Sarah’s Stage 3 ER/PR+ HER2- Breast and Salivary Gland Cancer Story

Sarah McDonald was recently married and promoted to an executive role at eBay when she noticed a lump in her mouth. Despite doctors assuming the lump was not a concern, she pushed to have it examined and removed. Test results revealed the lump was salivary gland cancer.

This led Sarah to reexamine a lump she discovered in her breast 6-years earlier, which doctors had said wasn’t cancerous. She and her doctors discovered that she had stage 3 breast cancer, thus catalyzing her double cancer journey.

In the midst of her cancer battle, Sarah grappled with her father’s prostate cancer diagnosis and dreams of having a baby. Her treatments led to the heartbreaking news that she may not be able to get pregnant. But after her doctor discovered new research about pausing treatment for IVF, Sarah delivered her daughter at age 48.

Sarah shares her incredible cancer journey with us, as well as in her book, The Cancer Channel: One Year. Two Cancers. Three Miracles. and at medical conferences and corporations. She hopes to give cancer patients a voice, to help them feel seen, and to get people to talk more about cancer.

- Name: Sarah M.

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Salivary gland cancer

- Breast cancer

- Invasive Ductal Carcinoma

- ER/PR+, HER2-

- Staging: 3

- Symptoms:

- Lump in mouth

- Age at DX: 44

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation

- Surgery

Life was very black and white for a while there, and it went back to Technicolor when we started to believe that I would live.

Sarah M.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Symptoms & Diagnosis

- Being A Patient Advocate

- Processing A Cancer Diagnosis

- How did you feel about your diagnoses?

- Recognizing the importance of relationships

- As an executive of a major company, how did your views on work change?

- Was there any difference between your rare and non-rare cancer diagnosis?

- What treatments did you receive for your cancers?

- How long did you receive treatments?

- How did you face your anxiety?

- Feeling grief over the future

- Can you reflect on surviving two cancers?

- Fertility & Pregnancy

- Survivorship

- How did you get through your cancer diagnosis and treatment?

- What’s your advice to someone struggling with anxiety?

- What is guided imagery and how did it benefit you?

- Tell us about your dad

- What was it like being diagnosed with cancer at the same time as your dad?

- How did your dad react to his cancer diagnosis?

- Did your relationship change with your dad after your diagnosis?

- Describe what it was like making different cancer care decisions than your dad

- Reflections

Symptoms & Diagnosis

Tell us about yourself

I’m a people person, fully engaged in life, and an extrovert. I am into food, reading, hiking, and music. I’m a singer, a former athlete, a mama, and a wife.

I sing in a vocal jazz group, it’s a women’s acapella group, and I sing alto 1.

What would the summary of your cancer journey say?

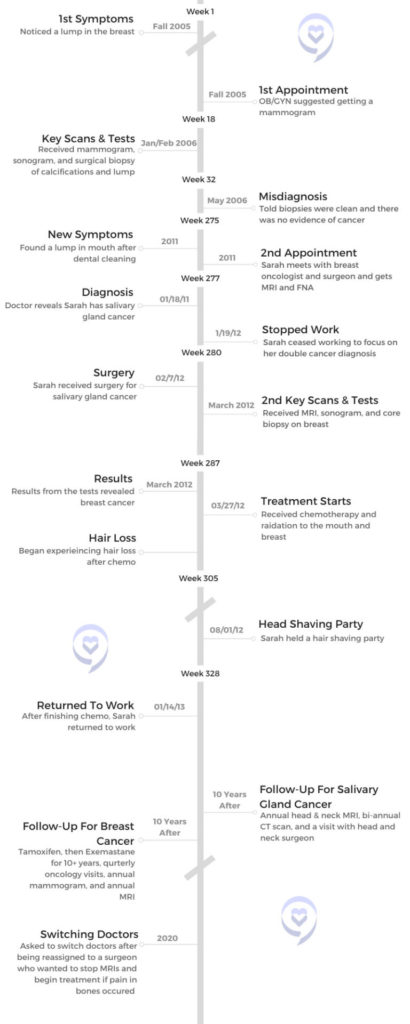

The summary says, at age 44 Sarah was newly married, newly promoted at work, and considering pregnancy. Then, all of that was blown up when I received my first cancer diagnosis which was an incurable cancer diagnosis, followed 2 months later by a second unrelated cancer diagnosis.

The book is about my fertility journey that was cut short, being diagnosed and then treated for 2 separate unrelated cancers. At the same time, my father’s cancer which had been in remission for 10 years, came back. He and I actually went through cancer treatments until his death that year together. It made for a very interesting time and made our relationship even tighter.

Two years past treatment, I was able to carry a child and give birth to our little girl. The name of the book is The Cancer Channel: One Year. Two Cancers. Three Miracles. I had a whole bunch of different titles for the book, but Cancer Channel is where I landed.

What were your first symptoms?

I had just been promoted into a new role. I went from managing a very large team to being an individual contributor. I had some extra time so I thought I would go do all of those doctor’s appointments that I had been putting off, which is always an ominous beginning to a story.

I went to the dentist and had a deep cleaning of my teeth. A week later, I noticed a lump in the floor of my mouth. I had never noticed it before and I thought it was probably an infection. That was the first symptom, a lump.

I guess the tumor finally reached a size where I would notice it. It was a very slow-growing tumor. The doctor said it had probably been there for a while. There was no pain. I wasn’t having dry mouth. There was no other indication other than a lump that didn’t hurt at all. It was just a weird lump.

Getting the lump examined and diagnosed

The dentist said it could be somewhere on the spectrum of just an infection to a rare form of cancer. She said, “You should go see a specialist.” So she referred me to a specialist who referred me to another specialist. I had a number of scans and I think it was the second or third specialist who said, “I’m not really knowledgeable in this kind of oncology, but I think I might see a malignant growth in your mouth so I’m going to refer you to another specialist.”

I had an indication that there might be a malignancy, but I honestly didn’t believe it. I said, “He doesn’t really know that much about these things. I’m sure it couldn’t be a malignancy. It couldn’t be cancer.” But I did pursue it with another specialist who eventually had me do a fine needle aspiration (FNA). That was when they said it sure is cancer.

What were you thinking before your diagnosis?

He called me on the phone and said, “I know I told you that it wasn’t cancer, but I was wrong. It’s cancer. And it’s this really rare form of cancer that’s incurable.”

I was not worried because when I would see specialists they would palpate the tumor and say, “I’m not sure what it is but it’s not cancer.” The specialist that called me to diagnose me was the one who had ordered the FNA.

When he had seen me in person, he said, “This is definitely not cancer.” He made me out to be a hypochondriac. He said, “You’re just making a really big deal out of this.” I thought, okay great. I’m glad that I’m making a big deal out of it and that it’s not going to be cancer.

But then he called me on the phone and said, “I know I told you that it wasn’t cancer, but I was wrong. It’s cancer. And it’s this really rare form of cancer that’s incurable.” I started asking him questions and he said, “I don’t know anything. I’m on the internet looking it up.” So he was going to refer me to another specialist. I said, “Can you and I call that specialist right now?” He said, “No, I’ll write a letter of recommendation for you.”

Being A Patient Advocate

There’s no one who’s going to care more about your health than you, so you need to be an advocate for yourself and speak up even when other people are not trusting or are questioning you.

How did you feel about your doctor disregarding your concerns?

He didn’t use those words, but research says that communication is 7% the words we use and 93% is body language and tone. So it’s very clear to me in speaking with him that he thought that I was just making too big a deal out of it. Then it turned out to be cancer.

Even though I didn’t believe it was cancer, I wanted to understand what it was and I thought we should get it removed. So I kept pursuing everyone. Each time I would approach a specialist, they’d say, “I can see you in 6 weeks to 3 months.” I kept having to push it in order to get an answer, and when I finally did, the answer was cancer.

How important is it to advocate for yourself?

That is one of the top things. When I do corporate talks or when I go speak to patients, I often say, your health is most important to you. There’s no one who’s going to care more about your health than you, so you need to be an advocate for yourself and speak up even when other people are not trusting or are questioning you. It segues nicely into my second cancer diagnosis.

Addressing a previous health concern

I had the surgery to remove the tumor in my mouth and I was speaking with my head and neck oncology surgeon about the treatment options. I was going to have radiation to treat the salivary gland cancer.

I said, “I have a whole list of questions. Six years ago, I found a lump in my breast and I showed my OB-GYN. She sent me for a mammogram. We ended up biopsying it. I was told it wasn’t cancer. But given that I have this cancer diagnosis, could it be that it is metastatic salivary gland cancer in my breast and they just missed that? Is that possible?”

He said to me, “Sarah, you already have one of the most rare forms of cancer there is. When it metastasizes, it likes to go to your brain or your lungs. So if you have a lump in your breast, it wouldn’t be salivary gland cancer. It would be another primary source cancer. And frankly, we just don’t see it in someone so young. But if it’ll make you feel better, you should pursue it.” So that’s what I did.

Getting a secondary cancer diagnosis

I had to advocate for myself to get the second diagnosis and in a weird kind of world, the salivary gland diagnosis actually saved my life

I walked out once again feeling like, I’m making too much of this. But I thought, let me just check back in and put my concerns to rest. I went back to my OB-GYN and she said, “I know you’ve been doing mammograms every year, but you have really dense breasts, and sometimes tumors don’t show up in mammograms. Maybe we should do an MRI.” I thought, why am I just hearing about this now?

Secondarily, I showed her where we had biopsied the lump in my breast and she said, “Have you ever noticed that the surgical mark and your lump are nowhere near one another? I don’t think they biopsied the lump.” I said, “Oh my God, I have breast cancer.”

We did another biopsy and at that point, I had stage 3 breast cancer. I had to advocate for myself to get the second diagnosis and in a weird kind of world, the salivary gland diagnosis actually saved my life because it caused me to go back and question the lump in my breast.

What type of breast cancer were you diagnosed with?

Estrogen and progesterone positive HER2 negative.

On, the aggressive scale, both of my cancers were in the teens. I got super lucky that both were relative.

Processing A Cancer Diagnosis

How did you feel about your diagnoses?

It seemed ridiculous that there were now 2 cancers. It seemed improbable like cancer was coming to get me. In a way, I relaxed and it accelerated my acceptance of having cancer.

With the first cancer diagnosis, initially, I was numb. I was having trouble processing it. I was diagnosed on a Wednesday. I don’t think I cried until late Thursday afternoon. I was stunned and wasn’t sure how to react and went into project management mode immediately. Like, let me try to control the situation.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

Once I recognized it, I was terrified. I felt like I was in fight or flight all the time, in a panic. I call the book “The Cancer Channel” because it switched on a channel in my brain that was playing all cancer all the time. That’s all I could think about. “Oh, my God, I have cancer. Oh, my God. I have cancer.” I was terrified.

I was strangely ashamed. Still trying to figure that one out. I’m not the only one who has said that. I didn’t do anything to cause this cancer, but there was some sort of embarrassment for having a body weakness. Or maybe it was the embarrassment of talking to people about my mortality or various bodily functions. I was terrified and I wanted to be super private. I wanted to get all of the treatments done, get back into my life, put it behind me, and ignore it.

With the second cancer diagnosis, there was a certain amount of gallows humor that my husband and I developed. It seemed ridiculous that there were now 2 cancers. It seemed improbable like cancer was coming to get me. In a way, I relaxed and it accelerated my acceptance of having cancer.

I was very aware that this [could be] the last year of my life. It was highly likely. And if so, what do I want that to look like? How can I live as gracefully as I can? I decided to become a lot more public. After the second cancer diagnosis, I was telling anybody who would listen to me that I had 2 cancers. I started a blog on CaringBridge to keep people up to speed on what was going on and that really became an outlet for me.

Recognizing the importance of relationships

What became very clear to me, is there is nothing more important than our relationships. Maybe everybody knows that. But when I thought I was dying, the only thing that was important was being with my husband, my closest friends, and my family. Nothing else mattered. My to-do list, which had always been as tall as I was, was reduced to, to live. In doing so, I just wanted to be with the people I loved most.

»MORE: 3 Things To Remember If Your Spouse Is Diagnosed With Cancer

I had been living in San Francisco for 10 years at that point but had been commuting down to Silicon Valley every single day. There were parts of San Francisco I hadn’t explored, so I decided to spend the year exploring the museums, the restaurants, and the little neighborhoods. I did it with friends and my husband. I leaned into all of that.

I haven’t spent a lot of time focused on regret. I just accepted. I had done a lot of things prior and maybe I was coming to the end of being able to do things.

My to-do list, which had always been as tall as I was, was reduced to, to live. In doing so, I just wanted to be with the people I loved most.

As an executive of a major company, how did your views on work change?

What was interesting to me is the cancer diagnosis was very freeing at work. When I eventually went back after a year of cancer treatments, I returned to work in the chief of staff role to the president of eBay, which was the role I had taken on prior to the cancer diagnosis.

I didn’t care as much about getting ahead. I still wanted to do an excellent job, to be valued, to be listened to. I wanted a seat at the table. But having stared at my own mortality, I recognized it wasn’t that important for me to continue to push at work.

It wasn’t that I wasn’t still hard driving. It softened my edges and I was now leaning into how people felt about things rather than how efficiently or effectively can we get things done. I cared much more about how people felt about decisions and how we would take care of people in the decisions that we made as the leaders of eBay.

»MORE: Read more on how others dealt with work after a cancer diagnosis

Was there any difference between your rare and non-rare cancer diagnosis?

When I was diagnosed with salivary gland cancer, I was told it’s super rare, it’s incurable, only 1200 people a year are diagnosed with it, and we don’t have good data. We know that 5 years out, 80% of people are still alive. Ten years out, only 30% of people are still alive. They only had 2 treatments – cut it out with surgery, and then radiate the crap out of it. I leaned in on both. I said, let’s get rid of it and then let’s radiate.

My doctor said it might leave me with dry mouth. I said I can deal with 6 weeks of dry mouth. And he said, “For the rest of your life.” I thought, Oh God. And there are people who have been treated for oral cancers whose reality is now dry mouth for the rest of their lives. I do experience dry mouth, but it’s not extreme.

With breast cancer, when I received that diagnosis they said, “You have a garden variety type of breast cancer. It’s the most common kind of breast cancer. We have a number of treatments for it and we think we got you. We can cure you of it. We’d like to do our favored protocol. We will start out with about 6 months of chemo in the breast. Chemo erases the footprints of cancer in your body. I just want to make sure it hasn’t gone anywhere else and we’re going to make sure by giving you chemo. It’ll also break down the tumor and make it smaller for us to remove so we’ll have better breast preservation.”

What treatments did you receive for your cancers?

A lumpectomy was an option for me and I decided to go with that option. We did 2 kinds of chemo for 6 months, and then I had 2 different breast surgeries because we didn’t get clean margins after the first one. Then I went through 6 weeks of radiation.

They treated me for both [cancers] at the same time, so I was getting radiation to the mouth at the same time that I was getting chemotherapy to my body for the breast cancer.

Chemotherapy intensifies radiation, so after 2 weeks of both radiation and chemo, I said, “I seem to have a little bit of bleeding. Is this normal?” And they said, “It’s normal for 6 weeks in. This is pretty early.” I ended up with 20 cold sores in my mouth and my mouth felt like it was sunburned.

I had a 3 to 4-week period where I couldn’t eat. I would do some chicken broth with truffle salt because it made it better.

How long did you receive treatments?

I [received] surgery to the mouth, started radiation and chemo at the same time, radiation finished after 6 weeks, chemo goes on, and then surgery and the other radiation. So treatments went over a year. It was a full year.

How did you face your anxiety?

The cancer battle is as much mental and emotional as it is physical. At least it was for me. I have, a pretty high threshold of pain that was certainly tested by the chemo and radiation.

I was in so much emotional and mental pain and anguish out of all of my fear, that after the second cancer diagnosis, I went to my breast oncologist and said, “I need help. I’d really appreciate it if you could prescribe an anti-anxiety medication for me because I’m so stressed out. I’m in such a high fight or flight that I’m not convinced I won’t have a heart attack before either one of these cancers is able to kill me.”

So I got an anti-anxiety medication that I would take every day. I called it the “get-the-fuck-over-it-you-have-cancer pill.” I would take the pill every day around 3:00, which seemed to be the witching hour for me. I would hold it together till about 3:00 and then I would just start losing my shit.

One of my best friends was a yoga instructor and I never felt like I had time to go to her classes and certainly didn’t have the mental headspace to be able to do meditation. She said to me, “You have some of the best Western doctors out there. We’re going to call them Team 1. I’m going to be in charge of Team 2, and you and I are going to lean into Eastern practices.”

This friend of mine, Tripti, I started taking her yoga class. I started doing meditation. I did guided imagery. I did energy work and she recommended an acupuncturist. I started doing all of those things to try to relax my body and mind so that I could best accept the treatments.

The cancer battle is as much mental and emotional as it is physical. At least it was for me.

My working theory is that, when I relaxed, the medication was able to work and help save my life. The most important thing was, I relaxed and I didn’t have fight or flight. Then it just became about putting one foot in front of the other. I knew what the plan was. I knew when I had to drive down to Stanford and go for my treatments, and I just did it until I was finished.

Feeling grief over the future

I was 44. I met my husband when we were 38, and I felt like I was busy having a fabulous life. I was so thrilled to have met my life partner, we were pursuing fertility, working with a fertility doctor, and I was so excited about what was to be in my life. I had just gotten promoted into this great role at eBay. I felt like there was so much possibility. Everything was going so right.

I fell in love with this dream of what my future was going to be. I think part of a cancer diagnosis is the death of a dream. I don’t think that that’s too hard or too dramatic a comment to make. I think it’s the death of what you believe the future is going to be. Similar to mourning the death of a loved one, in this case, I was mourning my potential death.

I went through all of the stages of grief. I didn’t have the anger – that’s one of the stages – and I never had the “why me?” I unfortunately watch a lot of news and I understand tragedy happens every day. I was a little surprised that it was me, but I didn’t say, “Why me? This is unfair.” It’s no less fair than anybody else getting cancer. But I was in mourning, I was sad, and I was scared.

Grief is non-linear, and what is surprising is how it will catch us. It will catch us. It’s not surprising that a year or 2 after, you can find yourself talking to somebody about it and tears come quickly to your eyes. I have often described it to people as having a wound on the skin that you keep touching, and it just comes back and shocks you and you’re like, “Oh my God, it’s still so close to the surface.”

I think part of a cancer diagnosis is the death of a dream…the death of what you believe the future is going to be.

I’m now at the point where I can talk about it and laugh. I’m also 10 years out, so that’s a different perspective as well. With breast cancer, the important years are 2 years out, 5 years out, and 10 years out. And generally, they will declare you cured of breast cancer if in 10 years you haven’t had a recurrence. Salivary gland cancer doesn’t have the same type of thing, but I’m in the 30% of people who are surviving that cancer.

Can you reflect on surviving two cancers?

I really think it comes down to being lucky. I also had terrific treatments and I don’t mean to downplay that the doctors were amazing at Stanford. They coordinated my care and both teams of doctors were checking in regularly with one another. They also checked in with me as a whole person, so I felt comfortable talking with my breast oncologist about getting anti-anxiety medication. Every time I talked to her, she would walk into the room, she would grab my leg, she would look in my eyes and she’d say, “How are you doing?” It was amazing.

When you are so stressed out, you think, “Oh my God. I’m going to lose it in front of her. I’m going to cry.” I think the only time I cried in front of her was when she told us we couldn’t have a baby. Other than that, we had very open, honest conversations.

Fertility & Pregnancy

Did you discuss fertility with your oncologist?

After getting the second cancer diagnosis, my breast oncologist called my husband and me back and said, “I understand you were going through fertility treatments here at Stanford when you received your cancer diagnoses. Can you tell me what you’ve heard about your fertility?” She always speaks this way. I try to remember to always ask people “What have you heard?” Because it’s what my understanding is.

I said, “In the event, I live past this year and we get through all the treatments, my fertility doctor said maybe in 2 years’ time we could take the embryos and we could do IVF.” I was 44, so I would have been 46. My breast oncologist looked at me and said, “Sarah, once we finish this year of cancer treatment for the breast, I’m going to put you on hormone therapy. A medication that suppresses your estrogen and progesterone that we’re feeding your cancer, and you need those for pregnancy. I’m going to have you on that for the next 10 years. You’ll be 54 when I take you off those medications and you will no longer be a candidate for IVF.” I looked at my husband and he had tears welling up and he said, “It’s too much.”

He and I often talk about it. We were pretty sure I was going to die. How it is that we thought we were going to have a baby 2 years after I would die, I’m not really sure. But we still held out hope that somehow I was going to survive and that we would have a baby. Then to be told, “You have not 1 but 2 cancers and you will not be able to carry a baby” was devastating for us.

A new study reopened fertility discussions

The great news was, 2 years after we finished cancer treatments and I was feeling optimistic that I might live, I went back for my 2-year check-in with my oncologist. I told her, “We’re feeling bullish and we’re looking into surrogates for the embryos that we have on ice.”

She said, “Sarah, I’m so glad you remind me of this because there’s just been a study done in Europe on Belgian and German women who have breast cancer, who willfully took themselves off the same medication that you’re on. They got pregnant, had babies, and then went back on their medications and we haven’t seen a higher incidence of recurrence. So if you want to have a baby, let’s do it.”

That was pretty amazing news. I went home to tell my husband and he said, “I don’t think this is a good idea.” I said, “Are you kidding me? We’ve just been told we can have a baby.” He said, “But can they guarantee that your cancer won’t come back?” I said, “Sweetie, we never have a guarantee that either of these cancers won’t come back. So really the question is, how do we want to live our lives knowing that? I want to have a baby, I want to experience that.”

So we did IVF and miracles of miracles, I got pregnant and at 48 I had a little baby girl.

Tell us about your daughter

She’s almost 7. Or she would tell you, 6 and 5/6th right now. Her name is Rory Elizabeth MacDonald. I love the name, Jodie. Geoff [my husband] was not into Jodie.

We decided we were probably only going to get to do it once, so we thought it would be most fun if we didn’t know the gender, so we wanted a name that would go either way. We’re not the only people who have thought of this. A lot of people go for the gender-neutral name. I said to him, “Here’s another idea. What about Rory?” And he said, “Oh my God, I love it.” Because our last name is McDonald, all of his cousins and brothers have named their children very Scottish-sounding names. So she is Rory McDonald.

Survivorship

How did you get through your cancer diagnosis and treatment?

We weren’t sure anything was going to be good. It was just one foot in front of the other. I’m going to sound very much like somebody who does meditation, but I focused on breathing. When I find myself getting sad and convinced that I’m going to start crying, the only way I can stop is by breathing through it.

We focused on the everyday, and I went through the treatments as I could. My breast oncologist said to me, “The chemo is doing everything we need it to. Your tumor is breaking down.” Once it had been removed and I did the radiation, she said, “I think we’re good here.” It started to feel like the future could be bright again.

Life was very black and white for a while there, and it went back to Technicolor when we started to believe that I would live.

What’s your advice to someone struggling with anxiety?

A lot of people experience mental anguish and anxiety. I think there’s shame associated with it. Recognize when you need help. At what point is there no going back?

How did I know it was bad enough to ask for help? I could never relax. I couldn’t get a break, and I had trouble going to sleep at night. I woke up early. Some people, when they are stressed out, they go to sleep. I am the opposite. I stop sleeping, so I wasn’t getting rest. Then you get into a spiral because you’re exhausted all the time and you’re crying all the time. I said I need a break from this.

I was beyond embarrassed because I was now, negotiating the end of my life. I thought I don’t want to be this stressed out during this. So my advice for people is you have to take care of yourself just like you would a child who you want to protect and support and nurture. When they are in pain and you want to alleviate that pain, you need to do the same for yourself. I recognized, that if I was going to get through, I needed to smooth out some of the sine waves. I needed to have less of a roller coaster.

[My doctor] gave me the lowest dosage. I would have upped it. There are a lot of people self-medicating with CBD now, and I suggest, if that is what you need to help you get through the tough time, do it.

I also believe in spending some time on Eastern practices. I personally am not a big medication person. I like to believe that my body can take care of things, but sometimes you do need them. I got into the breathing and the meditation and I found guided imagery super helpful to accelerate the mourning process.

What is guided imagery and how did it benefit you?

Guided imagery, for people who are not aware of it, is like meditation but someone’s talking you through it. You don’t have your brain running off like so often you do in meditation, where you have monkey brain and it’s doing all sorts of other things when it’s supposed to be meditating. With guided imagery, someone talks you through a story or a journey. I was blown away by the connection of the head and the heart and the head and the body.

This woman is talking about me walking on the beach and I was sobbing. I did that every day for 6 weeks. I was able to mourn the loss of the future I had envisioned and that’s when I was able to start relaxing.

Tell us about your dad

His name was Paul Brubaker. Dad was an introvert but loved people. He was the guy that was, in a non-threatening way, flirting with the bank teller. He knew everybody’s name and really enjoyed being involved in his community.

He did a lot of fundraising. He coached my brother in sports. My mom coached my sister and me. He was big, loving dad and was horrified when I was diagnosed with cancer. He said, “Oh my God, Sarah. Did I give this to you genetically?” I said, “No. As far as I understand, there is no relationship between prostate cancer and salivary gland cancer or breast cancer. We’re just very lucky people.”

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

He loved to joke, loved to sing. Big tennis and sports fan. Very competitive, not always in a nice way. He went to the University of Michigan to get his Ph.D. and he loved Michigan sports. So much so, that when we were having the conversation about chemo, he said, “It might be worth extending my life just to see if Michigan can have another winning football season.” And he was serious. A couple of years ago, Michigan won the Rose Bowl, or something like that. We all said, “Dad was looking down on that one.”

What was it like being diagnosed with cancer at the same time as your dad?

He was diagnosed at 64 with prostate cancer, which is a really awkward age to get diagnosed with prostate cancer. They often won’t even treat men in their 80s or 90s. They say that you’re going to die from something else before you die from prostate cancer because it’s so slow growing.

They were recommending surgery that could have side effects, including incontinence. Dad was pretty focused that he didn’t want to be in a diaper. Or he could just do radiation and pulverize the cancer. He spoke with a couple of oncologists and chose radiation.

Unfortunately, 10 years later he came to visit us in San Francisco right around Christmas. He’s in Southern California, so it’s warmer down there. It’s a cool, wet December and he couldn’t get warm. He kept saying, “I can’t get warm and my bones are aching.” I said, “You need to go talk to your doctor and see what’s going on.” The cancer had metastasized to his bones, so he had prostate cancer in his bones. Then I was diagnosed. We were quite a pair.

How did your dad react to his cancer diagnosis?

I said with my first cancer diagnosis, I was really private. But with my second I wasn’t. I also knew that I was going to be going through chemotherapy and that I would be bald for a period of time so it was going to be public.

My dad was super private about his cancer and didn’t want anyone outside of our immediate family to know. And when the cancer had metastasized, his oncologist said, “We should talk about chemotherapy.” My dad said, “No. I’m not going to do it.” I said, “Dad, what do you mean you’re not going to do it?” He said, “I don’t want to be bald and I don’t want people to know that I have cancer.” I said, “Dad, it might save your life.”

»MORE: Dealing with hair loss during cancer treatment

He probably turned down chemo for 6 or 7 months before he finally agreed to do it. By that time, the cancer had progressed more and he felt so lousy every time he got chemo.

I did not have huge side effects from chemo. I was dry. They talk about how everything becomes dry, and I would get really flushed and I had some nausea, but some bodies are really debilitated by chemo. That was not my case. I could do chemo and go running the next day. I know that’s unusual.

My dad went from playing singles tennis to not being able to walk around the circumference of his house. He was using a walker and just feeling lousy all the time. Eventually, he stopped chemo and said, “With the time that I have left, I don’t want to feel lousy all the time.”

To be clear, I was still living in Northern California and he was in Southern California. I would go visit. I wasn’t working. I was on long-term disability so I could do my chemo and then fly down south to spend a couple of days with him, which I was prioritizing.

Did your relationship change with your dad after your diagnosis?

What was remarkable was the change in our conversations. We could have much more open conversations about the failings of our bodies, but also, how we were feeling about our mortality. I don’t think he was having those conversations with my mom, not wanting to give a voice to his eventual death. But we could have conversations about it and about his frustration that his cancer was spreading, his frustration that the medication was no longer working.

He said, “Why is it working for you and it’s not working for me?” He was my father, so we should have very similar bodies. But we do have different bodies. We had different cancers, different ages, different stages of cancer, and different aggression levels, and he had delayed his treatment.

Describe what it was like making different cancer care decisions than your dad

It was remarkable to make different decisions from someone that I love, like his decisions on chemo and his decision to delay. I had to do a lot of accepting that we were doing cancer differently and that it wasn’t up to me to tell him how to do it. I learned the hard way.

I suggested because he was having heart issues as well, “Your doctors are coordinating your care? Your oncologist is talking to your cardiologist, right?” He said, “I don’t know.” I said, “Doesn’t it seem like they should know about the medications that one another is giving you? A lot of medical centers have something called a patient advocate who can go with you to all of your appointments and help coordinate your care.” My father was furious with me for suggesting that. “How dare you question my doctors? If I were to bring somebody else into the room, that would be so disrespectful to the doctors. Who am I to question their care?” I said, “I was misdiagnosed. I could have died. I understand that doctors are human and they make mistakes and I would bring out anyone and everyone who could advocate for me.” Very different approaches.

I had to get comfortable with the fact that his approach was different than mine. That was his right. I said to him, “I want you to do chemo because I want you to be here as long as you can be here. I’m afraid of being without my dad. But I don’t wish that sickness on you. I don’t wish that shame that you think you’re going to have. I don’t want any of that for you and you get to make the choice.”

Reflections

What inspired you to write your book?

I originally set out to write a guidebook for the newly diagnosed because, what I discovered when I was diagnosed, there’s a whole language around cancer that I didn’t know or understand. Once you’re in the cancer ecosystem, you get it. But there’s such a steep learning curve, so I originally wrote a guidebook for the newly diagnosed.

When I tried to get it published, I was told, “No one will ever read a guidebook by a patient. They will only read them from experts and doctors.” I said, “I strongly disagree, but I guess you’re in the publishing industry.” They said, “You have a good voice. You should write a memoir.” I said, “That sounds arrogant and self-absorbed, and I hope I am neither of those things, but let me lean into that.”

I wanted to write a book for people who had cancer and were having trouble articulating what it is like to have cancer. I hoped that they would read the stories, see themselves and their experience and they could share it with the people they love and work with and say, “This says what I can’t say.” That’s what I hoped and that is the feedback I am getting. I am so grateful. I have a number of current cancer patients who have reached out and said, “Thank you. I feel a little less alone. I feel like, in the dark tunnel of cancer, maybe there’s some light.”

It is a love letter to people who have cancer, and it can also be a love letter to friends, family, and co-workers. I’ve had people say to me, “My mother and my best friend both died of cancer. Had I read your book, I would have shown up differently.” Those are the reasons I wrote the book.

The importance of talking about cancer

It’s really hard to talk about it. But we can do hard things and we need to practice having those hard conversations so that we become more practiced and more relaxed. So we can actually show up for one another and help people feel a little less alone.

I would be remiss if I didn’t remind your audience that the American Cancer Society tells us that 1 in 3 women will be diagnosed with cancer during her lifetime. For men, it’s 1 in 2. So it’s not a matter of if you will know someone with cancer, it’s a matter of when.

Now I am using my book to get people to talk about cancer. I’m talking at a lot of corporations and a lot of medical conferences. I tell the audience who says, “I don’t know someone who has cancer” or “I don’t know how to talk to someone who has cancer.” I say, “It’s really hard to talk about it. But we can do hard things and we need to practice having those hard conversations so that we become more practiced and more relaxed. So we can actually show up for one another and help people feel a little less alone.” That’s my message when I am on the corporate speaking track.

Keeping humor in conversations about cancer

My mom’s book group refused to read it because they said, “We don’t want to read a cancer book.” I do make it funny because there’s some ridiculous stuff that goes on and you have to laugh about it. I had a number of people say, “Oh my God, you had me laughing and crying at the same time.” I said, “Awesome!” You have to laugh in order to get through.

In my blog, I turned to humor while I was going through cancer. In the for-profit world and the not-for-profit world, we set up key performance indicators that we hold ourselves to. So I set up key performance indicators for my cancer treatment, and I would report to the audience every time I did a blog, sharing with them how I was doing on my KPIs. That’s my kind of humor, and if that’s not funny to you, don’t read the book.

What’s your biggest advice for cancer patients?

Stop whispering about cancer. Let’s talk about it in full voice. Let’s all practice so we can show up for one another.

We hit on some of my biggest insights, which were, you got to be your own best advocate, take care of yourself in this, and ask for help. The most important things are the people in our lives, our relationships.

The biggest thing that I want to shout from the mountaintops is, we’ve got to stop talking about cancer in a whisper like, she has cancer. We need to talk about it in full voice. People say, “I don’t want to talk about it because it’s scary and I’ll give power to cancer.” But by keeping it in the shadows, that’s where we give it power.

I have found now that I’m less afraid to talk about cancer. I’m less afraid to talk about mortality. I’m able to talk with people who are in crisis in other ways because all I’m doing is asking the question that is in the mind of the person going through the crisis, and I’m able to hold space for people that way. So my encouragement is to stop whispering about cancer. Let’s talk about it in full voice. Let’s all practice so we can show up for one another.

Where can people purchase your book?

It’s on Amazon, but you can go to your local bookstore and order it. I always love to give a little plug for Book Passage. It’s a San Francisco-based independent bookstore, and that’s where I buy all of my books.

Where can people find you?

At TheCancerChannelBook.com. If they wanted to email me, I’m sarah@thecancerchannelbook.com. You can go to my website, you can read about the book, you can read excerpts, and you can listen to me reading excerpts.

More Breast Cancer Stories

Amelia L., IDC, Stage 1, ER/PR+, HER2-

Symptom: Lump found during self breast exam

Treatments: TC chemotherapy; lumpectomy, double mastectomy, reconstruction; Tamoxifen

Rachel Y., IDC, Stage 1B

Symptoms: None; caught by delayed mammogram

Treatments: Double mastectomy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, hormone therapy Tamoxifen

Rach D., IDC, Stage 2, Triple Positive

Symptom: Lump in right breast

Treatments: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, double mastectomy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy

Caitlin J., IDC, Stage 2B, ER/PR+

Symptom: Lump found on breast

Treatments: Lumpectomy, AC/T chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy (Lupron & Anastrozole)

Joy R., IDC, Stage 2, Triple Negative

Symptom: Lump in breast

Treatments: Chemotherapy, double mastectomy, hysterectomy