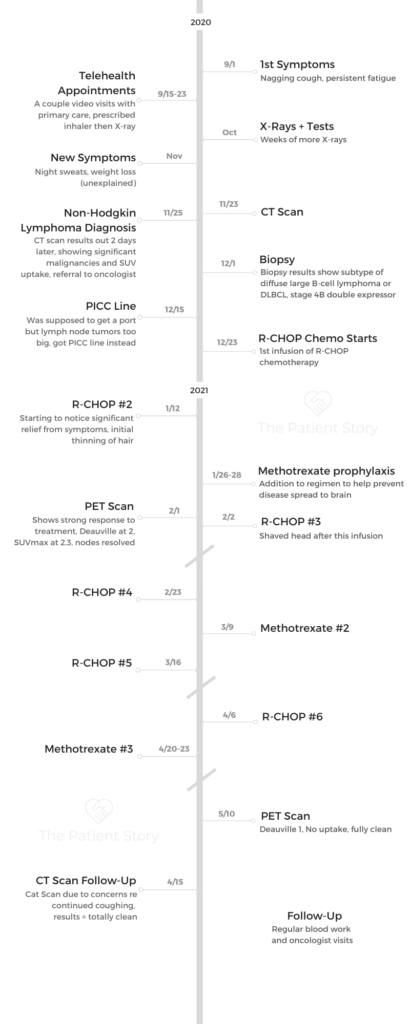

Luis’s Stage 4 DLBCL Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Story

Luis shares his non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma story, getting diagnosed with stage 4 diffuse large b-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), undergoing R-CHOP chemotherapy, and managing physical and emotional wellness.

Thank you, Luis, for sharing your story!

- Name: Luis V.

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

- Subtype: Diffuse large B-cell (DLBCL)

- Stage 4B

- Age at DX: 57

- 1st Symptoms

- Persistent cough

- Extreme fatigue

- Night sweats

- Treatment

- R-CHOP Chemotherapy

- VIDEO: DLBCL Diagnosis

- Introduction

- First Symptoms

- Getting Diagnosed

- You went to a pulmonologist, got another inhaler and then got a CT scan. Did you push for that CT scan?

- How long did it take for you to drop that?

- What was it like getting a CT scan?

- How long did it take to get the results?

- Did you have scanxiety at first?

- Tell us about the day you got your results

- How did you process the news in the moment?

- VIDEO: R-CHOP Chemotherapy & Side Effects

- Chemotherapy

- What was the treatment conversation with your doctor? Did you do your own research?

- You ended up getting a PICC line instead of a port. What are your tips for dealing with a PICC line?

- You had 6 cycles of R-CHOP. How many weeks did you have between cycles?

- Did they say anything to you about patient reactions to rituximab?

- How did you feel after chemo?

- Managing Side Effects

- What's your advice for people dealing with side effects from chemo?

- Major side effects of fatigue and diarrhea

- Tell us about the fatigue

- What helped with fatigue?

- Tell us about the diarrhea

- Was there a time in the cycle it hit the worst?

- Helplessness

- Tell us about the methotrexate prophylaxis that they prescribed because of your spine

- Methotrexate side effects

- Treatment Response

- Chemotherapy

- VIDEO: Living with Cancer

- More DLBCL Stories

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

VIDEO: DLBCL Diagnosis

Introduction

Tell us about yourself outside the cancer story

The elevator speech on Luis is that I’m a Cuban-American and a first-generation immigrant. I grew up on the East Coast and went to school out there. I went to law school here in Chicago and met my wife in law school.

She was originally from the West Coast and wound up settling in Chicago. After a decent run at the corporate world, I’ve spent most of my legal career in government and public service.

We live on the north side of Chicago. I work for a government agency that does a lot of work with the disabled and elderly population. My wife does a lot of estate planning. We have two kids, one of whom is currently on a gap year and starts college next year, and the other is a junior in high school.

We’re almost empty nesters. With having a young kid away at school, they may not be physically present, but I’m already starting to get the notion that they may be very present in your thoughts.

It’s empty nesting. It’s not empty caring or empty worrying. Knock on wood, if things go well, my baby boy could be 40 with serious male pattern baldness, and he would still be my baby.

First Symptoms

- cough

- fatigue

- some weight loss

How did you first know something was wrong?

The very first thing that happened was what I would describe as a nagging cough that just felt different. I still remember very clearly being at my office at my desk. It was an afternoon right around the 1st of September, and I had sort of this slight coughing jag. Even then, I was like, “Huh. Well, that’s interesting.” Then it just kind of continued.

At first, I didn’t give it a ton of importance because for the past 2 or 3 winters, I had gotten some pretty bad pneumonia and bronchitis. I just assumed I didn’t win the lottery when they were giving out lungs, that my lungs are just weak or they’re prone.

I really didn’t think that much of it, but the cough didn’t go away. It kept expressing itself to the point where I got worried enough to be like, “Well, I guess this is my fall call to my primary care doctor so that he can fix up my lungs.”

What kept you going to the doctor even though your X-rays were clear?

I think what kept me going in was the fact that the cough was getting worse and just would not go away. I was also starting to experience this kind of fatigue.

I think a lot of the cancer websites really get it right when they describe cancer fatigue as the fatigue that doesn’t go away when you sleep or you rest.

I also think I was getting thinner, but one of my reactions to the pandemic was to work out obsessively. Again, there was a symptom that could have been masked. It’s like, “Hooray for me, I’m losing weight.”

It’s extraordinarily difficult to articulate with the available adjectives what about the cough and the fatigue made me feel bad. The cough was persistent, it was worsening, and it would respond to the steroids initially, but then as soon as I stopped taking them, it would be back.

The best way that I can describe it was that I started to get this really nagging, frightening feeling in the back of my mind: “Something has a hold of you, and it’s not letting go. So what is it?”

That feeling of “something has a hold of you” was really my first emotional challenge in my illness, even before I knew I had it.

Listening to your inner voice

Listen to that inner voice saying, “Dude, something is off.” Yes, you’ve had a cough the last 3 winters and yes, the last 2 winters you usually wound up on some form of antibiotic therapy or a couple of days off work or whatever, but it just felt different.

Because it was so long and fatigue-centric, for lack of a better term, my first hypochondriacal run at anxiety was something like COPD. I made the mistake of looking up COPD. Google Medical School.

As you know, once you get on Google and look up medical stuff, you can convince yourself that you have 37 different diseases before you’re done in the first hour. Really, it was cough and fatigue, both worsening. It’s difficult to describe.

You don’t want to do too much about retconning, right? Describing what was going on then through the lens of what you know now. But even then, there was a very anxiety-provoking sense of permanence about it. Like hey, this isn’t going to go away, right? There’s a new player on the field, and they’re not going to take the bench.

Night sweats

Right. The night sweats were… I would say if the fatigue and cough are red flags, the night sweats were like a huge Goodyear blimp flashing: “You have a problem.”

They were incredibly uncomfortable and went from, “Oh, I wonder if I turned up the heat too high,” or “Gee, maybe 2 comforters is a bad idea,” to me getting up, feeling incredibly poorly, having to take off a T-shirt that literally felt like I’d gone swimming in it, and then going back to bed.

Getting Diagnosed

You went to a pulmonologist, got another inhaler and then got a CT scan. Did you push for that CT scan?

I didn’t push for the CT scan because I didn’t have to. These are COVID times. Around that time, if somebody says, “Oh, I went to…” you’re doing telehealth, right? There was 100% telehealth for a certain period of time.

I’d called my usual hospital network, and their pulmonologists were booked incredibly late into the year. If I had just sat with one of those appointments, I don’t know what would have happened. I remember I spent an hour during a lunch break on my phone calling anybody and everybody who would listen about a pulmonology appointment.

I finally got through to a pediatric pulmonologist who said, “We specialize in pediatric pulmonology, but I have a friend at this hospital system.” It was one that I was familiar with, but one that I would never have thought of going to. They were perfectly lovely and had a good reputation and everything, but they were just outside my wheelhouse.

I called, and I was able to get an appointment and was very excited for that appointment. The days went by like years and the seconds ticked by slowly, and I finally got to describe my symptoms to the pulmonologist.

He was very reassuring, like, “Well, we don’t know. It could be any number of things, which I think are addressable.” He was concerned at that point about my weight loss, because I think at that point I was down 17 pounds from what I considered to be my baseline weight.

How long did it take for you to drop that?

About 2.5 months.

What was it like getting a CT scan?

I’d had an MRI. I’d never had a CT scan. At this point, I was an incredibly anxious person, because the CT scan was going to tell me something. Nothing appeared to be working.

One of the things that I think that the CT scan folks did very well, and that they consistently did very well throughout my treatment, is that they didn’t let me know anything right away. There were no hidden winks or thumbs up or people crossing themselves.

I think it’s important for folks who are just starting out on this journey to understand that good CT scan and PET scan specialists are going to leave interpretation of the results to the MDs, the radiologists or the pulmonologist.

If your CT tech is having a bad day and being kind of sour and inexpressive for your CT scan, it doesn’t mean that they’ve found anything. It really is a case of, “You don’t know what you don’t know.”

In terms of the mechanics of it, it was very quick. I went in, and they were professional. They explained the process. They prepped me. They did it, and I was gone.

How long did it take to get the results?

The way that I remember it is that it took about 2 days.

Did you have scanxiety at first?

Yeah, and it was an incredible amount of scanxiety. I experienced scanxiety after that, and I will continue to experience scanxiety for X amount of time into the future. One message to my cancer brethren is, “Scanxiety, you can deal with it.”

Tell us about the day you got your results

It was a phone call that I got in a barber’s chair. I was getting my hair cut, and I got a phone call. I sort of missed it. At that point, I was really monitoring my phone, but I was getting a haircut, and my phone was in my pocket.

It was a message from the pulmonologist asking me to call. I told my barber, who I had been going to for a while, “Hey, I’m sorry, but I got to skip part of this. I’ve got to go.” I called him back. I had to leave a message.

I drove back home and actually was so anxious that I called the on-call service for the health system to see if they could help. They were very nice and calling me back, but they were like, “No, it’s got to be him.”

He finally reached me just as I was going into my garage. My garage door came down. It’s winter, it’s cold, and my garage light went out. I was sitting in a dark garage, in a car, and the pulmonologist said, “I’m sorry to tell you that I looked at your CT scan, and there were some findings.”

At that point, I sort of finished a sentence for him, and I don’t know where it came out of. I don’t know if I had been online or if I had read something or whatever, but I was obviously prepped because he said, “Yeah, there have been some findings in your lymph nodes,” and I said, “I have lymphoma, don’t I?”

He said, “I think that’s what it is, but I’m going to send you for a biopsy to make sure. It could be other things. You have to rule out sarcoidosis and a number of other things that can give you those uptake results in a CT scan.” And there you have it.

I think the rest of the conversation — unlike other conversations that I had later in treatment — kind of turned into a blur. I remember him saying that lymphoma was treatable and he was referring me to an oncologist and all of this.

But there you have it: you have cancer. That’s the call.

How did you process the news in the moment?

My garage is 20 feet from the back of my house. Initially, I think, it was a shock. I don’t remember actually making the walk, but I somehow got myself from my car to my house, and I went through the back.

My kids were home, so I just said hello like I regularly do. At that point, the fatigue had gotten to the point where I was doing more lying down than was good for me. I went upstairs to the bedroom and laid down.

It’s so incredibly hard to describe. You probably relive that initial moment where somebody tells you that you have cancer a number of times. It’s a little bit like the fable of the blind men touching the elephant.

Each time I emotionally visit that news, a different aspect of it comes to the fore. There’s shock and fear, there’s anger, there’s a sense of loss, there’s denial, and all of that just is playing out.

It’s just a disastrous emotional kaleidoscope, and it’s hard to keep track of the swirling colors.

I think initially what came out when my wife came in was numbness and denial. Numbness and denial are generally not emotions that people are proud of, but those are the ones that popped up for me.

My wife came in to the room. I said, “Hey, could you close the door?” She closed the door. “Could you come down right next to me?”

She said, “What?”

I told her, “I had a talk with the pulmonologist. I have lymphoma, and it’s a type of cancer.”

She started to cry, and I held her and told her, “Hey, it’s going to be OK. I’m not scared. This is something that’s treatable. We can get through this.”

I was very brave in that moment. I was sort of telling her all the things that she needed to hear — and probably, to be honest, all the things that I needed to hear. That’s not who I turned out to be later, but I think that’s who I was in that moment.

I think when you get a cancer diagnosis, it’s not just the initial talk with the healthcare provider. The fact that you have cancer hits you any number of times throughout the course of your treatment, and there is a way in which you kind of relive that initial moment later on in different forms.

I remember — and it doesn’t happen so much now, and I’m not quite sure why — nights where I would be sleeping, dreaming about something completely unrelated to my illness, and I would wake up. I would just sit upright in bed, and my wife would be asleep. The room would be dark and all alone.

I would just say, “You have cancer.” Not “I have cancer.” I would say, “You have cancer.” It was almost like this other person.

It hits you in different forms, and I think that one of the things that characterizes my initial response to getting a cancer diagnosis is that I was very honest and dishonest at the same time.

I was very honest in the emotions that I was having. They’re very human emotions. There’s fear, there’s anxiety, there’s rage, there’s depression, there’s hopelessness, a little bit of defiance thrown in for good measure.

I think what I was dishonest was about was owning up to having those emotions and understanding that I was at the beginning of what was going to be a very, very difficult process.

VIDEO: R-CHOP Chemotherapy & Side Effects

Chemotherapy

What was the treatment conversation with your doctor? Did you do your own research?

It was pretty straightforward and very helpful. My pulmonologist called me back to say that the biopsy had come back as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, stage 4B. I actually found out that it was double-expressor from my oncologist later.

I had an initial oncology appointment with an oncologist and with 2 coordinating nurses present. That was the first time that I heard that lymphoma was treatable and might even be curable.

He said that R-CHOP, in my case, was the preferred chemo and that it was generally well tolerated by patients and could be very effective.

He said that I would need to get a port inserted so that the chemo could be administered efficiently. He asked some questions, and I answered them. My wife was there, which was good. This was still sort of high COVID.

He laid out R-CHOP and the schedule, which was 6 rounds. He also said that because there was extranodal presentation in my lower spine, I would also be doing methotrexate prophylaxis inpatient to guard against the possibility of CNS involvement or the disease spreading to my brain.

He set up a schedule and a follow-up appointment, and I was off to the races. The next thing after that was to get a port inserted — which turned out to be a problem — and then starting my first R-CHOP on December 22, 2020.

You ended up getting a PICC line instead of a port. What are your tips for dealing with a PICC line?

If you are going to be getting a PICC line, I think it’s very important to make sure that you don’t go home until you have all the flushing supplies and that you have had a conversation with someone about what you’re going to be doing.

You have to keep it very clean, and you have to keep it flushed with heparin. At least in my case, it required nightly maintenance.

There’s a whole thing to it: take off the cap, sterilize your hands, flush it, put it back, get that little mesh sleeve back up. In a way, you know it’s on when you have a PICC line, because there’s this thing sticking out of your arm connected to some pretty major blood vessels, and that’s where the chemo is going to go.

I found out in the parking lot before I went in to get a port inserted that one of my tumors was too large to have a port placed and that I would need a PICC line. I wound up getting a PICC line in my left arm.

»MORE: Read patient PICC line experiences

You had 6 cycles of R-CHOP. How many weeks did you have between cycles?

I did R-CHOP-21, which is R-CHOP every 21 days. The length of the infusion cycles changed. My first one was longer because they wanted to slow-play the rituximab to make sure that I didn’t have a reaction to it.

Did they say anything to you about patient reactions to rituximab?

I’m sure they did for my first R-CHOP and maybe my second, but I was just still kind of reeling, so I don’t remember everything that was said.

I do remember having a pretty extensive conversation with my practitioner about the drugs that were going to be given to me. He did send me for an echocardiogram to make sure that my heart could sustain the chemo. One of the drugs in R-CHOP drugs can be fairly cardiotoxic, so they want to make sure that your heart’s in decent shape before you go.

The only thing that I remember about the rituximab is being specifically told that my first infusion would be longer because they were going to do slow Rituximab just to make sure that I didn’t have a bad reaction to it.

How did you feel after chemo?

I would probably say that a week to 10 days after my first R-CHOP was probably the best that I had felt in a long time. I think that’s because the “P” in R-CHOP is prednisone, which is a pretty powerful steroid.

When I took the prednisone, my cough essentially went away. My cough had been the bane of my existence. The prednisone also helped with the fatigue and appetite issues. I felt like, “Oh, the prednisone will help with my weight.”

Initially, I have to say, I felt better as opposed to worse. I don’t think that is an uncommon response, particularly if you’re stage 4B, because the cancer is everywhere. You have all these B symptoms.

I think there was also the emotional lift of, “Hey, my team is finally getting a point on the board. I’m finally fighting back.”

After my second R-CHOP, I did have hairs in the sink, and my hair was thinning. I was maybe starting to feel a little bit more tired, but I still had what I would consider at that point — even after my second infusion — to be relatively significant relief from symptoms. I would say that the first third of my R-CHOPs, other than the discomfort from the PICC, weren’t terrible.

They do give you anti-nausea drugs, and they give what they call pre-meds. One of them is Zofran. Dexamethasone was also one of my pre-meds, and those drugs really did a great job of controlling my nausea to the point where I essentially had close to a nausea-free chemo.

»MORE: Read other cancer patient experiences with chemotherapy

Managing Side Effects

What’s your advice for people dealing with side effects from chemo?

The one thing that I would say to people starting on treatment is this: if you have a side effect that is affecting your quality of life, do not assume that there’s nothing that can be done about it.

Contact your provider. Contact them early. Contact them often, because these days there are a variety of medications that are very effective, even with pretty severe side effects.

Do not suffer in silence.

Do not say, “Hey, I’m a cancer patient. I’m getting chemo. I’m supposed to be throwing up. I’m supposed to feel like this.”

You may feel like that, but never accept it. Be at peace with it only after you’ve gone through all of the lines of palliative meds for side effects.

Major side effects of fatigue and diarrhea

I think when people didn’t go through the chemo think of the fatigue and diarrhea, it doesn’t sound like very much. But it is incredibly tough on your quality of life. Both of them.

Tell us about the fatigue

Cancer fatigue is like nothing in the world in the sense that it is a tiredness that that is bone deep, and it does not respond to the things that you would imagine would make you less tired, like, “Hey, I’m going to take a nap. I’m going to get an extra couple of hours of sleep.”

It was a level of weariness that literally interfered with my ability to be. It interfered with my existence.

I was very flattened. It was tough for me to do a lot once it hit. It was a real struggle to do things like get out of bed, shower, put on clothing, come down to my basement office, log on to work, eat, do dishes or what have you.

One of the things that I had told myself was that I was going to be as normal presenting as possible for my kids. I was going to do the things that I needed to do, and I was not going to be one of these folks who… well, let’s just say I didn’t want to really present badly.

But the thing about cancer fatigue or chemo fatigue, more accurately, is that even if you look like your old self, you’re doing something like standing up and scrubbing that big pan that you just made a huge dish in or whatever, and things might look OK, you don’t feel OK.

Two people walking side by side down the street, one of them doing chemo and one of them not doing chemo, look very similar, but they are having an experience that is worlds apart.

The person who’s having chemo fatigue could just be hanging on. “You’ve got to make this next half block. I got to make it to the light. OK, I made it to light. I got to make it to the next mailbox.”

What helped with fatigue?

The one thing that really, really helped — and I think the science really bears this out — is when I was emotionally and physically able to move and go out for a walk.

It didn’t have to be a ton. You certainly don’t want to press yourself that much when you’re mid-chemo, like “Heck with this, I’m going to walk for miles,” because you’re going to pay the price.

Practical advice for folks going through chemo is that you’re going to have a reaction to your environment. One of the things that sometimes happens with chemo is that you get very temperature sensitive. I actually got very cold sensitive, and I live in Chicago.

One of the things that my wife did, God bless her, was to say, “You know what? I don’t care what it’s been. I don’t care what it costs. We’re getting you some Arctic Explorer coat, because you’re getting out there, regardless of the temperature,” and that was incredibly helpful.

Tell us about the diarrhea

The diarrhea was very difficult to deal with because it wasn’t even that it was constant, but that when it grabbed me, it just took over all of my intellectual and emotional attention and physical reality for however long it took. When I had bouts, that’s what I was doing. I was breathing, and I was having diarrhea, because that’s what there was.

Was there a time in the cycle it hit the worst?

It got worse as it went on. I would say that I went from a constipation-ish reality to the constipation/diarrhea dichotomy, which is extraordinarily difficult to explain to people who haven’t been through it.

There are some things that you get through by going through them.

Then the constipation went away, and I was left with just the diarrhea. Look, people’s bodies do things, and you just sort of have to be adult about describing it. I didn’t have a watery version of diarrhea. What I had was a very loose and very constant version of it.

One of the things that really affected me was, I had already been having issues with my weight. I had a complex about the way that I looked, and I would have diarrhea so often and for so long that it just really reinforced this narrative of, “Dude, you’re wasting away. You’re literally pooping out your life into this bowl, and there’s nothing you can do.”

Helplessness

I did reach out to my care team. I did take my own advice. I said, “Hey, this is kind of wacky,” and they did give me loperamide for the diarrhea and that helped.

One of the things that became clear to me was that until I was done with chemo, I was not going to be normal in terms of bowel movements and bowel movement quality, whatever you want to call it. It was just something I was going to have to go for.

That’s another message I would give to people who are in the middle of the chemo: there are some things that you get through by going through them. There’s no off ramp. There’s no helicopter that’ll fly over the traffic jam. You’ve got to get through. But I think that the good news is that you can get through. You can.

I think one of the things that can help is to do the things that will help you. Don’t suffer in silence. Call your care team, say, “Hey, I really have problems with diarrhea,” and then have them prescribe something, and then get back to them about whether or not it’s working. Keep that dialogue open.

Tell us about the methotrexate prophylaxis that they prescribed because of your spine

First of all, I did not have the intracathetal. I had the high dose through my PICC line, so I had to do it inpatient. When they admit you, they take various levels. You do get pre-meds as well, and then they give you the infusion.

I don’t recall the actual infusion being that long. If I remember correctly, my first infusion started perhaps mid-evening, and it was over by midnight certainly. It’s not that long. What ends up happening is that methotrexate is so toxic that at that point they start giving you rescue bicarbonate of soda. You have to urinate constantly and keep track of your output.

Methotrexate side effects

Then they do PH testing, and then you need to do methotrexate levels in your blood. Methotrexate, much more so than R-CHOP, has a reputation of having more neurological side effects because it does penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Other than some very slight dizziness, I have to say that I escaped the methotrexate side effects, which were indistinguishable from what was already going on.

Treatment Response

Mid-treatment PET scan showing a strong response

I still remember to this day, as if it was tattooed on my hand, the radiologist’s opening comments — literally the first words that I read — were, “Excellent response to treatment.” That was the first sentence. It showed resolution of a lot of the swelling of the lymph nodes.

It showed that my Delta SUVmax, which is another very technical term that is basically a measure of how active your cancer is in terms of absorbing the marker that they give you when they do a PET scan, was down by over 90%. It was a very, very strong response.

It was one of the first times that I thought, “Wow, you might not be dead by spring. You know what? You might actually have a chance.”

What was your oncologist’s message to you at that point?

My oncologist, like a lot of oncologists, is not necessarily a party animal. But I’m a huge fan of his because he was, I felt, a very honest, grounded and ethical practitioner.

I think a lot of oncologists are very careful with what they say, and one of the things that he said was, “Look, no one can promise you that you’re not going to relapse, but this is an incredibly strong response. It’s actually a better response than I expected at the beginning of your case, and I think that you have a very strong possibility to have a very good outcome.”

Deauville score of 2 at your mid-scan

Yes. There’s very little space between 1 and 2 Deauville scores. They’re both considered “CR,” or complete responses. They’re both things that you absolutely want to see.

I had an oncologist who would be the person who did the rounds when I was doing methotrexate prophylaxis, an inpatient oncologist for lack of a better term. She looked at my interim PET scan results, and said “Medically speaking, you’re in remission,” which is what I think Deauville 2 is. It was the first time that I heard remission applied to my case, and it was quite a moment for me.

What was your reaction to learning you had a Deauville score of 1 at the end of treatment?

I certainly cried when I read it. It was just such a sense of relief, but it was also a moment of “OK. What now?”

I think that probably the best part, the absolute best part, of getting a Deauville 1 and a zero uptake — zero SUV on my last scan was nothing to do with me — was my ability to tell my family. That was really the prize, to be able to tell my wife, “Hey, look at this.” To be able to sit my kids down and say, “Hey, dad’s in remission.”

That was really the icing on the cake. But again, it’s kind of like, what are the next steps after that?

VIDEO: Living with Cancer

Managing Emotions

How do you balance the responsibility of your family’s emotions with protecting yourself?

The best advice that I can give to people who are newly diagnosed, struggling with the emotional impact of the diagnosis, or struggling with survivorship is that you have to stay connected to the world of the living, whatever that means for you.

When you get a cancer diagnosis, I don’t care how optimistic you are or how strong you are or how spiritual you are — it’s a shock. Cancer may be a disease of the bones, it may be disease of the brain, it may be disease of the B cells.

But it’s also a disease of intense loneliness. It’s a disease of intense fear, and it’s a disease of an intense disconnection with who you were and who you thought you might be. You have to fight against that.

It’s a disease of intense loneliness.

That’s a fight where, thank goodness, little victories mean a lot. You do not need to be that person who’s running a marathon while dragging their chemo thing on wheels. You don’t have to climb Mount Everest. You don’t have to do some 10 by 20 foot mural about what it meant to you.

Taking care of others while you are going through this is a form of taking care of yourself.

But at some point, you’ve got to dig deep, and you’ve got to find that little scared, almost imperceptible voice that says, “Hey, I’m alive,” and you have to do something with it.

So for me, was I concerned about leaving my family too soon? Was I in fear of the magical story that’s been my love story, my marriage with my wife, ending?

That hurt. It hurt so much. But it was also part of the cure.

Taking care of others

It was like, “Hey, you want to die today? You want to give up today? That’s great. Be honest, that’s where you are. But what’s going to get you out of bed? What’s going to get you to actually make toast? What’s going to get you to log on?”

Well, I want my kids to be proud of me, whether I live or die. I think that yes, take care of yourself, but understand that as the patient — and I think this does not get spoken about enough in cancer circles or survivor’s forums or whatever — it’s very important that you take care of yourself. It is equally important to recognize that taking care of others while you are going through this is a form of taking care of yourself.

For example, I work at an agency that deals with populations like the disabled and elderly, and one of the things that I do is that I find resources for them. These are folks who have maybe been taken advantage of, and they have very little in terms of a social network or resources for self-advocacy.

My ability to force myself to work through my illness was crucial to my survival because no matter what I felt like, no matter what was going on in my head, no matter how many times I sat on the pot, no matter how tired I was, if I logged on to my computer and spoke to my team and did my job, I was helping other people.

I was here in the world we live in, and I was helping others. I had a purpose. I was not a cipher, I was not a number, I was not a statistic. I was a person whose words and whose ideas and whose actions mattered.

What were your emotions about hair loss?

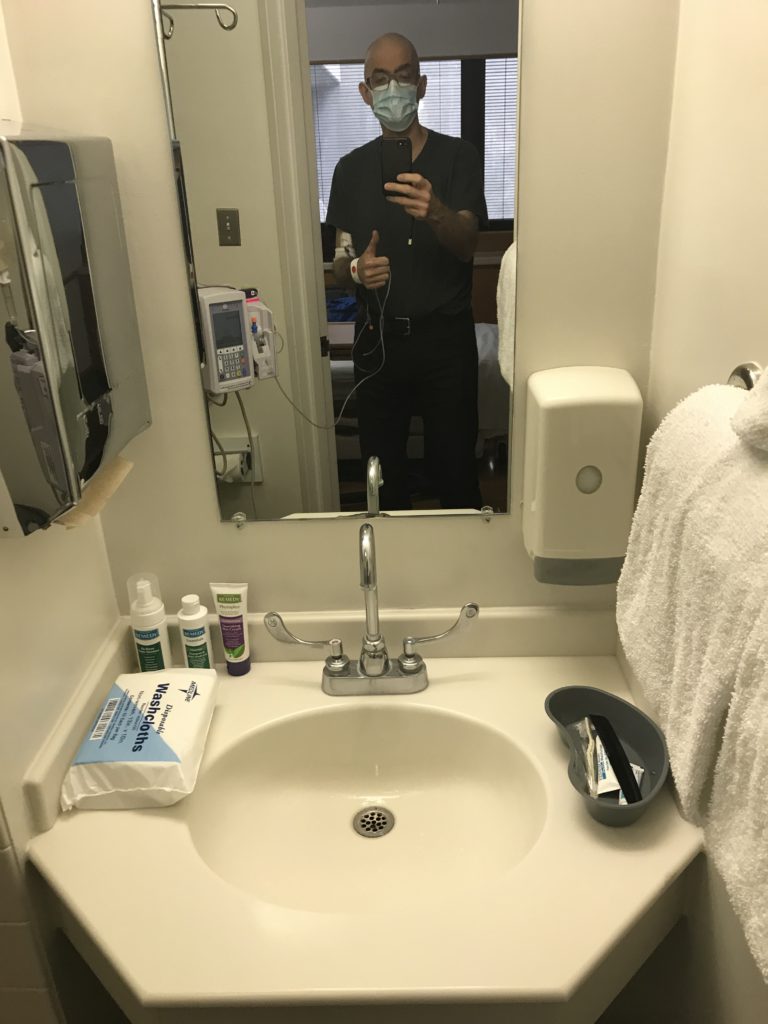

I think people have different sorts of ways of dealing with things in terms of impact. For me, what was impactful was not the day that I shaved it, but the week to 10 days that I let it get sort of ratty.

The slow process of, “Oh my goodness, my comb is full of hair, oh jeez, look at the drain. Oh my God. I’ve done the best that I can, but I can still see three inches of scalp.”

That sort of slow denigration and loss of your visual self-image was hard for me. When I shaved it, it was like, “You know what? I’m not going to negotiate with terrorists. I’m taking control; I’m taking it all off. Me and my bald head are going to fight you until the last fricking hill.”

For me, it was the sense of helplessness, watching it go slowly and knowing that it was just going to happen. That really was painful.

When did you shave your head?

I believe it was between cycles 2 and 3.

Pessimism and Anxiety

What helped you get through scanxiety?

I think there are 2 answers to that question. One of them is just time. Your scan is on a certain date, and that’s it. You’re going to get the results on a certain date, and that’s it. You’re going to get through it regardless.

The question is, “What’s your emotional state going to be while you get through this?” For me, one of the things that helps me with the scanxiety— and I will tell this to anybody who’s newly diagnosed, in the middle of treatment — is that at some point, you have to trust the person that you become fighting cancer.

You just have to trust them. You have to be proud of them, and you have to let them help you. Because you’re not who you were. That person is gone, and they’re never coming back. But it’s still you, and there is this new person.

I would say for scanxiety, trust the science. Understand that optimism is not a dirty word. It sort of is in my emotional framework, but that’s just me. It’s not really a dirty word. You just don’t know what you don’t know.

I think one of the things with cancer is, “Wow, I’ve been tagged with this. What else does the universe have in store for me? Geez, if I got cancer, it must mean that my first scans may be a disaster. Geez, if I got cancer, it must mean that it’s already in my hips. Geez, if I got cancer, it must mean that I’m going to be refractory.”

But you don’t actually know those things. Those are emotional voices reacting to pain.

How did you survive cancer as a pessimist?

I would say that I’m naturally very pessimistic person, and I was very pessimistic when I got diagnosed. My wife got tired of listening to me. “I’m a goner. It’s all over.” You can only imagine like the shock, right?

I did not do things that helped my emotional state for a significant portion of my treatment. I was too passive. Not in terms of dealing with my oncologist or whatever. I was sort of dealing on two tracks. One track was who I was a patient, and that person was active, listening to my doctors’ recommendations, emailing them, making all of my appointments and moving forward.

The other person was who I was when I was not dealing with the medical side of things, and that person was a disaster for a long time. They were scared. They were helpless. They weren’t moving around. They weren’t taking those walks. And that’s OK.

I’m not ashamed to say that my symptomatology, then my diagnosis and then my early treatment just flattened me as a human being. It took so much for me to have the ability to fight, the ability to be and the ability to connect.

My message for my fellow cancer tribesmen is this: if you’ve been diagnosed — or you’re having the symptoms, or you’re doing treatment — and you’re doing everything wrong. Emotionally, you’re just shattered and everything’s broken, and there’s nothing except this cold wind that blows through you every day from the moment you get up to the moment you fall asleep…

That’s OK. You can still survive, and you can still turn it around. Don’t feel bad. It’s all right. Yeah, you’re a lump on the floor. You know what? Lumps on the floor? They have a right to live, too.

Survivorship

Fighting the guilt becomes a cycle

Right. I think that it goes back to what I said about how you should trust yourself as a cancer patient.

Think about media representations of cancer and popular ideations of what a cancer patient might look like and what they’re supposed to do. We’re supposed to be noble and helpless. We’re supposed to live in the moment every day and live every day as if it was our last, while essentially having no hope that we’re going to have an outcome that’s anywhere near like the life of someone who doesn’t have cancer.

It’s such a harmful and skewed vision of who we actually are. We’re human beings.

Not having cancer is not a guarantee that you’re going to make it to that 100-year birthday party or anything like that. It’s no guarantee of happiness, and it’s no guarantee of anything. At some point, understand that this emotional damage, this fear, this real need, is part of the journey. I think one of the things that helps is when you take your first step beyond it.

It’s not perfect, right? Because here I am. I’ll be 6 months in remission in a few days. Gee, that’s great, right? What does it mean? Well, it doesn’t really mean anything in and of itself. Doesn’t mean I’m cured, doesn’t mean that I’m going to be alive in 10 years. It doesn’t mean I’m going to be alive in 20. What it means is that I’m six months in remission, and I’ve got today.

What am I going to do today? I’m going to help somebody today. How am I going to be seen today? How am I going to see other people today? That’s really important.

I would encourage people when others say, “Live every day as if it was your last,” to really shut that message down. Because to me, that message works best when you cut it in half, and you just leave it at “Live every day.”

Honoring your journey

One of the things that I told myself was that I was going to work the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivor color into my life somehow, which is lime green — which, you know, they couldn’t have gone with something more subtle? But hey, it works for me, right?

Initially, I had all my nails done in lime green because I literally told myself at one point in my treatment, “If you don’t die right away, you’re going to do this because this is your ‘thank you and I’m here’ to the universe.”

Then I decided that 10 lime green nails is probably a little much. I went with a more subtle color, but I kept the one on the wedding ring finger.

Next up is going to be my lime green ribbon tattoo with the words “No one fights alone.” My barber is very into tattoo and body piercing as a way of body expression and self-expression, so I was telling her about my plan.

She said, “I just got to warn you, once you get one tattoo, it’s a rare person who can stop.” So we’ll see where it all ends.

Inspired by Luis's story?

Share your story, too!

More DLBCL Stories

Mike E., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Persistent, significant back pain

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy

Don S., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Symptoms: Weight loss, fatigue, enlarged lymph nodes

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy (epcoritamab)

Michael E., Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Symptoms: Back & leg pain, rash, severe itching, decreased appetite, weight loss

Treatments: Chemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapy, clinical trial (no improvement from study drug), immunotherapy (epcoritamab)

Barbara R., Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), Stage 4

Symptom: Abdominal and gastric pain

Treatments: Chemotherapy R-CHOP, CAR T-cell therapy, study drug CYT-0851

One reply on “Luis’s Stage 4 DLBCL Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Story”

Thank you, Luis, for your honest and eloquent description of the circumstances of your disease. I, too, have been diagnosed with DLBCL and have completed my first R-CHOP treatment. So far, so good! I wish you all the best for a long and healthy future.

Rich