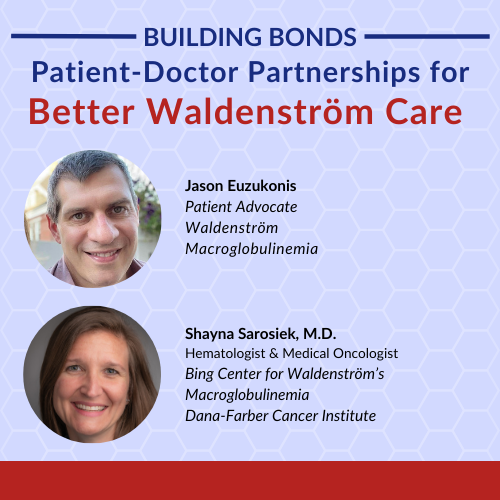

Building Bonds Episode 1: Patient-Doctor Partnerships for Better Waldenström Care

The relationship between a patient and their doctor can make all the difference. A strong partnership leads to more informed decisions, personalized care, and a greater sense of control. Dr. Shayna Sarosiek, an expert in Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and patient advocate Jason Euzukonis discuss what makes their patient-doctor teamwork truly effective.

Learn how to build trust and open communication with your healthcare team. Understand the role of shared decision-making in Waldenström treatment. Hear first-hand experiences of navigating chronic cancer with your doctor by your side. Discover practical tips for advocating for yourself or a loved one in the treatment process. Explore how teamwork fosters a supportive environment for long-term care.

We would also like to thank The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and the International Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation for their partnerships.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

- Introduction

- Jason’s Initial Diagnosis

- Doing Research & Asking Questions

- Patient Demographics

- Navigating Your Way to a Specialist

- Decentralized Care

- Your Doctors, Your Decision

- How the Right Care Impacts Mental Health

- Approaches to Care from a Doctor’s Perspective

- Approach with Different Kinds of Patients

- Taking Back Control of Your Care

- Navigating Conversations Between the Patient and the Physician

- Understanding Waldenström’s Treatment Options

- Addressing Side Effects

- Patient-Physician Relationships

- Waldenström’s Clinical Trials

- Conclusion

Introduction

Tiffany Drummond, Patient Advocate

Tiffany Drummond: I have worked in cancer research for 20 years, but more importantly, I became a care partner and advocate when my mom was diagnosed with endometrial cancer in 2014. Her journey led me on a quest to find out as much information as I could to help with her care. Quite honestly, it wasn’t easy to find and that’s why we at The Patient Story put on programs to help people navigate life after diagnosis.

This program is hosted by The Patient Story, a multi-platform organization that aims to help people navigate life before and after diagnosis in human terms through in-depth patient stories and educational discussions, focused on how patients and care partners can best communicate with their doctors as they go from diagnosis through treatment in Waldenström’s.

We want to thank The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society for its partnership. The LLS offers incredible free resources, like their Information Specialists who can help you communicate with members of your healthcare team and provide information about treatment options.

We also thank IWMF (International Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation), an organization specifically dedicated to Waldenström’s patients and care partners. They also offer free resources, including over 60 in-person support groups worldwide.

The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content. While we hope this is helpful, please keep in mind that this program is not a substitute for medical advice.

Stephanie, The Patient Story founder and a blood cancer survivor herself, will lead this conversation. But first, we start with Waldenström’s patient voice, Jason.

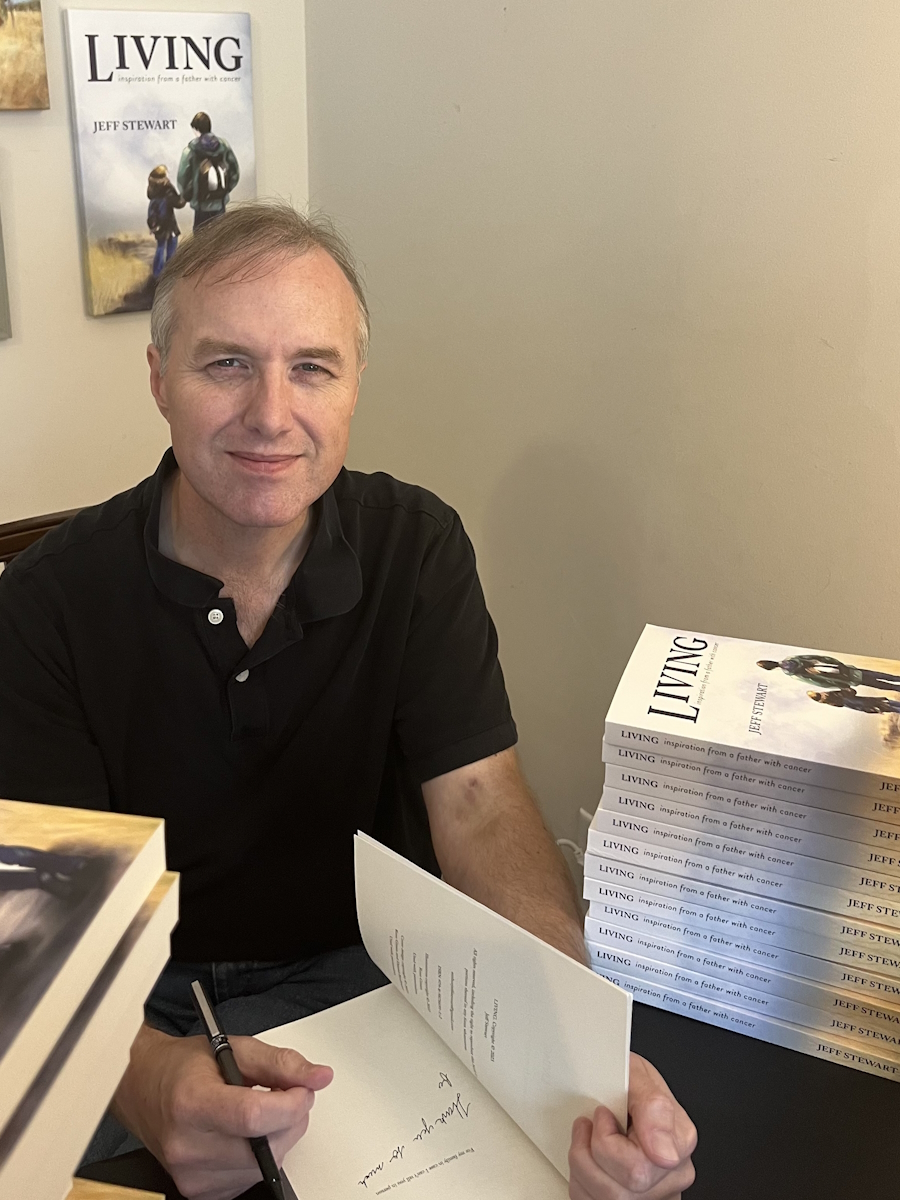

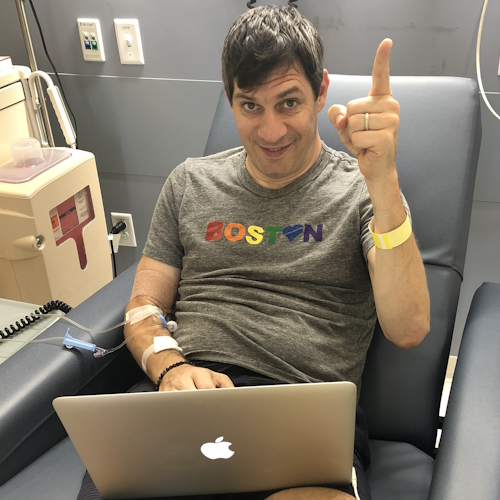

Jason Euzukonis, Patient Advocate

Jason Euzukonis: My name is Jason. I recently turned 50 years old.

I’m married and have two children who are 13 and 10. I live on the North Shore of Massachusetts. I’m an avid runner and a sales rep in the athletic footwear industry, and I was diagnosed with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia in June 2018.

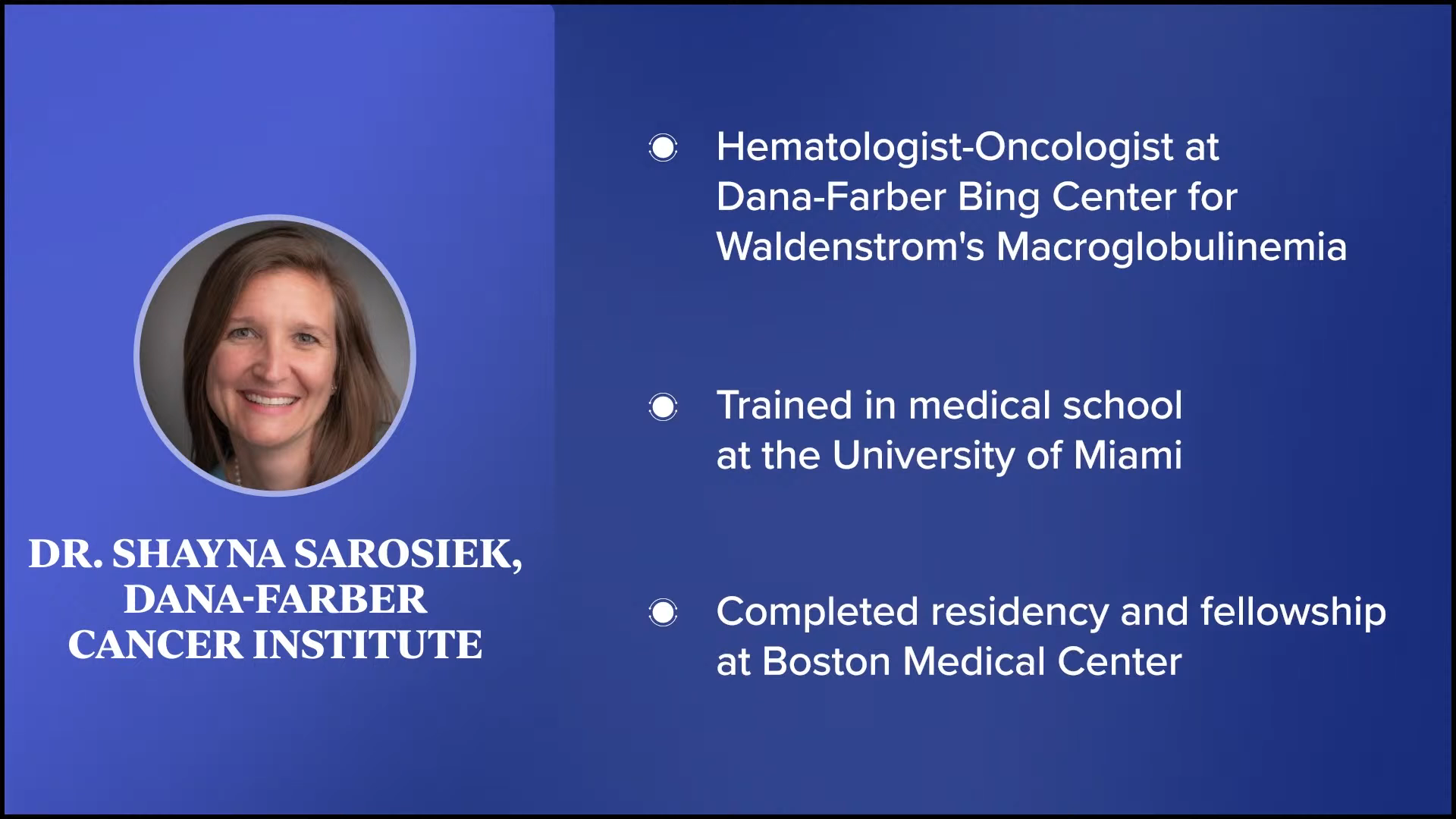

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek, Hematologist-Oncologist

Stephanie Chuang: Dr. Shayna Sarosiek is someone whom we’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with before and have heard so many great things about. Dr. Sarosiek, can you tell us about who you are, what you do, and what drew you to this specialty?

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek: I’m a hematologist-oncologist. I work at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at The Bing Center for Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia (WM). I went to medical school at the University of Miami and then did my residency and fellowship at the Boston Medical Center.

Jason’s Initial Diagnosis

Stephanie: We hear about shared treatment decision-making, being an empowered patient, or self-advocacy, and sometimes that concept can get a little bit lost in the mix. There’s a lot of conversation without specific examples. Our goal is to showcase not the only kind of communication and the relationship that can happen between a physician and a patient but also to showcase what a great relationship looks like.

Jason and Dr. Sarosiek have a great relationship and a lot of that is centered on communication and long-term relationship building. Having said that, Jason, what were the signs that something wasn’t right and who was the first physician you went to see?

Jason: I’m a runner and I know my body well. In the spring of 2018, I noticed signs that something wasn’t right. I can go for a run and feel tired but still slog through a few miles, but I started feeling some fatigue that felt off. Three or four minutes into the run, I would feel like my body was shutting down. It felt like blood and oxygen weren’t getting to my muscles.

After I learned my diagnosis, it turned out that’s exactly what was happening. It led me down the path of trying to figure out what was going on. I went to my primary care physician then to a hematologist then to a general lymphoma specialist. I went through multiple steps before I ended up at Dana-Farber with a team that specialized in my subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Primary care physicians are not cancer specialists.

Stephanie Chuang

Stephanie: I want to dive into some of this because I think different parts of your story will resonate with different people. As we know, primary care physicians are not cancer specialists. Yours ordered blood work and saw something was wrong, but your self-advocacy started pretty quickly. Can you describe that?

Jason: The primary care physician was able to identify that something wasn’t right. I was very anemic and they had me come in within a day or two to make sure blood counts weren’t crashing in case there was some internal bleeding, in which case I would have needed to go to the emergency room. Things seemed stable, even though my blood counts were low, and that’s when they kicked me over to the hematologist.

I started doing more research and realized that I needed someone who knew the disease.

Jason Euzukonis

As I look back, there’s certainly a role for hematologists, but even then, especially for my situation with a rare type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, you want to go to another level. That’s when I started doing more research and realized that I needed someone who knew the disease.

There were some things that the hematologist said that jumped out at me. When they were talking about treatment, they said, “We treat all these tough types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma the same way with chemotherapy.” I thought that didn’t sound right. I was fortunate that I knew someone who worked in a lab at another medical center in Boston and that’s when we started taking a deeper dive and getting the true diagnosis of Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia.

This is why I think it’s important for a patient to continue doing research. They were great over there, but during that time, if you search Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, it’s not going to be too hard to find The Bing Center at Dana-Farber.

When I realized that there was a team there that truly specialized in my cancer, that’s when the real journey began of getting over to that team. I felt like the more I could work with doctors who truly know this disease inside and out, the better my chances of living a normal lifespan.

Doing Research & Asking Questions

Stephanie: Jason, you mentioned in a previous conversation that you love research. I was a professional journalist and a research geek myself. When I became a patient, I felt very self-conscious about being labeled as a problematic patient, which I defined as asking too many questions. Did you have to get over any hump like that, even though that’s your nature to ask questions, to want to know? Do you have guidance for those who have less of an affinity for asking questions or wanting to take up that space?

Jason: I didn’t have a problem getting over that. My life was on the line. I’m naturally curious anyway and when I get on top of certain topics, I like to take a deep dive and learn as much as I can, but I don’t have a problem asking questions.

That said, I know there are patients for whom that can be challenging. We’ve had to deal with that in our own family where an older relative got a difficult diagnosis. Their generation tends to be a little bit shyer about questioning the doctor, but I think good doctors have no problem with patients asking questions and probably prefer that.

Get your family or friends involved because there’s likely someone who will take the bull by the horns. Let them know the situation because there likely is somebody who will be more familiar with what to do and what questions to ask.

I’m naturally curious anyway and when I get on top of certain topics, I like to take a deep dive and learn as much as I can

Jason Euzukonis

Patient Demographics

Stephanie: Dr. Sarosiek, can you describe how many years you’ve been focused on Waldenström’s and how many patients you see on average?

Dr. Sarosiek: I’ve been focusing on Waldenström’s for about four years now since I came over to Dana-Farber. It varies a little bit, but I see about 30 to 40 patients a week and the vast majority of them have Waldenström. A few of those patients might be patients with a precursor to Waldenström called MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance) or related disorders.

Navigating Your Way to a Specialist

Stephanie: You’re seeing 30 to 40 patients a week, the majority of them have Waldenström’s, some of them with MGUS. Whereas in the community, hematologist-oncologists are seeing everybody across the board, so they may only see one or two Waldenström’s patients a year.

Similar to Jason’s trajectory, most people are probably going to see a community provider and then end up with someone like yourself. Dr. Sarosiek, what is your guidance to people on how to get to a specialist and the importance of that?

Dr. Sarosiek: Because of what I do, it’s important to get to a specialist in whatever way you can. If you’re able to and have the means to see a specialist, that’s the best because you can have one-on-one dedicated time.

There are other ways of getting a specialist’s opinion. If you’re unable to travel, Dana-Farber offers grand rounds where you can send in your records and physicians can review them.

I give patients as much time as I can to dig deep into their disease knowing that it’s not possible in the community to specialize in Waldenström’s.

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek

Some employers have second opinion programs and it’s a good idea for patients to look into that. The employer provides the ability to give your records and a physician can give a second opinion. Those physicians are typically at large academic centers that specialize in the disease. You can also access some opinions of physicians as well through some support groups. It wouldn’t be exactly for your case, but it might be a way for the patient to inform themselves and learn a little bit.

But if possible, seeing a specialist is a good idea. Having practiced for a few years before I came to Dana-Farber, I saw a handful of Waldenström’s patients a year. I never could have known all the literature that there was to know about Waldenström’s then or any other particular disease. If you’re able to see a specialist, they might be able to better tailor your care around all of the literature on that one disease.

The other part that I try to do with my patients—and hopefully I’m okay at it—is to recognize that when patients come to see me, typically they’re seeing their local doctors who are excellent physicians but don’t know all the details. I give patients as much time as I can to dig deep into their disease knowing that it’s not possible in the community to specialize in Waldenström’s.

Decentralized Care

Stephanie: Many people hear, “Go see a specialist,” but logistically speaking, that might seem daunting for some people, especially if this is something that they’re going to have to be minding for a long while. How does that work? Do they have to travel every single time? Do you have relationships where patients see you as the specialist, but they’re getting their blood draws and some of the routine care closer to home?

Dr. Sarosiek: We have a lot of cases where patients do what works best for them. Patients who live nearby can travel to see us. We have an ongoing relationship with routine care and routine blood work at our center. But a lot of our patients can’t travel, so they have a local oncologist who we’re willing to work closely with and they can have their routine follow-up there.

Patients will see us once a year and then for the rest of the year, we remain available to them for questions or concerns. Sometimes we might do an initial consult and then tell the patient if something comes up in the future, now that we have a little bit of their background, their local oncologist can reach out to us with questions or concerns or they can come back if and when they have to make a big treatment decision. We can tailor it to what works best for the patients in terms of their ability to visit our center.

Stephanie: That’s wonderful. It sounds like you are as flexible as you possibly can to meet the different situations that patients and care partners have.

My gut was telling me that there should be more discussion between the patient and the doctor.

Jason Euzukonis

Your Doctors, Your Decision

Stephanie: Jason, the first place you were at, you were there for a year before you went to Dana-Farber and saw Dr. Sarosiek. Could you describe what the difference was between where you were before and Dr. Sarosiek?

Jason: With the doctor I was seeing before, there wasn’t as much back and forth in terms of decision-making. It was here’s what we’re going to do and that’s that. I felt like I didn’t know if that was the right approach. My gut was telling me that there should be more discussion between the patient and the doctor.

By the time I got to Dana-Farber, which was about a year after my diagnosis, I couldn’t believe the difference. At my first appointment, I worked briefly with another doctor before Dr. Sarosiek and that doctor was phenomenal. I remember him sitting back and saying, “What questions do you have?” He took more time than any other doctor I’d ever met with before and that seems to be the case with the whole team at Dana-Farber.

That’s something important for all patients to remember. If you feel like you’re getting rushed, if you feel like there’s not a good discussion with your doctor, then you might want to see if there are other options. It was just such a big difference not just between Dana-Farber and that one hospital, but also almost with any other doctor I’ve met with before.

How the Right Care Impacts Mental Health

Stephanie: Mental health is a huge part of every diagnosis, but because this is long-term, it’s a huge part of the consideration. Can you describe the daily impact and what shifted for you after you moved to Dana-Farber?

Jason: In that first year after my diagnosis, I had a massive amount of anxiety. I woke up every morning and I could feel it in my chest. I had to spend a good solid half hour in quiet meditation every day. Fortunately, I’m an early riser, so I’m up before the family and I get that moment of quiet.

Meditation was huge for me. Whether people believe that works or not, the point is to find things to help you get through your day. At the end of the day, we have to get used to living a long time with this cancer and at some point, once you start to feel better, you’ve got to get back to your routine in terms of work and, in my case, raising a young family.

A cancer diagnosis can feel very lonely and being around others who are going through something similar is helpful.

Jason Euzukonis

I felt like I lost control of my health, so I was trying to do whatever I could to reclaim that control. I changed the way I eat. I was able to get back to exercise. It doesn’t have to be an intense form of exercise. It’s simply moving, like going for a walk or gardening. It’s helpful that those were the things that I did.

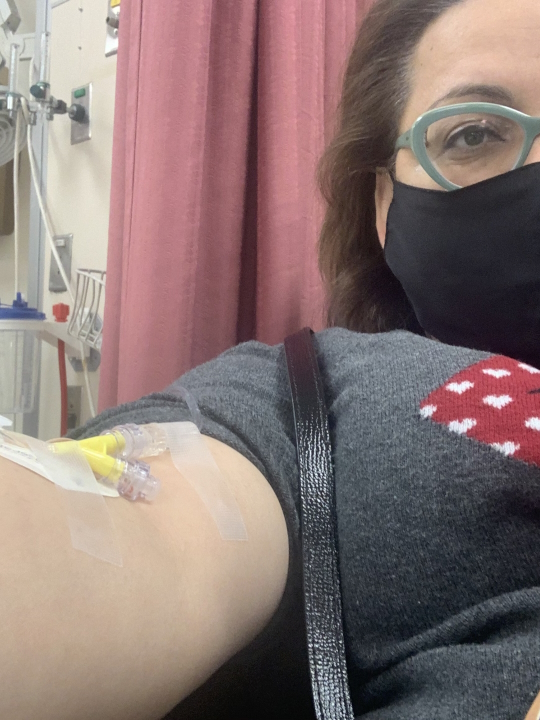

Support groups are a critical component in moving forward with your mental health. There are a lot of people who have been through some difficult journeys in those groups. You can learn a lot. If you’re dealing with something, there’s a good chance that somebody else in that support group has been dealing with the same thing at some point. Another great way to help with your mental health is to talk to others who are on the same journey. A cancer diagnosis can feel very lonely and being around others who are going through something similar is helpful.

Stephanie: Absolutely. I know you lead a couple of support groups for the IWMF, so thank you for highlighting that.

It’s a journey for patients as they get used to living with this disease and restructuring their lives around the disease. I have to change a little bit of who I am for the patients depending on where they are in that journey.

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek

Approaches to Care from a Doctor’s Perspective

Stephanie: Dr. Sarosiek, hearing Jason’s journey to you, how often do you see patients who are in a very similar space where they’ve been told what to do? What are you noticing from the patients you’re seeing and how do you approach them when you first meet them?

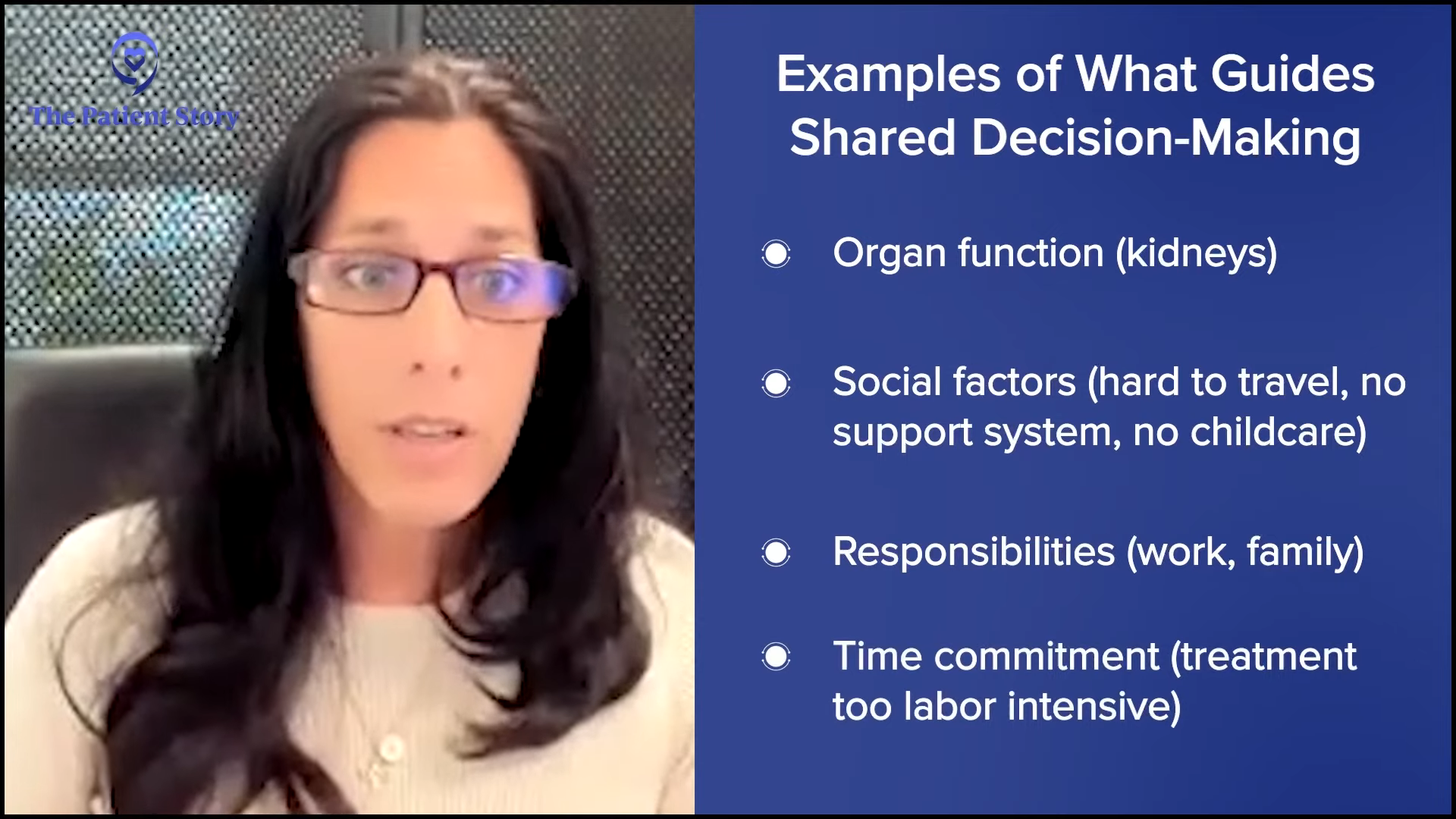

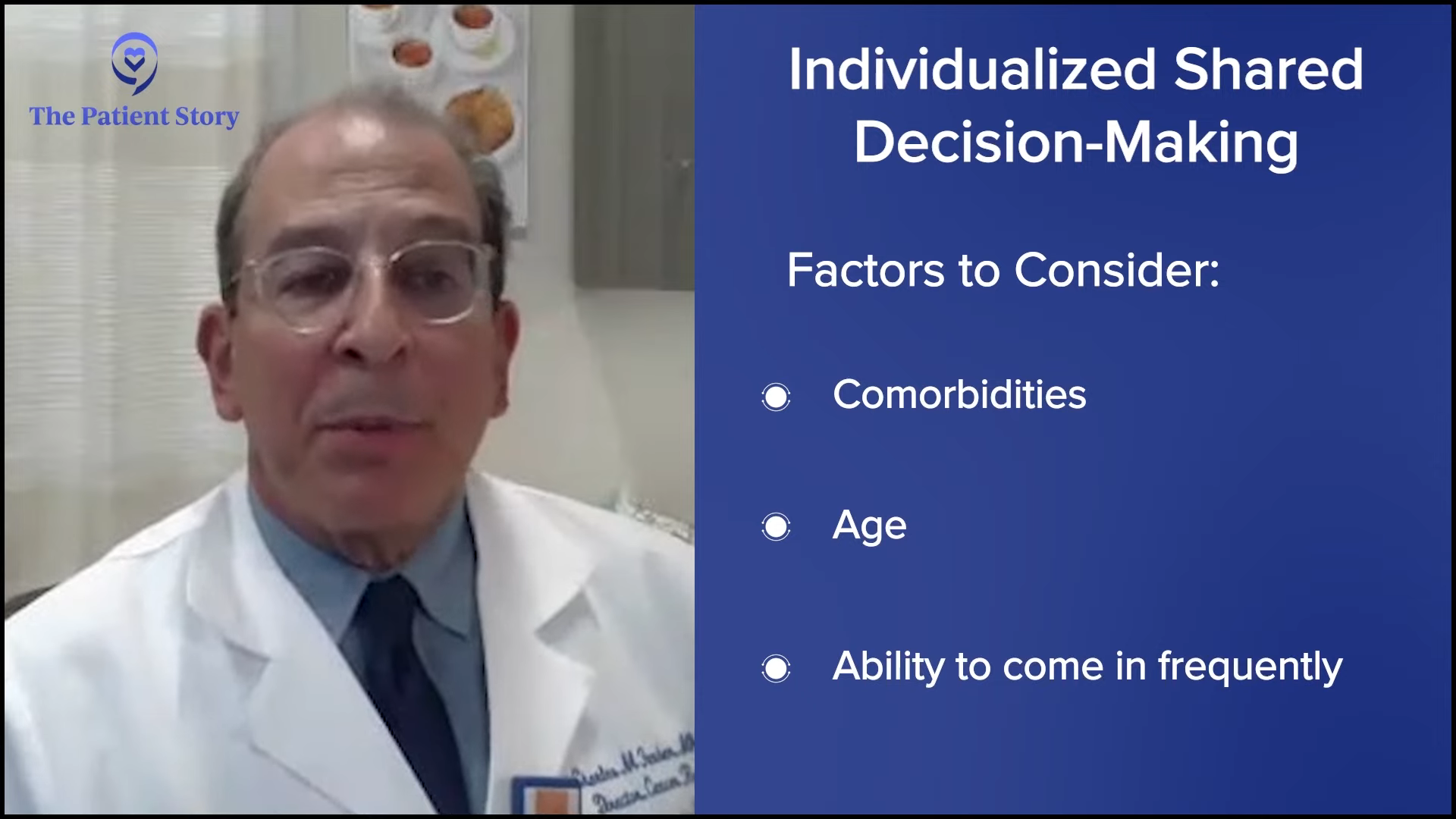

Dr. Sarosiek: Patients will see me and say, “What would you do for my treatment? This is what I was told I have to do.” Luckily with Waldenström’s, we often have quite a few options. I lay out the options and some patients don’t know that they have other options and that’s an important part of seeing a specialist.

The longer I’ve been in Waldenström’s, the more I learn that a lot of patients face something similar to Jason. I can’t speak to this personally, but patients come to see me initially around the time of diagnosis and it’s an everyday, day-in, day-out thing where they’re thinking about the disease and worrying about the future.

It’s a journey for patients as they get used to living with this disease and restructuring their lives around the disease. I have to change a little bit of who I am for the patients depending on where they are in that journey. Initially, patients will have a lot of questions and a lot of anxieties. I even tell them that this is a time when you ask questions because relieving your anxiety or getting questions answered is important right now.

At one point, they’re going to learn to live with this and feel more relaxed, and it’s not going to be the only thing on the front of your mind all the time. I try to adjust to patients as they work their way through because it’s life-changing, but it also changes during the time that they’re living with the disease as well.

Approach with Different Kinds of Patients

Stephanie: You see different kinds of people with different personalities and preferences. I know that there’s so much more depth to this, but could you generalize the different kinds of patients and care partners who walk through the door? Jason is very research-oriented and has no problem asking questions. How about the other kinds of people who are not the same? What’s your guidance to them on how to approach a Waldenström’s diagnosis?

Dr. Sarosiek: That’s something that I try to feel out during an appointment. Who am I meeting with and what works best for them? Many of our patients who come to Dana-Farber for a second opinion tend to ask more questions and want more information. But as I talk to the patients in the first few minutes, some patients are overwhelmed by a lot of information, especially in the beginning. I try to tailor what I’m saying or what I’m offering in that first appointment in terms of information.

Then you might have someone who wants to learn more after they get over the initial shock or anxiety about the diagnosis. Sometimes after I give them the options, patients want more guidance from me rather than leaving the decision up to them. There are a lot of different people and a lot of different personalities and I try to feel that out, so hopefully I can best serve the patient in a way that would make them most comfortable with their disease.

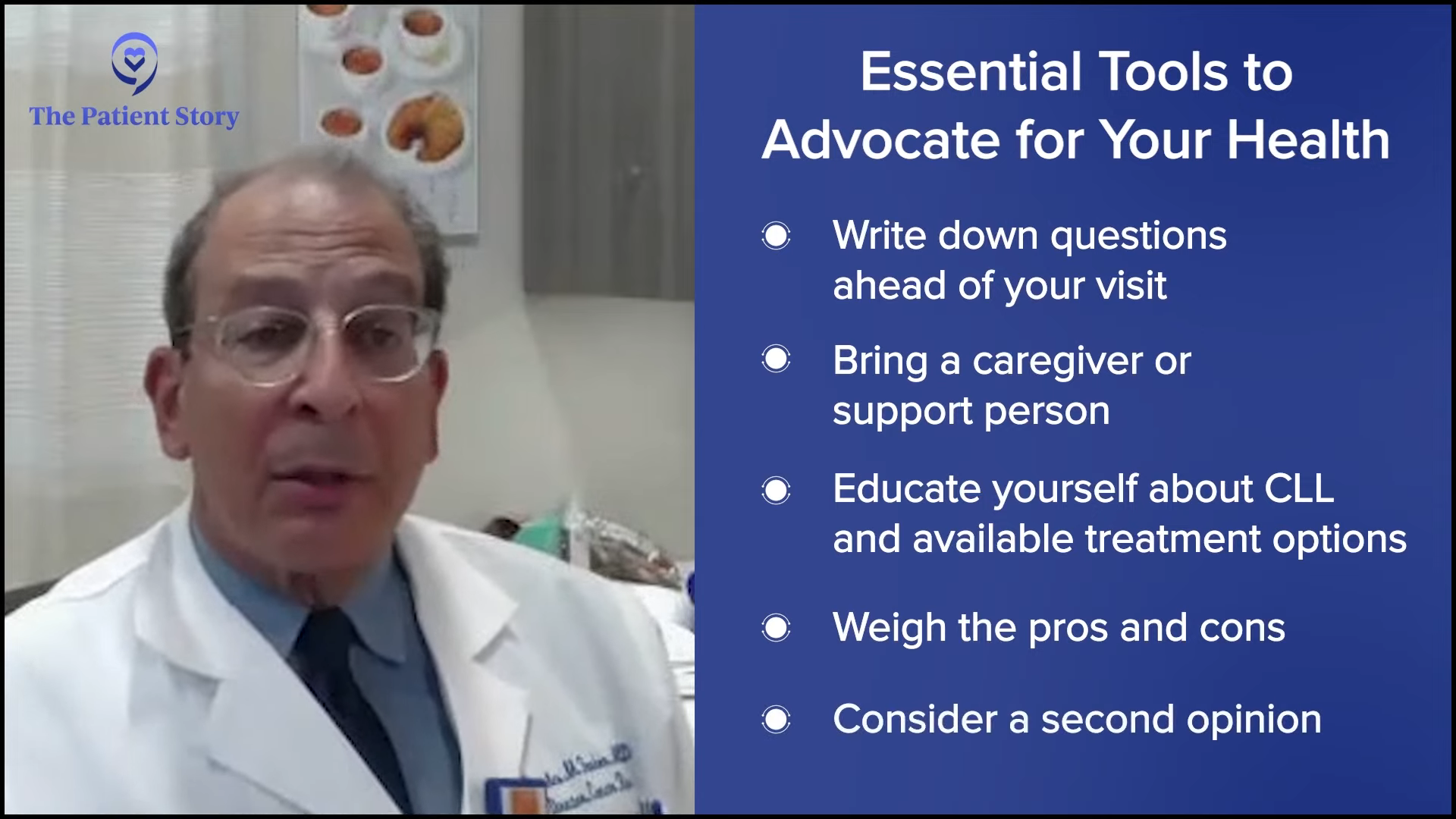

Stephanie: Are there top questions you recommend that patients should ask their doctor after a Waldenström’s diagnosis that would be pretty key in helping them understand the disease and how the care is going to follow?

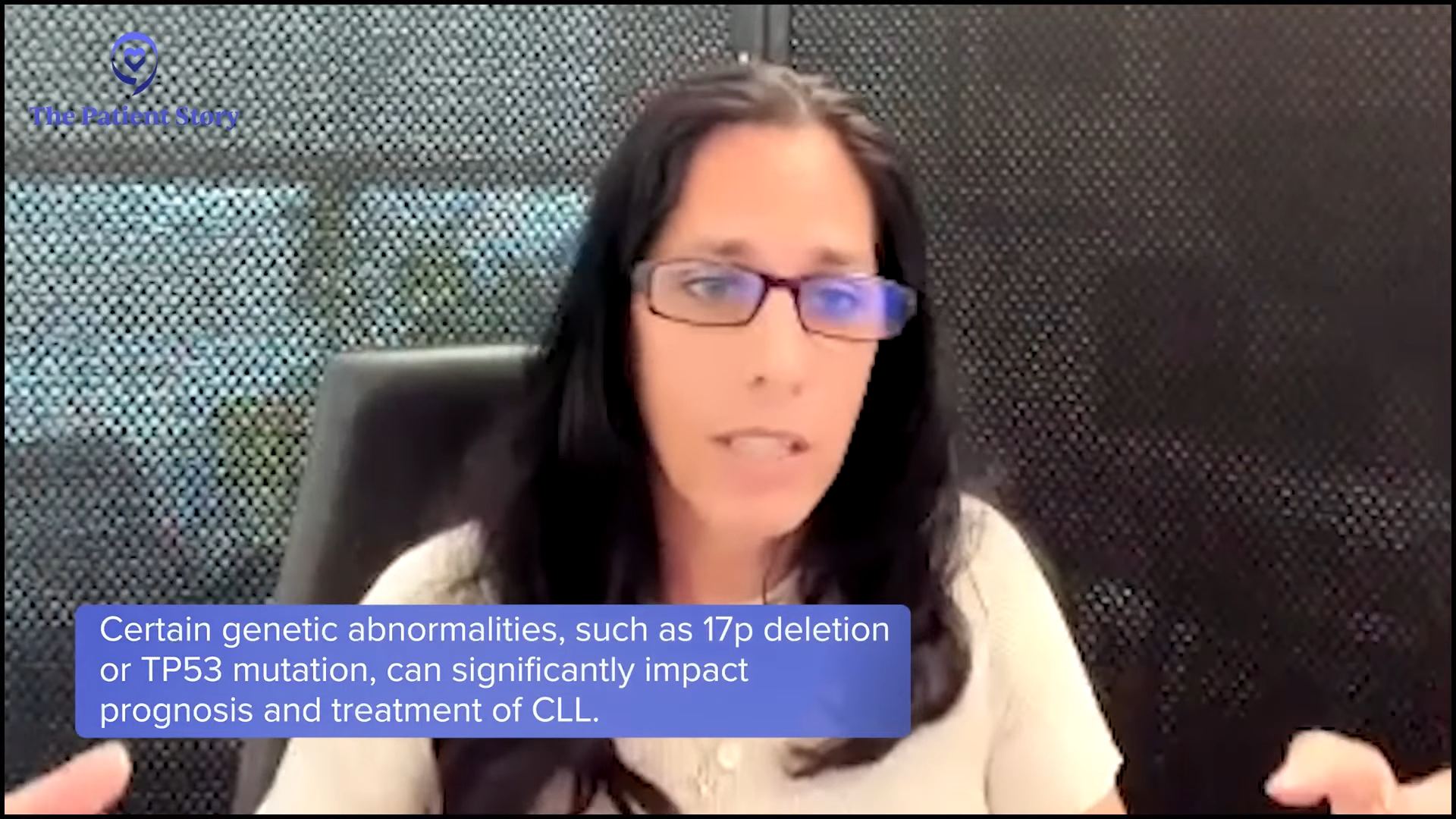

Dr. Sarosiek: A lot of patients want to confirm if they have the right diagnosis. Most of the time, they do but occasionally, that’s not the case. Part of what we do in that initial visit is walking through to confirm that a patient has Waldenström’s. No one wants to hear that they have cancer, but sometimes that helps patients to understand that this is the cancer that they have and they can move forward without having doubts.

It’s important to ask what treatment options are available. They should ask, “Are there other things that I could consider as my options? Are there alternatives?” Most cancers do; not all of them, but most have multiple options for treatment.

Knowing the key markers to watch closely empowers the patient to know what’s going on with their disease.

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek

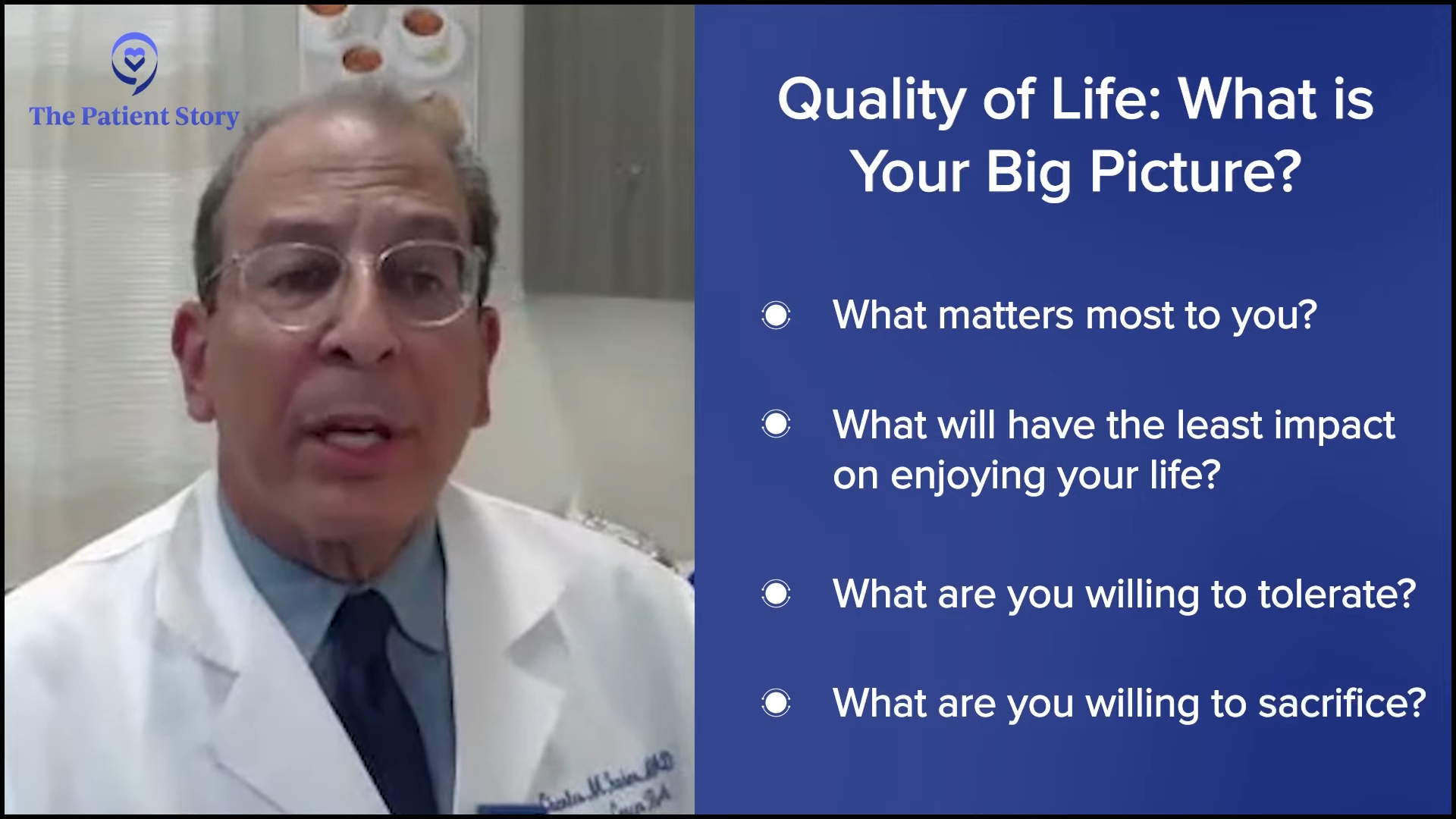

Patients should ask about the differences in the treatments and that depends on the patient’s goals. What are the differences in side effects? How long am I going to be on treatment? The patient can help tailor their treatment to what their goals are in life.

Another key question is, “What do I need to look at going forward? What are the most important markers?” With Waldenström’s, we watch their IgM level and we watch for anemia. That’s another key thing that often helps patients to feel a sense of control if they know exactly when they should be following up and what they should be looking for. We always check labs and a hundred values will come up on any patient portal for any visit, but knowing the key markers to watch closely empowers the patient to know what’s going on with their disease.

You have a certain amount of time with a doctor and it’s a matter of being more upfront and telling them if you’re not comfortable with where things are at with the relationship.

Jason Euzukonis

Taking Back Control of Your Care

Stephanie: I’ve heard control come up a couple of times and that resonates with me as well, the sense of how to regain control. Like you said Dr. Sarosiek, some people are clearly overwhelmed and you recognize that they may not be able to or want to hear and digest a ton of information, so you tailor the conversation to them. What is your recommendation on anything else that can help them in the beginning? Jason, when you had some problems feeling heard or feeling like an actual participant and partner in the conversation, what is your recommendation?

Jason: In retrospect, with the doctor who I saw before I got to Dana-Farber, I probably should have been more upfront and said, “I’d like you to hear me out a little bit more. Are you okay with me asking more questions?” Because I think a lot of people have a hard time getting past that hurdle. I wish I would’ve been more upfront because for all I know, maybe they were more open to a back-and-forth.

The challenge that the doctor ran into was that particular center was overwhelmed. The healthcare system was very taxed. It was one patient after another and it felt like they didn’t have the time. I don’t think that was the fault of the doctor. But at the end of the day, it’s your life. You have a certain amount of time with a doctor and it’s a matter of being more upfront and telling them if you’re not comfortable with where things are at with the relationship.

Ask your physician, ‘What’s the best way for me to ask questions?’… You need to have a comfortable way to reach out to your provider and be able to ask those questions.

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek

Stephanie: Thank you for pointing that out. It’s true. The systems are quite inundated, unfortunately, and time is the biggest resource that is unavailable. Dr. Sarosiek, do you have anything to add?

Dr. Sarosiek: As a physician, I agree that there are a lot of time constraints in terms of seeing patients and other responsibilities. You could ask your physician, “What’s the best way for me to ask questions?” Maybe there isn’t enough time in that initial appointment or they have a full schedule.

They may say, “You can reach out to me through the patient portal or talk to my nurse who’s an excellent resource.” Some patients email and if they’re comfortable with that, that’s another avenue. You have to see with your physician the best way that they feel comfortable and a way that you feel comfortable communicating. If you can’t get all of that done in a clinic appointment, then is there another way? Because that’s a key part of the relationship.

As a physician, I feel like it’s important to be available if questions come up, particularly in the beginning when there are a lot of anxieties or questions surrounding a diagnosis. Even as time goes on, there can be things that pop up and the patient wants to know if it’s something they should worry about. You need to have a comfortable way to reach out to your provider and be able to ask those questions.

Navigating Conversations Between the Patient and the Physician

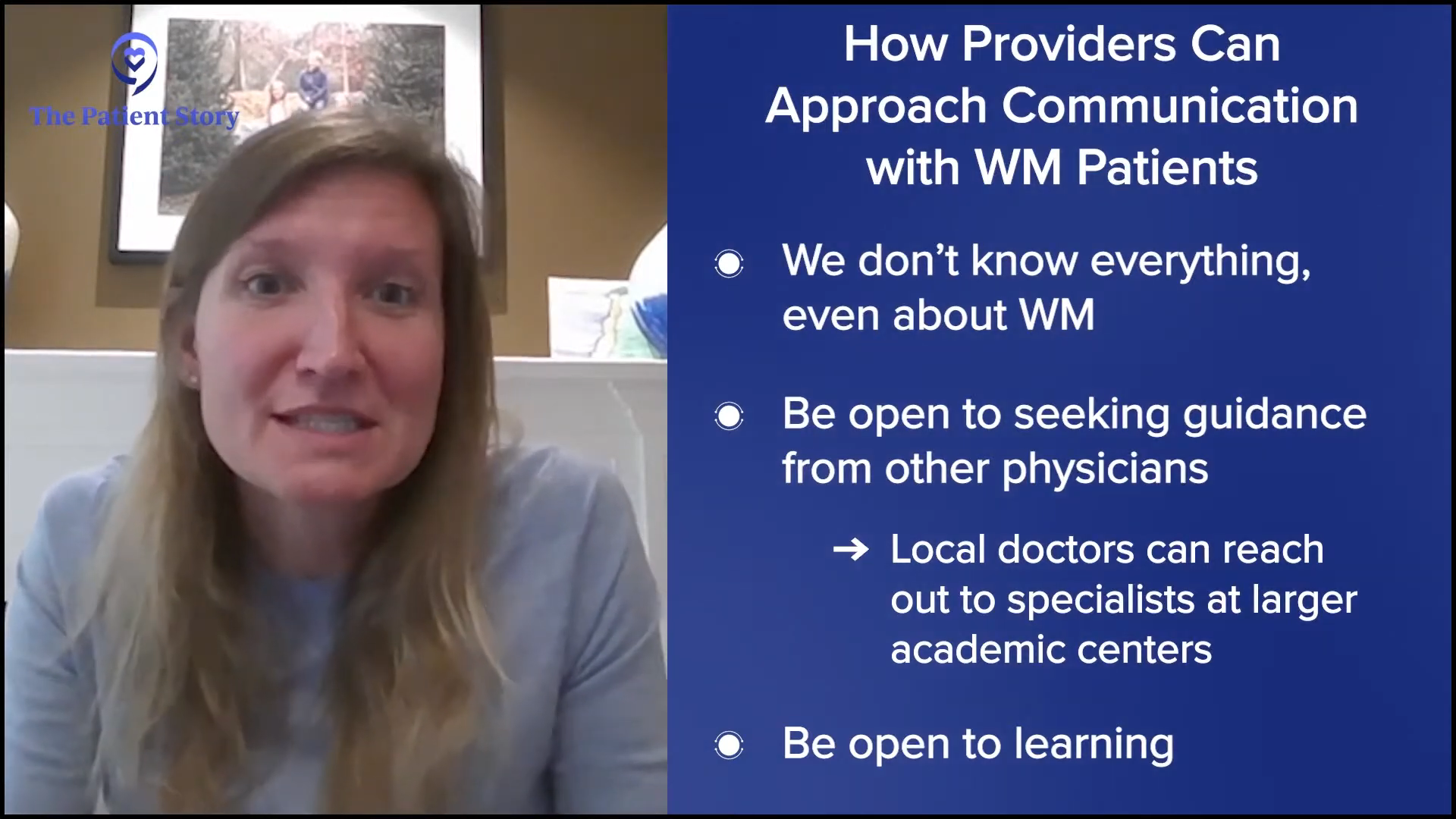

Stephanie: Dr. Sarosiek, you see so many Waldenström’s patients, family members, care partners, and caregivers. What’s your message to healthcare providers who don’t see so many Waldenström’s patients and who may not understand how to navigate the conversation? What are your top tips for them on how to navigate these conversations in the beginning?

Dr. Sarosiek: I don’t know exactly the secret to this, but I do think that as a physician, it’s important to know that we don’t know everything. I know a lot about Waldenstrom’s, but still, I don’t know everything and I certainly don’t know a lot about things outside of Waldenstrom’s. It’s important for us all to realize that we have limitations and to be open to hearing from other people.

Physicians who don’t have the expertise shouldn’t hesitate to reach out to specialists at larger academic centers and feel free to ask questions.

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek

We try to be available to other providers who might not have expertise. I usually tell my patients to tell their local doctor that I’m more than happy to answer questions and be available. Physicians who don’t have the expertise shouldn’t hesitate to reach out to specialists at larger academic centers and feel free to ask questions. People email us a lot and even if I don’t know who they are or I haven’t personally interacted with them before, we’re happy to answer questions. The goal for all of us is to provide the best care.

As a physician, it’s important to be open to learning. I do it all the time. I see patients who have other clinical questions or needs that I don’t know about, and I reach out to specialists in different fields to try to answer those questions. We all have to be open to learning and open to asking other people questions when we don’t know the answers.

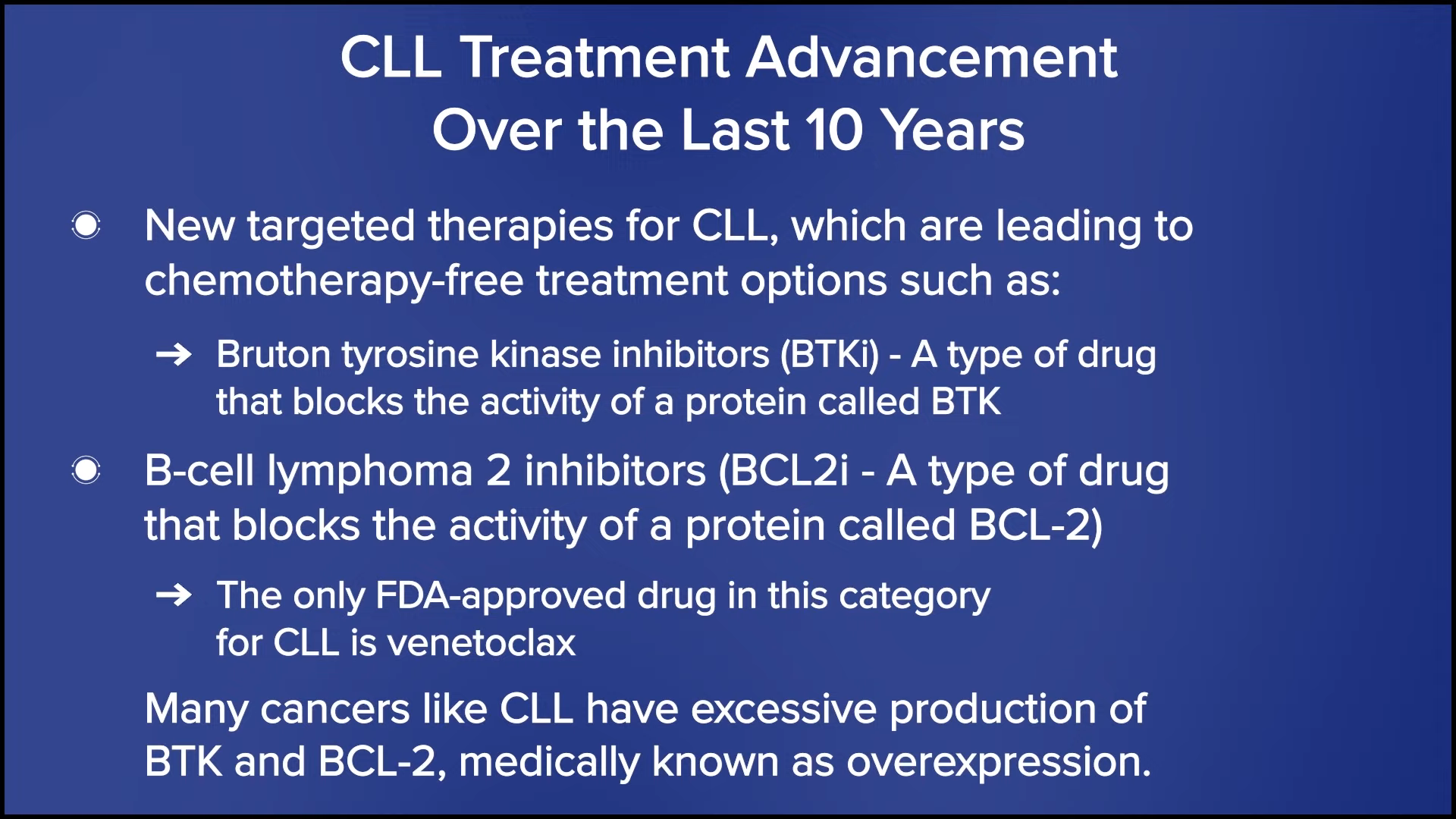

Understanding Waldenström’s Treatment Options

Stephanie: It’s a rapidly shifting landscape of treatment options in lymphomas, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including Waldenström’s, and there’s a lot of discussion we’re hoping can happen in the clinic between the physician and the patient. Jason, before you met Dr. Sarosiek, where was your mind in terms of wanting to understand treatment options and what was that first conversation like with the other physician?

Jason: That was a very difficult and very different time. I didn’t know even remotely as much as I know now, so I was still very much in the mindset of doing whatever the doctor said. As I got deeper into the journey, that’s when I realized that there were other options, but I initially pretty much did what the doctor said.

My treatment options are a tad more limited than the average Waldenström’s patient. Chemotherapy wasn’t a great option for me. In retrospect, the good news is that the previous hospital did put me on the right path, so I’m grateful for that. I didn’t know about the other options anyway and I likely would’ve started with the same option. As time went on, I got more informed and realized the right questions to ask, but I didn’t know them back then.

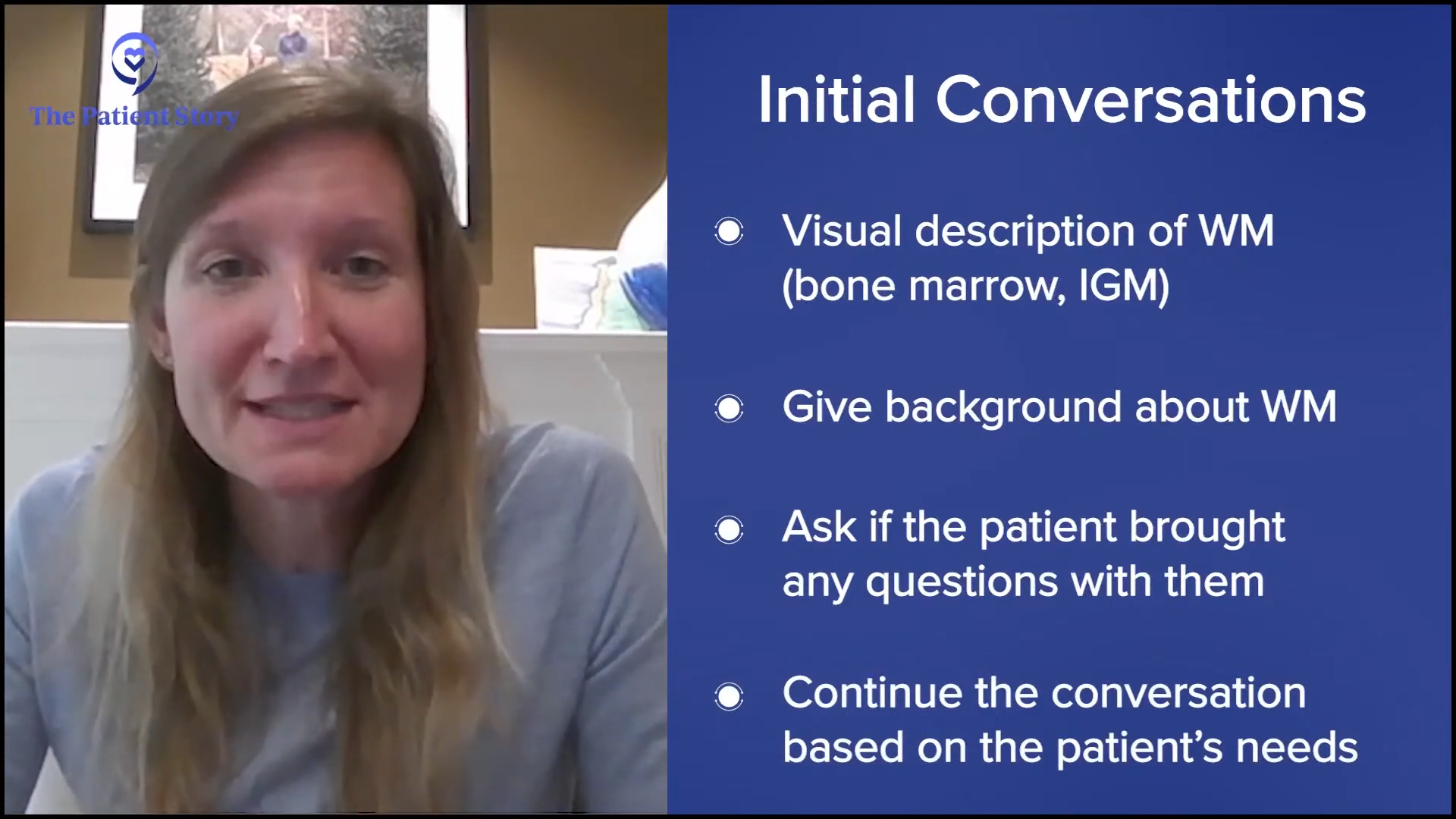

Stephanie: Dr. Sarosiek, how do you define what Waldenström’s is at the first meeting? What is top of mind for you as you try to lay out treatment options?

Dr. Sarosiek: I draw out the bone marrow and how the IgM comes out of the bone marrow. I usually try to explain it and do a little bit of a drawing because some people are more visual while other people like to hear it. I give a little background about Waldenström’s and ask what questions they have and what they want to know.

Usually, at a first appointment, patients have something that’s at the forefront of their mind or they have a list of questions. If I’m spewing out information about other things that they don’t care about before I answer the question that’s most burning, it’s not helpful. I often ask them what questions they have and that guides the conversation.

Ultimately, we often end up covering the same things at every new appointment that I have with a patient with Waldenström’s, but we might get to it in a different order or a different way, depending on what’s most important for them.

Stephanie: It sounds like during the initial meetings, you’re meeting people where they are. At what point do you lay out the treatment options? Whenever that happens, how do you lay out the options in a way that people will understand and the impact on quality of life?

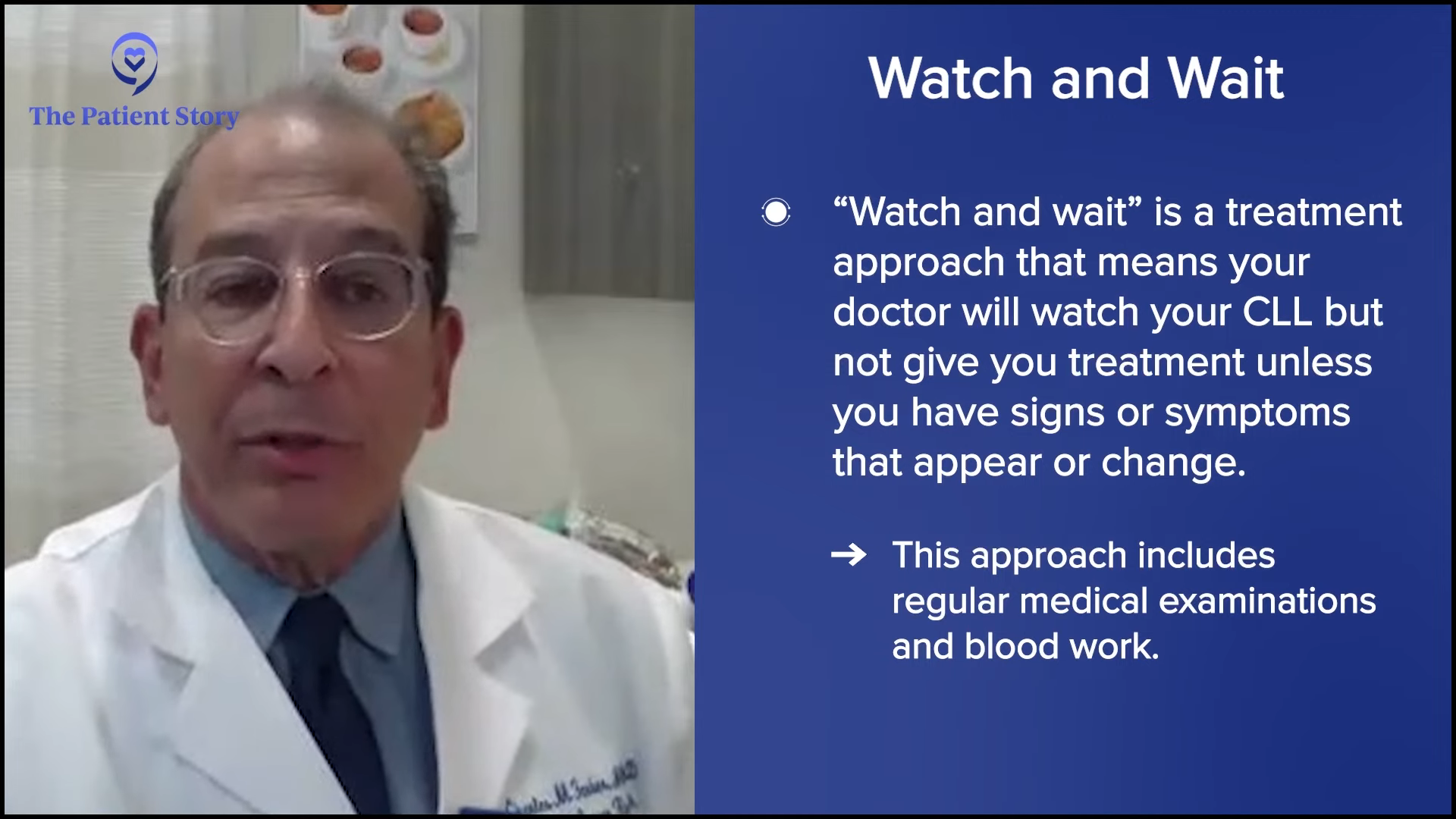

Dr. Sarosiek: There’s a small percentage of patients that need treatment immediately. For those patients, in the first conversation, we go through the diagnosis and then we jump right into treatment options.

Stephanie: What’s that profile? Why do they need treatment? How do you explain to them why they need treatment faster than other patients with Waldenström’s?

Dr. Sarosiek: A lot of our patients present similar to what Jason described. They have pretty significant anemia, their disease was brought to their attention, and they have symptoms that need to be addressed right away. In the case of Waldenström’s, the reason most patients need treatment is because of anemia. They presented to their doctor to work up the symptoms of their anemia.

Another percentage of patients will have hyperviscosity or thickened blood and that’s causing symptoms related to their Waldenström’s. In those cases, patients typically need treatment right away, so we jump into treatment discussions.

Some patients come to us because their disease was incidentally diagnosed. They had a routine blood test for their annual checkup with their primary doctor and they were noted to have high protein or very mild anemia that’s not causing any symptoms. In those cases, we have the opportunity to discuss treatment later on. We often don’t get to treatment discussion on the first visit; that comes up months or even years later.

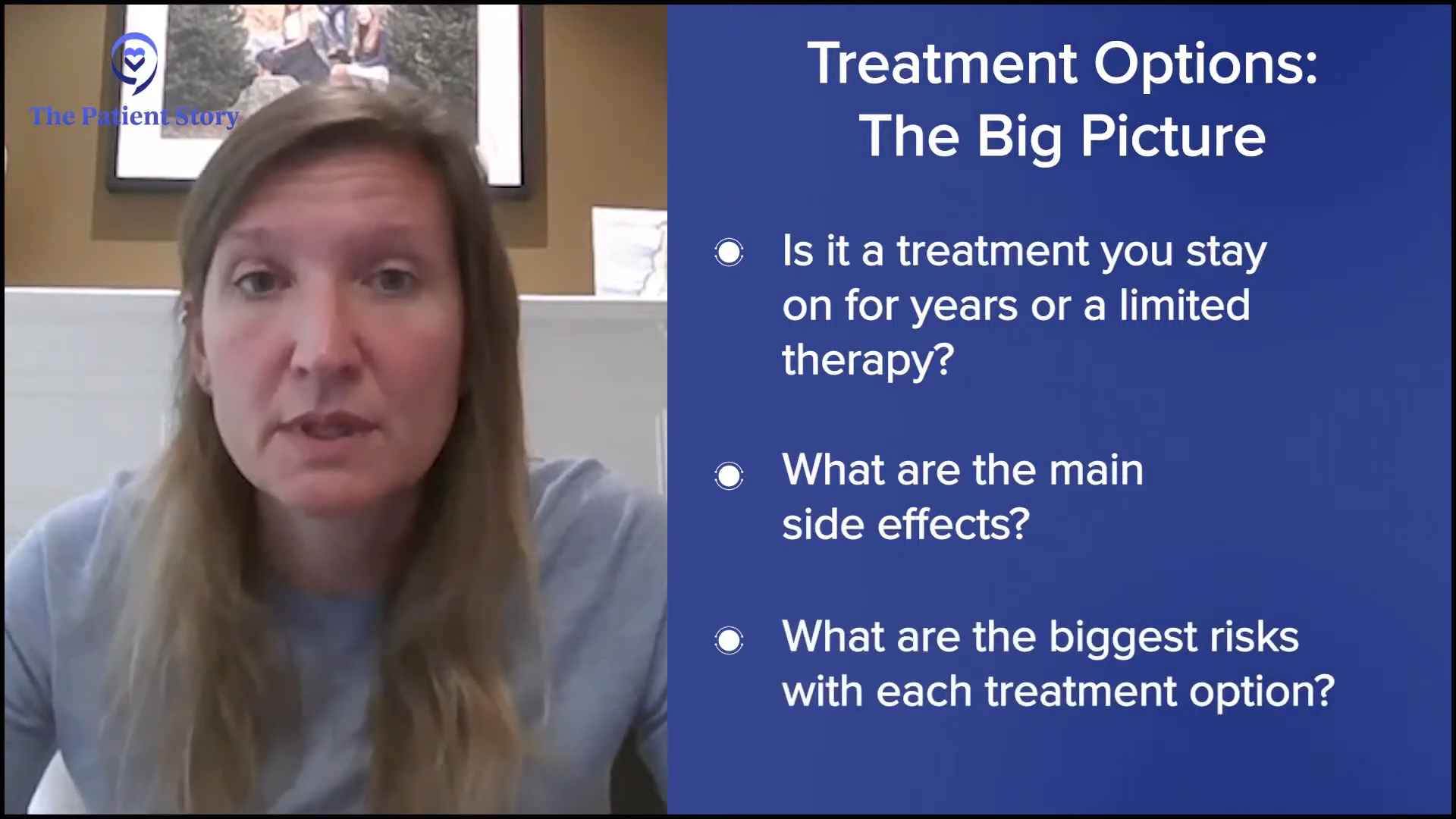

Stephanie: For the majority of patients, when you do talk about treatment decisions, how do you lay these out for them?

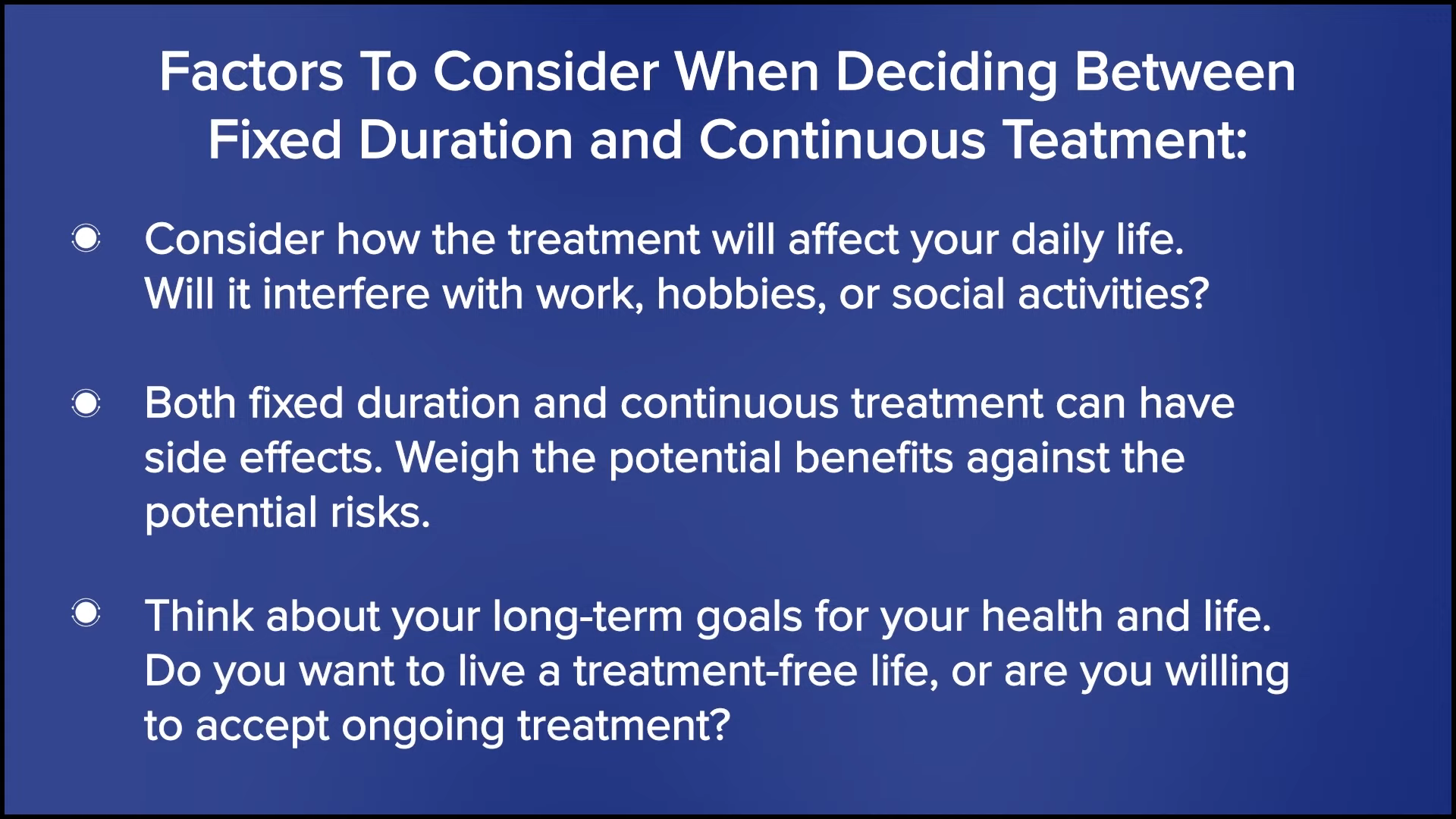

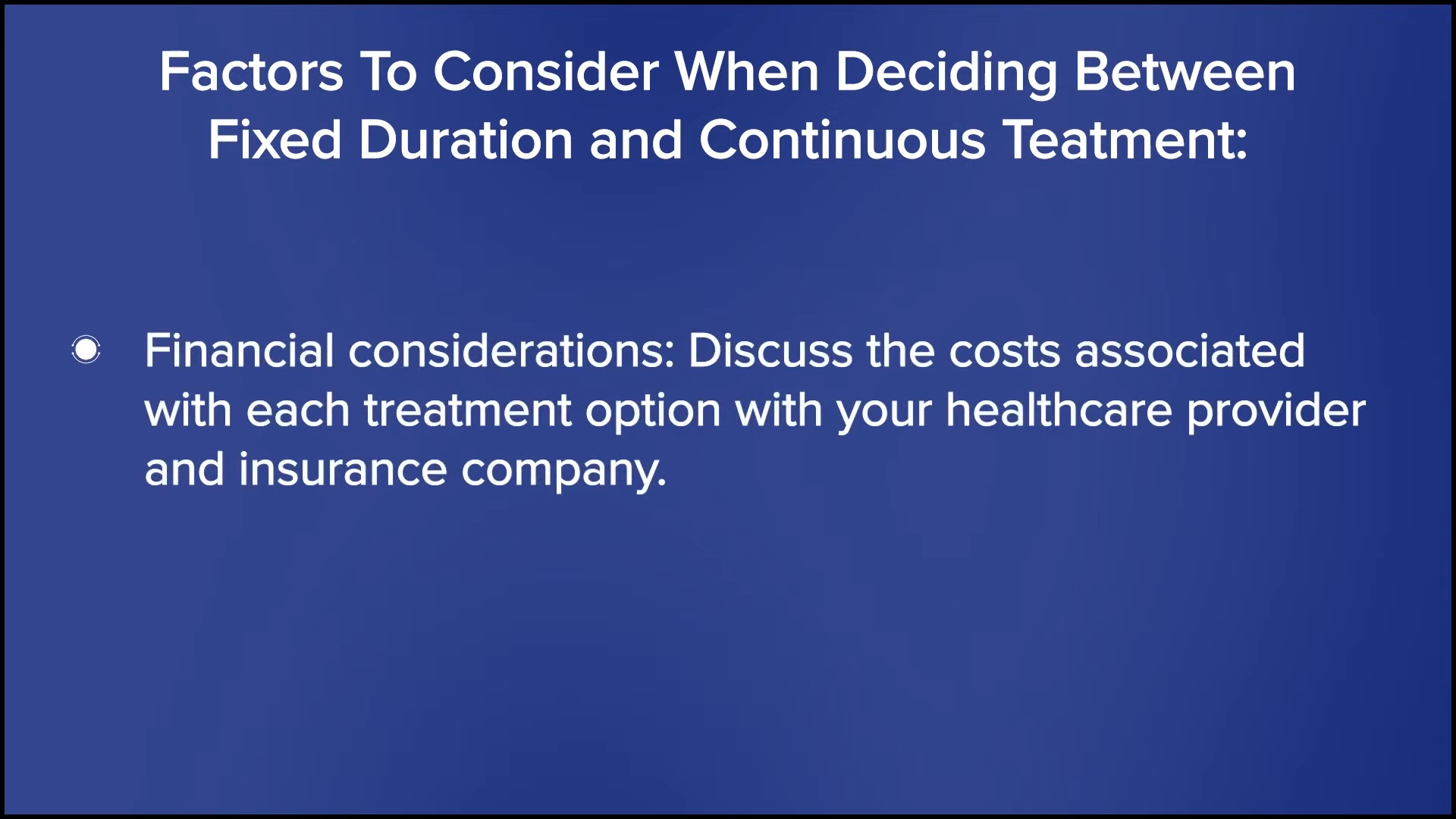

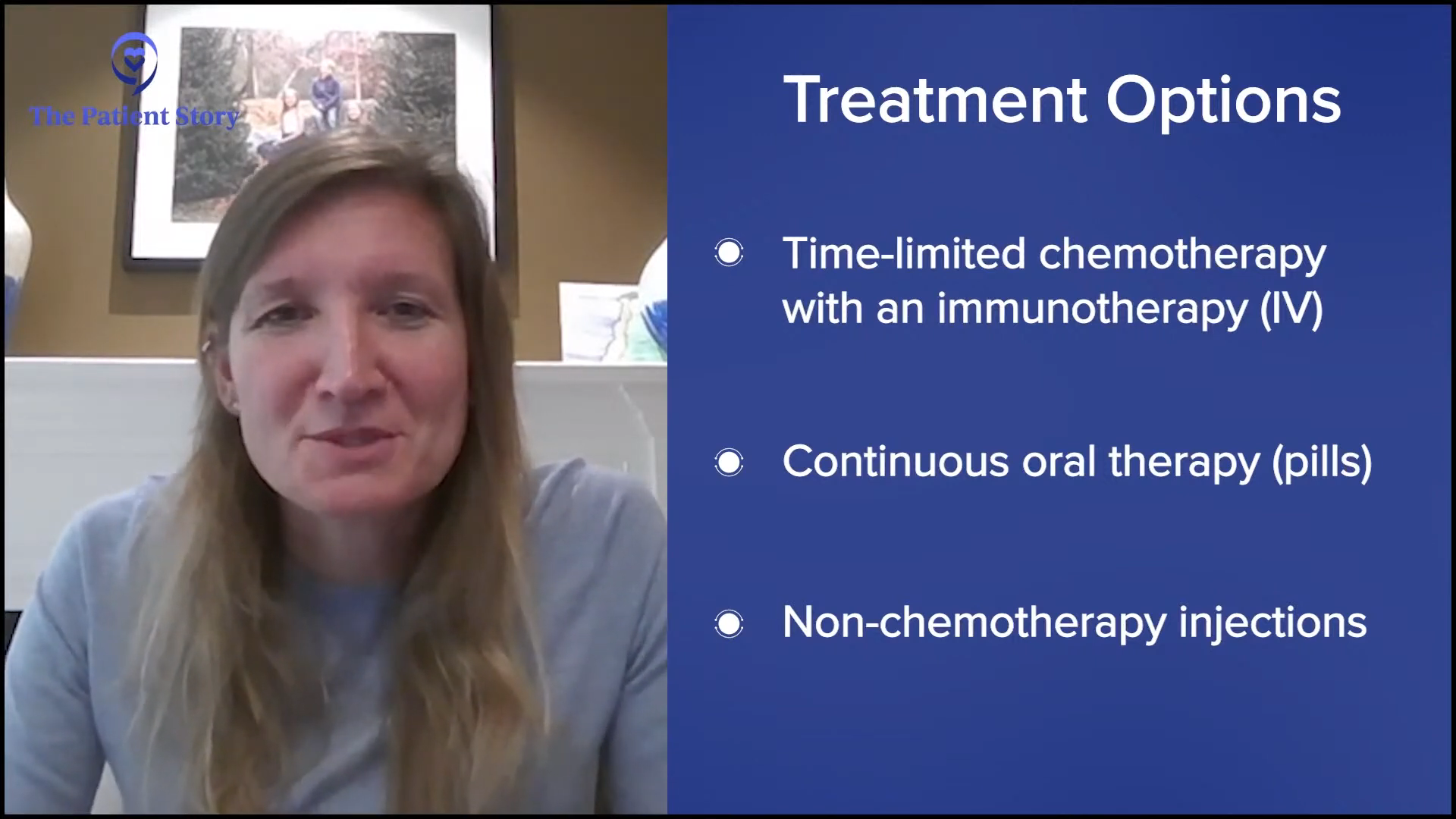

Dr. Sarosiek: I usually walk through the options. Often with Waldenström’s, we’ll have two or three different options. I typically write those out and give the big-picture details. Is this a treatment you stay on for years or is it a limited-time therapy? What are the main side effects that patients can experience? What are the biggest risks that we worry about with each of those treatments?

Next, I try to figure out what might be most important to the patient. Are they someone who doesn’t want to be on a pill every day? Are they someone who would hate to take a pill because they would miss it all the time? That information helps me to guide the patient on which treatment option might be better for them.

Stephanie: Can we go into specifics of the major courses of treatment that you would offer? You mentioned the continuous and time-limited therapies. What patient profile would you consider for one versus the other?

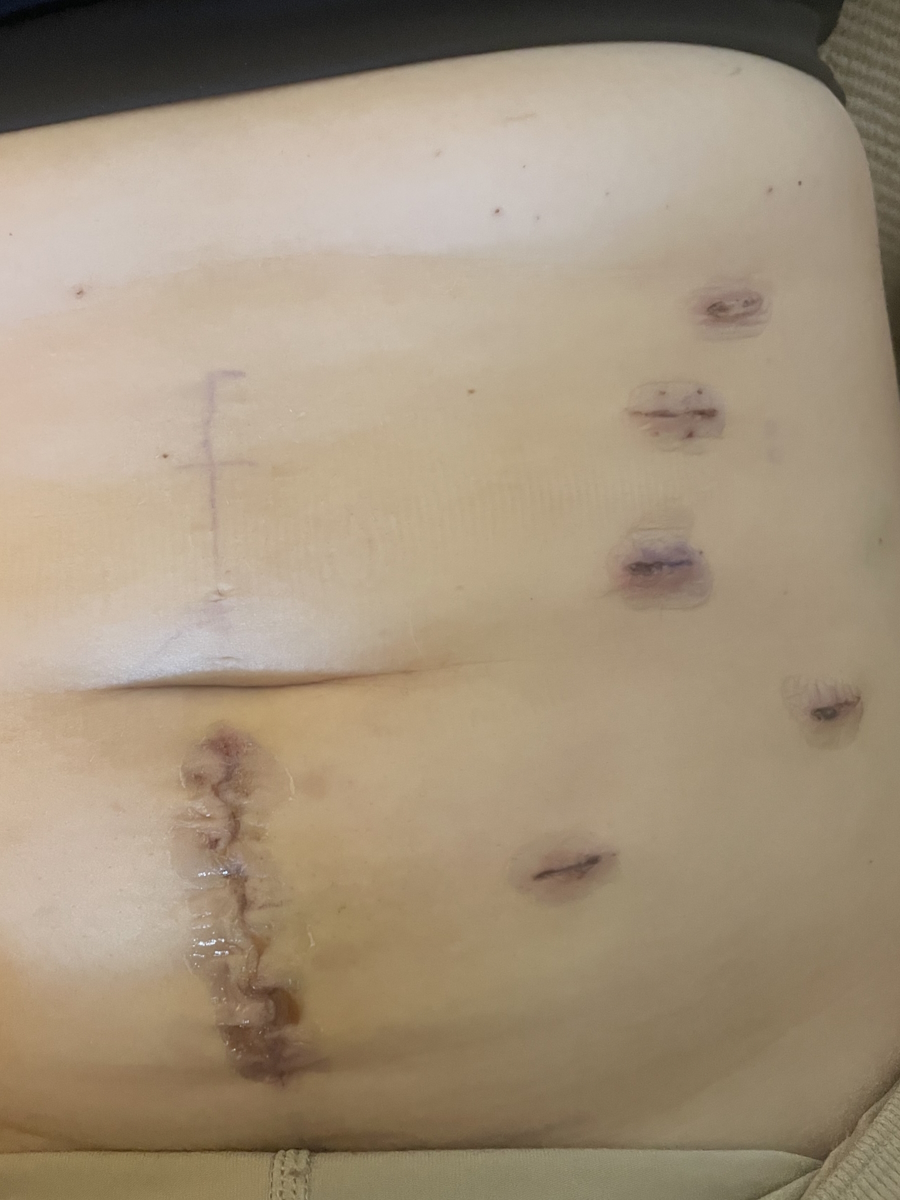

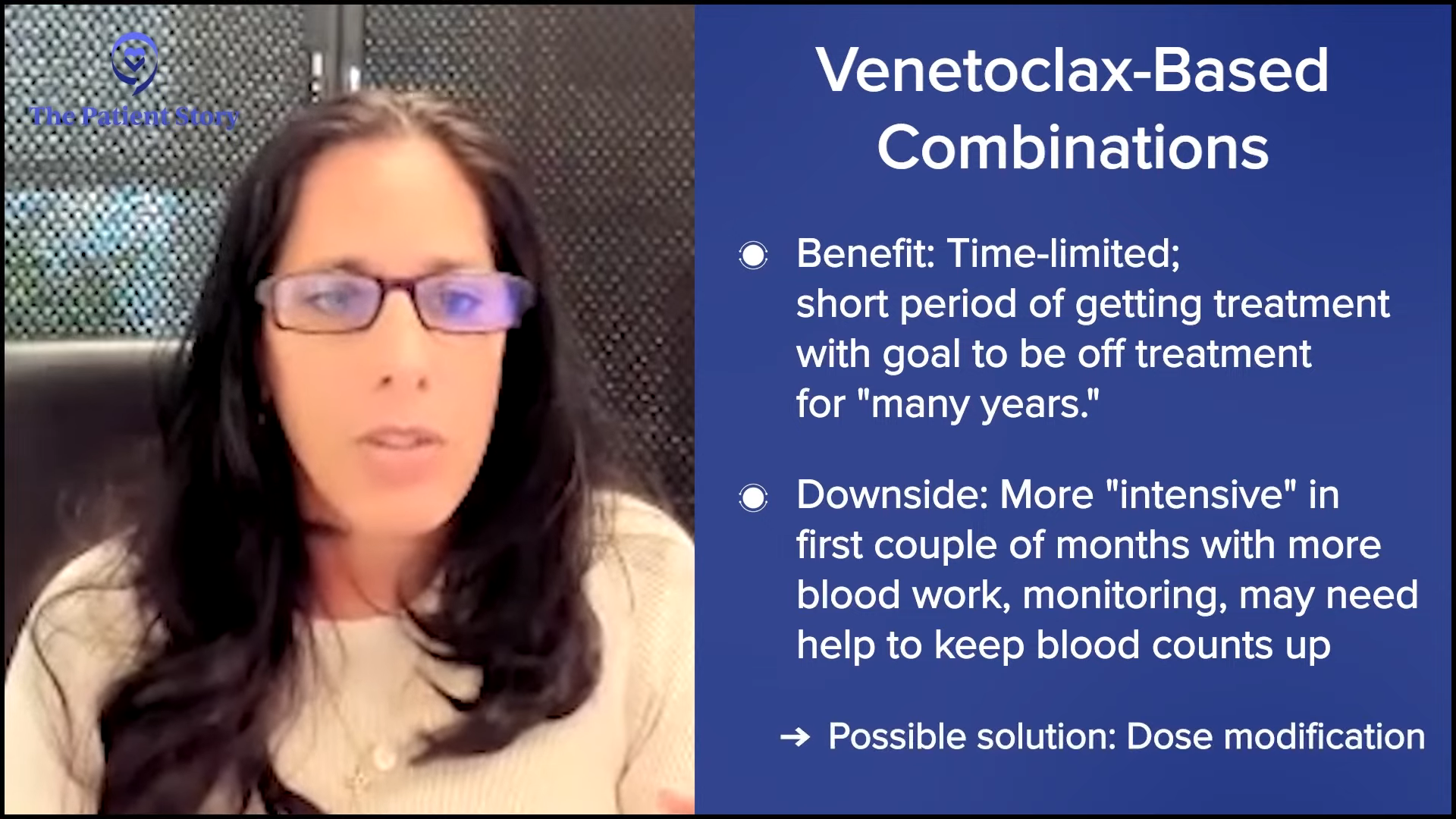

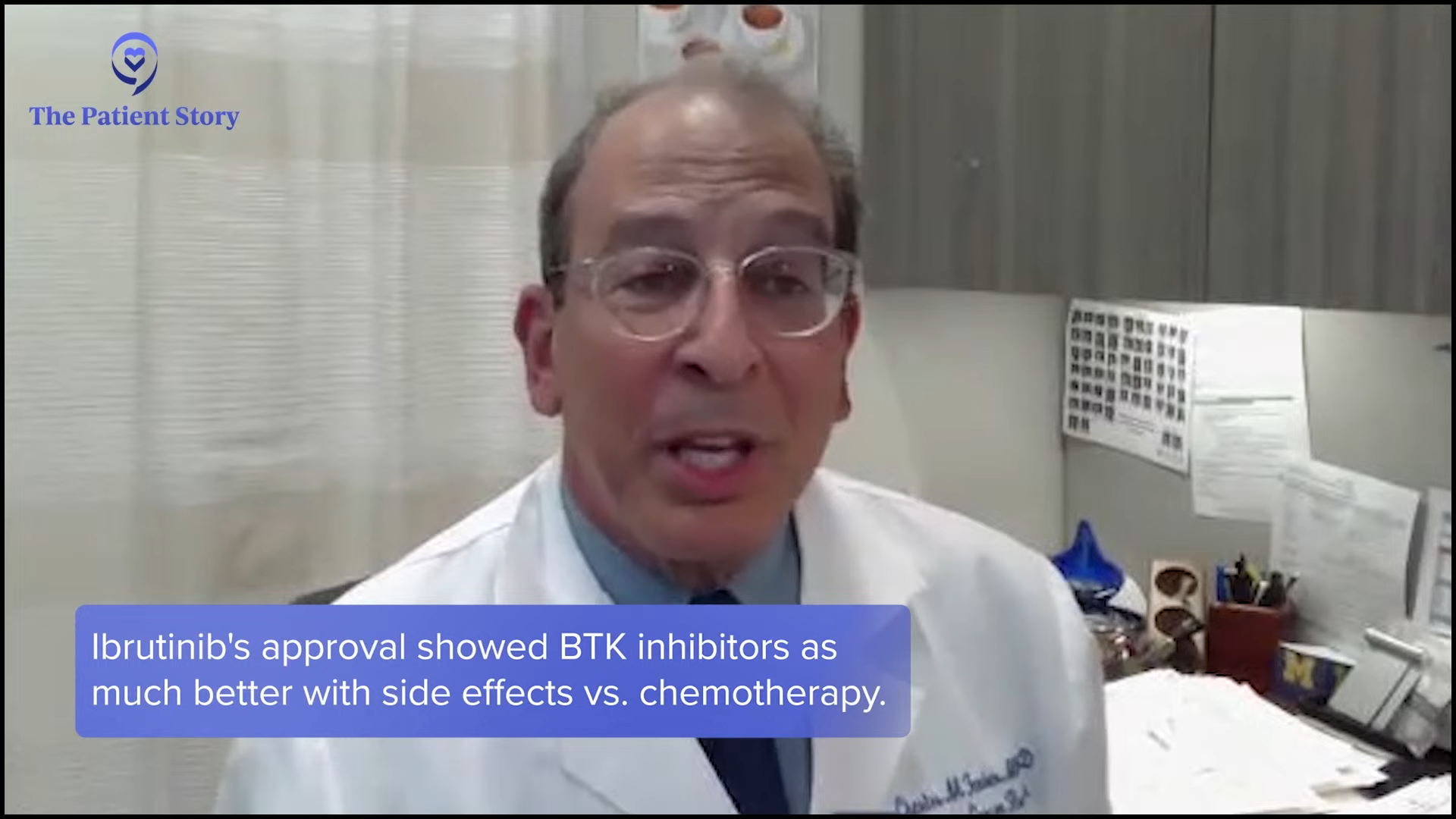

Dr. Sarosiek: For Waldenström’s, one of the main treatments that we talk about is chemoimmunotherapy, which is chemotherapy and immunotherapy together. It’s an IV therapy and it’s time-limited, usually four to six months. Some patients prefer to have a very time-limited therapy. There are risks associated with that, particularly infections. There’s a small risk of damage to the healthy cells in the bone marrow, so that’s an important conversation to bring up with patients

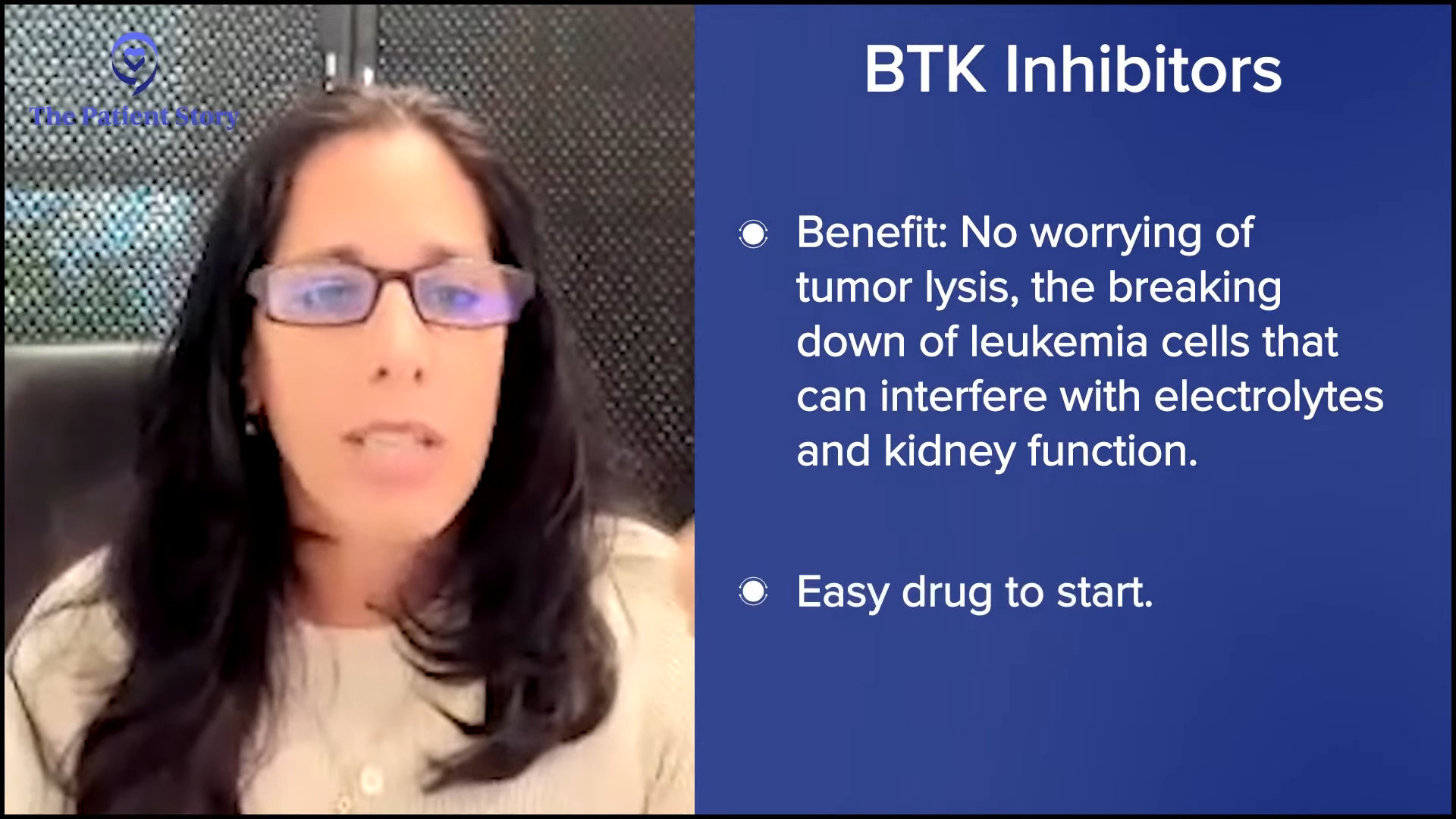

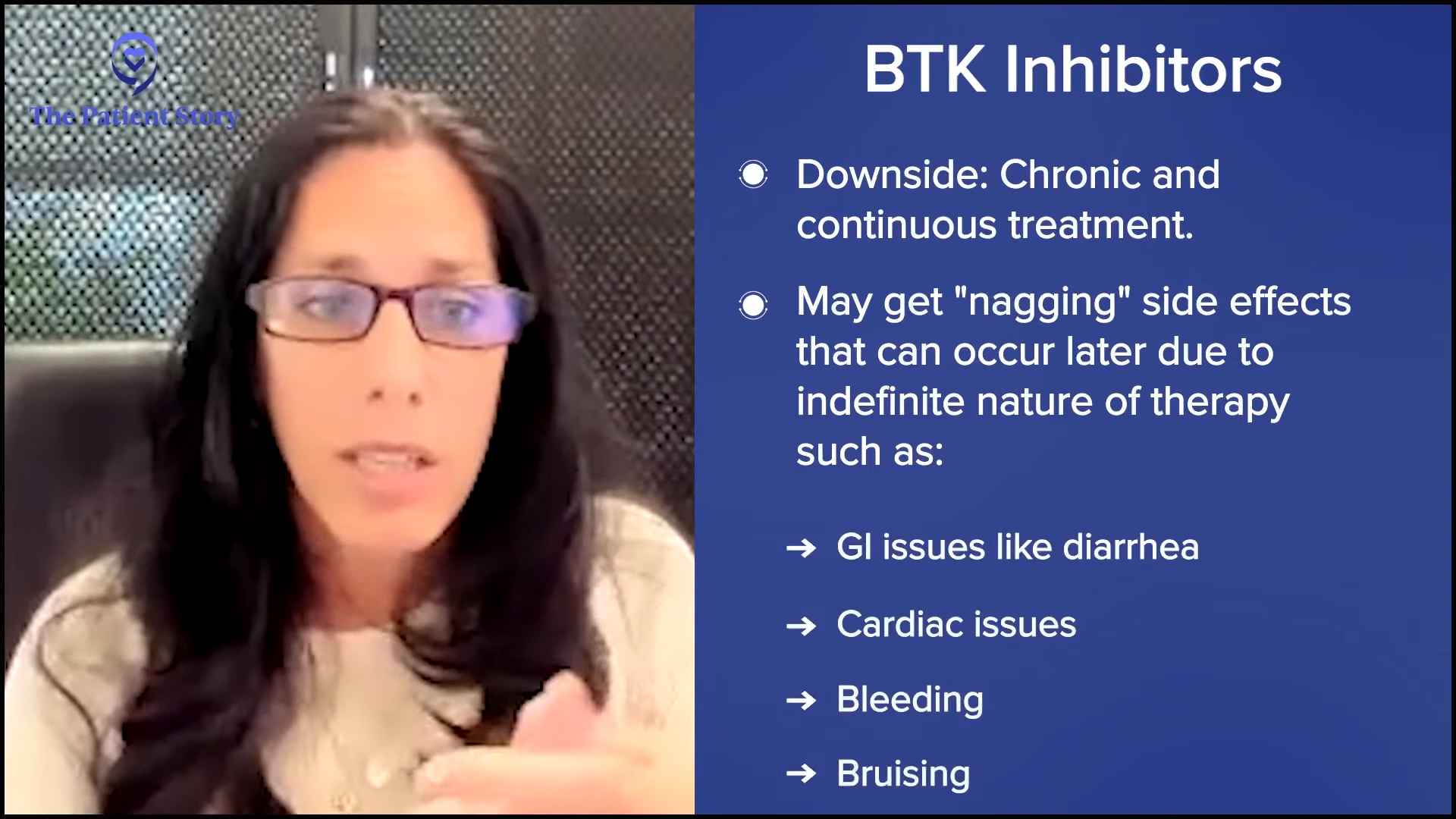

On the other end of the spectrum is another treatment option, which is oral therapy. Patients take pills every day and it’s continuous as long as your disease is responding, which is often for years. It’s a little bit easier because you’re not getting aggressive therapy upfront with all of the treatment at once. It’s low-level therapy all the time. There are risks associated with that as well. For example, a small risk of heart side effects, but in a patient with severe heart disease, I might stray away from using that as a first option.

Then there are some options in between, like targeted therapies that are injections and we use those in a small percentage of people. Luckily, Waldenström’s has a lot of different options.

Stephanie: What are some of the most common questions you get from patients? Are there some that rise to the top when you’re introducing these treatment options?

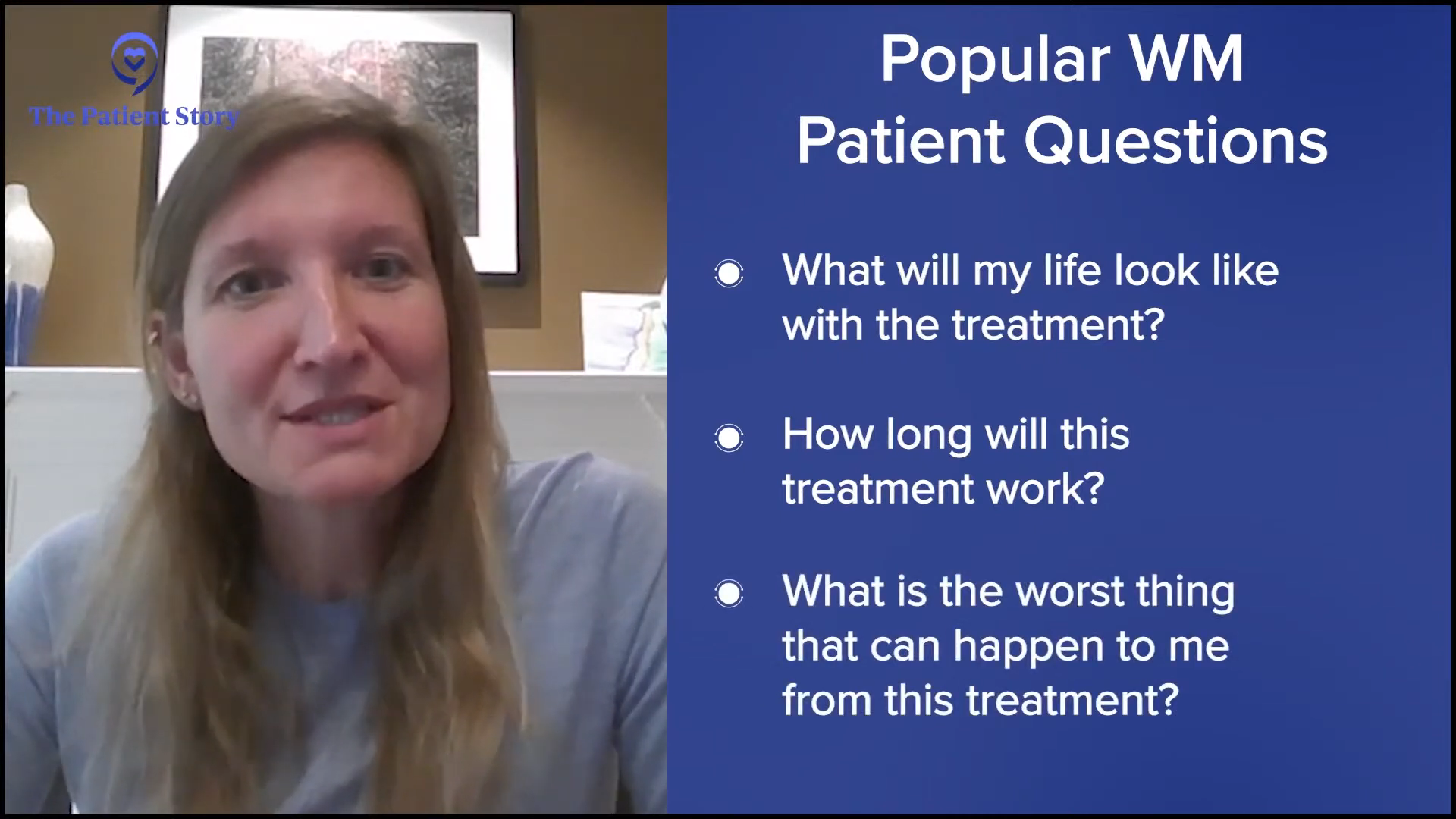

Dr. Sarosiek: An important question is: how will I be able to live my life during these treatments? Many of our patients are still working, have families to raise, and have other things that are important to them, so they ask, “What will my day-to-day life look like?”

Another important question is, “How will this treatment look to people around me? Will I lose my hair? Will I be constantly sick?” That’s a huge part of how patients can deal with and move forward with their disease. The biggest thing is what their lives will look like on the treatment.

The next important question that patients ask is, “How long is this treatment going to work for? What’s going to happen with my disease if I start this treatment? Am I going to need more treatment again in a year or two?”

They also ask, “What’s the worst thing that could happen to me from this treatment? What are the scariest risks associated with the treatment?”

Dr. Sarosiek and I did have to decide on treatment when I was starting to experience some side effects… That’s when Dr. Sarosiek led into the conversation about shared decision-making.

Jason Euzukonis

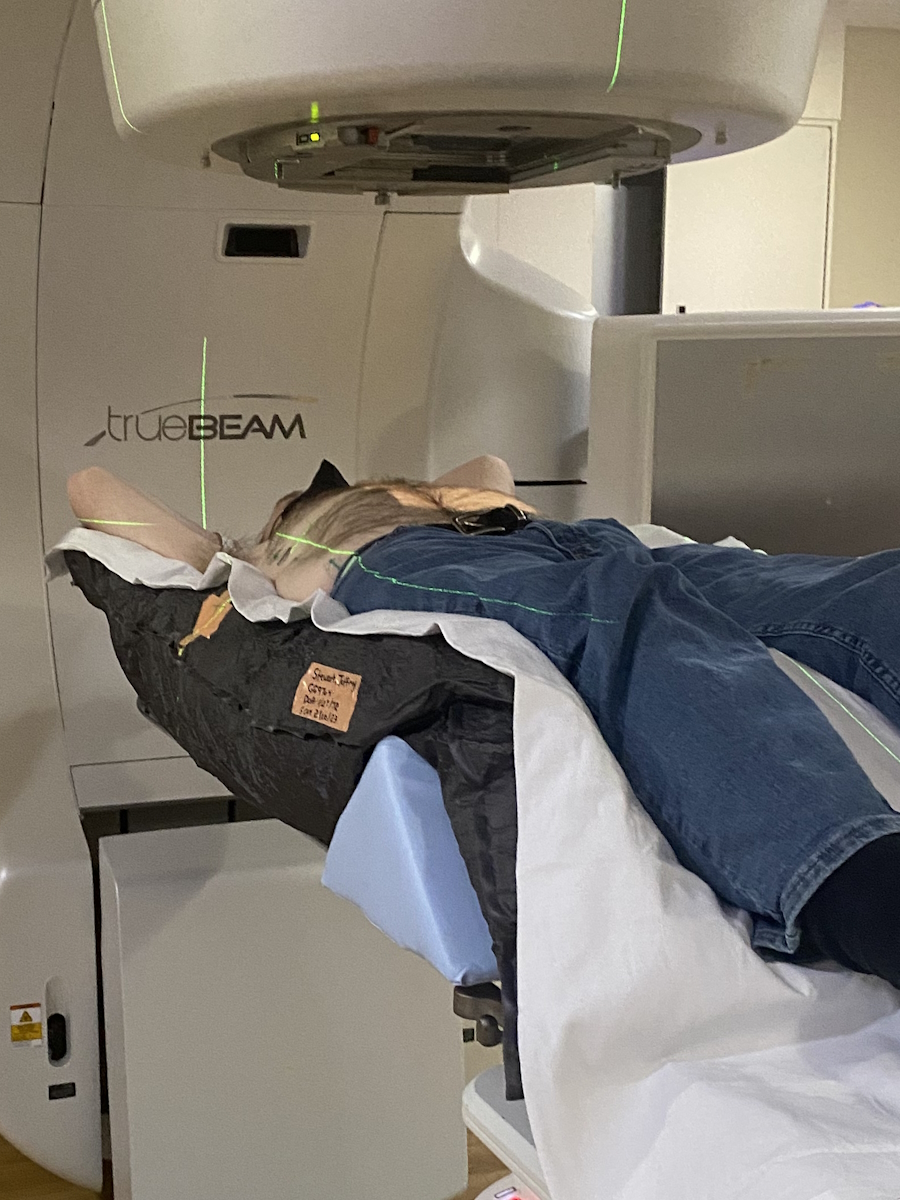

Stephanie: Jason, your first line of therapy was a BTK inhibitor. You had some rituximab infusions earlier on, but you were on the daily pill. What was that like for you? What were the considerations for you before you met with the Dana-Farber team?

Jason: At the time I was diagnosed, there weren’t quite as many options as there are now, so I’m a lot more at ease knowing that there are a lot of good options on the table for me when the time comes. I was already responding well to a BTK inhibitor. By the time I got to Dana-Farber, there wasn’t a need to change it, I guess.

Probably the more relevant question from someone in my shoes is: had chemotherapy been an option, which way would you go? That’s a common question with pros and cons, as Dr.Sarosiek mentioned for both approaches. Had both been an option for me, I likely still would’ve chosen the same path of the BTK inhibitor.

As a younger patient, there are some things to think about in terms of the long-term potential side effects of chemotherapy versus targeted therapy. I’m in pretty good health overall, younger, and don’t have heart issues, so I wasn’t all that concerned about any potential side effects surrounding my heart.

Dr. Sarosiek and I did have to decide on treatment when I was starting to experience some side effects; nothing overly threatening but more annoying. I approached her and asked, “What do you think about cutting the dose?” That’s when Dr. Sarosiek led into the conversation about shared decision-making and presented this newer version of the targeted therapy. I guess it’s the best example of the decision-making with Dr. Sarosiek that put me on the right path.

Stephanie: What I appreciate about this is you had clearly done enough research where you even knew to ask about lowering the dosage. What got you to that point? What were your considerations about staying on something that had been working versus shifting completely?

Jason: At the end of the day, part of it is a certain amount of trust in your doctor. I have my feelings on things, but I quite literally would trust Dr. Sarosiek with my life. But at the same time, this is where hopefully people do their homework and read up on what’s latest and greatest.

I had already read up a bit on the newer targeted therapy that Dr. Sarosiek presented and when she mentioned that, I was also fortunate that it had recently been approved. I was already aware of it and knew that the side effect profile was better on it, so I was very comfortable when she brought up moving to that.

Knowing the side effects I was dealing with, there was a good chance a lot of it was related to what I was on. With the newer version of that, based on the data, those side effects were improved. It’s a combination of doing your research, trusting your doctor, and asking them what they think.

Addressing Side Effects

Stephanie: Dr. Sarosiek, how many times are you seeing people who are nervous to even talk about the side effects and how do you address that? We’ve heard from other people who are hesitant to bring up side effects because they’re worried their doctor’s going to take them off of their treatment because they want to preserve as many options as possible.

Dr. Sarosiek: A lot of patients are comfortable discussing their side effects; that’s my experience, at least. They’re comfortable saying what it is that’s going on without having to worry that we’re going to adjust their treatments or change their outcomes because we stopped therapy or changed therapy. I would say most patients are comfortable saying if they have a side effect.

Although maybe I have some patients who are scared to tell me that they have side effects, on the other hand, I do have some patients who don’t want to know about potential side effects from treatment. A lot of patients want to know what they can expect so that if it happens, they’re aware and not worried. But once in a while, I’ll tell a patient this side effect might happen, but they don’t want to know because either they’re then going to worry it’s going to happen or they feel like they might manifest that for themselves if they know about it.

We can still have a conversation about if it’s a side effect they can live with or if we need to change their treatment because of it.

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek

Again, it’s trying to feel out what the patients are comfortable with hearing in terms of side effects. I hope I make patients comfortable to know that they can tell me about their side effects without me immediately making a treatment decision for them based on the reported side effects. We can still have a conversation about if it’s a side effect they can live with or if we need to change their treatment because of it.

Stephanie: Jason, what were the main key side effects that you were experiencing that brought this discussion up for you?

Jason: Mouth sores were probably the biggest one. I had a lot of mouth sores. They were brutal. I was starting to experience some joint pain. Sometimes it’s tricky to determine if I’m experiencing side effects from the treatment or if I’m getting a little older. But I was getting the sense that it was a sudden increase in joint pain.

The blood pressure was a little higher than I would’ve liked. The platelet count wasn’t dangerously low, but it was a little on the low side. From what I had been reading on the newer version, it seemed like a lot of those side effects had been improved, so I was pretty comfortable. I was responding well; it was just annoying side effects.

Stephanie: Dr. Sarosiek, how do you navigate the conversations? People have different preferences and there is that mental hurdle of not wanting to make too much of a deal about side effects.

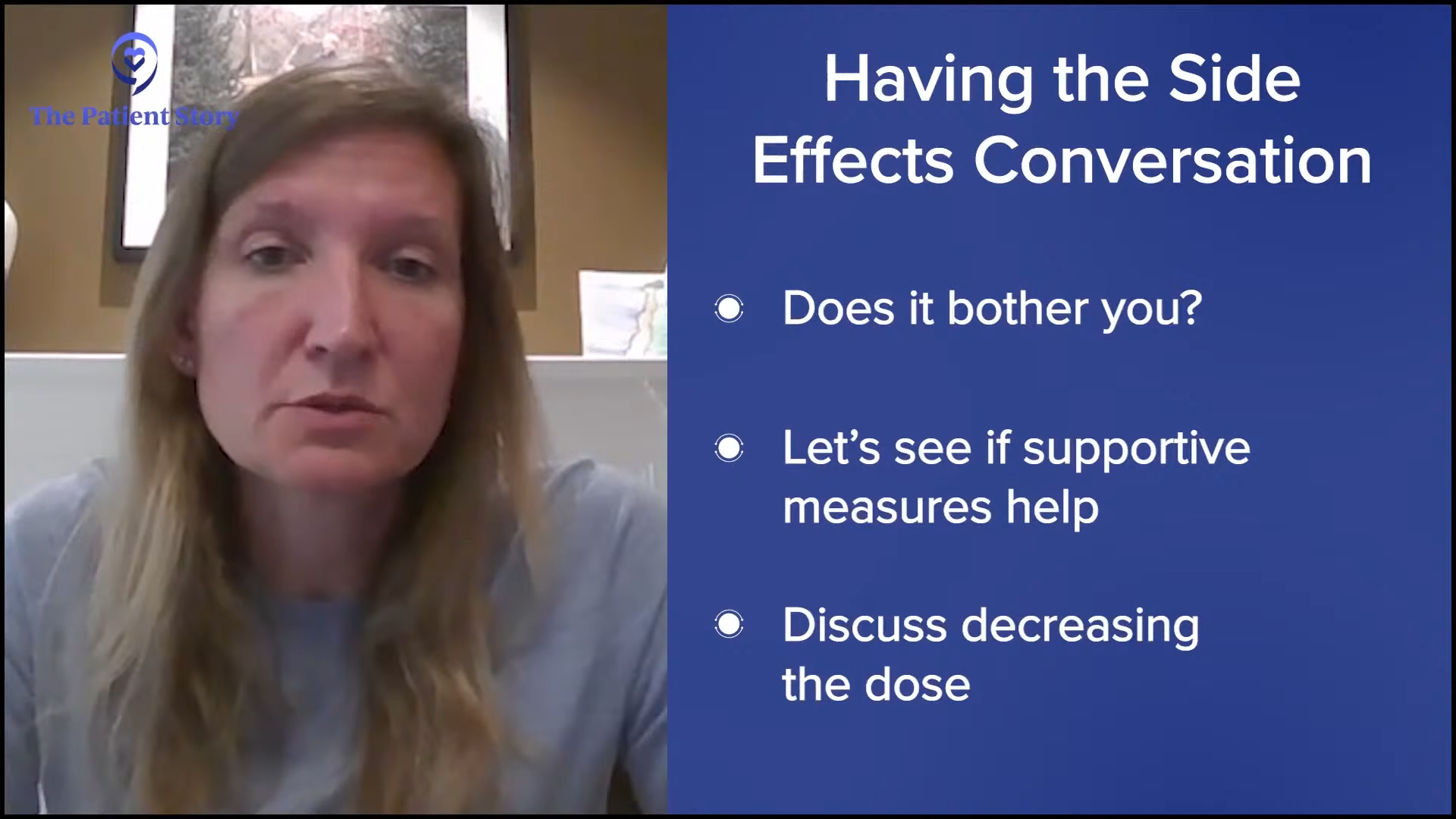

Dr. Sarosiek: When patients have side effects, then I try to feel out if there is anything that they would like to do about them. If someone has mild, loose stool once every few weeks, they might say, “Oh, forget it. It doesn’t bother me. I’m telling you about it so that you know.”

My next approach is to try to find some supportive care measurement that we might be able to do. I have a lot of patients on the treatments we use for Waldenström’s who have loose stool or diarrhea and typically, adding fiber to their diet, like a fiber supplement once a day, is quite helpful. It treats it and they can continue on the same dose.

For a lot of the side effects, I ask if it bothers them, and if it does, we try some supportive measures. If the supportive measure doesn’t help, then it is a conversation about whether or not we want to decrease or change the dose. In that case, I try to bring up any data that we have in that setting to reassure patients that if we decrease the dose, the patients will still have very good outcomes. Often, we have data to help guide us if we should reduce the dose or not. We think about that, but usually, we try other supportive things first so that we can try to stick to the regimen that’s proven in the literature.

As Dr. Sarosiek knows, I typically will ask, ‘Hey, what are you seeing? What’s the latest and greatest? Any thoughts about the future?’ That’s been my approach.

Jason Euzukonis

Patient-Physician Relationships

Stephanie: This is a long-term relationship that’s happening. What are the other points where major discussion tends to happen? I imagine it’s talking about active surveillance or watch and wait, as well as at any point that treatment may need to come up. Is that the case? How do you both approach this as an ongoing relationship that’s different than other cancers?

I think about it because I get reminded twice a day when I take my pill. I try to stay up to date on what’s latest and greatest. Ultimately, the day will come when Dr. Sarosiek and I will have to figure out what the next best step is. The good news is there are a lot of good options, so that lessens my anxiety knowing that there’ll be a lot of good options on the table for me when the time comes.

Jason: I’m on treatment, but while I could potentially get many more years out of this treatment, the reality is at some point, I’ll start to slowly lose the response. From a mental standpoint, I’m pretty good at being able to compartmentalize. I’m fortunate enough that I can move through my day without it weighing on me.

We meet every three to four months. I’ll go in for blood work, which is helpful for me because we can get a pretty good idea of not just the disease itself but also my overall health to avoid any pitfalls there as well. As Dr. Sarosiek knows, I typically will ask, “Hey, what are you seeing? What’s the latest and greatest? Any thoughts about the future?” That’s been my approach.

If we’ve known them for months or years and they show up one day and seem a little bit different than they have been at every other visit, then something’s off with their disease and we should look into it.

Dr. Shayna Sarosiek

Dr. Sarosiek: From my perspective, part of what drew me to oncology and which I love about Waldenström’s is we have this luxury in most cases to get to know the patients and be able to sit down and talk about them outside of their diagnosis. That’s what I love about what I do. It’s great because I get to know the patients and that’s how I know how they are doing.

If I know a patient is a runner, loves to spend their time golfing, or loves to spend their time with their grandkids, then they come in and say, “I cut back on my running,” or “I’m not hanging out with my grandkids,” I don’t necessarily have to ask, “What are exactly your symptoms?” I know them well enough to realize that if they’re not doing what they love to do or what they’re usually doing, something has changed.

Part of active surveillance, watch and wait, or monitoring someone on treatment is getting to know them and being able to tell if they’re not able to do the same things that they were doing. If we’ve known them for months or years and they show up one day and seem a little bit different than they have been at every other visit, then something’s off with their disease and we should look into it. What I love about oncology and what I do now is getting to spend time with my patients and getting to know who they are.

Dr. Sarosiek wants to learn more about her patients and who they are beyond the diagnosis so that she can treat them as a whole person and not just the disease specifically, allowing her to understand how different options might impact them and their quality of life.

Stephanie Chuang

Jason: I’m confident that there aren’t many doctors in the world who know this disease and the science around this disease as well as Dr. Sarosiek, but she also knows me well and that’s critical in the doctor-patient relationship.

Stephanie: I love that you’re both highlighting that this is a long-term relationship that’s very different than other cancers. We talk a lot about survivorship in other spaces, but this is an ongoing conversation. You know that Dr. Sarosiek knows her stuff and she’s at the top of her game. You talked about the anxiety and mental load that you had to work through daily.

The difference is Dr. Sarosiek wants to learn more about her patients and who they are beyond the diagnosis so that she can treat them as a whole person and not just the disease specifically, allowing her to understand how different options might impact them and their quality of life. That’s such an amazing thing that’s happening and I do hope that patients, care partners, and physicians will take that away.

Is there anything else you want to mention that is important in the context of having patients and physicians be partners? Are there misconceptions? Are there any other things that people are missing that you think would benefit them?

Dr. Sarosiek: It’s important to find a physician who is open to learning and is willing to work with you within your space. We’re all different people, as we all know. We are born into families that have different personalities and we learn to work together. Sometimes, we find friends along the way who are more like family because they’re people you relate to. You want to find a physician like that who can meet you in your space.

Sometimes, you have different personality issues and maybe you want to find a different doctor who can work with you in a way that would make you most comfortable with your disease. It’s worth getting second opinions or meeting other physicians and finding someone that you feel can be your partner through the journey. I know I fail in some ways, but I try my best to be a partner with my patients and hopefully, patients can find someone who can do that with them.

Jason: Take care of your health, both physically and mentally. Join support groups. If you have Waldenstrom’s, go to the IWMF.com. Ask your doctor lots of questions. Don’t be afraid to seek multiple opinions. Find a doctor who you’re comfortable with and who knows this disease inside and out, if possible, or at least ask your doctor to be in touch with the doctor who knows this disease inside and out.

Waldenström’s Clinical Trials

Stephanie: Dr. Sarosiek, do you ever talk about clinical trials with your patients? It’s a huge topic and very important in a space where there’s so much development. What is your mindset in terms of the research? How and when do you bring them up to patients?

Dr. Sarosiek: I’m a huge advocate for clinical trials and in general, especially in academic institutions, we tend to use clinical trials a lot to be able to offer novel therapies to patients. As Jason mentioned, he’ll come in and ask about novel therapies, so often it comes up in conversation with patients when they ask what’s new and we’ll talk about clinical trials.

If there is a trial available that a patient would qualify for, I always bring it up as a potential option. Some patients can’t participate because of logistics and not being close to a center with clinical trials, but I will always bring it up because I think it’s the best way that we can move the field forward. If a patient is eligible for a trial, it will certainly come up in conversation with me.

There are so many options that doctors are trying to figure out the right order of treatments, which one is more effective and safer than the other, and the only way we can get the answers to those questions is by patients taking part in clinical trials.

Jason Euzukonis

Jason: I’m still responding well, so I’m not there yet. But as Dr. Sarosiek mentioned, I do make it known that I’m very much open to a clinical trial if and when the time comes.

The good news is that there are so many new options now and they’re making advances every day. The challenge is there are so many options that doctors are trying to figure out the right order of treatments, which one is more effective and safer than the other, and the only way we can get the answers to those questions is by patients taking part in clinical trials.

A lot of people think that with clinical trials, they’re guinea pigs, but no. There are a lot of great options and the doctors are looking to get answers.

Stephanie: From the patient’s perspective, what would be your major considerations on whether you would want to go on a particular trial?

Jason: I’d be very interested in a clinical trial that combines agents that aren’t chemotherapy and will eventually be able to give me a break from treatment. There’s a lot of progress being made on that front. I know that’s a priority for a lot of the centers and doctors out there.

At the end of the day, it’s a drug… Each one of us is different, so I don’t know how it’s going to impact me long-term

Jason Euzukonis

Stephanie: That makes perfect sense, for sure. But if we could dive in, can you share more about what it is that’s coming up for you? Chemotherapy sounds like it’s the side effects and quality of life. With time off treatment, who doesn’t want a break? Can you describe why that’s so important for you and what’s driven you to that point?

Jason: With the targeted therapy that I’m on now, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of risk long-term, but it’s still relatively new and we don’t know that. I also know that these treatments aren’t cheap and pretty taxing on the healthcare system to remain on these things, so I know that’s a consideration.

At the end of the day, it’s a drug. There are no free rides when it comes to these medicines. Each one of us is different, so I don’t know how it’s going to impact me long-term if I stay on this for 10, 15, or 20 years. I likely won’t be on it for 20 years, don’t get me wrong. But as we say in the Waldenström’s community, if you know one Waldenström’s patient, you know one Waldenström’s patient. That can be applied to a lot of different cancers, but the bottom line is I don’t know the long-term ramifications of continuous therapy, so it would be nice to not be on a drug for a period of time.

Stephanie: Dr. Sarosiek, is there anything else that you think would be helpful for patients to understand both in terms of guidance for them and questions that they can ask that might be helpful?

Dr. Sarosiek: Some concerns that patients bring up when they hear clinical trials include: Are you testing something that you don’t know anything about? Am I going to get a placebo so I won’t be getting any treatment for my cancer? Does this mean that this is the last option for me, that I’m going to be dying with this cancer soon?”

It’s important for patients to know that that’s not the case. Often, we have many trials for patients who have never been treated before and this is going to be their first treatment in decades of life that they’ll live with Waldenström’s. It’s important for patients to know that clinical trials are a way to get novel therapies.

While clinical trials may not be right for everybody, it’s great to have the conversation so people can choose what is right for them.

Stephanie Chuang

Currently, we have a clinical trial that uses two oral therapies that we know independently work very well in Waldenström’s and we use them as the standard of care. But the trial is trying those two together so that you can use them for a limited amount of time and get a better response. It’s a way to get novel therapies or advanced therapies that otherwise wouldn’t be available as a standard of care.

Stephanie: Sometimes you hear people say, “Tomorrow’s treatment today.” While clinical trials may not be right for everybody, it’s great to have the conversation so people can choose what is right for them.

Conclusion

Stephanie: Thank you, Dr. Sarosiek and Jason, for joining this conversation. You highlighted a lot of the nuances that come up in the conversations between the physicians and the patients. You’re a great example of how partnership can work well here, so thank you both so much.

Tiffany: Thank you, Jason, Dr. Sarosiek, and Stephanie for such a great discussion. It’s so important to be empowered and to lean into communication so that you and your caregivers can make informed decisions about your care.

Thank you to The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS). Check out their Information Resource Center, which provides free one-on-one support. Thank you to the International Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation (IWMF) which has over 60 peer support groups worldwide where they share experiences, discuss concerns, and exchange information.

Special thanks to The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and the International Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation for their partnership.

Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia Patient Stories

No post found