Jacqueline Barrientos, MD

CLL Treatment

Hear from experienced CLL specialist, Dr. Jacqueline Barrientos, who talks through what CLL is, treatment options, and the trend of drug research.

- Name: Jacqueline Barrientos, M.D.

- Role:

- Associate Professor, Oncology Research

- Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research

- Associate Professor, Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology

- Northwell Health

- Principal investigator

- Associate Professor, Oncology Research

- Experience: ~15 years

- Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY

- Clinical Fellow

- Associate Professor, Karches Center for Oncology Research, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research

- Associate Professor, Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell

- Approach with patients: Finding the therapy that gives the best outcomes and quality of life

Many times, people don’t really want to know about it and just want to listen to their doctors. The field is changing so quickly that I think the most important thing you can do is to be an advocate for yourself.

Introduction

Can you introduce yourself

My name is Jacqueline Barrientos. I’m an associate professor of medicine at the Zucker School of Medicine in New York on Long Island. I work at the Northwell Health Cancer Institute’s CLL Research and Treatment Program.

Why did you get into oncology

We are making so many advances so quickly. I went into oncology because I think that chemotherapy will be a thing of the past for many cancers and especially in the blood.

If you know what is driving the cancer, then you can just target that driving factor, and you don’t have to affect the other healthy tissues. It’s amazing what we’ve been able to accomplish in the last 10 years.

People who had a very difficult cancer to treat can now just take a pill and go on with their life and not even have to spend hours getting an infusion.

It’s just amazing to see it, and it’s very rewarding to see patients living longer lives and have very small side effect profiles from these new drugs.

What is CLL

Is CLL leukemia or lymphoma

The disease has its two components. It’s called chronic lymphocytic leukemia because it has two parts. On one hand, there’s the blood cancer part. It’s a disease of the blood. That’s the leukemia.

On the other hand, you have enlarged lymph nodes. The way that these cancer cells live and proliferate is by going to the lymph nodes. Once they grow in the lymph nodes, then they go back out into the blood.

Some patients present with only the enlarged lymph nodes and no evidence of leukemia in their blood. Those people are called SLL patients, which is like a sub-sub-type. They present a little differently, but it’s the same disease.

»MORE: Learn more about CLL→

CLL Treatment (2020)

Why is it important to see a specialist

It’s very important to see a specialist when you’re dealing with CLL to ensure that the physicians can make decisions based on a patient’s markers.

What are important genetic markers to test for

There’s a marker called 17p deletion. That’s a very bad mutation. It not only tells you that the disease will be more aggressive, but it also does not respond to chemotherapy. Even new targeted therapies that are now being used still see these patients relapsing fairly quickly.

Less than 10-percent of patients will have 17p deletion at the time of diagnosis, but over time, people can develop it. It’s kind of like clonal selection. Because the therapy is not curative, the cancer tries to come back, and when it does, it becomes more aggressive over time.

That’s why some patients stop responding to the treatment. One of the reasons a patient may stop responding to the drug is because their cancer can actually develop a mutation to it.

There’s another group of people. 90-percent of patients don’t have 17p. What do we do with them? It all depends on other markers.

Another important marker is called IgHV mutation status. This is a gene mutation of the heavy chain of immunoglobulin. There’s a test that’s not widely used, but we use it here. As a patient, I would want to know my status. You can be either mutated or unmutated.

Mutated patients usually have a very slow-growing disease, and on average, they don’t require therapy for the first eight years after their diagnosis.

If you are not mutated, most people require therapy within the first three years. It’s more aggressive. When treated with chemo, these are the patients that will have a shorter time in remission compared to mutated patients.

With mutated patients, you can give them chemo and immunotherapy, and more than 10 years later, they will still be in remission. You can essentially “cure” them.

When does a CLL patient need to start treatment?

The majority of patients present with abnormal blood counts. The normal maximum number for white blood cell counts is 10,000. Many patients present with 20 or 30. Over time this number can increase to even 40, 60, or 100. There is no magic number at which we decide to start therapy.

We monitor and when patients show symptoms like anemia, low platelets or painful enlarged lymph nodes, then we’ll start therapy.

Usually, enlarged lymph nodes are cosmetic. You may notice them because they’re there, but if they don’t cause pain, we won’t usually start therapy because the treatments can often have more toxicities than the disease itself.

How does a specialist decide on a course of treatment?

If a patient has the 17p deletion marker, they need to be on a targeted agent like ibrutinib, which is a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor.

It doesn’t kill the cells, but it tells them to stop surviving and proliferating so eventually the cells start to die, but it doesn’t work immediately. You have to take the drug every day.

We just published some data comparing that drug against the best chemo regimen. The big winner was ibrutinib. Even in younger people, the best therapy is a targeted agent. Not only in patients with 17p, but with other markers as well.

For unmutated patients, we stay away from chemotherapy.

We only do targeted agents. Right now, category guidelines in the United States say to give you ibrutinib. It is frontline for young people and older people.

New Drug Research

What research is being done on ibrutinib?

There have been attempts to improve the outcomes of ibrutinib because it’s a wonderful drug. The problem is that it’s a drug you take forever, so of course, you can develop side effects.

One common side effect is high blood pressure, so you can also wind up having to take an anti-hypertensive. The other side effect you can have with Ibrutinib is joint pain. Even if you’re young, it can be debilitating for you.

There are other drugs that are like second generation Ibrutinib that are being tested against it that we have found may have less toxicity as far as joint pain. One such drug is called acalabrutinib.

It’s only approved for mantle cell lymphoma right now (start of 2020), but it has been announced that it met a primary end point against chemotherapy in terms of refractory disease, so at some point this year it will be approved for CLL as well.

Is acalabrutinib the only drug for CLL working through a clinical trial or are there more?

There’s another one called venetoclax. Venetoclax is a BCL-2 inhibitor. It’s very different than ibrutinib and acalabrutinib. It’s an apoptotic drug. Apoptosis is the process by which your cells die.

What it does is once it’s in your body, it tells your cells to die. The main problem people have had is tumor lysis syndrome. That is a medical term for when your counts of cells drop so quickly, that it overwhelmed your kidney and renal function. Patients will wind up needing support because their potassium can go up really high or they will need fluids.

In order to minimize the toxicity, we start patients off with a small dose of 20mg. Then they will go to 60mg a week later. Then 100, 200, and 400. Over a process of five weeks, you end up getting to the target of 400mg.

The drug used to only be approved for 17p deletion patients. Recently, it was approved for use in combination with rituximab, a monoclonal antibody, for people with relapsed disease. Now, based on new research from the Germans, it’s been approved for frontline in combination with obinutuzumab for anyone over 65.

The beauty of that combination is that you only have to take it for a year, and four out of five patients will still be in remission two years later. Plus, it’s not chemo.

What usually happens with approvals is they start with relapsed/refractory, then older people or 17p deletion, and then they approve a drug or combination for everyone.

Are stem cell transplants a viable treatment option for CLL patients?

The problem is that the drugs we have for CLL are so good, and the toxicities from a stem cell transplant are so high. We use it only as a last resort.

There’s another type of therapy in clinical development right now called CAR T cell therapy, and it’s really interesting. Your T-cells have the important job of fighting infection.

What they do is they take out your T cells, re-engineer them to recognize leukemia cells, put them back into the patient, and the T cells expand. Now you have an army of T cells who can attack the CLL.

By itself, it really didn’t have good outcomes. When you combine it with ibrutinib, it’s another therapy that works really well. It’s just one more therapy that people are thinking might be better than stem cell transplants. Even though it’s risky, it’s something I would do before I did a transplant.

With transplants, you might be dealing with chronic graft vs. host disease, some skin issues, GI tract problems, or eye problems. There are a lot of things that can go wrong.

Sure, you can be alive, but it’s not a good way to live. With lots of these drugs we have now, many people can live a normal life and practically forget they have CLL.

Are these new treatments safer than chemotherapy in terms of risk for infections?

With ibrutinib, we’ve seen a little bit of neutropenia, but it’s usually later on rather than right up front. It doesn’t correlate with high rates of infection at this time. There have been some reports of severe fungal infections, but it’s in patients that have a high use of steroids.

It’s important to not take steroids with ibrutinib.

With Venetoclax, it can cause neutropenia. What we do sometimes is sometimes we cut down the dose to 200mg and still see the same clinical activity as we would with the 400mg.

There are some people who are young whom I see. If they don’t have any issues or fevers, I don’t do anything even though they live with the chronic neutropenia. It’s a different kind of neutropenia than you would experience with traditional chemotherapy approaches.

Many of these new drugs can cause neutropenia, but the rate of infection is not higher than what we would expect from other drugs. The rate of severe infections is around 15-percent rather than 50-percent with chemotherapy.

Final Words of Advice

In your mind, what would have to happen to find a cure?

We’re working towards a cure. We’re working on new targets. The problem is that it’s a blood disorder, and your blood is everywhere. Sometimes, the CLL is able to hide in some special places. All it takes is one tumor cell to come back and reproduce.

We’re working towards eradicating minimal residual disease (MRD). Many of these drugs have improved these outcomes, but we’re still not at 100-percent.

We can achieve complete remission, but not MRD negativity. By that I mean there’s no evidence of the disease, but there’s still at least one cell hiding somewhere in the blood. We have to find a target.

We’re looking for another one. Right now, we have a couple. One is B cell receptor inhibition. The other is DIABLO process pathway. There are a couple of new targets in clinical development.

When I started in the field, people with 17p deletion only had on average two years of life left. Now, these people are living a decade longer. It’s amazing to see that.

What advice do you have for someone who was just diagnosed with CLL?

The most important thing is you need to educate yourself. It is very life-changing. You’re going to live with this for the rest of your life. Many times, people don’t really want to know about it and just want to listen to their doctors.

The field is changing so quickly that I think the most important thing you can do is to be an advocate for yourself.

We did a registry just to see how doctors were testing markers. Less than a third of doctors within the community and even academic centers were testing for 17p deletion or igHV mutation.

It’s really sad because many of these patients who are getting chemo shouldn’t be getting chemo.

If they are unmutated or have 17p deletion, chemotherapy will not work for them. It’s very important to educate yourself so you know if something doesn’t feel right.

Go get the second and third opinions. In some cases where you are not like your typical patient, your doctor might not have seen some toxicity or side effect before and won’t know what to do, but maybe some different doctor has seen it before and knows what to do.

It’s always good to feel comfortable with your doctor and not be afraid to ask questions.

Thank you Dr. Barrientos!

Ask A Hematologist

Advances in GVHD Treatments and Clinical Trials

Hematologist-oncologists Dr. Satyajit Kosuri and Dr. Shernan Holtan, patient advocate Meredith Cowden, and LLS clinical trial nurse navigator Ashley Giacobbi discuss the role clinical trials play in advancing the GVHD treatment landscape.

...

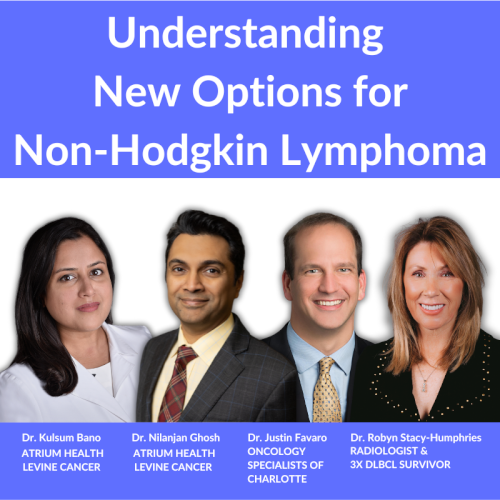

Accessing the Best Care for You or a Loved One: Understanding New Options for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Dr. Kulsum Bano, Dr. Nilanjan Ghosh, and Dr. Justin Favaro discuss the latest advances with 3-time DLBCL survivor and patient advocate Dr. Robyn Stacy-Humphries.

...

Rafael Fonseca, MD

Role: Interim executive director, hematologist-oncologist

Focus: Multiple myeloma, new drug development

Institution: Mayo Clinic

...

Farrukh Awan, MD

Role: Hematologist-oncologist, associate professor

Focus: Leukemias, Lymphomas, BMT

Institution: UT Southwestern

...

Nina Shah, MD

Role: Hematologist-oncologist, researcher

Focus: Multiple Myeloma

Institution: University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)

...