Robyn’s Stage 2E Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Story

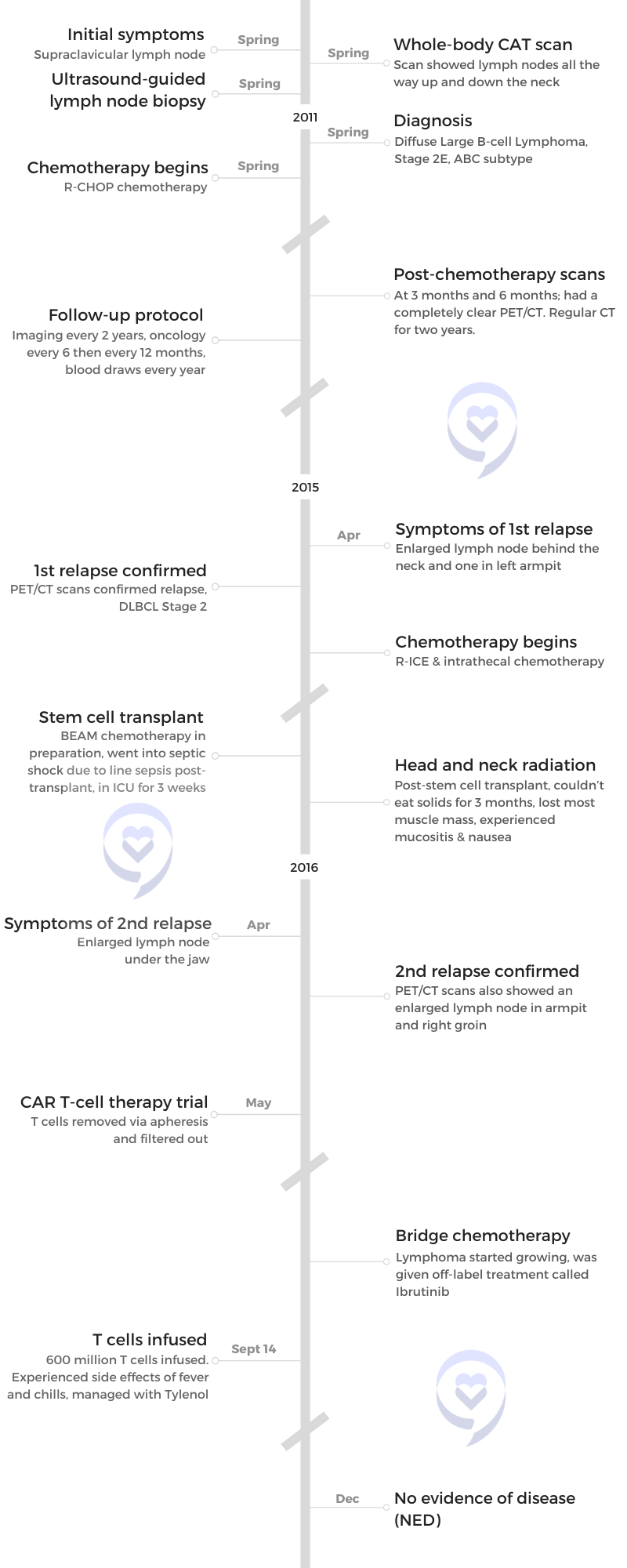

Robyn was diagnosed with Stage 2E Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, ABC subtype. Four years after going through R-CHOP chemotherapy, she relapsed and went through more chemotherapy, a stem cell transplant, and radiation. She relapsed a second time only 9 months after therapy. This time, she joined a clinical trial for CAR T-cell therapy.

She shares her experience with different treatment modalities and advice on looking for clinical trials.

- Name: Robyn S.

- Initial Diagnosis:

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

- Stage 2E, ABC subtype

- Initial Symptom: Supraclavicular lymph nodes

- Initial Treatment:

- R-CHOP chemotherapy

- First Relapse:

- 4 years later

- Lymph node at the back of the neck

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy: R-ICE, Intrathecal, BEAM

- Autologous stem cell transplant

- Head and neck radiation

- Second Relapse:

- 9 months after therapy

- Treatment:

- CAR T-cell therapy trial

- Bridge chemotherapy: Ibrutinib

- Remission:

- Lymph nodes gone within 1 week of getting CAR T-cell therapy

My biggest contribution to medicine is probably not as a physician but as a patient and that’s okay. I’m good with that.

I have been given a second chance at life and it’s an unusual experience for everyone. I cherish it and I enjoy every minute.

- Pre-Diagnosis

- Initial diagnosis

- Breaking the news to the family

- Treatment

- Follow-up protocol

- First relapse

- Treatment

- Second relapse

- Treatment

- Remission

- Post-CAR T-cell therapy

- Words of advice

- Role as a physician-patient

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

I’m really nervous I have cancer. Right [on the collar bone], it’s pretty much never benign.

Pre-Diagnosis

Tell us about yourself

Until 2011, I was a very healthy practicing physician with three young kids. I exercised every day, ate right… I probably worked too much. As a mother with three kids, [with] soccer practice and swim lessons, I was probably a little tired but other than that, very, very normal.

Initial symptoms

In the spring of 2011, I was watching TV and I realized that I had a supraclavicular lymph node, which is a lymph node above your collarbone. Given that I’m a physician and a radiologist, [I know] that is always abnormal. It’s usually a sign of some type of cancer — most likely ovarian cancer or lung cancer. That was a really startling realization with no other symptoms — no weight loss, no fevers, no nausea, nothing. Just an enlarged lymph node.

I turned [to] my husband [as] we were watching TV with the kids and said, “I have this supraclavicular lymph node. It’s always abnormal. I’m really nervous I have cancer because it’s always abnormal.” He looks at me [and said], “It’s nothing. You just see too many people with cancer,” because that’s what I do for a living. I do a lot of oncologic imaging, mammography, and PET/CT.

It was one of those situations where I just [turned] my neck and I realized, “Oh my, I have a node.” In the axilla, sometimes the neck, they could be benign. But right [on the collar bone], it’s pretty much never benign.

The next day, I went to work, went to see a friend of mine who is a surgeon, and he’s like, “You have a lymph node so you need whole body CAT scans.”

The minute I looked at [them], I knew I had lymphoma. It was really stunning to actually see your own CAT scan and see that pathology.

Being a physician-patient

It was weird. I’m a radiologist. I read CT scans for a living.

I went to a surgeon who ordered these CAT scans and I had the CAT scans done. He started it from [the collar bone] all the way down to my pelvis because most likely it was an ovarian, stomach or lung cancer. I looked at the images and I didn’t see any cancer there but I saw all these lymph nodes in my neck.

I got back on the scanner and had them scanned a little bit higher up. Sure enough, I had lymph nodes all the way up and down my neck. They weren’t palpable but the minute I looked at [them], I knew I had lymphoma. It was really stunning to actually see your own CAT scan and see that pathology.

The waiting is the hardest part.

Initial diagnosis

Realizing you have cancer

I was sitting there healthy. I had no symptoms, no significant family history, nothing. The only thing I had was one palpable lymph node, which was 14 millimeters. It wasn’t that big. It’s just that I do this for a living.

I have probably hundreds of lymph nodes in my neck. There [were] a bunch of lymph nodes behind my nose. I have allergies and at that time, I had some allergy symptoms — probably the symptoms were really from the lymphoma that year — but it was nothing unusual for me.

But to realize that I had cancer then it’s, “Okay, I have cancer. I wonder what kind of lymphoma it is. I hope it’s a Hodgkin’s versus a non-Hodgkin’s because Hodgkin’s has a better response rate.”

I told one of my partners and [literally] the next day, I had a lymph node biopsy performed at work. One of my partners did an ultrasound-guided lymph node biopsy, which I do all the time. Knowing that it’s in the neck, you put a needle and you take some cells out.

I looked at them with a pathologist under the microscope and I asked him if there were Reed-Sternberg cells, which are what you see with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He said, “No. I just see B cells. I think you have B-cell lymphoma.”

It was tough because this is somebody I work with all day. My partners are doing my biopsy. One of the pathologists is looking at this and says, “You have lymphoma.” Then on Monday, he called me and gave me the subtype.

Because I was diagnosed with something called diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which is a very aggressive lymphoma, I saw an oncologist that week. I had a port put in and the week after that, I started standard chemotherapy, which is called R-CHOP.

Waiting for more answers

Tom Petty said it the best. The waiting is the hardest part and that’s what I [say] to all patients who are going through this now. You’re sitting there, you’re new at this. I’m a radiologist. I’m not an oncologist. I know a lot but I did not at that point [know] that much about diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

You’re waiting, your oncologist gives you statistics, and you don’t even hear them and try not to focus on [them]. How do you tell your kids? How do you think chemo is going to go? It’s very daunting, even though I’m in the business, so to speak. The thought of having chemotherapy and having all these procedures done.

One of the chemotherapy agents is called Adriamycin, which is called the Red Devil. Most people have heard about this one and dread that. You wonder, how am I going to do with this? Am I going to be able to function? Am I going to be sick? Of course, you do lose your hair, that was 100% told to me, but it’s scary. Then you’re going to do all these chemos and are they going to work or not? Are you going to survive? You don’t know. You just don’t.

Getting the full diagnosis

With the staging, I had to have all the CAT scans in a PET/CT [and] a bone marrow biopsy, which is unpleasant. I was a stage two, technically stage 2E because I had some lymph nodes behind my nose and something called Waldeyer’s ring — E being extranodal. It makes the diagnosis worse.

Then I had a subtype and that’s sort of controversial. The typing of lymphoma has changed. Back then, I was diagnosed as a germinal cell, but later, I was diagnosed as an ABC subtype. I think it was a mixed subtype. It doesn’t really matter that much. They all suck.

The oncologists do tell you what your percentages are, that’s really part of their job. You need to have some expectations. I’m an optimistic person, so I was, “Okay, fine, I’m healthy. I’m going to do great.”

There are certain types of lymphoma that are worse than others and it’s a process to go through. I remember my oncologist telling me, “If this chemo doesn’t work, we’re going to do something called salvage chemotherapy.” I remember looking at him and saying, “Nope, we’re not going to do salvage. I’m not going to need salvage, not doing it.” He just smiled and shrugged his shoulders, “Well, I just have to tell you that.”

You’re going to do all these chemos and are they going to work or not? Are you going to survive? You don’t know. You just don’t.

Breaking the news to the family

That was the hardest part. My husband, I remember talking to him the Monday when the pathology came back. My biopsy was the Friday before Mother’s Day — Mother’s Day traditionally is not a great day for me. I’ve had three Mother’s Days where I was diagnosed with cancer.

On Monday, I got the final results and I remember talking to my husband [while] walking around the neighborhood. We were both just crying. People were looking at us thinking [that] we’re getting a divorce or something. Then to have to tell the kids.

The kids were, at that point, 18, 17, and 13. My youngest child actually has a physical disability. He’s fine but he had just finished a major surgery for leg lengthening. My daughter has anxiety. My middle son is very academic, intense, [and] scientific. When I told all the kids, he was immediately on the computer looking everything up. My daughter was in denial. My son was very upset. It was just hard.

‘Hang in there with me and I think everything’s going to be okay.’

I had two going to college at that point and one was in middle school. They’re older but they’re still babies.

Telling your kids

I said, “Mom has a bad diagnosis. I have cancer but that doesn’t mean that it’s going to kill me. I’m going to take therapy, lose my hair, [and] potentially going to be very sick. Just hang in there with me and I think everything’s going to be okay.”

I think for the younger kids, it’s harder with the hair loss in the way your appearance changes and there’s nothing you can do about it. [With] the chemo I had or anybody who has intense chemo, you lose your hair, your eyebrows, and your eyelashes, but the kids were very supportive. I just think they were nervous.

I don’t know if there [are] any good ways to do it. There are some books out there for younger children like mom has cancer or dad has cancer. I think that might be a good way to do it with younger people, but being optimistic is what we did, what we’ve always done.

We did a family vacation. We didn’t let it stop us.

Treatment

Living with cancer

I had six rounds of CHOP. It’s very intense chemo. I would have the chemo on Friday [then] I would go to work on Tuesday in the middle of CHOP.

We actually took a family vacation to Alaska. I booked a vacation. My counts were okay. I talked to my oncologist [and] I found an oncologist in Anchorage that could cover any emergencies. We still took our family vacation. I have pictures of me out there, halibut fishing with my head wrap on, and we still did all this family stuff.

I was careful. Obviously, it’s Alaska. You weren’t around a lot of people so I wasn’t that worried about infection. I was a little tired [so] I would take some naps. We didn’t let it stop us.

Anybody who’s going through therapy, I’m telling you, that was amazing, to have some food, especially for kids.

R-CHOP regimen

Think about chemotherapy now versus when I was in medical school. They actually gave you a lot of antiemetics [or] anti-vomiting medicines ahead of time, which makes you feel weird but it keeps you from throwing up. We had all of that.

They give you either Neulasta or Neupogen shots after chemotherapy that keep your blood counts up so you don’t get as anemic and you hopefully don’t need any blood products. Some people need some transfusions; I didn’t. It’s just a lot of shots.

The infusion itself would take all day. I would have friends come in about every 2 hours in shifts to talk to me.

The other thing that people did is bring food. People brought meals two or three times a week, which was really nice for the family. Anybody who’s going through therapy, I’m telling you, that was amazing, to have some food, especially for kids.

I felt nauseous all the time. I compare it to morning sickness but I never was violently ill. Now, everyone is different. I think I tolerated it pretty well.

The other thing about it is they give you a lot of steroids. A lot of people get all puffy. You gain weight and then you’re nauseous [so] you’re not eating then you lose weight. It’s up, down, up, down. One week, you look puffy and moon face, the next week, you look skinny.

Overall, though, I did well but I had really good physicians. I had friends to help. I didn’t feel great, but I didn’t feel totally awful, so that was a good thing.

I followed everything I was supposed to do.

Side effects from R-CHOP chemotherapy

It always gets worse, mainly because your blood counts keep going lower. You become more and more anemic no matter how many Neupogen or Neulasta shots you get because there’s a cumulative effect on your bone marrow.

I followed all my doctor’s directions. I took certain supplements when they told me to and I followed everything I was supposed to do.

As far as the shots, I think that’s also key for people. I took all the anti-nausea medicines. They would say to stay on a schedule of anti-nausea medicines. I don’t like to take pills [but] I followed everything they said. I think that’s part of the key too.

You also have a more bland diet. They have a nutritionist that meets with you and I think all those things are helpful.

Integrative medicine

My advice to patients is that when you’re at a cancer center and if they have nutritionists or psychotherapy, that’s great. Sometimes centers have things like meditation and massage. There are all these things that cancer centers are doing as part of their integrative treatments and I highly recommend [them]. When I went through R-CHOP 11 years ago, this was pretty new. Now, at least where I work, it’s a standard of care at the center but patients have to take advantage of it.

No one should be embarrassed to ask. I was very happy to see an oncology therapist because to face a life-threatening disease is difficult for most everyone, I would think. It’s a nice service that a lot of these folks offer. I think it’s very important.

Follow-up protocol

The follow-ups were done once you had a clear PET. [For me], it was after three months of therapy and six months of therapy. I had a completely clear PET/CT. After that, they followed me for two years with just regular CT.

I had actually gotten beyond any type of imaging because at two years, they stopped imaging. Theoretically, if you make it to two years [of] complete remission for diffuse large B-cell, there’s a high likelihood you’re cured.

I would actually go see my oncologist first. It was every six months for a while and then it was every year until three and a half years [to] four years. That was the standard follow-up.

[I also had] yearly blood draws. If you go see an internist, a lot of times, they do blood draws. I followed the standard two years of imaging then every six months oncology, every year oncology, and yearly blood draws until I relapsed four years later.

Sure enough, I relapsed.

First relapse

Unfortunately, I relapsed at four years and that was on [a] clinical basis, not based on scans.

Sort of the same thing happened to me. We were in the spring of 2015, April 2015, we were walking around a yard and I realized I had an enlarged lymph node. This one was behind my neck and that’s not a typical area to have inflammation from infection. I didn’t have any cuts or anything. I had no reason to have a prominent lymph node. I went to see my doctor and they ended up doing a CAT scan.

It’s funny how you remember these things exactly. My husband and I were walking around our backyard, looking at the garden. I realized I had a large lymph node again in [the] back of my neck and I wasn’t sick. I immediately thought about lymphoma. Once again, my husband goes, “You’re working too much. You see this all the time. It’s probably nothing.”

I made an appointment to see my oncologist because I felt this node had not been there before. Sure enough, CAT scans, PET scans, I relapsed and this time, it was still stage two. Once again, all the lymph nodes were in my neck and I had one lymph node in my left armpit but it wasn’t big.

I’ll always tell people who have a life-threatening condition, particularly like mine: it is totally reasonable to get more than one opinion.

Getting a second opinion

I actually got several consults from where I live because I live at a major tertiary care center and I called my medical school, which is another tertiary care center. Then I went to MD Anderson for a year. I got three different consults and even a fourth.

A consultant was sent to Nebraska, which is an area of lymphoma. I had been out four years and it was unusual for me to relapse. I wanted to know what else I could have.

At the time, I was just trying to stay alive. I was going to take my best odds. Now, in retrospect, I wish I hadn’t had the radiation, but at the time, I had talked to the specialist. At some point, you actually have to go ahead, have faith, and believe in who you’ve consulted.

I actually had consulted more than one doctor and one thing I’ll always tell people who have a life-threatening condition, particularly like mine: it is totally reasonable to get more than one opinion. That actually helped me because I had several institutions saying the same thing and that I think was helpful. If it’s just one institution, I don’t know if I would have been as comfortable.

Treatment

R-ICE chemotherapy

Back then, I asked about natural killer cells because it had been in the news, but there was nothing available. Everyone convinced me I needed to have a stem cell transplant. I had two rounds of R-ICE, which is much more intensive chemotherapy. It requires you to be in the hospital.

The “I” part of it makes you feel really lousy. During the middle of the night, you have to eat ice cubes to prevent your mouth from getting all ulcerated.

Intrathecal chemotherapy

I actually had to have two rounds of intrathecal chemotherapy, where they do a spinal tap, put chemo into your spinal canal, and have it go up to your brain. Because I’d had the extranodal site initially, they thought I should prevent from getting CNS lymphoma, which was a good recommendation.

Once that was complete, I went into remission.

Side effects of chemotherapy

R-ICE chemotherapy

R-ICE is very difficult chemotherapy for most people. It results in a lot of severe nausea [and] a lot of mouth ulcers. The majority of people end up needing blood transfusions afterward. I did not. I was unusual. You have to take the Neulasta [and] Neupogen shots.

I was also able to work some during that. But I’m really unusual.

When you have pain, you take pain medicine.

Intrathecal chemotherapy

The intrathecal chemo was uncomfortable, but it wasn’t any worse than R-ICE. The thing that was unusual for me was getting the huge catheter that they had to use for the transplant, which is a tri-lumen catheter that goes in your neck. It’s really, really big. I have a bigger scar from that than I do my port scars. I’ve had ports every single time. I’ve had two and then I had this huge catheter.

With this, the only way you could shower is to put plastic all over yourself so you don’t get this catheter wet. It required some medical knowledge or at least to be instructed with directions on how to take care [of] a patient who has these things.

If you have a family member that’s going through this, you’re going to have to have somebody that either has some medical knowledge to start with, is a nurse, or is willing to undergo training and is not squeamish. I can only do so much by myself.

Just like with the R-ICE, because it’s a hospitalized chemo and a lot of people have blood transfusions and they’re very, very sick afterward, they’re [unable] to eat. It’s just very difficult for the caregivers as well as the patients.

Fast forward to the stem cell transplant, most people feel pretty lousy — not initially, but once your white count’s low. In my case, I had a fever and everything. A lot of people have mouth ulcers. They can’t swallow very well. It’s very difficult for the family members to watch that.

The nurses and the staff might give the patient pain meds. I know I had some narcotics when I was in the hospital, so some stuff I don’t remember. I’m glad I had narcotics. I had no problem. When you have pain, you take pain medicine. I don’t remember some of the stuff. I know it was very difficult for my husband and my older son who were there at the hospital. Very traumatic for them.

BEAM chemotherapy

BEAM chemotherapy is just miserable. The worst thing is the Melphalan (the last part of it) causes, quite frankly, really bad diarrhea, like dysentery diarrhea. It’s just the way it is. Everyone survives it. It wasn’t pleasant.

The side effect of Melphalan is tough. A lot of my friends were in the Peace Corps in Africa and they said you haven’t really been to the Peace Corps unless you’ve had diarrhea where you couldn’t make it to the bathroom. I always said I feel like I’m in a Peace Corps. Honorary member.

Managing side effects

When I was there, they have a thing where you would walk the halls. I’m a big exercise proponent and when you walk, it actually helps the stem cells engraft. I really cannot reiterate. I did follow all my directions. The nurses say you need to walk and even if you feel like total garbage, I’d be there with my little IV pole walking around.

Before I had the BEAM, I was even on an exercise bike. But then once you’ve had the BEAM and you’re really, really sick, it’s very hard to do anything.

Autologous stem cell transplant

They actually took my stem cells out, which they do via something called apheresis. They hook you up and they take cells from one arm, filter them through a machine, take them out, and freeze them. Then you get admitted to the hospital for your actual stem cell transplant. They do myeloablation, where they basically blast your bone marrow.

There [are] different ways to do it. I had something called BEAM. You can do it with total bodily radiation. There are some other protocols, but it’s just horrible chemo. It totally obliterates your bone marrow. It leaves you with no white cell count and also a very high risk of infection.

I got an infection so I ended up with septic shock.

At the point, when you have had all your chemo, they give you your stem cells back. It’s really a stem cell rescue and then they wait for your stem cells to engraft in your bone marrow and start making new bone marrow cells, like blood cells and platelets. Until then, they give you transfusions and you hope you don’t get an infection because you don’t have any white cell count.

Going into septic shock

I got an infection so I ended up with septic shock. I was in the intensive care unit and I had a fever [and] septic shock. My blood pressure was zero. I was on something called pressors just to keep my blood pressure up.

I actually still have an aneurysm in my radial artery from having an [arterial] line. There’s nothing you really can do about it. You can just feel it. It’s not that it was done poorly. It just happens.

[Septic shock], it’s pretty common. People get sick. Sometimes they don’t get as sick as I did, but I wasn’t intubated. I had [a] high fever and a positive blood culture. What had happened is the line I had, even though they were using all aseptic techniques, had gotten infected.

They took the [central] line out, gave me all these antibiotics, and I got better pretty quickly. Then my cells engrafted, I started making my own red blood cells [and] my own white blood cells. I got out of the hospital in three weeks, which was pretty quickly. But I was sick. I was really sick.

I don’t remember some of it. My husband and people came to check on me. I was out of it. Evidently, I argued with the ICU doctor about which pressor to use, which I think is pretty funny. I was totally out of it and I’m arguing with the person who’s an expert. I’m a radiologist and I’m telling him which pressor I want. They must have thought I was really obnoxious.

They probably aren’t used to the bone marrow transplant patient arguing about the pressors, which, now I look back, is sort of funny. But the bottom line is they took great care of me and I’m here and I’m alive. Then I went home.

Post-stem cell transplant

You have to be very careful after a bone marrow transplant because even though I had a few white cells, you’re likely to get an infection. You’re not allowed to be around anybody.

The worst was you can’t eat berries — I love berries, like blueberries, strawberries, all that kind of stuff — because of the skins. You couldn’t have anything with skins. You had to be very careful. No salads that weren’t triple washed. All of that for 100 days.

Then I had to go for head and neck radiation.

Head and neck radiation

At MD Anderson — even some people from Sloan Kettering because I had relapsed late but had pretty much all been in my neck and even in my nasopharynx — they want to do something called consolidate the bone marrow transplant. Because I was young and healthy, they treated me extremely aggressively. Not everyone would be treated like this, but they wanted to save my life and I agreed.

They said that if I had the head and neck radiation, it would increase my chance of survival up to 5%. My chance of remission after [a] bone marrow transplant was only about 35%. With the head and neck radiation, they said it might increase to 37 or 40. It was our decision to proceed. I followed the recommendation of all of the physicians.

Head and neck radiation is two thumbs down. It’s not fun but you just do what you have to do. I have a lot of friends who’ve had head and neck cancer and they’ve had to experience this.

Most just choose to have something called IMRT, which is a focused radiation therapy, where they actually, in my case, were focusing on where I’d relapsed on the side of my neck and my nasopharynx. They can control the beams to a certain extent, but there is something called scatter radiation. No matter what, even though it’s controlled beams, you’re going to get some scatter and some other side effects.

They make a mold of your head. It looks unbelievable. You lay on the table, they literally screw you down to the table so you won’t move, then they do the radiation. For lymphoma, they usually use a dose of about 30 to 35 gray. Meanwhile, with head and neck cancer, they use double that dose, 70, 75 gray.

I literally survived on smoothies for about four months after [radiation].

Side effects of radiation

Head and neck radiation is very difficult. From my radiation, I was supposed to have very few side effects because it was only over [the neck area]. But unfortunately, I had a lot of side effects.

I had mouth ulcers. I couldn’t swallow solid food for almost five months after having had radiation.

It affected my salivary glands. I just couldn’t swallow. It was very difficult to eat anything.

I literally survived on smoothies for about four months after that and I was supposed to get 36 treatments. I ended up getting 30. They just titrated it down because I had so many symptoms.

The other thing is because of the scatter radiation, it got part of the base of my brain and I developed worse nausea than I’d had through any chemo. Vomited all the time. It was terrible. But again, I did what was recommended. I got the minimum dose for consolidation and I just thought I could take it. I tried to be positive and I made a real effort.

This is the other thing: to eat protein and try to keep my weight up the best I could. To give you an example, I started with a BMI of 22. By the end of radiation, I think I was down to 15, 14, about 103 pounds. That’s really skinny for me.

I think [the intense side effects were] an outlier situation. Medicine is difficult. The people doing my therapy were also my friends and they actually wanted me to get this treatment. I wonder sometimes in the nicest way whether they didn’t tell me about everything or maybe I didn’t hear. I only heard what I wanted to hear, which sometimes happens as a patient. But I know some of the things, especially nausea, was an unusual side effect.

I went back to work three months after my bone marrow transplant, just a week after radiation. I would go [get a smoothie] in the morning. I’d get one of these massive things with protein powder and I would just take it to work.

I don’t think it’s the most healthy thing and there’s going to be someone [going], “Oh, there’s too much sugar.” At this point, I needed calories. I would have some protein, and I could drink that all day long.

Managing the side effects of radiation

I did get an alternative therapy. I had acupuncture. [There have] been some studies [where] if you have acupuncture in your salivary gland, it helps promote the return of your salivary gland function. I think it helped. It didn’t hurt. It was uncomfortable but I was willing to do whatever I could to return to a normal life.

I also kept walking. I wasn’t able to do much physically at first, but I would walk around one block, then I would walk a mile. I’d walk two miles, three miles. I gradually worked up to that to try to maintain my muscle mass and my functionality. It was a determination for sure.

I had relapsed. Lymphoma was back nine months after therapy and I really didn’t have that many choices.

Second relapse

I went on a vacation with my youngest child as he was graduating from high school. While we were on that vacation, I felt another enlarged lymph node. It was actually under [the jaw]. I knew I had relapsed.

I immediately went to my oncologist up at the center where I had the bone marrow transplant. My husband was with me. I had a PET/CT. I stepped off the table, looked at the PET/CT, and knew I’d relapsed. Not only was this hot, [but] I [also] had something in my armpit and now I had something in my right groin, a big lymph node.

I had relapsed. Lymphoma was back nine months after therapy and I really didn’t have that many choices. I would say three times is not a charm for lymphoma.

The interesting thing is my oncologist looked at me and goes, “Hey, you’ll have an allogeneic transplant. You’re Caucasian, it’s not going to be a problem. You’re going to have a match.”

As it turns out, I’m actually multi-ethnic — given my heritage and how you just don’t know by looking at somebody — and, of course, I had no matches. No one [is] even close and I have no siblings.

I didn’t want to have an allogeneic transplant anyway. I had been doing some research online and I initially wanted to have some killer T cells or something instead of stem cell, but there was nothing available.

Differing treatment recommendations

My bone marrow transplant guy wanted me to have a bone marrow transplant and I don’t want to do that. CAR T is so new. This transplant physician, who’s actually very famous, said, “Look, you’re young, you’re healthy, you survived. You’ll do fine.” I said, “This was the worst experience. I don’t know if I’m going to survive. I don’t want to do this again.”

I had another friend who was very experienced say you shouldn’t do this. I have a friend who’s an oncologist, he’s about 15 years younger than I am, [who] said, “Hey, this is pretty good stuff. I think you’ll do well with this.”

Treatment

CAR T-cell therapy trial

Now there was something called CAR T-cell therapy and I had seen that online. I went on www.clinicaltrials.gov and we started researching trials for CAR T. I found one phase, one trial with something called the JULIET trial, phase one, where they had 25 patients and 12 had survived and got into remission. That was probably the best odds that I would ever have. I wouldn’t have [that] kind of odds with an allogeneic transplant.

We started looking for phase two trials for the JULIET trial, but also for the Kite trial, and for Juno. There were two other products and we started searching for those trials.

I had to do all the research myself and this is [what] I want to really stress. I had no advantage here, no connections. All we did was get online. My husband and I went on this clinicaltrials.gov site. We emailed every single center that was doing CAR T. We called them and we started looking. We’re trying to find a space.

I had a little blurb. I put my history in about three paragraphs because I knew I qualified for everything. I had no comorbidities. I just had lymphoma and nothing else wrong with me, so that’s perfect for a clinical trial. They don’t want to have any of the mitigating factors. They want to see just how the trial works, which is what they want for these trials. That’s why people are excluded from trials because they don’t want to muddy up all of the info when you have so many other conditions.

To make a long story short, a space opened up literally. We found out about the space on a Wednesday, I flew to the center — which was actually in Ohio, I live in North Carolina — on Monday. We signed paperwork to agree to do the trial. I was accepted.

Within the next week, I came over and they did something called apheresis where they filtered out my T cells, just like you’d filter out stem cells. They put a catheter in one arm then they put it through this machine. They filter out T cells and return the cells back to your body. Then they sent the T cells out to be modified.

The cool thing about CAR T-cell therapy is it’s your own immune system… This way, you actually modify someone’s own immune system to fight cancer, which is really brilliant.

How CAR T-cell therapy works

CAR T is really amazing. The patient’s T cells are removed from the patient with apheresis. They’re filtered out. Think of these little T cells as little Pac-Man and in these little cells, you take a viral vector — it’s like a deactivated virus — you insert a protein onto the top of that cell. That little Pac-Man binds to whatever that protein is on another cell and gobbles it up or blows it up, whichever way you want to look at it.

When you have lymphoma, the protein is called CD19 but then other lymphomas have a CD30. There are some leukemias and lymphomas that have a CD20 or 22. Now there are trials for solid tumors, like HER2-positive breast cancer. HER2 is a certain protein that these breast cancer cells carry and so they can make a CAR T to fight HER2-positive breast cancer.

The cool thing about CAR T-cell therapy is it’s your own immune system. Right now, our standard chemo treatment for cancer is actually really barbaric. You either poison it, you cut it, or you burn it — that’s the way we treat cancer. This way, you actually modify someone’s own immune system to fight cancer, which is really brilliant.

The T cells can cross the blood-brain barrier. What’s so important is that there are certain tumors that have brain metastases, like lymphoma. A lot of people get lymphoma and it spreads to the brain. This can actually cross that and treat it in the brain. It can treat metastatic breast cancer [in] the brain. They’re using it for all sorts of other things.

Clinical trial paperwork

I did not read every single paper. We went over some of the guidelines. We went over the requirements and this is actually standard for T-cell. I had to be within 30 minutes of the institution. I had to go back for follow-ups. This was a series of things I had to do and I agreed with that.

I knew the results of the phase one clinical trial and this was the phase two trial. The investigator shared phase one. We went over side effects and a lot of that was just one on one.

This investigator, who is a very young investigator, she’s very pro-CAR T. I remember her looking at me and saying, “You are the perfect candidate for this. You’re healthy, your bone marrow is good. You just happen to have lymphoma.”

Costs of joining a clinical trial

Each trial is different. My trial covered the actual drugs and any medical treatment related to my therapy but did not cover the cost to get into the trial, which meant another bone marrow biopsy, some other CT scans, lodging, any kind of lost work, or the caregiver.

My husband, at that point, was not working so he was able to go up with me. We got a VRBO flat and we stayed there. It was very economical that way. People bring that up and some of the trials will pay for that, some of them won’t. Insurance companies will usually pay for lodging for a family member and the patient around a bone marrow transplant, but not for a clinical trial, in my experience.

A lot of this is based on some type of your own financing. With us, we had to finance the car, the VRBO, the caregiver, my food, and then my insurance company covered some of the initial testing, which would have had to be done anyway if I was going to have an allogeneic transplant.

Bridge chemotherapy

The problem was I was in a clinical trial and so there was a delay for those cells. Then my lymphoma started growing. They did something called bridge chemotherapy.

I had an off-label treatment for lymphoma called Ibrutinib, which had shown effectiveness in diffuse large B-cell ABC subtype. Turned out, that worked beautifully. It put me in remission. These are chemo pills you take. It was so much easier than anything I’d done.

Waiting for the T cells

We waited for my cells to be ready. There was a little glitch because I made too many cells. The FDA didn’t like that I had too many cells, so they wouldn’t filter them off. I had to get FDA-approved just to have my own cells back. I had my cells out in May and then I was scheduled to have them infused in September of 2016.

Cytokine release syndrome

Once these T cells are altered, they’re cultured in the lab, and then they’re infused in the patient. The T cells go around, bind to the tumor, and blow all these little tumor balls up but that actually can cause a response by your immune system called cytokine release syndrome.

It’s similar to some of the people’s reactions to COVID. We’ve actually seen people with COVID pneumonia that get these horrible infiltrates in their lungs. It’s more of a reaction to the virus and the cytokine reaction as opposed to the infection. It’s very similar. They were trying some of the same treatments for COVID that they use in cytokine release syndrome for CAR T.

With CAR T cytokine release syndrome, some people get it, some people don’t. [For] most people, it’s very mild and transitory. It’s not permanent. It just is an immediate reaction and then it goes away.

My T cells were infused in September of 2016. The infusion lasted 10 minutes. I had 600 million cells in this big bag. Everyone clapped when they were infused and then they waited. What’s going to happen?

Within 24 hours, I started getting a fever. I was told if I was going to [have a] fever [to] go back to the hospital. It got up to over 104 [degrees]. I had low blood pressure, shaking chills, [and] felt terrible for three days.

Because it was a trial, they didn’t give me anything for it. I only got Tylenol. They give you things for this now that I didn’t get, but it went away.

I would have six months to live, without therapy. Here I am, almost six years out. It’s amazing.

Remission

By the time I was discharged from the hospital, my lymph nodes had gone. They’d melted like ice cubes. They were completely gone. I was in remission — clinically, not with a PET scan — within one week of getting CAR T. Just amazing.

I felt fine. I was just tired [and] a little nauseous. The fatigue was there but nothing like [a] bone marrow transplant. It was nothing. I’m enjoying the gym two weeks into it. It was great. I went back to work four weeks after CAR T-cell therapy. I only went part-time at first and then I gradually went up to full-time.

Here I am, almost six years out. It’s amazing.

I would have six months to live. Without therapy, on average, you have six months to live. Now, if I’d taken some steroids or had an allogeneic, I might have had another chance to live. But the problem with [the] allogeneic transplant, again, I had no match, which means I’m not going to do well. Now some people do okay, but without a match, people don’t do as well.

When you get to the point where you’re getting CAR T, you don’t really have a whole lot of other choices.

Post-CAR T-cell therapy

When you compare it to how sick I was after [the] stem cell transplant, I just couldn’t eat for so long. I felt terrible. I felt fine after CAR T.

One thing after CAR T is I’m immunodeficient because the T cells destroy all my B cells — the cancer B cells and my normal B cells.

I’ve had to be very careful about infections like MRSA or CRE. All of these antibiotic-resistant organisms are the ones I stay away from. I had to change my practice because I was doing a lot of hospital care. Now I’m all doing outpatient just to be careful.

CAR T works in lymphoma about 40% of the time but not 100% of the time. They’re working on improving it. [For] those people who fail CAR T, a lot of them would go on to an allogeneic transplant. Hopefully, not me now.

I have been given a second chance at life and it’s an unusual experience for everyone. I cherish it and I enjoy every minute. I’m very, very grateful for medical research and all the doctors, caregivers, my friends, and everyone who’s really helped us along with this. It’s just really special.

It’s interesting because CAR T’s a new therapy. Everyone’s very nervous about cytokine release syndrome [and] all these side effects, but they don’t really think about the side effects [of a] stem cell transplant, which are much worse.

Stem cell transplant, [an] allogeneic transplant, has a 10 to 20% mortality rate just from having the transplant. CAR T almost has a 0% mortality rate. A lot of people can get neurotoxicity with this where you’re confused for days. [The] majority of people get totally better. I really don’t know of any other ones that haven’t gotten better.

When you get to the point where you’re getting CAR T, you don’t really have a whole lot of other choices. Right now, CAR T is being used as a second-line therapy ahead of stem cell transplant, which I think is awesome. Some people are very nervous about that but they need to really research what the stem cell transplant side effects are as well as CAR T because it’s a new treatment. Everyone gets very nervous about that. I get it.

Words of advice

Looking for clinical trials

I still think the [ClinicalTrials.gov] website is pretty straightforward because you put your diagnosis in and you just have to look at trial after trial.

If you have blood cancer, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society is very helpful. They have Lymphoma Research Foundation as nurse navigators. Multiple myeloma, there’s something called SparkCures, I believe.

Right now, they have CAR T-cell trials for solid tumors, for immunologic deficiencies, and some of those organizations have their own nurse navigators or people who can help with advice. I just think you have to be your own advocate and start calling everywhere.

Bone marrow registry

Everyone should get on the bone marrow registry, that’s my big plug because there [are] a lot of us out there that are multiethnic, so we need a lot of people on the registry. I just didn’t really have a chance.

Mental health support

Any time you have a life-threatening situation, whether it’s cancer or any other disease, you need to use any ancillary help you can. I’m a big believer in integrative medicine as well as standard Western medicine.

[With] integrative medicine, there’s a role for psychotherapy. It’s really important [for] anybody who’s gone through a life-threatening event. People in the military who’ve almost died, a lot of them get PTSD. I think all cancer patients get a form of PTSD. It’s important for a lot of patients to talk to therapists. I’m all for that. I certainly did that after my bone marrow transplant. It was very traumatic for a while, but luckily, it was helpful.

I also recommend talking to nutritionists. I’m against any type of major extreme diet. They’re not necessarily helpful for you. It’s amazing when you talk to nutritionists [about] how you can improve the way you feel.

I’m also a big believer in exercise. A lot of that you can do on your own. Just walking and being outside is really important and it’s amazing what the health benefits of that are. I think it’s really true. Eat right and exercise. There is a lot of role for that. It’s simple but true.

Role as a physician-patient

My biggest contribution to medicine is probably not as a physician but as a patient and that’s okay. I’m good with that.

I’m so happy to be able to help others. This is what I’ve done my whole life. I wanted to become a doctor since I was five. I’ve spent my life as a physician trying to help patients and here I am able to help them in a different kind of way. I think it’s been a lot more impactful and it’s going to affect the way that cancer is treated from now on.

This is the future. The immunotherapies are the future of cancer therapy and, as it turns out, even some therapies for autoimmune diseases. It’s a whole new world out there and I’m very optimistic.

Before I had cancer, I was pretty empathetic. Now, I am even more empathetic. My practice right now does involve a lot of [mammographies] where I see patients every day. I diagnose breast cancer every day. I see patients who’ve had breast cancer.

I see patients who are in the middle of chemotherapy and I can really chat with them. In some cases, I give them advice about going to tertiary care centers [or] integrative cancer therapy centers. They may not have heard of that. They may have just been moved here. I’m always happy to offer that because it is a service the hospital offers.

I also just hold their hand and talk to them about losing their hair, having it grow back in, how weird that is, and can joke about some things. It’s nice. We have a special bond, some of the cancer patients and myself. I think it’s great for them and it certainly helps me. It’s a win-win situation.

Inspired by Robyn's story?

Share your story, too!

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Stories

Don S., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Symptoms: Weight loss, fatigue, enlarged lymph nodes

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy (epcoritamab)

Leanne T., Follicular Lymphoma Transformed to DLBCL, Stage 3B

Symptoms: Fatigue, persistent cough

Treatment: R-CHOP chemotherapy, 6 rounds

Robyn S., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 2E

Symptoms: Enlarged lymph nodes

Treatments: Chemotherapy: R-CHOP, R-ICE, intrathecal, BEAM; autologous stem cell transplant, head and neck radiation, CAR T-cell therapy

Stephanie Chuang

Stephanie Chuang, founder of The Patient Story, celebrates five years of being cancer-free. She shares a very personal video diary with the top lessons she learned since the Non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis.