Stephen Brown’s Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Story

Stephanie Chuang

Interviewed July 9, 2021

Updated September 18, 2025

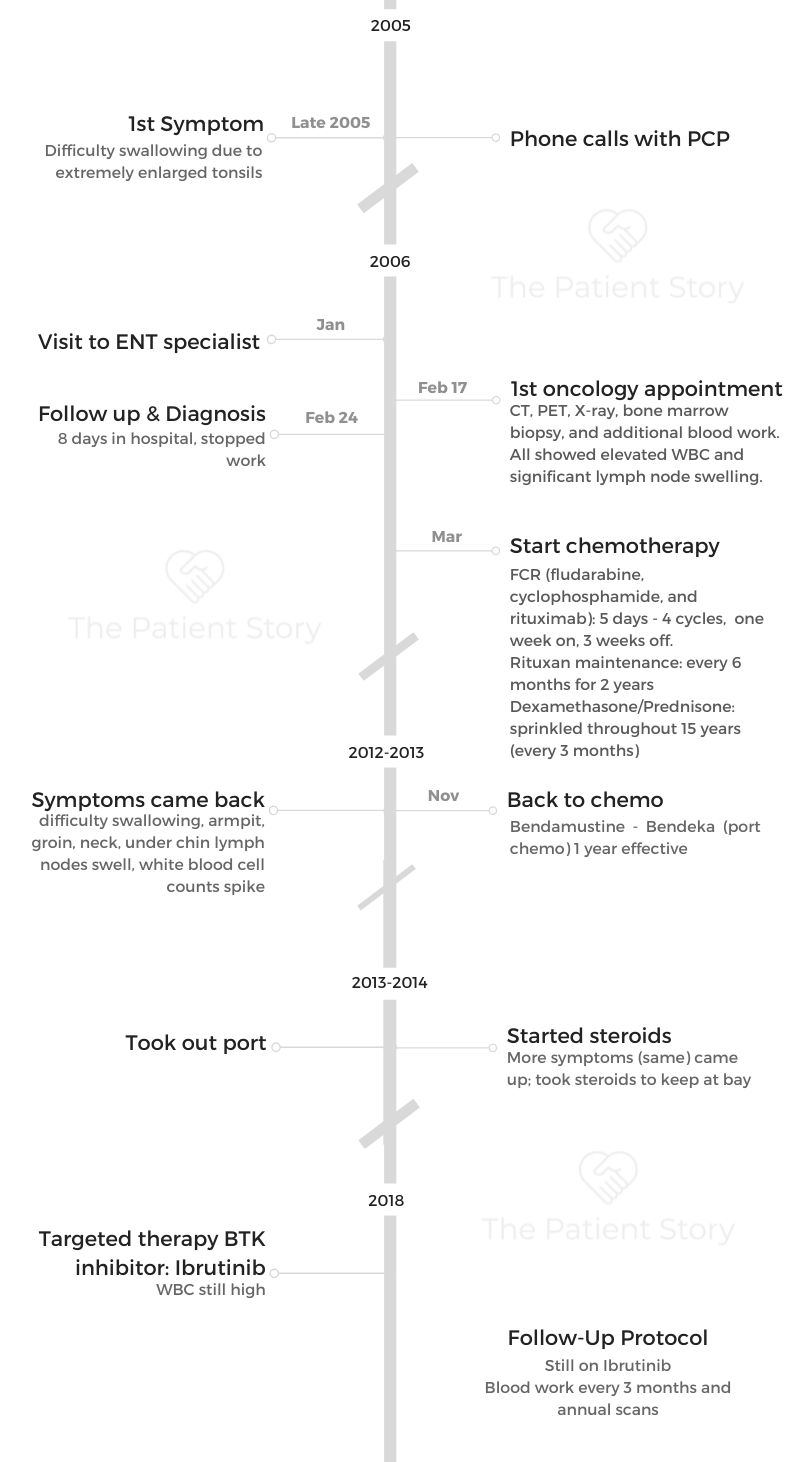

Stephen Brown was 45 years old when he felt his first symptoms that sent him to the doctor. After seeing specialists and undergoing several scans, he was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia or CLL.

Now on ongoing targeted therapy, Stephen shares the details of his CLL diagnosis story to help others go through their own CLL treatment and experience.

- Name: Stephen B.

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- Age at DX: 45 years old

- 1st Symptoms:

- difficulty swallowing

- fatigue

- Treatment

- Rituxan

- Bendamustine

- Targeted therapy BTK inhibitor

- Life Before Cancer

- First Symptoms

- Breaking the news to the family

- Message to others doubting their symptoms

- First oncology appointment

- Managing "scanxiety"

- Processing the news of cancer with the family

- Getting a second opinion

- Undergoing Chemotherapy

- Two years of Rituxan maintenance therapy

- Long-term Treatment

- Follow up Protocol

- Addressing the Relapse

- Having Support and Caregivers

- What felt different: 1st vs 2nd Line Treatment

- Pursuing More Treatment

- Dealing with the Side Effects

- How CLL impacted my life

- Sharing my story through writing

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

1st Symptoms video

Stephen shares his story of his first chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) symptoms.

From being a very fit and active triathlete, Stephen started feeling the first symptoms of what changed his life forever – getting diagnosed with CLL.

Explore his story below and hear about his experience, including some very important messages to the patient-caregiver community.

Life Before Cancer

I am a very multi-faceted guy. I’m 61 years old, a happily married father of two girls, and grandfather of four kids aged 2 to 11.

I reside in suburban Philadelphia, work for a Wells Fargo bank. That’s my professional side.

My passion side has always revolved around multi-sport racing, triathlon, marathoning, multi-sport activities, and things like that, including having been a running coach and a triathlon coach for many years before that.

I come from a soccer background, went to a local college on a soccer scholarship, and then continued to play high-caliber soccer for several years until I discovered the beauty of multi-sport racing and marathon.

Some people would have a real problem with me calling that beautiful because most people look at me and say, ‘Why in God’s name do you do what you do?’

But for me, that’s my passion. That’s fun for me.

First Symptoms

It was late 2005. I was experiencing several symptoms, including fatigue. The most prominent one was a difficulty in swallowing. I was just feeling generally crumbled. But here’s the backstory:

2005 was a horrible year for our family. My father had been hospitalized, had a near-football size tumor removed from his pleural cavity, never made it out of intensive care, and passed away a few months later.

I was registered to race a full distance Iron Man triathlon that July 2005, which I had a whole lot of trouble getting to, but my family insisted that I go to. That was kind of contributing to my overall fatigue.

So when I talked to doctors and describe the fatigue, they asked me what my lifestyle is. And they said, “Well, you just went out for a hundred-mile bike ride. You’re going to feel a little fatigued.”

But to me, I knew something was off. Something was just not quite right.

So like many guys who maybe are not quite as diligent as they should be with keeping up on appointments, as long as they’re feeling okay. Maybe I was not ahead of some blood work the way it should have been. I wasn’t ahead of some preventative appointments and things like that.

First doctor appointments

When it came time to try to figure out why I was having this difficulty swallowing, it took several phone calls to my primary care physician. And we tried chasing the symptoms, not thinking it was anything evil; thinking it was something simple.

We tried antibiotics, steroids, or anti-inflammatories, just trying to figure out what was going on. Finally, none of that work. He referred me to an ear, nose, and throat specialist.

The ENT specialist took a look at my throat. Granted I’m 45 years old at the time, the ear nose, and throat doctor said, “Those tonsils are the worst things I’ve ever seen in my life. We would have gotten them removed yesterday.” Which made sense why I was having difficulty swallowing if I’ve got these two large things in the back of my throat.

I scheduled pre-admission blood work for the surgery for the tonsillectomy. And I got a call that nobody ever wants to get from the surgeon saying, “We came across a little bit of a problem with your blood work. We’d like to refer you to an oncologist before we proceed. Do you have an oncologist?”

I’m looking at the phone and thought, why in God’s name would I have an oncologist? I’m the healthiest person on the planet.

One thing led to the next. My wife was a nurse in a local practice. She knew how to get us to the front of the line of a preferred practice. And then we asked for the first available physician within that practice and met the guy.

I can remember the dates like my own birthday.

I met him for the first time, February 17th, 2006, at which point it was more of a consult. He said, “Let’s review the original blood work, consider some possibilities. And then let’s order every test under the sun to try to figure out what’s happening.”

So from February 17 to February 24, I had everything you could possibly imagine doing. And then February 24, 2006, I received my official diagnosis.

Breaking the news to the family

My wife and I obviously were fully engaged in every conversation with any medical professional.

My initial reaction and what I told my wife was, “These people are crazy. Something’s not right. And it has nothing to do with oncology. Somebody is just not looking at the right chart.”

I was convinced that the diagnosis isn’t right. The patient chart is not right. There’s something that doesn’t add up. It has to be as simple as an infection that they’re missing. Somebody’s missing something.

I guess you can call it denial, but I was convinced that I’m right, and everyone else is wrong and there’s no way this could possibly be oncology. But I agreed to play the game, to check all the boxes and rule everything out, which is why we had the conversations that we had. Thankfully we had the conversations that we had.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

Message to others doubting their symptoms

You know your body more than any other doctor is gonna know your body. You, we, the patient community just need to be fully dialed into what you’re feeling, to any changes in routines, any changes in diet, any weight changes, any changes in anything. You’ll know because you’ll feel it.

One of the first things my oncologist asks me when I check in every three months and we draw blood and I immediately want to know what he’s looking at.

He says, “No, timeout, tell me how you’re feeling.” Because that’s such an important indicator of your overall patient health. So I think it’s really important to pay attention, to listen to your body.

One of the things my oncologist told me was, “As you’re going through treatment, be smart. Listen to your body. If you feel that you can carry on with a run or with a workout, do it. But if you wake up one morning and you’re fatigued, pull the plug, go home, get some rest.”

I think people don’t put enough trust or faith in their interpretation of their own body and their symptoms.

They tend to want to put everything on the shoulders of the medical experts who, yes, can look at the diagnostics, can evaluate you, in some cases, in meeting you for the first time. They’re going to know something, but you’re going to have a lot of the missing information.

You’re going to have a lot of missing pieces and you need to speak up. You need to be that advocate for yourself to say, “Nope, something doesn’t sound right with what you’re saying because it’s not jiving with what I’m feeling.”

CLL Diagnosis

Diving deeper into his story, Stephen shares his insights about patient self-advocacy, and how he managed processing the news of cancer with himself and loved ones.

First oncology appointment

That was a very powerful first meeting with that doctor.

At that first appointment, he ordered for me a CT scan, a PET scan and a bone marrow biopsy, more blood work, and X-ray in the course of a week, and said, “Let’s get you back here this time, next week.”

He was ready for me to walk out but I said, “Hold on, I need to know what are we chasing? What are we ruling out? What’s the game plan here?”

And that’s the very first time I heard the words chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

I knew of leukemia. I knew of lymphoma as blood cancers but I did not know the different types of nuances. I had never heard of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

So that was the first time that I’d heard and explained to me a little bit about what it was. But truthfully, even he, at that stage of the game was saying, “I don’t think that’s what we’re dealing with, but we need to cover all our bases and we need to make sure that we can rule that out.”

I’m getting ready to walk out of the office and my wife says, “Well, maybe we should let the doctor know a little bit about your lifestyle in case he wants to make any limitations or changes.”

I looked at her and told her I don’t want to tell him anything. Because what if he ended up taking something away from me and I don’t want that. But I did and I told them what I do for fun.

I told him that I’m an endurance athlete. I race marathons, triathlons, and Iron Mans, and this is what I do for fun. And this is what I do to feed my soul. And his first reaction was, “It’s probably a good idea to give that stuff arrest for now until we figured this stuff out.”

I was ready to walk right out because I just didn’t think that that was the right approach or the right doc. But we talked through it some more.

That’s when we reached the middle agreement and said, “Again, if you’re feeling fatigued, I don’t want you to do anything. If you’re feeling good, you have some energy, then, go for it. So it was a little bit interesting.”

Navigating the conversation with your doctor

I think it comes down to this: if you are not your advocate, no one’s going to be your advocate.

You have to know what your passions are and you have to know what drives you, what’s important to you. And if someone’s going to say to you, “don’t do any of that anymore while I figure this out,” it needs to be a conversation.

You need to remain true to yourself. You need to remain true to your own spirit and your own soul and figure out.

You should be able to say, “If you’re really telling me this, let’s understand why, and let’s figure out if there’s a middle ground.” And that’s what we ended up doing.

I understood where he’s coming from having. He didn’t know me. He was taking the ultra-conservative route but I’m not an ultra-conservative person. So I said, “Let’s align ourselves here and figure out what we can do.”

Fast forward many years after, at the time he thought I was completely out of my mind because of my lifestyle. But today, he’s a runner and he blames me for that.

Every time I go in for my appointment, one of the first things we talk about is how our runs have been going.

I just think it’s the coolest thing because we’ve both come full circle—I’ve become kind of a CLL expert, he’s become a little bit of an athlete, and that doesn’t happen every day. I think that was a cool exchange of whatever that we had.

Understanding your diagnosis

I made the mistake after that first appointment of going home, opening my laptop, and Googling CLL.

Another key piece of advice to never ever do is don’t just blindly Google your disease because for every one good resource website out there, there are going to be fifteen garbage ones.

That’s going to ultimately steer you down the wrong path and give you some wrong information and can really wreak havoc on your confidence and your psyche.

The first couple of hits that I came up with were memorial pages that were set up by loved ones who lost someone to CLL. That was my first foray into CLL.

So I closed the laptop and thought I was going to die. I walked away. I thought this isn’t going to be good.

After the fact, I said to him, “Can you give me some reputable sources? Can you give me some good links, some good organizations that I can stay connected with, that I can do my own research, my own homework, that I can understand more about my disease?” That’s a key takeaway for everybody.

You have to, you have to learn about it, but you can’t just do it blindly. You need to ask for trusted resources.

Managing “scanxiety”

A test is a test. It’s not always the be-all, end-all to anything.

You need to have those scans and tests to help paint the picture. It contributes to the information. It helps with the ultimate decision-making. It’s really important that they get evaluated appropriately, and properly by the right people, and discussions are had around those two.

In other words, if your PET scan showed this, let’s talk about that a little bit more. Feel free to say, “Tell me what you saw in that scan that was frightening or concerning, and what are some other possible things that might present that same type of concern.”

I also understand that at that point, I still thought everyone else was crazy. So I was just going through the motions, satisfying everyone else. And I thought at the end of the day, I would come back with getting an apology from everyone and say, “Oh my gosh, we’re so sorry to alarm you. Take two of these and you’ll be fine in a month.”

But that wasn’t the case. I think the big thing for me was having to take it in stride. You can’t overreact to any single test.

It’s just one piece of the puzzle. And it’s a puzzle that might have several different ways of coming together. You just need to maintain a sense of being open, a sense of positivity and a sense of hope.

Processing the news of cancer with the family

Dr. Shore had all the results right there in front of them. He ran through the different results saying conclusively, everything confirmed the same thing. That hunch that we had from the elevated white count from the ear, nose, and throat tonsillectomy guy—everything else painted a similar picture.

That’s when he said, “There’s little doubt that I was looking at anything other than chronic lymphocytic leukemia. This presents itself as a classic case of CLL for a number of reasons.”

And he talked about the size of the lymph nodes, the white count. Little did I know that I felt the tonsils, but the rest of my lymphatic system, like my spleen, was enlarged. All my unseen lymph nodes were also oversized. And my white count was up around 70 or 80,000.

It was what it was. You listen, you hear the plan, you hear the protocol.

And he said I’m welcome to talk to any number of other people, which I did. But I also didn’t want to waste time. So I moved ahead with his plan of treatment, at least, getting that stuff scheduled.

I then quickly ran home, reached out to some other folks, to a doc in the University of Pennsylvania, to another doc I knew and I was close friends with within the multi-sport triathlon world.

I sent them my results, talked about protocols, and standard care for CLL. Without even seeing them, I kind of rallied my team that way. And they were all on board with a diagnosis and the plan of attack.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

Getting a second opinion

It’s hard to just give examples of when it might be warranted and when it might not be. But I would say, in most cases, it definitely warrants a second opinion.

As much as I love my doctor, he’s human. And I was meeting him for the first time. So there are good auto mechanics and there are bad auto mechanics.

There are physicians who might be really good at diagnosing this kind of thing. And there might be guys who are not. So it was critical that I had a conversation with multiple physicians

If the doctor has your best interest, first and foremost, and if the doctor is what he should be, he would embrace that. He would welcome that.

In fact, he would even help facilitate that and will potentially give you some names and some contacts for you to reach out to have that second opinion.

And if he’s really good, he’s not only going to help facilitate the conversation, you will allow those two physicians to get on the same page. And if it’s a matter of hashing something out medically, they will do that.

I had that happen personally. If my primary guy needs to recommend or refer something, he’ll say to me, “I don’t want him to do that until we talked to Dr. Porter who was in a totally different network but is very much an expert in this field. They would often bounce ideas off of one another in terms of my treatment and care.

1st Line Treatment

With a positive outlook, and by taking it moment by moment, Stephen was able to get through longer-term treatment, including two years of rituxan.

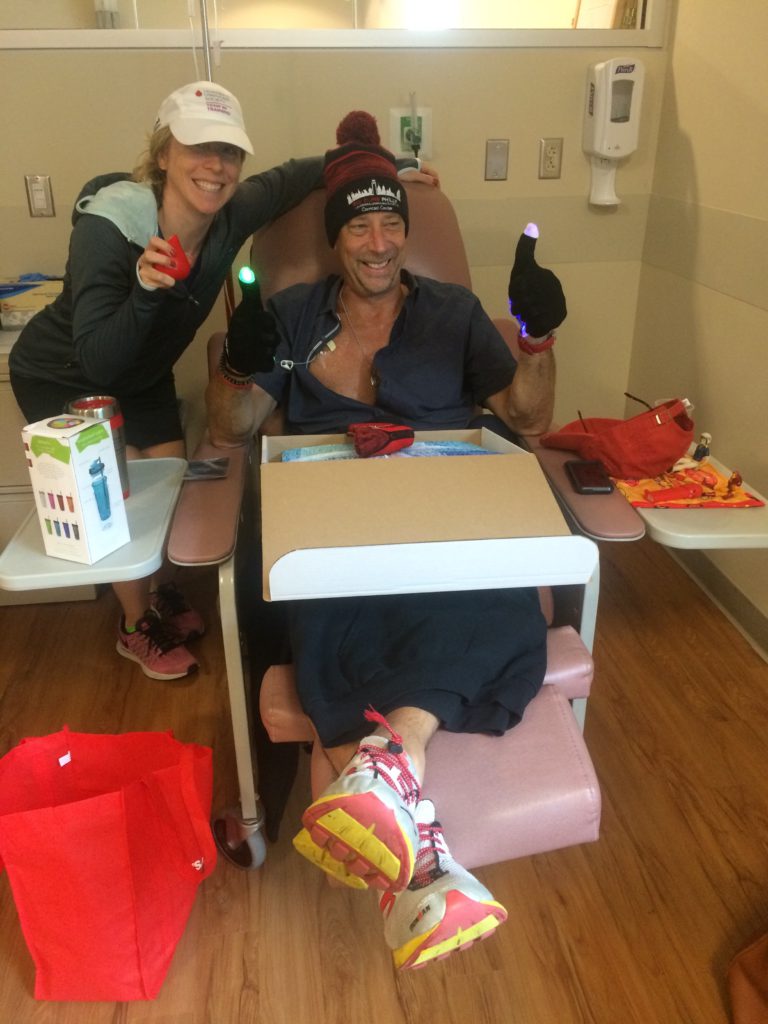

Undergoing Chemotherapy

What I learned was it’s a very cyclical process. And it builds a cumulative effect on your body.

I remember the first couple of days of treatment walking away thinking nothing. In fact, I felt so good early on in the first couple of days of each cycle that I would run home for my chemotherapy treatments.

And I did it for a number of reasons. It made me feel good. It made me feel physically and mentally good. I thought it showed my loved ones that I must be okay if I’m still doing the things that I love to do.

But as the week wore on and the toxins accumulated in my body, by that Thursday/Friday, I was pretty beat up. All it took was one cycle to realize that Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday are kind of scratch days; Thursday, Friday, I’m out. The weekends not great, but up by Monday, the following week, I’m not bad again.

So once I was able to digest that fact and I knew what was probably to be expected and I can predict and plan on that, I was able to do that.

I didn’t overthink the days. I felt bad because I knew I was going to rebound and I knew that it was cyclical.

And I also knew that they do such a great job of pre-treating with a number of different cocktails, supplements, and other things to help offset anything that you might be experiencing.

I think people have this image of a chemo suite as this dark dungeon of hell but I had the exact opposite experience. It was upbeat. It was positive.

The oncology nurses that I worked with were saints. They did everything humanly possible to keep my spirits up, to keep me feeling good physically, to make sure I didn’t need something to drink or eat.

It made all the difference in the world. I just had a pretty positive experience throughout the whole thing. I had my moments, but for the most part, it was good.

»MORE: Read other cancer patient experiences with chemotherapy

Two years of Rituxan maintenance therapy

I knew about that. And truthfully, the idea was a little daunting for me in the beginning.

I could wrap my head around the initial four rounds of treatment. That seemed moderately tolerable for me to comprehend. But when I thought of two years of follow-up every six months, getting five more doses of toxin, that set me back a little bit.

That took some time to wrap my head around. But at the same time, I didn’t need to think about it until six months after I was done that last round.

I didn’t overthink it until it was time to go back in.

Truthfully, by that time, I felt great again. I was hundred percent of my own self again. I understood what the Rituxan was going to do and how I was going to respond and how my body would cycle through it. So I became okay with it.

You just have to be patient and just work through it and you’ll get there. You get through it.

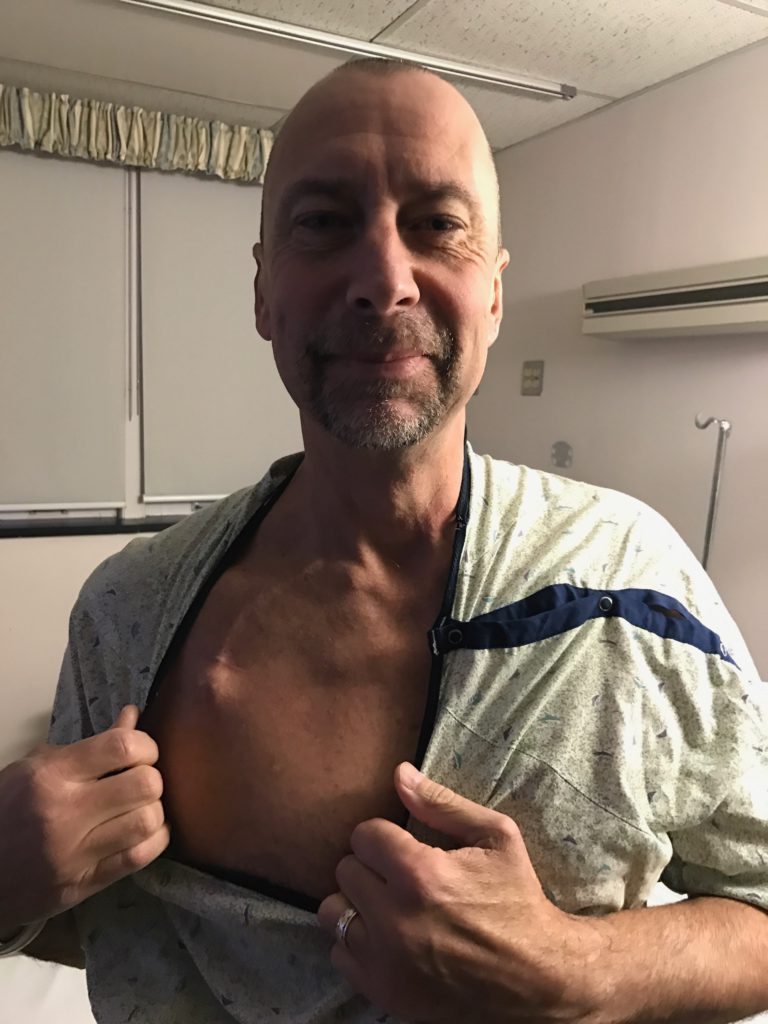

The smiles on some of my pictures are not anomalies. That is pretty much the approach I tried to take throughout any treatment when I was in the chemo suite.

In fact, if the nurses didn’t see me smiling or making a joke about something, or if they saw a serious look on my face, they’d come over and they’d want to know what’s wrong.

That became an indicator that I might be tanking because I’m being serious. I tried to be as upbeat as I could throughout.

Long-term Treatment

He didn’t put a timeline on it, but he did say that this is going to buy us a whole lot of time.

If we’re really lucky, it’s going to buy us a whole lot of time, but it’s not going to buy us forever.

It’s a chronic condition that it’s incurable. There’s no known fix for it today. So at some point, we’re going to have to revisit it. But the hope and the goal were to be as definitive as we can with the initial sweep of therapy to really knock it way back, down, and off the radar as far as possible so that we don’t have to have this conversation again in the near future.

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

CLL Relapse

While staying focused and positive, and with the support of his family, Stephen confronts relapse and moves on from one treatment to another.

Follow up Protocol

Visits to Oncologist

I see my oncologist every three months for the last 15 years, as long as things were okay. But anytime there was, at least, a little bit of a hiccup, it could be a month. It could be six weeks when he’d say, “I want to check your blood again in one month, come back.”

Three months is what we hope for. It’s never any longer than that. I think every once in a while, I’ll bargain for four months.

He’ll joke with me when I leave. When he asks when do I want to come back, I’ll say, six months. And he’ll say, “Okay, I’ll see you in three.” It’s not a negotiation but he says it anyway.

Second Line Treatment

Steroids (dexamethasone or prednisone) were always the go-to bandaid when things would start to escalate a little bit. But not to the point of needing a full-blown treatment.

If the white count is elevated, or the lymph nodes are starting to flare up again, I’d take that. If we got some swelling, we’d do an MRI, and if we’re seeing some things but not worth going through putting the body through the full treatment, we’ll try to get a handle on it with some high doses of prednisone, or Decadron, on the interim basis.

And hopefully, that’ll knock it off the grid or, or just see how we do from there. I’ve been through several rounds of both of those drugs over time.

And I’ve developed a love-hate relationship with both of them; probably hate Decadron and love prednisone more, but that’s just me. The love-hate part is where I totally recognize the benefit and I see how well it works.

When I’m on Decadron for a couple of days, I’m awake throughout the night with enough energy to build a house. And then at some point during the day, I start to bunk and I don’t know what to do with myself. And then I’ll crash and I’m all mixed up. My cycles are mixed up. I get a little cranky.

They all come with a price tag. But they work tremendously well. So you have to just accept the whole package. If you’re going to accept the treatment, you need to accept what comes along with it.

Dealing with Steroids

Stick with “eating chocolate.” And by that, I mean those things in life that make you feel really good and make your eyes roll and back your head, and you say that’s delicious.

Whatever that is for you, if it’s needlepoint, gardening, birdwatching, or running marathons, if you can keep up some level of something that makes you feel really good about yourself, that’s going to help offset any kind of emotional stress that any of this stuff is putting on you.

As far as the physical stuff goes, again, it’s a cycle. You’re going to stay awake.

One thing I learned very early on in my triathlon and marathon-running days is that you’re probably not going to sleep very well the night before a race.

It’s just a given. So stop putting pressure on yourself that you need to fall asleep immediately. You’re going to stare at the ceiling and you’re going to toss and turn.

It’s the same thing on Decadron. I’m not going to sleep tonight so I’m going to rest, have my feet up, and just relax. I will read and put on some relaxing music. I will do something that will help level me out, even if I don’t sleep soundly.

That’s typically the kind of rest that will, at least, get you through for a little while anyway.

Getting Through It for the Long-Term

It sounds like a negative thing that one has to get over. How about we flip it and say, “I’m fortunate enough to be tightly tethered to my oncologist that every three months I know the state of my health. Not everybody walking the planet can say that.”

That’s how I chose to view that. I’m safe. And if the doctor were to say to me that I should just come back next year, I would say, “Wait, what? No, I need to see you sooner than that because I need you to tell me that I’m okay.”

Addressing the Relapse

Symptoms started to reappear. Same types of problems—difficulty swallowing, swollen lymph nodes.

This time I was experiencing some night sweats, and other classic symptoms.

But he just didn’t want to venture down the same path because he felt like we had already gotten our money’s worth out of that previous treatment. There were so many other really good things in the pipeline and already in-flight that he wanted to venture down that road.

So he was the first person to bring up Bendeka.

Every appointment, we will talk about what’s in the pipeline. Like, “Have you heard about the next generation of this drug?” So I have a little bit of an understanding of some of the things that are coming.

When he said Bendeka is probably the next logical path, I had full faith in him at this point and I was willing to take the leap with him.

»MORE: Read more relapsed/refractory cancer stories

Undergoing Bendamustine Port Chemo

It wasn’t even a full year that I was on Bendeka. It was four-weekly cycles. We didn’t even get all the way through the fourth because my blood work overall had plummeted after about three and a half. So we ended up not finishing that fourth.

But I think in many cases that the fourth cycle is at the oncologist’s discretion. Based on what are the results, how the patient’s feeling, what we are seeing. And he had seen enough.

The results were pretty definitive that we’re getting the response we need. He said, “There’s no need to put you through this for another few sessions. Let’s just pull the plug now.”

I kept the port in for a couple of months while we made sure that it was gonna remain at bay, which it did for a few months. And then I was the first one to say, “Can we please take this thing out?” Because I was conscientious about it.

It doesn’t look exceptionally big, but you know, it’s there and it doesn’t belong there. It just made me feel kind of awkward.

»MORE: Read other cancer patient experiences with chemotherapy

My Chemo Port Story

I was on the operating table, having it removed. The same doctor who put it in took it out.

At the time I felt, “Hey, this little device that’s inside me was very powerful. It delivered what it needed to deliver and helped put me in a good place.” So I was in a mild twilight for this procedure. Just local anesthesia or some numbing on my chest.

As the doctor’s getting ready to go in, I said, “I have a favor. Can I have that when you take it out?” And he said, “What? You want your dirty port from inside your body?”

And I said, “I want to take it home and put it in my trophy cabinet. And he said, “There are strict hospital policies about that.”

The next thing I know, as he’s finishing up, I hear him turn to one of the nurses in the room and said, “Would you please take this thing, go clean it up over there, put it in this vial, slide it under his sheet.” And he mums the word.

I have my port in my cabinet. I just thought there was another chapter of the story. When I can do little crazy things like that, it makes me feel as though I’m one step ahead of the disease, because I’m almost mocking it.

Having Support and Caregivers

It was critical. For me, it was important that I had loved ones nearby.

You might not get the same answer from everybody because some people just prefer to live this more privately. I’m not advocating anyone to go through it in a complete vacuum, a hundred percent by themselves.

But I’m one end of the spectrum.

I was very public about this. And I continued to be very public about it. I will climb to the highest mountain and preach about what I went through, how I did it, how we can advocate together, and how I can help others.

But then there are some people who will say, “Look, I just want to show up, get my treatment, go home, not talk about it.” And you have to be respectful of that, too.

I don’t think there’s any standard formula for how this all has to work. But I think it’s really important that everyone at least has someone that they can talk to.

Maybe it’s family, maybe it’s a professional. Maybe it’s a faceless person through one of the organizations that partner patients and mentors because then they become faceless and they can offer some advice and some help in that respect.

But again, everybody needs somebody, but to varying levels. No two people are on the same level.

»MORE: Join other patients and caregivers on The Patient Story social media community

What felt different: 1st vs 2nd Line Treatment

It felt different only that it was a different method.

I just feel like it was a different chapter of the story.

I don’t think my body necessarily felt any difference or responded differently. Maybe the whole routine became different, but I just thought that was part of the evolution of treatment.

This Bendeka wasn’t an option when I was diagnosed, then it was, so we moved on to that. And then at some point, we move onto the next thing and the time is right.

Targeted Therapy

Learning to value the here and now, Stephen lends his experiences and insights to getting ahead of his cancer, saying yes to a newer treatment, how he managed the side effects, and why he finds it so important to use his voice to help others.

Pursuing More Treatment

Even though I was living my thing, feeling good and all systems were normal and go again, I was still having those appointments every three months just to confirm that I’m okay. I needed it.

But my doctor and I have always had those conversations—about what’s next. Even if the topic of conversation isn’t, we would.

We’re going to have the conversation anyway because that’s just the way it is. That’s the nature of the beast with a disease like this.

My doctor said, “I’ve got several people or a lot of people on this. The practice has had great luck with it. I think if and when the time is right, that’s probably going to be what’s next for you. But I have to warn you, it’s a little pricey. So we’re going to have to work through all that if and when the time comes.”

That’s how we framed it for me. But it wasn’t until several months, a year, or maybe even longer before he said, “I think it’s time because symptoms have come back. CT scan revealed more lymph node movement from the prior and white count was on the climb.”

I look at it like this: you keep going to the same restaurant. And every time you go in there, there’s a new menu, which is pretty cool. It keeps things fresh and you’re not going to get sick of the same food because you’re looking at something different every time you go in there.

That’s been the options whenever I walk into the oncology office and I need treatment. Like, “What is the special of the day?”

And by day, I mean, what’s the protocol for this period of time? And at this time it was Imbruvica. That was the hot drug. And we took a shot at it.

It was probably the best thing we’ve ever done.

»MORE: Read more about ibrutinib and other patient experiences

Saying ‘yes’ to a new treatment

Going into it, at the back of my head, I’m thinking, I don’t know what this is going to feel like.

I read the potential side effects. As with any medication, like when you watch a TV, any ad that you see on TV, you’d hear the disclaimers and you think, “Oh my God, I’m never going to take that! The side effects are going to kill me before whatever I’m being treated for kills me.”

I was a little concerned about some of the side effects that I have read about but they were the standard cookie-cutter type.

But I experienced basically none of them and I was extremely happy about it. I was able to maintain my lifestyle and keep going with what I was doing. It was literally a good call.

There was literally one small pill taken once in the morning. There was only one other supplemental drug I would take with it called Allopurinol. And all that does is help the body rid some of the toxins that accumulate, similarly to a patient with gout or with some other disease where they need to rid the system of that stuff.

Now it’s three years in and it’s just been a very positive experience.

I filled the prescription right there in my oncologist’s office. I can run down to pick it up and run back home again, which gives the ultimate feeling of empowerment.

Okay, yeah, maybe I have leukemia. Maybe I had to go pick up my targeted therapy drug, but you know what, I’m kicking its butt because now I’m running home from picking out my drug. And now I’m just going to settle back into my lifestyle.

More Treatments on the Horizon

His hunch was by the time we need to have that conversation for real, whatever we talk about now, it’s going to be yesterday’s news. There’s going to be something else that’s more relevant.

I’ve done a lot of work aligned with leukemia and lymphoma society. So I see a lot of those announcements of things that have been passed and funding that has taken place.

I thank God every day that I am where I am at this point because there have been so many options available. Maybe you don’t have the solution that you need today but you’re going to have your solution.

Every day that I’m not being treated or every day I’m in remission and not in need or not in a dire situation is me winning.

Six months, a year, or two years from now, you might have to go back into that same restaurant. But when you open that menu, you’ll be like, “oh my God, where all this stuff comes from?”

And that’s just going to be the way it is.

Things continue to evolve. Things get perfected. Research gets better. Funding gets better. Solutions get better. It’s an okay time to have blood cancer from my perspective.

»MORE: Read more patient experiences with targeted therapy

Accessing New Targeted Therapy Drugs

When my doctor and I first started talking about Imbruvica, he did mention to me that it can be costly. But I was fortunate that the stars aligned in that by the time I really needed it.

It had become more mainstream. Insurances started to pick it up and it became the perfect storm for me. Essentially, it was fully covered by my insurance program.

But I also learned that if you’re on any kind of high-end, very expensive medication, many of the manufacturers themselves have different co-pay programs.

Typically, you’re not eligible if you’re on any kind of Medicaid or Medicare insurance. But if you’re on conventional insurance, whether it be subsidized through your work or private pay, there are organizations that facilitate these programs.

You have to apply for it and meet certain criteria, but essentially you can be qualified for a copay plan of your medication, which I didn’t know existed.

I actually signed up for that with the urging of the team at my doctor’s office. They’re the ones who made me aware of it. They said, “We’re going to sign you up for this. And then we’re just going to wait and see, who’s going to offer the best coverage.”

We actually used that to now with my wife on a different medication. They’re offering the same thing but not oncology-related. Just search co-pay for that drug, and you will ultimately find it.

Dealing with the Side Effects

Don’t overthink what you read and communicate what’s real.

They have to give you a warning of what might happen. But that’s for a fractionally small amount of time in a very small population of patients. They just have to go on record. They have to document and publish them.

My doc said, “If you start feeling anything that makes you feel uncomfortable, come back to me and we’ll talk about it. We’ll figure out if it is temporary, long-term, or a showstopper. Is whatever you’re experiencing bad enough to pull the plug on this? Isn’t it worth it?” Because that possibility exists with anything.”

I think people are afraid to take a chance on a drug for fear of what might be without ever giving it a shot. What matters is how are you personally going to respond.

Again, no two patients are going to respond the same to any of this stuff. So give it a shot and see what happens. You can always redirect, go a different direction and call it off and then try something different.

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

How CLL impacted my life

I think it has changed me and it hasn’t changed me.

How it hasn’t changed me is that I’ve been able to do exactly what we’re looking at right now. I’ve been able to continue with my lifestyle and continue doing the things that I love doing.

How it has changed me is looking at me crossing that finish line. And I cherish that just a little bit more.

I know and value the here and now.

I treasure the time spent with my wife, kids and grandkids. And I look at things through a happier lens. And I’ve always been optimistic, but this forces me to live it a little bit more.

It’s hard to explain but I felt ever more grateful for the little things in life. Whereas before, I would often think that I’ve got tomorrow, the next day or the next month.

I still have that. But the brutal reality is that we’re all mortal.

We’re never sure how many tomorrows, next month, or next year that we have. So it’s important that you really take care of the things you need to take care of in your here and now so that you can appreciate them. Then you can really just live in love at the moment.

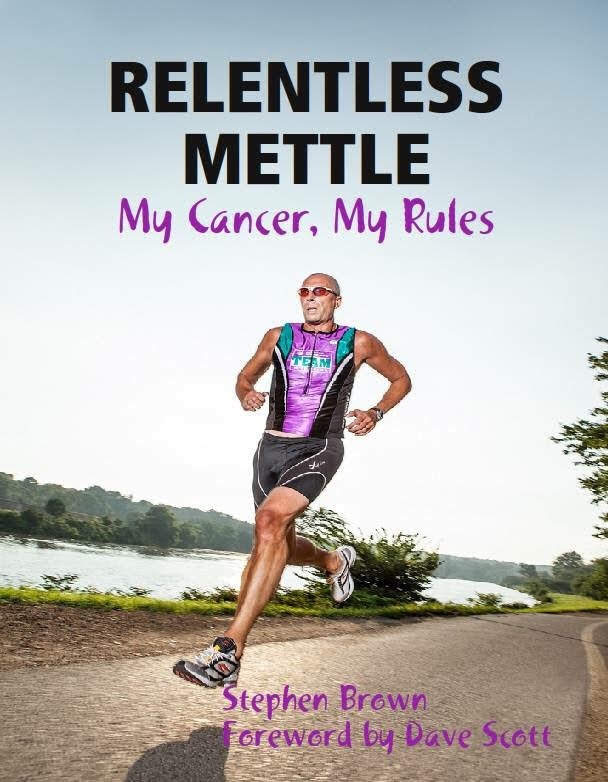

Sharing my story through writing

I never set out with the intention of needing to write a book. What I set out with was needing a way to get the thoughts out of my head and out of my heart.

I needed to find a way to purge some things and keep myself fluid in what I was doing.

A lot of what you’re reading started as blog posts, where I would chronicle my day in treatment, or I would start with the beginning of my journey. And then I’ll throw in a random thought or a short story about something.

It was really just more for my benefit than anything. To get things out of my head and keep it as a creative outlet for me.

What I learned in the process was it helped a whole lot of other people because those who read it have really positive things to say. And I think it’s helped more people than I ever would have imagined possible.

That was never the goal. That was never my point.

In terms of advice or suggestions, this book fits into that category of “don’t let go of the things that make you feel good.”

In some cases, for me, that’s running, hopping on a bike and working out. But it’s also being reflective.

It’s putting your thoughts down on paper, or putting on headphones and getting lost on your favorite album or whatever it might be. It helped me as much as it has helped others. And I am proud of it.

I mean, it’s a thing. I’ve got a few of them sitting in the bookcase.

I don’t expect everyone to go out and write a book. Some people might not want to talk to an actual person, but some people might be very good at writing their own thoughts down. So that might be their own support.

Maybe they go home after a tough day of chemo and they just want to chronicle their thoughts. Maybe when they first sit down, they’re feeling overwhelmed. But when they get done writing for a half-hour or an hour, they would feel a little lighter and better. And that was part of the process for me.

Finding my voice

I look at myself as a people-broker in life in general. There’s so many people out there doing all kinds of different things, and there’s so many commonalities in what they do. And sometimes it’s hard to put all the pieces together and to figure out who’s connected to whom.

That’s another reason why I put myself out there and that makes the oncology patient-caregiver community much stronger. What has happened by me doing that and by you (Stephanie) doing that is why we are having this conversation right now. You’re going to post this and it’s going to reach many people.

I won’t say it’s our obligation, but I think, it’s a real added benefit that we are able to improve the landscape just by living our life and story, which is pretty cool.

Inspired by Stephen's story?

Share your story, too!

Other CLL Patient Stories

Lynn S., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

Symptom: Elevated white blood cell count

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy (BTK inhibitor)

Serena V., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

Symptoms: Night sweats, extreme fatigue, severe leg cramps, ovarian cramps, appearance of knots on body, hormonal acne

Treatment: Surgery (lymphadenectomy)

Margie H., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Symptoms: Large lymph node in her neck, fatigue as the disease progressed

Treatment: Targeted therapy

Nicole B., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Symptoms: Extreme fatigue, night sweats, lumps on neck, rash, shortness of breath

Treatments: BCL-2 inhibitor, monoclonal antibody