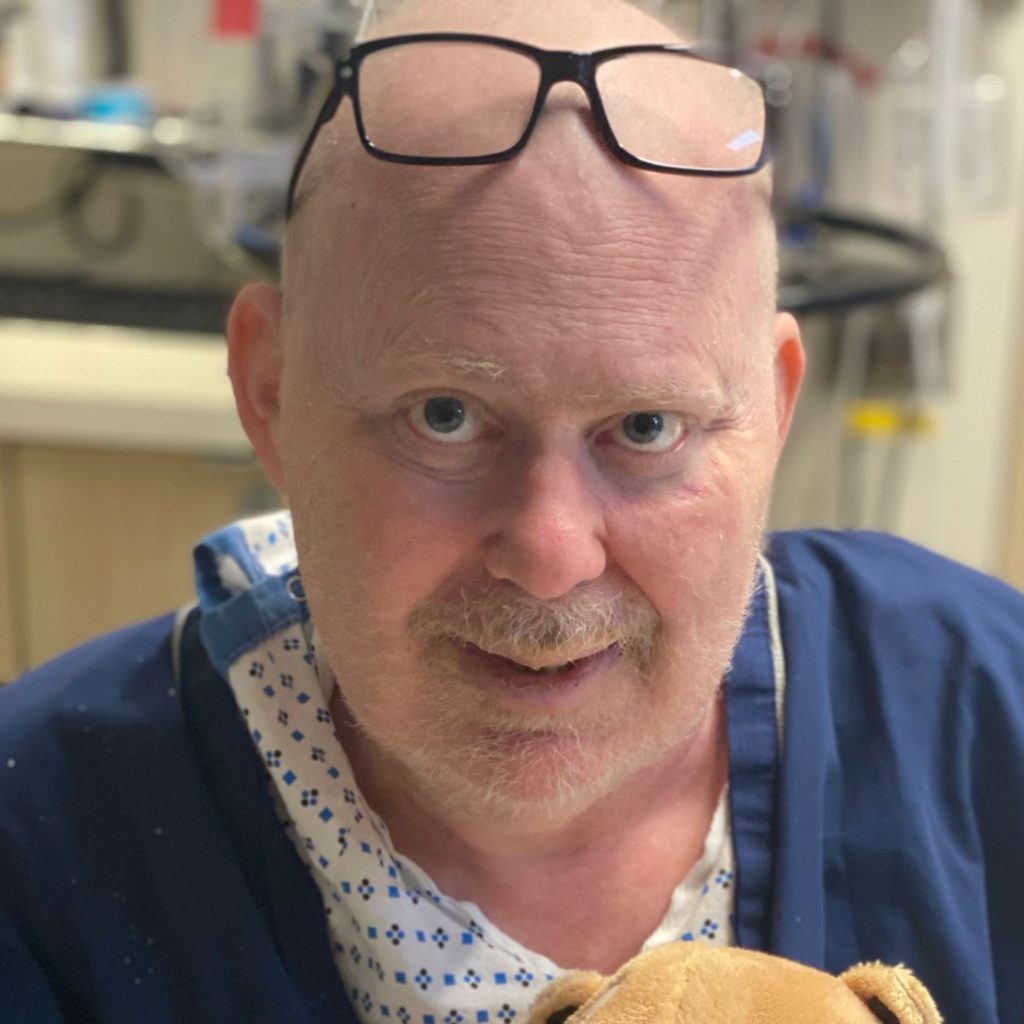

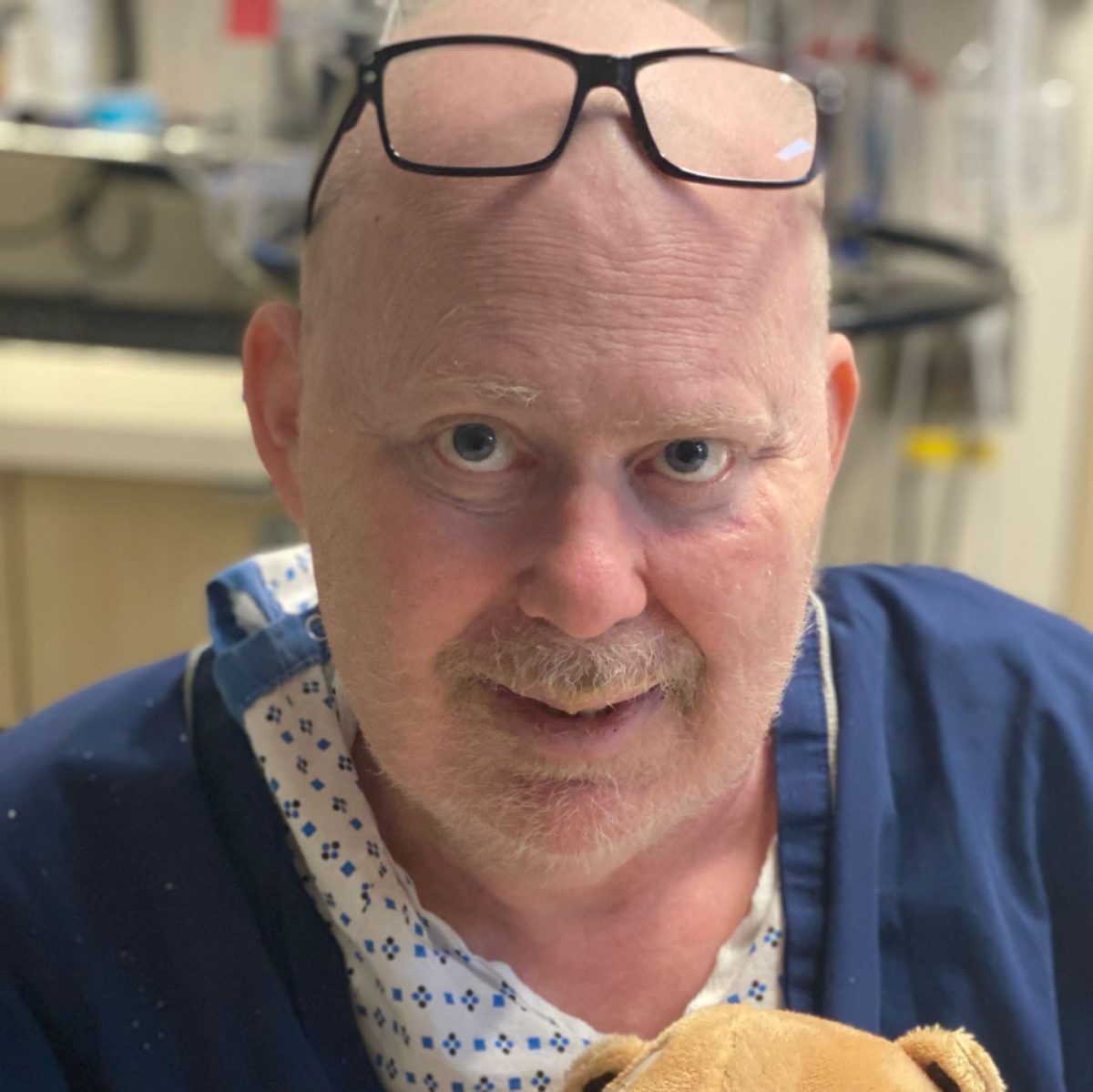

Jonathan’s Stage 4 Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Story

Jonathan was only in his 40s when he was diagnosed with stage 4 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

His story is full of twists and turns as he dealt with a secondary cancer, CNS lymphoma.

Jonathan shares going through R-CHOP chemotherapy, high-dose methotrexate chemotherapy, focal radiation, and an autologous stem cell transplant. He also discusses the life lessons he learned from his cancer journey.

Thank you for sharing your story, Jonathan!

My mistake, to the extent I made one, was thinking that I would know how it all would go at the beginning. I think you’ve got to realize that this can be different than what you expect.

- Name: Jonathan S.

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

- Secondary CNS lymphoma (SCNSL)

- Staging: Stage 4

- 1st Symptoms:

- Severe shoulder pain

- Tests & Scans:

- X-ray

- Ultrasound

- CT scan

- MRI

- PET scan

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Treatment

- Chemotherapy

- R-CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone, rituximab, and vincristine

- 6 rounds

- Methotrexate

- 4 rounds initially

- Additional 4 rounds

- Another 2 rounds

- R-CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone, rituximab, and vincristine

- Focal radiation

- 12 rounds

- Autologous stem cell transplant

- Chemotherapy

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Pre-Diagnosis

- Scans & Tests

- DLBCL Diagnosis

- 1st Treatment

- Recurrence of Cancer

- Stem Cell Transplant

- Major Complications

- Being in Recovery

- Reflections

- How does it feel recounting your whole story?

- How have you been able to get through so many twists and turns?

- Support from family, friends, and work

- How life changes after cancer

- Did you ever wonder, “Why me?”

- How did cancer affect your relationship with your wife?

- Both patient and caregiver having support from friends

- Final message of advice

Pre-Diagnosis

Introduction to Jon

I’m in my late 40s. I live in the suburbs of New York City with my wife and three children: two daughters, ages 15 and 13, and a son who’s eight.

I’ve been married to my wife for 18 years, known her for 23. She’s been a rock during this period.

Professionally, I’ve worked on Wall Street for over 20 years, mostly as an equity research analyst. I currently work at one of the big banks in their asset management division.

In terms of hobbies, I like reading. I like traveling. I’ve been to over 35 countries, and I used to enjoy working out. I’m doing less of that than I was, but I hope to get back to it.

I grew up in South Florida, actually, and came to New York a little over 20 years ago for work purposes. In fact, I lived in New York City for 15 years, beginning about a month before 9/11, so it was kind of a cruel introduction to New York City.

How would you describe your DLBCL story?

I guess I’d say it’s been full of twists and turns and one hurdle to jump over after another. It hasn’t ended yet, so I’m still in the middle of it.

It’s about sort of keeping a positive attitude and dealing with each thing as it comes, and the idea that you really don’t know what road this is going to take when it starts.

I thought that I had a pretty preordained notion of what this was going to be when I first got diagnosed, and it’s been nothing like that.

So just keeping a flexible mind and an open mind and taking things maybe not one day at a time, but one week at a time.

1st DLBCL cancer symptoms

I felt severe pain in my shoulder. It was excruciating, and after about three or four days, I made an appointment with an orthopedic surgeon, an orthopod, to look at it.

He took an X-ray, and he diagnosed rotator cuff tendinitis and prescribed a steroid and physical therapy. I took the steroid, and it flared the pain down, as steroids tend to do, and it enabled me to go on vacation for a week.

I came back, and a little while later, I started the physical therapy. I noticed a lump under my armpit, a modest-sized lump, but I didn’t think that much of it. Then I went to physical therapy.

About the third session, I was doing an exercise where I had my armpits sort of showing to the physical therapist. She felt it and said, “What’s this?”

I said, “I don’t know. It’s been there for a little while.”

She said, “You better get it checked out.” And so I made an appointment for three weeks later with my general practitioner, my primary care doctor.

I thought about it, and I said maybe three weeks is too late. I called back and got an appointment the next day, and she checked it out.

Why did you decide to get an appointment earlier?

I think I said, “I believe this could be something serious. I don’t know if it’s something serious, but I’d like to get it checked out sooner rather than later, and it’s getting bigger.”

Scans & Tests

What happened at the appointment?

She looked at it at first, thought it was a cyst, and said, “But I think we should do an ultrasound to make sure it’s nothing more nefarious.” That phrase stuck in my mind. The word “nefarious” just creeps me every time I hear it now.

We did the ultrasound, and it showed it wasn’t a cyst. Then that precipitated a litany of tests. There was a CAT scan, there was an MRI, there was a PET scan, there was a lymph node biopsy, and there was a bone marrow biopsy. All the sort of traditional tests that are done.

I think it was the lymph node biopsy that solidified for sure the diagnosis, but they suspected it after the MRI.

I think we did a PET scan also, which showed that the lymphoma had spread above and below the diaphragm and to the left and right sides of the chest, so it was staged at stage 4.

I would advise anyone who’s having a bone marrow biopsy that it’s painful and that if you could, do it under sedation. I had two of them — one under sedation, one not under sedation. The one under sedation was much more pleasant.

What was the sedation like?

It was more like twilight or a little more. It was sort of like what you get for a colonoscopy. You don’t feel anything. You woke up and it had happened, and you didn’t feel any pain.

Any guidance for what would have helped before the tests and biopsies?

I would’ve wanted to know a little bit more about the potential diagnoses. I guess what the point of each scan was while we were doing it. I think that’s really it. I had a fair bit of information.

Did you experience claustrophobia from any of the scans?

I didn’t experience any claustrophobia from the MRI. I know a lot of people do. If you do, make sure you have good earplugs [or] that they’ve given you good earplugs so it’s not as loud, which just adds commotion to the claustrophobia.

Know that it’s only going to be 25-30 minutes and that it does end. You’ll get through it.

DLBCL Diagnosis

How did you process the diagnosis?

I don’t think you fully process it in the moment. It takes a little while. I think I found out over the phone.

My wife was out but came home about 30 minutes later, and we sat at the kitchen table. The kids were at school, and we just talked, cried, and said we’d get through it together.

Stage 4 was scary. I read a little bit about how stage 4 is different than it would be for breast cancer or pancreatic cancer or something like that. It was a tough period between when I got the diagnosis and when I started the chemotherapy.

It was tough physically. I had a six-centimeter mass underneath my armpit, and it was hurting. I would go around with ice packs under my armpit, which sort of seemed ridiculous, but it gave me relief.

Physically, I was in bad shape, and I was not strong. I was tired. Then mentally, it was hard not to be doing anything about it.

It was about two or three weeks before we got the chemotherapy going. Once the chemotherapy started, the R-CHOP, I felt like at least something was happening that would fight the cancer.

How did you decide where to go for treatment?

I started at a regional medical center, and that’s where my primary care physician was. It’s a perfectly acceptable place. I mean, there are good doctors there, and it’s a reasonable option.

But I’m lucky to live in the suburbs of New York, where there are top-notch, best-in-class hospitals for cancer and places for cancer.

We have a friend who is a nurse at Sloan Kettering who suggested that I look into Sloan Kettering, and it’s not always easy to get in there. She pulled a few strings and helped us get in there.

I was pretty far down the road. They were going to start chemotherapy at the regional medical center, and they kept calling me to put a port in. I kept delaying it and delaying it because I knew I wanted to get into Sloan Kettering.

I’d had the lymph node biopsy at the regional medical center, but I think it’s important for someone to keep in mind that even if you’re a little down the road, if you have the opportunity to switch to a world-class place, you go to the best place you can.

If this had been a straightforward, plain vanilla case, I think the regional medical center would have been fine. I would have done the R-CHOP. It would have put me in remission, and I would have stayed in remission, and they could handle that.

But as we’ll talk about, there were a lot of twists and turns, and that was fortuitous to go to a world-class place to handle those twists and turns.

1st Treatment

Going through R-CHOP

I didn’t find the R-CHOP as bad as most people seem to find it. I tolerated it. I felt well enough. If I had chemotherapy starting at 9:00 and was done by 2:30 or something, I felt well enough to come home and work from home.

I felt well enough that day to go take a walk. Even cumulatively, they say it gets worse after the third or fourth. I didn’t really feel it that much. So I was on the lucky side originally.

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

The Patient Story: With R-CHOP, it’s a three-week cycle. It’s an infusion at the beginning, and then you get another infusion week four essentially, three weeks later.

Yes, that’s how it works. You do six of them typically.

Experiencing hair loss

I did experience the hair loss. After the second cycle, I was shedding hair in the shower and the pillow, and I just said, “To hell with it, I’m going to shave it off.”

I had a friend shave it off with an interim step of a mohawk along the way. Not that I ever wore it like that, but there’s a picture of when he shaved it. I kind of got over it pretty quickly.

Symbolically, every time I looked in the mirror, it was a stark reminder that I had cancer.

I’m a middle-aged man, so three-quarters of my friends are bald anyway. I can understand where for a woman it would be more jarring potentially. But I thought, “My life is on the line. Who cares what your hair looks like?”

It was beginning to be Winter. Most of the time I had a winter hat on anyway, so you couldn’t really tell. Not that I cared a lot.

Did you experience identity loss with the hair loss?

Symbolically, every time I looked in the mirror, it was a stark reminder that I had cancer. I didn’t really care about it cosmetically a whole hell of a lot. But it was a reminder that you’re a cancer patient.

I’ve lost my hair now three times and grew it back, and it’s starting to grow back again. I never cared a lot about it cosmetically, but every time it’s fallen out, it’s been a reminder that I’m going through chemotherapy and that I’m afflicted with cancer.

In terms of what we told the kids, we were pretty straight up with them after I got the diagnosis that I was going to lose my hair, that I’m having chemotherapy, but that the chances of a complete recovery and long-term remission are good.

We didn’t get deep into statistics, but we said [it was] very likely. We didn’t dwell on percentages that you don’t make it or that you do get cured or recurrence or five-year survival rates or any of that.

But we just said it’s not one of these cancers where you’re doomed, and we continue to be honest. We were pretty straightforward with them.

»MORE: Patients describe dealing with hair loss during cancer treatment

Did you have scanxiety after the midway R-CHOP scan?

Yeah, I did. I mean, it seemed like it would take a day or two for the radiologist to read out the PET scan. I remember one time I had it on a Friday, and it didn’t come back until a Tuesday, which was definite scanxiety over the weekend.

You just tried to occupy your mind with other things. But every time I have a scan, I’m nervous.

»MORE: Patients describe dealing with scanxiety and waiting for results

Does anything help with the scanxiety?

No. The only thing I can say is if they tell you not to eat and it’s a six-hour window and you have a scan at noon, you can get up at 6:30 and eat a small breakfast, which makes it more bearable than having gone from dinner the night before.

You don’t want to eat [a] three-egg omelet and bacon and sausage, but you can have a piece of toast.

That’s been helpful, and I’ve been told that by physicians. Not necessarily the one ordering the scan, but it’s not going to screw things up.

Just make sure that if you’re drinking the contrast, that it’s cold and that you have a straw. [It’s] helpful just to get it down easier. That’s the only thing I can think of.

Recurrence of Cancer

Getting bad headaches

It had been about six weeks since I got the all-clear on the final scan from the R-CHOP. We had gone out and celebrated with friends who had been supportive of us.

I started getting headaches in mid-May that were pretty bad and mostly at night. I told someone it felt like I drank a 12-pack and had a massive hangover the next day.

Don’t get too fixated on the probabilities.

Then I thought my room was dry and maybe it was dehydration. That continued for about two or three weeks, and then they started getting worse. The first of June or the 31st of May, I started getting nauseous and vomiting and couldn’t get out of bed for like 18 hours.

I had known the signs of CNS lymphoma, lymphoma in the nervous system, spine, and brain. I had even had prophylactic treatment for that called intrathecal methotrexate, where they give you a spinal tap and put in some methotrexate to try to prevent it from entering the central nervous system.

So I knew the signs of it entering the central nervous system, and I called up the doctor. She said, “Come in.”

They did a scan, and they found a four-centimeter mass in the brain that was sort of pushing on the rest of the brain, which was causing the headaches [and] edema.

Sloan Kettering has regional outposts within the New York metro area, which I had gone to for most of my treatment, and they sent me immediately by ambulance to the main hospital in Manhattan.

My wife had 10 minutes to go home and pack a bag. It was pretty significant. It was pretty serious. That was clear.

Do you remember the ambulance ride?

I do remember being in the ambulance. I don’t think the full gravity of it hit me for 24 hours, but it was probably, up until recently, the hardest time I’d had with cancer. I knew the statistics on secondary CNS lymphoma, and I knew that they weren’t great.

That’s the time I would keep a good game face. Then later on, between methotrexate chemotherapy treatments, I’d wake up at three in the morning crying and thinking about my kids growing up without a dad or my wife being a widow.

That was when it hit me the most and was the toughest. That was jarring.

But I would say to people, you can read the probabilities that you have a 72% chance of surviving or whatever, but you’re a sample of one. You have a different case than other people, and you have different preexisting conditions. You have a different temperament, you have different nutrition, and you’re a sample of one.

A cancer patient told me this: Don’t get too fixated on the probabilities. I mean, if they say you have a 1% chance of making it, you should be scared. But 50/50, what are you going to do?

Treatment for secondary CNS lymphoma

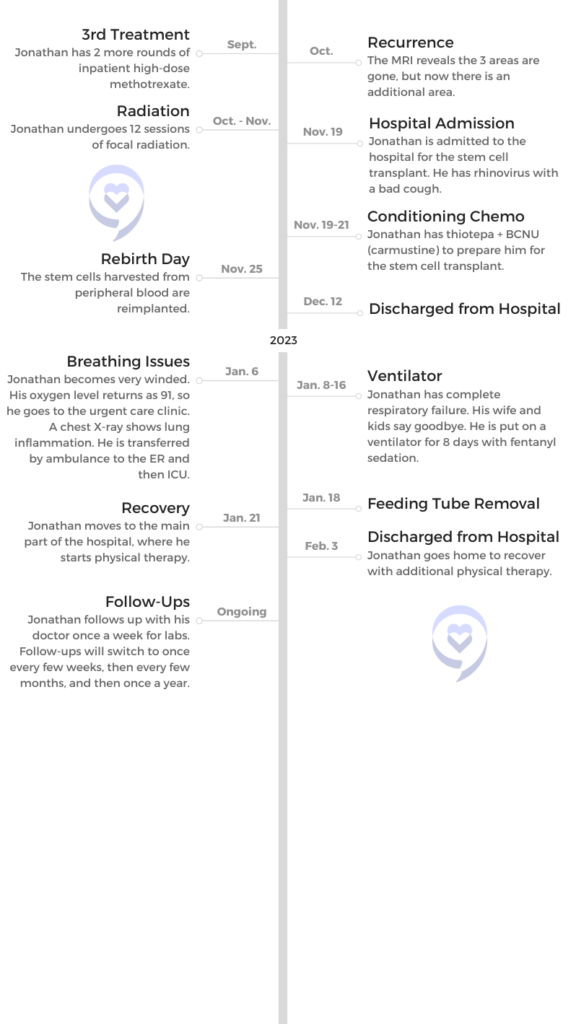

It was pretty early on that the game plan was created to do four rounds of high-dose methotrexate chemotherapy and then try to transition, if that worked, to a stem cell transplant.

There were all kinds of twists between the methotrexate and the stem cell transplant. But that was the game plan from the very early days. Methotrexate chemotherapy, for those who aren’t aware, is you get infused with methotrexate, which looks toxic and is toxic.

Then you have to excrete it from your body, stay inpatient in the hospital, and literally sort of urinate it out over three or four days. Some people, it takes six days. They don’t let you go home until your blood levels of methotrexate hit a certain threshold.

I was there for Father’s Day weekend. I was there for 4th of July weekend. Thankfully, I got out on the 4th of July itself. It sort of screwed up the summer pretty well.

But I only needed four of them, so I just kept in mind that I was investing one 4th of July to hopefully have maybe more 4ths of July.

How was the methotrexate administered?

This one wasn’t intrathecal. This was via an IV, and I never had a port up until the stem cell because I thought it was just going to be R-CHOP. If I had known the way it was going to go, I would have gone to port right away, but I never got a port.

Originally, they said, “You have good veins, and we can stick you easily.” And then my veins got shot, and it became difficult. It was just a really tough stick.

It was administered via IV, and they took your blood levels to make sure you could tolerate it. I had four times, and I was on the neurology floor in the hospital, which was interesting because I had roommates who had brain tumors that were really affecting their behavior.

I was very fortunate that this four-centimeter mass seemed to be in an area that wasn’t mission-critical to your behavior or mental acuity. Obviously, there are parts of the brain more important than others.

I had roommates who were telling the nurse they were going to break her arm or kill her, or they called 911 because the nurse wouldn’t help them call their wife. The police had to come because they were obligated to come.

Were you able to have visitors during this time?

It was enough post-COVID. I could have, I think, one visitor at a time, two visitors a day. My wife came almost every day during that period. She was very supportive.

I had friends who came the day she wasn’t coming or late in the afternoon if she had to go home. Friends kept me going, and sort of humor kept me going. You could laugh or cry, and I sort of chose to laugh. I think that’s important.

Like I said, you have your moments where you cry, but humor is very important to me in dealing with cancer, because otherwise, it’s just overwhelming. And maybe it’s a defense mechanism, but it helped.

You could laugh or cry, and I sort of chose to laugh. I think that’s important.

What is the importance of letting yourself cry and feel your emotions?

I think it allows you to be honest with yourself. If you ignore it, you’ve repressed something, and it sort of crops up anyway. You’ve got to be intellectually honest about the fact that you may not make it, but not dwell on that fact.

You want to plan for the worst and hope for the best. It’s important that you have your affairs in order, that you have a will, and that hopefully you’ve gotten life insurance before the cancer diagnosis because it’s pretty hard to get it once you’ve had the cancer diagnosis. But you want to plan for the worst, and hope for the best.

The humor wasn’t just for me. We told the kids about the recurrence, and I said to the three kids, “Any questions?”

I expected them to say, “What’s the chance that you make it? How sick are you going to be from the chemotherapy?”

And my daughter raises her hand and says, “Can we still go to the Harry Styles concert if you’re going to be immunocompromised?” That was humorous to me, and it showed me they were still kids.

I knew I wasn’t doing a crappy job as a parent and they were totally self-centered. It was good that they weren’t letting this completely dominate their life.

»MORE: Parents describe how they handled cancer with their kids

Stem Cell Transplant

Why was the stem cell transplant delayed?

I finished the methotrexate, and [we had] a scan that showed the brain was clear. This was in mid-July. In August, I got an infection on my arm that delayed the stem cell. We were going to do it at the end of August.

It delayed it about a week. Because it delayed it a week, the doctor wanted to do another scan to show that the brain was all clear because it had been seven or eight weeks at that point. They had a threshold of how long they’ll keep the old scan valid.

That scan showed three spots in the brain where there was still disease that were new spots, and so I had to go get two more rounds of high-dose methotrexate two weeks apart.

Then they did another scan, and those three spots had been eradicated, for lack of a better word. But there was a new spot that hadn’t been there before or was part of the original spot, or they weren’t sure.

Then I had to have 12 rounds of focal radiation, which is very targeted radiation. I would go every day, Monday through Friday, for 12 days.

I didn’t find that too bad in terms of side effects or disruption to life. Some people do, and I imagine it depends on how big an area you’re having radiation on and what kind of radiation. That was a bridge to the stem cell transplant.

How were you doing at this point?

The worst part was getting that first scan back that showed, after the seven- or eight-week delay, the lymphoma had come back in the brain, because it was literally the day before I was scheduled to go in for the stem cell transplant.

So I had mentally gotten myself ready for a month in the hospital. I had started packing a bag. You have to get yourself where you’re sort of girded for high-dose chemotherapy and being pretty sick.

Then to have that recurrence was just demoralizing, so that was the hardest. I think over time my mental state got better, but I was pretty bummed for the first three or four days after that scan.

Autologous stem cell transplant

I was there for about a month, a little less. 23, 24 days. In my case, I had thiotepa + BCNU, which is carmustine, chemotherapy in high doses. I had a three-day regimen. Right when you got in there the first day, they gave you chemotherapy. That’s one regimen.

The other, which was supposed to be good for my type of lymphoma — and just as good statistically, according to the medical studies, as the alternative, which is a slightly different group of drugs, and it’s a seven- or eight-day regimen.

They figured three days is better than eight days. I had three days of chemotherapy, followed by three days of rest. I wasn’t in too bad shape at that point. The World Cup was on; I was watching the World Cup. I felt pretty good at that point.

Then the seventh day — I think it was the seventh day — is called Your Rebirth Day, which is where they put the stem cells back.

They had collected my stem cells in early August, and meanwhile, we’re now at the end of November. That’s how long it had been delayed. But thank God the stem cells are good for like five years.

Transplant side effects

They put the stem cells back in, and then the next few days you’re okay. After that, you begin to get very weak and nauseous at times. Your white blood cell count drops to less than 0.1, which normally is 4 to 11.

Your platelet count drops. You can’t shave. Back then I was shaving. Now I’ve let the hair grow. It’s because they don’t want you to bleed because it won’t clot.

You feel kind of crappy. Your appetite is de minimis. There were days I’d have a milkshake and that was it.

I had the rhinovirus, which is basically the common cold, but I had a very bad cough through all four weeks of the stem cell transplant.

[It] made something that was difficult in the first place even more difficult, because it would keep me up at night. It was an added complication that wasn’t needed.

Stem cell transplant recovery

I think had things gone as planned, which they didn’t, a full recovery would have taken about 2 to 3 months. You have to be very careful about infection. You have to be careful about what you would eat.

You couldn’t order a turkey sandwich at a deli. You had to have food from home. Make sure you’re not eating raw fruits and vegetables that haven’t been washed or cooked. So there were diet limitations.

I was tired and fatigued. I had to use separate towels and separate pillowcases. Just from an infection standpoint, we were limited in how many guests we could have in the house.

I had to ask everyone to wear a mask and sort of pre-clear people. [It was] not just, “Have you had any COVID symptoms or been around people with COVID?” [It was also,] “Have you been around people with a cold?”

And if they said yes, then most people are smart enough to say, “I’m not going to come over.” You don’t have to really ask them not to come over.

I think a normal recovery would have taken about two months, two-and-a-half months. I had worked the whole time through all this from home [with a] very flexible schedule until the stem cell transplant started. It was a big enough recovery that I didn’t want to work during that time.

Major Complications

Why did you end up going back to the hospital?

I came home mid-December of 2022, so a few months ago. The first week I was very weak and sort of just getting my sea legs under me.

The second week I was doing better, and then the third week I started regressing. When I would walk up the steps, I would be short of breath, very short of breath, and it became apparent that something was not going as well as it should.

We had a pulse oximeter at home, which you can buy for about $15 for a good one. They used to be $35 during COVID, but they’ve come down. I would implore everybody to get one for their house because it may have saved my life.

We took the pulse ox, and it read 93 and then dropped to 91. It’s a measure of oxygen saturation and how much oxygen is getting in your blood. Anything below 95 is troubling. and sort of below 90 is really troubling.

I called the doctor, and I said, “I don’t think this is a big deal, but it’s dropping down to 91.”

He said, “Get to the clinic, the regional satellite Sloan Kettering clinic, right away.” They gave me some oxygen and took a chest X-ray and saw inflammation in the chest. [It was] sort of pneumonia-like inflammation.

It was like déja vu all over again. They said, “You can’t go home. You’ve got to get in an ambulance and go straight to Manhattan, to Sloan Kettering.” So I went in the ambulance.

Being on a ventilator

It took about a day and a half of my oxygen level dropping, and then it got to the point where it dropped so much that they had to intubate me, sedate me, and put me on a ventilator.

They weren’t sure I was going to make it. My wife brought the kids in to say goodbye, and I don’t remember it because you get sort of amnesia from the period before the sedation, like 16 hours or whatever before the sedation is given.

I was on a ventilator for eight days and came off it and started breathing on my own. They wean you off. 40% of your oxygen will come from oxygen given by them, and 60% will come from your natural breathing. Then they sort of wind it down till you get 100% your own breathing.

I made it, and I was in the ICU for another week or so and then transferred to the main part of the hospital. What I didn’t realize and now do is that you get very weak if you’ve been on a ventilator for eight days.

Your body doesn’t move basically. They “prone” you, which is [they] put you on your stomach. You can get all kinds of bedsores, and your muscle mass declines by about 2% every day that you’re on a ventilator. It doesn’t sound like a lot to lose 16% of your muscle mass, but I couldn’t walk when I came off it.

What was it like hearing you were on a ventilator?

It was tough. She didn’t initially share it with me. I pressed her after about a week of being off the ventilator. Eventually, she showed me pictures of me on the ventilator. My recollection of the room I was in was totally different than what the room looked like in the pictures.

It was like I was in my own little world. When I came off the ventilator, I woke up, and they said, “You’re at Sloan Kettering. It’s a safe place.” I thought I had been in an airplane crash and that’s why I was at Sloan Kettering, not because of cancer.

I thought that my wife and I had been in California and had to get back to the kids, the only plane she could get was a cargo plane, and we were in the cargo hold. This seemed very real to me. It must have been the dream I was having coming out of the sedation.

I said to her, “I don’t think it’s a good idea to fly home in the cargo hold, but I trust you. And if you think it’s a good idea, then we’ll do it.” Next thing I knew, I woke up at Sloan Kettering, and I was mad at her for like two days.

I didn’t realize. You can’t talk. You’ve got tubes in your mouth and in your nose. You can’t write. You can’t communicate. Nobody realizes that that’s what you thought.

What were you thinking and feeling about what had happened?

It was just hard to miss eight days of life and not know what happened. So I was very inquisitive, which is my nature, about what happened.

I also thought I was going to be a vegetable when I came out of the sedation and had all the tubes in me. My arms were so weak I couldn’t even really move them. So I thought I was sort of paralyzed, which was difficult.

But she was very good about feeding the information as I could handle it. She sort of held off on information for the first four or five days because I was just dealing with getting back to being alert and awake.

I think she was smart. She took my phone away, so I wasn’t communicating with anyone for five or six days, and I was just sort of recovering from being [under] sedation.

I don’t think you take it one day at a time, but at this point, I take it one week at a time.

What happened after you left the hospital?

Again, I couldn’t walk when I first got done with the ventilator, and a week or two later I was still bedridden. When I got in the main part of the hospital, they started doing physical therapy, and I started walking.

Literally, at the beginning, it was hard to walk from my bed to the bathroom in the hospital room. But slowly but surely, it improved. I was able eventually to do a lap around the floor. I had to stop three times.

Then I was doing well enough to get discharged, and at home I’ve continued the physical therapy. For a while I was on a walker, and I’m still on a walker. We had two walkers in the house. I named one Hershel and the other Johnny, just to keep the humor.

When you’re in your late 40s and you’re on a walker, it’s kind of not when you thought you were going to be on a walker. I’ve since graduated to a cane. I have a cane, and I think within a month or two I’ll be able to walk half a mile to a mile without any sort of balancing device.

I’d like to do a 5K by the end of the year. That’s sort of an aspiration or a goal. I don’t care what the time is.

My appetite hasn’t been quite what it was, so it’s still a recovery. I get winded walking up the steps. My stamina is not good, but [it’s] getting better.

Being in Recovery

Has this been a test of patience?

It’s been a test of patience, but I was impatient in the hospital. I have been in there so much. I worked hard at the physical therapy, and I wanted to get out. I wanted to get out by my daughter’s birthday. I had a lot of motivation.

They wanted me to go to a rehab hospital for a week, and I sort of made enough progress by working hard at it that I was able to go home. So I wasn’t that patient.

I was pushing pretty hard. I guess I’ve been patient through this long period; it’s been a year and a half. But I’m not that patient.

What is the follow-up plan?

I’m following up about once a week with labs, and we’ve done a mix of telemedicine visits and in-person visits. I don’t know how long we’ll keep going once a week for.

Eventually it’ll be once every three weeks or two weeks. I have a scan in early March to see whether the stem cell is working.

It won’t mean it’s worked because we’ll need five or 10 years of scans that don’t show anything to know that it’s worked. But at least hopefully it will have worked for three months.

Have you allowed yourself to adjust to life, or are you prepared for more twists?

It’s a bit of a mix. I don’t have huge structure to my day. I’m not working again yet. The kids are at school. My wife is busy with her life. So I have a lot of time to think. I try not to. I try to read or watch TV or do something quasi constructive.

I’ve had friends over. I’ve sort of gotten half back in the swing of life, but it’s not fully because you’re not going out a lot because you don’t want to be around crowds. You don’t have a natural social life during the day. So it’s sort of half back where it was.

Do you try not to hope too much?

Yeah, I’ve learned to temper my expectations. But you’re always hoping for the best, and it’s still a blow if something [happens]. If this scan isn’t a good result, it will be a huge blow.

You try not to get ahead of yourself. Like I said, I don’t think you take it one day at a time, but at this point, I take it one week at a time. I’ve got enough to do with physical therapy and just getting my strength back.

Reflections

How does it feel recounting your whole story?

It just underscores what a long process it’s been. I would say to anyone out there who’s first diagnosed, you just got to take it as it comes. I thought I knew how I was going to go. And just cold, hard reality smacks you in the face.

You might get lucky. I have a good friend who had R-CHOP. It was six sessions and then it was good, and he’s been cancer free for 10 years. So it can go swimmingly, or you can have a lot of twists and turns like I do.

I’ve sort of gone through it in my mind a lot, so it’s not jarring to sort of go through it verbally. But it’s been one thing after the next.

How have you been able to get through so many twists and turns?

After the first hiccup, I just became accepting that there were going to be more hiccups. Not that I didn’t get frustrated by it, and I still get frustrated by it, but I became more accepting that there were going to be hiccups.

I guess I’ve just realized that if it wasn’t for bad luck, I’d have no luck at all. I’m just thankful that I’ve made it so far after all these twists and turns. I’m thankful for every day.

I didn’t used to be, or I took things for granted. I know that’s a common sort of cliche after a cancer fight, but I guess I’ve just learned to realize that you don’t control as much as you think you control. You control how you react to it.

Support from family, friends, and work

Most of my support, of course, came from my wife and children and good friends. This experience really underscores who’s your good friend and who’s just sort of there during the good times.

I got lucky. I work at a very big bank on Wall Street, but I work on a small team of four. Without getting into detail, everyone had been touched by cancer somewhere in their family in the last two or three years.

Everyone was very flexible about schedules, doctor’s appointments, missing time, and, “Do what you got to do to take care of yourself, and we’ll work around you.” So I got very lucky. It wasn’t like people were out to get you because you were missing work a lot.

»MORE: Patients talk about working during cancer treatment

How life changes after cancer

I think any time you have an experience that highlights your own mortality — particularly at not young but sort of a much younger age than you would expect to be grappling with it — you want to examine your life, and I’ve started to.

I haven’t come to any conclusions, but you just want to make sure you’re spending your days doing what you want to do, spending it with the people you want to spend it with and who want to spend it with you.

Not that you can’t waste an hour, but just make the most out of every day. It’d be a shame to let this experience go and do everything exactly the same as before.

Did you ever wonder, “Why me?”

Yeah, and I didn’t have it at the first diagnosis. I had it when the recurrence [happened] at the end of the summer [with] the cancer in the brain.

I thought, “Why is this happening to me? Why is this not being cured or going into remission?” So there was a little bit of “woe is me” at that period of time. That was probably the worst of it.

How did cancer affect your relationship with your wife?

We’re not perfect at this. You’ve got to be careful that it doesn’t evolve into a caregiver-patient relationship and that you lose the husband-and-wife relationship to it.

We had a lot of good moments when I was in the hospital. She would come to visit me while the kids were in school for the day, and we had a lot of good talks and sort of got closer at times during that period.

But there were times, and I know she’s only looking out for my health, but it was, “Don’t eat this,” or, “Don’t drink that.” I felt like I was being controlled in terms of what I was eating or drinking more than I should have been.

But I know it was only out of love and concern. We’ve been through this whole journey, and don’t screw it up over eating a turkey sandwich or something.

Both patient and caregiver having support from friends

We both had other people that we could talk to. I’ve had friends who stood by me. [There was] one in particular who I’ve been friends with for over 40 years, who I could talk to. I have a twin brother, who I’ve talked to.

So having a support system because you can’t burden each other. You’re going to have things that you want to gripe about, and your spouse isn’t necessarily the one to gripe to.

She has good friends here in town. When they saw that she was getting overwhelmed with caring for me and caring for the children and running the household, they would say, “Hey, come on, have a drink. Come on over tonight to my house.” They would do an impromptu get-together.

She had a lot of women who formed the meal train and cooked dinners for us. She had a lot of support in the community. If we had been somewhere where we had only been for six months, I think it would have been hard without a support network to go through this.

Final message of advice

My mistake, to the extent I made one, was thinking that I would know how it all would go at the beginning. I think you’ve got to realize that this can be different than what you expect.

Keep your expectations in check, but also don’t have too many of them. That doesn’t mean you’re not fighting.

I’ve always said — and I said this to my daughter — that I don’t like when people say, “He lost his fight with cancer.” It sounds like he wasn’t trying hard.

You’re fighting it, but I don’t think of it as losing your fight if you don’t make it. That’s important for people to know.

Inspired by Jonathan's story?

Share your story, too!

More DLBCL Stories

Don S., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Symptoms: Weight loss, fatigue, enlarged lymph nodes

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy (epcoritamab)

Leanne T., Follicular Lymphoma Transformed to DLBCL, Stage 3B

Symptoms: Fatigue, persistent cough

Treatment: R-CHOP chemotherapy, 6 rounds

Robyn S., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 2E

Symptoms: Enlarged lymph nodes

Treatments: Chemotherapy: R-CHOP, R-ICE, intrathecal, BEAM; autologous stem cell transplant, head and neck radiation, CAR T-cell therapy

Stephanie Chuang

Stephanie Chuang, founder of The Patient Story, celebrates five years of being cancer-free. She shares a very personal video diary with the top lessons she learned since the Non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis.

One reply on “Jonathan’s Stage 4 Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Story”

Please pass on to Jonathan that I wish him well. I’m a 2 year survivor of MSKCC’s 4th floor neuro ward, because my DLBCL became metastatic CNS lymphoma, and I too went thru the High Dose methotrexate routine for 6 months.

Only if you’ve lived on that floor, experienced the terror of the rides to Manhattan, and the unquestioning care of the finest medical team I’ve ever known in 72 years … only then, do you fully appreciate the devastation of this disease. I’ve walked in his shoes — during COVID 2020, no les!! — and would like to chat with him in person, if that would be possible? I suspect we have much to share that is only meaningful to another alumnus of the journey.

Can LLS pass on my request, and extend my sincere thanks to Jonathan for his courage and good spirits. Sir, may you live long and prosper!