The Latest in DLBCL Treatments

What Clinical Trials are Available to Me?

Edited by:

Katrina Villareal

Experts and patients discuss the latest in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Dr. Josh Brody of Mount Sinai Hospital, clinical trial nurse navigator Crissy Kus of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and DLBCL survivor Dr. Robyn Stacy-Humphries share the new DLBCL research, treatments, clinical trials, and expert advice.

Brought to you in partnership with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and its Clinical Trial Support Center.

- Introduction

- What is DLBCL?

- Risk of relapse with DLBCL

- What is a clinical trial?

- What is CAR T-cell therapy?

- What are bispecific antibodies?

- New DLBCL clinical trials

- Different phases of clinical trials

- Low enrollment for adult clinical trials

- Travel costs in clinical trial participation

- Clinical trial paperwork

- Final takeaways

Introduction

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, everyone! This discussion is hosted by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and The Patient Story.

I was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma a few years ago and went through hundreds of hours of good, old-fashioned chemotherapy.

Thankfully, our discussion is all about other options that are happening, that have been approved, and that are in the pipeline.

We hear about clinical trials and the term itself can be so daunting. What are clinical trials? Our goal is for you to walk away from this with a much better understanding of what a clinical trial is and if it’s a good option for you or your loved one.

The Patient Story features hundreds of in-depth and authentic patient stories across cancers and conversations with top cancer specialists. The goal is to humanize cancer so that you know that you are not alone. Sign up to be part of our community and you’ll get first access to these programs, new updates, and stories.

We’re proud to be hosting this also with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, the world’s largest nonprofit health organization dedicated to funding blood cancer research and offering patient services and education. It has great resources from information specialists who help answer cancer questions to help pay for cancer care costs, including travel for CAR T-cell therapy.

I’m really excited to introduce our panelists. We’re really, really grateful to have them with us.

First off, someone I was lucky to meet at one of these big conferences. A very busy guy. I’m really excited that he’s spending the time with us. Dr. Joshua Brody, director of the Lymphoma Immunotherapy Program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Dr. Josh Brody: Thank you so much. This is a great opportunity. It’s really nice to try to reach out to talk to people as directly as we can.

I run the Lymphoma Immunotherapy Program here at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. At Mount Sinai, we are very lucky to be an NCI-designated cancer center where one of our missions beyond patient care is trying to get the next generation of patient care, which is part of developing clinical trials and helping to get patients access to newer, hopefully, better and safer therapies.

I was committed to becoming a cancer doctor from the time I was six years old. As that developed, the plan was for me to become a cancer doctor who develops new immunotherapies for cancer.

We’re very lucky to have the best precedent of immunotherapies helping patients with lymphomas. Even what you called the standard old chemotherapy is not that old because rituximab is an immunotherapy that is part of that old chemotherapy and when I started doing this, rituximab was not even a therapy.

Immunotherapy has a great precedent. Using the patient’s own immune system to help fight their cancer has a great precedent in lymphoma and that is part of what got me interested in lymphoma.

I was doing my training at Stanford in California and it’s a very well-known lymphoma place so it was a great opportunity to hopefully become great at what they are great at. There were a few things converging to get me to become a lymphoma doctor and now I’ve been doing it for a while.

Stephanie: Really grateful that we have people like you who’ve been in this for so long and are so dedicated to helping to figure out what is effective and also what will help with quality of life.

Next, we have Crissy Kus, a nurse navigator with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s Clinical Trial Support Center. We know that you are on the phone all the time helping patients and their family members.

Crissy Kus: Thanks, Stephanie. I became a nurse about 12 years ago and started my career early, moving around the units in the hospital every 4 to 6 weeks. After a year of doing that, I was allowed to choose a home unit. I knew pretty quickly that BMT was my home, working with patients with blood cancers.

I help patients specifically with CAR T-cell therapy and lymphoma. I’ve been with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society in the Clinical Trial Support Center. We’re a team of nurses who help patients and their families explore clinical trial options, learn about their treatment options, and navigate that whole journey — whether that’s proceeding with the standard of care and learning about those details and logistics or identifying barriers to participating in clinical trials and helping them overcome any of the barriers in the way of them participating.

Stephanie: Thank you, Crissy.

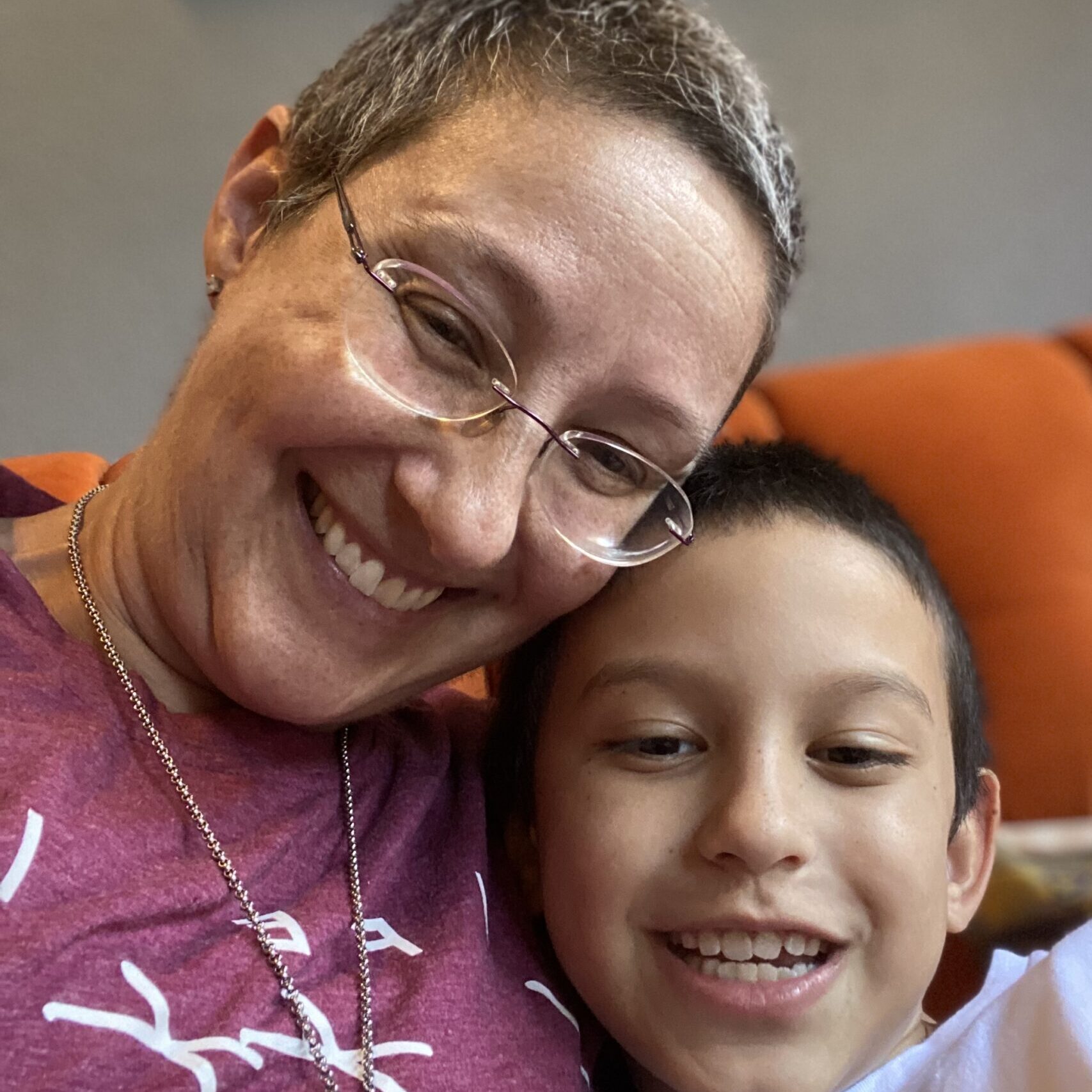

I’m also really excited to introduce our final panelist tonight, Dr. Robyn Stacy-Humphries, who has such an incredible story. Someone I’ve gotten to know and I feel very lucky to know you.

You have such an incredible perspective as someone who is a physician who got your own diagnosis not just once but going through treatment three times.

Dr. Robyn Stacy-Humphries: First of all, hats off to Dr. Brody. We’re very lucky to have him on this panel.

Like Dr. Brody, I actually wanted to be a doctor from the time I was five or six years old. I went to medical school and residency in radiology and my subspecialty is cancer-focused. I do body imaging, PET-CT, and mammography. I diagnose cancers and do biopsies.

Ironically, I was diagnosed with lymphoma in my late 40s. Very much of a shock to be on both sides of it. Both my parents passed away from cancer of different kinds and then I developed one myself.

Navigating the cancer world as both patient and physician has been unusual and that’s one of the reasons I’m thankful to be here. One of my missions is to try to give back, to try to bridge the gap between doctors and patients so that they can learn to talk to each other better. Patients can learn to advocate for themselves and doctors can perhaps understand where they’re coming from.

Stephanie: Thank you for being here and for offering a perspective that is very unique. We have two physicians on tonight who really care about the patient’s perspective.

This is a personal topic for me as well. DLBCL is all over my medical charts. I was 31 when I was diagnosed and like you, Robyn, there’s that shock. I remember trying to understand: what do these letters mean? Lots of alphabet soup coming at you when you get diagnosed with cancer of any kind.

What is DLBCL?

Stephanie: Dr. Brody, in as human terms as possible, what is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma? Are there some common first red flags or symptoms?

Dr. Brody: For Stephanie, I have to apologize for the alphabet soup. That’s a thing we do. We make up code names with lots of letters but not just to be confusing. There’s so much we’ve learned in decades that we make subsets of subsets and then we need more alphabet soup to describe all the subsets. PMBCL, DLBCL, non-GC — it’s letters on top of letters.

Anything that we can say in medicine or science, we should be able to say it in English as well. None of it’s so complicated that we shouldn’t be able to say it in English, especially when we’re talking to our patients. We have to be able to say things in a way that is understandable.

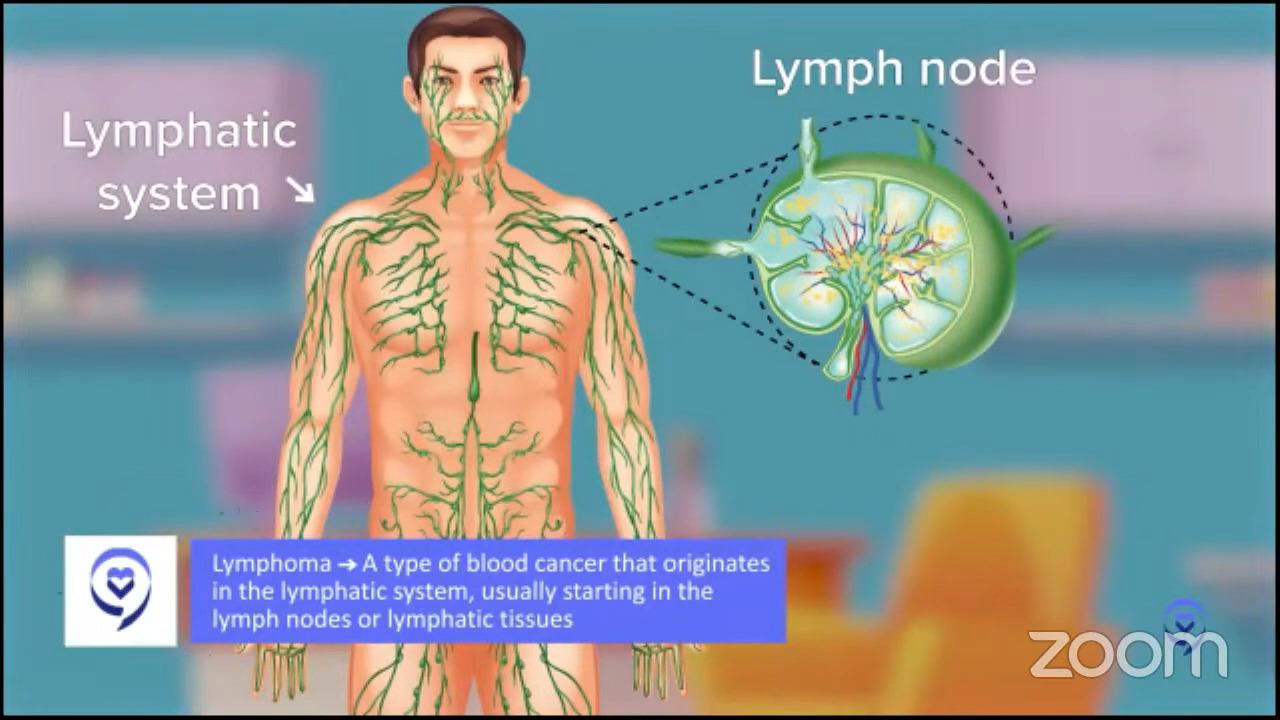

In regular English, lymphoma is a cancer of lymph cells. What are lymph cells? This is really simple. You think about breast cancer, cancer of breast cells, prostate cancer, cancer of prostate cells. It’s a healthy cell that becomes a cancer.

What are lymphocytes? Lymphocytes are a certain type of blood cell. They are specifically blood cells that may live in your lymph nodes. When you say swollen glands because you had a cold or a sore throat or something, those glands we’re talking about are usually lymph nodes.

Lymph nodes are all around your body. That’s the first tricky thing because when you think breast cancer, prostate cancer, you think, “Oh, I know where the breast is, where the prostate is,” so that makes sense. Lymphoma comes from lymphocytes, which mostly live in lymph nodes, so that could be anywhere in the body.

Common symptoms of lymphoma

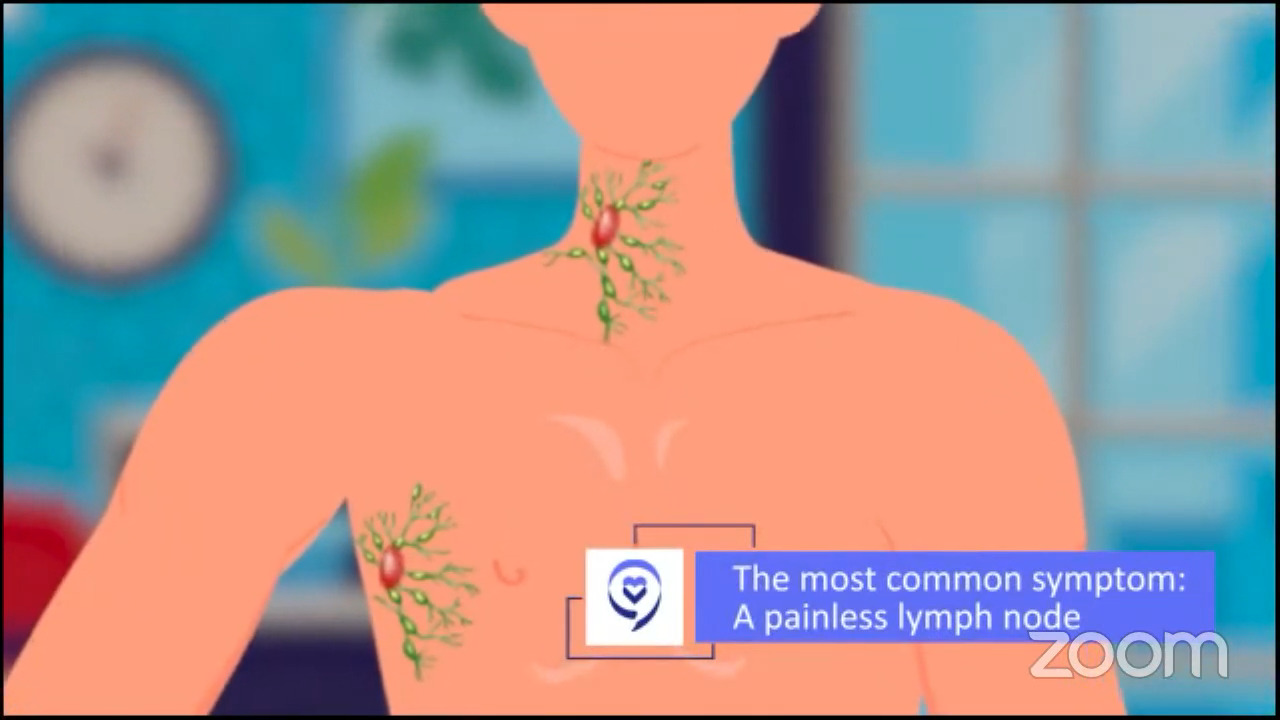

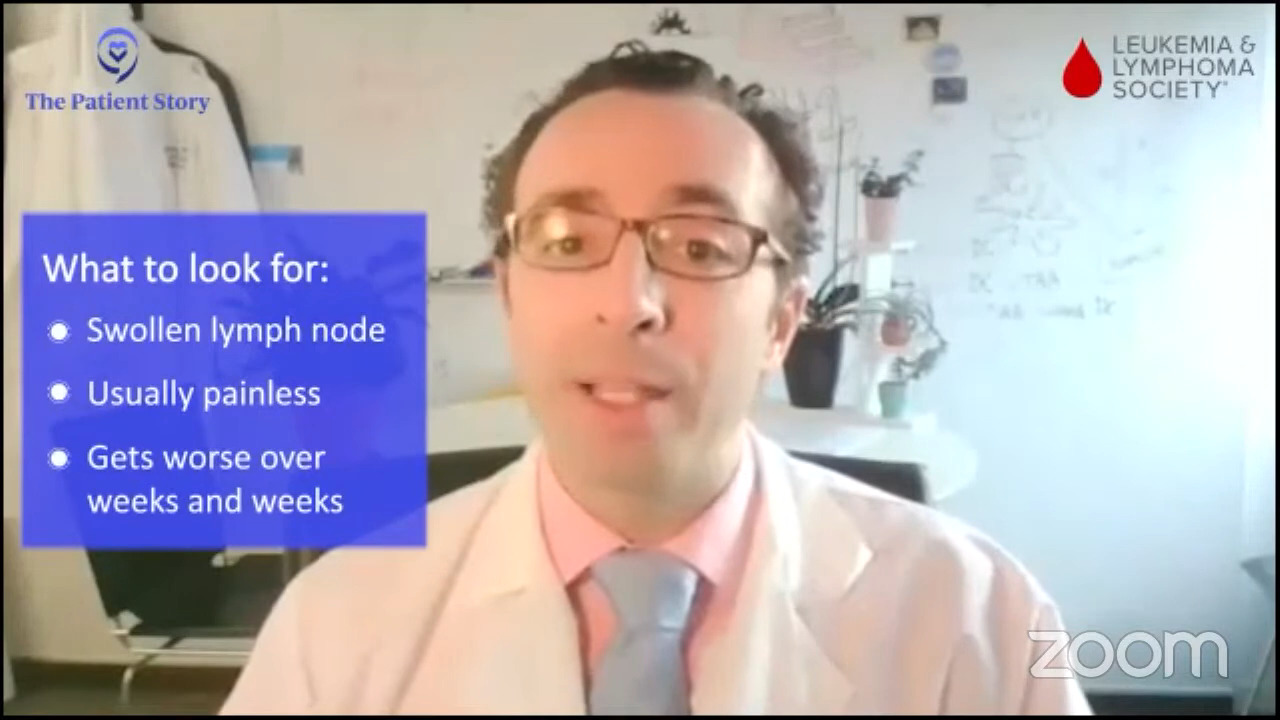

Dr. Brody: The common presenting symptoms of lymphoma depend on which lymph node area had a cell become cancerous. Amongst all of those possibilities, we still say that the most common presentation is a painless, swollen lymph node literally anywhere in the body.

There are subsets of lymphomas that don’t even show up in a lymph node per se. Sometimes we talk about primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. There are lymph nodes there, but they’re not in the common lymph node spots. We think of the neck, the underarms, and so forth. They just show up in the middle of the chest, the mediastinum. Nonetheless, the most common presenting symptom is a painless lymph node.

Lumps you get because you had a sore throat are not a painless lymph node. Usually, they are painful or tender lymph nodes. If you have a tender lymph node, that’s a little less likely to be lymphoma than inflammation as a result of a cold or sore throat.

Again, not every lymph node that gets a little bit swollen needs to be emergently evaluated. Otherwise, every person would have a swollen lymph node at some time or another.

The first thing we have to pour on this is a bit of common sense. You have a lymph node that’s a bit swollen for a few days. You can watch it for a few more days and if things start to recover on their own, probably you don’t need to go and get that swollen lymph node evaluated.

Lymph nodes that are swelling, usually painless, and getting worse over weeks and weeks and weeks need to be evaluated. Those are the most common presenting symptoms of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which is the highest incidence type of lymphoma.

Stephanie: I really appreciate you sharing the differences between what is more commonplace versus when you need to maybe get something checked out. People do get really worried.

Robyn’s DLBCL diagnosis

Stephanie: Robyn, you went through this yourself so it’d be great to hear from you. What was it for you that was a red flag that led to the diagnosis? Share a little bit about getting that diagnosis.

Robyn: I had a swollen lymph node, but it was an unusual location in what’s called your supraclavicular region. You never have normal lymph nodes there. When you have a cold, those don’t swell up. Usually, when you have a lymph node above your collarbone, it can be a symptom of lung cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, or even breast cancer.

I felt a lymph node literally while I was watching TV. I knew it was bad. It’s never good.

My process for diagnosis went very fast. I ended up with a CT the next day, which I looked at and found out I had lymphoma. I had lymph nodes all the way up and down my neck, which you couldn’t feel. They were all very small. There were too many of them.

I actually had some lymph nodes behind my nose and something called Waldeyer’s ring. I thought I had allergies. I was congested and that actually was lymphoma.

I really had no symptoms besides that. I was working 60 hours a week as a mother of three. I ran every day. I ate well.

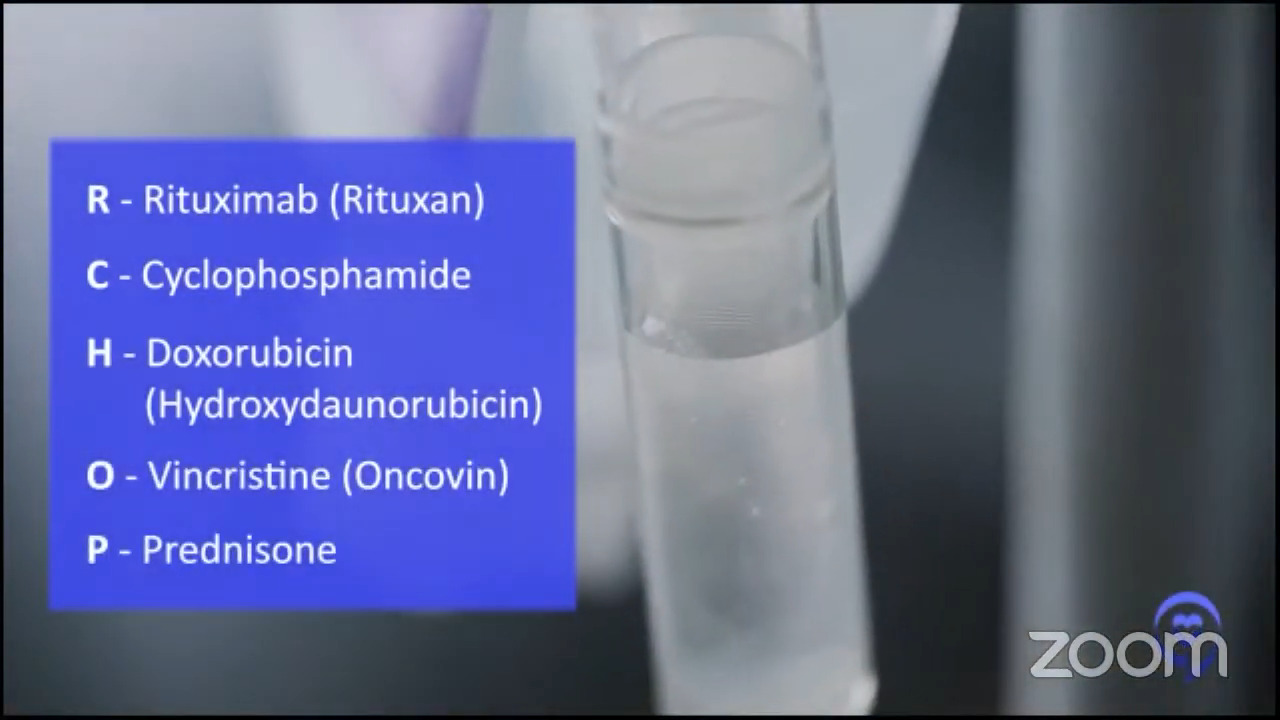

Everything went really fast. It was a shock. Before I knew it, I had a CT scan, a PET scan, and a port put in, and immediately started on R-CHOP, which is the standard therapy. It was initially very successful for me. It didn’t work later, but it was very successful at first.

I did six rounds of R-CHOP and as Dr. Brody said, rituximab changed everything. When I was in medical school, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cure rate was very low, only about 30 or 40%. Once you added rituximab, it’s over 70% in a lot of cases.

Things have progressed in the last 10 years. Now with the immunotherapies, things are totally different.

Stephanie: What a strange experience to have essentially self-diagnosed and have to read your own scans and images, but you do that for a living. I appreciate both of you talking about just how quickly things have changed in the last 10 to 15 years and even in the last five years or so with immunotherapy.

That’s what’s exciting to talk about but also why these programs are so necessary because it is a lot. It’s great to have people who specialize in this area so that there’s a depth of knowledge about all the different options and for whom these options are best.

Standard of care for DLBCL

Stephanie: Let’s talk about the standard of care. Dr. Brody, what has been the standard first-line treatment in DLBCL? We heard Robyn talk about R-CHOP.

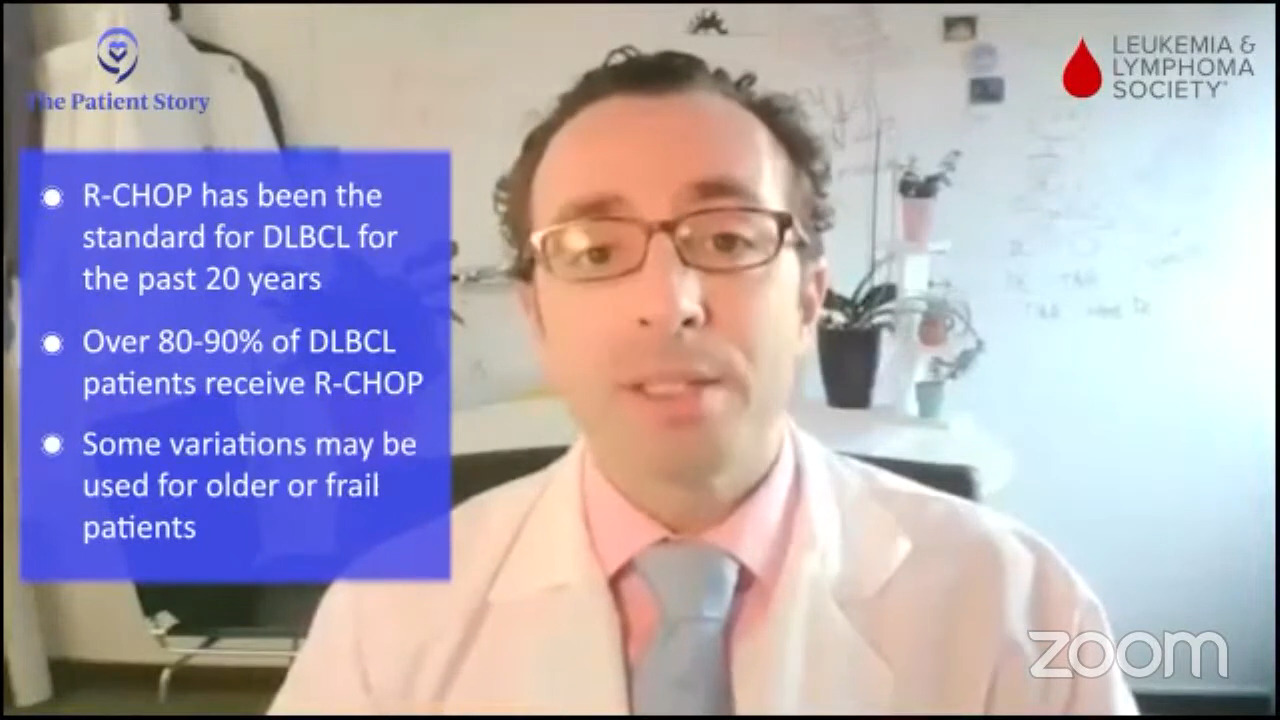

Dr. Brody: For the past 20 years, there’s been a bit of an evolution. R-CHOP has been the standard of care. It doesn’t mean that everyone gets R-CHOP, but most people do — certainly more than 80%, probably more than 90%.

Some people may not get R-CHOP maybe because it can be a little tough. We have patients who are in their 90s and they may get a gentler version of R-CHOP or even slight variations of that. We do have patients in their 90s who still get R-CHOP, but it’s not gentle therapy.

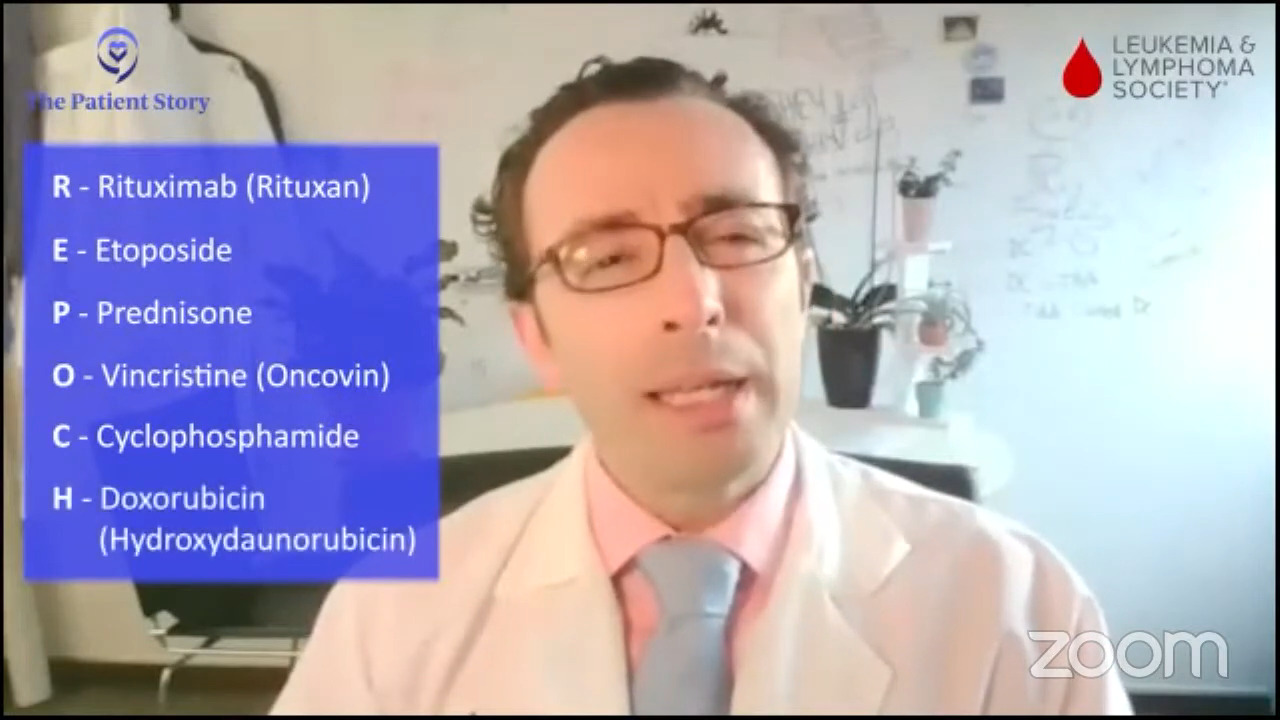

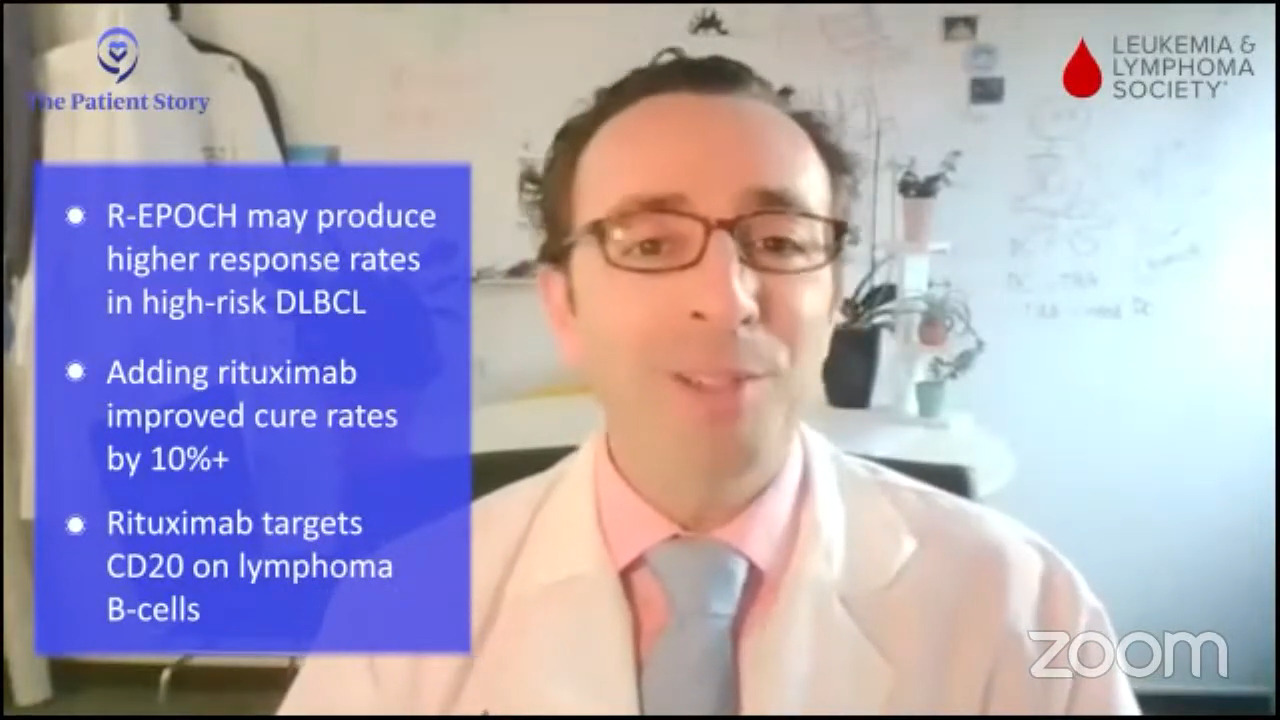

We sometimes give gentler versions and sometimes even more aggressive versions. There’s a therapy called R-EPOCH. It’s a tougher version of R-CHOP.

In some ways, it seems to be “better” in that it’s maybe more effective, but in a big randomized trial comparing the two, there wasn’t a clear difference. We think that R-EPOCH is just good for certain super high-risk subsets of patients so 5 or 10% of patients get R-EPOCH instead of R-CHOP.

That was a big evolution from the CHOP of the 90s and easily added a 10-plus percentage increase in the cure rate to standard therapy for patients with DLBCL so it’s a big, big deal.

I was very lucky because rituximab came out of Stanford and Biogen Idec-Genentech back in the early 2000s so it was an exciting time for us. We now enter the rituximab era of treating patients with DLBCL. Now we’re still seeing comparably exciting evolutions to what may be the standard going forward.

Stephanie: Amazing to have all that history and to be front and center when it was all going on; that must have been exciting.

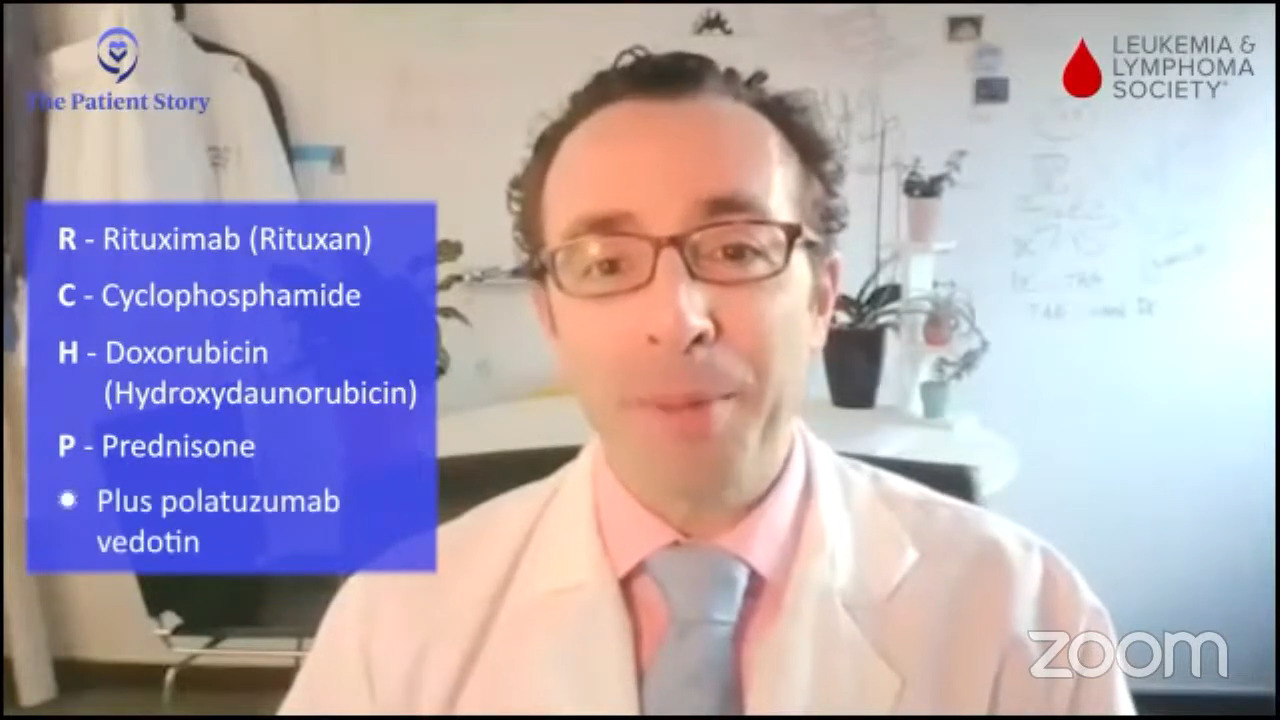

We have a recent approval, polatuzumab and R-CHP, which is R-CHOP without the O for first-line treatment. How much real-world data is there? What are your thoughts about it as another option for people?

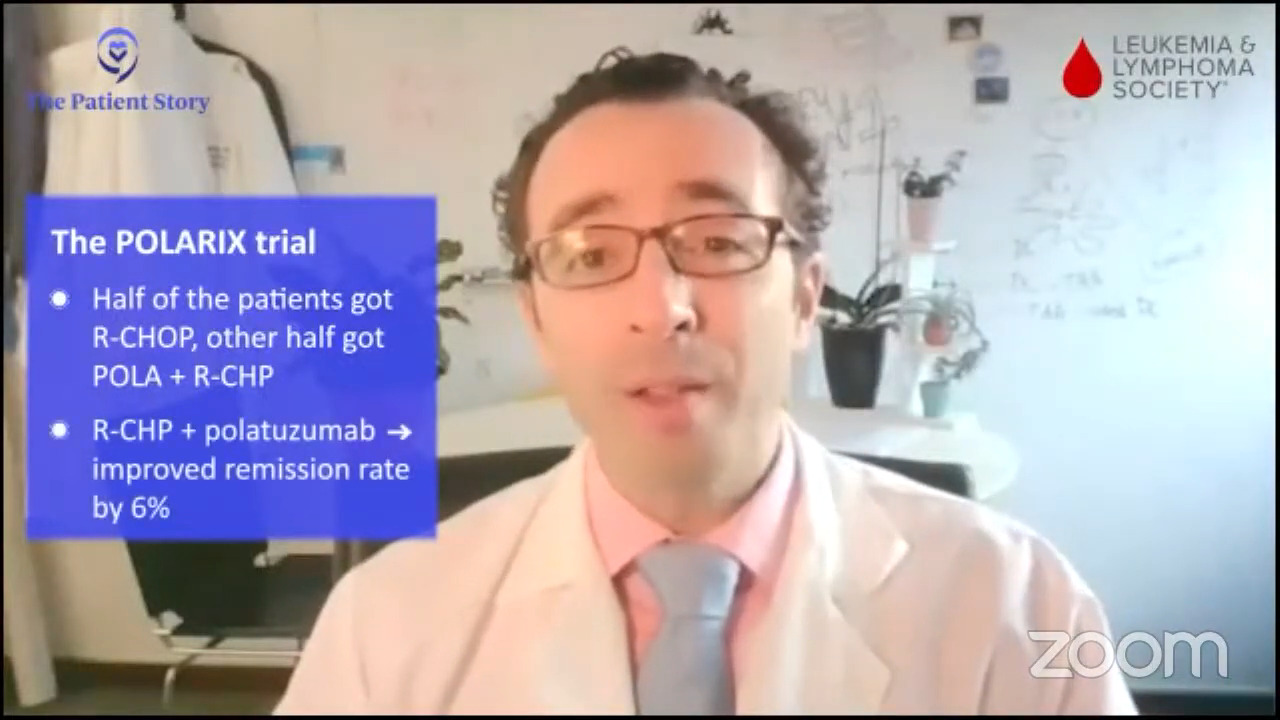

Dr. Brody: Pola-R-CHP, we say, is another option. It’s not the right answer, but it might be the right answer in the future. We’ll see.

There’s a randomized trial, POLARIX, where half of the patients got R-CHOP and half got pola-R-CHP. Pola-R-CHP was a bit more effective where 6% more people stayed in remission for the first couple of years. It’s possible that could eventually translate to an increased cure rate, but we need more time to follow those folks and see how they do.

But a 6% increase, staying in remission for two years, that’s not nothing. If you were one of those six out of 100 people, that’d be a big deal for you. The only catch is it’s not “for free” in that there are some extra side effects but not too bad. The risk of infections during the therapy was moderate, but it was also a bit increased in the pola-R-CHP. Interestingly, it was about a 6% increase on that side as well.

Maybe 6% percent more people staying in remission and maybe 6% more people getting this significant side effect. The side effect lands you in the hospital so it’s not nothing. A little bit tougher on lymphoma, but a little tougher on patients as well.

I wouldn’t say it’s the right therapy for everybody, but certainly, every lymphoma doctor is weighing each patient. It’s supposed to be personalized for each patient. This patient might do well because they’re younger, healthier, and wouldn’t have a high risk of side effects and this other patient may not do well.

A 90-year-old probably wouldn’t get pola-R-CHP because R-CHOP is already tough therapy for them. Higher-risk patients and certain subsets of high-risk patients might get the most benefit from the pola-R-CHP. Probably in the near future, maybe half of the patients are going to get pola-R-CHP and half are going to get R-CHOP.

Risk of relapse with DLBCL

Stephanie: That’s great. Thank you for sharing that and interesting to hear. We’d like to take in one of the patient questions actually. Wilson asks, “What’s the risk of relapse with DLBCL and what is the leading treatment for those who relapse?”

Dr. Brody: As Dr. Stacy-Humphries said, we cure the majority of patients. This is awesome not just compared to the 90s, but compared to the 70s when I had relatives that had this disease. We cure the majority of patients and that’s wonderful. It’s not 100% and we would like to get it there.

Today, we are curing more than 65% of patients, depending on which study you look at. A third of patients could still relapse.

These studies focus on slightly younger, slightly healthier patients. If you look at everybody, it’s probably about 65, maybe a little bit above that with “standard” 2023 therapies. We see that increasing as well over the next few years.

Relapsed/refractory DLBCL treatment

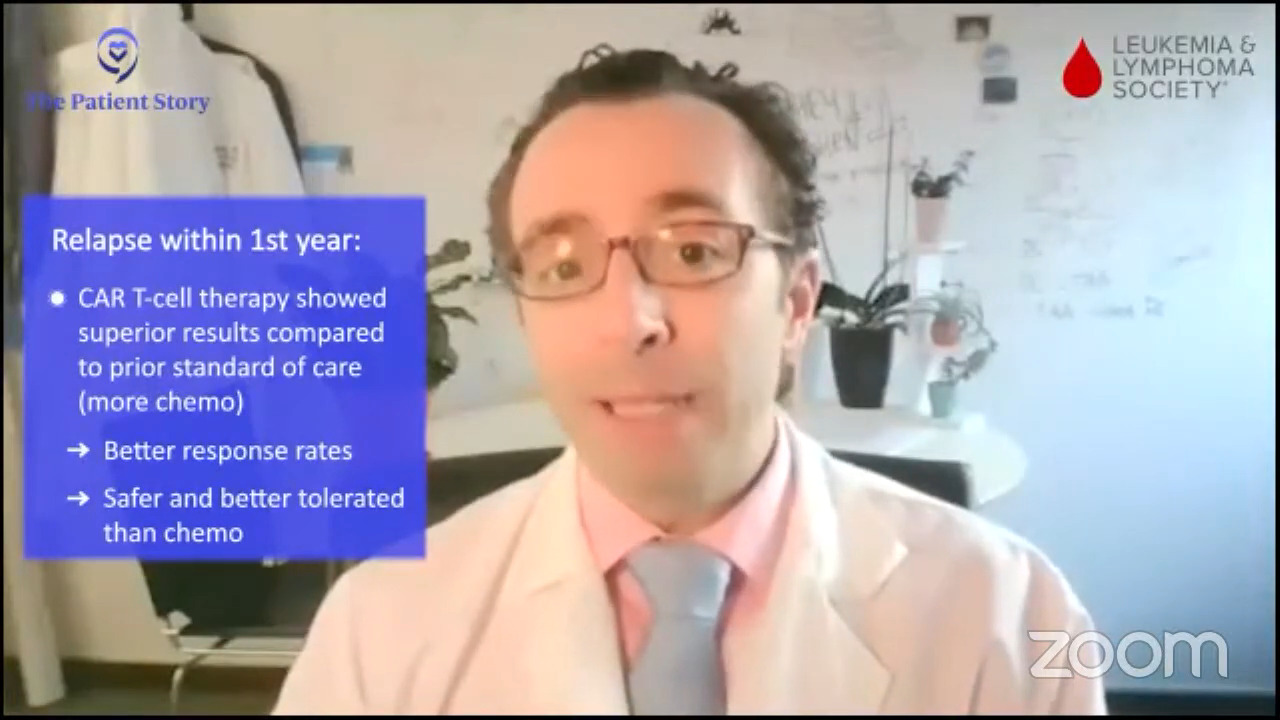

Dr. Brody: The standard of care for them depends on a few things. It depends on when they relapse. If patients relapse very quickly, within the first year, the approach is a bit different. The idea is they just got chemo and it didn’t work very well so giving something that kills cancer in a different way might be better.

In the TRANSFORM trial and the ZUMA-7 trial, early relapsers and people that didn’t get a good remission at all or refractory patients, CAR T cells were superior to the old standard.

The old standard was basically more chemo and actually a lot of chemo, which was tough therapy. Those trials both showed that CAR T was better. If you read between the lines, they were also, I would say, safer and better tolerated. That’s a rare win-win, both better and safer. We don’t get a lot of those in new cancer therapies.

With pola-R-CHP, it wasn’t really a win-win. It was maybe better, but not safer. CAR T versus the old standard of more chemo was a real win-win. For early relapses and refractory patients, CAR T is the standard of care. It doesn’t mean every patient has to get it; there’s still some individualization. But for the early relapsers, that’s been the big change over the past year and two. That was not the standard of care even a couple of years ago.

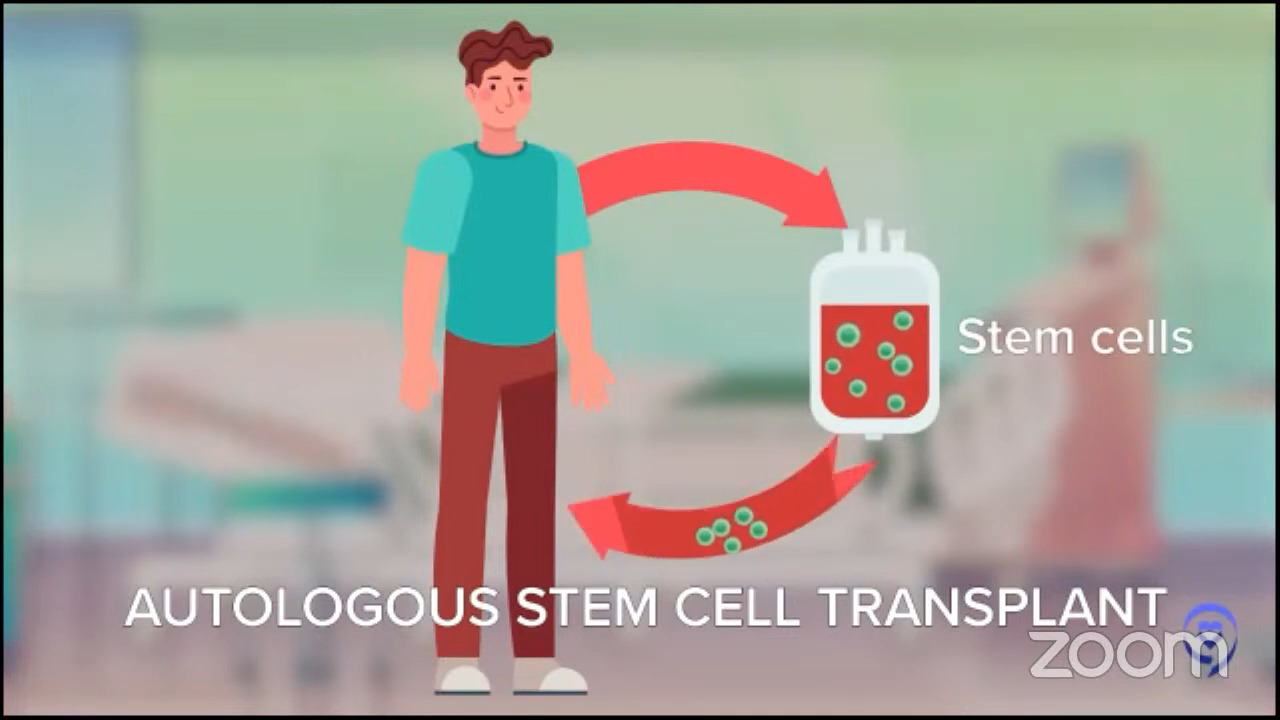

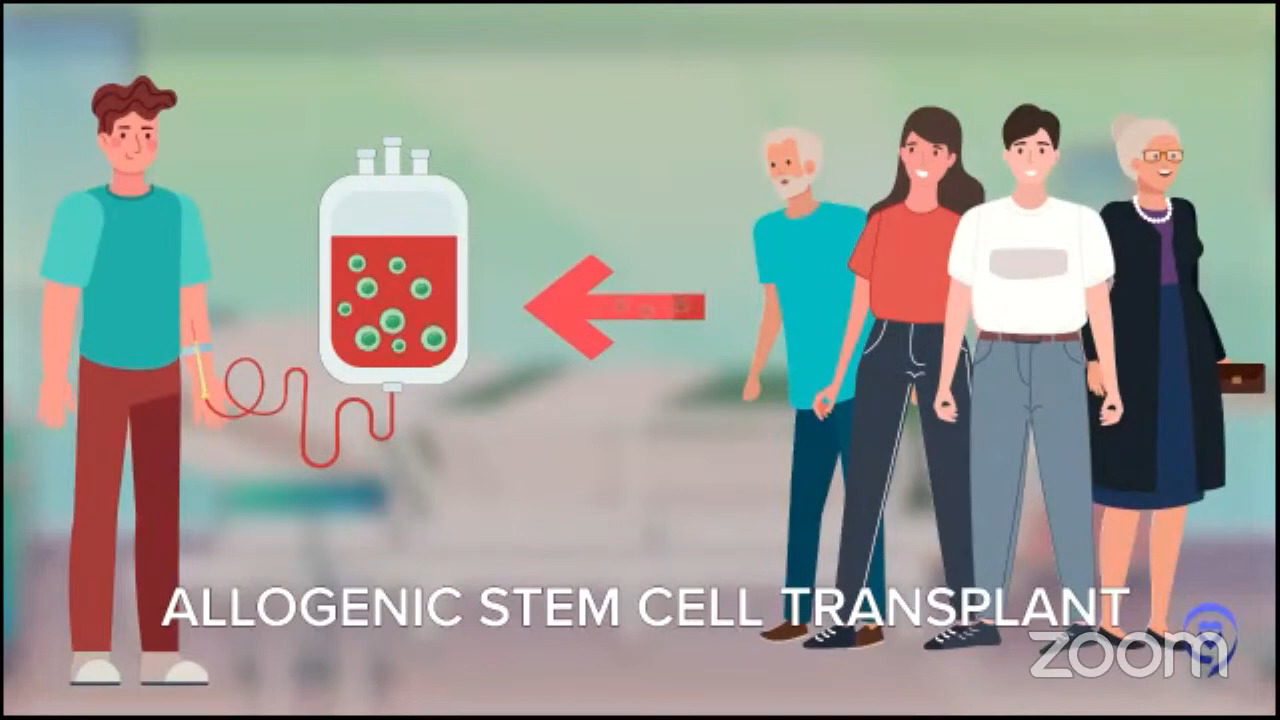

For patients whose disease relapses later, it’s even more individualized. The old standard for younger patients with late relapses was this mega dose chemo approach called autologous stem cell transplant. Autologous means you give the stem cells to yourself. We want to distinguish it from the other kind of transplant where you get stem cells from another person called an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

For people who relapse a little later and who are young and tough enough to tolerate this tough therapy, that is still the standard but that doesn’t really apply to every patient. When we did those first studies, they were for people under 60 then we started doing it for patients under 65. Now we do it for patients under 70.

It’s tough therapy for people who are around the median age of this disease, which is upper 60s and 70s. It’s standard of care, but a lot of times for those late relapsing patients, they may not be eligible for that approach. Thankfully, there’s a whole bunch of other more targeted options.

Robyn’s 1st DLBCL relapse

Stephanie: Robyn, you had a good response to R-CHOP in the beginning. As you mentioned, it didn’t stay that way. We’d love to understand more about what happened. How far along were you until you realized something was not right again?

Robyn: I was actually in complete remission for four years when my relapse happened in 2015. Again, I felt a lymph node in my neck, which I knew wasn’t supposed to be there.

As Dr. Brody said, the standard of care at that point was an autologous stem cell transplant. First, they give you salvage chemotherapy; RICE is what I received. It’s very rough chemotherapy. I also got intrathecal chemotherapy to prevent the lymphoma from going to my brain.

When I was confirmed to be in remission, they went ahead and did the stem cell transplant. They harvest stem cells and oblate your bone marrow using the strongest chemo possible then give you your marrow back.

It’s really a rescue. You have no stem cells left. They give you your marrow then you have to wait for your marrow to come back.

The biggest risk is infection. I got called septic shock and was very, very sick in the intensive care unit on medicines and pressors.

When I survived that, because my case was slightly unusual, it was decided among several institutions that I get radiation, which was really horrible. Two thumbs down, don’t recommend it, but I’m still here.

I was very, very sick. I couldn’t eat solid food. I dropped from a BMI of 22 down to about 15 or 14. It was quite difficult. I was actually trying to work. It wasn’t great, but you do what you have to do to survive. I did get great care so my doctors were fantastic. It’s just I had some complications.

Robyn’s 2nd DLBCL relapse

Robyn: I was in remission for nine months after the autologous stem cell transplant when the lymphoma came back. This time, it came back even more aggressively. Not only was it in my neck, it was underneath my armpit and in my groin.

I had no match for an allogeneic transplant — no one was even close. The doctors were very shocked. But I had already decided I did not want to go through that again.

I researched on ClinicalTrials.gov on my own. We started looking at other options. I heard about T-cell therapies. They talked about killer T cells and CAR T. It had been in the news in 2015 or ’16.

I started looking into that and that’s how I ended up going into a clinical trial. I’m very, very grateful I did. It was a phase 2 trial. It was definitely a leap of faith, but I just had a feeling it was the right thing for me.

I was an excellent candidate because I was in really, really good health except for the lymphoma. For a clinical trial, this is perfect because I had no comorbidities. That way the doctors could actually figure out if this was going to really work without something else that would interfere with the procedure.

Stephanie: ClinicalTrials.gov is a great resource. It is not the easiest to navigate, especially for a layperson so that is where the LLS’ Clinical Trial Support Center is so wonderful. Resources like that help people really navigate what’s out there.

What is a clinical trial?

Stephanie: When we talk about clinical trials, the research is happening to hopefully help provide more options for people.

A lot of patients have talked to me about efficacy or how successful it is at saving your life or increasing your life span and safety, which is quality of life and side effects. I want to live longer, but how is my quality of life going to look?

Dr. Brody, you’ve been involved with so many clinical trials. What is a clinical trial?

Dr. Brody: We should take Dr. Stacy-Humphries’ example of this. Robyn got that in 2016. There were no FDA-approved CAR T cells in 2016. They got approved in 2017.

Clinical trials are lifesavers. They are an opportunity to get access to a thing that is not yet FDA approved or sometimes things are FDA approved but a newer version or a better version or a combination.

In Robyn’s case, that was the only way to get access to CAR T cells, which years later, we realize are in many ways superior to autologous transplant and RICE. Not in every setting but in some settings, blatantly superior.

Clinical trials are carefully regulated opportunities to get access to medicines or combinations of medicines that are just not yet FDA-approved. This is a preview of future medicine. We don’t want to oversell it because not every clinical trial is successful.

We can’t ever do a trial unless we get all of these things blessed by many different groups, institutional ethical boards, local ethical boards, and the FDA. It is a way of getting access to things that are not yet FDA approved or not yet FDA approved in that combination or in that specific way.

Lymphoma is the fifth most common cancer in America. Pretty common but not as common as other ones like breast cancer. We have more medicines for lymphoma because we’ve been lucky to have more successful clinical trials and more rapid progress.

Researching clinical trials

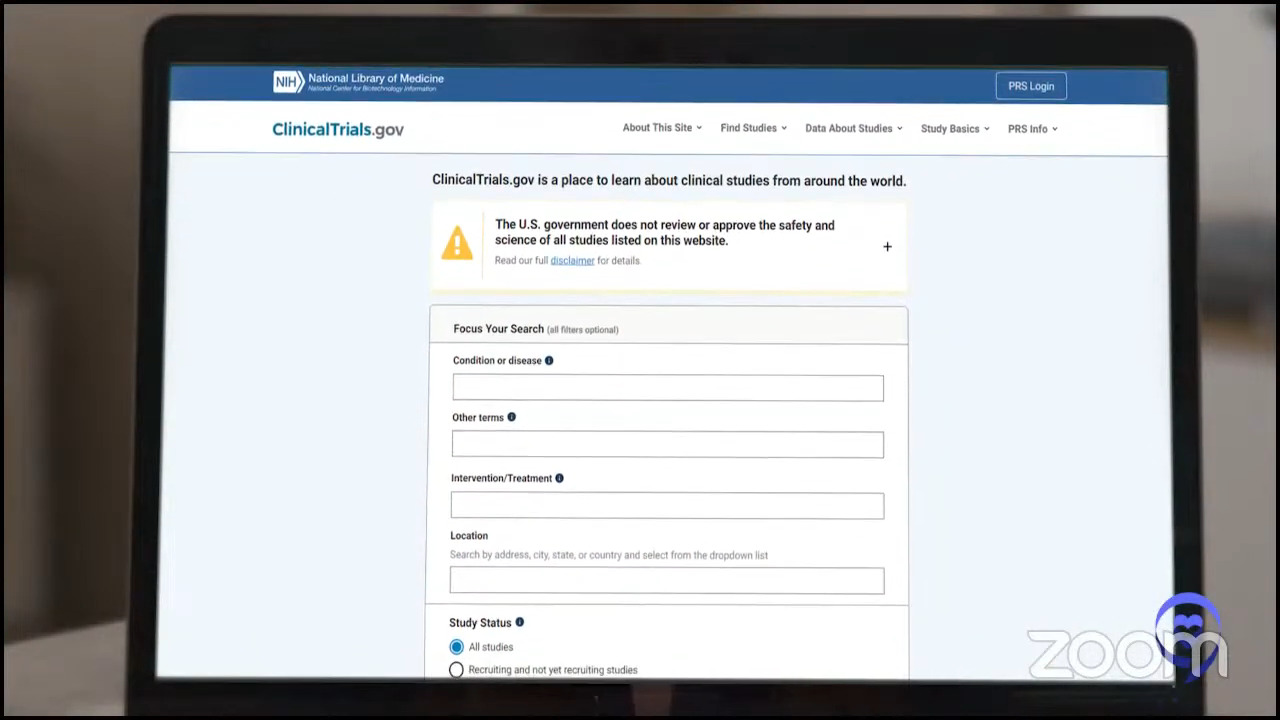

Dr. Brody: The great thing about clinical trials is the tough thing about them: finding which one is where and at what time. ClinicalTrials.gov is the same tool we use, but it’s not super user-friendly. You can look at it and you might get the answer. At the very least, it might guide you to who to call.

There is no one best way to find out what is the right clinical trial for me. Even if you ask your doctor, they know about some, but it’s hard to know about every single trial in America at any given moment because they change even from month to month.

Stephanie: Crissy, how can someone look up what clinical trials are out there on their own if that’s the direction they’d like to go in?

Crissy: ClinicalTrials.gov houses every cancer clinical trial and general treatment clinical trials in the United States and some outside of the United States as well. Patients can go on there and look up information about studies pertinent to their case if they’re interested.

I will give a fair warning. In my previous job, on at least a weekly basis, I had to help hematologists in the navigation of that database. These were really bright physicians and physicians who were the primary investigator on many of these trials and they had a hard time navigating the database.

I tell patients to say don’t get down on yourself. If you looked at that database and it was overwhelming, that’s where we come in. We have a database that sits on top of ClinicalTrials.gov and has all the information that it has. It allows our nurses to update and augment that information in real time so that it’s as updated as possible and has additional logistical information so that we can best communicate the information to patients.

Additionally, most large cancer centers or NCI-designated centers have a page on their website that has all the clinical trials that they have at their site. If a patient is specifically interested in a certain institution in the US, they can likely go to their page and look at the clinical trials that they have.

It’s generally going to link them to ClinicalTrials.gov where they can look at more information about the trial, but most institutions have really good databases on their own that talk about the clinical trials that they have at their site.

Misconceptions about clinical trials

Stephanie: Crissy, you’re on the phone a lot with patients and their family members answering questions about clinical trials. What are the top questions that you’re getting and some of the misconceptions that you’re hearing about clinical trials?

Misconception #1: Getting a placebo

Crissy: One of the biggest misconceptions that I hear from patients almost daily is that they’re worried about participating in a clinical trial because what if they get the placebo part of the trial?

In the United States, placebos are very rarely used in clinical trials. When they are used, they’re not used alone. A patient with cancer would never get just a placebo and not some type of effective treatment. The way that a placebo would be used in a clinical trial would be in addition to something that is proven to already be effective.

A really simple example that I give patients using CAR T as an example is if they wanted to study a drug in addition to CAR T that will make CAR T more effective or have less toxicity.

The way that a placebo would be used in that setting would be if you had 100 patients all getting CAR T as the standard of care and 50 of the patients get CAR T and then they get a placebo and then the other 50 patients get CAR T and a drug that’s being studied to see if it makes CAR T more effective or less toxic.

Every patient in the clinical trial is still getting the minimum standard of care. Some patients are getting something to see if it makes it more effective or potentially less toxic and the other patients are getting a placebo.

Misconception #2: Clinical trial is free

Crissy: Another big misconception about clinical trials is that everything on a clinical trial is free or that if a patient doesn’t have insurance, they can participate in a clinical trial to get a drug for free. Unfortunately, while I wish that that was true, it’s not.

There are three buckets of costs that we describe to patients.

Bucket number one is things that are free, things that the patient is not responsible for, and their insurance is not billed for and those are things that are investigational. The study drug that’s being used in a clinical trial? Not billed to insurance. Any follow-up or monitoring specific to the study drug or needed just for the clinical trial? Covered by the sponsor of the trial, not billed to insurance.

The second bucket is things that are billed to the patient’s insurance and those are things that are routine, standard of care. If someone has lymphoma, they’re going to be seen by their physician routinely. Their labs are going to be monitored. They may need to be hospitalized for treatment or symptoms. Those are all billed to insurance because even if a patient wasn’t participating in a clinical trial, they would still be having those physician visits and having their labs checked routinely.

The third bucket is things that come out of a patient’s pocket like the general copays that you would have and travel and lodging to a site. If you needed to travel far away from home to participate in a study, that would be considered out-of-pocket for a patient.

Misconception #3: Clinical trial as last resort

Crissy: The other misconception that I hear quite frequently is that patients think that they can only participate in a clinical trial if they’ve exhausted all of their treatment options and that could not be further from the truth.

There are clinical trials for patients in every step of their diagnosis — from the time that they’re first diagnosed, all the way through having failed multiple lines of prior therapy. There’s a clinical trial for most patients at every stage of their treatment.

This could be standard of care, front-line treatment for a patient with another added drug to see if it makes it more effective. It could be things like studying CAR T in the front-line setting where half of the patients get front-line treatment like R-CHOP and half of the patients get CAR T to see if CAR T is more effective in front-line treatment. Then every step beyond that, including long-term monitoring for patients who are in remission.

What is CAR T-cell therapy?

Stephanie: We’d like to delve into CAR T a little bit more. We have been getting a lot of patient questions.

Dr. Brody, can you give us a general description of CAR T-cell therapy? What is it? What does it entail?

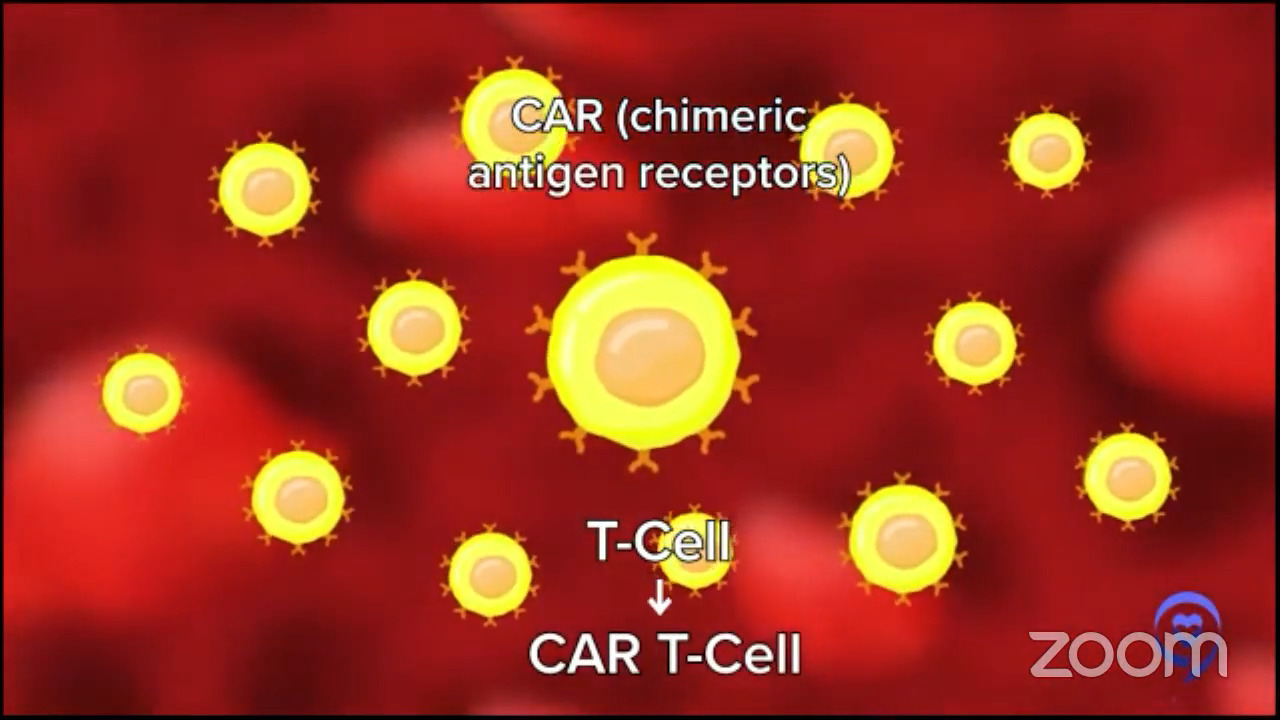

Dr. Brody: When I describe CAR T cells to my patients, they think I’m kidding. It sounds like science fiction, but it’s a real thing. They think, “Oh, what decade? When will that be here?” It’s already here.

CAR T-cell is a combination of gene therapy and immune therapy. We take out some of a patient’s immune cells, send them somewhere where they turn them from normal healthy T cells, and insert this new gene called CAR, a chimeric antigen receptor. Now we call it CAR T cells.

They ship the CAR T cells back to you. The patients have to get some chemotherapy before the CAR T cells are reinfused. We say we give that to make room for the new cells to come in. It’s a bit of a metaphor, but it’s conceptually fair.

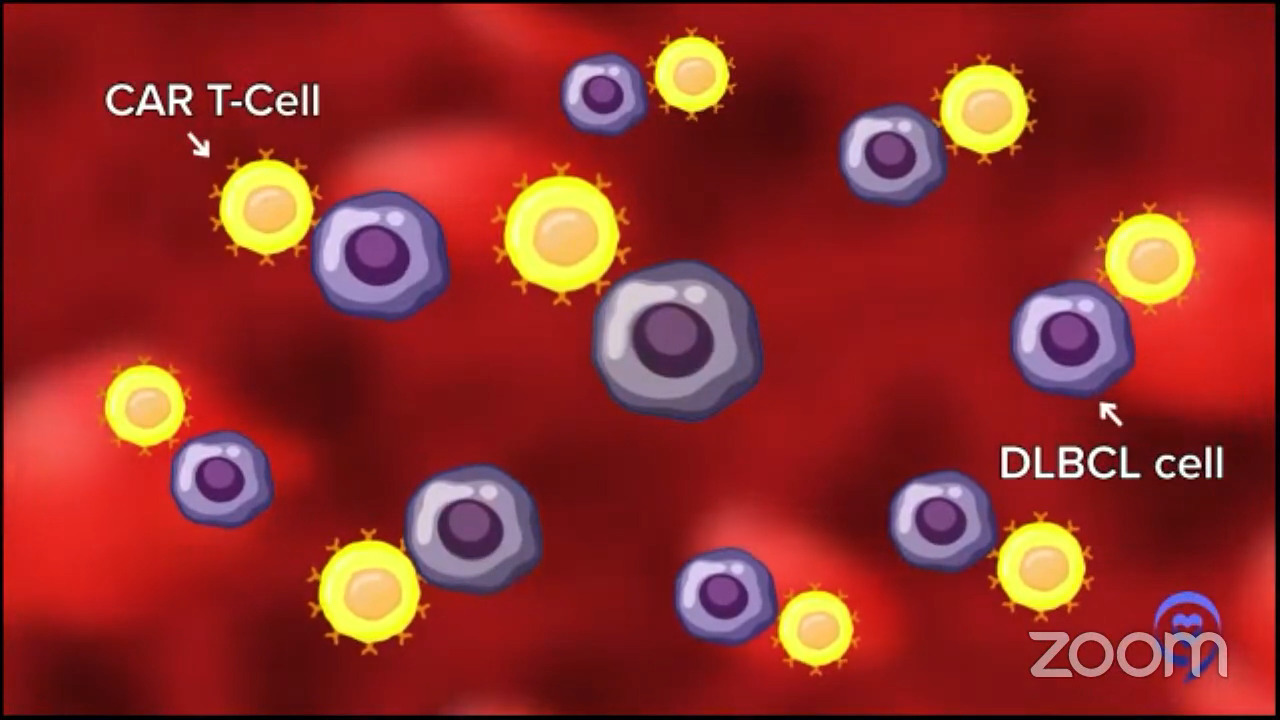

The gene that we put in, CAR, helps those T cells to go to your diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and eliminate it more potently than any other single therapy that we’ve ever developed. Close to some other immunotherapies now, but it’s quite amazing.

They don’t do it perfectly and they don’t do it for 100% of people, but they induce remissions in a good majority of people. Depending on the setting, they may cure 35, 40, or maybe even 50%, but we usually say about 40% of patients. Again, it depends on what’s happened to that patient before and some other things about the patient.

For Dr. Stacy-Humphries, we used to call that an incurable setting — third-line, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma — and now we’re curing 40% or more of those patients. It’s miraculous and it’s not science fiction. It’s a real thing.

Robyn’s CAR T-cell therapy experience

Stephanie: Robyn, you went through this. You’re a physician so you have, I think, more of a know-how of navigating ClinicalTrials.gov or understanding what’s in the pipeline. How did you determine that this was what you wanted to do? You mentioned it was a leap of faith. Who brought it up? What was the experience like when you actually went through CAR T?

Robyn: I decided that I want to do CAR T because I didn’t have an allogeneic match. I could have had a haploidentical transplant, which is a half-match with my son. I didn’t do well with the autologous transplant so I didn’t think I was going to do well or I may not have survived an allogeneic transplant and I may not have had a normal life. I wanted to have that quality of life.

I’d read about CAR T in some scientific articles. I just Googled this. Nobody really told me anything. I just thought this made sense because right now, the basis of cancer therapy is you either cut it, you burn it, or you poison it. Taking your own immune cells is actually much nicer. It’s lovely as compared to the other ones, even though it has side effects.

When I researched clinical trials, I didn’t have that much of an insight. I just put in my diagnosis. I found all of the trials and we emailed every single investigator.

The reason I ended up in the trial was it was the only opening that existed. We looked all over the world. I was really ready to sell the house and move wherever. We were lucky to get one about nine hours away.

Fast forward, I signed up for CAR T. I’m the second person at this huge hospital who gets the treatment. When they took my T cells out, they gave me one chemotherapy agent, bendamustine — some people get FluCy — and had the CAR T cells infused. The infusion took about five minutes. Everyone in the room clapped and just left so it was very anticlimactic.

In my case, they started working very quickly. By the time I came in, I had a lot of lymph nodes and within 24 hours, they started melting. Within seven days, all my palpable lymph nodes were gone.

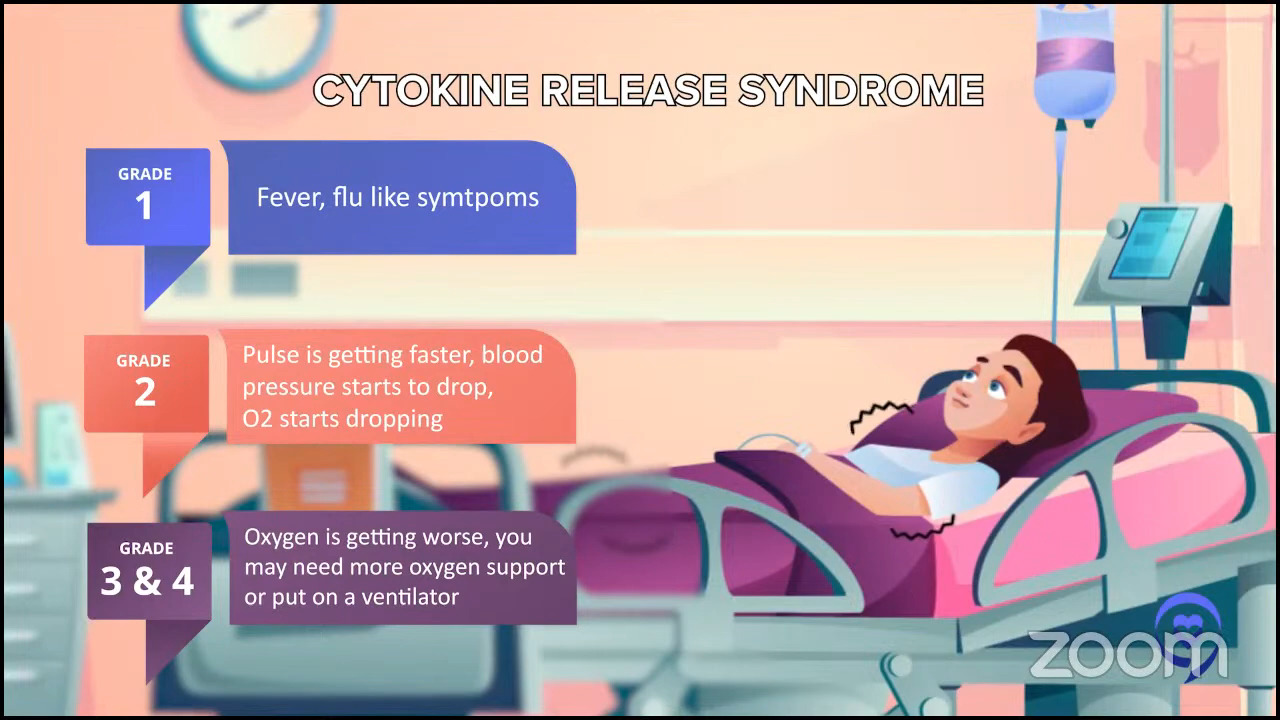

I developed cytokine release syndrome. In my case, it was a fever and low blood pressure. Most people feel really lousy, like the worst case of flu ever. I was hospitalized for three days from days 5 to 8. Other than that, I was in a rental condo and stayed at the hospital for a month. I didn’t feel great, but I didn’t feel awful.

Amazingly, I was able to go back to work four weeks later, only working two days a week, which is unusual. I did extremely well and I would say that that’s relatively unusual. I know a lot of people now who had CAR T who were working two weeks after.

Dr. Brody: After the stem cell transplant, how long were you out of work? Just for comparison.

Robyn: I was out of work for three months and when I went back to work, I was not able to eat solid food. I lived off smoothies. It was terrible.

Stephanie: What a comparison. You also said you were young and otherwise healthy except for the lymphoma so all these things may factor into a response.

Pros & cons of CAR T-cell therapy

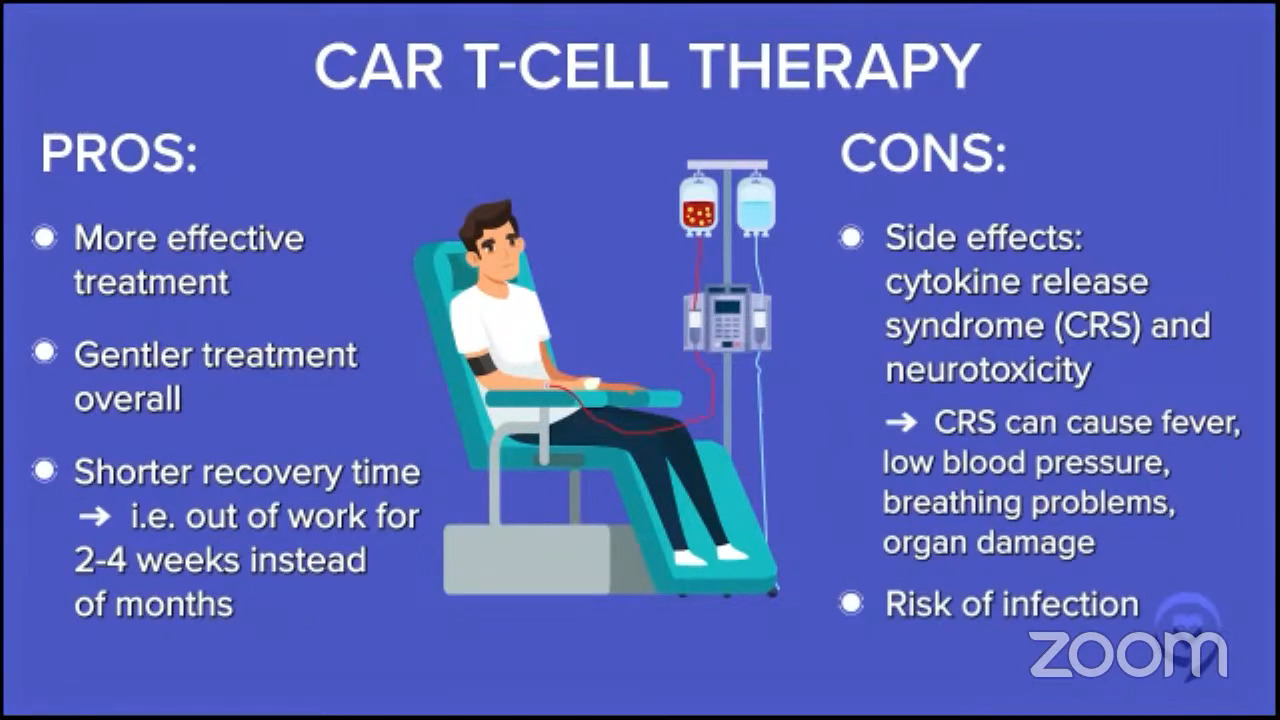

Stephanie: Patient Gil R. asks, “What are the pros and cons of CAR T-cell therapy and what is its duration?” Dr. Brody, I think you can answer this question in several ways, but I think in talking about pros and cons, people want to compare. What are the side effects? In terms of duration, how long is the therapy itself and how long is the expected duration of response?

Dr. Brody: Pros and cons, very broadly.

Pro, if you compared it to what Dr. Stacy-Humphries described as the old standard before that, the chemo and stem cell transplant, CAR T cell therapy is both more effective, especially for some patients, and gentler. Robyn was out of work for 2 to 4 weeks, whereas after the transplant she was out of work for months and only on smoothies.

When you ask doctors about efficacy, we can give you numbers. When you ask about side effects, we describe them in more nebulous, vague ways because there are so many numbers you could give.

A great metric is how long were you out of work or unable to do the things you do. If you’re retired but you garden every day, how many weeks or months until you are gardening again? Those are great examples.

Let’s acknowledge the cons as well and Robyn pointed out one. Some of the side effects and the most common and one of the scariest ones is CRS, cytokine release syndrome.

It’s basically like having an infection, but there’s no infection there. You have fevers and sometimes dangerously low blood pressure. Even though Robyn was only hospitalized for a few days, the more common thing nowadays is folks are hospitalized for sometimes a couple of weeks on average.

Sometimes, it’s a boring hospitalization, which is the best kind of hospitalization, just to watch for that side effect to see if it occurs. Sometimes folks have to go to the intensive care unit just to treat that low blood pressure and fever. That is one of the biggest side effects.

One other scary side effect is called ICANS (immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome) but we just call it neurotoxicity or encephalopathy. It means there’s a horrible problem with the brain and this side effect manifests in many different ways like hallucinations and loss of consciousness.

These things sound very scary so I should preface it by saying there’s a very defined time course to these side effects. They almost always happen within the first couple of weeks. There are a couple of rare exceptions of it happening on the third week, but they never happen two months later. Both CRS and neurotoxicity are scary side effects. They’re time-limited for the majority of people, but they’re a serious big deal.

Some patients have a higher risk of getting those side effects, like patients who are older or less healthy and patients who have greater tumor bulk. Patients with enough lymphoma have more of those side effects than patients with just a small amount of lymphoma when they go into CAR T therapy.

This therapy has a greater track record of keeping people in remission for years and years. We have some newer therapies that are as promising, but they don’t have the years and years of track record because they’re newer therapies.

These side effects are not nothing. If you were an 80-year-old patient with a bulky tumor, these cons are a serious thing and we have to start thinking about other alternatives for those kinds of patients.

What are bispecific antibodies?

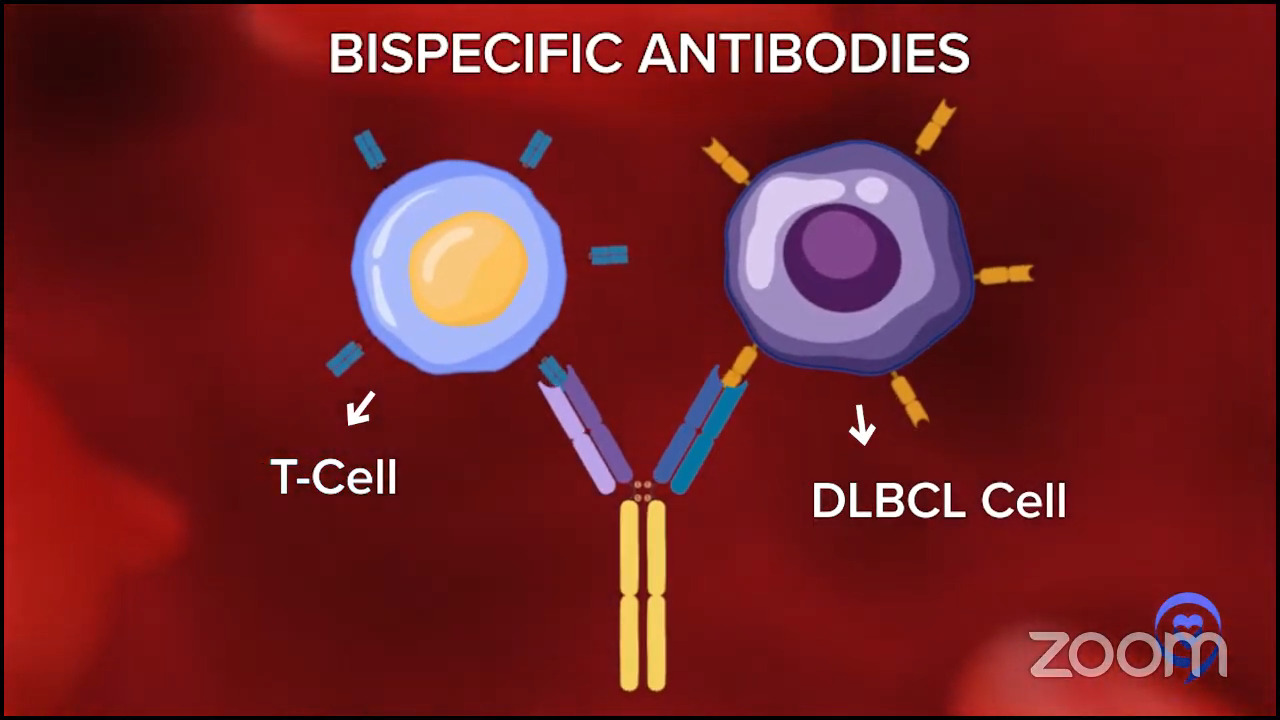

Stephanie: Dr. Brody, let’s talk about bispecific antibodies. Some have described it very simplistically as an off-the-shelf CAR T option.

Dr. Brody: This is, I would say, the most exciting and transformational thing in lymphoma and DLBCL, certainly in the last couple of years. Maybe you might argue ever because my belief is their total impact in the next few years is going to be unparalleled.

Antibodies are magical little molecules, big long proteins that bind very specifically to one thing. We make antibodies against COVID after we get a vaccine or get COVID.

A company can make antibodies against certain targets on lymphoma cells. Rituximab is an antibody against lymphoma, but it just binds lymphoma.

Some brilliant pioneers from a few groups developed bispecific antibodies. They bind to lymphoma cells and one of your T cells.

Some people use the Lady and the Tramp with one spaghetti noodle metaphor. If you haven’t seen the movie, the spaghetti noodle brings them together except instead of the kiss between the Lady and the Tramp, this is the kiss of death because the T cell kills the lymphoma cell and kills it pretty well.

In a way, it’s sort of an off-the-shelf version of a T-cell therapy, like the CAR T cell. It’s very cool that CAR T-cell therapy is individualized. I send my T cells in, they send me back my CAR T cells. Logistically and practically, it’s very difficult and it takes a lot of time.

How much time it takes is a bit variable. It could take 2 or 3 weeks to make the product, but sometimes it takes a couple more weeks just to plan the whole thing out. Sometimes it takes more weeks just to get to see the doctor to plan that so there can be real delays there.

Whereas with these bispecific antibodies, you just inject it right into the patient. No delay there so they are in some ways a lot easier because they are off the shelf. You don’t have to make it for each person.

Efficacy of bispecific antibodies

Dr. Brody: The efficacy has been overall awesome. They are not perfect, but they are putting a big proportion of patients into complete remission and some of those patients are staying in complete remission for years so that’s fantastic. Maybe the numbers are a little less amazing than CAR T cells in efficacy, but they’re also a lot easier.

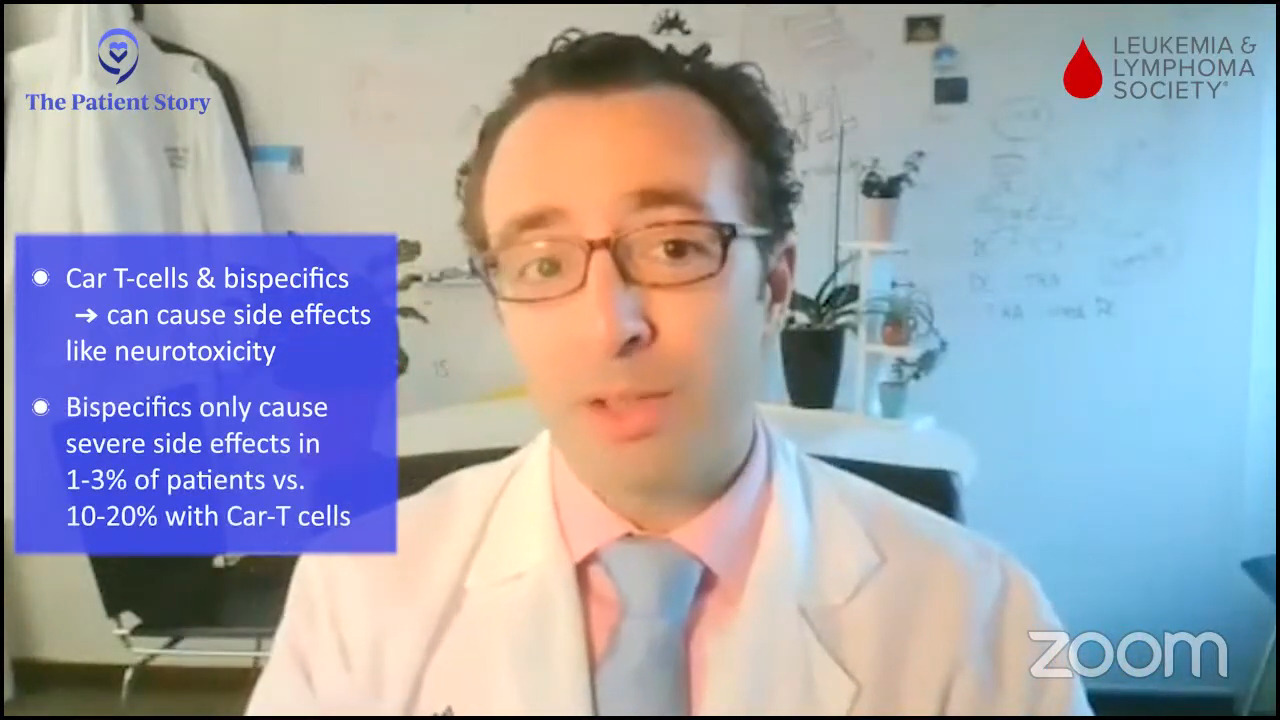

Side effects of bispecific antibodies

Dr. Brody: Overall, possible side effects are a lot gentler. Those CAR T cells were causing CRS or neurotoxicity in maybe 10 and 20% of patients, whereas these bispecifics caused bad side effects in maybe 1 to 3% of patients.

It opens up a lot of opportunities. A patient that was not eligible for CAR T, because it would have been too scary, could be eligible for bispecifics.

Access to bispecific antibodies

Dr. Brody: CAR T cells are available at a limited number of centers. That can be tricky because you’re not just going there for one day to get the therapy; you’re there for a while, as Robyn was saying.

Bispecifics were just FDA-approved so they may not be available everywhere today. We don’t want to oversell that, but they can be available everywhere and they’re now available at most major centers.

Eligibility for bispecific antibodies

Stephanie: Epcoritamab and glofitamab are newer and newly approved.

How would someone know what questions to ask whether they’re a good candidate for bispecifics or which option to go for? As we know, it was approved for later lines of treatment and even after approval, they’re still in clinical trial because everyone likes to try and move it up earlier in lines of treatment.

Dr. Brody: Very exciting. These two medicines were just FDA-approved. There was one other that was approved for follicular lymphoma at the end of 2022, which was mosunetuzumab.

There are a lot of these getting studied and approved now. There will be several more approved as sort of a plan C, third-line therapy when Plan A or Plan B don’t work well enough.

If a patient asks, “Is this the right therapy for me?” Tough and detailed question, but the first thing you want to make sure of is that the doctor that you are working with is familiar with the option.

Even though they are available anywhere, there are a lot of new cancer medicines coming out every month and year. This is very tough, especially for community oncologists who take care of every kind of cancer. It would be impossible for them to be super familiar with every new medicine for every type of cancer.

It is not that every patient with lymphoma needs to be seen by a lymphoma specialist, but once Plans A and B have failed, this is not a great situation.

Let’s just be simple about it. Bluntly, it is worth the schlep to go and see a specialist who does nothing but take care of lymphoma patients. They are familiar with these medicines and it would be hard for most community oncologists to be familiar with them.

Community oncologists will be familiar with these medicines over the next couple of years, but they may not be today and they may not have access to administer them because there can be complexity in getting these medicines started in a new practice.

You need to make sure that you’re speaking with a doctor that has comfort around this. A lot of times, community oncologists are vaguely aware of it so they’ll call their local buddy who’s a specialist and say, “You tell me. Should I send this patient to you?”

But as you heard from Robyn, sometimes patients end up advocating for themselves. I’d like to say that there’s a better way, but that does happen. The function of The Patient Story, the LLS, and other patient advocacy groups is to try to be an intermediary so patients don’t have to advocate for themselves.

But if a patient is asking if bispecific antibodies are right for them, there’s a good chance the answer is yes so you should at least be talking to someone that has experience with these.

Choosing among treatment options

Stephanie: When there are different options and they’re new, how do you make a decision on which option to put a patient on?

Dr. Brody: Although these medicines are newly approved, we’ve been using these medicines for three years, give or take, so we have a lot of familiarity with them. Maybe we didn’t predict this, but epcoritamab and glofitamab are more similar than different.

For example, the complete remission rate for both of them was exactly 39%. What are the chances of that? The high-grade bad side effects were about 3% with both of those medicines.

There are a few nuanced differences. Epcoritamab is given subcutaneously whereas the glofitamab is given intravenously. It’s a little difference, not a huge, big deal.

The timing is a bit different. Epcoritamab has more visits and they might go on for longer. Glofitamab has fewer visits and is designed to be stopped after about nine months.

It doesn’t give you an answer to which one is better. We ultimately make a decision for each patient, but they’re pretty similar overall.

Stephanie: Let’s bring back CAR T. There are different approvals for different groups of people and there has to be that personal conversation between a patient and the provider to understand the best option.

Generally speaking, if you’re comparing CAR T-cell therapy versus bispecifics in terms of limitations and challenges, what would that summary look like for our patient audience?

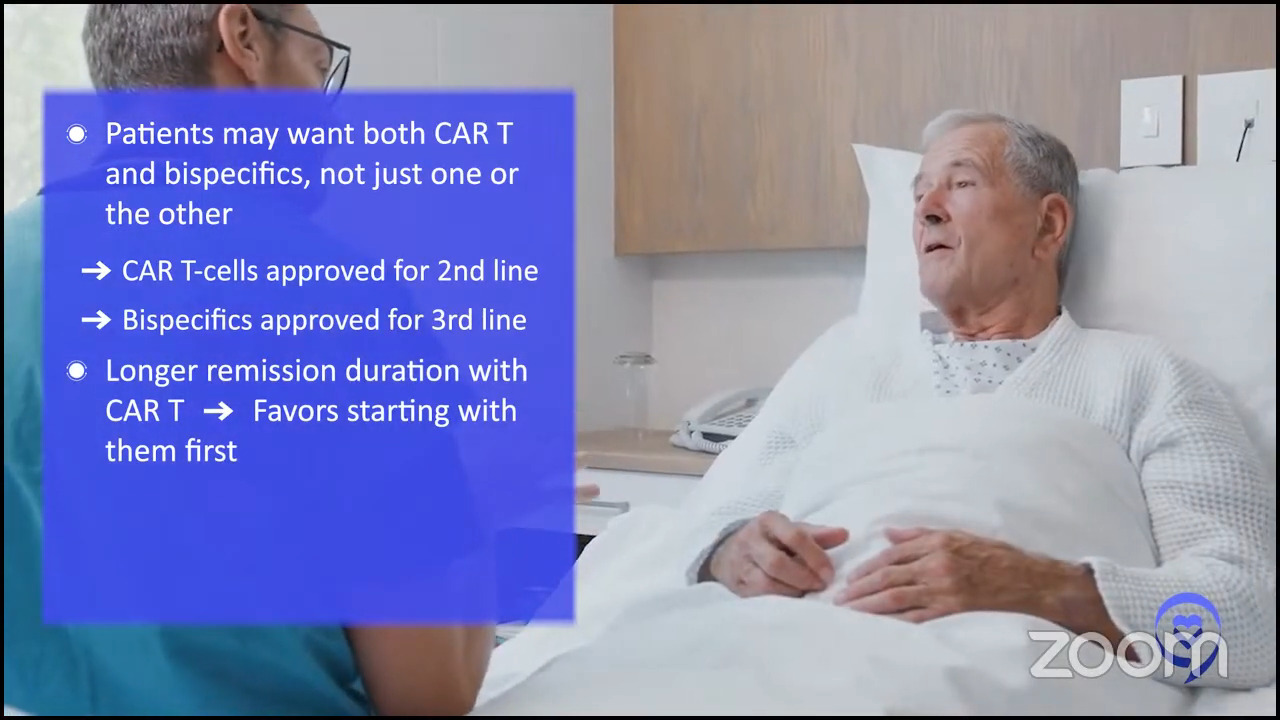

Dr. Brody: I’m going to change the question slightly. The question is always which one’s better, CAR T or bispecifics? But that’s not actually the question people really care about because, unfortunately, neither of these cure 100% of people. As the patient, you want to get access to both, not A or B. You might want both this and that or that and then this.

The best question is: what’s the best order to give them? If you were going to get both, would you rather get CAR T and then bispecifics or bispecifics and then CAR T?

Sometimes it’s a moot point because CAR T is approved as a second-line therapy for some patients and so far, bispecifics are approved as a third-line therapy for patients. In some cases, you don’t have to make a choice because this one’s available and that one’s not — that’s going to change a lot in the next couple of years.

I have to give you my honest belief about this. CAR T has one thing that is definitely better — they have a longer, more tried, and true precedent of keeping people like Dr. Stacy-Humphries in remission for a long time. We say “curing” patients. It’s been proven for longer so you might want the most proven thing and CAR T is that.

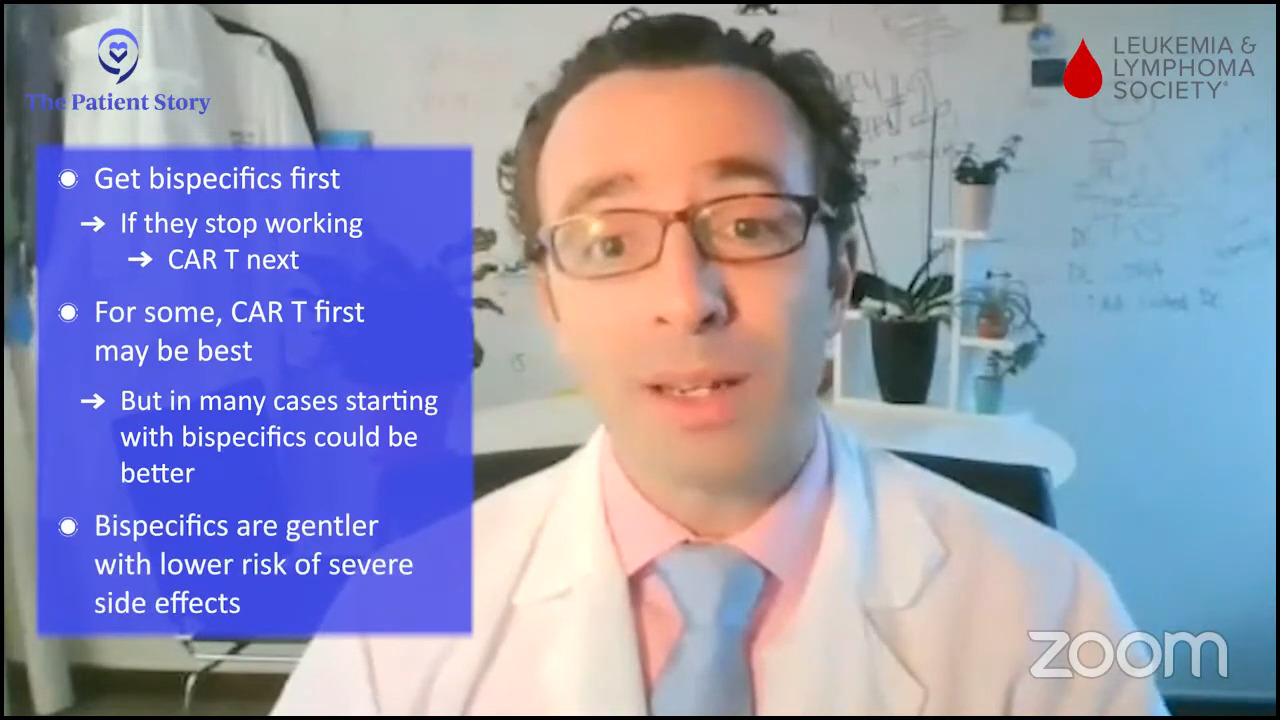

It still fails for a majority of patients depending on the setting. If it cures 40%, that means there’s 60% that still we need to do better for.

If you really want to get both, if you were to get CAR T and it failed, you might not be able to get bispecifics because the chemo you get right before CAR T might not make the bispecifics work well. It wipes out many of your own immune cells so giving them in that order may not be great. Giving CAR T and bispecifics right afterward may not be a good option.

If you give bispecifics first and you’re in remission, great! You don’t need something else. But if they stop working, then you could get CAR T afterward. We’ve done that many times now.

It’s not which one is better; it’s what’s the best order to get them if you’re going to get both. For some situations, it’s going to be CAR T. There are a lot of situations for which you might want to get bispecifics first also because it is gentler and the risk of those bad side effects is lower. Some people find that appealing as well.

There’s no right answer, but I’m giving you a little bit of my prejudicial belief about what might be the best order.

Stephanie: Sequencing is a huge question. If bispecifics are approved for earlier lines, it will actually be a consideration for people.

Bispecific antibodies in the community setting

All things considered, part of the question, too, was accessibility. There’s this idea that if it’s off the shelf, more people will have access to it. Do you see any challenges there, even in the community setting, with bispecifics? What are some of the solutions?

Dr. Brody: I was explaining how much easier and gentler bispecifics are compared to CAR T cells. Robyn actually had a good experience, but she did have cytokine release syndrome and people do have to get hospitalized usually for that. Sometimes, for only a few days but most commonly for a couple of weeks.

Bispecifics are gentler. The risk of high-grade side effects is less, but there is still a 3% risk.

As of today, folks getting bispecifics still have to get hospitalized for at least one day just to watch them as they get the first dose of that new medicine. That’s not so bad. One day is less than a couple of weeks, but it’s not nothing.

Some community oncologists may have difficulty getting that hospital bed lined up. It sounds like a simple thing, but practically, it can still be difficult. We are trying to overcome that obstacle.

There’s an ongoing clinical trial of epcoritamab trying to give it at a gentler step-up dosing so patients don’t even have to get that one-day hospitalization. There’s a good chance that the trial will be successful so we’re looking forward to that.

But as of now, even getting a one-day hospitalization might make this an obstacle to getting this with your local oncologist.

Bispecific antibodies as a treatment option

Stephanie: Robyn, you lead this huge group online in the CAR T-cell therapy space. I’m curious if you’ve started to get questions about bispecifics. What is your take on where you think bispecifics might fill a gap or be a good option for folks?

Robyn: Every patient is unique. In community hospitals, most oncologists are very overwhelmed with trying to take care of more of the “bread and butter” type of therapy so I really don’t see bispecifics going into the community hospitals anytime soon, at least in the more rural areas. It’s going to have to be in a city center and often on a transplant unit.

For bispecifics and CAR T, I see them as very similar. On the CAR T site, we do have people who fail. About 40% have a long-term remission rate then there’s everyone else.

Most people after the second or third round should see a lymphoma specialist then they’ll have to decide what they would rather have or what’s best for them. With the new bispecifics, it changes the whole gamut.

Most of the people on the site are actually CAR T, but then when people fail, there’s another site that deals with relapses from CAR T. A lot of those patients go on to bispecifics and they’ve had some real success with that.

Everything’s very early. Patients need to be their own advocates and have to be honest. As much as they would like to stay in their rural hometown or be with their family doctor, if you have something serious like this, you really have to travel.

New DLBCL clinical trials

Stephanie: Dr. Brody, there are different clinical trials that are happening that we haven’t covered, but as great as these developments are, everything has some limitations. There are always more clinical trials to try and solve those problems. If you could talk a little bit about some of the newer clinical trials that are happening and what problems they’re trying to solve, especially in the bispecific space.

Dr. Brody: Rituximab targets CD20 and these bispecifics so far also target CD20, a marker that’s on lymphoma cells. The CAR T cells target another thing on lymphoma cells called CD19. There are a few of those markers that you could maybe target.

If you target something on the surface of lymphoma cells, if there were a couple of lymphoma cells that didn’t have CD20 or CD19 on them, those won’t get targeted by the therapy and would grow out, escape, and cause the relapse.

We call this antigen escape when that targeted antigen is lost by the cancer cells and then those cancer cells grow back. This is the main limitation of both CAR T cells and bispecific antibodies so there are a lot of ways we could try to solve this problem.

One of the simplest ones is to go after different targets. We now have bispecifics targeting another antigen on lymphoma cells called CD22. The numbers don’t even matter that much. It’s just going after something that wasn’t on the cancer cell initially so they’re still there after the first bispecific.

We have things beyond bispecifics called trispecifics, which are going after two things on the lymphoma cell and then getting the T cell. For example, going after CD20 and CD79 and then grabbing the T cell as well, the effector that’s going to give the kiss of death to that lymphoma cell.

These are good ways to prevent the antigen escape problem. We’re starting some of those trials now. We’ve been treating a lot of people and seeing patients going into complete remission so maybe these will be even better than the already standard of care that was the cutting edge just a month ago, the new bispecific antibodies.

Maybe we’ll have trispecific antibodies as the new standard of care to prevent that problem. Some limitations but some solutions coming up for those limitations so pretty encouraging.

Different phases of clinical trials

Stephanie: Crissy, a lot of your patients get worried when they hear that one of the studies is in phase 1.

Crissy: I hear that a lot. Patients call me and say, “I only want to participate in a later phase trial like a phase 3 or a phase 4.” There’s a long conversation that goes into explaining to patients that a drug doesn’t go through all four phases of a clinical trial before it’s approved.

Phase 1 clinical trial

Crissy: A phase 1 clinical trial is a dose-finding clinical trial where they find the proper dose and establish safety. How that’s done is in a step-up fashion. Generally, there are a couple of dose levels that are identified and they enroll a small number of patients into each dose level.

They start with dose level one and give that dose to around three patients. They assess those patients and monitor for toxicity for a set number of days, usually more than a month. If no unwanted toxicity is seen, they move up to the next dose level and beyond in that same fashion.

They move up to dose level two, give that to a small number of patients, and assess them for toxicity. If there are no unwanted toxicities, they move up to the next dose level. Same thing. A small number of patients monitor them for a period of time.

Phase 2 clinical trial

Crissy: Once they’ve reached either the maximum dose in the trial or toxicity, that dose level is identified and moved into phase 2. They give the dose level that was identified in phase 1 to a large number of patients in phase 2, usually around 100 patients. That’s when they’re assessing for effectiveness.

If you look at the way a clinical trial is listed on ClinicalTrials.gov, many clinical trials are listed as phase 1/2 and that design that I described is being done on the same clinical trial.

Sometimes, after phase 2 is complete, if the data is robust enough, they’ll submit to the FDA for approval at that point. Sometimes clinical drugs only go through phase 1 and phase 2 before being submitted to the FDA. However, a phase 2 clinical trial is considered the gold standard before being submitted to the FDA for approval.

Phase 3 clinical trial

Crissy: In a phase 3 clinical trial, drugs are being compared to the standard of care. A really good example of this is after CAR T was very first approved, it was only approved for patients who had lymphoma and had failed two or more lines of therapy. The FDA approved it for patients who had failed front-line treatment and then either salvaged with an autologous stem cell transplant or just salvage therapy alone.

A phase 3 clinical trial opened up where CAR T was compared to the standard of care second-line therapy. Half of the patients received CAR T and half of the patients received standard of care with an autologous transplant.

Phase 4 clinical trial

Crissy: A phase 4 clinical trial is long-term toxicity, side effect type of trial for drugs that are already on the market.

Low enrollment for adult clinical trials

Stephanie: This is where the LSS’s Clinical Trial Support Center can help. Can you explain more about the numbers that you’re seeing? The national enrollment for adult clinical trials is very low and the LLS is trying to get the numbers up.

Crissy: Many patients come to us having tried to look for clinical trials on their own or a doctor told them to look for clinical trials or they had a loved one who just decided to start looking for clinical trials on their own. They often come to us very overwhelmed, having tried to look at ClinicalTrials.gov or other databases for clinical trials.

You can certainly go on to ClinicalTrials.gov and look for trials yourself. What our department does is take that workload off of a patient and their families and do a personalized search for the patients that we work with.

The national average of patients that participate in clinical trials is around 3-5%. Nurse navigators in the Clinical Trial Support Center help patients identify clinical trials that they’re potentially eligible for, identify barriers that they may be facing — logistical barriers, insurance barriers, not knowing what options are available — and overcome those barriers.

Our average of patients that participate is around 22%. The patients that we work with have a higher chance of participating in clinical trials because of the work that we do to help them navigate the entire process.

On behalf of the patients that we work with who participate in a clinical trial, our nurses do more than 20 interactions with healthcare providers or the trial sponsor. Our team and LLS in general really look at that as more than 20 opportunities for a patient to fall through the cracks if they weren’t working with a nurse on our team.

Travel costs in clinical trial participation

Stephanie: Patient Joy B. asks, “Are travel costs included for clinical trials?”

Crissy: Very good question. Around a quarter of clinical trials close because they don’t reach accrual goals. They have a set goal for how many patients will participate in the trial and they don’t reach it.

One of the reasons that happens is that while clinical trials are at academic sites, patients aren’t always located near an academic site so they have to travel to participate.

A lot of work has been done over the last 5 to 10 years to overcome that barrier for patients. If they have to travel to participate in a clinical trial, how do we decrease the burden for them with that travel? And that’s been identified as financial assistance.

A lot of clinical trials will provide financial assistance to patients who participate in a trial that has to travel beyond a certain distance. Generally, it’s more than 30 or so minutes.

If a patient has to travel more than 30 or so minutes to participate in a clinical trial, I highly, highly encourage them to ask the team at the treatment site if there is financial assistance for me to participate. Oftentimes there is.

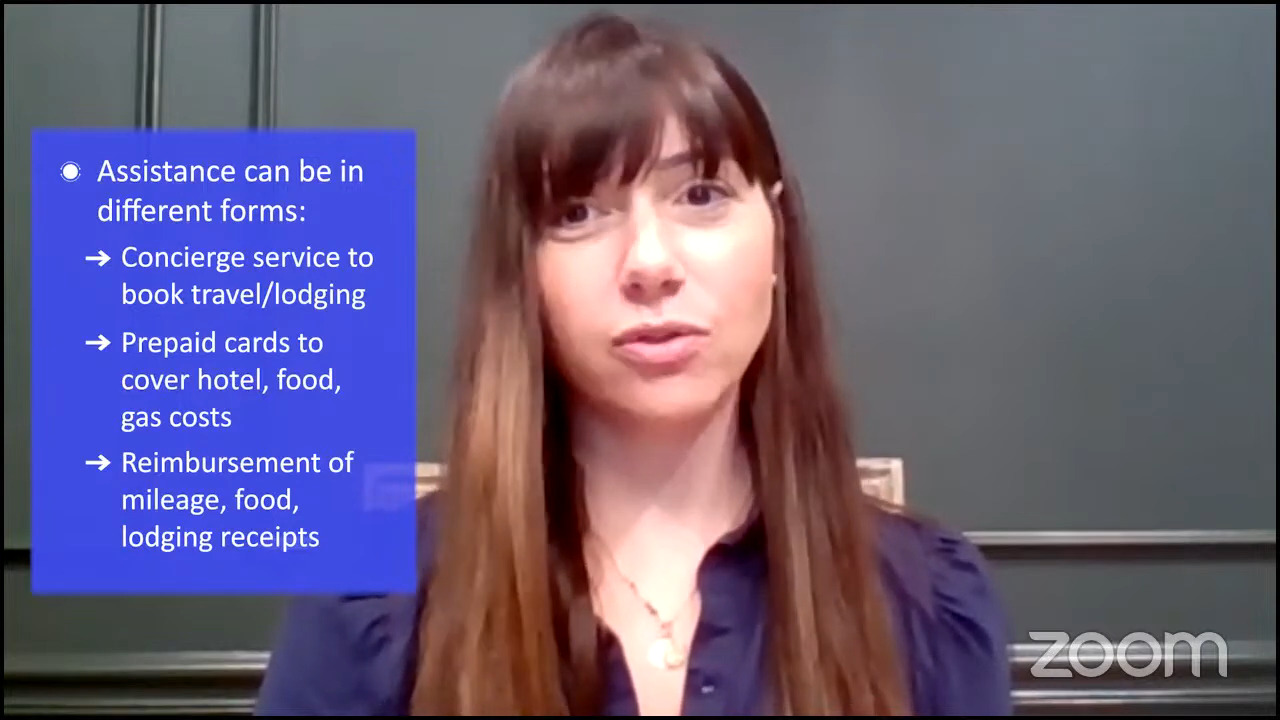

How it looks is different for every clinical trial and every site. Sometimes it is a concierge service that books patients’ travel or lodging for them. Sometimes it’s a prepaid card that helps them pay for the hotel, food, and gas.

Other times, in not-so-ideal situations, it is done on a reimbursement basis where patients submit their mileage, food receipts, and lodging receipts then they’re paid back by the company for those expenses.

There’s been a lot of advocacy from LLS and other groups to change that model. A lot of patients don’t have the money to front that. If they can’t pay for a hotel room upfront, the reimbursement model doesn’t work for them.

Additionally, The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society has copay assistance and travel assistance for patients, whether that’s to get treatment or to participate in a clinical trial.

Clinical trial paperwork

Stephanie: Robyn, you went through this process. I would love to hear about figuring out logistics, but also you had to go through excessive paperwork before the clinical trial, is that right?

Robyn: The paperwork is very intimidating for most people and even for myself. Look through the paperwork but also talk with your doctor. The paperwork always has the worst things that can possibly happen with the clinical trial, but you also need to ask your doctor, “What is the alternative that I’m getting?” A lot of times, we don’t go into that.

For example, CAR T versus allogeneic transplant. People get a little overwhelmed. Sometimes, they don’t understand that the clinical trial has some risks but even the standard therapy might even have more risks.

Ask questions. Try not to get too overwhelmed with the paperwork. Be your own advocate. Knowledge is power. Read up and be ready to go. Don’t expect all your doctors to have all the answers right off the bat. You need to be able to ask the right questions.

Crissy: If I had the time like a day or so of leeway, I would call the patient ahead of time, get their email address, and send them a copy of the consent form beforehand.

I would tell them, “Look this over with your family. Highlight, write down questions, and make a list of questions that you have about the form before coming to the site.” It’s a long form; oftentimes over 50 pages and that can be a lot in a single doctor’s visit to look over.

Bring someone with you. That can be a village. If where you’re going allows, bring people with you for that visit or have them on video call so there are more ears hearing the information and people who can remember the information.

Lastly, the really important thing is you can sign that form and say that you want to participate, but it’s not legally binding. You can leave the clinic that day and say, “You know what, I changed my mind. I don’t want to participate.” You can do that at any point in the clinical trial — a day later, a week later, months later. You’re not legally bound by any means after signing that form.

I encourage patients to stay on the trial if possible. For data capturing purposes, we need patients to stay on the study to show the effectiveness or safety of the drug so that it can potentially get to many more people.

Stephanie: I love that message of self-advocacy. What we’ve seen at The Patient Story is people get motivated when they hear other people say, “I was an advocate for myself.” It almost gives a sort of permission to speak up.

Final takeaways

Stephanie: We’d love to understand the final takeaway from each of our panelists that they’d like for audiences to walk away from. Dr. Brody, what’s your biggest message?

Dr. Brody: Patients with lymphoma are unlucky to have lymphoma but so lucky to be here today with that lymphoma. Twenty years ago, we didn’t have access to medicines that cure patients and keep them in long-term remission to go and live their lives, hopefully just like they were before.

We only have those new medicines because patients join clinical trials. Patients who join clinical trials today sometimes are getting access to the medicines of the future.

These new bispecifics that just got FDA approved, our patients were getting access to them three years ago because they did this slightly scary thing and asked, “Are there any clinical trials available?” For some of them, thank goodness, because they’re still here to tell their story today.

Stephanie: Thank you, Dr. Brody, for being a leader in the space of clinical trials. We also know what a big advocate you are for patients and their families so thank you so much.

Crissy, I know that for you, there’s something about when to talk about these options with people’s doctors, right?

Crissy: Around 90% of adult patients with cancer are treated at community sites. The bulk of clinical trials, unfortunately, are not at community sites. They’re at large academic centers.

From the time a patient is diagnosed, they may not know that there are clinical trial options available to them if they’re not at the site where a patient is being treated. Generally, physicians are going to offer patients what they have at their site.

It’s really important to talk to your doctor. Ask them from the point of diagnosis and at relapse and beyond: What are all of my options beyond the treatment that you’re offering me here? Is there something that’s potentially better or other options that I could access somewhere else?

You’re the driver of your ship and so advocate for yourself. Ask questions. From the time you’re diagnosed, ask about the treatment options that are available to you now and what if. What’s our plan B? If this treatment doesn’t work, what’s next for me?

Explore second opinions. If you’re interested, go to another site and see an expert in your disease and ask what they would recommend to you. There are no ill feelings from a healthcare provider when a patient wants to see another physician in that space and get their input.

For patients who come to me worried that they’re going to offend their doctor, you’re generally not. The grand majority of physicians are not going to be offended if you want to get a second opinion from an expert in the field.

If you are with a physician who is offended by you getting a second opinion, that isn’t a physician I would personally want. I want a physician who wants their patients to advocate for themselves to know all of their options and explore every option that’s available to them.

Stephanie: Thank you so much, Crissy, for that and for your work at the CTSC. Patients and family members find a lot of comfort for sure in having someone to lean on through what can be a very overwhelming process so thank you again.

Speaking of this process, Robyn, you are such an inspiration for people about the power of a clinical trial. We know that it might not be for everyone and it’s a very personal decision, but you have such a wonderful voice to lend when it comes to what is right about a clinical trial.

Thank you also for participating in one because that helped to further the data and the experience so that it could lead to approval. You’re proof of thriving after a trial. What would you like your message to be to our audience?

Robyn: Don’t give up hope. Make sure you ask questions. Feel free to get other opinions. Really good doctors are not insulted when you get another opinion.

I’m living a great life. I’m working. I’m traveling. I saw my youngest child get married. It’s fantastic.

I’ve been a doctor for over 30 years and I’ve taken care of a lot of patients. I’ve read hundreds of thousands of films. I’ve done thousands of biopsies. I’ve held a lot of people’s hands. I’ve counseled a lot of people. But ironically, my biggest contribution to medicine is not as a doctor, but it’s been as a patient so I’m grateful to be here.

Thanks, Stephanie, for doing this. This is fantastic. I wish I had had something like this when I was going through my experience.

Stephanie: Thank you so much, Robyn, Crissy, and Dr. Brody — incredible discussion about clinical trials in the space of DLBCL. We hope you’re able to walk away tonight knowing more and feeling more comfortable about what clinical trials are.

For FREE 1:1 support to enroll in and stay in a clinical trial, check out The Patient Story’s partner organization in the program, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and its Clinical Trial Support Center!

Here is a direct link to a form to fill out — and someone from The LLS will reach out after.