Lynch Syndrome: What Patients Need to Know

A Q&A with Lynch syndrome specialist, Michael Hall, MD, MS

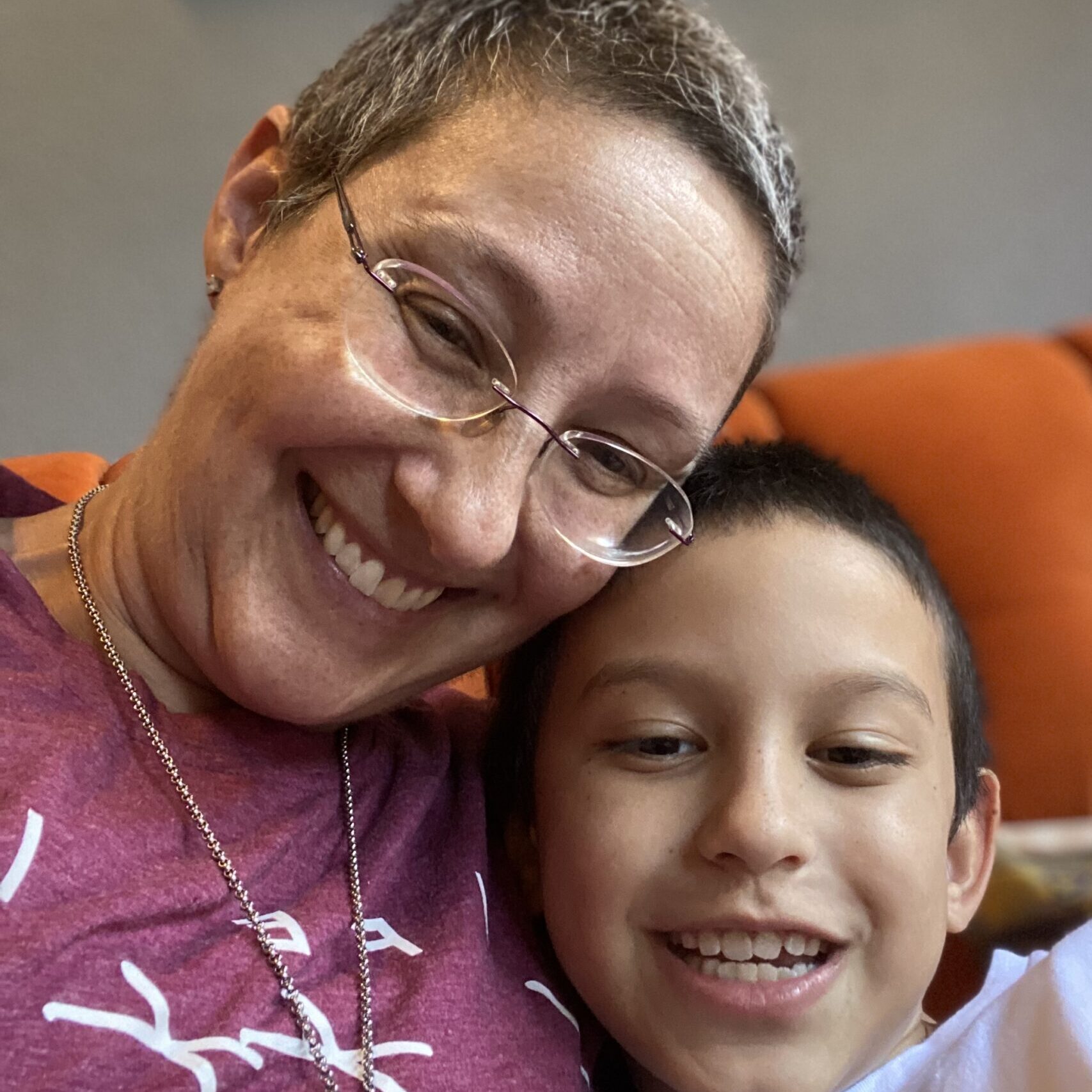

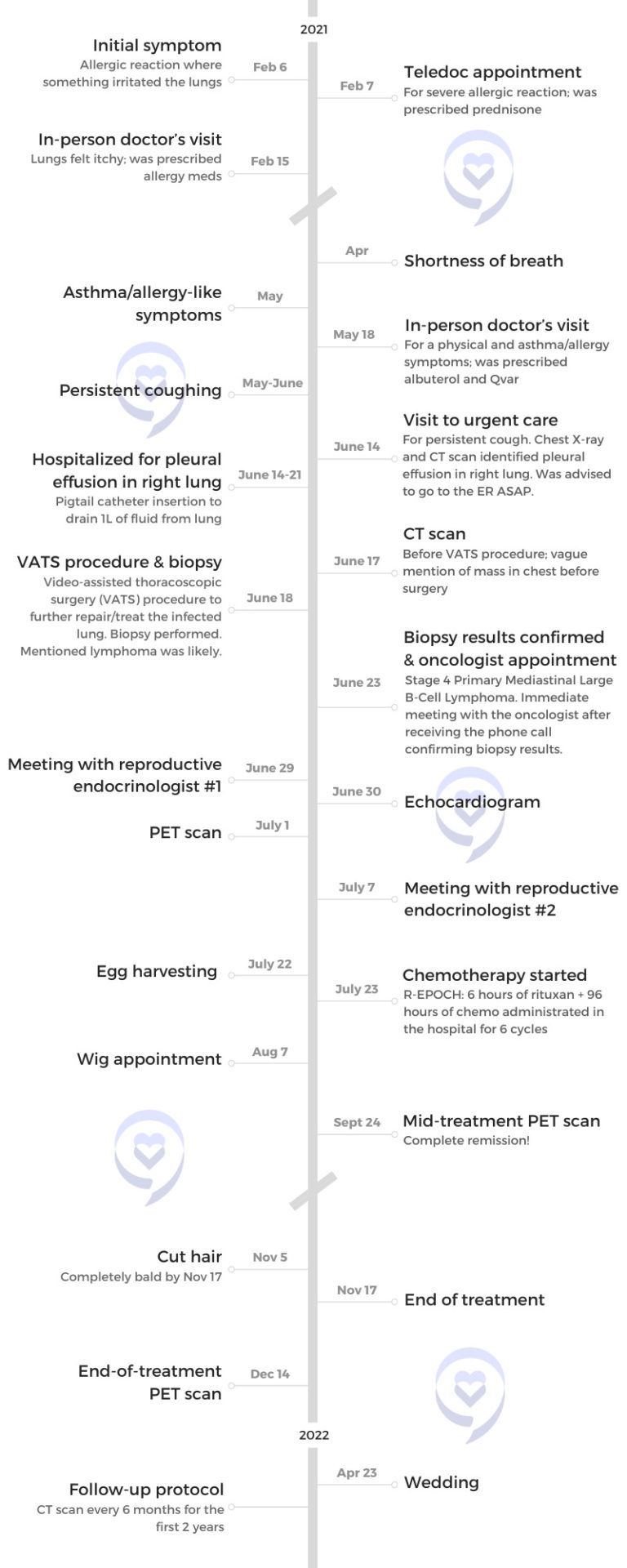

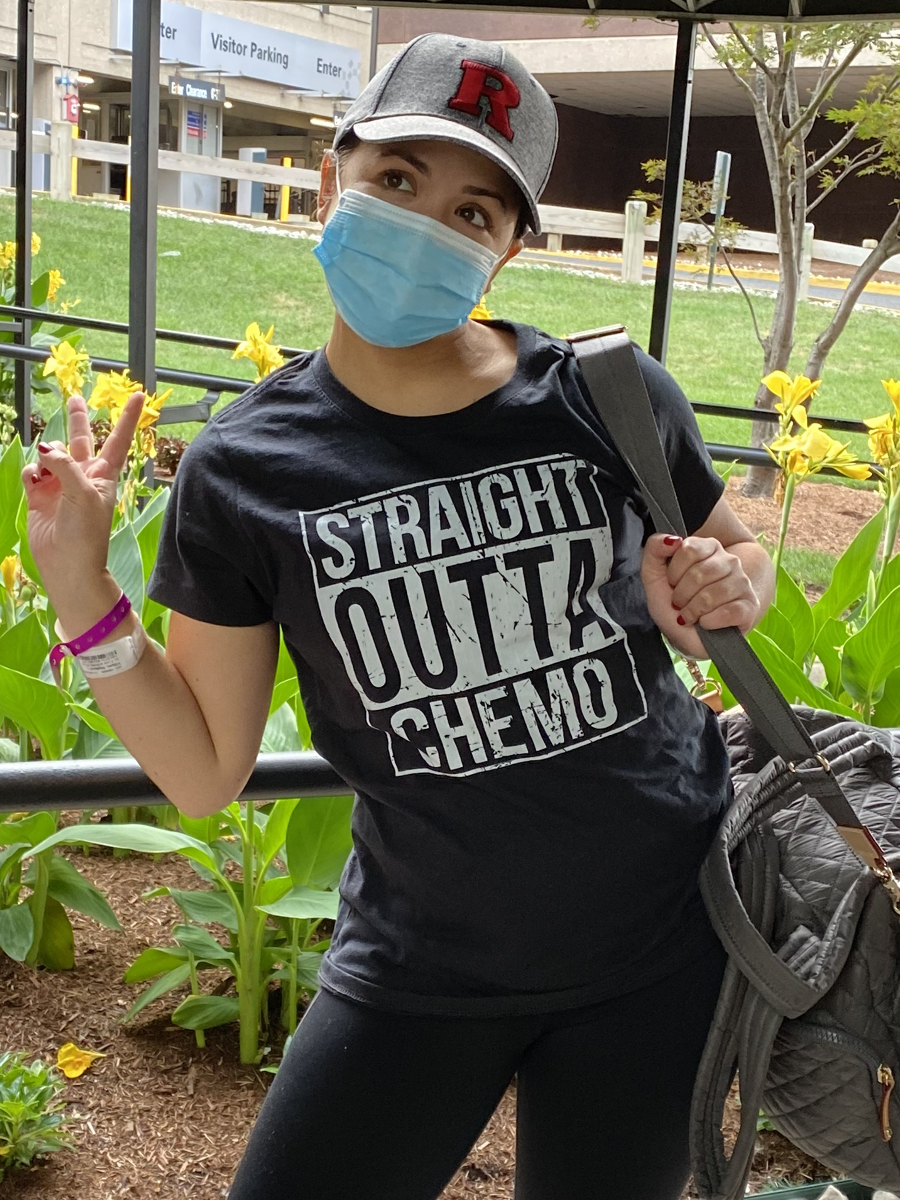

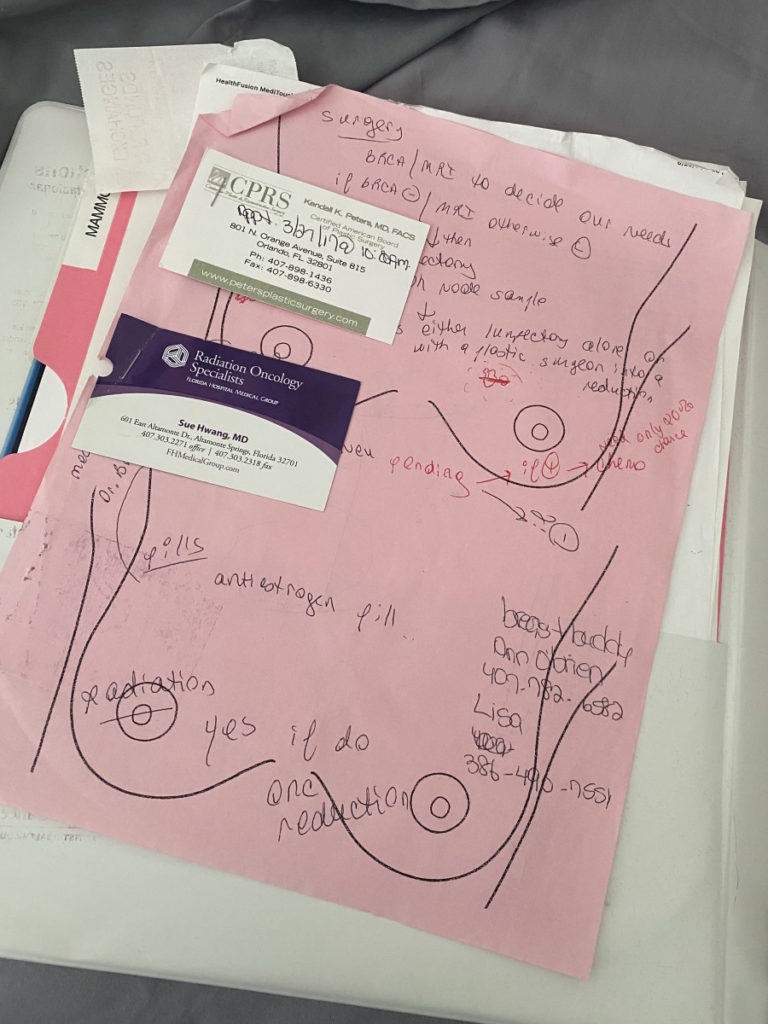

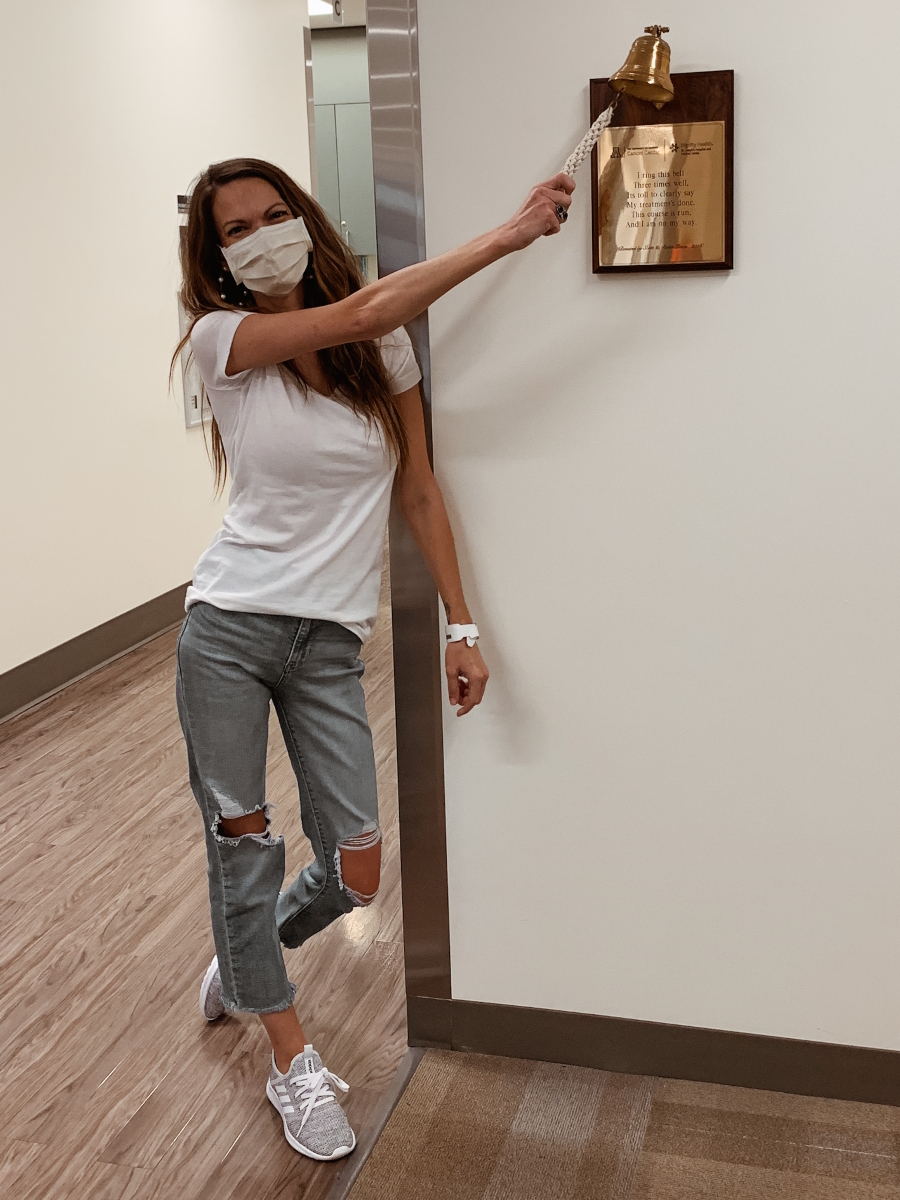

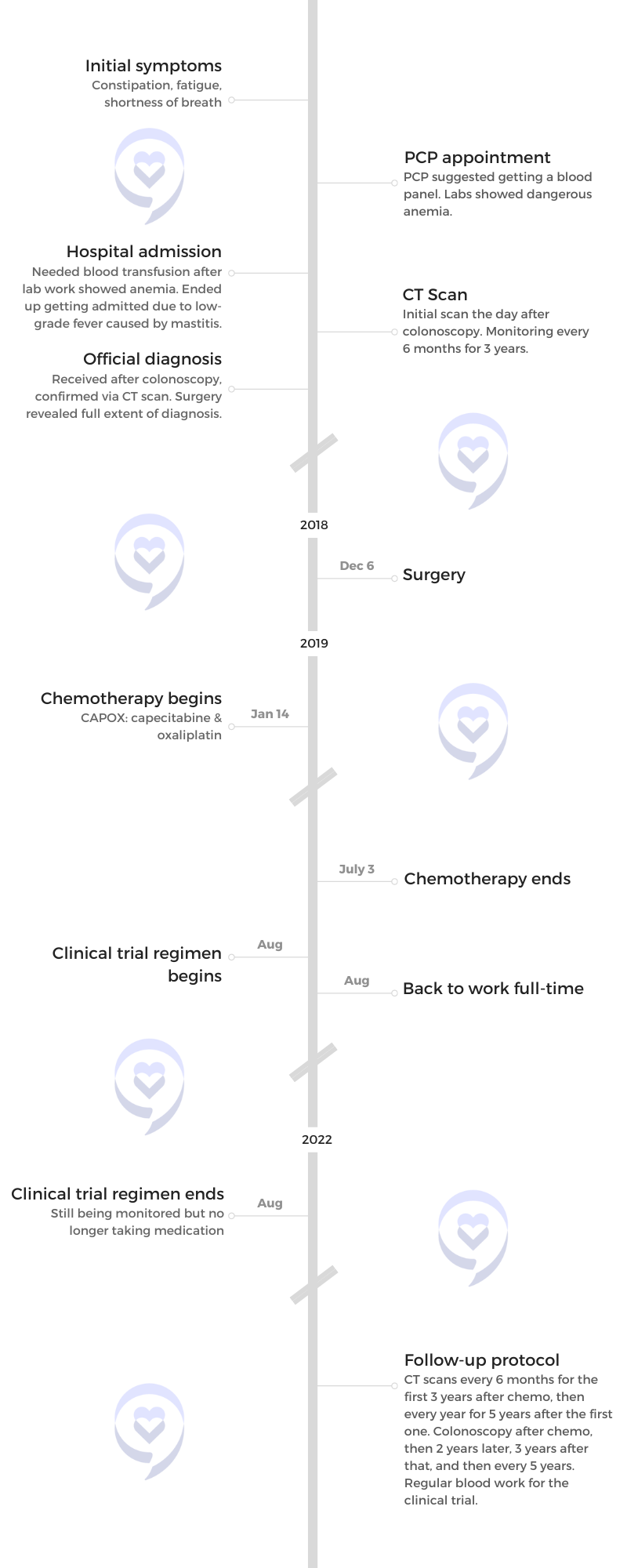

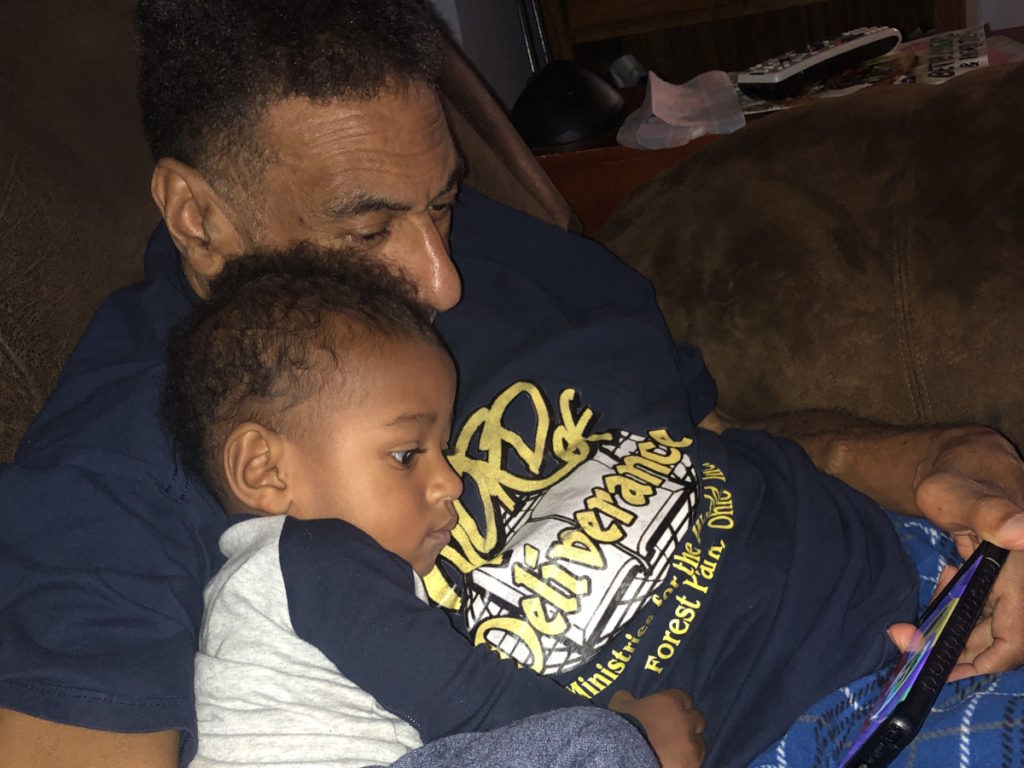

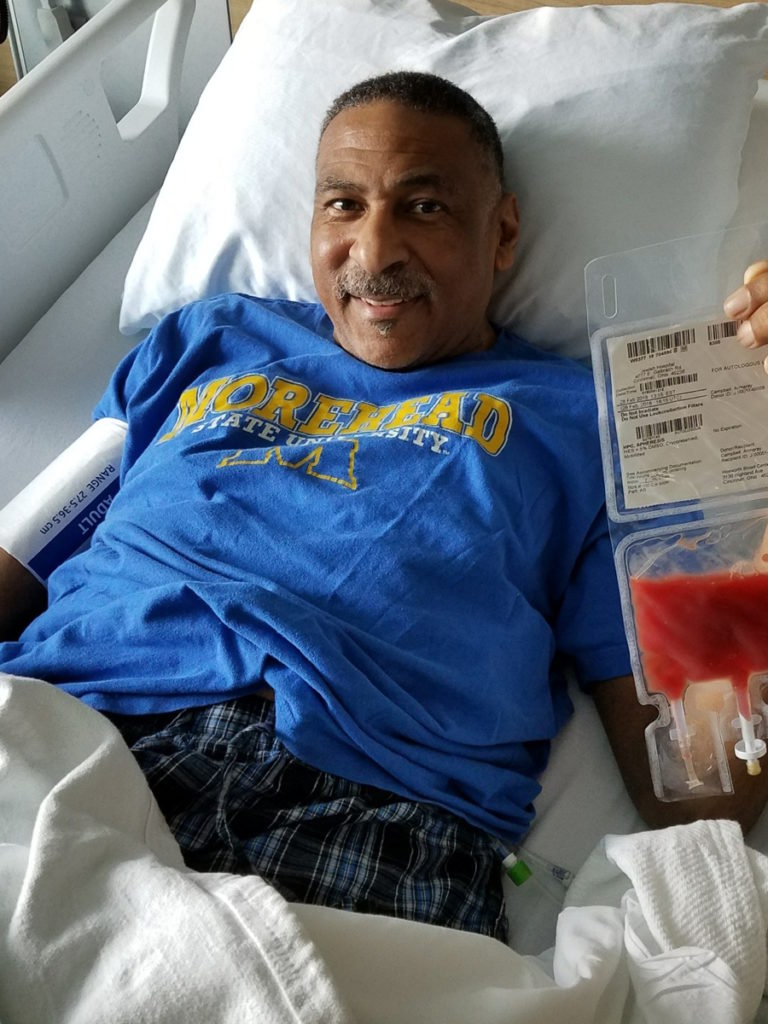

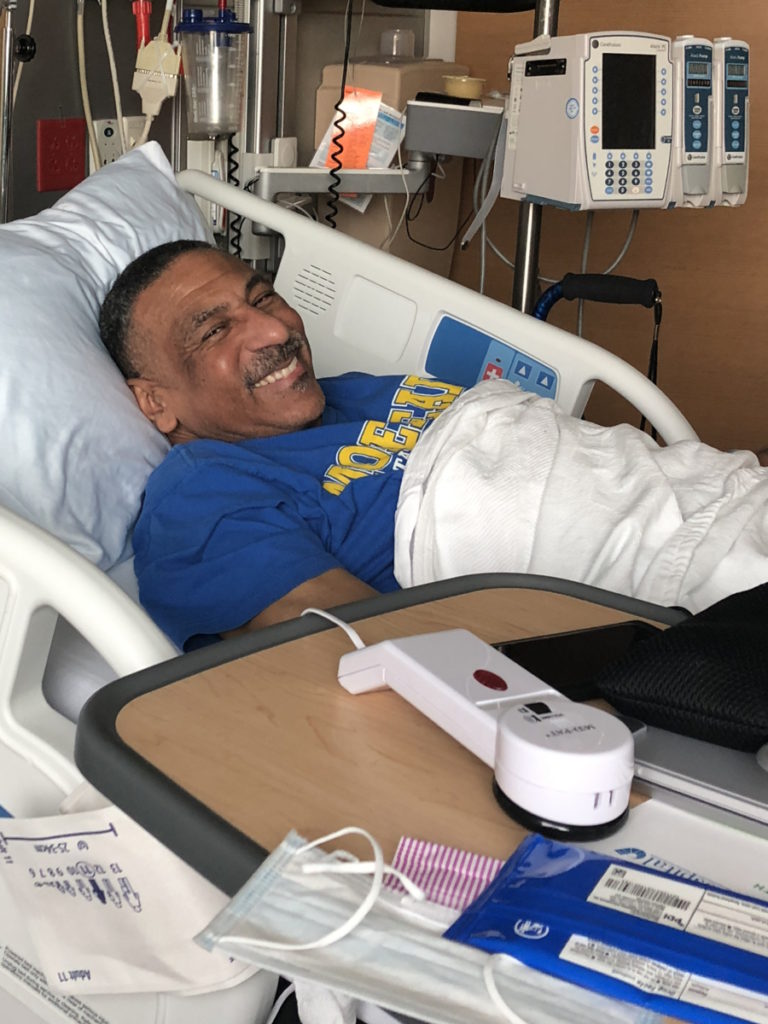

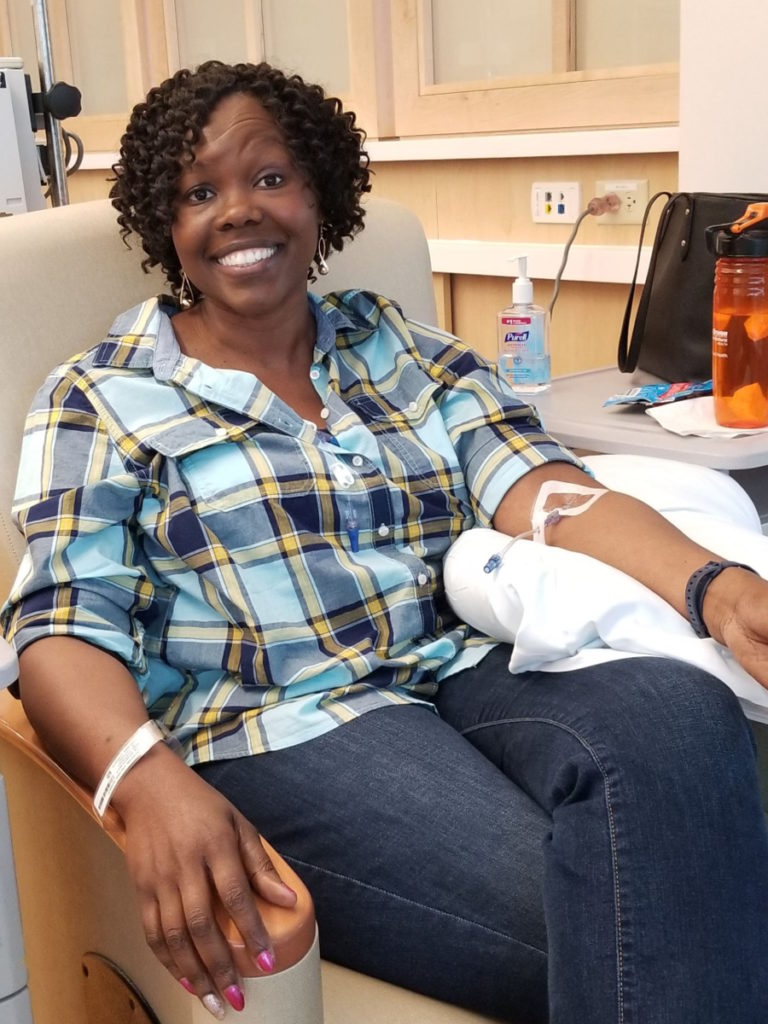

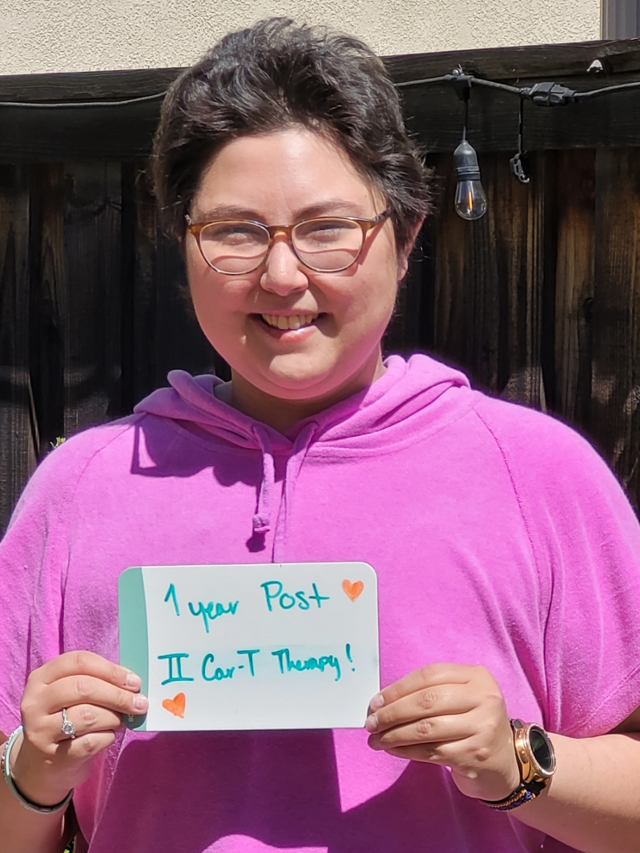

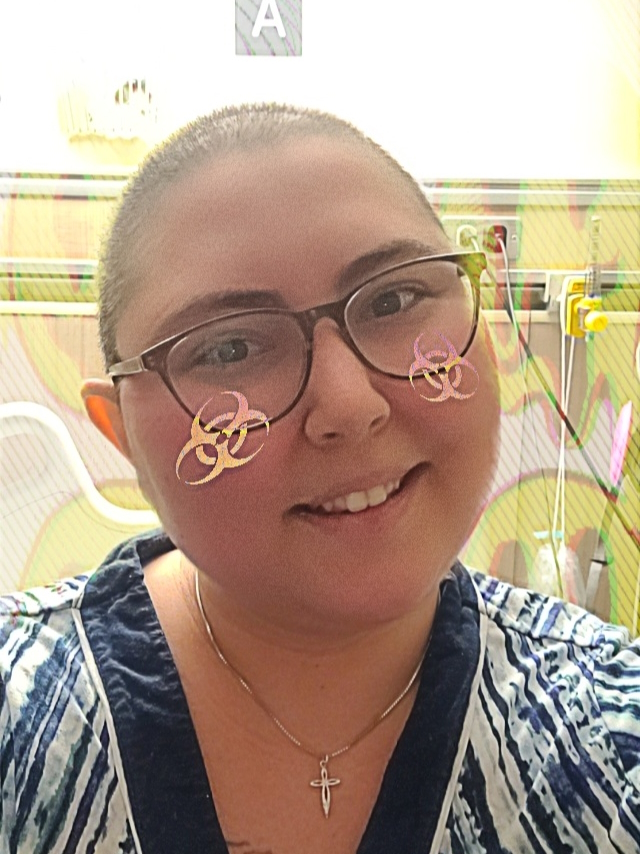

When Jackie was diagnosed with 3B/4 adenocarcinoma, her GI doctor suggested she may also have Lynch syndrome, a condition that increases the risk of developing numerous cancers. Families with Lynch syndrome typically have more family members who are diagnosed with various cancer, according to the Mayo Clinic.

After a genetic test, the condition was identified in Jackie’s results and she became the first person in her family to identify Lynch syndrome in her family’s DNA.

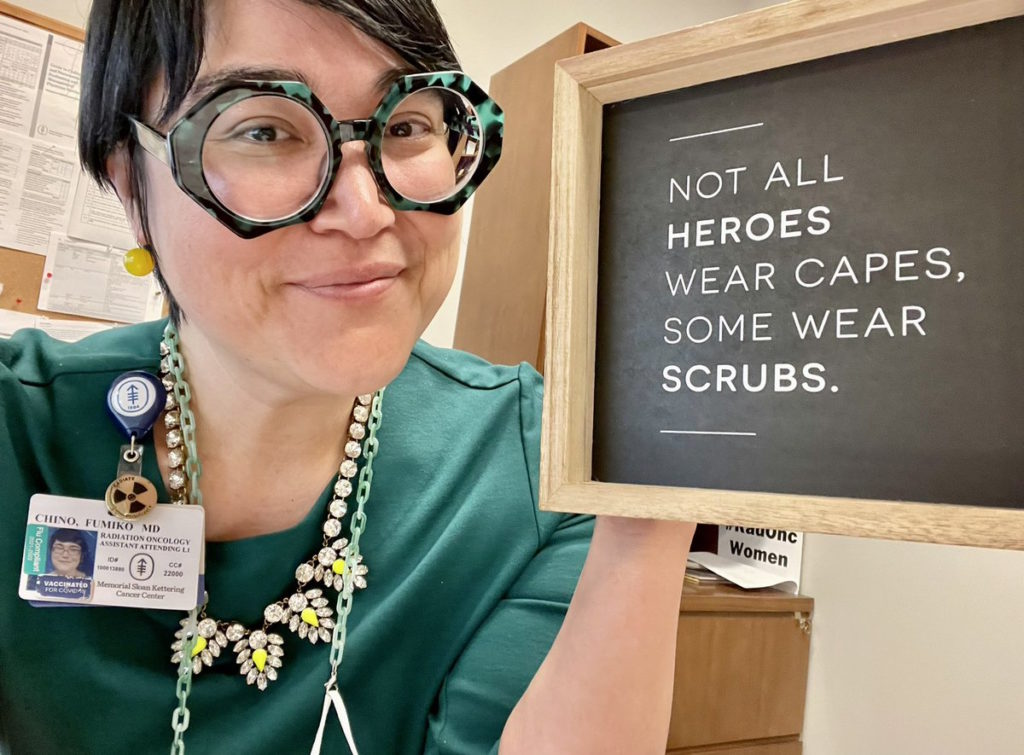

To better understand Lynch syndrome and how to test for it early, The Patient Story spoke with Dr. Michael Hall, a medical oncologist at Fox Chase Cancer Center.

He is the chairman of the Department of Clinical Genetics and co-leader of the Cancer Prevention and Control Program, one of the cancer center programs at Fox Chase composed of various researchers.

In this conversation, he discusses Lynch syndrome, what cancers patients would be more at risk for, and who should get tested.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Introduction

- What is Lynch syndrome?

- What cancers would Lynch syndrome patients be more at risk for?

- How does age play into this?

- Who should get tested for Lynch syndrome?

- How does genetic testing help with the treatment plan?

- Is there a vaccine coming out for Lynch syndrome?

- What is the process of getting tested for Lynch syndrome?

- Is there a risk in panel-based testing?

- What is ICD-10?

- Conclusion

Lynch syndrome is common enough that I think any young patient or any patient who has colorectal cancer, if not now but in the near future, really should be tested for this syndrome.

Dr. Michael Hall

Introduction

How did you get into medicine?

My mother was a nurse and I just found the stories of medicine interesting and compelling. I took a couple of years off after undergrad and realized that it was definitely what I wanted to do.

I went to medical school at Columbia. Spent some time in Boston for my residency, [in] Chicago to do some training for fellowship, and then, ultimately, matured into an oncologist.

Since I became a full-fledged oncologist, I’ve worked at a couple of places. I was at Columbia in New York for a few years, got some great mentorship from the cancer epidemiology team, and got my first grant.

Then I became interested in Fox Chase. There were a number of people who were working in this area of hereditary genetics, cancer, and Lynch syndrome. At that point, I recognized a great opportunity.

I was also a little tired of living in New York so it ultimately all worked out. I moved and I’ve been at Fox Chase since 2008.

How did you get into Lynch syndrome?

My interest in genetics and Lynch syndrome started during my fellowship training at Chicago. I was mentored by a giant in the field, Funmi Olopade. She was a major force in BRCA1 & BRCA2 research.

I was interested in being a GI (gastrointestinal) oncologist. She said to me, “If you’re going to be interested in GI oncology, you need to get interested in the GI syndromes then.”

I started out being interested in pancreatic cancer. Then that evolved over time to GI syndromes, like Lynch syndrome and FAP (familial adenomatous polyposis).

What’s been amazing about Lynch syndrome research is when I first started in this field, everyone looked at Lynch syndrome as incredibly rare. It’s good to have one person at the center who knows a little bit about it, but you’re probably never going to see it. No one knew anything about MSI (Microsatellite Instability) testing, IHC (immunohistochemistry), or any of those things.

In just a few short years, we’ve seen Lynch syndrome with the emergence of immunotherapy, with some great research coming out of the Australian group and an Ohio State group. This disease is actually incredibly common in the population.

The total turnaround has been really an eye-opener to me about how much science can change over a short period of time. It also has opened up a big opportunity for us to identify a large swath of the population who have this very common risk that we can actually do something about. That’s been really inspiring as well.

Whenever you’re in a research area, it brings you together with other folks who are interested in that same area and that’s led to a wonderful peer group that I’ve developed over the years. Everyone [is] focused on this same goal of addressing Lynch syndrome, hopefully making the lives of our patients better.

What is Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome is a risk. It’s like driving your car without a seatbelt. You can, you could drive all over town without a seatbelt on and never have something happen to you. But Lynch syndrome is if you did have an accident, something could happen.

This is an inherited risk in one of four genes that we know are related to editing and repairing small mistakes that get made in an individual’s DNA. When that DNA is being replicated or gets damaged, usually it’s because when our cells replicate, that has to happen very quickly. We have billions and billions of cells so those enzymes, that are in place to replicate our DNA and form two new cells, have to work really fast.

They make mistakes along the way. Human beings have a lot of amazing backup pathways. If those mistakes get made, there are groups of genes and enzymes that come in to repair those mistakes.

Lynch syndrome is one of those families of genes called the mismatch repair pathway. There are very specific times when our cells and our bodies need that pathway to work. Individuals with Lynch syndrome have a risk that that pathway can get disabled.

If that pathway gets disabled, there can be an accumulation of small mutations that happen throughout important genes. That accumulation of mutations and the dysfunction of those genes ultimately can lead to cancer.

At the same time, what’s been discovered in recent years is that [the] pathogenic process of mutations accumulating is actually very, very distinct to people with Lynch syndrome. We’ve been able to harness that distinctness and the ability of our immune systems to recognize the tumor, the process of tumors forming in Lynch syndrome, to use immunotherapies to help our own immune systems basically turn on a Lynch syndrome cancer.

We’ve seen [this] in medical literature. I’ve had a number of patients in my practice. Examples now are all over the place of people who have metastatic cancer with Lynch syndrome [and] can be cured with immunotherapies. This, unfortunately, doesn’t happen for everyone, but the chances are actually pretty good.

This is how this syndrome works. It is basically a risk of accumulating these mutations. Again, if one is lucky, that risk may never play out in the formation of cancer. However, we know that risk is elevated compared to average-risk individuals in the population.

That accumulation of mutations and the dysfunction of those genes ultimately can lead to cancer.

What cancers would Lynch syndrome patients be more at risk for?

The classic group of cancers, especially colon cancer, is always going to be near or at the top of the list. There are these four, some people say five, genes that contribute to Lynch syndrome. Two or three of the genes are actually [at] higher risk to develop colon cancer. The other two genes are perhaps a little lower risk or later onset cancers.

Endometrial cancer is also at the top of the list, particularly for women who have uteruses. There are some families where endometrial cancer is actually the dominant cancer.

Then there are others, ovarian cancer [and] gastric cancer. We do sometimes see small bowel and pancreatic cancers. We can see cancers of the ureters and then there are some Lynch syndrome families who can get skin manifestations as well. They’re not cancers; they are growths that you want to get rid of if you get them.

How does age play into this?

There have been some studies looking at this. What appears to be a shifting of the age of earlier onset colorectal cancer, I can say with reasonable confidence, is probably only slightly explained by the syndromes we know about like Lynch syndrome, FAP (familial adenomatous polyposis), and others. The prevalence of those syndromes is pretty constant in the population so we wouldn’t really expect those to be causing a shift in the age of cancer diagnosis.

What I think is more likely is other genes plus environmental factors. Genes that we perhaps don’t know about right now or how they’re involved in this plus environmental factors like [the] food we eat, how we exercise, or how well fed we are. Actually, our nutritional status as human beings is a lot better now than it used to be many, many years ago.

All of these things probably play into changes in the rates of cancer that we see in the population and the ages at which those develop. I think it’s important to always, in these young cases that we’re seeing, think about Lynch syndrome. Test these individuals. But I don’t think this explains the shift.

Everyone with a diagnosis of cancer should have access to hereditary genetic testing if they want it…The tougher question is: how do we test everyone else? If you’re testing patients with cancer, you’re behind the eight ball.

Who should get tested for Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome is common enough that I think any young patient or any patient who has colorectal cancer, if not now but in the near future, really should be tested for this syndrome.

The Ohio State group and others show that if you test patients with colorectal cancer under the age of 50, you’re going to find that about 8% or 9% of those colon cancers have Lynch syndrome. If you test over 50, it’s going to be a smaller chunk, but it’s still going to be a pretty significant percentage of people.

If you look overall at all colon cancers, Lynch syndrome comes in roughly about 2.8% to 3% of all colon cancers and that’s common. Especially because we have great ways to screen these folks, we have other things we can do. There are emerging new prevention approaches. With a disease that is common, we should really be testing everyone.

Testing has become much more accessible [and] much cheaper. What we’re seeing is national guidelines shifting direction — full disclosure: I’m part of some of them — recommending this testing for all colon patients. I think it will not be too many years before that is fully endorsed by the whole medical community.

There have been some great data from Jewel Samadder’s group from Mayo Clinic showing that if you take all comers with any kind of cancer and you test them with a large gene panel, you’re going to have roughly a 10% chance that you’re going to find some relevant gene that relates to people’s risk of cancer that’s actionable and meaningful.

That tells me that everyone with a diagnosis of cancer should have access to hereditary genetic testing if they want it. Not everyone wants it. I think the tougher question is: how do we test everyone else? If you’re testing patients with cancer, you’re behind the eight ball.

What we want to do is test people who are in their 20s and 30s, who have their lives ahead of them, can plan ahead, can think about, “Am I going to smoke or not? Am I going to drink or not? Am I going to exercise or not?” Because that’s where we can really make an impact on preventing cancer in the population. Identifying those folks for whom we should focus resources like frequent colonoscopies and other things versus individuals who don’t have to worry about that.

Clues like mom had ovarian cancer: huge red flag. You need to get testing. We can use information from population genetics to help individuals understand what risks they may be facing.

A nice study out of the UK showed that if you tested lots of folks for Lynch syndrome, not based on family history, you’re going to find meaningful mutations in many folks who never have a family history of cancer. But those folks can still go on to get cancer themselves. Family history helps you, but it’s far from perfect.

When you think of a world where this is a common disease and testing is relatively cheap, I can tell you being in this business, it’s much nicer to know you have a risk and prevent [it].

We do a lot of survey groups in my research team looking at patients’ preferences for different kinds of ways of preventing disease. We asked them, “Would you want to start taking immunotherapy or start using aspirin or exercise three times a week?”

The kind of prevention people are actually most interested in are actually nutritional interventions. People want information that guides them, that helps them eat better foods and foods that will help them prevent disease, much more so than they’re interested in things that are more invasive or they may perceive as being riskier. Helping them understand those risks early in ways that they might be able to address them is really important.

What we want to do is test people who are in their 20s and 30s, who have their lives ahead of them, can plan ahead… Because that’s where we can really make an impact on preventing cancer in the population.

How does genetic testing help with the treatment plan?

It does [help], especially the immunotherapy part. Immunotherapy really put Lynch syndrome on the map a few years ago. There was an “Aha!” moment in science that was huge. It doesn’t matter whether it’s colon cancer, endometrial cancer, or whatever.

In this process of DNA mistakes that happen in the tumor, there are proteins produced that are non-native to our body. There are these little fragments of proteins that our cells wouldn’t normally make. A patient’s immune system recognizes those and realizes that [they] shouldn’t be there. The tumors very quickly hide away from the immune system. When I describe it to my patients, it’s like they put up little umbrellas to hide under.

This therapy that was developed and came on the market a few years ago, what we call immune checkpoint blockade or anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy, basically is able to take down those umbrellas [and] allow the immune system to swoop in. In a large number, although not 100% of cases, [it] can sometimes allow an immune system to completely control a tumor if not cure it.

It is incredibly important these days for patients to be tested early on, especially [with] colon, endometrial, and several other tumors, to find out whether their tumor is MSI high or looks more like Lynch syndrome versus not.

Of course, there are some MSI high tumors that are not Lynch syndrome. But again, that’s a really important question that needs to be asked early on in the treatment of almost every cancer these days.

Is there a vaccine coming out for Lynch syndrome?

As is often the story of medicine, there’s been lots of great research over the years, particularly by a group in Germany, but they’re not alone.

A very smart scientist Matthias Kloor and the team that he works with in Germany [is] looking at these peptide fragments that these tumors make that the immune system recognizes, analyzing them, purifying those, and developing vaccines that would be able to stimulate the immune system to recognize those and hopefully enhance the immune response.

They also identified peptides that were common across lots of different Lynch syndrome tumors, like endometrial cancer [and] ovarian cancer. There are ones that are commonly produced by all tumors.

There are some trials now going on. There [are] at least two. One that’s ongoing in the US that I’m part of, based out of an MD Anderson consortium. This small trial is basically looking at whether the vaccine will stimulate the T cells in patients. This is a small early study. If that goes well, the next step would be a larger study to look at some specific cancer or some intermediate outcome.

There’s also another study that’s going to be opening, which will also be looking at another vaccine, but [with a] similar idea. We’ll initially look at the stimulation of the immune system but also at some biologic endpoint.

There may also be others along the way. I think it’s [a] really, really exciting time.

We’ve had our first two patients participate here. All has gone smoothly, I have to say. It’s probably the most exciting thing that I’ve been part of because this is something I’ve been reading about for 10-plus years. To finally see it come about and be able to offer patients a treatment like this is incredibly exciting.

The main thing I would caution patients [about] if they went through their primary care provider is that genetic counseling is really an integral part of this.

What is the process of getting tested for Lynch syndrome?

There are multiple ways these days and I think that’s ultimately a good thing.

It used to be that you had to come to a center like Fox Chase. You had to go through what we call the clinic-based, high-risk program. Sometimes those programs would have a long wait to get in. That’s still an option for patients and I think that’s a good option.

I firmly believe that patients who are having this kind of testing need to have genetic counseling. What’s nice in 2023 is there are more ways to go about that.

Patients can get testing through their primary care providers. Providers may have some access to genetic counseling remotely or sometimes the genetic testing companies they’re using may have their own counselors.

The main thing I would caution patients [about] if they went through their primary care provider is that genetic counseling is really an integral part of this.

The other way is what we call direct-to-consumer where patients can go online. There is a company where the company has its own online doctor. There’s online counseling and they can send patients a kit. It’s not my preference for patients, especially patients who may have concerns or may have lower health literacy [and] need more help with the decision-making process.

But, again, I do think that option has a place for patients who may be otherwise reluctant to come through a big cancer center or may have concerns. It allows patients to do the testing outside of their health insurance. There are, again, pluses and minuses to it, but I think it has a place. All of those exist for patients as ways to get tested.

Is there a risk in panel-based testing?

There are many different companies that offer different variations on the same theme, which is generally panel-based testing where you can get tested for a bunch of different genes all at once, including the Lynch syndrome genes, to identify any risks that may be in the family.

There are some panels that are over 100 genes but that’s not actually the right answer for every patient. When you do a large panel, you have a high chance that you may find uncertain results in the Lynch genes or other genes that you don’t really know the answers to.

You may also find what we call incidental findings. You may be thinking, “My brother had colon cancer at 40 so he has a pretty high chance that there’s Lynch syndrome. I want to get tested for that.” What if you, lo and behold, find a BRCA mutation? That can be pretty unsettling for some people and, again, why counseling is so important.

There needs to be a bit of a “buyer beware.” You need to know the pros and cons of that approach. It’s not infrequent that when we’re discussing our cases weekly with my counseling team, there will be patients who come along who just want to keep their testing simple.

They don’t want the 50- or the 100-gene panel. They just want to focus on either 12 breast cancer or colon cancer genes because they don’t want all of that risk of distracting information. It’s important for people to understand that they do have those choices before they jump into this.

This is something that has been amazing for me in medicine [since] when I started. We would counsel basically one gene at a time. We had women with breast cancer who we might counsel for an hour and a half to just BRCA1 and 2.

Now, only 15 years later, we’re doing this much broader pre-counseling for patients. But we really then focus on the results counseling afterward, especially when patients are getting panels of 80-plus genes, you couldn’t possibly counsel for every gene individually so it’s really fascinating how it’s changed.

When you do a large panel, you have a high chance that you may find uncertain results in the Lynch genes or other genes that you don’t really know the answers to.

What is ICD-10?

ICD-10 is the new coding system. It does separate out Lynch syndrome a little bit more so now there’s a code for MLH1 & MSH2, so each of the genes. I use them, but there is also a general Lynch syndrome code as well.

When I’m having an interaction with a patient, doing some counseling, or bringing someone in to review testing results, I will include that code.

Unfortunately, some of the ICD-10 codes that will help docs get reimbursed for high-risk syndromes are not high-capture codes like a colon cancer diagnostic code. They are lower capture V codes that, for the doc, may mean minimal to no reimbursement.

This is one of the challenges in the field. Again, our health system is very much structured around spending a lot of money on treating complex diagnoses and not spending much money at all on preventing disease.

Hopefully, one day, we’ll see that the amount that a provider gets for spending time with someone to test them for Lynch syndrome, to counsel them correctly, to help them understand what they can do about that risk should be reimbursed as well as treating cancer down the line or at least some parity in those two.

Conclusion

One of the hardest things about genetics for patients is these intrinsic fears that they’re discriminated against. Understanding it all can be hard. Sometimes their doctors don’t even understand it all that well.

It really has been pretty amazing to be part of it all. Part of the joy of being in research medicine is some of the amazing colleagues you meet along the way. Being part of this mission to understand this disease better, help the patients, see them at meetings, and learn about this is really, really pretty amazing stuff.