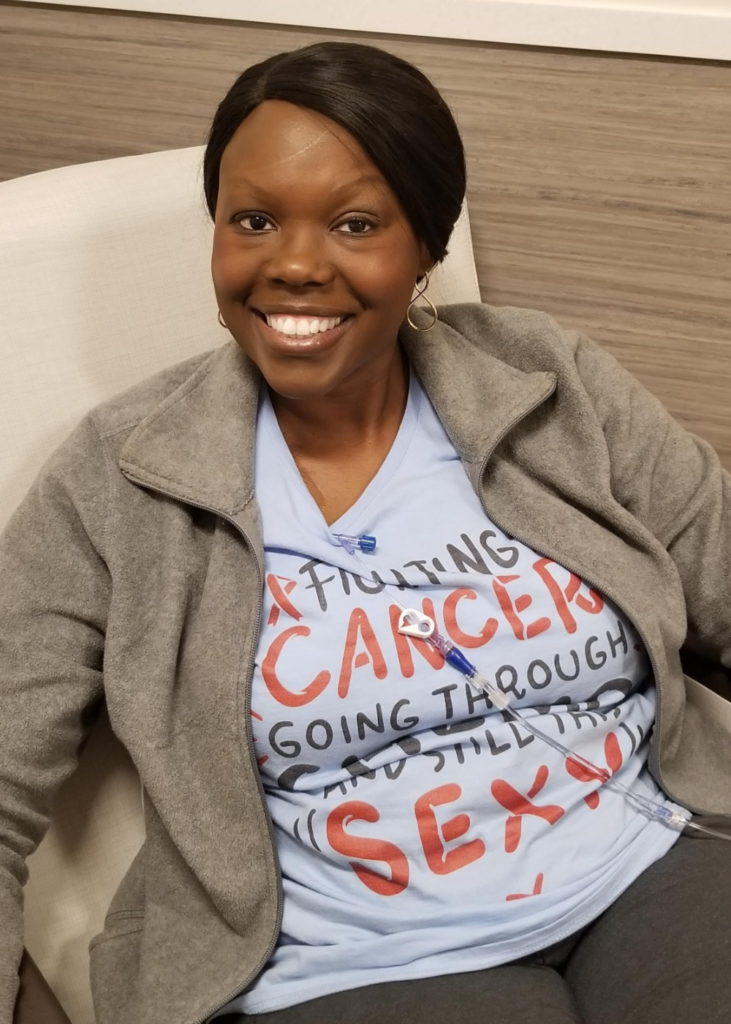

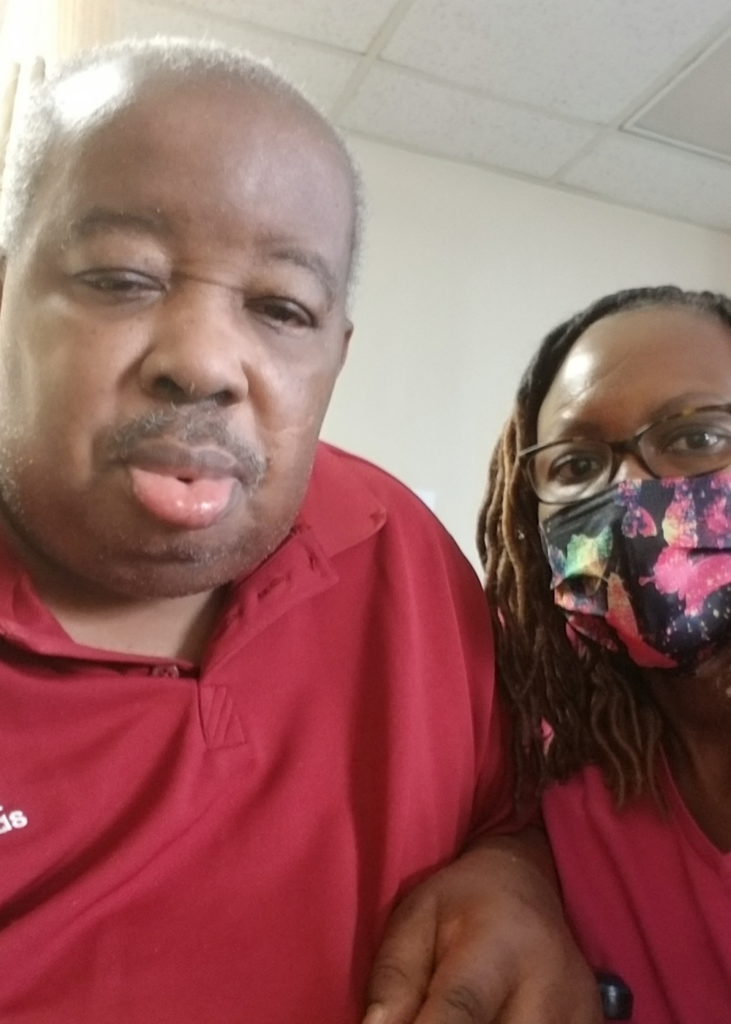

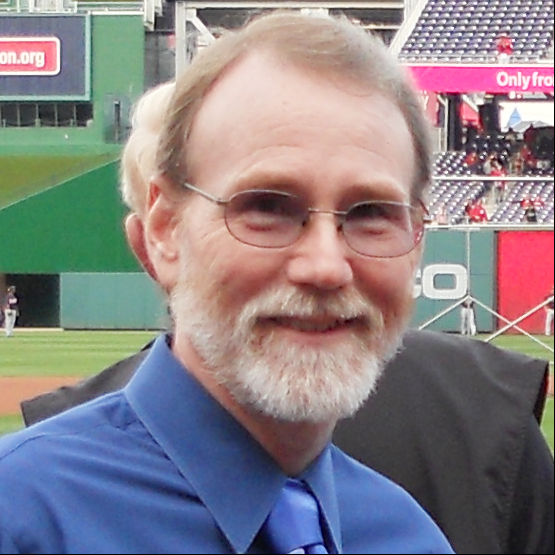

Marsha’s Caregiver Story

When Marsha Calloway-Campbell learned her husband was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, it turned her world upside down. But since his diagnosis, she’s rarely left his side, which at times takes a toll on her health. A myeloma caregiver, she’s learned how to find community support and advocate for her husband.

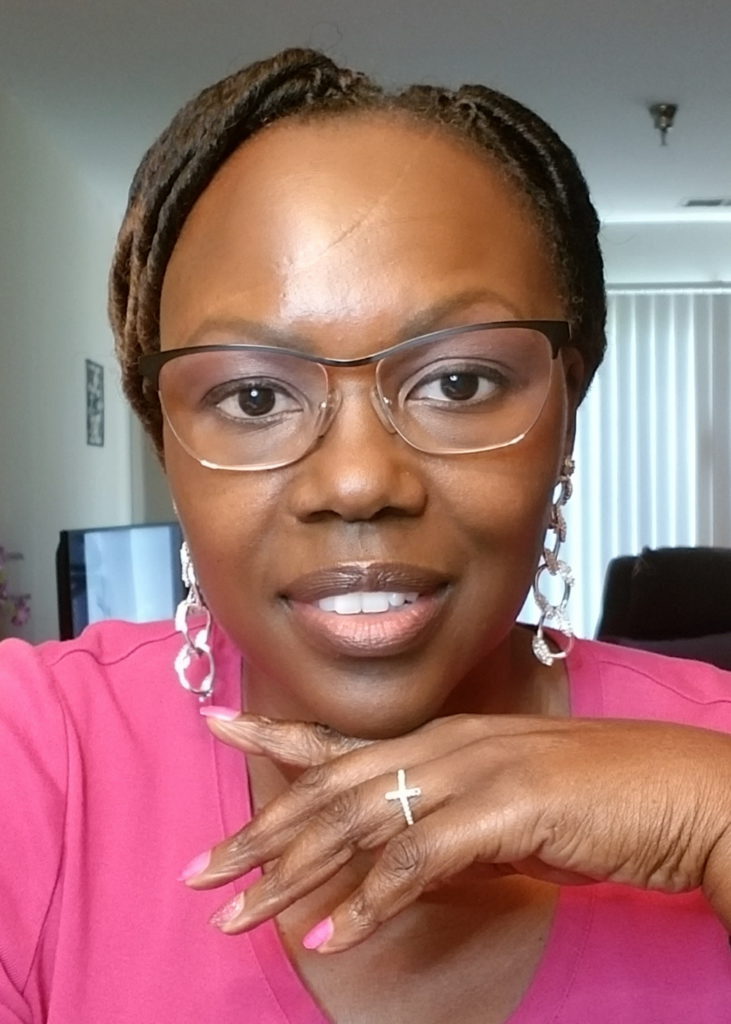

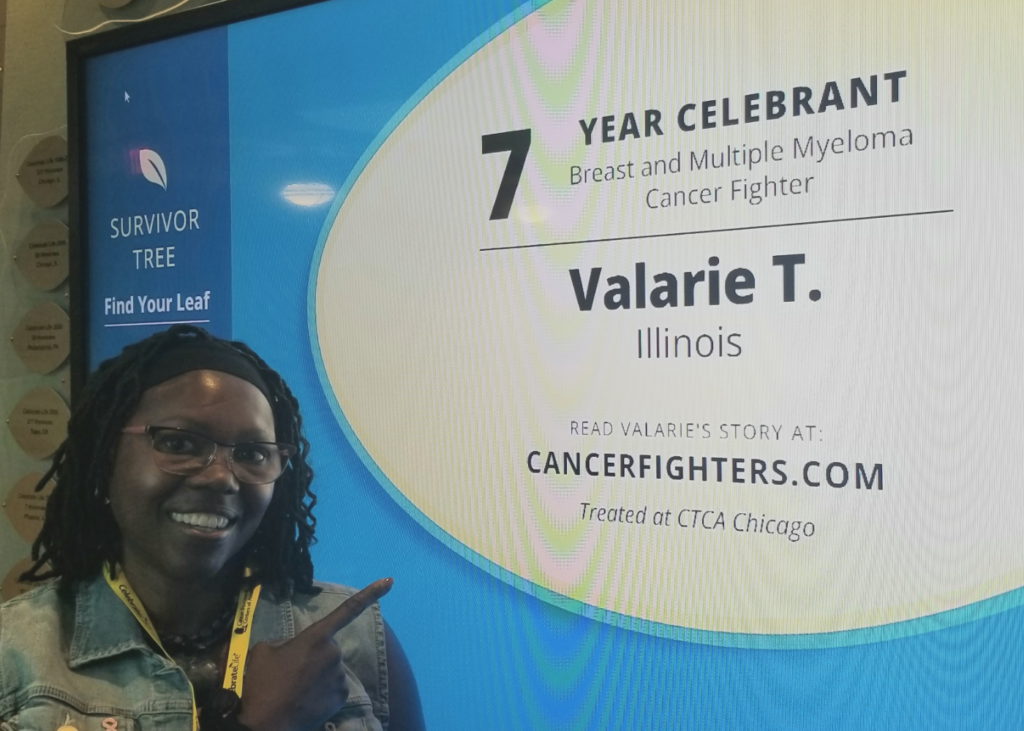

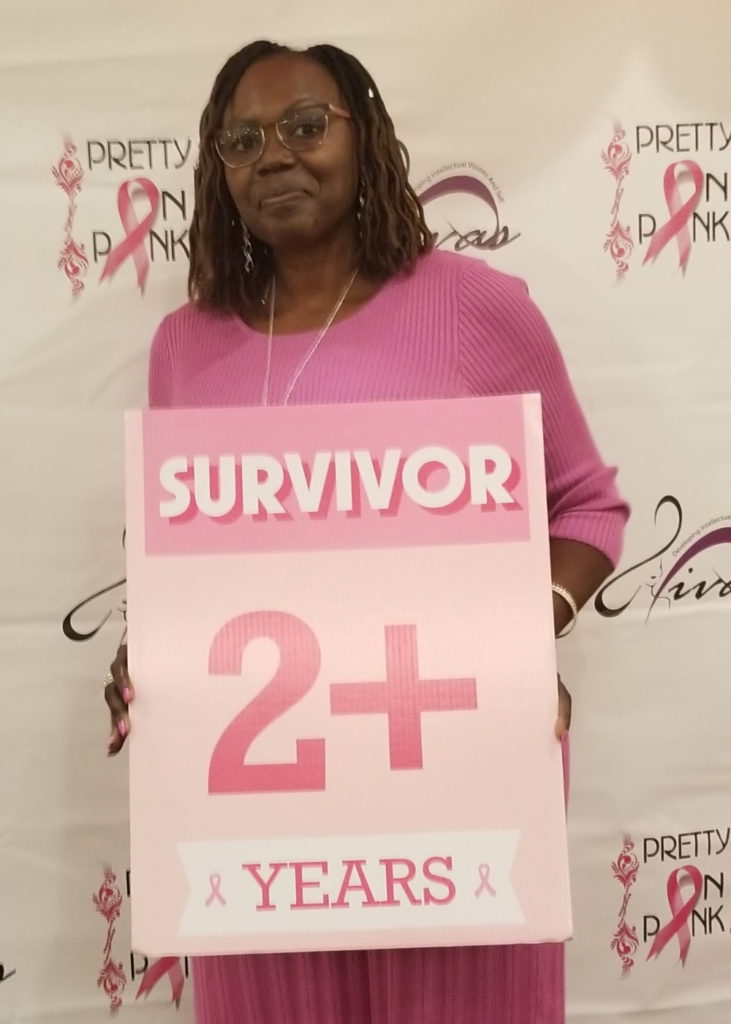

As the Program Director of HealthTree’s African American Multiple Myeloma initiative, Marsha has a passion for empowering others. She works to address the many obstacles African Americans face in myeloma diagnosis and treatment.

She voices how she took on the role of caregiver by taking on many burdens, how she made sure her husband was getting the best care and treatment, and how she got through the heavy emotions weighing on her.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Introduction

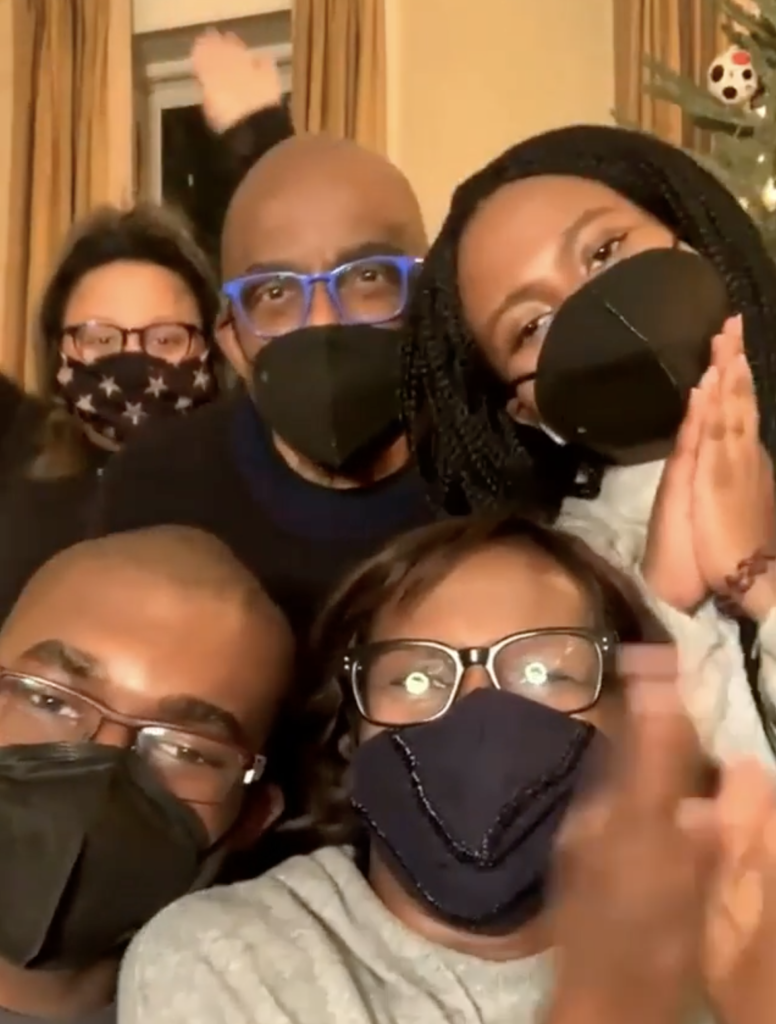

I’m a wife. We were high school sweethearts.

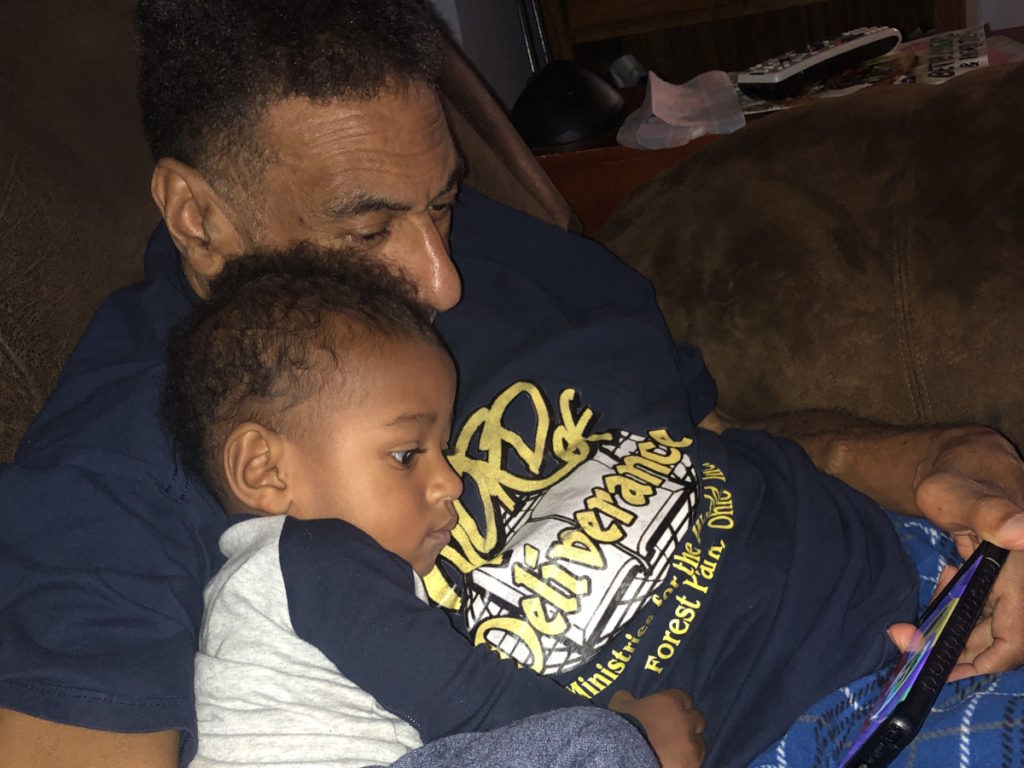

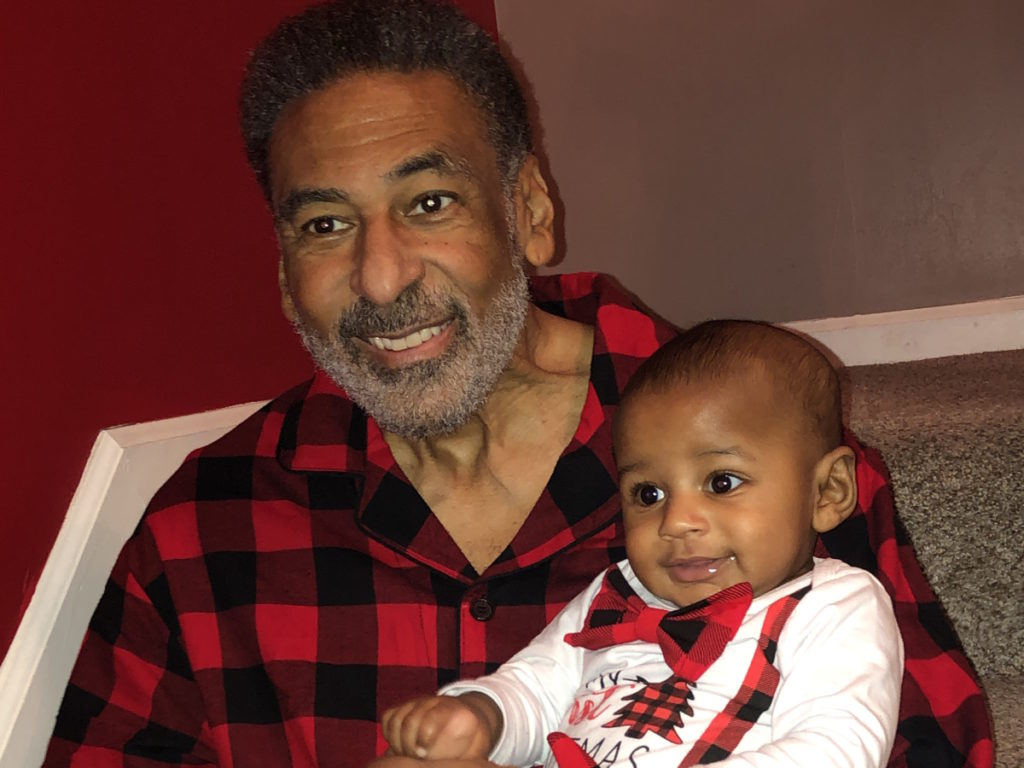

I’m a mother of three daughters and a grandmother of a grandson.

Professional, career-oriented, type A overachiever, a Christian, a believer, [and] a family woman.

Pre-diagnosis

[Our] household was crazy busy. [Out of the] three daughters, one dances competitively. We drove all over the US with her. Six years later, her sister came and 20 months later, another sister came.

The two younger ones were athletes. They played basketball, soccer, volleyball… We let them try everything. Then we got into travel ball. There were times that he would put one in the car to go to Atlanta. I would put another in the car to drive to Chicago.

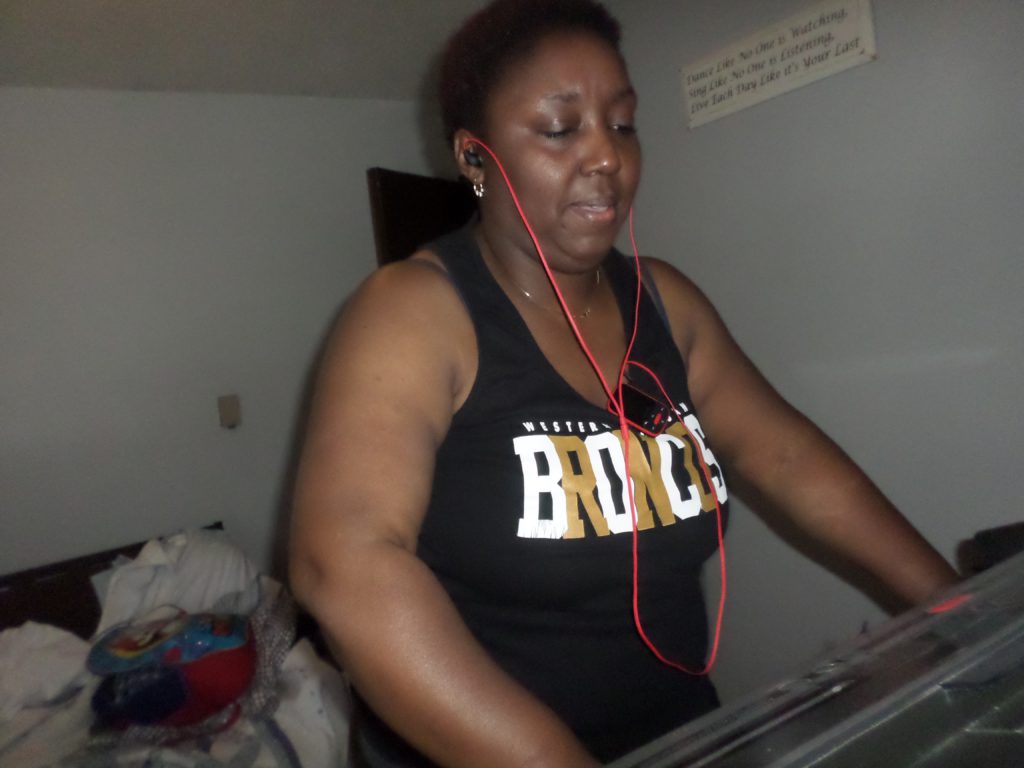

We were gym rats. He was an athlete. I played ball in high school. It continued even into college for the two younger ones. They were student-athletes. That’s the synopsis of us before. Let’s call it 2016. And that’s when he started not to feel well and things started changing.

Initial myeloma symptoms

Armaray is a Black man. I say that because many Black men don’t go to the doctor, but he did. He got yearly physicals.

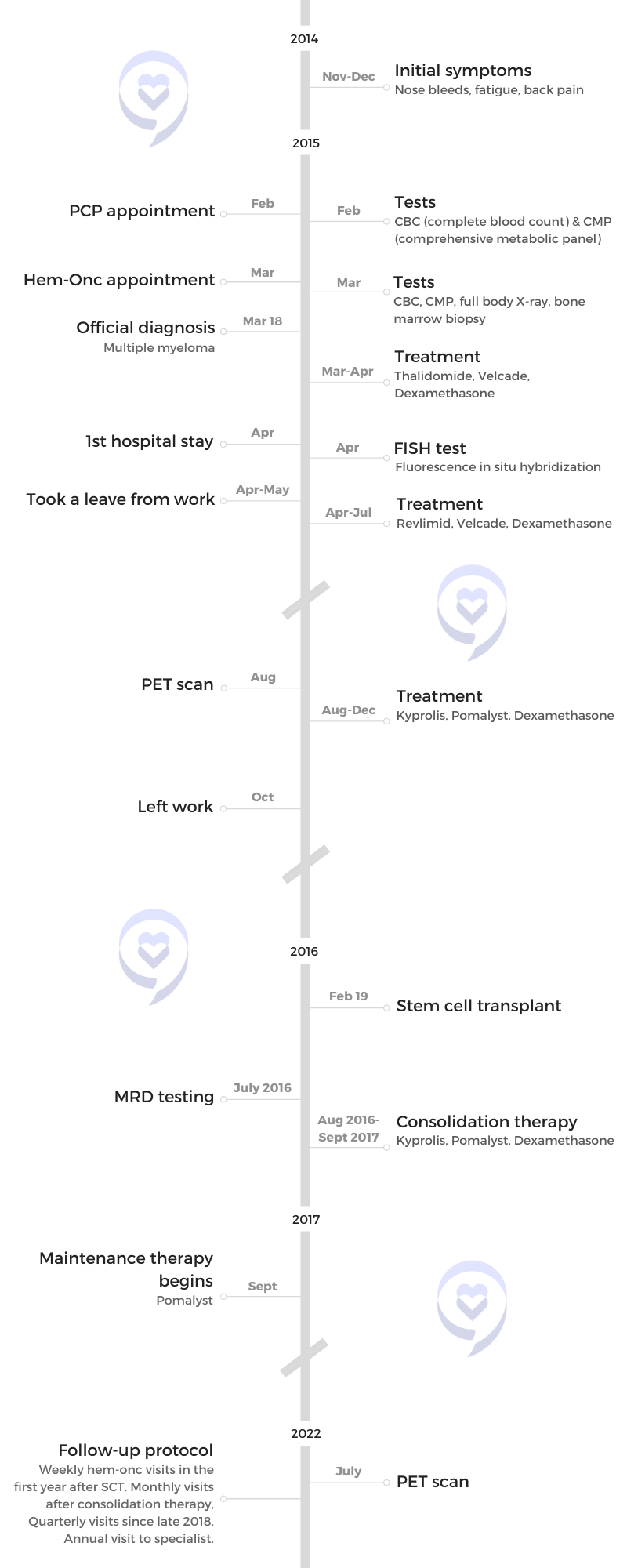

In 2016, he had gotten a physical, probably July-ish. August [and] September came. He started not to feel well. He started seeing other doctors. He was 57 at the time. They said he had a slightly enlarged prostate. They said, “Go to a urologist.”

Nothing was making him feel better. We get to Thanksgiving. He stayed in bed the whole weekend. We just knew something was going on. We went to his general doctor.

Right around Christmas is when I started getting real concern and pushing his primary care. He told me, and I remember it like it was yesterday, “It looks like Armaray has some compression fractions in his spine.” We’re like, “Why? Where is that coming from?” He had been an athlete and had had some surgery in 2015, but for an L4 and L5. Everything was fine.

He started wondering, Is it related to that? Still, no one knew. They said, “Okay, let’s get scans. Let’s do physical therapy.” Put him in physical therapy. “Let’s get that TENS unit for the pain.” We did all of that. Armaray trying to stretch his back out, thinking that will help.

New Year came and [on] January 12th, he almost collapsed as we were about to go to physical therapy. Instead of driving him to physical therapy, I drove him to the ER. Pulled up at the door, went in, and said, “I need a wheelchair,” and that was that’s the beginning of that story.

Within an hour and a half or so, I heard that ER doctor say, “Put him in room 10.” I go up and say, “Oh, good. You’re admitting him.” He just looked at me [and] said, “Oh, yeah.” I saw the concerned look. He said to me, “How long has he had kidney disease?” I said, “He doesn’t.” And he said, “Well, he does. His kidneys aren’t working.”

Armaray, even at 57, was still the athlete. He worked out four, five, or six times a week. [At] 6’2” and 195 pounds, [he] ate better than anybody in the household. He took care of himself, was not on any kind of medication, no blood pressure medication, nothing.

The nephrologist was called in and they ended up saying to me, “His creatinine is 14.” That didn’t mean anything to me. But she looked at me and said, “It should be under 1. I don’t know how he’s standing.” That’s when the ER doctor looked at me and said, “It might be multiple myeloma.”

I was like, “Okay, but what is that?” I remember saying inquisitively, “Is that cancer?” And he said, “Yeah, I’m not sure yet.” Then he tried to walk it back a little bit, but the nephrologist was standing there and she said to me, “One of my nurses has it.” She needed to let me know that it was not necessarily a death sentence.

She said, “We’ll figure all this out later. I have to get him into dialysis.” They worked their magic. They got that catheter put in and he was [put] in dialysis that night. We stayed in that hospital for one solid month because things were happening fast.

I slept in that hospital every single night, but two nights. I was afraid that if I left, a doctor was going to come in and tell him something else.

Realizing he had to be admitted to the hospital

[With] all of those things they were doing, I knew I had to call people. At that time, the oldest daughter was a senior in college, living in the city. The two were in school, one was a senior [and] one was a sophomore in the middle of basketball season.

I knew I had to tell my mom, who was in her 80s at the time. Keep in mind, she’s known him since he was 17. He’s like a son.

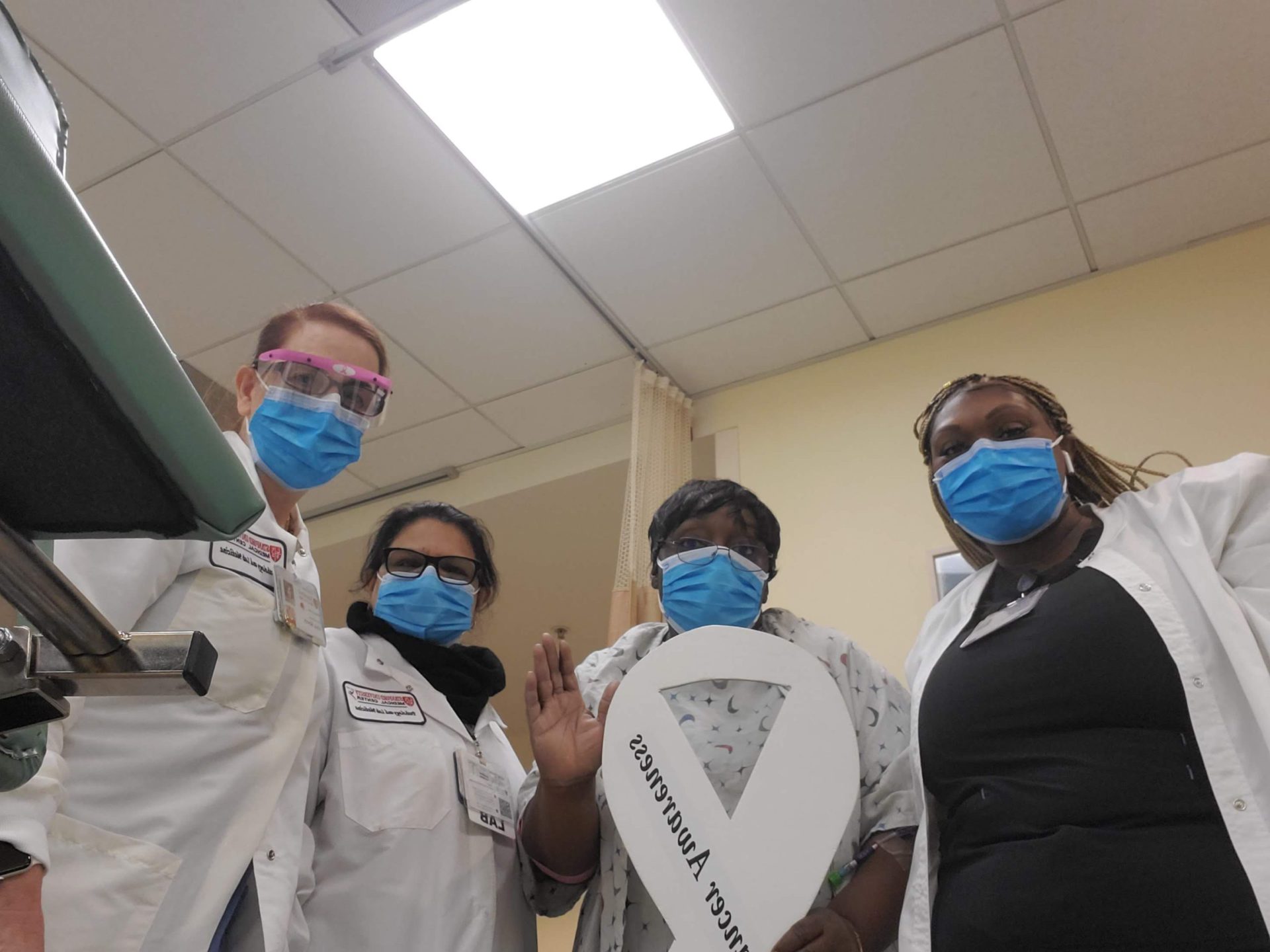

He was admitted bright and early the next morning. Here comes the nephrologist and her nurse practitioner. He looks even better from just that one dialysis session. Every single morning that we were in that hospital, the two of them showed up to say, “Here’s what’s going on.”

Imagine being in the hospital [for] a month. There were many doctors [and] many specialists. They would come in and give me, “Okay, he’s probably going to have a blank test today,” or “This is probably what’s going to happen.” It kept me [in the know].

My sorority sister gave me a binder that first week. She said, “Listen, it’s going to be a journey. Take this binder. Write everything down. When doctors come in, write down their names and who they are.” I did exactly what she told me. But things started to happen.

They would talk to me. “He needs this surgery.” His lesions were up and down his spine. He needed to have what’s called a kyphoplasty to shore up the spine to make it more stable. He was too sick to give consent so, of course, I had to do that.

We had the pulmonary doctor looking at him. We had a cardiologist looking at him. They finally confirmed the diagnosis and they started to treat him.

We thought he was getting better. [Then] his lungs started to bleed. It was a reaction to the treatment. Now I have pulmonary, cardiology, and hematology kind of pointing the finger at each other like, “What’s going on?” The hematologist was like, “It wasn’t what I did.” It was just all of that.

I sat in that hospital and with all of that going on, I could not leave. I slept in that hospital every single night, but two nights. I was afraid that if I left, a doctor was going to come in and tell him something else.

We knew nothing about multiple myeloma. It still didn’t make sense to me. All I knew was he was not getting better. Things are happening. I need somebody to please, please figure this out.

‘If it is that, here’s the deal. It is incurable, but it is treatable.’ I remember those words distinctly.

Diagnosis

Taking on the myeloma caregiver role

In the beginning, things were happening so fast that I couldn’t fall apart. I had to get the information. I didn’t cry when the doctor would tell me whatever. My crying took place at night when I’m on that couch in the hospital room [where] they made my bed.

He’s sleeping. I’m crying and praying. Prayer got me through. I would leave his room sometimes and sit out in the lobby area. I would call close friends. I have some close friends that are like sisters to me.

I called my own doctor, who’s a very close friend of mine. Doctors just tell you matter-of-factly and that’s how she did it. She was like, “Look, if it is that, here’s the deal. It is incurable, but it is treatable. It’s going to be rough in the beginning.” I remember those words distinctly.

I was having those kinds of conversations with my mom, with my sorority sisters, a friend from church, and my pastor was also dropping in. He would show up at the hospital [late] at night because he could always get in.

I was running on adrenaline. I was in survival mode and all I knew is what I had to do.

Getting help

My pastor was saying to me, “Marsha, you need to stop it. What are you doing? You are not Wonder Woman. You do so much for other people in our congregation. Let somebody help you. What do you need?”

I was exhausted by then. I had dropped 27 pounds or so in 4-5 weeks because I was running on adrenaline. I was in survival mode and all I knew is what I had to do. But it wasn’t good for me. That was how things were.

I knew that I needed to talk to somebody. I’m sitting in this hospital room. He can’t communicate with me. The kids weren’t in a position. I knew I had to reach out to my closest circle.

My village is amazing. What I got from them was talking. I would advise [you]: talk to somebody. Talk to somebody that you can trust, whomever that might be. Trust is a huge thing in our culture. We don’t always trust. That’s how I got through it.

I started to make notes to myself about the business [and] things that needed to be taken care of. That’s when the shift happened. Crying, sitting in that hospital, we had no idea how long we would be there. I knew that I had to take care of some things.

I’m a lawyer. I have been for 37 years. I also have a market research consulting business. I used to work at Procter & Gamble when I was in law school. Meanwhile, I’m sitting in a hospital room, thinking I have a mortgage to pay.

Financially, I had to make sure we were good. But I also knew that there were things like disability. At some point, the diagnosis came so I’m like, “I should probably check about disability.”

I had a fight with an insurance company that I won’t name because they started sending me letters saying you took him to this hospital and it is out of network. I’m like, “You must be kidding me. I don’t know if he’s going to walk out of here and you’re talking about out of network?” I won that fight because I took him to [the] ER and when you go to an ER, who cares about [the] network?

The doctors were cheering me on. I started establishing relationships with all of them. “Marsha, what’s going on today?” They were asking me about the business of it all. “Did you beat the insurance company yet?” “What about Medicare? What about Medicaid? What about disability?” That was the relationship and that was the environment in that room.

If I leave the hospital to come home to shower, to lay down for a minute, a nurse would have my phone number and would promise to call me if anything went down in that hospital room.

My pastor was saying to me, ‘Marsha, you need to stop it. What are you doing? You are not Wonder Woman. You do so much for other people in our congregation. Let somebody help you. What do you need?’

Reaction to the diagnosis as a myeloma care partner

I decided that I have to be part of this medical team.

As lesions were up and down his spine, it affected his entire body. He couldn’t even move his arms. He couldn’t lift them. [On] the hospital bed, he was more comfortable with pillows under each of his elbows. But I had to do the lifting. At times, the nurses wanted to, but they were not gentle enough for me so I did that.

That’s when advocacy started for me. When the doctors would come in, I would connect the dots for them because [there were] so many of them.

Talk to somebody that you can trust, whomever that might be. Trust is a huge thing in our culture. We don’t always trust.

Treatment

The doctors said to me, “We want to start treatment,” which they did, and that was the treatment he was allergic to. It was two shots that I remember that nurse coming in one shot one week, came back, and gave a shot the next week. Then his lungs started bleeding. They figured out that’s what it was.

I have to say that those two shots knocked much of those bad cells out tremendously. There’s always a good and a bad. I’m thankful because it knocked the M protein way down, but they had to stop it.

He had to stop all treatment for some months until his lungs got clear and they figured it out. But the doctor said, “Here’s what can happen. We need to treat him. It could be we’ll never give him that again, but it could be pills.” My big question was always: is it chemotherapy?

They were throwing around the word “immunotherapy” and they had to explain that to me. When they started treatment again, they did start him on a regimen of some of the therapies, the pills.

I had to be very careful with those. Those things were scary. When I came home, they were like, “Don’t touch them, and don’t let anybody who might be pregnant or would get pregnant in the future touch them.”

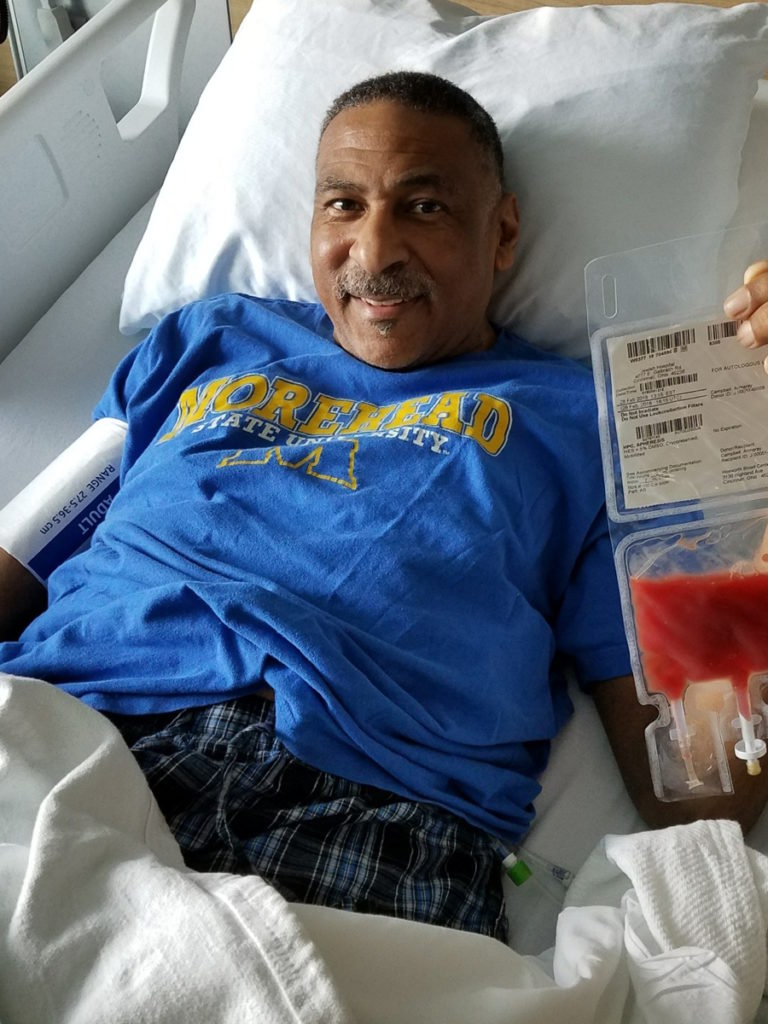

Pretty early, they started talking to us about a stem cell transplant. He was diagnosed [on] January 17. By March 18, he had a stem cell transplant.

Making medical decisions

The decision was pretty much mine. I share it with him as much as I could, but I didn’t want to burden him with anything. I needed him to concentrate on getting well.

I said, “Listen. He’s not going to worry about anything. He’s not going to worry about finances. He’s not going to worry about this treatment. I’ll tell him what he needs to know.”

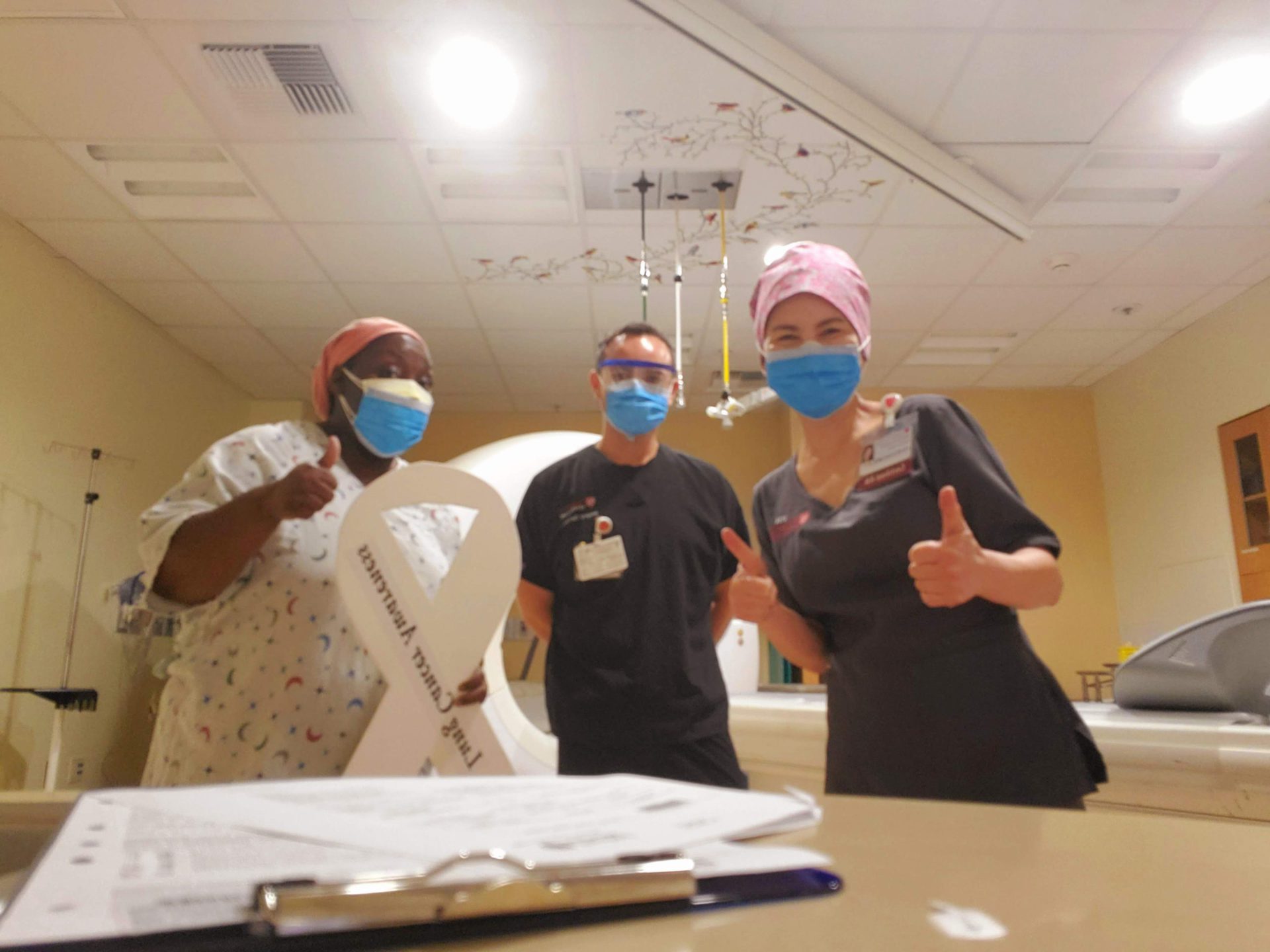

Role as care partner post-transplant

Love the team that we worked with. We met a lot beforehand.

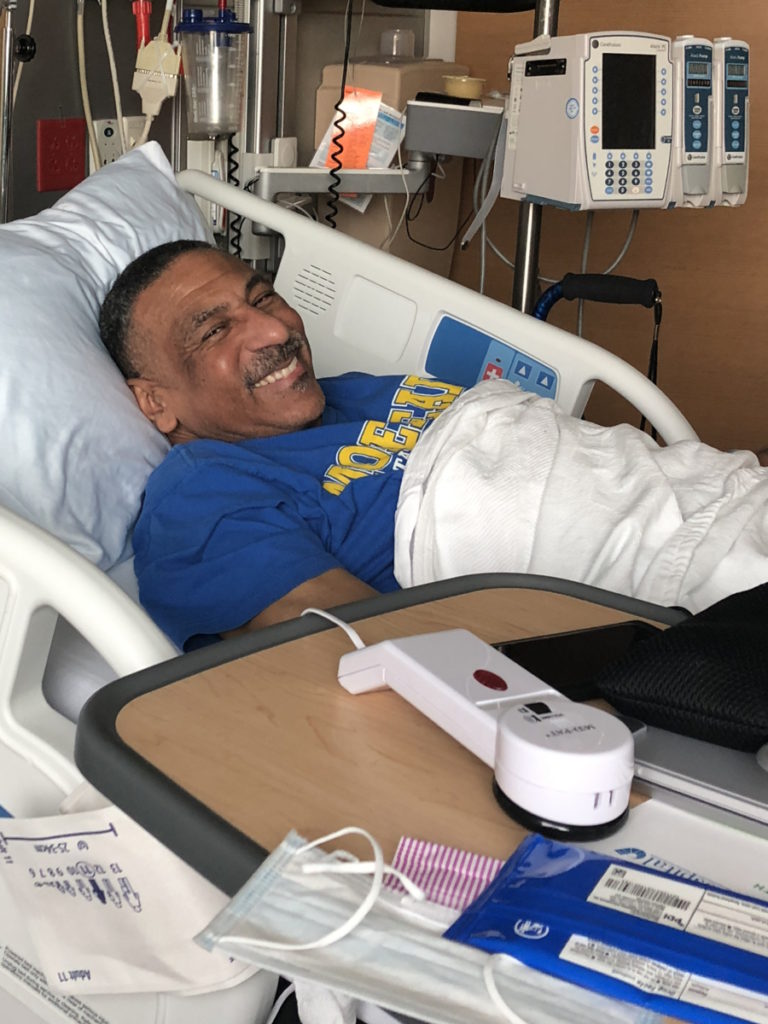

He stayed in a wheelchair for a while. He had to learn to walk all over again. But by the time [of] his transplant, he was walking again.

I would take him to the doctor and they explained exactly what was going to happen. “We have to collect those cells. We have to go in the hospital then we’re going to give him this heavy dose of chemo and all of his numbers are going to bottom out.”

That transplant was tough, but he did it. God brought him through that. It was hard. It happened exactly like they told us.

I will say I thank God for that transplant. Put him in complete response. There’s no spike detection, no protein detection. He gets a check every month.

Just a multitude of emotions. It’s a journey. It’s up and down. We’re hopeful.

That transplant was tough, but he did it. God brought him through that. It was hard.

Advocacy

What was the shift for you?

My husband started getting better. That was when it switched in my mind. You can be an advocate for other people because home is taken care of to a degree. Things have settled down. You need to give back.

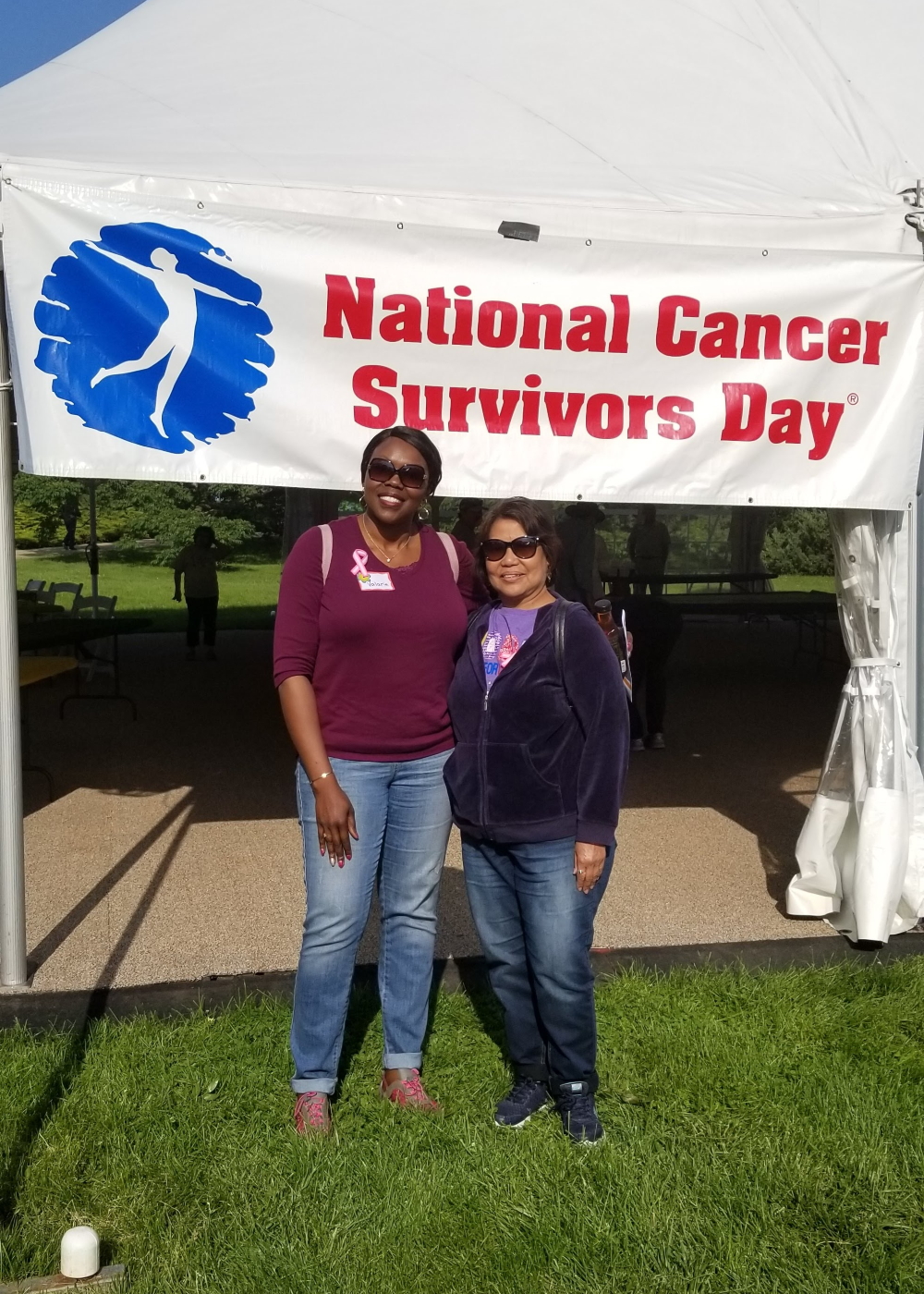

The advocacy that I do now is the “give back” part. I never want anyone to be caught off guard [by] multiple myeloma. I know there are a lot of other things out there to be caught off guard about, but for me, it’s multiple myeloma.

If you know what it is, know enough to ask your doctor what it is, that is what I’m trying to do. I share with people what it’s about.

Once you are taking care of someone with myeloma, be their advocate because it’s a journey. It can be challenging at times so they need somebody.

We are often diagnosed with low risk. However, we’re dying more.

Learning more about multiple myeloma

In the beginning, I didn’t want to know the details about the disease, let alone how it affects anybody. I just did not. At some point, I decided [I] need to know.

I happened across HealthTree and other organizations that had information about myeloma. What I learned was that Blacks are predisposed to the diagnosis two to three times more likely than Caucasians to be diagnosed with multiple myeloma.

Honestly, my reaction was, “Of course, we are, like other stuff, like everything else.” That was a turning point for me.

The other thing I learned was more men than women are usually diagnosed. I learned that African Americans are, on average, four to five years younger being diagnosed.

The thing that really got me was that African Americans quite often have lower-risk genetic myeloma. There are lots of kinds — low risk, high risk. We are often diagnosed with low risk. However, we’re dying more.

The doctors are saying you’re diagnosed with low risk, more likely, if — and that is the operative word, if — you can receive equitable treatment — the treatment that’s best for you, just like Caucasians would receive the treatment that’s best for them — your outcomes could be better.

Then we’re into the whole health equity, disparities, and inequities space. When I look for people to collaborate with, I’m looking for people in those spaces because those organizations and those people get it. If we could just get equitable treatment, we could have better outcomes.

Now I want to be clear. I want everyone to have great outcomes, but I also want African Americans to have outcomes that could be greater because we’re getting the same care or equitable care.

It goes back to awareness. We don’t know there’s such a thing so that’s where it starts.

I’m doing a campaign now. “Doctor, could this be multiple myeloma?” If I could teach everybody [that] if you’re not figuring out what the diagnosis is, you don’t know what’s wrong, [and] you have these symptoms, to say to your doc, “Doctor, could it be multiple myeloma?” Because then the testing could start.

The first thing is we just don’t know about it so we’re not aware of it. We’re not educated about it. But then even when you think about diagnosis, there [are] still these disparities.

Before a diagnosis, there are disparities because we’re not always taken seriously when we present our symptoms to a hospital, to a doctor, or to a nurse. Our complaints about what’s going on are sometimes minimized. We’re not heard. Testing is not being done proactively to figure out. That’s even before diagnosis.

Then after diagnosis, we have all these social determinants of health that are still there. We might live in an area where social socioeconomics [is] low. We might not live in an area where an academic cancer institution is. We may not have transportation to get to these academic centers. We may not know. We don’t get that influx of information. It can be all kinds of things.

Then when you talk about clinical trials for African Americans, I might not be in a financial situation [where] I can take off X number of weeks to travel to wherever to be in this trial. We might not have as simple as Internet in [our] homes.

Those are the things that I’ve learned. Myeloma is already a tough journey and now we have to add these kinds of inequities on top of it to try to get through myeloma.

I want everyone to have great outcomes, but I also want African Americans to have outcomes that could be greater because we’re getting the same care or equitable care.

Importance of testing

It’s huge. Those are difficult medical things. Some stuff still just kind of goes over my head and I’m just like, “Oh, I can’t even understand that.” But what I do know is: ask. Know enough. For instance, know the common signs and symptoms.

You get your blood work done. It could be high calcium, there could be renal dysfunction so your kidney numbers might not be right, you might be anemic, and you could have bone pain. Those are the big ones. The acronym for that is C.R.A.B.

Know enough about that that if you’re going through something, you ask your doctor. “Doctor, could it be multiple myeloma? Can you test me for it?” You don’t even have to know what the tests are.

Here’s one thing that happens in our community. Everybody Black is told that we’re anemic. At some point, all five of us in our house have been told that we’re anemic. And I heard one of the Black myeloma specialists say, “We’re not anemic just because we’re Black. We’re not anemic because we have this melanin in our skin.”

Push back on your doctor because it could be something very simple — you need to take iron pills — or it could be something very serious — like myeloma.

That’s what I say to people. You don’t have to be a doctor. You don’t have to know every single thing but ask questions, demand time to be heard, and push for testing.

I always say to people who are then diagnosed: have somebody go to appointments with you or somebody to be there for you [to] take notes because you can’t get everything. I automatically take notes because that’s what I do, but not everybody does that. You can even take notes on your phone. There has to be a level of self-advocacy in this space that will serve you well.

Myeloma is already a tough journey and now we have to add these kinds of inequities on top of it to try to get through myeloma.

Distrust of the medical system

There’s distrust for good reasons. When I think about my grandparents, that generation was like, “Absolutely not. You will not use me as a guinea pig.” Those were the words because there were situations where Blacks were not done right. We lost lives and it was just a terrible situation.

Those events are in history. We know what they are. It wasn’t even done in a manner that tried to make Blacks feel like we were trying to do the right thing. It just was not right.

Then when I look at my mom’s generation, she still has a lot of distrust. “I’m not sure what these doctors are doing.” You look at my generation, it’s carried down. It’s even carried down when I look at my kids.

Now, I think it’s getting better as we go down the chain. But it’s still very real.

You don’t have to know every single thing but ask questions, demand time to be heard, and push for testing.

Importance of having family conversations

[In] the Black community, we don’t always openly share. It’s not because we don’t want to help our families. I’m thinking about my generation. We were taught that what goes on in our household stays in this household. You will not go out of this household talking about what goes on.

When my husband got sick, my first go-to was we will not play this out [on] social media. Even my generation, that’s what I think about. That can be a concern in the Black community because we absolutely need to share, especially with our immediate families.

I just say to families: share as much as you’re comfortable with. Send this brochure out to your circle. It’s about myeloma. Just share that. You don’t have to share anything about [yourself], personally, but share the information.

Words of advice

This is the work that just brings me joy. I’ve never shared information with people. They thanked me and hugged me.

When I think about [my] career, I’ve talked to a lot of people. I run my businesses. I would have to share about my business. “Come to me. As a lawyer, I can do this for you. I can do that for you.”

Although I was helping people, it pales in comparison to [saying] to someone, “Have you ever heard of multiple myeloma?” “No. What is it?” And I tell them and they’re like, “Ooh. Is there a test? Can I get screened? What do I need to know about it?” That brings me joy that I feel like I’m impacting lives one at a time.

As I look at other people who are doing the same thing and other organizations who are doing the same thing, I’m like, “Yeah, this is the important work.”

I have to thank my family and my close circle. Especially, my family, I can’t do what I do without them. I’m still working my job. My consulting and practice are there for me when I need them. My close circle, that village, is always there.

Inspired by Marsha's story?

Share your story, too!

More Caregiver Stories

David Garrigues Ronda, Spouse of Laurent Gemenick, Bladder Cancer Patient

“Talk to family, talk to friends. Ask for help. Don't be alone. And above all, don’t miss any doctor's appointments.”

...

Lung Cancer Caregiver Series Episode 2: Stephen and Emily Huff's Candid Conversation

"We talked, and I remember saying, "What if we have kids and what if I die?" And you were like, "What if you live?"

...

Emily Huff, Spouse of Stephen, Lung Cancer Patient

“Emily's the reason why I’m alive today. The treatments have kept the cancer at bay, but she's the one who’s kept me living, breathing, and enjoying life.”

...

Blair D., Spouse of Brain Cancer Patient

“Find other people who are going through the same thing you are. This journey is very isolating and very lonely.”

...

Nat G., Spouse of Bladder Cancer Patient

“You have to become selfless as a caregiver. You have to assure that person that you are there for them.”

...

Kyle Appleford, Spouse of Lung Cancer Patient (Metastatic) with No History of Smoking

“Ask for help. Don’t be too prideful to accept the help. I wouldn’t be here without all the support from family and friends.”

...