What is a Clinical Trial Really?

Busting Top Myths About Cancer Clinical Trials

There are so many myths surrounding clinical trials. Many question, “Will I get a placebo? What is the cost of a clinical trial?” To bring some clarity to an often confusing, myth-riddled topic, The Patient Story and The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) have teamed up to discuss what a clinical trial is, the phases of a clinical trial, and how to figure out the logistics of paperwork, tests/scans, and finances.

The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) is a global leader in the fight against cancer. LLS funds lifesaving blood cancer research around the world, provides free information and support services, and is the voice for all blood cancer patients seeking access to quality, affordable, coordinated care.

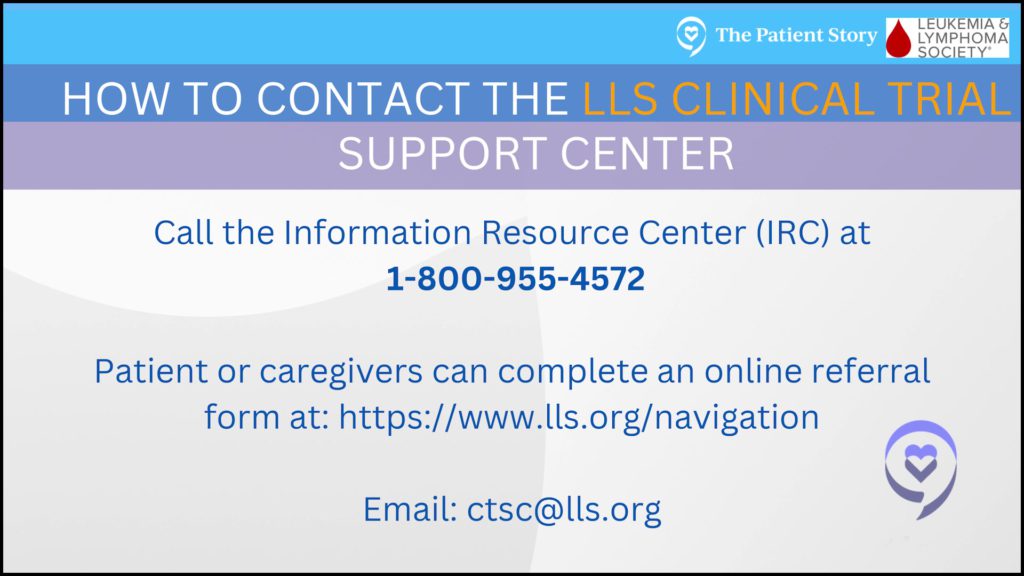

The Clinical Trial Support Center (CTSC) is a free service provided by the LLS to help patients find clinical trials, find financial support and to overcome barriers.

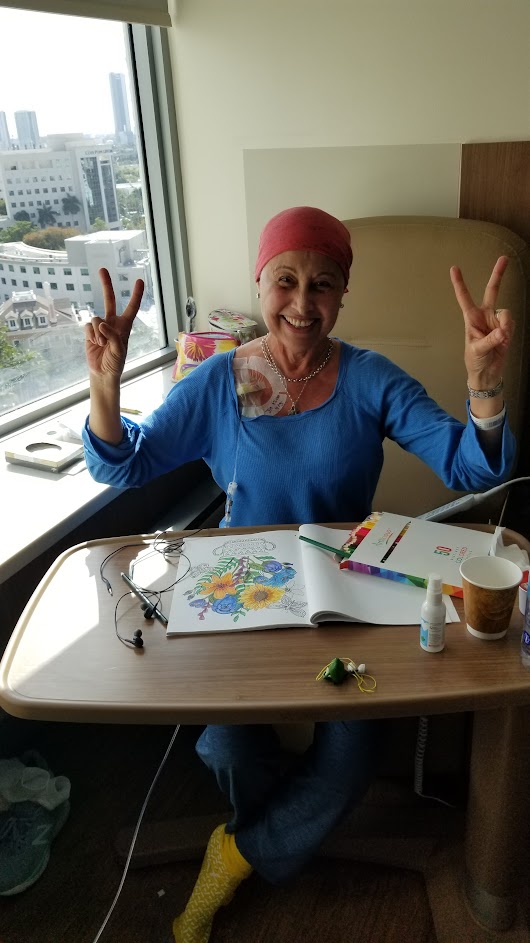

In this conversation, Domenica, a cancer survivor who has participated in clinical trials, opens up about her experience, her fears and concerns, and explains how it helped save her life.

She’s joined by Crissy Kus, a CTSC Nurse Navigator, who worked side by side with Domenica to find and join clinical trials, and CTSC Director Leah Szumita, an expert in clinical trials.

Thank you to Crissy, Domenica, and Leah for sharing your stories and expertise!

This story is adapted from a webinar held on November 9, 2022. A copy of the slideshow presented is available at the end of the article.

- Introductions

- Clinical Trial Information

- Domenica, how did you learn about clinical trials?

- Domenica, what questions did you have before participating in a clinical trial?

- Leah, what top concerns do you hear from patients?

- Domenica, how did your doctor describe the clinical trial to you?

- Leah, what are the phases of a clinical trial?

- Domenica, how did your doctor recommend going somewhere else?

- Domenica, how did your doctors work together as a team?

- Crissy, what resources are there to help guide patients?

- Clinical trial paperwork

- What kinds of treatments, tests and scans happen during the clinical trial?

- Crissy, why do clinical trials need to do so many tests and scans?

- Clinical trial side effects

- Travel and logistics for a clinical trial

- What was your experience with clinicaltrials.gov?

- Domenica, you’re headed for another clinical trial

- Q&A from the Webinar

- Q&A: Do you help outside the US?

- Q&A: How has the pandemic affected clinical trial administration?

- Q&A: During the clinical, does the patient continue with regular visits with his or her oncologist?

- Q&A: How do I overcome the fear of choosing incorrectly between a clinical trial and standard treatment?

- Q&A: Was it hard to choose the clinical trial, Domenica?

- Webinar Slideshow

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Introductions

Crissy

Crissy: I’m Crissy. I’m located in the Midwest. I’ve been a nurse for a little over 10 years, and I started out my career at the bedside. [I was] working with blood cancer patients and stem cell transplant patients from [the] time of diagnosis of a new blood cancer through stem cell transplant and many years beyond.

I have sort of worked in a few different spaces in the blood cancer world, most recently in CAR-T cell therapy and in clinical trial coordination. I’ve been with LLS for about a year and a half, but all of my background, from bedside to my job now, really gives me [a] good understanding of the unique challenges and vulnerability that patients are in from the time they’re diagnosed and throughout their journey.

Domenica

Domenica: I feel so good to be able to share my story. Before my diagnosis of CLL in 2009, I had a very successful career in entertainment and in the media. I was a show host. [I was] in various TV shows, a radio host, a professional singer/songwriter, journalist for lifestyle segments and an actress. I was [living] my dream, and I was feeling so accomplished with myself.

Then you get the diagnosis, and everything changes. I was first diagnosed in 2009. It changes the outlook of your life, and you begin to think [about] something you maybe never thought would happen to you. At that point, I was in watch and wait, and I continued working.

Then came one cancer after the other. I worked through those years and treatments, but in 2017, [I] began very, very intense treatments. I had different cancers and [went through] not only chemo but also radiation. [At that point] I couldn’t do it anymore. I just concentrated [on] getting cured, to try to find the cure and to be strong. That is when I decided to leave everything and just [began] to fight.

Leah

Leah: I have been a nurse for just about 20 years. For the first 15 years of my nursing career, I was at the same Boston teaching hospital, where I spent half the time in the medical ICU taking care of hemog patients, particularly bone marrow transplant patients. Then the second half of my time there, I was a nurse educator and clinical nurse specialist in cardiology and vascular surgery. [It was a] very different world.

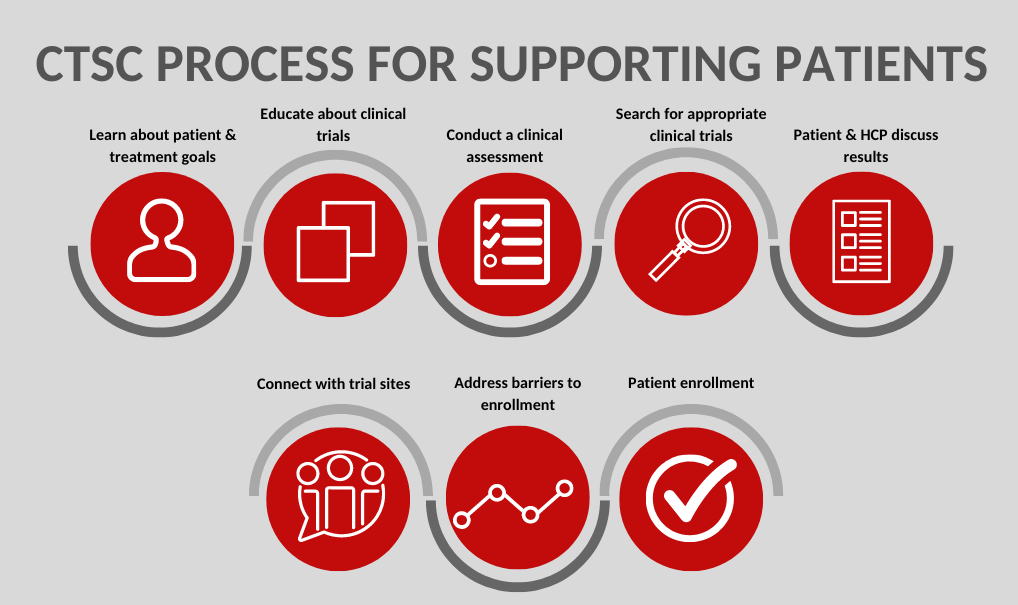

I came to LA just about 5 years ago in the Clinical Trial Support Center, and this team has grown so much in such a short amount of time. I feel really privileged to be part of this team. We’re a team of 11 nurse navigators with incredible nursing expertise in hematology and oncology. We work directly with patients, their families, and healthcare providers to help identify potential clinical trials and then overcome the barriers to enrollment.

Clinical Trial Information

Domenica, how did you learn about clinical trials?

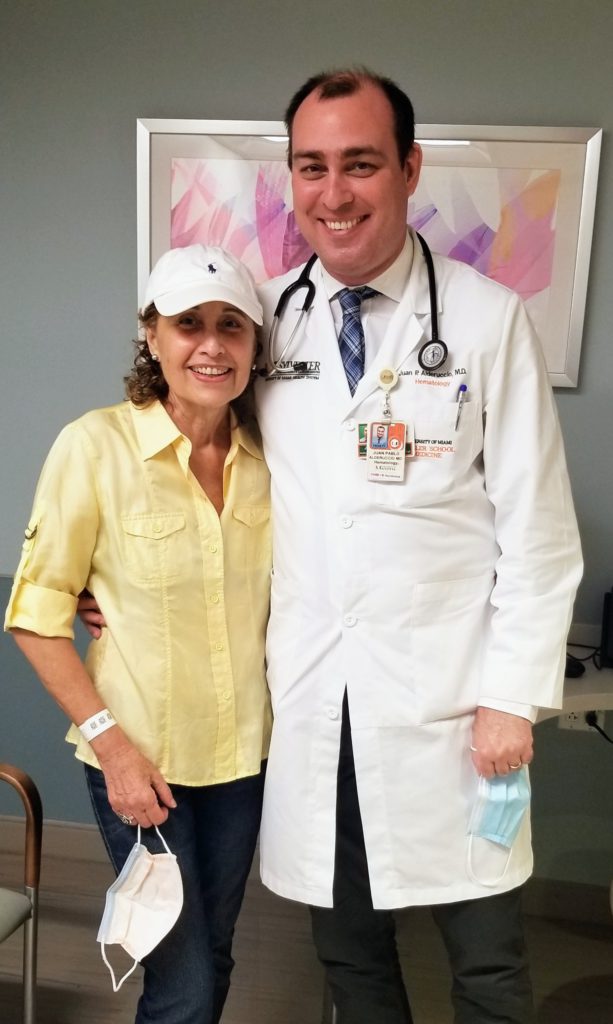

Domenica: In my case, my doctor is the one [who brought it up]. I knew about clinical trials, but I didn’t think I was going to be a candidate or that I was going to participate in a clinical trial. I moved from Mount Sinai Medical Center, and the doctor told me, “Listen, you have to go to Sylvester. I’m going to introduce you to a doctor, because they have lots of clinical trials. They have another kind of treatment that we don’t have.”

I appreciated that so much. When I got to Sylvester, the doctor talked to me about clinical trials. [I not only had] CLL, but at that time, it transformed into a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Richter transformation.

That is very aggressive and very difficult. I thought it was a great opportunity to be able to participate in something that is so new and something that can bring you hope to continue to fight.

Domenica, what questions did you have before participating in a clinical trial?

Domenica: The first time, you say, “Okay, what is going on? What is going to happen? What are you going to feel? Are you going to get a placebo?” Because that’s the typical thing that everyone says: “You’re going to get a placebo. You are going to be a guinea pig, etc., etc.” All the comments of your friends and family or whatever.

When I brought that question to my doctor, he told me, “In cancer, there are no placebos.” I felt much more comfortable because usually, if it’s another kind of illness, another kind of situation, they do placebos. In cancer, no. I felt much more comfortable going ahead and signing for the clinical trial. I think that that’s a great experience, knowing that you’re not going to be a guinea pig.

One [of my other] questions was, “What was the phase?” To be a little bit more sure what was going to happen and [to know] what I was getting into.

Leah, what top concerns do you hear from patients?

Leah: When we’re working with patients or family members, there are many different concerns like Domenica had, and there are many myths and misconceptions about clinical trials. A big part of what we do is help to educate and really clarify what clinical trials are.

As Domenica said, it’s really important to emphasize that first and foremost, safety is the number-one priority in any clinical trial. For a cancer clinical trial, a patient will never only receive a placebo. It would be completely unethical for a patient to receive only a placebo when there is other active therapy that could be given.

What happens is sometimes in later-phase clinical trials, there may be a placebo used, but it will always be in combination with whatever is considered the best approved therapy. Another misconception is when clinical trials are talked about, patients sometimes assume that must mean there is no hope for them.

Something else I really want to emphasize is that there are clinical trials for every stage of illness, whether it’s for patients who are newly diagnosed and have not yet received treatment, [or] if it’s for patients whose disease has not responded or come back after treatment. There are also clinical trials for people who are on maintenance therapy, into remission, and well into survivorship.

What we really work to do is to destigmatize the word “clinical trials.” We want clinical trials to be discussed at the time of diagnosis and during change in treatment plans as a potential option. It may not be the option for everyone at that moment, but the more we talk about clinical trials as an option, it’ll increase the awareness. It will increase the number of patients who enroll.

I think another really important thing to share is that 20% of cancer clinical trials in our country close not because the treatment didn’t work, but because they never get enough people to enroll. We really need to dispel these myths, these concerns, and increase awareness about what clinical trials really are.

There are very strict inclusion/exclusion criteria for clinical trials that involve prior lines of therapy. Again, the theme here is that cancer clinical trial participation is really the key step in advancing treatment, and it’s how we’re going to help bring treatments that work for people to the rest of the population. We really want the people who are participating in the trial to be representative of our diverse population. There are lots of really important aspects of increasing awareness.

Domenica, how did your doctor describe the clinical trial to you?

Domenica: When I spoke to the doctor, [he] explained everything about the clinical trial — how [it] works, all the things you have to do, the different tests, the different phases and of course, how you can be accepted or not.

As I said, I never went into a clinical trial and I never knew. Besides that, regarding the phases, I also think it’s very important. For me, it was very important to know that in my case, that first clinical trial and also the second one were in phase 2. I felt much more comfortable in a phase 2 trial than in a phase 1.

Leah, what are the phases of a clinical trial?

Leah: It’s a rigorous process. What’s important to understand is that any therapy that’s approved today, whether it’s chemotherapy or a different cancer therapy or even something over the counter that you can go pick up at CVS and Walgreens, at one point [it] was in a clinical trial.

Before a clinical trial even starts, the research begins in the lab setting. Researchers take either a new treatment, or maybe it’s a combination of drugs that have never been put together before, and they test it in either Petri dish or animals to really see if that is safe and promising in that setting.

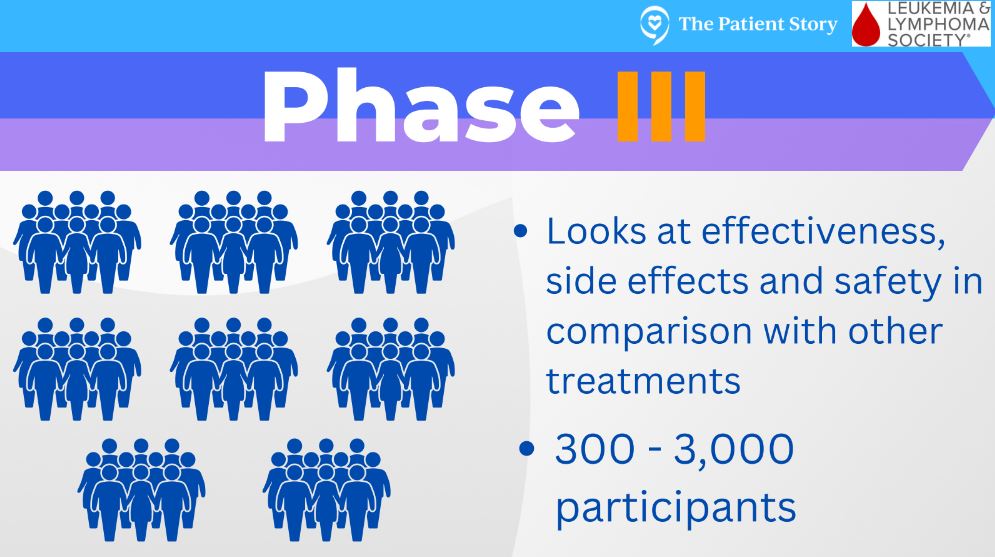

If it is, it can go through the very arduous process of becoming a formal clinical trial. The first phase of clinical trial, a phase 1, is considered first in human. It’s a very small number of patients, usually around 30. The goal of a phase 1 clinical trial is to determine what is the optimal dose, the highest dose with the least amount of side effects. Within that small group of patients, researchers give a group of patients a certain dose, and then if that is well tolerated, [they] give a different group of patients a higher dose and keep doing that until they determine what that optimal dose is.

After they’ve determined that, it can move into a phase 2 clinical trial. This phase has slightly more patients, somewhere around 100 or so. At this point, researchers say, “Okay, we have this new treatment that is safe, but does it actually work the way we had hoped?” Every clinical trial is set up differently in terms of what outcome measures it’s striving to meet.

It might be overall survival. It may be complete remission. It may be managing side effects or improving quality of life. Researchers are going to take this new optimal dose and give it to these patients to see if they can meet their outcomes. If they do, then that clinical trial can move on to a phase 3.

There are many more phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials than there are phase 3 for a couple of reasons. First, 20% of clinical trials unfortunately closed because they never had enough patients enroll. But then there are certain trials that closed because they didn’t determine that optimal dose, or they didn’t meet their outcome measures.

If a clinical trial does make it through those first 2 phases, it can go into a phase 3 clinical trial, which is where there are 2 groups of patients. The first group gets whatever is this new treatment, and then the other group of patients gets whatever is considered the best approved therapy.

At this point, researchers want to know, “Okay, is our new treatment as good, if not better, than what’s considered the gold standard or the approved therapy?” If it is, it can then pursue FDA approval.

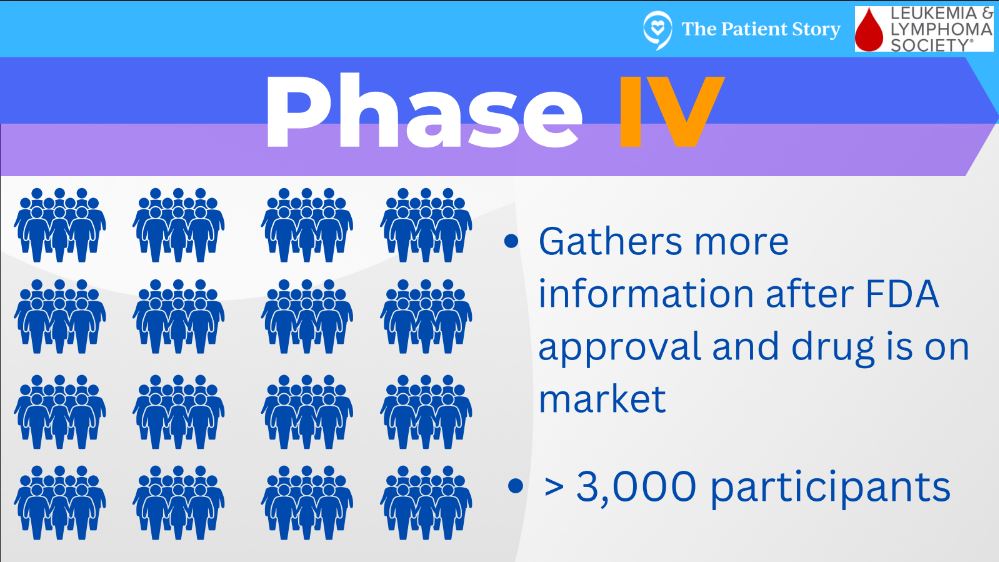

Phase 4 trials are when something has gone through the prior steps and becomes FDA approved. There can be a more long-term analysis of side effects and effectiveness, and that would be considered a phase 4 trial.

Domenica, how did your doctor recommend going somewhere else?

Domenica: I appreciated that so much and thank him so much because he saw it, and he knew he couldn’t do anything else for me. We started with the R-CHOP. That is the typical treatment for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and unfortunately it didn’t work after the third or fourth round of chemo, and that was it.

I moved to Sylvester Cancer Center, and the doctor told me about the clinical trials. It was a great discovery. At the beginning, I was going to do CAR-T, and that is why he sent me to Sylvester. But then when I got to Sylvester, the doctor said, “No, let’s wait for CAR-T and let’s try this clinical trial.”

Domenica, how did your doctors work together as a team?

Domenica: Something I didn’t mention before, [is getting a] second opinion. I think it’s very important because when you have this kind of cancer, if it’s so rare, it’s always good to have a second opinion to balance and see what’s going on in different centers. I have another doctor also in Memorial Sloan Kettering and he’s great, too.

Luckily, all the treatments we’ve been doing in Sylvester, they [all] agree. They always talk to each other and they communicate. They work as a team. That, I think, is super important for the patient.

At the beginning, when I was thinking about a second opinion, I said, “Oh my God, the doctor is going to be offended. I don’t know if I can do this.” But I said, “Well, listen, it’s my life.”

So I spoke to him. He told me, “Please, go ahead. If I was in your side, I would do exactly the same.” That kind of support of the doctors is so important for the patient — that you feel comfortable not only with your doctor, but in this case also having a second opinion.

Crissy, what resources are there to help guide patients?

Crissy: Right off the bat, I have to obviously mention LLS and the Clinical Trial Support Center. Our service is a 1-to-1 nurse-patient relationship. The majority of my patients, I work with for many weeks, months, and some even years. I’ve been working with Domenica for over a year.

It’s really unique to every patient and what their needs are. There are many other resources out there, too. There are other foundations you can reach out to for help and guidance.

The biggest thing I always tell patients is, you are your own advocate. It’s your life, not your doctor’s life, not your nurse’s life. It’s your life and so you have to be the one [who] advocates for yourself.

I want to point out [that] something I hear from a lot of patients is, “I don’t know if I want to send this trial search to my doctor. I don’t know if I want to share with them I’m looking elsewhere, or I’m scared to ask my doctor for a second opinion at another center.”

I’ve been working in cancer treatment for 10 years and I think you’d be hard-pressed to find a physician who is offended by that, because today’s patients are more informed than ever. Physicians appreciate that. Physicians are more than happy to help their patients seek second opinions elsewhere.

I think if you are with a physician who isn’t, that says something in and of itself and that maybe that relationship isn’t right for you. If you’re with a physician who doesn’t want what’s best for you, to get a second opinion somewhere else, I don’t know that that’s someone I would personally want on my team.

Clinical trial paperwork

Domenica: It was overwhelming at the beginning. The paperwork, as you said, [it’s thick]. To tell you the truth, I didn’t read the whole thing. I kind of went through [it], but I didn’t have [any] other option. I wanted to get into this clinical trial, so I signed the papers.

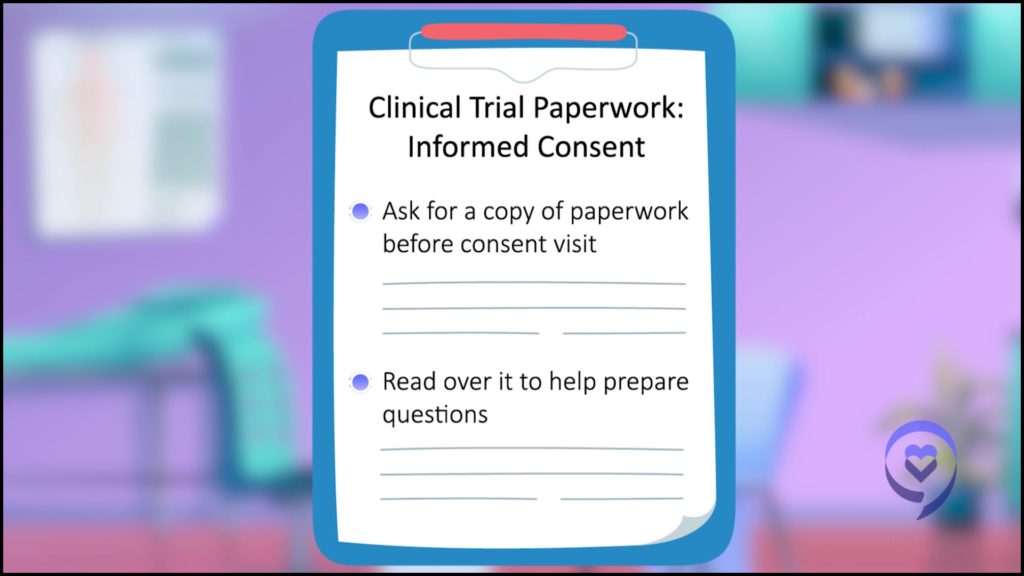

Crissy: One thing I always did when I was helping consent patients to clinical trials was, I always gave them the paperwork beforehand any time it was possible. Certainly, there are instances where a patient comes in, and you’re consenting them the day you found out that they progressed or they’re diagnosed.

However, in the majority of instances, we knew about a patient potentially coming in for a consult for a clinical trial, or we were switching gears and treatment. The day or two leading up to their visit, I would send them a copy of the consent. I always advise, “Read this over. Bring your highlighter. Write down questions. A lot of this is going to feel like there’s medical terminology, and it’s too much to understand. Highlight that, circle it, ask. Come with your questions.” Ask the question, “Can I get a copy of this before I sign it, and look it over?”

The other thing I stress to patients is while that is a very daunting and intimidating form, you can change your mind about participating at any time. Whether you sign the document there with your physician [or] you walk out of the clinic and say, “Oh, I change my mind. I don’t want to do all of that.”

You can change your mind at any point. Like I said, immediately after the visit, a week after the visit, 6 months, a year later. You can change your mind about participation in a clinical trial at any time.

The third big thing I like to advise patients to do is take someone with you to that visit. If it’s the visit to discuss the clinical trial, if it’s the visit to consent for the clinical trial, bring someone with you because you as the patient are going to be receiving so much information that you’re almost always going to walk out of that visit like, “Oh, I forgot to ask this, this, and this that I wanted to ask.”

If you bring someone with you, they know those questions you wanted to ask. They’re at the top of their mind and they bring them up. They’re also really good note takers. They might hear something you didn’t hear.

What kinds of treatments, tests and scans happen during the clinical trial?

Domenica: It’s overwhelming because there are so many tests involved. Of course, the typical blood test with all the specifics and PET-CT scans. You go through a bone marrow biopsy. I want to tell you something very interesting, because in the second clinical trial, they did a bone marrow biopsy and they didn’t find the Richter [transformation].

They called me and they said, “Well, if we don’t find it, I don’t think you can be in the clinical trial.” I freaked out, of course, but then they did a biopsy in another area in the breast. That is where I had the Richter, and they found it. They really work on finding all the things they need to follow the protocol of the clinical trial. That way, you can join. It’s incredible because then after that, you have to go every week.

That’s something I think everyone [needs] to know you have to go through: maybe the first and the second month [or] every week to do the follow-ups, the blood tests, [and] see how your body’s reacting with this new medicine that you have. After that, then it goes like once a month. I think it’s great because you feel that they are looking after you and you know what is happening inside your body. It’s very important.

Crissy, why do clinical trials need to do so many tests and scans?

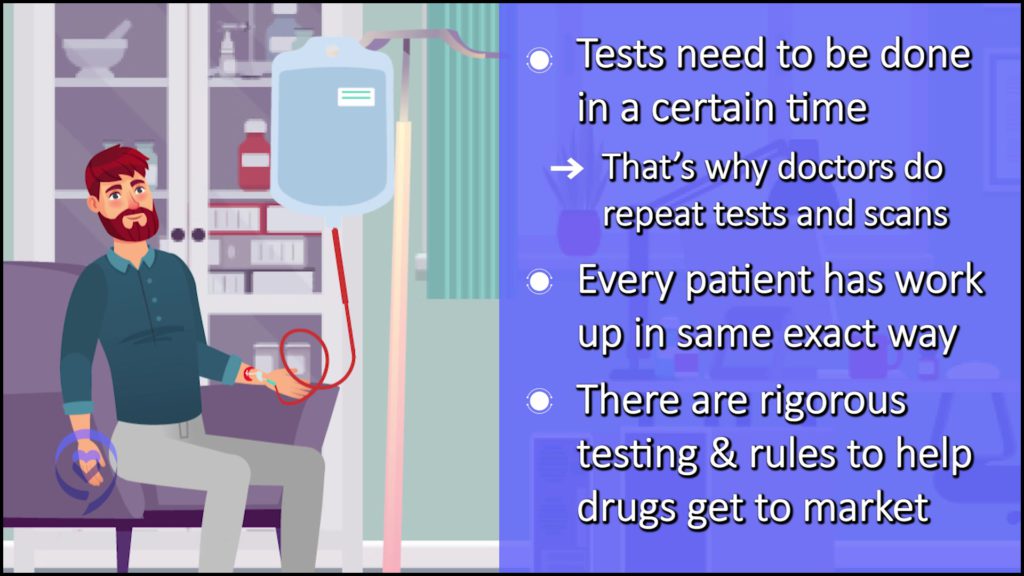

Crissy: A lot of times, the sponsor of a clinical trial needs fresh samples. Imaging needs to be done within so many days. Oftentimes it’s like 14 to 28 days. Patients told me, “Oh, I just had a scan.” It’s like, “Well, but it was 38 days and they require it within 28.”

Another reason they do this is so every single patient who’s on that clinical trial is worked up in the same exact way. [That way,] you’re comparing apples to apples and saying every patient got the same workup, the same treatment, [and] the same management on the clinical trial.

The [number-one] reason they do all of this rigorous testing is to keep patients safe. They want to make sure everything is as streamlined, the same and as safe as possible for every single patient. Another reason they do all of this testing is so that we can get more drugs to more patients.

That requires rigorous testing to make sure everyone is as equally fit and healthy to participate so that the clinical trial goes through as quickly and smoothly as possible. [Then] they can submit for FDA approval and get that drug on the market so that hundreds and thousands more patients can have access to it.

Clinical trial side effects

Domenica: The chemo, the radiation [and] everything is so hard [on] your body. When I found out that the clinical trial was a pill with very little side effects, it was a relief because definitely you don’t want to feel bad. For myself in particular, I didn’t have any side effects.

I lost my hair I don’t know how many times. It came back so many times. With this as a target therapy, it’s a completely different way of approaching your illness. I think this is a great way to join the future, because for me, this is the future. It’s a future of hope for all of us that have blood cancers and other cancers.

Travel and logistics for a clinical trial

Leah: Oftentimes, a clinical trial will take someone away from home frequently or for an extended period of time. Most clinical trials are happening in the large academic centers. For folks who don’t live in those areas, you’re talking about a lot of logistics to figure out.

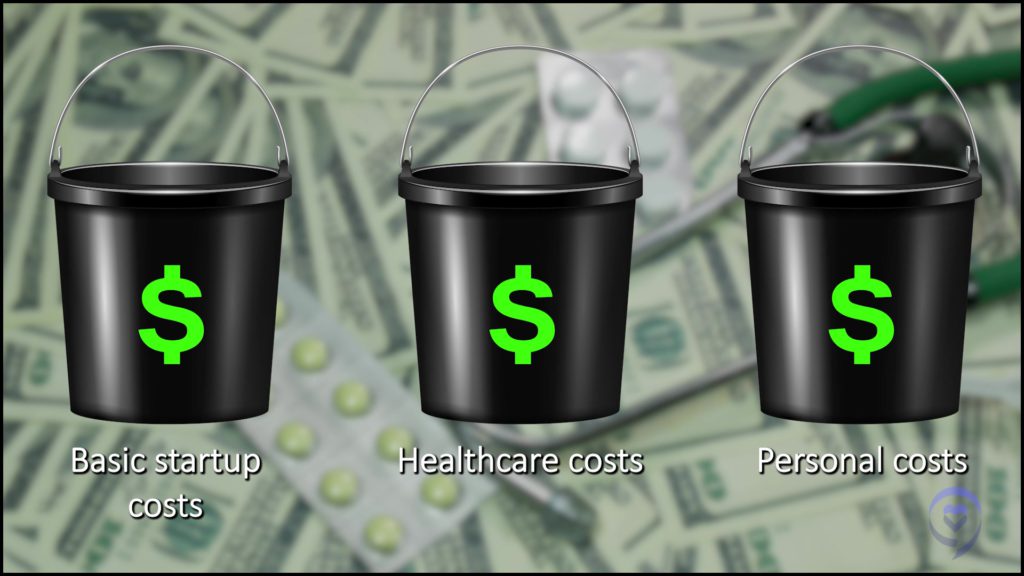

I tell people all the time, “Wanting to enroll in a clinical trial and actually enrolling is not a straight path.” There are just so many bumps in the road, and these logistics and finances are two huge bumps in the road. When we talk about the finances related to clinical trials, there’s really three buckets of cost.

The first bucket of cost is whatever is being studied, so either a new drug, a combination of drugs, a transplant or a CAR-T therapy. That new treatment being studied is typically covered. The cost of that is covered by whoever’s sponsoring the trial

Then you have the second bucket of cost, which is all the other healthcare-related costs — the scans, the bone marrow biopsies, labs, IV fluids or antibiotics when needed — need to either be billed to insurance or paid for out-of-pocket, which can be a significant cost.

The third bucket of cost are all of the other expenses related to participation: travel, airfare, carfare, gas, food, lodging for you and for a caregiver. The majority of that will be out-of-pocket expense. One of the questions we arm our patients with is, to go back to the study team and ask if the sponsor or the site has any money to help support covering for food, lodging, travel, etc.

What we have found is that oftentimes it takes building a patchwork quilt of resources to get people to a point where they can participate in that clinical trial. At LLS, we have some really incredible financial support programs for patients. We also look outside at other advocacy organizations to really try to build together a plan to make it possible. A challenge is certainly when patients don’t have health insurance. Many times a clinical trial, unfortunately, is not an option for the reasons that I mentioned.

What I want to also emphasize is that a clinical trial is not for everyone, for a multitude of different reasons. But if someone comes to our department interested in learning more and through that process, there’s a different type of treatment that is in their next best interest, whether it’s pursuing standard of care confidently or getting a medication through off-label or compassionate use, that nurse navigator is there to help you overcome whatever barriers there are to that treatment.

As nurses, we can be very savvy. It’s a little bit of detective work sometimes trying to piece together a plan to help somebody get to that optimal treatment, but this team is so able and ready to do that.

I think this is a great way to join the future, because for me, this is the future. It’s a future of hope for all of us that have blood cancers and other cancers.

Domenica

What was your experience with clinicaltrials.gov?

Domenica: I went to the site and it was crazy. There are I don’t know how many clinical trials for different cancers and different things, so you get lost. This is when Crissy comes and saves you. It’s amazing, but she knows everything. She knows all the clinical trials that are coming.

One thing that is very important that I also like to address is you always have to be ahead of the game. Don’t stay with this clinical trial. My husband and I used to call Crissy and say, “Okay, Crissy, we’re here, but what could be next?” Because you don’t know if it’s going to work. You don’t know how long it’s going to work. You always want to be prepared. Crissy is like a guardian angel because she does everything and makes finding the new clinical trial much easier.

Crissy: I want to say I am very thankful and blessed and honored to work with Domenica and her husband. They are incredible to work with. I get so excited every time my phone rings and I see that it’s them or they’re emailing me. Sometimes it’s to ask questions about her side effects she’s experiencing.

Sometimes it’s to update me on their trips to Peru or wherever cool place they’re traveling. Sometimes it’s to check in on how I’m doing. That’s kind of the beauty of this relationship in this service. Every relationship is totally different with patients, but patients get out of it what they want.

I do want to touch back on clinicaltrials.gov to reassure patients if you’ve ever been on that website and you felt down about yourself having trouble navigating it, understanding what they were saying — I just want to tell you that in my last job, I worked at a really large academic institution in a stem cell transplant clinic, and I helped physicians, some of the most brilliant physicians I’ve ever worked with, navigate that website at least weekly when they were looking for trials for their patients.

They had a lot of difficulty looking for what trials their patients might be eligible for on that website. Don’t feel down about yourself if you’re having a hard time navigating that. That’s really what our team is here to help patients do. [It’s] to not have to navigate that process on their own and everything else that comes with exploring clinical trials [and] participating in clinical trials

[It’s] to really hold your hand throughout that process, virtually or over the phone, to support you and guide you to make the best decisions for yourself through shared decision-making. Me helping you, you sharing the information with your physician and your family, and coming up with what is best for you and your situation.

I do want to encourage patients, too, if you’re interested in seeking our services, we’d be happy to help you navigate this very overwhelming territory.

Up until just a few years ago, our team was actually using clinicaltrials.gov to do our personalized searches for patients. It was felt that it was a tedious process that could definitely be streamlined and improved and so LLS poured a lot of resources into creating a proprietary database that only our team has access to.

It’s a website that sort of sits on top of clinicaltrials.gov and updates every 24 hours. To put simply, if it’s on clinicaltrials.gov, it’s also in our database. But then our database gives nurses and nurse practitioners who are on our team the ability to augment that information, update it, keep it more up to date, and really just put a lot more information about logistics.

If there’s published data or even unpublished data, we house that information in there. The more we know about a trial, the better we can help patients understand it, and the more we can help them figure out if it’s a good fit for them.

We’re constantly having meetings with physicians who are managing clinical trials, pharmaceutical sponsors of clinical trials, and the trial teams at sites to learn about the logistics. Is it a drug that a patient gets every week for 6 months, or is it a treatment that a patient gets once but they have to stay locally for 30 days? Is there lodging and travel assistance available?

Is there any published data in this space? Has there been any changes to the study that maybe aren’t on clinicaltrials.gov? Maybe they’re not enrolling this type of lymphoma anymore, but they are [with] this type of lymphoma. We are always constantly updating that site so all of our team has access to that information so we can better serve patients.

Domenica, you’re headed for another clinical trial

Domenica: Yes. I was lucky to find another clinical trial that the doctor introduced me to. [I’m] going to start the tests and everything maybe in a couple of weeks. I hope, it’s a successful clinical trial.

For me, a clinical trial means hope and many people don’t think about that. They think about the chemical part or the bothersome [things] caused by traveling or getting the tests or the follow-ups and everything.

But this is something that can give you hope to continue living and to continue fighting. I definitely don’t have any doubt. If there is another one, I will be in [it], because in my case, this is the only hope that I have.

Q&A from the Webinar

Q&A: Do you help outside the US?

Leah: The Clinical Trial Support Center at LLS works with patients in the US and Canada. I do want to emphasize we’re a completely free service as well. The challenge for international patients to receive care through a clinical trial in the US is related to finances and also establishing a place to be and visas. It’s a very complicated thing.

When we look at just the financial aspect of it, if someone does not have health insurance coverage, whether it’s commercial insurance or Medicare or Medicaid, the cost of the clinical trial will be out-of-pocket. We’re talking hundreds of thousands of dollars for the majority of clinical trials.

There are several healthcare institutions in the United States that do provide care for clinical trials, regardless of insurance coverage. That would be the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and St Jude’s for children. They only offer certain clinical trials. It can be challenging to also qualify for those clinical trials. By and large, for patients to come to the United States to participate in a clinical trial, it would be significantly expensive.

Q&A: How has the pandemic affected clinical trial administration?

Leah: One of the realities of COVID, and we’re still in this ongoing state of COVID, is that for many blood cancer patients, they actually have worse outcomes with COVID. There needs to be lots of provisions in place for these patients to safely travel.

First, I would encourage anybody to talk to their healthcare provider about boosters and COVID vaccines, because that’s a very important thing. We do know many of these folks are at increased risk with traveling. What we are trying to do is help advocate both in the policy space and when we’re meeting with sponsors to try to bring some of that care in a clinical trial closer to the patient.

One thing we did see in light of COVID is that some of these consults can be done virtually. That’s a great question to ask right from the start. Can some of the visits be done virtually? That would be a great option as well.

The other reality of COVID is that everything is that much more expensive. All the barriers to clinical trials that existed before COVID are still here. They’re just worse. It really takes that much more effort to try to get the resources to help people safely participate in a clinical trial.

Q&A: During the clinical, does the patient continue with regular visits with his or her oncologist?

Crissy: Anything that’s considered study-specific has to be done at the study site. If there’s study-specific scans, bone marrow biopsies, labs, something like that that needs to be drawn, or even a physical exam to be done with the physician, that has to take place at the trial site.

That’s something that is communicated up front when discussing the clinical trial. Your primary physician at your local oncology clinic is involved still and can see you in between those study visits, but anything that’s study-specific has to be done at the trial site.

Q&A: How do I overcome the fear of choosing incorrectly between a clinical trial and standard treatment?

Crissy: This is where a really strong physician-patient relationship comes into play. It’s really important to trust your physician. Trusting their judgment and their advice and arming yourself with as much information as you can to make the best decision.

Q&A: Was it hard to choose the clinical trial, Domenica?

Domenica: For me it was, “This is the way to go,” because of the rare cancer I have. I tried all the conventional treatments. Nothing worked. The last clinical trial that Crissy mentioned, I went on a trip, and I couldn’t believe I was having a normal life. I was hiking the mountains with my husband, 12,000 feet above sea level. I felt so strong and I couldn’t believe it and [it was] because of a clinical trial.

With the other treatments, besides [the fact] they didn’t work, you feel completely bad in every sense of the word. I really encourage people to try the clinical trial of course, with the support of your doctor. The less side effects you read the drug has, the better, because you want quality of life. Otherwise, it’s unbearable.

Webinar Slideshow

More Clinical Trial Experts

The Doctor Talk w/ Dr. Gasparetto & Dr. Richter

Role: Dr. Cristina Gasparetto (Duke) and Dr. Joshua Richter Mount Sinai discuss latest relapsed refractory multiple myeloma treatments

Saad Z. Usmani, MD

Dr. Saad Usmani, Chief of Myeloma Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering, talks about CAR T-cell therapy, bispecific antibodies, novel therapies and combination therapies.

Polycythemia Vera (2022)

In segment 2 of our conversation with Srdan Vertsovsek, MD, PhD of MD Anderson, he shares the latest on research for polycythemia vera or PV treatments.