Looking to the Future: Treatment Paths for Relapsed/Refractory DLBCL

Plus: How Academic & Community Hospitals Work Together for You

For people facing relapsed or refractory DLBCL, the path forward can feel uncertain and overwhelming trying to weigh treatment options.

That’s why this program brings together Dr. Joshua Brody from Mount Sinai and Dr. Amir Steinberg from Westchester Medical Center, two lymphoma specialists who coordinate closely across academic and community settings. Moderated by The Patient Story’s own founder and DLBCL survivor, Stephanie Chuang, they’ll share how new therapies are changing the landscape and how working together across systems helps ensure patients have access to the most up-to-date treatments and support.

Topics:

What relapsed/refractory DLBCL means for patients

Latest treatment advances and what they could mean for care

How academic and community oncologists collaborate on patient treatment

Clinical trial opportunities and why they matter

Practical tips for patients to advocate for themselves and ask the right questions

What the future may hold for people living with DLBCL

This program has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

Register for this informative program then invite a friend or care partner.

Table of Contents

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

Introduction

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, there! I’m so glad you could join us for our discussion. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can return or be difficult to treat. This conversation aims to help you, as a patient or care partner, to walk away with questions you can ask your healthcare team if the first treatment doesn’t work. I want to highlight that, as difficult as this situation is to be in, we keep hearing from DLBCL experts that there’s so much research and so many developments happening in terms of lymphoma treatments, and that’s what we’re going to dive into. We’re also going to talk about how you can work with different kinds of doctors who work at different centers, as well as busting clinical trial myths and sharing more of what they are.

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, there! I’m so glad you could join us for our discussion. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can return or be difficult to treat. This conversation aims to help you, as a patient or care partner, to walk away with questions you can ask your healthcare team if the first treatment doesn’t work. I want to highlight that, as difficult as this situation is to be in, we keep hearing from DLBCL experts that there’s so much research and so many developments happening in terms of lymphoma treatments, and that’s what we’re going to dive into. We’re also going to talk about how you can work with different kinds of doctors who work at different centers, as well as busting clinical trial myths and sharing more of what they are.

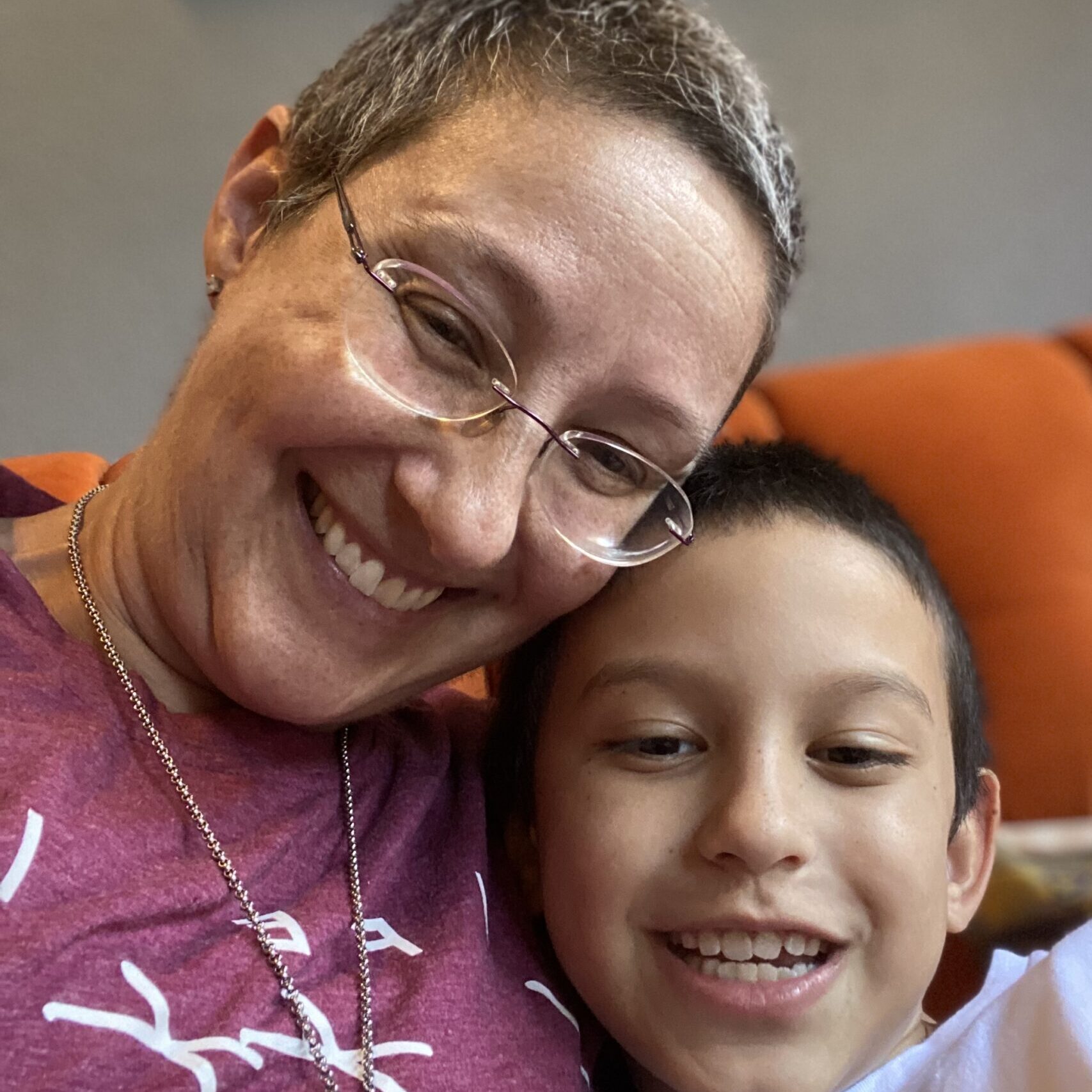

My name is Stephanie Chuang. I’m the founder of The Patient Story, but more importantly, I had my own diagnosis of DLBCL. I went through hundreds of hours of chemoimmunotherapy and I’m lucky to have had no evidence of disease for eight years now. I started The Patient Story as a result of my experience of feeling isolated in trying to find other people who were dealing with the same diagnosis and trying to empower myself when all I was finding was a lot of medical jargon.

Our mission at The Patient Story is to help you find community and humanize the diagnosis through educational conversations and in-depth patient stories and videos, thanks to the amazing people who want to share their stories to help other people. You can find hundreds of these stories at ThePatientStory.com and on our YouTube channel, @ThePatientStory.

We would like to thank our sponsors, Genmab and AbbVie, for their support of this program, which enables us to host more programs like this at no cost to our audience. We want to note that The Patient Story maintains full editorial control. While we hope this conversation is helpful, this is not meant to be a substitute for medical advice. It’s informational, so please consult your healthcare team when making decisions.

Finally, but importantly, we want to hear from you. Your voice matters so much in helping us shape what we put out next. Was this helpful? What would you like to hear more about? What could we do better? Please let us know what your feedback is.

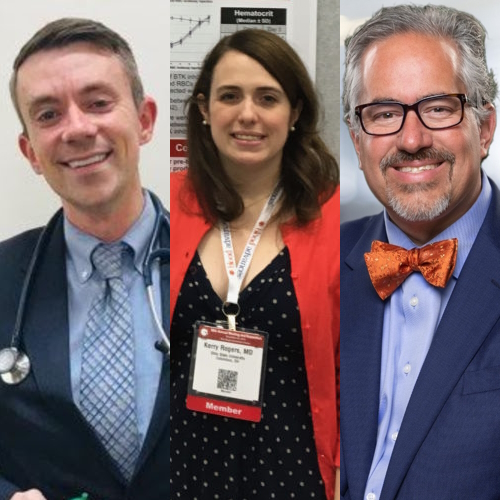

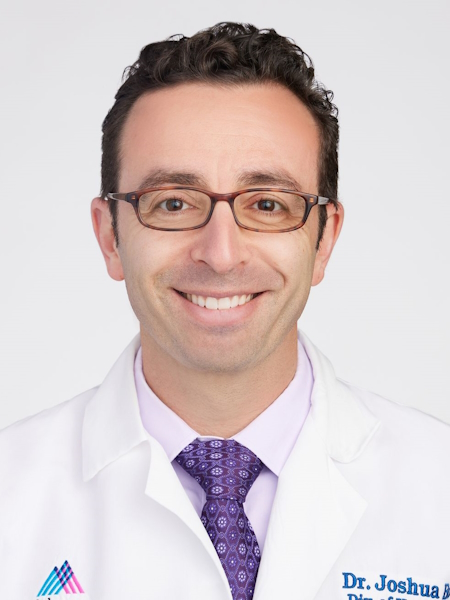

I’m so honored to be joined by two amazing experts. Dr. Joshua Brody, who’s a friend of The Patient Story, is the director of the Lymphoma Immunotherapy Program at The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai in New York, a faculty member of the Icahn Genomics Institute, and the primary investigator at The Brody Lab.

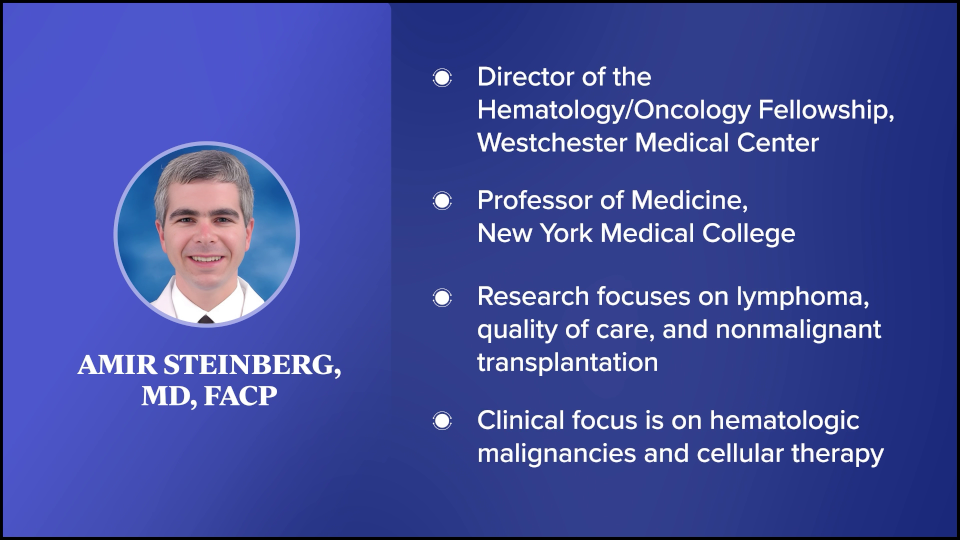

We’re also so lucky to be joined by Dr. Amir Steinberg. He’s the director of the Cellular Therapy Program at Westchester Medical Center in New York and a professor of medicine at New York Medical College. Dr. Steinberg has been involved in research focused on lymphoma, quality of care, and nonmalignant transplantation. I got a rundown of how the two of you know each other, so there’s some history, which is wonderful. I’m so excited to have this discussion with you both.

But before we jump into this educational content for our patients and care partners, we would love to humanize you, doctors. You’re so great at what you do. You’re brilliant. But we’d love to understand more about the personal aspect. Dr. Brody, again, thank you for being here for the millionth time. You clearly spend a lot of time outside of the clinic and research to help patients who are not in your direct care. You’re very busy. Can you share what motivates you to continue dedicating your time?

Dr. Joshua Brody: Oh, you said this is going to humanize me and though this is going to make me sound like a saint, those who know me, like Amir, know it’s not true. There are things you could help people with. You could help people with all kinds of problems. But cancer just sometimes seems like the most unjust thing. People did everything right. They didn’t do anything bad. They were healthy. They tried everything. They have a family. They worked so hard. And then they get struck down seemingly out of nowhere.

Dr. Joshua Brody: Oh, you said this is going to humanize me and though this is going to make me sound like a saint, those who know me, like Amir, know it’s not true. There are things you could help people with. You could help people with all kinds of problems. But cancer just sometimes seems like the most unjust thing. People did everything right. They didn’t do anything bad. They were healthy. They tried everything. They have a family. They worked so hard. And then they get struck down seemingly out of nowhere.

All diseases are bad, but sometimes cancer feels like the most unjust. I come from a childhood background of comic books and superhero stories, so justice is a big theme. Folks like Amir and I are lucky to have access to opportunities to help people, and if we have an opportunity to help, how could we not take advantage of that opportunity when there’s a person in need? I don’t know if that was humanizing enough. I should have said something more about how I like baseball and beer, but you have to help people if they need help.

Stephanie: We like that. We got the comprehensive view: baseball, beer, and being a saint. I know how busy you are, so I’m appreciative and I know our community is as well every time you join us on a program like this.

I’d like to welcome Dr. Steinberg for being here. This is the first time we’re able to meet you and we’re happy to. Speaking of humanizing, you have many personal reasons why you’re in the work that you do. I read a poem about how it affects us all and it details a lot of your connection to cancer, including your own. Could you share a little bit about that connection and how that’s motivated you to do what you’re doing today?

I’d like to welcome Dr. Steinberg for being here. This is the first time we’re able to meet you and we’re happy to. Speaking of humanizing, you have many personal reasons why you’re in the work that you do. I read a poem about how it affects us all and it details a lot of your connection to cancer, including your own. Could you share a little bit about that connection and how that’s motivated you to do what you’re doing today?

Dr. Amir Steinberg: I was a senior in high school, reading comic books and watching baseball — all those things that Dr. Brody was alluding to, as we come from the same stock in that regard — when I came down with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. I had these big lymph nodes in my neck that started to grow early in my senior year.

I had never heard of MD Anderson Cancer Center before, even though I grew up in Houston. We had a family friend who recommended that we go there. I enrolled in a clinical trial, but I didn’t know what I was signing up for. My mom and I signed the paperwork when I was 17 years old. I did well. I completed all my treatment. Our family friend did my radiation. The care I received and the academic physician who took care of me inspired me to emulate his career, so that’s why I went into the field of oncology.

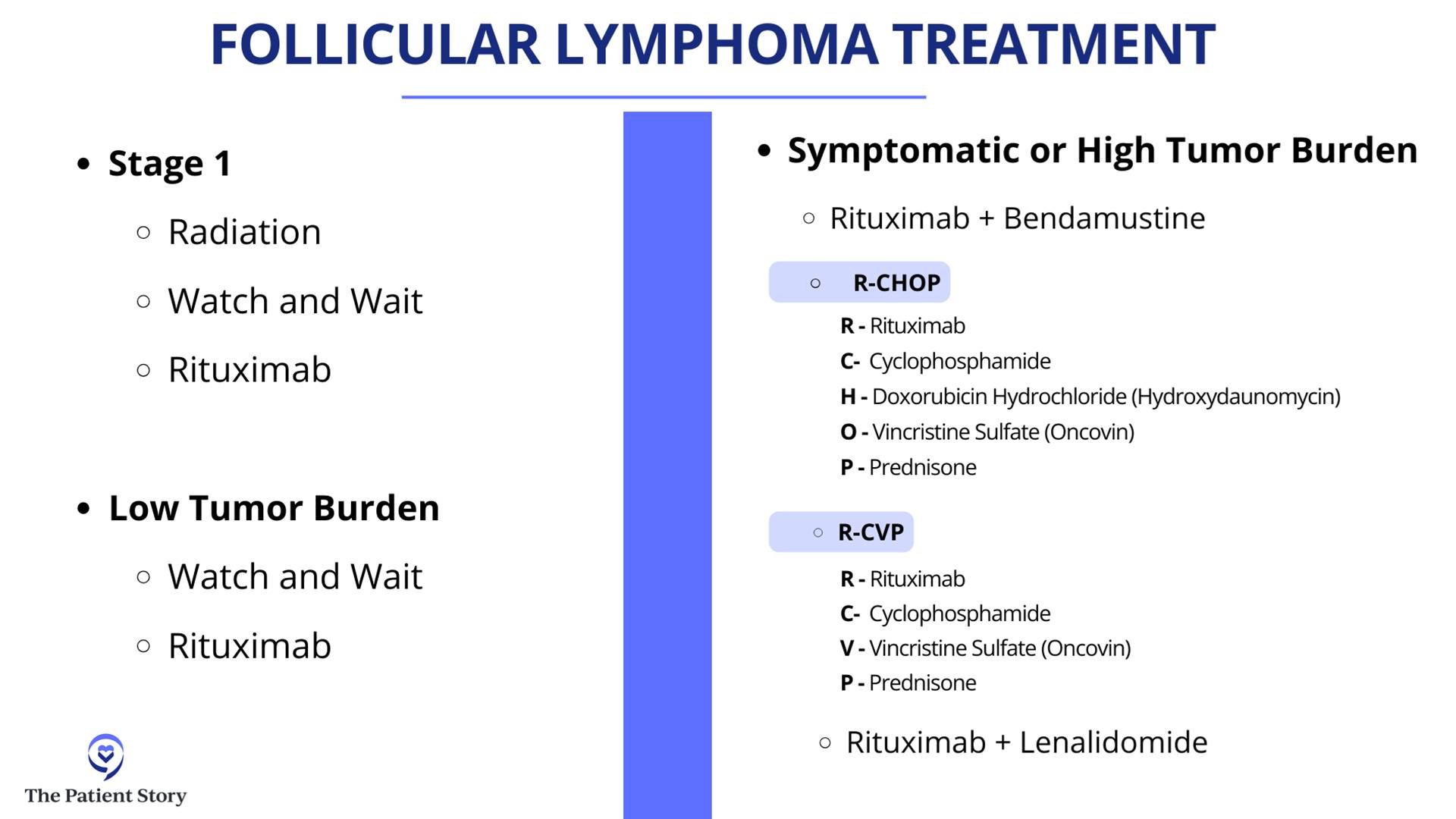

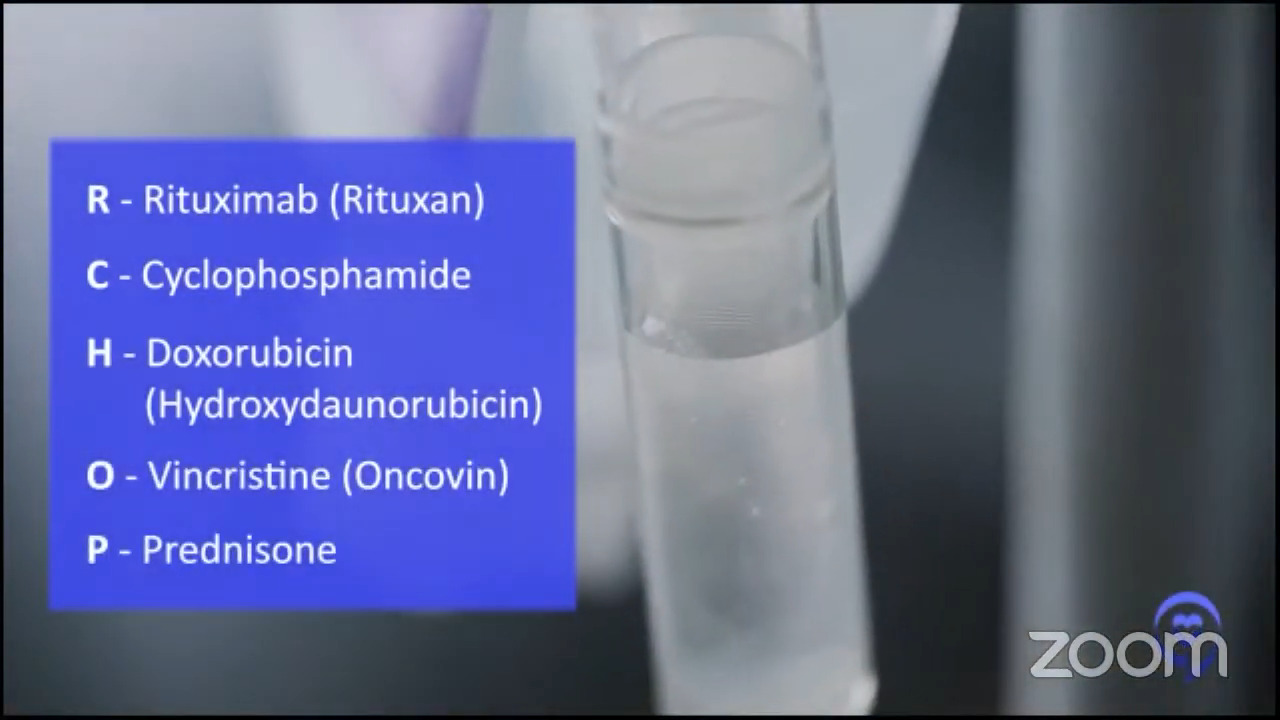

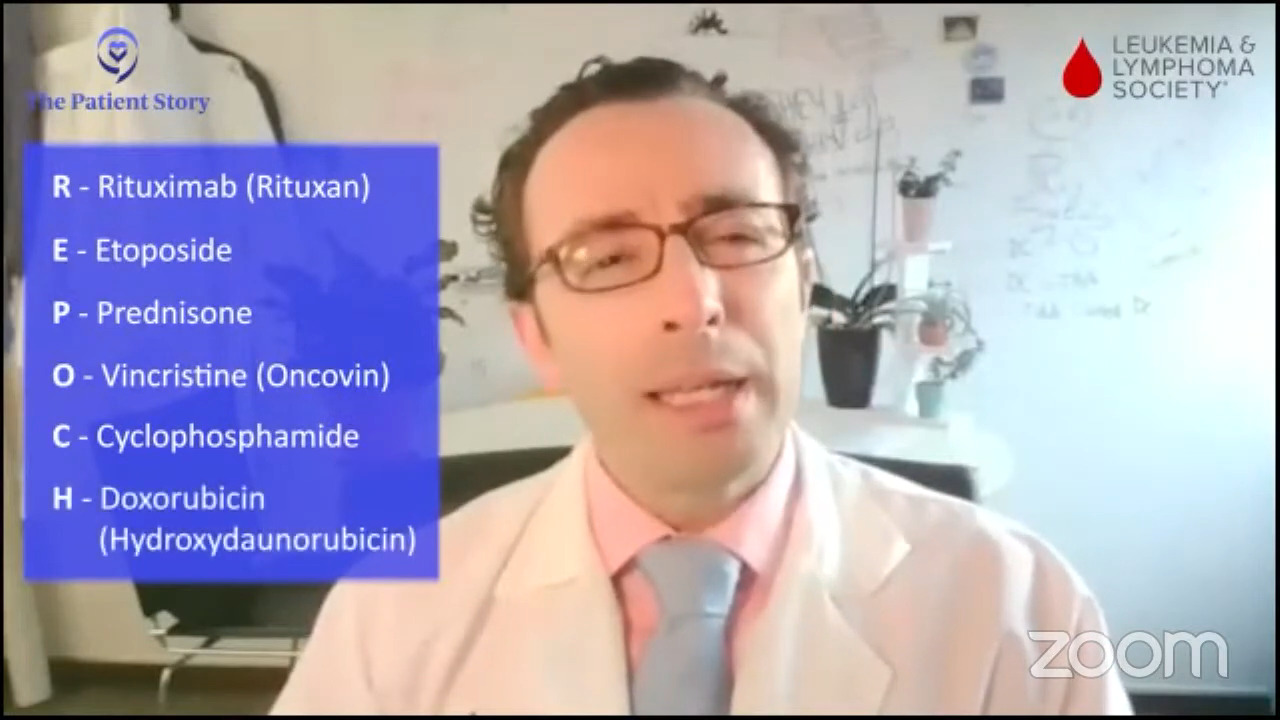

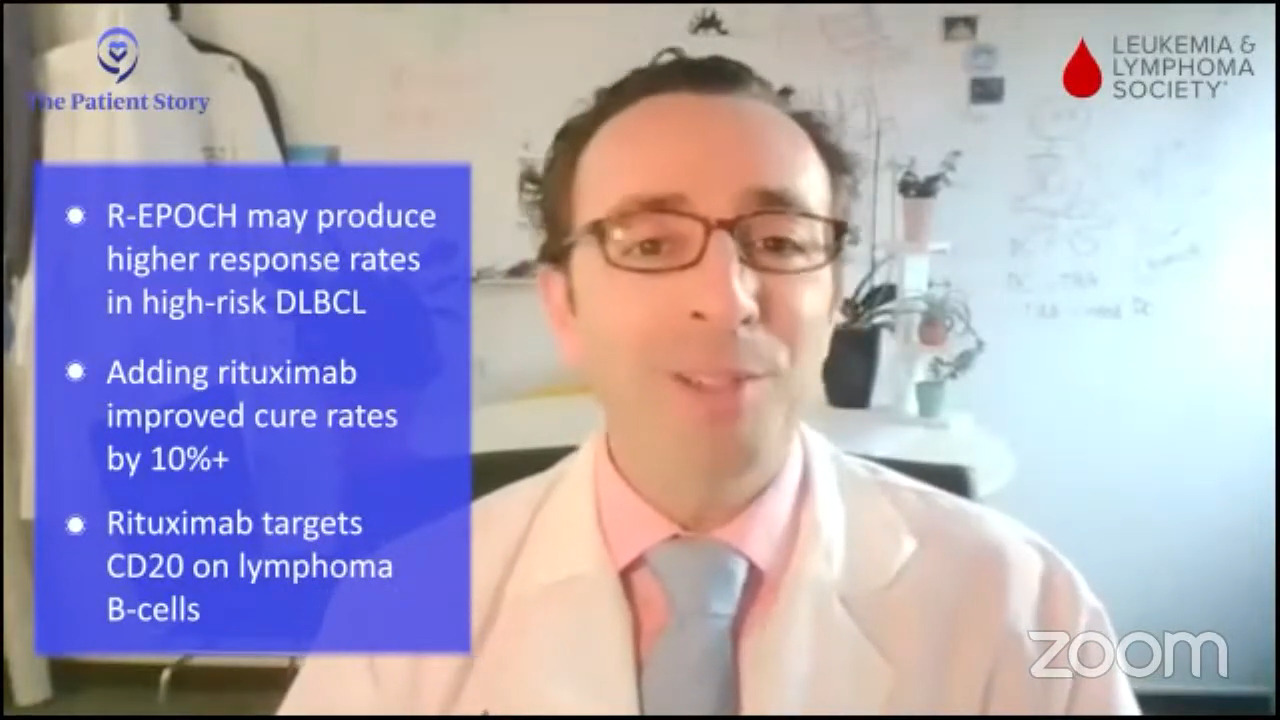

Over time, other family members came down with cancer as well, particularly lymphoma. My father was diagnosed with follicular lymphoma in his late 70s and, subsequently, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and then he was diagnosed again with follicular, so maybe that DLBCL might have been follicular lymphoma to begin with. Then my sister was diagnosed with gray zone lymphoma (GZL) a couple of years ago. She had chemotherapy. Stephanie, you mentioned that you got R-EPOCH and she got the same regimen as you. She was treated in Seattle, where she lives, and she’s doing fantastic now.

Cancer can affect anybody. Just like Dr. Brody was alluding to, we could be the healthiest people possible and yet cancer can still affect you — even if you didn’t smoke, ate healthy, or were a marathon runner.

Stephanie: It’s unfortunate, the number of connections to cancer there are. Thank you for joining us. I’m also very interested. I didn’t realize that you were a clinical trial participant at such a young age. We’ll be talking about clinical trials. We’ve talked over and over again about how unfriendly the term itself can be for people to hear. Our goal at The Patient Story is to try and help make it more accessible as a concept for people, so they can ask doctors like you about clinical trials.

We’ll jump right in with the basics. For the relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma population, we’re going to talk about some information that is going to go into clinical trials. Another thread is working with different kinds of doctors at different kinds of centers. Dr. Brody is at Mount Sinai, which is a huge academic center, and Dr. Steinberg, who is also an academic but also at a community center where you are all up to date on the latest. Also, you have referred people to see some specialists, like Dr. Brody, in some instances.

Conversations with Newly Diagnosed vs. Relapsed/Refractory

Stephanie: Dr. Brody, what’s the first conversation you have with newly diagnosed patients when describing the situation and likely treatment options versus when you have to talk to people who’ve already gone through at least one line of treatment?

Dr. Brody: Although relapsed/refractory DLBCL is an objectively worse conversation to have because our statistics are not as amazing, somehow it’s an easier discussion. There’s information overload during that first discussion. “Wait, I have lymphoma?” A newly diagnosed DLBCL patient is barely hearing you. The audience may be too young to remember, but Charlie Brown had a teacher who, whenever the teacher spoke, it was just, “Womp womp womp womp.” Very little can get in because they’re sitting there thinking, “Wait, what? I have what? I’ve never heard of lymphoma. Is that rare?”

The conversation has to be, “Here’s all the information, but you don’t need to memorize any of this.” I’m going to hit a couple of bullet points, which are the key points. The emphasis is to try to convert it as quickly as possible from a didactic doctor talking to a patient to hopefully a conversation. You have to keep interrupting. “All right, I spoke for 35 seconds. Do you have any questions about that part?” Usually, patients will still be a little too shell-shocked to even have questions, so I’ll say, “As soon as I walk out the door, you will think of some questions. Here’s what you need to do. Write them down there in the Notes app on your phone or a notebook, so you can come back next time and ask those questions.”

Whereas with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, this person has probably been clicking and learning for the past year, two, or three about lymphoma, so we can get down to the nitty-gritty a bit more. There’s a very different conversation with a newly diagnosed patient and a relapsed/refractory patient for the patient’s emotional experience of what they’re hearing.

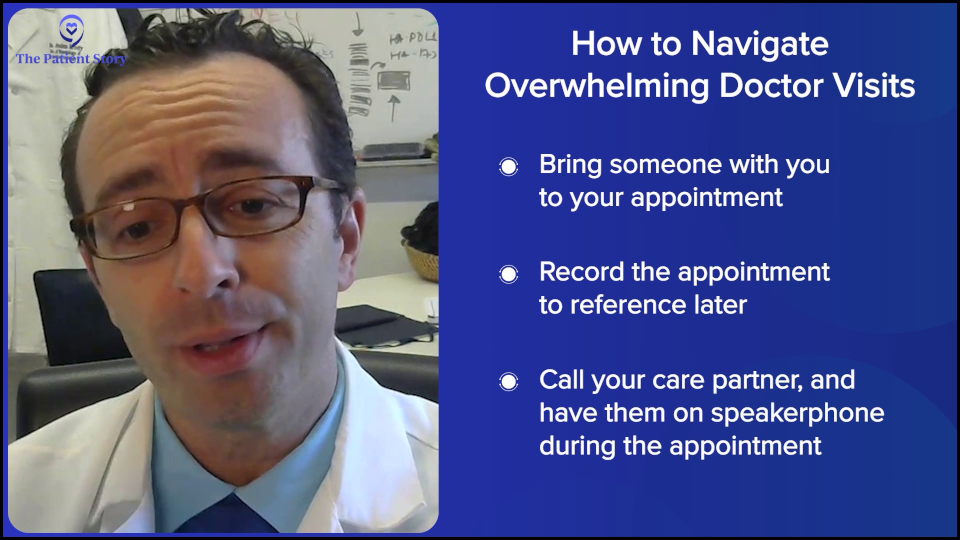

Stephanie: Thank you for that, Dr. Brody. I appreciate that you’re probably getting very similar questions, but that you provide space for people by saying that as soon as they walk out, it’s expected to have more questions; it happens. I know that patients have shared bringing somebody else to the appointment. You can ask the doctor. Sometimes they’ll let you record the appointment, so you can reference the notes later. I was a journalist and a researcher, so I loved information, but as a patient, it went in one ear and out the other for the very reasons that you explained.

Dr. Brody: It’s good to record it. If you didn’t think to bring a person with you, you can get someone on speakerphone as soon as the doctor sits down. Every doctor is open to that. No doctor gets offended or annoyed by recording or by a speakerphone. It’s all good.

Stephanie: That’s awesome to know. Thank you, Dr. Brody. Dr. Steinberg, how often are you talking to patients about treatment options? How different are the conversations between the newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory DLBCL?

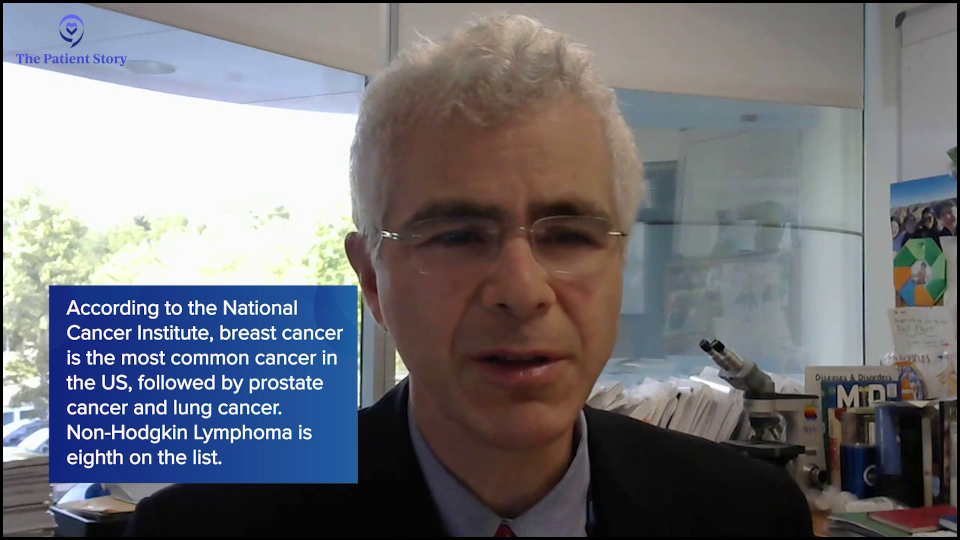

Dr. Steinberg: I see a little bit of 50/50 in terms of my patient population. I’ll have patients that are referred to me with lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes), or when I’m on service in the hospital, they’ll be worked up for some symptoms that they’re having because they’re rather sick. We have to start from scratch because a lot of newly diagnosed patients have never even heard of lymphoma before. The cancers they hear about are lung cancer, prostate cancer, and breast cancer, so even though lymphoma is fairly common in the cancer world, for whatever reason, it’s not as prominent. There’s a lot of education. You’re going to have to repeat yourself many times so patients can better understand, and we have to repeat it to their family members and their loved ones, as Dr. Brody was saying.

With the relapsed/refractory population, in some respects, it’s an easier conversation because you don’t have to start from scratch in terms of explaining what lymphoma is. A lot of them may have already read up on what the next steps are. During the course of their initial treatment, I’m sure a lot of them were worried that they wouldn’t respond, so what happens next? They may already come in to see me asking about transplant or CAR T-cell therapy.

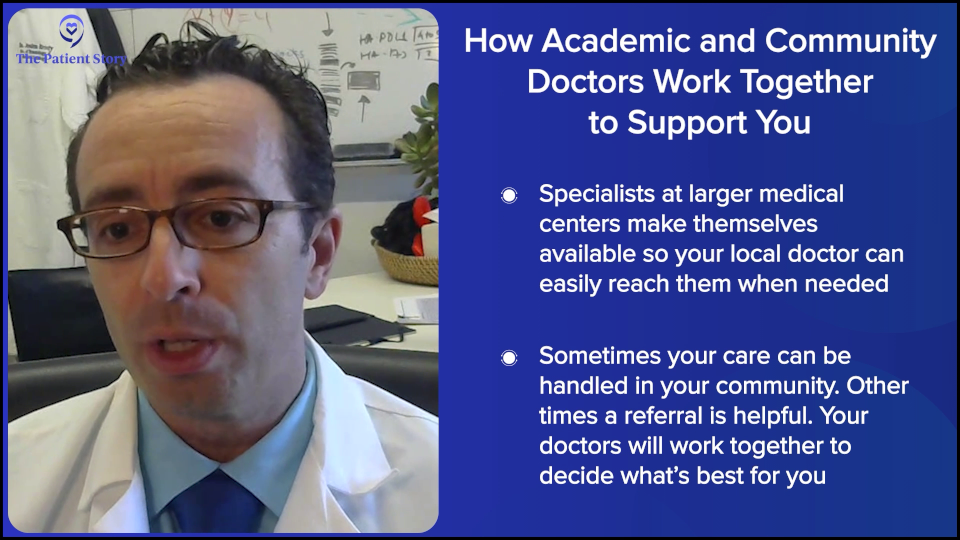

Stephanie: That makes perfect sense, also. I’m curious. For people who aren’t as familiar with Westchester Medical Center, can you describe the lymphoma program and what you usually advise patients to do when they’re relapsed/refractory? When do you refer them to an institution like Mount Sinai or introduce them to a specialist like Dr. Brody, and when do you treat them onsite at Westchester?

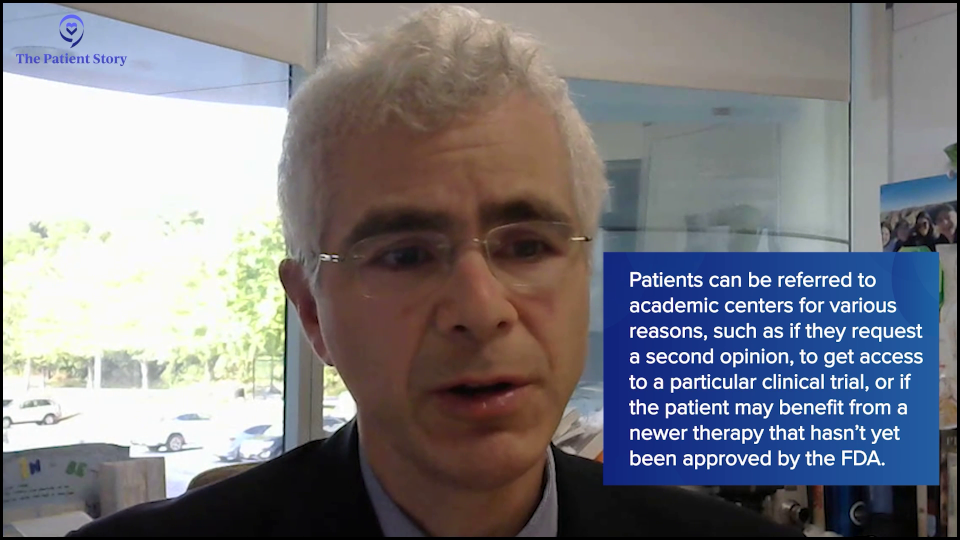

Dr. Steinberg: We have the resources here for cellular therapy, whether that’s CAR T-cell therapy or stem cell transplant. We have a couple of lymphoma studies here, but not to the same extent as Mount Sinai. There is a small group of doctors here who handle all the hematologic malignancies, whether that’s myeloma, leukemia, or lymphoma. Whereas at a big academic center like Mount Sinai, there are more disease-specific specialists, where you have someone who primarily treats leukemia or lymphoma, so that’s how we differ.

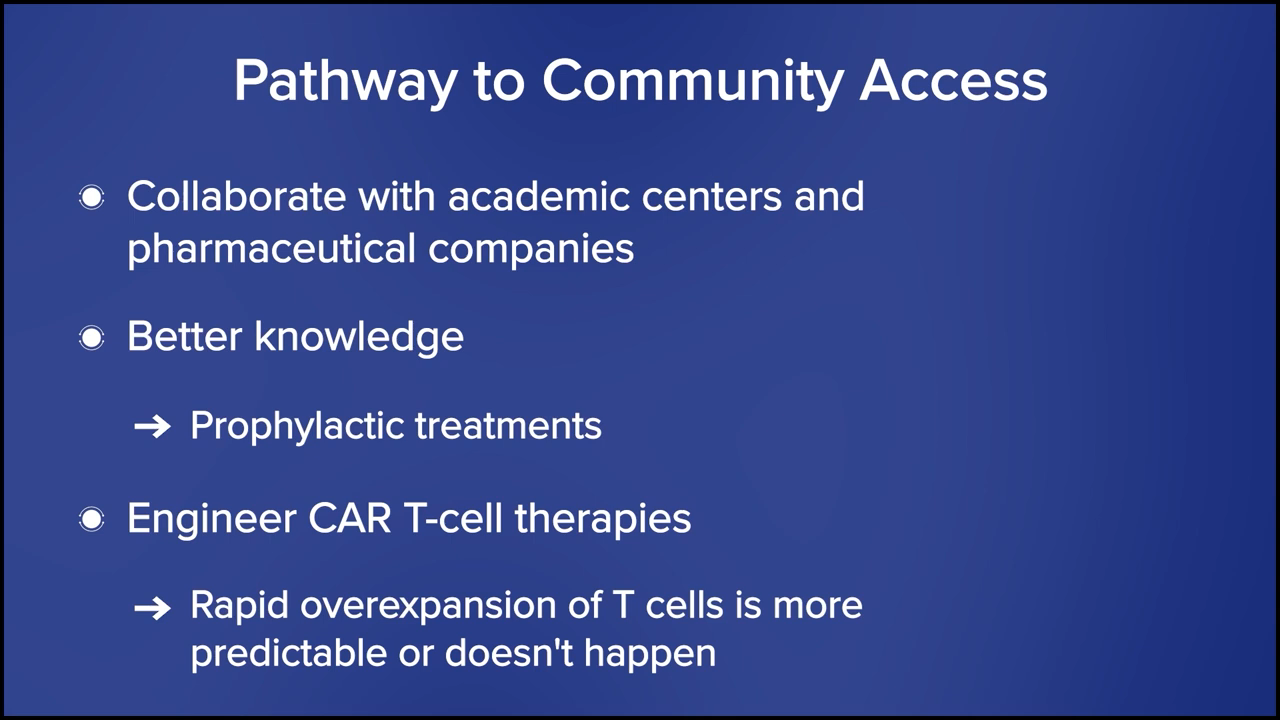

We work very closely with other community centers that lack inpatient chemotherapy and cellular therapy. We’re south of the Hudson Valley and north of that is Albany, so between Albany Medical College and University at Albany’s hospital and ours, there’s a lack of more cutting-edge or advanced clinical trials or cellular therapy. We sometimes serve as a bridge to those patients. If we don’t have a clinical trial that a patient is interested in, then I may connect with Dr. Brody or another center within Manhattan.

When do we do that? If a patient asks and wants another opinion, then I ask one of my former colleagues, like Dr. Brody, to see the patient. That’s the big trigger for me to refer to Manhattan. The other is if they’re not responding to their salvage chemotherapy. We try and bridge people to a transplant or CAR T-cell therapy, and if they’re just not responding at all and we think they might benefit from something new and different, then that’s when we’re going to refer out. Something that’s not available per se from the FDA alone.

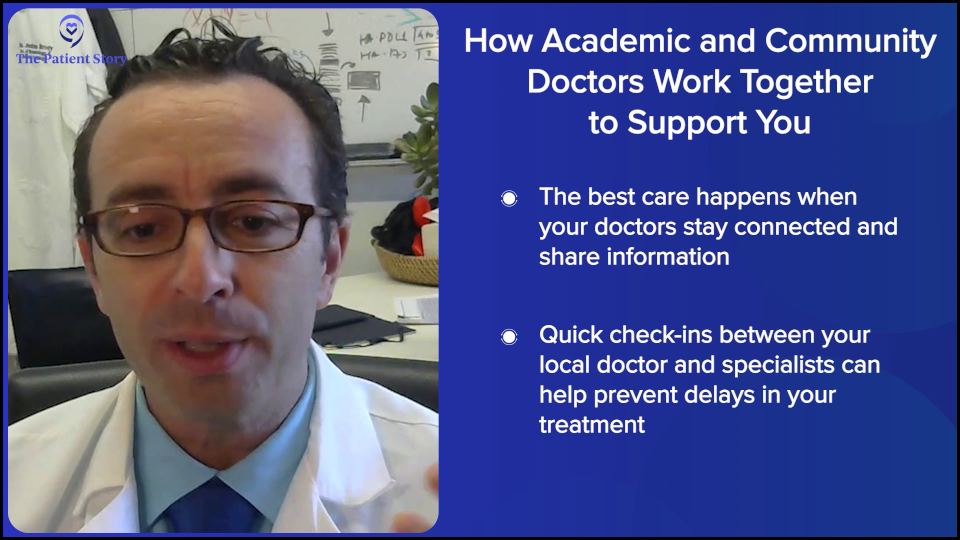

What Makes for a Good Partnership Between an Academic Center and a Community Practice?

Stephanie: What looks good in terms of communication and making it work, whether Dr. Steinberg gets with the smaller community centers that rely on Westchester or Dr. Brody, any of the partners you have in the community setting? What we’ve heard from patients sometimes is, “Do they talk to one another? Is it trickier if we have multiple healthcare centers involved?” I would love your insights on how to make this a great partnership.

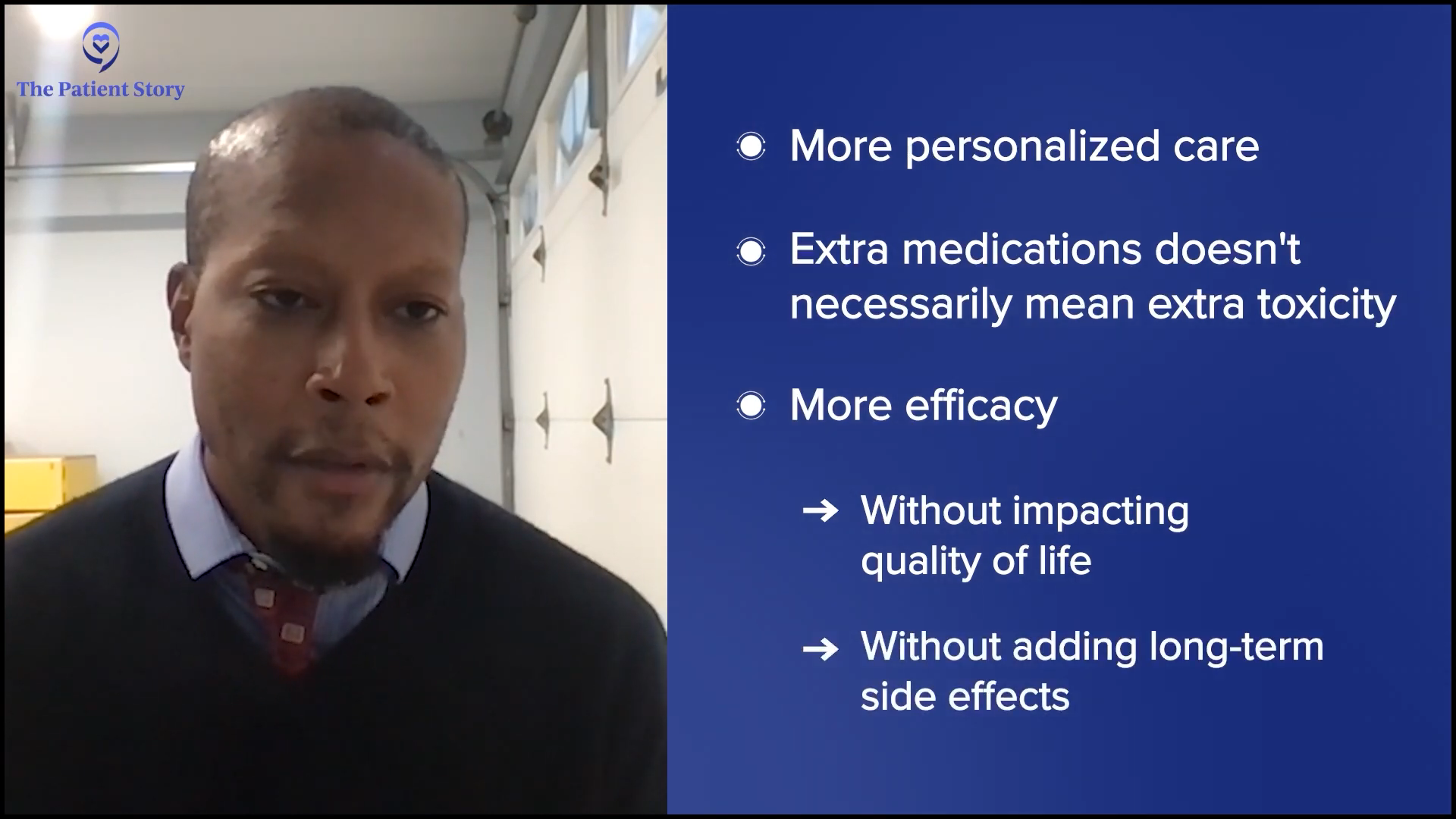

Dr. Brody: What you’re seeing here might be more the exception than the rule, and a good exception because Amir and I are buddies. In these large systems, we try to come up with a systematic way to have good communication and interaction. It turns out it’s mostly a personal way or nothing. Amir has my cell phone number, so as he’s seeing a patient, he can literally call me up right at that moment, and when I see it’s Amir and not some spam caller, I’ll pick it up and try to give him quick answers. If it’s about papers getting faxed and records getting signed, and “Oh, we can’t send those records there until that gets blessed,” then all of a sudden, the system starts to get more complicated, and delays build up at every level of it.

Unfortunately, it works best on a personal level, and the only way to improve upon that is to have more personalization and more interactions between community docs and academic docs. It would be great if we could get the systems working, but it seems that systems get more complicated, more cluttered, and more bureaucratic the more layers you add to them. If you’re a community doc, you need to have some academics that you have good access to and if you’re academic, you have to make yourself accessible. This is a huge obstacle for many. You have to make yourself accessible to as many docs in the community as possible.

Frequently, it’s not even about the patient having to be seen at the academic center. It’s just the community doc asking, “Hey, are you guys doing this the same way as before? Any new change updates? Or is there a critical trial that the patient needs to see you for?” And frequently, we say, “No, this patient would be as well served in the community as they would be here.” Or sometimes it’s, “Oh no, this is actually a high-risk patient for some subtle reasons and I would recommend having them at least get seen here once so they can hear about the options.” But that connection, unfortunately, seems like it works best when it’s personal.

Stephanie: Got it. That makes sense. Dr. Steinberg, any additions to that?

Dr. Steinberg: I agree. We know each other. We have each other’s phone numbers that we can text or we can email each other. One of the issues, for example, is that I have never even met a lot of people in the community who work near me, though we may communicate via email or phone calls. I wish we had a better connection and that I could see these doctors at some point in the future and see where they take care of patients.

Another barrier is the computer system. Epic, for example, is a computer system that a lot of hospitals use, where they have something called Care Everywhere and you can read what’s going on with the patients at another hospital. You just have to have a patient sign off to allow you to do that. My institution uses a different computer system, so they don’t have Care Everywhere, and what we use is not as prevalent as Epic, so that can create barriers in terms of communication.

Nonetheless, we try the best we can by talking to that clinician, sending records as best we can by email. Even the patients sometimes are our communicators. I had a patient who, when I mentioned, “We need a PET scan on you in about a month,” they said, “Okay, we’ll talk to our local doctor and have them order.” I trust this patient, so I feel like I don’t need to tell the referring doctor to order the scan because the patient will end up asking.

Stephanie: That’s great because a lot of times, patients will ask, “What can we do to help facilitate this?” It sounds like we can be quarterbacking some of the communication, if that’s helpful and can expedite some of this process. I appreciate that.

Having Conversations About Future Treatment Choices

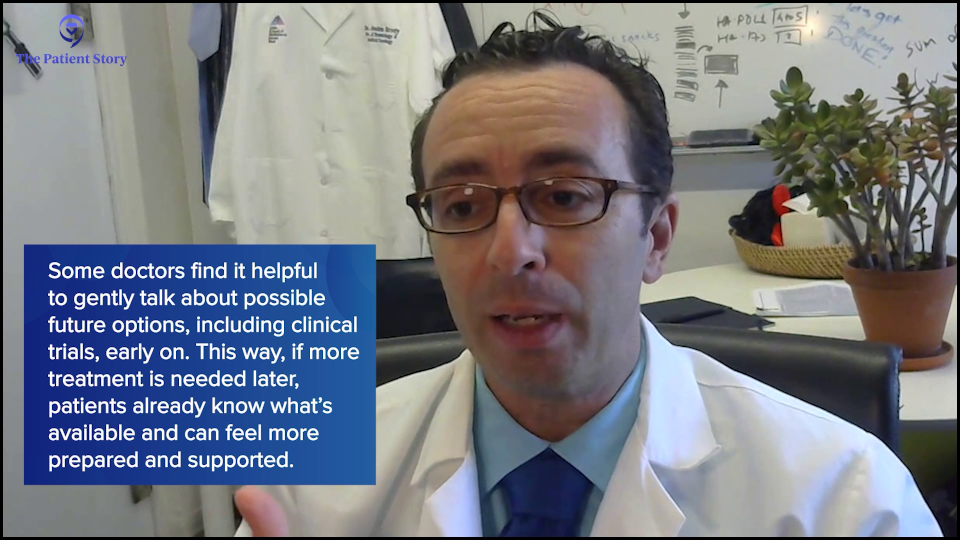

Stephanie: As we go into this idea that there are so many options right now, I would love to talk about one quick point. You both mentioned that when people are newly diagnosed, there’s so much information that they have to take in already, so it’s not an opportune time to add more. Once someone’s relapsed/refractory, is it a conversation that should have already happened? Where they’re told, “Hey, there’s a lot of development happening. Here are some clinical trials. If it ever gets to that point, know that there are options.” Is that something in your playbook? Or is that something you discuss only if that happens when it becomes a relapsed/refractory disease?

Dr. Brody: I’ll give an answer and it’s not a one-size-fits-all. Secretly, we tell people we don’t know the statistics. This is likely to occur, but you still don’t know. If it’s 70% likely to be cured, you’re wrong 30% of the time. But in our hearts, we may still have our suspicions, though. “This one feels higher risk to me.” For the ones we are worried about, you definitely don’t want to have these more difficult conversations all of a sudden, especially if they’re a newly diagnosed patient.

You can set that up, ideally multiple times. “Hey, we’re going to get a scan. If the scan looks great, then great. You can come back in six months. If the scan doesn’t look good, here’s how it might go.” If you have the luxury to set that up a few times, then if the scan looks great, you just wasted a minute of their time. And if it didn’t look great, now they’ve heard about this a few times, so it’s a little less shocking on whatever fraction of folks when you actually have to have that more serious discussion.

I think it’s extremely helpful to set it up. “If it goes well, then great. There’s nothing you need to think about. If it doesn’t go well, here are some things we are going to talk about. I’m not going to give you the details now. We’re going to talk about this. We’re going to talk about trials. We’re going to talk about some other options.”

Dr. Steinberg: I agree with Dr. Brody’s sentiments in that regard. To be honest, for me, part of it is also guiding them on what to plan for in the future based on their prognosis. Let’s say a Hodgkin lymphoma patient may have a better prognosis than someone with other lymphomas. I may be less likely to talk about what treatments to give them if they have a recurrence. Whereas if they have another kind of lymphoma that the statistics don’t favor as much as an average — not that specific patient, but just on average — I might mention to them, “By chance, if this happens to come back, we do have other great therapies that we can offer you, including this and this.”

Outlining Treatment Options for Relapsed/Refractory DLBCL

Stephanie: Now we can dive into the actual treatment conversation. Let’s talk about how you set up the conversation for people whose disease is refractory or they’ve relapsed. Dr. Brody, what is the first conversation? What are the considerations in laying out treatment options in terms of what’s already out there and approved?

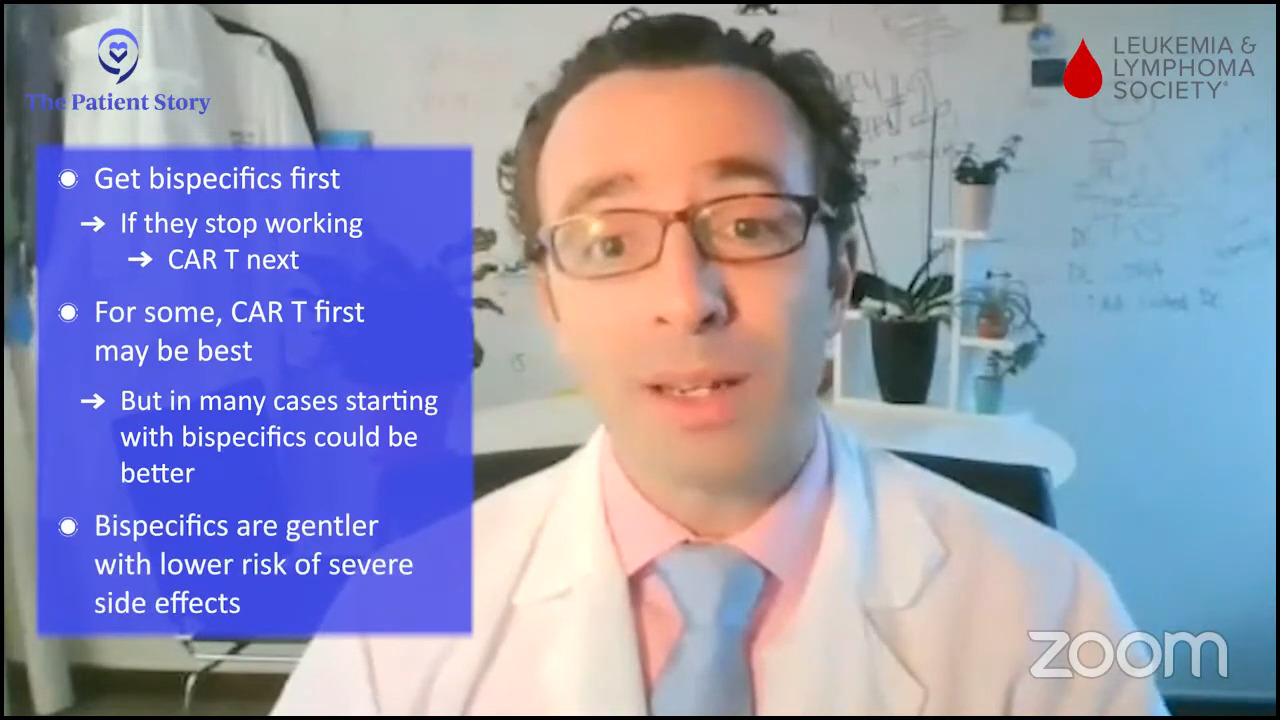

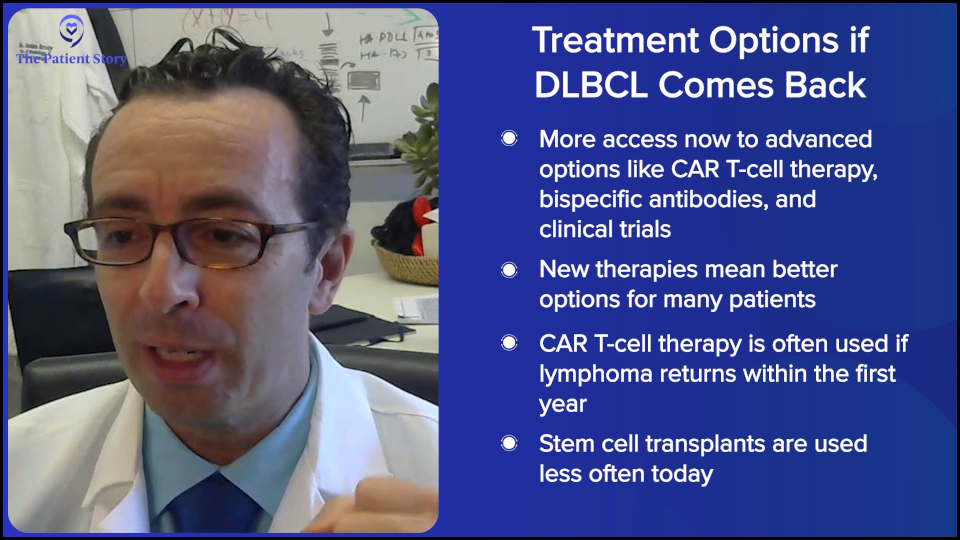

Dr. Brody: Folks who think that oncologists don’t have silly things to say haven’t been around oncologists much. There’s a silly expression we say: “A lot more was known about that a few years ago,” meaning that we had clearer answers 10 years ago. Now they’re less clear. That sounds bad, but it’s very good.

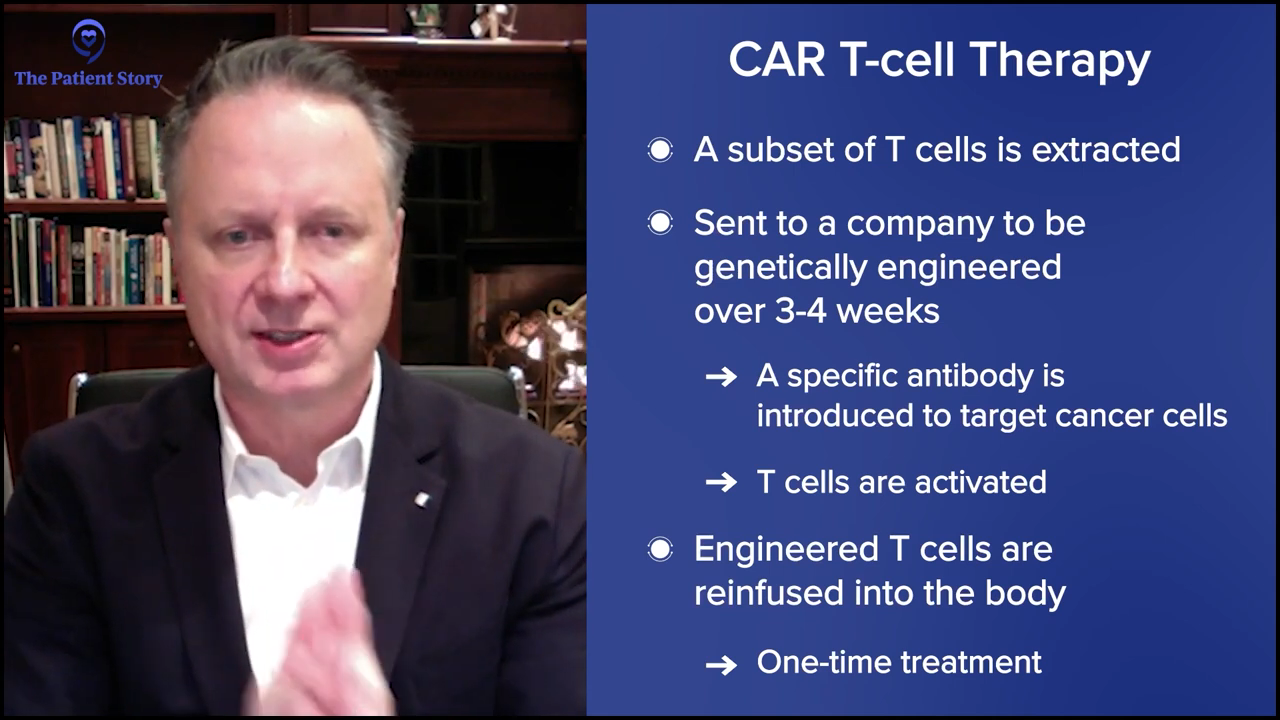

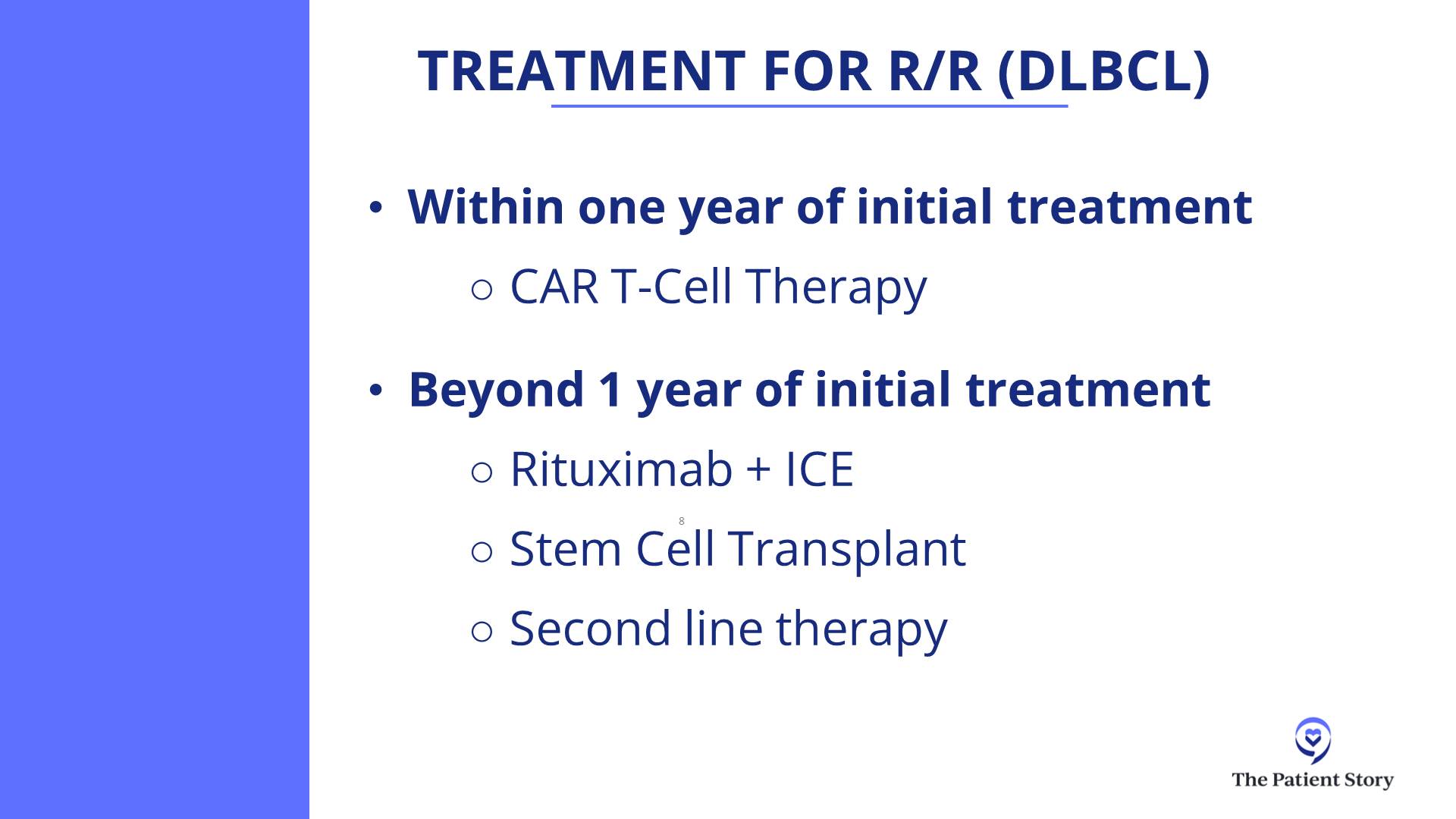

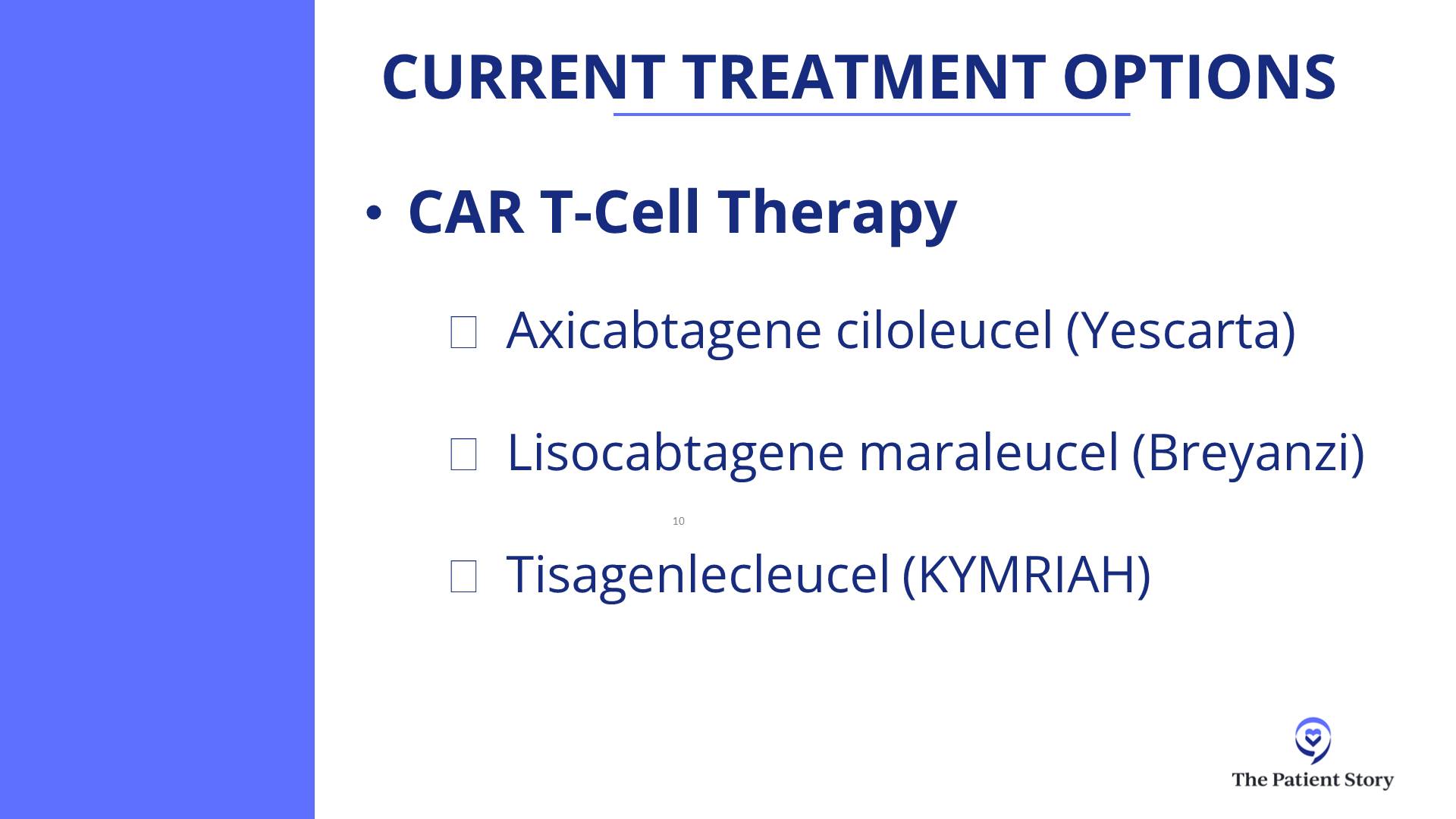

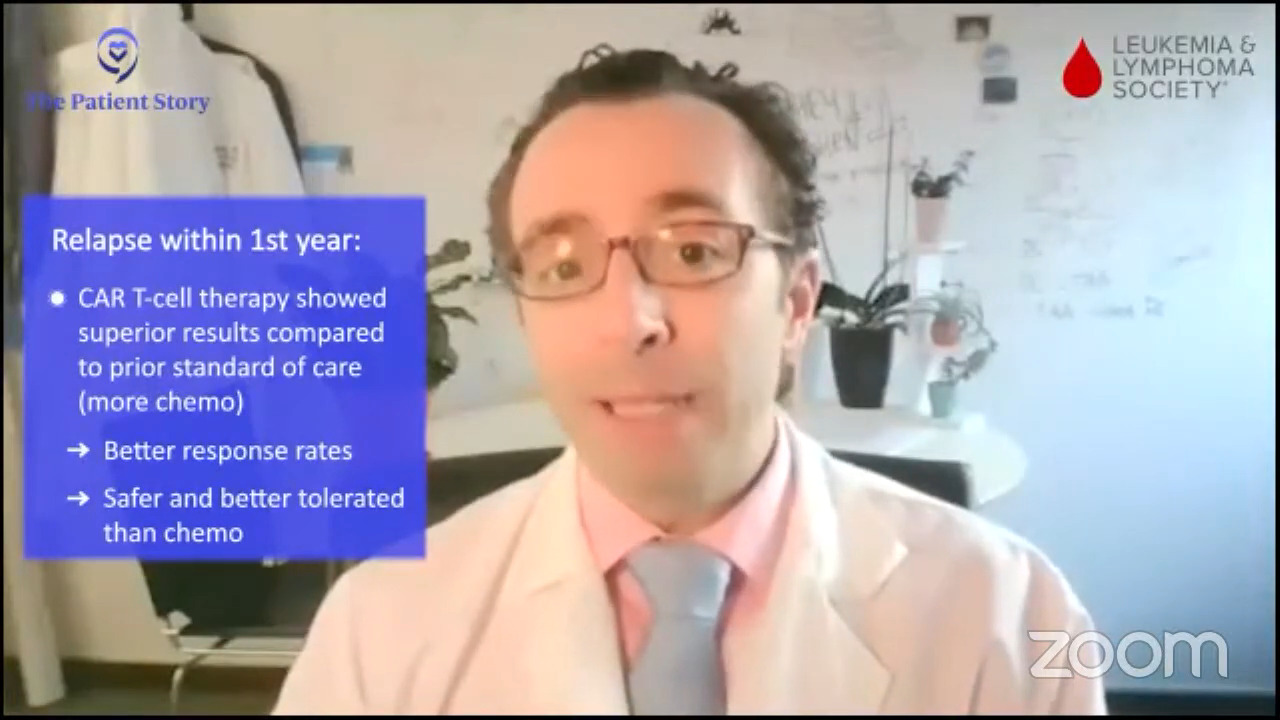

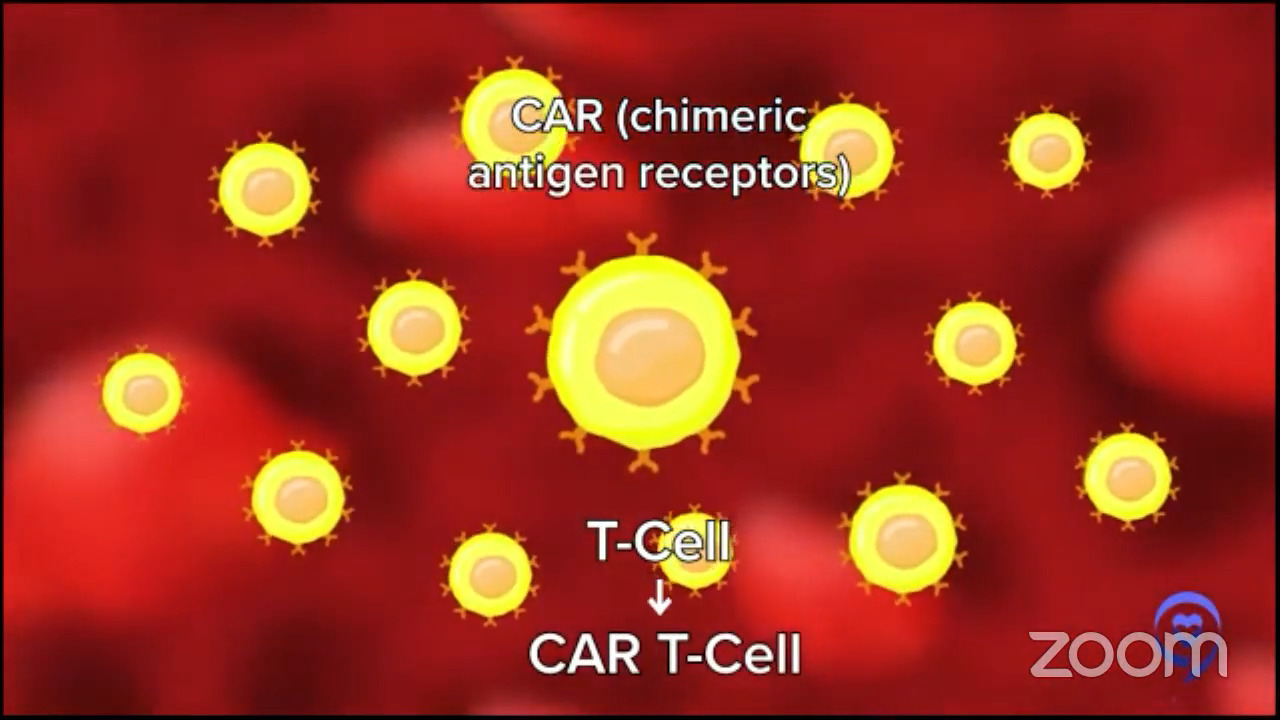

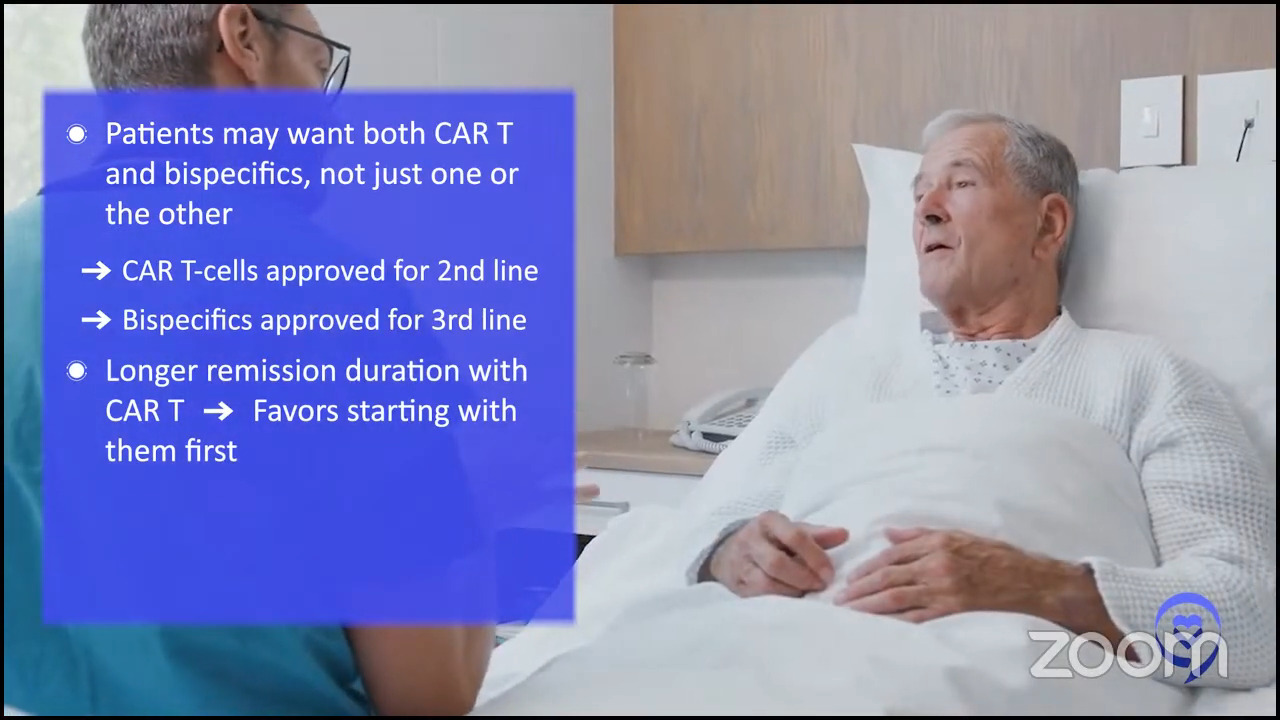

If you asked me this exact question two years ago, we would say, “Oh, it’s a fairly simple algorithm. If people relapse with DLBCL within 12 months of finishing their front-line chemo, the right and best answer is CAR T-cell therapy,” and it is for the vast majority of patients. Most patients could be eligible for CAR T-cell therapy, but not everyone, so that’s the right second-line treatment for early relapsing patients.

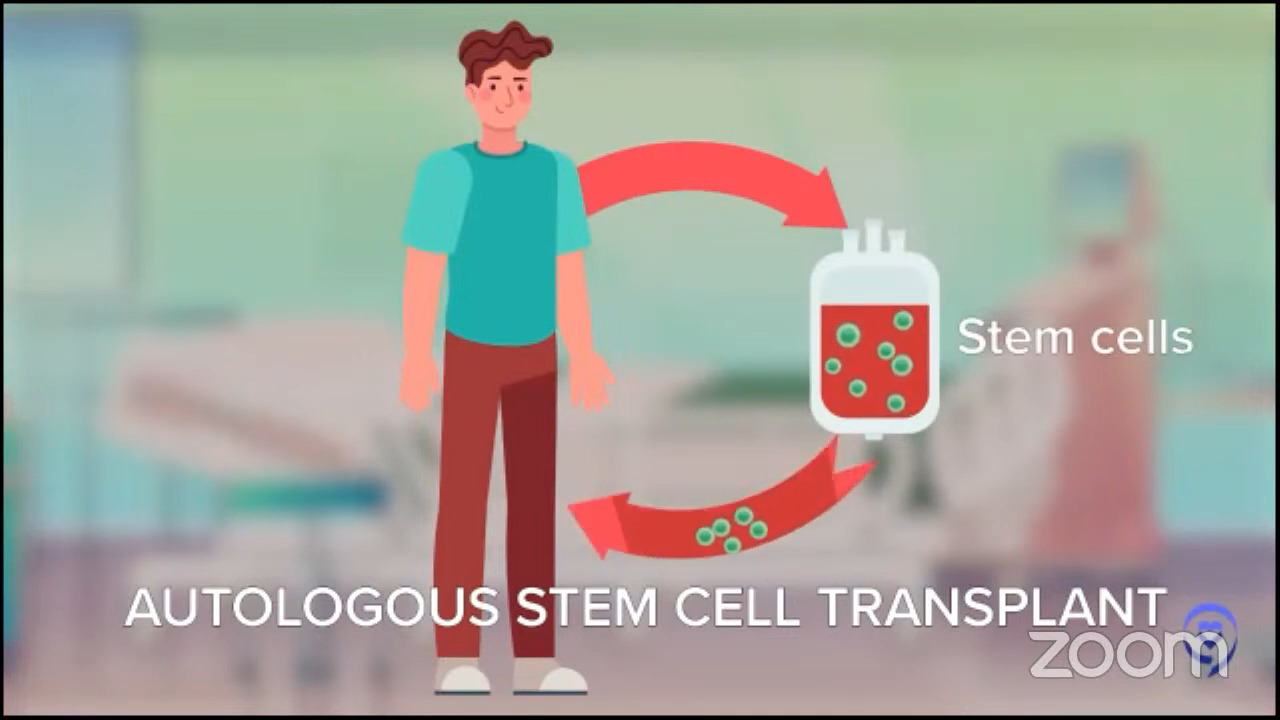

For later relapsing patients, it was a little more confusing. In 1994, we had a big trial proving that an autologous stem cell transplant, after some more platinum chemotherapy, was the right answer. But the field has evolved so much since then. Even though no one has rewritten that textbook, we don’t all believe that that textbook is necessarily the best way to go.

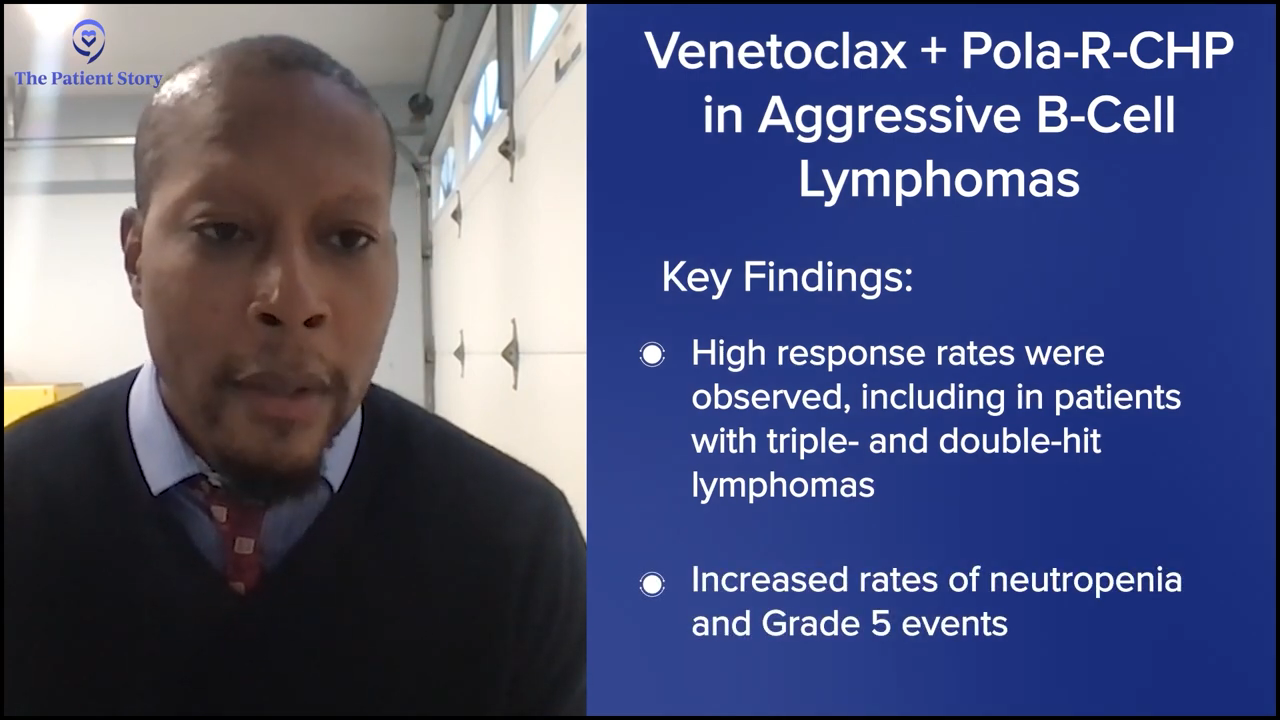

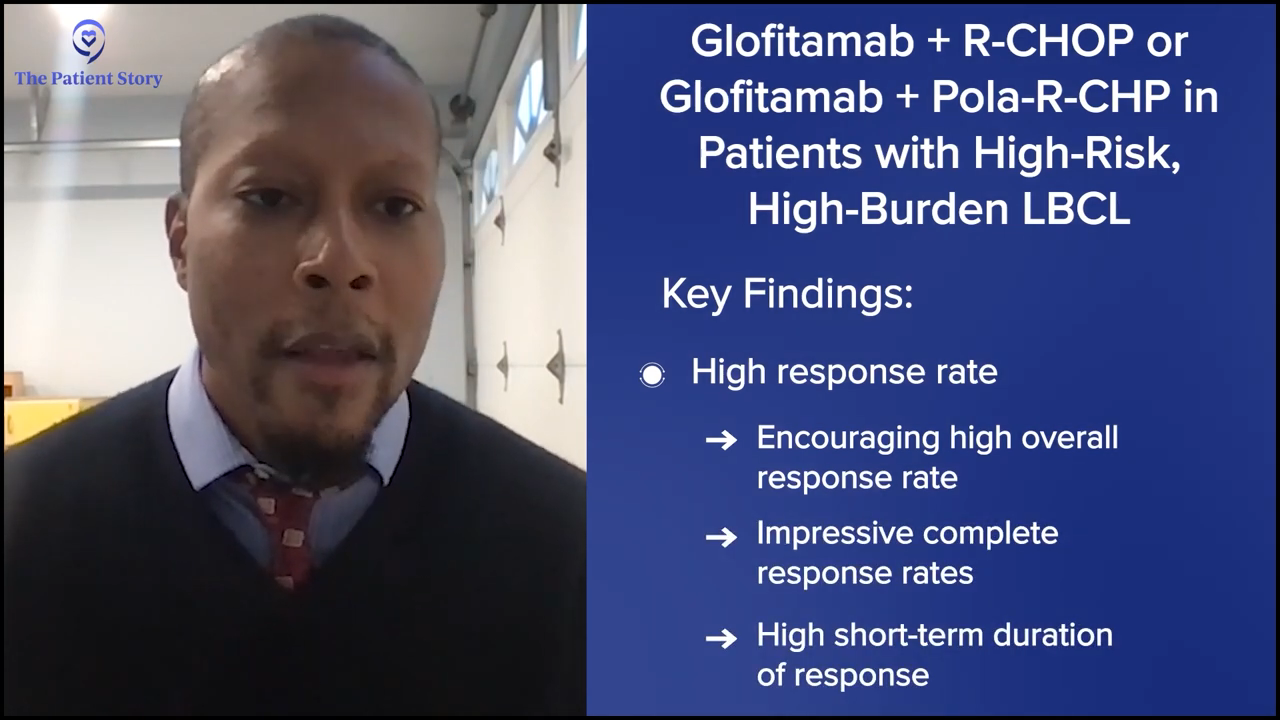

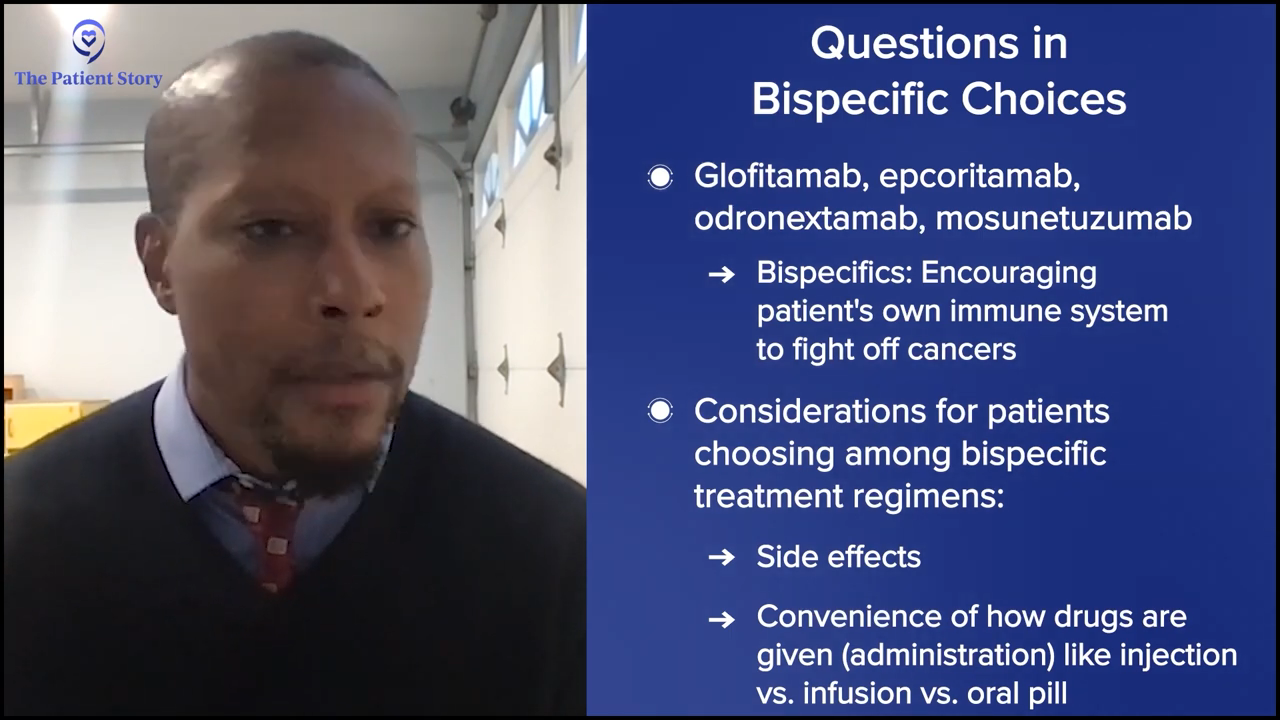

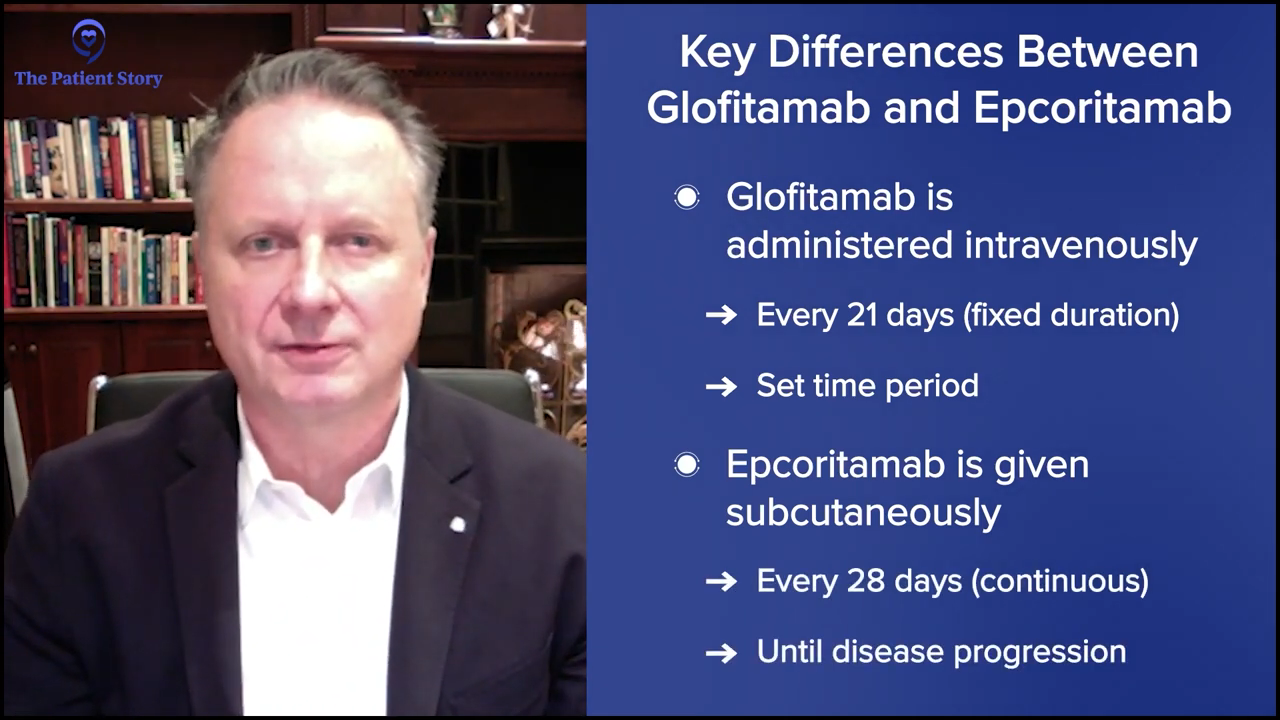

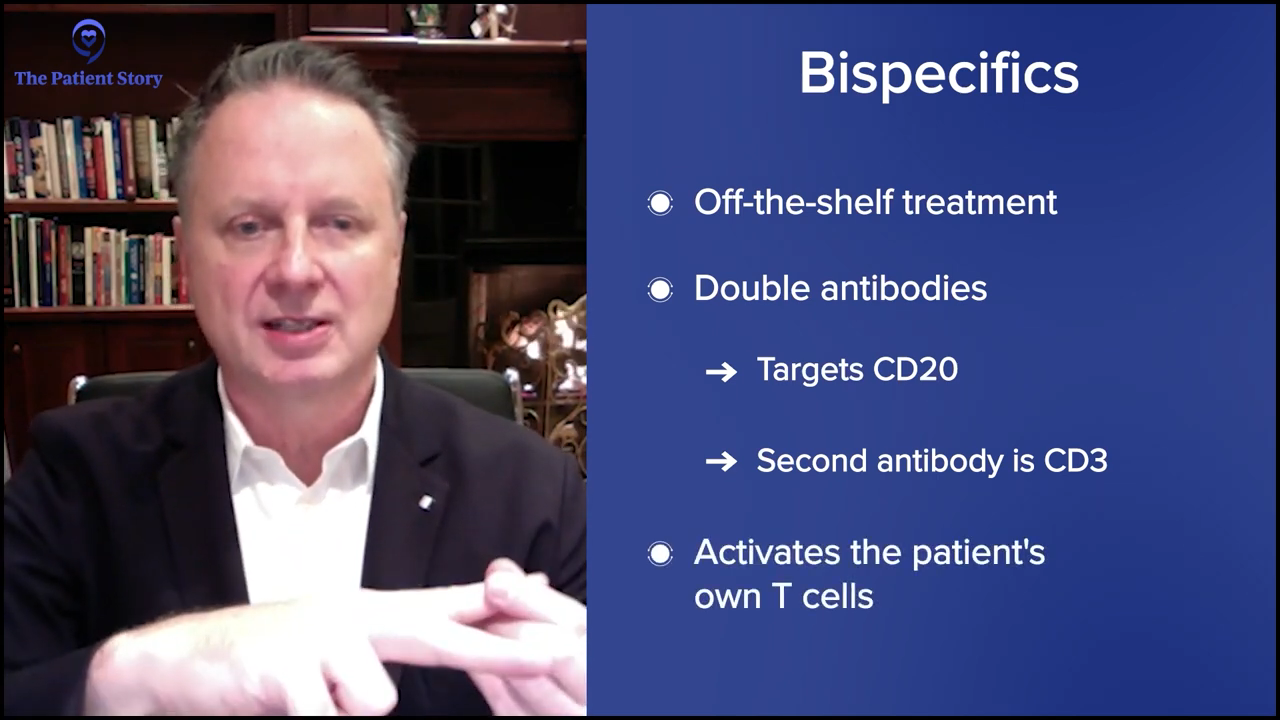

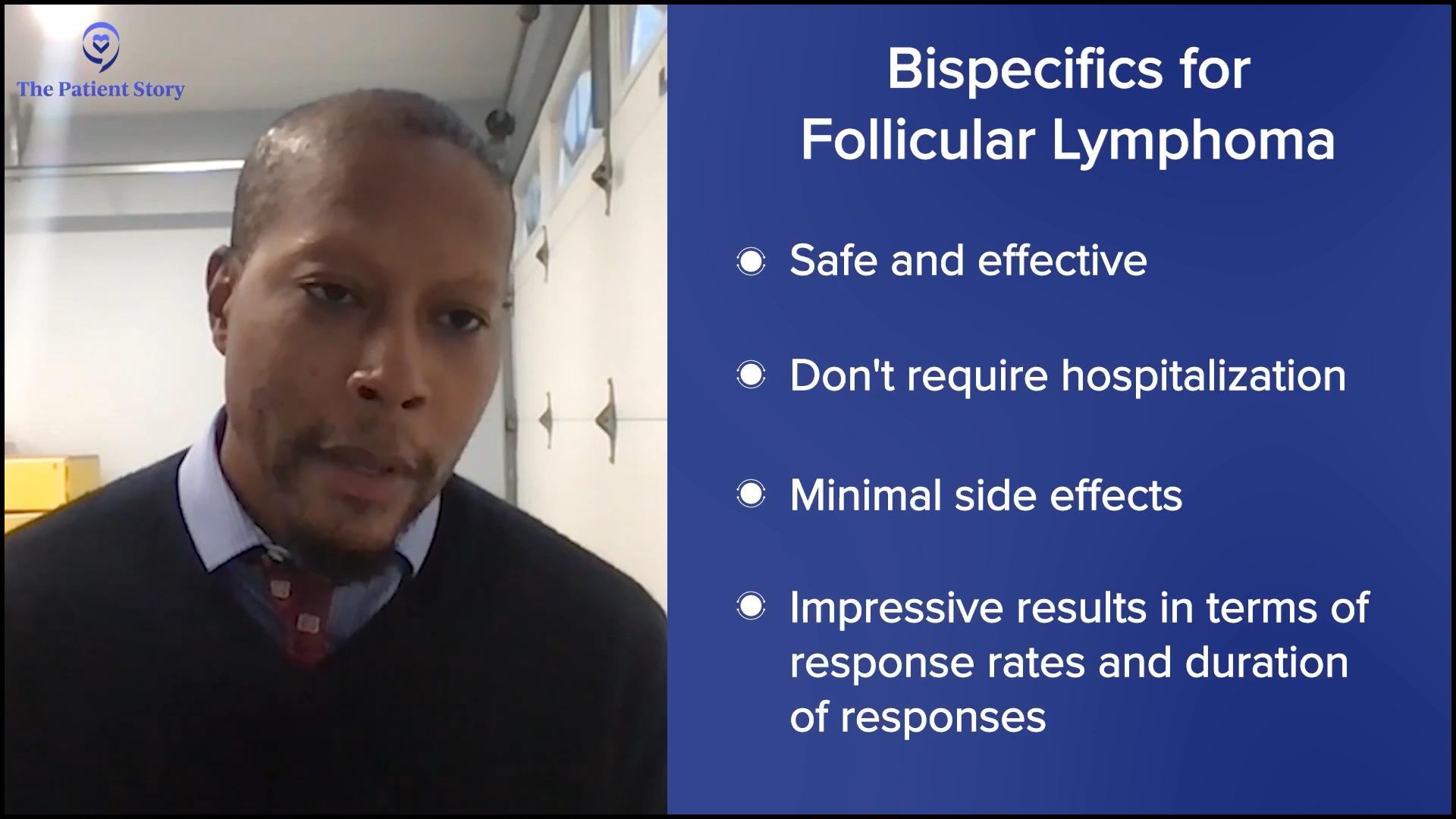

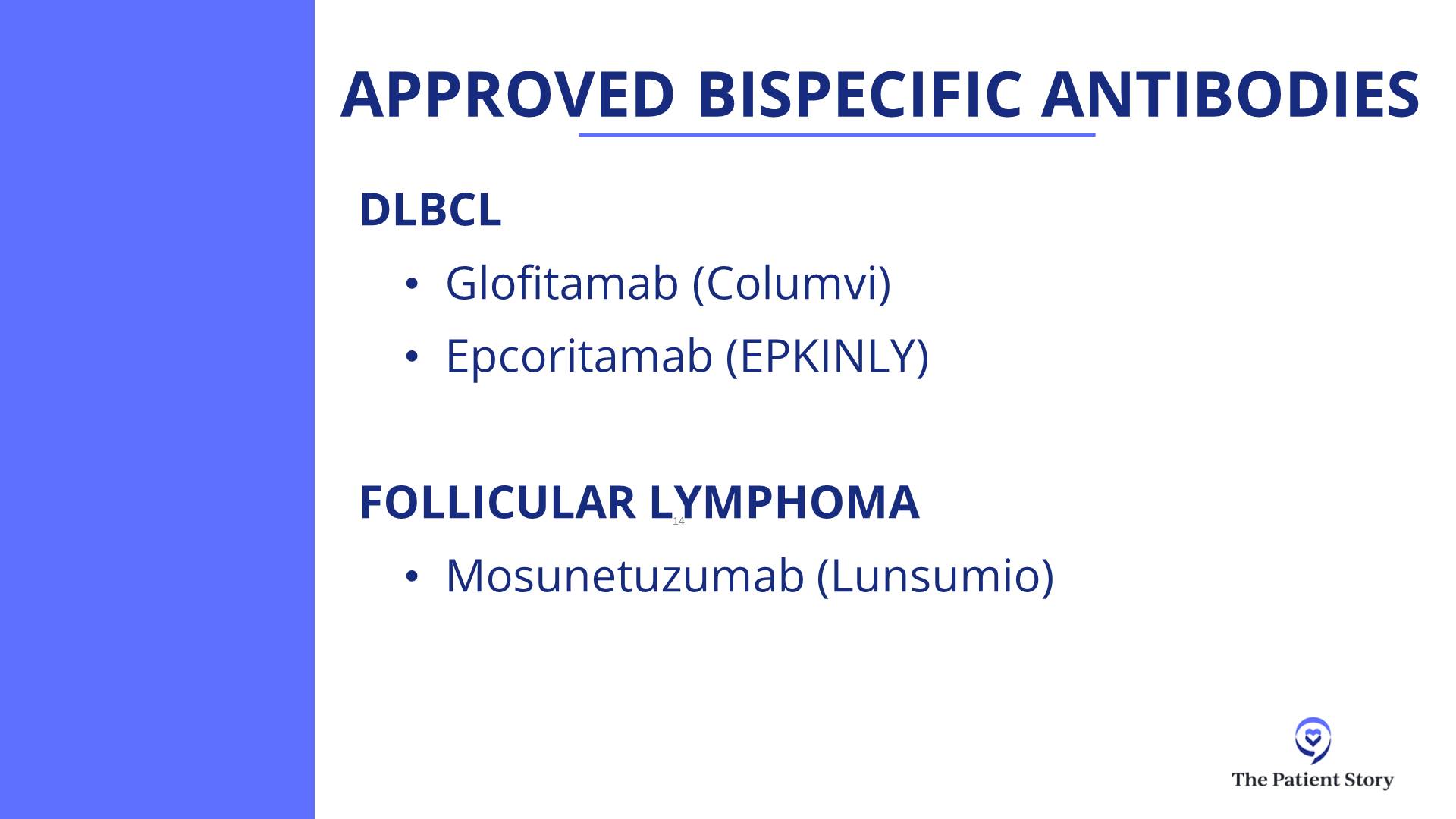

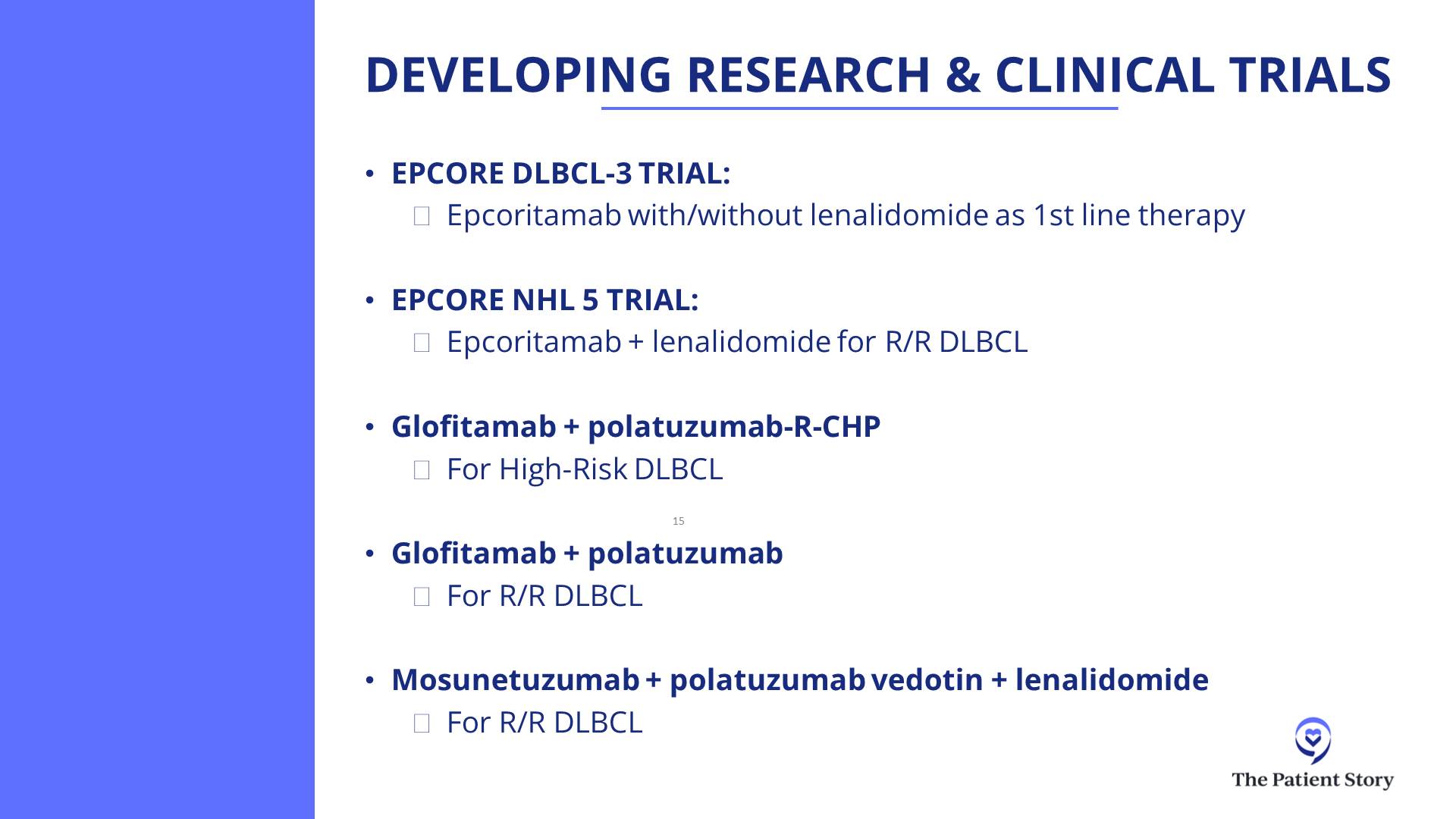

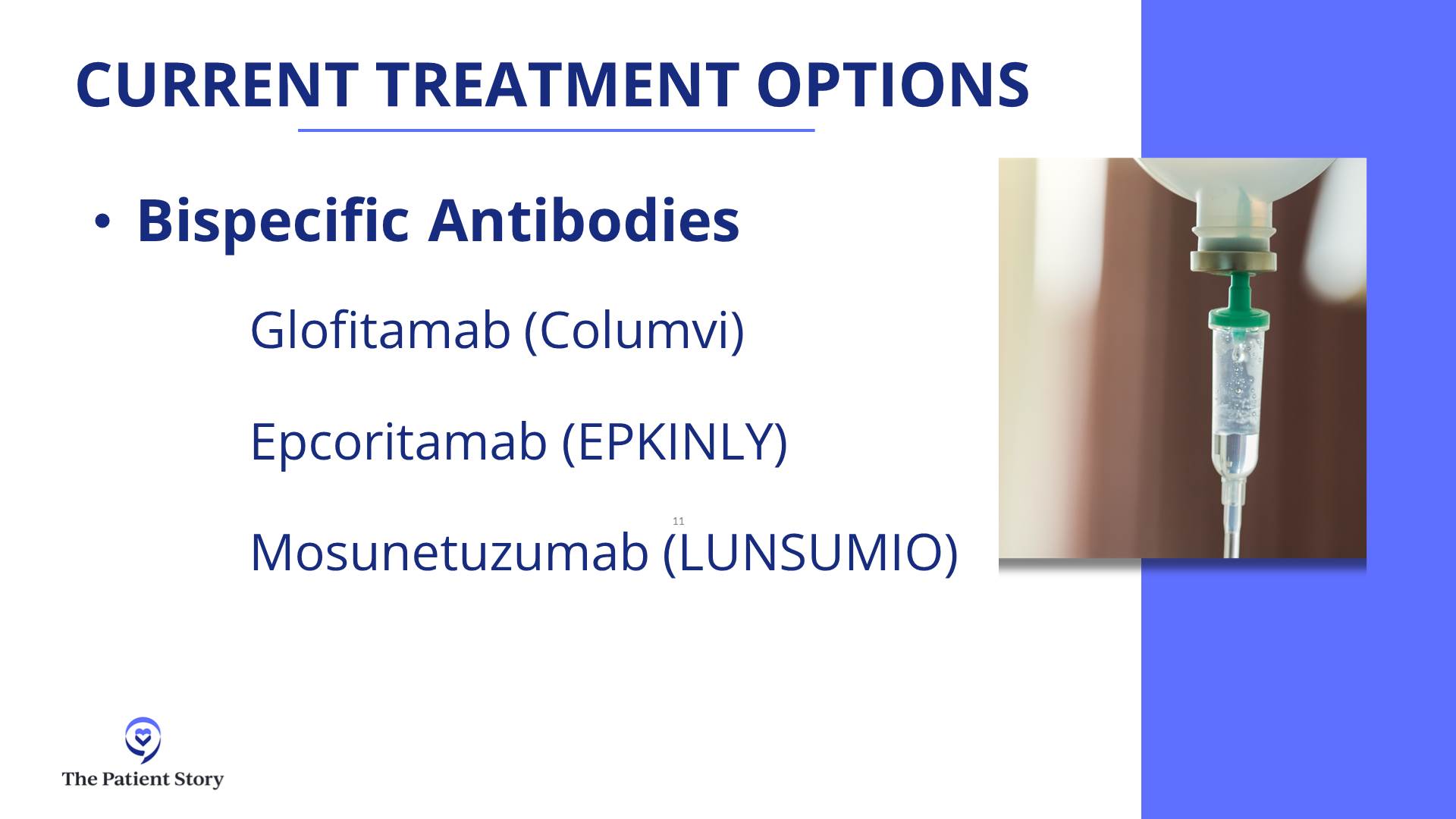

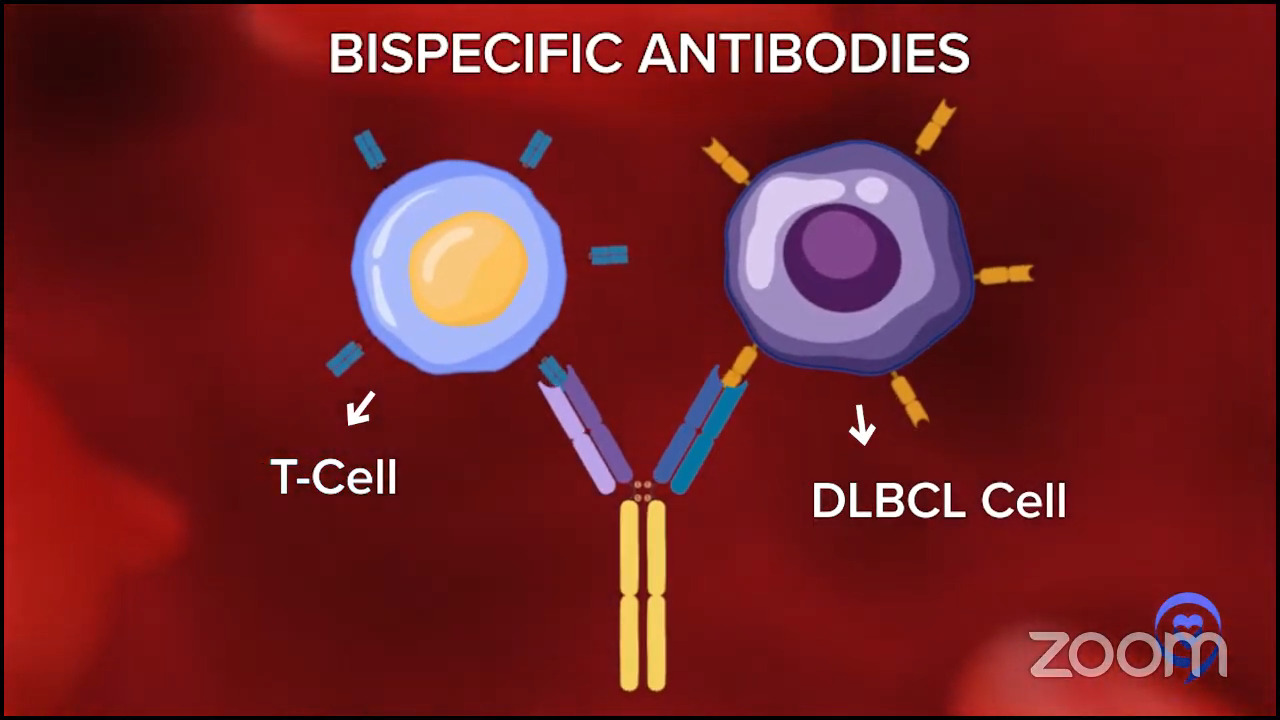

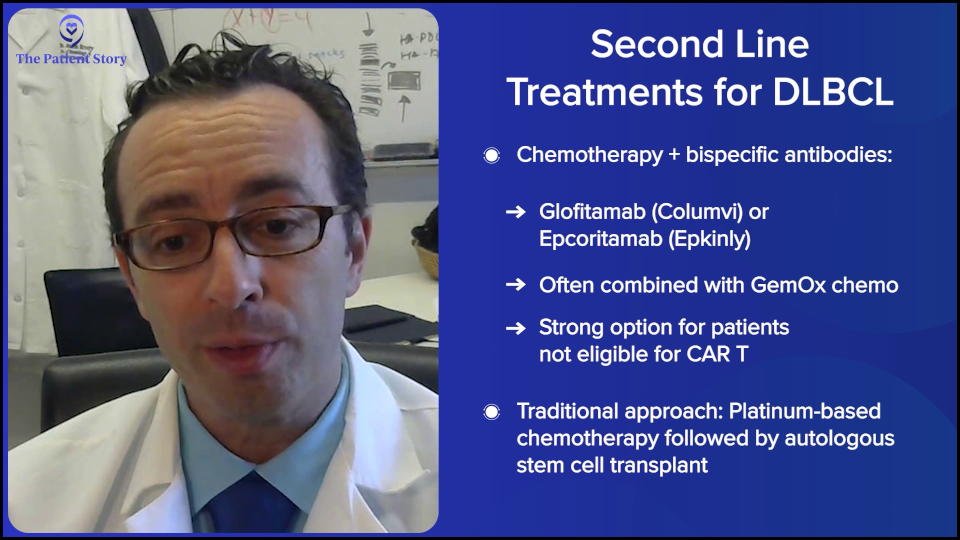

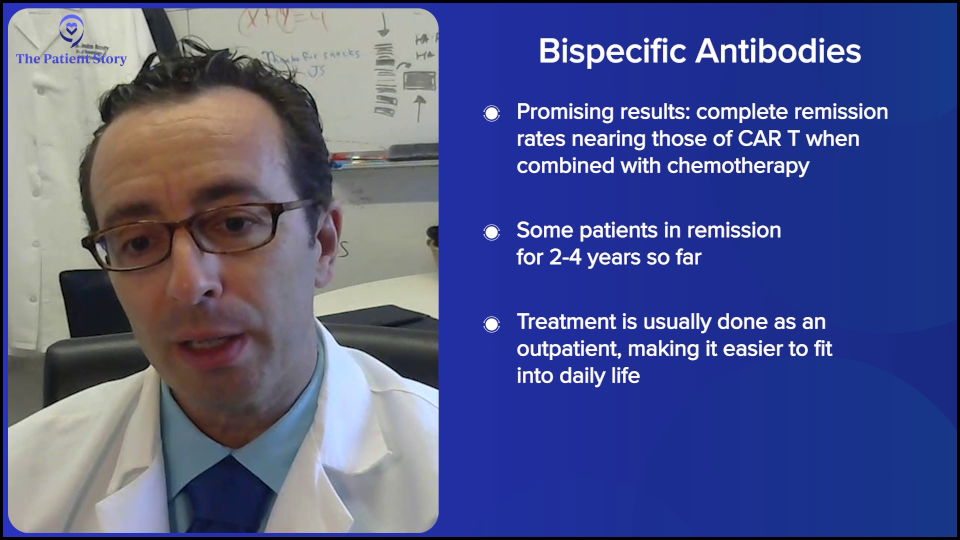

In 2024, those answers have evolved even more to make it even a bit more complex, but in a good way, because if you’re getting more options, then that can only be a good thing. People would rather have a clear answer. But they would rather have better therapies and better options. We have some remarkable data that adding bispecific antibodies to chemotherapy for patients in second- or third-line has a huge benefit in overall survival and progression-free survival.

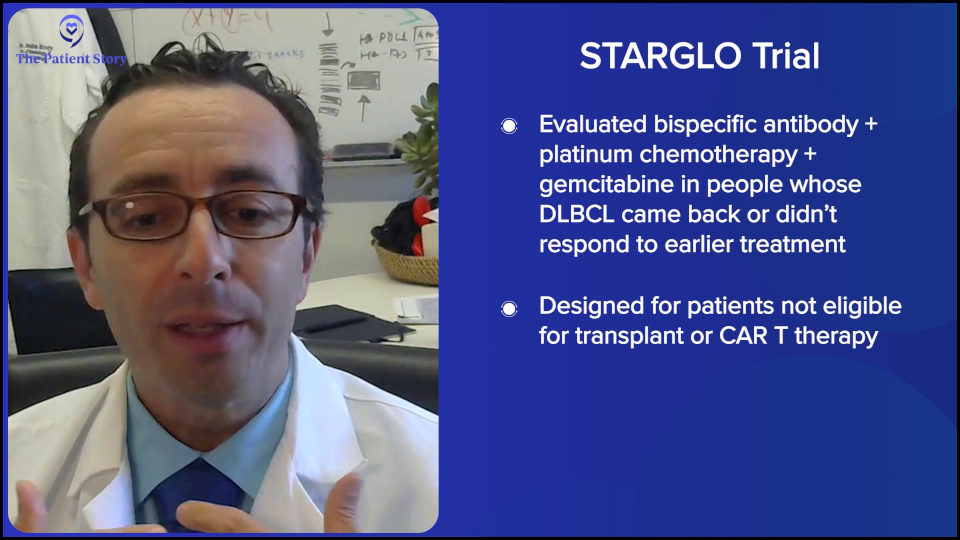

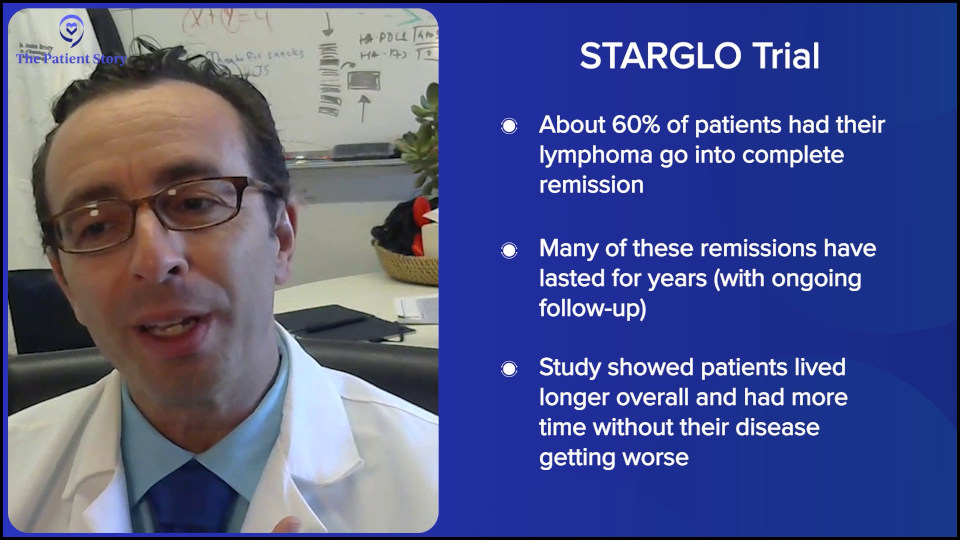

There are a few studies like this, but the largest randomized study is the STARGLO trial. The study showed that the combination of bispecific antibody, platinum chemotherapy, and gemcitabine chemotherapy seems to put the majority of people into complete remission — about 60% — and many of those remission patients seem to have durable remissions for years, though we need more follow-up. The way that trial was written is that it’s only supposed to be for people who weren’t eligible for transplant or CAR T-cell therapy. But there’s little nuance now because there’s a gray zone of who exactly is eligible for CAR T-cell therapy, so now we have a more nuanced conversation.

Here, if you have relapsed within the first year, CAR T-cell therapy is probably the right answer for you. If you relapse later, it might be chemotherapy, maybe plus a bispecific antibody. But even for people who relapse in the first year or in their third line, there is great evidence for bispecific antibody plus chemotherapy. Overall, it certainly seems to be a bit safer than transplant, maybe even safer than CAR T-cell therapy, and it’s a lot more accessible to folks who are being treated in the community when they don’t have a CAR T-cell therapy center nearby. The contribution of bispecific antibodies plus chemotherapy is a huge advance. All of these are versions of immunotherapies — CAR T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies — but there’s still a rapid evolution over the past few years.

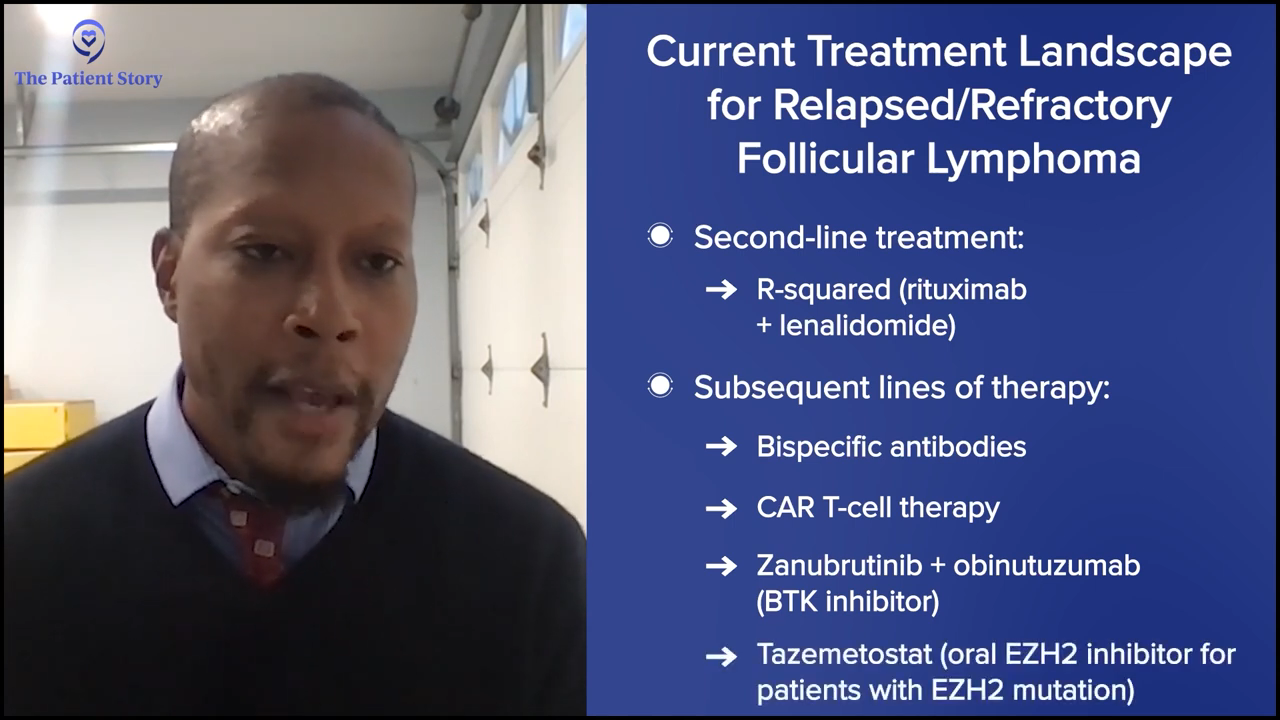

Stephanie: That’s incredible. Dr. Steinberg, we were talking about how at Westchester, bispecifics were available before CAR T-cell therapy was. Can you share a little bit about how you have that conversation with relapsed/refractory DLBCL patients on what treatment options you think are best for them and what goes into that consideration?

Dr. Steinberg: Before we had CAR T-cell therapy, if you relapsed in your first year, I would have to refer you out. The data showed that compared to transplant, within your first year of relapse or primary refractory disease, CAR T-cell therapy had a better outcome. I had to refer patients out, but I would work with the academic center that I was referring to in terms of providing salvage chemotherapy or some kind of chemotherapy to keep the lymphoma under control until the whole process of CAR T-cell therapy could be arranged.

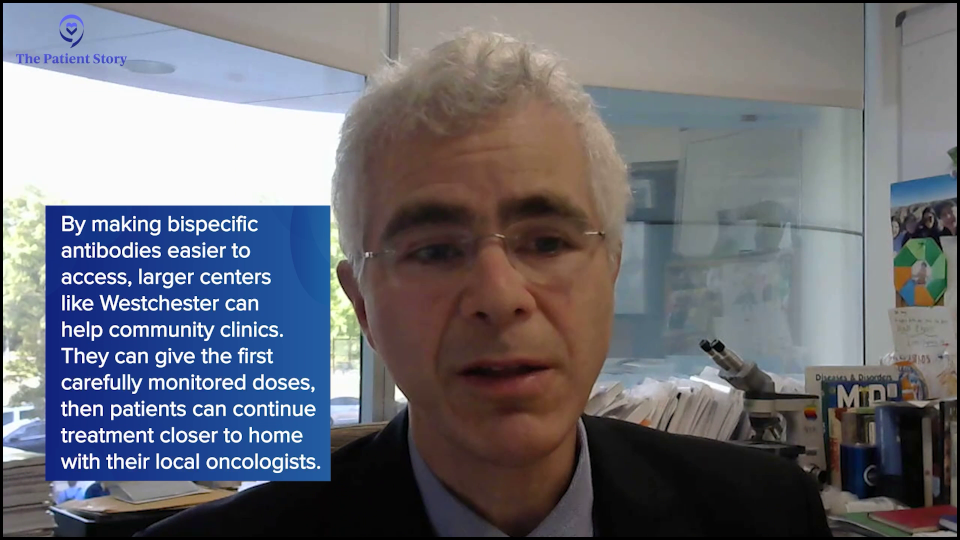

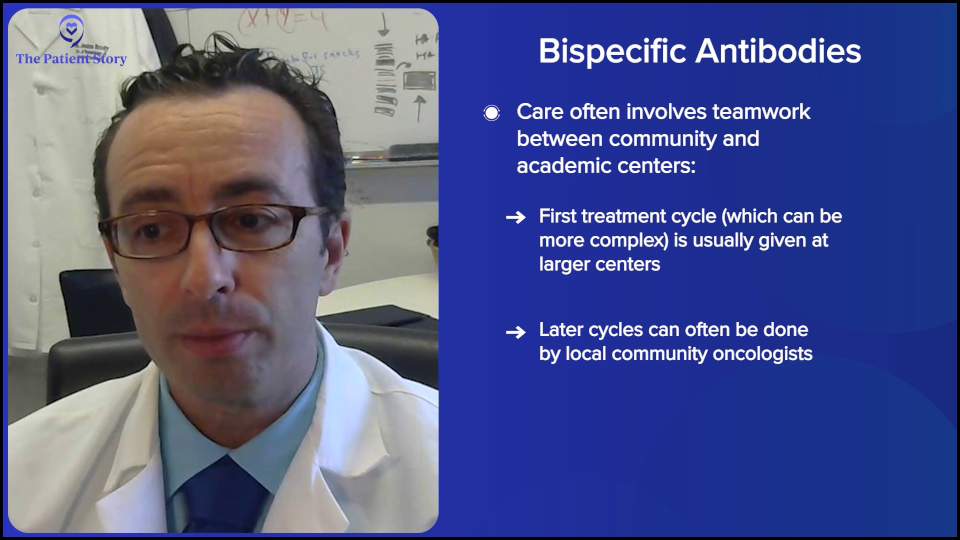

Now with bispecifics, with all these other therapies out there, we’re helping the community centers ourselves. For example, the community center may want CAR T-cell therapy or a transplant for their patient. They have access to bispecifics, but they may not be able to give, for example, inpatient chemotherapy. We help them by doing, let’s say, the first dose or two in the hospital. Like a lot of bispecifics, they need to be monitored closely, and then we hand the patient off to the community center and the community oncologist.

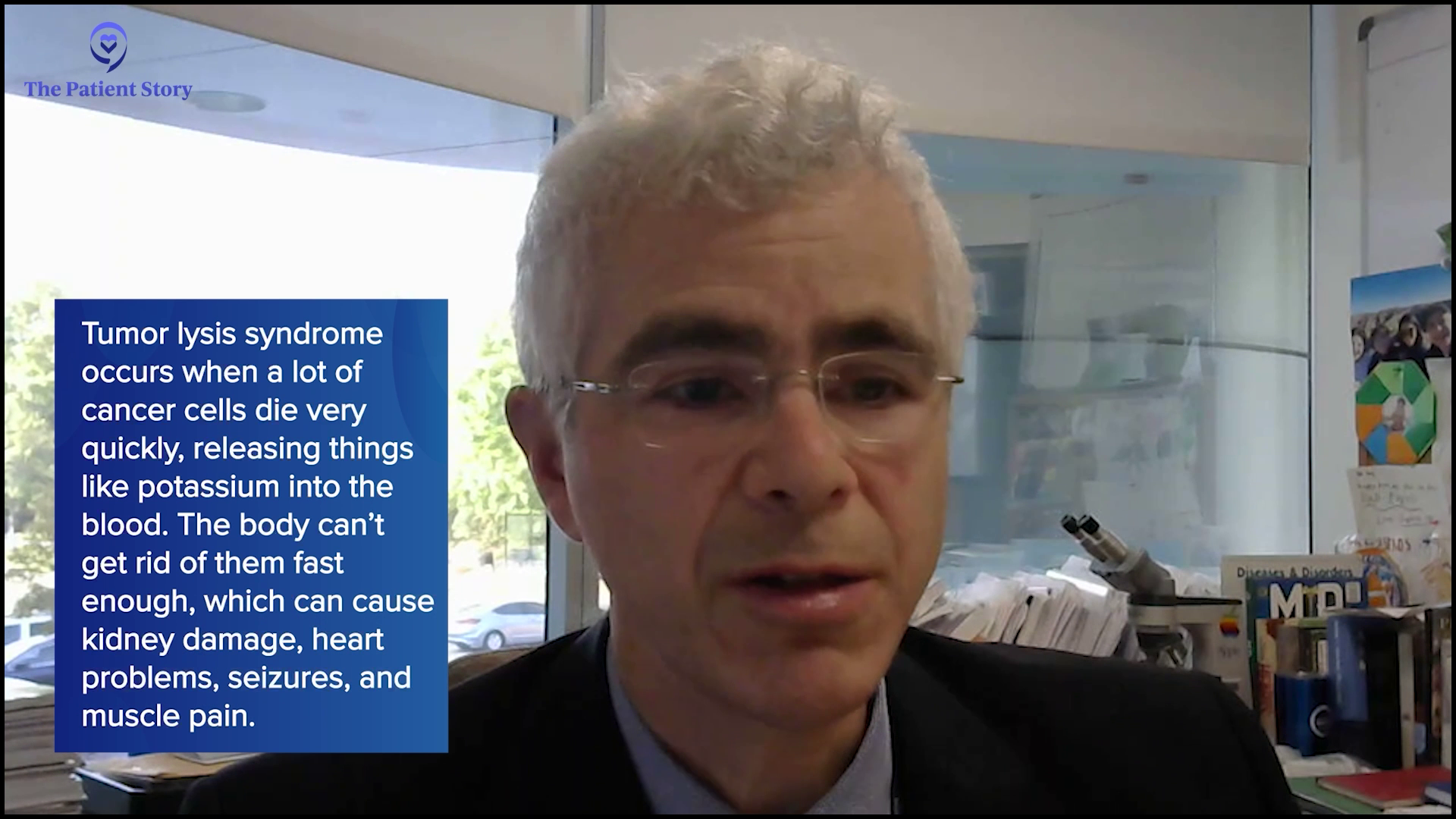

More and more, they’re showing that potentially, some of these patients who are getting bispecifics may not necessarily need to be admitted. It’s a moving target in terms of how that’s evolving. But if you have someone with a lot of disease and you want to monitor them for any kind of tumor lysis, then sometimes inpatient admission to monitor them for that, plus any other side effect,s may be required. There’s a little bit of help out to the community. Also, we sometimes would need help. Now with CAR T-cell therapy here, we don’t refer as much to the centers, unless it’s a special trial, which Dr. Brody and other oncologists and centers may have access to.

Deciding Between CAR T-cell Therapy and Stem Cell Transplant

Stephanie: Can we zoom out a little bit? A lot of people have heard, of course, about CAR T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies. Dr. Steinberg, I know that you had your first patient in 2023. Can you describe that process now that it’s available at Westchester? How many patients are typically undergoing CAR T-cell therapy versus a transplant, and why do you make that decision? What is it about the patient that you go either direction?

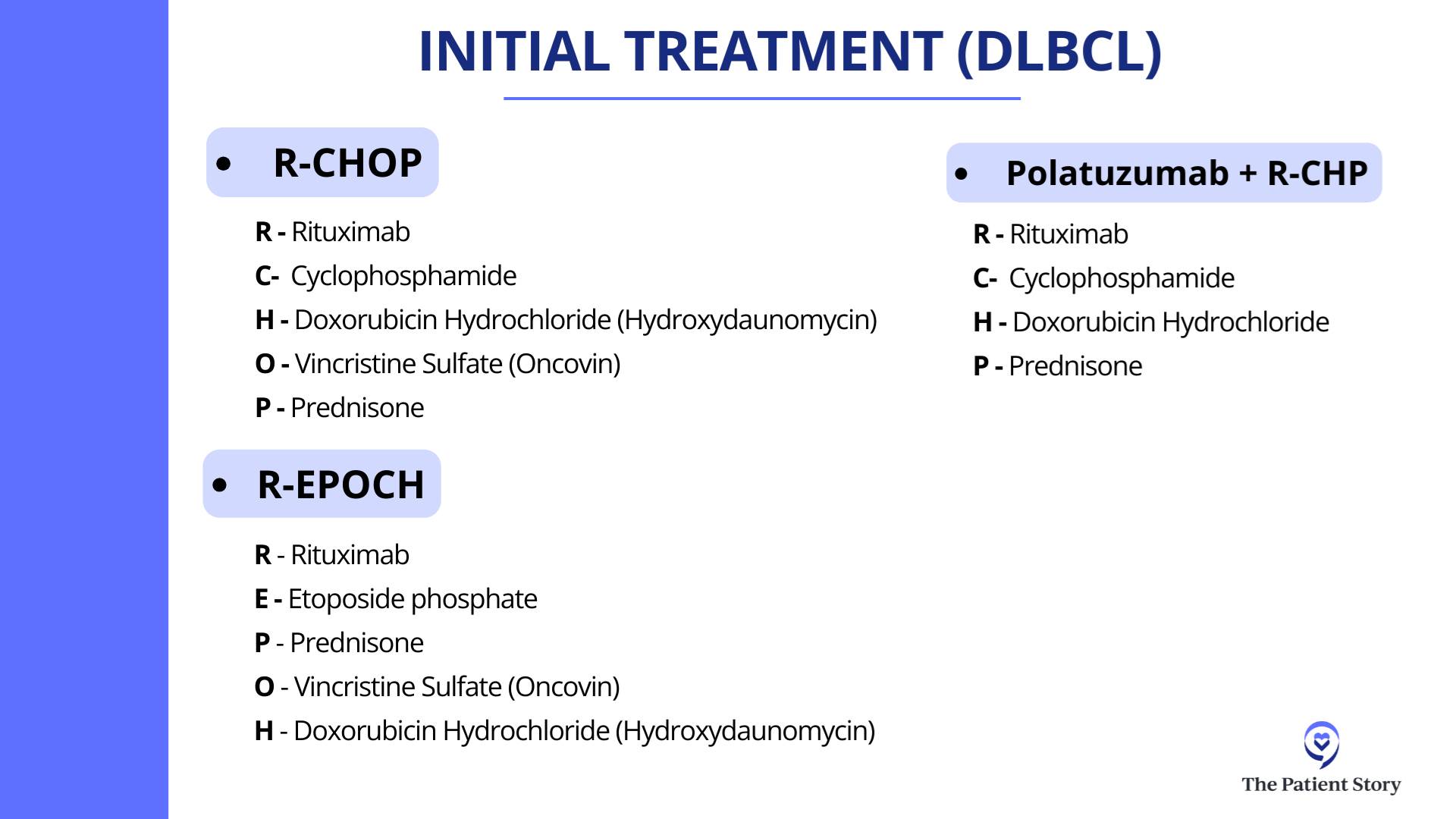

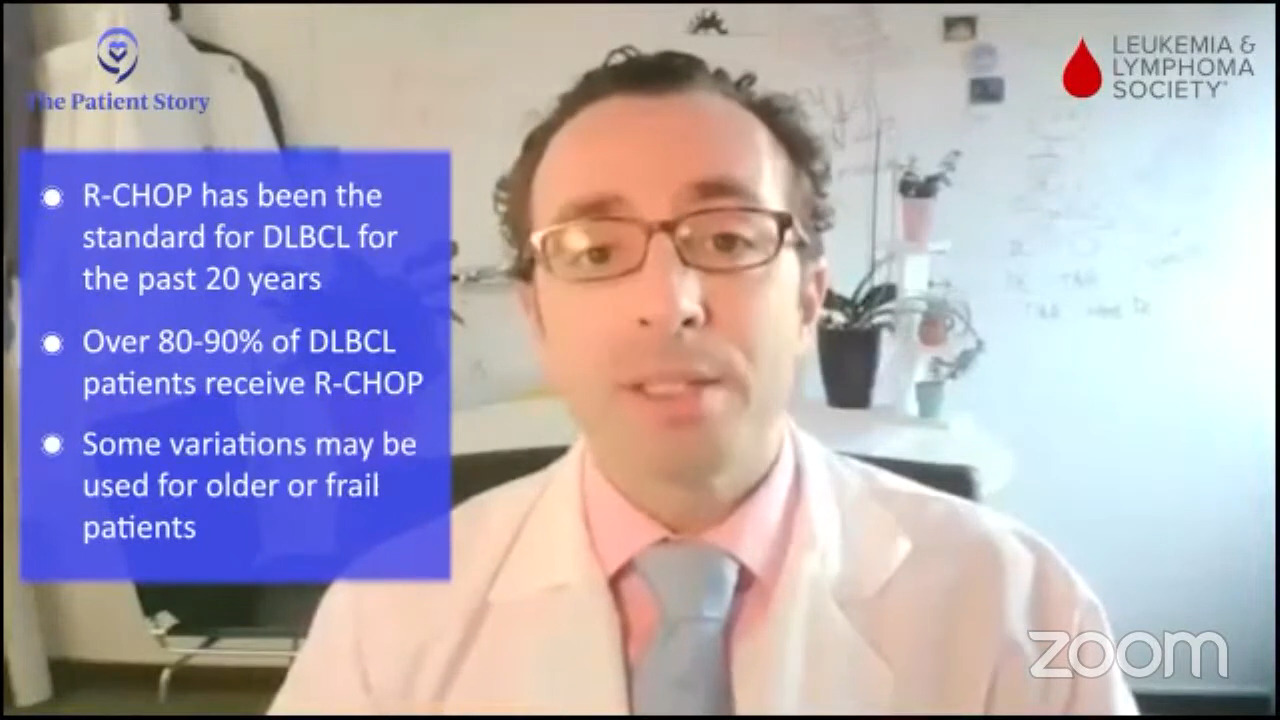

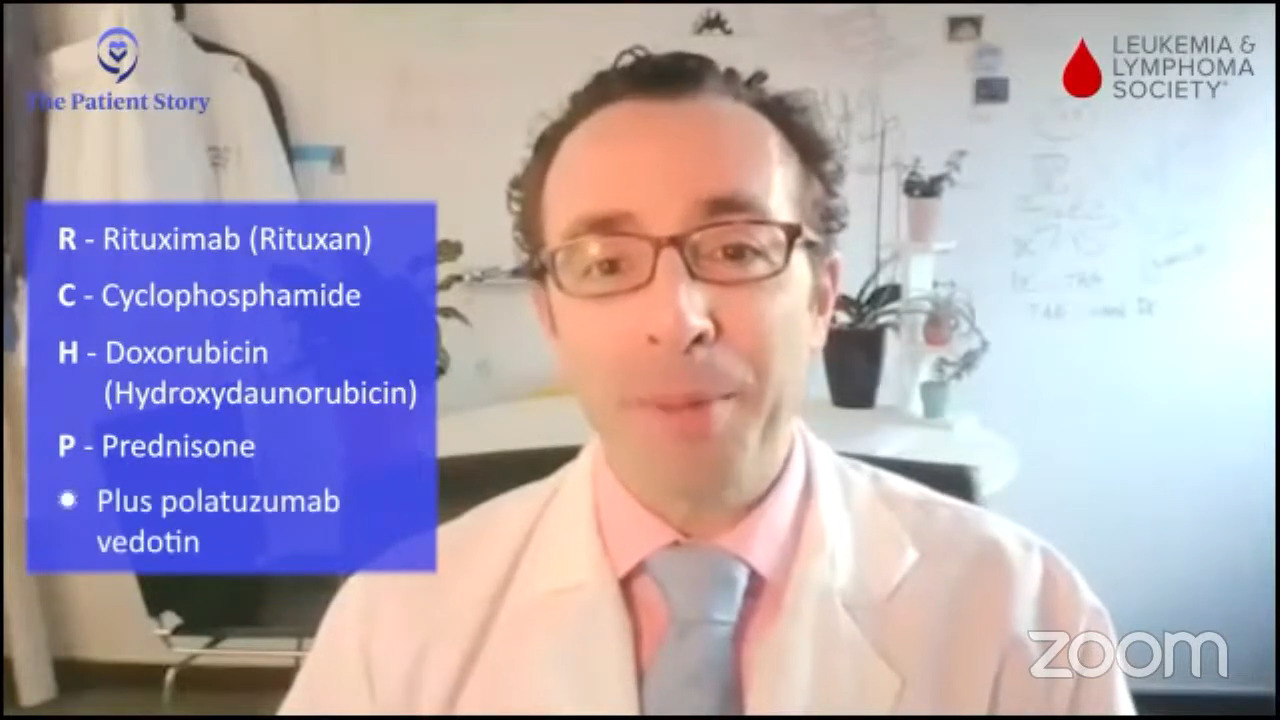

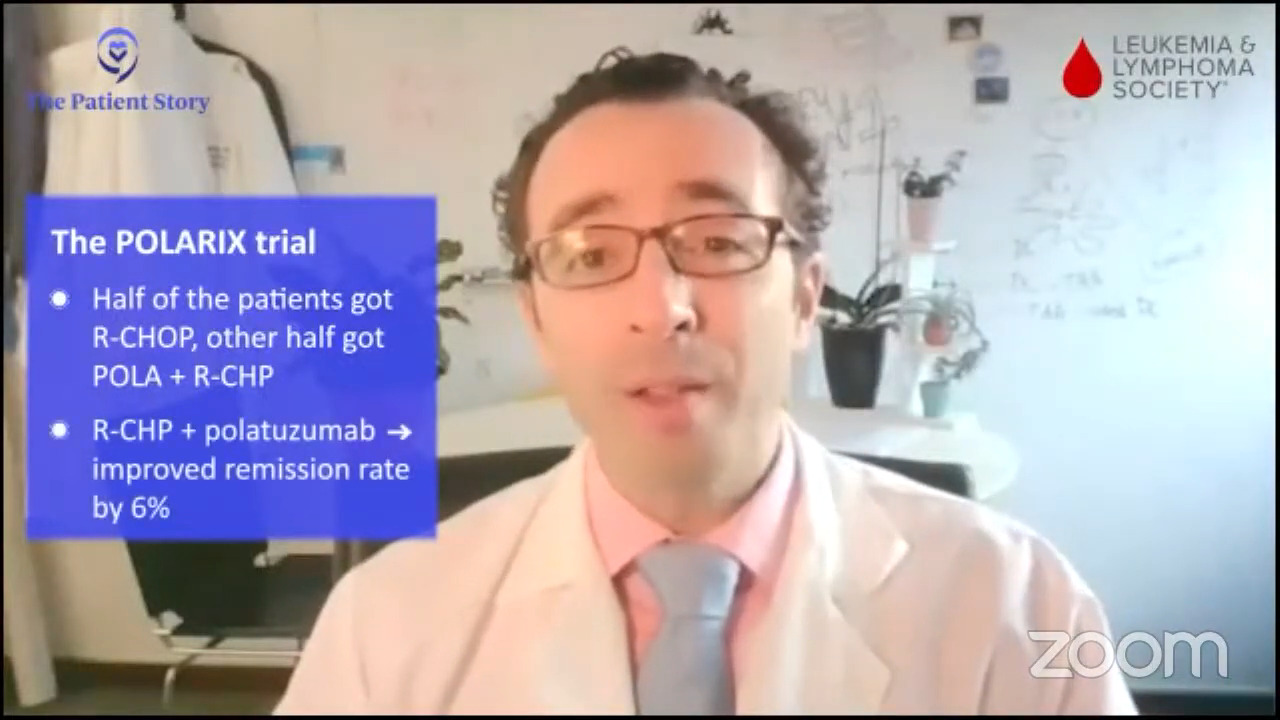

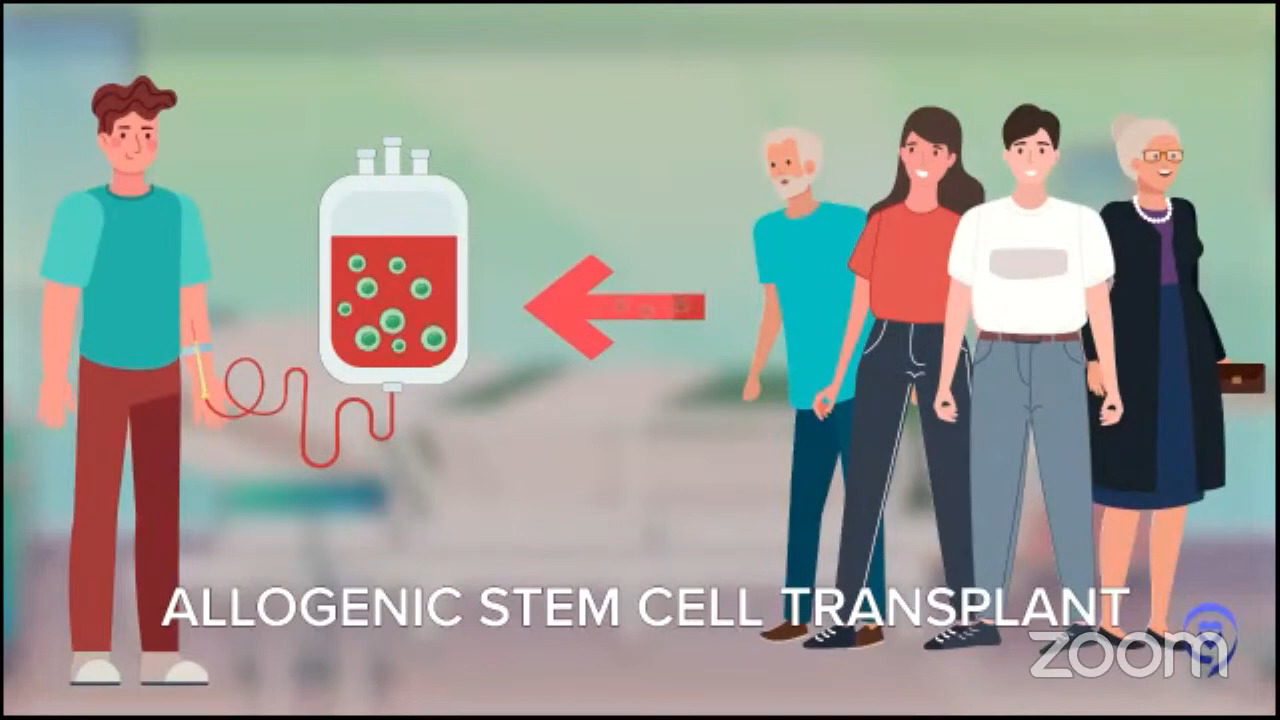

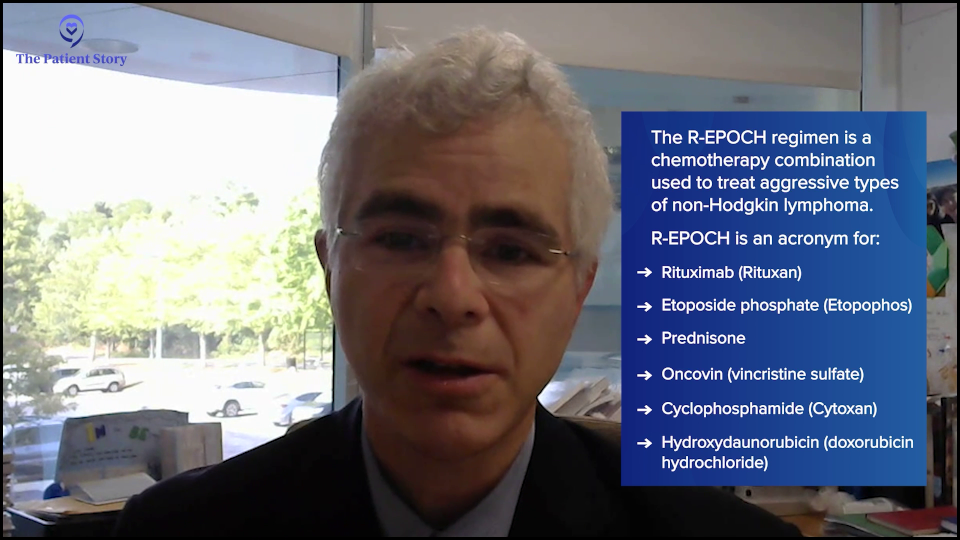

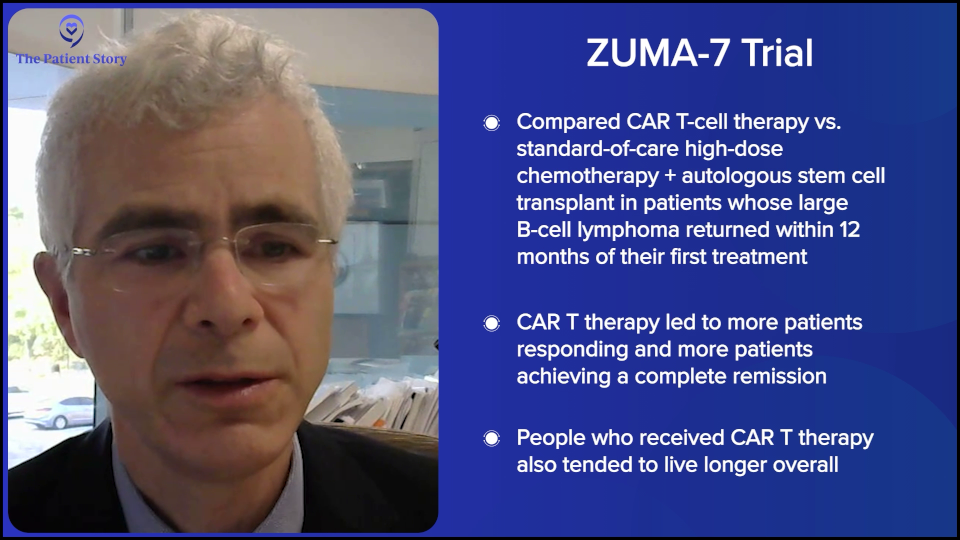

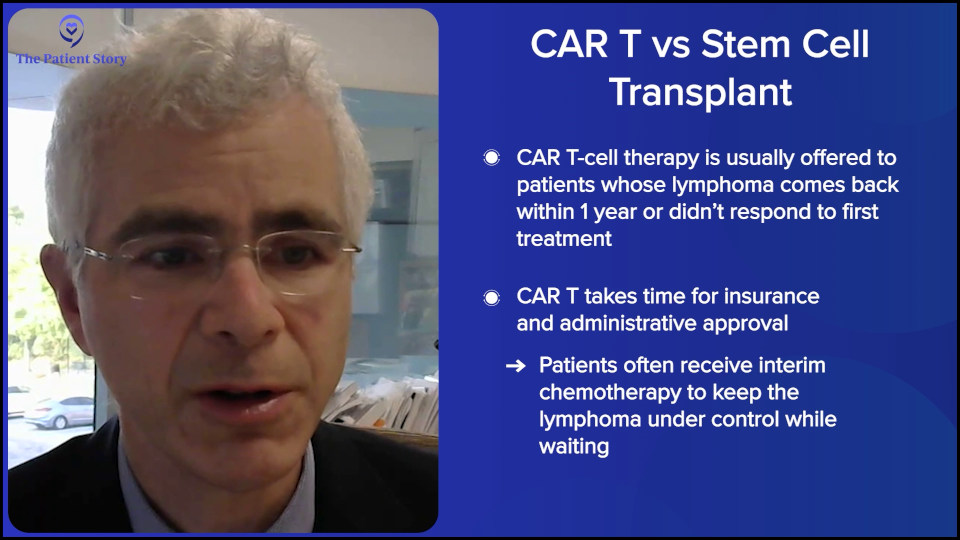

Dr. Steinberg: I believe it was the ZUMA-7 study that compared patients who had a recurrence of their lymphoma. They were randomized to either an autologous stem cell transplant, which is high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue, or to CAR T-cell therapy. The first patients who had a recurrence within the first year of their initial treatment for the lymphoma did better if they went to CAR T-cell therapy. Whenever I have a patient who relapses within the first year of treatment, say R-CHOP or a similar regimen, or they had a primary refractory disease, meaning they did not respond well to R-CHOP, R-EPOCH, or pola-R-CHP, that’s when we think about CAR T-cell therapy.

There’s a lot of time and effort involved with talking to the insurance company and getting the CAR T-cell therapy approved, getting our administration to approve it, and going through all these hoops. In the meantime, while we’re doing all that, the patient would get a regimen to keep the lymphoma under control until all the ducks are in a row and everything’s approved for them to get the CAR T-cell therapy.

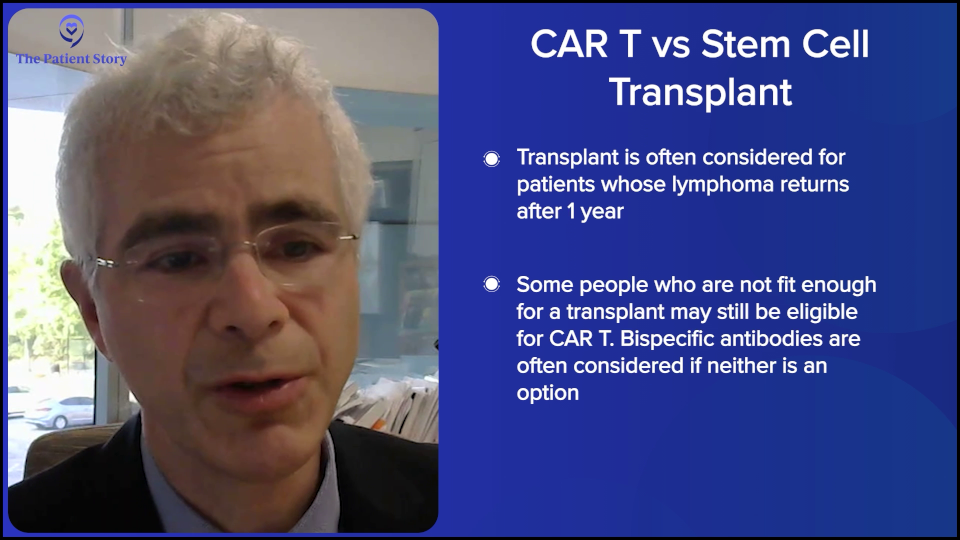

If they relapse after the one-year mark, as you know, CAR T-cell therapy is not approved for patients who relapse beyond the one-year mark, and the insurance companies are pretty strict about that. Could you get around it? I don’t know. You can do appeals with the insurance reviewer to see if you could get it if it progressed beyond a year, but typically, it’s difficult to get approval, so we usually try to head down the transplant road.

However, some patients are not fit enough to get a transplant. They may be fit enough to get CAR T-cell therapy, but not a transplant, so you may then head down the road of doing bispecifics, which have shown tremendously good results. Sometimes you could even use that as a basis. You could argue that they may not be fit enough for an autologous transplant as an argument for why they should get CAR T-cell therapy. With a transplant, you have to be stronger, fitter, and have fewer comorbidities.

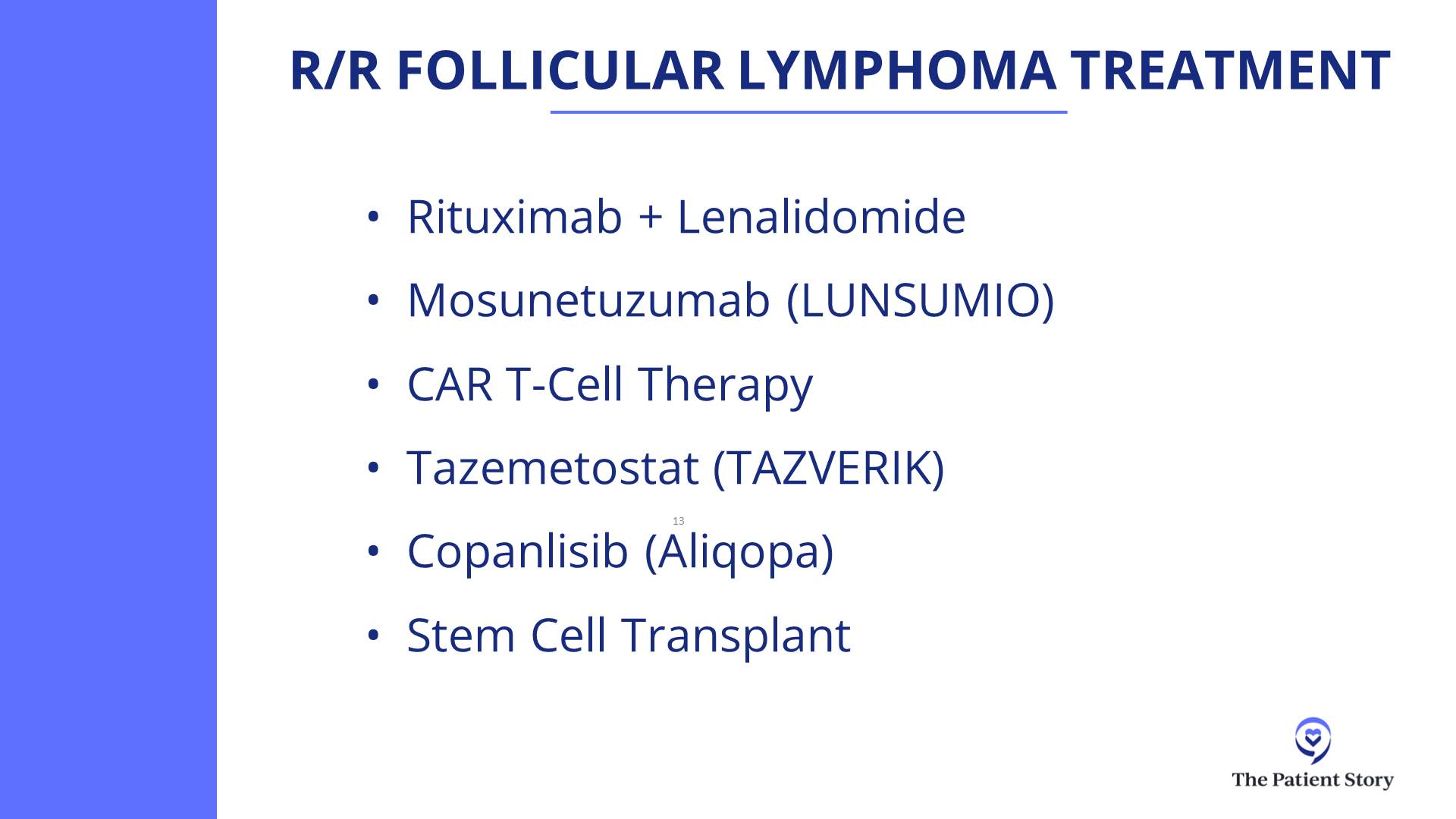

That’s how we make decisions when we see a relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patient. We can get into follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone, and all the indications for them in terms of CAR T-cell therapy and transplant.

Stephanie: Well, you just volunteered yourself for four different programs in the future. [Laughs] No, I appreciate that. This discussion is focused on DLBCL. There is so much to get into, but I know in so many other spaces, there’s a lot to talk about as well.

Using Treatments Earlier in Care

Stephanie: Dr. Brody, let’s zoom out even further on bispecifics. You talked about one of the clinical trials, STARGLO. If you were to lay out in simple language, which I know you’re really good at, for patients who are dealing with relapsed/refractory disease… There are different lines of treatment, obviously. You’re getting your second or third line. What is the matrix right now? There are different considerations based on a patient’s profile, but what are the general options for second-line and third-line treatment? This will help us set up to talk about other clinical trials because we know that when something is approved and doing well, there’s a tendency to try and get them to earlier lines, right?

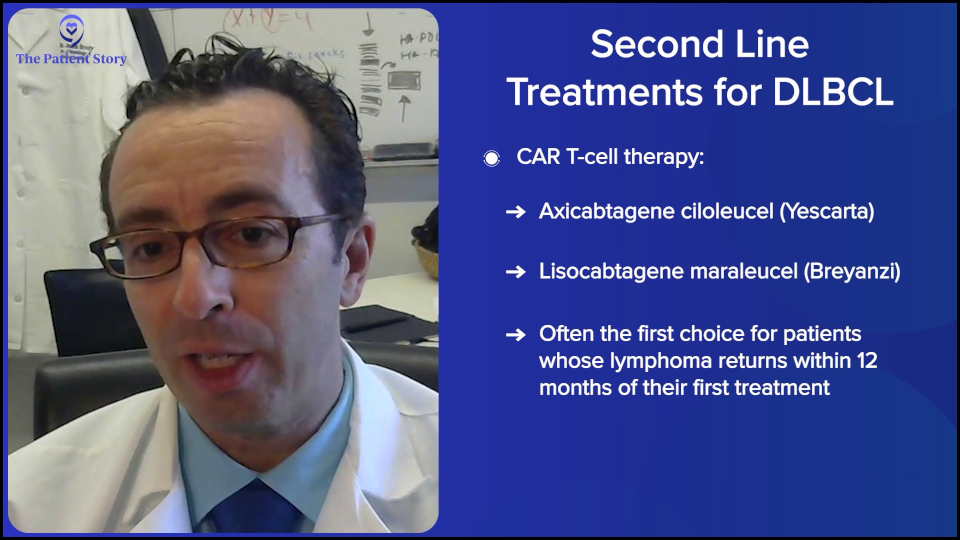

Dr. Brody: For the second line, one of the favored options is autologous CAR T-cell therapy. Axi-cel (Yescarta) and liso-cel (Breyanzi) are certainly a high priority for the folks who relapse after their first-line chemotherapy within 12 months, so it’s very high on the list.

Then again, the nuance is that some patients may not be great candidates because CAR T-cell therapy has some significant adverse events associated with it. We won’t get into the specifics. For some folks who are 85 years old and not running marathons recently, they may not be great CAR T-cell therapy candidates. There’s a spectrum of exactly how great a candidate someone is. There’s no absolute age cutoff and no number of miles you need to be able to run.

There’s a little bit of nuance there because, as Amir was saying, this is not just what we think is best, but what’s been proven and accepted by the FDA. Then there’s another overlap of what insurance payers are agreeing and willing to pay for. There are a lot of layers to that.

In 2025, the FDA has been extremely interesting. We’re just going to leave that as a blanket statement and say that we, Amir and I, go by what has been proven to be the best for patients, and our beliefs about that are based on very strong data. Bispecifics plus chemotherapy should be an option for second-line DLBCL patients, especially for those who aren’t eligible for CAR T-cell therapy. But I don’t want to put it as a blanket statement that that’s what everyone should be able to get access to. We have been able, fortunately, to get access to that option.

As Amir was saying, the old standard was platinum-based chemotherapy — and there are a few versions of that — followed by autologous stem cell transplant. But I’ll say that the third option I mentioned has been diminishing over the past few years for us, while those other two have been increasing.

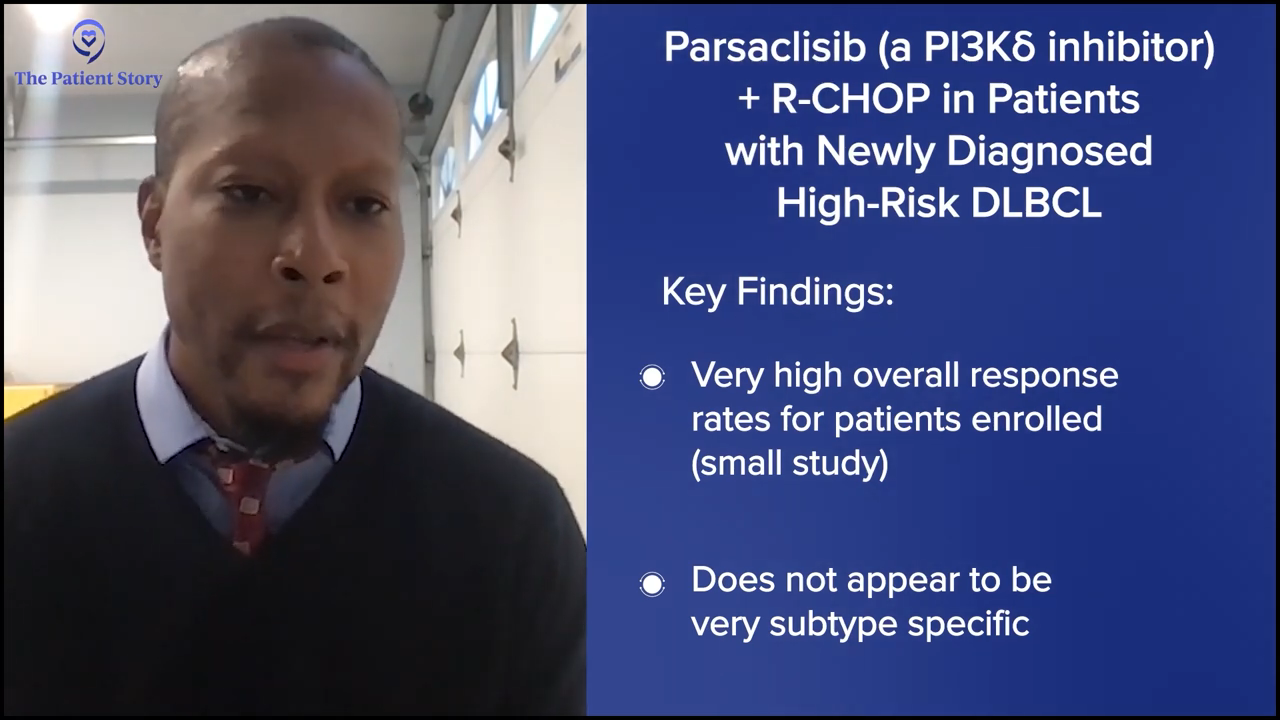

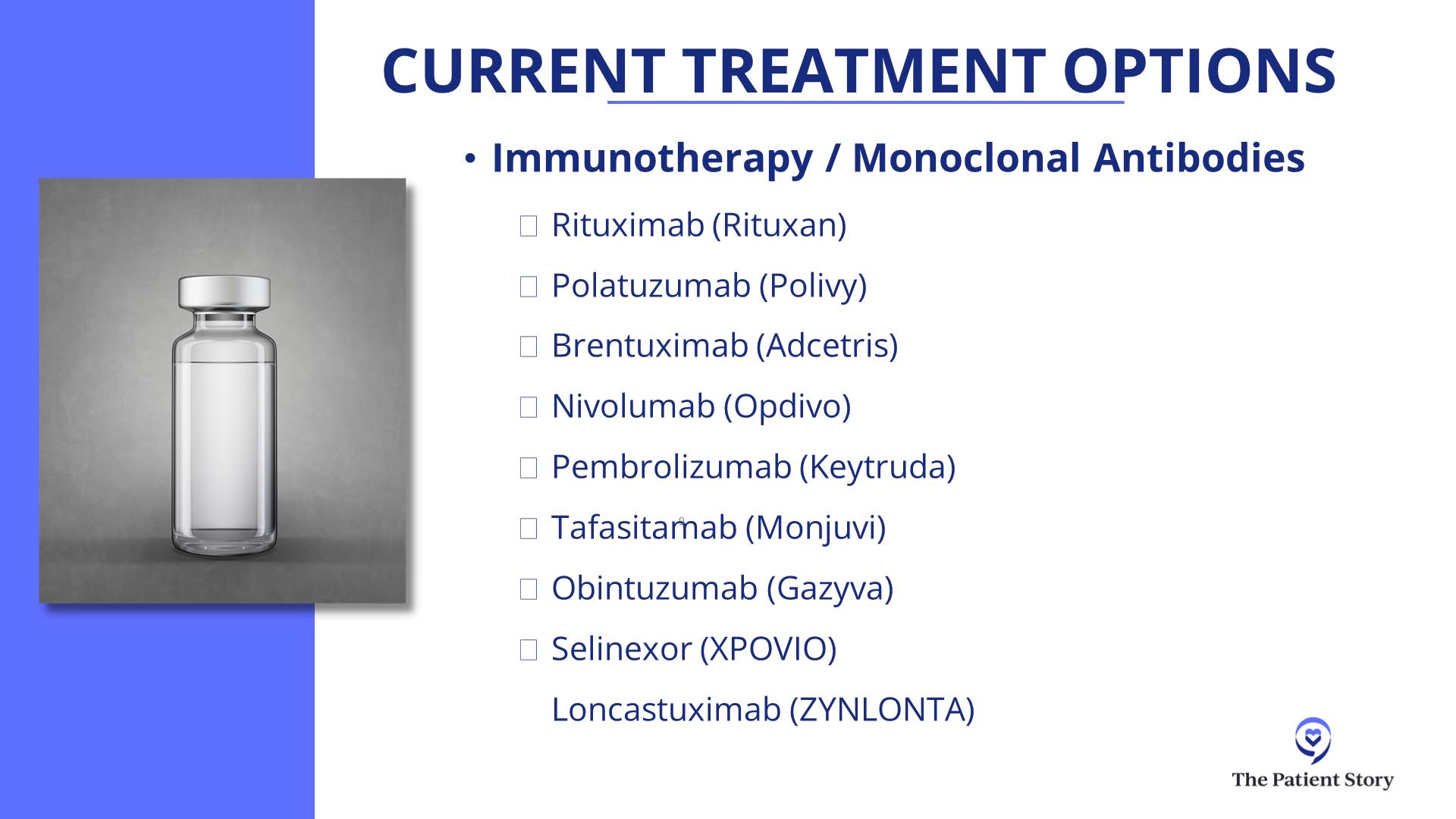

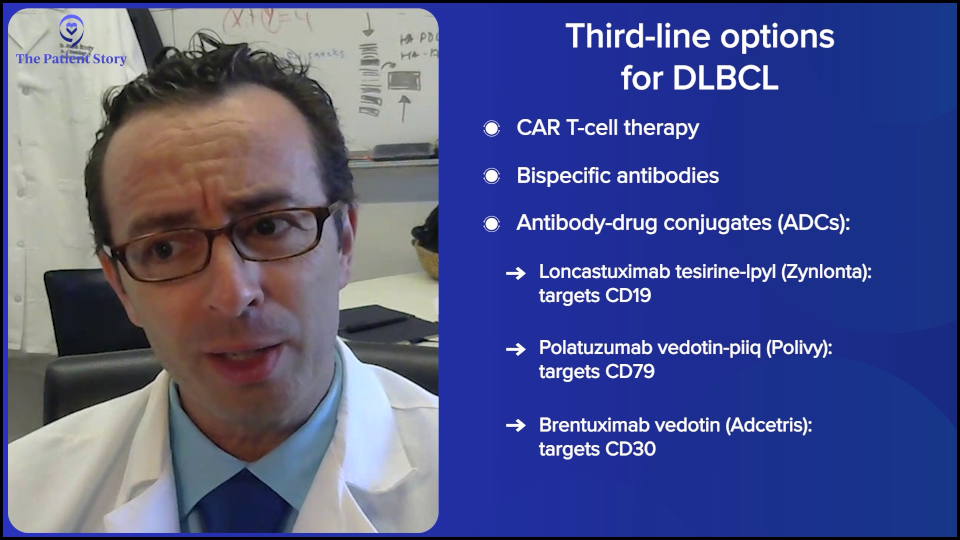

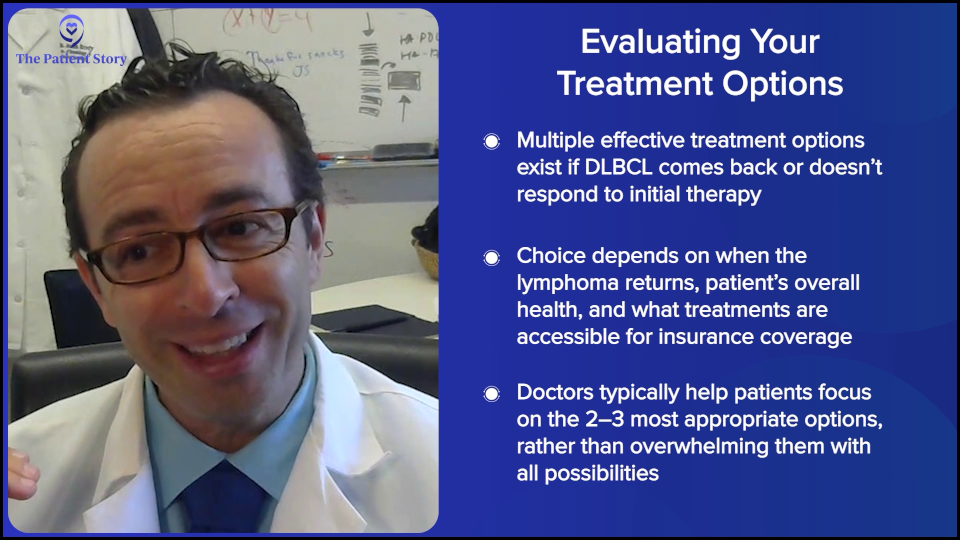

In the third line, we have a lot of options. We’re very lucky because, even though lymphoma is technically the fifth most common cancer in America, we have more FDA-approved medicines for lymphoma than for any other cancer, even more than for breast cancer, which is so incredibly common. It’s awesome because it means we have more options for patients, but it also makes things a bit more complicated because we don’t always have the right and wrong answers. We have, “Here’s a bunch of options. They haven’t all been compared to each other.”

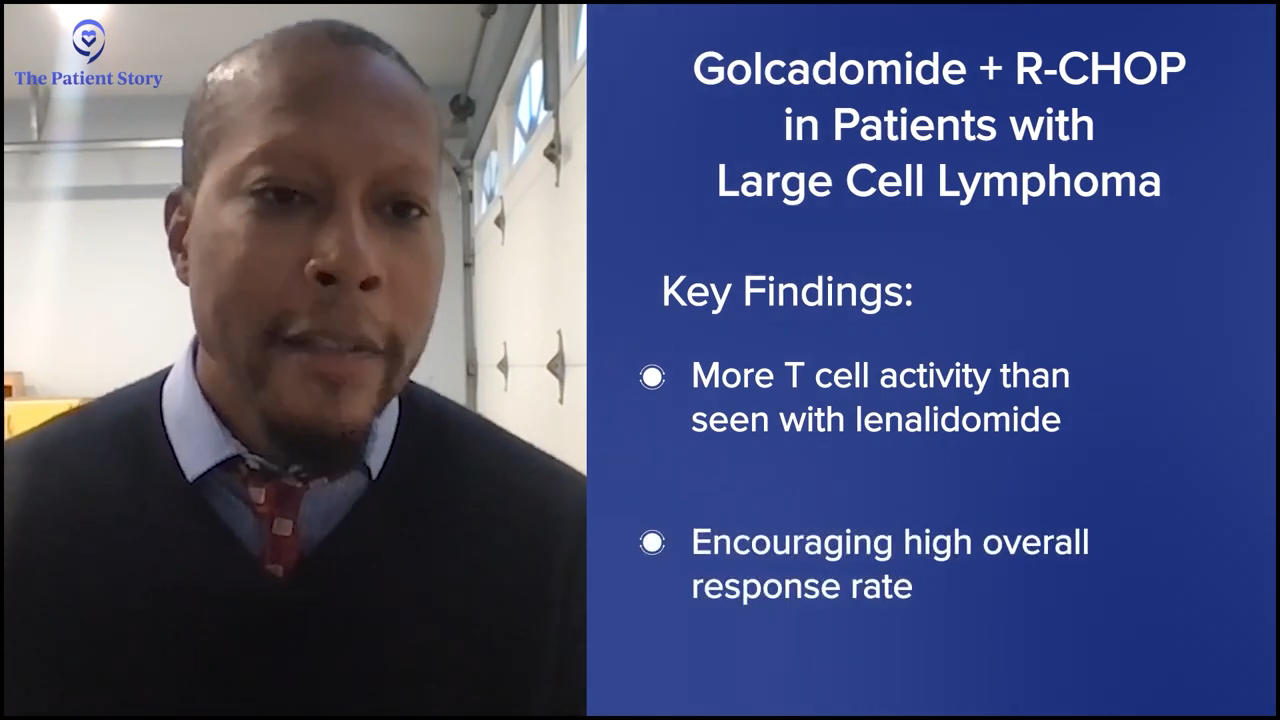

In third-line treatment for DLBCL, it’s like that. We have CAR T-cell therapy approved. We have bispecific antibodies approved, either by themselves or combined with other agents. We have antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs). It’s an antibody with a little bit of chemotherapy on the tail end. We technically have about three of those approved now — loncastuximab tesirine (Zynlonta) targeting CD19, polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy) targeting CD79, and brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) targeting CD30.

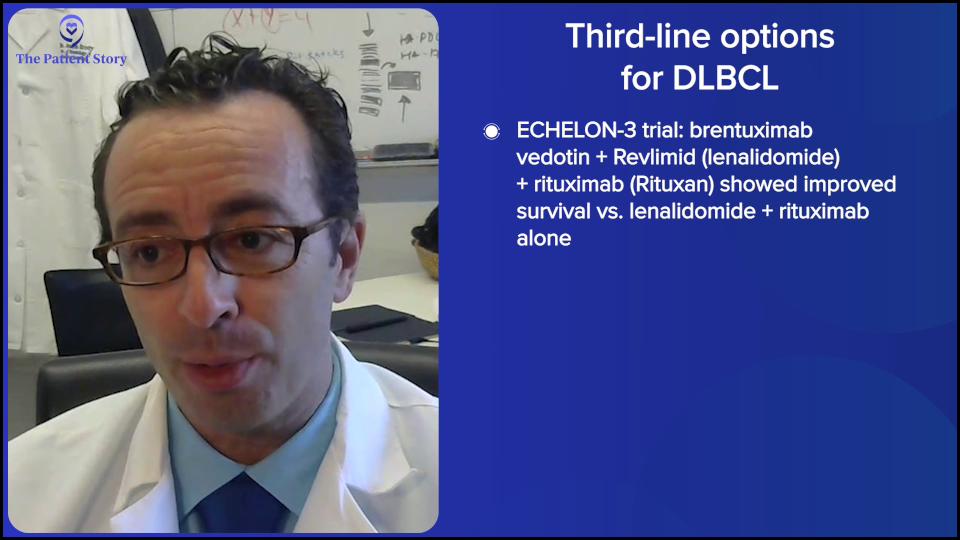

I want to give a special shout-out to brentuximab because it had fantastic results in a randomized phase 3 trial called ECHELON-3, proving that with brentuximab combined with lenalidomide (Revlimid) and rituximab, compared to other standard therapies, those patients live longer than patients who got lenalidomide (Revlimid) and rituximab by itself. The reason that’s pretty exciting is that brentuximab was not thought about very much for DLBCL, even just a couple of years ago. This randomized trial showing that patients lived longer — with some of them having some pretty durable remissions — is a huge advance that I would not even have predicted two years ago.

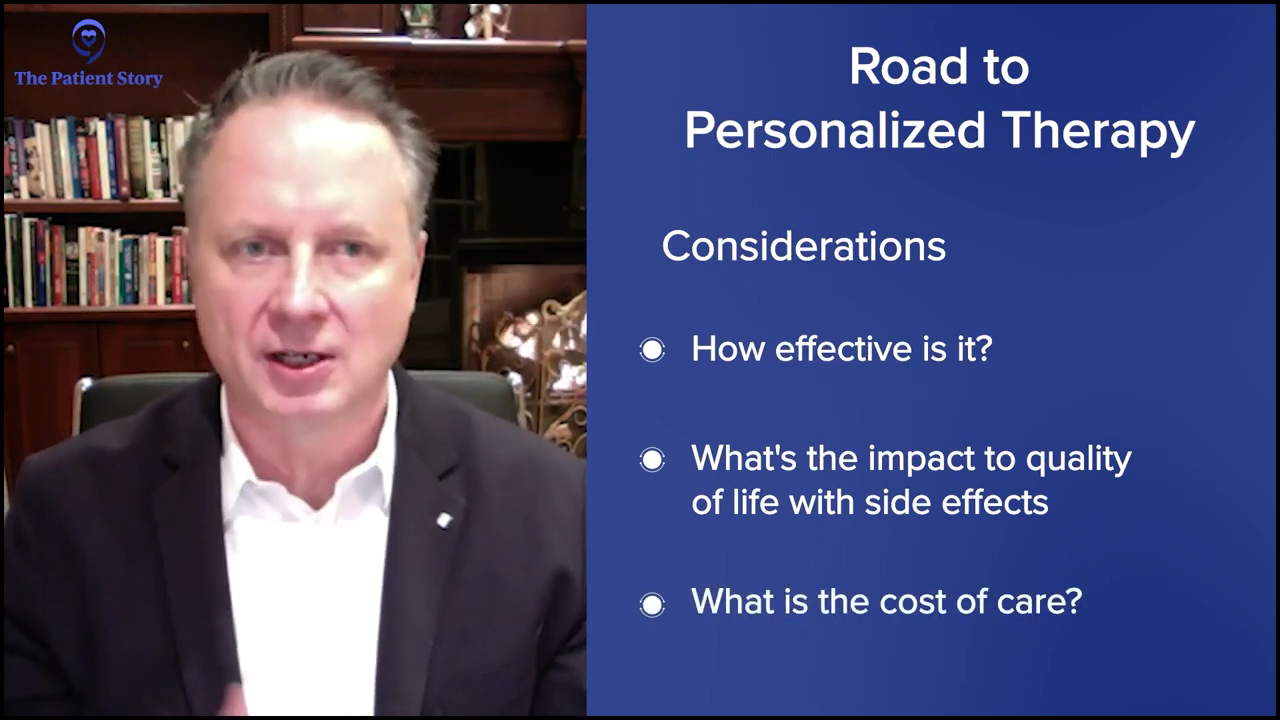

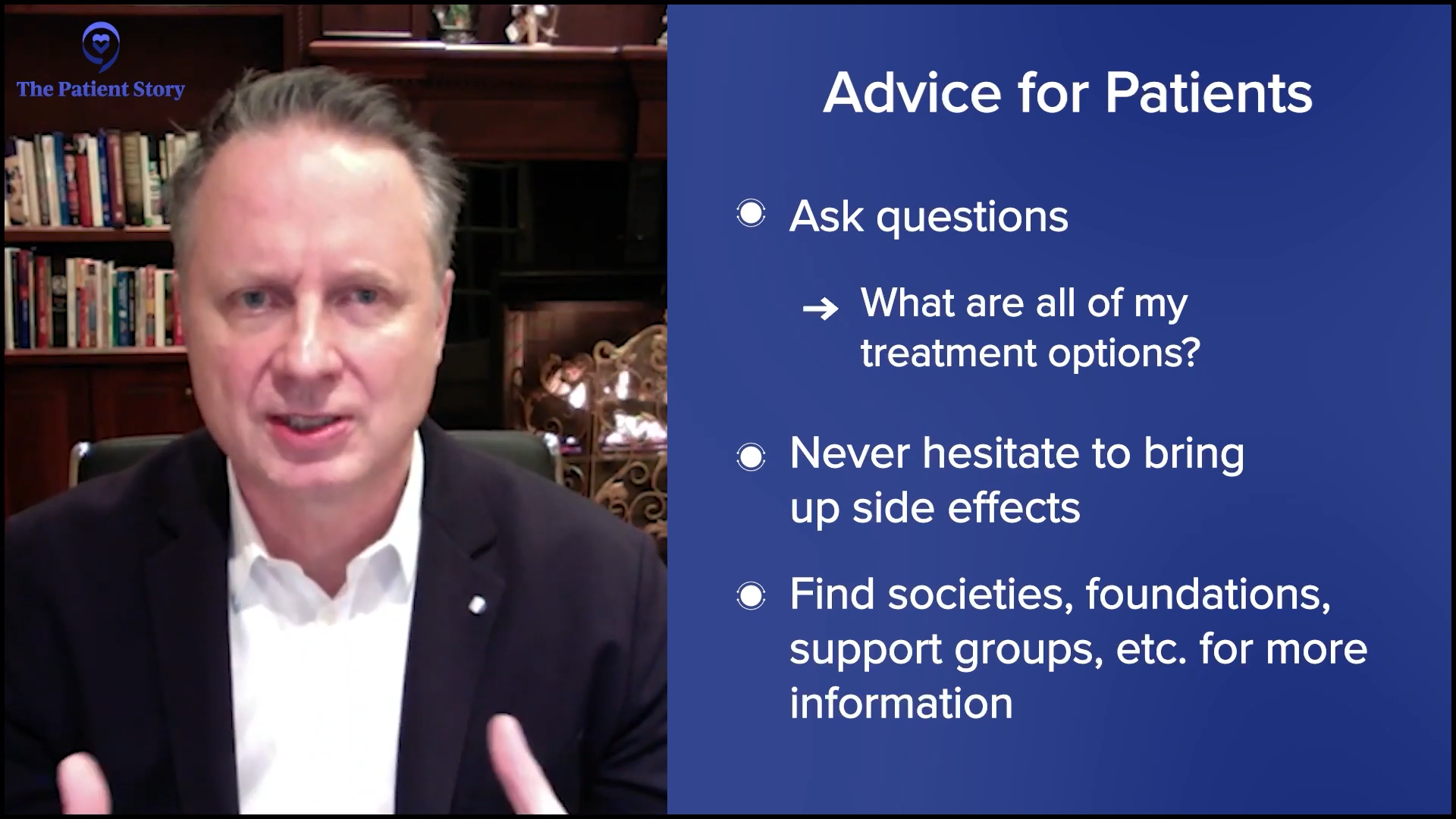

I’ve hit most of the big categories of therapies for the second and third line. It’s a long discussion with your doctor, as you can imagine, but not impossible. It’s a lot, but happily, as Amir was saying, you don’t have to capture it all. It’s good to record the conversation or have someone with you, keeping track of it all for you, and having questions about all the things that are most promising.

Obviously, patients know the critical question: “Doc, if it were you or your family member, what would you do?” We give straightforward answers for that, so you don’t have to memorize all 20 things. You may want to hear about the two or three that the doctor says would probably be appropriate.

Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Treatment

Stephanie: What questions can patients ask their doctors if they’re not seeing specialists like the two of you? Are there other questions that you might suggest patients to ask to make sure that they’re on the right track and that the right considerations are happening, especially given all the options right now?

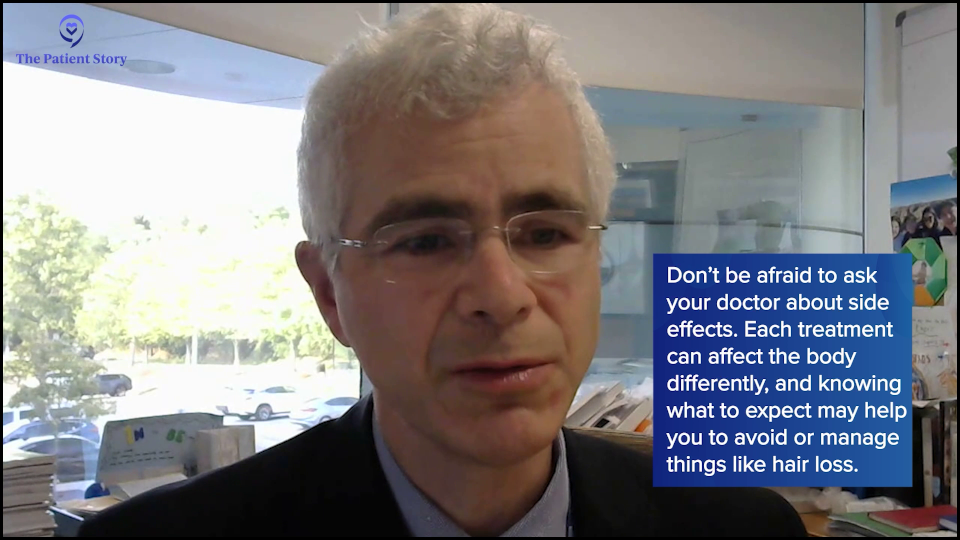

Dr. Steinberg: I can just say that there’s a question that a lot of patients do ask, which is about hair loss. That was a concern I had as a cancer patient. My dad lost his hair and my sister as well, so I know patients sometimes ask that. Unfortunately, sometimes the regimens we give cause hair loss. But one thing that you can point out to patients is that in these later lines of treatment, a lot of these treatments may not necessarily cause hair loss, such as bispecific antibodies and the antibody-drug conjugates that Dr. Brody brought up. They have different side effect profiles.

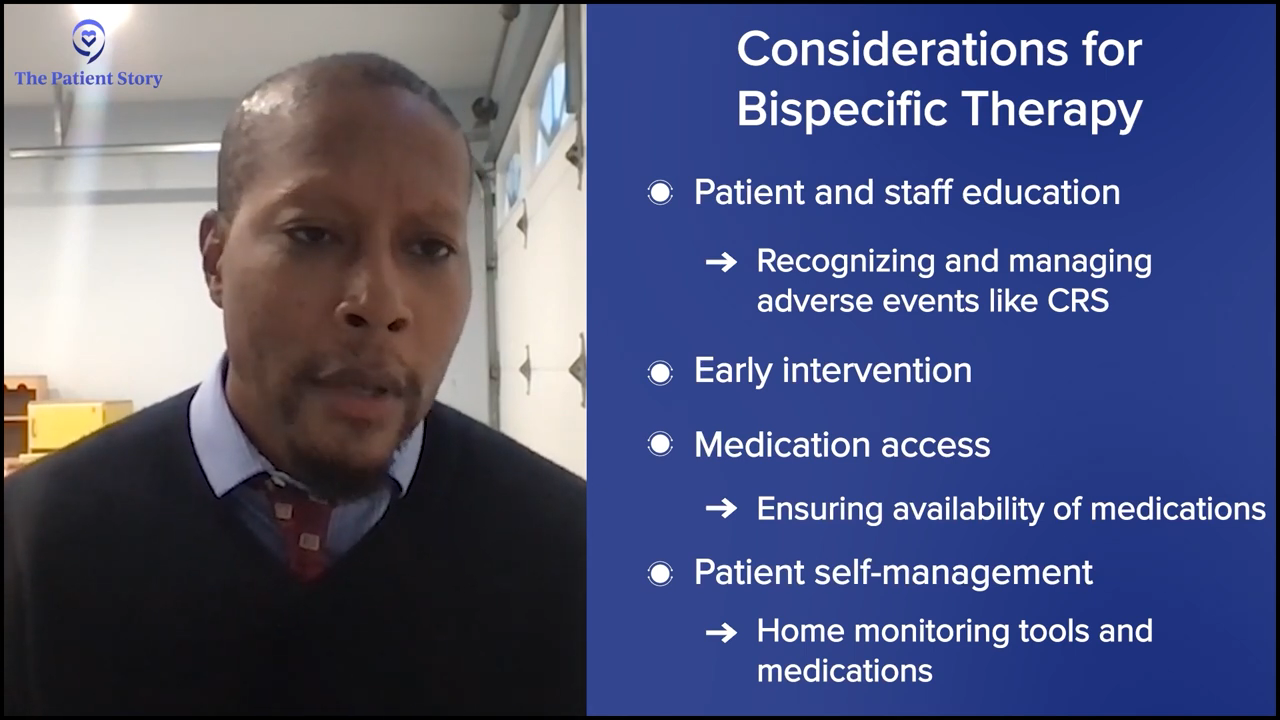

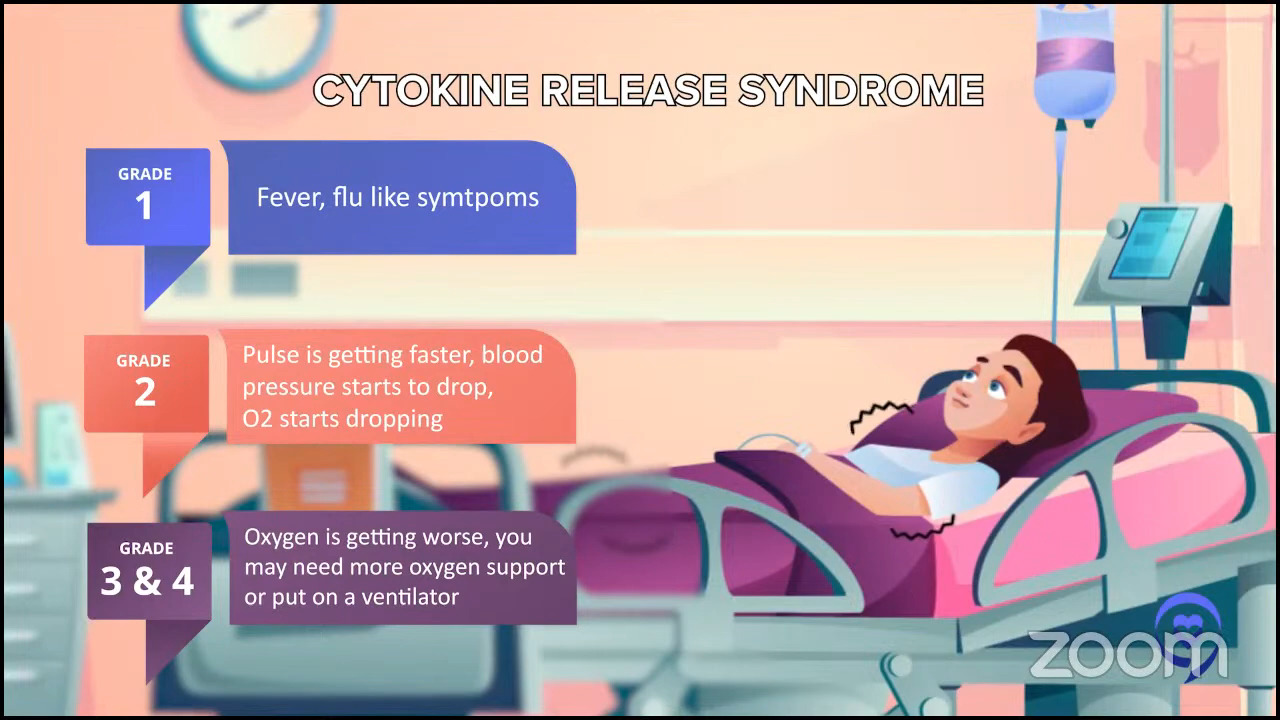

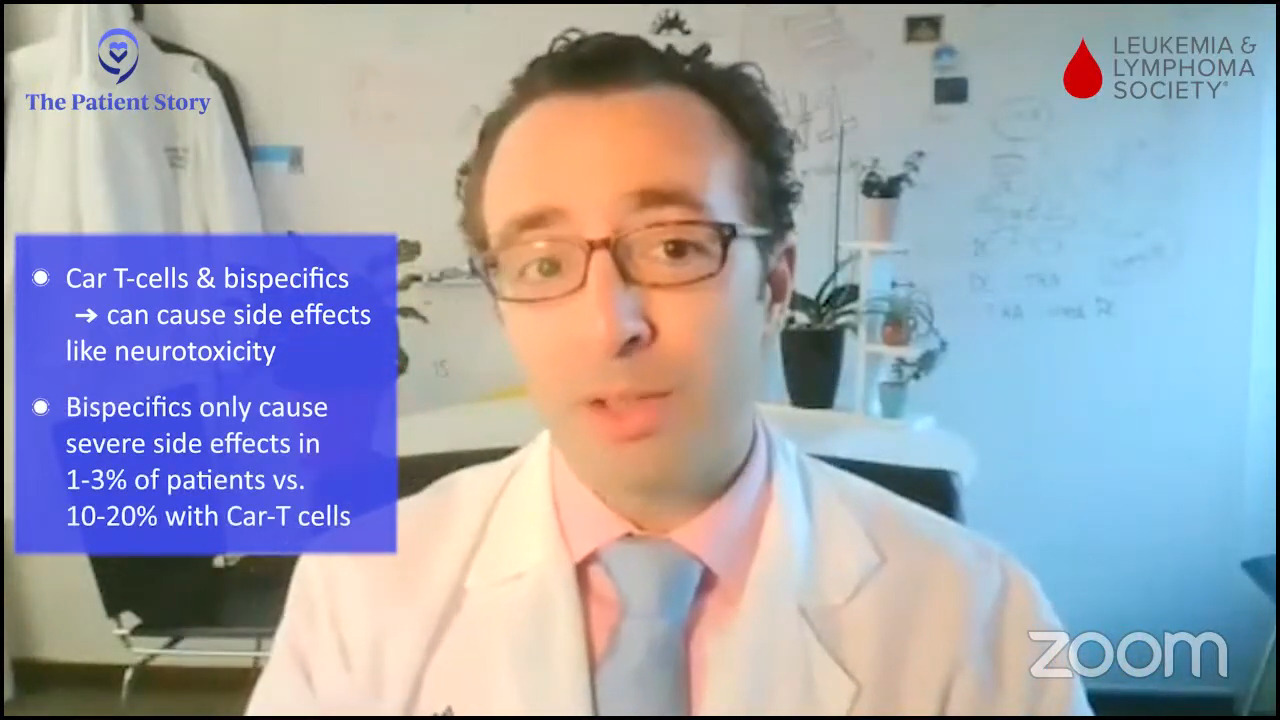

Asking about side effects should be focused on. They’re more focused on allergic reactions. Certainly, you still have to worry about infections, but it’s a different kind of side effect for allergic reactions and no hair loss, not necessarily nausea and vomiting. Sometimes, you have to worry about potentially fevers, but very rarely and that’s why we sometimes have to monitor these patients in the hospital. The bispecific antibodies altered mental status, which they call neurotoxicity. Those are the different side effect profiles for later lines of treatment or these newer agents.

Considerations When Taking a Bispecific Antibody

Stephanie: That’s a great addition to the context. There are a couple of questions about access. We’ve talked about it throughout the conversation. But before, when we started hearing about bispecific antibodies, it was about having more access to something like that in more places versus a CAR T-cell therapy, where — don’t even talk about insurance — logistically getting to a center that offers CAR T-cell therapy is a little harder. There’s a long process to getting certified or making sure you have all the right things to be able to execute CAR T-cell therapy. I would love to understand what that’s looked like for you. It may be a little bit different where you are, Dr. Brody, but Dr. Steinberg, you had bispecifics first. Has that been a big factor in what you suggest to patients?

Dr. Steinberg: I’ve been very impressed with bispecifics. The data speaks for itself, but also my personal experience treating patients with them. Again, the good news is that they’re not stuck in the hospital for weeks on end. You can primarily manage them outpatient and try to get the community oncologists to give those agents so that you can see them less frequently. That’s the big benefit of bispecifics now.

The question is: will the community hospital give the drug? I think they’re willing to give it, especially if it’s an outpatient medication. We’re there to help them start the medication if they need any inpatient monitoring. But once they get the show on the road, once the patient starts the drug, most community oncologists will probably be able to give these medications in the outpatient setting.

Stephanie: Awesome. Dr. Brody, anything to add there? I know you offer all of the above at a big center like Mount Sinai.

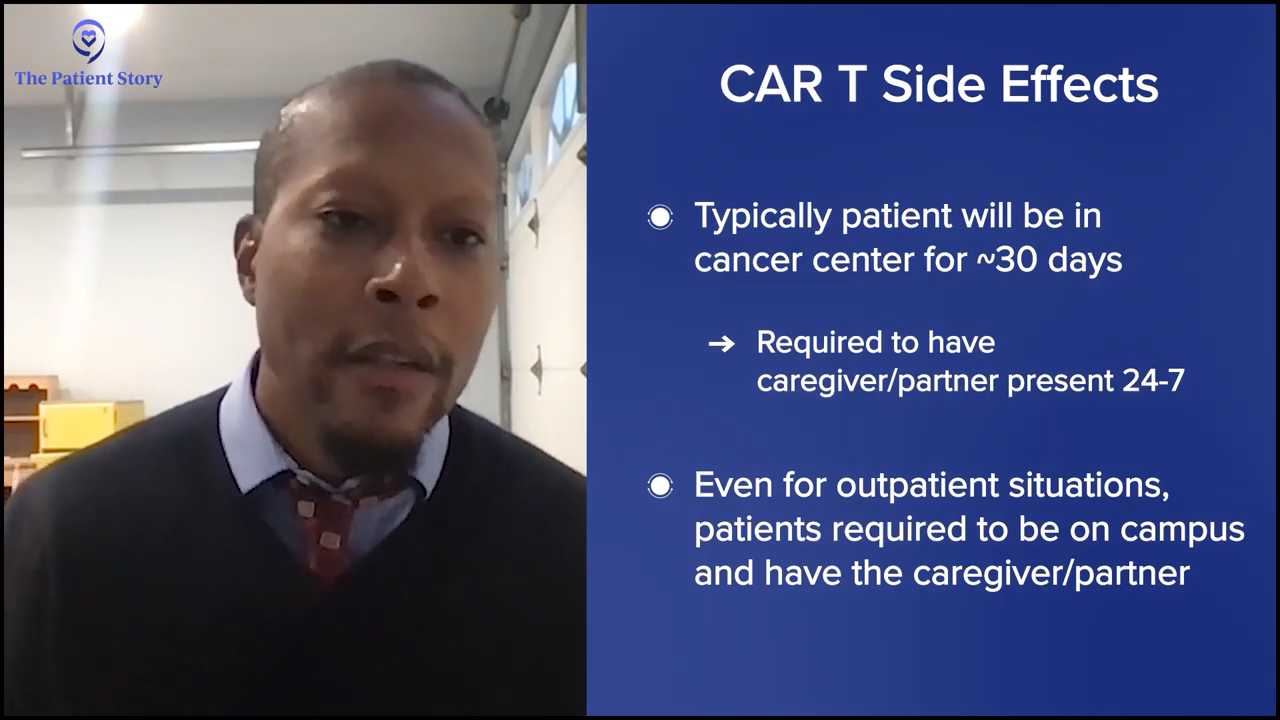

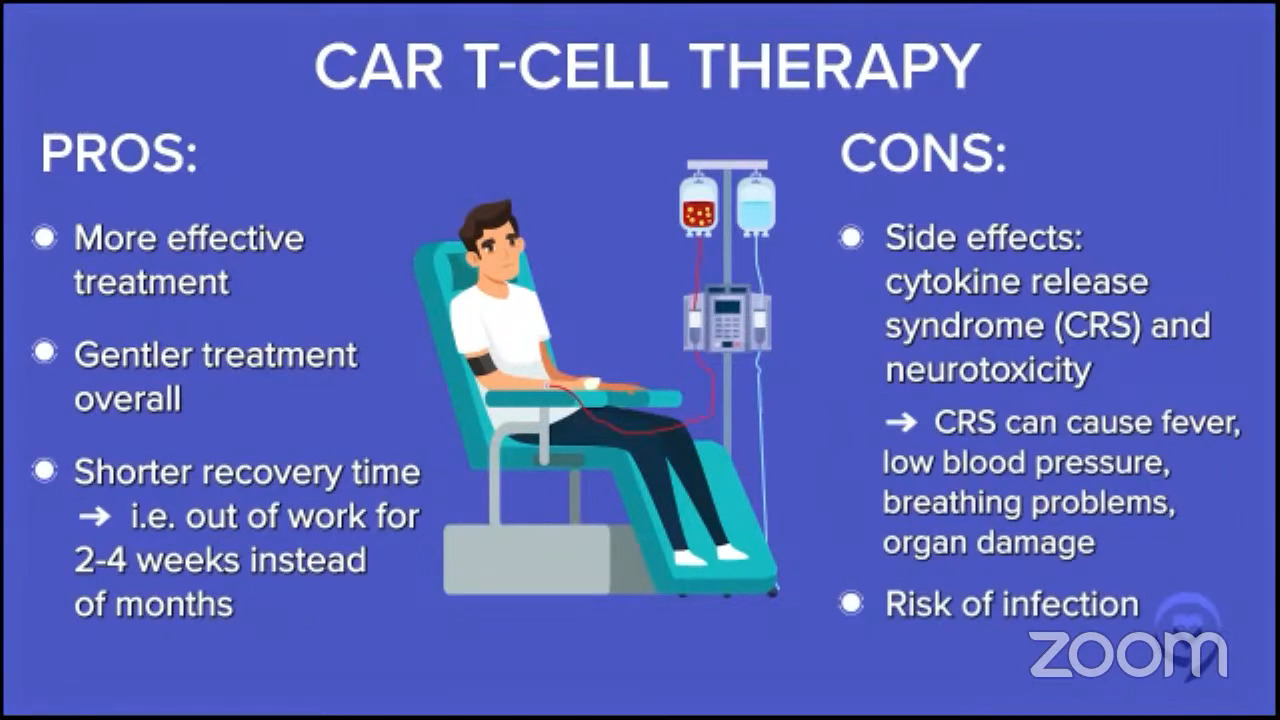

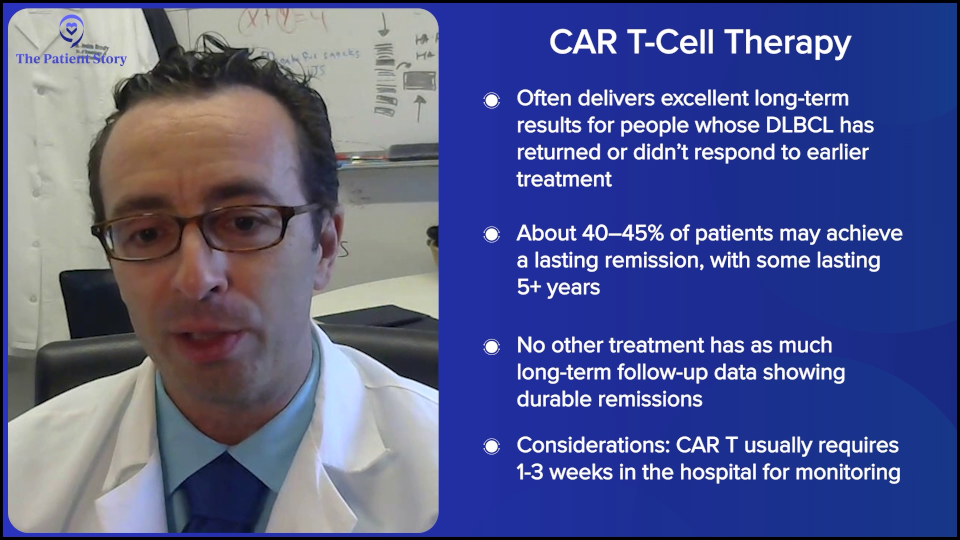

Dr. Brody: We shouldn’t totally shake a stick at CAR T-cell therapy because in this setting, they not only have great results, but also the best kind of precedent of how long we’ve seen these patients for. We have relapsed/refractory DLBCL patients who we used to think that if they weren’t transplanted, it was an incurable disease. Here we see CAR T-cell patients five years later and beyond, staying in remission. We must be curing 40 to 45% of them; we don’t know the exact number, so that’s awesome. No therapy has that much long-term follow-up to prove that patients are being cured.

At the same time, we have all these metrics, like survival, cure rates, and all that, but patients have their own metrics in their lives. I was talking about CAR T-cell therapy with a patient and they said, “You don’t understand. There’s no one else to take care of my mom except for me. I cannot be in the hospital for one, two, or three weeks. I can’t ask a friend to all of a sudden be my mom’s caretaker.” That is a metric for that person. Not just having an optimized cure rate, but being able to live their life, and sometimes, their lives are very practically complex. They have to do things.

The results with bispecifics have been so promising. They’re great by themselves because they’re simple and well-tolerated enough that you can combine them with chemo. Now, bispecifics plus chemo start to have complete remission rates that are getting quite close to CAR T-cell therapy. We don’t have enough follow-up yet, but we certainly have seen a lot of relapsed DLBCL patients in remission for two to three years and coming up on four years now. We cannot say the exact cure rate with chemo plus bispecific versus CAR T-cell therapy, but it’s getting closer. And as Amir was saying, it’s much more doable in the community setting.

As you were asking about earlier, we do sometimes need that collaboration between the academic center and the community center because the first cycle of bispecifics can be tricky for some of the community centers. There are a few solutions, but one solution is doing the first cycle at the academic center in the big city, the subsequent cycles after that first month with the academic center, and the subsequent months with the community doc close to home, so it’s a lot easier. That model does exist. We do that sometimes. It might be doable for patients.

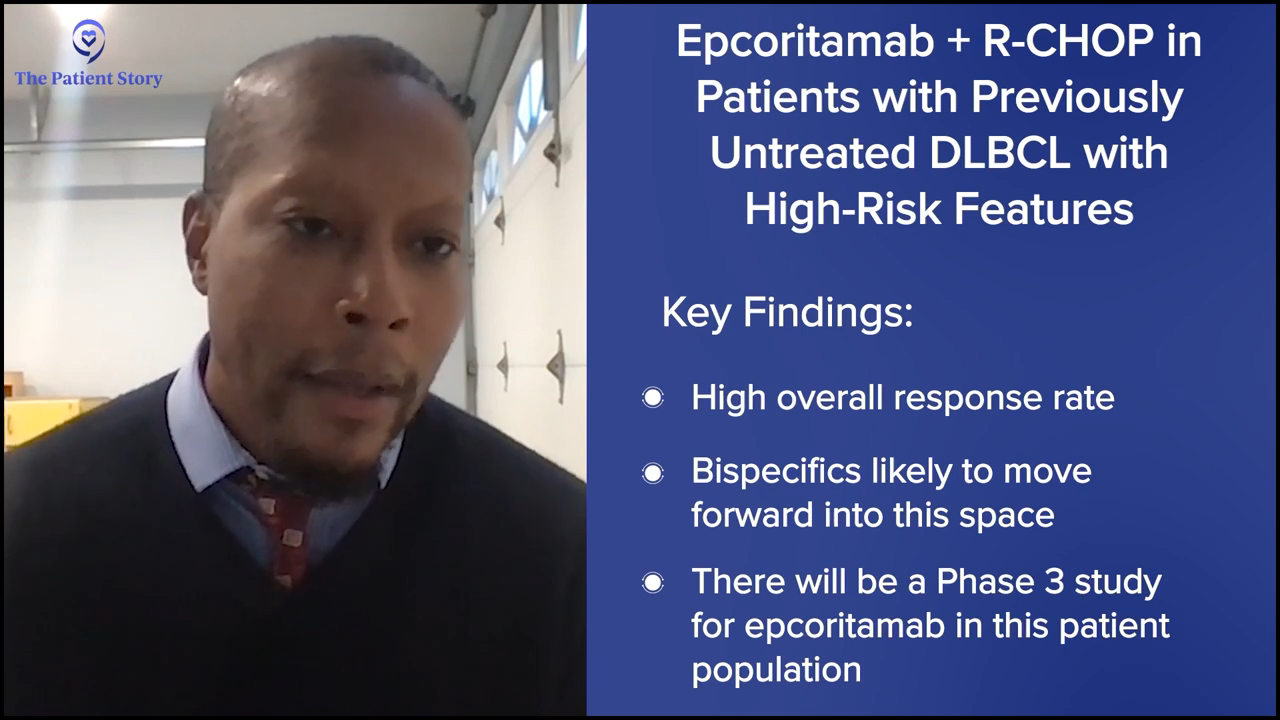

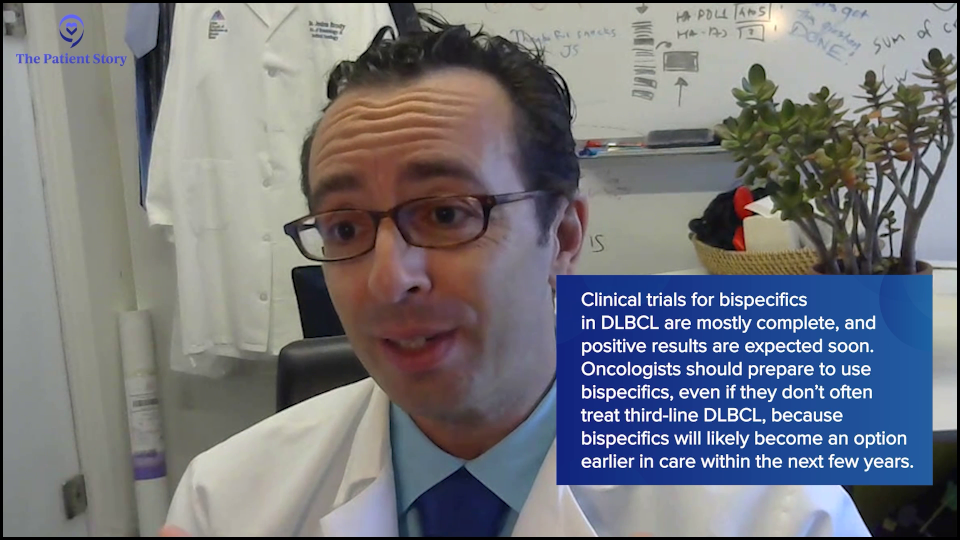

Dr. Steinberg: Bispecific antibodies may someday be approved in the front line in combination with chemo, so a lot of these community oncologists will be the ones treating the patients upfront. They’re getting their feet wet, so to speak, with these relapsed/refractory patients. In the future, who knows? Josh, do you have any thoughts on when they might be approved in the front line? I think it’s coming.

Dr. Brody: It’s coming soon because those trials are mostly fully accrued, so we’re waiting for the data. We cannot predict the weather in a year from now, but sometimes you can. If you’re in the Sahara Desert, it’s going to be dry. If you’re in the Amazon, it’s going to be wet. And these trials are going to be positive. That’s just me saying that with no secret insider information.

We’re talking to patients, but if there happens to be an oncologist in the audience, that oncologist is going to need to be able to be comfortable with these medicines. The oncologist might say, “I don’t see that much second-line or third-line DLBCL, so maybe I don’t need to learn about these bispecifics.” You do see first-line DLBCL. It’s the highest incidence lymphoma subtype, so if you’re going to be treating those patients, you will need to know about these a couple of years from now because they will be approved for the front-line, just as Amir was saying, so might as well learn about them now and solve some of these logistical issues about hospitalization.

Also, some of the companies that make the medicines are helping solve these logistical issues, so we can maybe change it so that most patients don’t need to be hospitalized for a day. Usually, for most bispecifics for DLBCL, patients need a one-day hospitalization. We might be able to get rid of that for a lot of patients in the near future as well.

Stephanie: Can you synthesize what you just talked about? What does it look like for someone going through CAR T-cell therapy in terms of the logistics versus bispecifics?

Dr. Brody: Amir, do you want to give your center’s approach to how long folks are in for axi-cel or liso-cel?

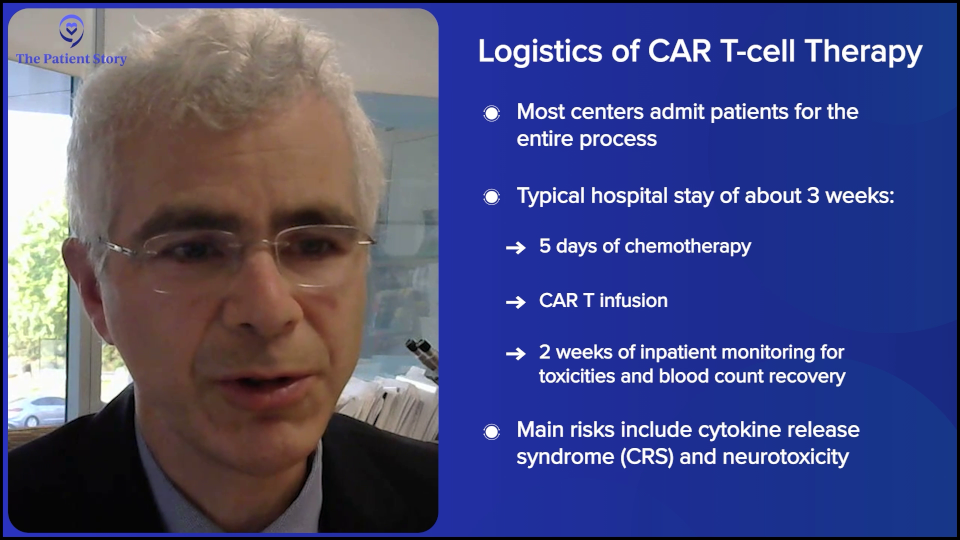

Dr. Steinberg: There are exceptions. Some centers may be doing outpatient CAR T-cell therapy, where they may give the infusion outpatient and then cross their fingers that the patient won’t be admitted or plan on the patient being admitted as soon as they exhibit side effects. But for the most part, I would say most centers will admit the patient and keep them there. We’re looking at a three-week hospital stay, with five days or so of chemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapy, and then an observation for two weeks or so until blood counts drop and then recover. You get them through all the toxicity and side effects, such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity. That’s the typical CAR T-cell therapy story. That’s why Josh was mentioning the patient who was the mother’s caregiver and couldn’t commit to three weeks in the hospital.

Dr. Brody: I totally agree. Some centers can do this outpatient, but that’s not the majority of centers. The reason is that it puts extra risk and concern when emergencies happen at midnight, unless you can set this up in such a way that the patient is across the street at a hotel and they have a great family member or someone who can keep a close eye on them and rush them across to the hospital. But that’s logistically difficult to set up in many centers.

At our center, it could be anywhere from a week and a half to three weeks on average — and that’s if everything goes pretty smoothly. If bad things happen, it could go much longer. It’s not nothing. CAR T-cell therapy is a super effective therapy, but these risks for adverse effects are not nothing.

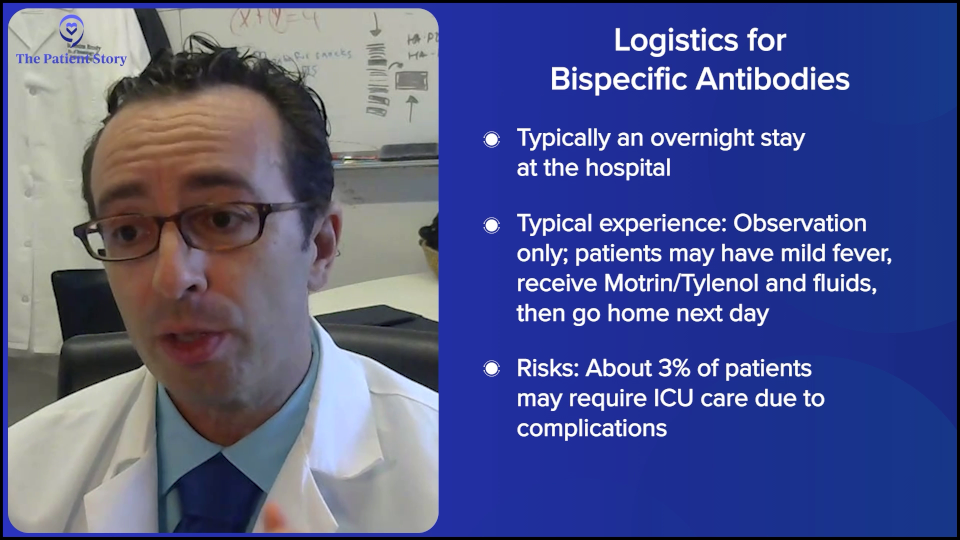

Stephanie: And then versus bispecifics, can you spell that out? They’re coming into the hospital… What’s happening?

Dr. Brody: Overall, the standard for most patients should be a one-day hospitalization — literally overnight. We can do that in a few different ways. On average, it’s one day for most patients. It could be more for some, but usually it’s one day of observation.

For most patients, it’s a pretty boring day. They got a fever, got some ibuprofen (Motrin) or acetaminophen (Tylenol), got some fluids, and then went home the next day. But maybe 3% of patients could end up in the ICU. Three percent is a lot, but for 97% of patients, it wasn’t that exciting. That’s for DLBCL bispecific antibodies.

We should just say, since we’re talking about them, that we have bispecifics for follicular lymphoma as well. It’s the same idea but with slightly different recipes. Those do not require any hospitalization. Some patients might need to get hospitalized for other reasons, but for most patients, there should be no hospitalization for bispecifics for follicular lymphoma.

Understanding Clinical Trials

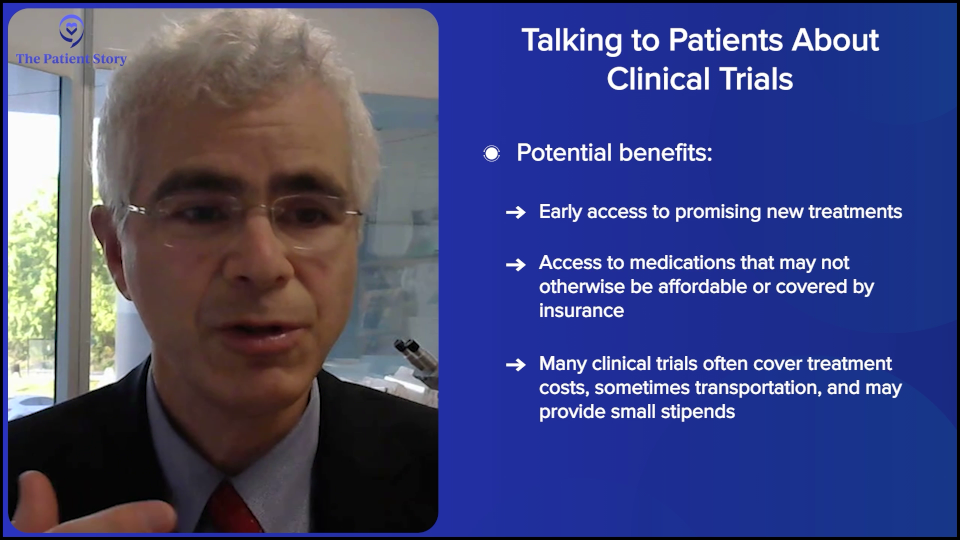

Stephanie: How do you introduce the concept of clinical trials while you’re talking to patients and/or their family members? How do you help them understand what they are?

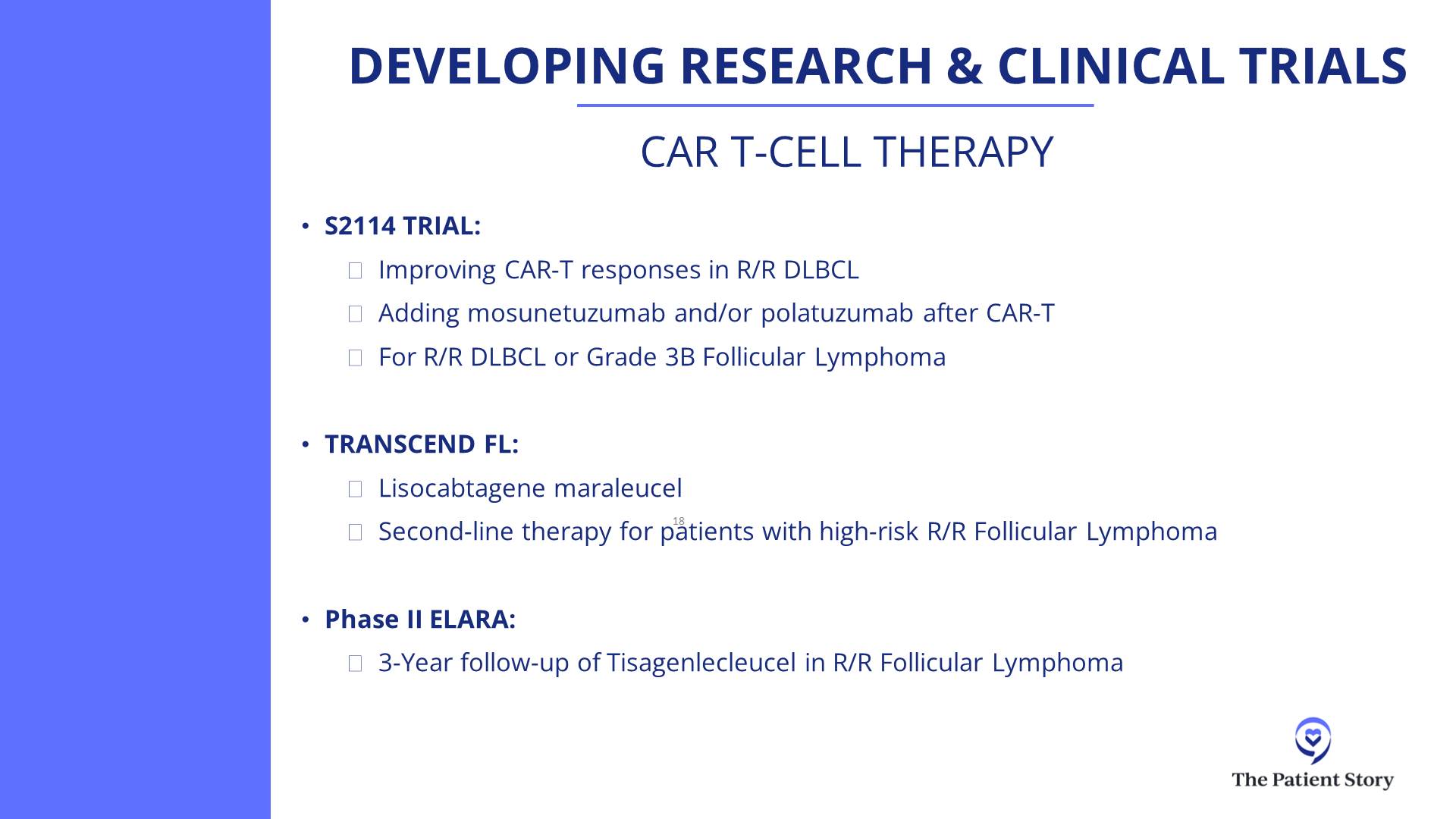

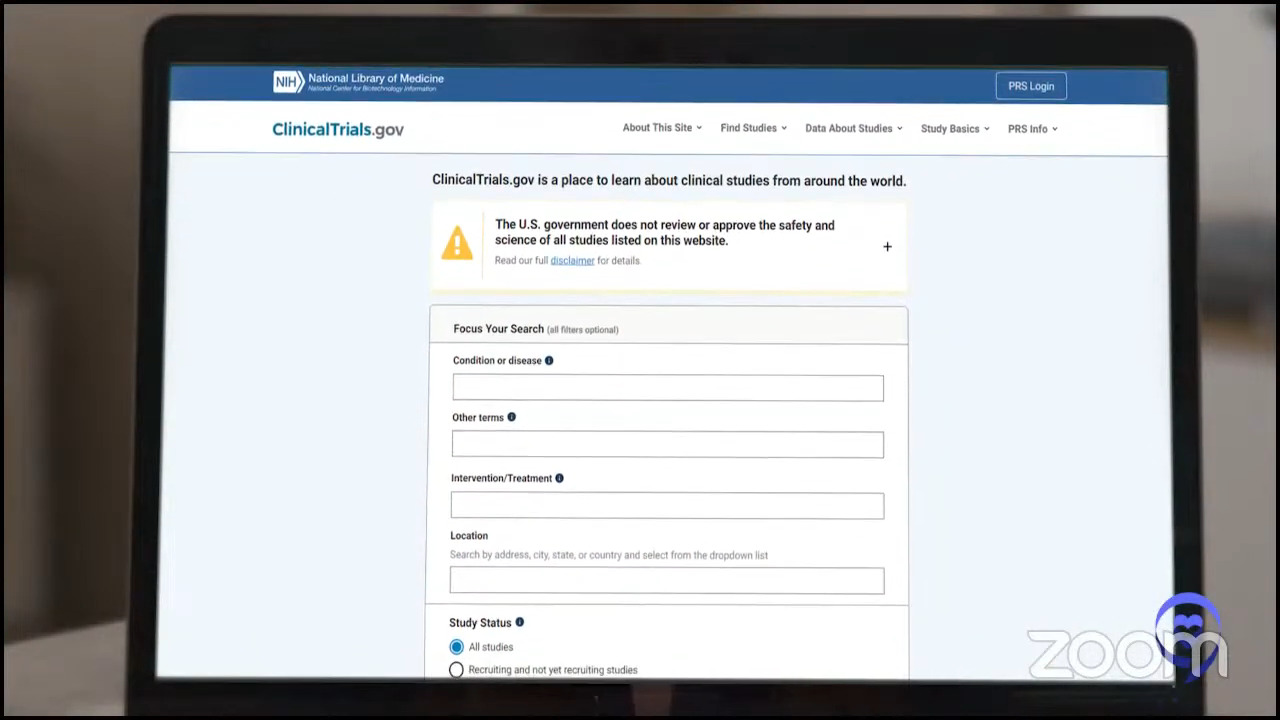

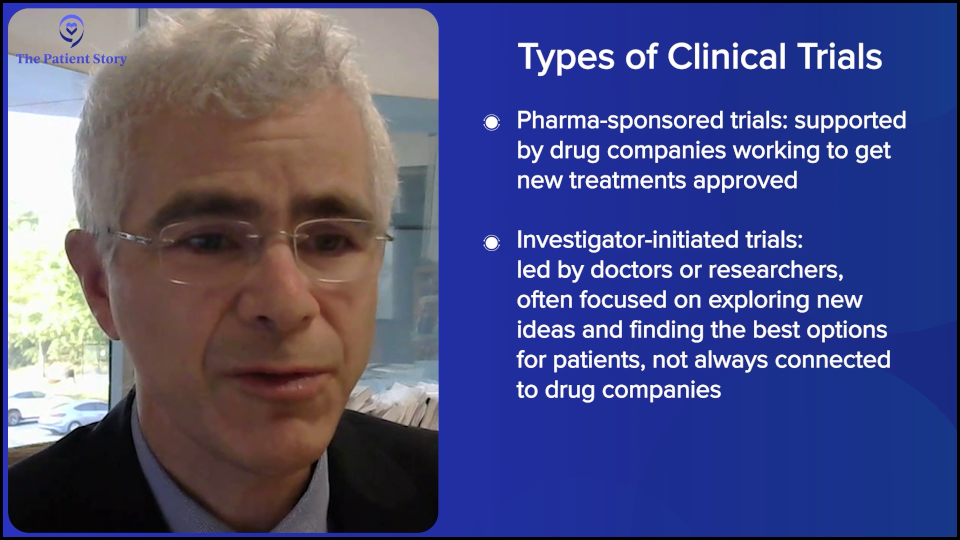

Dr. Steinberg: That’s a great question. We don’t have a clinical trial right now for front-line treatment for lymphoma. We do have two trials open for relapsed/refractory patients: one for epcoritamab (Epkinly) combined with traditional chemotherapy versus traditional chemotherapy alone, and another trial looking at zilovertamab vedotin, an ROR1 antibody-drug conjugate.

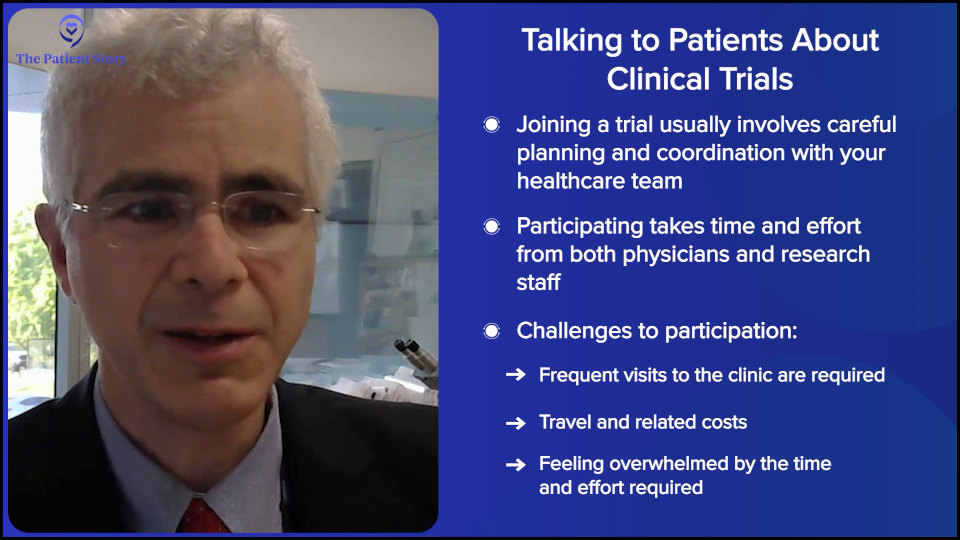

If I have a patient in those shoes, we always want to try and enroll them in a trial in the relapsed/refractory setting. This is not something where you can just say, “Oh, by the way, we have a trial.” I said it simplistically when I said I signed some papers when I joined a clinical trial. There’s a lot of time and attention that goes on behind the scenes. The doctor has to go through with a research coordinator and the institutional review board (IRB), which is a governing body that makes sure the study is safe in your institution and all the contracting that goes on. It involves a lot, and a lot of time and effort to discuss it with patients.

When the patients do get enrolled, it requires a lot of commitment on the patient’s part, which is why a lot of patients don’t enroll. Either we don’t think that they can make the frequent visits, or the patient doesn’t think that they can or want to commit to frequent visits and that’s sometimes the issue. I might refer a patient to the city from Westchester for a trial, but it’s too daunting for the patient to think about having to make multiple trips back and forth, sometimes even multiple trips a week. Maybe they live an hour away from my institution to enroll in a study that requires multiple visits.

But you weigh the difficulties of participating in a trial versus the potential benefits.But you weigh that negative aspect, the difficulties of participating in a trial, versus the potential benefits. What are the benefits? They may get early access to a medication that’s currently not approved in that line of treatment or a medication that may not even be approved, such as zilovertamab, the ROR1 antibody-drug conjugate, which has shown in studies to be an excellent medication, so now they’re trying to get it FDA-approved. That’s one of the benefits: getting early access.

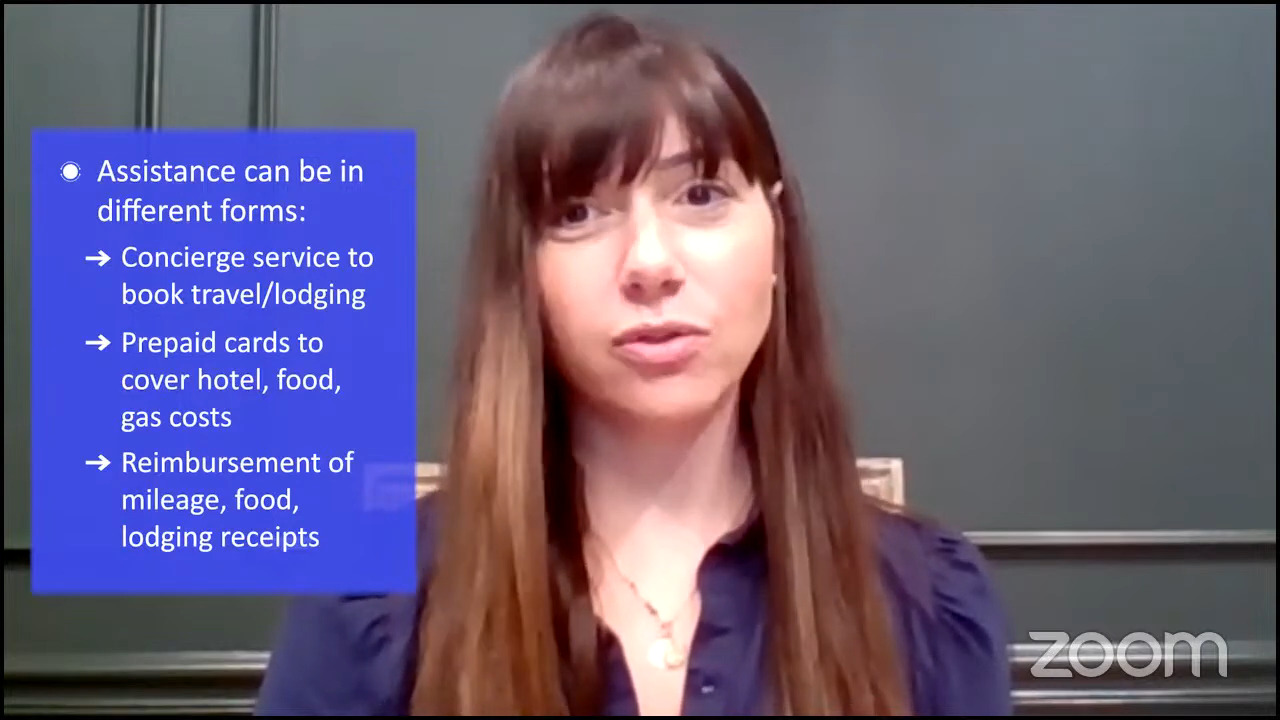

I’ve had patients who, for whatever reason, didn’t have insurance, so they weren’t able to get these medications. Any of the regular medications would have cost them too much money, but they happened to have a clinical trial where I enrolled the patient in and were able to get access to a medication that otherwise would have cost a fortune. You have to factor that in. These clinical trials will pay for a lot of the treatments for the patients. Sometimes, we’ll pay for transportation, or they’ll give a small stipend for the time and effort that patients put in.

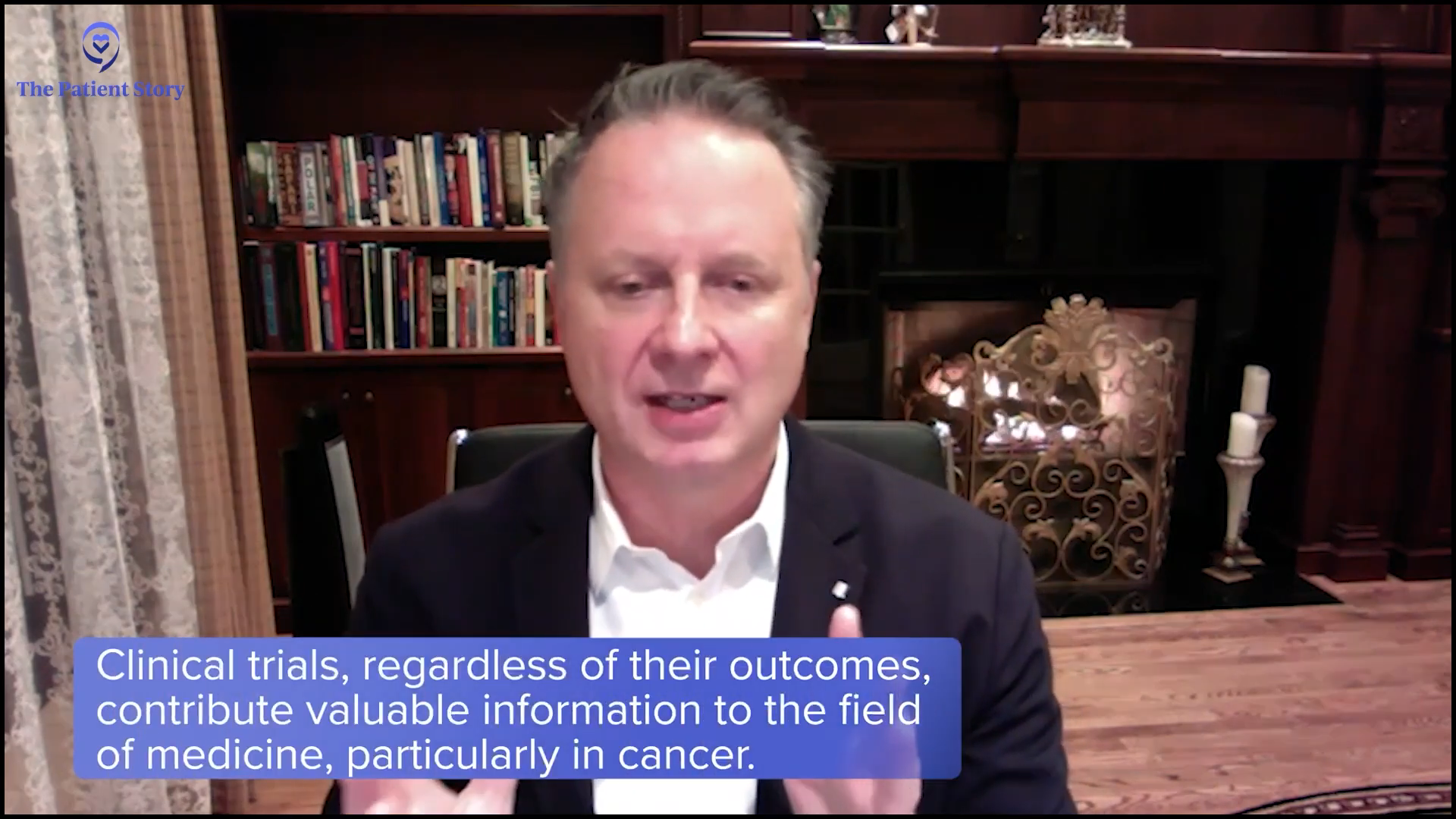

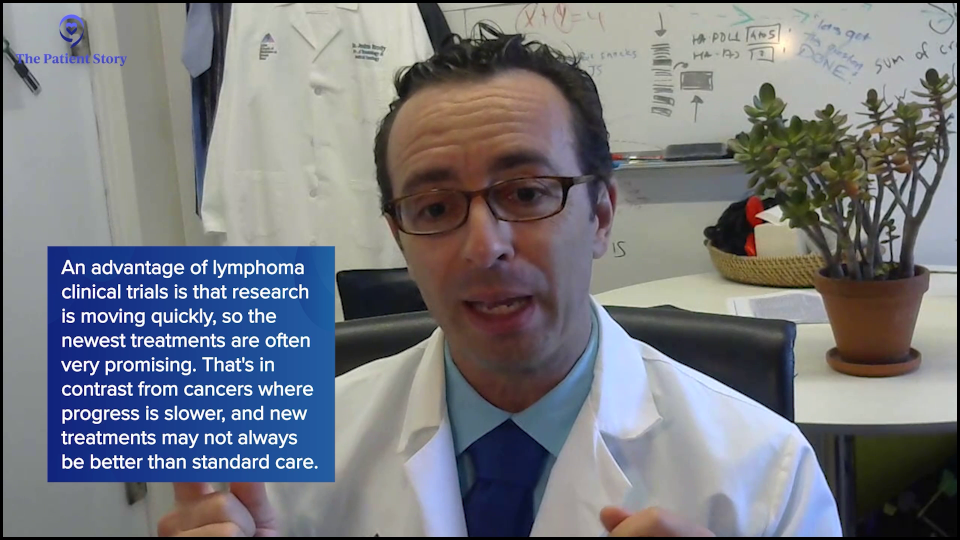

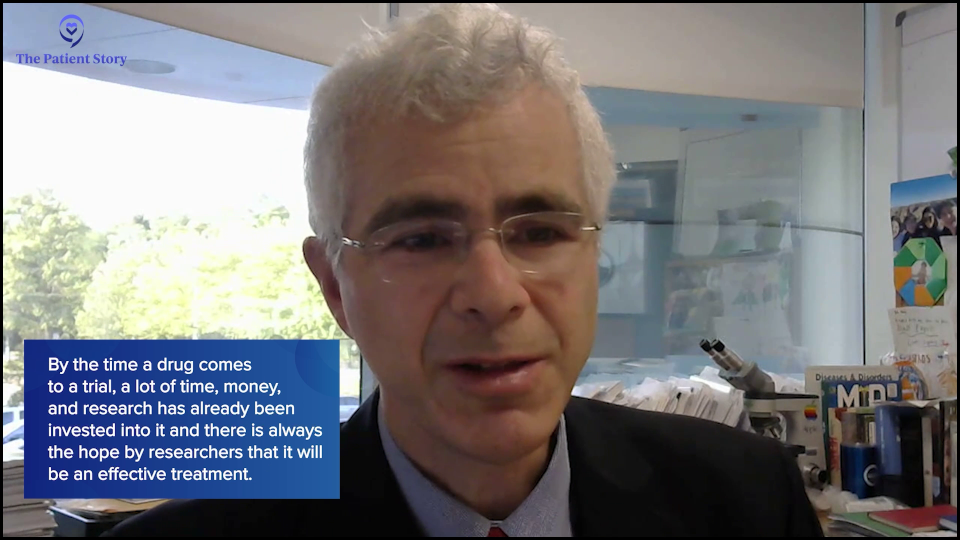

Dr. Brody: Those stipends where we pay for the travel costs have been very helpful for some patients because there can be more back-and-forth trips, as Amir was saying. Let me give a quick example of how clinical trials can work and, for many of them in lymphoma, how they do work.

I gave the example of chemotherapy plus bispecifics, which have been super effective and pretty well-tolerated for most patients because it tends to be gentler chemo and not super aggressive. Some of the combinations of gentle chemo plus bispecifics are just getting approved this year. As I was hinting, they were approved in Europe even before the U.S., so far, but are now getting approved in 2025, yet we have patients who got access to these medicines in 2021 and 2022. It’s like they had a time machine and were able to get future medicines years before they could have gotten them.

In lymphoma, we’re very lucky because there’s so much progress. Frequently, the newest medicine is the best medicine. In other cancers, that is sometimes the case. In pancreatic cancer, a very terrible cancer where our progress has been slow, the clinical trial may have something better than what’s already there, or it may not as they are not making as rapid discoveries as we happen to luckily be doing in lymphoma. But frequently in lymphoma, the newest medicines are the best medicines, so getting access to them four years ahead of time — if the goal is to live and to live well — is a huge opportunity.

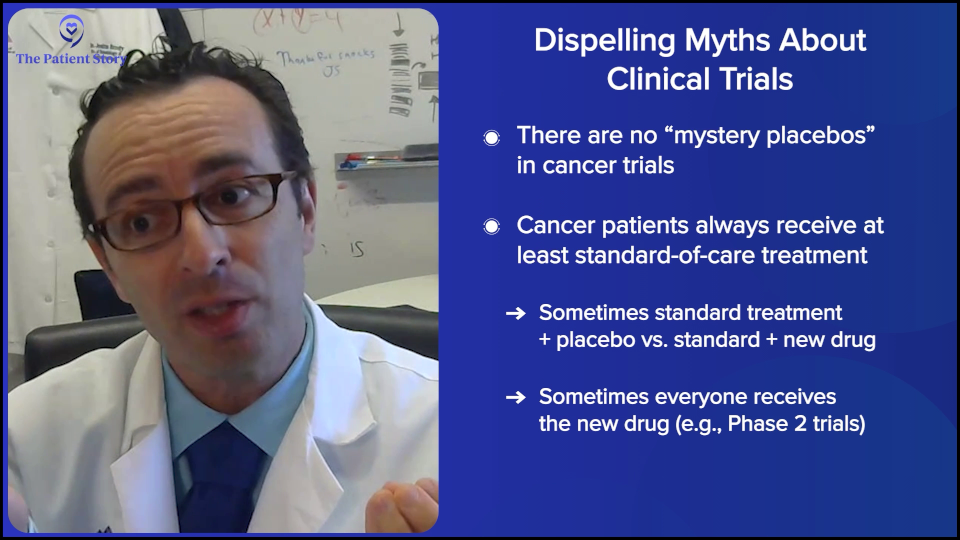

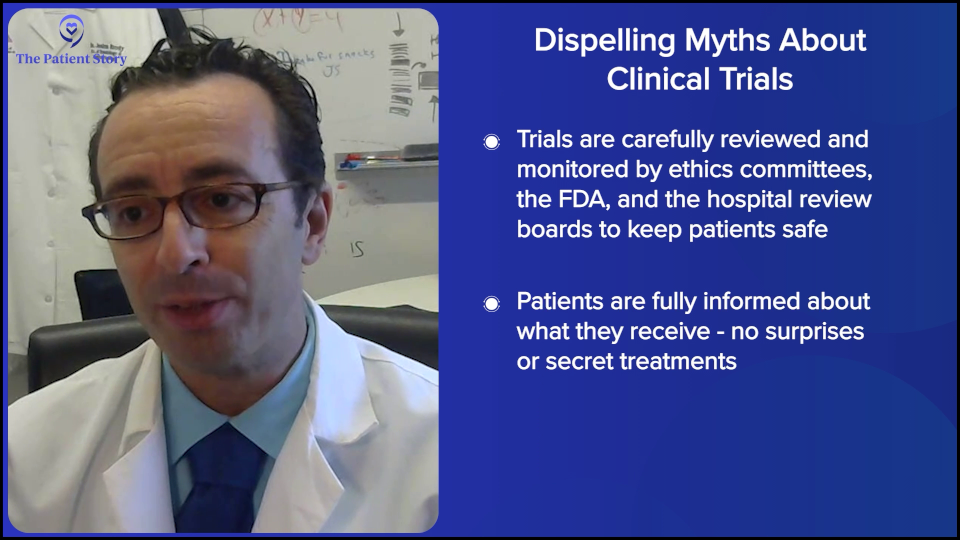

We must always dispel myths about clinical trials. Patients always say, “Oh, wait, I could get some kind of placebo and get nothing.” There are no bizarre mysteries. As Amir was saying, we have ethics committees such as the IRB that oversee everything, so doctors and drug companies can’t do a trial just because they feel like it. They have to have everything approved and the ethics committees can be quite on top of it. They know all the details. They want the 167 pages to actually be 169 pages because they want you to put in more information so that the patients are well-informed. They are overseeing pretty rigorously. That’s the local IRB, and then you have the FDA as well. These local IRBs are either in the hospital or nearby, making sure that these things are, hopefully, healthy and safe for patients.

There is no mystery placebo where you may get something or not. Maybe there’s a placebo trial for toe cream or something. But in cancer, there are no random placebo trials because everyone is either getting the standard of care plus more. Should there be a placebo, you get the standard plus placebo. You’re already getting the standard treatment or the standard plus something new. That can exist. We tell you which one you’re getting, but sometimes, even we don’t know until the end. But you’re at least getting the standard therapy for sure.

Most trials are earlier phases, like phase 2 trials, where everyone gets the same treatment. There’s no mystery. Everyone knows what you’re getting. The doctor will explain to you before you get started. There are no surprises, which is an important myth to dispel for patients because that’s something that intimidates folks to ask about clinical trials.

Dr. Steinberg: Whenever possible, we try to offer trials because that’s how we advance the science and get higher cure rates. They’re essential. And as Josh alluded to, sometimes these medications are available a few years in advance.

When I first joined Westchester, I referred a patient to him who got access to a medication that wasn’t FDA-approved yet and that patient was able to receive it and did well. Otherwise, whatever other options were available weren’t quite as good as what this particular patient could have gotten through the trial. That’s what patients have to be aware of.

They’re not going to offer you some bogus medication that’s not going to work. When they’re testing, there are millions of dollars being invested in testing this medication, meaning there’s a high chance that they’re hoping that this is going to work and that this medication will work. Many years of time and effort have gone into researching these drugs. They’re not experimenting on people for the sake of it. They’re experimenting because they want patients to do better — because hey, capitalism — and if that drug is approved, then the company is going to do quite well, so there’s an incentive for that company to offer that medication.

There are non-company trials as well. There are trials that benefit the researcher. They’ve dedicated so much time and effort into developing a new treatment that, to them, it’s a passion, and it’s a passion that the medication or treatment they’re developing succeeds. Maybe they were devoting their whole life to lymphoma treatment because there was a family member who had lymphoma, or because they find that science so interesting and they want to do it for the joy of helping others.

It’s not always pharmaceutical. Sometimes, you could find investigator-initiated trials (IITs) where they’re making brand new medications that aren’t pharmaceutical-sponsored, so patients should be aware of that. They’re not randomly getting A, B, or C. There was a lot of thought put into this.

Stephanie: I appreciate the myth-busting.

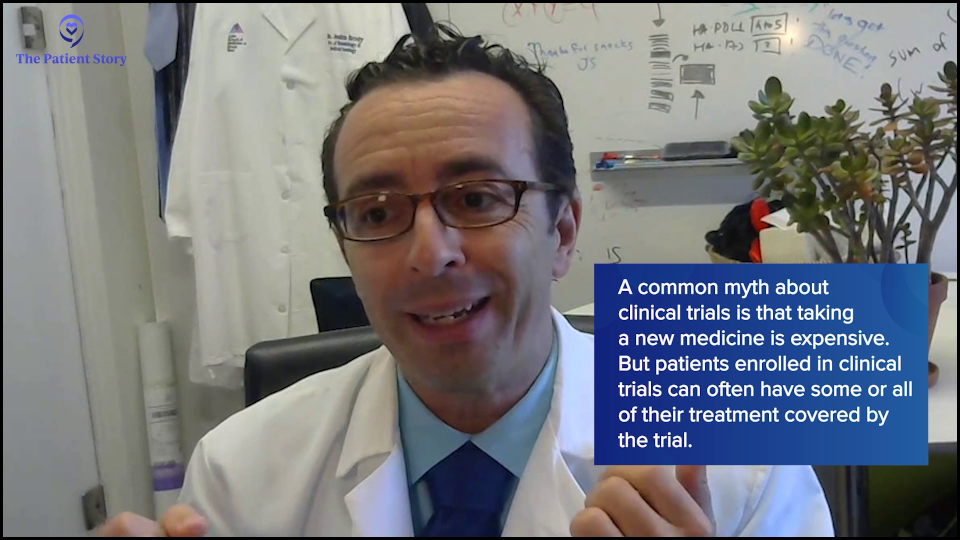

Dr. Brody: Stephanie, just because Amir mentioned the money, let me say something about that because patients do ask us this frequently as well and we have to speak plainly about this. Patients will frequently ask, “Wait. The new medicine could be hugely expensive. And because it’s a trial, my insurance will not pay for it.” That’s an absolute myth.

Every medicine provided on trial, if it’s a new medicine and not the old standard, is 100% covered by whoever is doing the trial, whether it’s the investigators or the company, so they usually end up being cheaper. The patients may have had a copay if they were getting a pill of some type, like a BTK inhibitor or a BCL-2 inhibitor, and those will now be free instead of having a copay or whatever the patient was going to pay. Everything that is in any way nonstandard always gets paid 100% by the trial.

In addition, they also sometimes give a nice stipend to help the patients get back and forth. That’s another common misconception: “My insurance won’t pay for this because it’s in trial.” Your insurance doesn’t have to pay because it’s going to get covered automatically. Insurances sometimes still have to pay for routine scans and tests when they’re part of a trial, but anything nonstandard is free. That’s an important thing for patients to be aware of.

Dr. Steinberg: To piggyback off of that, I’m going to use my father as an example. He was enrolled in a trial that used lenalidomide (Revlimid). Had he not participated in the trial, it still would have been the standard treatment for him for follicular lymphoma, which would have cost him a fortune in copays. But because it was the standard arm option in the trial, even though it wasn’t the experimental arm, it got covered, so he got the Revlimid paid for, which he couldn’t have gotten otherwise. Don’t quickly dismiss a trial. Think about all the considerations and ask your doctor about the coverage.

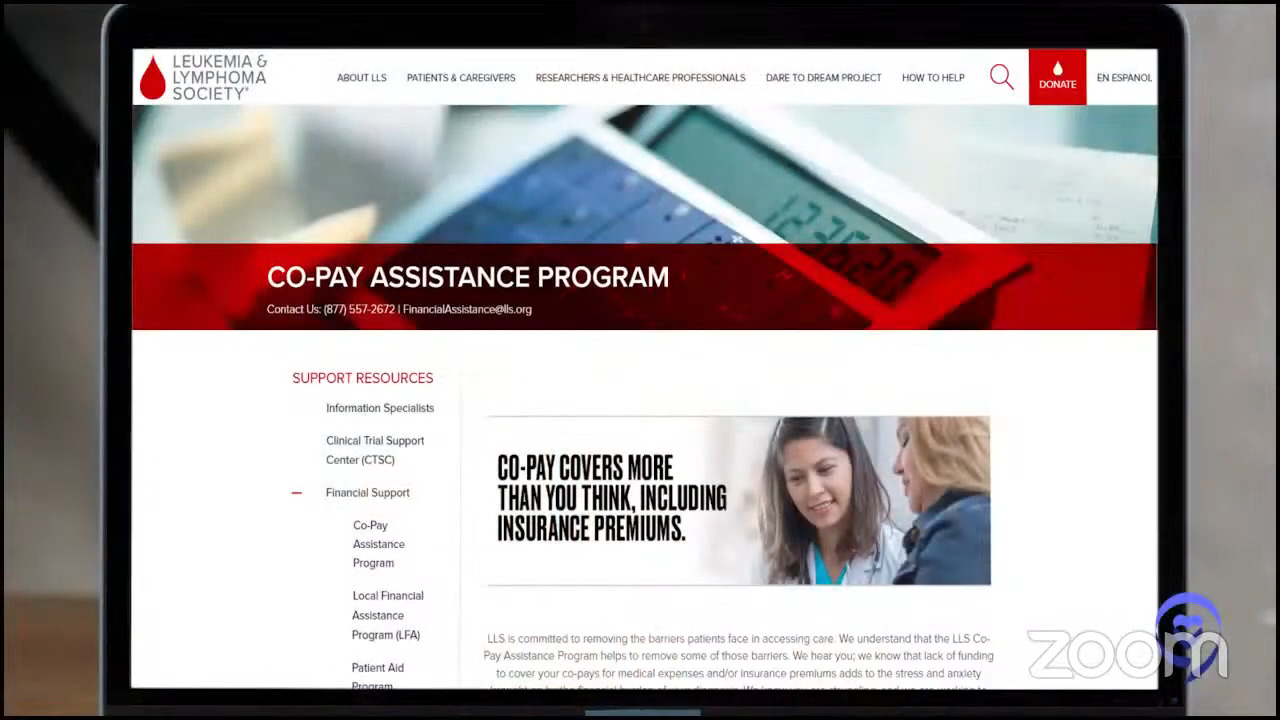

Stephanie: I truly appreciate all this myth-busting because there are lots of misconceptions and I know there’s a lot of effort in trying to help support patients get to clinical trials, whether it’s the investigator or the pharmaceutical companies trying to cover costs. We have friends at Blood Cancer United (formerly The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society), where they have programs and grants to help cover things like travel or lodging.

Working with Your Care Team

Stephanie: There’s so much information available. You two are incredible specialists and anyone would be lucky to see either of you. Who else is also on the care team for patients and care partners? They have questions about insurance, coverage, lodging, logistics, side effects, and managing them. When I was going through it, I spoke with my nurse a lot about how to manage side effects in different ways. At your centers, how would you describe the care team to patients?

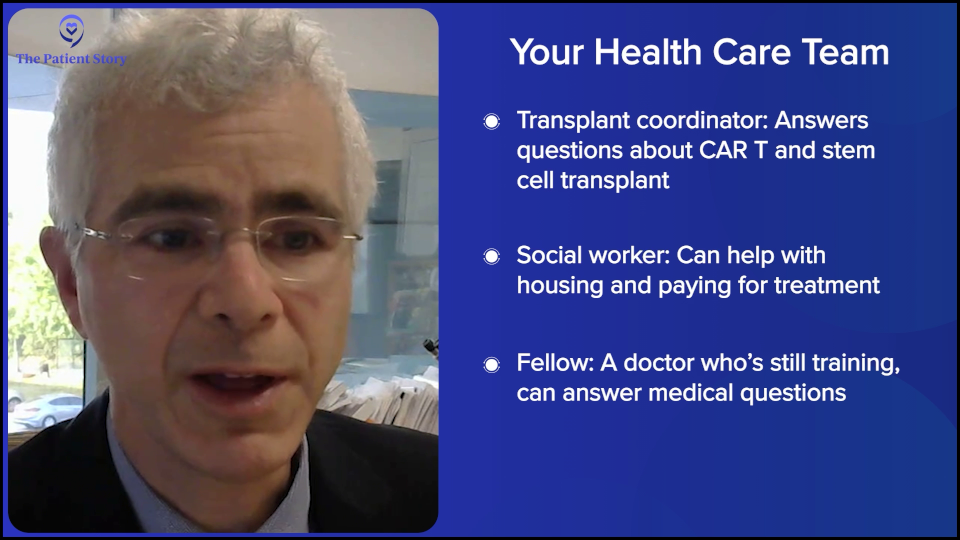

Dr. Steinberg: We call them transplant coordinators, but they’re really our cellular therapy coordinators. When it comes to discussions about CAR T-cell therapy or autologous stem cell transplant as a potential treatment option for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, they’re great resources. They give our patients their cell phones, text with them all the time, and answer any quick, immediate questions they may have.

Also, the social worker is a fantastic resource in terms of finding housing and coverage for medications that patients might need. I will sometimes fill out Blood Cancer United (formerly The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society) grant forms for patients so that they can get these medications covered. Those are the two big people with whom I work closely. Sometimes even the fellow. If they happen to see a trainee hematologist-oncologist, they’ll sometimes develop a connection with that fellow who can help answer their questions as well.

Dr. Brody: As Amir was saying, it’s a team — and it’s not just a diplomatic thing to say. If it weren’t a team, the whole thing wouldn’t work at all. We have nurse practitioners, registered nurses, dietitians and nutritionists, social workers, and holistic therapists — a connected part of the team, but not built right into it because a lot of patients ask about that. We’re lucky to have easy access to all of these resources.

If it were just the doctor by themselves…, oh my. The patients depend heavily on communication with our nurses, nurse practitioners, and the rest of the team every day, sometimes.

Conclusion

Stephanie: Thank you both so much for your time. Is there anything you’d like to end with and share with patients and care partners on what’s happening in DLBCL?

Dr. Steinberg: Thank you for having me. Certainly, treating lymphoma patients is a passion of mine. There’s so much that’s changed in the last 20 to 30 years, most especially in the last five years. Things are changing for the better so rapidly for patients. As doctors, we have so much to catch up on and stay up on in terms of the knowledge out there, but it’s totally worth it because it will make patients’ lives better and more fulfilling.

Dr. Brody: Agreed, agreed. We’re very lucky to have you, Steph, and The Patient Story team as you try to get information out to patients. Information is power and the patients could use some power in this scary setting. In line with that, I’ll answer a question from before. What else should patients ask their doctors? Here’s the important thing: ask whatever you want. Do not in any way put doctors or nurses on a pedestal where you cannot ask a dumb question. People say there’s no such thing as a dumb question. There are, but don’t worry about it. Just ask them. It’s okay. If they go in the back room after and make fun of you, fine. At least you got your question answered. Don’t be shy to ask questions of your doctor and the nurses. That’s what they’re getting paid to do: to answer your questions.

Stephanie: I appreciate the humor, especially when we’re talking about something like this. Again, Dr. Amir Steinberg from Westchester Medical and Dr. Joshua Brody from Mount Sinai, thank you so much for being here.

We hope that this discussion has helped you consider all your treatment options, how to navigate different systems and centers, and walk away with questions for your healthcare team. On that note, while this conversation is meant to be helpful, it’s not a substitute for medical advice, so please still consult your doctor and healthcare teams.

We want to thank our sponsors, Genmab and AbbVie, for making this program possible. Their support helps us to host more of these. We want to note that The Patient Story maintains full editorial control of the program.

Finally, we want to know how you felt about this discussion. Was it helpful? How was it helpful? What would you like to hear more of? What could we do better?

I’m very glad that you were able to join us and we look forward to your feedback. I hope that you’re able to join us for another program in the near future. For now, thank you and take good care.

This program has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.