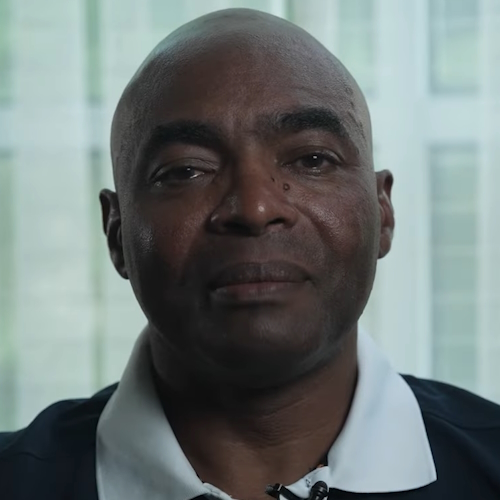

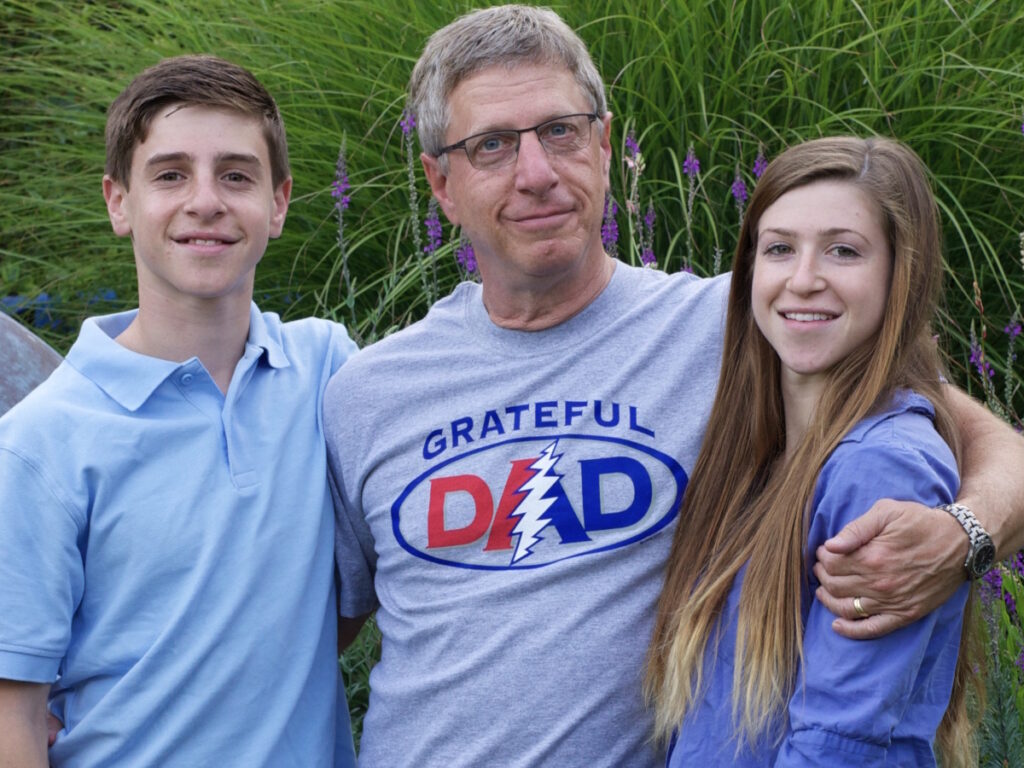

Paul’s Prostate Cancer Story

Interviewed by: Stephanie Chuang

Edited by: Bella Martinez & Katrina Villareal

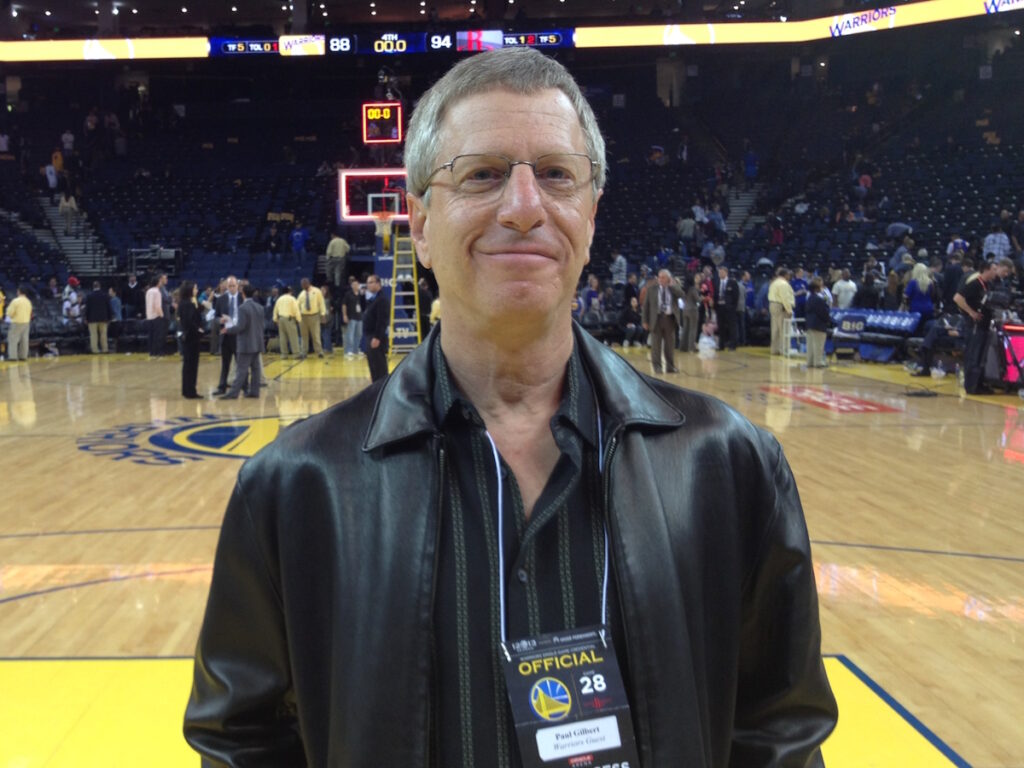

In 2019, Paul received a shocking diagnosis of prostate cancer after a routine check-up uncovered a Gleason score of 4+3. Reeling from the news, he underwent radical prostatectomy surgery.

After connecting with a prostate cancer support group, Paul was able to make sense of treatment options and find emotional support. But two years later, a follow-up PSA test revealed rising levels, indicating his prostate cancer had returned. This relapse encouraged Paul to research integrative medicine techniques and shift his mindset with mindfulness practices as active parts of his healing journey.

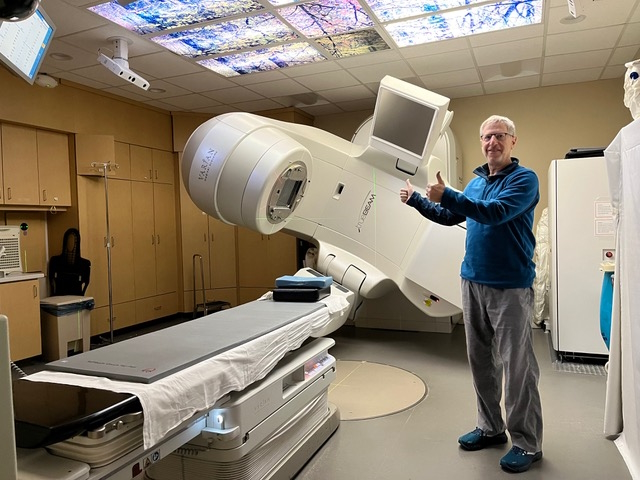

Now in remission following radiation and hormone therapy, Paul took to writing for Medium where he shared his cancer journey and the lessons he learned along the way. He now shares his story with us and discusses how changing his mindset and focusing on positivity has helped him on his healing journey.

Paul’s story is part of the “Our Voices, Our Power” series by The Patient Story. Discover more of the series by exploring Tim’s stage 1 prostate cancer story.

Thank you to Janssen for its support of our patient education program! The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Introduction

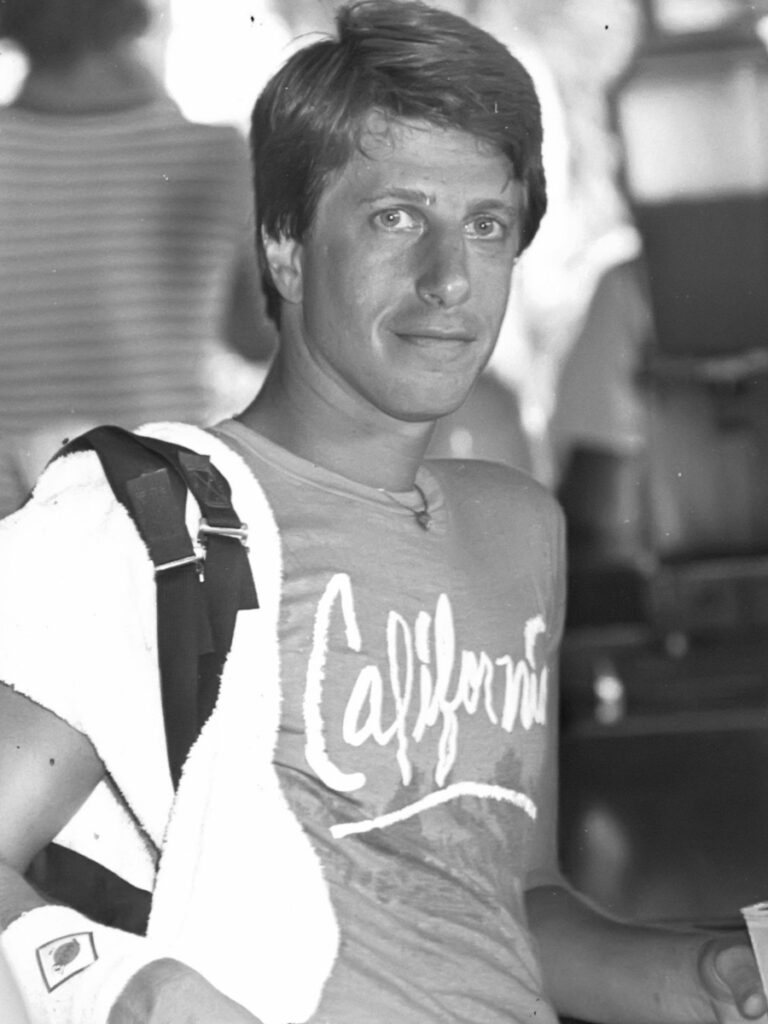

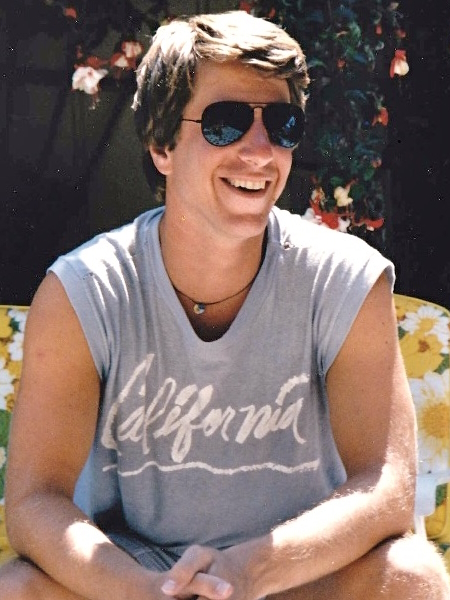

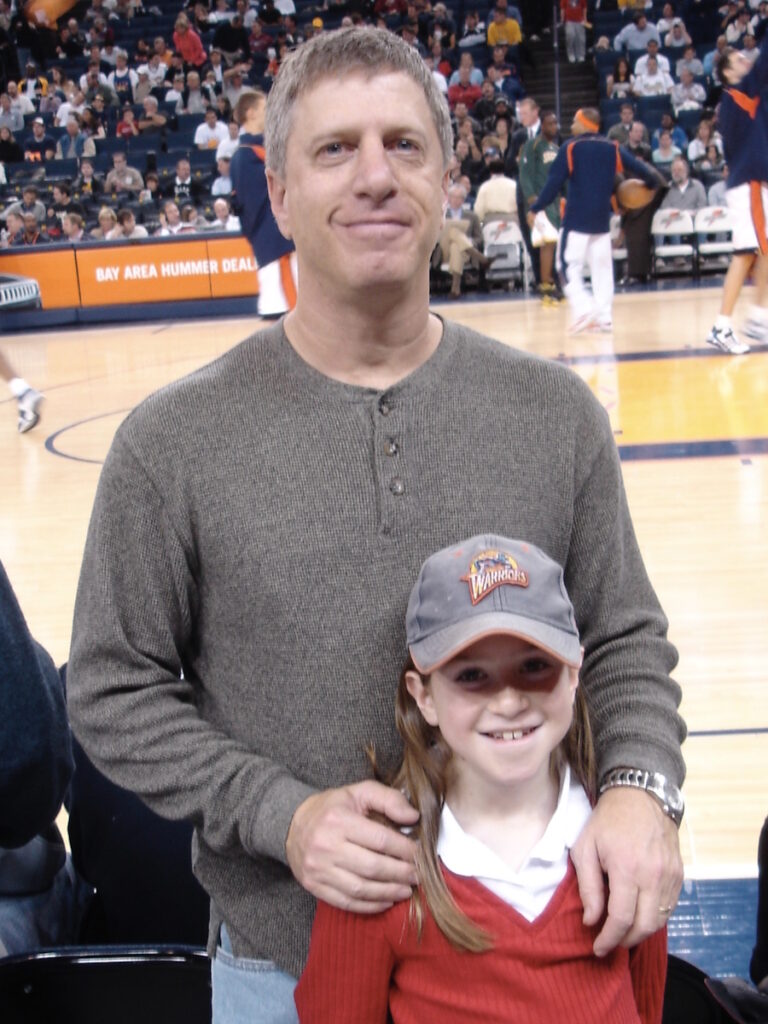

I grew up outside New York City, in suburban New Jersey. I was an athlete and an editor of my school paper.

I decided I wanted to go to college in California, so I went to UC Santa Cruz, 2,000 acres of rolling meadows and redwoods overlooking Monterey Bay. I invented my own major called The Politics of Mass Media. I was a disc jockey and had a sports show on the radio station.

After graduating, I realized there were no media jobs in Santa Cruz, so I went back to New York City to start my career.

I was highly motivated. This was the 70s, so there were plenty of other highs as well. I wanted to explore different things. I knew what I liked. I loved sports and I liked writing.

Being a Storyteller

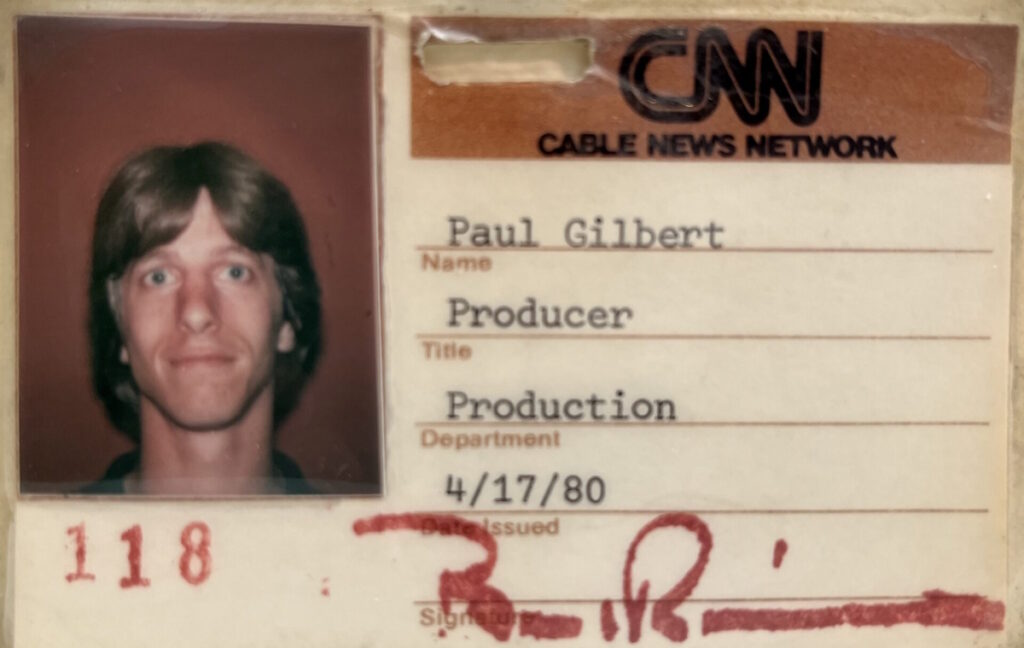

I jumped from the radio to CNN when it was first starting. I went down to Atlanta where it was going to be the first 24/7 station. I was hired as a writer. Within a week, I became a producer and a producer anchor within two weeks. At the time, that was the way CNN was because they didn’t have enough people.

I learned to become a storyteller in the video medium. I ended up doing high-end corporate videos and nonprofit videos, so I had to learn how to tell those stories as well.

After 40-plus years of being in media, I consider myself — and I say this with humility — a master storyteller. I’m still working on my craft.

I was probably telling stories when I was a child, too.

The great gift is not only being loved but giving love.

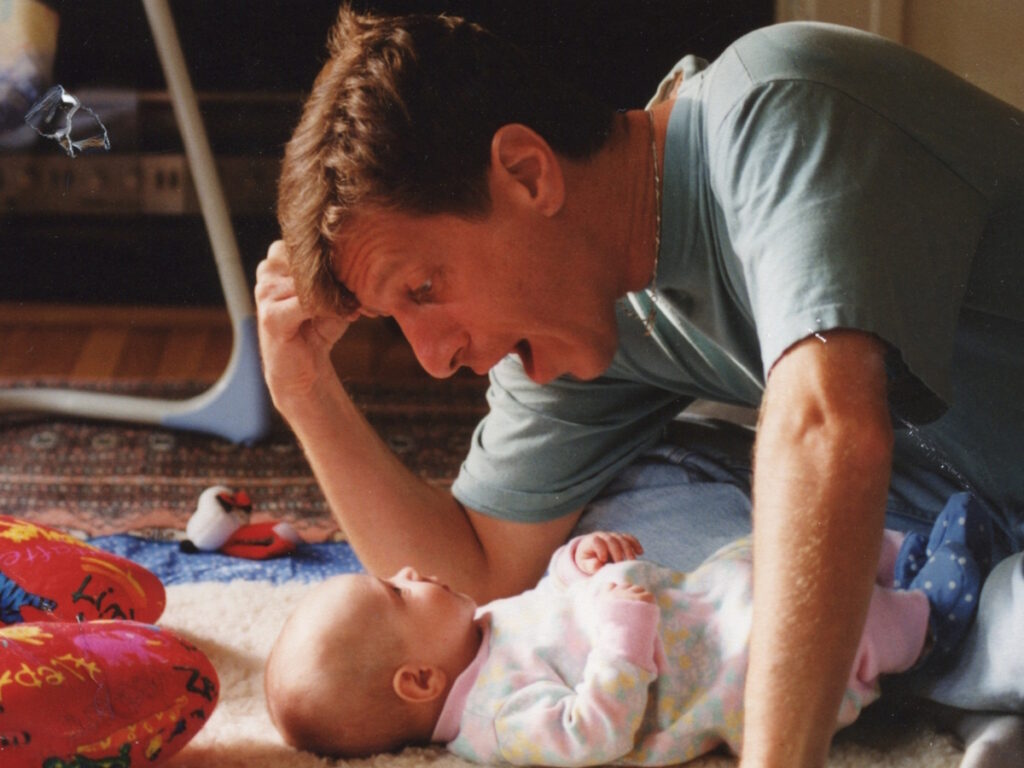

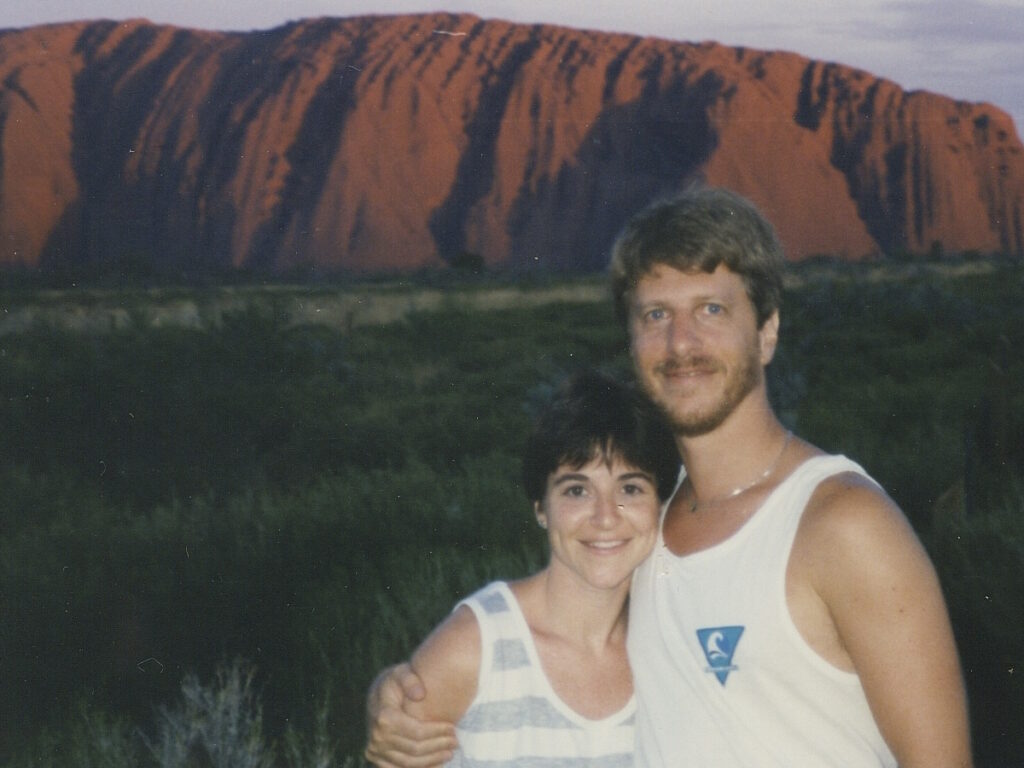

Meeting My Wife

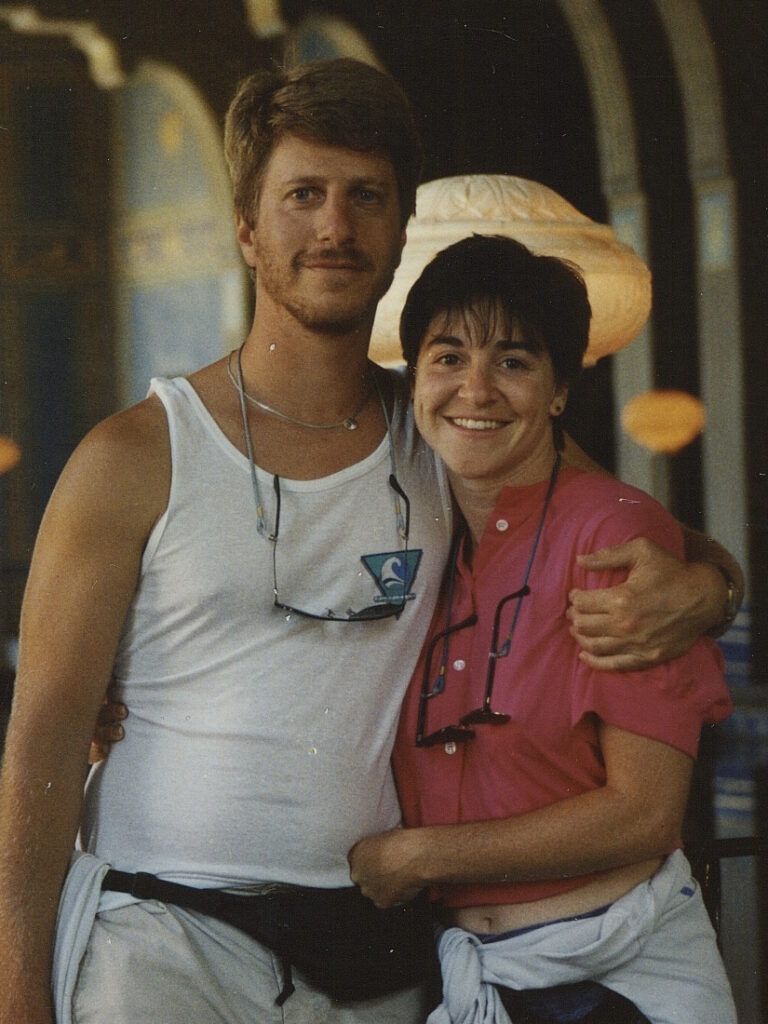

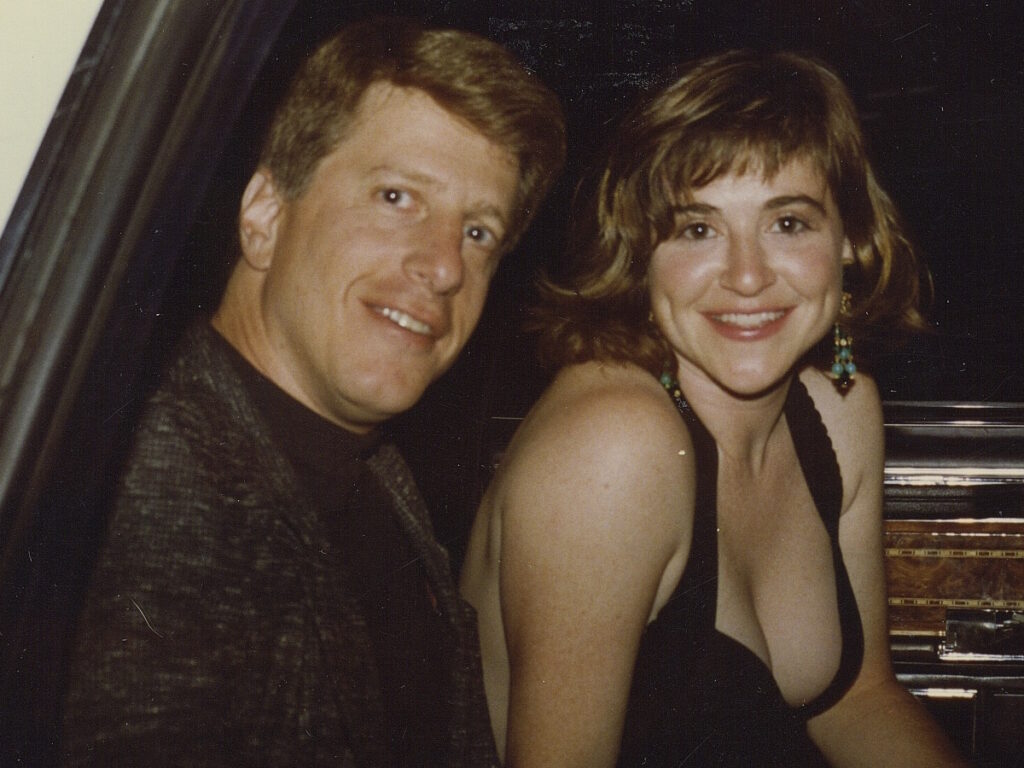

In 1988, I was in Central Park riding my bike approaching Strawberry Fields at 72nd Street. I saw this young woman, Wendi Messing, lacing up her roller skates and when she got up, I sidled up next to her and said, “Are you going to Disco Heaven?” This was a place near the volleyball courts where everybody skated around with giant boom boxes. She’d never been there before. It wasn’t a truth or dare moment, but I pushed her a little bit, so she went up there and skated around having a grand old time.

I was riding my bike around, but I was watching. When she left, I rode behind her and threw out a line. She bit and I reeled her in.

We sat and talked. She was an advertising producer. We were both cutting videos to the song Hot Together by the Pointer Sisters. Talk about serendipity!

We made a date to get together. As the months went on, the other thing we found out was we didn’t want to live in New York anymore. We ended up in San Francisco and started from there.

I had been a serial dater. I was in my mid-30s at that point. They said she was the kind of girl I wanted to marry. She was hard-oriented, sweet, and really cute. We were in the same business. We were both Jewish. A lot of things lined up.

The great gift is not only being loved but also giving love. I think in some ways, we want that even more. I feel that with my dog. As much as they say, “Dogs give unconditional love,” we also give them unconditional love back.

I won’t use the word “caretakers.” We’re givers. I tell Wendi, “I never come home without something for you.” I’m always thinking, What could I bring her? I know she was always looking out for me.

When I was diagnosed with prostate cancer, I realized that I had gone from living a normal life to now all of a sudden, I’m in a club I never wanted to be a member of.

I realized that I had gone from living a normal life to now all of a sudden, I’m in a club I never wanted to be a member of.

Pre-diagnosis

Initial Symptoms

I went to a regular checkup and during the rectal examination, the doctor said he felt something. I didn’t know what to think. I didn’t think it was good, but I didn’t think it was terrible. He sent me to a urologist and said, “I feel something there. Let’s do a biopsy.”

I started to worry a little bit. Biopsies are not fun. They’re very invasive. They go in through your urethra and take samples. I was really sore afterward.

Diagnosis

Getting the Official Diagnosis

About a week later, I was in my car after a workout. I got a phone call from the urologist and he said, “You have prostate cancer.” That’s the minute your life switches.

Reaction to the Diagnosis

I was in shock. I was 63 years old, super healthy, and ate relatively well. I have a sweet tooth, but I didn’t have a lot of high-risk factors. There wasn’t a lot of cancer in my family.

Later on, I found out that two of my uncles had prostate cancer. It was like a kick in the balls, no pun intended. I was stunned. When I told Wendi, I knew immediately that she would be there for me 100%.

I had gone from living a normal life to all of a sudden being in a club I never wanted to be a member of. I’m young, I’m healthy, I eat well, and I exercise. How is this happening? It doesn’t sink in right away. You know that life will never be the same again.

I figured that, for now, I’m going to keep this to myself.

Choosing Who to Share a Cancer Diagnosis With

I’m a very private person. I have a few really good friends that I will tell almost anything, including women, friends, and couples. Unfortunately, both my parents had passed by then. Actually, that was probably fortunate because I know they would have worried so much.

My older brother had frontal temporal dementia and had passed, so it was only my younger brother who knew. I didn’t want to go through it with Wendi’s family. My thing is once you tell everyone, it’s out. You can always decide later on who you want to share it with and how.

I remember reading an article in The New York Times that said the way people react to news about cancer can be very draining for the person who’s sharing the news. They may ask a lot of questions, including a lot that you don’t know the answer to. They may offer advice that you really don’t want to hear.

Everybody knows somebody other than their family or friends who’s had cancer, but if someone’s had breast cancer, leukemia, or lung cancer, it doesn’t relate to prostate cancer. Sometimes people say things that are inappropriate and I didn’t want to go through that.

I figured that, for now, I’m going to keep this to myself because my Gleason score was 4+3. That’s a whole thing in itself. You start learning all these numbers — Gleason scores, quadrants of your prostate capsule, different kinds of reports, and genomic tests. It’s overwhelming.

They couldn’t find anything. That was encouraging… On the other hand, if you don’t know where it is, how are we going to treat it?

What the Numbers Meant

One of the first things I heard was that prostate cancer is a “good cancer.” I would never put those two words together. The reason they call it a good cancer is because it’s very treatable if it’s caught early. Not necessarily cured, but very treatable.

I didn’t feel like I was one of the lucky ones. I got prostate cancer. The word cancer is what you hear. I found that it gets very matter-of-fact with doctors. They’re compassionate, but their job is to tell you the facts and the statistics.

We were getting all these numbers, the Gleason scores, and I was a 4+3. There’s low risk, medium risk, and high risk. I fell right on the cusp of intermediate, but I was on the wrong side of it. 3+4 and below are considered good candidates for active surveillance where you’re watching your PSA levels. That made it a little challenging, too, because I wasn’t high-risk. I was on the cusp. But then they told me the genomic tests showed that it was aggressive, so that put me in another category.

PSMA PET Scan

I had a PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen) PET scan, which is a highly sophisticated PET scan. They shoot you with radioactive isotopes and iodine. They couldn’t find anything. That was encouraging because it meant things were small and they hadn’t moved into my organs or bones. On the other hand, if you don’t know where it is, how are we going to treat it?

I didn’t want to share other than with Wendi. That’s how scared I was.

Breaking the News to the Family

I was somewhat obsessed with thinking about it. It was always in the back of my mind. It’s hard to avoid that when you have cancer.

I told our children a month or two after I found out. I didn’t want to worry them. As I was approaching surgery, I knew that I needed to tell them what was going on.

I also wrote an email to Wendi’s family telling them what was going on. I was going to have surgery, but I was very clear about my boundaries and that I didn’t want to discuss it.

At some point, I would share information as it came up. I might have gone overboard with this, but I was very firm about my boundaries. I know they care and they love me and want to support me, but I didn’t want to go down that road of getting lots of questions and phone calls, so I played it pretty close to the vest.

Processing the Emotions of Having a Cancer Diagnosis

When you hear you have prostate cancer, there’s a lot of fear because it’s a sexually related thing. You’re talking about your internal plumbing and the unknown side effects, which can be incontinence or sexual dysfunction. You don’t want to talk about those things. You also think about dying.

I didn’t want to put that burden of fear on other people. If I couldn’t project overwhelming confidence that I got this, I didn’t want to share it other than with Wendi. That’s how scared I was. I like to be in control as much as possible.

I also grew up in a household where there was a lot of emotional chaos. I’m sure that made me even more of a person who wanted to have control. Suddenly, I was thrust into this situation where I felt like I had no control. I did share it once I knew I was having surgery.

I was tortured during that time by not wanting to make the wrong decision.

Treatment

Treatment Options

I had one of the top surgeons in the country, so I was confident that I was in good hands, but you have to make a decision early on.

Are you going to do radiation or are you going to do surgery? The catch-22 is if you choose radiation, you can’t do surgery later on. If you choose surgery, you can do radiation later on.

I’m in limbo. We can’t find it, I’m on the intermediate to low risk but on the wrong side of it and it’s aggressive.

I wanted more opinions. I didn’t want just a second opinion, I wanted a third opinion. The doctors kept saying, “We think it’s confined to the capsule based on what your Gleason score is and your PSA levels,” but they couldn’t guarantee it.

My initial diagnosis was in January. Over the next months, I was tortured not wanting to make the wrong decision. I had the surgery in April.

Surgery

One of the big concerns of surgery is nerve sparing because there are all these delicate nerves around the prostate. You’re anesthetized and you know that this robot is being controlled by a surgeon. I came out of surgery very groggy. The surgeon said, “I was able to spare your nerves and didn’t see anything outside the capsule.” I felt like that was good, but I was also wounded to the core.

The surgery was a traumatic shock to my system. It was good that it was confined to the capsule. It gave me some relief. Having a catheter is weird. You walk around with this bag.

For someone who liked to be in control and make things happen, it felt like things were happening to me and they were out of my control. That’s a tough one to crack.

Support

Finding a Cancer Community

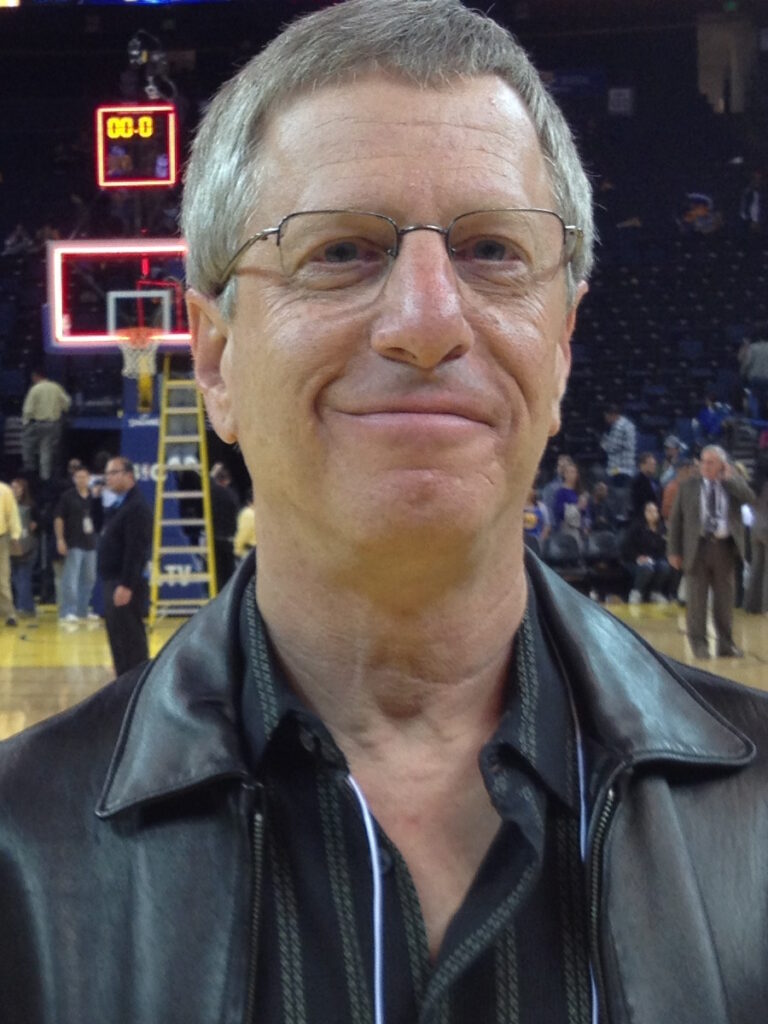

I joined the prostate cancer support group at MarinHealth. They offer so much information. It’s the guys who’ve been in the trenches. I don’t want to say they knew more than my doctors, but they’d all been to so many doctors. Some had surgery, some had radiation, and some were on active surveillance. They knew all the drugs.

I was 63. I never thought of myself as old. I thought of myself as young. Part of me still feels 18 or 25. You get a cancer diagnosis and a prostatectomy and you start to feel a little old fast because you’re wounded. There’s no certainty that you’re ever going to be whole again.

You wonder if you’re ever going to get your old life back. For someone who liked to be in control and make things happen, it felt like things were happening to me and they were out of my control. That’s a tough one to crack.

When you get a cancer diagnosis, you’re a member of a club. One thing that’s really positive about that is every man that I met who has gone through this wanted to support me. They’d call and say, “I’ll be happy to talk to you about it.” A lot of them say, “You’re going to get through this. It’s going to be okay.”

They talk about what happened after surgery, incontinence, drugs, shots, pumps, and all the sexual things that you think, I don’t even want to know about, but you do want to know about it. I felt like I was in a community, but at the same time, it was a community club I didn’t want to be in.

It was not pleasant to have to discuss the fact that my body had felt like it betrayed me.

Once you’ve been diagnosed with prostate cancer, all of a sudden this community opens up to other men who’ve gone through this and they all want to pay it forward. They all want to tell you about their experience and support you through yours to reduce the worry and to give you information you may not get from your doctors. There’s so much information from doctors that it’s overwhelming. To have more practical terms broken down step by step makes a huge difference.

When you’re one of the new guys in the cancer support group, you can feel the fear in the room. There’s a separation between people who’ve just found out who sometimes bring their wives with them, people who are trying to make a decision on how to be treated, and men who’ve been there and keep showing up over and over again to support you.

It was not pleasant to have to discuss the fact that my body had felt like it betrayed me. That was not an easy thing to talk about. I tried to be matter-of-fact about it, but I was definitely under a lot of pressure and stress.

These were now my people. It was healing in one sense, especially all the information they had that was easy to understand. But sometimes, there were people in there who were terrified. I had a hard time being around that energy.

As I went to more groups and more sessions, I realized it’s geared toward men who are just finding out they have prostate cancer. There’s a lot of that initial overwhelm.

Your doctors are great, but the support group provides things that the doctors don’t.

The Power of Having a Cancer Support Group

It was a safe space to talk because everybody in that room either has it or had it. It is important to unburden yourself however much you’re comfortable doing. The unspoken question for everybody is: how is this going to affect me as a man? That’s what people want to know. The cancer support group provides a place to share however much you want to share and ask any question you want to ask.

You’ll find out that your doctors are great, but the support group provides things that the doctors don’t. It provides emotional support. My doctors are compassionate, but it’s not their job to hold your hand. It’s their job to take care of you medically and to give you the facts.

Sometimes the facts are pretty scary — the percentages of survival, the percentages of when the disease could come back. I encourage men to go to prostate cancer support groups and decide for themselves. Is this for me? How much do I want to share? Are there men I want to stay in touch with during this or afterward? There are a lot of men who come there.

If they’re not done with prostate cancer, they’ve been dealing with it for a long time. They’ll tell you almost anything you want to know. It’s a chance to be around experienced veterans. You can always call someone outside of the meetings. I called the person who leads our group, Stan Rosenfeld, my prostate cancer rabbi because I could call him anytime. There wasn’t anything I couldn’t ask.

Having Someone to Answer Your Cancer Questions

It took some of the angst out of it. It made it accessible. The information was accessible whether or not I liked hearing it. Cancer is not fun. You’re not at a men’s group to talk about work and family. You’re dealing with your mortality, but there’s no other space quite like it. You’re amongst your peers and they’re going through the same thing you are.

I didn’t get into saying I’m really scared. You don’t hear me say things like that, but you can feel it. I’m sure they can feel it. The sense of empathy and caring and wanting to make men feel informed, that’s part of being a little bit more in control if you really understand your options.

They know we’re scared. I didn’t feel the need to say, ‘I’m really, really scared.’

Not Discussing Feeling Afraid

It’s not my nature. I’m not going to say I’m scared shitless. I’m afraid I’m going to die. I have no control over this and my life will never be the same. That’s not what I wanted to share with them.

I wanted them to give me some information and hear some solutions. Sometimes that’s what we’re looking for, solutions. You have a big problem and sometimes there aren’t solutions other than looking for second opinions and third opinions. Facts are facts. You’ve got prostate cancer, this is your Gleason score, and you have to deal with that.

It’s a foreign experience to be in a group. All of a sudden, you found out you had prostate cancer and you’re in a group of 20 men who also either had or have prostate cancer.

Oncologists use the term “no current evidence of disease,” but they never use the word “cure.” It’s really strange at first to be in this room with all these other people going through the same crisis. They know we’re scared. I didn’t feel the need to say, “I’m really, really scared.”

I did express a lot that I didn’t know what to do. I have two choices: surgery and radiation. Ideally, I’d like to find a way not to have to do either. Radiation also involves hormone deprivation therapy and that’s a whole thing in itself.

I felt comfortable in the sense that there wasn’t anything I couldn’t share. I honored my feelings about it. This is as much as I do want to share. I know I can say anything I want and they will support me and give me information and advice. You have to decide what your comfort level is. You have to become your own medical advocate.

It’s a very different energy to be around men in the same boat.

Discussing a Cancer Diagnosis

I’ve dealt with a lot of doctors. I have a team. It’s double figures of how many doctors I have. Part of that is because there were complications.

I didn’t talk to my doctors about my emotions. I said to my main oncologist, Dr. Terry Friedlander, “I’m scared. I don’t know what to do.” He was very compassionate and said, “I understand. It’s really hard.” But he hadn’t had the surgery. He was dealing with it every day as a doctor. It’s a very different energy to be around men in the same boat.

Wendi was there with me the first or second time. It was good to have her support, but I think she became more scared. When she heard about some of these stories, the reality started to hit.

That’s one of the things about a support group; it’s all about reality. This is what you’re going through, these are your options, here’s what a lot of us have learned, here are some of the doctors we recommend, and here are medications or things you can try. It’s like going to a diner with a big menu with pages and pages to choose from.

Not Being Informed About the Medical Situation

The ball was dropped a couple of times. The first time was when I wasn’t told that one-third of men who have a prostatectomy will need salvage radiation later on. I’m going into my healing stage thinking it’s done, it was confined to the capsule. I did have side effects from this wound in my body that took a while to heal. When you’re practicing your Kegels and doing all these things like the catheter for 2 weeks, that was really weird and very uncomfortable. It was a relief when I got that out.

I thought I was done. They said I got it all. All these feelings came rushing back, except this time, they were stronger.

Relapse

The other thing was because of the pandemic, I wasn’t getting regular PSA tests and I thought I’d been cured. I wasn’t told that I needed to get one every 3 months. It probably wasn’t until almost a year and a half later, maybe 2 years later, that I took a PSA test and it wasn’t 0.002, which is what they say no evidence of disease. That’s 0 because they always put the 2 there because it’s immeasurable at some point.

I thought I was done. They said I got it all. All these feelings came rushing back, except this time, they were stronger. It’s back. You may never get rid of it at this point. That’s what it felt like to me. I looked for all these different ways to not have to go into radiation hormone therapy.

I had two pretty serious complications. There was a history of frontal temporal dementia in my family, which was genetic, so I had to get tested with the psychiatric oncology program, and that took a while. When they tell you to see a specialist, it can take months. My doctors made things much easier. They put a word in.

I asked for a routine EKG when I was ready to start hormone therapy. As it turned out, there were some issues, like ischemia and an enlarged heart. Now I had to go through cardiology oncology. That was also resolved as not an issue with ADT and radiation.

Having a Good Medical Care Team

UCSF has some of the best doctors in the world. I was very fortunate to be near a teaching hospital. There are three in California – UCLA, Stanford, and UCSF. I was lucky I had access to some of the best doctors in the world, but I was knocked for a loop. I went into this I can’t believe this is happening mentality.

I did four PSMAs because I don’t want to get radiated because in my mind, if we don’t know where we’re radiating, that’s like carpet bombing versus guided missiles.

PSMAs are good at seeing clumps or tumors where cells congregate. Individual cancer cells are microscopic. In my case, they couldn’t find them. I’m going to have to make a decision in good faith. This is when I found my mind-body medicine person. That was when the whole cancer experience shifted.

The closer you are to people, the more it affects them. It shocks and scares the people who love you.

Reaction to the Prostate Cancer Relapsing

I was even more closed-mouthed when it came back. I did not want to share that news.

I had made a decision about treatment, so I didn’t need any questions about what I was going to do. I did tell my confidants and our kids. I can feel it when I tell somebody it’s not good news.

The closer you are to people, the more it affects them. It shocks and scares the people who love you. It hits home for them. If you’re talking to medical professionals or a support group, it’s more matter-of-fact. I didn’t want to talk about it. I even skipped a family reunion.

I decided I was going to work with a cancer coach. What I found was there’s work for me to do that makes me feel like I do have some control over this and it can change my outlook on what’s happening now and what’s going to happen next. This was a game-changer.

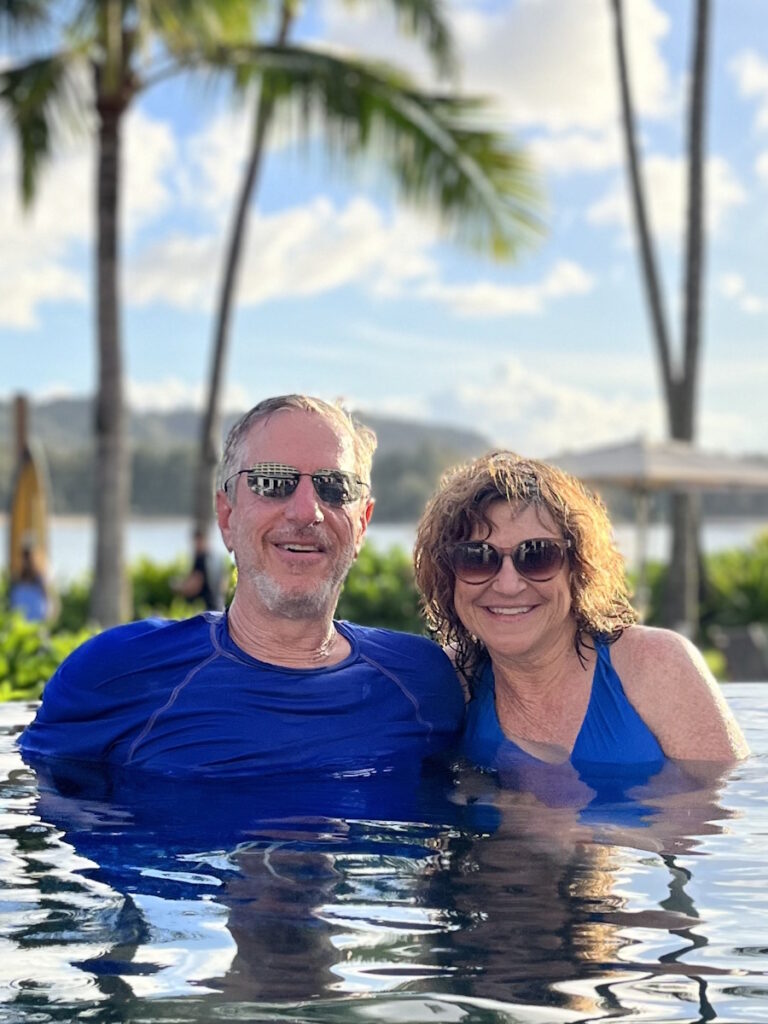

I was so fortunate to have a partner who I knew would be there and would provide the support and confidence.

Telling Loved Ones About Relapsing

I knew I could tell Wendi and that the reaction would be we’re going to get through this. I was so fortunate to have a partner who I knew would be there and would provide the support and confidence that I couldn’t feel right away and for some time, actually. My good friends also supported me.

My children stepped up. They didn’t break down crying. It was more, “I’m really sorry. We’ll be there for you, whatever you need.” I know that not everybody has that in their lives. Some people are alone with this, so I was fortunate.

I went back to the prostate cancer support group and they’re very matter-of-fact.

They talk about hormone therapy, different hormone therapy drugs, and different kinds of radiation. I felt like I’ve been there once before, so I know what I can get from the prostate cancer support group. I know I can go there and get some answers and very solid information from people who’ve been there and done that. I felt like I could ask anything.

Hormone therapy and radiation are tough on the body. Men aren’t prepared for menopause.

Effects of Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy affects everyone differently, as does radiation. Surgery is very straightforward. They cut out your prostate. Now that I was entering into this more nebulous treatment, you hear about hot flashes, loss of libido, weight gain, and reduced bone density.

You alter your diet, increase your exercise routine as much as you can, and do focused meditations to help balance the treatment you’re getting. Hormone therapy and radiation are tough on the body. Men aren’t prepared for “manopause.” We suddenly develop a lot of empathy for middle-aged women at that point. It’s a whole new ballgame.

If I had a question about treatment, radiation, or hormone therapy, I felt like I could get really solid information and things I didn’t necessarily even hear from my doctors. Not that my doctors aren’t super knowledgeable, but I think doctors and radiation oncologists stay in their lane. When you go to a cancer support group, there are no lanes. It’s whatever you need.

Do you want to talk about hormone therapy? We’ll talk about it. Do you want to talk about sexual function? We’ll talk about it. Do you want to talk about radiation effects? We’ll talk about it.

There are things some of these men have been doing for decades and decades. They know all the doctors. They know all the different symposiums, papers that are out there, and the statistics.

There was no sign of disease. I admit it’s a struggle for me to fully accept that’s great news when I know that I’m going to have to keep testing for years to come.

Navigating Cancer Statistics & Survival Rates

I asked my oncologist, “What are the chances we’re going to get this eradicated and I’ll be done with this?” What really shocked me was it’s not 100% based on your age, your Gleason scores, Decipher scores, and genomic scores.

I got different numbers from different doctors. Some would say, “Based on statistics and studies, you have a 25% chance of living 10 or 15 years. This is what the studies show for men with your Gleason score, with your surgery, and with your Decipher score. These are what the statistics show.” That’s sobering because now you’re talking about death and that’s something nobody wants to talk about.

You’re in uncharted territory. You don’t know and they don’t know. Every time you take a PSA test, there’s no current evidence of disease.

The good news is I had my first 3-month past treatment PSA test and there was no sign of disease. I admit it’s a struggle for me to fully accept that’s great news when I know that I’m going to have to keep testing for years to come.

This is where the mind-body medicine comes in. I changed my attitude. I got this. I’m going to keep this cancer out of my body and I’m going to do everything I can to stay healthy. That was a turning point in my treatment.

I had oncology tumor boards meet twice about my case because, between neurology and cardiology, it’s a little more complicated. They all said the same thing: hormone therapy and radiation.

I wanted someone who was totally in my corner, but who was going to support me and push me.

Coping with Your Cancer Diagnosis

Having a Cancer Coach

I know the value of a coach. I used to work with the top coaches in professional basketball, so I know we need teachers, mentors, and particularly coaches. Coaches provide not only expertise but also support. They will call you on things that you need to address with the goal of getting better. You’re improving and gaining new skills. The term cancer coach appealed to me because I’d done enough personal therapy over the years that I was talked out.

There are therapists you can talk to. There are a lot of people at UCSF. I talked to palliative care and counselors. They’re great, but they weren’t going to be there for me day in and day out. That’s not their job and they’re busy, so the idea of having a coach appealed to me. He was filling a role that I needed.

I wanted someone who was totally in my corner, but who was going to support me and push me. At that point, I was not feeling optimistic. I was scared and pessimistic. Maybe skeptical, but I was not feeling optimistic.

I learned I could gain practical tools like meditations, cancer visualizations, writing in a gratitude journal, and self-hypnosis. All of a sudden I realized that this is something I’m in control of. When you also focus on gratitude, your life perspective changes. It shifts from what isn’t working to what’s working in my life. We know what’s not working with cancer. What’s working and how can I make it work even better? How can my mindset work even better?

Mind-body medicine sounds confusing to people. What does that really mean? It means using the power of our minds to lift us up into not necessarily being in control but playing our part, being in the game, and not just counting on our doctors.

I embraced the concept that I had a role in my healing. I signed up for it. I was doing hormone therapy, practicing these tools, and using my mind and spirit to become a part of my healing.

Fear was going to make things worse. Fear wasn’t healthy.

Letting Go of Fear

I was letting go of a lot of the fear and feeling like I could be in charge of what was happening to me. That shifted everything.

When you’re diagnosed with cancer, you have this feeling that the doctors are in control, the universe is in control, and you’re not in control. There are practical things I can do to support my doctors and to push it to another level where I’m part of the healing.

I would wholeheartedly recommend people consider having a cancer coach or somebody who’s going to be there to push you to be your highest, most positive, and most powerful self.

Being part of my own healing was new for me. I learned that the fear was going to make things worse. Fear wasn’t healthy for me. Optimism and practical everyday tools helped me feel like I was attacking the cancer.

I used visualization exercises. When I was underneath the linear accelerator, I would envision drones zapping the cancer cells in my body. I swim laps 3 or 4 times a week. When I was in the water, I visualized dolphins zapping my body with sonar. Other times, it was waves washing the cancer cells out.

I focused on being part of my healing and that was really powerful. I kept to my gratitude journaling. I wake up in the morning and ask: what am I grateful for? I go to bed at night and ask: what am I grateful for? And that’s a different mindset than what am I scared of.

Practical Things to Improve Cancer Journey

There is integrative oncology. There are departments in integrative oncology, so it’s not just surgery and radiation. UCSF has an integrative oncology department.

You also have the Internet, which is actually a Pandora’s box because it can scare the living daylights out of you. You can find out things that you might not have known on your own.

With this kind of medical crisis, you can decide who you really want to be in your life. You can see who you really are and how you want to live.

The Power of Sharing Your Cancer Story

I never thought I’d write about my prostate cancer. Then I got to the point where I wanted to pay it forward. As a storyteller, I realized that’s how I could pay it forward. I knew I could share my experience in a way that was very accessible.

I started to write it knowing that I didn’t have to share it with anyone. I’m an inveterate rewriter and that’s what I think makes great writing. People are willing to rethink and rewrite. I’ve been an essayist for decades, so I know how to tell that kind of story.

I started writing it and kept it to myself. I’d come back and write some more. I’d come back and go at it again. I have a friend who’s a writing coach and editor. She looked at it and gave me suggestions. I kept working at it. I showed it to my cancer coach and after a while, I thought, I will tell this story. I will take that huge leap of faith — and when I say huge, I mean huge.

I tried to put some humor in it. It was dark humor, but I felt like this was a way for me to make the best possible use of my experience by sharing my story with other people. I still feel like that’s my gift to give and my way of paying it forward.

I don’t wish this cancer on anybody. I know what it’s like to be diagnosed with prostate cancer not once but twice. Even though there’s a lot of fear, angst, and uncertainty, there can also be a silver lining to having cancer. With this kind of medical crisis, you can decide who you really want to be in your life. You can see who you really are and how you want to live. That’s what these life crises often give you the opportunity to do.

I didn’t want to live in fear and be tagged as the cancer guy. I wanted to live fully. I wanted to do things in life that I may be putting off. I felt like I’d been given a gift. Now it’s time to share this gift with others. I can’t cure their cancer, but I can tell them things that, from my experience, changed everything.

I do recommend that people ask their family, including those who’ve passed, if there was a history of cancer.

Talking About Family Medical History

What happens with families is when someone passes, they take their stories with them. Unless you’re one of these people who’ve done interviews or videos of the elders, you’re not going to know directly from them because they’re gone. Their kids, my cousins, are mostly on the East Coast. I’m not really close with my cousins, so I’ve never asked them. I never asked what their fathers passed away from.

Turns out both of my uncles died of prostate cancer. I believe they were in their late 70s or early 80s. That was a real surprise. It was one of those things I probably didn’t want to know about because that made me worry even more. It would have helped to know because my doctors would have wanted to know. My brother had anal cancer, but that’s not related to prostate cancer.

I do recommend that people ask their family, including those who’ve passed, if there was a history of cancer and, with men, prostate cancer. It does give your doctor information that will help in the long run.

It’s the same thing with the genetic disposition of dementia in my family. You want to tell your cousins about this. We think my father had it. He was the one who started with it or it could have been his grandfather, but who knows? If they’re my uncles, they’re brothers, part of that same family, so they should know about it too because it could be passed on to them and to their children.

Laughter is the Best Medicine

To me, the old adage that laughter is the best medicine is true. It’s scientifically proven. It raises your endorphins and dopamine levels, and your blood pressure lowers. It’s all the good stuff. It’s so much fun and so bonding with other people.

When you’re in a group of people, it can be very healing. It can be very powerful because it opens your heart. Having prostate cancer, your heart tends to close down. You clench in your body, your heart, and your mind. Anything that can unclench your mind, body, and spirit, anything that can relax, release, and bring pleasure and joy, that’s big medicine.

Prostate cancer is not the only thing going on in your life. Find other things to balance it out.

Focusing on the Positive

My dog is some of the most powerful medicine I can have by being around her, loving her all the time, and feeling that affection coming back. Things that make you smile are important.

Cancer is not funny. It’s not happy. But there are still things in life that are joyful. I urge men who are dealing with cancer to find joy or at least something they’re grateful for. It could be that you’re alive, that the sun is out, you have a roof over your head, food, family, or a good job, whatever it is.

While this is going on, it’s not the only thing in your life. Prostate cancer is not the only thing going on in your life. Find other things to balance it out. I’m still living, I’m still here, and I’m going to make the best of this. I’m going to trust my doctors. I’m going to trust my mind and my body to help me heal. Again, laughter was one of them for me and still is.

Don’t think about it as a death sentence. Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men, but if you read the statistics, that’s only about 35,000 men a year. That’s a very small number. Hundreds of thousands are diagnosed with various types of cancer each year.

Doctors will tell you that most men die with prostate cancer, not of prostate cancer. You may get into your 70s or 80s and have prostate cancer and they may say, “Your Gleason scores are low. We don’t need to treat you unless you really want to be treated. Go on and live your life.”

Don’t go down with the ship. Shit happens, things happen, life happens. Deal with it. As much as I didn’t want to hear, “It’s a good cancer,” prostate cancer is a lot better than some of the others. There are resources and there is hope. That’s all we want. We want hope.

A man talking to women about prostate cancer is a little strange because you’re talking about the most private part of your body and what could be permanent side effects.

Why Story Resonates with Women

Women open their hearts and deal with cancer in a different way. They’re in touch with their emotions. They talk to other women about their deepest, most private feelings, not even hesitating sometimes, and even with strangers. I wasn’t totally surprised that women were the ones who were commenting and highlighting my essay on Medium because women are naturally focused on healing, communication, compassion, and love.

That’s not to say men aren’t. We’re more like onions. You have to peel away the layers. I always think of Shrek, where the donkey says, “You’re like an onion. You got to peel away the layers to get to the good parts.”

A man talking to women about prostate cancer is a little strange because you’re talking about the most private part of your body and what could be permanent side effects. I had a lot of reactions to hormone therapy from women saying, “Welcome to my world.”

I’m very comfortable with women. I’ve always had really strong friendships with women. I wasn’t surprised by the support I got from women about sharing my story.

With prostate cancer, it’s like, ‘What kind of man am I going to be after this?’ That’s a pretty tough question for someone to deal with.

Words of Advice

When you’re first diagnosed with prostate cancer, it’s a shock and it’s easy to feel terrified and out of control. You have no control. When you talk to other men who’ve been there or who are there, you realize you’re not alone.

In my support group, there was nothing I couldn’t discuss. I could ask the most personal, private, emotional, mental, and physical questions. There was a sense of relief that I wasn’t in this alone. I have a resource outside of my doctors. Doctors are busy. They’ve got appointments left and right. The support group was, “You need us, call us.”

I was able to pay it forward to other men. If someone needed to talk about prostate cancer, they could call me. Some people are going to think of gratitude journaling and visualizing drones zapping the cancer away.

What you would hear from a support group is, “There are no guarantees, but here’s what we know, and here’s what worked for me.” There’s a big difference between saying, “You ought to,” and someone saying, “This was my experience,” and then you can ask them about their experience.

Get out of your head. My mind was spinning and spinning with the same old questions and worries.

Go somewhere where you can get answers if you have questions and you’ll get support immediately as long as you need it. You can go for years if you have to. There’s no limitation.

They meet in person once a month. Men are more solitary creatures than women. I’m always amazed at women. They get together and within two minutes, they’re talking about the most personal parts of their lives. Men are more comfortable talking about what’s happening in our business, sports, and politics.

Sometimes, during a conversation about prostate cancer, I’ll say to some men that I know who’ve been diagnosed, “Let’s drop deep. Let’s cut the bullshit and get right to it.” With men, we’re in a place we’re not used to being. We’re feeling weak and scared. With prostate cancer, it’s like, “What kind of man am I going to be after this?” That’s a pretty tough question for someone to deal with.

It’s hard to get a diagnosis of prostate cancer, but there’s hope and there’s healing. There’s a silver lining.

I’m taking on this role. It’s not something I thought I’d do. I was lucky to find great doctors. I also had a coach that opened up a whole new world for me of self-healing. It was total serendipity and luck that I happened to find him through a Google search.

Every man has his own journey, his own path, and has to be his own medical advocate. You can’t just count on your doctors. You’ve got to ask questions.

You’d be well off to get second opinions and go to cancer support groups. You’ll hear things there that you won’t hear anywhere else. I came out of the cancer closet and felt like I had to pay it forward to other men and participate in something like this. I’ve been through this now. I’m still going through it, but I’ve been through this, and it’s an act of selflessness to want to help other people go through this.

It’s hard to get a diagnosis of prostate cancer, but there’s hope and there’s healing. There’s a silver lining in this. You can see parts of your life and ask: is this how I want to live? Is this who I really am? What do I want to do now? Not only do I want to be cured of cancer, but how do I want to live? What have I learned through this process?

Time is precious. We’re not guaranteed anything. We all go at any time. You read the newspaper every day and someone can die at 20. My dad lived to 98, but there are no guarantees in life.

If you’ve been diagnosed with prostate cancer, don’t waste your time and energy on the negative part of it. Trust your doctors. Trust whatever healers you end up with. Trust your men’s support group and most of all, trust yourself. Trust that you will find a way through this journey.

There’s no guarantee that you’re going to be cured. But listening to other men talk about this, you can see that you’re not alone and that there are happy endings or at least life changes that you didn’t know were possible. I put my story out there and I can continue to expand that story. I felt that I was doing something noble by taking that leap of faith and coming out of the cancer closet.

Special thanks again to Janssen for its support of our independent patient education content. The Patient Story retains full editorial control.

Inspired by Paul's story?

Share your story, too!

More Prostate Cancer Stories

Rob M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Burning sensation while urinating, erectile dysfunction

Treatments: Surgeries (radical prostatectomy, artificial urinary sphincter to address incontinence, penile prosthesis), radiation therapy (EBRT), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy or ADT)

John B., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9, Stage 4A

Symptoms: Nocturia (frequent urination at night), weak stream of urine

Treatments: Surgery (prostatectomy), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy), radiation

Eve G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels detected during annual physicals

Treatments: Surgeries (robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy & bilateral orchiectomy), radiation, hormone therapy

Lonnie V., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Urination issues, general body pain, severe lower body pain

Treatments: Hormone therapy, targeted therapy (through clinical trial), radiation

Paul G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery), radiation, hormone therapy

Tim J., Prostate Cancer, Stage 1

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery)

Mark K., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptom: Inability to walk

Treatments: Chemotherapy, monthly injection for lungs

Mical R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 2

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level detected at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Jeffrey P., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; routine PSA test, then IsoPSA test

Treatment: Laparoscopic prostatectomy

Theo W., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level of 72

Treatments: Surgery, radiation

Dennis G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9 (Contained)

Symptoms: Urinating more frequently middle of night, slower urine flow

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Lupron)

Bruce M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4A, Gleason 8/9

Symptom: Urination changes

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Casodex & Lupron)

Al Roker, Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7+, Aggressive

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level caught at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Steve R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4, Gleason 6

Symptom: Rising PSA level

Treatments: IMRT (radiation therapy), brachytherapy, surgery, and lutetium-177

Clarence S., Prostate Cancer, Low Gleason Score

Symptom: None; fluctuating PSA levels

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)