Barbara’s Stage 4 Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Story

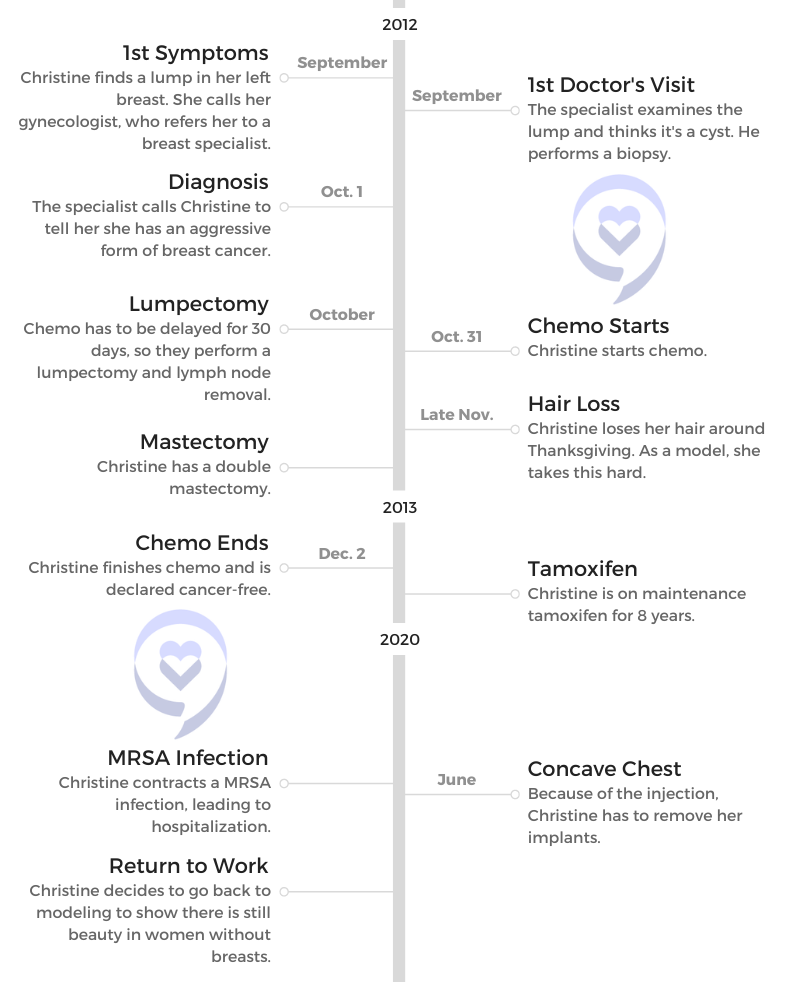

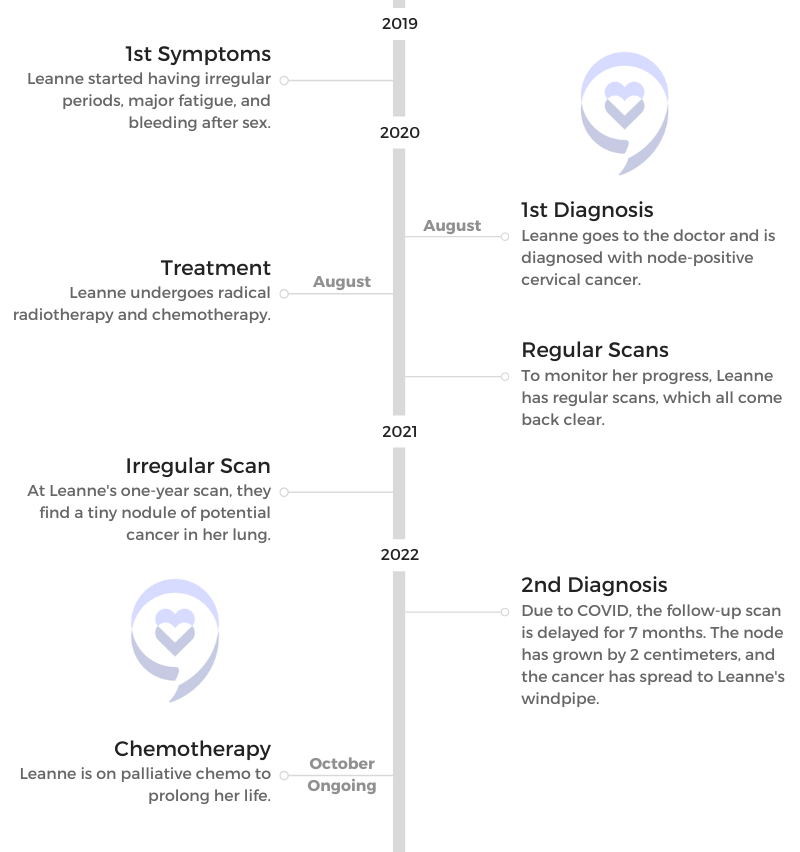

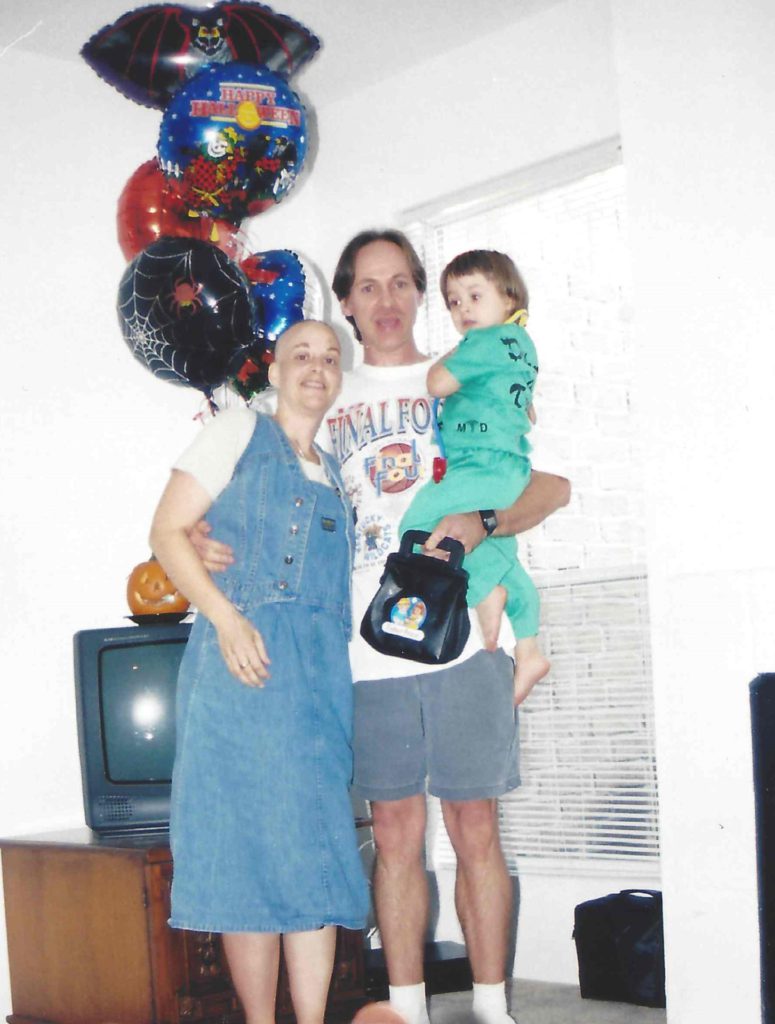

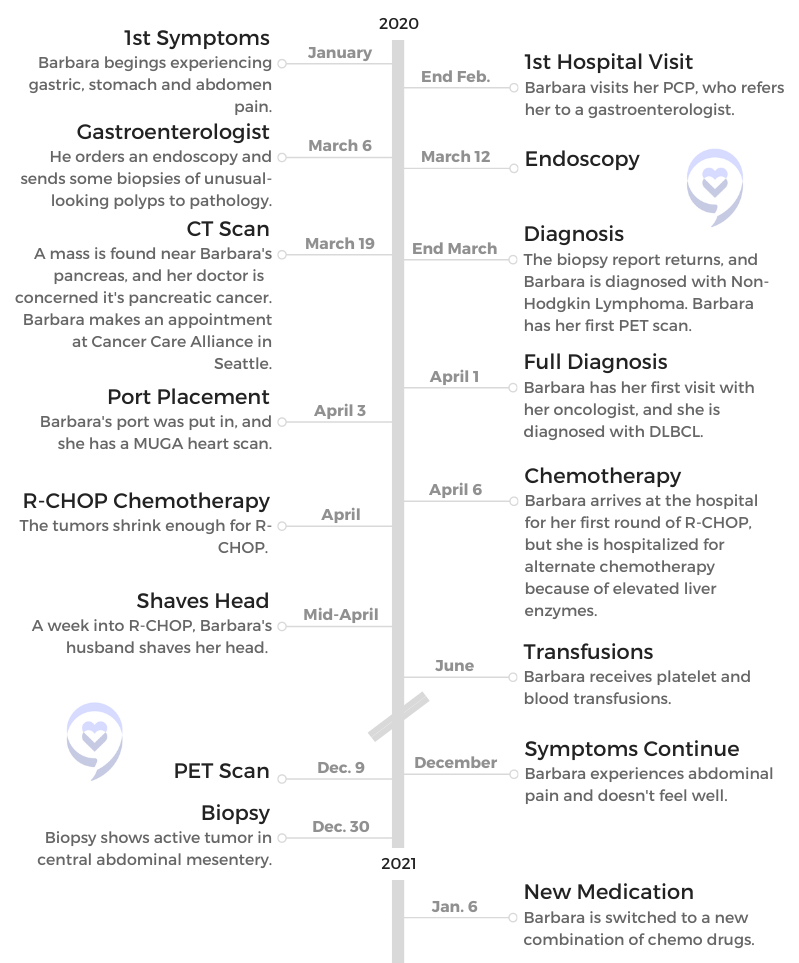

After beating breast cancer 20 years ago, Barbara was alarmed when faced with having cancer again, this time with stage 4 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

She shares her journey of first symptoms, sharing the news with her family and granddaughters, and undergoing treatment.

You can read her in-depth story below and watch our conversation on video. Thank you for sharing your story with us, Barbara!

- Name: Barbara R.

- Age: 72

- 1st Symptoms:

- Abdominal pain

- Gastric pain

- Diagnosis:

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- Treatment:

- R-CHOP

- CAR T-cell therapy

- Study drug CYT-0851

- VIDEO: 1st Symptoms and DLBCL Diagnosis

- VIDEO: CAR T-Cell Therapy and Radiation Therapy

- VIDEO: Clinical Trials

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

VIDEO: 1st Symptoms and DLBCL Diagnosis

Introduction

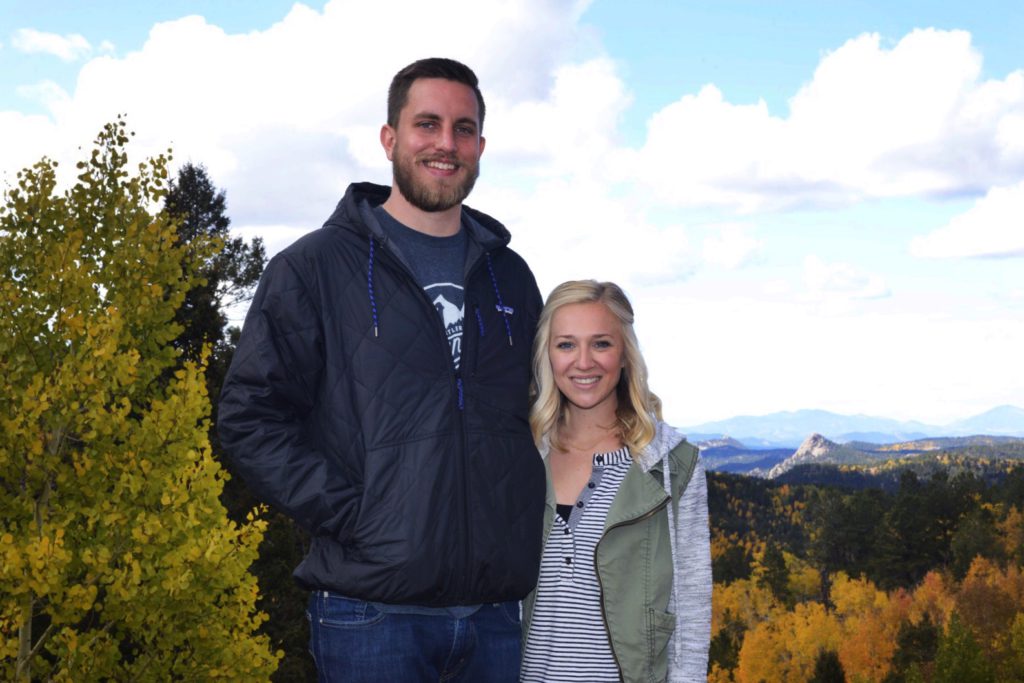

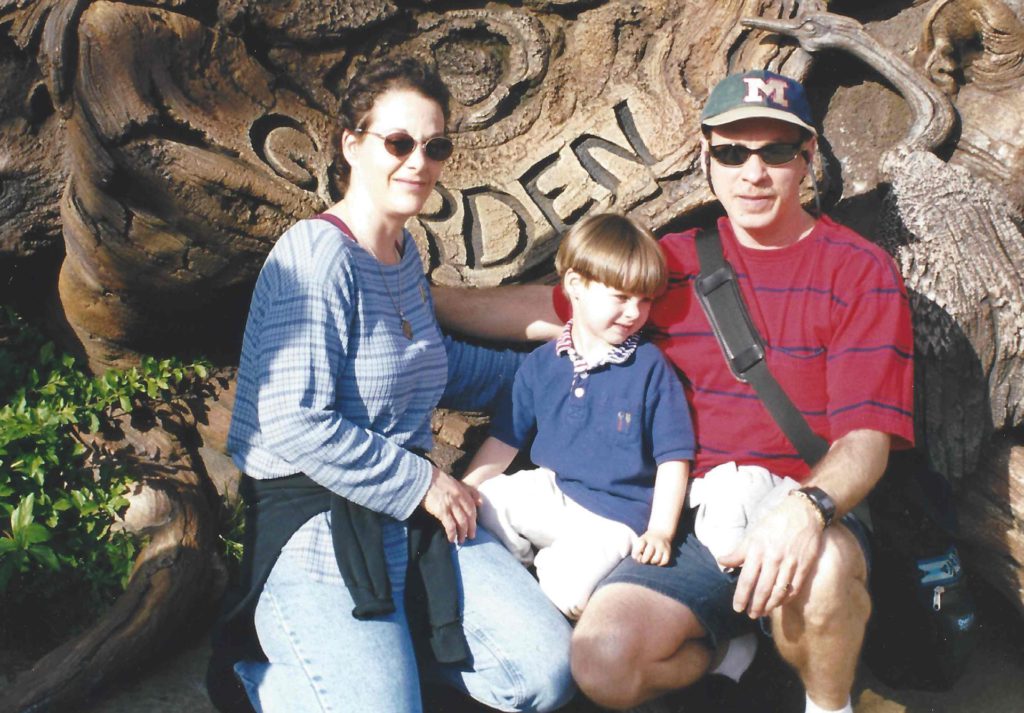

Tell us about yourself

I’m 72 years old. I had breast cancer 20 years ago. I’m a really active person and avid gardener, and I sailed for 42 years. I have 2 little granddaughters, lots of friends and family, and a wonderful husband.

What were your first symptoms?

They were gastric pain, stomach pain and abdomen pain. I brushed it off. I thought, “It’s just acid stomach. Whatever I ate isn’t agreeing with me.” I had some other health issues going on at the same time, so it just got set on the back burner for probably too long.

Finally, I went to my PCP doctor, who referred me to a gastroenterologist to get to the bottom of it because it was really increasing worse and worse to the point where I couldn’t get in a comfortable position. It just went beyond a stomach ache, so I knew something was wrong.

How did your gastro specialist communicate the results of your endoscopy and biopsies?

I think it was right after the endoscopy. He said, “Everything went fine. I did see a polyp that I biopsied. It’ll take a few days, and I’ll get back to you.”

I thought, ‘Okay, I got through the other cancer. I’ll just get through this one.’ I was just sort of ready to take it on because that seemed like the only choice I had.

Apparently, it took more than a few days, but he was concerned because he ordered a CT scan after that, and there was what looked like a mass on the head of my pancreas. That was alarming enough to call me and say he suspected pancreatic cancer, which alarmed me and my family.

I decided I needed to go to a good cancer center. I called Cancer Care Alliance in Seattle, and I set up an appointment and a team for the pancreatic cancer. Then just a few days before my appointment, that gastroenterologist called and said, “Since we have the biopsy report, it’s not pancreatic cancer. You have non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.”

The DLBCL Diagnosis

How did you process the possibility of having cancer again?

I was alarmed. I knew the severity of pancreatic cancer, and I just wanted to get into treatment right away the next day. The Cancer Care Alliance actually pushed me right into the system, and then as soon as they found out that it was a different diagnosis, they switched me to the hematology department.

I was not totally unhinged. I thought, “Okay, I got through the other cancer. I’ll just get through this one.” I was just sort of ready to take it on because that seemed like the only choice I had.

Receiving the DLBCL diagnosis

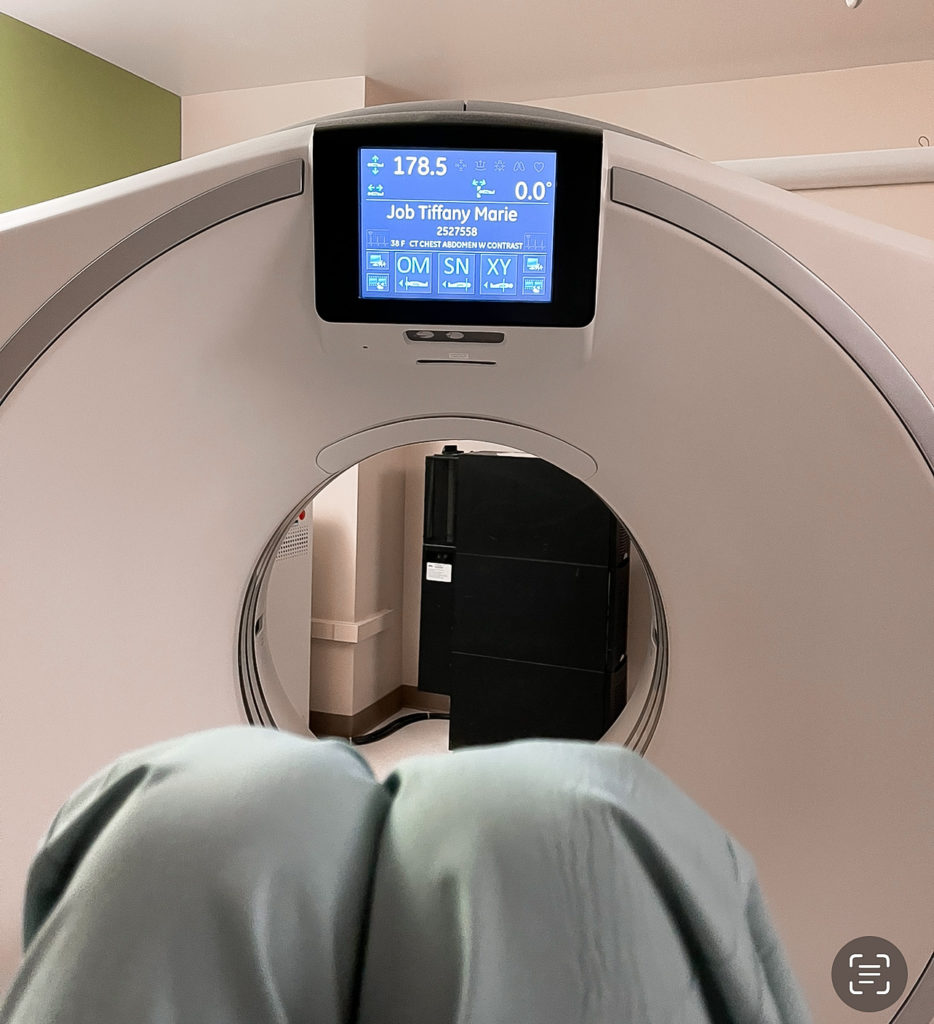

The oncologist that they set me up with at the cancer center ordered a PET scan before I even saw him. Just a couple of days later, I had my appointment with him. He went over what the cancer was.

It was stage 4, but you can treat that blood cancer at stage 4. He also went over the R-CHOP. “This is what we’re going to do first.” I just got it in my head that okay, we’ll do this.

»MORE: Reacting to a Cancer Diagnosis

Did you think about getting a second opinion?

For one thing, I knew that was probably the best cancer center in the Seattle area. My daughter-in-law had worked with them for quite a few years in the hematology department, and she was confident. She said, “This is the place you need to be,” so I didn’t really question that.

Treatment options for DLBCL

It was more or less, “R-CHOP is the way to go. This is what we do. We start here.” He didn’t say that this was the only option. He just said this is where we’re going to start.

I was just accepting the diagnosis and treatment, and I was confident I was in good hands.

Emotions From the Diagnosis and Treatment

How did you break the news to your family and friends?

My husband was with me for the appointment, and I believe my daughter-in-law was on speakerphone. She did that for my first appointment. I have a small family, just a son, his family and my husband. I have a brother, and my husband has a brother. We waited for a while to discuss that with them until we knew more about what everything entailed. I didn’t want to alarm everybody. With my friends, I didn’t go into that for a while.

»MORE: Breaking the news to loved ones

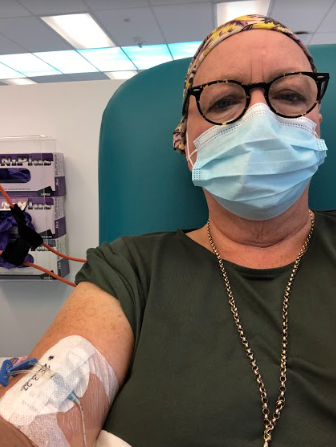

Getting a port placed

There’s always fear about an invasive procedure. I’ve been through it before with my breast cancer. I’m a really calm person. I know it’s hard, but my advice is just to try not to be overly anxious.

They give you painkillers. It’s really a fairly easy procedure. It’s right under your skin and doesn’t take long, so I didn’t have a problem with it.

What was your reaction when they said R-CHOP was too dangerous because of your elevated liver enzymes?

That actually was scary to me. My husband had dropped me off. It was going to be a long day. We live about an hour away, so he was going to go home. When they told me they had to hospitalize me, it was almost a panic reaction, which I never do. But I had no car. I had no bag with anything I needed for the hospital.

I wasn’t prepared mentally for that at all, and COVID was really strong then. Nobody wanted to be in the hospital. It was scary. They assured me, “We have our own ward. There’ll be somebody right there to take you,” which all was true. They arranged for me to have a ride, but there was just that moment of panic. They were putting me in the hospital. I wasn’t mentally prepared for that at all.

How did you get through the isolation and hardest moments?

The hardest times were felt by everybody. Everybody was isolated in the beginning, so I didn’t feel like I was affected any more than anyone else. As the months went by, especially when people got their COVID vaccines, I was told that my immune system might not react well to the vaccine. Then I started feeling more isolated.

My husband did all the grocery shopping and did all the errands. Actually, to some point, it’s still that way. I have gotten a second set of COVID vaccines and Evusheld prophylactic shots, which makes me feel a lot better.

I did see my immediate family. My daughter-in-law was vaccinated right away because she worked in healthcare. I just had the few people, after they got their vaccinations, whom I would see but not in public places.

DLBCL Treatment and Side Effects

How did your first cycle of treatment go?

It was alternate drugs that they had abandoned because R-CHOP was better. But since they couldn’t do it and the side effects meant they had to watch more closely, that’s why they hospitalized me. I think I was there a week.

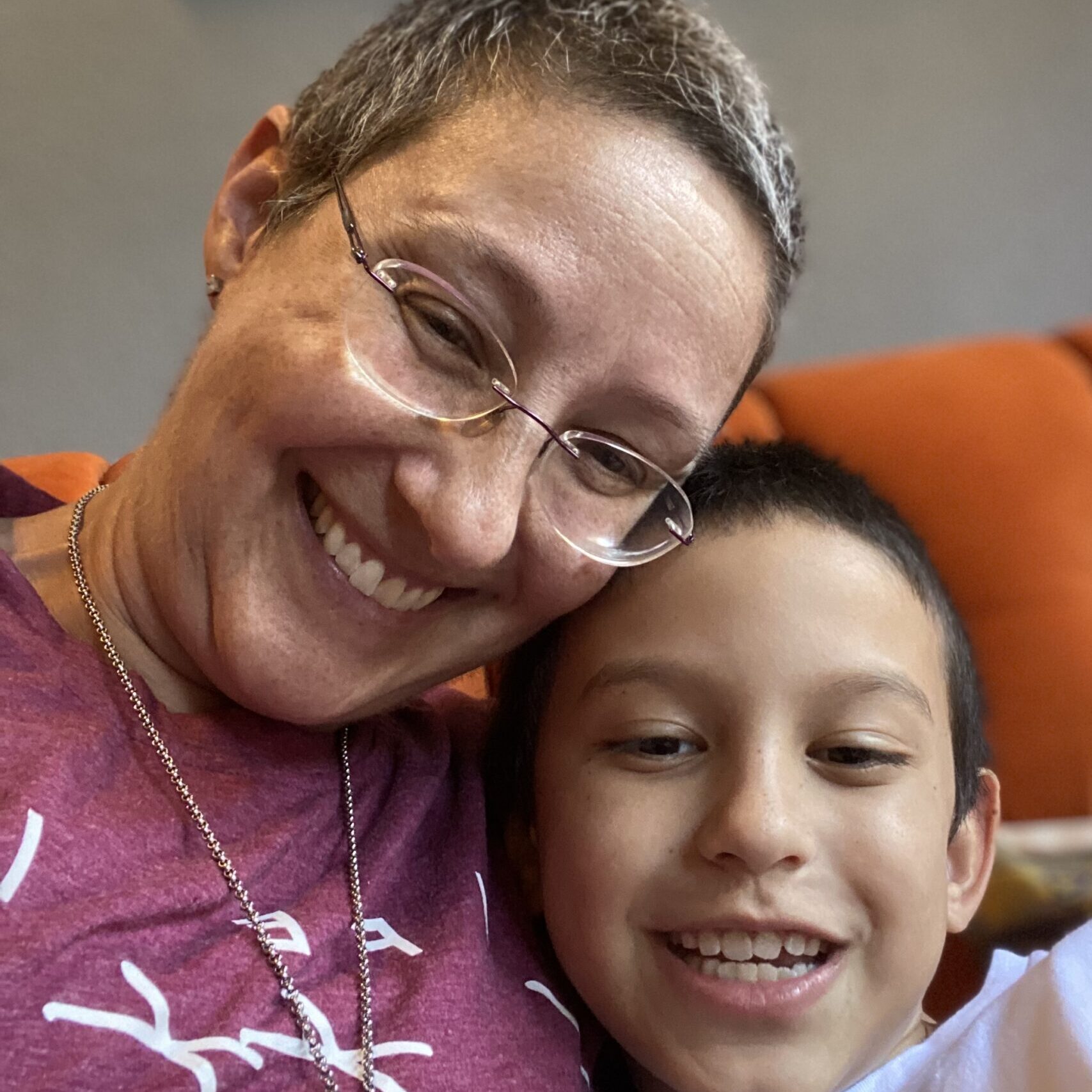

The one thing that bothered me more than the first time was my little granddaughters, because it’s hard to hide what is really going on with Grandma.

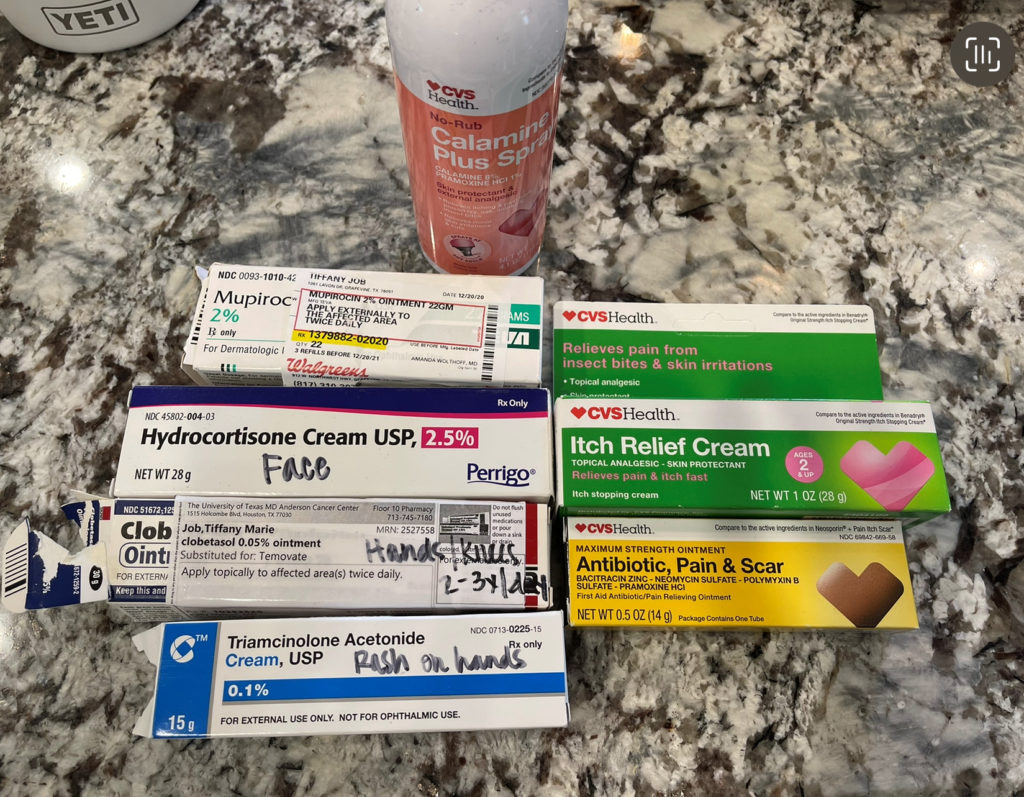

What were the side effects of R-CHOP?

I experienced nausea. Then I got the nausea pills down so that I knew when to take them. It just takes experimenting, and I think it’s different for everybody. That took a while. I remember getting dehydrated and having to go to the clinic for a fluid IV. There were rough spots with the nausea and vomiting.

Once that was under control, my appetite went down, but I did eat. Then I think as far as others, I had a side effect with skin flaking. I don’t know if anybody else has had that, but it was just extraordinary dry skin. I’d never experienced anything like that. I was taking oil baths, and then it just went away. I’m sure that was a side effect, too. But other than the nausea and getting that under control, I think I did okay.

»MORE: Managing Chemo Nausea

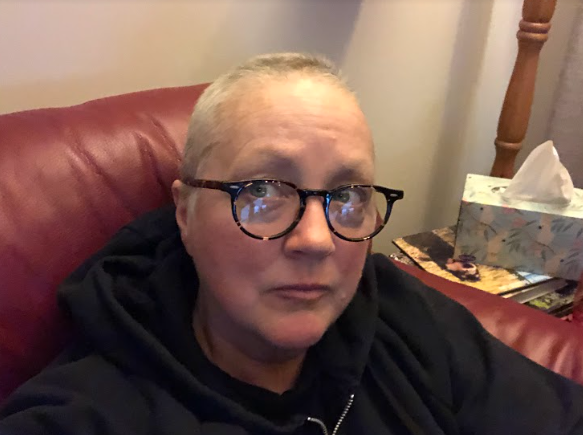

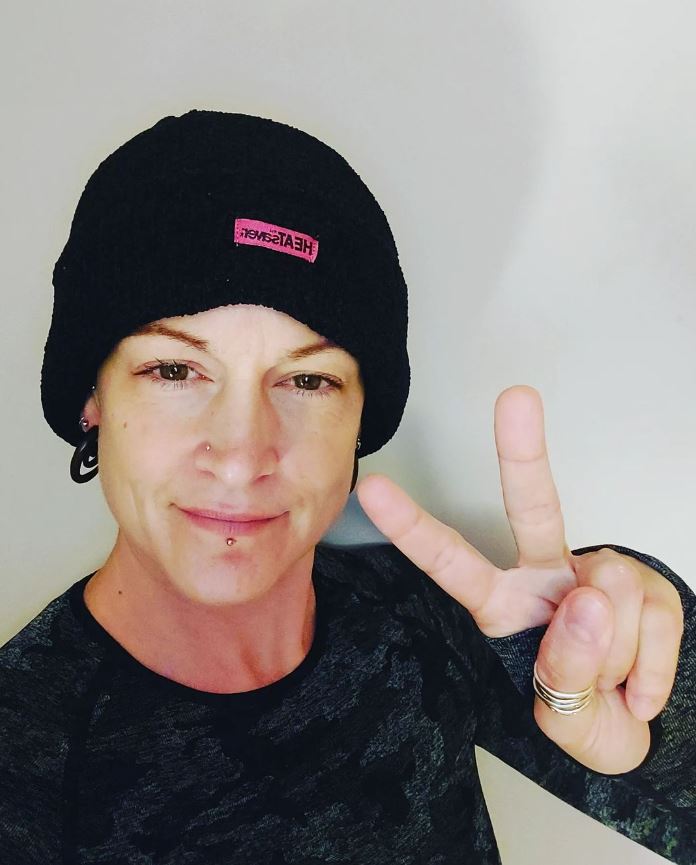

How did you deal with the hair loss?

It started looking dry and ugly, and then it was just hairs on your clothes and on the couch. I said, “Okay, let’s just get rid of this.” Since I had gone through it before, it wasn’t so traumatic. It was in the spring and summer, and I had a lot of really nice hats.

The one thing that bothered me more than the first time was my little granddaughters, because it’s hard to hide what is really going on with Grandma. At one point, I was taking care of them, and they had some little princess wigs.

I said, “I want to try one of your wigs.” I took my hat off, and they hadn’t seen me bald before. The little one was a little alarmed. I said, “I look pretty good in your wig, don’t I?” They started laughing and we had a good time, so we got over that.

As far as my friends and my family, I was embarrassed in front of them. The thing about losing your hair that bothers me is that it seems like it takes so long to grow back! When I was ready for it to grow back, I just wanted it to grow back. But it’s not overnight. It takes a while.

»MORE: Hair Loss and Regrowth

How do you talk to young children about cancer?

I think my daughter-in-law handled it best. If they asked a question, we would answer. They would stay all night with us once in a while. It was just kind of common to say, “Grandma’s got to lie down.”

Kids are not focused. They’re focused on themselves: when they can go play outside, if the sun’s out, what’s for dinner and can they have a treat?

We didn’t go into any details. They knew that their mother worked at a cancer center and that I was going to that same cancer center. They were 4 and 6 when I got sick, and they didn’t ask a lot of questions. We didn’t go into any details unless they did.

»MORE: How to Talk to Kids About Cancer

VIDEO: CAR T-Cell Therapy and Radiation Therapy

Next Steps

In December, a PET scan and biopsy showed an active tumor in your abdomen. How did you react and process this?

My oncologist was doing periodic PET scans. In December, I started again feeling abdominal pain. At first I thought it was just stomach cramps. I knew better. I just didn’t want to deal with it.

Then when the PET scan showed that it was positive there and that we needed to try another course of treatment, I guess my biggest reaction was disappointment. I was just really disappointed. I wasn’t losing hope, but on the other hand, the reality of things kind of hit me.

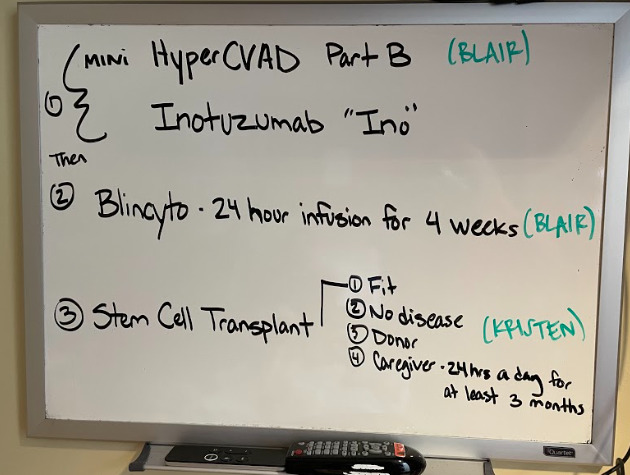

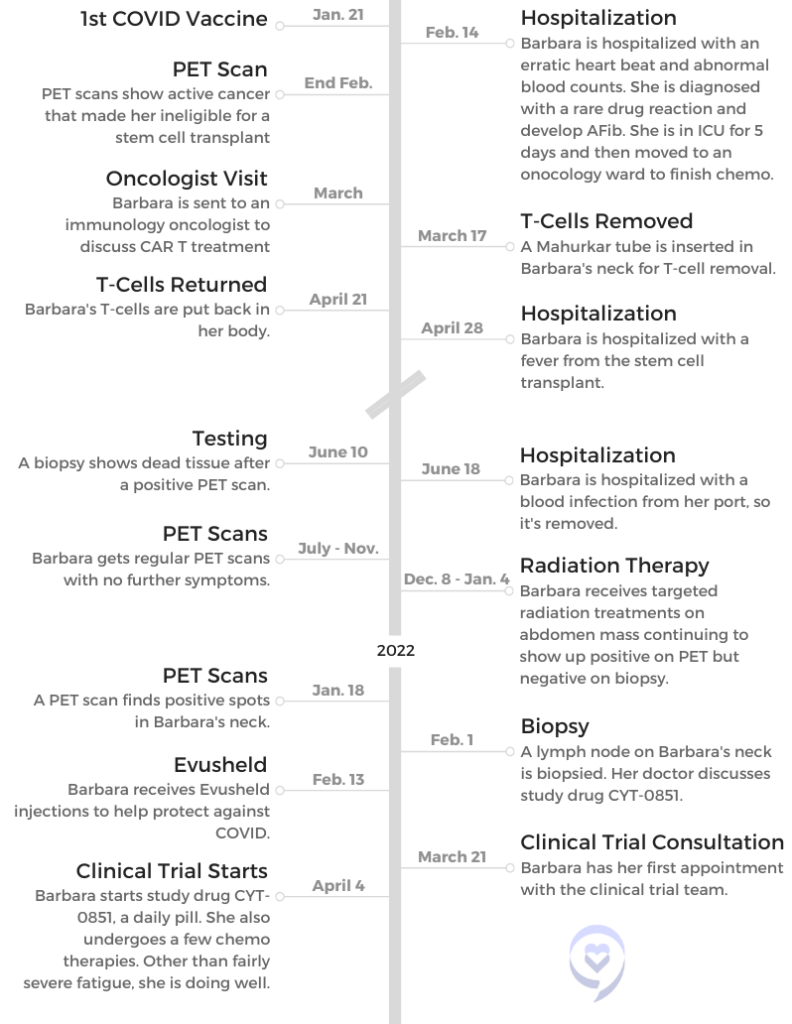

What did your hematologist-oncologist say was the next step?

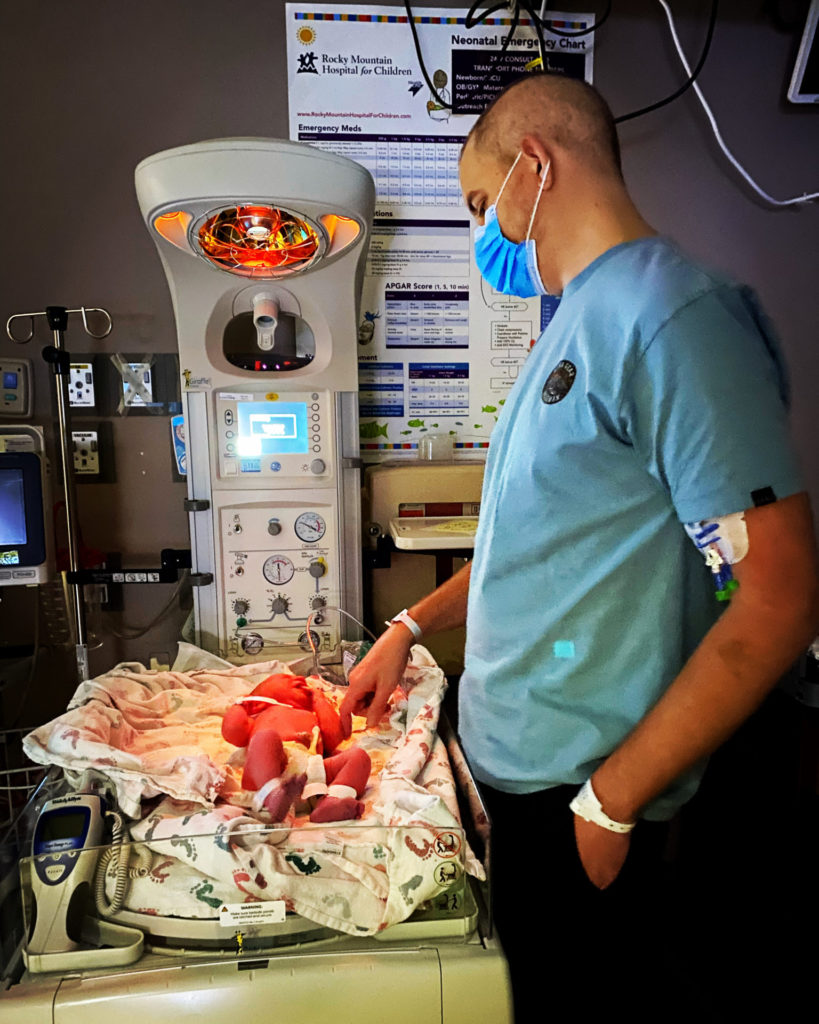

They thought the next step would be stem cell transplant, and they gave me some chemotherapy. They do that before stem cell. There are protocols with getting a stem cell transplant, and you need to be actually cancer free before you do get the transplant.

I didn’t reach that goal, so they offered me the CAR T, which they were actually more enthused about. It’s just that the medical community and insurance want you to go through stem cell transplant first. Since I didn’t qualify, my doctors were excited that they could offer me the CAR T.

CAR T-Cell Therapy

How did your doctor explain CAR T to you?

He described it pretty thoroughly, and I did have some background in hematology. I was a laboratory medical technician for my career, so I understood T-cells, antibodies, the basics of blood cells.

It made sense. It seemed astronomical that they had come up with this solution, all the studies and the work that went behind it. The whole idea of it was pretty amazing.

Actually, the same cancer center has a Fred Hutchinson Research Center, and they were heavily involved in CAR T. Jeff Bezos actually donated the money for the CAR T suite and their own doctors. I sort of left the care of my regular oncologist, and I was now in the care of the CAR T research scientist oncologist.

»MORE: Immunotherapy FAQ

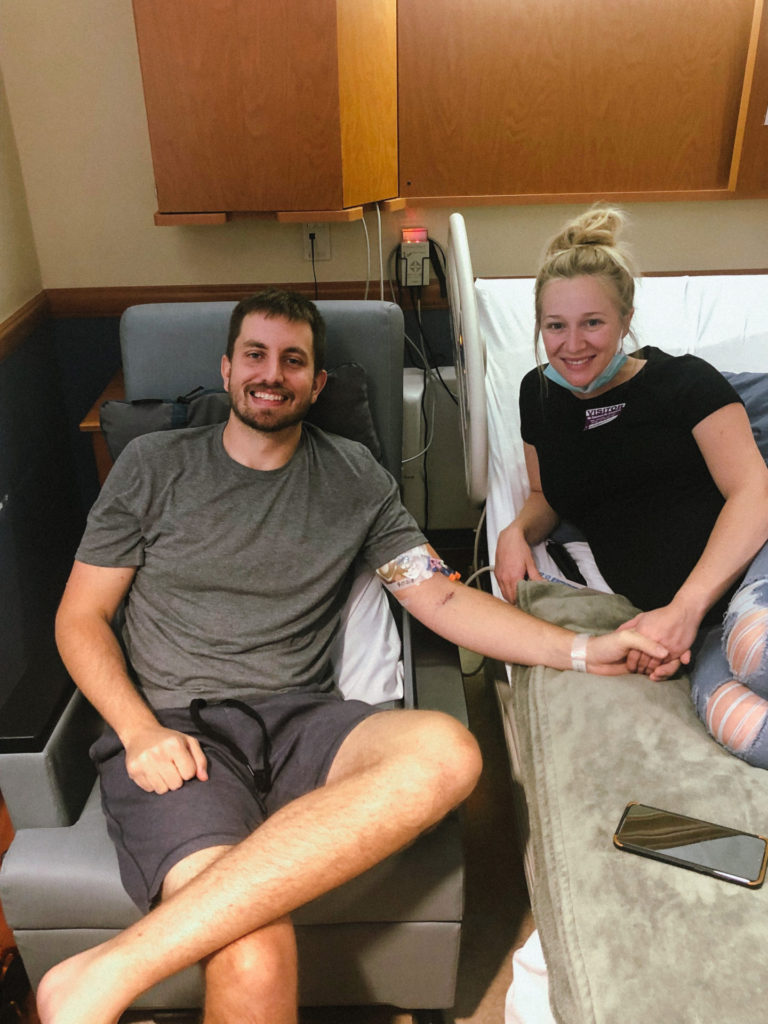

Can you explain the CAR T process?

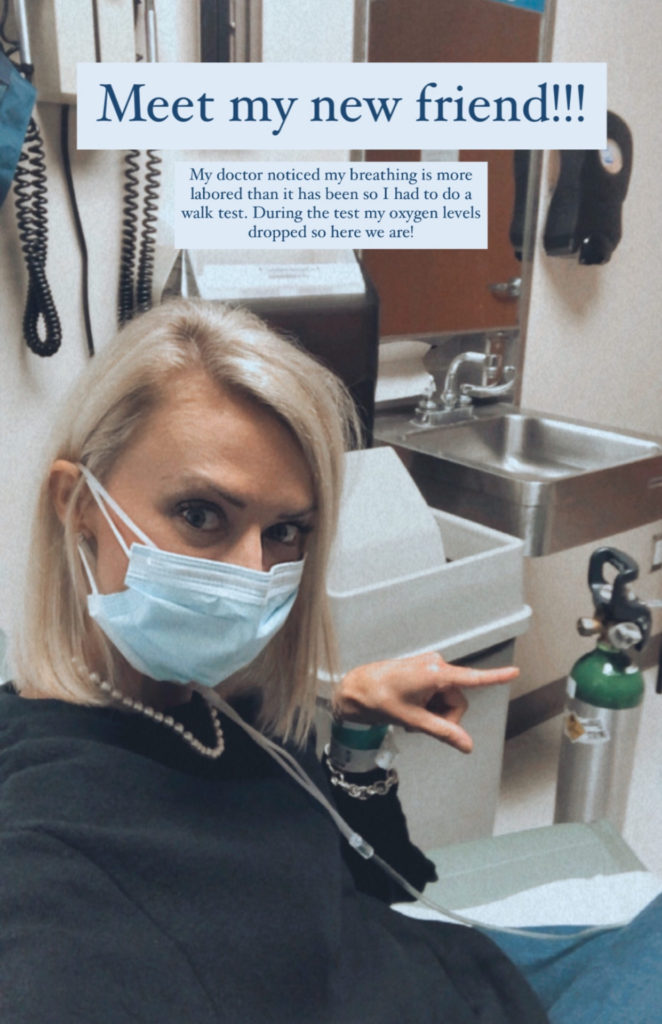

First of all, they go over side effects very thoroughly, which is a little bit scary because there can be some life-threatening side effects. The fact that we lived more than an hour from the hospital required us to live closer, and it was quite an expense to rent an apartment in Seattle for a month.

You had to be 15 minutes from the hospital — which would have been University of Washington — because as soon as you get a fever, they want you there right away. It’s life-threatening.

I think it was like 100.3 or something. I can’t remember exactly. It was what you would consider a low temperature, but if you got that temperature, you’re in the emergency room. That happened, and I spent a week in the hospital there. They closely monitored me. Of course, that’s after I got the T-cells.

Removing cells

I need to back up a little bit to the process of removing your T-cells. They can do it with veins in your arm if you’re young, healthy and have huge veins in your arm. Unfortunately, I didn’t.

They put a tube in your neck, which again, was a procedure but not a really painful procedure. It was short. It didn’t take long. All I can say about it is it was awkward, because you’ve got this tube sticking out of your neck. You have to have it there like overnight. I just slept on the couch with pillows propping my head up and managed to get some sleep.

It’s sort of like a kidney dialysis, where they transfer your blood through a machine. They actually take your blood cells out, they go through a machine, it removes your T cells, and then it puts your blood back in. It’s an all-day process.

The nurse that does it is highly trained. It’s a complicated process. I didn’t have any problem with it. It’s just that it took a long time, and you were hooked up to this machine so you couldn’t leave. I think they did bring me a bedside commode at one point, but it’s not like you can get up and go to the bathroom or anything.

Returning cells

Then it takes quite a few weeks. They sent my cells to New Jersey, where they were processed. I think it took quite a few weeks. I can’t remember exactly, like at least 4 weeks. Then they came back. It’s just a little tiny bag, and they put the cells back in.

It’s just an easy process there. They had removed the tube in my neck. They put it in the afternoon before removing my cells, so that’s why I had to come home with it. Then the next day, they just took it out. For putting the cells in, it was like an IV drip, a little tiny bag.

It was at least 6 hours to remove the cells. Receiving the cells back was maybe half an hour. It was no time at all.

Maybe it won’t change anything. Maybe it will. So I went ahead and did it.

Aftercare

After you receive your T-cells, you need to be within 15 minutes of the center for a month. You see the CAR T team Monday through Friday during this time, and they do vital tests and COVID tests once a week.

They did a mental cognitive test and asked how I was feeling. They were short visits, but they wanted to see you in person.

For the mental cognitive test, you wrote the same thing down every day. You’d think I would remember that, but I can’t. You just wrote the same thing every day. You could see it written, and you had to write underneath the same phrase.

Hospitalization for fever

We were at our apartment, and my husband was just fanatic about checking my temperature. He said, “We’re going.” Arrangements had been made for when I got the temperature, and it all went really smoothly. They put me up in the oncology ward at the hospital.

While I was in the hospital, I had a couple of days of chills. I think my temperature probably got higher there, because I remember the chills really bad, and they subsided. They did keep me there for 7 or 8 days.

They monitor you very closely. It’s a little boring to be in the hospital for 7 or 8 days when I didn’t really feel that bad once the chills and the fever went away. It was comforting to know that they were watching me that closely.

»MORE: Leaving the Hospital: Emotions & Support

Radiation Therapy

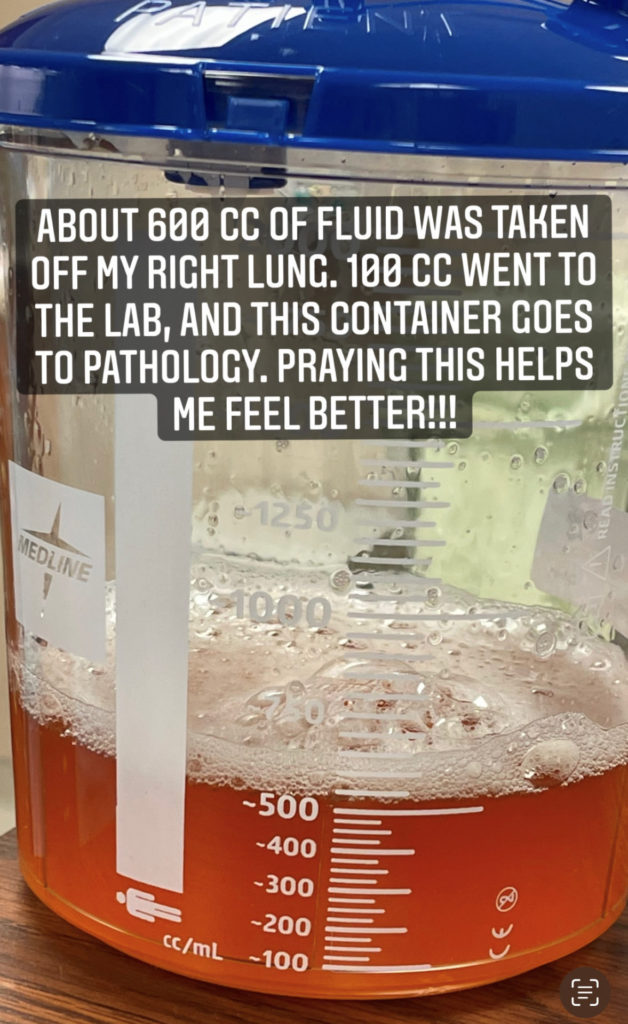

Your PET scans were returning positive, while your biopsies were returning negative. What was going on?

The doctors were wondering what was going on. They couldn’t give me an answer. They couldn’t give themselves an answer. Apparently, the CAR T oncologist said, “Sometimes you can get a false positive with CAR T.”

It’s a fairly new cancer procedure. They don’t know everything about it, and they admit that. They were a little hesitant.

I think I had 2 biopsies. I was feeling fine, and I couldn’t even feel what was still positive. At one point, my doctor said, “Let’s just see in 6 months.” I was thinking that’s great, but then he called just before Christmas and said he just couldn’t get it out of his mind.

He was a little concerned and thought, “What if I’m not doing the right thing?” He and his colleagues had spent a lot of time thinking about it, and they decided that I should go through radiation therapy for the month of December, which kind of ruined my Christmas plans.

I was disappointed again, and he gave me a choice. “This is just how we feel about it. It’s up to you.” I kind of don’t like when they do that because those are hard decisions.

My husband and I talked about it. We thought if they are wondering and worried, then it kind of makes me feel the same way. Like he said, maybe it won’t change anything. Maybe it will. So I went ahead and did it.

He didn’t have any answers because they were confused about the biopsy report compared to the PET scan report. They were just trying to cover all the bases.

What went into your decision to get radiation therapy?

I just wanted to get on with my life. On the other hand, I thought, “I don’t want to just shorten my life. How do I know?” We just don’t know. I tend to be more cautious. We did discuss it. I think my husband and I made the decision that night.

He was getting worn out driving me to Seattle every day, because we needed to get in the commuter lane and it was winter weather. Oh my gosh, we just didn’t want to do that. We just knew the possible consequences versus maybe no consequences. It was hard to do.

How was your experience with radiation?

The worst part was actually getting there. Like I said, it was winter, and traffic in Seattle is not pleasant. We’re north of Seattle. As far as the radiation, you just get on a table, they line you up, and it doesn’t take long at all. Because it was in my abdomen, I had side effects like diarrhea. Again, I dealt with that with the anti-diarrheal medicines, but that was a little unpredictable and unpleasant. I also got fatigue from that.

»MORE: Radiation Therapy

How did you deal with the anxiety of waiting for results?

I think it was harder on my husband, to tell you the truth. You just kind of picture yourself where things are fine. And then all of a sudden, you’re picturing yourself like, “This is it.” It’s like a teeter totter. You’re down, you’re up, you’re down, you’re up. It’s like you just can’t seem to be in the middle.

I’m a realist. Tell me everything. I can handle it. If it’s going to be this way, it’ll be that way. But I do set myself up for the worst. My husband says I need to be more of an optimist. I always have a plan B, but C-D-F plan — how many plans can you have?

»MORE: Coping With Scanxiety

VIDEO: Clinical Trials

Needing Further Treatment

Learning the results of the lymph node biopsy

I wasn’t too surprised. I just thought, “I’ve been through all these things.” Then I got the impression this is at a simmer. Let’s just try to keep everything at a simmer. It’s the whole attitude of my oncologist and my daughter-in-law, who’s an oncology nurse. It’s the realization that possibly that’s all they can do. That’s okay. We’ll just see.

They did a PET scan after the biopsy. Actually, I got that PET scan result from my radiation oncologist because I had a Zoom meeting set up with her for a month after my radiation. We had both gotten the report at the same time. It was on my MyChart.

She had just seen it. She told me that actually there were multiple spots all through my abdomen of positive lymph. That’s when my oncologist gave me some options for further treatment, and one of them was a study drug.

What options did your oncologist offer?

One of the options was a repeat CAR T. He says it’s not like the original CAR T. Then he offered me the study drug that he did. I think there was one other. I can’t even remember it.

With the CAR T, I just didn’t feel like my husband and I had the strength to go through all that again and rent another apartment. We decided together that we’ll try the study drug, and my oncologist said he was guardedly optimistic. That’s better than, “I’m sorry. I can’t offer you anything.”

The study required another biopsy, which I just had yesterday on the lymph gland. I imagine it’s going to be the same as the one I had in February, and then I think that they’ll do a PET scan in June.

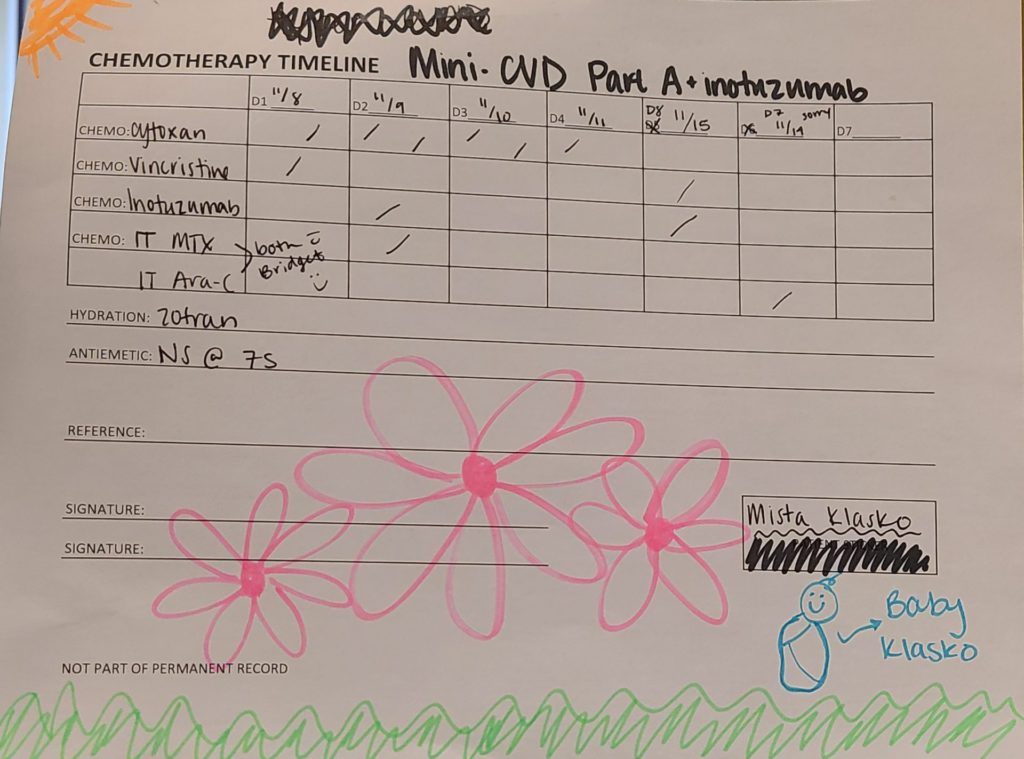

Clinical Trial

Clinical trial process

There are 7 chemotherapies once a month. I’m going to have my second one on Monday. There’s lots of blood drawing for the study, like timed blood draws. There are a lot of things that aren’t really the therapeutic side of the treatment, but more the study side, which I’m willing to do.

I’m having a hard time with that because I just feel like I’m a shell of myself.

The blood draws are tests that the study needs to do after the chemotherapies. That sort of thing. I do get blood tests where they monitor my red cells that my oncologist sees — my chemistry test, my kidney, liver function, all that. My doctor keeps tabs on that. The rest of the blood tests go to the study.

There’s once-a-month chemotherapy, and then you take a pill every day. You have to fast 2 hours before the pill and 1 hour after.

»MORE: Clinical Trials in Cancer

How do CAR T and the clinical trial compare? Do you wish you would have done CAR T again?

I don’t really wish I had done CAR T again. This gives me more freedom: the pill every day, the once-a-month chemotherapy. It’ll be 6 months or 7 months, so I need freedom in my life right now. I just need to not be so tied down to cancer.

I feel like hopefully it could work, but if it doesn’t, at least I got some freedom to live a life. It’s really hard when you’re just tied to a cancer center constantly. It takes a toll on my husband with all the driving and the waiting.

We’re in our 70s. I’d have a completely different attitude if I was 20 to 30s. I feel like whatever happens, happens. It’s been kind of a long haul, but I’m just hoping that maybe my experience is like a handbook to somebody else.

None of the procedures they do are really painful. I got a blood infection from the port, and when they took that out, that was painful, but it was because it was so infected in that area. But all the other procedures I had, I really didn’t have a problem. I had to have one therapy for weeks and IVs and all that. But you just get through that kind of side effect.

Continuing to Live Life

Dealing with extreme fatigue

I’m having a hard time with that because I just feel like I’m a shell of myself. I have a greenhouse. I walk out there. I’ve planted seeds. I have a chair out there I sit in. It’s just not who I am. That’s the problem. It’s not who I am. I’m just trying to cope with the fatigue.

You just want to make the best out of everything, no matter what it is. At some point, we all have to face an inevitable. But just that the life you led is the best one you could have done, even if you were sick at the end.

My red blood cell count’s low from the chemotherapy, they said. I’m hoping they can help some way to get me a little more energy. I push myself. I really do. Otherwise, I think if you didn’t push yourself, you would just be in bed all day. I can’t do that. I feel better when I push myself, and then I take a nap.

It’s springtime here. That helps. Everything’s blooming and growing, so the garden helps my spirit. Even though I can’t take a walk like I used to, even if I walk around the yard, it’s like I’ve done something. I’ve looked at something that made me feel good.

We did hire a housekeeper because you can’t keep your own house up, and my husband’s doing everything. We decided that there are things we need to do to make our lives easier.

»MORE: Cancer Treatment Side Effects

How are you doing now?

You just want to make the best out of everything, no matter what it is. At some point, we all have to face an inevitable. But just that the life you led is the best one you could have done, even if you were sick at the end. I have a lot of inspiration, my grandkids and my husband, but there are sad times. There are really sad times.

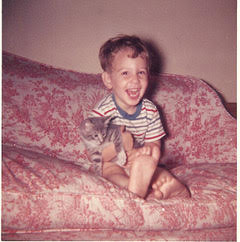

My husband tells me to quit crying, and there’s always humor in life. That’s what gets you through — laughing or looking at something that seems silly. I think I’m going to get a cat now. We haven’t had a cat for a while, and I decided I wanted one again.

»MORE: Inspirational Quotes From Cancer Patients

Inspired by Barbara's story?

Share your story, too!

More Diffuse Large B-Cell Stories

Ashley P., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptoms: Feeling like holding breath when bending down or picking up objects from the floor, waking abruptly at night feeling “off,” one episode of fainting (syncope), presence of a large mass in the breast

Treatments: Chemotherapy, bridge therapy of chemotherapy and radiation, CAR T-cell therapy

Melissa B., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Symptoms: Lump in the left breast, persistent rash (started near the belly button and spread), intense fatigue and energy loss

Treatments: Chemotherapy (R-EPOCH), Neulasta, radiation therapy, surgery (to remove scar tissue and necrosis), autologous stem cell transplant

Jen N., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4B

Symptoms: Blood-tinged phlegm, whole-body itching, shortness of breath, lump near collarbone, night sweats, upper body swelling, rapid weight loss

Treatments: Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, lumbar puncture, autologous stem cell transplant

Jim Z., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Symptoms: Sudden and severe head and neck swelling, purplish facial discoloration, bulging neck veins

Treatments: Surgery (resection and reconstruction of the superior vena cava), chemotherapy