Kerry Rogers, MD

On Latest CLL Research & Treatments

Kerry Rogers, MD shares the latest news and opinions on treatment options for CLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia) patients.

Lending her vast expertise and research experience as an assistant professor in the Division of Hematology at The Ohio State University (OSUCCC – James), specializing in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and hairy cell leukemia (HCL), Dr. Rogers sheds light on participating in clinical trials and the community’s efforts to move the mark in the standard of care.

Explore below for Dr. Rogers’ insights on everything from the latest in CLL treatment, decision making throughout treatment, importance, and prospects of clinical trials. Full written version below the video.

- Introduction: Dr. Kerry Rogers

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

- Standard CLL Treatment

- Targeted Therapy

- Choosing between Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy

- How long have the targeted agents been in use

- Continuous novel agent therapy vs. time-limited

- Treatment for relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL

- Targeted Therapy Side Effects

- Clinical Trials

- Up and Coming New Treatments

- Treatments for Hairy Cell Leukemia (HCL)

- More Medical Expert interviews

Introduction: Dr. Kerry Rogers

I currently live in Columbus, Ohio, and I’m from the Midwest, but I grew up in the Chicago area.

I have a guinea pig, and I like college football. That’s huge at the Ohio State University, but I did my residency at the University of Michigan.

Don’t tell anyone, but I went to Northwestern for an undergrad, so that’s really my football team. That’s just a bit of me.

I work at The James (OSUCCC), and I enjoy taking care of people with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and hairy cell leukemia (HCL).

My major interest academically is on improving targeted agents for the treatment of both these diseases.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

What is CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia or CLL is a blood cancer. It’s a cancer of cells called B lymphocytes. Don’t ask me why they’re called B lymphocytes! Those are white blood cells or immune system cells that have turned into cancer cells at some point over their lifespans.

They can go anywhere in the body that the blood goes to—you can find them in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, liver, and spleen, and in the blood, because it’s leukemia.

You can make a CLL diagnosis when there’s a certain number of these leukemic white blood cells or CLL cells in the blood. You can diagnose it with a blood test, and the most common way these days that people come to be diagnosed with CLL is when their white blood count appears too high and then goes through blood tests.

Many people diagnosed have no symptoms whatsoever and are sometimes somewhat confused about going to the cancer hospital to meet with me.

When thinking about CLL, it’s also important to realize that this is the most prevalent adult leukemia, meaning more adults live with CLL than any other type of leukemia.

People with CLL can expect to live a very long time, including their natural lifespan, and not everyone needs treatment. Because of that, it’s imperative to think about how well people are going to live with their CLL.

Categories and Stages of CLL

Unlike solid tumors like breast cancer or lung cancer, where the staging is based on how far it’s spread in the body, and if it’s left the site where it developed, which could mean the patient is in big trouble, we stage these blood cancers differently. Since they go over where the blood goes, which is everywhere, we can’t use the same basis.

In the United States, the most common staging for CLL is called Rai Staging. It was developed by Dr. Rai, a very nice man if you ever get the chance to meet him.

Rai Staging

- Stage 0: CLL cells are in the blood

- Stage 1: CLL cells are in large lymph nodes

- Stage 2: An enlarged liver or spleen from CLL

- Stages3 & 4: CLL cells are on the bone marrow that has caused people to have low hemoglobin, be anemic, or have a low platelet count from the CLL

How is CLL staged?

It’s staged simply by physical exam and looking at blood counts, and many people don’t need a bone marrow biopsy for staging. Some people need it to know why people’s blood counts are low, but it’s not always necessary.

The other part was the main forms of CLL and if there’s a slow-growing or a fast-growing type.

Everybody’s a little bit different. You’ll see some people diagnosed with CLL, and they’ve had it longer than I’ve been a doctor, and they’re doing fine with it. Their white count is the same as it has been for the last couple of decades.

But there are people whose CLL isn’t moving very fast at all. Then, some were diagnosed 18 months ago, and their white count has gone from 15 to 200 over that time.

Tests for CLL

The course of the disease can be quite different in many cases, and there are some tests that we can do to help better estimate if it’s going to be a slower or faster-growing CLL.

IgHV mutational status

One of those tests is called IgHV mutational status, or immunoglobulin heavy chain gene mutational status, where unmutated usually means a faster-growing, higher risk CLL.

I’d like to think of mutated as a special, low-risk slow-growing CLL, and that’s mutating your immunoglobulin as a normal process in B cells. This just says whether or not the CLL cells did that before they turned into leukemia cells.

FISH test for CLL

Some other tests that can help include FISH panel testing, which is just a fancy way to look at chromosomes in the CLL cells, not like the ones you pass onto your kid.

Things like deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17 or deletion of 17p can mean that we’d expect the CLL to be faster-growing, and deletion of 13q, which is part of the 13th chromosome, predicts slow-growing.

We can use a combination of these factors to guess how someone’s CLL will do.

Of course, sometimes we’re surprised. Sometimes, it looks like it will be slow-growing and it’s not, or people with some high-risk features really have an extended course but their CLL isn’t causing them any issues.

CLL in layman’s terms

One thing that really helps people that’s not necessarily fancy is knowing how to look at your own blood counts.

People get these complete blood counts all the time, and you’ll see your white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin, platelets, and then below that, you’ll see a differential that tells you what type of white blood cells those are.

You always want to look at the lymphocyte count, because the CLL cells are counted under lymphocytes.

The other testing is something you do just on the leukemia cells.

It’s always very important to ask if this testing is done and what the results are so that you can know more about your CLL.

It helps you predict how much trouble you might have from the CLL in the future, the time before needing treatment, help in selecting a better course of treatment, how many treatments you might need in your lifespan, or if, at some point, a clinical trial might be appropriate for you.

The major ones are the IgHV and CLL FISH panel, which stands for fluorescence in situ hybridization. It is a chromosome analysis where they look at all the chromosomes because people with three or more changes in their chromosomes actually predict a higher risk of CLL.

They can expect to have more treatment and more difficulty with it in their lifetime. People with normal karyotype, like normal chromosomes, actually expect to have less difficulty.

Standard CLL Treatment

Shifting Away from Chemotherapy

First, it’s important to realize that the median age that people are diagnosed with CLL is in the mid-60s or almost 70. There’s a lot of older people who might have other health conditions.

It’s always important to think about what other health conditions someone has when planning treatment.

It has been a goal in the field of CLL medicine for a long time to make sure that some treatments are appropriate even for older people in their 80’s or even 90’s with other health conditions.

But here, I’m going to talk about more of the chemotherapy for younger, fit people because I think it’ll be easier to understand in that setting.

We’ve always had some chemotherapies that could lower the white count or improve symptoms. But the mark was moved on how long people are living with CLL or survival by combinations of chemotherapies with an antibody medication called rituximab.

Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab (FCR)

The last several decades before my time working in CLL were spent developing a regimen called FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab). Rituximab is the antibody and the other two are chemotherapies.

Bendamustine and rituximab

There’s a similar regimen you can use in people who might be slightly less able to tolerate chemotherapy called bendamustine and rituximab. These are highly effective chemotherapies that could be given to most reasonably healthy people and can control the CLL for years.

Targeted Therapy

ibrutinib and venetoclax

It’s important to know that as a first treatment, our new targeted agents, like ibrutinib and venetoclax-based treatments, were compared to these chemotherapies and had longer progression-free survival. This is a measure of how long people are alive without their leukemia returning.

We have found that these targeted agents were actually better than these chemotherapies.

That means people lived longer without their CLL coming back after they took the non-chemotherapy targeted agents. Also, they have a different group of side effects that are generally better than chemotherapy.

»MORE: Read more about ibrutinib and other patient experiences

Choosing between Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy

Some people choose to get chemotherapy because it’s different from these targeted agents, or they might have a health condition that makes the targeted agents inappropriate.

These days, the vast majority of CLL patients should be receiving treatment with a targeted agent and not with chemotherapy.

It’s very uncommon that you’d have to use chemotherapy to treat CLL. The one exception to that is young fit patients. IgHV mutated people and don’t have a high-risk feature such as deletion 17p can have 10 years or more of being alive with no detectable leukemia after getting FCR.

A group of younger people fit for chemotherapy treatment are those mutated and don’t have deletion 17p, called a TP53 mutation. But they might choose to get FCR because it might actually cure them.

I don’t know what else to call 10 years of being alive without detectable leukemia. We don’t usually say CLL is curable, but this is the one case where it might be.

However, there’s a lot of risks to doing FCR, like getting a different type of leukemia called acute myeloid leukemia (AML). That happens down the road due to bone marrow damage from FCR.

That is the one case where it could be very important to offer chemotherapy, especially to young healthy people that might want to do a treatment course of about six months and then potentially never need treatment again in their lifespan.

It’s not a guarantee that they’ll never have leukemia come back, but that is the one case where it’s important to think about it. But for the vast majority of other people, targeted agents are safer and more effective.

How long have the targeted agents been in use

The BTK inhibitors were developed in the last decade, and venetoclax shortly on the heels of that. When things are through phase III studies, that’s when they start being prescribed more commonly.

We—the academic centers—get to use all these drugs and people that come see us here might benefit from taking them as a participant in a clinical trial.

I’ve seen many people who did really well doing a research study to get a newer drug that later became approved. This becomes more widely available and used by general practice, hematologists, oncologists after phase III studies.

Continuous novel agent therapy vs. time-limited

For previously treated or relapsed refractory CLL once, it’s been about five years. In 2018, we had those randomized phase III studies comparing ibrutinib regimens to FCR or BR reported that ibrutinib had a longer progression-free survival, which is, again, being alive without leukemia. That really put those in very widespread use.

There is some resistance to it just because you have to take the pills for a long time. You take them indefinitely until either leukemia comes back while you’re taking them, you develop a side effect and have to stop taking them, or you have some other health condition that you have to stop.

In younger patients, compared to FCR, ibrutinib even had a survival advantage, meaning you’re more likely to be alive if you took the pills instead of FCR.

When you explain to them that, yes, it is not the first choice, most people decide that that’s better than something that has a shorter progression-free survival or doesn’t work as well.

Most people are more comfortable taking pills long term when they find out that it works better than chemotherapy.

In both people who have taken a treatment before or selecting a first treatment, there are two major standard of care options outside of a clinical trial.

Although I think participating in clinical trials is always something to consider if you can do it. I’ve seen a lot of people benefit from that. You won’t get a placebo without knowing that’s an option. From where I work, we have zero CLL trials with a placebo.

Treatment for relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL

The two standard options are both highly effective. If patients haven’t taken either class of drugs, they’re both excellent, and you can pick based on preferences and side effects.

BTK inhibitors

There are BTK inhibitors, which are pills that target a protein called BTK. This blocks a cell signaling pathway called B cell receptor signaling. This makes the CLL cells not behave like CLL cells and die off over time.

The two main BTK inhibitors that are approved for CLL are ibrutinib and acalabrutinib. Ibrutinib is a once-daily pill. Acalabrutinib is more selective and targets pure things that ibrutinib does. It is a twice-daily pill.

Ibrutinib and acalabrutinib are both excellent options. They’re usually given by themselves, although they can be given with an antibody medication in some cases.

Venetoclax

The other option is another oral targeted agent called venetoclax. It inhibits a protein called Bcl-2, which is an anti-cell death protein. If you block an anti-cell death protein, that’s like a double negative, and it kills the CLL cells really fast.

The problem with this drug is that it has to be started slowly so people can be monitored. It can work so quickly that it can cause tumor lysis syndrome. It is usually given with an antibody and requires monitoring.

Venetoclax treatments are given in a shorter duration. If people are taking it as a first treatment, you give it with an antibody called obinutuzumab and take it for one year. If you’re giving it after people have already gotten treatment, you usually give it with an antibody called rituximab, and you take it for two years.

It’s whether or not they’ve taken treatment before it determines whether or not you take venetoclax for one or two years.

Venetoclax vs. BTK inhibitors

Venetoclax is like a time-limited treatment versus BTK inhibitors, which you take indefinitely till they stop working or you develop side effects and have to quit.

Some people have very strong feelings about if they want to take something and just get it done and stop, or if they’re just fine adding another pill to their pillbox. They don’t want to bother with antibody infusions. They just want to take some pills and go back to working or golfing or whatever it is they want to do.

Both are usually tolerable for the majority of patients. The ones who take long-term, obviously, for some patients have more chronic side effects.

Targeted Therapy Side Effects

Both these treatments are so effective, if you’ve never taken venetoclax or BTK inhibitors before, you can really pick based on your preference for treatment duration, and what side effects may or may not matter for your other health conditions.

btk inhibitors side effects

The main side effects of BTK inhibitors are:

- Bleeding

- Bruising

- Cardiovascular side effects

- Increase in blood pressure – high blood pressure can increase the risk for things like heart attacks and strokes. Overall, it can decrease cardiovascular health.

- Abnormal heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation, or a-fib. A-fib is usually not life-threatening but is very irritating to deal with.

In addition, it can sometimes cause:

- Joint aches or pains

- Inflammatory arthritis

- Diarrhea

- Heartburn

- Rashes – those usually go away or are less of a problem

Most people find the side effects from the BTK inhibitors tolerable, so they still go about their life with these things.

But for someone that has atrial fibrillation or is taking several blood pressure medications already, this might not be the best idea. People with bleeding disorders or who need warfarin anticoagulation don’t want to take this class of drugs if they have options.

Venetoclax side effects

Venetoclax, on the other hand, can cause tumor lysis syndrome at the start. All the CLL cells die so quickly it releases toxins into the blood. That’s treatable, but if you don’t watch out, it can be life-threatening or fatal.

You actually have to start the dose low and increase it slowly. People take a low dose, and over five weeks, they increase the dose every week to get to the full dose of venetoclax, which is 400 milligrams. They have to come for at least two days in a row for blood tests or monitor tumor lysis syndrome every time.

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

With this monitoring scheme, it’s very safe, and people developing tumor lysis syndrome can get that treated usually with medications. Things seem to go very well for people, but it’s a lot of hassle to do that.

To protect people from tumor lysis syndrome, they have to stay hydrated. People who have heart failure, take diuretics or have kidney impairment, which could make tumor lysis syndrome more common and more dangerous, might not want to go this path just because that’s a greater risk to their health.

Once people are at the target or treatment dose of venetoclax, it actually seems to have fewer chronic side effects than the BTK inhibitors. Some of them include diarrhea, lower neutrophil count or neutropenia (neutrophils are infection-fighting cells).

People can sit down and look at their health conditions. If they have severe kidney impairment, they probably want to take a BTK inhibitor. If they have abnormal heart rhythm problems, they would want to take the Venetoclax.

It’s a decision you make together with your treating physician.

I sometimes see patients considering their options for first treatment who ask me right off the bat, “Which one should I do?”

I say, “I don’t know, we just met. I need to ask you some things about you, and then I can tell you what you might want.”

I think these are really important, and the discussion is very similar for people picking a treatment that has taken before but never taken either of these classes of drugs before.

»MORE:Learn more about the process of clinical trials from one program director

Clinical Trials

Triple Therapy (Ibrutinib, Venetoclax, Obinutuzumab)

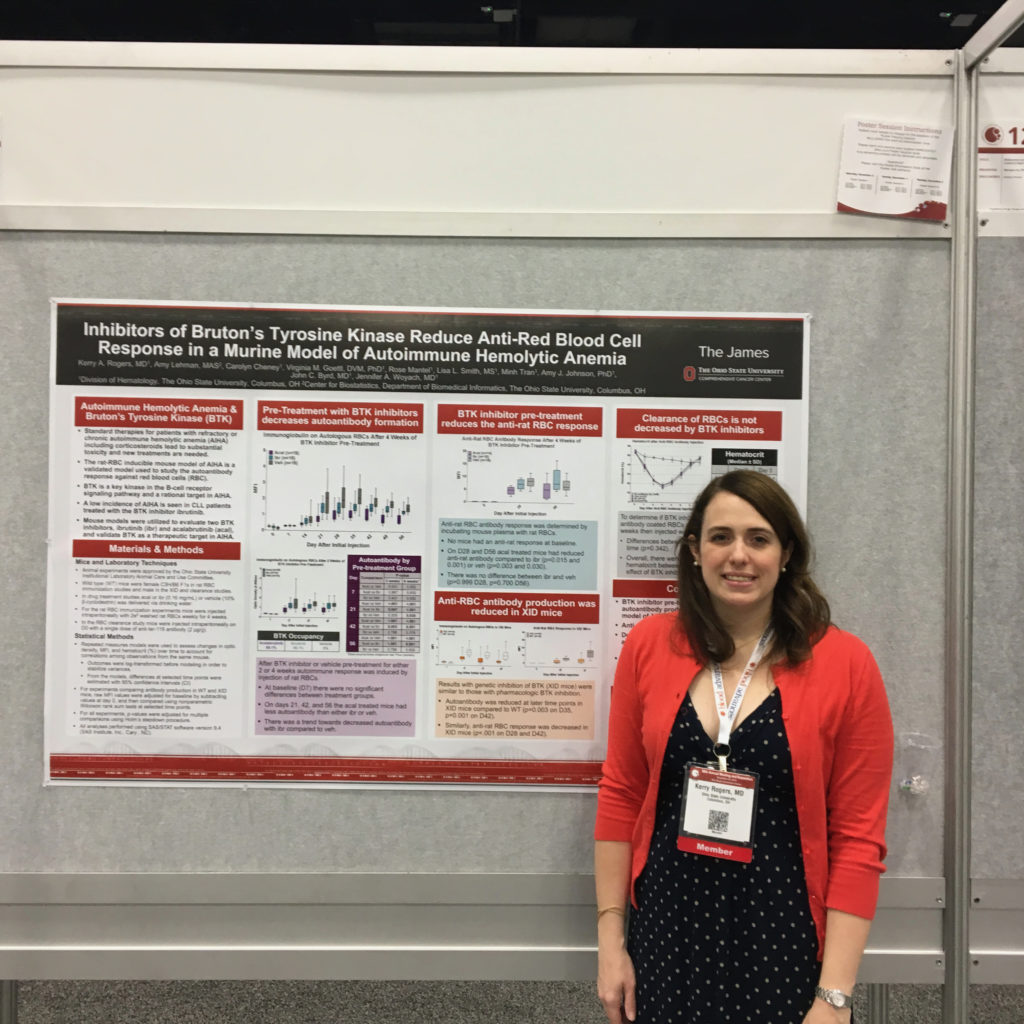

We always like to make treatment safer and better for our patients. So we had a study combining the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib, venetoclax, and an antibody, obinutuzumab, as a treatment for one year. It’s ongoing in follow-up, but everyone in this study has completed treatment.

When you give more drugs together, you get more side effects. It’s not a surprise, but the nice thing about this is it’s one year, and now we’re seeing how long people remain in remission at the end of that one year of treatment.

So far, we’re at about three years of follow-up, and it looks very good.

We’ve treated people with both relapsed/refractory CLL and people taking this as a first treatment. Several other studies are going on for BTK inhibitor and venetoclax combinations. We expect the response rates to be very high, but we are excited to know how long people remain in remission with this.

We hope to learn with longer follow-up who might most benefit from this combination and who’s going to stay in remission longer than with other things.

I’m just super excited that we really move the mark and get regimens into the standard of care in CLL and are able to do a randomized phase III trial, where you sign people to treatment in your treatment.

Again, there’s no placebo here, and usually, you know which one you’re getting to, after you randomize. You don’t know when you sign up, but you know before you get treated.

There are two ongoing studies, one through the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, or ECoG, and one through the Alliance. Those are both US Oncology Cooperative groups that do studies conducted on hundreds of sites across the US. They are both randomizing patients to ibrutinib and obinutuzumab.

You take the antibody for a limited time, but the ibrutinib indefinitely, and then the three-drug combination, ibrutinib, venetoclax and obinutuzumab given for a fixed duration. You don’t take it forever, and they’re looking at progression-free survival.

One study is for younger individuals, one’s for older individuals. They have a few small differences, but that’s mainly what they’re looking at.

»MORE:Read more on FDA approvals of clinical trials

I am excited to see over the next several years how that turns out, and I’ve also treated several people in that study who were really excited to participate in it.

You have to emotionally think it’s okay to be randomized, but a lot of people thought it was fun. They were like, “Oh, great, I’m going to get one of two great things, and I don’t have to pick.”

Metrics for these studies

When you pick a new standard, you compare standard treatment, which in this case is ibrutinib and obinutuzumab, to an investigational treatment, which is that three-drug combination.

The main goal is to determine progression-free survival: how long people are alive without leukemia and if one’s longer or shorter than the other. That’s a measure of how effective these things are.

Some studies use the overall response rate, but these drugs are so effective that they don’t really work out CLL because everyone responds to these things, which is great, by the way.

Then, when we look at the patients in the study who had high-risk features, low-risk features. Then we see how our high-risk patients did compared to high-risk patients with the other treatment.

For ibrutinib, some people have their leukemia come back while they’re still taking it.

Determining resistance to treatment

We have some neat studies going on at our institution and some other institutions across the country, looking at how we can identify who’s developing resistance to ibrutinib before they actually get sick.

We can look at mutations in BTK, which is the protein that binds at the drug binding target. Once people develop mutations in BTK, in particular spurts, we know that the drug will stop working.

We’ve offered them clinical trials to add a second drug like venetoclax to reduce this resistance and see if we can keep the leukemia from relapsing and be healthy for longer.

The CLL Community is looking at adding a second drug to people who are on ibrutinib and doing well. Remember, I said that ibrutinib, and actually, acalabrutinib II, which is the other BTK inhibitor, changed the way the CLL cells work and behave, but it doesn’t actually kill them off.

Lots of people still have CLL floating around, which is why we think they need to keep taking those drugs. We’re wondering if people can have another drug added to it to just knock out those residual leukemia cells. That way, they can be in off-treatment remission. If you do that, then they won’t be on it long enough to get resistance ideally.

Importance of clinical trials

It’s always good to know what your standard options are, and what your clinical trial options are.

For people who haven’t taken BTK inhibitors or venetoclax, those are good standard options. For people who are resistant to both those, usually clinical trials are your best option.

You always want to know what drug is being studied, how the study is going, who’s been in it, and what your doctor expects from the study.

Misconceptions about clinical trials and “placebos”

In cancer trials, you would know there was a placebo because you have to sign a consent saying there’s a placebo. But it’s usually considered unethical to give people who need cancer treatment a placebo.

It will explain if it’s randomized and what are the treatments that you would be getting. A lot of studies, especially the ones we have, are studying very new treatments. Sometimes they’re studying the dose of the drug.

You should know exactly what drugs you’re getting. It can feel really weird but you should consider your options.

With the state of cancer research these days, we actually have a very good feeling that these drugs are going to help patients before we give them to patients. Many of them have been studied obviously in the lab using CLL cells; cell lines have been studied in animal models of CLL.

We don’t start trials with new drugs until we’re fairly confident that it will help people. I’ve seen many patients benefit from drugs that they wouldn’t be able to get just because they’re not yet approved.

If anyone’s considering it and unsure if they have someone they know in the CLL community or peer support for someone that’s been in a clinical trial, it’s always good to talk with people who have done it just because the individual benefit to doing something like that can be significant.

People always tell me, “Oh, I feel like I’m your guinea pig.” I’m like, “Oh, you should be so lucky to be my Guinea pig, you know what that thing’s lifestyle is?” I was like, “My personal guinea pig is not an experimental animal. It’s my pet, has a super nice lifestyle. People would love to be my guinea pig.”

But really, people aren’t guinea pigs as much as you think. If you’re considering a research study, make sure you get to ask all the questions about what the drug is and why being in this study might benefit you or others, and your doctor should be able to answer those questions for you.

Up and Coming New Treatments

CAR T cell therapy

CAR T-cell is exciting. It’s still investigational for CLL, but I’ve seen it help a subset of patients, especially those that are resistant to these drugs I’ve been talking about. It can be very powerful for select people, but it is a hassle to do, and it is still investigational.

For people who have very good, other treatment choices, it’s usually not something we run to as a first treatment or even a second treatment. But it can be great for people that need that.

Reversible BTK inhibitors

The things that I’m excited about are some drugs that are hopefully going to move up to benefit more patients. We’re always trying to make treatment safer, more effective.

There’s reversible BTK inhibitors. Ibrutinib and acalabrutinib bind BTK at the same site and bind it irreversibly, meaning forever.

Reversible BTK inhibitors bind at different sites than the two approved ones and bind and unbind BTK, which seems to limit some of the side effects.

Also, for some reason, these drugs can work in people who are resistant to the BTK inhibitors, which you expect ’cause they bind to it at a different site but can work in people resistant to BTK inhibitors and Venetoclax. They seem to be very well tolerated.

A reversible BTK inhibitor such as LOXO-305 (pirtobrutinib) is now under study. LOXO-305 is the one that’s the furthest in development, and they just gave it a direct name.

It’s just exciting when I go to professional meetings to see what new types of drugs are being developed in CLL or things like cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors that are coming back into play. These drugs, either alone or in combination, are likely to benefit patients.

Again, we keep moving the mark more and more towards safe, highly effective treatment, and it just keeps getting better.

New drugs with new mechanisms, drugs with the same mechanism but in a different way—these are the way we move the mark in CLL.

It seems to have fewer side effects, not no side effects. Anyone that tells you there’s are no side effects is lying. You never get anything for free or don’t do anything. But, that, and also because the mechanism is different from the irreversible BTK inhibitors, it can be used in resistance.

If someone takes ibrutnib until their leukemia comes back while they’re taking it, taking acalabrutinib isn’t going to work because they have the same mechanism. But taking a drug that binds the same protein but with a different way of doing it can work after your resistance.

This allows people to take two BTK inhibitors before moving on to a drug like Venetoclax or other treatment options. They’re just really effective, especially in people with really resistant CLL. It’s not just that there are fewer side effects, but also they seem to work great, which is awesome.

Treatments for Hairy Cell Leukemia (HCL)

Hairy cell leukemia vs. chronic lymphocytic leukemia

I love talking about hairy cell leukemia, which is another chronic B-cell leukemia. It also has very long survival rates, but it has some different features than CLL.

Unlike CLL, it’s very rare. It’s not very common to have people diagnosed with hairy cell leukemia.

HCL Treatments

Purine analogue chemotherapy

Over the last couple of decades, purine analogue chemotherapy was developed for hairy cell, and it’s actually spectacularly effective for the majority of patients.

People can take a single course of purine analogues and be in remission for decades sometimes. But there’s a group of hairy cell leukemia patients who don’t get decades of remission from purine analogues, or aren’t able to take them for other reasons such as side effects.

New drugs (cladribine, pentostatin, vemurafenib)

The hairy cell community has been working on new drugs for this group of hairy cell leukemia patients who aren’t expected to benefit from purine analogues like cladribine or pentostatin.

There are a couple of drugs in this area that are available and FDA-approved for people. But vemurafenib, which is not approved for hairy cell leukemia, has been very well studied. It can be used in people with hairy cell leukemia with a BRAF mutation which is found in the majority of people with classic hairy cell leukemia.

But there’s still a need for new drugs for this group of patients as those drugs don’t cover everybody.

We have actually conducted a phase two study of ibrutinib. It’s been FDA-approved for four different cancers. We’ve studied it in hairy cell leukemia, in a group of patients who aren’t expected to benefit from purine analogues.

People who have been previously treated or people with a variant of hairy cell leukemia have been found to have a very long progression-free survival. Around 73% of people are alive for three years without their leukemia returning.

The response rates don’t look quite as high, but that’s probably the response criteria we were using. You can really see how many people benefited by looking at progression-free survival.

It’s definitely a really important treatment option for people with this rare leukemia that aren’t expected to benefit from therapies like Purine analogues.

I think we published those results in a journal called Blood recently so that other doctors could find them and think about using that for their patients with a hairy cell that might need something beyond purine analogues.

Prognosis and findings so far

The prognosis for hairy cell, in general, is quite good. Most people can expect to finish their natural life span. Some people die of infection and rarely will someone die of leukemia.

Before purine analogues, survival was actually expected to be a couple of years, and not a couple of decades. When people don’t benefit from purine analogues, usually, they take more treatments, and their lifespan can be shortened by this. It’s still possible depending on what treatments you get to live for years.

It’s not like people had a very, very short survival, but certainly not the decades you’d expect from people that really get a lot of benefit from purine analogues, and other treatments like vemurafenib which is usually given for a fixed duration. Their relapse-free survival, or roughly how long it is before the leukemia returns in the majority of patients, is less than two years.

With this ibrutnib study, people are still alive without their leukemia returning for three years. Almost three-quarters of them are really quite good.

The study has been open since 2013. Some people have been in it a really long time, and I look forward to continuing to see how it benefits those patients. Some people are obviously quite sick and had taken 8 or 10 treatments before being in the study and probably wouldn’t be doing very well if they hadn’t been in a research study.

It’s also a nice example of how participating in a clinical trial can benefit people, because folks with hairy cell leukemia would not have had access to this if they didn’t decide to be in a research study.

More Medical Expert interviews

Dr. Christopher Weight, M.D.

Role: Center Director Urologic Oncology

Focus: Urological oncology, including kidney, prostate, bladder cancers

Provider: Cleveland Clinic

...

Doug Blayney, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in breast cancer | HER2, Estrogen+, Triple Negative, Lumpectomy vs. Mastectomy

Experience: 30+ years

Institution: Stanford Medical

...

Dr. Kenneth Biehl, M.D.

Role: Radiation oncologist

Focus: Specializing in radiation therapy treatment for all cancers | Brachytherapy, External Beam Radiation Treatment, IMRT

Provider: Salinas Valley Memorial Health

...

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

...