Dave’s Stage 1B Neuroendocrine Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Story

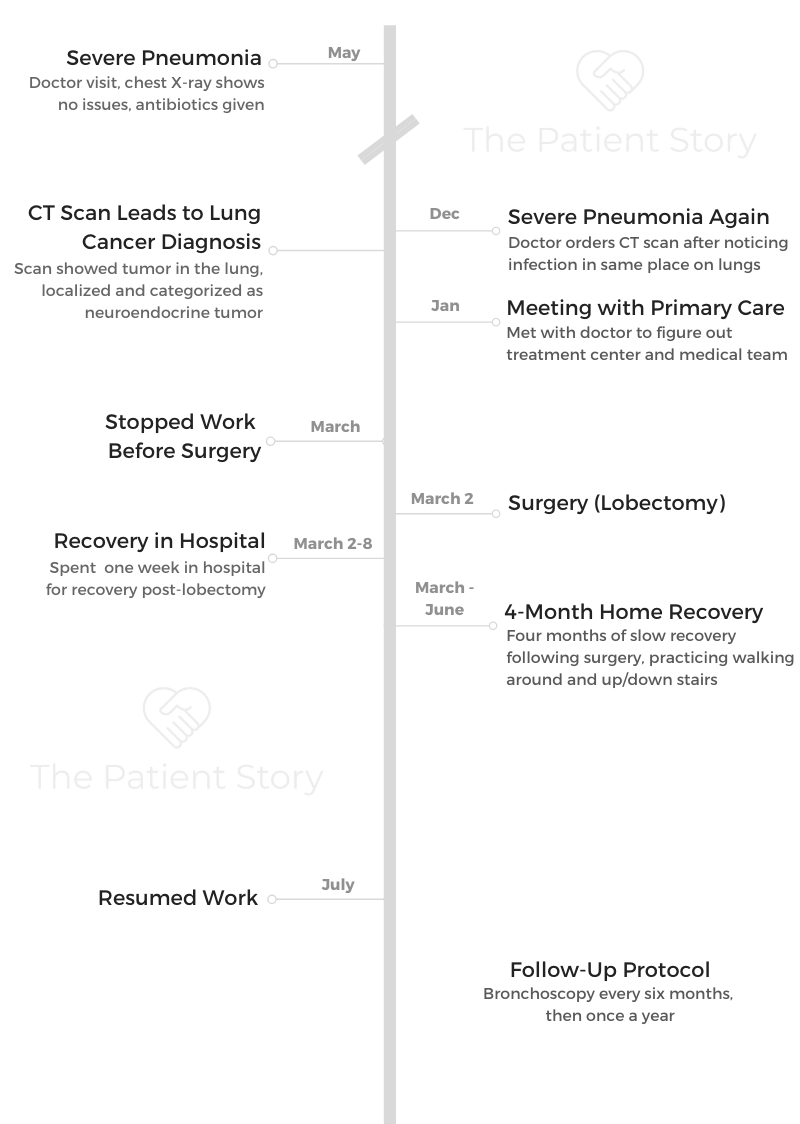

Dave shares his stage 1B non-small cell lung cancer diagnosis, a neuroendocrine tumor, and how he got through a lobectomy (surgery) and months-long recovery.

In his story, Dave also highlights his advocacy work and gives guidance to other lung cancer patients and caregivers on how to navigate a diagnosis, the importance of taking care of the caregiver, learning about latest treatments, the stigma of smoking and lung cancer, and how to benefit from the strong social media community.

- Name: Dave Bjork

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Lung cancer

- Non-small cell

- Neuroendocrine tumor

- Stage 1B (3 cm tumor)

- Age at DX: 34

- 1st Symptoms

- Severe pneumonia twice despite being healthy

- Treatment

- Surgery (lobectomy)

- Video: Dave Shares How He Got Diagnosed

- Getting Diagnosed

- Treatment decisions

- What was the discussion like on next steps?

- Seeking out other patient experiences

- Did you get a second opinion?

- Generational and cultural differences

- What was your subtype of lung cancer, and when did you find out the staging?

- Was there any talk of mutations and genomic testing?

- Guidance: having caregivers help with figuring out treatment decisions and medical team

- Tip: have others at your doctor’s appointment

- Video: Dave Talks Surgery & Recovery

- Surgery (Lobectomy)

- Recovery from Lobectomy

- Support and Reflections

- Video: Dave Shares Tips for Other Lung Cancer Patients/Caregivers

- Advocacy & Guidance for Patients/Caregivers

- How did you shift from patient to advocate?

- What does advocacy work mean?

- How should patients and caregivers think about new therapies and treatments?

- Finding your cancer community online (#LCSM)

- Stigma of lung cancer and smoking

- The stigma may hurt research, awareness, and funding

- The White Ribbon Project

- There's been progress in lung cancer research

- Tell us how people can find you now

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Video: Dave Shares How He Got Diagnosed

Introduction to Dave

A lot of what I would say defines me is from my cancer experience, but it amplified my background. I’m a Minnesota guy living in Boston for a long time. I’ve been married for 30 years and so very grateful for the wonderful life I have.

The experience of surviving a cancer scare changes you, as people know. It changes everything about how you look at life.

I live a life of gratitude, and I try to be focused on that when I bring positive vibes to everybody I encounter.

Getting Diagnosed

What were your first symptoms?

I was a young guy, non-smoker, and up in Maine with a friend of mine fishing in May. It was freezing cold. I got super sick with chills while I was up there.

I got back, and it turned out I had pneumonia. I went in, saw my doctor, got a chest X-ray, antibiotics, and told to be on my way.

I remember my wife, who’s a nurse, and I both thinking that it seemed really weird that I’d get pneumonia. I had been playing basketball every day at the YMCA down the street, so I was really healthy. I didn’t smoke. A lot of us who get lung cancer never thought about it.

About 6 months later, I got sick again, and I got pneumonia again. I was thinking, “I’m 34 years old and healthy. Why did I get pneumonia again?”

Now I was getting worried about it, so I went in and talked to my doctor with the same process. I was fortunate because a radiologist noticed that the infection in my lungs was in the same spot as it was the first time.

A lot of primary care doctors don’t think about screening for lung cancer. That’s when I got the call that I got from my doctor after that, telling me that I should go get a CT scan.

I got the CT scan because the doctor said he wanted to check why the infection was in the same spot. He thought there might be a blockage.

Describe the moment you got the diagnosis

It turned out that it was a tumor, and that’s what I remember — the day my doctor called me and said, “Dave, it’s Lee. You need to come see me. We found a tumor in your lung. You have lung cancer.”

That’s when my life just flipped upside down because I couldn’t have even imagined that that would be what I would hear from him. Just thinking about it now, I get emotional because it was so profound.

Those were my initial feelings about it, utter shock, but then hanging up the phone, and everything was speeding up. I thought about my boys. I had a 5-year-old, a 3-year-old, and a 1-year-old. What do I do?

Those are probably common with others getting diagnosed, feeling those emotions.

They couldn’t tell the stage, though they could a bit by the size of the tumor, but they couldn’t tell how aggressive it was. The only treatment for that type of tumor in that location was lobectomy, which is surgery.

How did you process the cancer diagnosis?

I can share something that’s probably useful for people and patients, whether it’s a neuroendocrine tumor or some other form of it. I reacted by deciding that I was going to go find out everything there was to know about that particular type of tumor.

That was, in some ways, not the right thing to do because all I did was stress myself out. I was reading the worst possible outcomes. I was catastrophizing.

I processed it by saying I would just go and find as much information as possible. It was a very complex thoracic surgery, not really user-friendly information.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

How did you break the news to loved ones?

My wife knew, but I didn’t know how I’d share with my friends and my work. I was lining up emotionally all the things I needed to do between going and seeing the respiratory therapist and meeting with potential surgeons I’d have to work with.

Mostly, it was that the cancer was in me, and I needed it out. Now.

It wasn’t all-hands-on-deck because I didn’t have to go immediately into chemotherapy or something.

Processing that emotional part of it so you don’t scare yourself, but you have to start finding support for what you’re going through.

Treatment decisions

What was the discussion like on next steps?

I had a meeting with my doctor to talk about the steps. He was like my quarterback. Also, when people are diagnosed, it’s trying to find your care team.

For me, it was going to be at Mass General Hospital because that’s where my primary care was. When my mother had a health care experience and was in a community hospital setting, she had to decide whether she’d stick with her local community hospital or travel. She was in Palm Springs, California, at the time, so she would have traveled to Los Angeles to get her care elsewhere.

The chest X-ray couldn’t define what was wrong, so the CT scan was the logical next step. I hadn’t had one before that.

I had a pretty good understanding of what the CT scan was about based on talking to my doctor and my wife, who’s a nurse, so I was lucky about that.

Seeking out other patient experiences

There are ways to connect with other patients now, and that’s what I would encourage people to do if you get that initial diagnosis and think, “What do I do?”

That whole process of setting up a care team and making those treatment decisions. Do I go to an academic or community hospital, who’s been through the same thing I’m anticipating and who can help me?

Did you get a second opinion?

I didn’t get a second opinion. I think it’s because I felt like I was in the best place possible. My particular situation was not a complex issue. The type of tumors that I had was something Mass General had a lot of experience in.

But here’s an interesting story. I had someone contact me a year or so ago to introduce me to a friend who had lung cancer. He had gone to UCSF to get an opinion but wanted to know if he should get a second opinion.

When we connected on a call, without knowing his situation, I said, “Absolutely, if you want the comfort of having a second opinion, you should. If your doctor thinks you’re crazy to do that, that’s on him or her, because you deserve it.”

As a patient, you have to be your own patient advocate and in charge of your own care.

»MORE: How to be a self-advocate as a patient

Interestingly, I looked up the name of the oncologist he saw at UCSF, and it was one of the top guys in the world. It turned out he had the same type of cancer I had.

Each person is different. If you do feel the need or if you feel you’re not comfortable with what you’ve been told, you should absolutely seek out a second opinion.

Generational and cultural differences

This can be a generational issue. With my mother, she wouldn’t seek out a second opinion because she trusts her doctor, right?

I think it’s important for someone, if you have a parent and you’re a caregiver or part of a team of caregivers — that person, like my mother, may not think to get a second opinion.

What was your subtype of lung cancer, and when did you find out the staging?

The staging was based on the size, so it was stage 1B, a 3-centimeter tumor on my lower left lobe. From the CT scan, they could tell by the shape of it that it was localized and a neuroendocrine cancer.

During my surgery, they checked the lymph nodes. After surgery, I found out there was no spread of the disease. That’s when you get the final classification of the staging.

Because it hadn’t metastasized, there was no immediate attention needed other than recovery from the surgery.

Was there any talk of mutations and genomic testing?

It never came up. There’s so much more knowledge about targeted treatments now.

I can speak for people who’ve had or will get a lobectomy. It’s a very tough, invasive surgery. I was in the hospital for a week on heavy doses of medicine. I had a morphine drip, but it didn’t even help because it was so painful.

Guidance: having caregivers help with figuring out treatment decisions and medical team

You can help navigate the system, or someone else can help on your behalf if you’re not that type of person. Someone who’s one of your caregivers can help you navigate through the treatment decisions.

It’s up to the comfort level of the patient. Everybody’s different. I’m married to a nurse, and her father was a pharmacist, so we were very engaged in the process.

For other people, they’re caught by surprise and don’t know what to do next, have no experience in health care, and don’t know who to turn to.

Whether it’s your family or close friend, I do believe it’s very important to have someone help you navigate it.

Even if you’re good at it, it’s good to have someone else help you navigate it. That’s where it’s great to find other patients who have been through the similar experience. It’s not always easy, like if you have a rare disease, but in general, it is easier to find people now.

Tip: have others at your doctor’s appointment

Once you hear the word “cancer,” you may not hear the next words that come out. If somebody is sitting next to you, it might be good to have them to take down information about it because it can be very overwhelming.

Editor’s Note: You can also record your doctor’s appointment for reference later.

Video: Dave Talks Surgery & Recovery

Surgery (Lobectomy)

What kind of doctors did you have, and how did they explain the surgery?

This is a fun part of my story, very positive part of it, because my primary care physician really knew me well.

He knew I was Minnesota Nice and always engaged with my medical team, so he knew picking the right surgeon would be really important to me.

At a place like Massachusetts General Hospital, there might be 7 thoracic surgeons who do the type of surgery I needed. The first step was my doctor sent me to meet with some respiratory physicians. He handpicked because he knew I would really like them, and they explained what the process would be like.

Then my primary care picked my surgeon, Dr. Doug Mathisen, who was the chief of thoracic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital.

There were 2 reasons my doctor chose this surgeon. First, he was the chief of the department, which meant he was “the man,” though they were all good. The second thing was he played college basketball at the University of Illinois. He was a Midwestern guy and was very outgoing and nice.

My doctor even told me that I would love him. I got to meet with Dr. Mathisen, and he was so amazing. He sat me down. He had a whiteboard, drew the lungs, and showed me where the cuts would be. He explained the process.

The one thing he didn’t prepare me for — and maybe in some ways it was good I didn’t know — was anesthesia. I’d never had it before because I never had major surgery, so I didn’t know what that was going to be like.

Describe the day of surgery

Day of the surgery, I was nervous, but I wasn’t as nervous as I would be future times when I had to go back under anesthesia for bronchoscopies, when I’d be a nervous wreck.

It was difficult to prepare for how I would feel coming out of anesthesia after a 4.5-hour surgery. I was in so much pain and so disoriented. It was awful.

What was the prep before surgery?

It was an early-morning surgery. I had to be there at 6 a.m. I had to fast the night before but can’t remember the number of hours. I was told I couldn’t eat after a certain time. Then I showed up, and I was the first surgery of the day, so that was cool.

Now I’m remembering the night before, and I was super stressed. My parents and my brother had come into Boston to visit me. They were like, “Hey, it’s going to be great!” I was like, “No, it’s not.”

I remember thinking if someone says to you that you’ll be fine, you’ll do great, it’ll be nothing, or you’ve got this, it’s like, “Yeah, really? It’s me it’s happening to.” It was kind of hard to sleep the night before.

Sitting in the waiting room when you show up to the hospital and you go into the surgical unit is when it becomes real. Things just got real.

Then you go in and sit down with the anesthesiologist, get changed into your gown, and that starts the communication about the process of anesthesia. By the way, that was another person chosen by my primary care doctor, so that was good.

What do you remember about waking up from surgery?

I remember exactly that moment. I woke up with my lips really chapped. I was sitting, looking up, in a recovery room, and everything was very loud.

The voices were probably amplified. Even if people were just speaking in a normal voice, it was so loud. I remember being disoriented. I looked up and asked if anyone was there, asking for help. The noises were further confusing me.

The chapped lips happened because the breathing tube was in the mouth the whole time. Then I remember the process of going and settling into my hospital room, trying to find a comfortable position.

You have a chest tube coming out, which I call a garden hose, a big tube to help drain the liquid out of your chest. It’s super painful. You have to sit at an angle in the bed to have the tube. You can’t sit on your back, on your stomach, and you can’t really be on your side. You have to prop yourself up with a pillow.

Then they have the morphine drip. If you don’t know what that is, it’s a way where you can self-administer the medicine by pressing the button, but it’s on a timer. You can only get it after, say, 7 minutes, so you can’t just constantly get the medicine.

I remember hitting it all the time because I couldn’t wait for the next minute. It also made me sleepy and feel out of it, so I wasn’t really seeing or feeling things happening around me. It dulls the pain but doesn’t take the pain away.

»MORE: Read more patient experiences with surgery

Recovery from Lobectomy

Describe recovery in the hospital

The first day after surgery, you have to get up. You can’t just sit there. The nurses want to get you moving, which is a big part of the recovery. They come in every day with a portable X-ray machine and get you out of bed.

I remember the first time I stood up, I took 1 or 2 steps, and that was it because it was so painful. I got back into bed.

The second day, I tried to make it to the edge of the room by the door. I remember thinking that I wanted to get around the unit by the end of the week. I was walking with my bags around the floor. I recall thinking I just had to get through it.

The nurses were amazing. They wake you up in the middle of the night to do physical therapy and hit your back, all around 3 in the morning. They let my wife sleep in the room, so she was in a chair next to me.

I remember one of the nurses on duty that week on the night shift being so brilliant. I wish I was more proactive in remembering her name to be able to thank her!

What helped you through the week in the hospital recovering from major surgery?

Understanding ahead of time and getting myself in a mindset of how invasive this surgery was.

People might think of a lung surgery being less significant because now they have these laser surgeries, but they still do lobectomies.

They make a big incision in your side and basically break your ribs, like open heart surgery. If you’ve ever had a broken rib, you understand how painful that is.

The recovery after the hospital was where I can share with people what to do. You’re going to be told what to do recovering in the hospital. You have to get up at specific times, you have to walk, and they’re going to give you the pain medication.

Describe the surgery recovery at home

I remember getting home and walking upstairs to the bedroom was excruciating. I could barely walk. It was like I was a 90-year-old person walking up the stairs.

I remember lying in the bed, and every time my wife would just sit on the bed, it would hurt so badly. That part of the journey is really about taking that mindset of, “You got through the hospital. Now you’re home.” You’re probably not going to remember a lot of the time spent at the hospital because of the medicine.

Get yourself into the mindset where you have to get through the next period.

I can’t get through Saturday until I get through Friday, and I can’t get to Friday until I get through Tuesday. I broke it down into these little windows of time, like I can’t get to 5 until I get through 3.

I even broke it into 5-minute segments. I compartmentalized it so that I couldn’t think of a month or a week from now. I’m in so much pain. I just have to get through the next 10 minutes or until I get my next Vicodin, because it’ll be wearing off in 4 hours, and I have to take another one.

This is not a woe-is-me thing, by the way. I’m so grateful for the experience that I had and that I didn’t have to make decisions on targeted therapies or immunotherapy, what stage is the cancer, or whom should I talk to? There are so many people who describe these situations in my advocacy work.

I don’t mean to make this sound like I’m complaining about it, because I’m definitely not. I’m just trying to share what to expect during the recovery. Once you’re done, there’s no doubt that the feeling of gratitude in comparing my experience to others who have it a lot worse than me.

At that time, the life expectancy of someone with lung cancer was really bad. It’s improved. It’s still not good, but way better than it was back then.

What else helped with recovery at home?

I was lucky because I had a caregiver, my wife, who made everything easy. With my work, I was able to have people cover for me. I did start to get back to doing some things work-wise after some weeks.

I remember setting goals of going downstairs because it took me a while to get down the stairs. Believe it or not, even that was hard.

I remember when I finally got outside, it was awesome because it was spring, and my neighbors saw me walking down the street. They were like, “Dave, how are you doing?” I had literally not been out of the house for a long time.

Everybody copes differently with getting through it, but I believe in a positive attitude. I believe that helps in the recovery in whatever treatment you’re getting.

Support and Reflections

The importance of taking care of the caregiver

A big thing for me is I could have done a better job of appreciating my caregiver. That’s one piece of advice I like to give to people: to make sure that you take care of the caregiver.

The patient is locked in many times in the treatment and just trying to get themselves emotionally ready. My experience was my wife as a caregiver did everything.

We had 3 little kids. She was feeding them, getting them to school, doing the single-parent work that was just thrust upon her, and worrying about me, as I would if she was in that situation.

Emotionally, it’s so hard. She was sitting in the patient lounge during my surgery. Thankfully, she had a friend go with her to visit because she was an emotional wreck.

It’s important to recognize the emotional experience of the caregiver. It’s not as simple as, ‘We can have people help make us dinners.’ It’s a whole package and emotional experience someone goes through.

I just told someone the other day about this. If it had been reversed and I had been the caregiver, my wife was in that hospital, I know she would have been emotionally devastated because of not being able to take care of the kids.

Thinking of what it would have been like for me being the person taking care of everything while she was down and out, that’s the best advice I can give. Patients, we can do this. We can be sensitive to that.

Parenting with cancer

I don’t think my kids were old enough to understand what was happening or how serious it was. My kids are older now.

I think if that had happened now, every family would really have to think about how to have that conversation with your kids.

Friends of mine with stage 4 metastatic lung cancer have a really hard job to do: talk to kids and get their arms around that. They know their parents are likely to not live a long time. Some are living a lot longer now.

Any guidance on asking for help?

I believe in asking for help.

As a caregiver, I do remember some friends of mine who stepped up, not even being asked to step up. They were amazing. I’m very grateful for that.

It’s okay to ask for help. You probably get friends who will ask what they can do or let them know if you need anything. This isn’t just in cancer, but if somebody says, “Let me know what I can do to help,” how many times do we not ask them for anything?

If you’re a caregiver and you have a loved one who’s in the hospital or is undergoing chemotherapy or serious treatments on a regular basis or clinical trial, and you’re emotionally out there, it’s okay to accept help from your friends.

Video: Dave Shares Tips for Other Lung Cancer Patients/Caregivers

Advocacy & Guidance for Patients/Caregivers

How did you shift from patient to advocate?

In my case, it was actually transformative to me because my background was finance and sales and marketing. I had been working at the Bank of Ireland.

After I recovered, everything changed. My life changed. I needed to do something I was passionate about.

I started working in medical marketing at a publishing company to provide patient education materials to cancer patients.

Going back to being treated at Mass General Hospital and being from a place in Minnesota where some family lives in rural areas, I felt every person should have access to the same level of care.

I literally felt I wanted to change my career path because I was so profoundly impacted by the cancer experience that I started to become more active.

I wasn’t super active right at the beginning about sharing my story, which is an interesting part of my journey. For many years, I didn’t want to be wearing it on my sleeve.

I felt almost guilty that I had such a positive outcome and many people didn’t have positive outcomes, even people in my first hospital room. I was hearing the conversation in the bed next time, and it was bad.

It really shifted my thinking that I wanted to be in health care and be involved in patient advocacy.

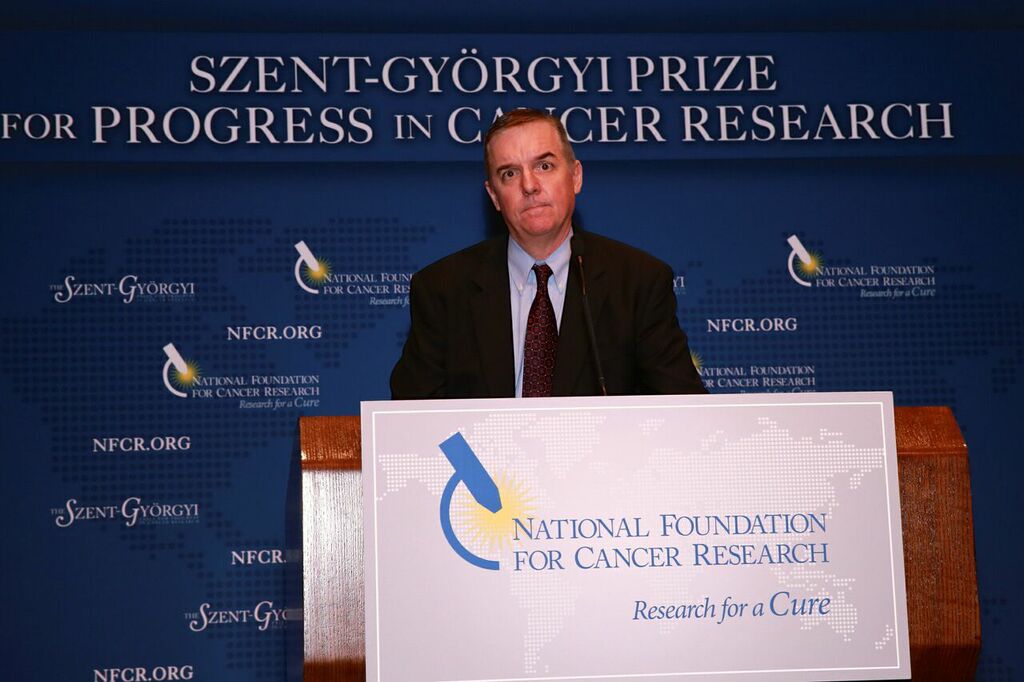

I ended up working at the National Foundation for Cancer Research, which was where I really decided to get more active in the community. I started writing a blog and started being active on Twitter.

I started meeting people (like you see in this photo), fellow advocates of mine, but it really was because of the experience and because emotionally I wanted to make a difference. I felt like if I could make a difference and make a living doing it, that’s what I would do.

I couldn’t go back to just doing work that didn’t seem important to me anymore, to be selling investment service products to small businesses, which is what I was doing.

What does advocacy work mean?

This photo is a good example. The way I look at advocacy is many of us within the community feel that everyone has their lane.

Every advocate has what they think is their calling, their purpose, their mission. It’s going to be different for every person.

For some people, advocacy might be raising awareness that anybody can get lung cancer. It’s not just a smoker’s disease.

Others might be advocating for themselves because of a clinical trial and want to make sure they have access to trials. Janet Freeman-Daley is a scientist, so her lane is to make sure she can educate people on the latest scientific findings.

We’re all in this together. We need to shout from the mountaintops about lung cancer and the good things that are happening.

Patient advocate is a broad category that gets a lot of attention now because it could be advocating for access to clinical trials, diversity in clinical trials, or gender equity in cancer treatment.

There are so many different ways to think about advocacy, with the goal of making sure patients get good care and good outcomes.

How should patients and caregivers think about new therapies and treatments?

We talk about targeted treatments as an example. You have your diagnosis and your staging. You have this conversation with your physician on what type of cancer you have.

Is it non-small cell or small cell? Within that, the focus of my advocacy work is that I believe every patient should have access to genomic testing because now there are tests.

For instance, there are 7 biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer, meaning there’s a mutation identified through a genomic test. There’s EGFR, ROS1, KRAS, etc. There are targeted treatments available for those. That means taking a pill, not taking chemotherapy.

Even before that, you think about how you get the information to know and ask these kinds of questions about treatment options and clinical trials.

First, you have to be your own advocate. If you’re not your own advocate, it could be a spouse or friend. You have self-advocacy where you find the information.

»MORE: How to be a self-advocate as a patient

Luckily, there’s a lot of information out there. You have your care team. You get information from them, and hopefully they’ll help you with options. Don’t go to clinicaltrials.gov and try to figure it out yourself.

What you can do is once you have your diagnosis and understanding, first ask for a genomic test, or someone will recommend you have one. Find out if there’s a mutation that has a treatment.

With those 7 biomarkers now in targeted therapies, that’s a game changer.

That’s why everyone should have access to it. If you’re a patient and you don’t have access, that’s not fair.

Finding your cancer community online (#LCSM)

There are people in the lung cancer community, particularly online, where you can connect with people who have the same diagnosis as you do.

On Twitter, for example, many of us in the community use the hashtag LCSM. That stands for “lung cancer social media.” That’s how I’ve met tons of people who are patient advocates and patients, as well as clinicians and researchers.

Within LCSM, there are also groups forming around different mutations. There’s the EGFR Resisters, the KRAS Kickers, or ROS1ders (“ROS-one-ders”).

You can find people who have the same diagnosis that you do. That’s where you can get a tremendous amount of information, whether it’s about clinical trials, treatment options, or where should I go for treatment?

That support network is so important, so I really encourage people to think about that when you’re doing searches for your particular situation online. Consider tapping into those resources, and reach out to those people. They will respond.

Stigma of lung cancer and smoking

Within the lung cancer community, the stigma is something that bothers all of us to a certain degree, some more than others. That’s not to say that people who smoke deserve cancer. I’m always sensitive to that as well.

It’s estimated now that 20% of people who get lung cancer are non-smokers, never-smokers, or people who smoked a long time ago and didn’t smoke a lot. If 20% of the patients getting diagnosed with lung cancer are non-smokers, it doesn’t seem right that somebody should ask if you smoked. That’s what happens. It happened to me; it happens to everyone.

People ask if you smoked, and it’s like smoking is implicated in a lot of cancers. When someone gets breast cancer, you don’t ask if they smoked. That could have been one of the factors. When you’re talking about the stigma, it’s the years of those campaigns of anti-smoking. The message was, “How do you not get lung cancer? Just don’t smoke, and you won’t get lung cancer.”

That’s not true. If you have lungs, you can get lung cancer.

People who are advocating in the lung community and very active are talking about how anybody can get lung cancer.

I’ve read that of the non-smokers who are getting diagnosed with lung cancer, a lot of them are much younger, and two-thirds of them are women. There are issues around that as well. How can we grow awareness of that?

The stigma may hurt research, awareness, and funding

That’s what the stigma is. Some people talk about the inequity in research funding, thinking that maybe lung cancer research doesn’t get as much attention because it’s a “smoker’s disease.”

Here are numbers that may put this into perspective. If 200,000 people get diagnosed with lung cancer every year in the U.S. and 150,000 people die of lung cancer, if 20% of that 150,000 is 30,000 people, that’s a big number. Even if it’s “only 20%,” it’s 20% of a big number.

It ranks up there as a very prominent people in that category of non-smokers.

The White Ribbon Project

This just happened a few months ago in October. We were just talking about the stigma of lung cancer and people who are not smokers. There was a couple in Colorado, Pierre and Heidi Onda. She has stage 3 lung cancer.

People didn’t know she had lung cancer, and they asked if she smoked. She wanted to change the perception. She was frustrated and wanted to do something to let people know she had lung cancer.

Her husband is a primary care doctor and a craftsman who has a workshop in his basement. She said she wished she could just put a ribbon on the front door. He said he could make a ribbon, a white ribbon, which is representative of Lung Cancer Awareness Month.

She wanted to do this year round, not just focused on the actual month. He crafted it out of plywood and painted it by hand. People, including me, caught wind of this.

People began asking if they could make them one. It started popping up, and it reminded me of the Humans of New York project, where it was the faces of lung cancer.

This is the modern face of lung cancer. We started taking photos at the places where we got treated, at cancer centers with other friends and families, at biotech and pharmaceutical companies.

We wanted to try and be active on social media and send the message that anyone with lung can get lung cancer. Let’s change the public perception of lung cancer as a disease.

It’s a grassroots effort. We’re just going to be out there. So far, Pierre and Heidi have made almost 400 ribbons by hand. It’s a wooden ribbon, quarter-inch plywood, and made with care. That’s the story.

People from coast to coast and in Canada are asking for these ribbons. Oncologists are contacting us to get one and put on display and having this conversation about lung cancer.

We think these conversations will lead to more potential research funding because of the fact that we’re telling the story.

This is all unbranded. That means it’s not attached to any one nonprofit organization. It’s just us advocates out there who care. It’s not just patients, by the way. It could be someone who lost a cousin to lung cancer or knows a colleague with lung cancer.

Similar to the HIV campaigns years ago or the breast cancer campaigns that become true grassroots movements. That’s what we’re doing in lung cancer right now.

There’s been progress in lung cancer research

From when I got treated until now, there’s a lot more hope. It’s a scary diagnosis, particularly if you’re diagnosed stage 3 and, of course, stage 4. I know people who are living 10 years beyond a stage 4 metastatic lung cancer diagnosis.

There’s a lot of hope and optimism out there.

Emotionally, that’s something to be thinking about. Also, the journey of finding support, finding a team you’re comfortable with, finding other people who have had a similar experience — to me, those are the most important things you can do to get through the initial shock of getting lung cancer.

Tell us how people can find you now

The podcast is called “The Research Evangelist.” You can find it wherever you find your podcasts on Apple or Spotify. The background of the podcast was that I wanted to become more vocal.

I’ve been writing a blog for many years, but I wanted to use my spoken voice. I decided to interview people in life sciences who are brilliant but not famous. That’s the message.

I’m meeting a lot of people in research, whether researchers or oncologists or both. They’re doing clinical trials. People who are just doing amazing work.

There will be a lot of focus on lung cancer and precision medicine in cancer, what is genomic testing in lung cancer, and highlighting people whose stories I want to tell so they can connect to patients. They might be at Massachusetts General Hospital, University of Wisconsin, UCLA, UCSF, or at a community setting.

It’s a positive message in the name, because the Greek meaning of the word evangelist is “bringing the good news,” and I’m a very optimistic person. My goal and mission is to introduce these fascinating people who are doing good work.

When I say brilliant but not famous, some of them are famous in their world, like Narjust Duma out of the University of Wisconsin. The lung cancer community knows her, but if I went to my next door neighbor and said, “Hey, have you ever heard of her?” They’d be like, “No!”

Maybe you can support their lab or their work. Contact her and find out what she thinks of the latest treatments. These people are receptive and brilliant, many of them. Many people don’t think you could contact a lung cancer researcher and actually have a conversation with them, but you actually can!

Click here for “The Research Evangelist” podcast.

Inspired by Dave's story?

Share your story, too!

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Stories

Shira B., Lung Cancer, EGFR+, Stage 1B

Symptoms: None per se; discovered during a preventative full-body MRI

Treatment: Surgery (thoracotomy)

Phil P., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ROS1+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Persistent cough, nasal drip, shortness of breath, inability to speak in full sentences

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation therapy, next-generation ROS1 inhibitor (clinical trial)

Stephanie K., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Persistent and intense cough, general feeling of sluggishness

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy through a clinical trial, radiation therapy

Ruchira A., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Mild intermittent cough while talking, low-grade fever, severe nonstop cough, coughing up blood, collapsed left lung

Treatments: Surgery (lobectomy), targeted therapy

Jennifer M., Lung Cancer, EGFR+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: None per se; discovered during physical checkup for what seemed to be a sinus infection

Treatments: Radiation therapy (stereotactic body radiation therapy or SBRT), targeted therapy