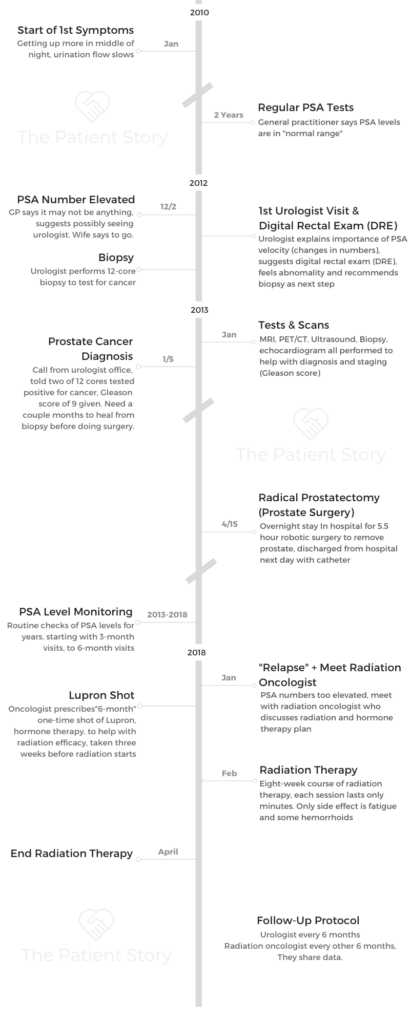

Dennis’s Gleason Score 9 Contained Prostate Cancer Story

Dennis shares his prostate cancer story, Gleason score 9, which began when he was diagnosed at 70 years old. He describes treatment, from a radical prostatectomy, hormone therapy with Lupron, and radiation therapy.

In his in-depth story, Dennis also highlights navigating life with side effects from the Lupron shot, the importance of men speaking more about their health and fighting the reluctance to talk about prostate cancer, and also addresses the top questions he gets from patients and caregivers. Thanks for sharing your story, Dennis!

- Name: Dennis Golden

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Prostate cancer

- Gleason score 9

- Contained

- Age at DX: 70

- 1st Symptoms

- Urination flow slowed

- Urinating in the middle of the night a couple of times

- Treatment

- Surgery to remove prostate (radical prostatectomy)

- Hormone therapy

- Lupron shot, 6-month dose that lasted 14 months

- Radiation therapy

- 8-week course

I think a lot of men suggest their masculinity is tied to erections. I’ve met men who said they were diagnosed with prostate cancer, but they were concerned about the impact to their private parts, so they weren’t going to seek treatment.

Then what happens is a couple of years later, we see them in the support groups saying they should have done something. They had no idea the consequences.

It’s a masculinity thing. “I don’t want to admit a weakness in any way,” and if I say I have prostate cancer, I’m less of a man than I used to be.

If the only thing that’s defining your manhood is your penis, then I think you have an issue and it’s a greater issue than prostate cancer.

Manhood has to do with a lot more than one part of your body. It’s hard for a lot of guys.

Dennis Golden

- Video: Dennis on Getting Diagnosed

- Prostate Cancer Tests

- Getting Diagnosed

- When did you learn the prostate cancer diagnosis?

- How did the urologist describe the Gleason score?

- Staging is the Gleason score

- Making sure you take the right PSA test

- How did you process the diagnosis?

- How did you tell your wife about the diagnosis?

- Guidance to others on breaking the news to love ones

- The need to share the news and talk openly about prostate cancer

- How did you think through treatment options?

- Did you get a second opinion?

- Video: Dennis on Getting Treatment

- Surgery (Prostatectomy) & Recovery

- Monitoring PSA Levels

- Hormone Therapy

- Radiation Therapy

- Video: Dennis' Reflections & Advocacy

- Reflections

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Video: Dennis on Getting Diagnosed

Prostate Cancer Tests

Introduction

I’m married with a couple of kids, who are all grown adults, successful, and living in various parts of the country. We’re in Connecticut enjoying the beginnings of the winter, so it’s a fun time. I also have a dog.

I was diagnosed in 2013 with prostate cancer. It was then I began realizing that so many men had really no idea of what prostate cancer is, the fact that they even have a prostate. I got together with a buddy of mine, and we started the National Prostate Cancer Awareness Foundation.

What we were finding was people were not focused on cancer awareness. Rather, organizations focused on people who had cancer, or they were rising money for cancer research

But no one was talking to guys about wake up, you need to get an annual checkup, so that’s the initiative we started.

What were the first symptoms?

I was finding that I was getting up a little bit more at night, once or twice in the middle of the night, which I had never done before. The urine flow seemed to be a little bit slower.

I went to my general practitioner and said some things seemed to be happening. He said at my age, it was probably just an enlarged prostate. So he gave me some medication to help the urine flow.

In the meantime, I had already gone through with that general practitioner a digital examination. I had been going through regular annual physicals, so he was watching my PSA numbers all along and kept saying that I was in the normal range.

When you’re a guy and the doctor says you’re in the normal range, you say, “That’s great, bye now. I don’t need to ask anymore questions.”

When did you finally go to a urologist?

That kept going along. He kept saying it was normal range. It was 18 months after that started when I went in one time for an annual physical.

He said my numbers were still in the normal range but they were getting on the high side. He added I might, and I repeat “might,” want to go talk to a urologist.

I said to my wife, ‘I might want to go to a urologist,’ and my wife said, ‘No, you want to go to a urologist.’

So I went to see one with all the fear of going in. As somebody joked with me, “This is going to be your first butt-mitzvah.” It was a great expression!

The importance of PSA velocity

We had a conversation, and the urologist said a couple of things. He said so many times general practitioners will say you’re in a normal range, but what they’re failing to recognize is something called PSA velocity.

Velocity means that your numbers are going up on a steady basis. He said a normal range may be normal, but velocity is something that really needs to be watched.

He added probably 90% of men have no idea. They look at a number and say that number is low. Your general practitioner can be the same way, and it depends on what kind of training they had.

Over the course of my illness here, I’ve discovered there are general practitioners who say it’s okay for a guy to have a PSA of 2, 3.5, 5. It really depends on what that physician has read and what the trigger number is for him or her.

What the urologist pointed out was that there’s no “magic number.” There’s no point where you say, “At this number, you see the urologist.” You want to see if that velocity is rising. If it’s rising, you want to see a urologist, which I did.

Describe the digital rectal examination (DRE)

It got to a point where he suggested a digital examination. I asked where the computer was and he said, no, a digital examination. I now understand “digital.” That digital exam was quite different than anything I’ve had with a general practitioner.

The GP probably does a routine check. The prostate is a difficult gland to examine. Many times the irregularity, if you will, appears on the backside of the prostate. Your general practitioner may or may not feel it.

What happens is I had the digital examination, and in the process, it felt like my ears got cleaned out, too. The joke ended when he said he felt an irregularity. My heart sank.

The next step was a biopsy

After feeling the prostate irregularity, the urologist said we needed to do a biopsy. I wondered how we’d do that, so I started to do research on how the biopsies were done.

Describe the biopsy

They use a form of novacaine, which was a little bit of a joy to have at the start. They started to do a scan, and I could actually see the screen. I could see there were red spots that were showing up in two areas.

They did the biopsy, a 12-core biopsy. Of the 12 cores, two were positive for cancer. They said they’d get back to me with my Gleason score.

If you can imagine a golf ball on a stick, that’s basically what’s inserted. In that golf ball, they have the ability to fire a needle. That needle can inject novocaine.

From there, they can take the biopsy. Typically, most places take 12 samples and try to use some sort of guidance system to find out where the hotspots are. Some hospitals take as many as 24 cores in the biopsy. You’re anticipating that needle hitting X number of times, and it gets a little “exciting.”

Some of them were fine; some of them were a little “engaging,” shall we say. When it’s over, they say to take some antibiotics to avoid an infection, because the area they’re working in with puncturing the rectum can lead to an infection.

After it, you may have some bleeding, which I did. All that is distressing to say the least, but then everything calms down, and you wait to hear the news.

Getting Diagnosed

When did you learn the prostate cancer diagnosis?

I’m down in New York City a week or two later, driving back to Connecticut, and my phone rings. It was the urologist’s office.

Office: “We just wanted to let you know you have prostate cancer.”

Dennis: “Okay. Is there anything else you can tell me?”

Office: “Just that it’s kind of aggressive.”

Dennis: “What do you mean by aggressive?”

Office: “Well, out of a 10, you got a nine.”

Dennis: “I guess at least I’m not a 10.”

So I spent the next two hours driving from New York City back to Connecticut with that information. I didn’t know what to say to my wife when I came home.

»MORE: Read different experiences of a cancer diagnosis and treatment

How did the urologist describe the Gleason score?

It’s out of 10, but it’s a combination of two numbers. Mine happened to be a 4/5 and a 5/4, so they were quite high. The good news was it was confined to one side of the prostate and only two of the 12 cores were positive for cancer.

It was a high score contained within the prostate. That’s what they felt, and the issue was they wanted to let me heal before they could do the surgery (prostatectomy).

Staging is the Gleason score

If you have a Gleason score of six or less, it’s considered a slow-growing cancer. My business partner, who was diagnosed several years ago with a Gleason score of six, had surgery. That was 15 years ago.

He has had no recurrence at all. But he still goes to the urologist every year and keeps checking to maintain that ongoing system in place.

I have another fellow I was working with who went to his regular GP afterwards. His GP kept saying that his numbers were normal and not to worry about anything. At one particular point, his GP said his PSA levels were up to a 2 and maybe he should get his prostate checked.

He responded that was an issue because he was operated on, didn’t have a prostate, and didn’t have one for six years. The advantage here is if you’re dealing with this cancer, you really want to continue with a urologist and be sure that the type of PSA tests they’re taking or doing is an ultra-sensitive test.

Making sure you take the right PSA test

There are two levels of PSA testing. One is the normal testing. But after surgery (prostatectomy), they do an ultrasensitive test. You are getting readings in the 0.01, 0.02 range, so it’s quite different.

How did you process the diagnosis?

I’m not alone. I’ve talked to so many men who’ve had similar situations or worse. Some of them say the doctor called up to tell them to go into the doctor’s office, that they needed to talk, but that the earliest appointment was in two weeks.

You’re sitting at home for two weeks waiting when you know there’s an issue, and nobody will talk to you. I don’t know which is worse: hearing it quickly and getting the information and saying okay, or you hang there by your fingernails and wonder what level the problem is.

Doctors deal with this all the time. For them, it’s prostate cancer, and we’ll take care of it. For the patient, it’s, “I have what? I have cancer?” And it scares the bejeezus out of you, and you panic.

I think we all know when you hear the word “cancer,” it’s quite different. I’ve said this a number of times. If you know someone who has cancer, that’s one reaction. If someone says to you that you have cancer, it’s a whole different reaction, believe me.

»MORE: Processing a cancer diagnosis

How did you tell your wife about the diagnosis?

I came into the house, broke down, and cried.

I told her I had bad news. That was it. It was an emotional discharge. I had been building it up for almost 2.5 hours.

As soon as I walked through the front door, she looked at me and knew something was wrong.

Guidance to others on breaking the news to love ones

It’s a tough situation. Guys ask me about this all the time. I said there are really two ways to look at it.

If you have a good relationship with your partner, you’ll probably share the information pretty quickly. If you’re about to have a divorce, you may not want to share this information, and you may want to do some things to protect assets.

I met a man across the street from me who was diagnosed with prostate cancer and didn’t want to tell his wife. He didn’t want to say anything about it or talk about it. If she asks him any questions, he replies that he’s dealing with it.

There are men who feel that they want to keep it a big secret; there are men who say they need to share the information.

A lot of the support groups that I run and a part of what I find is that most men, after they’ve been diagnosed or after they have surgery, are more willing to talk about it. But up until then, they’re frightened of it.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

The need to share the news and talk openly about prostate cancer

I had a financial advisor for some years. When I was going through my surgery, he said he’d visit me at the hospital. I was in and out in a day, so he didn’t get a chance to.

About three months later, I found out he’s dying of prostate cancer. He never said a word. He never said to me that he was going through the same experience. He didn’t want to say anything because he was afraid his clients would abandon him.

Some men don’t want to appear weak. They don’t want an employer to say there’s a problem and let them go, so there’s a lot of fear with men.

It’s a balancing act depending upon your lifestyle and where you are in relationships with an employer, as well as family members.

I’ve been meeting so many men who have been through this. I hear different stories. I had one man say to me that he had prostate cancer, and his wife wanted a divorce.

She said that he couldn’t “fulfill the marital contract anymore,” and since he couldn’t do that, she wanted a divorce. It was a strange occurrence. You run into all kinds of stories.

“If you’ve been diagnosed with prostate cancer, don’t waste your time and energy on the negative part of it. Trust your doctors. Trust whatever healers you end up with. Trust your men’s support group and most of all, trust yourself. Trust that you will find a way through this journey.'”

Paul G.| Explore Paul’s Prostate Cancer Story

There’s no simple answer.

How did you think through treatment options?

When you go into a doctor, you normally have a cold or flu. They give you medications and drugs, tell you to stay home, drink tea, have chicken soup, and you’ll be fine.

With prostate cancer, the doctor asks, “Which treatment do you want?” Here you sit with your family, uninformed medically, being asked which decision do you want to save your life.

You start out with what are the advantages and disadvantages of surgery? What are the advantages and disadvantages of radiation? I asked whether I could do brachytherapy, which is type of radiation therapy involving seed implantation. They said I couldn’t do that.

Another option was “watchful waiting” or “active surveillance.” The problem with that is if you had an aggressive cancer, watchful waiting isn’t really something smart to do. Brachytherapy was not an option because mine possibly might be an advanced cancer, so no seed implants.

I had two options: radiation therapy or surgery, prostatectomy. I asked if I did surgery, could I do radiation after? They said yes. I asked if I did radiation, could I do surgery after? They said it was very difficult or almost impossible to do.

So I decided on surgery first.

Did you get a second opinion?

I did get a second opinion and asked the same thing. That doctor confirmed what it was and also offered surgery or radiation as solutions. Again, no one would make the recommendation. You have to choose your own course of action.

There’s a doctor named Patrick Walsh who has written several books on prostate cancer and is considered one of the leading, cutting-edge physicians for prostate cancer.

He has written a great book. My suggestion would be to read that. It’s thick, and it’s a big book. It looks like you’re reading “War and Peace,” but he covers every aspect of prostate cancer. To sit down in the calmness of your home and go through it is a very valuable thing to do.

Video: Dennis on Getting Treatment

Surgery (Prostatectomy) & Recovery

What was the prep going into surgery?

The preparation at that time was to allow my body to heal after the biopsy. They felt that took several months to do. I had the biopsy in January, and it wasn’t until April 15th when they decided to do the surgery.

Describe the day of surgery

It was April 15, which I refer to as a “doubly taxing day.” I went into the hospital, and I left my prostate in Hartford, Connecticut!

I arrived at the hospital early in the morning. They told me that I had to do a bowel prep. Today, that’s no longer required at the same hospital. So I did the bowel prep and got into the hospital.

I got there at 7 in the morning. Somewhere at around 4 in the afternoon, they decided to do the surgery, so it was a long wait. It was 5.5 hours of surgery. I had robotic surgery. There were 5 cuts made across the stomach because they were going across the stomach muscle.

What I didn’t realize is that when the surgery is done, you are tipped. Your entire body is inclined at about a 45-degree angle, head down, during the surgery so they can get into where they need to get into. Sometime around 10 o’clock at night, I was back in my room.

I had spoken to my wife. She said the doctor thought he got everything, and it looked like the cancer was contained. They were very pleased with the results of that.

You needed to move around after surgery

Around 2 o’clock in the morning, the nurse came in to take my temperature and do the things nurses do at that time, waking you up. She said that at some point, if I wanted to take a walk, let the nursing staff know. I suggested that moment, and she said okay.

So it was 2 in the morning when I took my stand with my IV, along with the nurse, and we started walking down the hallway. She advised me not to look down because I’d get dizzy. Being a guy, what did I do? I looked down (laughs).

That was not a good idea! I got a little faint and was able to hold on and make it. I did walk around pretty well. After that, I got back in bed and fell asleep.

The transition from hospital to home

The doctor came in the next morning around 10 o’clock and said it looked like I could go home. I was like, “You’ve got to be kidding me.” I had drains off the side of me; I was hooked up to IVs.

Even though they said it would be overnight, psychologically, I was not prepared to go home.

They got the drain out, which was an “exciting” experience. The drain was in my side. They pulled that out, and I could feel the whole thing unravel as it was coming out.

I was also hooked up to a catheter, so you have all that going on, and had to drive home. It took me and my wife about a half hour to get home.

Tip: Use the larger catheter urine bag for the drive home

What I would recommend to guys is if you’re hooked up with a catheter and you have the urine bag attached to that, use the larger bag. Don’t use the one that’s on your leg. Sitting in a car, you can get some back flow, which is not good.

If you get stuck in traffic, you’ll appreciate the larger bag versus a small bag, which gets full fast. The hospital gives you two bags. One is an overnight bag. The other is a leg bag.

One of the things I thought was, ‘What do I do with this when I get home?’

Recovering at home

I got back to the house with the urine drainage leg bag on, thinking, “Thank goodness I made it.” I emptied the bag at home. We live in a two-story house, a colonial. Bedrooms are upstairs.

I was able to walk up the stairs, which shocked me. I thought that wasn’t too bad. But what I did notice is that I have difficulty lying down in bed, because when they do the surgery, there’s pressure on your stomach.

That meant lying in bed that first night was not a good idea. I came back downstairs and slept on a recliner. The following night I was able to lie down.

Then the question was what do I do with the urine bag? What I did was put two pillows next to me on the opposite side, then put the urine bag on the floor in a bucket, and hoped it worked. It did. I woke up the next morning in the same position, so that worked rather well.

Then it was a matter of everyone saying I couldn’t eat until I started passing gas, so I started moving. I walked down the end of our driveway, which is about 150 feet long. I went down and came back a couple times. For a couple of days, more and more gas was being passed, so they said I could start to eat food.

I was then able to move away from the applesauce and chicken soup and actually have eggs.

It was just the first night. The second night, I was fine and had very little pain.

Removing the catheter

A lot of guys are concerned about the catheter coming out. I will say that it comes out very quickly. There’s a small bulb inside that inflates. When it’s coming out, they deflate that bulb, and the catheter just slides out.

You don’t even know that it came out. Don’t be afraid of it, guys!

The catheter came out 10 days later, and they want to make sure you have equipment with you to take care of that because you will leak after surgery. I didn’t really have urine control for about three months.

After that three-month period, I started to be dry at night, and then slowly I started to get dry during the day. Finally, about at the six-month mark, I found that I was dry and able to be in pretty good shape.

They had encouraged us to do kegel exercises, which are exercises for your bladder and bladder muscles, pelvic floor muscles. That helped dramatically.

I was pretty religious about doing them. I was also very religious about not overdoing them.

I’ve had a couple of guys we’d talked to where we said if we do ten at a time, why don’t we do 20? And instead of doing them four times, why don’t we do it ten times?

What happens is you overexercise the muscle, and you have more leakage. You really screw yourself up by overexercising. It’s so hard for guys to do that. We know much better than they do! (Laughs)

Any more guidance on the catheter?

The catheter is a pain in the ass, to be blunt. If you are careful with it, some guys get some irritations. You can put some Neosporin or that type of medication where the catheter is inserted.

The biggest thing is anytime you’re touching any of the connectors, your hands are spotless, washed, and that you really use some type of an alcohol swab on all the connectors so that there’s no danger of infection.

A friend of mine actually had an infection and wound up keeping the catheter in for almost a month. It’s much better to get it taken care of for the 10 days after surgery. Be a nut case in terms of cleanliness and using alcohol wipes on everything.

Monitoring PSA Levels

What was the follow-up like post-surgery?

After the catheter came out, it was several weeks later when they had me go back in for a general checkup, and also for a follow-up PSA test. They said I looked good at 0.01.

Then we kept doing that every three months, then bumped to every six months. I kept on the six-month schedule. Very slowly, over the next year, it got to one year, and then my PSA started to slowly rise from 0.01 to 0.02. No alarms yet.

Until I got to 0.03, and the doctor said we may want to watch this. That went from 2014 to 2018, with a slowly rising PSA.

Dealing with the worry of relapse

I wasn’t worried. You think to yourself, “Doctors do great things.” They say things like, “We got it. You’re cured.” I think the biggest concern, and I’ve heard this a number of times, is when you have cancer, you’re not cured. You’re in remission.

I think if physicians and patients could also realize someone says you’re cured, translate that to, “You’re in remission for now. Let’s see how long this lasts.” It may last a long time. It may not last a long time.

I think doctors are anxious to have you feel better emotionally.

Candidly, after the surgery, within five weeks after the catheter was removed, I was back riding a bike 25 miles a day. Two weeks after that, I was back kayaking. So picking up a kayak, putting it on top of the car, and kayaking was not a problem.

My recovery was fast, but anytime you’re diagnosed with cancer, in the back of your head, you might think it’s still there. There was always a worry about a recurrence, especially with a high Gleason score, which is anything seven and above (7+).

Guys may say it’s only a seven. My neighbor across the street had a Gleason score of seven. He had the surgery, and just after the surgery, about a month and a half after, he went back, and they said he needed radiation and Lupron (hormone therapy).

They go on a case-by-case basis. Everybody’s an individual, and that’s how you have to look at it.

It’s not one case fits all

I always say prostate cancer is like a fingerprint. How it impacts you is unique to every one of us. The other side of this is prostate cancer is not a single disease. There are many variations of prostate cancer and different types of it, so that’s something to be aware of.

Get more information about your cancer

I never got more information about my type of prostate cancer, and I didn’t know that I should get it back then. My recommendation is to find out.

The other thing I’d say to anybody reading or listening is sit down with your doctor and get as much of an explanation as you can. More importantly, grab a copy of your medical record.

Grab a copy of anything the doctor has notations on. Get copies of it. Put it in a file because you may need it a year from now, or you may need it five years from now. You may need it to sit down with your son or daughter or grandchild to talk about it, because the same genes that impact prostate cancer are the same genes that impact breast cancer.

When did you realize you probably needed more treatment?

I was watching the numbers rise. At the time, the guidance was before your PSA gets to 0.2 is when you want to do something. Today, that number is 0.1.

As my numbers started increasing, it got to 0.13. The next step would have been 0.15, 0.16, 0.17, then finally go to a 0.2. So that was it; I had it in my head.

I said, “Let’s start to look at this and get something accomplished.” That’s when I met with my radiation oncologist.

Hormone Therapy

Describe meeting the radiation oncologist

That scared the bejeezus out of me because now you’re sitting there with a guy who wants to microwave my insides. It was like, “Do we really need to do this?”

Then we started talking about Lupron. He said it was a hormone shot that would decrease my male testosterone levels and probably make radiation more effective for me.

I asked how long the shot would last. He said there was a one-month shot, a three-month shot, and a six-month shot. In the back of my head, being a guy, I said, “Okay, let’s do the one-month shot.”

Describe the Lupron shot

I went to my urologist, who gave me the Lupron shot. He said to try the six-month shot, so that’s what I got. That shot lasted 14 months, lasting a very long time with me.

I think if they’re going to give you shots on an ongoing basis, they probably use the one-month or three-month shot. This was supposed to be a one-time shot that would activate in my system.

What were the Lupron side effects?

I was having depression, hot flashes. I was having night sweats, I would break out in tears for no reason at all, and I would be shaking cold one minute and hot the next minute.

When I said I had night sweats, my wife just looked at me and said, “Yup.” She said, “I know all about hot flashes, dear. Now you know what it feels like!”

No woman on the planet was sympathetic to me at all! The hot flashes went on for some time. There was also muscle weakness. The other thing is I gained a tremendous amount of weight. I went from 165 pounds to almost 190 pounds. That was within a five-month period of time.

They said once the Lupron wears out of my system, I’d start to lose weight. I did start to lose weight at about 14 months.

»MORE: Read more patient stories of hormone therapy

Finding the silver lining

The good news is you don’t have to wear deodorant while you’re on the shot because everything is shut down. I actually heard it from another guy who said I wouldn’t need to use deodorant on Lupron, and then one day I tried it and realized it’s true. You don’t need it. I looked at all the money I saved on deodorant!

Any last guidance on what might help relieve some symptoms from hormone therapy?

There are guys in a support group who have had Lupron and said nothing happened. They didn’t feel a thing. There are other guys who’ve gone through it and said they had the same issues I did.

I think a couple of things here. One, exercise helps. Some of these guys don’t want to do exercise, but can get out, get fresh air, and get out and walk. If you can do nothing else, get out and walk.

Getting out into nature, getting some fresh air, changing your environment, and getting yourself out of the house are all helpful. If you focus on the radiation, you’re going to have more problems, and you’ll focus on your hot flashes.

Something else I found really helpful was I got a small fan for the hot flashes. I got one that you could put water in.

The combination of the evaporation of the water on your face plus the fan helped, particularly in the summertime when it was 90 degrees outside and I had a hot flash. A fan doesn’t work, but when you put water in there and have the evaporation, it helps a lot.

The key with it all is to just keep moving and keep active with it. That’s the best advice I can offer.

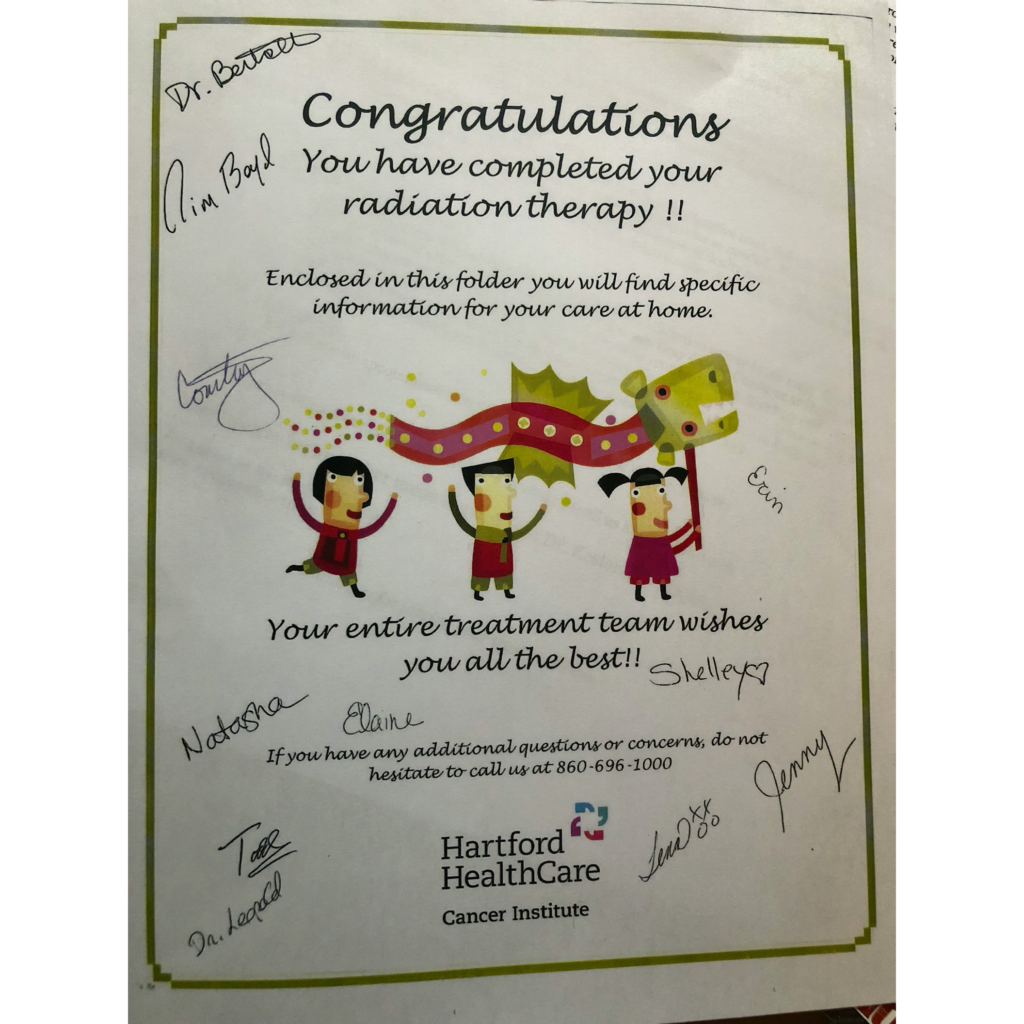

Radiation Therapy

The Lupron is set to help with radiation efficacy

The Lupron shot was three weeks in advance of the radiation so that it got into my system. Then they started the radiation.

Radiation itself, which I did now know, is not an immediate treatment. It takes anywhere from 18 to 24 months for it to work. The idea of the Lupron is it sits in your system, helping the radiation to be more effective in terms of killing off the cancer.

Prostate cancer divides very slowly, so what you want to be able to do is the Lupron is making it weak and the radiation is saying to the cancer, ‘You don’t want to reproduce anymore. You want to go away.’

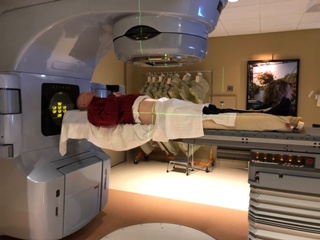

Describe the radiation sessions

The radiation therapy was an eight-week course, five days a week (no weekends). When you first start, it’s depressing, You walk in there, and the first time you go in, they put you down on a table and line everything up to figure out where they’re going to fire the radiation at you.

You get three tattoos so they have targets to line up with. Then they put you in a body cast that holds you in place. You leave there wondering what you’ve gotten yourself into. Then two weeks later, the doctor comes back and says, “Okay, we have our plan of attack all set.”

You go in, and the first time I went in, I was really sweating it. They told me to lie down on the table, and within three minutes, it was over.

I was like, ‘Is that it? You’ve got to be kidding me.’ The radiation itself was really nothing.

The thing that was disconcerting at first was they said I had to have a full bladder. What does a full bladder mean? How full is full? You’re trying to lie on a table and be still with a full bladder, which is “exciting” to do.

After a while, I realized that a full bladder didn’t have to be overflowing, full bladder. It could be partially filled. The technician can also look through the system and see how full you are, also moving your body to do what they needed to do.

I realized after a while that if you were three-quarters full, you were in pretty good shape, and they were pretty happy with it. If you weren’t, they’d chase you out and say, “Go out for a cup of coffee.” So you’d have your cup, go back in, and start it again.

I discovered that only after an interesting situation. I was at the center ready to be radiated, and they lost power. They had to restart the machine, which took three hours. Having a full bladder for three hours was not going to work! They said to me that was the way they did the procedure.

I would suggest to anyone going for radiation for prostate cancer, when they say “full bladder,” be reasonable. You should be all right, versus trying to overdo it.

Were there any radiation side effects?

I was a little bit tired, but I really felt nothing. What amazed me is I would go in, get back to my car, and my car would still be warm in the middle of winter. That gives you an idea of how fast it was.

It was not a problem. It was in and out. My neighbor who went through the same thing said he experienced the same thing, in and out.

There are some people who have trouble with it. I did have some issues with hemorrhoids because the radiation can irritate that area. The application of some cream seemed to make them go away pretty well.

»MORE: Read other patient experiences with radiation therapy

How has the follow-up been since radiation?

So far, so good. My PSA continues to be at a 0.02, so hopefully it stays there. My next appointment now will be in April, and I’ll go back to see the radiation oncologist and see what those numbers look like.

I’ve been going through some chemotherapy, so whatever may have been coming back in my system for prostate cancer is probably being held under control by chemotherapy. We’ll talk about that another time.

Note: Dennis was later diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Video: Dennis’ Reflections & Advocacy

Reflections

Message to men on taking care of their health

The problem boils down to men not wanting to go to doctors, period. Women, when you reach a certain age or your cycle changes at one point, you’re seeing a gynecologist. You moved away from a baby doctor into an adult doctor.

What happens with men is we move away from the pediatrician and say that’s kid stuff. We no longer need to go to doctors. We’re now men. You’re told all along, ‘You’re a man. Stand up for yourself. Don’t be a crybaby,’ etc.

The whole male culture is one of “I can’t be a victim” in many ways. So to admit you need to go to the doctor is strange. Many times, I’ll ask these men who come to me for support, “What is your primary responsibility?”

They say it’s to support their families and take care of their children. I ask what happens if they’re dead, and then something kicks in that yes, that would be a problem.

Prostate cancer and many other diseases — whether you’re dealing with high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes — a lot of these ailments don’t show any warning signs until it’s too late. What guys do is ignore the situation, and then they’re trying to be treated in an advanced stage.

»MORE: Read more from a prostate cancer caregiver perspective

The thing I say to men is you need to take responsibility for your personal health.

That doesn’t mean you go to the gym or play football with the guys, and you’re healthy. Or that you run around on a track or ride a bike, and then you’re healthy.

That means you go in for some type of routine program, whether on an annual basis or every two years. You need to get checked. It’s for two reasons. One, physically, to see what’s going on. But more importantly, you’re also developing a relationship with your family physician, who has a history of you and an idea of what’s going on.

When you go into a GP’s office, 20 minutes after you’re gone, he’s seen four other patients. You’re not top-of-mind awareness. You really need to have that relationship built with the doctor.

The other side of it is you need to ask questions. Most guys I talk to want to just get out of the doctor’s office.

If a doctor says to you that you don’t need a PSA test, walk the other way. You’ve already given a blood sample; just let them add the PSA testing.

If the digital exam is required, my recommendation is to go to a urologist because your average general practitioner does not have the skillset a urologist has for checking your prostate for cancer.

It’s a matter of guys taking responsibility for their personal health. Women do it all the time. We don’t. If you look at the statistics, women live longer than men. They talk to other women about issues that they’re having in terms of health, and they talk to doctors.

Men don’t talk to anyone. We don’t want to say anything; we don’t want to admit anything. For any guy, you go into a men’s room, and you’ll see guys standing by the urinal and struggling. You almost want to say to them, “Have you been to a doctor?” And they don’t want to go. I’m also not about to ask them at that point (laughs) or hand them my business card.

Guys are basically dumb when it comes to this. There’s no other way to say this. You have to get in and be proactive.

There’s additional reluctance talking about prostate cancer

Very much so. I think a lot of men suggest their masculinity is tied to erections. I’ve met men who said they were diagnosed with prostate cancer, but they were concerned about the impact to their private parts, so they weren’t going to seek treatment.

Then what happens is a couple of years later, we see them in the support groups saying they should have done something. They had no idea the consequences.

It’s a masculinity in that “I don’t want to admit a weakness in any way,” and if I say I have prostate cancer, I’m less of a man than I used to be. If the only thing that’s defining your manhood is your penis, then I think you have an issue, and it’s a greater issue than prostate cancer. Manhood has to do with a lot more than one part of your body. It is hard for a lot of guys.

What’s the age range of patients you’ve helped?

The youngest man I worked with who had prostate cancer was 30 years old. What you wind up with is prostate cancer was always considered an old man’s disease.

What we’re finding now is men in their 40s are getting prostate cancer. That is increasing.

If you look at the numbers, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force some years ago suggested men didn’t really need to get their prostates checked. That went on for a number of years.

What suddenly began happening was one of the first organizations that really supported that was the Veteran’s Administration (VA), saying men don’t have to get checked any longer.

They started finding that the number of cases were dropping because men weren’t getting checked. The other thing that started happening later was the number of advanced cases went through the roof. You were seeing that, and now there’s a shift of maybe you do need to get checked.

Generally, I think if you’re in your 40s and you’ve had someone in your family who has had prostate cancer and/or breast cancer, because the genes are related, you need to start getting yourself checked.

We’re seeing a trend nationally and worldwide of men in their 40s getting prostate cancer and not wanting to go to the doctor. I probably know right now 10 to 12 men in their 40s who have prostate cancer. It’s not all men in their 50s and 60s. Yes, guys at that age do get it.

But again, the youngest guy I knew who had it was 30 years old. It was through a mistake that was made on his blood work that they ran the PSA test, and the numbers were through the roof.

The doctor said the numbers were extremely high for his age and recommended seeing a urologist, who checked him over, did a biopsy, and found he had advanced prostate cancer.

You’re not ‘safe’ at any age. You really need to get checked. When this starts, there are no symptoms, when it’s most treatable.

What are the top questions patients ask you about?

The top concerns come down to, “I think I have a problem, but I don’t want to go to a doctor.” So what we did with the National Prostate Cancer Awareness Foundation, that really talks about the general awareness of prostate cancer.

What we also did was start the Prostate Cancer Coach, where we have men who have had prostate cancer available to talk to you online.

There we find we have wives calling up. We have partners calling up saying, “I can’t get him into the doctor. I can’t get my husband and my partner or grandfather in to see the doctor.”

They have all kinds of questions on how to motivate that person to go in and get checked. We spend a lot of time with that.

Guys are reluctant to talk about any of the symptoms, so if you ask, “How is your sex life?” “It’s fine.” Because he can’t get an erection or is having a problem getting erections.

We say it may be prostate cancer or it could be a heart condition. Do you want to die of a heart attack? “No, I don’t want to do that.” Then you can bring them in.

The thing I find is the most powerful tool is when we talk to the women in men’s lives and say, ‘Try to motivate him. Talk to the family. Don’t talk about bringing him to the doctor, but talk about we need you, we need your support of the family, and the children will miss you.’

If the guys don’t realize by ignoring their health, children will lose fathers, grandfathers will lose grandchildren, wives will lose spouses and partners, and families lose financial support. It’s a terrible legacy for no reason other than guys being dumb about it.

Your last message

You are not Superman. You are not indestructible. The majority of men who have prostate cancer don’t realize how deadly it is. We all hear prostate cancer is a cancer men can live with. It’s the “good cancer.”

Well, tell that to the 30,000 to 40,000 men a year who die from prostate cancer.

If you’re driving along in your car and your check engine light comes on, you don’t unplug the bulb. You say okay, I have to do something.

When you have a PSA test and your numbers are high, that’s your warning light. Don’t unscrew the light bulb. Go and get yourself checked.

Inspired by Dennis's story?

Share your story, too!

Prostate Cancer Stories

Jamel Martin, Son of Prostate Cancer Patient

“Take your time. Be patient with the loved one that you are caregiving for and help them embrace life.”

Joseph M., Prostate Cancer

When Joseph was diagnosed with prostate cancer, the news came as a shock and forced him to face questions about his health, future, and faith. He shares how he navigated his diagnosis, chose robotic surgery, and learned to open up to his loved ones about his health.

Rob M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Burning sensation while urinating, erectile dysfunction

Treatments: Surgeries (radical prostatectomy, artificial urinary sphincter to address incontinence, penile prosthesis), radiation therapy (EBRT), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy or ADT)

John B., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9, Stage 4A

Symptoms: Nocturia (frequent urination at night), weak stream of urine

Treatments: Surgery (prostatectomy), hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy), radiation

Eve G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels detected during annual physicals

Treatments: Surgeries (robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy & bilateral orchiectomy), radiation, hormone therapy

Lonnie V., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Urination issues, general body pain, severe lower body pain

Treatments: Hormone therapy, targeted therapy (through clinical trial), radiation

Paul G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery), radiation, hormone therapy

Tim J., Prostate Cancer, Stage 1

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery)

Mark K., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4

Symptom: Inability to walk

Treatments: Chemotherapy, monthly injection for lungs

Mical R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 2

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level detected at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Jeffrey P., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; routine PSA test, then IsoPSA test

Treatment: Laparoscopic prostatectomy

Theo W., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level of 72

Treatments: Surgery, radiation

Dennis G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 9 (Contained)

Symptoms: Urinating more frequently middle of night, slower urine flow

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Lupron)

Bruce M., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4A, Gleason 8/9

Symptom: Urination changes

Treatments: Radical prostatectomy (surgery), salvage radiation, hormone therapy (Casodex & Lupron)

Al Roker, Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7+, Aggressive

Symptom: None; elevated PSA level caught at routine physical

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

Steve R., Prostate Cancer, Stage 4, Gleason 6

Symptom: Rising PSA level

Treatments: IMRT (radiation therapy), brachytherapy, surgery, and lutetium-177

Clarence S., Prostate Cancer, Low Gleason Score

Symptom: None; fluctuating PSA levels

Treatment: Radical prostatectomy (surgery)

3 replies on “Dennis’s Gleason Score 9 Contained Prostate Cancer Story”

Very informative. I am a retired teacher here in Canada. I am 72 years old. Just been diagnosed with prostate cancer. Was nice to read the steps that Dennis went through. Thanks for taking the time to share your journey with everyone that has traveled the prostate cancer road and, for the ones that will be traveling this road. Gave me some relief of what is to come, and how to handle problems I may in-counter. Thanks Dennis

Yes so agree you have to be your own advocate when it comes to personal health. It is so easy to ignore routine physicals and that is a mistake on many levels. Keep a written record of your PSA readings and if you see your numbers rising make an appointment with a urologist. Way to many men rely on their GP for a referral . Way too many GPs wait too long to refer patients

As a prostate cancer patient, personally, I would strongly suggest that if you have a family history of cancer, men at age 40 should have genetic tests done. I have a younger brother who was tested after our father developed prostate cancer. Based on the results his insurance company allowed him to have it removed electively. I wasn’t that lucky. I had asked my doctor about these tests and he said your numbers are very low, you have nothing to worry about, we’ll just watch where things go.

On subsequent PSA testing, I went from 4.1 to 10.8 in a matter of three months. I have a very aggressive form of Adenocarcinoma. I had my prostate removed via the DaVinci method and my numbers dropped down to 0.02. That lasted for about 2.5 years and now my PSA has risen to 0.30. I’ve already completed my radiation simulation along with getting a six-month injection of Lupron.

All I can offer is this warning. You, the patient, have to be your own best advocate. Had I pushed my doctor into getting genetic testing, I too could have had the gland removed before it broke through its margins and I wouldn’t be here worrying about the side effects of radiation along with Lupron.

At a young 71 years of age, I consider myself lucky to have made it this far, and I look forward to many more years of life to come. Stay active, stay vigilant, and get tested, as many men now in their 30s and 40s are finding themselves in this same position.