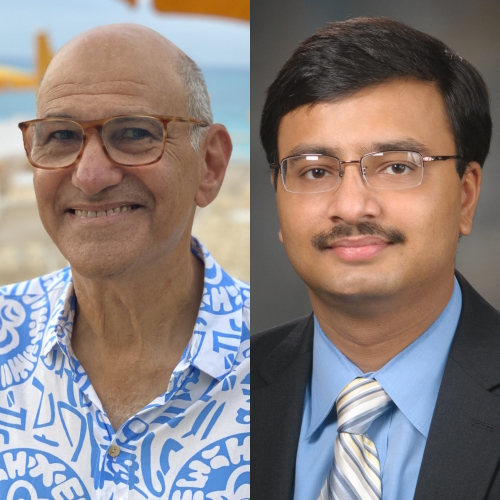

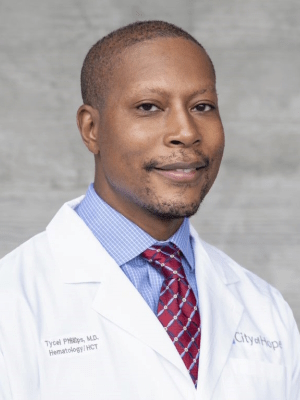

The Latest in Hodgkin Lymphoma with Matthew Matasar, MD

Interviewed by: Alexis Moberger & Jenna Jones

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

Matthew Matasar, MD, is the chief of blood disorders at the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and RWJBarnabas Health. He oversees hematologic malignancies, transplant and cell therapy, and benign hematology. He is also a professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Dr. Matasar discusses some of the most exciting news coming out of ASH 2023.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) hosts an annual comprehensive meeting that covers new research, scientific abstracts, and the latest topics in hematology.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- Introduction

- What are the updates from ASH 2023 with Hodgkin lymphoma treatments?

- When is bleomycin used in treatment for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma?

- How can patients be involved in treatment decision-making?

- What is the role of radiation in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma?

- Are there upcoming treatments for Hodgkin lymphoma that patients need to watch out for?

- When is stem cell transplant considered for a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma?

- How can a patient advocate for their health?

- Will we see the use of bispecific antibodies and CAR T-cell therapy in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma?

- What is the difference between Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

- What are the symptoms of Hodgkin lymphoma?

- What can patients do when they’re having symptoms and feel like something is wrong?

- What’s the most unusual Hodgkin lymphoma symptom you’ve seen?

- How is Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed?

- What is the difference between lymphoma and leukemia?

- What is follicular lymphoma?

- Are there any lymphomas or leukemias that require genetic screening?

- What is staging in lymphoma?

- What is Burkitt’s lymphoma?

Introduction

I’m the chief of blood disorders at the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

I’m bringing updates from ASH 2023 about blood cancers to help you better understand this area.

ASH is a major organization in blood cancers. It’s the American Society of Hematology and we have a meeting every December that rotates among different cities. It’s a chance for us to present our latest data, meet colleagues and friends, and talk about future projects and how we’re going to continue to make progress towards curing blood cancers.

There are other medicines that we know are effective in treating Hodgkin lymphoma, including a family of immunotherapies called checkpoint inhibitors.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

What are the updates from ASH 2023 with Hodgkin lymphoma treatments?

There is ongoing progress in our treatment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. We have some provocative early data.

For a long time, the standard of care for Hodgkin lymphoma was the chemotherapy regimen called ABVD. That changed a few years back as we learned that using a newer medicine called brentuximab vedotin or ADCETRIS instead of one of the older chemotherapy medicines cured more people.

There are other medicines that we know are effective in treating Hodgkin lymphoma, including a family of immunotherapies called checkpoint inhibitors. We’re now getting some readout about whether we can incorporate those medicines into the first-line treatment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, either in early-stage or even advanced-stage disease. Can we cure more patients that way than with our current traditional standards?

The answer begins to look like it could be yes. There’s some very interesting data at ASH, particularly looking at older patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, showing that substituting this checkpoint inhibitor treatment for brentuximab seems to be safer and more effective, and that’s a win-win.

ABVD remains the standard of care, however, for patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

When is bleomycin used in treatment for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma?

Bleomycin is an old standard chemotherapy medicine that’s been around longer than I’ve been doing this. It’s been a standard part of older traditional chemotherapy programs in Hodgkin lymphoma. It’s the B in the ABVD and it was well-known for both its effectiveness but also its potential risks.

Chief among them is a risk of lung injury that can happen unpredictably but can be severe when it occurs. We know that it can happen more commonly in older people, although we don’t know why.

That was the impetus for some of these studies that led to progress. Can we get rid of bleomycin altogether and switch it out for some of these newer medicines? The current program of AAVD, where bleomycin was substituted with Adcetris, an antibody-drug conjugate, showed that we cured more people that way.

ABVD remains the standard of care, however, for patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma because those patients are at lower risk both for lung injury because they get less chemo and for relapsing because our cure rate is so high in early-stage disease.

Nonetheless, we do have evidence at ASH 2023. A study being presented combining Adcetris, a checkpoint inhibitor called nivolumab or nivo for short, and the VD (vinblastine and dacarbazine), showing that the four-drug combination (AN+AD) looks to be very promising in patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma.

Is it a standard yet? Nope. Is it exciting? Definitely. It’s early data. We need to see longer follow-ups and see that compared in a rigorous fashion to older traditional treatments. But the treatment looks to be safe and effective. If we can cure more people and continue to avoid the risk of lung injury with bleomycin, that will be progress.

Your doctor will be able to guide you best in choosing the right treatment if they know you and your priorities best.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

How can patients be involved in treatment decision-making?

I encourage patients to talk with their doctors before and as they’re choosing a treatment together to make sure that the doctor understands their priorities. All of these chemotherapy programs have risks and side effects. Your doctor will be able to guide you best in choosing the right treatment if they know you and your priorities best.

We teach our student doctors and our doctors in training to do this. There’s a program with the best outcomes, but the differences can be minor. If the risks with a certain program are unacceptable, then it’s the wrong treatment even if it has a 1% better cure rate. It’s not right for you as an individual.

You’re not going to give somebody who’s a professional sharpshooter a medicine that has a risk of causing nerve damage to their fingers. Their professional life will be over. Even if it’s the “right treatment,” for that person, it’s the wrong treatment. Everything is in the context of you as a patient. You have to share that openly and candidly with your doctor so you can choose well together.

If your doctor says you’re taking up too much time, you have the wrong doctor. That is unacceptable. I believe in my heart that no doctor actually feels that way. We’re all in this to win this. We show up to work every day because we want to cure people and care for people. Period.

Don’t feel that you’re burdening your doctor. We do our job best when we communicate most clearly and most authentically with our patients. I need to know you as well as possible if I can be the best doctor for you.

I’ll tell my patients that I’m their Sherpa. I’m the guy lugging the bags up the mountain. This is your mountain climb. This is your journey. I’m here to guide the way. I can’t do that if I don’t know you and if you’re not authentic with me.

Radiation treatment, effective though it may be, comes with risks. Those risks can be both short-term and, more importantly, long-term.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

What is the role of radiation in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma?

Radiation therapy continues to be a very effective treatment in managing Hodgkin lymphoma but one that we continue to try to constrain the use of. We understand that radiation treatment, effective though it may be, comes with risks. Those risks can be both short-term and, more importantly, long-term depending on where the radiation beam is shined.

Radiation is good at treating and killing cancer cells, particularly Hodgkin cancer cells, but it also touches tissue in the area where the beam is shining. If it’s shining near your heart, your doctor needs to be thoughtful about the risk of subsequent heart disease later in life after you’ve been cured. The same goes for any part of the body.

When you’re considering radiation treatment, you want to have a thorough and informed discussion with both your medical and radiation oncologists to understand what their understanding is of your personalized late-effect risk given the dose, where the beam will shine, and your personal characteristics.

Some studies are now being deployed and developed to try to develop the next-generation immunotherapies that could hold promise for our patients.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

Are there upcoming treatments for Hodgkin lymphoma that patients need to watch out for?

An area of both unmet need and promise is: what do we do when all of our current excellent treatments have failed? Thank God this is not common. We have a very broad and very encouraging treatment armamentarium. We have a lot of tools in the bag.

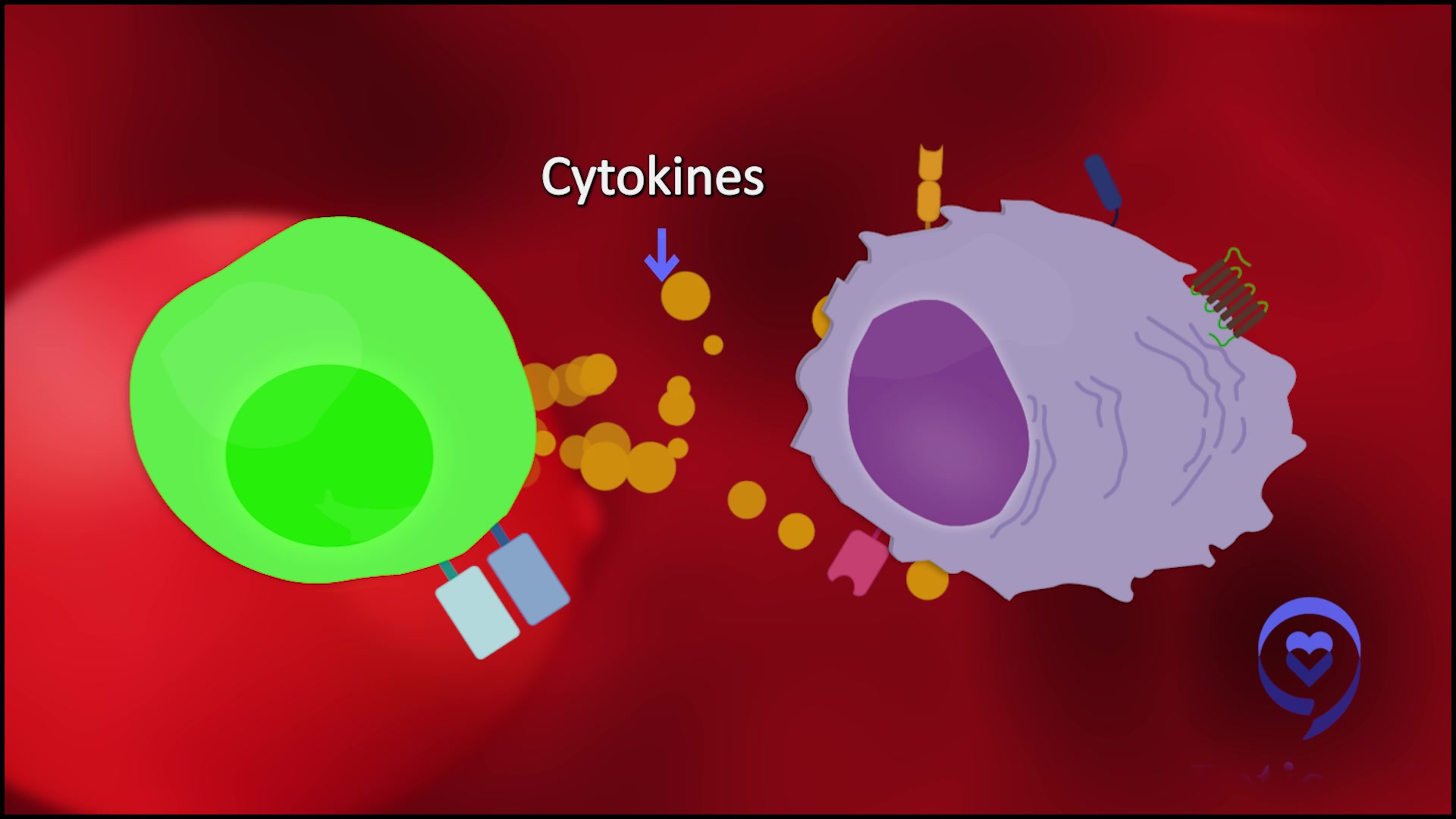

Despite that, there are still situations when all of our treatments fail patients, including this family of immunotherapies, these checkpoint inhibitors. What do we do when even checkpoint inhibitors have failed our patients? What’s after that has been our question.

Some studies are now being deployed and developed to try to develop the next-generation immunotherapies that could hold promise for our patients, even when our current treatments have failed. We don’t have data on those yet, but we’re seeing those studies being described, developed, and opened. We’re seeing that at ASH and that’s encouraging.

One study we have open at Rutgers is next-generation immunotherapy, a drug called favezelimab. This targets a different mechanism of immune activation. It’s being looked at in combination with checkpoint inhibitor treatment in patients who have been failed by checkpoint inhibitors alone, hoping that this dual immunotherapy could work even when single-agent immunotherapy has failed.

For people who’ve been failed by good first treatment, if they’re fit and eligible, receive an autologous or from-self stem cell transplant.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

When is stem cell transplant considered for a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma?

The way that we often approach Hodgkin lymphoma is we give good first treatment with the hope and usually expectation of cure. Despite that, a smaller percentage of patients will be failed by that treatment and require additional therapy.

For people who’ve been failed by good first treatment, if they’re fit and eligible, receive an autologous or from-self stem cell transplant. That treatment can cure patients even after being failed by traditional chemotherapy. How to get people to and through that treatment is a little bit individualized, but it’s generally seen as a two- or three-step approach, sometimes described as a triple jump.

Step one is to get the disease into remission and shrink it down. We do that with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or a combination. How best to do that first jump is very personalized.

Once somebody is in remission, God-willing, then they go into step two, which is the stem cell transplant itself. What that is fundamentally is a round of high-dose chemotherapy with or — increasingly — without radiation as part of that.

A small percentage of your body’s stem cells, which are filtered out of your blood, are collected and frozen. You get six days of intensified chemotherapy. On the seventh day, you rest. Your stem cells are thawed and given back to you as an antidote to the chemotherapy to allow you to recover quickly.

Part of the problem with high-dose chemotherapy is that it wipes out, God-willing, every last of those Hodgkin cells, but it also will temporarily empty your bone marrow.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

How does using your stem cells help treat the cancer?

Part of the problem is calling this treatment a transplant. It’s a misnomer. There’s no transplantation going on. When we write about this, what we use is high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell rescue. What that translates to is a round of intensified chemotherapy and giving your stem cells as an antidote to the chemotherapy.

Part of the problem with high-dose chemotherapy is that it wipes out, God-willing, every last of those Hodgkin cells, but it also will temporarily empty your bone marrow because those cells are sensitive to that chemotherapy.

By giving you your stem cells back, those cells know what to do. They go back to the bone marrow space that’s been temporarily emptied by the chemotherapy. They’re seeds planted in fertile soil. They start to grow anew and allow you to start making new blood cells, typically about 10 days later.

The treatment with an allogeneic transplant is a little bit of a tightrope walk.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

When do you use your stem cells versus a donor’s?

There are two different types of transplants. There’s the one that is called autologous or from yourself, which is not a transplant. It’s an antidote.

A situation when you’re doing a donor stem cell transplant is called an allogeneic transplant or from someone else; that’s a transplant. You are transplanting someone else’s immune system into your body.

That’s a very different treatment with very different purposes. The donor stem cells are the treatment because what we’re asking those cells to do is to make a new immune system and have that new immune system prevent the cancer from coming back. It is the ultimate immunotherapy.

An allogeneic stem cell transplant has risks and rewards along with it. It’s great. It can cure Hodgkin lymphoma even when chemotherapies have failed. That’s very powerful. But that new immune system needs to be managed.

The treatment with an allogeneic transplant is a little bit of a tightrope walk. If the new immune system gets too active, it can start attacking not just cancer cells but healthy cells. That’s graft versus host disease (GvHD) when the new immune system attacks your body.

If you suppress that immune system to keep it from being so hyperactive and injuring healthy cells, now your immune system is lowered and you’re at risk for infections. It’s a balancing act and that’s the challenge with donor transplants. And that’s why specialists do this.

Ask for a second opinion. Don’t worry about offending anyone or hurting their feelings.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

How can a patient advocate for their health?

This is an important point and a great challenge. There is a lot of different care given in this country. Some of it is excellent and some of it is less. There’s a lot of inequality and inequity that comes from that observation, but it’s the truth of it.

I worry that patients are uncomfortable, shy, or defer to their doctors. They don’t want to be a squeaky wheel or hurt anyone’s feelings. This is nonsense. This is your journey and this is your life.

Ask your doctor: How up-to-date are these data? How do you keep up to date? How did you arrive at this decision? Is my case reviewed at a tumor board or with your colleagues or are you making these decisions in a vacuum? Where would you recommend I get a second opinion? If it’s a community center, should I go see an expert? The answer is often yes.

A good community oncologist gives excellent care nine times out of ten and will welcome a second opinion from a local academic expert because it gives them additional confidence and support and reassures the patient that they’re getting good care. We all want our patients to be confident in and comfortable with the care they’re receiving.

Be a squeaky wheel. Ask for a second opinion. Don’t worry about offending anyone or hurting their feelings.

Immunotherapy is effective, active, and powerful in Hodgkin lymphoma.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

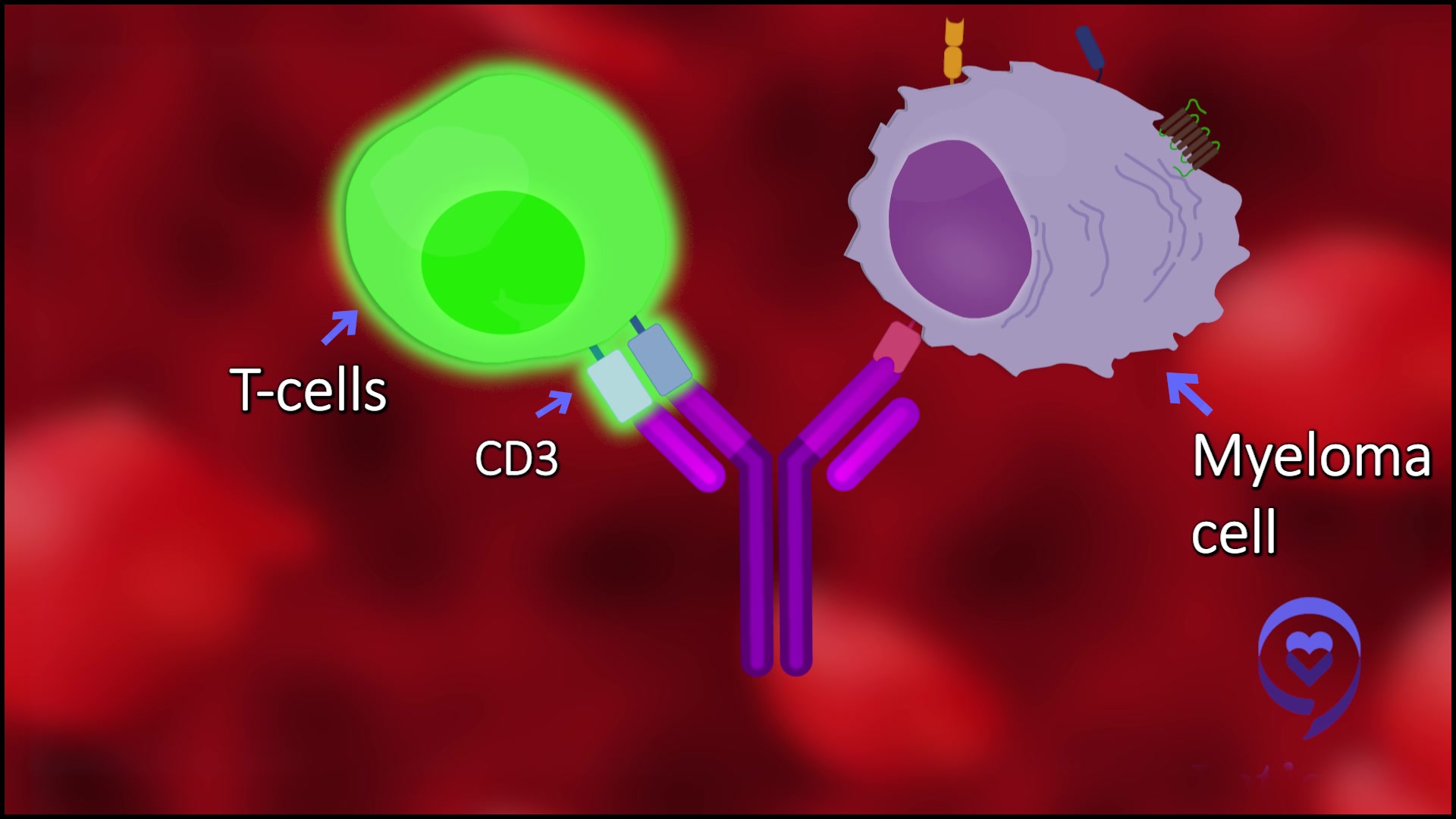

Will we see the use of bispecific antibodies and CAR T-cell therapy in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma?

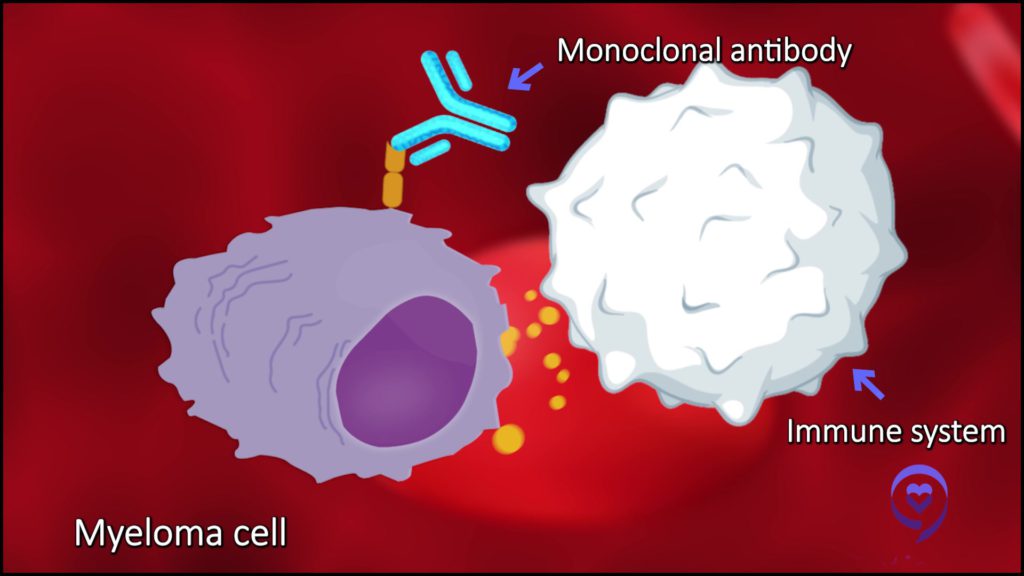

Truthfully, not yet. It’s an interesting question why. In many ways, we see that immunotherapy is very powerful in treating Hodgkin’s lymphoma. This family of checkpoint inhibitors helps a lot of different types of cancer. They can help non-Hodgkin lymphoma and other types of cancer sometimes.

They don’t work in any disease better than they work in Hodgkin’s. Hodgkin’s is the paragon. It’s a shining example of how these treatments can help patients.

We know immunotherapy is effective, active, and powerful in Hodgkin lymphoma. Why haven’t we been able to develop CAR T and bispecifics in this disease? I don’t know, but we’re working on it.

All these lymphomas are unique illnesses with their unique ways of behaving. They range from very slow-growing illnesses to very fast-growing illnesses and everything in between.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

What is the difference between Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma?

Lymphoma is not one disease. There are more than 100 different types, all of which come from lymphocytes or immune cells.

One of these lymphomas is called Hodgkin lymphoma and the others are very creatively called non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Why? Because they’re not Hodgkin lymphoma.

All these lymphomas are unique illnesses with their unique ways of behaving. They range from very slow-growing illnesses to very fast-growing illnesses and everything in between.

We generally lump them into two families, one that we call indolent or more naturally slow-growing and aggressive or more naturally fast-growing. These tend to present a little bit differently.

The most common way to find an indolent lymphoma is accidentally doing testing for other purposes. Let’s say a patient had a kidney stone and got a CT scan and there were some small swollen lymph nodes in there. A biopsy is done and, lo and behold, they find lymphoma that wouldn’t have been found if it weren’t for these other tests.

Aggressive lymphomas tend to make people sick and announce themselves. Swollen glands, a new lump, or symptoms like fevers, drenching night sweats, unexplained weight loss, progressive profound fatigue, pain, something wrong that is new, persistent, and progressive — those lead people to go and see a doctor to see why.

Common symptoms for patients with a new diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma can also include shortness of breath, progressive fatigue, and drenching night sweats.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

What are the symptoms of Hodgkin lymphoma?

Hodgkin lymphoma has unique symptoms that are traditionally associated with it. Most commonly, it’s swollen glands, typically in the neck or the armpit than in the belly or groin.

Common symptoms for patients with a new diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma can also include shortness of breath, progressive fatigue, and drenching night sweats.

There’s a specific and uncommon but peculiar symptom of feeling pain right after drinking some alcoholic beverage, oftentimes in the middle of the chest. If you have that symptom, it always turns out that you have Hodgkin lymphoma. It’s almost diagnostic of this disease. I don’t know why, but it’s the truth.

Itchiness is not an uncommon way for Hodgkin lymphoma to announce itself. There’s all these traditional stories that we all know. A common story leading to a Hodgkin’s diagnosis can be, “I’ve been itching for the last 12 months. I saw my internist and they sent me to an allergist. They did a skin biopsy and put me on antihistamines. They helped for a little while, but then I got itchy again. They gave me steroids and that helped. I stopped the steroids and got itchy again. Finally, somebody said, ‘Maybe we should do an X-ray or a CAT scan or something.’” Then they find out it’s been Hodgkin’s all along.

When patients ask me what the correlation is between itchiness and lymphoma, I say it’s evil humor. It’s something that the Hodgkin’s is secreting into the body to cause itchiness. We don’t know what that substance is, but it’s a real thing.

If you’re not getting a satisfactory answer, if you’re continuing to feel unwell, you need and deserve to know why.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

What can patients do when they’re having symptoms and feel like something is wrong?

This is challenging because doctors’ brains are trained to seek the most likely answer. There’s a phrase that everybody hears in medical school that goes, “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.”

Common things are common. If you’re an internist, if somebody is itchy, nine times out of ten, chances are it’s because they have a new detergent, eczema, or some seasonal allergy. It’s usually not Hodgkin’s. It’s not a common disease.

From the patient’s perspective, you need to not take no for an answer. If you’re not getting a satisfactory answer, if you’re continuing to feel unwell, you need and deserve to know why. Ask for additional testing or additional referrals until somebody can figure out why.

There’s this family of not very well-understood, illnesses called paraneoplastic syndromes.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

What’s the most unusual Hodgkin lymphoma symptom you’ve seen?

Some rare but awful things can be symptoms of Hodgkin lymphoma or other lymphomas. There’s this family of not very well-understood, illnesses called paraneoplastic syndromes. It means some sort of illness that’s being caused by the cancer but not from the cancer.

A range of paraneoplastic syndromes can occur. Some of these can be very, very devastating, including neurological or even brain illnesses that are caused by the body’s reaction to the cancer in an indirect fashion. They can be very confusing because they’re very rare and can be devastating.

Hopefully, a diagnosis will be made. Paraneoplasia usually gets better when the cancer gets better. Not always, but usually.

A scan never diagnoses cancer. The only thing that diagnoses cancer is a pathologist.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

How is Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed?

Often, when somebody meets me, it’s because they’ve been diagnosed with lymphoma already but not always. Sometimes people will be referred for an evaluation to guide that diagnostic process because somebody is worried that it could be Hodgkin’s.

There’s a very clear process for how you go about diagnosing Hodgkin’s lymphoma. You have a clinical suspicion that leads to imaging, which will then show swollen glands or other growths that are suspicious of Hodgkin’s lymphoma or some other illness.

A scan never diagnoses cancer. The only thing that diagnoses cancer is a pathologist, a doctor who looks at a diagnostic-quality biopsy specimen under a microscope.

Lymphomas are cancers of lymphocytes; that’s a biological term. Leukemia means cancer in the blood. It’s a geographical term.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

What is the difference between lymphoma and leukemia?

This is a point of confusion because these terms get bandied around a lot. Lymphomas are cancers of lymphocytes; that’s a biological term. Leukemia means cancer in the blood. It’s a geographical term. It doesn’t tell you anything about what type of cancer it is.

You can have breast cancer that is in the leukemic phase, meaning it’s a breast cancer, but it’s spread into the bloodstream. You can have prostate cancer, in the leukemic phase. You can have lymphomas that are leukemic lymphomas. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is a lymphoma that is leukemic. It’s a lymphoma in the bloodstream.

Other types of leukemia are not from lymphocytes but from other types of immune cells. The most common of those is acute myelogenous leukemia or AML. That’s a type of leukemia that comes not from lymphocytes but from myelocytes, a different type of immune cell.

As far as symptoms, how do lymphoma and leukemia differ?

Leukemia is a geographic description. Some leukemias have no symptoms. You show up for a routine blood test and the doctor sees something and refers you to a hematologist.

Some types of leukemia make people very, very sick very quickly: progressive fatigue, weight loss, and a loss of appetite. What doctors very unpleasantly label failure to thrive, which means the patient is sick and getting sicker.

Follicular lymphoma is an indolent, slow-growing lymphoma. Most commonly, people with follicular lymphoma will be diagnosed before they ever have symptoms.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

What is follicular lymphoma?

Follicular lymphoma is most common in America and similar countries. It’s the most common slow-growing form of lymphoma.

It’s called follicular not because of hair follicles but because of the stage we think that lymphoma develops. As lymphocytes grow up or mature, they transit through a lymph node. Lymph nodes have these little follicles in them, which are areas where lymphocytes train how to fight infections and mature. While they go through those little follicles, we think that’s the step at which the mutation occurs.

What symptoms are associated with follicular lymphoma?

Follicular lymphoma is an indolent, slow-growing lymphoma. Most commonly, people with follicular lymphoma will be diagnosed before they ever have symptoms. For example, they go for a routine mammogram and the breast tissue is healthy, but there’s a swollen gland in the armpit. That will lead to a biopsy and the biopsy will show follicular lymphoma. Any number of stories like that.

Sometimes people will have follicular lymphoma and be sick from it. The most common symptoms would be progressive fatigue or if a lymph node is growing in a spot that’s pushing on a nerve, it may cause pain.

Is follicular lymphoma genetic?

Follicular lymphoma is a genetic illness insofar as we think that it arises from randomly occurring mutations in those lymphocytes in the majority of patients, but it’s not genetic in terms of hereditary.

It’s not passed on from parent to child in a direct fashion. If you’re diagnosed, your children don’t typically need to be screened or tested to see if they’re at risk for follicular lymphoma. If you have a family member who was diagnosed with follicular lymphoma, it doesn’t mean that you need to go and get a screening test of any sort.

The only one I would actively screen for is a rare form of T-cell lymphoma called either ATLL (adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma) or HTLV-1-associated leukemia/lymphoma.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

Are there any lymphomas or leukemias that require genetic screening?

Never say never. There’s a lot of variety in my world and there are some illnesses that have a more clear familial relationship.

The only one I would actively screen for is a rare form of T-cell lymphoma called either ATLL (adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma) or HTLV-1-associated leukemia/lymphoma. It’s an uncommon form of lymphoma in America that’s caused by a virus that can be passed from parent to child.

Not everybody with that virus will develop lymphoma, thank God. But if there’s a parent who develops ATLL associated with HTLV-1, some experts might consider screening children to see if they carry the virus. Whether they need to be screened for lymphoma if they do have it is unknown, but that’s information that some families will choose to seek.

For most forms of lymphoma, even stage 4, which means it’s in lymph nodes and other tissues, is not the bad news that it is with other types of cancer.

Dr. Matthew Matasar

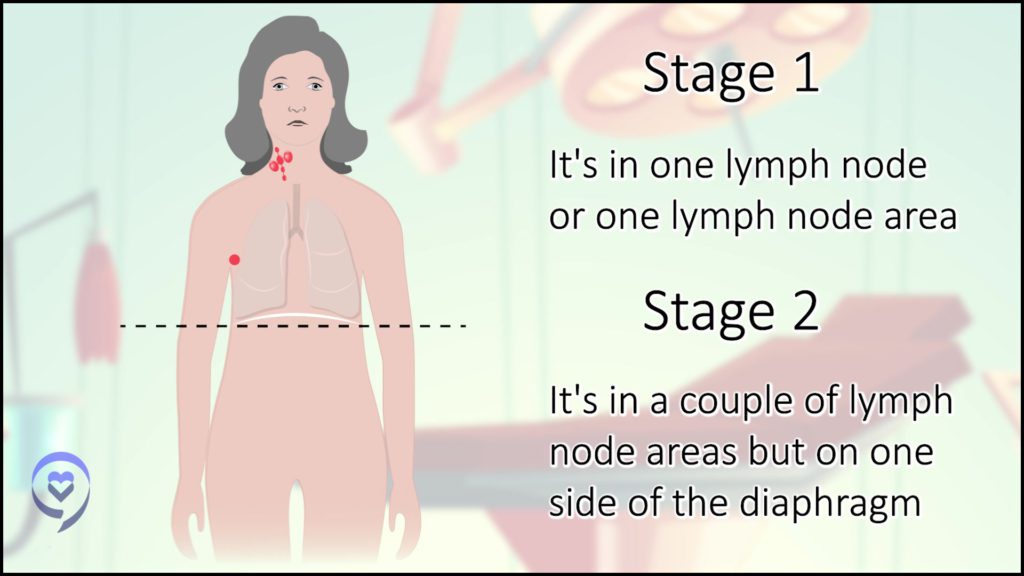

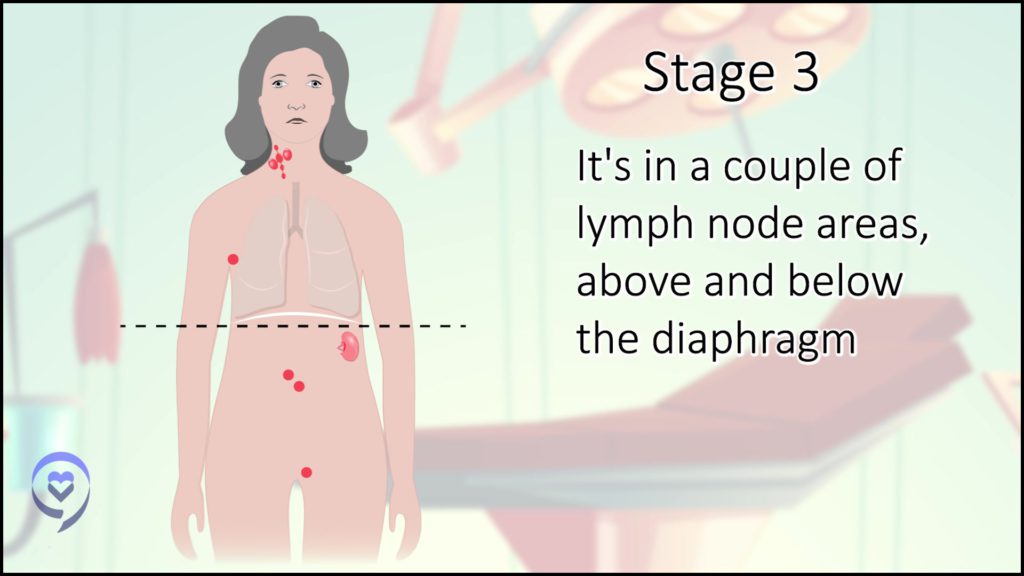

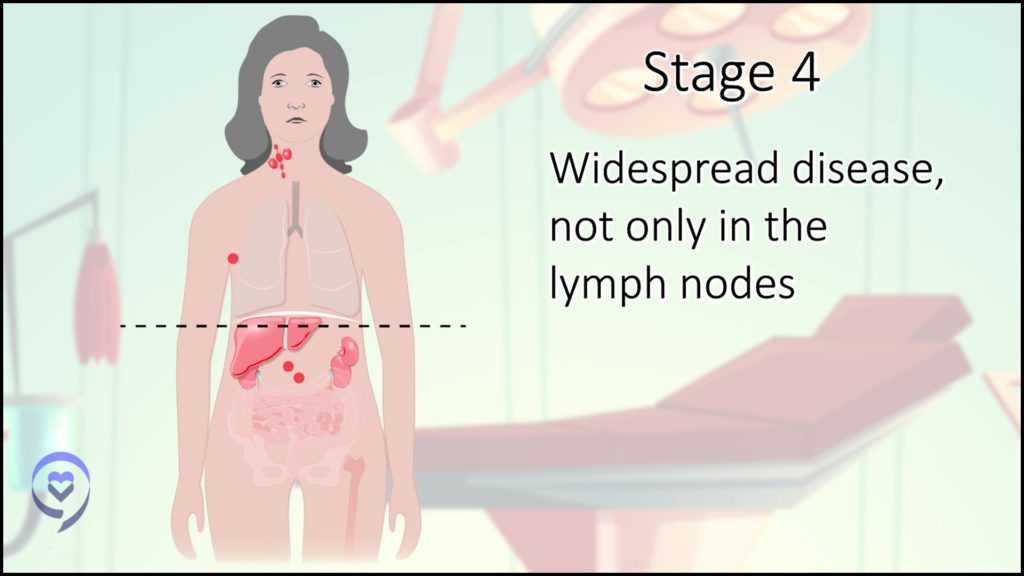

What is staging in lymphoma?

Staging means where the cancer is in your body. The stage for some types of cancers is super important, like breast cancer, lung cancer, and colon cancer. For cancers that start in an organ in the body, the stage is king. Stage 1 means we got it early and stage 4 is often a challenging conversation.

The stage of lymphoma is not as important. For most forms of lymphoma, even stage 4, which means it’s in lymph nodes and other tissues, is not the bad news that it is with other types of cancer.

Stage 1 typically means involving lymph nodes in one area in the body, like the left neck or the right groin.

Stage 2 means multiple lymph node areas but on one side of the body. Stage 2 is lymph nodes either above or below the diaphragm.

Stage 3 is lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm.

Stage 4 is in lymph nodes and other parts of the body, like some other tissue, the bone marrow, or an organ like your lung, liver, or skin.

What is Burkitt’s lymphoma?

Burkitt lymphoma is a less common form of highly aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. There are three different types of Burkitt lymphoma.

One is endemic Burkitt lymphoma and this is usually found in children in Africa. It’s associated with infection with both Epstein-Barr virus and often malaria. It typically shows up in children with a very large mass in the jaw, sometimes with illness throughout the body. In America, that’s much less common, thankfully.

The two types that are more common in America are sporadic Burkitt’s and a secondary form, which is associated with HIV, is immunodeficiency-related Burkitt lymphoma.