Tim Fenske, M.D., M.S.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Treatment

Dr. Tim Fenske is a hematologist-oncologist who specializes in cancers like lymphoma, leukemia, and CLL/SLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma). In this interview with The Patient Story, Dr. Fenske describes the basics of CLL and latest treatment options, including immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

- Name: Tim Fenske, M.D., M.S.

- Role: Professor, Medical Oncologist, Researcher

- Experience: ~15 years

- Hematology/Medical Oncology

- Cancer Center – Froedtert Hospital, Moorland Reserve Health Center

- Associate Professor

- Medical College of Wisconsin

- Fellowship

- Hematology/Oncology – Washington University – St. Louis, MO (2002-2005)

- Approach with patients: Education & including patient perspective

Patients who are nervous about a clinical trial typically say things like, “I don’t want to be a guinea pig.” The thing is, that’s not really the case. In most trials, you will not be the first person to have taken a drug. There are very few scenarios in which the patient would be the first.

Tim Fenske, MD, MS

Introduction & CLL Basics

Can you introduce yourself?

My name is Tim Fenske. I am a part of the faculty at the medical college at Wisconsin University in Milwaukee where I’ve been practicing for about 14 years. My practice is focused on lymphoma (Hodgkin’s, non-Hodgkin’s) and leukemia.

I came to medicine from the research side of things. I had spent several years doing lab research and became very fascinated with the immune system and the idea of bone marrow and stem cell transplants as well as immunotherapy as ways to treat cancer. That’s how I got interested in this field.

Then, after all the years of training, residency, and fellowship, I ended up as a specialist in blood cancers with my research area being more focused on clinical trials and testing new agents.

What is CLL? Is it leukemia or lymphoma?

With CLL, they actually call it CLL/SLL. That’s a way to make the distinction that it can present in different ways. There’s a leukemic presentation where there are a lot of cells in the blood, and then with SLL it’s more of a lymphoma where they have enlarged lymph nodes and not a lot of cells in the blood.

The distinction for CLL is a certain number of cells in the blood. You can have enlarged lymph nodes with CLL, but if you just have the lymph nodes and not so much the cells in the blood, that’s gonna be called SLL. The cells themselves look the same. The diseases are the same. It just has more to do with where the cells are living.

»MORE: Learn more about CLL →

What is the difference between leukemia and lymphoma?

The short answer is leukemia means you have cancer cells circulating in the blood. Lymphoma is when you tend to have the cells in lymph nodes or other organs that are part of the blood system like the spleen.

There are, of course, exceptions. You can see lymphoma show up in just about any organ. Leukemia can present as almost like tumors in the blood.

The most common scenario is that leukemia is circulating in the blood and there are detectable cancer cells in the blood. Whereas a straight lymphoma is when the cells aren’t so much detectable in the blood, but they’re in the lymph nodes.

Testing & Treatment

What determines when someone with CLL will get treatment?

In many cases you can wait. We check a lot of biomarkers and run a lot of tests on patients when they’re first diagnosed. We run chromosome tests, protein stains, mutation analyses, and things like that. Those things are useful for predicting prognosis.

Within patients with CLL, there are some who have a more aggressive form of the disease and can’t do watch and wait very long. There are others who won’t get treatment until five or 10 years after they were diagnosed.

These biomarkers are reasonably good at predicting whose disease is going to be a slow mover versus a fast mover, but they don’t actually tell us who needs treatment at that moment. These biomarkers are more for giving us an overall idea of how the disease is going to go: fast or slow.

The actual decision to treat or not treat is based on more basic things like whether or not the patient is anemic or has a low platelet count. Other symptoms might include fevers, drenching sweats, weight loss, extreme fatigue, or pain from enlarged lymph nodes.

Those kinds of things would influence a decision of whether to treat or wait.

What are some of those biomarker tests?

There’s something they do on the immunoglobulin gene called a gene mutation analysis. That’s a little confusing. The normal counterpart cells that CLL cells come from are called lymphocytes.

Those cells go through a normal maturation process as part of the immune system. In that process, there’s a normal mutation process that happens.

A cell that’s further along in the B cell development pathway will have these mutations, and a cell that’s not as far along won’t have those mutations.

It’s a way of assessing how far down the B cell development pathway that cell got before it turned into a CLL cell. It’s not a mutation that drove the cell to be cancerous. Those are different.

Immunoglobulin mutation analysis has been a good way to cluster patients. If they’re mutated, they have a better prognosis as it turns out. If they’re unmutated, those cases tend to be a little harder.

Then there’s a panel we do called a fish panel. It looks for structural abnormalities in the chromosomes of CLL cells. One of the things we look for is chromosome 17p. That’s where the p53 gene resides. If that is deleted, that’s been shown to be associated with a less favorable prognosis in CLL.

If you have a deletion of part of chromosome 13 and that’s the only abnormality, those cases actually do better than normal. There’s another abnormality they look for in chromosome 11. That’s associated with adverse prognosis as well. So, the fish panel is another way to risk-stratify patients. It doesn’t necessarily influence the treatment, but it tells us what risks there are.

Why do genetic testing if it doesn’t influence treatment?

Some of those studies like with p53 and others, a lot of that data was generated years ago using treatments that were not as good as what we have now. It’ll be interesting to see if those risk assessments will still hold up nowadays with some of the new treatments. We’ll see. What used to be a really high-risk group may not be as bad as it used to be.

Newer Options

Can you talk about some of the new treatments?

Chemotherapy drugs are small drugs that block something that any dividing cell has to do, so that would be how it copies its DNA, unwinds its DNA, how one big cell physically separates into two smaller cells. All the proteins and enzymes that makes that machinery work, those are the things that chemotherapy blocks.

Rituxan is a big antibody molecule that’s much larger than a chemotherapy drug. It sticks on the outside of the cell, and it flags it to your immune system in a number of ways.

Then you’ve got these newer, more targeted agents like Ibrutinib, Venetoclax, Acalbrutinib, Idelalisib, and many others in development. These are smaller drug molecules that go inside the cells. Instead of blocking something that any cell has to do, they tend to be more selective. They target enzymes that are more active in CLL cells.

We’re in this new era where we have these novel or targeted agents. That really started about 10 years ago with Ibrutinib and more recently we’ve had Venetoclax. Before that, we really only had chemotherapy and Rituxan, which is more of an immunotherapy drug.

Ibrutinib

Ibrutinib blocks an enzyme called bruton’s tyrosine kinase or BTK. This is an enzyme that does play a role in normal B cells, but it’s a very important enzyme in CLL cells, too.

You don’t get all the same chemotherapy side effects. It’s a highly effective way of treated CLL. It does still have possible side effects, but it does a good job.

Venetoclax

Venetoclax works in a different way. It works on a pathway of proteins. When you have cancer, the problem can be that the cells are growing too much or that they don’t die when they’re supposed to die. CLL, in large part, sees cells not dying when they’re supposed to, so they’re accumulating. Venetoclax blocks a protein and turns a death signal back on in the cells, triggering apoptosis. That’s just a fancy term for programmed cell death. It restores the cell’s ability to die.

Idelalisib

Then you’ve got this other class of drugs called PI3 kinase inhibitors like Idelalisib. It blocks a different enzyme in the cell.

Acalabrutinib

Recently, we’re seeing second and third drugs in each of these categories. So, at first we had Ibrutinib, and now we also have Acalabrutinib. It isn’t technically approved for CLL yet, but it’s probably going to be approved in the coming year. It seems to be more selective for BTK than Ibrutinib. We believe that some of the side effects from Ibrutininb are due to what we call “off-target effects,” so in theory, Acalabrutinib might have a more favorable side effect profile.

What is the difference in side effects with these drugs versus chemotherapy?

You don’t lose your hair, typically you don’t have as big of a drop in blood counts, and in general you don’t see nausea and vomiting. So, with these targeted agents, you don’t have typical chemo side effects, but they can still have side effects.

For example, Ibrutinib can cause rashes, diarrhea, heart rhythm disruptions, muscle and joint aches, and things like that. About 20% of people wind up having to come off of these drugs because of some side effects. It really depends on the person.

Do you see chemotherapy becoming a thing of the past?

Targeted agents are definitely where the field has moved. For several years there was a debate about which patients should still get chemo.

Really, in the last year based on some recent studies, most experts in the field agree that there’s very little if any role for conventional chemotherapy in the frontline for CLL.

Maybe in the third or fourth line, you might start to think of some chemo. It’s going to be very rarely used moving forward.

There are some newer immune therapies like CAR-T cell therapy that are on the rise too. We never really did a whole lot of stem cell transplants for CLL, but we used to do some. Those numbers are going down. We still get an occasional patient where it makes sense, but that’s not very often.

When is CAR-T cell therapy a viable option for a CLL patient?

It’s not approved as a treatment for CLL yet. It’s something that would be done in the context of a clinical trial. That being said, there are three main classes of targeted agents. There are BTK inhibitors like Ibrutinib or Acalabrutinib. There’s Venetoclax. Then there’s the PI3 kinase inhibitors like Idelalisib.

If somebody has had all three of those classes and they’re still having problems with their CLL, that’s somebody we should be thinking about putting in a CAR-T trial.

Other Advice

How do you handle patients who have questions about holistic or alternative treatments?

In the old days, the doctor told the patient what to do, and the patient did it no questions asked. Doctors these days try to be more collaborative and take the patient’s perspective into account. That can be kind of tricky when the patient is bringing in all sorts of things they read on the internet.

As a doctor, you want to be respectful of the fact that it was important enough to the patient that they brought it up, but at the same time, a lot of these things don’t have nearly enough scientific evidence for us to recommend them.

Diets, supplements, fasting, and things like that are brought up a lot. We don’t have enough good scientific data to support a lot of that.

It’s not to say that those things are worthless; it’s just that we don’t have enough data.

Diet is a big one. For every one special diet that someone is touting, there are hundreds of others saying the same thing. All we can do is give people generalizations of healthy diet, exercise, stress management, support systems, good sleep, and all these things people know to be doing anyways.

I think some patients get frustrated because they just want some simple answers and things they can do. I try to walk through that with them. If a patient is really set on a certain supplement or something, I have our pharmacists look at it and make sure there’s nothing harmful that would interact with their other treatment.

I make sure it would be safe for them to take, and then I’ll tell them as far as I know, it’s okay for them to take it, but we can’t always know for sure how something is going to affect them.

Do you have any advice on clinical trials?

A lot of patients are not very well informed about clinical trials. It’s on the doctor to educate them.

Many people seem to think that trials are a last resort after there’s nothing left for them to try. That’s not true.

There are all different kinds of trials. There are phase 1 trials which means you could be getting a really new drug. Ibrutinib, Venetoclax, and all our new drugs were a phase 1 trial at some point. If patients hadn’t signed up for those trials, those drugs wouldn’t have made it to market. Those patients’ willingness has helped a lot of people.

Then you have trials where we’re testing out how we use drugs and maybe using them in a new combination. It really depends on where a patient is in their disease.

Patients who are nervous about a clinical trial typically say things like, “I don’t want to be a guinea pig.” The thing is, that’s not really the case. In most trials, you will not be the first person to have taken a drug. There are very few scenarios in which the patient would be the first. Like I said, many trials are looking at drugs that have already been approved and just tweaking how we use them.

Getting the word out about being involved in clinical trials is important because it not only pushes the field forward, but it also could give patients access to cutting edge therapies a little sooner.

Do you have any advice for newly diagnosed patients?

First of all, try to understand your disease as well as you can. A lot of people think leukemia is just one thing or lymphoma is just Hodgkin’s or non-Hodgkin’s. Within non-Hodgkin’s, there are about 50 different kinds.

So make sure you understand your disease process and how it’s normally managed so they have an idea of what to expect.

If a patient has something that’s less common, it never hurts to get a second opinion from a specialist who sees more of that disease. We have people who live in more rural areas and don’t want to drive two or three hours when they want treatment.

I understand that, but they could see that specialist every once in a while in addition to their local doctor. That specialist can collaborate with their local oncologist in many cases.

Thank you Dr. Fenske!

Hematologist Oncologist Experts

Advances in GVHD Treatments and Clinical Trials

Hematologist-oncologists Dr. Satyajit Kosuri and Dr. Shernan Holtan, patient advocate Meredith Cowden, and LLS clinical trial nurse navigator Ashley Giacobbi discuss the role clinical trials play in advancing the GVHD treatment landscape.

...

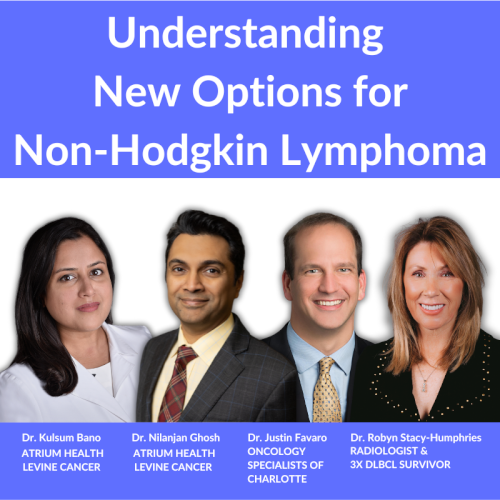

Accessing the Best Care for You or a Loved One: Understanding New Options for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Dr. Kulsum Bano, Dr. Nilanjan Ghosh, and Dr. Justin Favaro discuss the latest advances with 3-time DLBCL survivor and patient advocate Dr. Robyn Stacy-Humphries.

...

Rafael Fonseca, MD

Role: Interim executive director, hematologist-oncologist

Focus: Multiple myeloma, new drug development

Institution: Mayo Clinic

...

Farrukh Awan, MD

Role: Hematologist-oncologist, associate professor

Focus: Leukemias, Lymphomas, BMT

Institution: UT Southwestern

...

Nina Shah, MD

Role: Hematologist-oncologist, researcher

Focus: Multiple Myeloma

Institution: University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)

...