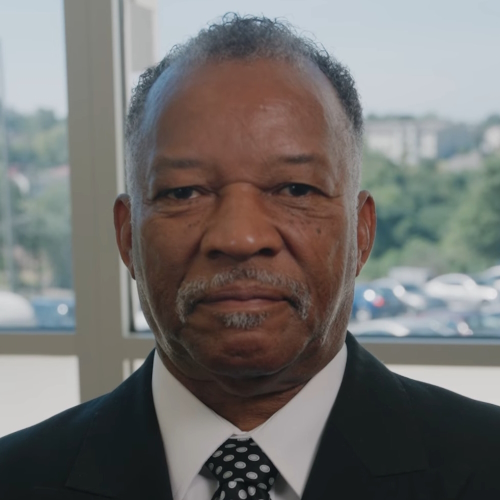

Mical’s Stage 2 Prostate Cancer Story

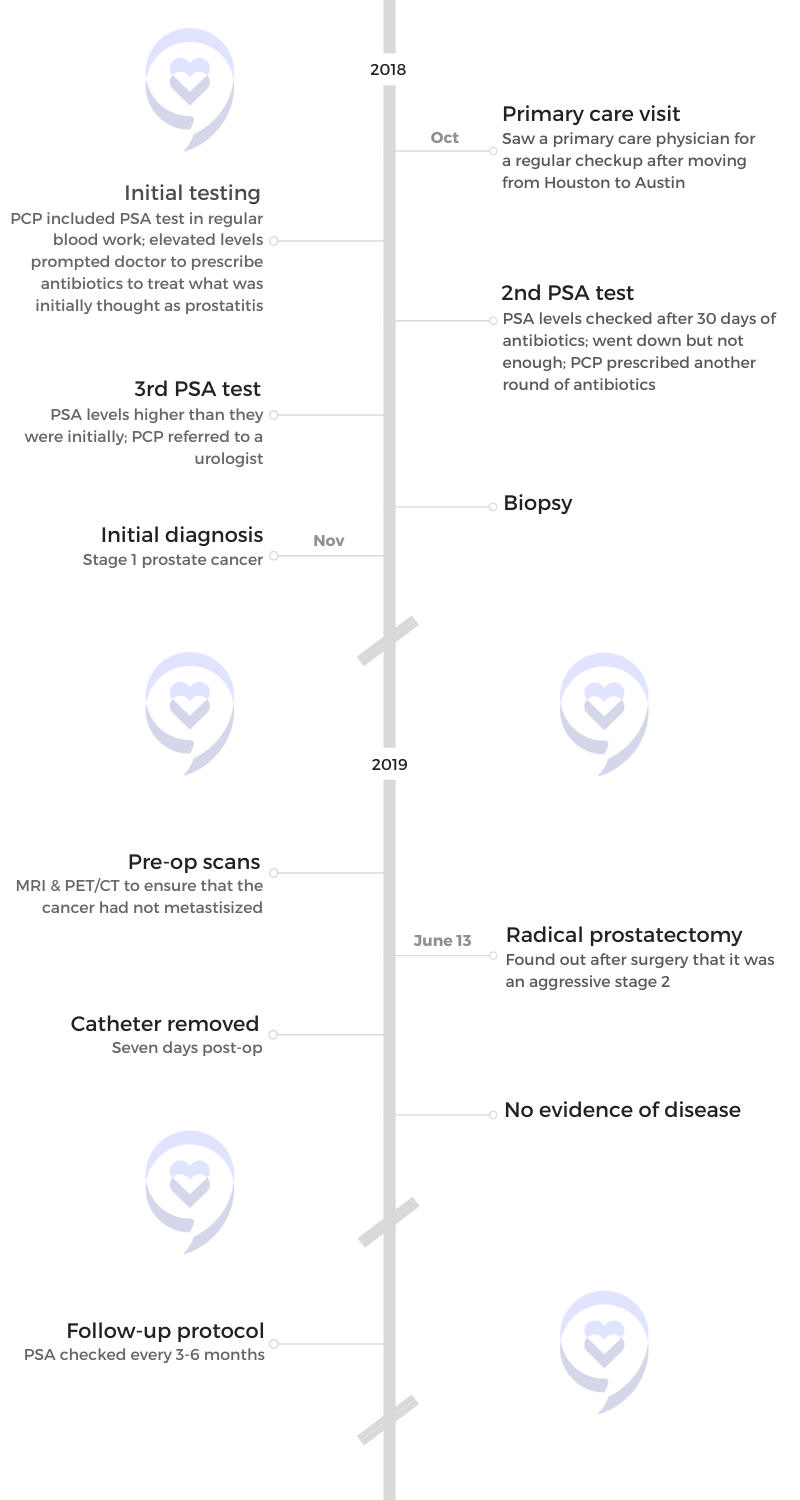

Mical was initially diagnosed with stage 1 prostate cancer at 37. They learned after prostatectomy it was an aggressive stage 2.

He had no symptoms, and he wouldn’t have found out at an early stage if not for a guardian angel of a doctor who decided to include the PSA test in his regular blood work.

Now, Mical uses his voice and his story to advocate for prostate cancer awareness, especially in the Black community, conversations about family health history, and the importance of early screening.

- Name: Mical R.

- Diagnosis:

- Prostate Cancer

- Staging: 2

- Symptom:

- No symptoms, caught at routine physical with PSA test

- Treatment:

- Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Since being diagnosed with prostate cancer, my focus has shifted, and I’ve become super passionate about spreading awareness and advocating for more awareness, certainly in the Black community.

As a Black man, I feel that if I had certain things on the awareness side, then my journey could have looked a little bit different.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Pre-diagnosis

Tell us about yourself

I have a twin brother. I’m a family man. I have two daughters. I’ve been with my wife for 18 years. We’ve been married 16 years.

I was a teacher for many years. I still work in higher education as an instructor. I’m passionate about reading and writing. That’s all I’ve ever taught, English language arts. Love writing.

Since being diagnosed with prostate cancer, my focus has shifted and I’ve become super passionate about spreading awareness and advocating for more awareness, certainly in the black community. As a black man, I feel that if I had certain things on the awareness side, then my journey could have looked a little bit different.

I’m doing my part so that men don’t have to go along not knowing the disparities and not knowing that black men are two times more likely to be diagnosed and 2.5 times more likely to die from the disease. It’s become my life’s work to do this.

I would have thought that if I had cancer that I would have been able to sense it.

Initial doctor’s appointment

[I’ve lived] in Houston my whole life aside from college. My whole family moved to Austin [when] I got a job promotion. That was 2017.

In 2018, we finally got settled. We [needed] to find a doctor because prior to moving, I went to the doctor every year. I was accustomed to going to my annual wellness visit at a minimum. My wife is from Austin. My in-laws recommended this primary care physician because they’ve been her patients for 15 to 20 years, so she came highly recommended.

My wife and I couldn’t get in. We kept calling to try to get an appointment. They were booked up. My mother-in-law said, “I’m going to text her and say, ‘Hey, I’m trying to get my son-in-law and my daughter.’” The doctor responded, “You tell the front desk that I said make it work.” That’s how I arrived at this doctor. This is key for me.

[On] my very first visit, she [needed] to know [my] family history. At that time, the only family history I knew was that my aunt, my mom’s only sister, had been diagnosed with breast cancer just weeks before. My paternal grandmother had recently died of stage four lung cancer — breast cancer that metastasized to her lungs.

This was a regular checkup. She did the blood work. But unbeknownst to me, she also tested my PSA levels. When the blood work came back, everything was great but she noted, “I’m concerned about your PSA levels.”

That was the first time I ever heard the word. I actually had to Google. What is that? I was just going for my annual physical, to establish this relationship. I had no symptoms at all, not one. I was very healthy [and] young.

I Googled it and I never got alarmed because I didn’t have symptoms. I always felt like whatever the concern is, it’ll be ruled out because I feel great. I would have thought that if I had cancer that I would have been able to sense it.

She told me, “I want to put you on an antibiotic for a month,” because she initially thought it was prostatitis, which is a prostate infection. I did the antibiotics for 30 days. She retested my PSA. She said, “I’m not satisfied. It came down a little but not enough. I want to put you on an antibiotic for another 30 days.” I did the 30-day round again. After that 30 days, when she tested my PSA, the levels had gone up higher than they were initially.

I cannot remember what the number was. It wasn’t crazily high but it was higher than it should have been. It was cause for alarm. In a period of two months, from whatever it was initially, it went up. It didn’t go down so that’s alarming.

At that point, she said, “I think we should send you to a urologist so that they can have a further look.” I did everything she told me to do. I went to the urologist that she referred me to.

They did a biopsy. A week later, I found out. At that time, they told me it was stage one prostate cancer. But we ended up finding out after the surgery that it was an aggressive stage two.

I always tell people that I used to think that I moved to Austin for a promotion, but I really think I moved to Austin to save my life.

What makes that doctor so good?

What makes her so great for me [is] that she comes highly recommended and they love her so that helps me feel more comfortable. [The] first time that I ever met her, I felt like [I’d] known this lady forever.

She’s intentional about being present, really listening and engaging, talking to me about other things, just getting to know me, and not making me feel like I’m one more [patient]. We know doctors are busy but I’ve been to so many doctors where I feel like [there’s] no time to connect so that’s what’s made her so special for me.

I call her my guardian angel. Essentially, she’s the person that diagnosed. She’s the reason that we’re here because I can almost bet that if I hadn’t met this doctor, there was no reason for me to get this PSA test if I wasn’t of age. I had no symptoms. It’s nothing but God.

If I didn’t meet this doctor, I can guess how things would have turned out.

I always tell people that I used to think that I moved to Austin for a promotion, but I really think I moved to Austin to save my life.

The night I found out my diagnosis, I called her and I said, “Hey, I just wanted to update you. It’s cancer.” She said, “Let’s pray,” and we prayed right then. She’s not a black doctor. She’s a white woman. Some people might assume maybe there was a cultural… no, she’s a white woman.

I call her mom, honestly. She 100% gives me that energy. I asked her, “What made you take my PSA levels? What made you do that?” She said, “I’ve just been noticing in the five years prior that younger and younger men are being diagnosed.” She’s probably just been reading literature. She’s up on the latest news and that’s what made her do it. And I’m grateful for it.

What did you know about prostate cancer?

I never thought anything. I’m sure I saw a commercial or something but a personal connection, never. I don’t know that I even knew anyone who had prostate cancer, besides maybe someone on TV.

It couldn’t hurt if you did the test and [if] it’s fine, then it’s fine.

Importance of knowing your family’s medical history

She said that because she noticed that younger and younger men [of color] were being diagnosed that it couldn’t hurt, which is true. It couldn’t hurt if you did the test and [if] it’s fine, then it’s fine. I also assumed that telling her about breast cancer on my mom’s side and my dad’s side may have just helped to make that decision.

This just goes into — and I can only speak for the black culture — we don’t discuss family history. We really don’t discuss things at all, but we certainly don’t discuss family history.

After I had surgery, I was back at work [and] I was on the phone with my dad’s only living brother. [I] found out that [he] had prostate cancer five years before me. My parents actually knew that he had it and they knew I had it. But even at the point [when] they found out I had it, they still didn’t tell me.

Men just don’t like to talk about this stuff, period. Men are not crazy about going to the doctor. Even if a man knows something’s going on, some men won’t go.

That also goes into why I choose to be such a big mouth about it because we’re just not doing ourselves any favor. This is not helping to move the needle forward by us keeping it to ourselves. We have to stop being such a taboo thing.

Men just don’t like to talk about this stuff, period. I’m just speaking for men. Men are not crazy about going to the doctor and this is a disease that affects men. I think specifically for prostate cancer that would be one of the leading reasons why most men feel like it makes them less of a man or they just don’t feel comfortable sharing it.

I’ve met so many men who I know have prostate cancer because I had it. But if I didn’t have it, they probably would have never told me that. I try to speak out for all of them because, at the end of the day, nothing is more authentic than an actual patient experience.

Doctors can get on here and they can say all of the amazing words. No one told me about this [and] I was going to the doctor. That’s a separate issue for some men because some men refuse. Even if a man knows something’s going on, some men won’t go to the doctor. But I was going to the doctor. And so for me, if I was aware of that health history, then I could have been advocating for it well before when this doctor just chose to do it.

If I didn’t meet this doctor, I can guess how things would have turned out. I would have still been going to the doctor but no one would have [chosen] to check it so it would have looked dormant until stage three or four. I’m so grateful for the way it happened and I have to do the work and be boots-on-the-ground grassroots because my life is essentially spared.

Getting a biopsy

Before this, the only surgery I’ve ever had was when I was in college to have a lymph node removed from [the] left side of my chest. When they said I needed to have a biopsy, I really didn’t understand what that was until I was there and it was happening.

They biopsy portions of my prostate. I can’t remember how many pieces they took, maybe four or five. Then based on that, they were able to see that cancer was present. At that time, it was stage one. But we later realized once they dissected my prostate after surgery that it was an aggressive stage two.

In black men, it can lie dormant and it can also be aggressive, which was exactly what happened to me.

Diagnosis

Getting the official diagnosis

It was seven days from the time I had the biopsy. The thing is, I don’t know if it was God keeping me sane, but I genuinely went through all of that — from the time that I met that first primary care physician all the way up to the results — whole time in between, I never ever got rattled. I never wondered, “Could it be?”

I consistently felt great. I felt good. I feel like I’m pretty in tune with my body. If there was something going on, I would have had a symptom, right? But it wasn’t until after learning more about this disease that it presents itself in different ways.

In black men, it can lie dormant and it can also be aggressive, which was exactly what happened to me. I had no symptoms but my cancer was an aggressive form, which is something that’s just wow.

I needed to go back to the doctor to get my results. Prior to that day, I had already gone to this urologist twice. The first visit was the consultation to talk to me about everything and then the second visit was the actual biopsy. Both times, I pay the co-pay.

On the third visit, I know that I’m simply going to pick up results. That morning at work, I was just talking to my colleagues. “I don’t think I should have to pay another co-pay because I’m really I’m not getting a service rendered. I’m just picking up results for a service.” They’re like, “No, I don’t think you should.” I’m like, “Yeah, I don’t think so either. I just want to call the doctor’s office just to make sure.”

I call the doctor’s office and the lady who I spoke with, I had a sense that she was a black woman. She reminded me of an aunt. I explained to her, “I’m just getting results today.” I don’t think I have cancer so this is also leading the way I’m dealing with it. “I just need to pick up my results today and I’m just trying to make sure if I have a co-pay.” She’s like, “No, you shouldn’t. You know what? This is what I’ll do. I’ll send an interoffice request for your results and then they’ll send them down to me. So call me back in an hour because I’ll have them by then.”

In an hour, to the minute, I called and she probably was so busy between the first time I talked to her and now that she hadn’t even checked her emails. She’s like, “Let me look. They haven’t sent it yet. That’s weird. I don’t know why they haven’t sent it. Listen, I’m going to go up there and get it and I’m going to call you back.”

She calls back and says, “Hey, I was just thinking you should probably just come in.” As soon as she said that, that’s when I got scared because I felt, even though I hadn’t talked to her that many times, we had just built this rapport where she agreed that she’s going to give me the results and now she’s calling me back and telling me to just come in. The inflection in her voice, the energy, all of it, just made me say, “Okay.” I didn’t ask her why. I didn’t say, “What made you change your tone?” I just said okay and I got scared then.

I came home that evening and I told my wife. We were actually driving to the urologist for that appointment. “Babe, I called earlier. I talked to a lady.” I said I was trying to make sure we shouldn’t have to pay another co-pay. She’s like, “Well, no, we shouldn’t.” I said, “Yeah. The lady was supposed to just be getting me my results. But then she just told me I should just come in. I don’t know why. That just felt weird to me.” That’s what I told my wife and that was the first time I got scared.

She calls back and says, “Hey, I was just thinking you should probably just come in.” As soon as she said that, that’s when I got scared.

Before that, I was just moving through whatever I was being told to do because, in my mind, we’re going to rule it out. All of this is going to rule it out. We get to the urologist’s office. When I walked back up [to the front desk], as I was approaching the counter, the lady says, “Okay, your co-pay for today is…” I don’t remember what the amount was. My wife [went] right up to the counter and she’s like, “I don’t understand why we have to pay a co-pay. We’re just getting results, that’s all we’re doing. Maybe we have to see the urologist but it’s not really a visit. We’re just getting results. The service was rendered.” The lady goes, “Let me go check.”

The lady comes back to the desk with a piece of paper and slides [it] under the little window. I looked at the sheet. It was graphs and charts. I don’t know what it was. She said, “Oh, that’s your results.” At that time, I’m certainly thinking now she’s sliding me my results that it’s got to be negative.

My wife demanded that the urologist at least come and hand us the sheet of paper himself. The lady at the front desk walked away, came back, and she said, “Okay, the urologist said he’ll see you in a moment.”

We sit in the lobby for about 15 to 20 minutes. A nurse came and got us, took us to a waiting room, and we waited there for about 10 more minutes. Then he walked in. It was me, my wife, and my daughters were with us too. We were all together so we were all in the room. My daughters were younger. They were playing at our feet. They were in their own little world.

He came in, he’s talking, and I don’t know if it was so traumatic that my mind just deleted it because I completely never heard him say it. One reason I knew he must have said something bad was because my wife was crying.

I looked at her. “What did I miss? Can you repeat what you just said?” He said, “Yes, you have stage one prostate cancer.” My immediate reaction to him was, “Wow. You knew that I had prostate cancer and you were going to let me take that sheet of paper home and figure that out on my own?”

I knew right then that on this journey, that wouldn’t be my urologist. He was very embarrassed. He was trying to explain it away. “I see so many patients every day and right before I came in here with you, I was seeing another patient and he was crying on the floor.” It’s terrible.

It’s amazing to this day, it just is… wow. I didn’t pay that co-pay.

‘Wow. You knew that I had prostate cancer and you were going to let me take that sheet of paper home and figure that out on my own?’

Looking for a new doctor

I came home that night [and] called my primary care because she’s the one that referred me to him. I said, “Hey, this is not going to work. I have cancer.” She referred me to a new urologist.

I think I’m [savvier] in that space because I’ve been going to the doctor so I immediately know I’m not going to be able to work with this urologist. I’m also going to make sure I file a complaint with the Board of Urology. Certainly people in my community, they’re not going to know those types of things. Some people in my community would actually still stay with that doctor just because they feel like I don’t have any choice.

I left that urologist. He’s in the rearview mirror. Met with the new urologist. My wife came with me. He was in a little rolling chair. He rolled it right up in my face and he’s talking to me, looking at me right in the eye. He’s just talking to me. The energy was just so tense. He needed to leave the room to get some paperwork and as soon as he walked out, my wife and I looked at each other. “That’s him.”

Treatment

Radical prostatectomy

I was diagnosed in November and I had surgery in June. When I was initially diagnosed, I was told it was stage one by that first urologist. Then after surgery, I was told that it was stage two so it could be one of two things. It could be that I was misdiagnosed at first or it could be that it just progressed during that time. What I’ve learned about the disease since then [is that] it’s plausible that it could have actually just progressed during that six-month period.

My team of urologists had actually advised me [that] because [of] my health and all these different factors, they wanted me to do it within a year from diagnosis. I chose to do it in six months. I probably could have done it sooner but that was during the summer, I was off from work, and that was the reason I chose to do June.

I could have done it later. I’m glad I did it but my urologist told me, “You’ll be fine. We don’t suspect that it’ll escape the prostate in this time and metastasize.” That’s why it wasn’t a real urgency to do it December or January because I was told that as long as I do it within a year, I’m good.

Deciding when to do the surgery

I’ve heard of many men who also found out they had it and they just waited even longer. They just didn’t want to confront it.

Do I want to lose my prostate? No. But I know that I have this disease and I want to get it out as soon as possible. I could have done it sooner. I just chose to wait until June specifically because I know I was going to be off. I wouldn’t have to use vacation time.

If I worked all year and didn’t have that as an option, I would have gotten it done soon.

Make sure you have people there to support you because that does help.

Advice for going through surgery

I don’t know if sometimes when things are just so traumatic or stressful, my mind doesn’t allow me to be as rattled as I probably could be. It’s not like I was going in there happy. I had my family with me. I felt comfortable. My parents were there. My brothers came. Everybody who I love was there so that helped a lot.

Make sure you have people, who you care about, there to support you because that does help. When I opened my eyes and saw those people around me, that did help because I knew I had a long journey ahead. They told me that I woke up cracking jokes.

The day of surgery wasn’t really stressful. It felt like everything moved fast. I had to go the day before to do registration. I remember my wife and my youngest daughter were out of town on a Girl Scout trip and they were coming back that night. My mother-in-law actually took me.

I remember getting there that morning. My daughters were with me and we were laughing. One of my best friends came into town [with] his wife from Houston and they were cracking jokes. My dad came.

Right up until the time when they told me we’re going back to surgery, I remember just laughing with my family. I know I was nervous but I just have to stay in that space.

Even before surgery, I just knew it was going to be a success because I knew, without a shadow of a doubt, I was in good hands.

Preparing for surgery

They really did a fantastic job preparing me. Up until the day of surgery, I had learned so much through them.

[During] the period between diagnosis and surgery, I connected with Us TOO, which is an organization for prostate cancer survivors, and they have a chapter in Austin. I learned a lot through them as well.

I felt so comfortable and I think that goes into the comfort level with your doctor or your HCP because I just had no doubt. Even before surgery, I just knew it was going to be a success because I knew, without a shadow of a doubt, I was in good hands.

I feel that changes the trajectory of the healthcare experience when the patient has that real, authentic connection with any doctor that they have to deal with.

Knowing you’re in good hands

I’m an intuitive person. I got my college degree in communications. I’m all about how we engage and how we deal with one another.

From the minute I met that second urologist, it was so evident that he was on my side. It almost felt like I was his only patient if I could just explain it that way, honestly. I felt like he didn’t have any other patients to see after me. I didn’t feel like he saw anyone before me. I didn’t get that feeling of next, next, next. Never. He seemed like his calendar was just open, like he didn’t have [anything] pressing. He was just really locked in and listening to me.

All of that really helped. I feel that changes the trajectory of the healthcare experience when the patient has that real, authentic connection with any doctor that they have to deal with.

Certainly in my culture, there’s nervousness there. It just comes from so many years of mistrust so more doctors need to be intentional about how they engage all patients but certainly patients who look like me because we know we need to get over that hill of mistrust. I just think that Dr. Giesler — who is my urologist, who I love and I talk to him to this day — did that so well.

I know a patient who actually feels like they never had prostate cancer. They feel they were being used as a project. I’m sure they did [have prostate cancer], but they feel this way and it’s primarily because they don’t trust the doctor. Stop the mistrust.

We know that that’s a real thing, like Tuskegee. In a lot of men’s minds, they still feel that that holds true today. I’m not here to say whether it does or doesn’t; I don’t believe it does.

My point with this patient is I’m pretty sure that the reason he feels this way is because he has a severe mistrust of his urologist and the team. I often wonder if he did have a trusting relationship with them, would that change how he felt? Would he still feel that he didn’t have prostate cancer? I’ve never heard someone say that and because I know that he has that mistrust, I’m pretty sure that’s what makes him feel that way.

If you do have cancer or anything else, it’s always better to know earlier than not.

Recovering from surgery

After surgery, I had to wear the catheter for seven days. For me, the catheter was the worst part. It wasn’t fun. Everything else, I could deal with. The catheter was terrible.

On the seventh day, I had to get the catheter taken out. I’m pretty sure it has a lot to do with the fact that I’m healthy and I’m younger. But when the catheter was taken out, I was at my daughter’s softball event that same day. Now, that’s not to say that I was just ready to go sail the seven seas but I was able to attend that. I had a little donut pillow that my wife bought me and I was sitting on that. I was able to walk from the car.

The catheter was the worst. It’s just so bad. They gave me two different bags. One bag I would wear when I’m at home, overnight when I’m asleep. Then another bag, I could be more mobile. It was attached to my leg.

I don’t think there’s anything that helped. I was just ready to get the thing off. All of the rest of it, it’s fine. But the catheter was not my favorite part.

I was back at work I would say six weeks. Maybe seven.

Every patient story is different. I’ve talked to other black men, patients who were maybe three or four years older than me and maybe weigh a little bit more, [and] their outcomes were a little bit different. I go days without remembering that I had prostate cancer. Everything functions on me the way it did. I don’t have issues with incontinence. I’ve never had to wear a diaper. None of those things.

I’m telling you all the positives about my specific scenario just to motivate you to go get checked because if you do have cancer or anything else, it’s always better to know earlier than not. We just have to get away from assuming that we can just ignore it and that it’s just going to resolve itself because that’s not the case.

You can still have an amazing life (wink, wink) after a diagnosis or after surgery. I’ve been disease-free since June of 2019 and I’ve never felt better.

It’s key that we talk about it in families. As a prostate cancer patient or survivor, I make sure everyone in my family knows that I have prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer awareness

If family health history have been discussed, then I would have known about prostate cancer. As a man, because I was going to the doctor, I could have just added that into the conversation.

My doctor visits, when health history is brought up, just like I was aware of my aunt having breast cancer and my grandmother having breast cancer stage four and I share that with the doctor, I could’ve also shared the prostate cancer.

It’s key that we talk about it in families. As a prostate cancer patient or survivor, I make sure everyone in my family knows that I have prostate cancer.

As a black man, as a prostate cancer survivor, I’m just here to tell men everywhere — but certainly, men who look like me — that doctors are here to help us.

I have a twin brother and an older brother who have still not gone to the doctor. I speak out for them. My brothers know I had prostate cancer and they came to my surgery. They know now that our uncle had it. My twin knows that because we’re genetically the same, that makes him at an even higher risk but yet they still haven’t gone.

I had people ask me before, “Why do you think that? Why do you think it is that men don’t wanna go to the doctor?”

When I think about it, the only word I can think of is fear. It could be a fear of the unknown or just don’t want to be poked and prodded. I don’t want people asking me personal questions. I don’t want to have anyone in my intimate space like that. It’s all these factors. Meanwhile, there are questions lingering with your health that go undealt with because of the fact that this fear continues to keep you frozen.

As a black man, as a prostate cancer survivor, I’m just here to tell men everywhere — but certainly, men who look like me — that doctors are here to help us. They are. If you go to a doctor and you don’t like the way they make you feel, I want you to know that you have every right to find another doctor. You shouldn’t have to go to a doctor that doesn’t make you feel comfortable.

It’s okay to speak up when you’re in doctor’s visits if you feel that the doctor is not meeting your needs and meeting you where you are. You need to know that you can certainly speak up and make the doctor aware of that.

If the doctor is still not being intentional about meeting your needs, you have every right to seek out another doctor. That’s something I really want to make sure that I hammer home because a lot of people don’t realize that as the patient, we actually have the power. We have more power than we think we do.

Let’s not be afraid to advocate for ourselves in the healthcare space and to speak up and ask questions so that we can change the narrative.

I used to go to doctor’s visits with my grandmother and the doctor would say something and I’d ask my grandmother, “Are you okay with it?” “Yeah, it’s fine, it’s fine. The doctor said it then that’s what it is.” I’m like, “But are you okay with it?” There’s just this thinking that the doctor knows it all. I don’t know anything.

I’m here to tell you no. You’re there to educate the doctor on who you are. I always say you have to teach people how to treat you and the same applies when you’re with doctors. Let’s not be afraid to advocate for ourselves in the healthcare space, speak up, and ask questions so that we can change the narrative.

If you go to a doctor and you don’t like the way they make you feel, you have every right to find another doctor. You shouldn’t have to go to a doctor that doesn’t make you feel comfortable.

How to address the fear

Two things. First, more unconscious bias training so that doctors and healthcare providers have the tools and know how to engage the black patient.

On the patient side, this is something that needs to be talked about in church meetings, fraternity meetings, in places where black people feel most comfortable because that’s going to essentially be what’s going to get them there. They also need to be hearing it from actual patients, actual black men who who who went through this, who are survivors and can speak to what it might look like in terms of the journey and speaks to the point of early detection.

Once we can get them there, we need to be assured that doctors are going to know how to engage them. It’s not just to start. It’s to stay.

You have to be very calculated. [If they feel like it’s falling on deaf ears again], it might even be worse. “Oh, you got me here and now, see? This is why I don’t even go to the doctor.” Then you will never hardly be able to get them to go after that. This is a combined effort for sure.

This needs to be talked about in places where black people feel most comfortable because that’s going to essentially be what’s going to get them there.

Engaging black patients in a better way

Understanding how we communicate and that connection is critical. Perhaps walking into the room with a black patient and choosing to just talk about regular things. I am not cancer.

I’m only speaking for black people because I’m a black person. We want that because that’s going to be the best way to help us feel comfortable. There is this cloud looming over healthcare when it comes to how black people perceive any capacity of healthcare. The HCPs and people on that side must be vigilant and diligent about making sure to flip that in their daily interactions when they’re meeting with patients.

That’s not just going to happen overnight that’s why training is so important because some doctors need to be trained [on] how to do this. When it comes to tactical recommendations, how would that look? Maybe pamphlets that are provided to HCPs so that they understand, little tips and tricks, and ways to engage the black community.

Getting them there is half the battle but keeping them there is probably the bigger part. “I like those shoes!” “Wow! I like your hair.” A rule of thumb is to treat patients like they’re your parents or your family members even if clearly we’re not of the same culture. Most black people in that healthcare space, we’re tense. We’re uptight. We don’t know what to expect.

My situation is a little bit different because I’ve been going to doctors longer but I’m always wondering. Is it going to be a good experience? Is the doctor going to treat me like a person or like a patient? Yes, we’re going to be a patient but we want to be treated like people. I think that goes for all of us.

When the doctor feels that this needs to be stated, [if] there’s still a little bit of a disconnect, it’s even okay to say, “Listen I know you may have had bad experiences before but not here.” Declaring that [and] then following through in your actions. That can be enough, honestly.

A lot of doctors might take it personally because they feel, “That’s not me.” Most people realize it’s probably not you. It’s the system but this is how you could separate yourself from the system and say, “You’re here with me now. I’m going to take care of you. I don’t know what happened to you previously but you won’t have that here.”

While Tuskegee did happen, we must do our part in ensuring that it doesn’t happen again and the best way to do that is to show up.

Information on and access to clinical trials

I knew what clinical trials were but I didn’t know how [they] all worked. I wasn’t up to date on all the particulars. I knew in general but there needs to be so much more work done in terms of educating the black community on clinical trials and providing access because they don’t even know.

There are so many clinical trials. You can go to clinicaltrials.gov and they’ll show you. But so many people don’t know that. I only learned that rather recently. You can just log on to clinicaltrials.gov, look through the list, and see what’s upcoming, what’s done, [and] what’s still open presently.

Providing access [and] making people aware that that website exists because, like many other things, it makes the black community feel like we’re being purposely left out of these clinical trials.

Efficacy comes into play because we haven’t been included in these. We might be taking the drug and then it doesn’t react the right way because we don’t have any data to show that that would happen.

I want black men and men in general to know that they can be an advocate for themselves. You have a voice because at the end of the day, you are the patient.

Clinical trial, that’s a big buzzword right now. There is a push to try because so much more awareness is being shed on prostate cancer that we may be moving the needle forward in that area.

I would say certainly at the HCP level, in the doctor’s offices, and [in] advertisements… “Did you know that clinical trials are available?” Providing the website so that people can look through that on their own.

I just think so many people don’t know that clinical trials are available and that black people can participate in them. It’s important that we have a seat at that table so that we are able to do our part in the research phase of these different medicines to show how they can help our community.

As a prostate cancer patient, as a black person, I would just tell black people in the community that, yes, Tuskegee definitely did happen. We honor that. But it’s important to know what clinical trials are, to understand how beneficial they are, and to know that that’s not a likelihood now. We’ve done so much better in terms of education and awareness. While Tuskegee did happen, we must do our part in ensuring that it doesn’t happen again and the best way to do that is to show up.

Early detection is the way you can ensure that you have the best quality of life. If my cancer wasn’t found as early as it was, my reality wouldn’t be what it is now.

Being an educator in a different space

When I was diagnosed in 2018, I could have never imagined that I’d be doing this work professionally. I’m meeting with doctors, talking to doctors, and working to spread awareness on a national level and that’s just a feeling that I can’t explain.

I’m able to transfer my skills into this space, having been a teacher for so many years and still actually teaching in higher ed. It feels good to merge my passions with my skills, to do this work, and to be alive and well enough to do it.

At the end of the day, the best thing you can do for yourself is to go to the doctor.

Words of advice

I wasn’t able to go in and advocate for prostate cancer necessarily. I did go to the doctor annually. Had I known about prostate cancer, I am sure that I would have.

At the end of the day, the best thing you can do for yourself is to go to the doctor. You have reasons to be around, whatever they are, whether it’s family or kids, or job. You have a reason to live and you have a reason to live your best life.

Early detection is the way you can ensure that you have the best quality of life. I know that if my cancer wasn’t found as early as it was, my reality wouldn’t be what it is now. I go many days without even realizing that I have prostate cancer and I think that’s just a testament to early detection, certainly because the cancer was able to be contained.

Early detection starts with going to the doctor. You’ve got to go to the doctor. You’ve got to move past those feelings of not being comfortable at doctor’s offices.

No one knows you better than you do so your best bet is to go to the doctor and speak up. If you feel something’s going on, then make sure you tell the doctor about it. But even if you don’t, I would advise all men. Nothing wrong with going in and requesting a PSA test.

Self-advocacy

For me, [the doctor] is going to have to be somebody that gets to know me in an intimate way. I want to feel comfortable with him. That goes along with why I speak out too. I want black men, and men in general, to know that they can be an advocate for themselves, that it’s okay. You can say, “No, I don’t agree with this.” You have a voice because, at the end of the day, you are the patient. That’s pretty much the story with the way I was diagnosed.

Black men are twice as likely to be diagnosed and 2.5 times likely to die. The disease presents itself in more aggressive ways and it remains silent in its earlier stages.

Importance of early screening

I was 37 [when I got diagnosed]. The truth is most doctors aren’t going to be screening for this until you’re 40. I tell men that are about my age that I run into. You can tell the doctor that you would like to have this blood test.

In all cases, if there’s a family history, you should certainly be getting screened. That’s why it’s so important to talk about things because if you don’t, then you’re not going to even know the history to be able to advocate.

Black men are twice as likely to be diagnosed and 2.5 times likely to die from the disease so just being a black man makes it much more important that you get this checked. In black men, the disease presents itself in more aggressive ways and it remains silent in its earlier stages.

For all those reasons, you need to go to the doctor. If you’re not 40, I would say still go to the doctor.

Another real barrier is this macho thing about the whole DRE, the digital rectal exam. First of all, if you have to get that done, you just need to do it. It’s for your life. With advances in technology, that’s not the first option now. The first option is the blood test and obviously, if the blood test reveals something, then that will be probably the next step. I try to make sure men know that because it seems minor, it seems trivial, but I promise you that a lot of men won’t go to the doctor for that reason. I’ve heard that so many times.

God wants you to depend on Him but he wants you to depend on people he’s placed here to do the job as well. The best thing I can tell you is quite simple. Go to the doctor.

While I’m talking about prostate cancer specifically, the overarching message is you need to be going to the doctor because you can’t get screened unless you go to the doctor. You need to be going to the doctor to get a baseline in terms of your health in general.

As a man, you definitely should be getting your PSA checked. If the doctor doesn’t do it, you should be requesting it. Even if you’re not 40. You could be 30. I would still say get your PSA checked because at least you have a baseline. You can do surveillance. It helps you to be more mindful and to be more vigilant about your health.

I still had a part to play in it because I went to the doctor. It was a blessing that it was this particular doctor but still, the fact that I went, I was able to be discovered.

You’ve got to get there. You have to get to the doctor.

Always look for support. If you don’t have any family support in terms of prostate cancer, there [are] support groups [and] mentors that can be provided to you. In terms of health care in general, you can jump on Google, you can research support groups that might be specific to something you’re dealing with. My reality is prostate cancer but I want to really reiterate that health care is of the utmost importance.

If you’re going to get your general health up, make sure that you’re aware of the latest as it relates to your general health. If that includes realizing that they need to do surveillance with regard to prostate cancer or breast cancer, do what the doctors tell you to do. Please don’t ignore what they’re telling you.

If you’ve got the diagnosis, don’t ignore it. We’ve got to get away from that.

I grew up in a Christian household. I love God. I know God. But I also know that God put doctors here to help us. God wants you to depend on Him but he wants you to depend on people he’s placed here to do the job as well. The best thing I can tell you is quite simple. Go to the doctor.

No one knows you better than you do so your best bet is to go into the doctor and speak up. If you feel something’s going on, then make sure you tell the doctor about it.

Inspired by Mical's story?

Share your story, too!

Prostate Cancer Stories

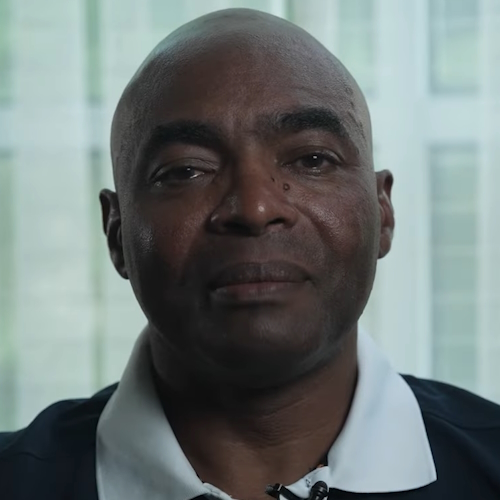

Jamel Martin, Son of Prostate Cancer Patient

“Take your time. Be patient with the loved one that you are caregiving for and help them embrace life.”

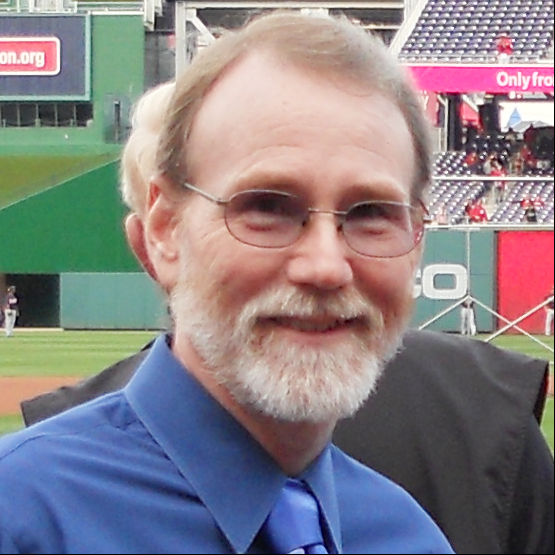

Joseph M., Prostate Cancer

When Joseph was diagnosed with prostate cancer, the news came as a shock and forced him to face questions about his health, future, and faith. He shares how he navigated his diagnosis, chose robotic surgery, and learned to open up to his loved ones about his health.

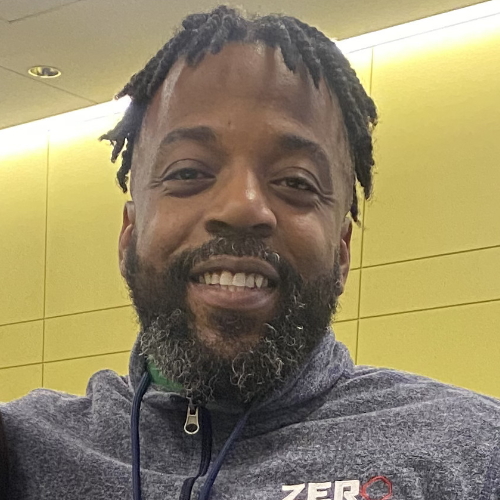

Rob M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Burning sensation while urinating, erectile dysfunction

Treatments: Surgeries (radical prostatectomy, artificial urinary sphincter to address incontinence, penile prosthesis), radiation therapy (EBRT), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy or ADT)

John B., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9, Stage 4A

Symptoms: Nocturia (frequent urination at night), weak stream of urine

Treatments: Surgery (prostatectomy), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy), radiation

Eve G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels detected during annual physicals

Treatments: Surgeries (robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy & bilateral orchiectomy), radiation, hormone therapy

Lonnie V., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Urination issues, general body pain, severe lower body pain

Treatments: Hormone therapy, targeted therapy (through clinical trial), radiation

Paul G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery), radiation, hormone therapy

Tim J., Prostate Cancer, Stage 1

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery)

Mark K., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptom: Inability to walk

Treatments: Chemotherapy, monthly injection for lungs

Mical R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 2

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level detected at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Jeffrey P., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; routine PSA test, then IsoPSA test

Treatment: Laparoscopic prostatectomy

Theo W., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level of 72

Treatments: Surgery, radiation

Dennis G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9 (Contained)

Symptoms: Urinating more frequently middle of night, slower urine flow

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Lupron)

Bruce M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4A, Gleason 8/9

Symptom: Urination changes

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Casodex & Lupron)

Al Roker, Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7+, Aggressive

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level caught at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Steve R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4, Gleason 6

Symptom: Rising PSA level

Treatments: IMRT (radiation therapy), brachytherapy, surgery, and lutetium-177

Clarence S., Prostate Cancer, Low Gleason Score

Symptom: None; fluctuating PSA levels

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)