Jim’s Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Story

Interviewed by: Alexis Moberger

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

Jim began experiencing alarming symptoms one day when his head and neck swelled up suddenly due to backed-up blood flow, causing his face to turn purplish and his neck veins to bulge. After the swelling subsided, he was rushed to the ER at the University of Pennsylvania, where initial tests revealed a severe narrowing in his superior vena cava.

Doctors were baffled by his condition. Over four days of hospitalization, various specialists attempted to diagnose the cause of the obstruction, but no clear answer emerged. Even though lymphoma was mentioned early on, it was dismissed because lymphoma typically doesn’t present in veins. The situation grew more critical as the narrowing worsened, leading to a second hospitalization, but still, no one could identify the cause.

As hope dwindled, a heart and lung transplant surgeon proposed an innovative surgery: removing the entire superior vena cava and replacing it with a graft made from pig intestine. Jim underwent the surgery, which was more complicated than expected due to the extent of the tumor. The pathology report later revealed that the obstruction was caused by diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Following the surgery, Jim faced additional challenges as his surgical site began to narrow again due to natural healing and scarring. The doctors debated whether to insert a stent to keep the vein open, but Jim opted to endure the discomfort, trusting that his body would heal over time and develop new collateral veins. After weeks of uncertainty, he started chemotherapy to address the lymphoma.

- Name: Jim Z.

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 41

- Diagnosis:

- Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

- Symptoms:

- Sudden and severe head and neck swelling

- Purplish facial discoloration

- Bulging neck veins

- Treatments:

- Surgery: resection and reconstruction of the superior vena cava

- Chemotherapy

Thank you to Genmab for supporting our patient education program! The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make treatment decisions.

Suddenly, my head and neck began to swell up… if this was going to continue at the rate it was going, I wasn’t going to be around for much longer.

Introduction

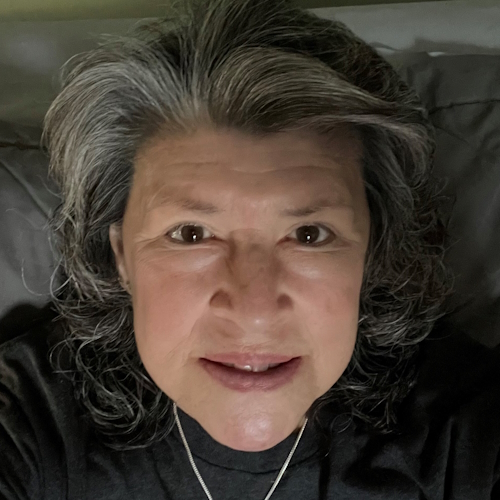

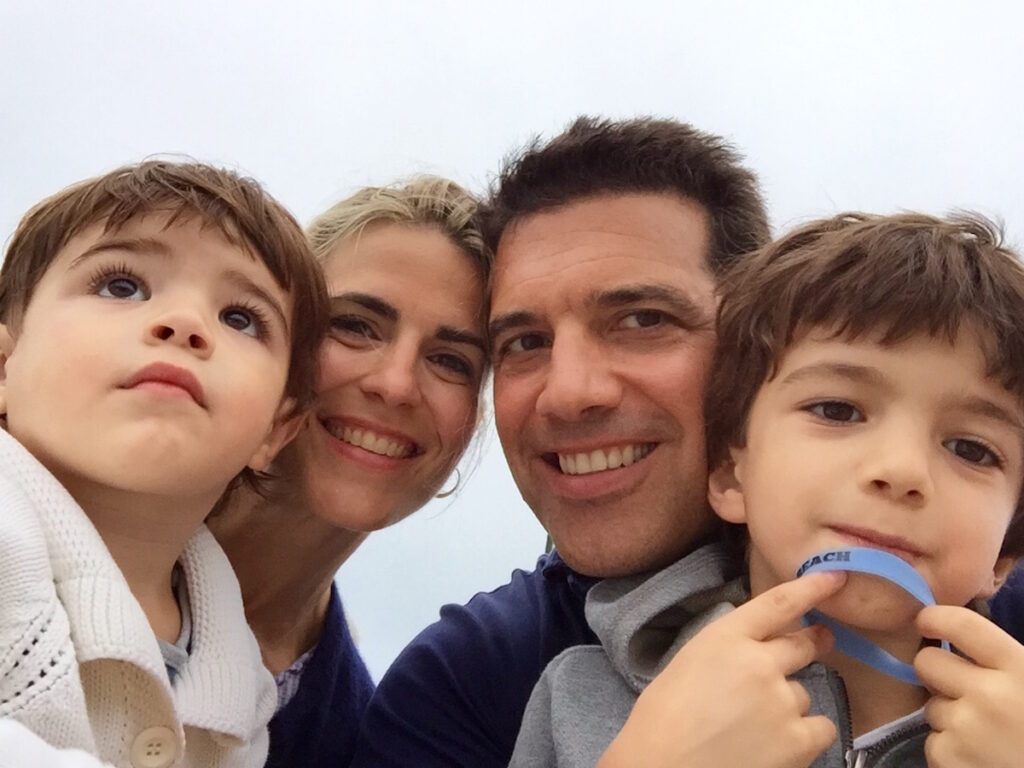

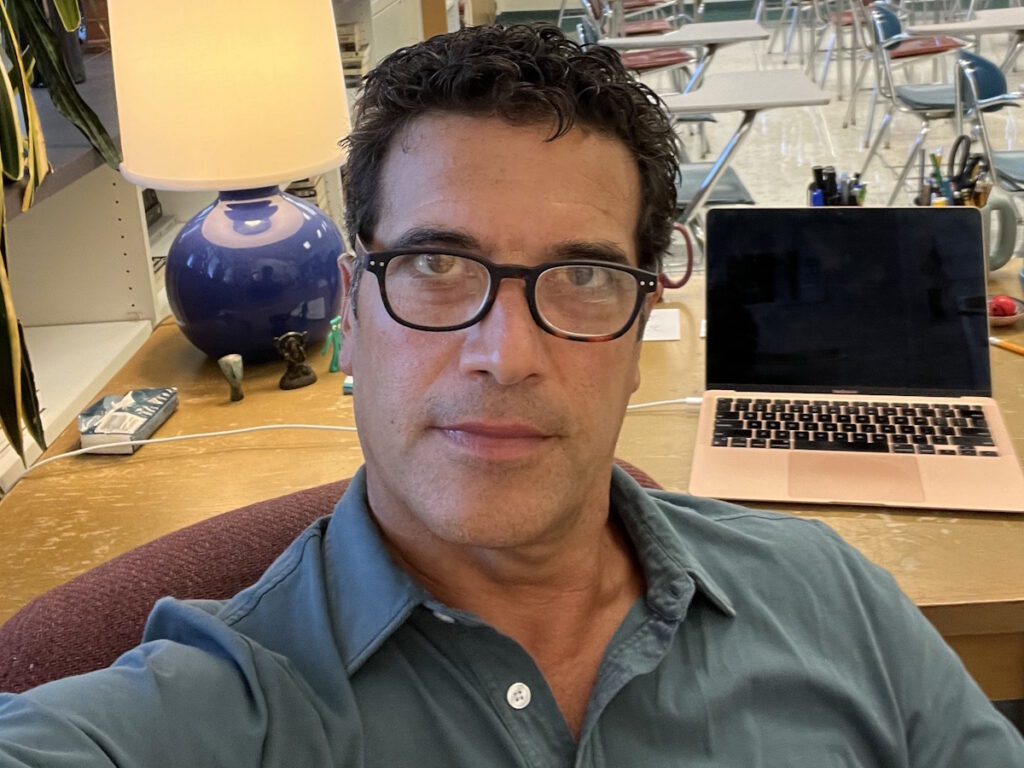

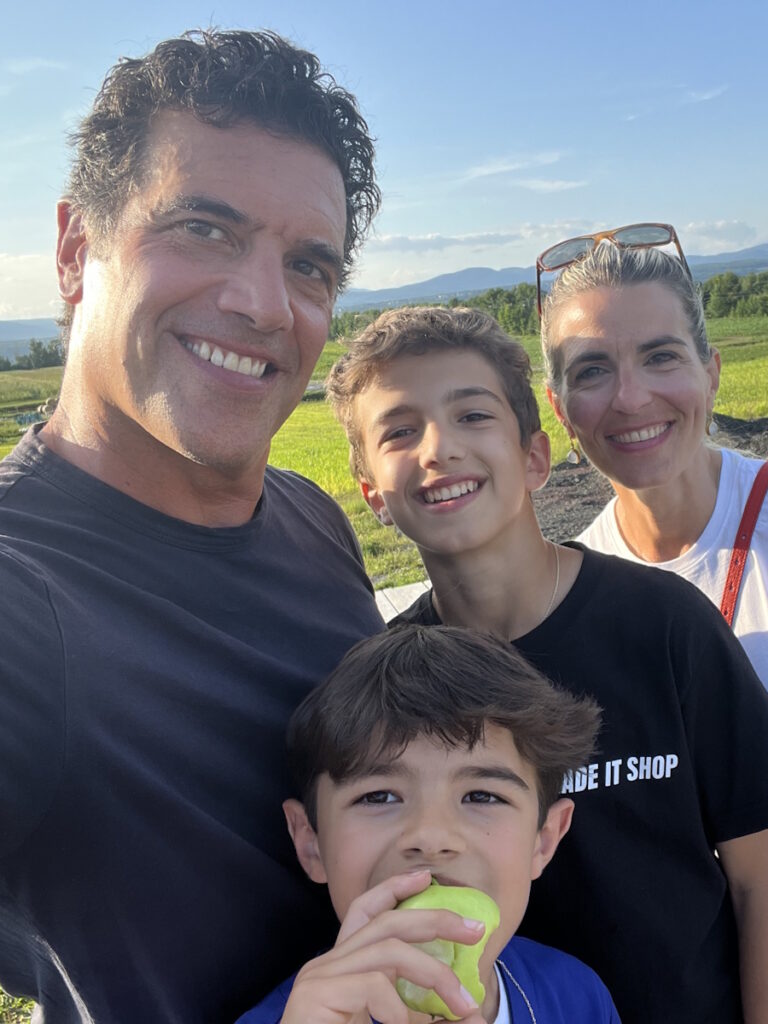

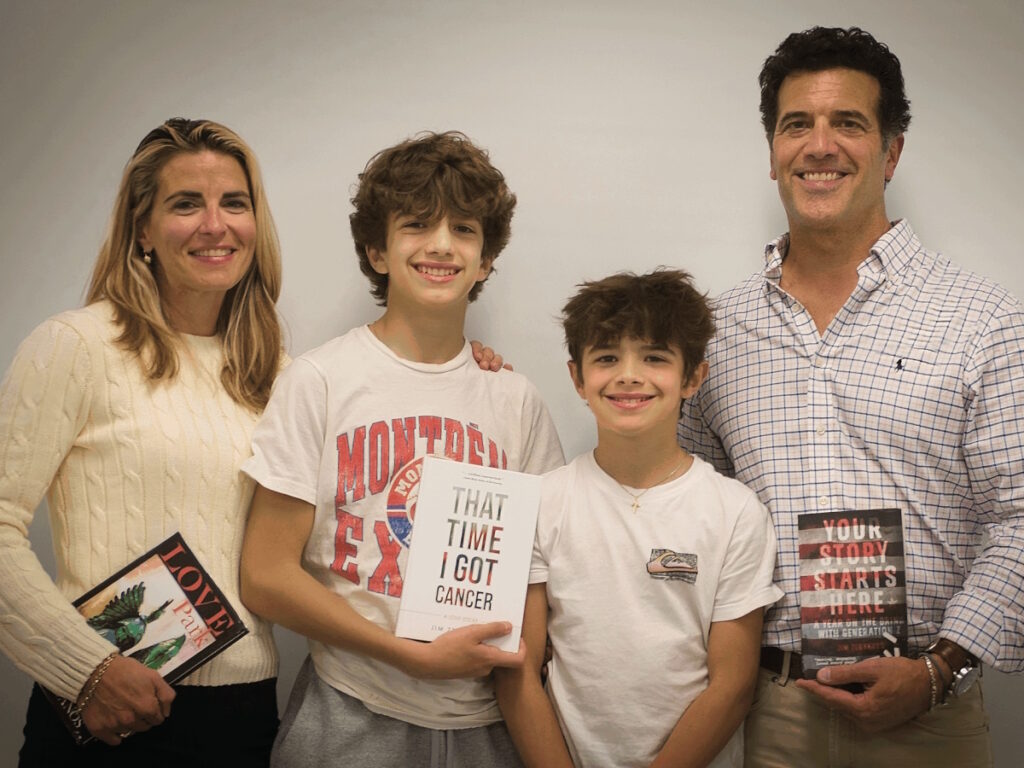

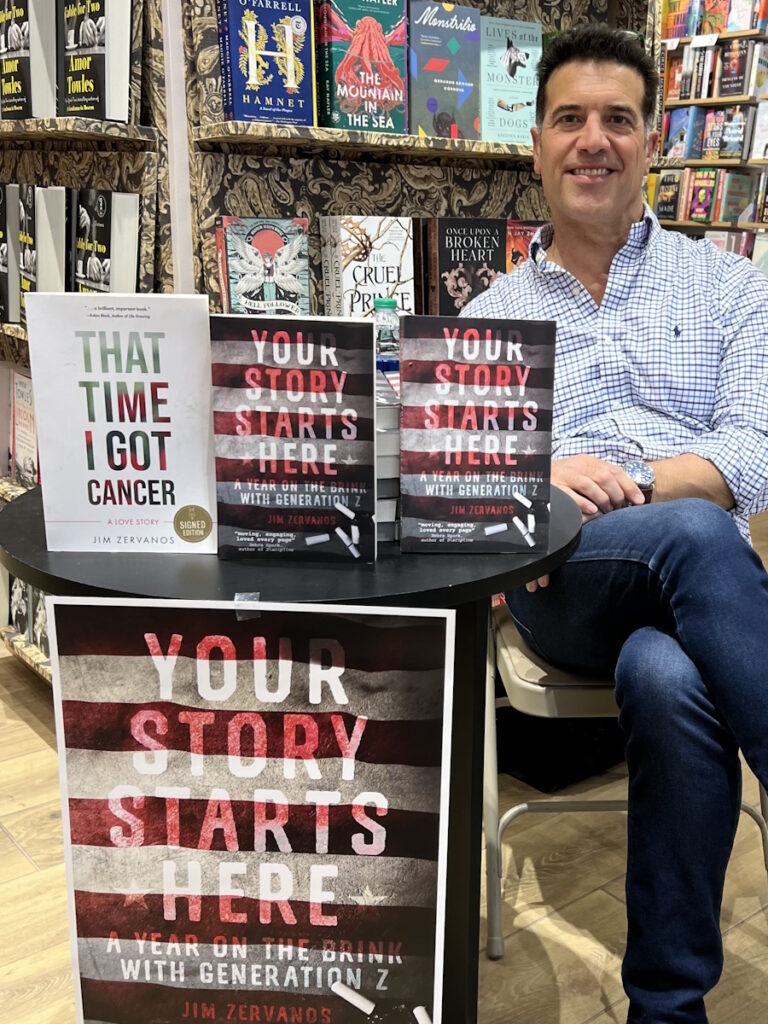

My wife Vanna and I are parents to two terrific boys, Nikitas and Victor. We live in the suburbs of Philadelphia, where I also teach. I’m a high school English teacher and a writer. I also paint and coach Little League.

How the Symptoms Started

I was getting ready to go to a Phillies game when, suddenly, my head and neck began to swell up with backed-up blood flow. It was so alarming. I looked in the mirror and saw my head puffing up like a balloon filling up with water.

I called out to my wife, who came rushing and immediately saw me. My father is a doctor, so I called him. It was pointless to call 911 because if this was going to continue at the rate it was going, I wasn’t going to be around for much longer.

My wife and I stared at myself in the mirror while my father very amazingly and gently told me to breathe. This went on for two or three minutes. You can imagine the swelling and purplish appearance of my face and neck with neck veins bulging

As dramatically as it started, it stopped. My blood flow reached equilibrium and I began to feel normal. I even joked that we were going to go off to the Phillies game after that. My father said no and that I was going to the emergency room.

She pointed to the narrowing and said, ‘We don’t know what this is, but it could be fatal.’

Going to the Emergency Room

When I went to the ER, I appeared normal, but when I described what happened to me, I could tell from their reaction that something serious was going on. In a matter of hours, I had blood draws and X-rays taken. I waited in a room very patiently and watched the entire Phillies game on the TV.

Around midnight, I went to the front desk and asked the attending doctor if she was as surprised as I was that we still hadn’t heard any results. She looked at me with tender eyes and said she would see me in a minute.

She came into my room, sat next to me, held a pretty fuzzy X-ray image up, and pointed to what looked like an hourglass. She pointed to the narrowing and said, “We don’t know what this is, but it could be fatal.” Those were the first words that I heard from a doctor about whatever was going on inside of me.

As shocking as that sounds, it wasn’t entirely surprising because of what had happened to me. The force of the earlier incident of whatever seemed to be obstructing my blood flow was stunning. I understood that it was game on.

A couple of hours later, I was getting an MRI. I had never gotten an MRI before and it’s not something anyone feels comfortable doing. As claustrophobic as I am, it didn’t even occur to me because it was my first time and I didn’t know any better, so I just lay there in that tube. I was in survival mode and if this is what’s necessary to get to the bottom of things, I can do this. I went back to my father’s advice to breathe and tried to stay calm.

The irony is that every department had somebody come to see me to speculate on what might be ailing me—every department except oncology.

What the Doctors Could See From the Scans

There was some blockage or obstruction in my superior vena cava, the main vein that descends to the heart and the last and most crucial vessel that brings blood back to the heart. In retrospect, that would explain why all of a sudden, I had backed up blood in my head and neck. At some point, the blood managed to get through the superior vena cava, so my blood flow returned to normal.

I was admitted to the hospital for four days. The cardiovascular surgeon was appointed as the head of my team. A young attending doctor was trying to round up the best people. At one point, he told me, “You’re the talk of the hospital. Everybody wants to be the guy who figures out what’s going on in your chest, but we don’t know.”

The irony is that every department had somebody come to see me to speculate on what might be ailing me—every department except oncology. Early on, the theory was cancer or lymphoma, but it does not present this way. It’s rarely in the chest and never in veins and this was clearly in a vein. Six months later, my oncologist told me, “We do find lymphoma in veins occasionally, although rarely and only in an autopsy,” so this was not in anybody’s working diagnosis and it was disqualified almost from the get-go.

The one guy who might be able to do something would be the interventional radiologist to do a biopsy, but he was determined to avoid doing that because he would have to put a needle into my superior vena cava. Not only was there some obstruction in there, but it appeared to be in the wall of the vein. He explained how he would have to pierce a needle through the wall of the vein and somehow extract a piece of whatever was in there. He said, “I’m not doing it. It would be catastrophic and I don’t want to kill you.”

We saw a narrowing so severe that it was hard to imagine how any blood was getting through to my heart.

After four days, a cardiac surgeon proposed to open up my chest completely to get to the vein, but we were still left with a catch-22. The interventional radiologist said, “Even if I had your superior vena cava in the palm of my hand and my best needle in my other, I would not dare try to get a piece out of the wall of your vein to do a biopsy.” We were stuck. I wasn’t having dramatic inflamed symptoms but I was still uncomfortable.

On day four, a cardiovascular surgeon came in and said, “It may be some idiopathic thing that we can’t explain. There are medical mysteries. We’re going to send you home without a diagnosis. If you have another flare-up, if you continue to have worsening symptoms, we’ll have you come back in a month and we’ll do more imaging.”

I left and I was not confident because you feel the sensations in your own body. I was hopeful, but my gut said something was happening inside of me.

Symptoms Returned After Leaving the Hospital

Over the next few days, it got worse. It was backing up. Again, with the benefit of hindsight, what was happening was the tumor was growing and the narrowing was becoming more severe. The blood flow to my heart was decreasing by the day.

I packed my bag. My parents happened to be at our townhouse that afternoon. I showed up in the doorway and said we had to go back. We went back to the hospital and I was readmitted.

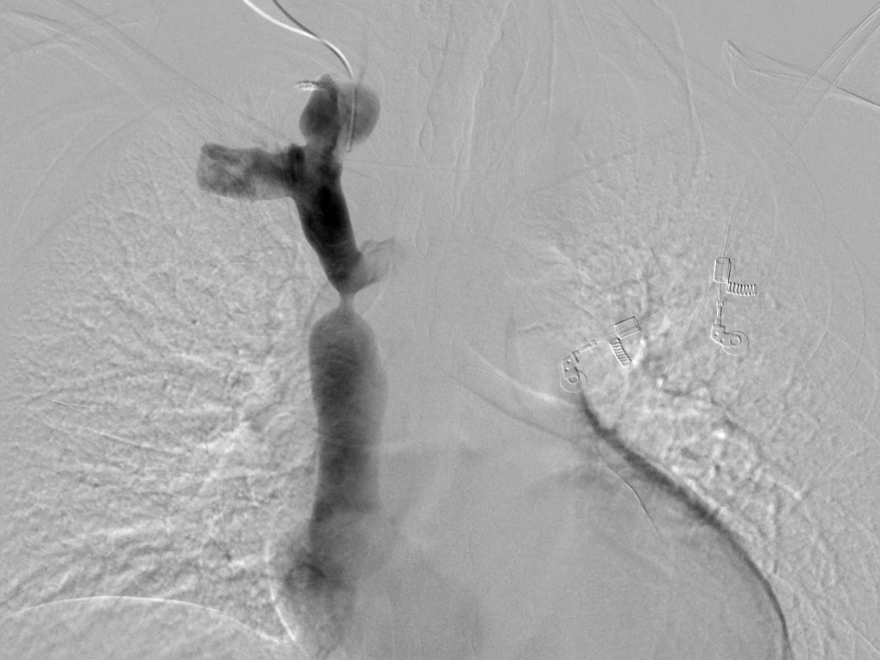

The cardiovascular surgeon and the interventional radiologist decided that I was going to get a venogram, where they put the dye into the bloodstream to get a more vivid image. We saw a narrowing so severe that it was hard to imagine how any blood was getting through to my heart.

It was supposed to be 15 mm at its maximum and it was narrowed down to about 3 mm — that’s how much blood flow was going to my heart.

Three or four doctors were looking at the gigantic triptych of images that showed my superior vena cava and the narrowing that came nearly closed and then opened again. They shook their heads and said, “We don’t know what this is.” The cardiovascular surgeon came in and somberly said, “I’m sorry. We’ve tried to do everything and there’s nothing left that we can do.” We all knew what that meant.

My father, who’s a doctor and is always inquisitive and never at a loss for hope, was quiet. That gives you some indication of all the conversations, research, and investigations that had gone on for the last 10 days had come to this moment and we accepted it.

I hugged my wife. My parents went over to the window and I went over and hugged them. Very strangely, I was more equipped to handle the news than anybody. I had been living with that first thought on the night I went to the ER and was told this could be fatal. We didn’t know what this was, so I had been preparing for this possibility.

When I hugged my dad, he said, “I’m sorry, son,” and I said, “I’m sorry, dad,” and the next thing that he said was, “Tomorrow, more research.” That was a profoundly hopeful, illogical moment, but it shows you the balance of this man of science who, even after all of that, was still determined that there might be something, but he was also my dad, going through this with me and all of us.

Not Giving Up Hope

A couple of hours passed and there was a new young attending doctor on call that day. I said to her in passing, “I would love to sit with the head of radiology and be able to look at all the images from the first day to the most recent venogram.” A lot of imaging had been done and I was trying to understand the anatomy of the superior vena cava and the brachiocephalic veins that go up into the jugular veins. I learned all this anatomy and I wanted to understand it better.

I was looking at these spectacular 3D images. It was supposed to be 15 mm at its maximum and it was narrowed down to about 3 mm — that’s how much blood flow was going to my heart.

The doctors looked at each other and shook their heads. The interventional radiologist was convinced more than ever that he wasn’t going to stick a needle in there. They both said, “It’s got to come out since we can’t get to it.” But nobody knew what the surgical strategy would be.

‘I’ve got an idea. I propose that I open you up and take out your entire superior vena cava and replace it with a graft.’

Six hours or so later, a man I had never seen before walked in. He’s a heart and lung transplant surgeon at UPenn. He said, “I know you don’t need a heart or lung transplant, but I’ve got an idea. I propose that I open you up and take out your entire superior vena cava and replace it with a graft that I’m going to craft out of this material that I’ve been using to patch hearts and lungs. I’ll make a vein for you and attach it at both ends. I think I can do it.”

My wife and I were alone with him, stunned and giddy, happy and amazed, and slightly skeptical. My wife Vanna ran to the hallway, grabbed my parents, brought them back in, and said, “Repeat what you just said.”

We listened to him describe the surgery that he had planned. He had been using an organic material made out of pig intestine. He’d been using it to patch hearts and lungs, but he thought he could make a cylinder out of it and make a vein that would replace my superior vena cava. He said he would do this. I said, “So there’s still hope?” And he said, “There’s always hope.”

Surgery Day

I went into surgery feeling good and confident. I woke up on the other side and it worked. When the surgeon came to visit, he said, “It ended up being a little more complicated than we were anticipating. It wasn’t just a tube after all.” He described it as black muck that he’d never seen anything like before. It went up into the brachiocephalic vein. He took more of that material and had to make a Y shape, did the surgery, and attached my superior vena cava to the brachiocephalic vein, which is even narrower. A brilliant surgery to say the least.

They sent the whole thing off to pathology to find out what it was all along. Five days later, while I was still in the hospital recovering, a young man from hematology came to see me and said, “You’ve got diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.” Everybody’s mind was blown because it defied all expectations.

We would give the graft a month to heal and then start chemo. Fortunately, I was able to get the chemo through a vein in my arm.

Doctors Couldn’t Believe It Was Cancer

My oncologist, one of the great lymphoma doctors, said he had never seen anything like it. In a month, I started chemotherapy and that’s when I met my oncologist.

That was the first time I ever heard about cancer or lymphoma. But I had a graft in my chest that needed three months to heal. That was the plan.

My surgeon said, “I don’t know what chemotherapy is going to do to Jim’s graft made out of pig intestine and we’re certainly not going to stick a port in his chest into his superior vena cava. Hopefully, the chemo will go well into a vein in his arm.”

On the other hand, my oncologist, said, “We’re not waiting three months for this graft to heal. We called the company that makes the graft and asked how chemotherapy interacts with the material. They had no idea.

The doctors compromised and agreed that we would give the graft a month to heal and then start chemo. Fortunately, I was able to get the chemo through a vein in my arm and we went from there.

Despite everybody’s certainty that lymphoma doesn’t present that way, a lymphoma tumor was growing inside the wall of the vein of my superior vena cava.

The obstruction that was originally in my superior vena cava was a lymphoma tumor. Despite everybody’s certainty that lymphoma doesn’t present that way, a lymphoma tumor was growing inside the wall of the vein of my superior vena cava.

I tolerated some great discomfort but in time, I trusted that the body would do its magic and heal itself, and other tributaries would form as these guys described to me. Presumably, that’s what happened because I’ve had scans since and I still have this dramatic narrowing. Even though you can’t see in any of these images that other collateral veins have formed, everybody thinks that the only scientific explanation is that’s what happened.

I am sure I am one of the very rare cases where the cancer and the chemotherapy were always secondary to the healing of the surgery.

Cancer Responded Well to Chemotherapy

While it was an aggressive cancer lymphoma, it responded well to chemotherapy. These were all very promising signs and that gave me optimism. As long as I could withstand the symptoms, my body tolerated the chemotherapy, and the healing could continue, we’d get to the other side of this and hopefully, the chemo cocktail would do its work.

I maybe had six rounds of chemo every three weeks. I had one reasonably tolerable week and one week of debilitating nausea. But all the while, I was also recovering from surgery.

By the sixth round, I was in remission. There was no lymphoma showing up on the PET scans.

When we got to the fourth round or so, I got tested and it appeared that there was no growth. Eventually, by the sixth round, I was in remission. There was no lymphoma showing up on the PET scans.

At the time, I couldn’t wait to get back to normal. There was only one marking period left in the year. I teach English and writing to seniors and wanted to be in this atmosphere of dynamic conversation, kids, and vitality.

When I came back at the beginning of April, my colleagues were thinking, “Are you crazy? Take the year off at this point and see you in September.” But I couldn’t have been happier to be back. My hair was growing back. I was still bald, but it felt great to be back.

How I Survived

As a patient, I was the unluckiest guy on the planet because nobody could detect what I had. I reached a low point where doctors told me there was nothing else that could be done. Then the surgeon said the magic words: there’s always hope.

I take that with me into everything that I do. Even after all seems lost, you don’t know what you don’t know. You’ve got to stay awake for every moment of your life because if you’re full of anxiety and despair, you might not see an opportunity that could point you down a positive path to good health.

I was fortunate to grow up with a doctor as a father and live in a city with institutions, like the University of Pennsylvania. I had faith in the doctors and the institution, and I don’t take any of that for granted. It’s easy for me to tell others to have faith and hope because I was born with that.

Keep the faith. Stay hopeful. Be your best self-advocate.

What came from my experience as the son of a doctor was confidence in having conversations with my doctors, the expectation that they were listening to me, and that they wanted to hear my story because that’s the kind of doctor my dad was.

My dad was a family doctor and he made sure to make eye contact to hear the patient’s story and to be there emotionally not just clinically. Again, it’s easy for me to say to a patient who might be going through these things who didn’t have the good fortune that I had with all these other lucky things that I had going for me.

Words of Advice

Keep the faith. Stay hopeful. Be your best self-advocate because you never know and the doctors don’t always know either. They need to hear your story.

Special thanks again to Genmab for its support of our independent patient education content. The Patient Story retains full editorial control.

Inspired by Jim's story?

Share your story, too!

More DLBCL Stories

Lena V., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 1

Symptom: Blood in urine

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy (R-CHOP), radiation

Cindy M., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Itchy skin on the palms and soles of feet; yellow skin and eyes

Treatment: Chemotherapy (R-CHOP)

Tony W., Relapsed T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma (T/HRBCL)

Symptoms: A lot of effort needed cycling, body wasn’t responding the same; leg swelling

Treatments: R-CHOP chemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapy