The Latest in Myelofibrosis Treatments

What Clinical Trials are Available to Me?

Edited by:

Katrina Villareal

Myelofibrosis experts Dr. John Mascarenhas (Mount Sinai) and Dr. Tania Jain (Johns Hopkins Medicine), and Clinical Trial Nurse Ashley Giacobbi (The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society) explain cutting-edge therapies. Hosted by The Patient Story Founder Stephanie Chuang and featuring insights from patient advocate Mary Linde, this empowering discussion will help you navigate all aspects of clinical trials.

The myelofibrosis panelists discuss momelotinib, navtemadlin, selinexor, pelabresib, navitoclax, imetelstat, and other myelofibrosis treatments.

Done in partnership with our friends at The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

- Introduction

- Mary’s myelofibrosis diagnosis

- What is myelofibrosis?

- Landscape shifts in myelofibrosis treatments

- How JAK inhibitors work

- Determining the sequence of treatment

- What are clinical trials?

- Momelotinib, a new drug

- Best drug combination therapies

- When to consider combination therapy

- Second-line treatment after Jakafi

- When to get a second opinion

- How to look for myelofibrosis clinical trials

- The role of stem cell transplant

- Final takeaways

- Conclusion

Introduction

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, everyone! Welcome to the program hosted by The Patient Story and The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

I had a different blood cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and I went through treatment a few years ago, but I’m so passionate about these discussions. So many things are happening in the landscape of changing treatment options and they start with clinical trials.

We hear about clinical trials but the term is so daunting and overwhelming. Our goal is for you to have a much better understanding of what they are in human terms. Maybe some might be right for you that you can ask your own doctors about.

The Patient Story features hundreds of in-depth, authentic patient stories across cancers and we also feature top cancer specialists. Our goal is to humanize cancer and help you navigate life after a diagnosis, whether you’re a patient or a caregiver. You can join our community and you’ll get first access to programs like these with new updates and new stories.

We’re so proud to be co-hosting this with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. It is the world’s largest nonprofit health organization dedicated to funding blood cancer research as well as offering patient services and education.

They have great resources if you haven’t checked them out yet. Their information specialists are just a phone call away to help you answer some cancer questions. They also offer help to pay for cancer costs through a co-pay assistance program, like travel to CAR T-cell therapy or clinical trials.

We want to stress that The Patient Story and The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society retain full editorial control over the entire program.

This is not medical advice and not meant to be a substitute so please make sure to talk to your own healthcare team when you’re making any decisions.

We have incredible panelists for this discussion.

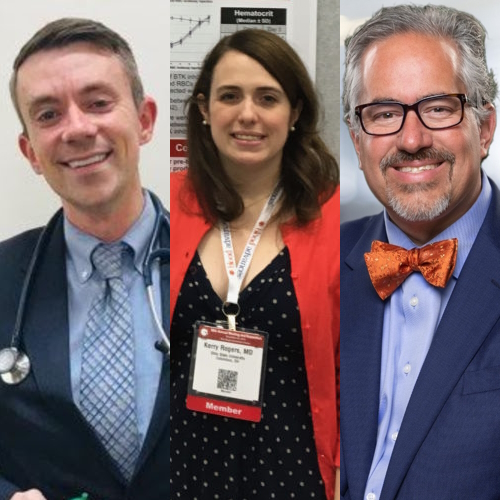

Dr. John Mascarenhas

Stephanie: First up, really lucky to have Dr. John Mascarenhas, professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, director of the Center of Excellence for Blood Cancers and Myeloid Disorders, director of the Adult Leukemia Program, and also leads clinical investigation within the Myeloproliferative Disorders Program.

Dr. Mascarenhas, really appreciate you being here. I heard you describe yourself as being tireless and working nights and weekends to help patients in this space. We really want to understand what drew you to MPNs and to continue to do this work for patients.

Dr. John Mascarenhas: Thanks for having me join you. My interest began in the laboratory doing leukemia research many years ago. It evolved over time into clinical research in which I was introduced to MPNs and I really gravitated towards it. This was at a point where we didn’t have JAK inhibitors.

I was at the right time when the discovery of the JAK2 mutation came out. I got involved in the early development of JAK inhibitors and watched the field blow up. It’s been really exciting and rewarding to see this transition from how we used to treat patients with myelofibrosis and other related MPNs to what it looks like today so I’m very enthusiastic and optimistic about the future.

Stephanie: Thank you, Dr. Mascarenhas. We know that the landscape has shifted very quickly in a short amount of time. Excited to talk about it.

Dr. Tanya Jain

Stephanie: We’re also really excited to have Dr. Tanya Jain here tonight, another MPN specialist. She is an assistant professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins Medicine and director of the Adult CAR-T Cell Therapy Program at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center with myeloproliferative disorders as a top area of interest and studying newer drugs in the early phase of development.

Dr. Jain, thank you for joining our discussion. We’d also love to understand what drew you to the MPN space. What’s the driver of doing this work for patients and their families?

Dr. Tania Jain: Thank you so much for having me. I’m absolutely delighted to be a part of this panel.

I don’t think it was a specific event. It was a natural transition during my fellowship under the mentorship of Dr. Ruben Mesa and Dr. Jeanne Palmer, who’ve obviously done a lot of work and continue to do so.

How that transitioned me was to recognize the significant unmet need in the space and the opportunity that existed to contribute to improve outcomes for patients and to improve the lives of patients and their families so that’s what we try to do.

Stephanie: Thank you so much. That means a lot for all of us who’ve gone through cancer.

Ashley Giacobbi

Stephanie: Speaking of incredible work, we have Ashley Giacobbi representing The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s Clinical Trial Support Center. It’s a really great resource because as we know, clinical trials can be very daunting and seem like a lot to wade through.

Ashley, thank you for being here. I have such a special place in my heart for nurses. I remember going through my treatment and nurses being such a lifeline so I really appreciate the work that you do. We’d love to understand more about yourself and what drew you to this calling.

Ashley Giacobbi: Thank you so much. I’m really honored to be here.

I have been a nurse for almost 20 years now and have enjoyed all of my time at the bedside.

I get extra excited when talking about new changes and how much has changed in the world of oncology over the last 20 years. It’s exciting to be able to help patients find clinical trials when they’re seeking the newest and next level of care and some of these new developments and advancements that we’ve had.

Stephanie: Thank you, Ashley. We’ll be talking about some of the top topics you’re getting from patients and care partners who are calling you and asking for your help in the clinical trial space.

Mary Linde

Stephanie: Finally, we’ve got Mary Linde, who I’m really blessed to be able to call a friend now. Mary, you’re a myelofibrosis patient advocate. You lead a group on Facebook with myelofibrosis patients and care partners. We’re so lucky to have you share your perspective as well. Can you describe yourself a little bit outside of cancer? As we know, we are so much more than a diagnosis.

Mary Linde: Thank you for that. I’m almost 61 years old. I’m a nurse as well and have both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in nursing. I stopped clinical nursing for 25 years.

I’m currently the CEO of a small nonprofit foundation that mostly runs a retirement community here in San Francisco. I have always had a heart to serve the elderly.

I’m a mom to two amazing adult sons who are launched and living on their own. One is married and one is about to get married. I’m really hoping for grandchildren soon and to live long enough to really enjoy those grandchildren.

I have a three-year-old Coton de Tulear puppy who gets me out and moving. I walk 3 or 4 miles a day with him.

Mary’s myelofibrosis diagnosis

Stephanie: Like so many of us experience, a diagnosis changes our lives. What led you to figure out that something wasn’t right and how did you get your primary myelofibrosis diagnosis?

Mary: It wasn’t easy. I was about 54 1/2 when I started with vague symptoms. I had fatigue, dizziness, and sometimes vertigo to the tune of whoosh and then I fell. I felt like I needed to nap more frequently. I felt like if I walked up any incline, I needed to rest.

I knew something was wrong. I thought I had mono or Lyme disease. I kept complaining to my primary physician about these symptoms. He kept telling me I had menopause, which had long been through at that point.

I would repeatedly go back to my primary physician and say, “Please, let’s investigate what this is,” and even told him that my father had a rare blood cancer at around this same age.

Finally, six months into begging, I reached out my arm to the doctor and said, “I’m not leaving your office till you do a chem 7 and a CBC,” and he did.

Three days later, I got the results that I had platelets in the 800,000. Of course, Google became my friend. I called the doctor and he refused to talk to me. He said, “I’m sending your blood off for special testing. I don’t want to tell you because I don’t want to scare you.”

I started Googling and I was pretty certain I had an MPN. Three months later, I found out that I had the JAK2 mutation. I didn’t find out from my primary care physician; I found out when I got a call from the oncology center admitting me to services.

When I walked into the oncology center, I had a very strange experience. The introductory oncologist said to me, “I know you’re probably really afraid of the C-word so we’re not going to talk about it. Let’s talk about it like a blood disease.” I told her that I was a nurse so she didn’t have to do this. Then she said, “The other C word is an evil drug so we’re not going to talk about that either.”

I kindly asked her to get me another doctor and then sought a second opinion. At that time, I wasn’t so afraid of dying as much as I was afraid of not having the information I needed to live well. I didn’t know if my life was going to be shortened and I wanted as much information as I could get.

Stephanie: I really appreciate you sharing all that, Mary. I also love the message of self-advocacy and empowerment. It’s your life, you know your body, and you certainly didn’t let that fall through the cracks.

What is myelofibrosis?

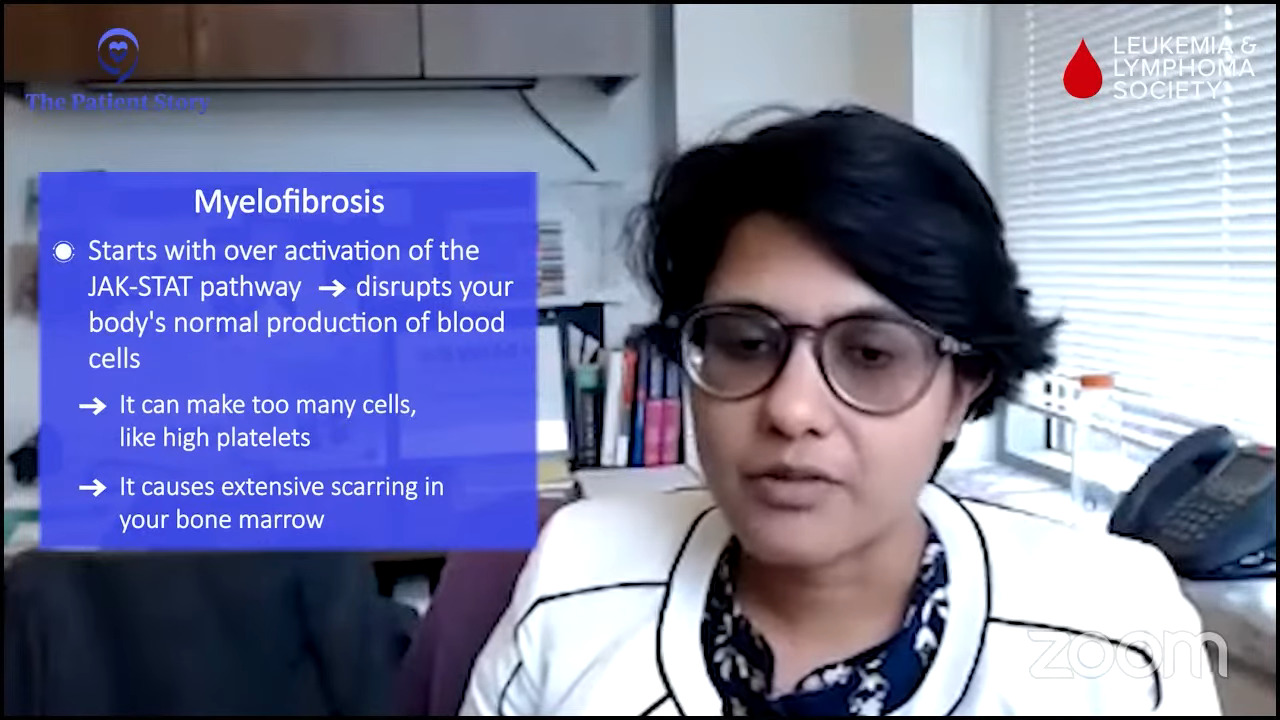

Stephanie: Dr. Jain, what is myelofibrosis in layman’s terms? What are some of the more common first signs or symptoms?

Dr. Jain: What we heard from Mary’s story is something that I hear in the clinic fairly commonly. Having that fatigue and tiredness is something that often takes people to physicians to get tested. Delays are not uncommon either because fatigue or tiredness have several possible reasons. Some may be more common than others.

Mary also mentioned the JAK2 mutation, which is of relevance here. The premise of myelofibrosis starts with the overactivation of the JAK/STAT pathway, which is supposed to be a normal functional pathway that’s supposed to do regular stuff and make blood cells.

When it’s over-activated or activated without any restrictions, that’s when undesirable things happen, which can include affecting the bone marrow function in a negative way.

You could be making too many cells or you could alter the bone marrow function in the way that there is more scarring in the bone marrow, which is the fibrosis in the term myelofibrosis, which again affects the ability of the bone marrow to function normally whose job is to make a normal quantity and quality of blood cells.

As a result, patients can get anemic or have low hemoglobin, which can cause tiredness, fatigue, difficulty breathing, and related symptoms.

By virtue of the JAK/STAT pathway activation, this systemic or generalized inflammation that we often notice or patients leads them to a workup. What that results in is what we in our clinic call constitutional symptoms or symptoms that could be nonspecific or vague as sometimes labeled.

Those can include things like night sweats, low appetite, or other symptoms resulting from an enlarged spleen like abdominal discomfort, which are other symptoms that can sometimes lead to further investigations clinically.

Stephanie: Thank you. I know that’s a lot to cover in a short amount of time. We do hear lots of stories about how long it can take to figure out a myelofibrosis diagnosis so that’s not unique to Mary’s situation.

Landscape shifts in myelofibrosis treatments

Stephanie: Dr. Mascarenhas, you alluded to how optimistic you are because there are so many developments happening. How would you describe the landscape shifts that have happened in myelofibrosis treatments, especially in just the last few years?

Dr. Mascarenhas: Myelofibrosis is a stem cell-derived blood cancer and it could affect people in different ways. You don’t meet two people that walk the same path. They all come in different forms and fashions. Their clinical picture can be really varied and their course can be quite heterogeneous and variable, too. You have to understand the patient that you’re dealing with and the patient-specific goals of therapy.

For some patients, it could be alleviation of anemia. For other patients, it could be systemic symptoms like fevers, night sweats, weight loss, bone pain, and profound fatigue that can be quite debilitating. For many patients, it can be an enlarged spleen or liver that’s causing a lot of discomfort and challenging normal activities like bending over and doing things that would be normally easy to do.

Knowing how the disease is affecting the patient really informs and dictates how best to approach the patient. It’s typically trying to alleviate the symptomatology and reduce the spleen, and that’s usually using JAK inhibitors.

JAK inhibitors

Dr. Mascarenhas: Over the years, we’ve grown to have three clinically or commercially available JAK inhibitors: ruxolitinib since 2011, fedratinib since 2019, and pacritinib since 2022. And a fourth one, momelotinib, later in 2023.

This provides a lot of opportunities to try to address those symptoms. Those cytokine-driven symptoms that Dr. Jain explained are a result of this JAK/STAT pathway. These drugs are great in reducing a lot of that inflammatory cue that makes patients feel terrible, improving their sense of well-being and functionality, and reducing their spleen.

In doing so, patients have a better quality of life and, by virtue in most cases, will live longer because they can do the simple things that we need to do. They can move and eat. People who move and eat will simply live longer and do better than patients who cannot and that’s just generally true in oncology.

They have really revolutionized the quality of life aspect. As Dr. Jain pointed out, she worked with Dr. Mesa who was really instrumental in measuring quality of life and making that an endpoint for clinical trials and bringing attention to symptomatology and quality of life.

We have a great armamentarium that covers lots of different types of patients to improve their symptoms and quality of life.

We are developing drugs that are looking to try to improve anemia. Historically, we use drugs like epoetin alfa or darbepoetin alfa, which are erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, to try to improve hemoglobins, get patients out of the transfusion suite, and give them some more energy back, or drugs like danazol, a synthetic male androgen.

There are drugs that we repurpose, which is a common theme in oncology, from other diseases like multiple myeloma. We use drugs called IMiDs or immunomodulatory drugs like thalidomide, lenalidomide, or pomalidomide. These can all be used in myelofibrosis off-label to improve hemoglobin with responses of about 20 to 30%.

The reality is we can improve hemoglobin in some patients, we can improve symptoms in the spleen, but there’s still really a lot left to do.

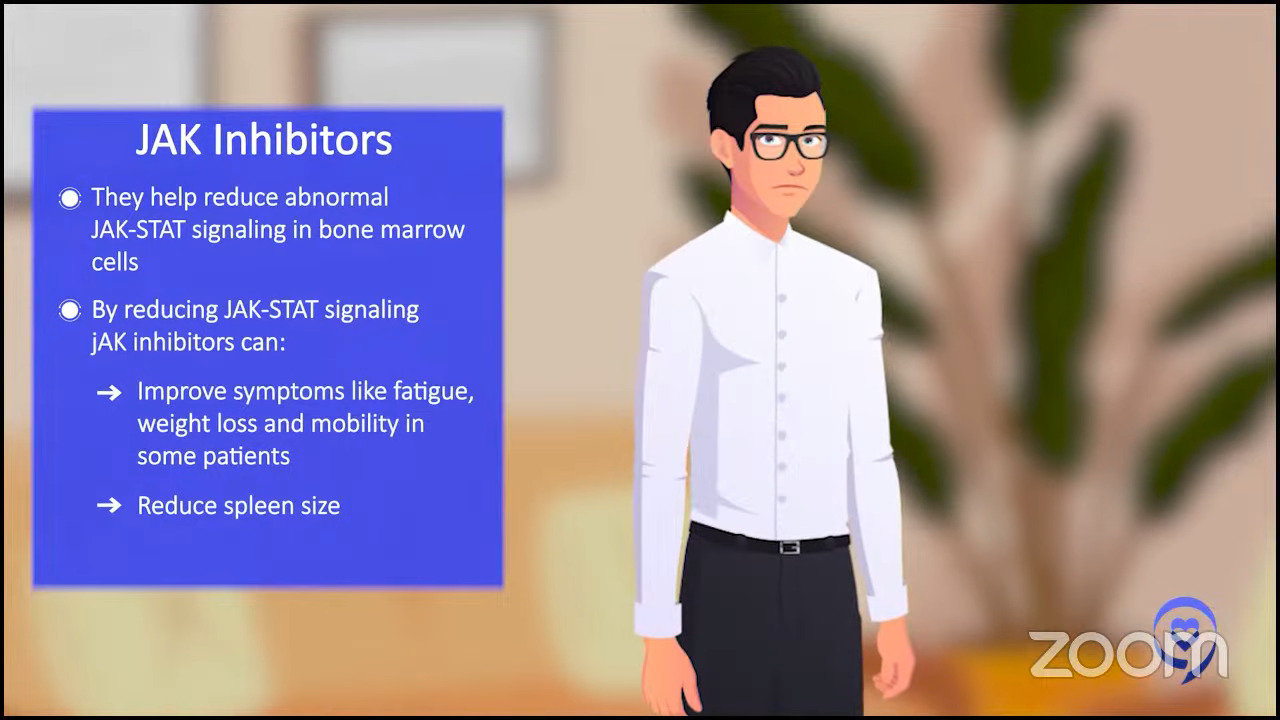

How JAK inhibitors work

Mary: Dr. Mascarenhas, could you tell us how JAK inhibitors work? What are their benefits and limitations?

Dr. Mascarenhas: JAK inhibitors are a class of agents interestingly invented in the setting of this disease and now have applications to a lot of different diseases that are not even malignant.

They intermittently reduce the JAK/STAT pathway that is inappropriately activated in the bone marrow cells. This pathway is responsible for causing the proliferation of blood cells and elaborating inflammatory mediators.

JAK inhibitors intermittently quell this cascade of events. That reduces the propensity to have this inflammatory state, this overproduction of blood cells, and seems to improve symptoms by reducing cytokines, which are inflammatory byproducts.

Patients feel better and can move and eat. It restores vitality for reasons that I personally don’t understand and I’ve never seen a good explanation for.

It also reduces the spleen. It’s a phenomenon I don’t really understand. It’s an interesting aspect of the drug. It reduces symptoms by reducing the activity of this pathway.

Unfortunately, these drugs don’t induce remissions. They don’t kill what I would call the maternal stem cell that gives rise to all of these abnormal cells. It doesn’t get rid of that cell.

It quiets down what’s happening in the bone marrow and the spleen allows for some degree of normalcy. The malignant cell population still remains in the body, in the bone marrow, and in the organs.

Unfortunately, we don’t see changes in the bone marrow that would lead us to believe that we’ve remitted the disease. Myelofibrosis is in the name. You have scarring in the bone marrow that typically remains even while patients enjoy the clinical benefits of the drug.

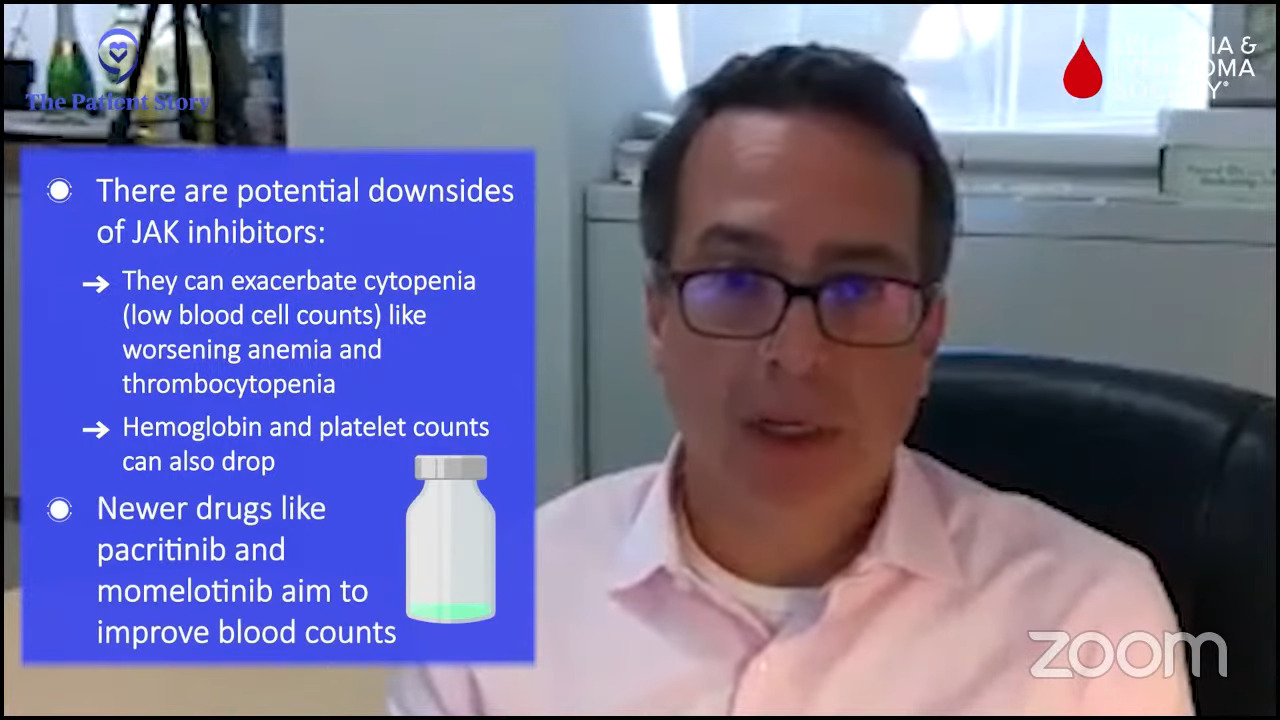

Then there’s the potential for downsides of the drugs. They often will exacerbate cytopenia or low blood count. Anemia and thrombocytopenia (low hemoglobin and low platelet) count can often get lower with these drugs.

We’ve pivoted to try to develop drugs that may not be as myelosuppressive, as count reducing and may even improve some of the blood counts.

Pacritinib can be delivered in patients with low blood counts and can improve hemoglobin in about 25% of patients. Momelotinib has also been associated with improvements in blood counts.

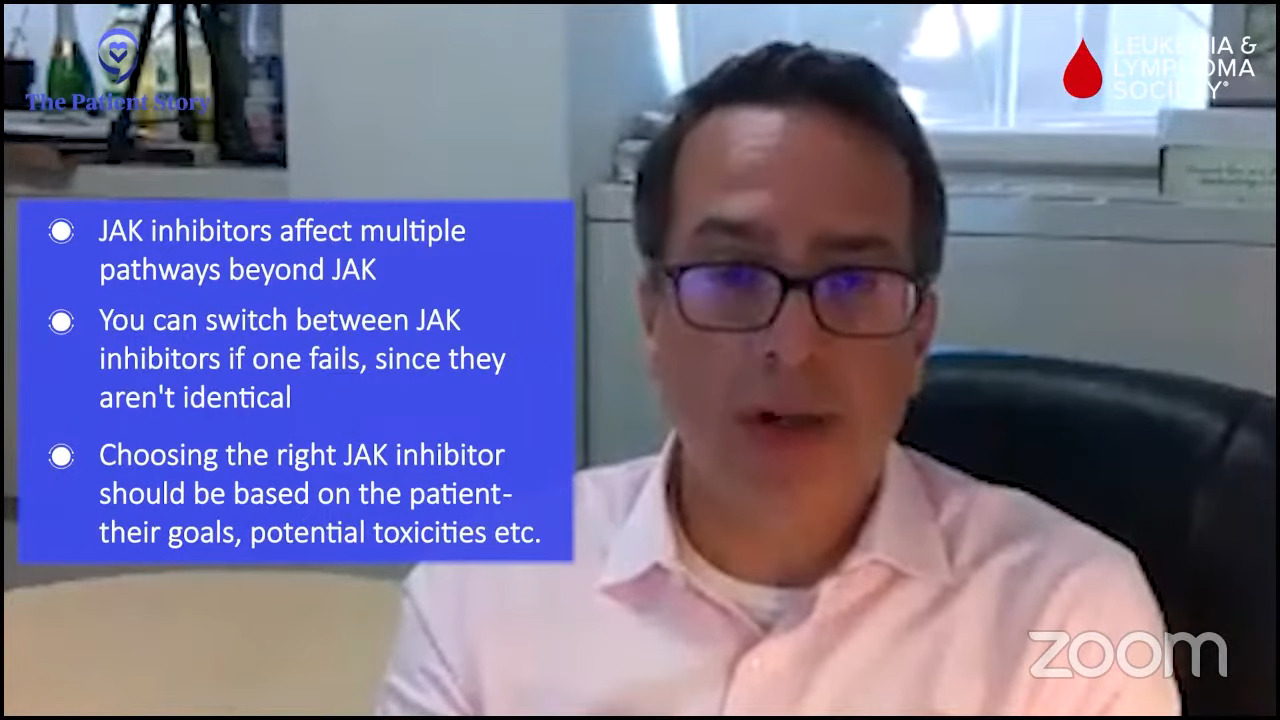

What we now know, which we didn’t know when we started off in all of this, is these drugs are not just JAK inhibitors. They interfere with a lot of different pathways that may be relevant and irrelevant and cause toxicity.

For example, inhibiting ACVR1, which is another pathway that’s important for iron availability, might explain why pacritinib and momelotinib improve hemoglobins and why maybe ruxolitinib and fedratinib.

There are a lot of nuances with these drugs that help us understand why they may fit niches and help certain people in certain ways and why you can provide serial JAK inhibitors.

If you fail one, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you wouldn’t enjoy some response to another. You can go from one to the other. The tailoring of the JAK inhibitor is somewhat of an art more than a science in some cases and requires knowing the patient, what the goals are, and trying to match the potential goals and potential toxicities to that patient.

Mary: Thank you for that. I’ve often heard that we’re not getting rid of our JAK2 but maybe turning the volume down on it a bit with the use of these drugs.

Determining the sequence of treatment

Mary: Dr. Jain, how do you know which JAK inhibitor might or might not work and which one to try first for a patient?

Dr. Jain: I’m going to piggyback on what Dr. Mascarenhas said and emphasize the point that no two patients with myelofibrosis will be the same. Everybody will have their own presentation or different things that you need to address.

Everybody will have a different trajectory in terms of their disease course and that’s what’s important to recognize as you’re thinking about what you’re going to start a patient on in terms of your choice of JAK inhibitor. We don’t have the same treatment for everyone. We’re looking at what we need to address in you as a patient.

If we’re trying to address high counts, a JAK inhibitor makes sense. If they have a big spleen and/or symptoms that will need to be addressed in combination with that, a JAK inhibitor would make sense based on the fact that we have the longest experience with it.

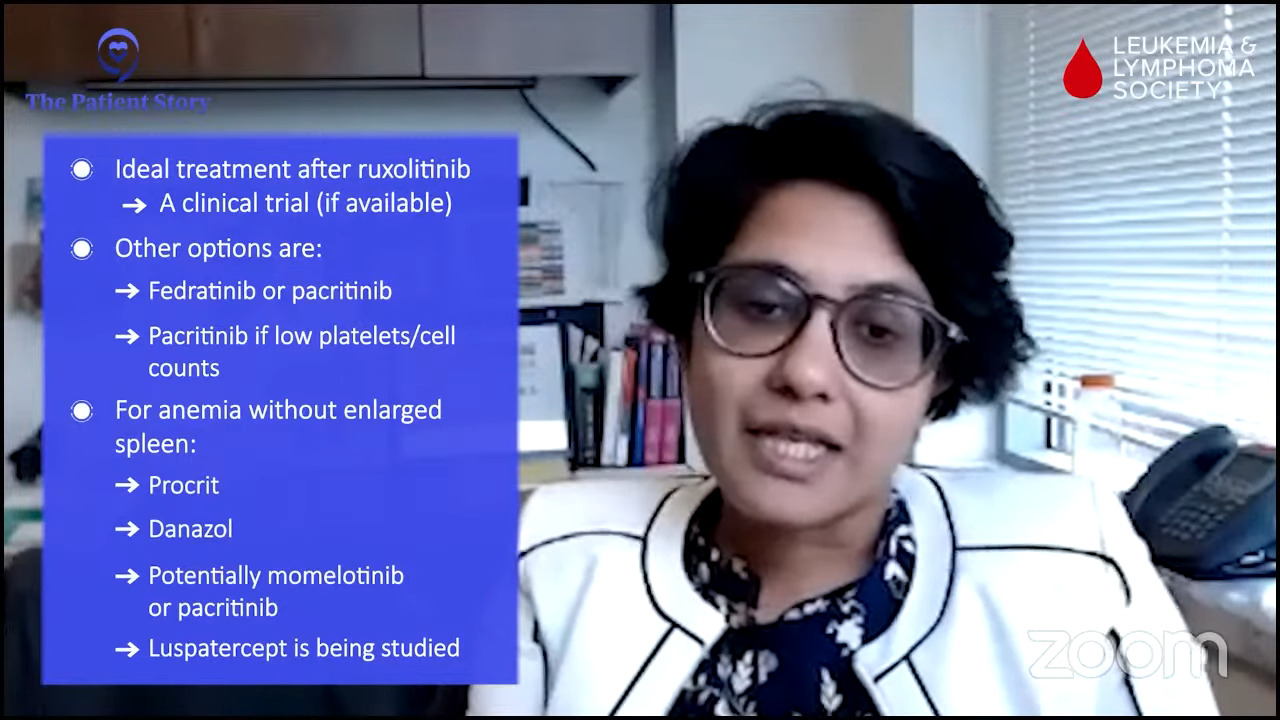

Ruxolitinib has been our first go-to. It was the first approved and we feel more comfortable with it. We know how to adjust the dose and move things around with it. If that doesn’t work, then the go-to next step in an ideal world would be a clinical trial.

If we don’t have one that would fit, it would either be fedratinib or pacritinib. The choice would depend on where the blood counts stand. If the platelets or the cell counts are on the lower side, pacritinib would probably be a better choice.

There are patients who have anemia as a major presenting symptom. In those situations, options such as epoetin alfa, danazol, pacritinib to some extent, and hopefully momelotinib in the future are some of the options. Luspatercept is in clinical trials; we’ll see how that pans out. Those will be some of the options.

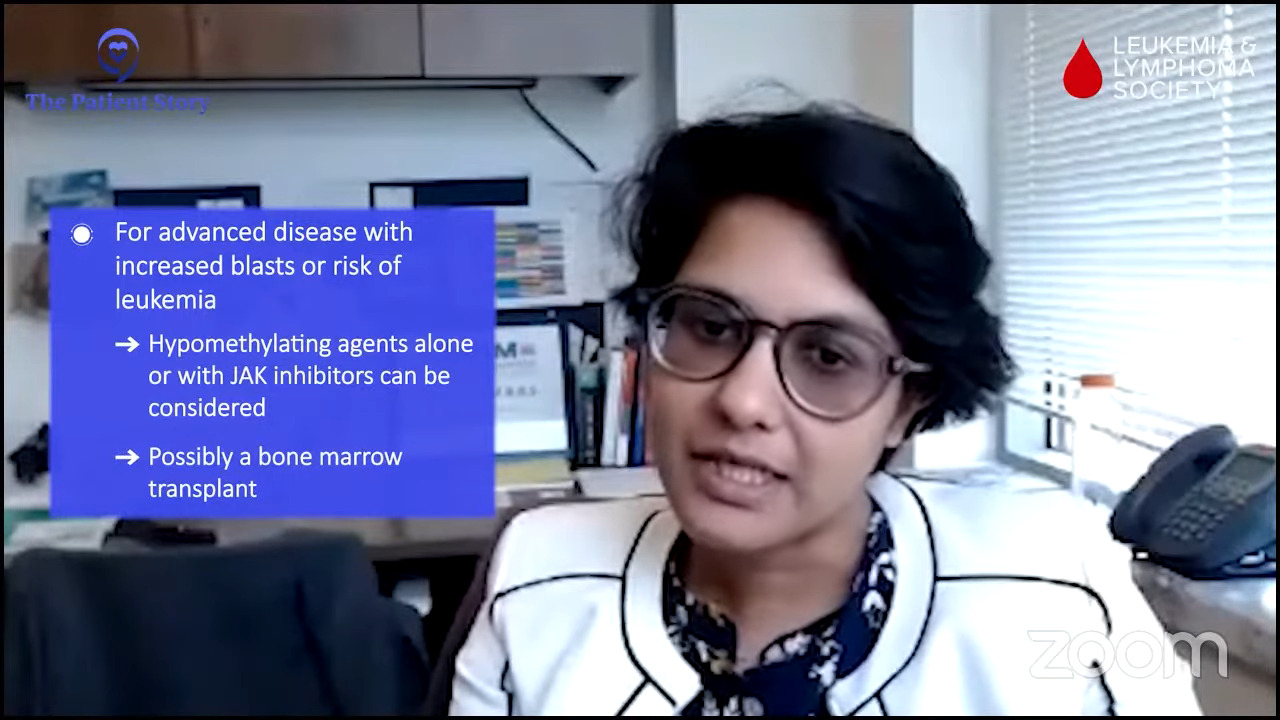

The third set of patients is those who come with more advanced disease in the way of more excess or a higher fraction of blasts or leukemic cells or very, very early cells in the bone marrow that indicate that these patients are headed towards the pathway of a more aggressive pattern of disease like leukemia.

In those situations, either in combination with JAK inhibitors or without something like hypomethylating agents could be considered usually en route to a bone marrow transplant, if that makes sense in terms of eligibility.

Stephanie: What’s clear is this is very individualized. There are so many considerations.

What are clinical trials?

Stephanie: Mary, can you bring us back to the day when you got the diagnosis? What was that like for you learning about cancer?

Mary: When I was initially diagnosed, it was over a long period of time so it wasn’t shocking exactly as I grew into it.

I thought back to my own father, who had a rare blood cancer in the late 1980s, had it for five years, and died at age 60. In fact, we were both diagnosed at age 55. I felt like I was somewhat prepared for how to manage this because I’m in the health field.

I had a bird’s eye view of it with my own father and I knew how to advocate for myself, especially since my dad had to advocate at a time when there really weren’t a lot of options for this cancer.

There’s a lot of fear and a lot of wondering. Will I be around to see my grandchildren? Will I finish my career? Will I make the contribution to society that I had hoped? Will I have a painful death?

I’m grateful over the years to have learned that I have so many treatment options available to me that I don’t look at the future as something grim at all. I just see it as my normal life.

I’m so grateful to learn of combination therapies because not all of us can make it to stem cell transplant, which is ultimately our cure.

There’s a whole lot more hope on the horizon for us with MPNs, particularly primary myelofibrosis. I’m just grateful for the research and the amount of research that’s being churned out these days, the clinical trials, and the combination therapies.

I’m so excited to be able to talk to experts in the industry about research and development towards not only treatment but cure for myelofibrosis.

Stephanie: We’ve talked a little bit about some of the drugs and combinations that are being studied now.

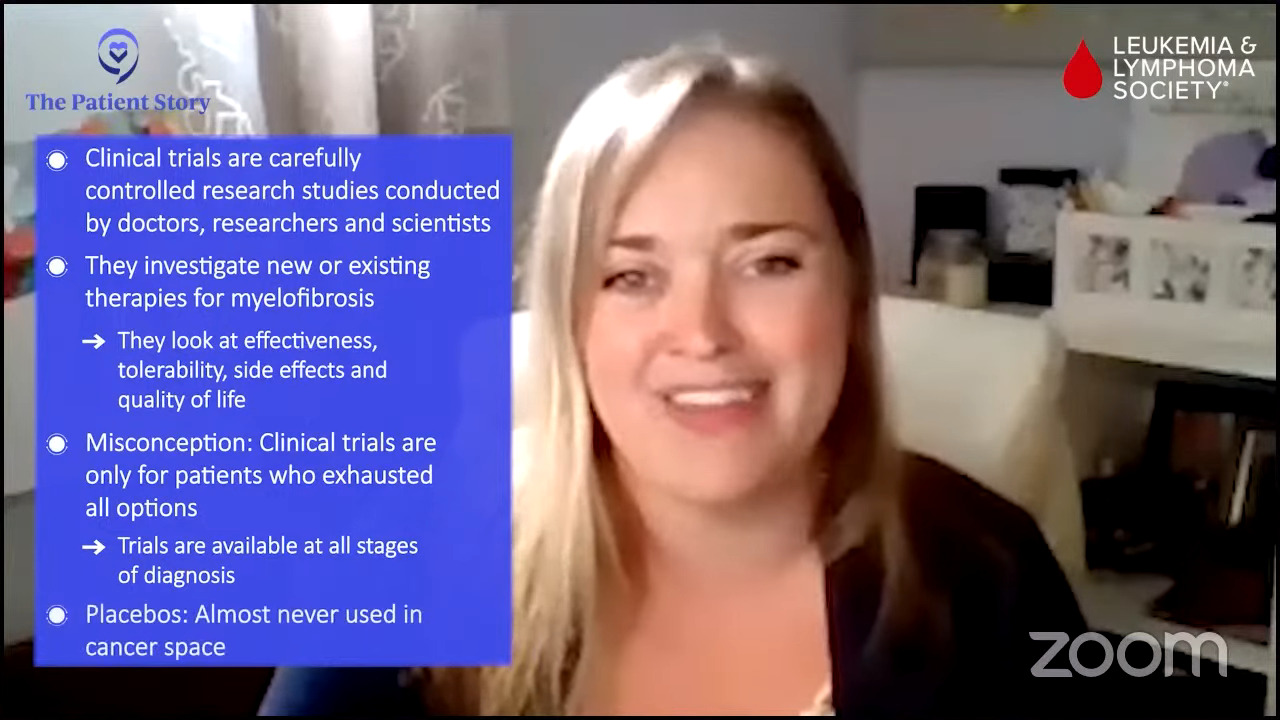

The first time I heard the term clinical trials, it felt a little daunting. There are lots of misconceptions about clinical trials. We do know that different stakeholders are trying to research what can be better to improve the standard of care for different patients and patient groups. One of the challenges is that people view clinical trials as a last resort.

Ashley, we know clinical trials might not be right for everybody, but they are an access to tomorrow’s treatment today. We’re sure you get lots of questions in your role at the LLS. What are clinical trials in layman’s terms and what are some of the top questions and misconceptions you hear from people?

Ashley: Clinical trials are carefully controlled research studies, which are conducted by doctors, researchers, and scientists. They may be investigating new therapies or therapies used in the past in a slightly different way or in combination with other therapies to find out which works better or might have fewer side effects. They’re looking at both tolerability as well as effectiveness of the treatments.

There are so many misconceptions out there, but one of the largest is that it’s for patients who have exhausted all options. That’s simply not the case. There are clinical trial options at all stages of diagnosis.

There are interventional trials, which test treatment options, as well as observational or registry trials, which help us learn more about myelofibrosis as a diagnosis but may not involve specific treatments.

Another concern that we regularly hear about is the use of placebos. Placebos have definitely gotten a bad rap. A placebo can be known as a sugar pill. They’re not very commonly used in cancer clinical trials because it just wouldn’t be right for us to use a sugar pill in place of somebody who needed active therapy for a serious or life-threatening disease.

When placebos are used, it would be in a setting where a patient doesn’t require any type of treatment at that particular moment or in combination with another therapy so that the patient is continuing to receive active therapy for the disease that they have.

Logistical concerns may come up as well. We always like to chat with patients about travel for clinical trials and what that might entail. We’ve talked about some of the academic medical centers and how important it is to have an MPN specialist.

Very often, investigators who are looking at clinical trials for myelofibrosis are in academic centers. We’re always encouraging and pushing for those clinical trials to be available in the community setting because traveling to and from those academic centers can be a real challenge for patients.

In addition to the logistical travel considerations, there are some misconceptions that clinical trial participation is free or that patients may even receive money for participating. Unfortunately, that’s not always the case. It’s really important that we explain that to patients.

Parts of the clinical trial that are investigational or are not approved will be provided by the clinical trial. Physician visits and lab work are things that we would expect patients to undergo if they were receiving standard care. Those will still get billed back to the insurance company or may have to be paid for in another manner.

Each clinical trial is structured a little bit differently and it’s hard to know from an overview, but really it’s important to have a general understanding before diving into the specifics of any clinical trial.

If you are participating in a clinical trial, occasionally, there can be stipends available to support the patient or caregiver and that’s why it’s so important to reach out and find out more and make sure that you have all the information you need as you make a decision about participating.

Mary: Thank you, Ashley. It’s so important to hear that we do have access to medication, not necessarily the placebo. A lot of us do worry about that. We also need to check in to find out what is available to us in terms of financing.

Momelotinib, a new drug

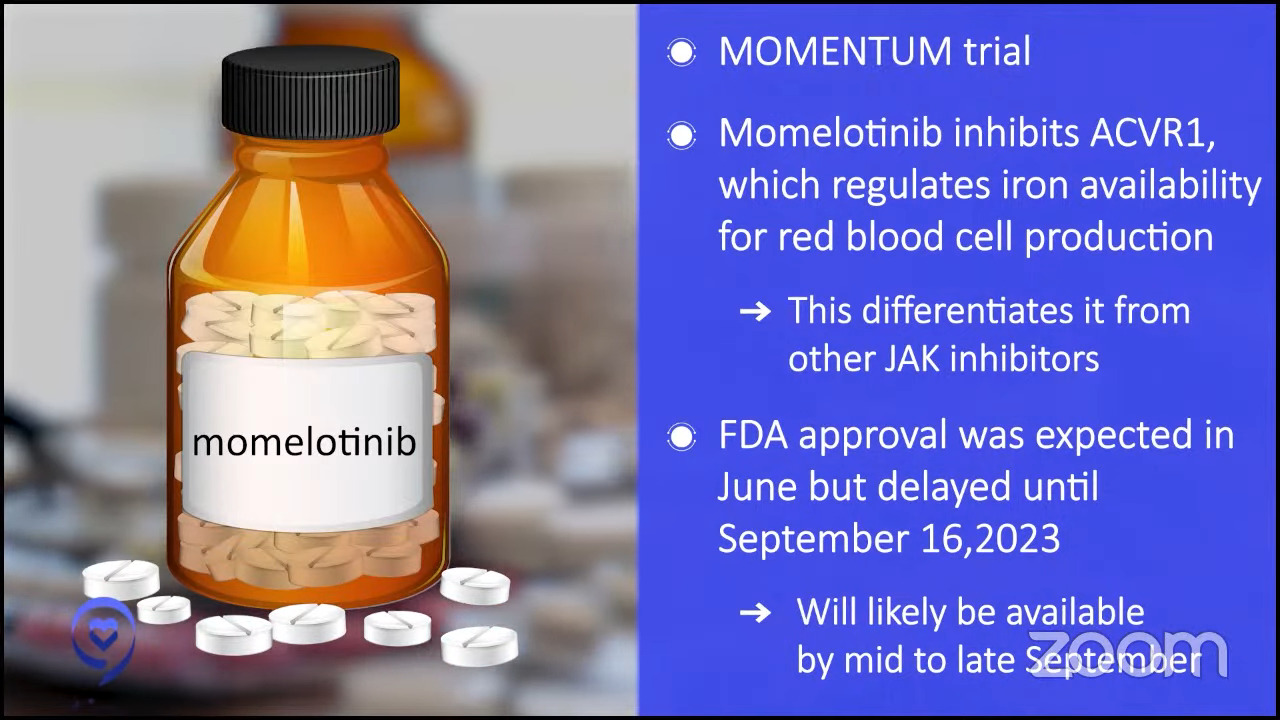

Mary: Dr. Mascarenhas, let’s talk about single-drug therapy. There’s a new drug that was recently FDA-approved, momelotinib. What patient might it benefit?

Dr. Mascarenhas: Momelotinib is a JAK inhibitor so it’s much like ruxolitinib except as I mentioned before, there are some nuances that make these drugs a little bit different. It also inhibits ACVR1, which is another pathway that regulates iron availability for red blood cell production. In its long development history, it’s differentiated itself from other drugs in large part by its ability to improve hemoglobins in a subset of patients.

It went to the FDA based on a study called MOMENTUM. The expected approval was in late June. It was delayed by the FDA, which is not uncommon, to September for re-review. My expectation is it will probably be commercially available in the pharmacies and available for prescription likely by mid to late September.

I encourage patients to discuss with their physicians if that drug might make sense for them or any of the other drugs that we’ve talked about, whether it’s fedratinib, ruxolitinib, or pacritinib. As we’ve said, it really has to be tailored to the patient.

I’m excited to see momelotinib come up. For a physician, it’s great because it gives us different options and allows us to tailor the treatment for each patient. That might be a great opportunity for some patients to either embark on that therapy or switch.

The clinical trials set the tone for the interactions with the FDA about what that label would look like based on the way the clinical trial was designed and run. We can only guess that there may be stipulations.

It may only be available after the use of a first-line JAK inhibitor or it might have to have certain requirements for depth of anemia level. There are some nuances that sometimes play into the decision-making and these are based on the clinical trials that led to the approval.

Best drug combination therapies

Mary: Dr. Jain, there’s combination therapy to think about. June F. asks, “What are the best drug combinations at present?” Can you introduce us to combination therapies?

Dr. Jain: I’m not sure if I can answer what the best drug combination is right now, but hopefully that is a question we will learn more about and address in the future.

There are drug combinations that are promising. It brings options that we can offer to patients. They’re mostly in clinical trials but hopefully, some will move the field forward.

Historically, we addressed the JAK/STAT pathway, which we have learned the most about in the last couple of decades. That is the primary pathway involved in the occurrence of myelofibrosis.

As we have learned more over the years, there are other pathways that are critical to the development of myelofibrosis and that is where the rationale for drug combinations comes in.

We’ve seen several clinical trials that have addressed that or used combination therapy in patients who don’t have a good response to ruxolitinib itself and need more than that. Many of those drugs have been tested in the first-line setting to see if patients would do better with combinations upfront rather than ruxolitinib alone, which has been the long-standing go-to first-line treatment for over a decade now.

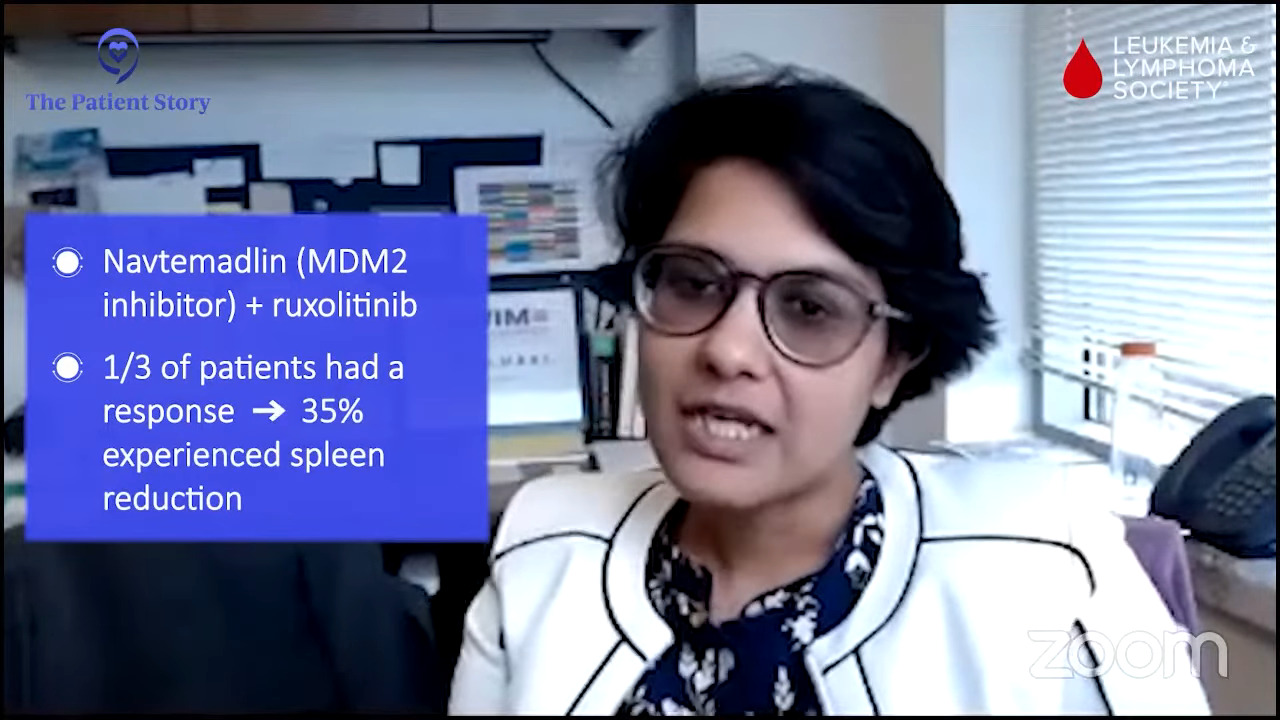

Some of the drugs that you’ll hear about are navtemadlin, for example, which is an MDM2 inhibitor. Dr. Mascarenhas presented data at EHA that showed a 35% spleen reduction in about one-third of patients in patients who weren’t responding to ruxolitinib itself.

There are BET inhibitors like pelabresib that I heard Dr. Mascarenhas talk about at ASH, which also is being tested in the first line in patients who are starting upfront treatment.

There are BCL-xL inhibitors like navitoclax, which have shown some improvement in the second-line setting. We’re awaiting a public announcement on the data for the first-line trial.

The premise is that you’re combining two mechanisms that have shown to work such that you do not have overlapping toxicities. That’s an important piece to remember.

JAK inhibitors can cause some decrease in blood counts; we’ve seen that with ruxolitinib. You want to add a drug that may not do that as much or may not do that to an extent that makes it prohibitive of a combination.

With pacritinib, for example, patients often would get gastrointestinal toxicity so don’t combine a drug that may also have gastrointestinal toxicity. That’s important to remember as we think about combinations, which we will see more and more in the future.

Logistics are certainly important to consider as we’re thinking about clinical trials, what the trial offers, the frequency of visits to the center, and whether that makes sense in terms of continuing to be on it or not.

When to consider combination therapy

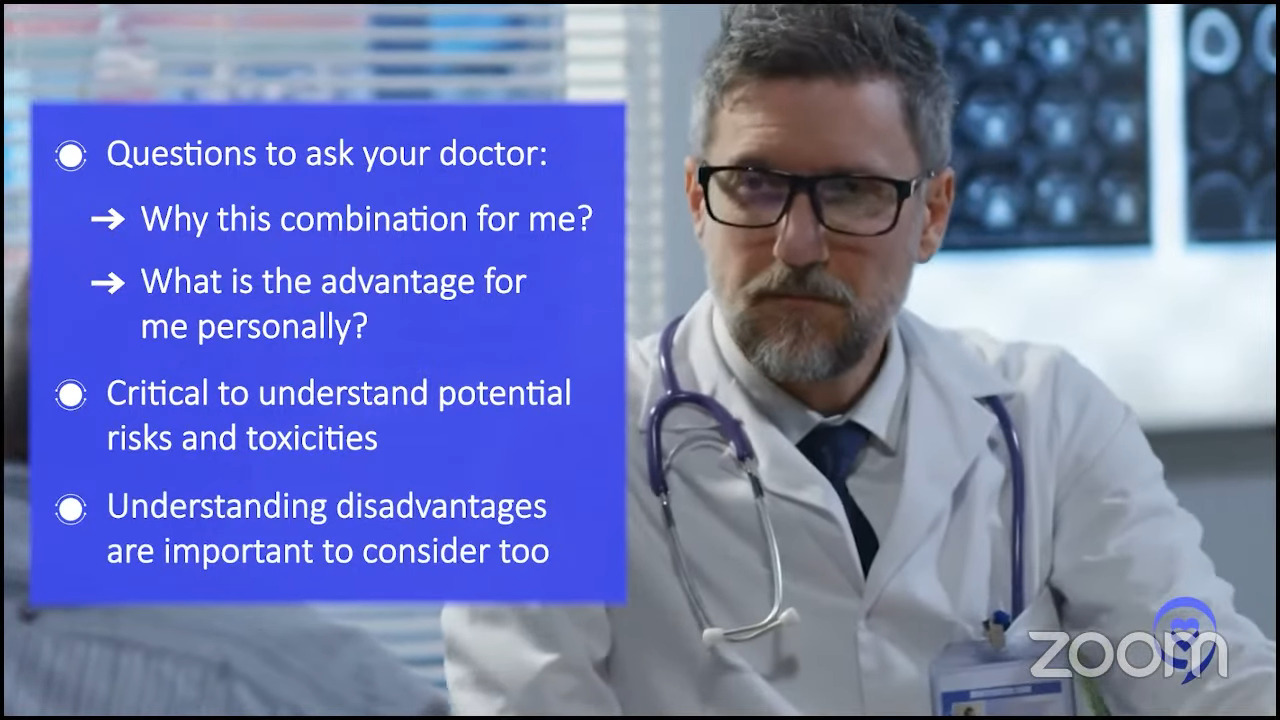

Mary: Dr. Mascarenhas, what should patients ask when considering a combination therapy like Dr. Jain just talked about? How do we know when it’s right or the right time to start one?

Dr. Mascarenhas: The first question to ask is: Why is this combination for me? What would be the advantage in my case in terms of addressing my goals of therapy? Importantly, what are the potential risks?

As physicians—and I’m definitely included when I say this—we often focus on what we think is going to be the advantage of participating in a clinical trial. The reality is there are disadvantages sometimes. There can be toxicity associated with approved drugs and unapproved drugs that are in clinical trials.

Patients want to understand expectations of results and the potential toxicities that one could incur. What does the patient need to be aware of in terms of mitigating and reporting?

A trial is not really a passive experience. Patients are active participants. They’re not simply receiving a drug. They have to be very willing and engaged to report all symptoms and not just what they think might be important. They need to report everything to the study team.

That might involve calling ahead of their visit to let the team know what’s going on, making sure that all their medications are accounted for, and they’re following up. It’s an opportunity to assess whether a drug is active and adequately characterize the toxicities of a drug. As the drug moves along, it’s optimized in the delivery for future patients.

There are two objectives. How is this drug going to help me and what is my role in this whole process? It really should be a joint venture. It’s not a one-sided experience. We learn from the patients. Hopefully, the patient community learns from what we’re doing and everyone benefits.

Stephanie: Dr. Jain had set up the landscape of combination therapies and talked about different options. Dr. Mascarenhas, it’d be great to run through a few specific combinations.

Dr. Mascarenhas: Clinical trials today to a large degree are unlike what clinical trials were historically. These drugs are all rational with supporting pre-clinical data. People don’t always realize that they go through enormous amounts of testing through various aspects before they ever enter a human being.

There’s an enormous amount of regulatory burden that exists that’s really annoying but really important because it provides that sense of confidence in the investigators but also in the patients that what we’re introducing makes sense. We’re not just taking something off the counter and saying, “I wonder if this is going to work,” and throwing it into a clinical trial. These are rationally developed drugs.

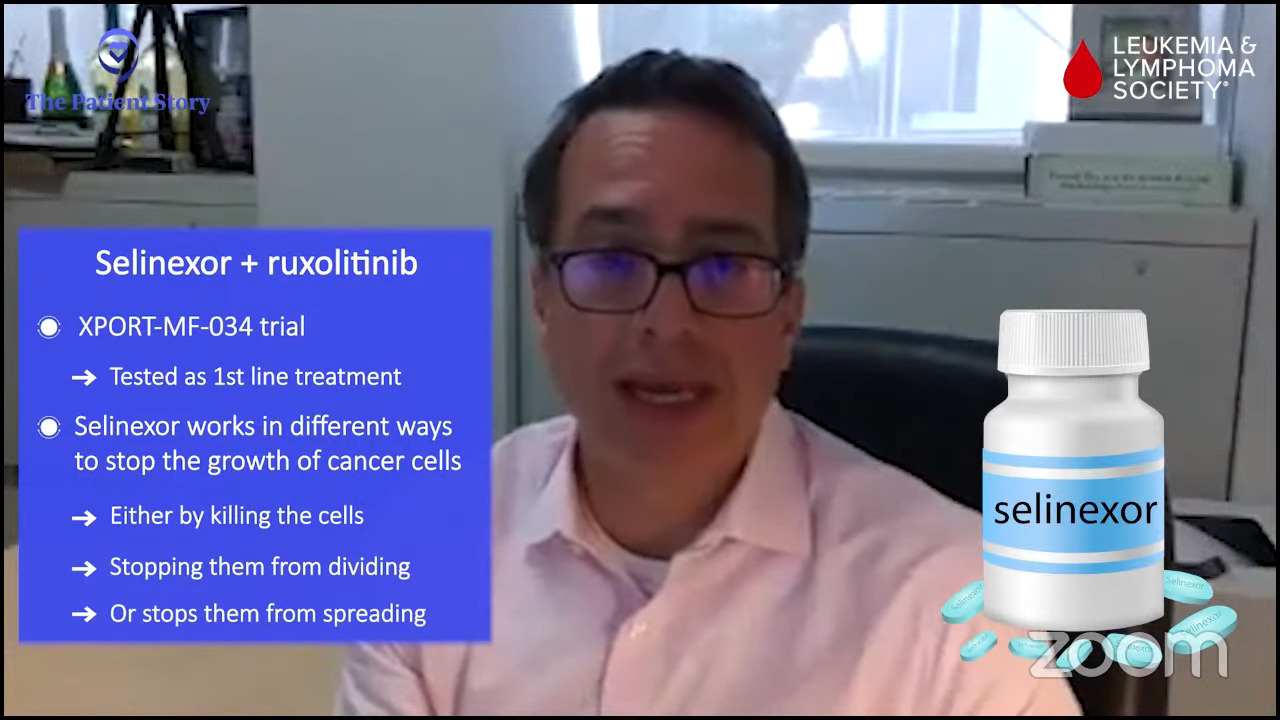

An example is selinexor. Selinexor is a really interesting drug. It’s already approved for blood cancers that are not myeloid cancer like multiple myeloma and other B-cell lymphomas. This drug affects the shuttling of proteins in different compartments in the blood cell, in the nucleus, and in the cytoplasm.

Why does that matter? Because if you can affect where proteins are in a cell, you can ultimately affect the functioning of these proteins. Selinexor inhibits this shuttling protein and affects the way certain proteins exert their function, which might be important to the pathophysiology of the disease. This might even turn on other proteins and put them in an area where they can actually induce a good effect.

For example, there is probably a multitude of different changes when you use a drug like selinexor that shifts the cell’s functioning from one in which it’s acting inappropriately and nefariously into one in which you try to induce it to die through normal mechanisms.

There are normal mechanisms that are built into our cells that if they get corrupted by a virus or by cancer, they turn on this mechanism called apoptosis and undergo programmed cell death. Cancer cells have ingeniously figured out ways to get around that. We struggle each day to figure out ways to get them back on track, to encourage them to recognize that they’re inappropriate and to undergo this programmed death.

Selinexor is a great example of a drug that affects multiple pathways and induces myelofibrosis, perhaps even the primordial cells, to undergo this process of death. It works best in combination with ruxolitinib and that’s a common theme that we’ve seen.

In oncology, it’s very rare, except for maybe CML or some other diseases, that we use monotherapies. In most of oncology, we use combination therapies to synergize together to get deeper responses and avoid overlapping toxicities.

That’s what we’re seeing with drugs like selinexor or navtemadlin, which has a great wealth of data at this point. These drugs are active as single agents, but they seem to be even more active in combination.

This is supported by studies that are done in mice that are engineered to have myelofibrosis with primary cells from people who have been generous enough to donate their blood cells. We experiment and figure out how we are going to make better drugs in the future.

I thank those patients. Seems like a small thing, but it’s a huge, huge aspect of how we move this whole machine forward in clinical research. All of that information allows us to say this combination really looks effective.

We’ve got JAK inhibitors that are commercially available. We’re going to add this drug that synergizes nicely in preclinical models and cells in the dish. We think it’s going to work better than each drug alone and we’ll figure out how to dose them and schedule them to minimize toxicity. That’s really where we’re seeing it.

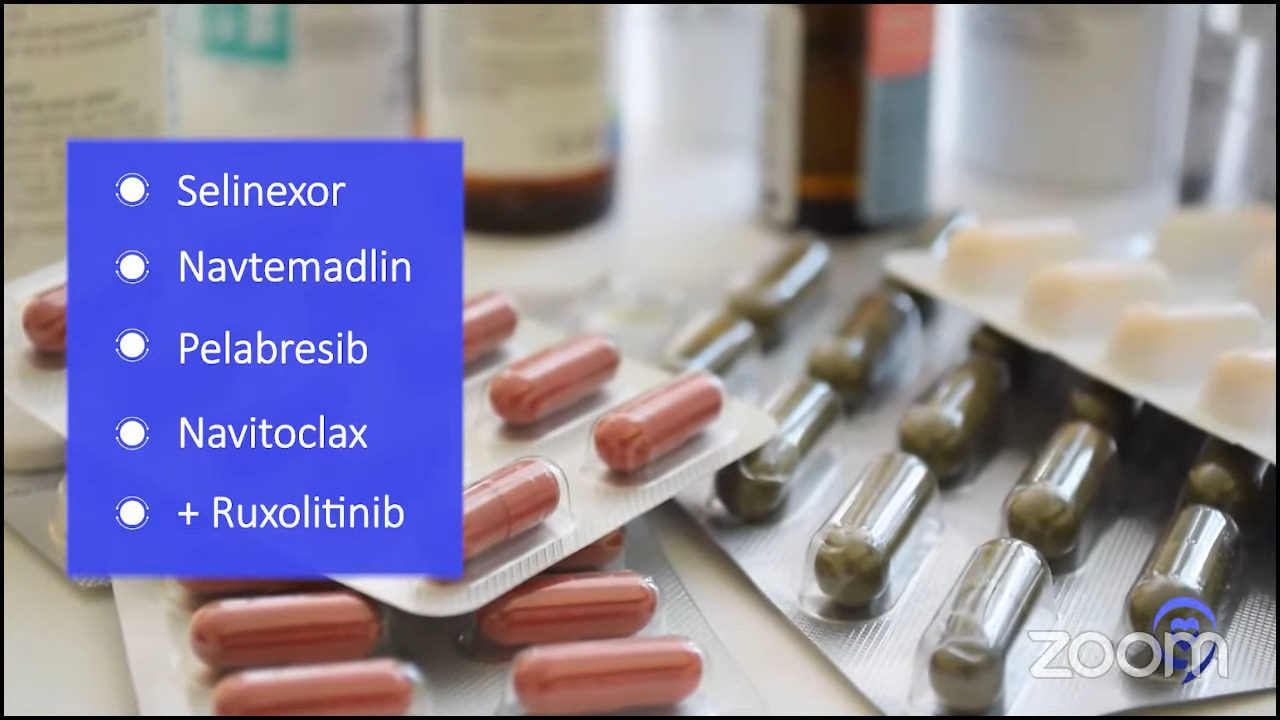

Selinexor, navtemadlin, pelabresib (BET inhibitor), and navitoclax (BCL-xL inhibitor) all look good in combination with ruxolitinib. As Dr. Jain said, ruxolitinib has been around the longest and that’s the go-to drug that we combine drugs with.

We’re not even waiting anymore for patients to have failed the first line of therapy. We’re introducing the drugs earlier on. We get confidence in their ability and their toxicity profile. Why wait for patients to do worse? Why not try to get deeper responses earlier on?

The deeper we can reduce the disease burden, we believe that the better the patient will be overall. They will not simply feel better but have smaller spleens, which is important. Fewer disease cells in their body will hopefully mean longer progression-free survival.

Navtemadlin, selinexor, pelabresib, navitoclax, imetelstat — there’s a whole host of drugs that are aiming to really hit the clone and induce deeper responses.

Second-line treatment after Jakafi

Mary: For people who have been on ruxolitinib and, for whatever reason, the treatment wasn’t effective, what treatment options are available?

Dr. Jain: That’s a common situation we run into because as Dr. Mascarenhas pointed out, ruxolitinib has a very strong role. There are a lot of things that it does do, but there are a few things that it doesn’t do. Based on registration studies and clinical practice, if it works, it works for a few years and then we start losing that response.

A clinical trial available that would be a combination of a JAK inhibitor with something else or something added to ruxolitinib itself would be my go-to to consider. There are several of those going on at this time. There are also trials with single-agent drugs.

The way drug development goes is there’s testing of efficacy by using the drug alone. Then once we are comfortable with their efficacy and safety profile, we add it onto a ruxolitinib or a JAK inhibitor backbone.

If we see efficacy and safety in that combination, we move it up the ladder a little bit more and try to investigate if that would be a better option in the front line compared to ruxolitinib itself.

There are non-JAK inhibitor combinations that get added to ruxolitinib. Navtemadlin, an MDM2 inhibitor, has data. It restores the natural cell-killing pathway that should happen but is not working very well for some reason. We’ve seen patients respond in a post-ruxolitinib setting in terms of their spleen and symptoms.

There are other drugs like navitoclax, a BCL-xL inhibitor, that show responses in about one-third of the patients who were not having a good response to ruxolitinib by itself.

Pelabresib is a BET inhibitor. There are other BET inhibitors in the pipeline that are being developed with slightly different nuances to their conformation and how they inhibit the pathway. These are some of the categories of drugs that look promising and worth looking forward to.

Imetelstat has emerging data. It’s slightly different in the way it works. It inhibits the telomerase activity. It’s one of what we think happens in myelofibrosis or leads to that, even though the telomerase length may be not as long or in fact short. The telomerase activity tends to be high and that’s what imetelstat inhibits.

I’m sure I’m missing some here and that’s not for the lack of preference. Selinexor is another one that Dr. Mascarenhas already mentioned.

I would tell my patients that if we can get our hands on one of these combination clinical trials at that time, that would be my first go-to option.

If for any reason there are no clinical trial options available after ruxolitinib, then obviously there are other JAK inhibitors like fedratinib, pacritinib, and hopefully soon momelotinib. Patients may still benefit even though they stopped responding to or did not achieve benefit from ruxolitinib as a front-line JAK inhibitor.

When to get a second opinion

Mary: When is it right for a patient to seek a second opinion during this time of figuring out the right treatment options?

Dr. Mascarenhas: The right answer always is now. I don’t think it ever hurts to seek a second opinion at the time of diagnosis to confirm the diagnosis. There is a lot of heterogeneity in the way these diseases can present. There are overlaps and nuances.

It’s important to seek a second opinion because you may be a patient who should be considered for a bone marrow transplant, which is the only curative option we have. Sometimes that’s delayed too late and the patient misses the window of opportunity. For some patients, that may not be on their plate but having that discussion is really important.

I don’t recommend seeing lots of different people; that can be problematic. Getting a second opinion at each stage never hurts — at the time of diagnosis, if you’re not doing well on your first therapy, and when there’s consideration of second therapy.

If you have a physician who gives you pushback about getting a second opinion or comes across negatively, you might want to find another physician because it shouldn’t be an ego thing.

It’s your life. You’re dealing with cancer. You should feel free and confident that a second opinion is not a reflection of your treating physician. It’s getting more information and the more information you have, the better the outcome.

Dr. Jain: I agree with that 100%. The MPN community is small but also very well knit and I think we work very closely together. I’ve asked my patients to get second opinions and I’ve set them up for them if they need to go. I’ve sent patients to Dr. Mascarenhas and to others if there is, for example, a clinical trial opportunity that we may not have and they may have.

Sometimes it’s better for them to hear it from more than one person. We do a lot of things similarly, but there are some that we may have different perspectives about.

A common joke is if you ask 10 MPN experts, you’ll get 12 different opinions, and not because anything is right or wrong. There just may be a slight difference in our prior experience with a particular strategy or what our perspective about a particular strategy may be. All those are important things.

The role and timing of the transplant may benefit from a second opinion. Get another perspective as to what their center’s experience has been and how they may do something different. There are nuances to every transplant center and some of it may be more beneficial to you. Geography obviously plays a big role.

How to look for myelofibrosis clinical trials

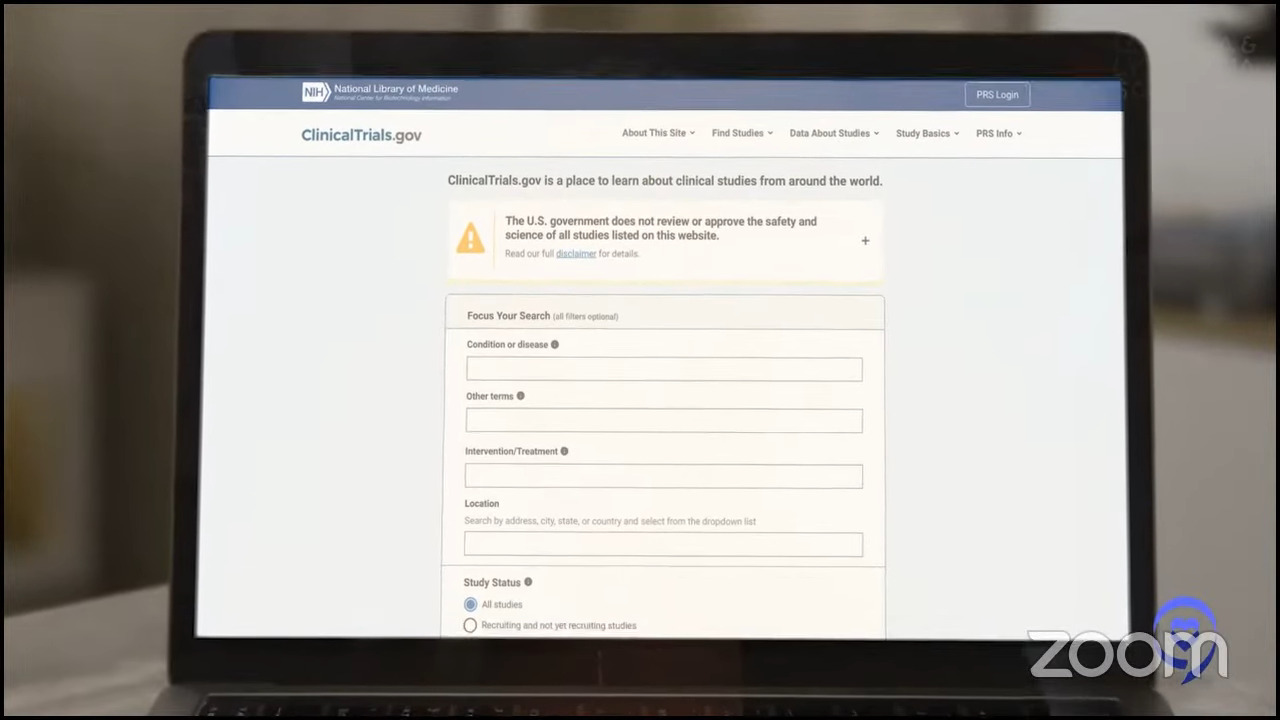

Stephanie: We’ve talked about treatment options in myelofibrosis, but when you actually come down to needing to find one or stay on one, there are so many questions that we all encounter. We know that ClinicalTrials.gov is out there, but it’s a little bit difficult to navigate and that’s why the LLS’ Clinical Trial Support Center is so important. Ashley, what are your top recommendations in terms of looking for clinical trials?

Ashley: Often, people try to go about it on their own. ClinicalTrials.gov is the most comprehensive database of all clinical trials. In addition to cancer clinical trials, there are also clinical trials for all types of disorders and diagnoses.

It’s not always easy to hone in on what you need depending on past treatments you’ve had or medical history so it can be a challenging situation to find clinical trials that are actually applicable to you as an individual.

We always encourage reaching out to The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. We have the Clinical Trial Support Center, which was developed as a response to help patients find clinical trials that are appropriate to them as unique individuals.

It’s a free service staffed by nurses who have expertise in blood cancers and clinical trials. Nurse navigators connect one-on-one with patients, caregivers, or even other healthcare providers who may need to learn more about potential clinical trial options.

We find out more about the patient’s diagnosis. We learn about any past treatments they may have had and find out about their medical history because all of those factors will play into a patient’s eligibility to participate in a clinical trial.

We also take a long time to find out about patient preferences and any unique obstacles that could hinder or drive participation in clinical trials. We help tailor some of the support and resources that we’re able to provide so that patients can overcome some of those barriers that may be in place.

After we’ve generated all of that information and really taken the time to get to know the patients, we produce an individualized clinical trial search. That could be related to geography and preferences. What matters most to the patient? Is this something that they’re really not interested in spending a long time in the hospital if they can avoid it?

We definitely look at all of those and produce a list that can be taken back and reviewed with their treatment team so that that can be part of the informed decision-making with the patient’s next steps.

We are available for all blood cancers, including myelofibrosis and other MPNs. It’s important to know that patients can reach out.

Half of the ongoing clinical trials are cancer clinical trials, but sadly, only about 5% of cancer patients actually enroll or participate. There’s so much opportunity out there and we’d really love to help overcome any barriers that patients might have so that they can consider participating.

The role of stem cell transplant

Stephanie: Transplant is such a huge topic for so many people and they hear so much about it. In the context of the landscape changing so quickly, do you feel that you and other specialists in the field will be recommending transplants less to people? This is probably a very individual response, but with everything happening, what’s the trend?

Dr. Jain: I actually think of it the other way. By virtue of having more effective treatment strategies to improve the spleen and symptoms, and get a disease response, we may be able to take more patients to transplant as a curative therapy.

A lot of times, lack of spleen response, poor performance by virtue of a lot of symptoms, or disease advancement into a more aggressive disease pattern become barriers to transplant. Having more options in the future will allow us to take more of these patients to transplant.

We’ve seen a lot of advances with a lot of these options. What we have not seen so far is the curative potential. Hopefully, we will in the future. All of these drugs have a lot of advantages in terms of improving spleen symptoms and cytopenias but we have not had definitive improvement or getting rid of the abnormal stem cell clone. That’s something that at least so far we’ve only achieved with a stem cell transplant.

At some point, as long as patients are eligible for transplant and that is something that would fit their life wishes in general, that would be a curative option to consider. Better non-transplant treatments will only get more patients to something more curative like a transplant.

Dr. Mascarenhas: I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Final takeaways

Stephanie: We’ve covered a lot of ground in a short amount of time. If there’s one thing you’d like for our audience of patients and care partners to walk away with, what would that be?

Dr. Mascarenhas: I hope to share my enthusiasm and optimism that we are making advances. There is a brighter future and I’m really genuinely excited about that.

Embrace the opportunity of clinical trials. Clinical trials are looked at for other people, but they may be important for you. Talk to your physicians. You may not go through with it but learning about it and exploring it is important for each patient.

Dr. Jain: It’s never a wrong time to see a specialist or to see someone else if something is not working out. Some symptoms are nonspecific. Never hesitate to be an advocate for yourself, to get things done, and to seek a second opinion.

As a transplanter, I’m obliged to pitch in that getting an opinion about transplant and at what course in your disease that makes sense is important to address. You don’t have to wait until you’re progressing or not responding to drugs. That needs to be addressed and outlined in an early appointment rather than waiting for too long.

Ashley: I really want to echo what’s already been said. It’s so important to consider clinical trials as part of the treatment plan. Even if they may not be an option at that particular moment, it’s important to be informed and look at all of those components as you’re making an informed decision about the treatment plan with your providers.

As a representative of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, I would really encourage any patient with myelofibrosis or any MPN to reach out. The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society has so many resources available, including clinical trial support but also so many others that we would really enjoy the opportunity to connect and provide those resources to patients.

Mary: Continue to have hope. Continue to want to thrive and live.

At the beginning of my journey with myelofibrosis six years ago, I was told I’d be dead by 72. Now they’re saying you could outlive this. You could die with this, not of it. Hearing both Dr. Jain and Dr. Mascarenhas talk about all these combination therapies and how they actually might get us to the cure was very exciting.

Conclusion

Stephanie: Thank you so much, Mary. Your story is so powerful. It’s also on our platform so feel free to check out Mary’s story.

Thank you to Ashley from The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and to Dr. Jain and Dr. Mascarenhas for the work that you’re doing to push forward research and help patients and family members better understand their options in myelofibrosis and MPNs altogether.

I hope you’re able to take away something that was really key for you, because that’s our goal, to empower you in your own care. We look forward to seeing you at a future program.