The Latest in Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatments

How to Talk to My Doctor About Options

Edited by:

Katrina Villareal

The Hodgkin lymphoma treatment options live discussion took place in August 2023, hosted by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Imerman Angels, and The Patient Story.

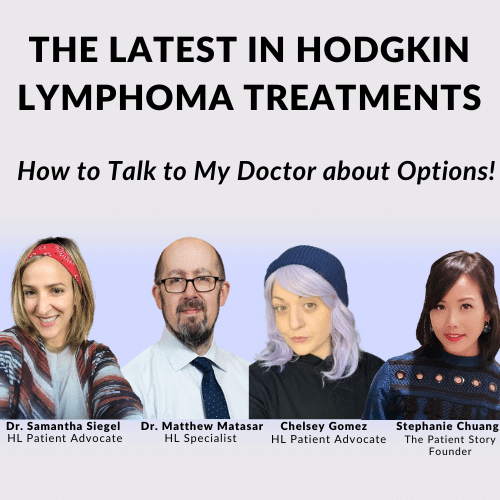

Sharing from real-life experience, the panelists were Stephanie Chuang, founder of The Patient Story and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivor, Dr. Matthew Matasar, Hodgkin lymphoma specialist at Rutgers Cancer Institute, Dr. Samantha Siegel, both a doctor and Hodgkin lymphoma patient, and Chelsey Gomez, Hodgkin lymphoma patient advocate and artist behind Ohyouresotough.

The discussion covered an overview of Hodgkin lymphoma, standard, and emerging first-line treatments, options for relapsed/refractory patients including immunotherapy and stem cell transplants, managing side effects, the importance of doctor-patient relationships and shared decision-making, and key takeaways about community support and focusing on the quality of life during and after cancer treatment.

- Introduction

- What is Hodgkin lymphoma?

- Changes in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma

- First-line treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma

- Role of radiation in Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

- Side effects of Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

- Immunotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma

- BV-AVD vs. ABVD as first-line treatment

- Treatment for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma

- Sam’s Hodgkin lymphoma relapse

- Stem cell transplant

- Chelsey’s Hodgkin lymphoma relapse

- Chemotherapy & immunotherapy pre-transplant

- Determining the sequence of treatment

- Long-term post-treatment side effects

- Shared treatment decision-making

- Finding a Hodgkin lymphoma specialist

- Final takeaways

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, everyone! I’m very excited to have everyone to join us. We’re hosted by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Imerman Angels, and The Patient Story. We have an incredible group of panelists tonight.

I’m a non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivor, founder of The Patient Story, and first and foremost, a patient advocate. The Patient Story was born out of my own experience with cancer. At the time, as a patient, I was looking for humanized answers for what my life with cancer would look like.

Fast forward to today, The Patient Story has hundreds of in-depth conversations and stories with cancer patients, care partners, and top medical experts in video and across our platforms. You can find us on ThePatientStory.com, YouTube, and social media channels. The goal for us is to help navigate people after getting that diagnosis.

We’re proud to partner with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society or the LLS, which is the world’s largest nonprofit health organization dedicated to funding blood cancer research. They also provide a lot of education and services and that includes their information specialists who are just one call away to help with your questions. They also have financial scholarships and we’ll talk about that at the very end as well.

Last but not least is Imerman Angels, a wonderful peer-to-peer support group program. I used Imerman while I was a cancer patient and they will connect cancer patients and caregivers with mentor angels. They will use things like age, gender, where you live, and experiences to try and make that match.

We also want to give a special thanks to Seagen for supporting our educational program and allowing us to really do the work that we want to do in true patient education, connection, and space and provide it for free; that’s really important to us.

We want to stress that The Patient Story, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and Imerman Angels all retain full editorial control of the entire program. A reminder that this is not meant to be medical advice or a substitute for medical advice. It is educational and we’re hoping that you’re able to take away great information tonight back to your own doctors and healthcare team.

Introduction

Stephanie: First up, Dr. Matthew Matasar, someone we’ve been able to work with before. He’s the chief of the Division of Blood Disorders at Rutgers Cancer Institute. He’s been a medical oncologist specializing in lymphoma for more than 25 years and leads clinical trials to try and find new and better ways to treat diseases like Hodgkin lymphoma.

Dr. Matasar, what drew you to lymphoma? What inspires you to do the research that you do and dedicate yourself to patient care?

Dr. Matthew Matasar: First of all, thanks for having me. I’m really thrilled to have this opportunity. What we’re doing together really matters and makes a big difference so thanks for making this happen.

I started out as a philosophy major back when I was in college, wanted to go into medical ethics, and then got sucked into oncology.

I saw oncology in general and lymphoma, especially as a place where I could make a difference, where being a really good doctor or being a crummy doctor makes a difference. I wanted to be the kind of doctor who listens to his patients, works with them as individuals, and understands that when they’re coming to me, they’re having the worst day of their life. I want to try to make it a little bit better using my brain and my heart as best I can.

If I do my job well, it’ll be better than if I don’t. These things matter and what I do matters. I feel this pride in knowing that what I’m doing is making a difference for people in my clinic, individual by individual, and by trying to develop newer, more effective, and less toxic treatments.

Maybe I could leave a little bit broader mark on the world. Trying to make a difference. What we’re doing here is trying to make a difference.

Stephanie: Yes, and you’ve been doing that and we really appreciate that you go above and beyond to help patients and their families.

Next up, from one doctor to another, Dr. Samantha Siegel, both a doctor and a patient, which is a really interesting perspective. Sam, I’m really, really grateful to have you here and lucky to get to know you. Thank you for all that you do.

We will get into your Hodgkin lymphoma story shortly but, first, we’d love to hear more about you outside of the cancer diagnosis because as we know, we are so much more than that.

Dr. Sam Siegel: Thanks for having me. I’m so excited to be here and to connect with you and all of the patients, caregivers, and community members.

I am one-half of a sandwich. I’m married to another doctor named Sam, but we got married before med school. Sam squared, Samwich, he Sam she Sam — a lot of iterations of that that are fun and interesting.

I’m a proud mom of three kids. They’re my best teachers in this world. They’re so incredible. Parenting them through cancer and through medicine has been very interesting. It’s always exciting. Our house is never boring.

I love jogging, painting, and playing guitar. I’ve recently become an enthusiast of ecstatic dance. It’s like a nightclub but during the day. No booze and kids are allowed. It’s just freestyle dancing.

I used to dance growing up and I’ve gotten back into it lately as a way to connect with myself and my body. I found it really helpful in healing from chemo and chemo treatment. I love dancing, music, moving through music, cooking, and food.

I’m hoping to unify how other people enjoy aspects of being alive and how we can talk to our doctors about how to tailor our cancer treatment to what matters most to us. That’s really important to me because if I couldn’t jog, play my guitar, paint, or work with my hands anymore, that would be pretty devastating to me.

All of that matters when it comes to talking with my doctor. I’m excited to be here as a doctor, as a patient, as a person, as a human being, first and foremost so thank you.

Stephanie: Thank you, Sam. I couldn’t have put it better myself. It’s not just about extending life, it’s the quality of life and even after treatment.

We will talk about the long-term side effects because we all want to live and get back to living the way that we know how and maybe better.

Up next, another awesome rock star. You may know her as the genius behind Ohyouresotough, which is amazing artwork. Chelsea Gomez, thank you for being here tonight. As a patient advocate, you’ve grown such a community yourself. Can you also tell us more about you outside of the diagnosis?

Chelsey Gomez: Hi, everyone! I’m so happy to be here.

I’m from Florida. I just turned 33 and have a daughter.

I’m a professional artist. I own my own cancer awareness brand named Ohyouresotough. If you ever see anything of mine, you’ll see that I like to cope with hard things with humor. It’s really important to see the lighter side because a lot of the cancer world is not so fun.

I love all things art. I use clay, I paint, and I do digital art. When I’m not doing art, I’m running after my daughter to do whatever she wants to do, like play Barbies. I’m really excited to be here. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to share my story, too.

Stephanie: We appreciate it. Without voices like yours and Sam’s, we wouldn’t have the platform that we have today. Both of your stories are on The Patient Story so thank you for being here and for sharing your voice to help other people.

What is Hodgkin lymphoma?

Stephanie: Let’s get down to business. We’re going to try to avoid medical terminology as best as possible. Dr. Matasar, what is Hodgkin lymphoma?

Dr. Matasar: Working through things without terminology is theoretically what we’re supposed to be doing all day any day. When we’re talking to patients, families, and caregivers, we try to help people make sense of their illness.

What is lymphoma? Lymphomas are types of cancer. They’re cancers of cells called lymphocytes or immune cells. Lymphomas collectively are cancers that come from and are of the immune system.

That’s not to say somebody who has a lymphoma has a bad immune system — far from it. In fact, most people diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma have perfectly fine immune systems. They’re not constantly sick with infections.

For whatever reason, some cells mutate or change in a way that makes them live too long and start making copies of themselves. Then those copies live too long and they copy and the copies copy.

Compounding that, your body sees these cells that are copying that don’t belong there and views them as foreign or not right. In a similar way to an oyster that has a little grain of sand in it, it starts making a pearl around it. The body reacts to these cells and causes inflammation and scarring to try to wall off these weird cells causing even more swelling typically in lymph nodes, although that swelling can happen outside of lymph nodes in other parts of the body as well. It’s that swelling that usually leads to people being diagnosed with this type of specific cancer.

Sam’s Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis

Stephanie: Sam and Chelsey, you had symptoms and red flags that helped you figure out something’s not right. Sam, what was your experience?

Sam: I wasn’t feeling right. In hindsight, it’s interesting to go back and piece things together, but I felt this vague sense of tiredness. I didn’t have enough gas in my tank. I was still running 10 miles on the weekends, but coughing a lot.

I didn’t have the steam for my usual level of physical exercise. I was coughing a lot, particularly at night. There were a lot of California wildfires at that time so I thought it was the air.

And, of course, I’m tired. Every parent during the pandemic is tired, especially with our kids doing homeschooling. It’s a whole different world. Then being a doctor at that time was very hard.

But then I got a rock-hard lump that appeared above my collarbone. It was painless and rapidly growing. As a doctor, I knew that I had cancer.

I got a scan and mine said something about possibly metastatic lung cancer or breast cancer. They weren’t sure so I needed to get a tissue biopsy. A little bit of time transpired between noticing the symptoms and getting the tissue biopsied.

Once that came back as Hodgkin’s lymphoma, I knew what the path ahead would be like. Around the time I was diagnosed in 2021, there was this big change that started happening with immunotherapy. It was the standard of what had been happening for a really long time, which is ABVD or a combination of four drugs.

I got on the eve of my 30th birthday. Then I started ABVD.

There was a question about my staging, whether I was stage 2AE or stage 4 because there was some lung infiltration. Long story short, that meant that I was going to get six months of ABVD.

After a month or two, the coughing went away and I started feeling better. My cough came back at about month 2 to 3. We thought it was the bleomycin. I’m a runner and that’s very, very bad. We ended up dropping the bleomycin and I continued on AVD alone for the remaining four months.

Coincidentally, there had been a trial around that time to say that that’s okay, the de-intensification of therapy. Dropping the bleomycin became a standard thing, if people got a scan after a couple of months that showed that the body was responding.

My PET scan after two months looked really good. My cancer was responding and I was having that cough. We dropped the bleo and then I did four more months of AVD and boy, was it hard. It was really, really hard.

I had a lot of side effects. I struggled a lot and I struggled with that feeling. I hear people say about Hodgkin’s that this is the good one. It certainly didn’t feel that way. It felt really hard.

Stephanie: I hate when I hear whenever people say you got the good one.

Chelsey’s Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosis

Stephanie: Chelsey, how about you? What were the first symptoms for you or the red flags?

Chelsey: I was first diagnosed with Hodgkin’s in 2018 when I was 28. I was working a lot of hours so I was very tired, but I didn’t think much of it.

I had weight loss. I was trying, but it never worked before and then I suddenly started losing weight. I had shortness of breath and, at one point, I almost crashed my car because I had a vertigo episode. I ended up going to the doctor and they told me it was just stress.

The only reason I got diagnosed with Hodgkin’s was I eventually had a lump come up on the left side of the base of my neck. I went to urgent care. They told me that I just needed antibiotics, but there was something in their eyes that told me that wasn’t all I needed.

Eventually, my family forced me to go to the ER and we got a full biopsy done. I was in the hospital for the first time. Long story short, I had stage 2 Hodgkin’s and I also had ABVD. About halfway through, we had to drop below because I had toxicity.

I was re-diagnosed with Hodgkin’s in 2019 as well.

Dr. Matasar: First, hearing Chelsey, how you knew better, listened to your body, didn’t take no for an answer, and saw something that made more sense to you. The importance of that just can’t be overstated.

I meet so many patients who say, “Well, they told me not to worry,” or “My doctor told me to come back in six months and I was getting worse and worse, but I was told not to worry. I was told it was something else.” Congratulations on knowing better and I hope that people take heed and learn from the example that you set.

Chelsey: Especially when you’re young. It’s hard sometimes to speak up. But even if you’re young, you know your body.

Dr. Matasar: Maybe even especially if you’re young. We all know that old doctors sometimes don’t have the best reputation for listening to young people, trusting them, or taking them as seriously as they ought to be taken. Doubly so because of your youth at the time.

Changes in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma

Stephanie: Dr. Matasar, the treatment landscape in Hodgkin lymphoma has been changing quickly. Can you share about the evolution that’s been going on?

Dr. Matasar: Back in the ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s, clinical trials to try to make Hodgkin lymphoma better were all about intensification. How can I ratchet the treatment up to make it even stronger, even more toxic, but even stronger against lymphoma?

We were climbing that mountain of pushing to see just how much chemo we could cram into someone’s gullet in pursuit of a cure. All we had was chemo so what you want to do is more.

We’ve come over the other side of the mountain now and we’re in a very different place. As a discipline and lymphoma experts in the field, we’ve moved away from intensification.

We’re into de-intensification, personalization, and leveraging treatments other than chemotherapy as we try to help both maximize the chances of cure and minimize the short- and long-term risks of our treatment.

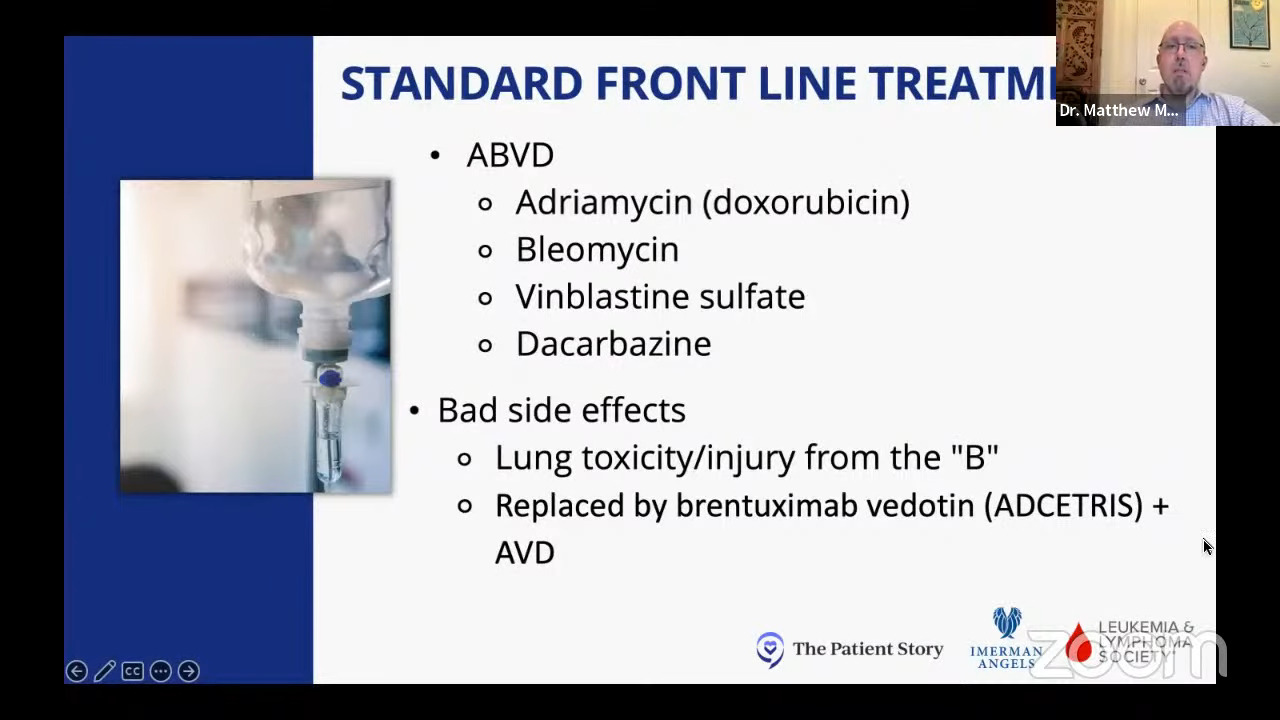

We’ve gone away from uniformly using ABVD, which remains a very good treatment and a very commonly used treatment.

More often, we’re now using other adjunctive treatments like brentuximab vedotin or ADCETRIS in lieu of bleomycin, which both Chelsey and Sam talked about potentially injuring their lungs, leading to cough or shortness of breath.

We’re finding ways to cure more people and, at the same time, cause less harm along the way and that’s really where the future of Hodgkin’s lymphoma is going to take us. We try to make even more progress on this mission towards more effective and less toxic treatments.

Stephanie: I love that that’s the trend and that we can continue going down that path.

First-line treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma

Stephanie: We’ll talk about some of these newer promising treatments and new directions, but can you tell us a little bit more about the standard first-line treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma?

Dr. Matasar: As oncologists, when we meet a Hodgkin’s patient for the first time and we work through their treatment choices, we think through those choices together with our patients and their families.

We split people into different categories as we understand the risk of their disease and the options that are presented because of that.

One first way to try to put people into categories to help them think through their choices together is based on stage. We talk about early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma and advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma.

People will often ask, “What’s my numerical stage? Is it stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, stage 4?” We heard from Sam that sometimes, it’s not even clear to us as oncologists exactly what the stage is. Is it a stage 2E or is it a stage 4?

The staging exercise, which sometimes feels very black and white, can have shades of gray. We do our best to try to put people into risk categories informed by their stage and then think through the treatments that we know are best for that stage of illness.

Early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

Dr. Matasar: For the vast majority of people with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, the standard of care remains to be ABVD. It’s been around longer than I’ve been a doctor. It’s an oldie but a goodie and it still will cure the vast majority of patients.

Sometimes we think about radiation therapy as part of that treatment and sometimes not. However, ABVD for early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma remains the standard of care.

Advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

Dr. Matasar: For most patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, we’ve moved away from ABVD. This is based on really powerful clinical research comparing ABVD to a program where the bleomycin was swapped out in lieu of this newer immunotherapy called brentuximab vedotin, which is a type of drug called an antibody-drug conjugate.

An antibody is a protein that binds onto the surface of a cell and stapled to that is a toxin so this conglomerate attaches onto the Hodgkin cell, the Hodgkin cell absorbs it, and then the toxin is released inside the cell — like a Trojan horse sneaking into the city and releasing the soldiers inside.

This newer program where bleomycin was swapped out for brentuximab — so BV-AVD instead of ABVD — not only got more people into remission and kept them in remission longer, but actually led to a higher cure rate, people living longer, and everything good that we as doctors want for our patients.

Because of this important research, we really now use brentuximab plus AVD as our traditional standard of care treatment for patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma in pursuit of a cure.

Role of radiation in Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

Stephanie: You mentioned radiation therapy as well and that has been its own sort of beast, if you will. There are a lot of considerations about long-term side effects and where the mass is located. What role do you think radiation therapy has been playing? What are your thoughts about whether it should still be used and in what situation?

Dr. Matasar: It’s a great question and you’re right, it is sort of its own beast. Back in the ’80s and early ’90s, almost everybody with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma got radiation treatment as part of their care.

We knew then and now that using radiation therapy would cure a few more patients than not, but that slight improvement in cure rate never translated to people living longer.

It’s a trade-off. You may do a little bit better with Hodgkin lymphoma in some situations but you’re paying a steep price oftentimes in terms of long-term effects, late effects, and risks of health problems later in life.

That includes radiation therapy putting patients at a higher risk for other cancers later in their life, particularly younger women who need radiation therapy to the chest. If that radiation touches the chest wall and breast tissue, particularly for women under the age of 35 or especially under 30, it really does heighten the risk of breast cancer later in life.

Your heart also doesn’t like radiation therapy much more than the rest of you. We know that radiation therapy to the heart can lead to a higher risk of heart disease later in life.

There are all these consequences of the decisions that we make together in our pursuit of a cure. Because we know so well about these late effects of radiation therapy, increasingly, we try to be ultra choosy with whom we use radiation therapy.

We really restrict its use for what we think we really need to get a cure. For most patients, we can cure them just fine without using radiation therapy and putting people at risk for health problems later in life because of that treatment.

Use radiation therapy if you need to; it’s a great treatment. It can be life-saving when you need it but don’t use it willy-nilly.

Side effects of Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

Chelsey’s side effects of bleomycin

Stephanie: Chelsey, you experienced the toxicity and side effects of bleomycin. Can you talk to us about what that reaction was and what you did about it?

Chelsey: I had my fifth chemo right before New Year. I had chemo four other times, but I went home and spiked a really high fever all of a sudden. As a cancer patient, if it’s 100.4°F, you have to go. Mine was 102 and my husband said, “We’re getting in the car.” I was very lethargic and just not feeling well.

We ended up in the ER and they told me I was septic. Of course, my mom heard that as well. She was watching my daughter and she’s freaking out because it’s not good when you’re septic. They put me in the ICU and I was in the ICU for at least two days.

The symptoms dissipated after a few hours. I was feeling better, not 100%, but they started giving me antibiotics around the clock.

I had a feeling that it had something to do with bleomycin. I’ve researched what can happen with bleomycin because I have asthma and that was something I had to consider going into the treatments.

Everything I was seeing was adding up to it being toxicity, but there was nobody at that hospital who really treated cancer patients. They came in and out, but they weren’t there all the time.

It took about four days for my oncologist to actually come and see me. At that time, I pretty much diagnosed myself with bleomycin toxicity. I also stopped accepting the antibiotics because it wasn’t an infection. It was a reaction to this drug and it was confirmed later on.

I also had a pulmonary function test and I had a 30-point drop or something. I’m happy to report that I have regained a lot of my pulmonary function now many years out. For a lot of people, I know that’s something scary when you do go through this.

This was a local hospital and they had never seen this before. The doctor was saying, “You need to advocate for yourself, especially when you’re in a situation where you know your cancer probably better than the people that are there. It’s not your regular care team.” I had to speak up for myself and it was hard, but I did it.

Stephanie: I really appreciate that you spelled that out. Dr. Matasar talked about it earlier, too, and I know Sam’s a huge proponent of that as well.

You said it was hard and I think we’ve all experienced that as patients where you want to advocate for yourself. You hear it from other people. It can be a little bit difficult to speak up. Do you have any other tips for people who are on the fence about it, who aren’t sure if they’re supposed to speak up?

Chelsey: I wasn’t a great advocate for myself when I first got sick. The oncologist I ended up with was the one who was just walking by when I was in the ER initially and I thought it was fate. It wasn’t. Immediately upon meeting him in his office, he told me it was the good cancer.

I was like a unicorn of the Hodgkin’s. Nothing went how it was supposed to go. It wasn’t good at all. Sometimes I was quiet about it. I didn’t know what to do because I always look things up and he would call me Dr. Google but not in a nice way. I was scared to bring up a lot of things.

If you’re young and you’re scared or sometimes it’s when you’re female and you have a male doctor, it can be intimidating. Bring your family with you or somebody else you trust and have them speak up for you if you are scared to do it. I know a lot of people do that and it’s helpful.

When you’re inside that room, your mind goes fuzzy and you don’t even know what’s going on half the time. It can be the difference between having a good result or ending up pretty much needing a transplant like I did. I truly believe that if I had been a better advocate, I might have not needed one.

Stephanie: Thank you for going into all that. I can completely attest to blanking out in the doctor’s office and not hearing the same thing that my family heard. I appreciate that tip about bringing people in if you can.

Sam’s side effects

Stephanie: In terms of side effects, you worked with your doctor to manage them. Can you share anything that was helpful there?

Sam: I had a lot of side effects. I had a lot of nausea and vomiting, yet I gained a ton of weight during AVD from all the steroids and I was developing a lot of problems from that. My glucose and liver enzymes were increasing. I had inflammation in various organs.

In hindsight, I think that was also making my neuropathy really bad because once my glucose got better and I lost weight, my pain and my nerves got better, too, despite the fact that I was getting more medicine that theoretically should have been impacting the nerves.

All your systems can be impacted. Taking care of the whole body is really important. I talked to my doctor about diet, lifestyle, and supportive therapy. What are some complementary therapies that I could try while getting my traditional medicines?

I also took a lot of medicine at the time. I needed pain medicine. I needed nausea medicine. I needed all the tools in the toolbox to cope with living day-to-day because it was just really hard.

The medicines caused a lot of mood and neuropsychiatric side effects. I had problems thinking. At some points, I had problems driving or following a list of simple items and that was really tough for me. That was a really far fall in terms of functioning, going from being a doctor to having trouble shopping a grocery list of five items so that was pretty devastating.

When I found out that I could do brentuximab as therapy leading up to the transplant, that gave me a huge quality of life back. As those other drugs cleared out and my body healed, I could think again and started feeling myself in here again. I’m not gone, I’m still there, and that mattered so much to me. It was a huge gift.

Stephanie: I really appreciate you bringing that to life because sometimes, we feel lost in that fog and how important it is to get any semblance of that quality of life back of ourselves. Your story shares that so powerfully.

Immunotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma

Stephanie: We’re going to shift to combination therapy for the front line. Patient Matthew S. asks, “How successful have immunotherapy trials been in regard to Hodgkin lymphoma?” Dr. Matasar, can you explain the idea behind combination drug approaches and for whom would this benefit?

Dr. Matasar: We’ve talked about the progress that we’ve made with swapping brentuximab vedotin for bleomycin.

Matthew’s question about immunotherapy is a really valuable one. This idea of immunotherapy has really been a revolution in a lot of different forms of cancer, but nowhere has it been more impactful than in Hodgkin lymphoma.

When we talk about immunotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma, what we’re generally speaking about is a class of medicines called checkpoint inhibitors.

One of the ways that these Hodgkin’s cells survive in our body is they are able to effectively shield themselves from our normal healthy immune system cells. They put up these barricades and ways of shielding themselves or hiding or preventing our immune system from doing the trash.

There are two checkpoint inhibitors that are approved for Hodgkin lymphoma, which are very similar medicines truthfully: one called nivolumab and one called pembrolizumab — we’ll call them nivo and pembro for short. These medicines are able to strip those shields off of the Hodgkin lymphoma cells and allow your immune system to see what it was otherwise blind to.

The treatment itself does nothing to the cancer cells. It does not kill a single cell all by itself. What it does is re-enable your own body’s immune system to do the work. It’s a game-changer.

When we use these medicines by themselves and use them as a treatment for a patient who’s been failed by many different prior chemotherapies, they’re able to put people into remission more than half the time.

They’re actually able to cure some patients. Despite chemotherapy having failed again and again and again, this medicine is able to eradicate the lymphoma. It goes away and never comes back. That’s amazingly powerful to be able to say and it’s an amazingly powerful treatment modality for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.

The more we learn about how good these medicines work, the more we want to use them for more patients to try to help cure more people. It went from being a last-ditch effort after everything else has failed to be part of the treatment when it comes back. Using it in that situation was able to help more patients.

We’re now seeing the initial results of our first trials of using it as part of the first treatment. Instead of ABVD or brentuximab plus AVD, we’re combining nivo or pembro with chemotherapy like AVD and we’re starting to see very promising early results.

BV-AVD vs. ABVD as first-line treatment

Stephanie: How much is brentuximab and AVD being used? Is it standard of care or does it just vary depending on the hospital system or the healthcare provider versus going to ABVD first-line?

Dr. Matasar: It’s a little bit hard. Everybody’s situation is a little bit different. There are standards of care, which means that all things being equal, it’s sort of a one-size-fits-all approach.

Medicine is never that clean or that easy. There are times when ABVD would be a standard for early-stage disease, but we have to use brentuximab instead of bleo. There are people with advanced-stage disease who even if BV-AVD would be the standard, I still want to use ABVD for this individual patient.

This happens because doctors listen to our patients and we take into account their personal priorities, preferences, and individual risk profile. All of these medicines have their own pros and cons and their own risks and rewards.

A treatment program is best when it’s personalized and done in the context of a doctor and a patient having meaningful and valuable conversations about what matters to that person. Is it just a cure regardless of side effects? Is it being able to play the guitar and run? What is it about the treatment that we need to take into account as we map a path toward cure?

Stephanie: Any idea of when we could see the FDA approval of checkpoint inhibitors in the front line?

Dr. Matasar: Certainly not anytime soon. The first results that we had were read out at major conferences. This is still very early data.

When it comes to Hodgkin lymphoma, doctors were very conservative. We don’t want to mess this up. We know that the stakes are high and that many people will be cured with traditional treatments. We don’t want to change gears until we’re really confident that we’re not hurting people in the process.

The initial safety readout of this combination using the checkpoint inhibitors in the first treatment looked better than any of us expected. There are a lot fewer immune-related side effects than we’re accustomed to seeing when using these immunotherapies. They do have their own immune-related side effects.

We want to see the data mature, as we say. We want to see how people do over time and make sure that there are no dangerous signals about increased late effects or late side effects happening as we gain more experience with this treatment approach.

Long story short, we don’t want to change anytime immediately soon. We’re probably looking a couple of years down the road.

Treatment for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma

Stephanie: Dr. Matasar, how have the standard of care treatments for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma patients been changing?

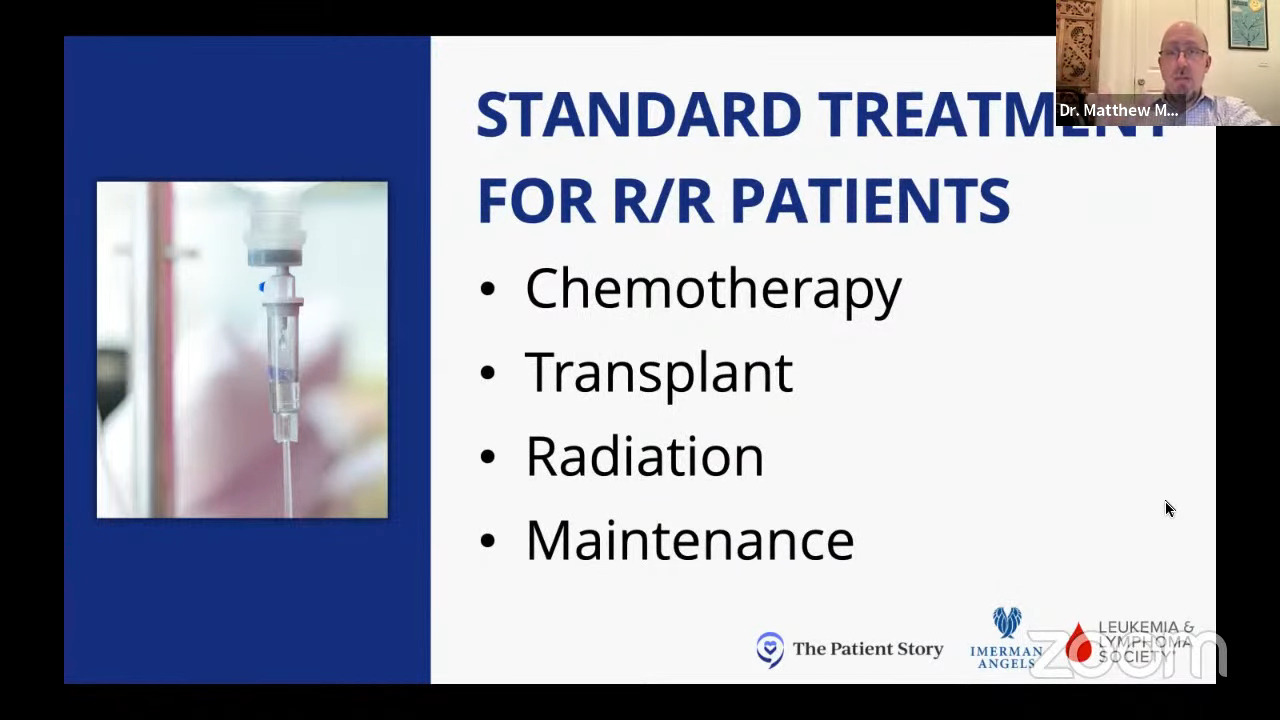

Dr. Matasar: Historically, when chemo failed, we would use other chemotherapy programs that use different chemotherapy medicines than the first cocktail. The most commonly used in America historically was a program called ICE: ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide. Different than ABVD because they’re different medicines, but still chemo.

We’ve moved away from ICE being the only standard of care and we’re using more of those other medicines — brentuximab, the checkpoint inhibitors. You can use one of them all by itself or in combination.

It’s informed, of course, by what we did the first time. If patients get brentuximab as part of their first treatment, we’re not going to rush into doing it a second time and want to do something a little different. Maybe we would use checkpoint inhibitors alone or combined with some milder chemotherapy programs.

This is the art of medicine. Trying to pick amongst a number of very effective choices and determining how to leverage those medicines and combine them to achieve our patient’s goals. Always with this view of maximizing the good and minimizing the bad.

Sam’s Hodgkin lymphoma relapse

Stephanie: Sam, you relapsed a month after finishing your first-line treatment. I can’t even imagine what a gut punch it was to go through all that and then find out that news. What was that conversation like about where you were going to go next?

Dr. Siegel: Gut punch is a really great way to put it because it was. I finished six months of ABVD, which then went down to AVD. Despite a scan saying that I had no evidence of disease, I felt pretty awful.

At that point, I wasn’t sure. Am I just feeling awful because this is just what a body feels like after you’ve had six months of this poison? Something in my gut was telling me that something wasn’t right yet, but my scan was clean so I just focused on recovery for a little bit.

Within a month, I started having symptoms that were eerily reminiscent of my initial symptoms — a wheeze only in the left upper part of my chest and a little pea-sized lump. That time around, I thought, Okay, I think I’m pretty clear what’s happening here.

I got a scan, which led to some biopsies and a diagnosis of a relapse. I’m already researching on Google the next treatment regimen that I’m going to have to go through. The whole while, I’m preparing myself that I’m going to have to go through ICE.

I’m thinking for sure I’m going to have to go through something called ICE, DHAP, or one of these other regimens that have been used longer term for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s or salvage therapy.

When the relapse was confirmed, my doctor said, “There’s this drug now, a targeted therapy called brentuximab. Instead of doing ICE, would you be open to trying that alone for a couple of months and then repeating a PET scan to see where we’re at?”

There was a pretty decent chance that if the brentuximab didn’t get me into remission before the transplant, I would have to get ICE, a multi-drug, more traditional chemo. I was willing to take that chance because I felt so beaten up by having to get all those months of traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy and all the side effects.

The decision made sense to me at that time whereas maybe other people may have been, “No, I want to hit it hard and do that right away.” For me, I was going to take the least amount of poison possible to get me into remission before transplant.

It worked. I got a strong remission before my transplant. I went on to get the bone marrow transplant then I took brentuximab. I did almost a year of post-transplant consolidation treatment.

Because those studies and the data were just coming through, my doctor said, “You know, this is kind of becoming a thing now based on the research and this seems like it might really fit you based on how bad you’re feeling,” so that was perfect for me. I was so grateful.

Stephanie: The timing matters, right? It just happened.

Stem cell transplant

Dr. Matasar: The first thing to say is that there are two types of transplants. What we’re talking about so far is a treatment called autologous, or from yourself, stem cell transplant.

To call it a transplant is actually wrong. There’s no transplantation going on; it’s just a word that we use. This treatment that you’re hearing from Chelsey and Sam is basically just a trick. It’s a way of letting us give a round of super strong treatment.

With regular strength treatment like ABVD or ICE, we give those treatments and then let people recover. Sometimes if the chemo is stronger, you might need to boost the recovery.

Here, we’re talking about a single course of treatment, usually six days, that is so strong that if I gave it to my patient, gave them a hug, and said, “I’ll see you later,” I wouldn’t see you later. It’s too strong.

We need a very powerful antidote for such a powerful treatment. The antidote that we use is actually a person’s own stem cells, these special Adam and Eve progenitor cells that live in our bodies and let us heal.

We filter the blood ahead of time with a process like a mini dialysis where we filter out a few of those special stem cells. We put them in the freezer, give people six days of chemotherapy, thaw out those cells, and give them back as an antidote.

The course of the six days of treatment and the stem cell re-infusion as a little mini transfusion, that’s the antidote. That is we are calling a transplant.

That’s different than an allogeneic or donor stem cell transplant where there really is transplantation going on. Your immune system is being put to sleep and a new immune system from a sibling or a stranger is put into your body to give you a new immune system. We then task that new immune system with attacking your cancer. For us, that’s a very different ball of yarn.

Chelsey’s Hodgkin lymphoma relapse

Stephanie: Patient Caitlin M. asks, “For relapsed/refractory patients, are there other options aside from chemo to get into remission before a stem cell transplant?”

Chelsey, you went through immunotherapy, but unlike Caitlin, you didn’t respond. After three cycles, your PET scan showed disease progression. I can’t imagine what that was like.

It would be great to understand more about your experience in terms of the conversation you were having with your doctor ahead of the transplant. Are there questions you wish you’d ask your doctor?

Chelsey: I relapsed in the latter part of 2019. I switched to the Mayo Clinic for my care. I had been researching through the relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s groups on Facebook. I saw nivolumab, brentuximab, and all of those things, and they were a lot less harsh.

I asked about it when I went there and it was a newer thing at that time. My oncologist said, “Yeah, we can give it a try. It’s had really good results.”

Sam mentioned that the side effects of ICE and the side effects of brentuximab are a night-and-day difference. I don’t think anybody wouldn’t want to try the less harsh one leading up to the transplant.

I had three of those treatments, had a scan, and my cancer progressed. My oncologist was honestly shocked as well that it didn’t respond whatsoever and that made me actually ineligible for maintenance, like what Sam had.

We switched to ICE. ICE was the first chemo where I had to be inpatient for three days every time. It was intense.

When your hair falls out on ABVD, for the most part, it’s slowly coming out. With ICE, it was clumps of hair coming out. I was very sick. It was very, very harsh chemo.

Chemotherapy & immunotherapy pre-transplant

Stephanie: Dr. Matasar, for relapsed/refractory patients, can you explain this combination of chemo and immunotherapy in the context of a transplant, hopefully, what this might lead to?

Dr. Matasar: Up until now, the goal for patients who have their disease come back despite good first treatment is to get their disease into remission and then into a round of high-dose therapy or autologous transplant in an attempt to maximize the chances of cure.

Can we cure people reliably and consistently without a transplant by leveraging these immunotherapies either alone or in combination with chemotherapy? This remains a clinical trial-type question; this is not a DIY thing.

My hope for the future is to use these treatments, particularly immunotherapies, to really limit our need to take people through the rigors of high-dose chemotherapy, cure more people, and cause fewer problems.

Determining the sequence of treatment

Stephanie: If the ABVD didn’t work, there’s a relapsed/refractory situation. Maybe there’s some radiation that’s been involved. You have studies about brentuximab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab alone or in combination. How are doctors having that conversation about the right thing to do next? What is the most promising next course of option?

Dr. Matasar: This is the art standing next to the science. There is some artistry to what we try to do to figure out the right lid for each pot and how to help a patient navigate the course of their illness.

There is no one-size-fits-all anymore. It used to be ICE; that’s all we did. It worked well and it was awful. Now we have a range of choices.

You have to sit with a patient and think through it. How much disease is there that I’m trying to shrink away? How quickly is it growing? How do you feel? How sick is it making you? How quickly do we need to get you better? What was your first treatment? How well did it work? How badly did it not work?

Take all of these factors, try to cram it into your doctorly brain, and try to give some reasonable recommendations. Sometimes you’re going to be as gentle as brentuximab all by itself. Sometimes you’ll want to give more chemo. Sometimes you want to give checkpoint inhibitors alone or with BV. Sometimes you want to do checkpoint inhibitors plus chemo. These are all reasonable courses.

Ideally, what you’re doing as a doctor is working with your patient as a person, as an individual, and charting a course that makes sense for them, for their illness, and for their life.

Stephanie: It’s a really thoughtful response. Are some of the considerations the treatments you had before, how successful they were, what’s already been done… What about things like age or comorbidities or those kinds of factors?

Dr. Matasar: We try not to be ageist, but, truthfully, taking care of a 30-year-old is different than taking care of a 90-year-old and to not recognize that would be silly.

That being said, it’s always a matter of individualization — understanding an individual person’s goals, their preferences, what risks they’re willing to take, what matters to them, and then trying to figure out the best treatment for that person, given everything you know about them, about their value system, and about their goals of care.

Stephanie: Wonderful. I wish every doctor thought like you.

Long-term post-treatment side effects

Stephanie: We’ve talked a little bit about long-term or late-term side effects. Patient Ariadne J. asks, “What is known about long-term post-treatment side effects?”

Sam: I love this question because now I can plug survivorship, which is basically my newfound life passion as a patient-doctor. Cancer survivorship, even though a lot of people don’t necessarily identify with the word survivor, is an important thing to keep your finger on the pulse.

Survivorship applies to this area of medicine that’s changing and evolving. It’s anybody living after a cancer diagnosis and that could be during treatment if you’re on long-term treatment and that could be after your treatment is over.

There are a lot of ways that the cancer experience, even if the treatment goes perfectly, makes you question your life when you’re in your 30s and have your fertility changed. There are all these things that get impacted once you hear that big C word.

Survivorship is an evolving area in medicine that is trying to address all of that. For me, there was a lot. There was identity. There was this existential crisis. Death and dying and making sense of all of that.

The steroids and the other medicine that I had to take impacted my thinking and my emotions. I’m usually a pretty balanced, even person so that was a very hard roller coaster.

There’s some cardiac stuff for some people. Doxorubicin, which is part of the initial treatment, is something that we really need to be thinking about. We’re giving people this medicine that’s toxic to the heart in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. We need to talk about intensive lifestyle interventions like a healthy diet and cardiovascular exercise.

An overall program that focuses on wellness is hugely important in managing long-term side effects and integrative medicine. I’m doing an integrative medicine fellowship. I’m trying to unify everything that I learned in medical school with everything I needed as a patient to get better from cancer and cancer treatment and hoping to offer that to other people.

Those are practitioners that you could consider going to or looking up. Make sure that you communicate everything you’re trying and doing with all of the people who are in charge of your care, including yourself. You’re an important part of that conversation. Cancer survivorship is important for managing long-term side effects.

Stephanie: Chelsey, what were the long-term side effects for you? You talked about going into menopause, for instance.

Chelsey: The main thing I struggle with that is the most apparent in my everyday life is the cognitive side effects of all the different treatments. I honestly think it was from the extreme stress that I was under for so long.

I was on this job in an insurance company and I had to balance things with legal documents. I know that if I were to go back to that job, I would not be able to do it now and that’s taken me a long time to see that that’s okay. I’m still me and I just have to work with things differently.

I have fatigue a lot of times and joint pain. I often joke that inside, I’m 80 years old but on the outside, I’m in my 30s so it feels like that.

As Sam mentioned, there’s a lot of identity crisis that you have as a cancer patient. Who am I now? What happened to the old me? What can I do?

I really want to encourage people to seek community. Even just hearing from Sam, I’m sure some people will say, “Oh, other people feel like that?” That’s definitely what inspired me to start making art and connecting with others. It can truly make a difference in your long-term mental health in survivorship.

Stephanie: Thank you so much, Chelsey. You capture a lot of that in your artwork.

Stephanie: Dr. Matasar, with the newer therapies that are either just approved or in the pipeline, are we addressing some of these long-term/late-term side effects that hopefully people can avoid even years later after treatment ends?

Dr. Matasar: We are. A lot of the drive to develop these newer treatments has been informed by our understanding of late effects, cancer survivorship, and the risks that survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma treated with more traditional treatments go on to face.

We still need to follow with these newer treatments to watch for the possibility of late effects. We don’t believe that they’re going to cause as many or as severe, but part of the work of survivorship is learning from our survivors and walking that path with them as we see how their lives unfold over the years and decades to come.

The number one thing that I would encourage survivors to do is to work with your care teams on developing a survivorship care plan. It can be a paper document or a digital document. It should be something that lives with you that says what your diagnosis was, what your treatments were, and what our understanding is of what you can be doing to safeguard your health in the years to come.

That’s informed by understanding the possible long-term consequences of the treatments that you received, how doctors think you’re best served by taking care of yourself, and what doctors can do to prevent or reduce the risk of those problems as you go on to live your lives.

Stephanie: Wonderful. That’s a great tip. It’s great that the trend of more focus on survivorship after treatment is going to do wonders for so many people.

Shared treatment decision-making

Stephanie: We all want to be more empowered in our care to be able to ask doctors the questions, to feel that we can, and to ask ones that will be impactful.

Dr. Matasar, you talked about how the right treatment for each patient depends on different things like age, health, transplant eligibility, and goals of therapy. How can a patient find out the best treatment options for them and in what order? From a doctor’s perspective, what should that conversation be to elicit the best response for patients and their family members?

Dr. Matasar: I was really disheartened, Chelsey, to hear your story of your doctor disparagingly calling you Dr. Google. Nobody should have to deal with this stuff anymore. We’ve got to be better than that.

Everybody should be empowered to come into a conversation with a doctor as an equal partner in this process. I tell my patients, “This is about you. It’s not about me. I’ve got no ego in this. This is your mountain that you’re climbing. I’m not climbing the mountain. I’m the Sherpa. I’m dragging your bags alongside you. But this is your climb and I’m here to help.”

As patients or as caregivers, if you aren’t feeling valued and heard, then you may not have found the right fit for you in terms of your care team. Everybody should always feel free to be getting a second opinion. I Not enough people take advantage of this sometimes. They don’t want to insult their doctor. I don’t want to be that guy or that gal and I don’t want to be a pain in the ass. Be a pain in the ass.

I like nothing more than when my patients are pains in the ass and they come in with lots of questions. It means they’re doing their homework and they’re really invested. They want to learn and take advantage of whatever I’ve got up in my brain. I love nothing more and any doctor should love nothing more than a patient who’s all in on partnering with me on making this thing work.

Be vocal. Do your research if you want to. You don’t have to. You shouldn’t have to. But if you want to and if it’s something that you value, then that should be celebrated by your care team and never put down.

Chelsey: Have open discussions with your oncologist. If you do find other studies or other treatments, they should be open to answering your questions about it and not being dismissive, even if it’s not an option for you. They should be able to explain to you why or why not.

If you’re a young person about to have a transplant, even if you’re not but if you’re in childbearing age, please ask about fertility. I’m now in menopause at 33 years old.

It was explained to me and I understood. We didn’t really have time to waste to get me to transplant. That’s a conversation you should bring up not only when you’re going into a transplant but also when you first get diagnosed with cancer.

Stephanie: Thank you, Chelsey, those are very important questions. I was lucky to have first-line treatment and be okay, but I asked that question before my intensive chemotherapy. It’s great whenever we’re reminded: advocate for yourself depending on what you want your life to look like.

Finding a Hodgkin lymphoma specialist

Stephanie: Dr. Matasar, it’s clear that for relapsed/refractory patients, and if people are experiencing multiple relapses, it’s hard to find one answer from one doctor. They seek different opinions or get different responses. It’s a very personal discussion to be had.

Is there a right time to find a Hodgkin lymphoma specialist? When should that happen? How can you have that conversation?

Dr. Matasar: It’s tough because it’s very personal. My general philosophy is that people deserve to have expertise in their corner. I also recognize that people want to receive care close to home and they should be able to receive good care close to home.

In an ideal world, everybody would have an oncologist who lives close to them and everybody would have access to an expert to support the decision-making and to support the care journey. Sometimes that would be the same person.

If you lived near an expert, perfect. If you don’t have an expert in your neck of the woods and you want it, then you should have the opportunity to seek out that expert as a consultant and as a backup.

That doctor would work collaboratively with your local oncologist as a team to make sure that they’re doing everything to the best of their ability. You have the expert on standby in case things go sideways. In my mind, that’s the ideal.

If patients aren’t comfortable with what they’re hearing, even from me as an expert, go see somebody else. Hear from another set of lips. Get a fresh perspective. Maybe there will be a better fit in terms of that critical doctor-patient relationship.

Any doctor who doesn’t want you to get a second opinion doesn’t deserve to be your first opinion. Find the care that feels right to you. Trust your gut. The importance of the doctor-patient relationship is too great. It’s too critical in a relationship to settle for anything less than the best.

Stephanie: It’s so resonant and it’s powerful to hear from someone like you, Dr. Matasar. If the doctor doesn’t support you getting a second opinion, they’re not worthy of being your first opinion. I really love that.

Final takeaways

Stephanie: If there’s anything else you want to add, what would you really want people to take away from this discussion?

Dr. Matasar: I’m just bringing it back to The Patient Story. What you’re doing, what we’re doing together is where modern medicine should be. We should be building community. We should be sharing experiences and stories and supporting one another.

Every patient’s journey is unique and yet we don’t walk these paths alone. If you can find ways to build community and be supported by various communities, it makes the journey a little bit less painful.

Chelsey: He said it really well. When I went to my second doctor, I felt comfort and care that I hadn’t gotten before. Make sure that you are having a good relationship with your doctor.

A sense of community is very important because a lot of society puts a little bit of an expectation on our shoulders to always be brave, positive, and strong warriors, and not everyone feels that way.

I just want you to know that’s okay. It’s okay to authentically be yourself and talk about the hard parts of cancer, not just the smiling, ringing the bells, and all of that. There’s a lot more to cancer than that. It’s okay for you to feel the way that you feel, however that is.

Sam: Having lots of questions doesn’t make you anxious so it’s okay to have lots of questions and concerns and to look things up. It’s okay to reject that label because you’re just appropriately concerned about your life and the quality of your life.

Some doctors may be more attuned to knowing to ask about what’s really important to you in your life. Some people may be really busy that they forget that. As patients, it’s up to us to tell our doctors what’s really important to us and things that we like doing.

Share with your doctor what’s really important to you. Not only will it help them to know you as a human being, but it will help inform treatment decisions.

There were times during my treatment and I’ve heard from other patients where it felt like to want anything more than not dying was greedy. We’re beyond that now in medicine.

We are in the era of personalization, community, and individualized care within the guidelines of all the new things that are being discovered. It’s not greedy to want to keep exercising to some degree or keep doing your art or whatever defines the quality of life for you.

Tell your doctor what’s important to you. Reject the anxiety label. Let’s shift the focus from mortality to vitality in cancer. It’s so much more than just not dying. It’s the living part.

Stephanie: You both have exemplified that so much. I’m really grateful to have had you, Chelsey, and Dr. Matasar doing your work in research and helping patients and families holistically. Thank you for the work that all three of you are doing as advocates.