better to treatments than men of other ethnicities, which is really exciting for any disease that you look at.

You can look at breast cancer, colon cancer, or others. If you have a certain demographic that is most high risk and doing the worse, if you can show that if you give them medications, they’ll do better, that’s a win-win for everybody at the end of the day.

Disproportionate risk to prostate cancer

Watching him go through his surgery and radiation and seeing his medications and things that he was on made me realize how private prostate cancer can be.

I really have never even talked to him about this, so dad, don’t get mad when you watch. I noticed some issues come up that maybe men would be embarrassed about. That was the first time I saw it with him.

Now that I’ve worked with hundreds of men with prostate cancer, that appears as a common theme.

Men are scared of certain treatments. They don’t want to have the side effects and don’t necessarily feel comfortable talking to people. They feel isolated sometimes.

That was the first time I saw my dad not be such a superhero. He became more human at that moment. Maybe he was embarrassed or nervous. I wasn’t used to seeing him like that.

DNA and genetic component

In terms of different reasons why he got prostate cancer younger, or Black men in general, for sure, there is a genetic component. I’ll start with the things you can’t change.

You can’t change your DNA. The reason that Black men in the United States specifically are at increased risk for aggressive prostate cancer is because their DNA happens to trace back to the DNA of West African men.

This makes sense because, in the history of the US, the transatlantic slave trade, Black people in the US came from the western portion of Africa. Not surprisingly, men in West Africa have very high rates of aggressive prostate cancer as well, so that DNA matches.

There are certain variations on certain chromosomes that we know that are more likely to occur in Black men than other ethnicities that makes them more likely to get aggressive prostate cancer.

Role of Vitamin D

In addition to that, my boss, Dr. Rick Kittles, the Director of the Division of Health Equity at the City of Hope and an internationally known geneticist and prostate cancer researcher, has shown for a decade that there’s a link between vitamin D deficiency and prostate cancer risk.

People may have heard about COVID going on, like, “If you’re vitamin D deficient and have COVID, that’s not a coincidence.” Vitamin D deficiency leads to a lot of pathogenic trends.

With prostate cancer specifically, we know that vitamin D deficiency leads to tumor aggressiveness. But how that relates to Black men is that our bodies make vitamin D from the sun, and our bodies are dependent on sunlight.

The more melanin you have in your skin, the less vitamin D your body can synthesize.

If you have darker skin, and then in our lifestyles now, we’re not outside in the sun as much as we used to be, we’re much more likely to be vitamin D deficient.

In the African-American population, about 70% are vitamin D deficient or insufficient. There’s a vitamin D link to prostate cancer as well, then we know that there’s diet and lifestyle, of course.

It’s always good to have a healthy diet, of course. But we’re doing studies at the City of Hope right now where we’re looking at the link between charred foods, like barbecue or grilled foods, and the ability of the consumption of that to contribute to more aggressive tumors.

Socioeconomic factors

There’s also socioeconomic status, which goes a lot of different ways. But first of all, it controls your access to healthcare that you have.

Of course, if you have better access to healthcare, you’re going to have earlier screening, maybe a better team of doctors who will treat your case with a precision medicine approach, and you’ll have access to newer cutting-edge treatments.

But the other part of socioeconomic status that we’ve really dived into in 2020, given our nation’s culture, is looking at discrimination, especially in healthcare and medicine and in science really.

We know that stress kills, literally. And there are studies out there, and I published on it, on how much cumulative stress somebody’s taken on over their lifetime. We know it occurs more often in Black people.

If you have that cumulative stress, it dysregulates your HPA axis. It dysregulates how much cortisol your body is making and how your body responds to that cortisol and looks at glucocorticoid receptors. But that’s real science; we don’t have to go all into that.

Comparing cancer cells in Black and white men

Basically, what I’ve shown previously is that when I treated Black prostate cancer cells that I was growing in the lab with cortisol and compared them to Caucasian cells. I had Black cells and I had White prostate cancer cells.

The Black cancer cells grew more aggressively, and they upregulated these genes in these proteins that made them more likely to resist therapy. You could have this cumulative stress that would dysregulate your stress hormone system, making you more likely to get cancer. Then once you do get cancer, it makes you less likely to respond well to treatment.

That’s a very interesting concept that’s being studied right now. There’s a lot of research dollars going into that nationwide. I’m not working on that anymore, but I can’t wait to see like the results that come out of that.

Ignoring the risk factors

This is something that infuriates me, for sure. I’ve also published on this.

First of all, in Southern California, where I live, we did a study looking at more than 400 men and found that with 54% of Black men, their doctors never even talked to them about prostate cancer screening. We have to start with that.

A lot of men are not even getting screened when they should. That is because prostate cancer screening recommendations for a while we’re saying, “Okay, screen every man at 50,” and then in 2012, the US Preventive Taskforce said, “We’re not screening men at 50 anymore.”

The problem is that it really hurt Black men, and that recommendation was based on studies that looked at 200,000 men that did not have prostate cancer.

They had done the PSA test to see if it was indicative that they would get prostate cancer in the future, but the studies say over 95% were men of European ancestry.

This recommendation is applied to everyone, but it didn’t consider a racial difference in prostate cancer risk.

The American Cancer Society and Prostate Cancer Foundation says that if you’re Black, and you’re 45, you need to get your PSA tested. If you’re Black, and you have family members that have prostate cancer, you need to get tested at 40.

This is the recommendation, and then you go to the doctor and your doctor says, ‘Actually, no, you don’t need to be screened.’ That’s a big problem.

That happens so many times. Of course, if you go to the doctor and the doctor says you don’t need to test, who would want to get the test? You’re just like, “Okay, I’m good. I don’t need to get the test.”

That’s the first thing. But then once you do get the test and you get your PSA results back, there are differences in how those numbers should translate based on race.

For a while, the number that men would look at is four nanograms per milliliter of your PSA. If it’s higher than four, then maybe you want to do some follow-up.

It’s actually 2.5 for Black men, according to the American Cancer Society. Dr. Rick Kittles has published that, actually. You can look at numbers of 1.5 in Black men and it can be predictive years down the road that it’s going to transform into prostate cancer.

A PSA of 14 is quite alarming and then by the time he was diagnosed, it was 64, as far as I can remember.

When you go to the doctor, and you have an elevated PSA, and a high Gleason, I can’t tell you how many times where I’ve had people reach out to me and they’ll say, “Hey, my Gleason score is seven and my doctor says that I should do watchful waiting.” I say, “Did they look at you? Do they know that you’re Black? Did they get the memo?”

It’s not a one-size-fits-all blanket approach sometimes. You really want to make sure that your physician, first of all, is referring you to a urologist. I would definitely say, go to a urologist at that point and have them help you make the decision and hopefully with somebody that’s well-versed in how this disease affects men differentially.

Watching out your genetics and mutations

You hear about BRCA mutations of breast cancer. Not surprisingly, if you have a high risk of breast cancer in your family, that also translates to prostate cancer.

They’re both hormonal cancers, but particularly, if you have BRCA mutations that run in families, we can treat patients with those mutations with PARP inhibitors. There are different kinds of PARP inhibitors that are in clinical trials right now. You’d have to check and see what’s available for you.

Oftentimes, we know that these mutations lead to more aggressive tumors. But sometimes, it’s like hitting the jackpot because then you have access to an additional line of therapy compared other patients that don’t have those mutations.

Genetic Testing

I think it would be individualized, and that the urologist would discuss with the patient their family history and just get a sense of how high their risk is. I don’t believe that it’s offered to everyone. Just because you want it, I’m not sure that you can necessarily get it or your insurance would cover it.

You could always pay for it out of pocket, but not everybody has that luxury. But if you have multiple family members that have prostate cancer, it is definitely something worth looking into.

Ongoing studies on PARP inhibitors

Dilemmas and decisions

I love working on clinical trials, because to me clinical trials, how I try to explain it to people, is like a VIP access to cutting-edge treatment.

Many people can be afraid of clinical trials because you might think that you’re going to be a guinea pig. There’s a lot of mistrust in clinical trials in the Black community, for sure. Number one, because of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment that was just a trial gone completely wrong for 40 years.

There’s a lot of mistrust about clinical trials and who’s funding it and who’s behind it, and if I will be a guinea pig or get a placebo.

A lot of people have an idea that they’re going to get a placebo when in actuality, if you participate in a clinical trial, you are either going to get standard of care, which is what’s offered in the clinic to anybody that have your particular disease, or have the option get the VIP treatment on top of the standard of care or in place of the standard of care.

The VIP drugs don’t get to that stage just like that. It’s years and years in the making so by the time it’s to that point, we, scientists and physicians, feel very confident that this is going to work.

Thus, it is important to point where it’s at in a clinical trial and that there are different phases of clinical trials too. There’s phase 1, phase 2, phase 3. Obviously, the later the phase, the more people have used that drug in that disease setting before. So you can decide if you want to do a phase 1 trial or feel better with a phase 2 or phase 3.

Stratified Clinical Trials

With clinical trials, they typically, in the past, have not included a lot of minority populations—Black, Latino, Asian, Native American, for sure. So it really does a disservice to everyone because you need to know how a drug would work in the context of different genetic variations.

One drug may work really well in one demographic, and it might not work as well in another, so we really try to accrue.

This means recruiting and enroll Black men in prostate cancer clinical trials, which makes sense because they’re more likely to get the disease and die younger.

It’s important to look at these new VIP cutting-edge drugs and Black men could really benefit from them. As I mentioned before, some recent trials enrolled a lot of Black men. We call it race stratified clinical trials.

There were a few studies where one was looking at hormone therapy, one was looking at chemotherapy, and one was looking at immunotherapy. In all three of them, the Black men that participated in the trial had longer survival than men of other races and ethnicities.

When we looked at that, scientists like me who do health disparities research were like, “Wow, that’s so encouraging.”

At the City of Hope, we have a team of scientists and physicians and clinical research nurses, and statisticians who come together and think about diseases and ways to help people who suffer the most from that disease.

Talazoparib clinical trial

Alongside Dr. Rick Kittles, Dr. Tanya Dorff, who’s the Director of the Genital Urinary Program there, and Dr. Zijie Sun, who’s another prostate cancer researcher, we designed a clinical trial to use a PARP inhibitor called talazoparib. It’s a newer-generation drug that Pfizer makes.

This trial is also sponsored by Prostate Cancer Foundation and we’re going to be using PARP inhibitors in a racially diverse group of patients so we are going to have a third of the patients be white men, a third of the patients be Black men, and a third of patients be Asian-American.

The Asian population is very heterogeneous, so I just hate to throw it all into one.

Many Asian-American men actually do better with prostate cancer than white men. Black men do the worst. So we want to see how this drug works in different races. But we’re not just picking races just to see; there has to be some sort of a scientific reason.

Racial Differences in Androgen and Androgen Receptors

The reasoning there is an interplay at the cellular level between PARP and androgen receptor. Androgen receptor has some variations that affect its function.

Androgen and androgen receptors are crucial for prostate cancer cells to grow. That’s why if you get prostate cancer, one of the treatments is hormone therapy because we want to block androgen and the androgen receptor.

There are racial differences due to genetics where different trinucleotide repeats that exist in the antigen receptor. There’s different links, so they’re shorter repeat links and there’s longer repeat links.

Asian men, not just American, tend to have longer repeats, and African-American men tend to have shorter repeats. The repeat length may affect the men’s response to this PARP inhibitor with the talazoparib. We’re going to see.

The study just kicked off this past month and we’re starting to accrue patients. It would be one more drug in the arsenal because as I said, this is going to be offered to patients who already have metastasis.

They can do different drugs that are out there, but this PARP inhibitor could be something that’s extra added to their hormone therapy, and that’s what we’re looking at. We’re looking at the Talazoparib specifically with Abiraterone acetate at this point in time.

Developing targeted therapy according to race

That’s something that we could check in the future. We could look at their androgen receptor, look at your trinucleotide repeats, then we could say, look, you’ll be a great candidate for this drug in the future beyond clinical trials.

But it’s not going to target the shorter. It’s the same with everyone. We think that there may be differences in response in the androgen receptor and the trinucleotide repeats within that receptor, within that gene. But we don’t know what to expect.

It may work well for everyone, but if there is a difference, we want to tease that out.

This is a two-year study, and we assess the study. You don’t just start the study and then just let it go and check at the end. You’re constantly tracking your progress as it goes, so we should have a good idea by the end of the year.

Building trust in clinical trials

That to me is the most important part of it.

In the past 20 years, there has not been an increase in the number of Black physicians accepted into medical school. That’s the problem. It’s not making it through medical school; it’s getting accepted into it.

A study came out of Oakland last year that showed how much better the outcomes were and how much more the diseases were addressed when Black people went to Black physicians.

We look at it in Black maternal death rates and infant mortality, and we know that just by the presence of a Black nurse or a Black physician in the room, the mortality rates go down, just by them being in the room.

That is a lot to unpack on why that is, but there is a trust factor when you have cultural competency in the room. Race doesn’t have to match all the time as long as your physician is culturally competent and sensitive to different communication styles and cultural contexts. It can work just fine, but we know that there are still many barriers, for sure.

When they go into the office, the patients feel the bias going both ways. There’s bias on the part of the patient, and then there’s bias on the part of physicians.

»MORE: Learn more about the process of clinical trials from one program director

First of all, increasing the number of minority physicians, in general, would help. But what we like to do is to have a diverse team—diversity, in terms of race, gender, age, and occupation. We have physicians, nurses, scientists, and many of us who work within the Division of Health Equities at the City of Hope have personal ties to how we even got into this.

I got into this because of my dad, and so I’m speaking to Black men, and they’re saying:

- “Oh, I feel fine. I don’t have any symptoms.”

- “Really? Because my dad didn’t have any symptoms either.”

- “Oh, I don’t know if I get that done. I’m not going to have a normal life.”

- “My dad had that, and he’s doing great.”

That works on these teams who have personal ties, and so it comes across as more genuine, for sure.

We’re not just going to collect samples for research and just leave. We are there to help the men. We do actual prostate cancer screening in the community.

I know people freak out. We don’t do digital rectal exams in the community, but we do the blood tests, we provide the men their results and then we offer follow-up care and it’s not just at the City of Hope.

We partner with community clinics for men who may not have insurance or under-insured to make sure that they get that follow-up care, especially if their numbers are low enough that we think it could be caught early.

That’s really the goal of everything that we do. But, yes, the mistrust is a real thing and we try to tackle it that way.

Another way to really increase minority enrollment in clinical trials is just to provide access in communities of color.

Not everybody can travel to your main clinical trial center. I know at the City of Hope, we’re very fortunate to have community sites in Pasadena, Antelope Valley, or Santa Clarita, Pomona.

There are different locations to make it easier for patients to go from their neighborhood to a closer location to get treatment, which helps.

There’s financial incentives as well, and that can be controversial for sure.

Some of our trials offer them, and some of them don’t. But a lot of times, when you’re a cancer patient, getting to clinical trials is expensive. You and your caretaker have to call off work, you might have to get lodging, have transportation costs, and so a clinical trial can provide some financial incentive to help overcome that. It can really open the door for a lot of people.

Telemedicine as a tool

Telemedicine definitely has its pros and cons we’ve all learned during quarantine, for sure.

That translates to prostate cancer as well. If you don’t live close and have the technology and the app you need to communicate with your provider, it can give you access to perhaps more than you were exposed to before.

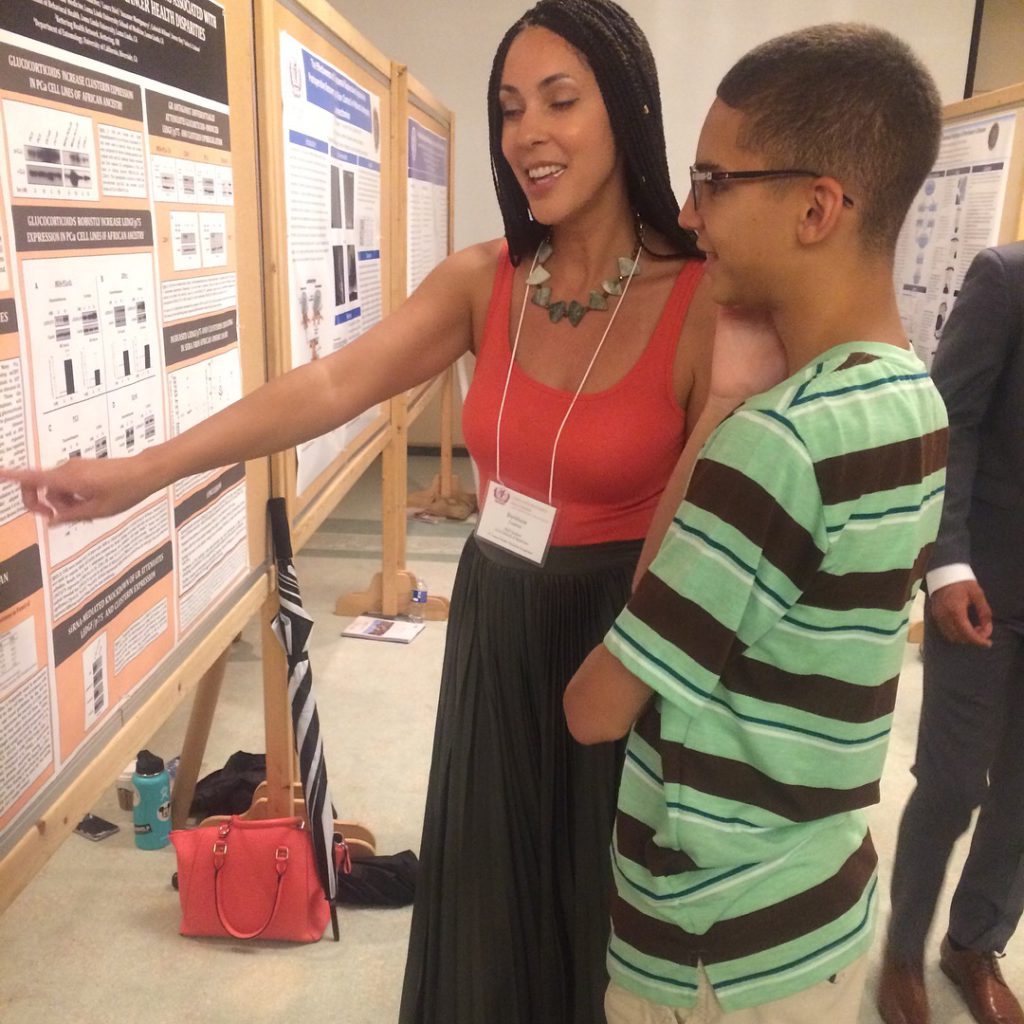

City of Hope Work in Communities

It’s our community-based prostate cancer program directed by Dr. Rick Kittles. I am lucky and blessed that he allows me to be the project coordinator for that. I work under him to recruit licensed phlebotomists. We recruit volunteers.

It is not hard to recruit volunteers because these events are the highlight of our week. They’re so fun. We get so much more out of these events.

Anything that we give back, we receive back in the energy of the individuals that we meet and we touch.

First of all, we provide education.

Let’s say we’re at a church. Usually, the pastor will let us get on stage for five minutes to say what we are doing and why it is important.

We know in the literature that, unfortunately, the men who are most at risk for aggressive prostate cancer don’t think that they are. So the first piece is letting people know they belong to the high-risk group.

Then a lot of men are afraid of the digital rectal exam. We let them know that it’s the PSA test now. You can get the DRE when you go to the doctor, but since 2017, you lead with the PSA.

A lot of times, when they find that out, they say, “Oh, okay. You don’t have to do that. Then I’ll do the blood test.” That’s the next part of it.

We also let them know that most of the time, with prostate cancer, you don’t have any symptoms. Men will be at Taste of Soul or the Long Beach Jazz Festival and are sitting there with their drinks and their cigars, and they’re, “I feel great. I feel great.” On the other hand, you might frequently be urinating at night.

We go into the communities, educate, interact, do the blood tests, and then follow up within two weeks. And we tell them, “Don’t freak out. That doesn’t mean you have prostate cancer. But either way, you just want to stay on top of your prostate health.”

We send every person an individualized letter. By individualized, it’s an official letter from the City of Hope. It gives them their PSA level. Based on their race and age, we translate to them what that means for them. Not everybody’s letter is going to look the same.

If they are at a younger age but they are showing a 2.5 or a 3 PSA, we’re like, “You really want to follow up and get this double-checked.” We follow up within two weeks.

If a man has very high PSA levels, we will call to make sure they got that letter. We tend to follow up after a few weeks for everyone who has elevated PSA, anyway, just to see, “What have you done with that?”

Many men find out and haven’t told anybody and they’re nervous to take the next step. So we help them with that.

Then we have social workers that help to navigate them getting to their next follow-up person. Whether it’s at the City of Hope, we would love to offer the different treatments that we have there.

But not everyone can travel that far, or maybe their insurance doesn’t allow them to. We partner with community clinics in the LA area where patients can go there as well.

Lessons from Community Work

I’ve learned how much people trust their doctor without knowing their personal risk. They trust their doctor knows their risk. It’s scary how often it doesn’t necessarily seem to be the case.

I’ll talk to men sometimes, and they’ll say, “Oh, I had that test done.” Then I’ll say, “You went and got the blood test?” They’ll say, “No.” Then I find out they’re talking about the colonoscopy. That’s one thing.

A lot of times, I hear, “I got all my blood work. My doctor does all my blood work every year.” Then I’ll say, “Well, did they include that in your blood work?”

A lot of times, it’s not included. They’re checking your blood sugar and your enzymes but not the PSA. Now that you have medicine apps on your phone, they’ll say, “No, I did it. My doctor ordered it.” They’ll pull it up. I say, “If you don’t mind, let’s look and see. What was your PSA?” Then it’s not in there, and then they’re like, “What? My doctor was not testing?”

It’s endearing how a lot of people do trust their doctor. Then it is sad to see sometimes they’re let down, but it’s like, “Now you have the tools. Now you email your doctor, and next time you’re in there, you let them know that you want to have this test, but actually, you don’t have to because we’re going to do the test now, and we’re going to give you a letter, and you can show your doctor.”

Hopes and prospects in prostate cancer research

I think we’re so close. When I got into this when my dad was sick, his doctor told him at that time, “Oh, you have a set amount of years.”

He’s passed that amount of years, and he’s doing well. We know he’s not curable still, but I hope to change that. When I got into this, I said, “I’m going to find a cure for my dad,” many people say. That’s the goal of a lot of scientists. They have a loved one, and that’s why they got into it in the first place.

I’m at a place at City of Hope where we have so many clinical trials, so many cutting-edge treatments, and we’re seeing patients that are really doing well. I just feel like we’re just at the cusp of it.

I’m just like, “Dad, hold on. Just hold on. We’re at the cusp of it.” I do think that it’s around the corner. I don’t think that it’s something that’s decades away. I think it’s sooner than we think and I’m really hoping that’s the case.

Being on both sides: Survivorship and cancer research

I was in science before I got cancer. My dad had cancer first. Then I was in science. But I was walking around with cancer for six months myself, and then I had to do chemo in the whole nine yards.

After that, it just completely changed my thought process and my approach. It changed my outlook on life, first of all. Everything I did became urgent. I don’t know if I’ll be here tomorrow. Everything is urgent.

One in two men is diagnosed with cancer, one in three women. I walk through life like, “Listen, it’s morbid as it sounds.” I’m like, “It’s not a matter of if you’re going to get cancer. It’s just like, ‘When? At what age?'” It’s just so common. We really need to get a handle on something, and I’m so glad we have so many scientists really dedicated to that cause.

It changed my outlook on life, and then it changed my outlook on scientific approaches. I used to sit in scientific meetings, and it’s like, ‘Oh, we can use this drug. Let’s try this and that.’

Sometimes I would open my mouth and say, ‘These are people. Imagine what all of those drugs are going to feel like.’

I know with my lymphoma, I had four chemo drugs at each session. That just was not fun. The idea of like, “You really want to be able to treat your patients with the least invasive method. You don’t want to go so hard on the pain all the time. You want to find something that works, but it’s not so toxic to the patient.”

Then I also think I know what it’s like to walk around with cancer and not know that you have it. You think it could be anything else, and that applies to a lot of people.

When I’m out in the community and people will say, “Oh, I don’t feel like I have cancer.” Sometimes you don’t feel like it, but sometimes you get used to those nagging little symptoms that have formed over a few weeks or a few months. You never want to go off of how you feel when it comes to screenings.

Another thing, because I’m a cancer survivor, I have to go to my oncologist. But that’s always so weird to me. I’m in the lab and working in the hospital then, “Oh, it’s now my turn to go to the oncologist.” It’s just always weird.

When I went, they said, “Listen, we want to do a colonoscopy on you.” I was young. I wasn’t 40 yet. I’m like, “Fine. Another test.” So I did it. When I woke up, they said, “You know what? We found several pre-cancerous polyps.” I was like, “What?”

I was so happy that I did that colonoscopy that young. If I hadn’t had lymphoma, they wouldn’t have thought to do it that young. Now I know. I don’t wait as long as other people. Now I’ll be referred for a colonoscopy much more frequently than anybody else.

Don’t put off symptoms. If your doctor thinks that you have a reason to be screened for something, don’t be afraid because trust me, you want to be diagnosed at an earlier stage and save yourself some of the hassles, please.

Especially with prostate cancer because it’s curable if you catch it early. That’s literally life or death. You want to screen for that sooner rather than later.

Approaching conversations on cancer risks

I try not to freak out on him all the time. He’s 17 so it’s like, “Oh, everything’s fine.”

Just the other day, he texted me and said, “Oh mom, I’m having an allergic reaction to like 30 things.” Then I responded, “Oh my gosh, what are your symptoms?” Then he didn’t respond. Then I’m calling his girlfriend, calling every everybody to see, “Is he gone into anaphylactic shock?” I just assumed the worst all the time.

He’s used to, “Oh, mom’s just freaking out,” but I look at every symptom as like, “Oh my goodness.” He did have some swollen lymph nodes at one point. I thought it’s lymphoma because it’s hereditary. But it was not the case.

I don’t really talk to him because I take action. We’re going to see what happens when he becomes an adult and has to make decisions independently.

At that point, he knew his grandfather, who’s my dad. He was like, “Oh, well, he has cancer, and he’s okay.” I don’t know if he thought, “Oh, she has cancer. She’ll be okay.”

He saw my hair fall out and he saw me being sick and tired from the chemo all the time, and he seemed okay.

On my final PET scan, the day that I found out that there was no evidence of disease, I sat him on the couch, and I showed him the picture. Because at that point, my son is a little nerd like me, so he knew like, “Oh my mom. I’ve seen her cancer cells. There’s two nuclei instead of one.” He knew what the cancer cell looked like.

I said, “Let me show you the PET scan. This one, this is the before, and this is the after.” He said, “[gasps] there’s nothing there.” I said, “Yes.”

His shoulders just dropped. It’s like he sighed. I didn’t realize, in that moment, that he had been walking around like this for months.

»MORE: Parents describe how they handled cancer with their kids

I saw it, and I was like, “Oh my gosh. It’s the little boy Beck that I remember that’s worried for you.” I don’t think he worries about it anymore right now. It doesn’t seem like it. That’s going to be something interesting to navigate as he will not be missing any screenings.

Normalize these conversations

It’s super important. I hope it changes with younger generations because my sister-in-law just beat triple-negative breast cancer last year during COVID, and she’s only 40, the same age as me.

When she was asked about family history, it was difficult to think who had what cancer? I know it’s the same with me. People died, and you don’t really know what they died of.

I hope that really changes moving forward and we become more open to sharing. I know in my family and my husband’s family, prostate cancer is not limited to one person. It’s rampant. The more you talk about it, the more you normalize it.

It’s difficult because a lot of older generations may have had prostate cancer, treatments are not the same as they were then. Maybe you hear horror stories, and then the younger guys are like, “Oh, I really don’t want to do it.”

We really try to stress that the testing is different, the treatments are different, the outcomes are different. The side effects after the treatments are different because things are improving. It is important to talk about it as a family to know that your individual risks are based on your family members.

Patient Self-Advocacy

I am just so grateful that Al Roker shared his story like that. A lot of people know him, and they’re going to think, “Wow. He had this, and he’s doing well. I can get a screening for this. If I get that diagnosis, it’s not the end of the world. I can come through it on the other side.”

It’s important, and I recognize that importance. When we’re out in the community, I recognize my limitation. I’m a woman. I don’t have a prostate.

I can talk, turn blue in the face, but it’s not a one-person job. I make sure I show up with people who have been previous patients because men want to see somebody they can relate to that has been through and come out on the other side.

I really think support groups are a great thing as well for men who have been diagnosed with prostate cancer. Just seeing men talk about it and be open about it definitely helps with anything in life, for sure.

We see it with the COVID vaccine now, too.

One person in the family gets it, you talk about it, now the cousins get it. I was the first person in my family. Now everybody’s gotten it. But it’s taken weeks and weeks to get to that point. That’s an example of you just talk about it and then it normalizes it for everybody else.

Message to Black men cancer community

Well, that’s something I hear in the community a lot too. Men will say, “Oh, I don’t want to have this treatment because I’m afraid that I won’t be able to have sex anymore.” That is true for a lot of different treatments.

One thing I tell men, it’s funny, but it’s not, but I’ll say, “Listen, if you don’t treat it at all, you won’t be able to have sex anyway, and you’re definitely not going to have sex when you’re six feet underground. It’s just not going to happen.” I make sure that they know that, but that’s just more on the joking side.

There are nerve-sparing surgeries offered now where results are not the same as they were 10 years ago. Your chances of regaining that function are so much better. Al Roker spoke about how he was able to regain that function. So don’t let that hinder you.

At the same time, I’ve been a patient, and I firmly believe that it’s the patient’s choice. Some patients decide, “I don’t want to do any treatment.” It’s their life, and that’s totally fine.

I’ll never forget when I spoke to a man who had a very elevated PSA and a Gleason of 9, and he was like, “I don’t want to have anything done.”

He was in a support group, and other men—it was a room of all black men —were telling him, “Oh, I had this treatment, and I had that treatment,” and at the end of the day, he was like, “I just would rather just see what happens, and I’m just going to live with my decision.”

You just have to respect that at the end of the day. I don’t know if I could have done that before I was a patient myself.

That is an example of you just wanting somebody to be able to make an informed and educated decision.

If you know all that and that’s what you want to do, do you boo. Because you’re going to have to live with that. You should be allowed to make your own choice.

Read Other Prostate Cancer Stories

Jamel Martin, Son of Prostate Cancer Patient

“Take your time. Be patient with the loved one that you are caregiving for and help them embrace life.”

Joseph M., Prostate Cancer

When Joseph was diagnosed with prostate cancer, the news came as a shock and forced him to face questions about his health, future, and faith. He shares how he navigated his diagnosis, chose robotic surgery, and learned to open up to his loved ones about his health.

Rob M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Burning sensation while urinating, erectile dysfunction

Treatments: Surgeries (radical prostatectomy, artificial urinary sphincter to address incontinence, penile prosthesis), radiation therapy (EBRT), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy or ADT)

John B., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9, Stage 4A

Symptoms: Nocturia (frequent urination at night), weak stream of urine

Treatments: Surgery (prostatectomy), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy), radiation

Eve G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels detected during annual physicals

Treatments: Surgeries (robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy & bilateral orchiectomy), radiation, hormone therapy

Lonnie V., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Urination issues, general body pain, severe lower body pain

Treatments: Hormone therapy, targeted therapy (through clinical trial), radiation

Paul G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery), radiation, hormone therapy

Tim J., Prostate Cancer, Stage 1

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery)

Mark K., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptom: Inability to walk

Treatments: Chemotherapy, monthly injection for lungs

Mical R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 2

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level detected at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Jeffrey P., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; routine PSA test, then IsoPSA test

Treatment: Laparoscopic prostatectomy

Theo W., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level of 72

Treatments: Surgery, radiation

Dennis G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9 (Contained)

Symptoms: Urinating more frequently middle of night, slower urine flow

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Lupron)

Bruce M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4A, Gleason 8/9

Symptom: Urination changes

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Casodex & Lupron)

Al Roker, Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7+, Aggressive

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level caught at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Steve R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4, Gleason 6

Symptom: Rising PSA level

Treatments: IMRT (radiation therapy), brachytherapy, surgery, and lutetium-177

Clarence S., Prostate Cancer, Low Gleason Score

Symptom: None; fluctuating PSA levels

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

More Medical Expert interviews

Dr. Christopher Weight, M.D.

Role: Center Director Urologic Oncology

Focus: Urological oncology, including kidney, prostate, bladder cancers

Provider: Cleveland Clinic

...

Doug Blayney, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in breast cancer | HER2, Estrogen+, Triple Negative, Lumpectomy vs. Mastectomy

Experience: 30+ years

Institution: Stanford Medical

...

Dr. Kenneth Biehl, M.D.

Role: Radiation oncologist

Focus: Specializing in radiation therapy treatment for all cancers | Brachytherapy, External Beam Radiation Treatment, IMRT

Provider: Salinas Valley Memorial Health

...

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

...