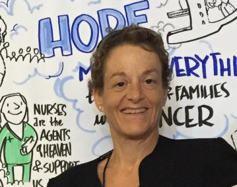

Financial Toxicity of Cancer Treatment: Dr. Chino Shares Her Story

Fifteen years ago, Dr. Fumiko Chino was the art director at an anime company, getting ready to marry the love of her life, when her fiance was diagnosed with cancer.

Today, she’s a radiation oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering and studies the impacts financial strain has on cancer patients.

She opens up about her late husband’s diagnosis, the financial toll it had on them, and how she’s determined to help alleviate the financial burden for other patients and their families.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Introduction

- How did you and your husband meet?

- Getting the cancer diagnosis

- Course of treatment

- What was it like being a care partner?

- Looking back

- The aftermath of your partner’s death

- Financial toxicity of cancer treatment

- How to dispute cancer care costs

- What inspired you to get into medicine?

- The impact of cancer treatment on Black and Latinx Americans

- Honoring Andrew’s memory

Introduction

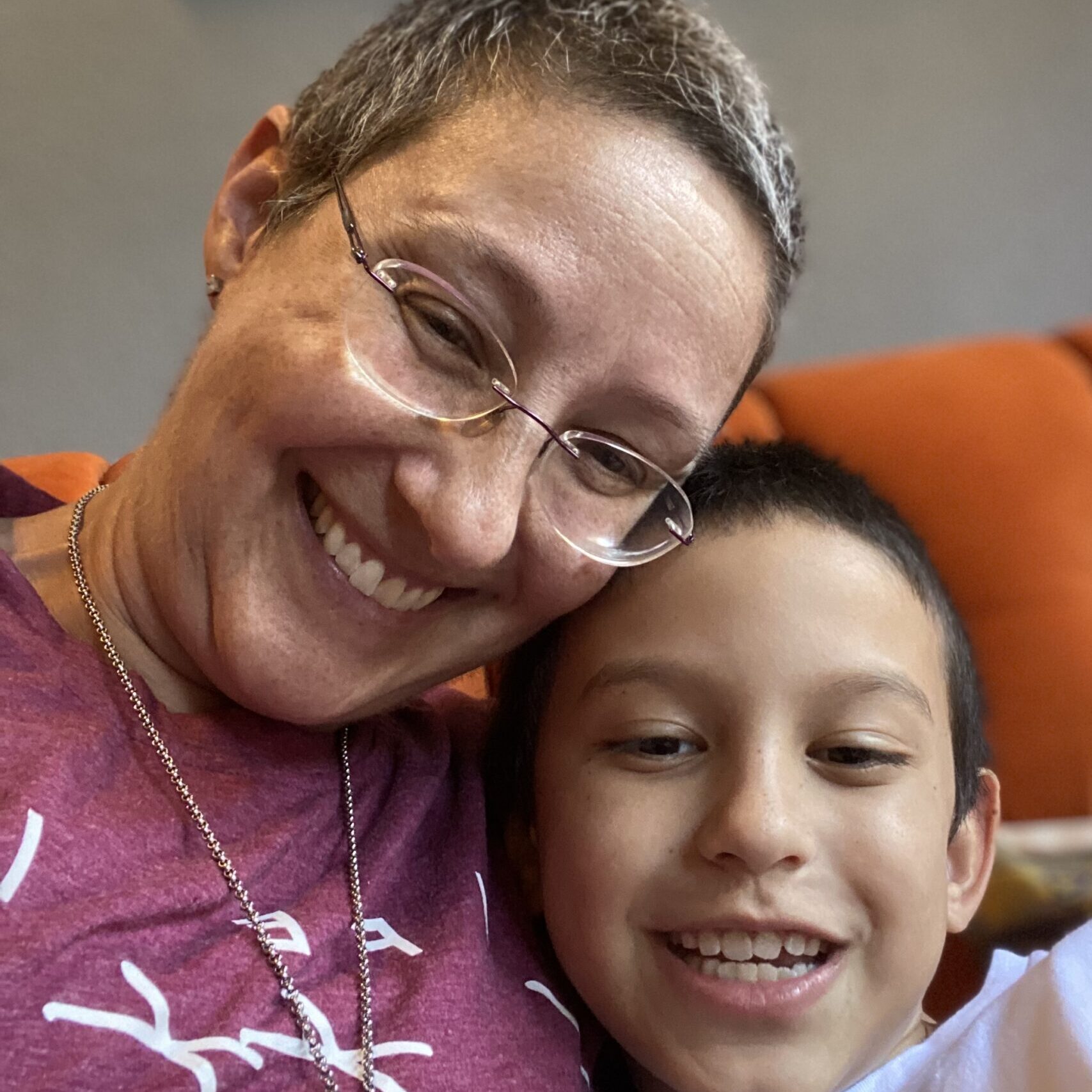

I’m a radiation oncologist specializing in the treatment of breast and gynecological cancers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

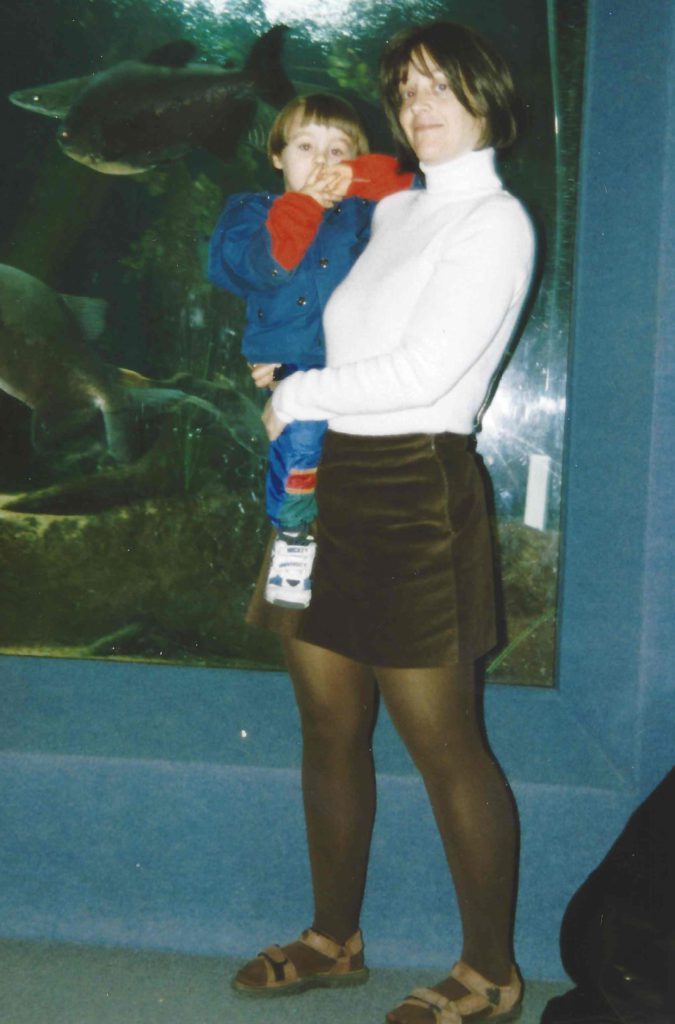

I met my husband in 2004. He was diagnosed with cancer in 2005 and died from cancer in 2007.

How did you and your husband meet?

I first met my husband online. We were an early Internet couple. We met on a site called Nerve, which is where the cool kids used to meet to date.

He was a PhD student in computer science at Rice. We met in Houston, Texas. At the time, I was in entertainment. I worked as an art director [at] an anime company. Most famously, I worked on Sailor Moon.

I called him Mr. Roboto. He’s a computer scientist who specializes in robotics and artificial intelligence-derived motion.

He’s a very frantic guy. He was very driven. He was very passionate about his work and also about music and art. In that way, we kind of really dovetailed.

It was so quick, it was so aggressive, and we were so terrified.

Getting the cancer diagnosis

Like many 20-somethings, I was still trying to figure out my life. I was so happy to have met someone that I was in love with [and] that I could envision a future with.

When my husband, at the time boyfriend, was getting sick — he was having nausea, throwing up, [and] losing a lot of weight — we really thought it was not cancer. No one [who’s] young thinks, “Oh, this is cancer.” It’s everything other than cancer.

It took a little bit of time to find his actual diagnosis, [which was] high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma.

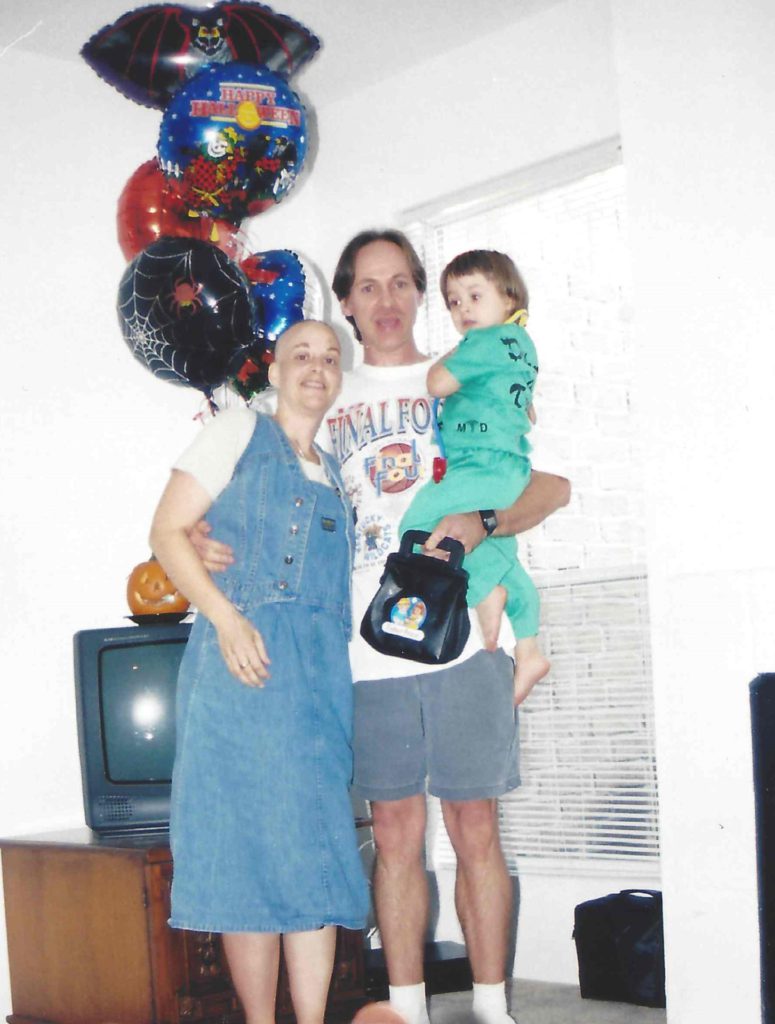

We had just gotten engaged. We were planning our future, our family. It was just devastating. A cancer diagnosis [when you’re young] completely interrupts your plans.

What we didn’t realize was in addition to how emotionally and physically taxing it would be [was] how financially taxing it would be.

He had had a number of false diagnoses before he came up with cancer. He was told he had IBS. He was told he had celiac disease because he had a lot of cyclical nausea, vomiting, [and] weight loss. He ultimately went in for an endoscopy [and] they didn’t find anything.

They finally did a CT scan and found all of these enlarged lymph nodes throughout his thorax and, particularly, a mass that was compressing his pancreas, which was causing his GI dysfunction.

When they biopsied it, they found that it was not lymphoma, which is what we thought it would be. I knew we were in for a delightful cancer adventure with [an] unknown destination. It was such a long time period between the initial workup and when we actually found out what kind of cancer he had.

We had just gotten engaged. We were planning our future, our family. It was just devastating. A cancer diagnosis [when you’re young] completely interrupts your plans.

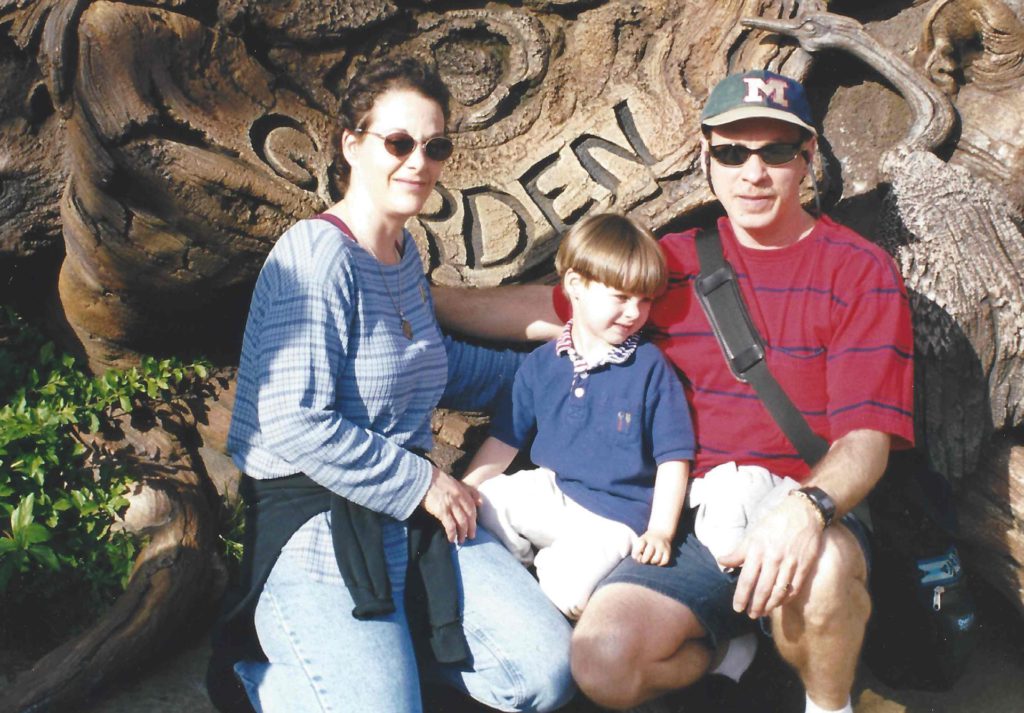

We actually jumped ship in Houston and I manifest my own privilege by going to where my mom is a radiation oncologist. We went to her facility to facilitate the workup.

I think like many young people though, it was so quick, it was so aggressive, and we were so terrified.

I remember having [a] discussion about whether or not we should do sperm banking. They said, “It’s going to delay the process of starting chemotherapy by about a week.” It actually takes way less [time] for a guy than it is for a woman, but even that week felt important because you could actually feel the lymph nodes in his neck growing. And so we said, “We won’t do that. We’ll just move forward with chemotherapy.”

He started on a Saturday. In medicine, when I say he started chemo on a Saturday, they’re like, “Oh yeah, they really wanted him to start because no one starts on the weekend.” We were just terrified.

We didn’t realize that insurance was going to be a problem. At that point, insurance had kind of covered everything.

Course of treatment

He started the treatment for intense chemotherapy, platinum-based therapy, on a Saturday. By Monday, when he saw his oncologist, he could feel the difference. It actually responded that quickly, which made us think it was the right thing, even though we knew it was a sacrifice for our imaginary future children.

He went through many, many cycles of that, had a good partial response, and had a little bit of a break. Then [he] had progression and ended up being off therapy for maybe a couple of months tops. He was pretty much always on treatment from the time he was diagnosed until the time he died within a year and a half of his diagnosis.

We didn’t realize that insurance was going to be a problem. At that point, insurance had kind of covered everything.

What was it like being a care partner?

Nobody signs up to be a patient and nobody signs up to be a caregiver but you do it because you’re trying to survive and you’re trying to support the people you love. I was so impressed with him [and] his resilience [in] being able to continue working as a computer scientist through really intensive treatment.

He always said — and this is something that he would have researched so I trust him — that he received more platinum-based therapies than Lance Armstrong did. He had a lot of cycles of chemotherapy.

He had standard nausea, vomiting, [and] weight loss. He had diarrhea, incredible pain, [and] a lot of anxiety. It was this constellation thing, which means that we were in the emergency room all the time. We were admitted to the hospital multiple times.

He dealt with a series of infections and it was just a lot to balance everything. I was still trying to work. I think our income was important to preserve as well.

At one point, I remember he wasn’t answering his phone. I texted him, “Are you doing okay?” He didn’t answer the next. Two hours later, I called him. He didn’t pick up the phone and at this point, it’d been four and a half hours [I’d] been trying to get ahold of him. I ended up actually driving home from work to check on him. He was just doing computer science coding.

Looking back

It’s really interesting because I actually tell my story fairly frequently because it’s a motivator for the research that I do. My spiel is pretty well-polished but sometimes, if I’m trying to provide a little bit more detail or color, I’ll think of a story and it brings up those memories and those hopes and fears that come along with that.

Because I’m interested in oncofertility, [I] just recently realized that that process — the delays, the fear, and also the costs — is a real barrier to a lot of people taking advantage of that. They may end up surviving cancer but then having some other fundamental freedom removed from them.

Trying to be a new widow — I was 29 trying to reinvent myself and my life — was just really challenging.

The aftermath of your partner’s death

There’s no guidebook for great loss and there [are] many manifestations of it. I think it kind of hits you like waves. This is what changed. This is what’s different. This is what my future is.

I was uninsured after he died, actually, for almost two years. I lost my health insurance with his loss.

I also lost my purpose. I had these debts. We had moved to Michigan for his faculty job and I was sort of stubbornly sticking out there. I didn’t actually have a support system there either. I coupled one together. Cancer and any serious illness really expose the fault lines.

Nobody really has it together in their 20s anyway. Trying to be a new widow — I was 29 trying to reinvent myself and my life — was just really challenging.

We had his student health insurance from Rice, which basically had a lifetime cap for its payouts for a single diagnosis — something that was allowed before the Affordable Care Act. A single diagnosis would cap it [at] $500,000. And after that, there was no more insurance coverage for that diagnosis. That is something that we met within roughly a year of his diagnosis

Financial toxicity is incredibly common and, unfortunately, it’s going to manifest in someone in your clinic even if you don’t see it.

The first exposure [to] the fact that his health insurance was poor was that he had a cap on his pharmacy payout. That one we ran up pretty quickly, within several months of his diagnosis. It was a $5,000 payout, which is insane because a single cancer medication can sometimes cost $5,000. But we blessedly didn’t find out until later.

When we started having to pay out-of-pocket for his Zofran, Lovenox, medications for his anxiety, [and] pain medication, that’s when we first found out. That was sort of the blood in the water then the sharks come and we were just under.

You hit that cap and suddenly you’re in no man’s land. People will describe this [as going] into the donut hole or they reach some sort of limit and you’re in catastrophic territory.

If physicians and patients are both unwilling to talk about this dirty underbelly of cancer care, then it’ll never be properly addressed.

Financial toxicity of cancer treatment

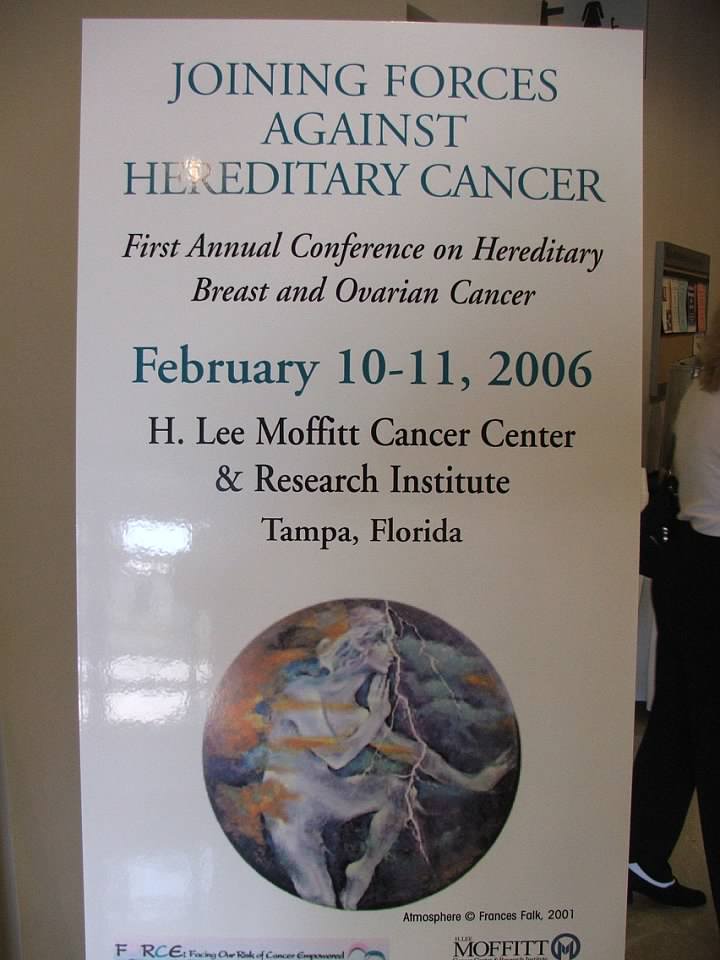

I always try to highlight financial toxicity. I’ve dedicated my life to researching financial toxicity, access, affordability, and equity. It’s all part of the same sphere. How do we get people the best cancer treatment?

Financial toxicity is incredibly common and, unfortunately, it’s going to manifest in someone in your clinic even if you don’t see it. They are going to see you and if you don’t see them — the whole them, the whole picture for them — you may miss it and you may miss an opportunity to intervene. My baseline is that this is common and you’re going to see it even if you don’t think you’re seeing it.

The second thing I try to emphasize is that there are really discrete effects of financial toxicities on our patients. People are not able to afford their medications. People [have] to skip out on visits. People are not getting the mental health care that they need. They’re not getting the dental or vision care that they need. Sometimes they’re missing scans. And for some people, they’re actually missing treatments.

I always try to emphasize that there are things we can do about them. There are things that we can do on the health policy level, at an institutional level, and within our own clinic to try to improve outcomes for financial toxicity.

The first step is always just saying it’s okay to talk about it. This is the thing about sexual health or fertility concerns. We need to take the Band-Aid off. We need to say it’s okay to talk about these things. If physicians and patients are both unwilling to talk about this dirty underbelly of cancer care, then it’ll never be properly addressed.

You can start little or you can go big. There’s really everything in between from parking to policy. You can really make your voice heard.

How to dispute cancer care costs

Pick a thing that you want to intervene [in] and then work doggedly towards it. If you want to take one thing — let’s just say parking cost, something that pretty much everyone agrees [is] ridiculous — that can be your advocacy issue.

You can take every meeting from the director of parking services to the CEO of the hospital — if you can get in — and say, “This is why this is important. This is why we need more vouchers. This is why parking decks should be free. This is why parking is a stupid barrier to receiving care.” And yet it truly is.

The reason why I researched parking costs is [that] we were paying $18 a day to park at MD Anderson. No offense to MD Anderson. I lived in Houston for many, many years. I volunteered at the Texas Medical Center. I know that parking is the biggest revenue generator for the Texas Medical Center. Texas is huge. Parking shouldn’t be an obstacle to receiving care.

You can start little or you can go big. You can think, “How do I lobby at the public policy level? How do I get my face in front of senators or representatives that can actually make meaningful change in how health insurance is designed and delivered?”

There’s really everything in between from parking to policy. You can really make your voice heard.

What inspired you to get into medicine?

I was sleeping on the floor of an ICU on a collapsing air mattress when my husband was during his terminal hospitalization. That was my light bulb moment. I think I should go into medicine because I feel like I can try to make a change.

My initial thought was I’m going to be a nurse. I talked to my sister, who’s a physician, and she said, “You don’t want to go into nursing.” I was like, “They’re great!” And she’s like, “Oh, I agree. They’re like saints. There’s a hierarchy in medicine and physicians are at the top. You as a nurse who is going to be smarter” — as many nurses are — “than the physician who’s telling you what to do, it’s going to make you frustrated. Your personality type does not sit with that so you should be a physician.” I thought about that more and I thought, “You’re right.”

Transitioning into medicine was a challenge. I had to go back to school. I have a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. I had to do some post-bacc classes, but it was absolutely the right decision for me.

The impact of cancer treatment on Black and Latinx Americans

This system needs to change. There are many social injustices in the world. We can’t fix all of structural racism. We can’t give everyone the world-class education that I have been privileged to [have]. Yet we can make some differences and every little bit helps. It’s all about incremental change.

Honoring Andrew’s memory

I will think about Andrew every single day. The thing is that this is mission-driven research. This is mission-driven care. My care is for the best outcomes for my patients, but for all patients, right?

I can’t save Andrew, but I can maybe make cancer treatment a little easier for the next person.