Theo’s Gleason Score 7 Prostate Cancer & Early Stage Kidney Cancer Story

Theo shares his story of getting diagnosed with relapsed and metastatic prostate cancer, undergoing surgery, and radiation.

Having rampant cancer in his family and the African-American community, Theo lends a voice to advocate awareness, early diagnosis, and open conversations.

Explore his story below to hear all about his experience and very timely message. Thank you for sharing your story, Theo!

- Name: Theo W.

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Prostate cancer

- Early kidney cancer

- Age at DX: 52 years old

- 1st Symptoms

- PCP, PSA of 72

- Treatment

- Surgery

- Partial nephrectomy

- Radiation

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Life outside Cancer

I’ve always adopted the mantra: You get to live a day at a time, and you get to choose how you live it. That’s really all we get.

I’m happily married to my wife of 42 years, Beth. We have three daughters. Leanne is the oldest. Randy is a middle child. She’ll tell you the dreaded middle child. Lauren is the youngest. We now have seven grandchildren.

I run a business in Akron, Ohio. My business is to manage money for people that are about to retire or are retired, make sure they have enough for the rest of their lives, and leave a legacy to some institution or some people.

Learning about prostate cancer

I have no symptoms of anything whatsoever. My doctor is also a dear friend of mine and who also happens to suffer from prostate cancer.

During my routine annual exam, he said, “Theo, your PSA is elevated. I’m going to refer you to a urologist.”

I went to the urologist. He got the results of a blood test. He asked me a few questions and said, “Let’s do another blood test in about three or four days.” We did another one, and my PSA rose again from 12 to 14 very quickly. So they did the biopsy.

I remember where I was and what I was doing when I got the phone call on a Saturday morning from my doctor at the Cleveland Clinic. Incidentally, my wife had been diagnosed with melanoma the day before.

We’re in the car, and I get the phone call. He says, “Theo, it’s prostate cancer. Let’s set up a time to talk. I want you to interview me, the surgeon, talk to a radiologist, and determine a plan of action.”

I think it was the following week that we went to the Cleveland Clinic. That began the process of my prostate cancer journey.

Getting diagnosed

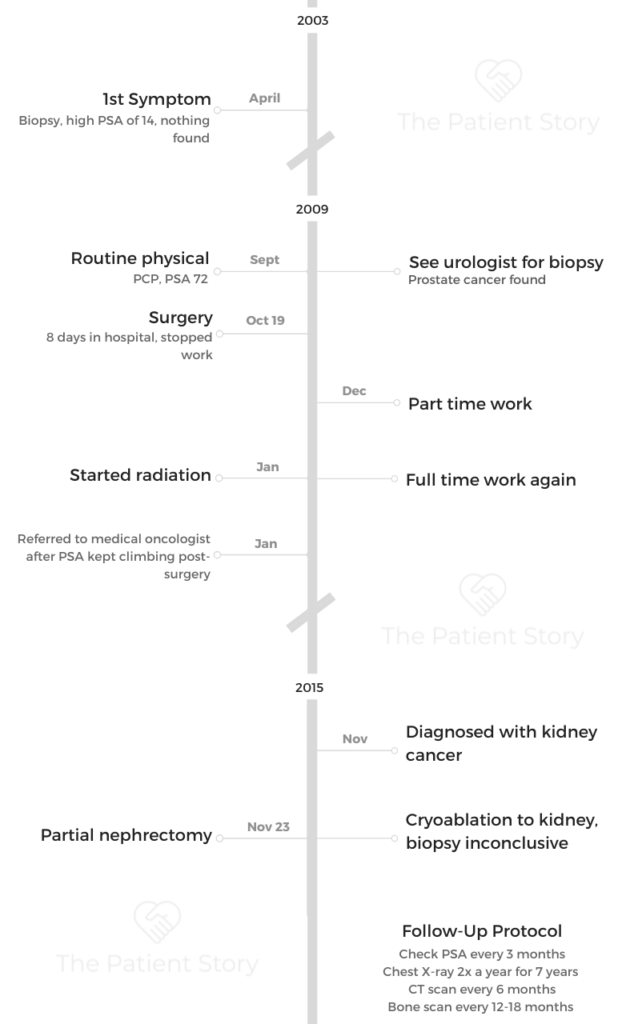

It was 2003 when I had the first biopsy. That biopsy was inconclusive. It said I did not have prostate cancer.

But it was not the Cleveland Clinic then. It was a local hospital and doctor here in the Akron area, a local nephrologist. Knowing what I know now, there should have been some type of phone call. I left that doctor’s office, and there was no follow-up appointment of any kind.

Normally, I guess there should be a three-month or six-month routine biopsy scheduled. I missed a couple of years of getting my annual exam from my primary care physician. So when I went to the primary care physician, he said, “Your PSA is up in the 60, 70s range. You need to see a urologist.”

My doctor, my primary care physician, being a person that had prostate cancer himself and was able to keep his numbers low, possibly should have been more alarmed about it and said, “Get back there every six months.”

I was instructed by no one, and at that point, I didn’t know enough about the disease on my own to say get back in there every six months.

I was diagnosed in 2009 at 52. High end of intermediate risk and the low end of high risk. No staging. That’s with aggressiveness, and that’s pretty aggressive, especially at 52.

Family history of prostate cancer

No. My dad did not. His dad did not. My brother did not, and he’s an older brother. This came out of left field on us here.

Receiving the bad news

He looked at me and said, “Don’t panic.” He literally said, “Mine has been up close to 1,000.”

He took a new prime shot and took them the rest of his life, and his PSA remained low. He did not die from prostate cancer. He lived into his early 90s.

I thought about two things. He’d always told me in my early 30s that I had an enlarged prostate. In my mind, I said, “Maybe that could be part of the PSA issue. No one is being really urgent about it, getting back in there after 2003.”

I was hoping, so I said, “Maybe it’s just a high PSA because of that.” Of course, I was very nervous that it could be prostate cancer.

Describe the biopsy

Be grateful that times have changed since my biopsy then. Currently, they give you a shot literally in the prostate that numbs it, and so it’s not painful. That was not the case with my biopsy. There was nothing.

I think they do three to four snippets per quarter. It’s in quadrants. By the time you hear the clip, it’s too late. It’s a very painful, uncomfortable but short procedure and process, which has changed now.

Getting the results

We got the call. The surprising thing is neither one of us broke into tears right away.

We ran a stoplight, actually, when I received the information. We looked at each other. I think one of us said, “What are the chances of both of us having cancer at the same time?” That’s how our relationship is. She tells me even to this day, “If cancer doesn’t kill you, I might.” That’s the kind of relationship we have.

We finished our errands. Of course, we kept the conversation going and talked about what the next steps may be and that we had to call the girls. They were naturally pretty devastated. The ones that were close to home came over as quickly as they could.

We just started plotting out when and what. They were all for surgery. My whole family was. I quite frankly was not interested in surgery at all [and] wanted to do the radiation instead because it was less invasive.

At the end of the day, I never really had peace about it. I opted for the surgery.

Breaking the bad news to the family

It’s difficult as the process was literally to put everybody on speakerphone and called everyone.

We did joint calls with all of our close friends, our pastors, our family, and our parents. That really took a few days because at that point, there’s some crying on your own you’re doing. You’re physically exhausted, and you’re saying, “We’ve talked to eight people today, and let’s just pick this up tomorrow.”

Just make sure you talk directly to your closest friends, whether it’s phone or face to face. You do not want them to find out secondhand at all. They show up, and they go way beyond the call of duty to make sure you’re okay.

What support was most helpful?

You have to make the assumption that people want to help. I’m more of the person that is the helper and less likely to call and say, “Help.”

We would meet a group of guys at Einstein’s for breakfast. Leanne can tell you about this. She says, “I don’t believe you have 10 to 12 guys that meet every morning and just talk. No, guys don’t do that.”

Because I was at home with a catheter, I couldn’t get out. One friend says, “Is there anything I can do for you?” I said, “Yes. Go to Einstein’s, get me a cup of coffee and a bagel, bring them to my house, and sit with me and have breakfast.” That did as much for him as it did for me.

People just want to help. That story is an example of you needing your friends and your friends needing you. The opposite end, for kids, it could be scary.

Antonio, Leanne’s son, was five. He walked into the library and saw me in my bathroom, sitting there. I think Leanne had to tell him, “It’s okay to go over there and sit in his lap. He’s fine. He has cancer. Number one, he’s not going to get on you. Number two, he’s not fragile at this point. It’s perfectly okay to go sit in his lap.”

He was very cautious. With kids, when you see them, you need to tell them, “I’m okay. Come over here and give me a hug.”

Why was that an emotional moment for you?

I’ll tell you exactly why. “I want you to look at this chart.” He literally put his head down and wouldn’t look at me.

I took the chart, and I said, “Is this me right here?” He says, “Yes.” I said, “I’m at the high end of intermediate risk and the low end of high risk.” I said, “This is saying the average life expectancy is 11 years?” He says, “Yes.” I said, “Explain that to me.” He says, “Well, eight years will be great, two years you’ll be on hormones, and last year you’ll be miserable.”

The very first thing I thought was, “Antonio is five. Where will I be when he’s 16?” I did the calculations, and I said, “I’ll live long enough to see him turn 16 and get his driver’s license. If I make it that far, I’ll be fine.”

That was my first thought. Will he be driving? Will I get to see him drive? Will I get to see him become a 16-year-old?

Of course, we’re beyond that now, but that was my first thought when I calculated those numbers.

First of all, if they’re really close to you, you’re more forgiving.

Most times, people don’t need to say anything. Just an, ‘I’m sorry. I feel bad. I’m here for you. If there’s anything I can do, let me know. This is terrible. This is devastating. I don’t know what to say. I don’t know what to do. I feel horrible.’ Leave it at that, for the most part.

Treatment Decisions and Surgery

I have a very good friend in Chicago who incidentally was also going through prostate cancer. This gentleman was retired. I called him up.

He was at his vacation home. He said, “All the treatments are pretty much the same success level. If I were you, I would strongly consider radiation, because by the time you add up all the side effects, that one in your situation with your PSA number, that’s what you should do.”

Monday morning at eight o’clock, my cell phone rings. “Hi. I’m Dr…. head of urology at the Cleveland Clinic.”

I said, “Well, doctor, he told me that you said radiation makes the most sense.” He goes, “No. I don’t think so. I think here at the clinic, you need to do surgery because if you do surgery and you have a relapse or recurrence, then we can do radiation.” He said, “We do a nerve-sparing surgery so you don’t have issues going down the road.”

Once I heard that, I said, ‘I don’t know where this is going, but I’d rather have more than one shot at it if this is not going to go well.’ That’s what I did. I did the surgery.

Fears with surgery

You’re always concerned about your sex life going forward. But a nerve-sparing surgery makes it more possible for a man to maintain an erection, to have sex. That’s a big concern for a lot of guys.

I did have one of my buddies tell me, “Hey, at the end of the day, your wife may prefer just a lot of cuddling, and you will be alive.” That was great advice.

Cleveland Clinic made sure to tell me that. It was also one of the discussions that I had with the second opinion doctor. He kind of felt like if you went with the radiation, then you would have less issues later, and it would not affect your sex life now. That was his reason for it.

He says, “If we’re going to come up with the same success rate, then why impact your life in that way now?”

Then again, as I said before, for me, it was more important to do the surgery, and then the added bonus was when he said they could do the nerve-sparing. I said, well, okay, then that’s it. That makes it less of an issue.

Describe the surgery

My doctor said, “This is going to be a pretty routine surgery. We will be using robotics. That will help with less bleeding and a much quicker recovery.”

I am told that my father accosted him when he came out because the surgery ended up being about six or seven hours. It was substantially longer than it should have been, and my father just was not too happy about that.

He told me the recovery would be three to four days and I’d be out of there. He said, “You’ll have a catheter for several weeks. Come back, and we’ll take that out.”

He said, “You should be off and running, for the most part. You can start back to work in a month and a half or so.” He felt that the surgery would be pretty routine, with very few complications. That ended up not being totally true.

But you never know until you get in there. So I’m glad he did. Things took a little longer, the surgery and the recovery. Getting out of the hospital took longer than normal.

How long was the surgery?

Three to four hours.

He always talked about the nerve-sparing, and one of my seminal vesicles actually had cancer, so he had to remove that, and then the margins. When you do the surgery, you remove lymph nodes and they usually do a few, but they ended up doing 10 or 11 removals of those. That’s what took the time.

The recovery was supposed to be four to five days, but I stayed for eight days in the hospital.

How you were able to get through?

My issue was my creatinine levels were higher than they needed to be, and so they were worried about kidney function. It took a while to get those belts under control.

My advice is, if you’re in a hospital, you need to have your family guard how often people come and go.

They really have to look out for you in terms of your rest and be able to delicately say, “He’s glad you came to see him, but he really needs to sleep right now, because I’m sure you know you do not get any rest at the hospital.”

Every three to four hours, someone’s coming to do something to you, and so therefore the only time you get a rest is when you get out of the hospital.

They’re going in at all hours of the day and night, checking your blood pressure, checking all the different stuff you’re hooked up to.

Post-surgery care

One of my main issues is I could not pass gas. When I finally did, no one was in the room but me. I got my phone, and I text to my wife, “It’s a girl.”

She said she read it out loud and everybody knew what it meant, and everybody out there just erupted, and they want you to go. I tried prune juice, everything, and nothing worked. They said you cannot leave, and so that was the last thing I had to do before I left. After that, I went home.

Taking it lightly helps. You just have to.

I did have another kind of strange experience. There was one person that I have a temporary rift with. But sometimes when you’re sick, they feel a need to come around and try to fix it all before.

She told me that someone wanted to come, and my blood pressure went up. She had to kindly tell them no, and that’s difficult. But I will say people will come to see you for the right reasons, and people will come to see you for the wrong reasons.

»MORE: Read more patient experiences with surgery

Dealing with extended period of time at home

I think I ended up going two weeks longer than I should have, but I thought the catheter was great. You don’t have to get up to go to the bathroom, because you’re sore after surgery.

Every time I tried to lift myself off of a chair, it’s just painful. So with that, I didn’t have to get out of bed and go to the bathroom at night. I was reluctant to let it go, but I had to.

When I found out it didn’t come out the day it was supposed to, it quickly became irritating because I was mobile. I was in less pain, and now it became an inconvenience because I can’t go running around outside, although I did around the house. I was living in the country at the time.

The last week or so was really, really hard. “Just get this thing out.” Initially, it was very convenient.

I was supposed to have it for two weeks. I think I had it double that. If it was supposed to be a week, it was two. But I’m pretty sure it was close to a month that I had that catheter.

I have to just be careful of infection, just have to keep it clean. Other than that, I didn’t have any issues with it whatsoever.

Radiation therapy

First of all, I made a very dear friend in this process. I was going to my first radiation treatment, and I got out of my car in the parking deck. I’m about 6’7, and Black obviously, and there was this 5’7 White guy who got out of his car. We both went through the door out the deck.

We went to the building for cancer treatment. We got on the elevator. He said, “Are you following me?” I said, “It depends on where you’re going.”

He said, “I’m going to start my radiation treatment for cancer. You’re the last person I want because you should not be following me.” I said, “I actually am following you because that’s where I’m going, too.”

We’re dear friends up to this day. I had a buddy who got treatment sometimes around the same time.

It was treatments every day, Monday through Friday, for seven weeks.

At that point in time, my youngest daughter worked downtown near the clinic. She would just show up unannounced. I never knew what day she was coming, what day she wasn’t coming.

She wouldn’t tell me. She would show up, and I would be in there for probably 20 to 30 minutes. It wasn’t long. Out and back in the car, and back home or back to work.

It was an inconvenience from a travel standpoint, but there was a certain amount of comfort.

The hospital is about a half hour from my house. It was a highway drive mostly. It was a good time.

Until this day, I get comfort when I drive under the main campus of the Cleveland Clinic. Seven weeks out, you know you’re done, you ring the bell, and you just hope your PSA doesn’t climb.

Describe the process of radiation

For prostate cancer, you just get on the table. They put a tarp over you. You pull your pants down to your knees. You’re on this flatbed, and the radiation machine just goes around.

It actually tilts and goes around and hits specific areas that they’ve targeted and certain margins outside of where they think the prostate cancer may have spread to.

You see the same three or four nurses, so you develop relationships with them.

That’s really the process. You’re done, and you leave and go back to your life.

Side effects

I had no side effects until the last two weeks.

I would have some burning during urination. Women have urinary tract infections, so they may be used to that.

That was my first experience. It gets to the point where you tell yourself you don’t want to drink water because you don’t want to have to go to the bathroom, but you have to.

You let them know, and then they give you things like pills you can take to help with that. They did work. It was very surprising when I first started, and I was very glad to take those pills after I got to.

The doctor did tell me that could happen. I was actually surprised that it took as long as it did and thought maybe it wouldn’t, but it did.

Outside of that, no burns, no rashes, no irritations of any type.

The issue with me was when they checked my PSA after the surgery, and it started to rise again. That’s evidence that I have a recurrence. We don’t know how far.

They looked at the surgery and said, “Let’s do an additional margin of X.” They feel they can go so far before they start affecting the lymph nodes. Once they affect the lymph nodes, then you have a whole different set of side effects.

The radiation itself was targeting a specific area with the idea of not having issues with your lymph nodes down the road.

Signs of recurrence

I think when it got up to about two was when they said, “Okay. Hey. We need to start doing something,” Because, at one point, it was almost undetectable right after the surgery. Then within two weeks, it started declining.

Addressing the recurrence

It was, “Hey. Let’s start every three months and see where this goes.”

Unfortunately, it went from two to four and from four to six, and then they said, ‘You’re going to be dealing with this the rest of your life. You need to talk to a medical oncologist.’

I went to his office, my wife and I. He reared his chair back and put up his cowboy boots on the desk, and he says, “Do you know why you’re here?” I said, “Yes. I have prostate cancer, and my PSA is still climbing.”

He goes, “Do you understand that from now on, we’re monitoring this and that you are going to be dealing with this the rest of your life?” I reluctantly said, “I do.”

He started out, and he just wanted me to know the gravity of it. “We’re just going to be maintaining this for the rest of your life.” That’s when it really hit me.

When the doctor said, ‘You’ve got eight good years, two years of hormone treatments. Your last year is miserable.’ That’s when it hit me. I said, ‘This really could be me.’

Managing a chronic disease

That’s the case; it was a chronic disease. He told me what we would need to introduce, when, and what things they would use, and then went on through [to] talk to them about clinical trials.

He said, “For now, we’ll monitor it.” Then that’s what starts the CT scans, the bone scan once a year, and I’d heard about kidney cancer also. I was getting the chest X-rays, and then all ended up fine. So I’ve got to stop the checks.

2nd Cancer

Getting diagnosed with kidney cancer

I was diagnosed with kidney cancer five years after the radiation. They removed it, and of course, the concern is if it returns, it could spread to the lungs. So I have to do the scans, basically chest X-rays, because I was already getting a CT scan.

That kind of doubled for both the kidney issue and the prostate issue. I had to get the X-rays, and five years and that was done. That was totally successful, and I had a recurrence there. I’ve had some cysts on my kidneys that I didn’t know I had until then, and so they’ve watched them. That’s how they discovered it.

It was at a very early stage.

In fact, I had a colonoscopy and was out to dinner, getting ready to go to a Todd Rundgren concert. My side started hurting me, so off to emergency I went. Didn’t go to the concert.

They said, “You have cysts on your kidneys. That’s not why you have pain, though. You have pain from the gas that is stuck in your body from your colonoscopy. But you have cysts in your kidneys and probably want to get those watched.”

That’s when I started getting them washed, and not too long after that, they figured that it’s all the colon cancer and not the kidney cancer.

I had a PSA check every three months, every half a year, every six months a CT scan, and then every 12 to 18 months a bone scan. That’s just because they’re watching to make sure it doesn’t spread to the bones.

So far, it’s been all good.

PSA levels so far

It’s crazy. They continue to climb until 2019. It got to 52. Since 2019 it has gone up and down, which is really strange.

It sits at 57 now, so I called my doctor, because I was supposed to have a bone scan in December, and said, “I don’t see a bone scan on my chart. Shouldn’t I be having the bone scan about now?” He said, “Well, think about it. In 2019, your PSA was 52, and now it’s 57. Percentage-wise, there has been very little movement. I don’t see any reason to do one right now.”

There’s a couple of philosophies, and his philosophy is if hormone treatments after metastasis do not prolong your life any more than taking hormone treatments before metastasis, why subject yourself to the side effects?

That’s what we’ve done. I have not started hormone treatments at all, and they have not found any metastasis at all.

I did mention my dear friend, who I’ve met, the little 5’7 guy, and he’s a worrywart. He started his hormone treatments when he hit 10, and so it’s different for different people. I talked to him often, and he tells me, “Theo, I’d be a nervous wreck.”

I said, “I know you with time, and I’m glad you’re taking hormone treatments. It’s different, and the doctors are different. I have a different oncologist now than I did then — Dr. Timothy Gilligan. He’s a white gentleman, but he specializes in prostate cancer for African Americans.”

I really feel like I’ve got an individualized treatment plan that is geared towards the quality of life, according to the risks that the patient wants to take. You just have to say, ‘Hey, I don’t feel like taking any additional risks by not starting these hormonal treatments.’ I just don’t. I haven’t.

I think Lan said there’s a Dr. Pan. I can’t really recall the guy’s name, but he knows a doctor that’s out there at the City of Hope, and the previous doctor ended up taking a job somewhere else. Then I just got on the Cleveland Clinic website and fell upon his name and then called him and said, “Hey, I need you to come to be my doctor.”

Homeopathy and naturopathy

What supplements do you take?

I have a bunch of supplements that I take, but the real key is a machine called a HOCATT. It’s designed to get in there for about a half hour.

They shoot oxygen and carbonics into your nose, which drains you, but more importantly, they raise the temperature. It gets very hot, and the idea is it stimulates your white blood cells because it says my body has a fever. I need to run and attack anything that is suspect, and I get that.

I go every Friday at 2:30 or 3, what’s called my spa treatment at the end of every week.

They told me it will raise my PSA temporarily, so I don’t want to get my PSA check when I get out of this thing. Overall, it should slow down the process and give my body the best fighting chance that it has.

I also take vitamin D and fish oil.

Deciding on integrative treatment

I just did it and then told them, and fortunately, Cleveland Clinic is adopting some of that on their own at this point. He’s perfectly fine. There’s no, “Hey, you know what’s in these supplements? Do you know what you’re taking? Is this going to counteract what we’re trying to do here?”

No resistance, judgment, or anything of any kind from him at all. It’s been great.

When to start hormone therapy

For him, it’s just whenever the bone scan shows metastasis. It’s cut and dry with him. I did ask him a question. I didn’t want to ask him, “Doc, at what point in time are you pretty sure you’re going to find something?” But he said at 50.

The next time I see him after, I asked him. I’ve been over 50 for a while, especially if my next bone scan is clean. I said, “What does that say?” I don’t know what that says, but he says, “Most people were going to find something when they start getting a PSA of 50.” I’ve had scans since it’s been 50 in 2019.

Managing “scanxiety”

I don’t do very well with that one because of my charts. If I get my PSA checked today, I know I’m probably going to get an answer within 24 hours.

If I get up to go to the bathroom at 3:00 a.m., I’m checking my phone, and there’s a certain amount of anxiety. Once you do the password, I get an email that says ‘test results.’ That’s also stressful.

I had a very dear friend who died from prostate cancer. It was caught in the latest of late stages and did a lot of experimental stuff.

He told me the best advice I’ve had. He said, “You have to thoroughly enjoy the highs.” You’ll have the highs and you’ll have the lows. But you got to celebrate every high you’d get.

Whenever my PSA stays the same or goes down, I keep a chart. I look at that graph, and I look at how fast it goes. If it doubles in three months, you’re in trouble. I’m always looking at what rate is it doubling? Is it nine months? Is it 10 months? Is it a year? That affects me emotionally.

You don’t really want the information, but you do. It’s a mixed bag there. I don’t do a good job of handling that part of the anxiety.

»MORE: Patients describe dealing with scanxiety and waiting for results

Caregiver support and survivorship

You keep your plans and your dreams until you can. From a caregiver’s standpoint, being the guy messes with my wife’s security.

We do talk about that. Her statement now is, “You may end up living longer than me.” That could be true.

I don’t know. We don’t know. You have to have people, whether it’s a spouse or a good friend or both, that you really can talk about everything you’re feeling.

We’re both type A personalities to the point that if I get up in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom, I’ll come back and my pillow will be on the floor, and she’ll say “Go make some money.”

I’m like, “It’s 4:00 a.m. I can’t. Let me sleep for another hour or two.”

Humor has a lot to do with everything in terms of hightailing. Find somebody safe with whom you can express how you really feel and will let you express that.

I don’t get a lot of sympathy, and I don’t want a lot of sympathy. I don’t feel like I need it. There may be a time that I do.

Life is normal, because as long as you are able to, you still get to choose what you’re going to do and what your outlook on life is going to be in the end.

Some friends and I have a saying, “Your tombstone should have three dates on it, not two dates: the date you were born, the date you stopped living, and the date you died.” Hopefully, the last two will be the same day.

My wife has been the best thing for me. Because if I wanted to have a pity party, which I typically don’t, I couldn’t have one anyway.

Having children as support

Leanne and I are a lot alike, and we do things without really talking about it a lot.

She didn’t really tell me she was going to start doing the research. I found that out almost secondhand. That was the inspiration for it.

I remember when she was in prep school in high school and brought home straight A’s the first semesters as a freshman, and I asked her, “Do you feel any pressure to get straight A’s?” She said, “No. This is okay.” “Good. That’s all I want to know.” I’m floored.

She’s never been afraid of things. She likes the limelight. I’m just impressed by her all the time. I’m just, “Damn. She’s an impressive woman.” That’s why I’m proud of her, that she is on a mission.

Advocating in the community

We do now, but nobody talks about it until you get it. Then all of a sudden, out of the woodwork comes, “Well, I had prostate cancer three years ago.” “Well, I had prostate cancer four years ago.”

You’re walking around with all these guys, 3 out of 10, 80% African American, which have had it, and nobody knows anybody else has had it. Now there are support groups, that type of thing.

Not having it in my family, I was not that exposed to it.

Then having a doctor that had prostate cancer that was doing okay and died in his ’90s and not from prostate cancer. There just wasn’t as big of a fear of it, but then once I got it and you start looking around, you’re like, “Whoa, wait a minute, this is everywhere.”

At the Cleveland Clinic, they told me they had a kid in his late 20s, a Black kid that had prostate cancer. Do you start checking in your 20s? They say no. I learned about the process after I was already in it and the numbers after I was already in it.

Conversations in the Black community

Men generally, but especially men of color, don’t go to the doctor. A lot of them don’t. Some of it is because they don’t have insurance. Some of them are macho. Some of them fear the doctor. They don’t want a rectal exam.

I think getting out there, like getting your blood drawn. If you can do that, and you could start doing that when you’re 40, it’s going to save your life. I think the education process.

You’ve got to look at the hand of the government with the Tuskegee issues, saying, “I don’t know if I can trust.” Which, by the way, is a whole other story with COVID, because I’m finding more middle- and upper-class white men not wanting to take it, which is strange to me.

A lot of my Black friends have gotten the shots. I’ve had my first shot. That’s a whole ‘nother story.

Just the lack of trust for doctors, the absence of African-American doctors.

Again, I’m 63 now, and so I’m talking for my age group. It may be different for people 20 years younger than me, but those are some of the reasons.

My mom to this day calls me when my dad goes to the doctor and asks me to go, because he does not want her in the room while he’s in there with a doctor.

The last two times, I told her, “Yes, that’s the macho thing.” It’s the “keep her in the dark” thing so if I get bad news, she doesn’t have to think about it.

I just convinced her, “You just barge in there and hear what the doctor has to say.” That’s what she’s doing now. She’s 91, and he’s 88. There’s just this fear of doctors.

What needs to change?

I asked Leanne about that at one point in time. Can’t some medical association or some medical say, “Hey, all the doctors in Summit County, and such, every African-American that comes in here, tell them that we have to do a blood test. We have to draw blood as part of your health. Not just for PSA.”

I don’t know if that’s an oversimplification, but it should be almost demanded that doctors do that for people that are at risk. Because that is the first step. It’s the least costly; it’s the least invasive. It’s the least threatening thing you could do that gives you the information you need to take care of yourself.

Prostate cancer is one of those cancers that are very treatable if you can catch it. My prostate and kidney cancer was that example. They caught it quickly, did it, and I’m done with it.

Cultural differences and doctor training

I think it’s a great conversation. The way that conversation in a perfect world should have gone is, “Theo, your PSA is at 14. That’s high. You are a candidate for getting prostate cancer. However, the success rate if we find it early is you basically get to live your life as if you never had it. As scary as this sounds, Theo, I need you to come back every three months. Do this so we can catch it and do something about it, and then you can have a normal life.”

I would have been scared to death walking around feeling I’m a walking prostate cancer. That’s a whole different psychology, but coming out on the other end of that with less risk at the end of life. That’s a difficult discussion that the doctor should have with the patient.

Opening the conversation of risks to kids and grand kids

I have not, but I will. I’m 62; 20 years puts me at 82 if I live that long. 17 put him at 37. I’ve done the math.

We’ll have the discussion before he’s a candidate for getting diagnosed with prostate cancer. Whether that’s him and I talking over an ice cream cone, or me telling him goodbye in his life. I feel there’s time, but having had this discussion with you, I’ll approach the subject with him now. Why not?

The critical part is you’re at a higher risk than most because I’ve had it. It is 100% curable if they catch it on time. Just stay in front of it. Promise me at 35-36, if not sooner, that you’ll get an annual exam. That if you do not hear from your doctor about a blood test by a certain age, you’ll ask for it.

Normalizing the conversation

We’re all interested in living as long as we can. Part of that is taking steps to assure that. One of the easiest things you could do is just go get an annual physical exam.

When you get one, ask for a blood test to find out what your PSA is. I don’t care what number they give you. You want to know that number today, more than you want to know that number tomorrow.

Diversity in clinical trials

I think I would try, and my doctor, Dr. Timothy Gilligan, that’s another thing. He is well on top of clinical trials and will suggest one at the appropriate time.

I am all for anything that could prolong and improve the quality of life.

With prostate cancer, chemotherapy does not. Chemotherapy with a lot of cancers is curative. I don’t feel that I would opt for that if they said, “We can give you three more months.” I’d rather have the quality of life.

Now, if I can go into his office and he tells me, “You have to start chemotherapy,” all bets may be off. I may be retracting everything [I’m] saying right now because, at the end of it, everybody wants to live as long as they can.

I’ve seen a few people elect not to get chemotherapy. I looked at them, and I said, “They went out the way they wanted to go out; they looked the way they wanted to look.”

I’m also concerned about what view will your grandchildren have of you before you die? What will you look like? I know that could be vain, but I am concerned about it because those imprints stay on your life for the rest of your life.

I think we should go online and look for doctors that talk about doing clinical trials and specialize in dealing with African-American prostate cancer. They’re out there. I had four that I was looking at, and that’s why I chose him.

All of us get a day at a time. Relationships are the most important thing in this world, period, and that’s it.

Inspired by Theo's story?

Share your story, too!

Other Prostate Cancer Diagnosis Stories

Jamel Martin, Son of Prostate Cancer Patient

“Take your time. Be patient with the loved one that you are caregiving for and help them embrace life.”

Joseph M., Prostate Cancer

When Joseph was diagnosed with prostate cancer, the news came as a shock and forced him to face questions about his health, future, and faith. He shares how he navigated his diagnosis, chose robotic surgery, and learned to open up to his loved ones about his health.

Rob M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Burning sensation while urinating, erectile dysfunction

Treatments: Surgeries (radical prostatectomy, artificial urinary sphincter to address incontinence, penile prosthesis), radiation therapy (EBRT), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy or ADT)

John B., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9, Stage 4A

Symptoms: Nocturia (frequent urination at night), weak stream of urine

Treatments: Surgery (prostatectomy), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy), radiation

Eve G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels detected during annual physicals

Treatments: Surgeries (robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy & bilateral orchiectomy), radiation, hormone therapy

Lonnie V., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Urination issues, general body pain, severe lower body pain

Treatments: Hormone therapy, targeted therapy (through clinical trial), radiation

Paul G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery), radiation, hormone therapy

Tim J., Prostate Cancer, Stage 1

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery)

Mark K., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptom: Inability to walk

Treatments: Chemotherapy, monthly injection for lungs

Mical R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 2

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level detected at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Jeffrey P., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; routine PSA test, then IsoPSA test

Treatment: Laparoscopic prostatectomy

Theo W., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level of 72

Treatments: Surgery, radiation

Dennis G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9 (Contained)

Symptoms: Urinating more frequently middle of night, slower urine flow

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Lupron)

Bruce M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4A, Gleason 8/9

Symptom: Urination changes

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Casodex & Lupron)

Al Roker, Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7+, Aggressive

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level caught at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Steve R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4, Gleason 6

Symptom: Rising PSA level

Treatments: IMRT (radiation therapy), brachytherapy, surgery, and lutetium-177

Clarence S., Prostate Cancer, Low Gleason Score

Symptom: None; fluctuating PSA levels

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)