Blood Work Basics: Making Sense of Your Test Results

What do your cancer blood test results really mean and how do they help doctors detect or monitor cancer?

Join hematopathologist Dr. Kamran Mirza and cancer advocate Stephanie Chuang to break down the most common diagnostic cancer blood tests, including the CBC (complete blood count) and the CMP (comprehensive metabolic panel). Learn how pathologists interpret results, what those ranges mean, and how small changes in your numbers can offer big insights into your health.

Find out more about:

Why doctors order cancer blood tests: What they’re looking for and how to prepare.

Making sense of the CBC: Understand what each number represents — and what it doesn’t.

How blood results guide treatment: From diagnosis to tracking remission or recurrence.

Whether or not you should be worried: When out-of-range numbers matter and when they don’t.

What’s next in the series: Learn how this session leads into condition-specific follow-ups for six different blood cancers.

We would like to thank Blood Cancer United for their partnership. They offer free resources, like their Information Specialists, who are one free call away for support in different areas of blood cancer.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make treatment decisions.

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

- Introduction

- What Does a Pathologist Do?

- Initial Testing Before a Diagnosis

- What is a Complete Blood Count (CBC) Test?

- What Happens if Your Blood Counts are Abnormal?

- CBC Tests for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients

- How Do You Process the CBC?

- What’s the Difference Between CLL and SLL?

- What are the Symptoms I Should Be Looking Out For?

- What Recurring Tests Will Patients Need to Have Done?

- Using Blood Work to Identify Minimal Residual Disease

- Why Would My Doctor Order a Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP)?

- How Doctors Decide Which Blood Tests You Need

- Conditions That are Monitored More with CMP Tests

- Should Patients Check Their Lab Results Online Before Talking to a Doctor?

- Dealing with Delays in Getting Test Results

- Conclusion

Introduction

Stephanie Chuang: Hi, everyone! Blood Work Basics is part one of a multi-episode program designed to empower you with the information you need for your next blood work appointment. While the other episodes will be about specific blood cancers, this episode is more focused on the initial tests that you may deal with as you try to get a diagnosis or following your initial treatment.

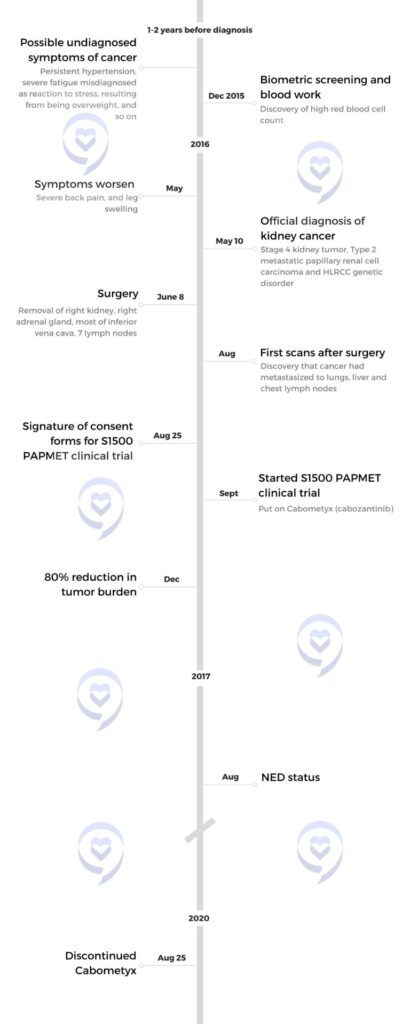

I’m the founder of The Patient Story. I have gone through a myriad of blood tests, poked and prodded constantly, when I was getting diagnosed, which ultimately would be a non-Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and all through treatment.

I remember having to wait to get my blood drawn. First, it was through my veins; then I got my PICC line and a port. They needed to make sure that my white blood cell counts were okay for me to be able to withstand the next round of chemotherapy. Each round of chemo lasted for about six days at the time, which was definitely not short or easy.

During that time, I started imagining what would eventually become The Patient Story. I felt so lost. There were so many things that I wanted to know the answers to, but I wanted to know them in a humanized way — don’t give me the medical jargon. That’s what The Patient Story focuses on.

We help curate humanized information to help you navigate life at and after diagnosis. We do this through in-depth patient stories, educational programs, and discussions to amplify the voices and concerns of patients and care partners.

I want to give a shout-out to our friends at The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. They have so many fantastic resources, including their Information Specialists, who can help talk about things like blood tests if you need.

While we hope that this discussion is helpful for you, keep in mind that this is not a substitute for medical advice, so please consult with your team about your decisions. Hopefully, you’ll have some questions from this discussion that you can ask.

I’m excited to introduce someone I now consider a friend whom I met as a patient advocate: Dr. Kamran Mirza, the Godfrey Stobbe Professor of Pathology Education, Professor of Hematopathology, and Assistant Chair for Education at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Mirza also shares medical insights online to help people like us, patients and care partners, understand the science of diagnosis. You may know him from social media as @kampathdoc. Dr. Mirza, welcome again. It’s so good to see you.

Dr. Kamran Mirza: It’s always a pleasure to see you. Thank you very much for having me, Stephanie.

What Does a Pathologist Do?

Stephanie: Dr. Mirza, before we kick off this discussion, we want to humanize the word pathology. A lot of patients, their families, and friends may not see a pathologist during their experience at the hospital or at a clinic. Can you break down what a pathologist does?

Dr. Mirza: I always say to my patients that the pathologist is the doctor you never see or usually don’t see 99% of the time. A pathologist is a physician. They work in the medical laboratory, where all of the human body tissues and fluids go for any type of diagnostic work.

Whenever your physician orders any kind of testing, which could be blood tests, urine tests, or other types of tests like biopsies, they always come to a physician behind the scenes who is a pathologist. The work we do is pathology.

Like other parts of medicine that you might all be aware of, pathology is also subspecialized. I’m a specialist in blood pathology. My diagnostic area is leukemia, lymphoma, anemia, etc. Similarly, I have colleagues in pathology who deal with disorders of the brain or disorders of the liver, etc. Every part of medicine has a pathologist associated with it. We are physicians who will provide the diagnosis, which is what your patient-facing provider uses in order to treat you.

Stephanie: Thank you. I know there are a lot of things that you do as a pathologist and I’ve learned a lot from that already.

Initial Testing Before a Diagnosis

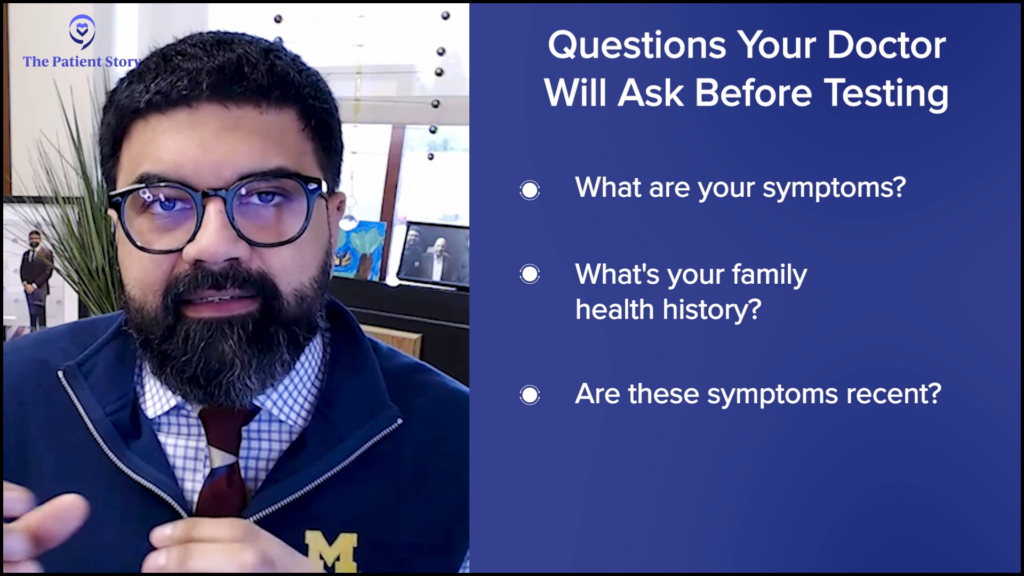

Stephanie: When we’re talking about blood cancer and the reason why pathologists are so focused on different blood tests at different times, could you give a generalized overview? If someone has a suspected diagnosis, what is the usual testing done at the very beginning, before people know exactly what they have?

Dr. Mirza: Whenever you present to a doctor, whether it’s a well visit or an urgent care visit, doctors are trying to piece together from your clinical history. They ask about how you’re feeling, how long you’ve been feeling this way, and your family’s health. They’re trying to ascertain whether these symptoms are short-term, long-term, from an ominous cause, or a more benign cause.

When you give a sample of blood, that is a snapshot of your internal health.

Once they’ve established in their mind what path they’re going down, they need to have some backing from diagnostic testing in order to clarify what it is. Typically, diagnostic tests include radiology, which is a visual imaging of the body. If they’re worried that there might be a mass lesion, they may send patients for X-rays or CT scans. The radiologists take a look at a particular part of the body and give you a report.

Similarly, the diagnostic laboratory is the pathology part. What we can provide you in the simplest way is a blood test. When you give a sample of blood, that is a snapshot of your internal health. Your blood can tell you so many things. Because we’re talking about blood cancers, it’s one of the simplest ways for your physician to find out if something is wrong in your blood or in the factory where all of the cells of the blood are made, which is the bone marrow.

All of us have bone marrow, which is the factory producing all of the cells. It’s inside our long bones, so it’s in the bones of our arms, our legs, and the pelvis. All of these bones are producing marrow, which is going to make all the cells in the blood.

A very simple way to figure out if the factory is working is to take a snapshot of the blood. In the blood, you have different types of cells. You can look at their numbers. Are they going up or down? There are a variety of other things that we can pick up from the blood as well. It can tell you things, whether it seems like an infection or cancer, or if everything seems okay.

All physicians need the next step of diagnostics to move things ahead. Whether it’s radiology or pathology, that’s where you will end up if you’re presenting symptoms to your physician.

Stephanie: Thank you for walking us through that. The stage we’re talking about is a period that’s very hard for people. It’s hard to wait because there are a lot of questions and uncertainty, and there’s no plan of action yet.

What is a Complete Blood Count (CBC) Test?

Stephanie: In the initial stage, one of the most commonly ordered tests is the CBC or complete blood count. I was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but I don’t know if any numbers were flagged in my CBC results. What is the CBC? What is it looking for? Can go down each blood cancer area and what the focus may be for pathologists?

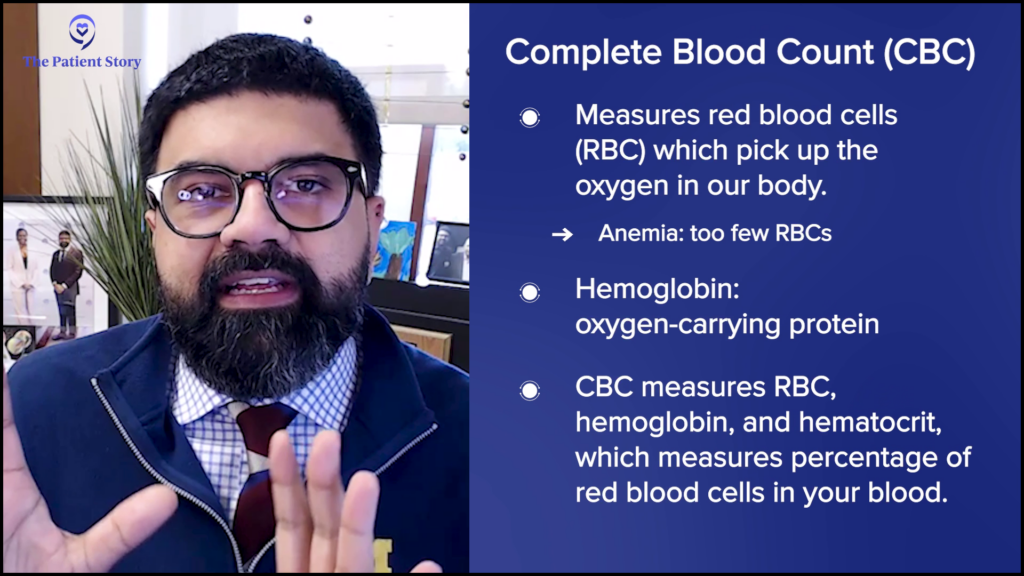

Dr. Mirza: The CBC is the complete blood count. There are three different aspects of the CBC that you can start thinking about, which go back to what the blood does.

Our blood carries oxygen. That oxygen is the oxygen we inhale into our lungs and the red blood cells in our lungs pick up all of that oxygen.

If you don’t have enough red blood cells, that might be anemia, for example. Associated with red blood cells is your level of hemoglobin, which is your oxygen-carrying protein. The RBC or the red blood cell count, the hemoglobin, and the hematocrit are used to look for your red blood cell component. Numbers going up or down may indicate that something is wrong with your red blood cells.

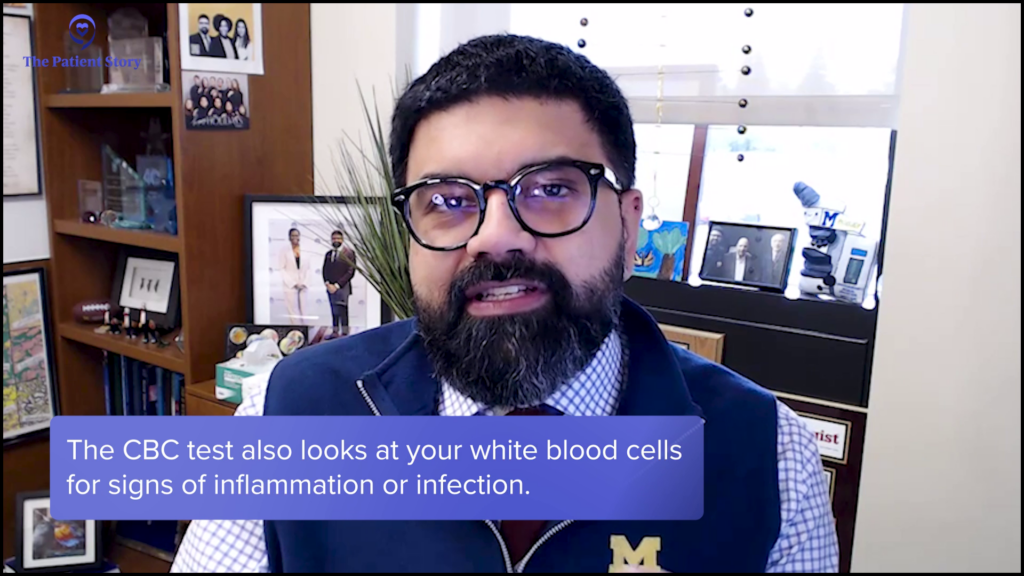

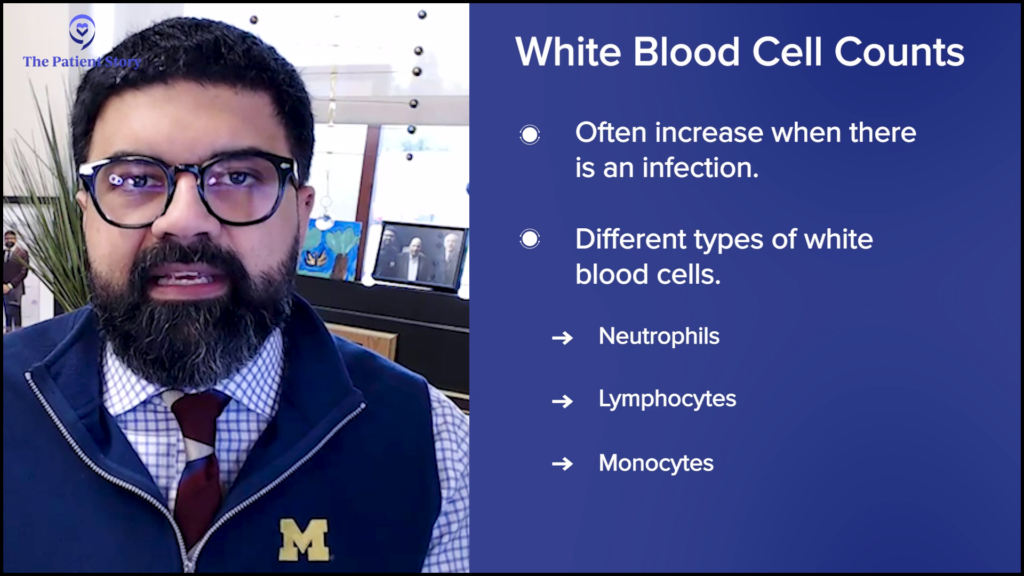

Another thing that your blood does is fight off infections, which are fought off by a variety of cells known as your white blood cells. You have different types of white blood cells. Your white blood cell count is an indicator of inflammation, infection, and a variety of things. The numbers going up or down can also indicate what may be happening to you as a patient.

The last number that you look for is the platelet count. Platelets are tiny fragments of cells that are floating around. Typically, these are in high numbers. Platelets help you clot or stop bleeding anytime bleeding occurs. For example, when a person who has a normal, healthy bone marrow has a small cut on a finger, that cut clots pretty quickly because the platelets are doing their job and the bleeding will stop. Similarly, you could have internal bleeding and not even know, but normal platelet counts and normal platelet function take care of all of that for you.

The CBC has a variety of numbers on it, but primarily, it’s looking for these three aspects of your bone marrow that produce cells and come out into the blood. It’s a snapshot of how those three things are performing.

What Happens if Your Blood Counts are Abnormal?

Stephanie: I love that you put it into these buckets for people to understand: red blood cell count, white blood cell count, and platelet count, and their different functions. This is not about any specific case but a generalized conversation. As a pathologist, can we go into each area? Let’s say there is an abnormal red blood count, white blood count, or platelet count. What might that generally indicate? How would you suggest further testing, or what are the next steps for the patient?

Dr. Mirza: If white blood cell counts go up, typically the most common reason will be an infection. This can be either a viral infection or a bacterial infection. When you look at the white blood cell count, it may also be associated with a differential count.

Typically, if a patient has a bacterial infection, neutrophils go up. If they have a viral infection, lymphocytes may go up.

A white blood cell count gives you the total number of cells, but that number won’t tell you what the cells are, so we need to figure them out. Either machines or human beings, who are medical laboratory professionals, look at the blood and then count how many different types of white blood cells there are.

There are different types of cells: neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes. These are the words that you would potentially be coming across if you see a differential count. Depending on what is going up, you may have an idea of what it might be. Typically, if a patient has a bacterial infection, neutrophils go up. If they have a viral infection, lymphocytes may go up.

But then, abnormal cells might start showing up in the blood as well and the differential count might flag abnormal cells. These are what we typically call immature cells and by immature, we mean that they came out of the bone marrow too soon. They needed to cook in the bone marrow a little bit longer, but they didn’t and came out.

Now, having immature cells come out can also be part of an infection. It can be normally seen in an infection, but depending on how the patient is presenting, it could be something more ominous or even be part of leukemia, which is a cancer of the blood.

If the blood cancer is just presenting in the lymph nodes… chances are that the blood may not show anything abnormal.

You mentioned before that patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma sometimes may not have any abnormalities in the blood and that’s absolutely true, like what you experienced. If the blood cancer is just presenting in the lymph nodes, which are all over the body, and you can feel them as masses, then chances are that the blood may not show anything abnormal and you need to take a look at the lymph node in order to diagnose what the lymphoma is.

However, there are other times when lymphoma can be floating around in the blood as well. There are many lymphomas that float around in the blood. They will be picked up in the white blood cell count and differential count as an increase in the number of lymphocytes because lymphocytes are the cells that constitute the blood cancer lymphoma.

Normal lymphocytes in all of us are floating around and they’ll be within a normal number. But if they go up, it can either be because of a viral infection, or if they’re really, really high, it could also be because of a lymphoma that’s floating around. It’s very context-dependent. These are just numbers. You have to put your story and your history. Every patient will have their own presentation. What we do as pathologists, as your physicians, is put all of that together in order to give a diagnosis.

With red blood cells, often the problem is a decrease in red blood cells. This could be either because of simple things, like a patient not having enough iron in their diet. If they don’t have enough iron, they may not make enough hemoglobin and then their red blood cell count goes down because they have anemia.

Anemia is a decrease in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. This could be in patients who have been in an accident and lost blood, which can lead to anemia. The red blood cell count goes down because you’ve lost so much blood. It could also be because of nutrition or something more ominous, like a blood cancer. A blood cancer taking over your bone marrow could decrease the number of red blood cells that are being produced and also show up as an anemia.

Context makes a huge difference. If a patient is known to be nutritionally deprived or if it’s a female patient who has very heavy menstrual periods or losing blood regularly, that anemia will most likely be because of iron deficiency. But if there is no history of blood loss, the patient has been doing well nutritionally, and they’re still anemic, then you start worrying why there is anemia. Normally, patients should not be having anemia.

Lastly, platelet counts can go up or down. Usually, what happens is that the platelet count goes down, which will hinder the ability of the patient to clot properly. For example, a cut happens and they keep bleeding when it should have stopped, or they may have bruises. Under the skin, they see splotches of bruising, even with the smallest amount of trauma and that could indicate that their platelet count is low.

In all of these three cell types, things can go up or down and all of that could be part of a reactive process, which could be benign, or it could be part of a more ominous process, which could be malignant. Again, it all depends on how the presentation has come to the physician and a variety of things that the physician will likely ask you before coming to a conclusion and ordering a test.

Stephanie: Thank you. Even after all these years of advocacy, it was helpful to have them spelled out and learn what they all mean. What I’m hearing is there are signs and signals of your internal health by the CBC, but also, context is important. What you and other healthcare team members are doing is putting together the entire story.

CBC Tests for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients

Stephanie: Our audience comes from across a lot of different blood cancers, primarily non-Hodgkin lymphoma. We have aggressive and slow-growing Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic leukemia, acute leukemia, multiple myeloma, and myeloproliferative neoplasms. CBC is a very basic test start off with. With non-Hodgkin lymphoma, is it the same with aggressive versus indolent? What are you looking for in the CBC that might be a flag?

Dr. Mirza: Let’s talk about lymphoma in general. I’m sure patients like you are familiar with the fact that we divide them into Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin.

An increase in the number of lymphocytes by itself does not make it lymphoma.

Hodgkin lymphoma by itself typically does not show up in the blood. It will show up usually as masses or lymph nodes that you can palpate, which can be all over the body.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can also present with no abnormalities in the blood and just show up as masses or lymph node enlargement in different areas. When it does show up in the blood, that is what we call lymphoma in the blood or lymphoma in a leukemic phase.

Leukemia means there are white blood cells in the blood. Leukemia is a historic term. When people look at blood, they see red because red blood cells have a pigment. Next to them, they saw clear, colorless cells, which looked like they were white. White blood cells are not white at all. It’s just the contrast that they’re not red.

When you see white blood cell counts go up in a lymphoma, which is a non-Hodgkin lymphoma, what we’re typically looking for is an increase in the number of lymphocytes. An increase in the number of lymphocytes by itself does not make it lymphoma. You need to make sure that the lymphocytes that are increased are, for lack of a better term, malignant. They’re all being driven by a genetic problem that is causing a proliferation of lymphocytes that’s not normal. Abnormal lymphocytes are being created and propagated and continue to propagate.

If you are a patient with a lymphoma that did present in the blood, an example of which is chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Often, CLL is a disease seen in middle-aged to elderly patients. They might feel well, go to their PCP, and get a CBC done, which then shows that their lymphocytes are increased. Then they might do some additional testing, which will confirm that this is part of a lymphoma process. Typically, one of the tests that they do is called a flow cytometry test, a test that confirms that these lymphocytes are lymphoma cells that are floating around.

If we talk about non-Hodgkin lymphomas, you will see an increase in the number of abnormal lymphocytes floating around in the blood. The CBC will only give you the number. You will need extra testing in order to confirm that it’s a non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

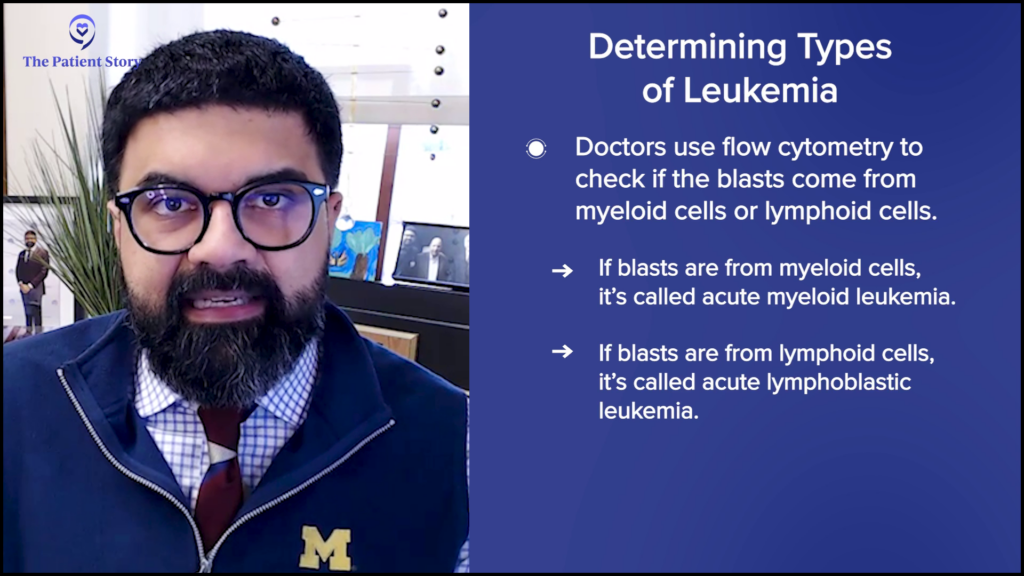

Now leukemia can be of multiple types. You can have a myeloid leukemia or a lymphoid leukemia. This all goes back to the bone marrow, which produces all types of cells, including lymphocytes and other types of cells. If a patient has an acute leukemia, then that primarily means that their blood has a very high number of very immature cells.

If we see patients who have lots of blasts in the blood, then we immediately think of an acute leukemia.

What’s happening is that the most immature cell from the bone marrow is not undergoing any differentiation or growing up that it normally does and it’s coming out directly into the bone marrow. These immature cells are called blasts. If we see patients who have lots of blasts in the blood, then we immediately think of an acute leukemia. Very different from non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which are mature lymphocytes but are abnormal and proliferating. Acute leukemia is when blasts are coming out and are very immature.

Flow cytometry studies would be done to figure out whether those blasts are from the myeloid line or the lymphoid line. If they’re from the myeloid line, it’ll become an acute myeloid leukemia and if they’re from the lymphoid line, it becomes an acute lymphoblastic leukemia. But in general, the blood will show you very high numbers of immature cells or blasts.

When a patient looks at the CBC, the WBC count will be increased, but by itself, that doesn’t mean anything. Then you look at the differential count, where they will have counted the number of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes. There’ll be another one there that will be labeled “other” or “blasts,” and that will be increased. That’s how we will be able to tell the PCP that your patient likely has an acute leukemia.

The bone marrow is throwing out lots and lots of a particular type of cell. Depending on what that type of cell is, we can look at that and figure out what the disease entity is.

With a myeloproliferative neoplasm, it’s when the bone marrow is producing a lot of cells in the myeloid lineage, but they are not blasts. It’s not an acute leukemia, but there can be a high number of red blood cells, which we know as polycythemia vera, or there can be a very high number of platelets, which is known as essential thrombocythemia.

There are different types of myeloproliferative neoplasms. What’s happening there is that the bone marrow is throwing out lots and lots of a particular type of cell. Depending on what that type of cell is, we can look at that and figure out what the disease entity is. Often, patients will need to undergo bone marrow biopsies for that.

You also mentioned myeloma or plasma cell diseases. Plasma cell diseases usually are diagnosed by a bunch of blood tests that look at the number of proteins in the blood, but you also need to have a bone marrow examination. There are times when we can look at the blood and see slightly increased numbers of plasma cells, which are the abnormal cells for myeloma. But again, you have to put into context a bunch of things for myeloma.

You have to take into account any radiological lesions the patient may have. Typically, these patients have lytic lesions in their bones. You also have to take into account their kidney function, how much protein they have in their blood or urine, and how many plasma cells are in the bone marrow. You have to put all of that together to make a diagnosis of myeloma.

The blood and the numbers in the blood going up and down can start pointing us towards what could be happening within the blood cancer world.

To characterize the blasts, you need to study where the cells are coming from and what makes up that cell.

How Do You Process the CBC?

Stephanie: When you talked about the acute leukemias and the blasts, you said that you’re looking at different numbers as you do with all of these. But after the CBC, to confirm for AML or ALL, what is typically the next step in terms of testing? Is there one go-to?

Dr. Mirza: Yes, absolutely. When the blood is drawn, the phlebotomist takes the blood and brings it to the laboratory. The laboratory will immediately run the numbers. When the numbers are off, the machine starts flagging the sample as abnormal.

A medical laboratory professional, another hidden hero in the diagnostic journey, will make a blood smear quickly and start looking at the cells. If abnormal cells are there, we’ll be paged as a pathologist. I will look at it and confirm whether there are abnormal cells.

Typically, in high-resource settings like in the United States, the tests that are done are tests that will characterize the blasts. To characterize the blasts, you need to study where the cells are coming from and what makes up that cell. Is it a myeloid cell or a lymphoid cell?

The DNA of the cell might have some abnormalities that either gives a good prognosis or a bad prognosis.

The first test would probably be a flow cytometry analysis. Imagine if you’re going to a party and you don’t know who anyone is and everyone is wearing name tags. The name tag tells you who you are, where you’re coming from, etc. My tag says I’m Kamran and I’m from Pakistan.

Similarly, blasts have tags on them that can be studied by flow cytometry analysis. What flow cytometry analysis does is it shines a light on all of these cells and identifies what tags these cells are wearing.

When the tags are saying myeloid, we can say acute myeloid leukemia. When their tags are saying lymphoid, we can say acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Flow cytometry analysis is a study of the tags. In high resource settings, we don’t stop there because that’s important from a diagnostics perspective, but we also go forward and help the hematologist-oncologist by giving a prognosis.

Often, prognosis is associated with what is inside the genes of the cell. The DNA of the cell might have some abnormalities that either gives a good prognosis or a bad prognosis. We know, over decades of looking at this, that there are some leukemias that have a better prognosis and some that have a worse prognosis, and usually that stems from DNA. You have to figure out either mutations or looking at chromosomes.

If you are in the United States and you went to a tertiary care center and got a diagnosis of leukemia, you’ll often find a karyotype report, which are your chromosomes. Every human cell has pairs of chromosomes and those will be studied. The DNA in those cells will also be studied.

You’ll get a report with mutations, potentially a report of how chromosomes were affected, and that will all come together in your final pathology report. It won’t just be acute myeloid leukemia; it will be acute myeloid leukemia with translocation 821 or something. It will be a long report that can be very confusing.

It’s telling the hematologist that not only is it leukemia, it’s an acute leukemia, it’s an acute myeloid leukemia, and it’s an acute myeloid leukemia with a particular translocation. All of that will be put together and then that will help guide the hematologist in the treatment, if that makes sense.

What’s the Difference Between CLL and SLL?

Stephanie: You started talking about non-Hodgkin lymphoma and then went into CLL. I know that when we talk about CLL, there’s also SLL. Usually we hear CLL more often, but is there anything that you want to add as to how you look at things on the pathology side?

Dr. Mirza: CLL/SLL is actually one disease entity. You’re absolutely right. CLL is chronic lymphocytic leukemia and SLL is small lymphocytic lymphoma.

What happens is that in this particular disease state, the blood is full of lymphoma cells but lymph nodes are involved as well. When it’s just presenting in the lymph nodes, it’s called small lymphocytic lymphoma. If it’s just presenting in the blood, it’s called chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but it’s the same disease. Often, we’ll call it CLL/SLL. It’s the same disease; it just depends on where you’re picking it up on.

Because the blood is a very easy tap — all you need to do is find a vein and get a little bit of blood out — it’s much easier than doing a lymph node biopsy. Often, it will be diagnosed in the blood. But if a radiologist does a scan and sees a bunch of lymph nodes everywhere, most likely it’s part of the same process. In our classification schemes, it’s all lumped under one: CLL/SLL.

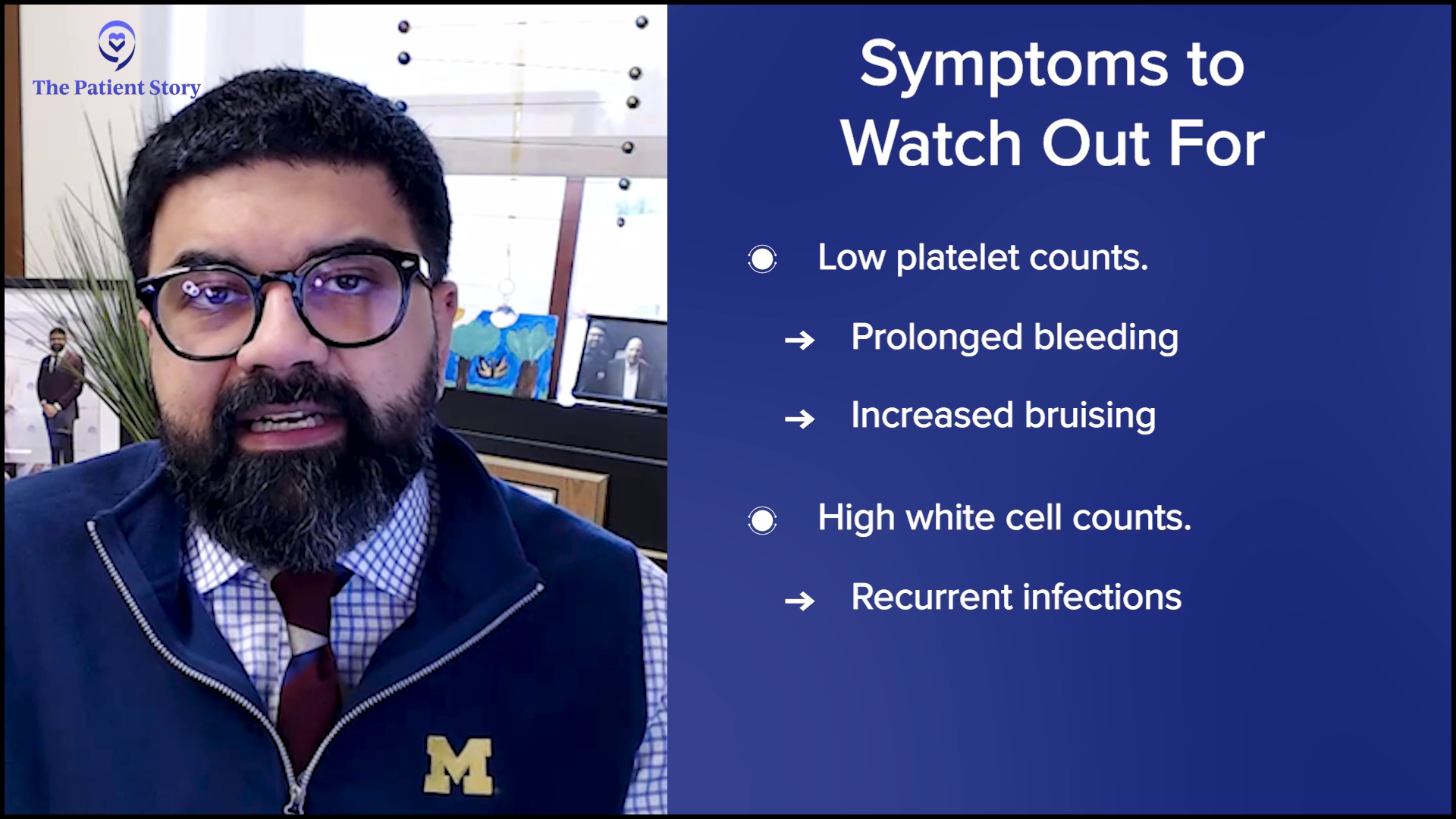

What are the Symptoms I Should Be Looking Out For?

Stephanie: You’ve done a great job laying out some of these signals. We’re talking very generally and in a vacuum, but you’re looking at signals that other people are providing individually. On that note, people might think how they can start to match some of this for themselves.

You talked about anemia, which is something that people are more likely to be familiar with. But what about some of these larger symptoms of things that might be wrong? Could you translate how they might manifest in the body? Could you laundry list and go through the major symptoms, starting with anemia?

When the numbers are off, then their functions are also off. If the function is off, then typically the three buckets are infection, tiredness or breathlessness, and bruising.

Dr. Mirza: Anemia reduces our ability to carry oxygen in the blood. Think about what we need oxygen for. We need oxygen for energy. We burn oxygen for energy, so patients will be tired and feel fatigued. They might be out of breath because they’re trying to breathe in more oxygen because they can’t carry it.

They might look pale. When you look at your hands and you press and get redness, that’s because of the hemoglobin. Under the eyes where you can see redness might be pale. If patients are pale, tired, are out of breath or have increased breathing, those might all be because of an underlying anemia.

For platelets, when they are decreased, you might see prolonged bleeding or bruising. They might accidentally hit their arm against the door and all of a sudden, they have a huge bruise. That’s probably because the platelet count is low.

With white blood cells, because what they’re primarily doing is fighting infections, the patient may present with recurrent infections if the white blood cell count is low.

All of these, when the numbers are off, then their functions are also off. If the function is off, then typically the three buckets are infection, tiredness or breathlessness, and bruising. Those will be the three that relate to the function of the three main types of cells.

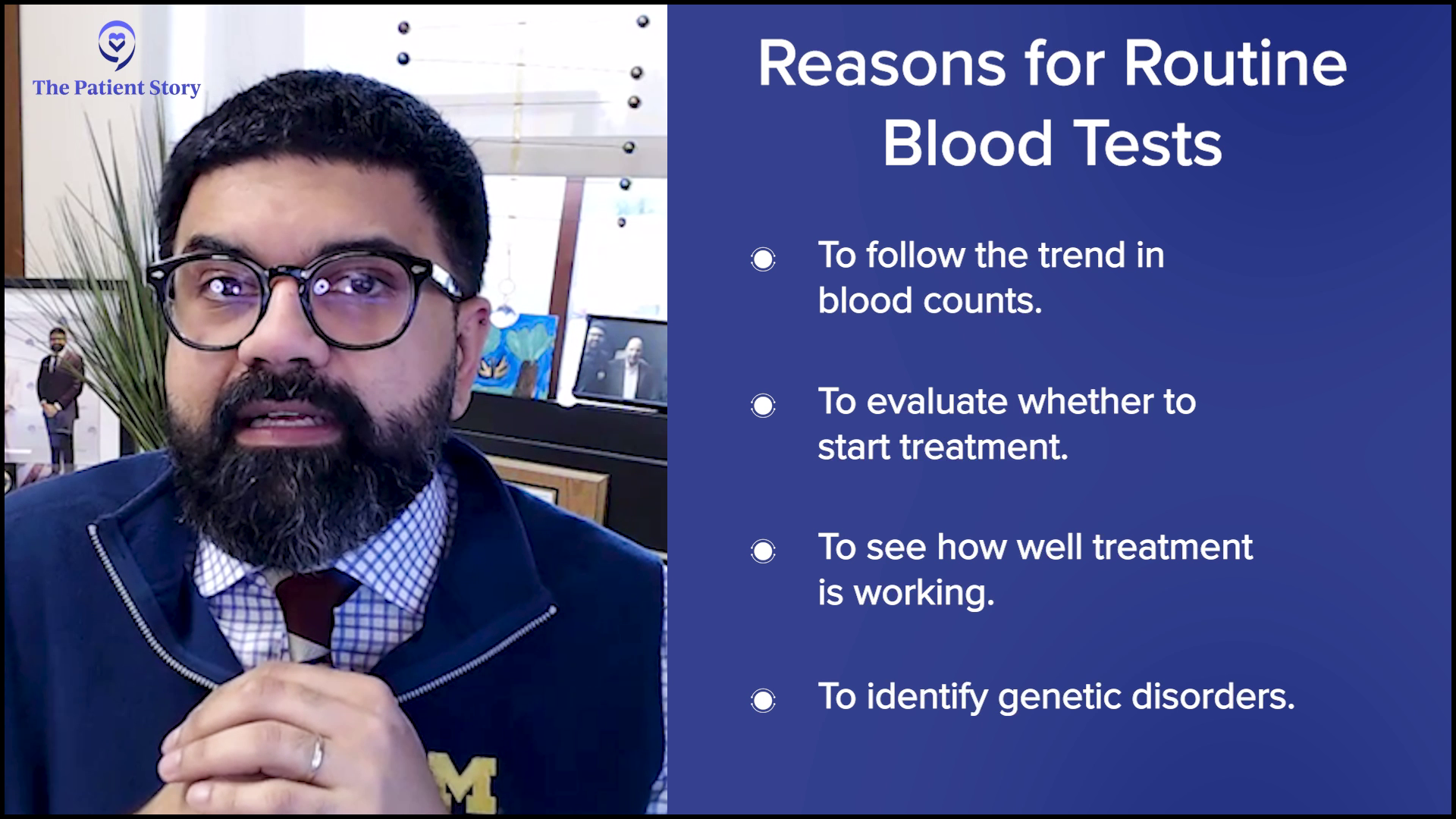

What Recurring Tests Will Patients Need to Have Done?

Stephanie: Shifting over to chronic blood cancers, what are the typical recurring tests that patients will likely be undergoing? Also, could you give a little bit more detail of why that’s what they’re looking at?

Dr. Mirza: What your physician wants to know is real-time updates, especially if you have an indolent disease, which means it’s either slow growing or not giving you that many symptoms. For example, there might be situations where if a patient has CLL, they don’t treat it because the number is low, not giving them any symptoms, and was identified by chance. They may give a drug that decreases the number of lymphoma cells, which isn’t heavy chemotherapy.

Ultimately, what we want to do is monitor how the cell numbers look over time. Repeating your CBC may be a very common thing for your physician so that they can keep check to make sure that everything is stable. It isn’t as much about one value; it’s about trending over time.

Take a patient who has CLL. When they presented, the only abnormality was an increased WBC count. There were lymphocytes but no anemia and no thrombocytopenia, which means that the red cells and the platelets were good. They chose no therapy or very minimal therapy and the patient’s fine.

But then when they present the next time, you see that there’s anemia associated. There was no anemia before and there is anemia now. Could this be because the lymphoma is getting worse and it’s disrupting the red blood cells? Or is it all OK? Is their platelet count OK, etc.?

Routine testing can take a variety of shapes accordingly.

I would think of them as real-time updates. You need to figure out whether things are progressing, staying the same, or improving. It could be that the lymphocyte count is totally normal. They got a drug and it took care of many, if not all, of the lymphoma cells. Even though it didn’t cure it, the number is so low that now it’s barely abnormal. It’s more a matter of follow-up.

In some cases, the disorder might be identified genetically. For example, chronic myeloid leukemia has a particular type of mutation or rearrangement in our chromosomes that can be detected by molecular testing. The patient is treated with therapy and can go into remission. All they need is that molecular test to tell the hematologist whether they are in remission or still have the disease.

It depends on what the disease is, how it presented, and what types of tests we have available for it, but routine testing can take a variety of shapes accordingly.

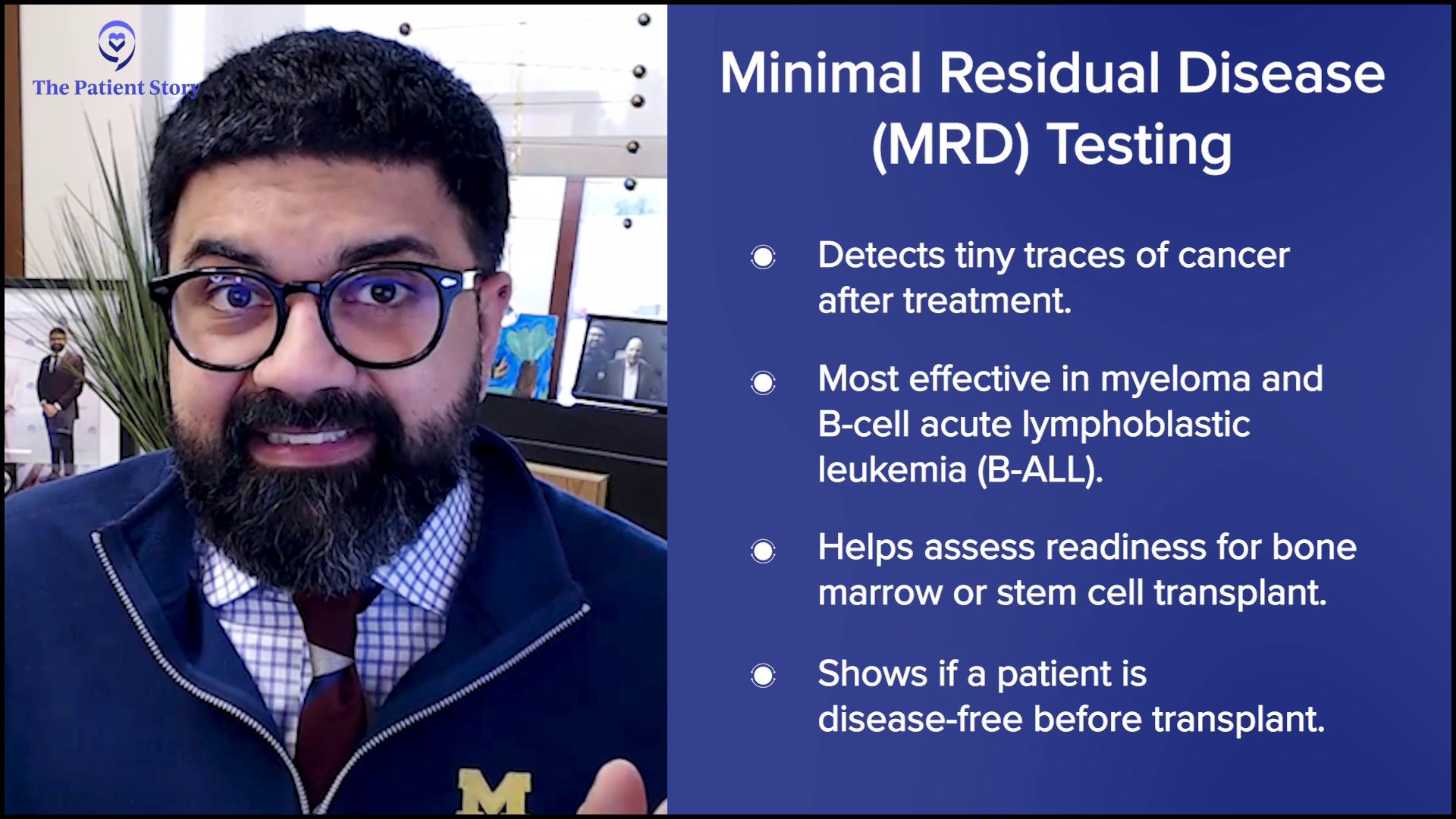

Using Blood Work to Identify Minimal Residual Disease

Stephanie: I don’t want to get too in the weeds, but there’s more and more conversation in the last few years about getting more precise with detection of disease. I don’t know if there’s anything you could talk about with minimal residual disease and in what areas people might be more part of the conversation than others.

Dr. Mirza: That’s excellent. You are so deeply thoughtful; it’s amazing.

Minimal residual disease is our ability to take a look at a very tiny amount of residual disease left after treatment. Our detection methods have become so good that we can potentially detect that.

We want to know before a transplant if the patient free of disease or if the patient has minimal residual disease left.

When we think about minimal residual disease, the two types of diseases that come early to mind are myeloma and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. We have good mechanisms to figure out if there’s a very tiny amount of disease left. We’re talking about one cell in 10,000 cells.

It’s harder for minimal residual disease studies to be done in acute myeloid leukemia and there are a variety of reasons for it. We can do MRD testing in AML, but it’s harder.

Minimal residual disease can be very helpful in a variety of ways. For some blood cancers, the curative treatment is a bone marrow transplant or hematopoietic stem cell transplant. We want to know before a transplant if the patient free of disease or if the patient has minimal residual disease left. It’s an indicator of their disease status before they go for a transplant.

Minimal residual disease testing can be by PCR or molecular testing, or by flow cytometry testing, depending on what the disease is. There are a variety of tests.

Precision-based therapies target a particular molecular alteration in the disease. We talked about CML. The molecular problem in chronic myeloid leukemia has a drug that you can treat with, but if that problem doesn’t exist, the drug is not going to work.

Patients get cured of CML by using this drug. It’s miraculous. There will be certain mutations that have specific drug targets. There will be certain chromosomal rearrangements that have targets. All of those are important when it comes to longer-term monitoring of testing.

Why Would My Doctor Order a Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP)?

Stephanie: We focused a lot on the CBC. What role does the comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) play? Those are generally the two tests that patients probably see the most or have ordered the most.

Dr. Mirza: The comprehensive metabolic panel, like the name suggests, looks at the metabolic status of the body. The CBC is looking at the numbers and the differential will look at the types of cells, etc. But the CMP is going to give you a better understanding of the patient’s kidney function, liver function, and electrolytes.

All of this balance is effectively given to us as a snapshot in the CMP.

Electrolyte imbalances are not going to be picked up by the CBC. Blood sugar levels are not picked up by the CBC. When you think of metabolism in the body, you’re trying to figure out how the body is managing the different byproducts of what we eat.

The way we do that is by controlling blood sugar and keeping electrolytes balanced, and those are due to liver function. The liver is a huge player in the metabolism of what we eat. The kidneys are a huge player in what we excrete in the urine. All of this balance is effectively given to us as a snapshot in the CMP.

How Doctors Decide Which Blood Tests You Need

Stephanie: In the blood cancer space, is CMP a complementary test always given or not necessarily? And in what case is it a must?

Dr. Mirza: If it’s an initial diagnosis and we’re still trying to figure out what’s happening to the patient, I don’t know if it’s a must, but I definitely would order it. I would want to know. Indirectly, it can tell you a variety of things that are happening with different organ systems. It’s reassuring if it’s normal. But it depends on how the patient is presenting.

These are reasonable tests because what they provide you versus the cost is a good cost to benefit ratio.

The patient can have concurrent diabetes and the CBC isn’t going to pick that up. Patients can have CLL and diabetes, but the CBC is not going to pick up the diabetes component. Because CMP is a snapshot of overall health, it’s helpful. Would you need to do it every single time if everything else was normal? Unlikely.

I don’t want to be flippant about it, but in the context of how expensive health care is, the CBC and the CMP are relatively cheap tests. I don’t know the cost, but they’re not very expensive. We’re not talking about thousands of dollars or even hundreds of dollars. The hemoglobin by itself is a very cheap test. These are reasonable tests because what they provide you versus the cost is a good cost to benefit ratio.

Conditions That are Monitored More with CMP Tests

Stephanie: For blood cancers, is there something where the CMP is more frequently utilized as a complementary test?

Dr. Mirza: Myeloma is a disease where the cancer cell is the plasma cell and the job of a plasma cell is to make proteins. It makes antibodies to fight off infections, but in myeloma, it’s all abnormal. You will need more than the CBC to figure out how much protein there is. That could be a urine test, but it could also be a blood test.

What you find is that in the blood, the normal protein ratio is all out of whack because you have all these abnormal proteins, so you’ll get another test to figure out what type of protein it is. But again, you can think of the CMP as a screening tool, a first test that will give you a big picture and then you can do a more specific test.

Both the CBC and the CMP in that sense are quick screens. For example, when you get a CBC and the lymphocyte number is up, you need a flow cytometry to figure out what’s happening. Flow cytometry is more expensive. You don’t want to do that for every single person. Similarly, the CMP can guide you and say the liver function is off, so you may want to do a whole other panel of liver function tests, which you don’t want to do upfront.

Should Patients Check Their Lab Results Online Before Talking to a Doctor?

Stephanie: We’re in the age where many patients get the test result notifications even before they hear from the doctor. Would you recommend that patients take a look at their results online or that they wait? How should they interpret these different values over time?

Dr. Mirza: I’m not hesitating because I don’t know the answer. It’s very nuanced and very patient-specific. It also depends on your level of health literacy in general and your personality.

Some people like to go to the airport early. Some people like to go to the airport late. Some people think knowledge is power, but some people think knowledge is not power and they get stressed out about it.

By law, tests and diagnoses that we write are immediately transferred to the patient portal. There are some scenarios where there is a small pause of a couple of days for whatever reason, like if we feel that the patient may not understand it, giving the physician an opportunity to look at it.

The patient has the full right to know what is happening to them. But it’s tricky to think about how that process unfolds.

Let’s say it’s a Friday evening and the patient went to the clinic and had their blood drawn. I look at the blood, do the flow cytometry, and conclude that they have acute myeloid leukemia. I write acute myeloid leukemia and sign it out. Meanwhile, the patient’s physician is still seeing patients in the clinic, but by the time the patient gets home, they’ll get a result on their patient portal, which says they have acute myeloid leukemia.

Think about this patient. Do they want to know this diagnosis? Do they understand what this diagnosis is? What will happen is that their physician who is going to treat them hasn’t had a chance to talk to them about any of this yet.

But that said, all of the information that we provide in reports is the patient’s material. We’re not gatekeeping anything. The patient has the full right to know what is happening to them. But it’s tricky to think about how that process unfolds.

There needs to be a conversation with your patient-facing provider to make sure that you understand the details of the information that can be bombarded to you.

Now, you can have a patient who is very up in their health literacy, understands exactly what all these things mean, can manage the stress or anxiety associated with this information, and can manage looking online where all sorts of opinions will be there. You need to have trust in your provider. There are so many nuances here.

Ultimately, though, it’s not our information to gatekeep. It is the patient’s information. Broadly speaking, it is correct that the patient gets access to that information, but there needs to be a conversation with your patient-facing provider to make sure that you understand the details of the information that can be bombarded to you.

Remember that even if it’s monitoring of tests, there might be variations of fluctuations. If I look at them, I can say that it’s a tiny fluctuation and no big deal, but the patient might think the worst.

Within the world of testing, what’s complicated is that in certain situations, certain tests being a little bit flagged is not such a big deal. With hemoglobin, for example, if it’s off by one point or half a point, it may not be such a big deal, especially if it’s in the normal range. But if it’s a creatinine value and it’s off by 0.6, which can go from 0.8 to 1.2, that’s a huge change. It all depends on what the test is and what it’s being monitored for.

A variety of these things will be different based on what was happening with the patient. Was the patient dehydrated? Some numbers might be off. Is the patient on a completely new drug that is making some changes? Did the patient run a marathon before they got the test? All of these things make a big difference in the way the laboratory test results can be interpreted.

At the University of Michigan, we have a Patient and Family Advisory Council, which I co-chair. Patients are actively involved in a bunch of these decisions. Many of the faculty at Michigan are working on things like patient-centered reporting. They’ve looked at patients reading their pathology reports and have figured out that patients don’t even know what the diagnosis is. There’s so much scientific jargon, which can be difficult to write out.

Similarly, we have a pathology clinic where breast cancer patients talk to their pathologists who show them their cancers. There’s national literature now on patients, by and large, who are feeling value in speaking to their pathologists. This is something that is happening in only a few places, but it’s certainly happening now.

As a pathologist, I went to medical school. No one took away my license to speak to patients. It’s just that we are in a system where that typically does not happen. But it can be valuable to speak to your pathologist.

Your laboratory pathologist’s name is at the bottom of every pathology report. You can call them. Typically, patients don’t, but I have received calls from patients and I try my best to explain their test results. I obviously can’t talk about the treatment as I’m not that well versed on that aspect, but I do know what their biopsy is showing or what their blood test is showing.

It’s complicated because you want the information to be delivered to the patient in a way that will benefit the patient. Ultimately, it is their information. Let’s say no one follows up on it and it’s been a couple of days. At least the patient will know that something happened. Let’s say you’re in a very remote part of the country. There aren’t that many providers. Nobody’s checking the reports. That would be horrible if the patient didn’t realize that they have something wrong with them.

We have many checks and balances, but sometimes, the checks and balances don’t come through. It is important for the patient to know what their report was. I’m glad in a way that they get it, but that whole process is nuanced.

Stephanie: It’s a necessarily nuanced answer that you have to give because there are so many different situations. I also appreciate that you’re part of that Patient and Family Advisory Council. Thank you for doing all the patient-led work.

Dealing with Delays in Getting Test Results

Stephanie: You talked about being in the middle of the country versus somewhere, like Michigan, where it’s highly resourced. You have lots of research there and people like you. What are the reasons why people wait sometimes longer than other places for results? Does that have something to do with who they have on staff or whether they have to outsource the reading? How does that work?

Dr. Mirza: We always talk about low-middle income countries or low-resource settings, but there are some areas in remote parts of the United States where they may not have ready access to a laboratory or a pathologist that, for example, you may have in Chicago, New York, or San Francisco.

Often, if it’s a complicated case, then all of these places have contracts, affiliations, and agreements with pathology departments. Ultimately, everybody finds a place for their pathology to be read. But that said, sometimes it can be delayed because of several reasons.

Primarily, anything that’s delayed is because the test has a turnaround time of a particular amount of time. For example, some molecular tests can take up to two weeks. It can take up to a month in some settings.

It can be delayed because of several reasons. Primarily, anything that’s delayed is because the test has a turnaround time of a particular amount of time.

Think about when the blood was drawn. I hate to give this very negative example, but let’s say the blood was drawn in the middle of a state and the closest laboratory is a three-hour drive away. A patient got the blood drawn at 4 p.m. on Friday and the cutoff for the van was 3 p.m. To them, they’ve given the blood at 4 p.m. on Friday, but the actual pick up for the blood won’t be till Monday morning.

On Monday morning, the blood will be picked up. That’ll go to the laboratory three hours away. It’ll be put on the machine. It might be a little bit complicated. They may not have an answer until Tuesday morning. But in their mind, they gave the blood on Friday, but the laboratory only got it on Monday. I’m not defending the laboratory. I’m just saying that sometimes, these things happen.

On Monday, they might get the specimen and say, “Oh, before we give a real answer, we need some specialized tests,” and then somebody like me will probably call their physician and say, “I have to run a few more tests.” They’ll say, “OK, fine.” But then it’ll be Wednesday by the time the answer comes. It can be a little bit complicated. But by and large, if it’s a simple test, it’s pretty quick.

Conclusion

Stephanie: Thank you so much, Dr. Mirza. We appreciate you joining us. Let’s continue the conversation as this is beneficial to so many people out there.

Dr. Mirza: It’s a pleasure always talking to you. Thanks, Stephanie.

Stephanie: We want to point out some incredible resources from our friends at The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, including their Information Specialists. You can reach them via phone call, email, and live chat. They also have regional support groups and peer-to-peer connection called First Connection®.

Thank you for joining. I know that there’s a lot to go through. We hope to see you at another program because hopefully, today was helpful for you. Thank you and take good care.

We would like to thank Blood Cancer United for their partnership. They offer free resources, like their Information Specialists, who are one free call away for support in different areas of blood cancer.