Optimizing Quality of Life

Reducing Toxicity in Hodgkin Lymphoma Care

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

Relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s thriver Sam Siegel and Dr. Andy Evens from Rutgers Cancer Institute discuss the latest in Hodgkin’s lymphoma treatments and how to reduce the toxicity of treatments so patients can live their best lives after cancer.

Get updates on recent and upcoming clinical trials, how to manage treatment side effects, and new approaches to mitigate chemo toxicity.

Know more about the role of stem cell transplant and radiation in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma, and how to create personalized Hodgkin treatment plans.

Learn what questions to discuss with your care team, lifestyle changes to improve quality of life, and how to have a holistic approach to your care.

This program is brought to you by The Patient Story in partnership with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and Imerman Angels.

- Introduction

- Sam’s Hodgkin Lymphoma Story

- Cancer Survivorship

- Advances in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Treatments

- Decreasing the Toxicity of Therapy

- Late-Term Side Effects of Treatment

- Clinical Trials in Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Understanding Clinical Trials

- Role of Stem Cell Transplant in the Treatment of Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Continued Monitoring

- Final Takeaways

Introduction

Sam Siegel, MD, Patient Advocate

Dr. Sam Siegel: I’m a relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s thriver, mom of three, loving wife, primary care provider, and survivorship medicine practitioner. I’m here to talk about Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the latest treatments focusing on reduced side effects, and a holistic approach to care.

We want to note that The Patient Story retains full editorial control of this entire program and that this is not meant to be a substitute for medical advice.

We’re so proud to be partnering with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and Imerman Angels for this program.

I’m excited for this conversation with Dr. Andrew Evens from Rutgers Cancer Institute to talk about the latest trials in Hodgkin’s lymphoma and how to reduce the toxicity of treatments so that we can live our best lives after surviving cancer.

Andrew Evens, DO, MBA, MSc

Sam: I have the privilege of being with Dr. Andrew Evens, a specialist in Hodgkin’s lymphoma at Rutgers, leading clinical trials for more than 20 years, and also the medical director of RWJBarnabas Health.

Dr. Evens, can you tell us more about your path into Hodgkin’s lymphoma treatments and all of the amazing things that you do for the lymphoma community?

Dr. Andy Evens: I completed my fellowship at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chicago. When I was going through my fellowship, I was fortunate to be exposed to some incredible lymphoma mentors, non-Hodgkin’s and Hodgkin’s.

Dr. Leo Gordon, who was and is still the director of the lymphoma program, Dr. Jane Winter, one of our recent American Society of Hematology (ASH) presidents, Dr. Martin Tallman, and Dr. Steve Rosen—stalwarts in the field of hematologic malignancies.

I had an early interest. This was over 20 years ago and at the time, we knew that Hodgkin lymphoma was pretty curable. We’ve known that since the 1980s, but nothing’s 100%.

Sometimes, it doesn’t always work or there are side effects. Even though we have known for a few decades that it’s very treatable and curable, we’re always trying to do better and do so with more tolerable targeted treatments. It’s an active area of study.

I was finishing my training with a global network of Hodgkin lymphoma experts. There are many different meetings and conferences we all go to. There’s one in particular in Cologne, Germany, that they’ve had for over 20 years. They’ve been amongst the world’s leaders in Hodgkin lymphoma research, clinical research, and basic science research.

At the time, Hodgkin lymphoma experts across the world met there every three years. Now, it’s every two years. When I say all of the experts, it’s not just clinicians. It’s soup to nuts Hodgkin lymphoma. It’s epidemiology. What causes it? It’s etiology. What’s in the microbiology and genomics? It’s diagnosis, treatment, and, importantly, post-treatment survivorship. It’s an incredible meeting.

When I went to that first meeting as a young whippersnapper hematology-oncology fellow, I knew that was for me. Something called to me about it. Knowing that so many different aspects related to Hodgkin lymphoma, I’ve been fortunate to be involved in the field for over 20 years now.

Sam: I did a lot of hematology-oncology in my internal medicine residency. I started as a hospitalist where I did a lot of hematology-oncology and had that lens with end-stage pathology where people come into the hospital very sick and then to outpatient medicine, seeing people sooner and trying to get them diagnosed sooner. Then I got cancer.

Sam’s Hodgkin Lymphoma Story

Sam: My story began in 2021 when I began feeling super exhausted. I thought I was just tired like every other doctor-parent was during the pandemic. A lot of people I knew were tired. I had a lot of justifications for why I was feeling that way.

I started coughing, but there were some wildfires in California so I thought maybe that was it. Maybe I was getting asthma.

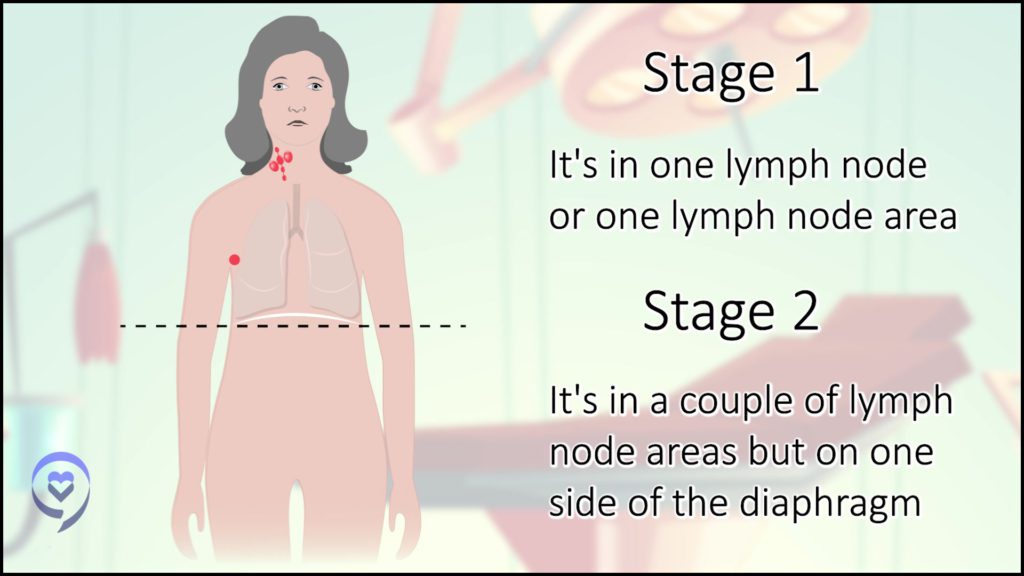

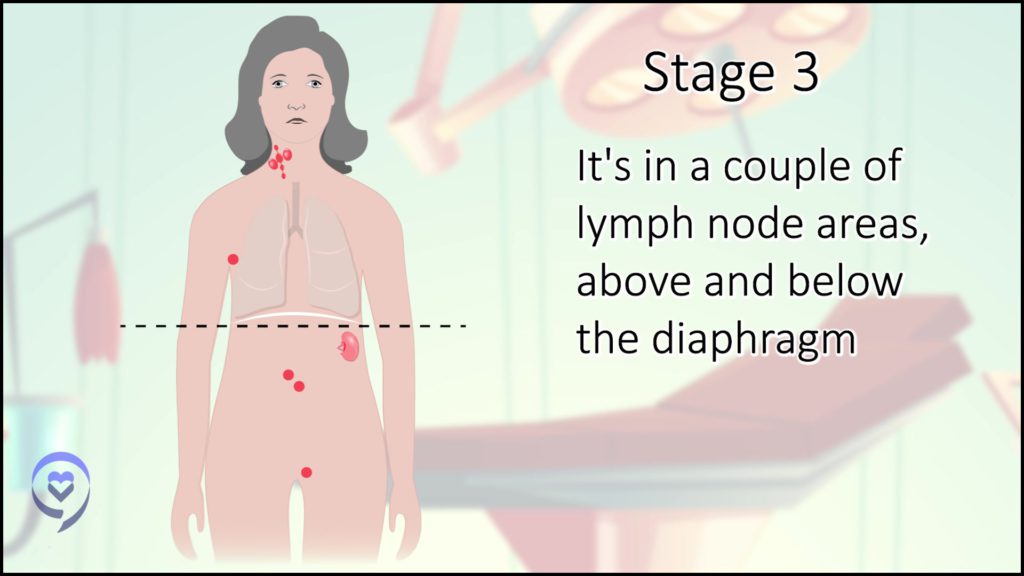

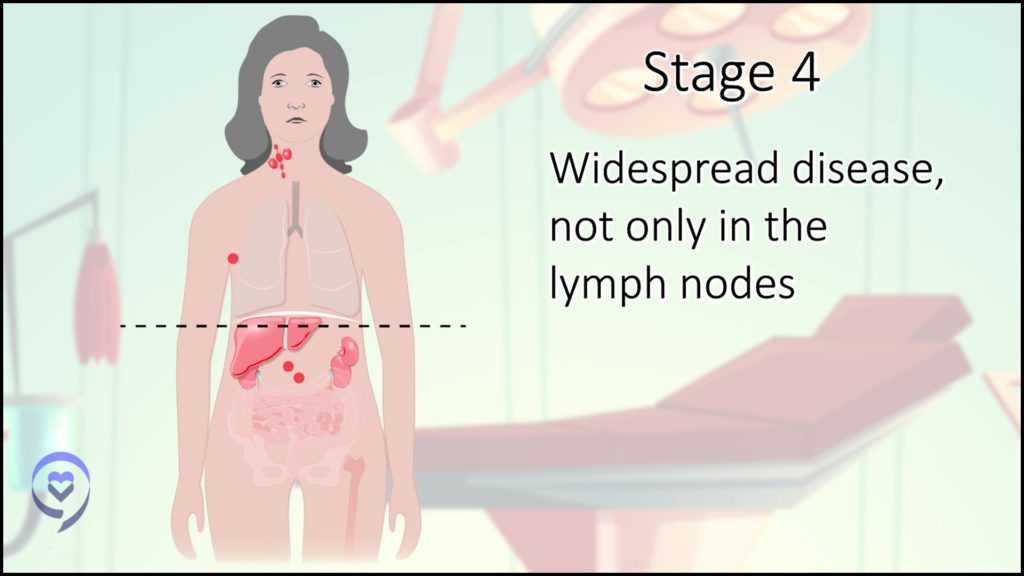

When I developed a rapidly growing, rock-solid, painless lump above my collarbone, I thought, Oh, gosh. I have cancer. Once that showed up, I was no longer in denial and got a whole series of tests that ultimately led to a diagnosis of stage 2AE Hodgkin’s.

In the beginning, there was some controversy about my staging. I had some lung involvement and my understanding at the time was if there’s lung involvement but it’s connected to the major tumors that are there, it’s still stage 2 with extranodal (outside of the lymph nodes) manifestations versus stage 4. That was the first decision-making point. What’s my stage and how would that impact my treatment?

It was a complete shock. I was a marathon-running doctor mom, minding my own business, doing life, and then boom—Hodgkin’s diagnosis. I believed myself to be healthy, even though I was feeling symptomatic.

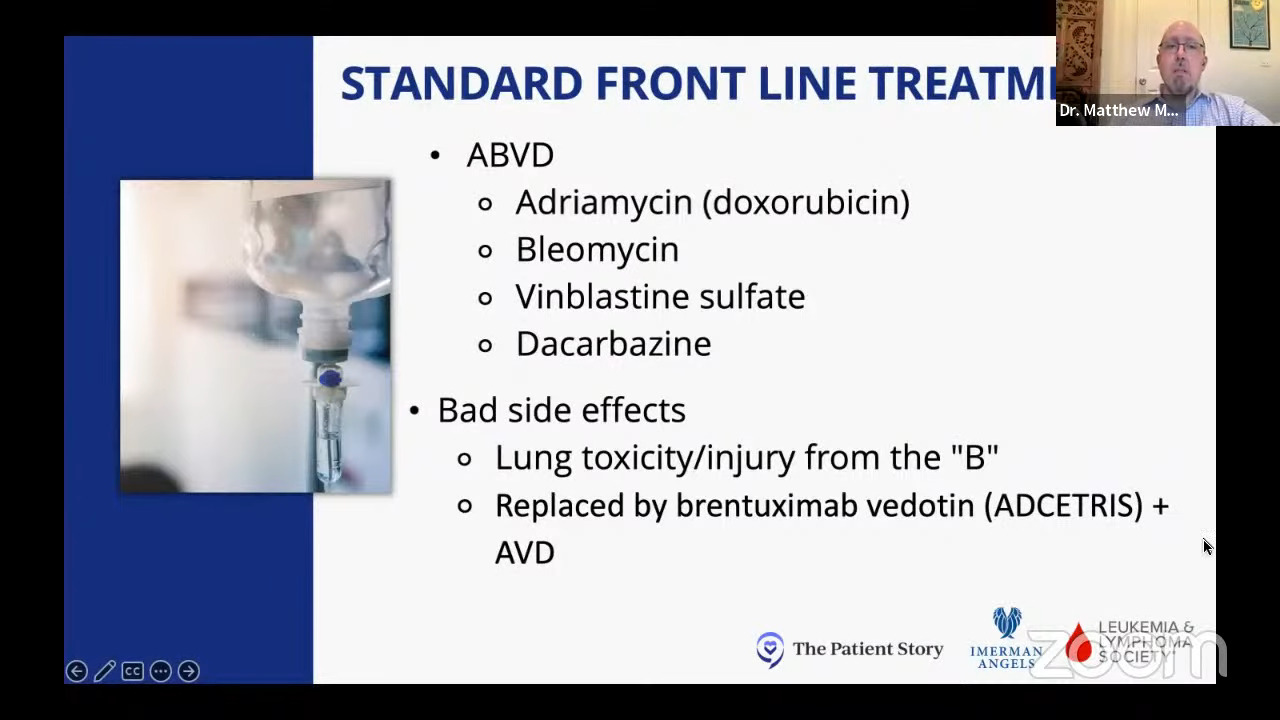

I started what was considered back then the standard upfront treatment called ABVD chemotherapy. My cough went away with my initial chemotherapy and after about two months, the cough came back.

Around that time, I had a scan that showed that my disease was responding well so we decided to drop the bleomycin. We thought I was developing a bleomycin-related cough after the initial cough had gone away.

I continued the next four months with AVD. I got a scan at the end of six months and had no evidence of disease. That was very exciting but also troubling because I felt bad and I wasn’t sure why. Do I feel bad because this is how a body feels after having a multiple-drug regimen for six months or is there something else going on?

I had another PET scan after developing symptoms of relapse and that showed that I had most likely developed a relapse. I had to undergo various procedures to get a tissue sample to confirm. Within a month, I was diagnosed.

What started as a seemingly “simple cancer” or “winning the cancer lottery” as some people are told, I realized very quickly that the treatments are hard, especially some of the older treatments before you get to the immunotherapy and the newer discoveries. Even if you get cured or have no evidence of disease, it can come at a great cost.

Cancer Survivorship

Sam: I found my way to the field of cancer survivorship and I’m super pumped about that and to talk to you about holistic health and your role at RWJBarnabas Health. Because I’m also doing an integrative medicine fellowship, I realized how incomplete our medicine is.

Allopathic Western medicine saved my life, but it also decimated my health at various points so I realized we need other tools. We need to embrace this other field of medicine to complement that, to help people withstand the toxicity of treatment, and to recover and rehabilitate from it when they’re done. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Dr. Evens: There are so many good clinical trials happening across the world. Every clinical trial asks a slightly different question. At the end of the day, however good clinical that trial is, how is that applied at the bedside?

Sometimes, for better or for worse, treatment ideations and recommendations end up becoming one size fits all and we know every patient is different. I always say that there are a lot of commonalities between Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but each patient is unique and different.

How do we take large amounts of data, amalgamate it, and apply it to the patient? It’s difficult because we have lots of data and there are recommendations and certain guidelines.

But what about you, Dr. Sam? For an individual patient with your stage, your albumin, and your lymphocyte count, there might not be one best therapy. There might be treatment options A, B, or C. But are there data or algorithms that I can put my characteristics, desires, hopes, and patient preferences to say if I go with A, B, or C, here’s what I would expect in acute within 1 or 2 years, and here’s what I would expect moreover 30 years down the road?

We’re excited to set up a consortium by the acronym HoLISTIC: Hodgkin Lymphoma International Study for Individual Care. It’s one that we’ve been fortunate to get truly global participation and collaboration.

Advances in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Treatments

Sam’s Hodgkin Lymphoma Relapse

Sam: My mindset shifted. In the beginning, I was so afraid. I’m a young mom with my whole life ahead of me. I was so afraid of dying so I thought, Let’s hit it hard. Let’s do everything. Let’s get the strongest therapy.

As I began to move through treatment and experience, there were some pretty devastating adverse effects that I wasn’t sure how long they would last. As a doctor, I was primarily concerned with the cognitive impairment. I experienced severe chemo-related cognitive impairment, which is the worst form of chemo brain.

I gained 40 lbs from steroids and became severely metabolically ill. I got the rash that people get when they are going to develop diabetes called acanthosis nigricans. My glucose was high and my cravings changed. I wasn’t sure that life as I knew it would ever return.

When I developed symptoms of a relapse, my mindset was different, even just one month later. Let’s not give it everything we’ve got. Let’s make some decisions about how I can take the least amount of therapy to get me into remission and then to transplant.

New Targeted Therapies

Sam: Right around that time, science had shown that people were doing single-agent brentuximab as a bridge to transplant. If that didn’t work, then you could get ICE or some of the other stronger therapies. But there was science to support that single-agent brentuximab was a reasonable thing to do and had lesser toxicity than some of the old bridge therapies.

I was so grateful because I could not psychologically, mentally, and physically handle the more traditional, cytotoxic chemotherapies that I had upfront and that were previously used as part of salvage regimens.

I took brentuximab, initially at the exact dosing used in the trials. Then I developed a strange, rheumatoid arthritis-type illness—bad morning stiffness, joint swelling, pains, and these crazy rashes. Those got better with dose reduction.

Individualizing Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Treatments for Patients

Sam: We’re starting to talk about individualizing therapy for the person, for their circumstances, for their medical comorbid conditions, and to make decisions that way.

Dr. Evens: It sounds like you had a tough time and that’s where everyone is so different. Some patients do relatively well with chemotherapy. Then there are weird side effects that pop up. You went through that roller coaster and were able to course-correct where needed with the dosing.

There have been two big therapeutic breakthroughs in the last 10 years for Hodgkin lymphoma in particular.

We figured out over 20 years ago that one of the antigens that sticks out of a Hodgkin lymphoma cell is called CD30. Brentuximab vedotin, which was first approved in 2018, is an antibody-drug conjugate that attaches to the Hodgkin lymphoma cell, has a little bit of chemotherapy attached to it, and then gets inside the Hodgkin lymphoma cell.

Immunotherapy

Dr. Evens: After that came checkpoint inhibitors or immunotherapy that aren’t just approved for Hodgkin lymphoma, but also for more than 12 different cancers, like melanoma, lung cancer, and renal cancer.

It’s a fascinating science and, in a way, it’s the antithesis to chemotherapy. How does chemotherapy work? It kills cells that grow fast. Not very specific in the body. You hope it knocks out lymphoma cells, but the side effect is it affects anything that grows fast. What are some of our fastest-growing cells? The hair and the immune system. Though chemotherapy is not so targeted, we still use it.

Current and future medicine is more about targeted therapy. How do checkpoint inhibitors work? It reinvigorates the patient’s immune system, the T cells in particular. Simplistically, there are some cancers like Hodgkin lymphoma that have receptors that don’t allow the patient’s immune system to engage with the Hodgkin lymphoma cell. It’s almost like creating a force field.

What these inhibitors do is take down the force field and let the patient’s immune system go after and take down the lymphoma. We’ve learned how to use these medications when the disease relapses, but also for newly diagnosed patients as well through clinical trials.

Sam: I’m so excited because within the last 5 to 10 years, things have changed so much. If I was diagnosed with the same clinical situation as I was back in 2021, my treatment now might be different. That’s pretty crazy to think about because, for so many decades, it was the same: ABVD and possibly radiation.

Decreasing the Toxicity of Therapy

Role of Radiation in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Treatments

Sam: Where does radiation fit in all this? I haven’t even heard much about radiation lately.

Dr. Evens: It still fits for early-stage or limited-stage disease. Yours was a tricky one. We still have to figure out the stage Es. If it’s disseminated extranodal involvement, it’s stage 4. If it’s a lymph node extending towards the lung, that’s more extranodal, but there can be some grey zones. It can be tricky.

Radiation still has a role in limited-stage disease, especially stage 1. For stage 2, the question there is: do I give less chemotherapy and low-dose radiation or more chemotherapy? There’s absolutely no right answer. There’s more disease control. It’s more effective to receive radiation. We always debate the trade-off. What about some of those late consequences? Can radiation contribute to that?

Late-Term Side Effects of Treatment

Sam: Can you mention some of those?

Dr. Evens: It partly depends on the treatment, whether chemotherapy or radiation.

One is arterial disease. Now it depends on location. Radiation techniques have gotten much better over the years. If there’s any scatter of radiation, there could be some carotid involvement or if there’s radiation in the chest area, there’s cardiac involvement. It’s not like there’s an incredible risk. The risk of arterial disease is a little bit increased.

That’s not to say there aren’t risks from chemotherapy, by the way. When we look at chemotherapy alone, there is an increased risk of myocardial infarction later in life because adriamycin can irritate the heart not just acutely but later in life. It rarely happens but it still does.

Another secondary or late consequence we think about, unfortunately, can be second cancers. It’s hard enough to have one, but sometimes, 10, 20, or 30 years later, there can be secondary breast or thyroid cancer. Those are more serious late effects.

Other still serious but maybe not life-threatening late side effects could be hypothyroidism, fatigue, or neuropathy.

At the end of the day, clinical trials are important as they’ve been able to show how to get these novel agents approved and how to bring them to the front line, but we also need to study those late consequences.

Clinical Trials in Hodgkin Lymphoma

Targeted Therapy

Sam: Can you mention clinical trials concerning targeted therapy and immunotherapy?

Dr. Evens: Many of the ones that garnered its approval for relapse don’t have an acronym or a name because they’re often phase 2 trials. We think treatments need phase 3 studies to garner approval. But in uncommon diseases like Hodgkin’s, which affects about 8,000 patients a year in the United States versus 90,000 with non-Hodgkin’s, it’s hard to have randomized data. With a rigorous, large phase 2 study, it can garner approval.

Thankfully, there have been a couple of phase 3 studies. One of them that garnered the approval of brentuximab vedotin in the maintenance after a transplant was called AETHERA. It was a phase 3 blinded randomized study.

The standard of care for relapsed Hodgkin’s is usually some form of therapy, whether chemotherapy or brentuximab, then a transplant. AETHERA added one time a month for a year of maintenance therapy and showed a pretty significant benefit that garnered that approval. But why do we have to wait for a relapse? What if we do it in the beginning?

An important global study called ECHELON-1 was published and has been republished a couple of times in the New England Journal of Medicine. It showed replacing bleomycin with brentuximab vedotin (BV-AVD) compared to ABVD.

The real landmark breakthrough in that study was not just showing progression-free survival, but an overall survival benefit, which we had never seen in the field. You want an overall survival benefit and some of the updated analyses of ECHELON-1 showed that, so that’s great but we’re not done yet.

BV-AVD might be the new king of the hill. How can we knock you off? The most recent phase 3 randomized trial was conducted in the US by our cooperative groups. It was called SWOG S1826. All the groups, including the pediatric oncology group, participated in this study. That’s another important point. We’re working with our pediatric colleagues to go after Hodgkin lymphoma.

That study compared nivolumab, one of the checkpoint inhibitors, and AVD (N-AVD) to brentuximab vedotin and AVD (BV-AVD). It hasn’t been published yet. It’s been presented a couple of times. Long story short, at least at one year, checkpoint chemotherapy looked to have a higher progression-free survival than BV-AVD.

As we go through these studies, we’re trying to not only get better but also get better and have fewer side effects.

Progression-Free Survival vs. Overall Survival

Sam: Could you explain the difference between progression-free survival and overall survival and why that’s exciting?

Dr. Evens: Progression-free survival means the length of life might not be different, but I’m progression-free or in remission longer.

When we first looked at ECHELON-1, we saw that progression-free survival was improved by about 10%. Another way to say that is, for example, for patients treated with BV-AVD, at three years, around 80% of patients were still in remission versus 70%, or maybe it was 85 and 75. That’s good. I’d rather be in remission longer, but I’d also like to live longer. That’s overall survival.

Before ECHELON-1, there had never been a study showing better, longer overall survival compared with classic ABVD. Part of the reason is that if you have a good second therapy, even though there can be side effects, it’s easier to modulate overall survival.

What they showed when they looked at six years for BV-AVD was overall survival improvements. That’s a game-changer in the field. It was already FDA-approved based on progression-free survival, but I think it became more common in use after the overall survival data.

Sam: These are exciting times. I hope to never need the services of a hematologist ever again, but I do have hope that should I experience another relapse, heaven forbid, there are good treatments out there to provide remission and quality of life.

Pembrolizumab

Sam: Tell us about pembrolizumab.

Dr. Evens: Pembrolizumab is another checkpoint inhibitor. Nivolumab and pembrolizumab are much more similar than different. A lot of their studies are keynote studies from that company and it has a number. In particular, Hodgkin’s was KEYNOTE-087. They keep adding numbers throughout all the different cancers. That was initially approved as nivolumab for relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma. That garnered that approval, one of the keynote studies, like nivolumab.

SWOG S1826 was for advanced-stage disease, so stages 3 and 4. When something gets approved for a certain situation, a certain stage, and for certain ages, what about for limited stage or early stage?

For many patients, a common treatment modality for early stage is six months of chemotherapy. Others might receive four cycles of chemotherapy and radiation. We were planning this study for the United States through the US cooperative groups. This study involves the pediatric oncology and adult groups. The Children’s Oncology Group is leading it, but we’re all working together.

There is a new national, high-priority study called AHOD2131. It’s comparing the standard of care that we talked about for early-stage disease versus everybody on the new arms of two cycles of chemo and the rest, targeted therapy: a combination of brentuximab vedotin and a checkpoint inhibitor.

The hypothesis is it’ll be more effective and likely better tolerated. That’s an ongoing study. It opened in the summer of 2023 and is planning to enroll over the next couple of years.

What’s great about that study is not that it incorporates novel therapeutic agents in place of cytotoxic chemotherapy, but over 10 to 12 years, it’s going to study some of the late-term effects and that’s sometimes a gap with clinical trials.

They’re great in the first couple of years then they fall off and don’t have the resources or funding to study late-term effects. In great collaboration with the National Cancer Institute and CTEP (Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program), they are providing resources not just to study the initial 3, 4, or 5 years, but extend beyond 10 years, which is fantastic.

Understanding Clinical Trials

Sam: You brought up some great points and I want to highlight this for patients because I don’t even think I felt empowered to think these things or ask some of these questions with the initial shock of the diagnosis.

Clinical trials are not just for people who have failed multiple lines of therapy. Clinical trials could be for multiple situations. How do we de-intensify therapy? How do we make different therapeutic decisions? How do we start using therapies that were used in a very specific situation, like only for relapsed/refractory, and use them for early-stage patients upfront? That’s what some of these trials are showing.

What advice could you give to patients?

Dr. Evens: Be an advocate for yourself or your family member because this is your life. Not to minimize it, but there should be no intimidation or concern of talking to the oncologist.

99.9% of oncologists want the best for their patients. Sometimes, the provider might not always bring up a clinical trial because they might not have access. But I would encourage you to ask if a clinical trial is right for you.

I wish we had a clinical trial for every condition. There’s always a semi-standard of care. We’re always trying to do better or if not do better, do the same with fewer side effects. The only way you can do that is ultimately in a clinical trial.

These are very sophisticated studies where we’re hopeful. Of course, we have to prove it in that clinical trial. The vast majority of clinical trials are with targeted agents or immunotherapy agents. I would implore the patients and patient family members to, if not self-advocate, reach out to other foundations.

The Patient Story is a great information disseminator. Other organizations are the Lymphoma Research Foundation (LRF) and The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS). They have inlets and conduits to look at clinical trials, whether for Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. You can visit ClinicalTrials.gov and type in the condition, and it will list sites across the country where clinical trials are available.

Sam: On that note, if you have any questions regarding how to look up and navigate through clinical trials, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society has a clinical trial support center with free access to experts who can guide you through that process.

Dr. Evens: The best outcomes are usually with the most informed patients who know the different options. In Hodgkin lymphoma, very, very often, there’s not one right way to treat it. There are different options. There shouldn’t be anything scary or wrong with getting second opinions. We’re often happy to help.

Sometimes we won’t have anything different to offer or it might not even be a clinical trial, but a little nuance on dosing or something based on patient characteristics or comorbidity. We might want to make a certain adjustment a priori to a treatment. When that’s all you do for 20 years, you’ve seen it all and every condition, and we’re happy to lend any advice we can.

Role of Stem Cell Transplant in the Treatment of Hodgkin Lymphoma

Sam: Where does transplant fit in all of this? I had an autologous stem cell transplant. I’m so grateful for it, but it was tough. I had beam therapy as a conditioning regimen because I had hemorrhagic cystitis from cyclophosphamide when I was mobilizing my stem cells.

Dr. Evens: You had almost every side effect.

Sam: I did and then I had pneumonitis from carmustine. I believe that I had this cancer at this time in my life and had such a tough course so that I could learn about these things, be an advocate, and go into longitudinal survivorship.

I know now some of the questions to ask, some of the things that can happen, and how hard it can be, even when it’s the “good cancer.” I did just like AETHERA—I had one year of post-transplant brentuximab.

Dr. Evens: Did you do okay with it?

Sam: I did. I ended up getting a dose reduction because we learned before I had a transplant that I needed the dose-reduced brentuximab as well. I had some neuropathy, which wasn’t just pain. It was falls, clumsiness, and dropping things.

Dr. Evens: It was affecting your function.

Sam: It was. I do a lot of procedures so for people like me who work with their hands or do a lot of things with their hands or feet, it could be important. The neuropathy is still there, but it’s recovering.

Autologous vs. Allogeneic

Dr. Evens: For over 30 years, transplant has been the standard for Hodgkin lymphoma in younger patients. When we say younger, we mean less than age 70. The patient receives some new treatment, gets back in remission, and then a one-time transplant.

When we say transplant, it’s an autologous transplant, which uses your own cells so it’s not a transplant. It’s one cycle of high-dose chemotherapy followed by a rescue using your own stem cells so you bounce back after the chemotherapy. We do an immune system transplant or allogeneic transplant, but we rarely have to do this for Hodgkin’s.

As much of a standard of care as it’s been, we’re revisiting everything and asking: does everybody need a transplant? Now that we have brentuximab vedotin and checkpoint inhibitors, can we lean on these targeted therapies for certain patients?

There isn’t a study set up. It’s being actively discussed with the National Cancer Institute and many leaders across the country. I’m helping represent the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) as part of this planning.

Studies take months and sometimes a couple of years to plan because you want to get it right and have the latest treatment and data. We’ve been talking about it and planning it to ultimately prove it because it can’t just be an idea. We have to prove it. It would have to be a clinical trial where there’s some randomization to the standard transplant or no transplant.

It’s not done yet, but I’m hopeful that is something we can explore and that we can cure relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma without a transplant. But right now, that’s not the standard of care. It would still be a transplant.

Continued Monitoring

Sam: How are we monitoring patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma?

Dr. Evens: There are different practice styles and part of the reason is it also comes back to data. We don’t want to do a scan just to do a scan. Is it helpful? Does it tell us information?

What had been standard for a while, whether for initially diagnosed or for relapsed, is when there’s a transplant, the vast majority of the time, we count two years from diagnosis.

During that two-year time mark counting from the initial diagnosis or the initial relapse, some of us will usually see patients in the office every three months for a physical exam, history physical, maybe some blood tests, and sometimes a CT scan every six months.

Not everyone does scans. They think there’s lead time bias and it only maybe helps you pick it up a little bit earlier but doesn’t improve survival. But if someone does scans, they should not do it past the two-year mark.

There’s radiation with CT scans. We don’t think of it, but for many types of CT scans, that’s equal in radiation to 500 chest X-rays. Imagine getting 500 chest X-rays. It’s something we want to use if it’s helpful, but not too much.

But what about after two years? What about after five years? Ten years? That’s where I think we need a greater focus and an opportunity on bonafide survivorship clinics.

There are some good algorithms. I know our pediatric oncology group at the Rutgers Cancer Institute has a computer program where they can put in the patient’s age, treatment, and whether they’ve undergone radiation, then based on the best available data, it will generate your primary care follow-up.

None of the recommendations are likely, but they’re usually evidence-based to show that there’s some impact on that. I would say individualized, but it’s something that we need to make sure, as a community, our patients know that the survivorship aspects are still very important.

It’s not just about breast cancer screening, heart screening, etc. What about chronic fatigue? What about anxiety and other emotional disturbances that can happen? In a survivorship clinic, like what we have at the Rutgers Cancer Institute, you have experts like physicians, nurses, and social workers surrounding the patient throughout the life-long care continuum.

Sam: I love that and I love that you made the distinction between surveillance and survivorship because I think surveillance is a big part of survivorship, but it’s not all of survivorship.

My understanding in speaking with people from the NCI Office of Cancer Survivorship is that a hot topic within the survivorship research community right now is what is a mutually agreed upon definition. It includes surveillance. But it’s also cancer-surviving mindsets and how we plan for life after a cancer diagnosis, including oncofertility, social-emotional well-being, family planning, and reintegration in work life, society, or family. How do you live your life after you’ve had a cancer diagnosis, regardless of your remission status or where you’re at and all that, including making sure that you get your scans and your bloodwork and all that?

I think a lot of people in the community are starting to realize that it’s so much more. I’m hoping that, ultimately, it’ll be a board-certified fellowship in the next five years or so with core competencies like this is what a survivorship clinician should know and be able to talk to patients about.

Dr. Evens: Absolutely. We talked a little bit about the HoLISTIC Consortium and that’s one of our goals. Despite the commonality in terms of the number of diagnoses, it’s remarkable that we’ve come together under this consortium and have done so in the last few years and that’s to gather the world’s data of clinical trials.

In many of those clinical trials we talked about, this is individual patient-level data. It’s de-identified, careful individual patient data put into a huge master database with a common data model and data dictionary so they all come in a readable and harmonized fashion.

We’ve also knitted together and synthesized large amounts of clinical trial data. There are survivorship clinics and survivorship cohorts out there across the world collecting data over decades at Princess Margaret in Toronto, BC Cancer Vancouver, Stanford in California, Australia, the Netherlands, and Denmark.

Over the last few years, we have put together 20,000 cases of patients in clinical trials and survivorship registry cohorts to give objective information. If you did A, B, or C, here are your expected efficacy and side effects based on your individual characteristics.

But also to simulate, as best as we can tell, based on this treatment and at this point in your cancer journey, what we estimate to be your 10-, 20-, and 30-year late consequences to make a more personalized survivorship plan and not just an initial treatment plan. The way we’re going to do that is through large amounts of big data and data analytics with some machine learning mixed in.

Sam: That’s exciting because one of my big aha moments with starting to participate in the survivorship community is that survivorship is defined as anybody living after a cancer diagnosis, but it doesn’t seem to be routinely delivered that way. It seems that it’s piecemeal and it’s focused on a couple of cancers.

I believe that longitudinal survivorship is the way. We should deliver survivorship from the time of diagnosis, in parallel with oncology care that’s delivered by the oncologist. If we know we’re going to give a person cardiotoxic chemotherapy, let’s not wait until they develop heart disease 20 years down the road to start paying attention to heart disease risk. We could put people through intensive lifestyle medicine therapies where we talk about diet and exercise, check their A1C and cholesterol levels, monitor their blood pressure, and talk about heart health in the beginning.

Dr. Evens: We have some patient advocates and we’d love for you to become involved to some degree as a patient advocate and a physician expert as part of HoLISTIC. We’re still gathering and building data, but we’re looking forward to starting how we best apply this to patients and the medical community.

Final Takeaways

Sam: This has been just such an exciting conversation. What are some final takeaway messages that you have for patients, providers, and advocates?

Dr. Evens: It starts with an informed provider and informed patients. Is Hodgkin lymphoma treatable and curable? Yes, whether it’s newly diagnosed or stage 4, even if it comes back once or twice, but there are different treatment options.

When it comes to treatment options, how effective are they? How will the patient tolerate it in the moment and later in life? The number one goal is to cure but do so with minimal side effects. It comes back to personalized cancer care.

There has been great progress over the last few decades. We still have room to have treatments that are better tolerated. We’re thankful to have well-informed patients, patient advocates, scientists, clinicians, epidemiologists, and survivorship experts. Everyone is coming together, laser-focused on Hodgkin lymphoma to continue to advance the field.

Sam: I agree. I think that there’s a palpable shift in cancer culture. We need to do more than just focus on not dying. Let’s focus on the living part. How do we help people fully live after facing a cancer diagnosis? This is a really exciting time. I’m grateful to have had this conversation with you and can’t thank you enough for your time.