A New Era in Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Treatment Options

Replay Video Now Live

Don’t just read her interview – watch above. Dr. Moore will help break down some of the more complex ideas regarding ovarian cancer treatment. Go beyond the words and hear from an oncologist who treats patients every day.

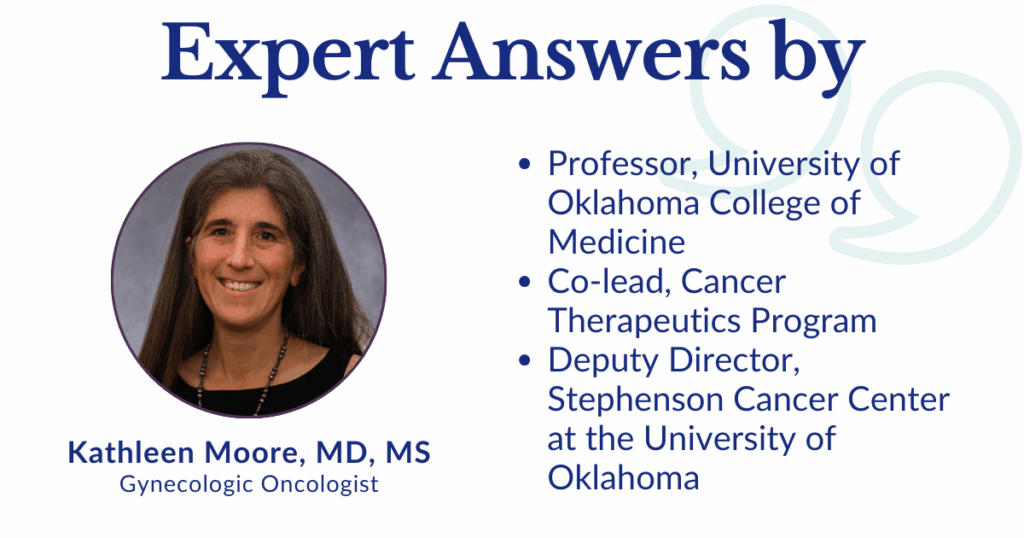

Navigating a diagnosis of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer can feel overwhelming, but recent advancements and clinical trials are bringing new hope and more personalized treatment paths. This program offers empowering information on the latest therapies. We are joined by Dr. Kathleen Moore, an internationally recognized leader in gynecologic oncology from the Stephenson Cancer Center, who breaks down what you need to know about where treatment is heading.

What to expect:

- Understand Platinum Resistance: Learn what this diagnosis means and how it shapes your treatment options

- Discover Emerging Therapies: Hear about the promise of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and other new drugs that are improving survival

- Learn About Biomarker Testing: Find out how tests for markers like folate receptor and BRCA can unlock personalized treatment paths

- Explore Clinical Trials: Get clear answers about how to find and access clinical trials for new and promising ovarian cancer treatments

- Personalize Your Care: Learn how oncologists are sequencing therapies to create more effective, individualized treatment plans

- Advocate for Yourself: Gain insights on communicating with your doctor and the questions to ask to ensure you get the best care

Navigating a diagnosis of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer can feel overwhelming, but recent advancements and clinical trials are bringing new hope and more personalized treatment paths. This program offers empowering information on the latest therapies. We are joined by Dr. Kathleen Moore, an internationally recognized leader in gynecologic oncology from the Stephenson Cancer Center, who breaks down what you need to know about where treatment is heading.

What to expect:

- Understand Platinum Resistance: Learn what this diagnosis means and how it shapes your treatment options

- Discover Emerging Therapies: Hear about the promise of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and other new drugs that are improving survival

- Learn About Biomarker Testing: Find out how tests for markers like folate receptor and BRCA can unlock personalized treatment paths

- Explore Clinical Trials: Get clear answers about how to find and access clinical trials for new and promising ovarian cancer treatments

- Personalize Your Care: Learn how oncologists are sequencing therapies to create more effective, individualized treatment plans

- Advocate for Yourself: Gain insights on communicating with your doctor and the questions to ask to ensure you get the best care

Thank you to AbbVie for supporting our independent patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Introduction

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Welcome! I’m so glad that you could join this program. There’s a lot happening in this space and we hope that you walk away with more knowledge and more questions to ask your healthcare team.

My name is Stephanie Chuang. I’m the founder of The Patient Story, but more importantly, I had my own cancer diagnosis. In my case, it was non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a blood cancer. I remember how confusing and overwhelming it was when there was so much information getting thrown my way and that was part of the genesis of The Patient Story. We try to help others find community and humanize information after a cancer diagnosis. We do that through educational conversations and amazing in-depth patient stories and videos, thanks to the amazing people who have volunteered their stories. You can find hundreds of those on ThePatientStory.com.

We want to thank our sponsor, AbbVie, for supporting this program, which helps us bring more of these programs to you. We want to note that The Patient Story maintains full editorial control. While we hope this conversation is helpful, this is not a substitute for medical advice, so please consult your healthcare team when making decisions.

We want to know how you feel because we want to do better and do more for you and your support system. What would you like to hear more about? What can we do better? Please let us know, as we’d love to hear your voice.

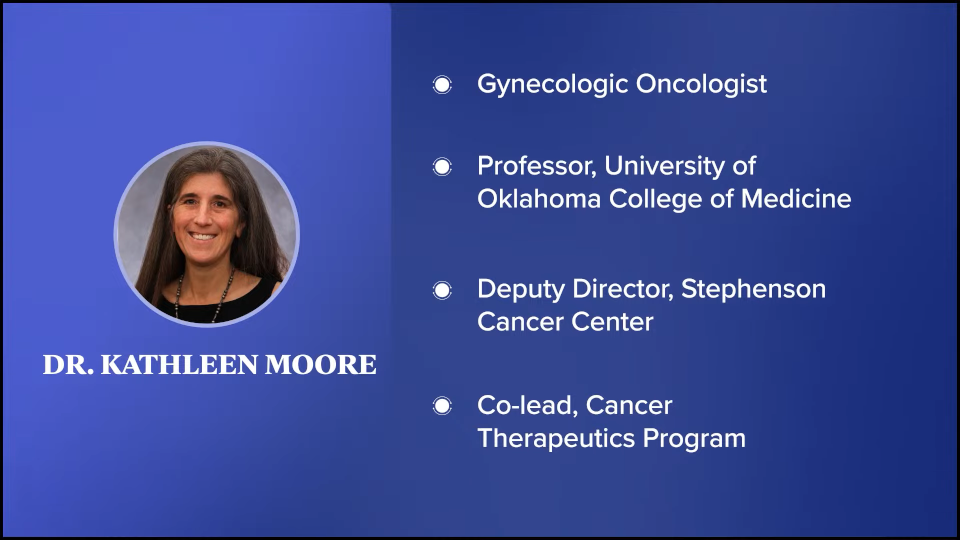

I’m so excited to be joined by Dr. Kathleen Moore. She’s an internationally recognized leader in gynecologic oncology and clinical trials. Dr. Moore is a professor at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine. She’s also the deputy director of the Stephenson Cancer Center and the co-lead of the Cancer Therapeutics Program. She’s also a favorite of patient advocates in this space.

Dr. Moore, thank you so much for joining us at The Patient Story. You clearly spend so much time not just with your own patients and in research, but trying to help patients and care partners everywhere. What motivates you to try and help be that bridge to patients and care partners everywhere?

Dr. Kathleen Moore: Thank you for having me. I’m very excited to be here. What drives me and a lot of us who do clinical research for patients with cancer comes from respecting the accomplishments that have happened over the last few decades across hematologic and solid tumors. We’re grateful for those, but we know, especially in the ovarian cancer space, that we have a long way to go.

Dr. Kathleen Moore: Thank you for having me. I’m very excited to be here. What drives me and a lot of us who do clinical research for patients with cancer comes from respecting the accomplishments that have happened over the last few decades across hematologic and solid tumors. We’re grateful for those, but we know, especially in the ovarian cancer space, that we have a long way to go.

We have not cracked the nut on screening. We have not perfected universal genetic testing, risk-reducing surgery, and cascade testing, which are things that could prevent cancer. We are not curing enough patients in the frontline, so that they get treated and never recur. We’re not there yet. We’re better, but we’re not there yet. We have made big advances in the recurrent setting. We have more things that work. They’re not perfect, but they’re better tolerated and we’re starting to think about sequencing. There’s a lot to be excited about, but we’re not there yet.

One of the big things is that overall survival has improved for ovarian cancer. There’s been a little bit of a drop in incidence and that’s probably because of increased opportunistic salpingectomy and some cascade testing and risk-reducing surgeries. We see a little drop in incidence, but not enough to explain the improvement in overall survival and that is coming from the development of therapeutics. There is a light to talk about, but there’s also a lot to do and that’s where research comes into play.

We have to get novel therapeutics, screening opportunities, quality of life, and survivorship interventions into clinical trials. It’s important for patients to get access to clinical trials, which does change the face of what clinical trials look like or should moving forward. Taking them out of the “ivory towers” and into the community is one of the big things that drives a lot of us right now in this space and we’re starting to see that come to fruition.

Stephanie: I love all that. Thank you so much for the work that you do and for synthesizing the work that you’re focused on.

Talking to Ovarian Cancer Patients About Their Prognosis

Stephanie: Ovarian cancer is moving in the right direction in terms of the research, but it’s still not quite there yet. With screening, we know that a lot of women are getting diagnosed at an advanced stage. When you’re seeing patients for the first time, trying to help orient them after they’ve just been told they have cancer, and after finding out it’s ovarian cancer, how do you try to communicate to them in the most human way possible and in less technical terms that this is what we’re looking at and how we’re going to try and approach this?

Dr. Moore: Any diagnosis of cancer is such a big diagnosis for people. I’m going to be honest. The Lancet is doing an ovarian cancer commission, which I’m co-chairing with Isabelle Ray-Coquard from France. We’re doing that right now and it’s testament to the increasing interest and importance being placed on ovarian cancer. Over the next two years, we’re going to try and define the research policy and patient-centered survivorship opportunities that hopefully will drive the global agenda around ovarian cancer in the future. As a part of that, every time you do something like this, you’re surrounded by people who are smarter than you. We have an amazing patient advocate lead in Annwen Jones OBE from the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition.

A few months ago, she said something to me that’s already changed how I interface and interact with my patients. She brought up something from her research that I’d never thought about, but is so true. She said, “The United States is no different. Women diagnosed with ovarian cancer often have been in the community seeking help for symptoms for months. They’ve been bounced around primary care providers, urologists, gastroenterologists, or psychiatrists, but no one ever does a pelvic exam or asks some of these questions.”

What Annwen brought up is that a lot of times, when our patients present, you meet them, and we finally say, “Here’s the diagnosis and this is what we’re going to do. These are all the things and we have a plan,” I’ve completely neglected to address what Annwen says is almost like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Patients have been presenting for months or sometimes even longer, and they’re either not being believed, being bounced around, or given this or that medicine. Don’t even get me started on all the mistrust out and people taking weird things.

Patients arrive at our door with some varying state of trauma that I don’t know if we’ve ever addressed upfront. But I’m trying to start acknowledging that at least. I don’t know what I’m going to do about it, but I acknowledge that I know it has been a journey and here we are. We have the diagnosis and now we’re going to move forward. But I think we’ve neglected that piece. I had never thought about it until I talked to a patient. Patient advocacy, patient involvement, and research are critical for all of these reasons and something we have to talk about.

With that context in mind, it comes down to getting the right diagnosis. We’re doing an increasing amount of molecular profiling, sometimes right out of the gate, to better define maintenance therapies. But from the onset, when patients are presenting, they usually feel terrible. They have anxiety, haven’t been able to eat, have pain, and are nauseated, so the focus is getting the diagnosis and presenting optimism. When we’re talking about high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), the likelihood is that this is going to respond and they’re going to feel better pretty quickly.

Timing of surgery and all of those things need to be adjudicated based on imaging, patient fitness, and other factors. But right out of the gate, once you have the diagnosis, it’s about trying to present a face of optimism and expecting the cancer to respond, and then we’ll get to all the other layers in subsequent visits. Otherwise, you completely overwhelm a person with what’s coming.

Stephanie: Thank you for acknowledging that gap, which I think is across the board. Providers are there, and you’ve been doing research and trying to help people at that point by letting them know the plan of action. I appreciate the acknowledgment of whether they are in a space where people can take it all in. It’s a lot and it’s a balance or a dance. It’s hard. There’s no black or white. But I thought that acknowledgment itself does wonders because it helps with communication. Thank you so much, Dr. Moore, for that.

What are the Common Symptoms of Ovarian Cancer?

Stephanie: You’ve mentioned something that we’ve also heard from a lot of patients, which is it’s a hard path to diagnosis. Months and months of trying to figure it out and being told either it’s in your head or something else. What are the typical symptoms that they’re presenting? Are there any other contextual clues or questions that people can bring to light to try and help get to a diagnosis faster?

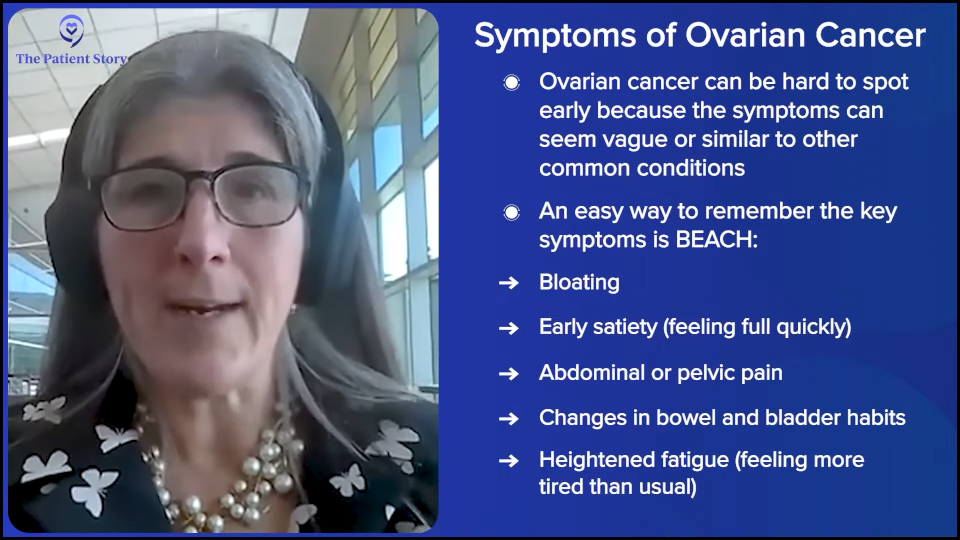

Dr. Moore: That’s what we’re working on. There are women in the field — Dr. Barbara Goff at the University of Washington, Dr. Joan Walker at the University of Oklahoma, and Dr. Karen Lu at Moffitt Cancer Center, who have been preaching this for decades. There is a set of symptoms, which are very nonspecific. People call them the BEACH symptoms, but you can probably assign this to a number of diagnoses. It’s bloating, changes in eating habits (early satiety), abdominal pain, changes in bowel or bladder habits, and heightened fatigue. It’s a very nondescript set of symptoms that usually isn’t ovarian cancer, but it can be, so development of these symptoms that don’t go away, persists for weeks, or worsening warrants an evaluation.

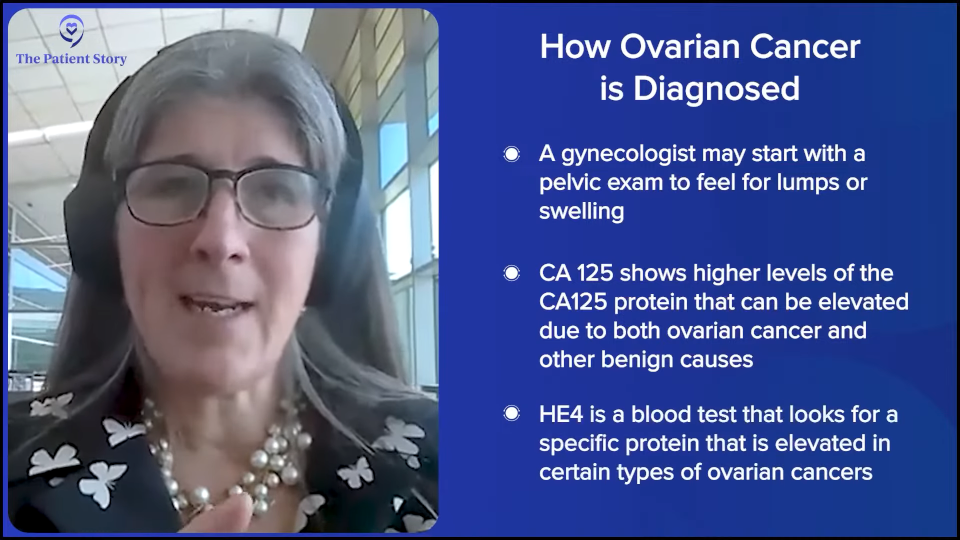

One of the things we’ve been trying to preach is that evaluation has to involve a pelvic exam. Some patients who have had a hysterectomy think that their ovaries are gone, but they’re not. People say, “I had a total hysterectomy.” That’s not even a thing, so they think they don’t have ovaries, but someone left them and never told them. You see this all the time. There are peritoneal cancers that look like ovarian cancer and could act the same way. Having a skilled gynecologist to do a good pelvic exam and patient history sometimes can elucidate some of these findings.

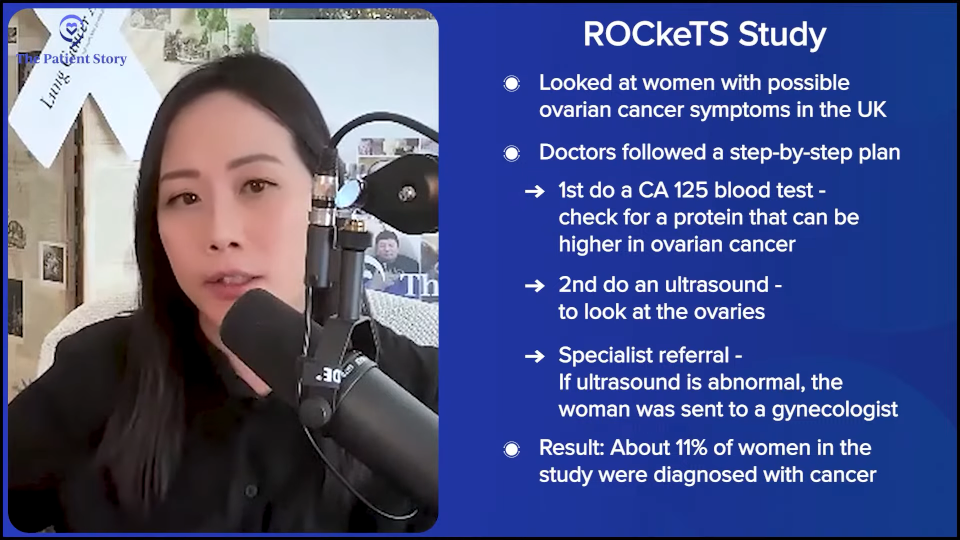

There’s been an understanding that there is this prodrome of symptoms. We’ve just never been able to turn it into an algorithm that pushes a woman into the right diagnostic pathway quickly, at least in the United States. In the UK, Sudha Sundar did a study called the ROCkeTS study, which is published. This is where research is powerful. The UK has socialized medicine. You can feel all the feels about that. There are good things and bad things about it. One of the bad things in many settings is that there are delays in care and limited access. They focus on primary care, which is a good thing and we can learn something from that. But when people have a problem, sometimes there are delays.

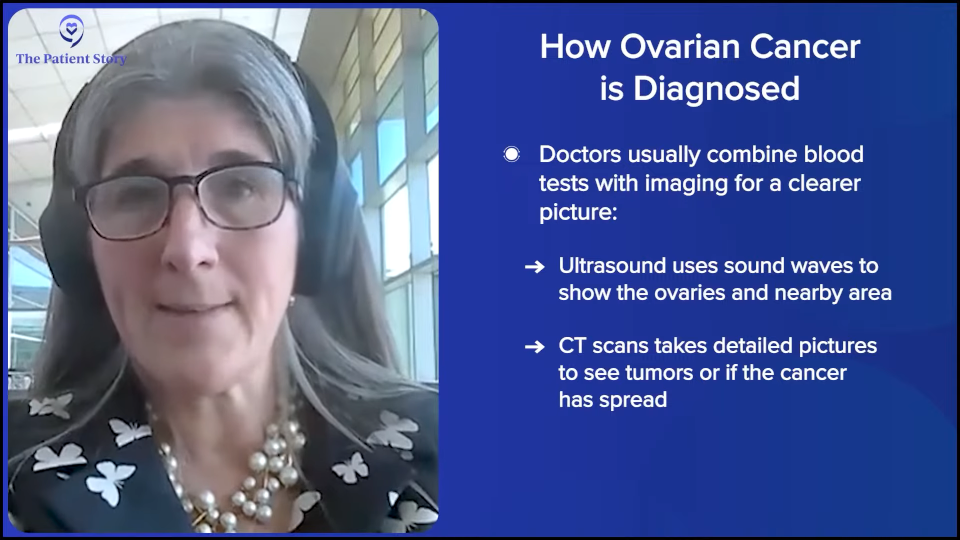

They had an algorithm and she put this pathway to the test. If a patient presented to their general practitioner (GP) with any of these symptoms and of a certain age, they got a CA-125 test. If the results are elevated, they got an ultrasound and a referral. The referral happened right away, so they got right in to a gynecologist and they did all this imaging.

Out of about 2,000 symptomatic women, they found cancer in 11%, which is quite high. Now, they weren’t all ovarian cancers, but a lot was. When they looked at the distribution, they weren’t finding stage 1 cancers, but they were finding lower volume tumors and a lower volume tumor can get to the operating room (OR) as opposed to doing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. If we catch these tumors at low volumes, do our best molecular profiling, and throw our best therapies, could you see that transforming into more cures? That’s the question. Is it getting earlier diagnosis, but people still pass away the same day? Or do you transform someone not too recur? I believe in the latter. It shows that if you put algorithms in place, you can expedite that workup. I love that piece.

Think about what’s happening now with artificial intelligence (AI) in all of our medical systems. We have Epic and I know it’s not the only system, but almost everyone has Epic. You could see putting these algorithms into place and driving the diagnostic workup in a way that fills that gap with symptom recognition.

They’re even doing something in the UK with pharmacy cards, which I don’t think we ever could do in the US. If a patient comes in and starts getting antacids, laxatives, or medication that they haven’t gotten before, the card triggers a notification that says, “Hey, do you need a colonoscopy?” They’re trying to come at it from all these very unique ways that we can learn from. We know the symptoms are there and despite very negative opinions about electronic medical systems, this is one of the places where you could use it for good. I’m excited to see some of those opportunities coming and push patients into earlier diagnoses.

We’re not going to catch it at stage 1 because it’s not usually symptomatic at that stage, but we can catch a lot earlier. Even if it doesn’t change survival, which I think it will, it changes how aggressive the surgery has to be, which makes it safer. You don’t have to do three bowel resections. If I can just take out the uterus, ovaries, and omentum as opposed to having a massive surgery, then that’s safer for the patient. There will be less trauma from an ostomy. It’s time to bring back the symptom algorithm and start trying to put it into action. We’re definitely standing on the shoulders of the giants who’ve been working on this for decades, but it’s time to start preaching that.

Stephanie: That’s so much promise. The ROCkeTS study was done in the UK and showed that there’s promise when you’re able to put some sort of algorithm in place. You mentioned something about finding a skilled gynecologist for a pelvic exam. When you said that, it made me think. Are there different levels of specialists in gynecology before you get to an oncologist?

Dr. Moore: There’s always a lot of heterogeneity. Speaking for the US and the US training, typically, OB-GYNs are also delivering babies and taking care of women who are in various stages of pre- and post-menopause. They’re highly skilled to do a pelvic exam, they know what to do with CA-125, and they can refer very quickly because they’re high volume. They know what’s normal and not normal. I don’t think there’s a lot of variation there.

There are family practitioners who do a ton of gynecology and are very skilled, and then there are general practitioners that do a pelvic exam here and there. They’re great at everything else, so I’m not throwing shade at my colleagues, but a board-certified OB-GYN is well-suited to do a pelvic exam. Patients who are done having kids or have had what they think is a total hysterectomy stop going. They think they don’t need it anymore. There’s still a role for helping us to find things early.

How Biomarkers Affect Treatment

Stephanie: You talked about some of the histological subtypes. What are the different patient profiles or markers that you’re looking at in terms of how you’re thinking about what treatment would work best for each patient? In general, how are you looking at that and how do they matter when you’re deciding treatment?

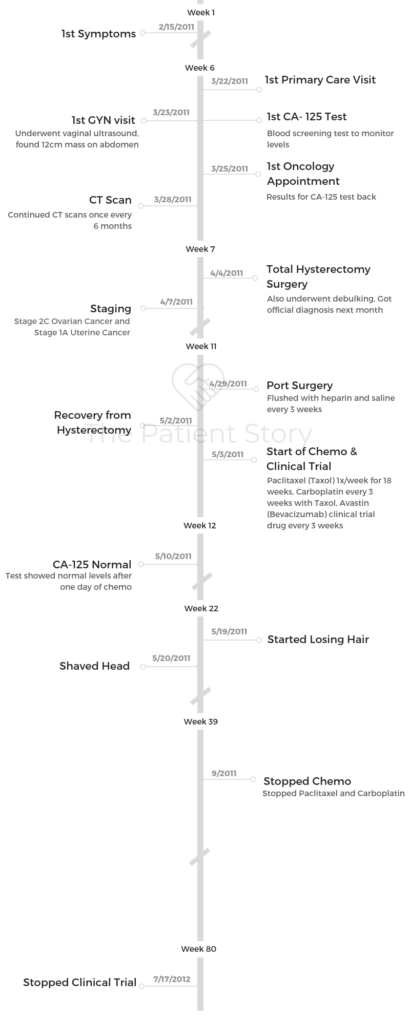

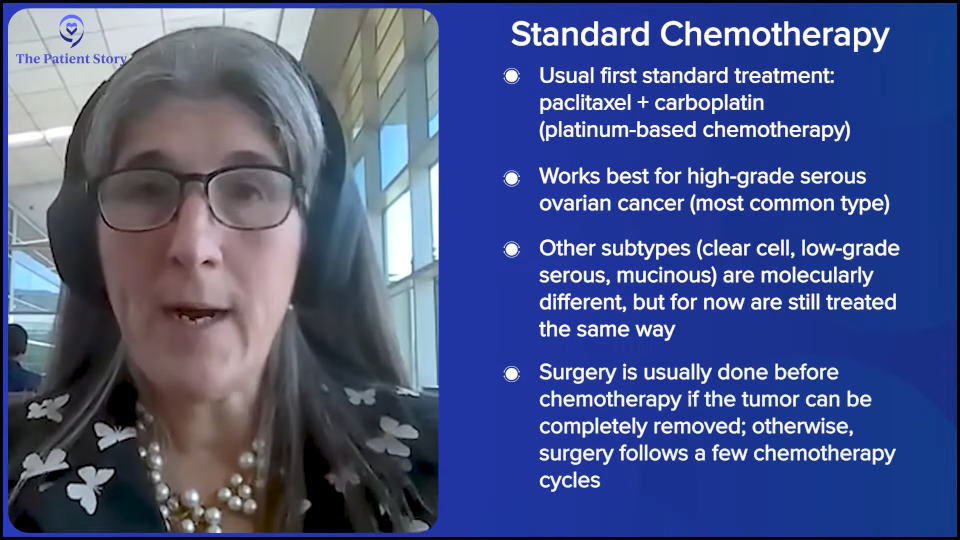

Dr. Moore: On the frontline, the standard of care is still paclitaxel (Taxol) and carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata). That’s the chemotherapy backbone. We call carboplatin platinum, so platinum-based chemotherapy. It’s the key drug for high-grade serous ovarian cancer, which is the most common type.

Other types of ovarian cancer are epithelial ovarian cancer, which is the common type of ovarian cancer, or clear cell, which is about 10% of cases and is a very different molecular tumor from high-grade serous. We treat it the same for now, but we’re starting to evolve. Low-grade serous sounds friendlier, but it’s a completely different molecular subtype as well. Mucinous is very rare and a challenge for us to treat. Since then and until now, if someone presents with advanced disease, we’re giving paclitaxel (Taxol) and carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata). That hasn’t changed, but it will in the future.

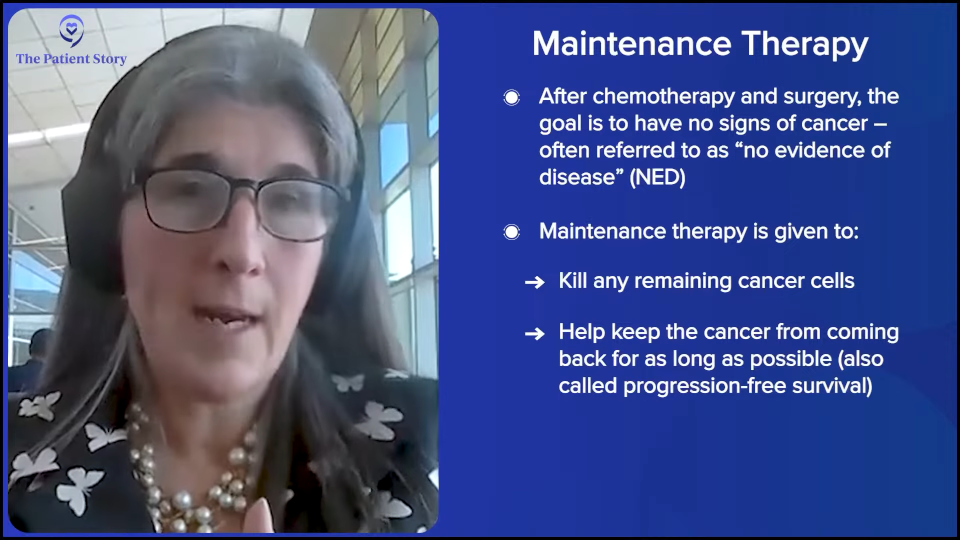

The change, difference, and differentiation come with maintenance. We give six or eight cycles of chemotherapy. Ideally, we do surgery. We like to do it first, if we think we can get all visible tumors out. If we can’t, then we do it after a few cycles of chemo so that we can get it all out. Then we’ll do a sandwich.

There’s this concept of maintenance and maintenance means we’ve hopefully gotten a patient to the point of no visible disease, which we call no evidence of disease (NED), and then we want to put them on a medication that’s well-tolerated and ideally mops up any residual clones so that they’re cured. If not cured, then holds the cancer off for a long period of time, so there’s a longer progression-free survival (PFS) or the time from finishing chemo until such time that the cancer might come back.

For a long time, we used bevacizumab and we still use it. We call it bev. It’s an IV drug that’s given every three weeks and blocks one of the ways that tumors make blood vessels to feed the tumor to starve it. It’s a good drug and prolongs progression-free survival. It doesn’t impact cure or overall survival, but it’s a good drug and makes chemo work better. Sometimes if someone has a lot of fluid in their belly or around their lungs, like ascites or pleural effusion, we’ll add bevacizumab to the chemo and it dries it up quickly usually so people feel better.

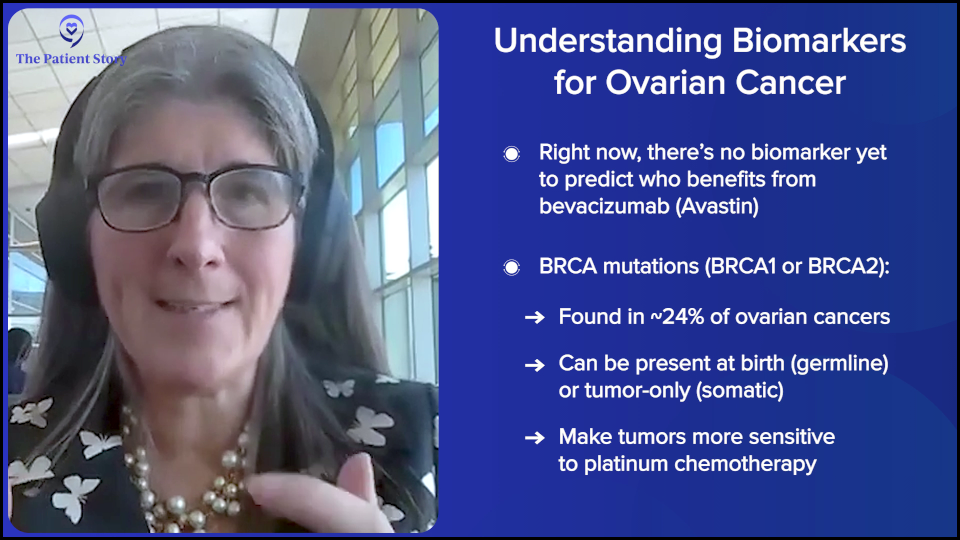

With the increasing understanding of the tumor’s molecular profile, we’re starting to get smarter. There’s no biomarker for who benefits from bevacizumab and who doesn’t, despite a lot of work by a lot of my smart colleagues. We can’t say, “This is going to work great for you. This is going to help you.” We give it to everyone. With high-grade serous ovarian cancer, we understand that some of them have a BRCA mutation, which is in about 24% of ovarian cancer. It can be something you’re born with, which is called germline, and caused the cancer, or something that the tumor just has, which is called somatic and means it’s not heritable. But it’s the same mutation.

That mutation plus other changes in the tumor render the tumor vulnerable to how it fixes its DNA. It’s growing fast. It has to duplicate its DNA. There are lots of errors made in every cell that doubles. Tumors aren’t good at fixing those errors. They rely on a bunch of proteins. BRCA is a protein that fixes double-stranded DNA breaks, so patients with a BRCA mutation, that’s what caused their cancer, but it also makes that cancer vulnerable to a therapy that damages DNA, like platinum.

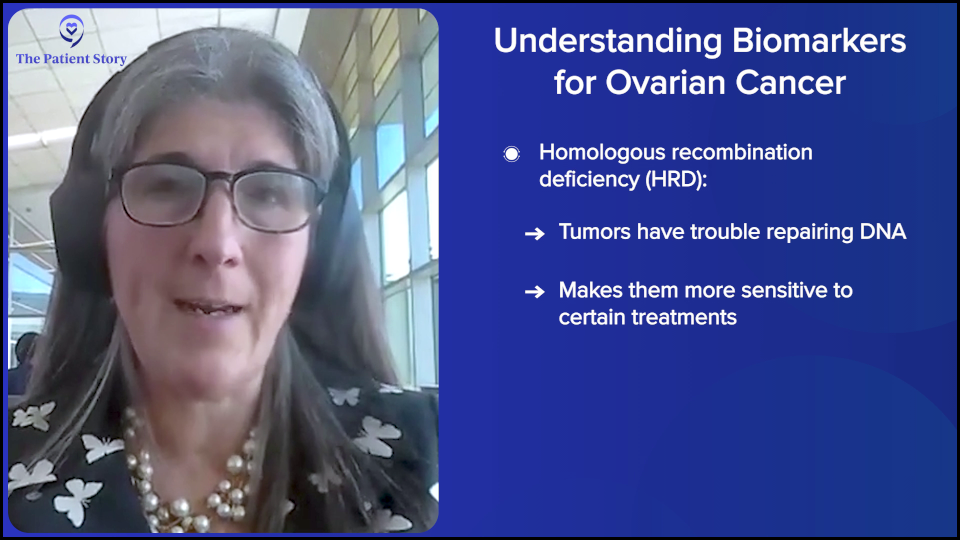

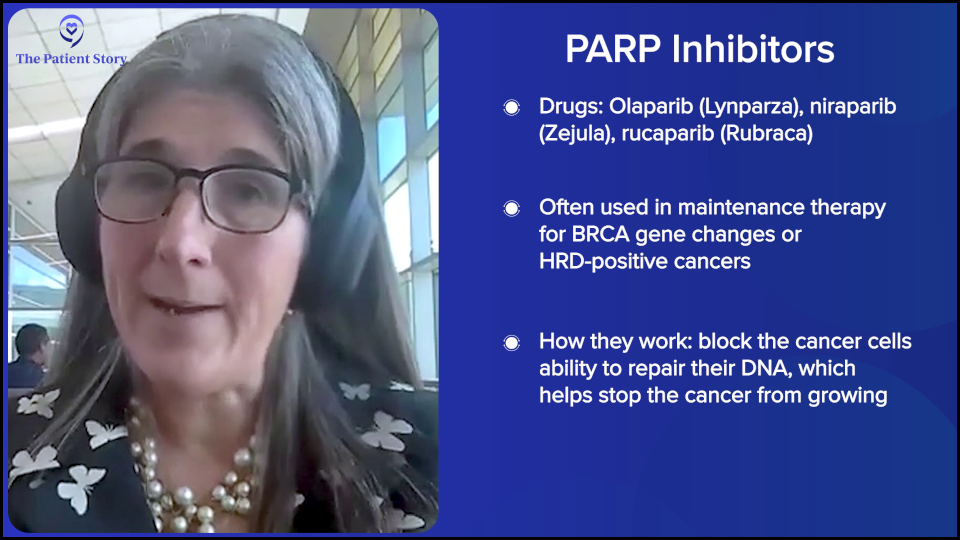

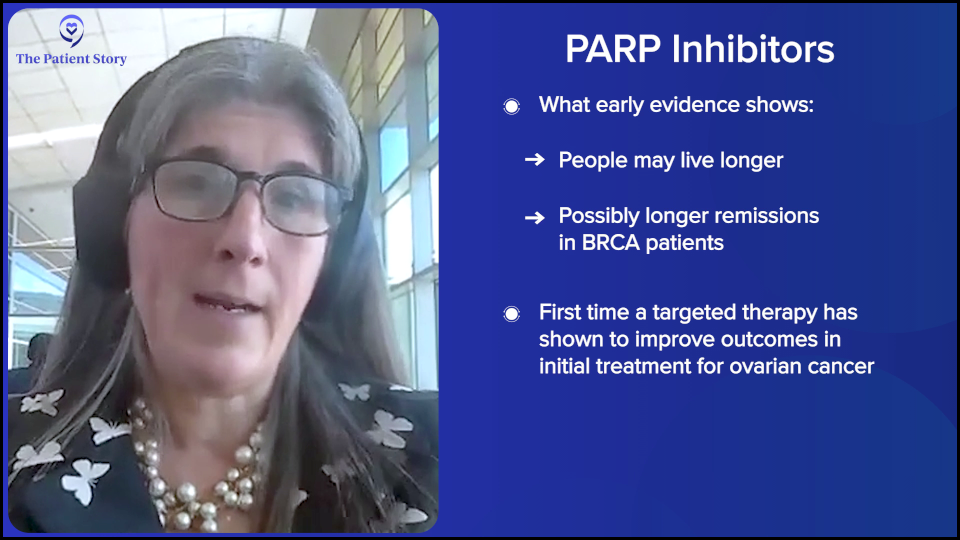

There are other changes in the tumor called homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), which means that it struggles to fix its DNA. In that setting, we brought in PARP inhibitors, like olaparib (Lynparza), niraparib (Zejula), and rucaparib (Rubraca), as maintenance. When we did that, we started to see evidence — not final yet because we’re still following patients — but it looks like we’re improving overall survival. In a BRCA population, it looks like there may be a higher cure fraction.

We have moved more patients into the never recur group and that’s what you want. You want to hit it hard and not have them recur, so we’re seeing evidence of that. We can’t say it’s final because we’re still following patients, but I’m pretty sure we’re going to be able to call it at some point. That’s important because it’s the first instance in ovarian cancer where we’ve used targeted therapy in the right population and in the right setting of front-line maintenance, and it has started to move the needle on overall survival, which we’ve never done, and cure. You’re going to see that.

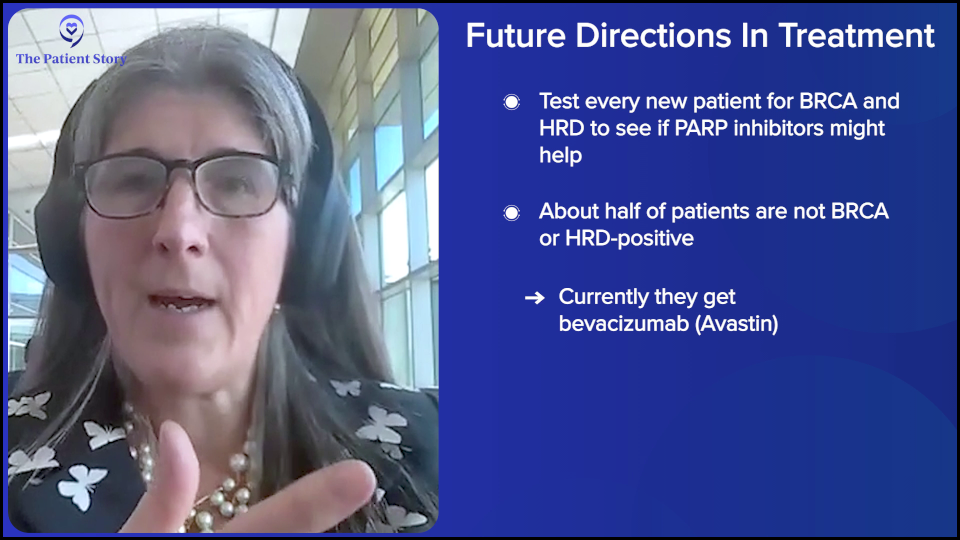

When we have a newly diagnosed individual, we want the diagnosis to be correct. We want to know BRCA, one hundred percent. And we want to know homologous recombination deficiency. We’re using PARP inhibitors or at least offer it to them. Patients can decide or not, as they’re autonomous beings, of course, but we want to make sure that we’re offering it.

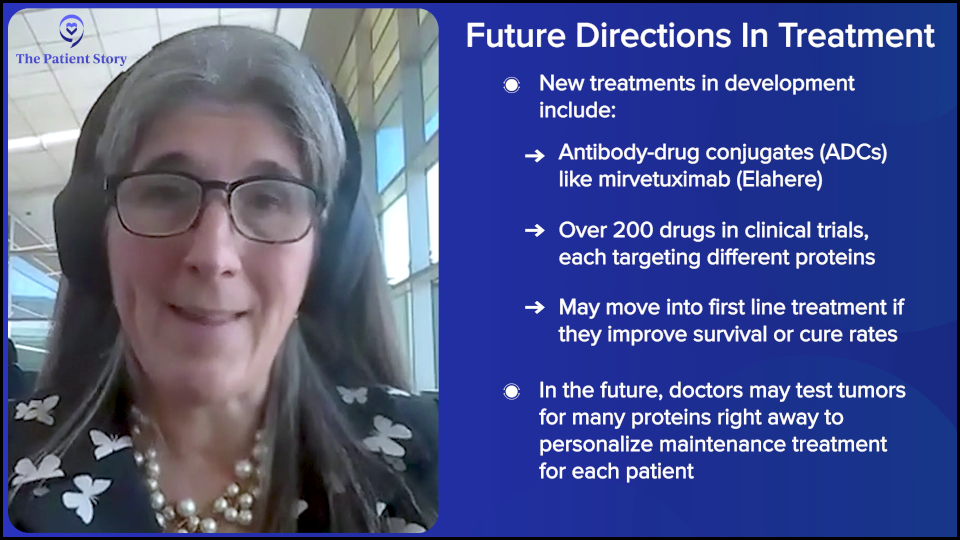

You’re going to see more of these biomarkers coming in as novel drugs are being developed for tumors that are not homologous recombination deficient, which is half. The majority of ovarian cancer patients aren’t BRCA or HRD, and they have the option of bevacizumab right now, but we’re seeing antibody-drug conjugates, like mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere). There are 200 in development and they all target a different protein. We’re starting to test for those. We’re seeing clinical trials move those drugs into the frontline. The question is going to be: does it cure more patients? Does it improve overall survival? If it does, we’re going to be testing for all those proteins right out of the gate because it’s going to define maintenance right out of the gate. We’re not there yet; the studies are just launching.

What is Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer?

Stephanie: You talked about the platinum-based therapies and almost everyone’s going through that. What does it mean to be platinum-resistant or have platinum-resistant disease? And how many people are we talking about?

Dr. Moore: This is another place where there are regulatory answers and then there’s what we think is going to happen and where we’re moving.

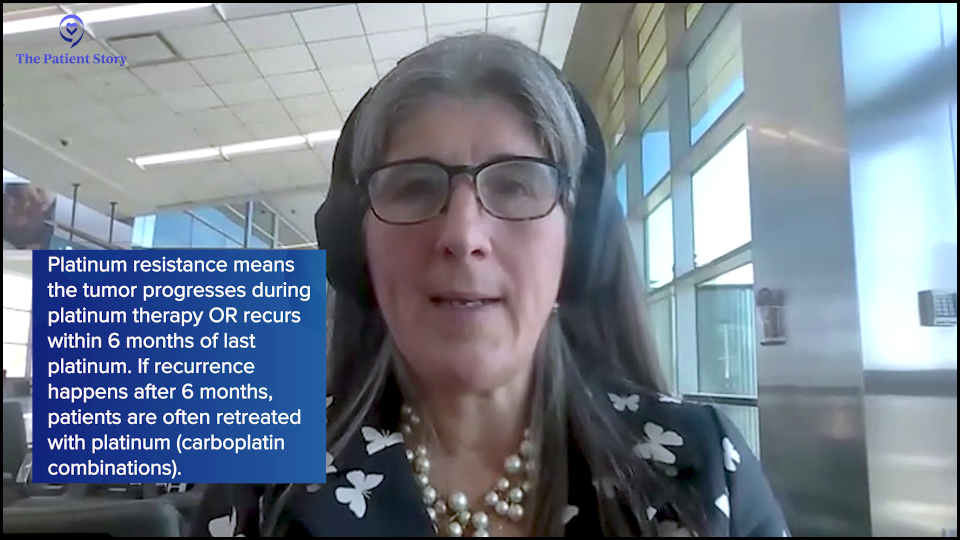

If we’re designing a clinical trial for a patient whose tumor is deemed resistant to platinum, what does that mean? It means that that tumor has progressed during its last exposure to platinum, which could be in the frontline, and that’s not common. But if a patient has recurrences that happened at least six months from the last platinum exposure, like carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata) — so the longer the better — we would typically treat again with a platinum-based therapy, carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata) plus gemcitabine (Gemzar, Infugem) or carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata) plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil). We might use paclitaxel (Taxol) and carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata) again. You may do that several times if someone gets it and then they recur again a year later. Patients are getting exposed to many lines of platinum.

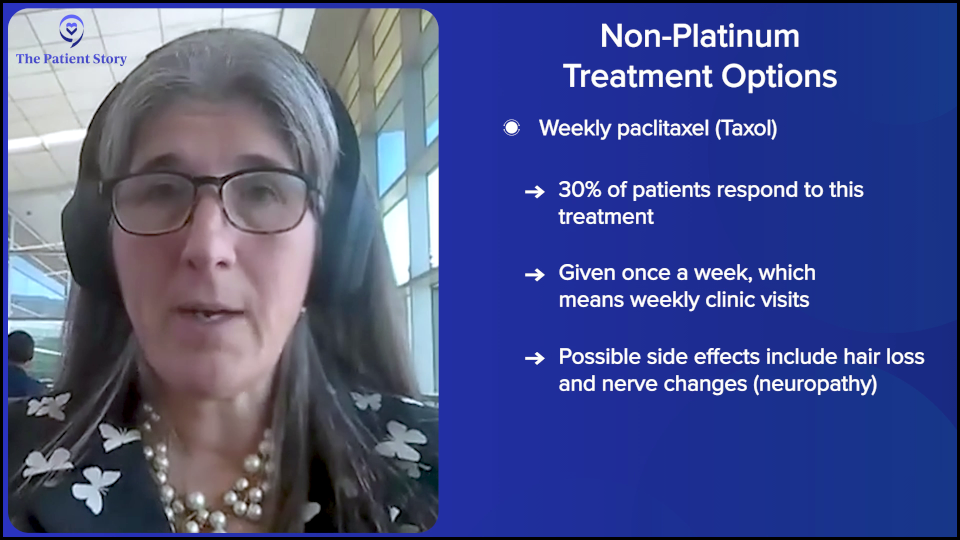

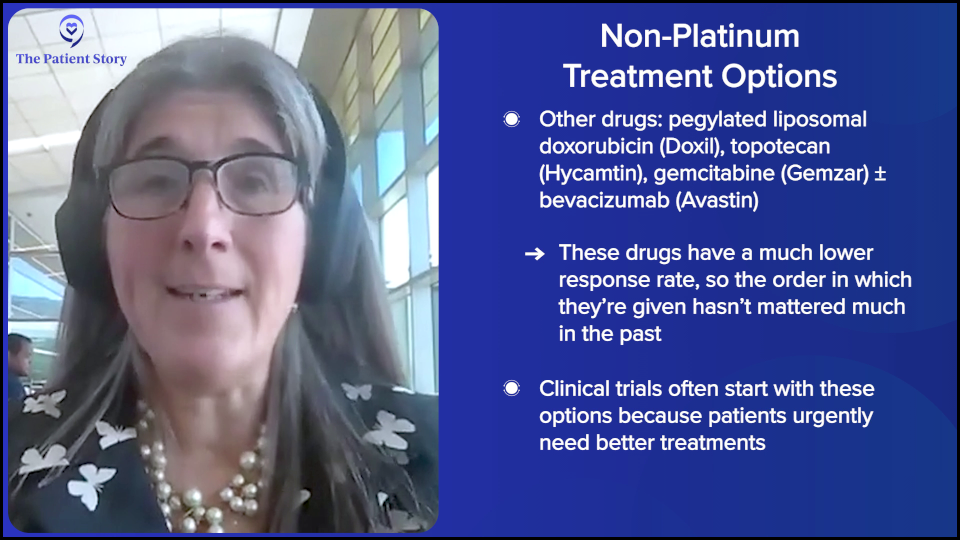

Once a tumor grows during the platinum treatment or anytime within six months of the last platinum, that’s the traditional definition of platinum resistance. The traditional thought is that we use non-platinum-based therapies in that setting, like weekly paclitaxel (Taxol), pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil), topotecan (Hycamtin), or gemcitabine (Gemzar, Infugem) with or without bevacizumab. That was the standard of care for a long time.

The truth is, other than weekly paclitaxel (Taxol), which is the most effective of the options that I listed, it’s also the most inconvenient. It’s every week, you lose your hair, and there’s neuropathy, so there are downsides, but it’s three times as effective. The expected response rate to paclitaxel (Taxol) in a resistant setting is 30% compared to less than 10% for others. The time spent on that drug without disease progression is about double. That is our most effective therapy — or was until this new round of medications.

Patients would typically get that and do pretty well for a while, and then once you move to these other things, they didn’t work very well. It’s this setting for a long time where we didn’t worry about sequencing because — I hate to be negative — but drugs that don’t work don’t work in whatever order you use them. This is where and why we focus on the platinum-resistance setting with novel drugs first.

Other than weekly paclitaxel (Taxol) — I mean, I don’t ever want to use pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) as a choice. I’m never going to use topotecan (Hycamtin) because it has a 0% response rate in every clinical trial. I’m not going to use it. I would be so sad if that were my option. But for most of our patients, because clinical trials are so limited in where they are, that’s what their very smart doctors have access to and it needs to end. That’s why we’re aggressive about developing in this space.

Now, the change is that the definition is decades old. What we understand now is in the frontline, if I use a PARP inhibitor appropriately in a patient with a homologous recombination-deficient or BRCA-mutated cancer, and she gets two years and then maybe recurs two years later, we expect that tumor to respond again to platinum.

If that tumor progresses during PARP, there’s an increasing worry that that tumor might not respond as well to PARP or platinum. Locking that patient and requiring her to have a platinum before I do something like an antibody-drug conjugate, that’s driving some of the newer trials. We’re trying to figure out and not just guess which tumor should get platinum again because they’re going to do well and which patients have tumors that are not going to benefit from platinum, even though they’re platinum-sensitive and should get access to the right drug earlier. That’s evolving. This concept of platinum resistance is going to change, but right now, it’s as I defined it, which is greater than at least six months, which is silly but that’s where we are.

Understanding Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

Stephanie: It sounds like there’s promise. Before we go into emerging treatments and clinical trials in detail, you’ve talked about antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs). Could you describe what those are in layman’s terms?

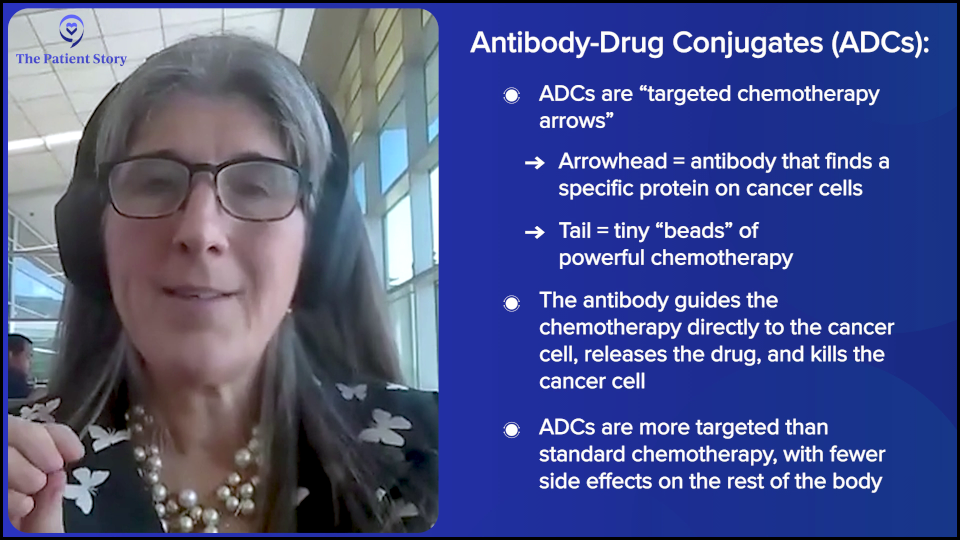

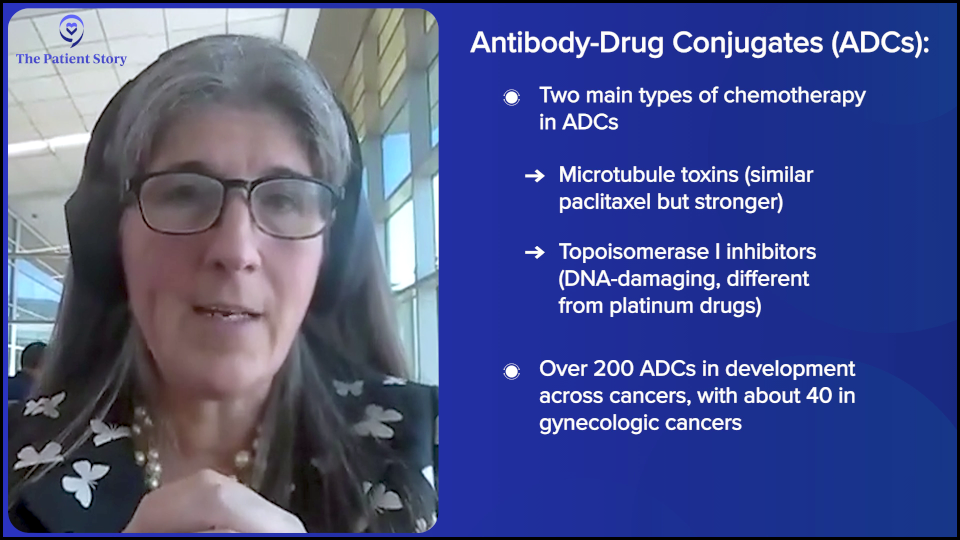

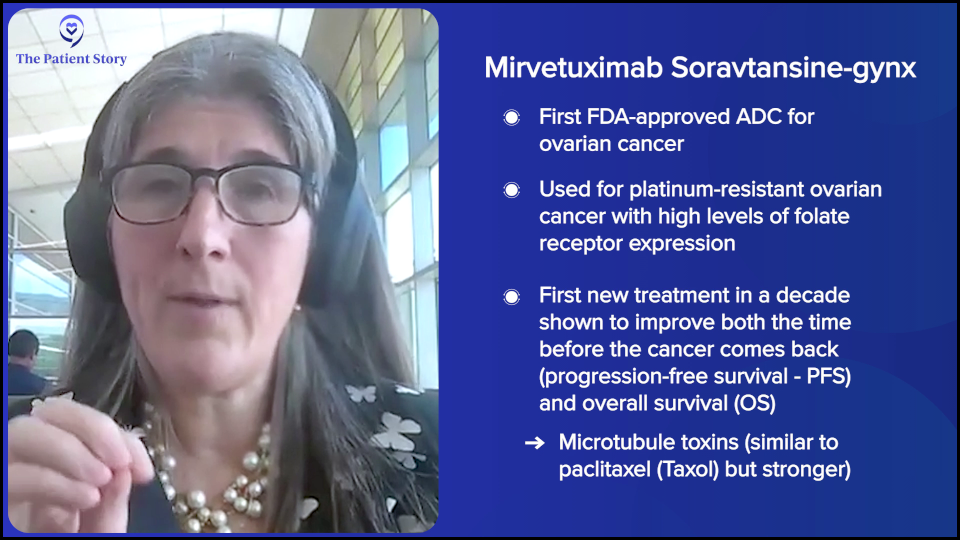

Dr. Moore: When you think about drug development in oncology, antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) are like a tidal wave. There are over 200 of these in development across all cancers and at least 40 in development in gynecologic cancers alone. There’s a lot of duplication, to be honest, but there are some unique elements.

I describe antibody-drug conjugates to my patients as an arrow. The head of the arrow is programmed to find a protein and that protein is picked because of a couple things. You want it to be either only on the cancer cell or so overexpressed on cancer cells as compared to normal that statistically, the arrow is going to find cancer. You also want it to bind to a protein that when the protein is bound, it gives the molecule a hug, brings it inside, and internalizes whatever binds to it. There’s some strategy in the proteins that are selected.

The head of the arrow is finding a protein. The feathers of the arrow are the linkers or the sticky and we stick little beads on to the feathers. Those beads are chemotherapy. This will change, but right now, this is fancy chemo or targeted chemo.

The beads of chemo are not carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata) or paclitaxel (Taxol). They’re totally different and highly potent molecules of chemotherapy. They come in a few flavors, but the two most common in development are microtubule toxins, which are most similar to paclitaxel (Taxol). They poison the mitotic spindle, so as the cells try to divide, they collapse. The second category is called topoisomerase I (TOP1) inhibitors. These are DNA-damaging agents, but totally dissimilar to carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata). They’re very unique agents. Even if patients have had carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata) or paclitaxel (Taxol), it doesn’t matter. These drugs can still work.

What happens is you give the drug and when it’s in the bloodstream, it’s not active because the chemo’s stuck to the tail feathers. When the arrow finds its target and gets internalized to the cancer cell, the acidic microenvironment of that hug that brings it in releases the chemo and the tail so it can kill the cancer cell. Then it can diffuse into surrounding cancer cells like a halo and kill the surrounding, even if they don’t have the target. That’s called bystander effect.

If they were perfect magic bullets — which they’re not yet — we would have no side effects because you would be sending these to the cancer cells, they will kill the cancer cells, and people would feel great. We have some absorption of the chemo into the systemic circulation, so you see various toxicities that we have to pay attention to, but they tend to be a very different toxicity profile from standard chemo. Usually, patients feel much better on them and so far, they’re looking much more superior to standard therapies.

When patients come to see me in my phase 1 clinical trials arena, I’m prioritizing antibody-drug conjugates. I want everyone to get an antibody-drug conjugate because they’re working. Now they’re moving into big phase 3 clinical trials.

We have one ADC approved, mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. For this drug to work well, it needs a lot of folate. You would test the tumor and if it has a lot of the protein folate, the patient is eligible for mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere). It’s the first new approval in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer in a decade and the first one to ever show improvement in not only progression-free survival (PFS) but also overall survival (OS).

Full disclosure: I was very involved in that. I led MIRASOL, so I have a conflict of interest when I talk about it. When you help bring something to market, you’re either consciously or unconsciously biased. I’m very proud of it and it’s going to serve our patients well for a long time.

It’s a modest improvement in PFS and OS, but it does set the stage for what we can do. Now we have next-generation medications coming that I anticipate will bring new options to patients whose tumors aren’t folate high and also to everybody. Additional options may even be better, so we’re pretty excited about that.

Stephanie: That’s amazing. Any progress is key.

Current Research on ADCs

Stephanie: You talked about the MIRASOL trial. When something works well, we know that, in general, the goal is to try and move it earlier or to other populations. Can you talk about any work that’s happening with mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere), following the MIRASOL trial specifically?

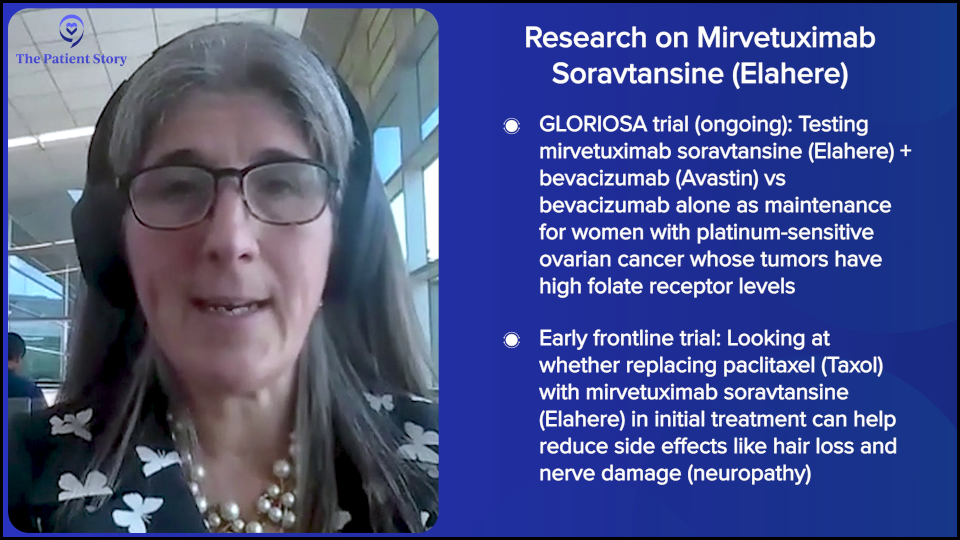

Dr. Moore: That’s absolutely what happens when it works in the resistant setting; you move it up. There’s an ongoing study where there’s quite a bit of accrual; it’s getting close to done. It’s called GLORIOSA and that moves mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) into the platinum-sensitive recurrent space, so for patients whose tumors recurred, were felt to be sensitive to platinum, got platinum, and did well. If their tumor is folate high, they’re randomized to get bevacizumab maintenance versus bevacizumab maintenance plus mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere).

GLORIOSA will be the first platinum-sensitive maintenance study with an antibody-drug conjugate to read out. It’s well underway, but it’s still open for accrual if patients are interested. It’s for first recurrent platinum-sensitive. Tumors have to be folate receptor alpha (FRα) high, so we’ll see the results of that.

There’s a small study led by one of my friends, Dr. Rebecca Arend, looking at frontline. It’s a small study, which is called an investigator-initiated study, replacing paclitaxel (Taxol) with mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) in the frontline. Right out of the gate, you lose your hair, maybe less neuropathy, and it doesn’t work as well, so we’re looking at that as a feasibility study as well.

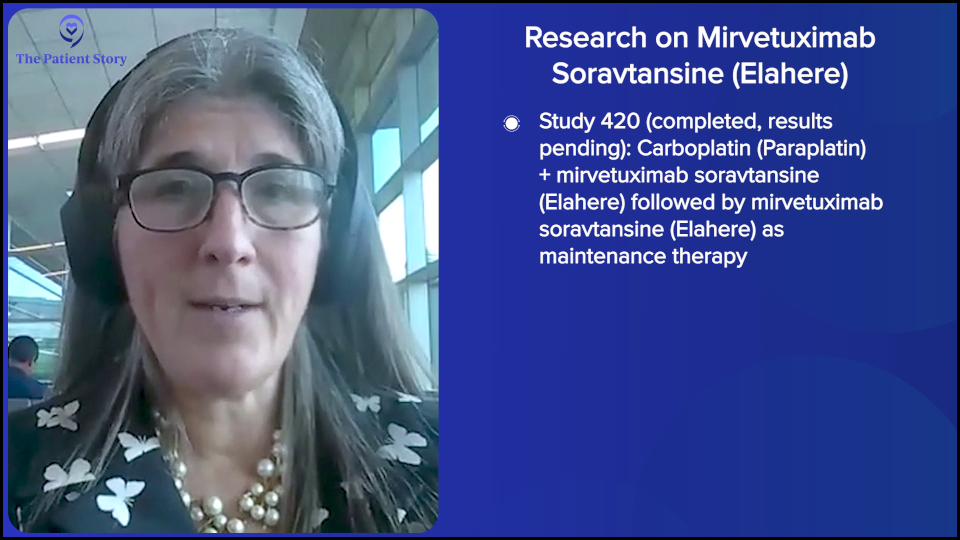

Then there are other plans for mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere), things that are finished in the platinum-sensitive space, carboplatin (Paraplatin, Kyxata) plus mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere), and then mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) maintenance that was called Study 420. That’s done and we’re waiting to see the results. Hopefully, we’ll see it at the European Society For Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, although that hasn’t been announced yet. Mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) is moving up.

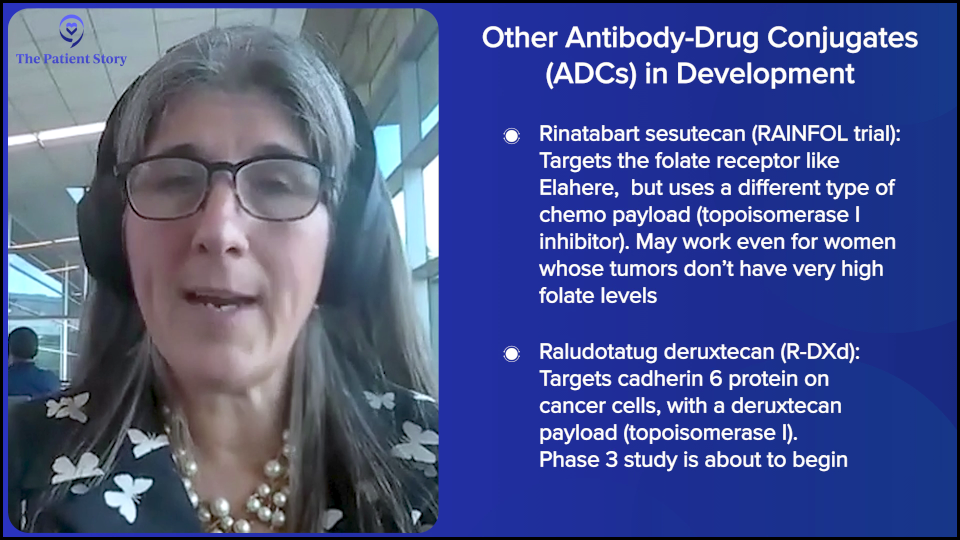

Then you have this pipeline of medications that are in phase 3 registration-enabling studies, such as staying on the folate bandwagon. Rinatabart sesutecan (Rina-S) is targeting folate, but instead of a microtubule toxin on its tail, which is what mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) is, it has a topoisomerase I. Same target but different chemo, so you could feasibly get both. That study is in a big phase 3 study right now called RAINFOL for patients with resistant tumors. They don’t have to be folate high. It’s like T-DXd or trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu) and breast cancer. As long as you have a little bit of the target, they seem to work pretty well. That drug is in all comers and that study is off and running.

Another drug in phase 3 is raludotatug deruxtecan (R-DXd). This targets cadherin-6 (CDH6). It’s a totally different protein and has deruxtecan chemo on its tail, so it’s another topoisomerase I inhibitor. We’ll see early results from that, I believe, at ESMO. We’ll see once the abstracts come out. We anticipate seeing the phase 2 dose finding results and then the phase 3 is about to launch in a similar space.

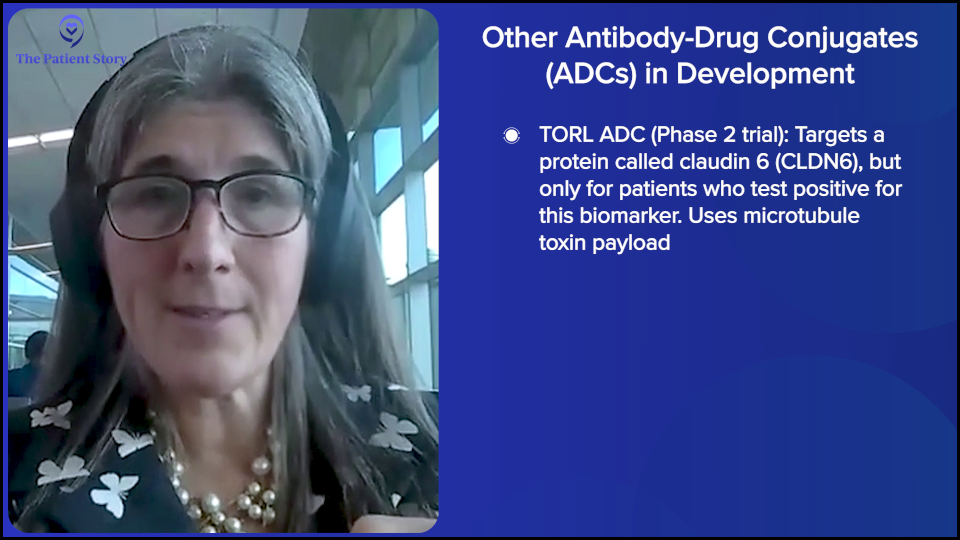

There are others that aren’t quite public domain yet. There are a number medications. Some are biomarker-linked, some are for all comers. They have similar payloads but not the same. There are microtubule toxins; mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) is the one that’s approved. Then there’s a drug made by TORL BioTherapeutics that targets claudin-6 (CLDN6). You have to test for CLDN6 and be high. It also has a microtubule payload. That’s in a phase 2 study. You have microtubule toxins and all of the topoisomerase Is because patients may get one of each because they’re totally different chemos.

Say these are all approved. The next big challenge is going to be determining which one a patient gets first. Does it matter? Do I do microtubule toxin first? Do I do a topoisomerase I? If some of these are biomarker-linked and some of them are all comers, what’s the best one for each patient? I’m probably only going to use one of each and I want to make sure I pick well. That’s going to be our next big challenge with all of these medicines. Individualizing treatment for our patient so they get the best drug for them that are best tolerated.

Stephanie: All the development that’s happening is incredible. You said two things: high folate for some and claudin-6 (CLDN6) test. When are you finding out folate? How high or low?

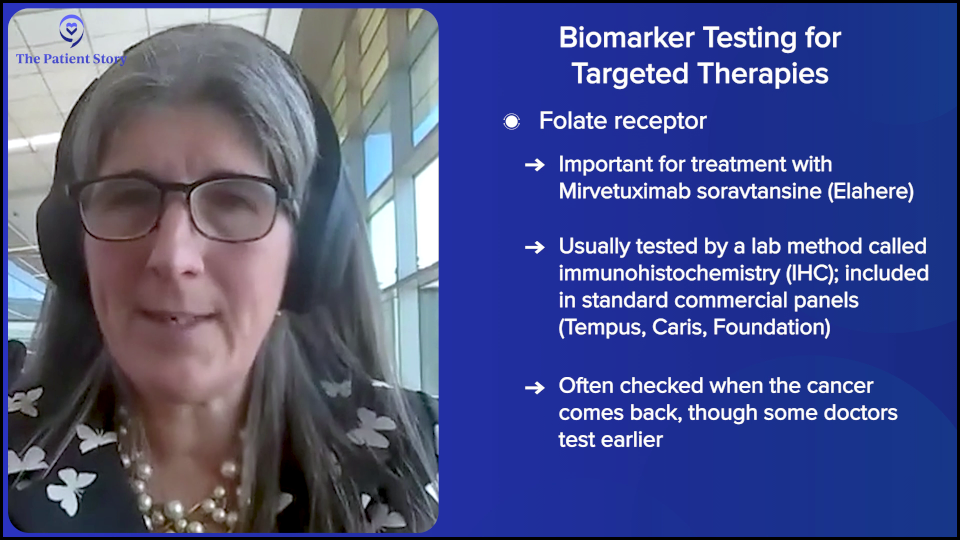

Dr. Moore: Right now, we rely on immunohistochemistry, which means a pathologist gets a slide, they have a stain for whatever protein, and they stain the slide. I don’t want to dismiss pathologists, but it’s a little subjective. There’s a little intraobserver variability, but that’s what we currently rely on. I think that will get better with time.

Because mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) is approved, folate is now a part of most of the panel tests that people send. If you send Tempus, Caris, or Foundation, you get the folate results and it varies when people do that. Right now, a lot of people don’t do it at the very beginning because they’re not using mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) upfront. We tend to send it upfront to know. Oftentimes, you’re not finding that out until the recurrent setting because that’s when you might use the medication. It’s part of the standard testing. Many bigger centers do it internally, but we have to send ours out.

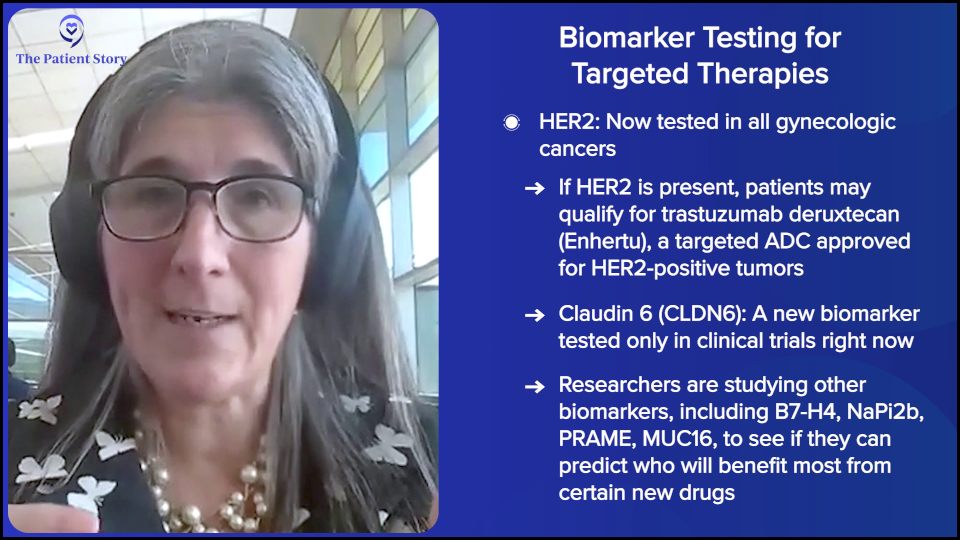

It’s the same with HER2. HER2 is a breast cancer immunohistochemical marker. It’s very common in breast cancer, but we’re testing all gynecologic cancers for it because there’s a recent FDA approval for trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu), an antibody-drug conjugate for HER2-high solid tumors, which is pretty uncommon in ovarian cancer. Only about 5% of our high-grade serous tumors are high, but if you found one, you want to use that medication. That test can be done locally, but you can have it sent out as well.

For all the other tests, like claudin-6, you have to sign a consent with a clinical trial — not necessarily to participate, but just so that your tumor can be tested to know if it’s high or low.

B7-H4 is another target in antibody-drug conjugates that companies are testing for. There’s a protein called NaPi2b, which is a sodium phosphate transporter. Some studies of that drug are doing everyone. Some studies are testing tumors for the amount of sodium phosphate transporter. That’s all done on a study-by-study basis as the companies are figuring out the cut points for the various proteins. Do they need a cut point? Does it work well on everybody or does it work amazingly and this high? Those are all done on clinical trials.

Folate and HER2 are standard of care. As the drugs get approved, the biomarkers roll into commercially available panels.

More Promising Ovarian Cancer Treatment

Stephanie: Are there any other later-phase clinical trials that you think show promise for the platinum-resistant population?

Dr. Moore: We’re all very excited about antibody-drug conjugates — myself included — how best to use them, what setting, and in what order. That’s the word cloud that we’re thinking about and hopefully, we cure some patients with ADCs, but we’re going to need other things to sequence in. Fortunately, there are a lot of other exciting things, so I’m going to name a few.

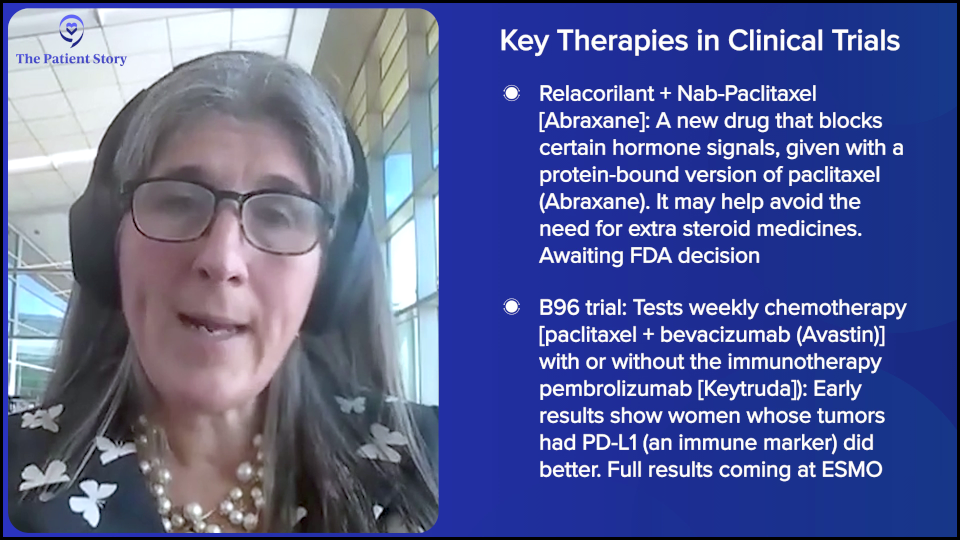

There’s a recent publication and presentation for a medication called relacorilant, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist given with nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane). The reason they chose to do that is because, as those who received paclitaxel (Taxol) know, they have to get steroids to not have a reaction. You don’t need that with nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane). If you’re using a glucocorticoid inhibitor, which is a blocking steroid, you don’t want to give more steroids, so they used nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane) with relacorilant versus nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane) alone. That study was positive for progression-free survival and the trend for overall survival looked good. We’re waiting for the final readout on the OS and for an FDA decision on that medication. That may soon be an available therapy for patients, so hold that thought.

At ESMO, we will hear a study called B96, which is weekly paclitaxel (Taxol) with bevacizumab with or without pembrolizumab (Keytruda). The press release says that the progression-free survival is positive and overall survival is positive in the biomarker PD-L1 positive, which is an immunotherapy biomarker. Apparently, we’re going to see this at ESMO.

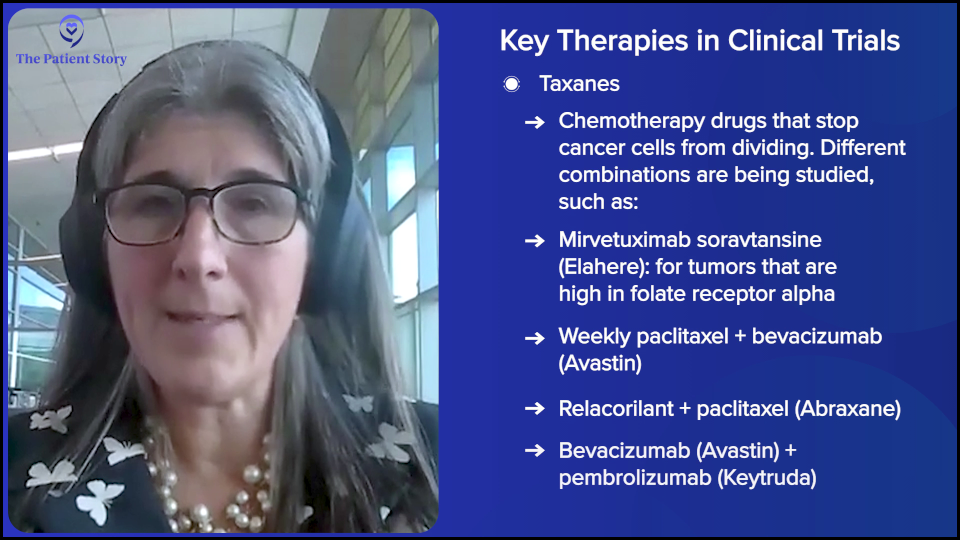

I told you already that weekly paclitaxel (Taxol) with bevacizumab for folate receptor alpha (FRα) not high is the standard of care. If you’re folate high, you should get mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) and then weekly paclitaxel (Taxol). But now, we have weekly paclitaxel (Taxol) + bevacizumab, relacorilant + paclitaxel (Taxol), and weekly paclitaxel (Taxol) + bevacizumab + pembrolizumab (Keytruda). You have three taxane options.

In a patient who has had bevacizumab already, has terribly high blood pressure, or has had clots, you’re going to have some potential new options. That’s exciting and, timewise, very proximal to us having maybe some new things. Those are things to watch for.

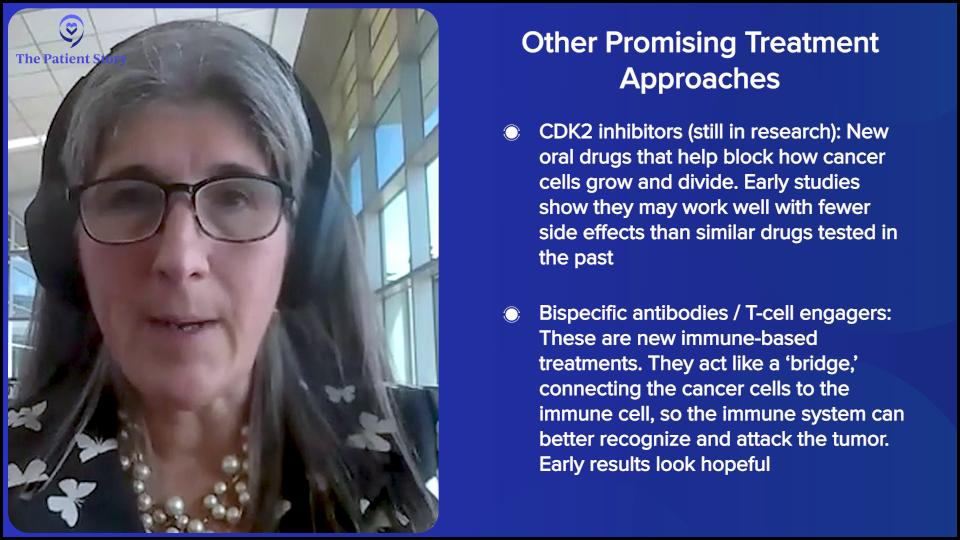

There are two others entering studies. I think we finally may have cracked the nut on cell cycle inhibitors. Many of us spent many years working on WEE1 kinase inhibitors, ATR inhibitors, etc., and they work in a select population of tumors that are Cyclin E amplified and that’s something else you find out from these panel tests. But they’re a little too toxic to get over the hump.

CDK2 inhibitors may have cracked that nut. We’ve seen data at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting in a platinum-resistant setting that looked like a very nice response rate with a very clean toxicity profile. I have one in clinical trials and I believe people don’t feel terrible, so I’m pretty excited about that. I’m more excited about that being a maintenance treatment in the future. It’s exciting to have something that works pretty well, stabilizes tumors, and doesn’t make people feel terrible like a lot of oral drugs, so I would watch for the CDK2s.

The less developed but exciting ones are bispecific antibodies. Some of them are T-cell engagers (TCEs), some are pure bispecific. Bevacizumab is an antibody. It targets vascular endothelial growth factors. It sucks it up, blocking how tumors make blood vessels for themselves. If you picture an antibody like a Y, like a T-cell engager, you find a protein that’s on the tumor. PRAME and claudin-6 are good examples. The other part of the Y arm grabs a T cell and tries to get that immune cell to recognize that the protein is bad and to start cranking out an army of immune cells that target the protein. You make your body create the immune response that you wish it would have done before. Those are looking interesting, so I would keep an eye out on those bispecifics or T-cell engagers. Then there are bispecifics that are based on the antibodies that hit two proteins that are looking good.

Immunotherapy in ovarian cancer has been a little disappointing to date, but we haven’t given up and the bispecifics may change that. We have antibody-drug conjugates, at least two. We have taxane-based therapies: relacorilant, bevacizumab, and pembrolizumab (Keytruda). We have cell cycle therapies with CDK2s coming. We have bispecifics. And there’s even more. Four categories with multiple things within them means good opportunities for patients to do better.

Talking to Patients About Clinical Trials

Stephanie: How do you try and explain clinical trials to people? By itself, it’s not a great term. How would you advise patients to think about clinical trials and when to ask about them?

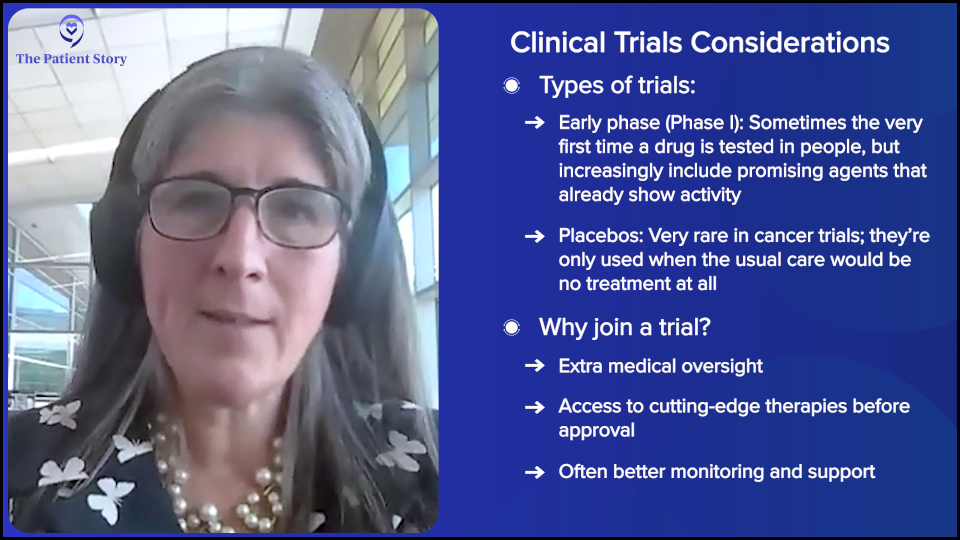

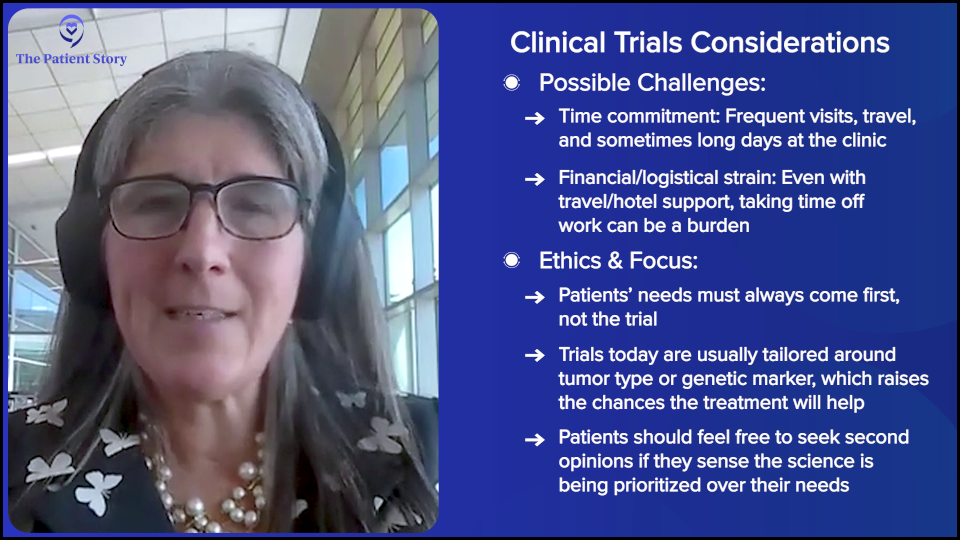

Dr. Moore: People have heard of clinical trials. People don’t want to feel like a guinea pig and they also don’t want to feel like they’re part of a science experiment. They want to participate. I’m not always right, but I want to run clinical trials that I think are going to work, for one reason or another, and that I’m excited about. That’s why I do trials and that’s what I try to communicate to patients.

Sometimes, I’m in phase 1 trials and I have something that’s brand new and hasn’t been tested in people, so I can’t tell you what the expectation is or if it will help you, and I’m very open about that. If patients have seen everything and they still want to try something, that’s part of the consent process. I get patients who have the first or second recurrence, participating in phase 1 trials because we have access to antibody-drug conjugates, CDK2 inhibitors, and WEE1 kinase inhibitors that already have some proof of efficacy and they want access to those medications.

There’s no placebo, so in the early phase, that can be very reassuring. The use of a placebo is uncommon now in clinical trials. The only place where we’d use that is if the standard of care is no therapy. People are getting active therapy. We’re not going to give someone with recurrent cancer no therapy.

The advantage to clinical trials that I try to explain to patients is that there’s a bigger team watching. Even if you’re randomized, if you’re doing a phase 3 study where you’re randomized to the standard arm, which people are always disappointed in because they want the fancy new drug… We try to get to them on the next line of therapy with crossover, but even on the standard arm, more people are watching the orders and the toxicities because we have research nurses. There’s easier access if you’re having a side effect because we have research coordinators.

They ultimately can get better care on a trial than with the standard of care where you’re seen every few weeks. In a trial, we talk to you every single week to make sure you’re fine. I try to reassure people about that. The placebo question is a real one. Am I a science experiment or a guinea pig to you? It’s a real concern. We have to be careful as clinical trials have definitely been this way in my younger years where you get caught up in the science and don’t focus on the person in front of you and what’s good for them. We always have to center ourselves. Patients are the North Star, so if you get a sense your doctor’s not doing that, you can ask for a second opinion.

For the most part, clinical trials are developed out of the gate for either a mutation or a tumor type, so they’re meant to work. It’s just a different era. Patients get access to these medications. I would want that for my mom and any one of my patients, but I do understand the trepidation around it.

There’s time toxicity to being on a trial and sometimes financial toxicity because you have extra visits and take time off work. We’re calling and asking you how you’re doing all the time. There are all these things that are unmeasurable sometimes that lead to burden, so we have to be careful to communicate that to patients when they’re considering a clinical trial. We do everything we can to offset it with travel vouchers and hotel vouchers, but the time toxicity is real. For somebody with precious time and coming from a different state, that’s a big ask. You have to be clear upfront about what the study requires. Make sure people have all the opportunities to be informed, to ask questions, and not feel coerced. Keep it people-centered. Patients first, trial second.

Stephanie: I appreciate that. It comes back to what you said in the beginning, which is you’re listening and allowing the patient to make decisions for themselves. Let’s make sure they have the information and they can choose based off the conversation.

How to Get Access to Clinical Trials

Stephanie: In the very beginning, we talked about how a lot of people get their care in the community setting. You talked about how people don’t feel they can travel long distances if it’s going to be at some other center far away. What is your overall guidance to patients and families who live in that situation?

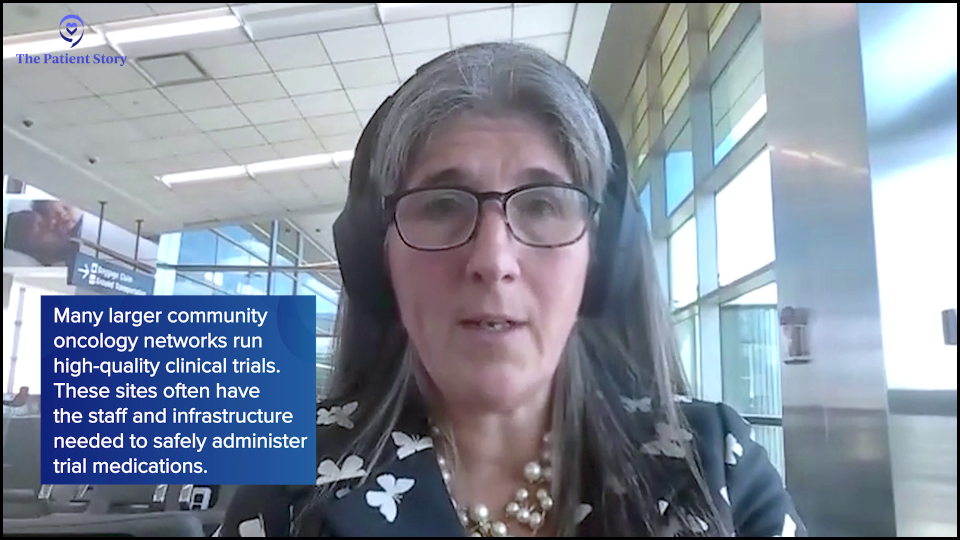

Dr. Moore: There’s a lot of clinical research done in the community. There are a lot of community sites doing very high-quality clinical research. Trying to figure out where that is in your community can be the first step. We have them in the university centers, but a lot of research goes on in the community. I wouldn’t say this as an overarching statement, but it tends to be at some of the bigger clinics, like Kaiser, Texas Oncology, or Sarah Cannon. Those clinic networks are community-based, but they have a network of support so that they have the infrastructure needed to open a clinical trial.

It’s not that community oncologists don’t want to have trials open for their patients; they very much do and they’re very much smart enough to do it. That’s not the problem. The problem is that it couldn’t be done alone. You need research nurses. You need regulatory staff to make sure you have the right consent version. You need data managers to enter the data. You need a pharmacist who understands how to mix study medications, which is very different from how we mix medications for standard of care.

All of those things are the back of the house for running clinical research with oncology medications. They’re expensive for an institution to maintain. In the community, some of these bigger practices have been able to do that and centralize it so that their community sites have access to trials. But with some of the smaller sites, it’s hard for them to stand out. I wanted to make that point because it’d be hard to find an oncologist who hates research and doesn’t want trials. They all do. It’s just hard to put that up.

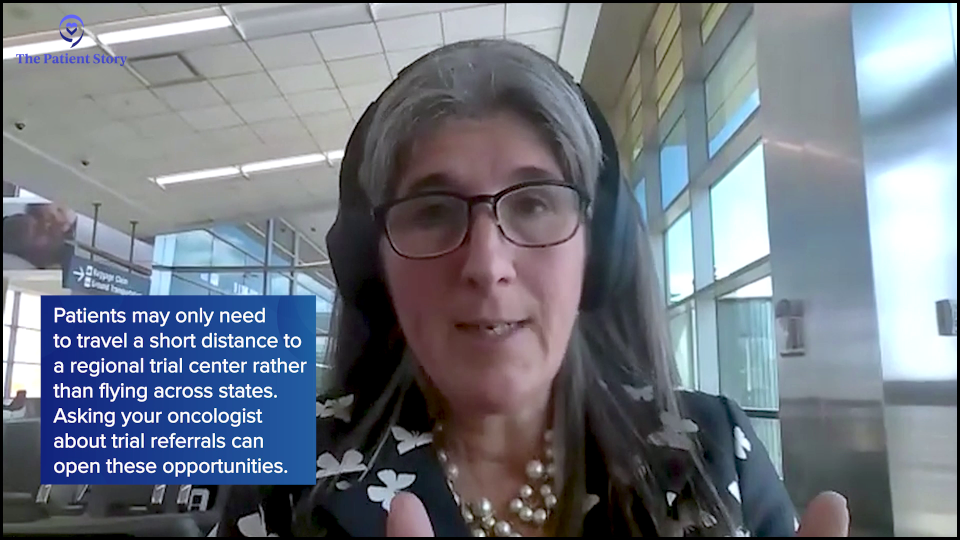

But you can find research in a community setting in a lot of places if you know where to look. Asking about referrals to clinical trial centers sometimes may be as easy as an hour or two down the road, as opposed to having to get on a plane and flying in from another state. Sometimes patients don’t know that.

It has gotten hard post-COVID. During the COVID pandemic, I was able to do interstate consults. People will call me or I will get an email saying, “Can I have a second opinion? Can I talk to you about clinical trials?” And I could do that. Now, all of those have been retracted because I don’t have a medical license in other states. When I get patients who want to talk to me, I can’t do it without getting in trouble, which feels terrible. But if I don’t have a state license in your state, I can’t give you medical advice.

We’ve tried to work around that in different ways because we don’t want people to fly all the way in if they’re not eligible for a trial. But I always tell people to advocate for themselves. They try to reach out to me or one of my colleagues, and we say we can’t talk to them legally. It’s a barrier that’s very frustrating. Because you live in Texas, I can’t talk to you about clinical research without the risk of practicing out-of-state medicine since I’m in Oklahoma. But that’s the world we live in. We have tried to get creative, but we also don’t want to lose our licenses. That’s just the truth.

On the East Coast, a lot of my colleagues have licenses or have agreements in surrounding states. We’re working on that right now. Some states have certificates we can get so that I can do a consult in the setting of cancer or other kinds of extreme circumstances. We’re trying to work on that, but I don’t think patients understand the limitation we have, which is frustrating and so annoying. But that’s the reality of trying to help people in other states. Sometimes we can’t let you present yourself to a center, so finding the closest center possible makes the most sense.

Conclusion

Stephanie: Dr. Moore, not only are you brilliant and so experienced, but you clearly care about patients so much. Thank you so much for joining us for this program and for all your work you do.

Dr. Moore: Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

Stephanie: That was wonderful. I learned a lot and I hope you did as well. I hope this discussion has helped you consider all your treatment options, but more importantly, understand what questions you can ask to make better decisions for yourself or your loved one. While we hope this conversation was helpful in that way, remember that this is not a substitute for medical advice. It’s informational, so please consult your own healthcare team.

There are amazing patient groups out there that provide support in many different ways for patients and care partners. To name a few, there’s the National Ovarian Cancer Coalition, the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance, the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition, and many more. I encourage you to find the support that will help you.

We want to thank our sponsor again, AbbVie, for helping bring this program to you. Their support allows us to do more of these programs. I do want to note that The Patient Story maintains full editorial control.

Finally, we want to know how you feel. Your voice matters because it helps us to shape the next program or story that we present and publish. In what ways was this helpful? What would you like to hear more about? What went well? What could we do better?

Thanks again for joining us. Hope to see you again. Take care.

Thank you again to AbbVie for supporting our independent patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.