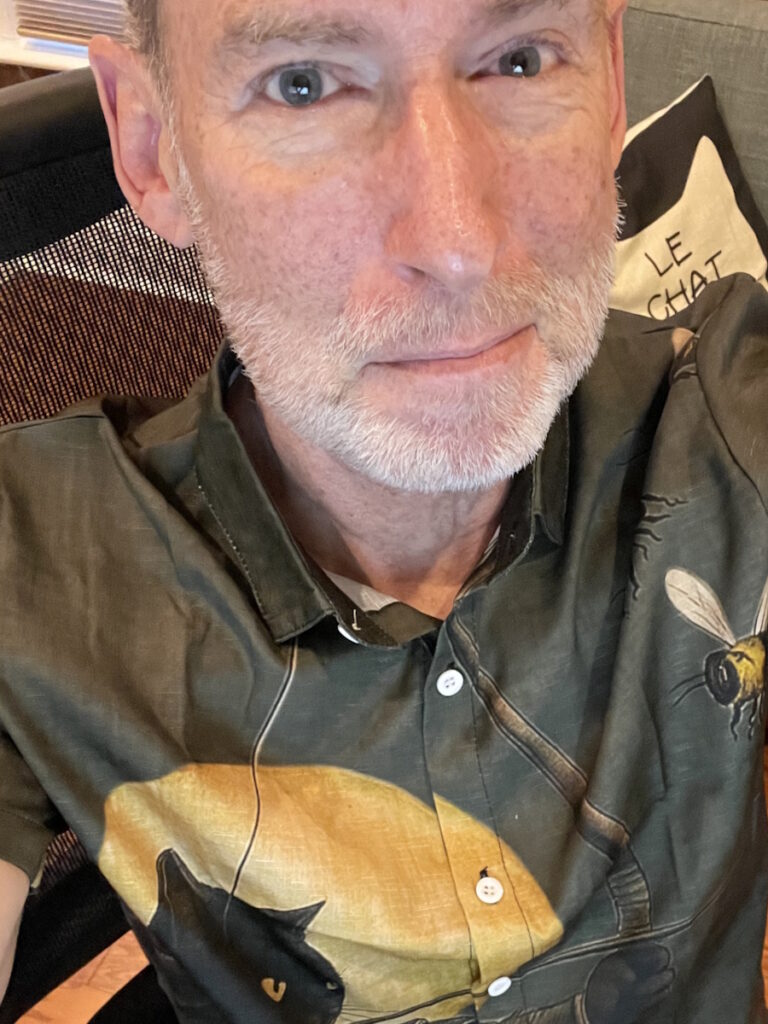

Dr. Ross Camidge: I Have Stage 4 Lung Cancer

World-renowned Lung Cancer Expert Shares His Experience Becoming a Lung Cancer Patient

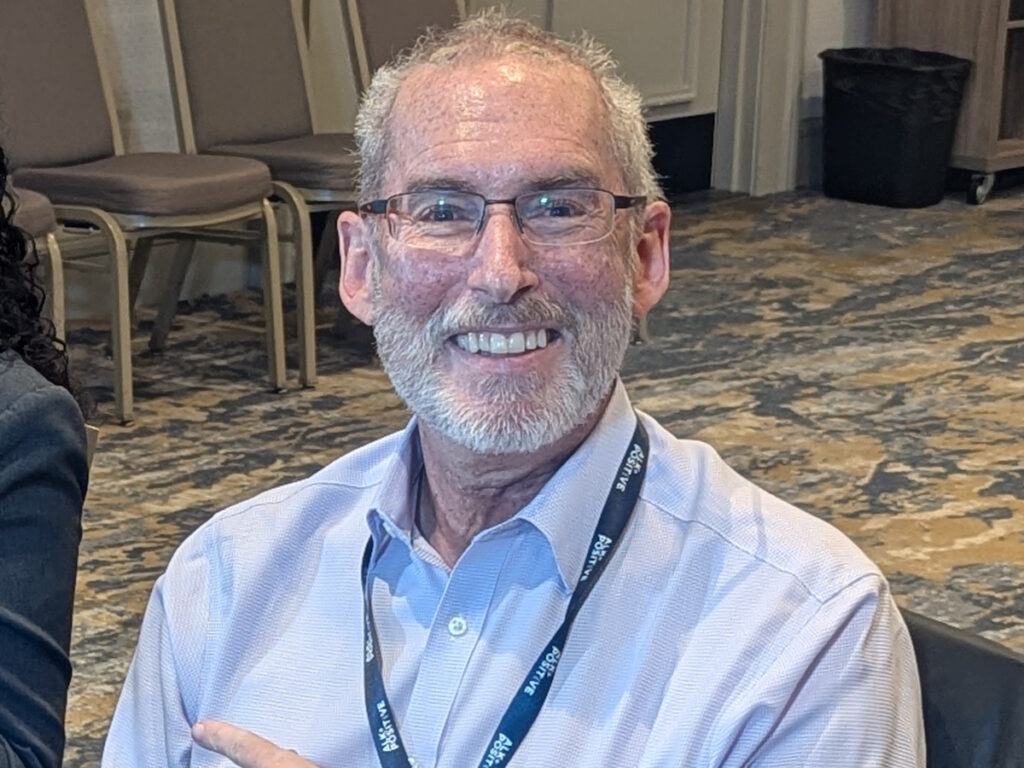

If you look up Dr. Ross Camidge, you’ll see the incredibly extensive work he’s done in lung cancer research for over 20 years, fighting for his patients and for others. Lung cancer patient advocates have long described him as a true patient-focused oncologist who has devoted his life to saving lives.

Now he’s sharing that he is trying to save another life — his own — after becoming a stage 4 lung cancer patient. As a leading oncologist at the University of Colorado, Dr. Camidge has had to manage this seismic shift from physician to patient.

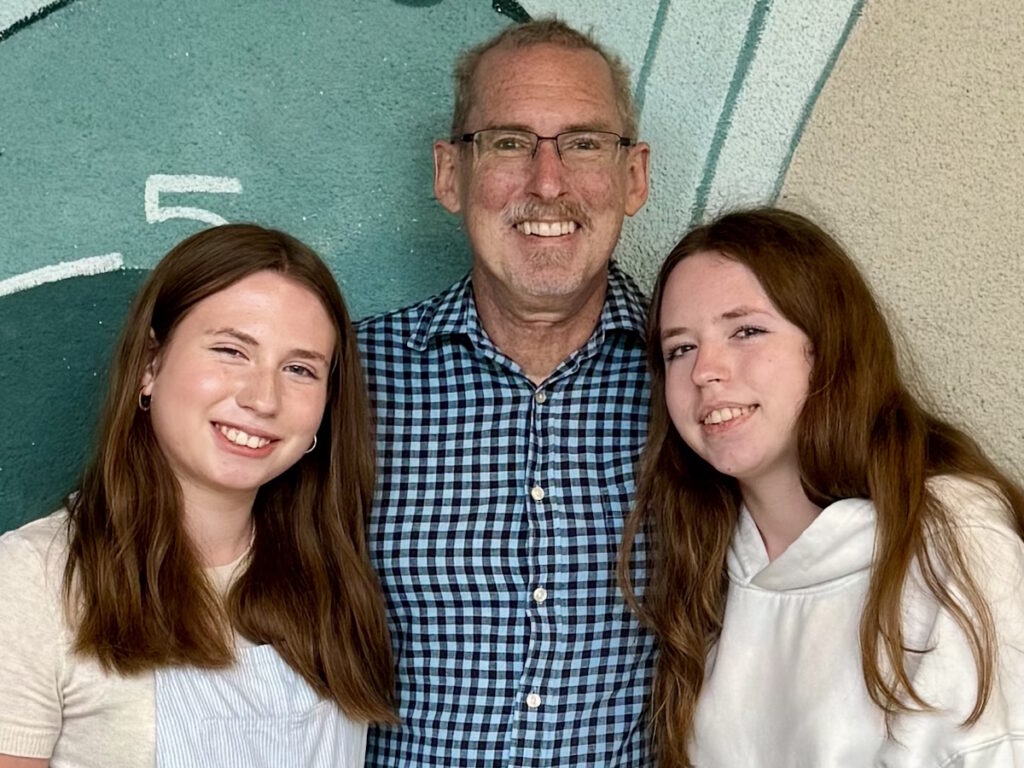

Symptoms began subtly, manifesting as shoulder pain and changes in his breathing, and led swiftly from a chest X-ray to comprehensive scans revealing widespread disease, including metastases to the brain and bones. Dr. Camidge’s rapid transition from observer to recipient of care highlighted not only the emotional strain but also the necessity of maintaining routines within his family. His daughters, then aged 10 and 12, became central to his motivation, their everyday lives anchoring him amid uncertainty.

Dr. Camidge describes his cancer as an “uneasy neighbor” — no longer cured, but not dying, responsible for periods of disruption and adaptation. His story is marked by determination to keep living fully in 90-day cycles, carving out time for new experiences and mentoring others in medicine and life.

Thank you, Dr. Camidge, for all you do for patients and for sharing your story to help others.

Interviewed by: Stephanie Chuang

Edited by: Stephanie Chuang & Katrina Villareal

Introduction: Dr. Ross Camidge

Deciding to Become a Doctor

I decided that I wanted to become a doctor at around 11 or 12. It was either that or a veterinarian, mostly because it was easier to examine dogs than people. But that changed somewhere along the way.

Medical school is an undergraduate degree in the UK. I started medical school at 19. I was a year older than most of my peers because I’d taken a year off to travel the world. Compared to America, we were all ridiculously young. I went to the University of Oxford for my first three years of medical school and then did a hard science PhD at the University of Cambridge. I worked in a lab for four years and came back to clinical medicine a little older and wiser.

The PhD had been a bit of a disaster, so I learned to deal with failure as much as success. I went into clinical medicine with the mind of a scientist but the soul of a physician. It was like doing an experiment where the person was the experiment: trying to make a diagnosis and intervening with treatment. Unlike those four years in the lab, I could show success in a matter of hours in patients like Mrs. Jones in front of me, and I liked it.

I was relatively socially awkward, but being a physician gave me the opportunity to talk to people. They would listen to me and I would listen to them. It was a social tonic for me.

I didn’t know when exactly I wanted to become an oncologist. It became fascinating after several years into my training, before I started an attachment in oncology. It seemed to combine skills I’d developed along the way. These things always appear to have a narrative in retrospect, but it was random noise at the time. Oncology had molecular biology, science, clinical trials, and a very strong interaction with the patient.

A diagnosis of cancer strips away the nonsense in conversations. You don’t talk about the weather; you get down into the nitty-gritty of someone’s life. Now we keep people alive for years, so it becomes a very close relationship, which I’ve gained from enormously and hopefully my patients have, too.

A diagnosis of cancer strips away the nonsense in conversations.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Choosing Lung Cancer as a Specialty

You’re influenced by what happens along the way. I was training in Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. At the time, breast cancer had all the money and all the breakthroughs, but it was incredibly crowded — where the “cool kids” went.

Lung cancer was very common, especially among the working class in Scotland, and there was a huge unmet need. The patients were — and still are — the most wonderful because, for whatever reason, they don’t ask, “Why me?” They’re very accepting and humble. Many of them were smokers, which made me want to take a step towards them.

During that time, targeted therapies for lung cancer were being developed. I got a glimpse that molecular biology was going to go mainstream and that genes would become part of everyday oncology care. I saw the future: patients I liked, a huge unmet need, and exciting science about to happen. That’s why I ended up specializing in lung cancer.

There was a huge unmet need. The patients were — and still are — the most wonderful because, for whatever reason, they don’t ask, ‘Why me?’ They’re very accepting and humble.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Life Outside Medicine: Humor and Personality

If my wife or best friends described me, I think the first thing they would say is that I have a sense of humor. Almost everything can be turned into something that makes me or someone else laugh. Even a trip to SuperTarget can get my wife giggling about whatever we’re talking about.

There’s fun in life. People are often surprised in my clinic because I don’t distinguish between me as Ross and me as a doctor. There’s a lot of laughter; it’s a great relaxer and leveler. Over the years, patients poke fun at me, which I love.

Do I have time for hobbies? I don’t have pastimes — no time that needs passing. As my health changed, I decided there were things that I at least wanted to try. Typically, I would work, spend time with my two teenage daughters, exercise, and occasionally cook. Like all men, I think I deserve a medal when I cook because I don’t do it often.

I am very clean with dishes — that’s one of my stipulations. I try to instill that in my youngest daughter, who likes cooking with me: you have to tidy up as you go along.

People are often surprised in my clinic because I don’t distinguish between me as Ross and me as a doctor. There’s a lot of laughter; it’s a great relaxer and leveler.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Humor and Communication With Patients

My humor doesn’t usually involve jokes with a beginning, middle, and end, but my favorite, which comes from Christmas with my girls, is: Two snowmen talking and one goes, “Can you smell carrots?” You have to have the visual image.

The difference between a good joke and a bad joke is the audience; timing is everything. You don’t tell a joke immediately after giving a cancer diagnosis. The purpose is to remove stress and barriers. I don’t wear a white coat and I try very hard to remember the language I used before becoming a doctor. You don’t use big words or technical terms like Kaplan-Meier curves unless necessary. Communication is the goal and not to show how clever you are.

Communication is the goal and not to show how clever you are.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Discovering the Diagnosis

My First Lung Cancer Symptoms

My mum, who was 90 at the time, came from Edinburgh to stay with us in 2022. As she improved, she insisted on returning to Edinburgh in May that same year. Around that time, I felt like I pulled something in my left shoulder after exercise, so I had a massage. The person said it was tight. It loosened up and then returned, but I didn’t think much about it. I thought I was just getting older.

Around the same time, I noticed that when I slept on my right side, my breathing sounded different. I was doing a two-phase exhale where there was a slight wheeze at the end. I wanted it to be asthma, but I kept wondering why it happened only on one side.

I tried my wife’s inhaler, which helped a bit, but I made an appointment with my primary care physician, who was a locum. He went down the asthma route, prescribed something, and said that if it didn’t work, we’d do something else. I said, “By the way, I’m a thoracic oncologist. Could we just do a chest X-ray?” He complied and I had the X-ray right away.

While I was checking my emails, the GP called and said, “There’s something on your chest X-ray; you need a CT scan.” As he spoke, I pulled up the X-ray and instantly knew it was lung cancer. There was a mass at the top of my right lung and a partial collapse.

I also saw dots in the other lung: metastatic.

I called my wife, who was with the girls on vacation, and told her not to worry and to go about her day. That same afternoon, I had a CT scan and saw that the cancer had spread. There was a mass in my right lung, lymph nodes in my chest, and bone deposits. I knew it was metastatic. A radiologist friend, who normally doesn’t interact directly with patients, called to tell me and apologized for the news; it was hard for her, but very touching.

There was a mass in my right lung, lymph nodes in my chest, and bone deposits. I knew it was metastatic.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Scan Results

Saturday brought a PET scan and Sunday an MRI of the brain. The cancer had spread, with deposits in my brain, including the brainstem. The brainstem is only about an inch-and-a-half across, and I had a deposit about an inch wide — not compatible with life, yet there I was looking at it.

Monday, I had a bronchoscopy and a biopsy, performed by a friend; another friend, a pathologist, was present to confirm sampling. I didn’t pull favors; they just did this. From the chest X-ray on Friday morning to Tuesday morning, I knew I had a specific mutation, metastatic cancer, and the right treatment as an expert in the field.

Sometimes, when a patient passes, their family gives me unopened bottles of pills, which help others start therapy. Weeks before, I’d gotten just such pills from a patient’s family, which were the ones I needed, so by Tuesday afternoon, I started them. Later, I called the patient’s husband, saying his wife would be pleased we used her pills to start someone on therapy early — I didn’t say that it was me.

The GP called… As he spoke, I pulled up the X-ray and instantly knew it was lung cancer.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Processing My Stage 4 Lung Cancer Diagnosis

Family, Emotions, and Planning

Having spent 20 years doing this, responding was automatic and professional, but reality would intervene. In the evening, my wife and I would sit on the stoop and cry, talking through what to tell the girls, who were 10 and 12. We wanted a plan with all the facts and treatment, so that the message was not a period at the end, but a dotted line into the future.

A week after the X-ray, we told them: Daddy has the same condition as his patients, he’s started therapy, and he’s on a pill. It’s not a cure, so the cancer’s not going away, but you’ve met some patients at fundraising events, and they’re doing well.

My eldest asked, “Are you going to die?” because that’s what teenagers say. It’s not a yes or no; it’s “Well, it’s not curable, but we’ll see how it goes. We’re not going to ask anything more of you; maybe I’ll ask for a hug, but your life stays the same.”

My eldest asked, ‘Are you going to die?’

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Reconciling Being Both Doctor and Patient

People say, “This shouldn’t happen to anyone, but especially not to you,” but I don’t think anyone deserves cancer more or less than I do. If anything, I know about it, so I can probably deal with it better. I think of it as taking one for the team. Less than a week in, part of my brain saw it as a privilege — a full circle moment of working on something and then literally walking in the shoes of my patients. I wasn’t angry.

In the first weeks, I’d lose control and sob uncontrollably, mainly thinking about my girls and the possibility of not having a role in their future. Dads are supposed to do certain things with their daughters. The feeling of leaving them vulnerable was hard.

Another thing that made me cry — and took longer to process — was when anyone was being nice to me. I kept the diagnosis close, but people reached out, and it’s hard to deal with others’ anxiety. I’m dealing with my own stuff; I don’t have time for yours. But you also have to accept kindness and love — not just give lip service, but actually absorb it, which is surprisingly hard.

Less than a week in, part of my brain saw it as a privilege — a full circle moment of working on something and then literally walking in the shoes of my patients. I wasn’t angry.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Seeing Life Differently

Family Vacation

We had a vacation in the Florida Keys booked a week after my diagnosis, which was perfect timing. I had started targeted therapy, so we could go. Every moment and photograph feels different now because you have the concept that someone will look back on them and you won’t be there.

My wife was taking a picture of me and the girls in their bathing suits, giggling as I smiled and pointed skyward. It could mean, “This is my number one daughter, and this is my number one daughter, too.” Or maybe, if I’m not here, I’m pointing upwards so they know that Daddy’s looking down. Maybe that’s cheesy, but that’s what I felt.

Every moment and photograph feels different now because you have the concept that someone will look back on them and you won’t be there.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

The Girls’ Experience and Second-Line Treatment

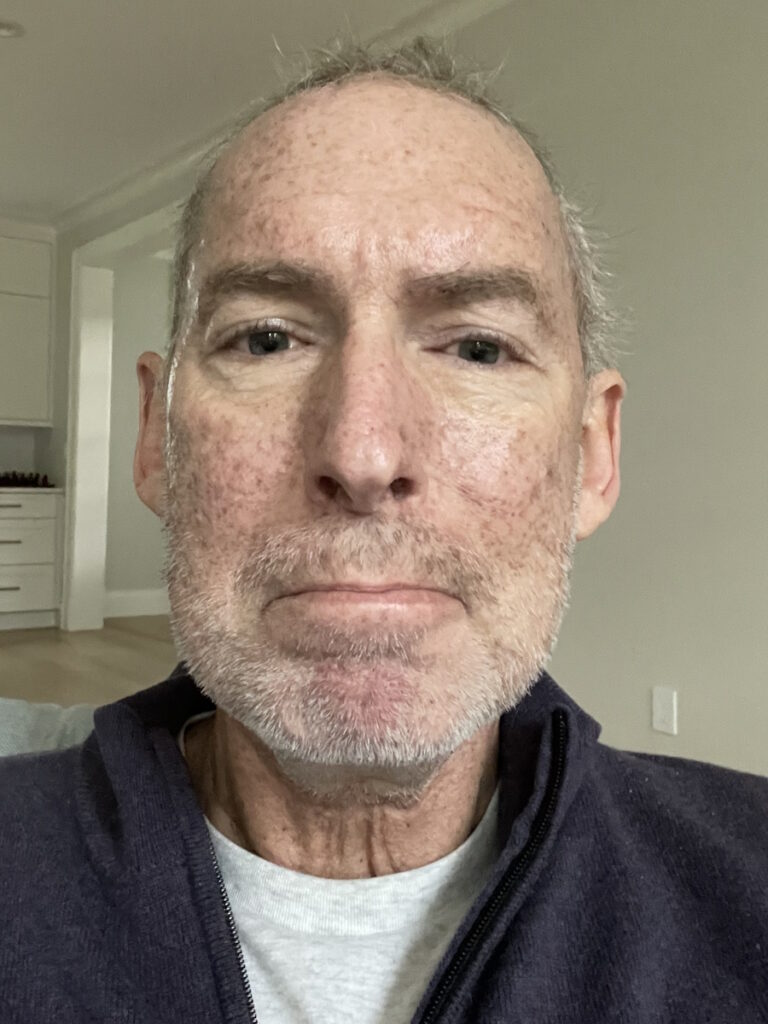

The girls coped well. We didn’t burden them with every scan and bump. I’m a believer in minimizing cancer cell diversity — evolution needs diversity, so you want to minimize the palette. Even though the pill worked, I consolidated with chemotherapy, then radiation to all known disease sites, similar to what I would do for my own patients. Fatigue made me sleep more. The girls were fine and got used to finding me asleep on the sofa.

About 2 1/2 years in, an area progressed. I described oligoprogression as everything is controlled and when a weed comes up, you don’t panic, you just treat it. I had radiotherapy and thought to try another chemotherapy course for any microscopic disease, considering a new drug from a friend in the pharmaceutical industry. I discussed it with my oncologist, who was also a former trainee, and we tried adding this drug.

While some tolerate it fine, I had a terrible time. I had rash, scabs, couldn’t eat, lost 10-15% body weight, and threw up a lot. The side effects exaggerated those of chemotherapy, so I moved into the basement so the girls didn’t have to see me run to the bathroom as often. The oldest struggled, found it upsetting, and was polite but somewhat distanced. The youngest would sit on the end of the bed and tell me about her day, which was incredibly valuable — acting normal, showing I was still present.

I’ve recovered now. My hair has returned, I regained the weight — maybe too much — and I’m back to my routine of living 90 days at a time, which was the time between scans.

The youngest would sit on the end of the bed and tell me about her day, which was incredibly valuable — acting normal, showing I was still present.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Maintaining Privacy During Treatment

For the first 2 1/2 years, privacy was easy. I only told my family, some close friends, and my medical team. I run the program. The surgeons didn’t need to know, but the radiation oncologists and pathologists knew.

When I told the team, I was a mess, but ended with three bullet points: treat me the same — if you were horrible, keep being horrible; keep the circle of trust — patients don’t need to panic; look after yourselves — it’s a shock for you, too. That worked until I had the bad reaction to the treatment, so I skipped conferences and kept the Zoom camera off as I felt so bad, like death with vomiting and constipation. I didn’t want my life to end this way or any public declaration to bring value. When I felt better in September 2025, three years after the diagnosis, I came out of the cancer closet.

I checked with the girls at a family meeting for their awareness. Beforehand, the counselor wasn’t sure the youngest had internalized what my diagnosis meant because she was 10 at the time. The counselor wanted black-and-white: Daddy is going to die from his lung cancer. During our family meeting, I used that line and everyone cried. Then, as teenagers do, they said, “What’s for dinner now?” Normality resumed, at least outwardly.

When I told the team, I was a mess, but ended with three bullet points: treat me the same… keep the circle of trust… look after yourselves.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

Sharing My Story: My Why

Coming out after three years had value. I could say, “You’ve interacted with me for three years, and there was value in that — you’ve been interacting with a cancer patient. Surprise!” I want to stand up and show that cancer doesn’t mean the end of value or end of productive life.

At conferences, I don’t need to be introduced as a patient — I just happen to be one. The goal is to let cancer become as much as a footnote in a speaker’s resume as diabetes — irrelevant unless germane.

I want to stand up and show that cancer doesn’t mean the end of value or end of productive life

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

What Patient Advocacy Means: Perspective Shift

People want this Hollywood story: a terrible physician becomes nice because of cancer. I don’t think I was ever that bad. One ongoing mission is how we report side effects — grading is imprecise, missing duration. I tracked my own activities, like email replies during chemotherapy. They dropped to zero for two or three days after treatment and then returned, a visual representation of real impact for others. That’s how I see the value — showing actual patient function, not theoretical toxicity.

I benefited from my own work — how we surveil people in therapy, watch the brain, and consolidate with radiation. I was even involved in the initial trials for the drug that I’m on. I also benefited from research by my colleagues and patients who came before.

Living With Uncertainty

I’m comfortable living with the unknowns. I know the worst-case and best-case scenarios, and having seen and lived those examples, I’m okay with uncertainty.

When people say, “You’re no evidence of disease, right?” it’s not that simple. I have things going on. I’m not cured, but I’m not actively dying. It’s a middle ground — an uneasy relationship with cancer, like a slightly annoying neighbor. Sometimes it’s quiet, sometimes it knocks on the wall, but you deal with it.

I know the worst-case and best-case scenarios, and having seen and lived those examples, I’m okay with uncertainty.

Dr. Ross Camidge, Lung Cancer Expert

How I Live Life Differently Now

Now, I turn down things I don’t want to do. I no longer feel I must be a good citizen and join boring committees. I carve out time to try new things with the 90-day challenge by trying something new between scans. Yesterday, I did my first knitting class. I was terrible at it, but it was a new experience. Mentoring, encouraging, sharing mistakes and successes, that’s my legacy; I’m passionate about that.

Messages for My Daughters on Their Birthdays

You’re conflicted. You want things to be normal — kids ignoring you, rolling their eyes — but also want them to understand your situation. There’s a delight in not forcing yourself into their lives. The more they behave like typical teenagers, the better.

Inspired by Dr. Camidge's story?

Share your story, too!

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

More Metastatic Lung Cancer Stories

Stephanie K., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Persistent and intense cough, general feeling of sluggishness

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy through a clinical trial, radiation therapy

...

Jennifer M., Lung Cancer, EGFR+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: None per se; discovered during physical checkup for what seemed to be a sinus infection

Treatments: Radiation therapy (stereotactic body radiation therapy or SBRT), targeted therapy

...

Laura R., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Persistent cough, fatigue, bone pain

Treatments: Targeted therapies (tyrosine kinase inhibitors or TKIs, including through a clinical trial)

...

Ashley C., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, HER2+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Fatigue, breathlessness, persistent back pain, multiple rounds of bronchitis

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy

...

Loryn F., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, HER2+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Extreme fatigue, persistent back pain, chest pain, joint pain in the feet, hips, legs, shoulders, and elbows

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation therapy (foot and elbow to help with mobility), antibody-drug conjugate

...

Clara C., Lung Cancer, MSH6, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Pelvic pain, joint and bone pain, breast lump, extreme lightheadedness and dizziness, vomiting, fainting spells, swollen lymph node in the neck, neuropathy, headaches, unexplained weight loss, severe anemia

Treatments: Radiation therapy to the brain, chemotherapy, immunotherapy

...